Abstract

Background:

Diabetes is a demanding disease with a complex treatment regimen. Many persons with diabetes have difficulty managing their disease and taking medication as prescribed, possibly because they lack knowledge and sometimes misinterpret medical benefits. Community pharmacies continuously provide professional counselling to persons with diabetes.

Objective:

This study aimed to explore 1) which services adults with type 1 and type 2 diabetes want from community pharmacies and 2) how pharmacies can meet these wishes.

Methods:

A qualitative, explorative study design using focus group interviews was chosen. Informants were recruited from Region Zealand in Denmark. Data were digitally recorded, transcribed verbatim and analyzed by means of thematic analysis.

Results:

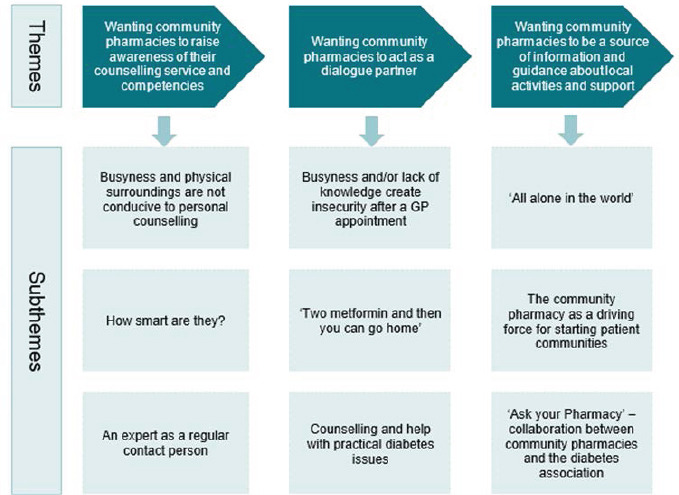

Thirteen adults (11 female) with the mean age of 66.2 years (range 49–81 years) participated in one physical (n=6) or one online (n=7) focus group interview. Ten had type 2 diabetes, three had type 1 diabetes. The average duration of participants’ diabetes was 13.4 years (range 2.3–33.0 years). The analysis revealed three overall themes of the functions which the informants would like community pharmacies to fulfil: 1) raise awareness of pharmacies’ counselling service and competences; 2) act as a dialogue partner; 3) be a source of information and guidance about local activities and support.

Conclusion:

The informants did not regard community pharmacies as a natural part of the healthcare system or as a place where they would expect counselling. They would like the community pharmacy to make their medical competences and services obvious and the community pharmacy staff to act as a dialogue partner and provide competent counselling. The informants would like to have a contact person with diabetes competences with whom they can book an appointment to complement over-the-counter counselling. They experience a gap in their care between routine visits in the healthcare system and suggest that community pharmacies counselling services become a natural supplement and that healthcare professionals in the primary and secondary sectors inform patients about the services - especially for patients newly diagnosed with diabetes. Finally, they would like a formal collaboration between diabetes associations and community pharmacies to make their competences, services and information visible.

Keywords: COVID-19, Vaccination, Side effects

INTRODUCTION

Diabetes is a demanding disease that requires daily attention and a disease on the rise that will strain the future capacity of healthcare systems to deliver counselling and treatment.1-3 The primary goal of the medical treatment of diabetes is to keep blood glucose levels as close to normal as possible to reduce or postpone the risks of complications.3-6 To attain this goal, persons with diabetes must pay close attention to their diet and monitor their carbohydrate intake, physical activity, and blood glucose levels to adjust their medication accordingly.3,4,6,7 However, many find it difficult to manage a complex daily treatment regimen, especially taking medication as prescribed, because they lack knowledge and sometimes misinterpret medical benefits.3,8,9 Over time, the risk of complications makes medical treatment more complex3,4,6,7 and adds demands on both the person living with diabetes and the healthcare system to provide the necessary counselling.2,3,7

Community pharmacies are in a position to reach out to and support persons living with diabetes with solving their diabetes drug-related problems, as persons with diabetes in Denmark get their prescriptions at community pharmacies.10-12 Pharmaceutical care and services13 provided by the pharmacy workforce can supplement medical diabetes treatment to ensure safe and effective use of medicines, which improves the quality of life of persons with diabetes. The pharmacy workforce can identify, prevent and raise the awareness of short and long-term complications by motivating patients to take their medication as prescribed.14

In several countries, community pharmacies offer diabetes treatment services that help control the disease.15-17 Currently, pharmacies in 43% of European countries deliver diabetes management services, offering to perform various measurements: glucose (76%), weight (95%), blood pressure (90%), cholesterol (73%) and hypertension (37%).14 In Denmark, community pharmacies offer two adherence services: The New Medicines Service for persons diagnosed with a newly onset chronic disease who have started medication within the last six months, and the Medication Adherence Service for persons with a chronic disease who have received treatment for more than a year and show signs of low medication adherence.18 These services are grounded in research studies that have developed and tested them. A randomized controlled study which included persons with type 2 diabetes, showed an improvement in patient health, well-being, knowledge, and satisfaction.19

Policymakers globally have recognized the potential of community pharmacies to support persons with long-term conditions such as diabetes, which reduces the workload of general practitioners (GPs).20-23 By using community pharmacies, persons with long-term conditions have better access to support in taking their medication, because community pharmacies have long opening hours and non-appointment-based services delivered by clinically trained, well-qualified pharmacists whose skills could be further deployed, as a study has shown.24

Community pharmacies have several opportunities to more actively provide medical counselling and other health services to persons living with diabetes.15-17 Although many countries already offer community pharmacy services that help patients manage their disease and may even be an integral part of diabetes treatment, this is not always the case.25 The next step is therefore to explore how community pharmacies could complement existing healthcare services and help persons with diabetes manage their demanding and complex medical treatment regimen.24,26,27 This requires an understanding of what persons with diabetes want from community pharmacies and which services they would find helpful. Previous research has explored stakeholders’ perspectives on specific services28 rather than the general expectations and awareness of the extended role of community pharmacies from patients’ perspectives.29

Therefore, the aim of this study is to explore 1) which diabetes and medical treatment services adults with type 1 and type 2 diabetes want from community pharmacies and 2) and how community pharmacies can meet these wishes.

METHODS

Design and data collection

A qualitative explorative study design was chosen using focus group interviews to collect data. Focus group interviews are useful for discussing perspectives, gaining insights and generating ideas from a wide variety of participants.30 A semi-structured interview guide was developed, including printed statements and topics for handing out at the focus group interviews to stimulate reflection and discussion and to prompt ideas about how persons living with diabetes can use community pharmacies. This was followed by questions about how community pharmacies may fulfil the ideas. The topics comprised ‘talking about worries or challenges when taking medication’, ‘medical treatment possibilities’, ‘effects and side effects of the treatment’, ‘preventing complications and treating comorbidities’ and ‘ways for persons with diabetes, outpatient clinics, general practitioners and community pharmacies to collaborate in the future’. This approach was inspired by the ‘think aloud method’31 and visual story telling.32

Focus group interviews were digitally recorded, transcribed verbatim and checked for accuracy33 by the first author. Transcripts were uploaded to NVivo Software (QSR International Version13 xx, QSR International Pty Ltd, Doncaster Victoria, Australia) to organize data and support the analysis process.

Recruitment

Informants were recruited from Region Zealand in Denmark, which has 38 community pharmacies. Advertisements were placed in local newspapers; information leaflets were handed out at the community pharmacies and at meetings at the local diabetes associations. Informants were not paid for participating. Inclusion criteria were adults (+18 years of age) who have had type 1 or type 2 diabetes for more than one year and are followed either by a diabetes outpatient clinic or by a GP. Exclusion criteria were persons not able to speak or understand Danish.

Analysis

Data were analyzed using a 6-phase thematic analysis as provided by Braun and Clarke.34 The transcribed data was read and re-read to gain an overview of the content (1. Familiarization with the data). The first author then inductively coded the transcribed data (2. Inductive coding). The coding process was subsequently discussed with another author to help develop themes. Relationships between the codes were sought to develop subthemes and subsequent themes (3. Development of themes). Any disagreements were resolved by consensus following discussion, with reference to the coded and original transcripts. Transcripts were again revisited to ensure the developed themes corresponded with the data and to develop a richer description of the themes (4. Reviewing themes). Each theme was given a name that captured the essence of its contents, and the transcripts were again revisited to identify representative quotes to use in the written analysis (5. Defining themes). Quotes were selected to ensure a balanced representation of participants from both focus group interviews. Theme descriptions and quotes were discussed and presented to all authors. A narrative of the themes was written using quotes identified as illustrative evidence (6. Reporting).

Credibility was addressed by researcher triangulation throughout the analysis with the authors having experience with diabetes or with qualitative research or having experience with community pharmacy practice. Transferability was ensured by offering thick descriptions, dependability was ensured by providing quotes from informants and confirmability was provided by thoroughly describing the processes of sampling, data collection and analysis.35

Ethics

No ethical approval is required by Danish law when conducting qualitative studies.36 Ethical considerations were met and performed in accordance with the ethical recommendations of the Helsinki Declaration.37 Written and oral information was provided before the focus group interviews and signed consent was obtained. Information leaflets stated that data would be treated confidentially and anonymously in accordance with the EU General Data Protection Regulation ACT (GDPR) and that the informants could withdraw from the study without further consequences.

RESULTS

Two focus groups were conducted between August and October 2020, lasting 90 minutes each. One was a physical meeting (n=7) while the other (n=6) was conducted online (Microsoft Teams) due to the COVID-19 situation in Denmark. Two male informants participated – one in in each focus group interview. In total, 13 informants participated, with a mean age of 66.2 years (range 49–81 years), mean duration of diabetes of 13.4 years (range 2.3-33.0 years). Five informants were followed by an outpatient clinic at a hospital (OUTH) (n=3 type 1 diabetes, n=2 type 2 diabetes). The remaining 7 informants visited general practitioners (GP) or diabetes nurse regularly (n=7 type 2 diabetes). One informant did not provide information about location of control (Table 1. Characteristics of the 13 informants). The informants who were followed by an OUTH can contact a diabetes nurse if they need counselling between visits. The other informants told they lack this opportunity. Table 1 gives an overview of how often the informants visit a healthcare professional and a community pharmacy, respectively.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the 13 informants

| Characteristics | |

|---|---|

| Sex F/M (n) | 11/2 |

| Age in years, mean (range) | 66.2 (49-81) |

| Duration of diabetes in years, mean (range) | 13.4 (2.3-33.0) |

| Type 1 diabetes (n) | 3 |

| Type 2 diabetes (n) | 10 |

| Medication, oral treatment only (n) | 5 |

| Medication, oral and pen treatment (n) | 5 |

| Pen or pump treatment (n) | 3 |

| Taking other medication (n) | 12 (1 missing answer) |

| Outpatient clinic visits (hospitals)* | 5 (1 missing answer) |

| Visiting the GP or diabetes nurse** | 7 (1 missing answer) |

| Visiting community pharmacy every fortnight/once a month/other range | 4/5/3 (1 missing answer) |

Visiting physician or diabetes nurse or dietician four times a year

Visiting general practitioner or diabetes nurse 2, 4 or 12 times a year

In the following the results from the thematic analysis is presented

At the beginning of both focus group interviews, the informants found it hard to express what they want from the community pharmacy beyond the storage and sale of medication because the informants do not regard community pharmacies as part of the healthcare system or as a place where they could expect counselling. During the focus group interviews, the informants’ different experiences and ideas helped them to discover which supplementary or additional services they would like from the community pharmacies. The informants all stated that, especially when newly diagnosed with diabetes, they think community pharmacy counselling about the medication and how to manage living with diabetes could be a relevant supplement to existing healthcare services.

The thematic analysis revealed three overall themes capturing those persons with diabetes want community pharmacies to fulfil three functions: 1) raise awareness of pharmacies’ counselling service and competences; 2) act as a dialogue partner; 3) be a source of information and guidance about local activities and support for persons with diabetes. These are illustrated in Figure 1 together with the associated subthemes to each theme which are also further presented in the following section where subthemes are written with italics. FGI1 is an abbreviation for focus group interview 1 and FGI2 is an abbreviation for focus group 2. The letter I in front of all quotes is an abbreviation for the word Informant.

Figure 1.

The figure illustrates that the three themes influenced each other in this order, as the first theme was the basis for the second theme and subsequently the third. The associated subthemes related to each theme are presented under each theme in the figure.

Wanting community pharmacies to raise awareness of their counselling service and competences

The informants find that community pharmacies draw attention to neither the staff’s competences nor the services offered. The informants express that they only randomly receive counselling offers when picking up medication. Otherwise, they either have to discover the community pharmacies counselling services such as the New Medicines Service themselves or even request counselling. These circumstances coupled with the physical layout of the pharmacy’s customer waiting area generally determine how comfortable the informants feel with asking questions and involving pharmacy staff in their challenges with living with diabetes.

Busyness and physical surroundings are not conducive to personal counselling

The informants find that community pharmacies are often busy, with lines of customers. As such, they hesitate or avoid asking questions or requesting counselling when picking up medicine. They want to be polite and helpful by not taking too much of the staffs and other customers’ time. They also think other customers may need counselling more than they do, as the following quote illustrates:

I: And … you know, they’re busy, they’re busy, there’s a line, many people are waiting with their numbers, and so you can’t spend half an hour or fifteen minutes discussing your disease back and forth with them, I really don’t think (FGI2).

The informants experience the physical surroundings do not invite private talking with pharmacy staff. The informants thus want better physical facilities that ensure discretion, such as a separate room for personal discussions. They also realize that community pharmacies must attend to customers within a reasonable timeframe, and therefore suggest that booking an appointment for a private conversation might be a possibility. Here exemplified with the following quote:

I: …. Well, I think it would be an idea that, just like you make an appointment with your doctor, you could make an appointment … at your community pharmacy … not in the counter area, but away from the counters, so you don’t have to stand there and … tell them stuff … like in a public area … (FGI1).

‘How smart are they?’

Most informants wonder how qualified pharmacy staff really are – especially in relation to diabetes. This hesitancy makes it difficult for them to imagine how staff might enhance their diabetes management – ‘You don’t expect them to know about things like that’(FGI2). Although staff are always pleasant, the informants wonder why the same questions are always asked when they pick up their medication – ‘Do you want the cheapest?’ and ‘Have you bought this before?’(FGI1). The informants speculate about these questions, feeling unsure whether the cheapest medicine is equally safe, for example. They say knowing what questions staff can answer is hard, as the following quote illustrates:

I: I think it’s just as much that you don’t really know what you can ask them about … you think they just know what it says on the information leaflet, and that’s what they tell you when you get the medicine. But, in air quotes, ‘how smart are they’? I mean, do they know exactly what you need? (FGI1).

A lack of clarity regarding the counselling available and its benefits primarily accounts for confusion about what to ask staff about and the services to be expected and how they may benefit from it. To the informants, counselling only seems to occur coincidentally, and they feel they have to find out about the available options themselves. They state that it is difficult to determine how competent the staff really are. The informants further suggest that community pharmacies should start to ‘promote themselves’, highlighting their competences and services, such as the New Medicines Service, through posters or short videos shown in the customer area. Informants who have asked for help because they chanced on the available services say they find the staff highly qualified and competent, as the following quote based on an experience from a New Medicines Service illustrates:

I: …. They’re really smart at the pharmacies and they know a lot, it’s not just empty talk. At least that’s the experience I have. But of course, you need the opportunity to talk to them to find that out … (FGI1).

An expert as a regular contact person

If the physical surroundings are optimized and the opportunity to book an appointment is possible the informants would very much prefer to talk to the same person at the community pharmacy. This would be helpful, so they do not have to retell their medical history when they talk about their situation with the pharmacy staff. The informants also state that it is important to achieve a personal relation with the pharmacy staff as regards having confidence to start to talk about private challenges of living with diabetes. It is also important that the pharmacy staff have continuous access to relevant, new knowledge about the medication and the disease to meet patients’ individual needs. Above all it is crucial that you feel safe and want to engage with a person who has the needed competences – and such contact person could be one who is employed at the community pharmacy, as this quote illustrates:

I: I will say that you should ask whoever makes you feel secure, and if that’s a pharmacist who’s helped you many times, then I’d also think that they would need expert knowledge…. (FGI2).

To support and optimize the outcome of dialogue with the expert, the informants suggest developing a kind of dialogue sheet. This sheet could be a shared collaboration tool to help persons with diabetes and staff prepare for dialogues and to ensure both are aware of the topics to be covered. As such, the dialogues would be tailored to each person. Here illustrated with the following quote:

I: … That you’ve given them a rough idea of what you want to talk to them about, so they have an opportunity to look up which medicine you might be getting. And that you know what you want to ask and what they’re able to answer. That the community pharmacy maybe creates a form of a dialogue sheet where it’s like written down, things like ‘are there any side effects’, ‘are there any issues with …’ (FGI2).

Wanting community pharmacies to act as a dialogue partner

Topics informants would like to talk with pharmacy staff include their medication, practical equipment issues and relevant health apps to help them manage their diabetes. Unhappy that the busy healthcare system lacks such dialogues opportunities, they feel alone with their thoughts, worries and reflections about the disease and its medical treatment. However, the needs of informants who visit OUTHs appear to be better met, as they have access to a diabetes nurse almost whenever needed.

Busyness and/or lack of knowledge create insecurity after a GP appointment

Some informants sense the same busyness at the GPs as they sense at the community pharmacy. Others find themselves talking to different GPs every time they visit the office. Some GPs have been upfront with informants about having insufficient diabetes knowledge: ‘I might as well say it like it is, I don’t know a lot about it.’ Consequently, the informants often feel insecure, doubting the accuracy of the GP’s medical recommendations. They fear errors may be made and are uncertain whether the GP considers drug interactions when prescribing new medication. This causes anxiety and at worst, a fear of medicine poisoning. As such, informants want the opportunity to air their concerns with pharmacy staff, as the following quote illustrates:

I: … the doctor prescribes some medicine … it could be different types of medicine … I get medicine against pain, high blood pressure, etc. And we know that a lot of elderly people … … they actually get medicine poisoning, because no one checks up on it. ‘Is that really true?’ I mean … your body changes and you most likely have different needs. It would be nice if you could get one of those medicine checks … if that’s doable. (FGI1).

Since some of the informants find it hard to talk things through and obtain sufficient counselling from their GPs in the allotted time, they suggest that GPs and OUTH staff should know the competence and various medication counselling opportunities are available at community pharmacies. The informants do not want to waste their GP’s time having experienced them being busy and believe pharmacies could give them the right information and counselling instead, therefore suggesting that GPs could inform patients about community pharmacy services and competences. Here illustrated by the following quote:

I: You could imagine as a first step that doctors maybe told you about the opportunity to talk to the pharmacy, right? And that’s also when you’re sitting there and they don’t have time. Then you could imagine that they had a small card or that they could have it on their wall … or a folder in their folder rack, and then they could suggest it themselves, right? (FGI1).

‘Two metformin and then you can go home’

The informants expected GPs or OUTH staff to be able to provide more counselling and dialogues about medication and how to manage a new disease, which they were not necessarily able to. As a result, informants express they need someone else to talk to, particularly when being diagnosed or being prescribed new medicine. They experience they often had to manage their diabetes on their own – as regards how to live with the diagnosis and incorporate medication into their daily lives. Through the interviews the informants reflect on and discover the potential of drawing on community pharmacies’ expertise. The informants suggest that persons with diabetes should ask for advice or that pharmacy staff should be aware of that desire when people pick up medication shortly after diagnosis, as exemplified here:

I: … And then you’re there as a new patient and you’re diagnosed with diabetes at your doctor’s, and you get that two metformin, … and then you just go home and figure out what to do, you know ….…I mean, the instruction should be at the doctor’s or at the diabetes nurse or the outpatient clinic, right …… but instead it could maybe be at the community pharmacy when you start picking up your medicine (FGI2).

The informants do not consider topics such as handling fluctuating blood glucose levels, decisions about number of daily/weekly blood glucose tests and blood glucose levels’ impact on mood as relevant for discussion with pharmacy staff. They state that these topics should be handled at OUTH or GP’s. Instead, they want someone to talk to about how to prevent or postpone comorbidities and complications, how different medications interact and what effects and side effects drugs have. Here illustrated by the following quote:

I: But the problem is that you … get a lot of different kinds of medicine. We’re all getting blood pressure medication and cholesterol medication. And maybe you’re getting pain-relievers, etc. And sometimes you have too many side effects, and you have no idea what’s what. It’s impossible to find out. Then it would be nice to have someone to talk to about it (FGI1).

The informants also suggest that community pharmacy staff could take the initiative to inform them about new, different medication products when they pick up medicine. They believe such information would prepare them to discuss their opportunities, risks and benefits when talking about changing products or ways to optimize their medical treatment at their next GP appointment. This is exemplified by the following quote:

I: … They [the community pharmacy] could be really, really good to have as a dialogue partner, so that you can get info about new medicine that comes on the market … so next time you have an appointment with your GP, this could be an opportunity to have an in-depth discussion about whether this is a good idea or not (FGI2).

Counselling and help with practical diabetes issues

The informants lack help, advice, and knowledge about practical diabetes-related issues such as how and where to apply for medication subsidies, how to be considered for a medicine payment scheme, and what podiatrist and ophthalmologist services they are entitled to under the national rules. They also suggest that it could be helpful if community pharmacies could measure HbA1c before GP or OUTH appointments and then forward the results to the GP/OUTH. The informants would also like the opportunity to discuss recently launched apps that help them order new medicine, new blood glucose equipment, finger prickers and test kits. The municipality provides these items but getting practical advice about how to use them is difficult without a hands-on demonstration. They realize that since sales of these items have ceased, asking for such advice may be difficult. However, it would be very helpful if staff asked whether help dealing with these practicalities was needed and recognized the importance of such help in diabetes management. Here illustrated by the following quote:

I: … If your fingers are a little stiff, and then you must find out, what’s this device, how do I press the buttons, how do I see what it is, stuff like that, you know? And then I thought that … with new products … blood sugar monitors, finger prickers … when you (community pharmacy staff) hand over medicine to someone like that, you could say: ‘what kind of finger pricker do you use, and what kind of …?’ (FGI2).

Wanting community pharmacies to be a source of information and guidance about local activities and support for persons with diabetes

The informants often feel alone managing their diabetes in everyday situations, which is a burden. They lack somewhere specific to go for information and an overview of local options for persons with diabetes, as well as other guidance. Since almost everyone visits the pharmacy, they suggest that community pharmacies could be a central source of information about local diabetes activities.

‘All alone in the world’

The informants find they need more support to manage living with diabetes than they get from the existing healthcare system. They want a single local place where they can get an overview of the knowledge and options available for people with diabetes. They state that especially for persons newly diagnosed with diabetes it is very hard to figure out on their own how to handle the disease. They remember having felt suddenly all alone, struggling to get a grip on their situation and the disease’s ultimate impact on their lives. The situation often seems more overwhelming than it actually proves to be, as the following quote illustrates:

I: … You’re standing there, all alone in the world, when you find out about this the first time. And typically, if you’re … … getting on in years a bit, you know … It came as quite a shock for me, because all of a sudden, I would have to change my whole life around … I thought (FGI2).

In order to avoid feeling ‘all alone’ they remember that in a kind of despair they started to look for help and knowledge elsewhere. For instance, they contacted local diabetes associations to learn about other people’s experiences, checked diabetes Facebook groups, or joined local peer-to-peer motivation groups to exchange experiences on self-managing life with diabetes. They sought this help because their friends and relatives were unable to truly relate to their situation. They recall encountering attitudes such as: ‘You can just exercise or eat your way out of it’ and having to justify and explain their choices. They find it difficult to talk to or get support from people who do not have diabetes. The informants also find that the advice they get from their GP or community pharmacy tends not to be detailed enough and therefore inapplicable to their own lives. Therefore, they seek peer-to-peer guidance instead. Here exemplified by the following quote:

I: … Now that I started the ozempic … I lost nine kilos in eight weeks, right, and it really, really made me feel bad … … but I did figure it out quite quickly … in this Facebook group, right (laughs) … But I would have liked that … … the community pharmacy had … told me a bit more about how it all works, you know (FGI2).

The community pharmacy as a driving force for starting patient communities

The informants express that they would appreciate not having look for diabetes communities by themselves to get knowledge and information about local options. They suggest that community pharmacies could provide information about various communities, for example, by gathering groups of persons with diabetes and organizing physical activities and venues for them. Here exemplified by the following quote:

I: You know, the pharmacy could have some information about the opportunities in our area. What clubs and associations are there, what could I join? … maybe get something started … some instructors or something … where you could make some communities (FGI1).

‘Ask your Pharmacy’ – collaboration between community pharmacies and the diabetes association

The informants suggest that community pharmacies and the diabetes association could establish a permanent collaboration to highlight the opportunities each offers. For instance, a slogan ‘Ask your Pharmacy’ or a short feature about community pharmacy services could be posted on the diabetes association website. They also suggest a short video could be available there informing members – whether newly diagnosed or not – about how to take advantage of the pharmacy staff’s diabetes medication expertise plus other relevant topics and services available to help them cope with diabetes. This would inform them about what to expect from the community pharmacy the first time they pick up medicine, as the following quote illustrates:

I: You know, the diabetes association could make like a diabetics’ school or something … a kind of briefing about what you do now that you’re a diabetic, that would be the first time you’re at the pharmacy to pick up your medicine (FGI1).

The informants also suggest that the local diabetes association invite local community pharmacies to attend various events. This would give event participants the opportunity to ask about the medical diabetes treatment options, new products or other relevant topics and information about community pharmacy services. These suggestions were based on previous successful one-time events, as illustrated by the following quote:

I: … they came from the community pharmacy and told us about the options and the kinds of medicine and how they work. And the people with diabetes had the opportunity to ask: ‘So what’s this, what’s that? And is that? And for how long can we get it?’ We were really happy with that (FGI2).

DISCUSSION

The findings show that, as persons with diabetes may not always be aware of the community pharmacy services and the competences of pharmacy staff, the community pharmacy has not been a place for the informants with diabetes to approach for counselling, although they regularly pick up their medication there (Table 1). In addition, the findings revealed that neither informants nor other healthcare professionals view community pharmacies as a natural part of the healthcare system. However, the findings reveal that persons with diabetes have several unmet needs, such as dialogue about their medication, worries about polypharmacy and the risk of medicine poisoning, effects and side effects, practical diabetes issues and places to turn to when wanting to engage in diabetes communities between their routine healthcare visits. This study shows that this leaves patients on their own to overcome and deal with their concerns, because neither community pharmacies nor GPs seem to invite to or signal time to thoroughly discuss these matters. The findings show that the informants suggest that community workforce promote their competences and are actively open to dialogue about diabetes medication at the counter – especially with persons with diabetes who are newly diagnosed or starting new medication. The New Medicines Service38 may be one way to meet these wishes. However, our findings show that neither this service nor the Medication Adherence Service38 seem well integrated in community pharmacy practices, because few informants know the services. The dialogue sheets suggested by the informants in our study could foster a focused discussion between the patient and the counselling person.39,40 Such tools have already been developed and tested in diabetes out-patient settings and have helped patients and diabetes staff identify diabetes-related problems and facilitated shared decision-making on how to resolve them.41-43 To ensure that patients experience continuity when picking up their medicine, a combination of a contact person system, pre-completed dialogue sheets adapted to a community pharmacy context and the New Medicines Service38 could meet patients’ needs for counselling about their medication. In addition, the work force should be particularly competent in diabetes treatment.

Our findings support previous research that showed that not many patients are aware of the available community pharmacy services or of pharmacy workforce’s expertise.44 Consequently, community pharmacies are still rarely seen as a natural place for counselling.28,44-47 However, our study findings show that once persons with diabetes realize that services are available and that the workforce is competent, they believe that community pharmacies could play a more active role between regular OUTH or GP visits. The challenge is that in Denmark no formal collaboration exists between patients with diabetes, OUTHs, GPs and community pharmacies, so patients are not aware of these options. A formal collaboration may require an integration of new healthcare models based on collaborative, systematic teamwork between interdisciplinary healthcare professionals – including pharmacists. In such a model it should be considered that the patient plays a central role.48 The American Diabetes Association (ADA)5 and the Canadian Diabetes Association49 recommended such a collaboration in 2017. Pousinho et al. conducted a review showing that clinical pharmacists contribute positively to the management of patients with type 2 diabetes and argued that pharmacists should be included in routine follow-up.25 The study review showed that intervention group participants had improved HbA1c, blood glucose and blood pressure levels as well as a better lipid profile and BMI than those in the control groups.25 Studies have also shown that clinical pharmacists contribute positively to the management of patients with type 1 diabetes and argued that pharmacists should be included in routine follow-up.50-52 Such findings are important, since support to manage a complex treatment regimen is linked to a decreased risk of diabetes-related complications.2,3,7

It has been verified that clinical, pharmacy-led diabetes management programmes at hospitals or medicine family clinics have an impact on health outcomes.51,53,54 However, the possible benefits or challenges of including community pharmacies in traditional routine visits as a natural part of the patients’ medical treatment has not been investigated. It is, however, well documented that community pharmacy service programmes supporting adherence have a significant effect on glycaemic control, improve medication adherence and improve blood pressure.19,55,56 Interventions by community pharmacies may therefore to a greater extent help persons with diabetes to self-manage their medication and life with diabetes.57 However, community pharmacy services are not connected with the rest of the healthcare system. The forthcoming results of a Canadian study investigating how such a connection could be achieved – even when remuneration schemes are in place58,59 may shed light on this shortcoming.

The need for the support and counselling revealed in our study reflects more than 40 years of research in community pharmacy practice, as described in an international series on integrating community pharmacies into primary healthcare.60 These papers show that primary healthcare systems globally have yet to include community pharmacy competences and services, and that pharmacies’ collaboration with other healthcare professionals remains limited.18,61-70 The challenge is still for community pharmacies to promote their competences and services to make persons with diabetes aware that they can ask for advice when they pick up their medicine. To this end, a formal collaboration between diabetes associations and community pharmacies could be initiated, as our informants suggest, and subsequently, national campaigns could be launched.

Our study findings also revealed that persons with diabetes look for diabetes communities but do not know where to turn. Persons with chronic conditions such as diabetes are known to seek online communities, especially when established healthcare systems fail to provide the needed counselling.71 This is in line with our study findings, which showed that the informants use online communities as a place to exchange experiential knowledge and as a supportive space for handling the medical treatment. Despite the proven need for online communities, patients also want guidance on how to connect with physical diabetes communities because they find it difficult to get an overview of the options open to them. Community pharmacies are used by 95% of all citizens and are an obvious place to gather and distribute information about local communities.72 Another advantage is their broad public accessibility, as citizens can use community pharmacies without an appointment and obtain counselling from trained healthcare professionals on the safe, effective use of medication and on disease prevention.3,6 The next step is to make sure that persons who pick up diabetes medication become aware of this.

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS

To our knowledge, this is the first time that persons with diabetes in Denmark have been asked what they want from community pharmacies in terms of support on how to manage their complex treatment regimen. We believe our findings provide new knowledge about how community pharmacies should act to provide services independently of the healthcare system at large. Such services could include counselling and other existing pharmacy services as mentioned above (the New Medicine, or the Medication Adherence Service). In the focus group interviews, the informants were asked about what they want from community pharmacies, which means that we cannot conclude from this study what persons with diabetes want from other healthcare professionals.

By running both a physical and an online focus group interview, we succeeded in recruiting participants from a much broader geographical area than if we had conducted two physical interviews. However, two informants declined to participate due to the online format. One had poor eyesight and the other was weary of online meetings. We consider our failure to recruit younger persons with diabetes and more male informants and the fact that fewer informants have type 1 diabetes than type 2 diabetes a limitation. A broader range of ages, diabetes duration, diagnoses and a more equal distribution of gender may have produced other findings.

The focus group interviews were not completed as planned owing to the COVID-19 situation in Denmark. The hygiene restrictions during the physical meeting prevented us from using written statements which may have stimulated more reflections beyond the informants’ assumptions. At the physical meeting, the informants kept the recommended distance from each other, making it difficult to initiate interaction and meaning that sub-discussions in smaller groups took place only occasionally. The online facilitator role was easier, however. Everyone could see each other, and informants considerately allowed each other to speak and respected the ‘raise your hand’ function. Only minor technical difficulties occurred during the online interview. For example, an internet connection failure meant one person had to log off and on again.

Our results showed that online participation had a positive effect – lower dropout rates, broader geographical representation and minimal technical issues, all consistent with the findings of a review regarding online interviews conducted during the pandemic.73 In addition, no differences were discovered in the data despite the two different collection methods. Online data collection seems to be a way of reaching participants normally reluctant to participate. In our study, the online part was less time-consuming and less costly, as also identified in the review of online interviews.73

CONCLUSIONS

Informants in this study did not regard community pharmacies as a natural part of the healthcare system or as a place where they would expect counselling, although they regularly pick up their medication there. They would like the community pharmacy to make their services and the medical competences of pharmacy staff obvious. Informants experience a gap in their healthcare in the periods between routine visits and suggest that community pharmacies counselling services become a natural supplement between routine healthcare visits and that healthcare professionals in the primary and secondary sectors inform patients about the services and competences available at the community pharmacies.

Informants in this study would like the community pharmacies (aim 1) to act as a dialogue partner and would like to receive competent counselling on their medication, how to postpone comorbidities and complications, information about practical equipment and relevant health apps and information about local diabetes communities. They would also like more personal dialogue about worries about and challenges with diabetes and medication to avoid feeling alone and having to self-manage.

In terms of how community pharmacies can meet these wishes (aim 2), informants in this study suggest that the community pharmacies raise awareness of their competences and services and that the pharmacy staff are aware of patients’ needs when they pick up medication, especially as regards patients newly diagnosed with diabetes. In addition, informants would like to have a contact person at the community pharmacy with special diabetes competences with whom they can book an appointment when they need additional counselling to complement over-the-counter counselling. Finally, they would like a formal collaboration between diabetes associations and community pharmacies to make their competences, services, and information visible to the patients. Further research should focus on two issues: 1) How to create a formal collaboration between community pharmacies and diabetes associations to help persons with diabetes discover both parties’ competences and services and 2) how community pharmacies can reach out to persons with diabetes – and it should then be evaluated whether these two actions are a supportive supplement to existing offers to persons with diabetes.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful to the study participants for sharing their time and expertise with us for this study.

Contributor Information

Gitte Reventlov Husted, PhD, MScN, Consultant, Department of Research and Development, Danish College of Pharmacy Practice, Pharmakon, Denmark. grh@pharmakon.dk,.

Rikke Nørgaard Hansen, MSc Pharmacy, Head of Research and Development, Danish College of Pharmacy Practice, Pharmakon, Denmark. rnh@pharmakon.dk.

Mira El-Souri, MSc Pharmacy, Consultant, Department of Research and Development, Danish College of Pharmacy Practice, Pharmakon, Denmark. mso@pharmakon.dk.

Janne Kunchel Lorenzen, Programme Director, PhD. Steno Diabetes Center Sjælland, Denmark. jalor@regionsjaelland.dk.

Peter Bindslev Iversen, Programme Director, PhD. Steno Diabetes Center Sjælland, Denmark. peiv@regionsjaelland.dk.

Charlotte Verner Rossing, PhD, MSc. Pharmacy, Director of Research and Development, Danish College of Pharmacy Practice, Pharmakon, Denmark. cr@pharmakon.dk.

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors have read and approved the final manuscript. All authors are involved in the conception of the study and have contributed to the design of the study. GRH has collected the data and MSO and GHR have analyzed the data and subsequently discussed the results with all the authors. GRH drafted the manuscript with all authors providing critical and final approval.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declared no conflicts of interest with respect to the authorship and/or publication of this paper.

FUNDING

This work was supported by Steno Diabetes Centre Sjaelland, Denmark. The Association of Danish Pharmacies and Danish College of Pharmacy Practice, Pharmakon, Denmark.

References

- 1.International Diabetes Federation. IDF Diabetes Atlas 2019. Available from: https://www.diabetesatlas.org/en/

- 2.Draznin Boris, Aroda Vanita R, Bakris George, et al. Classification and Diagnosis of Diabetes:Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes-2022. Diabetes Care. 2022;45(1):S17–S38. doi: 10.2337/dc22-S002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Holt Richard IG, DeVries Hans J, et al. The management of type 1 diabetes in adults. A consensus report by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD) Diabetes Care. 2021;44(11):2589–2625. doi: 10.2337/dci21-0043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dansk Selskab for Almen Medicin. Farmakologisk behandling af type 2 diabetes. Fælles retningslinje fra DES og DSAM 2022 (The Danish College of General Practitioners. Pharmacological treatment of type 2 diabetes. Guidelines) [cited 2022 0406] Available from: https://vejledninger.dsam.dk/fbv-t2dm/

- 5.Payal HM, Gao Helen X, et al. American Diabetes Association Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes 2017. Wiley Online Library. 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meneghini Luigi. Medical Management of Type 2 Diabetes:American Diabetes Association. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dansk Selskab for Almen Medicin. Type 2 diabetes opfølgning og behandling (The Danish College of General Practitioners, Type 2 diabetes, follow-up and treatment) 2022. [cited 2022 0404] Available from: https://vejledninger.dsam.dk/type2/

- 8.Sohal TanveerSohal, Parmjit King-Shier, et al. Barriers and facilitators for type-2 diabetes management in South Asians:a systematic review. PloS one. 2015;10(9):e0136202. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0136202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khan Hamida, Lasker Shawarna S, et al. Exploring reasons for very poor glycaemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes. Primary Care Diabetes. 2011;5(4):251–255. doi: 10.1016/j.pcd.2011.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Dijk Marloes, Blom Lyda, et al. Patient–provider communication about medication use at the community pharmacy counter. International Journal of Pharmacy Practice. 2016;24(1):13–21. doi: 10.1111/ijpp.12198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blom Lyda, Wolters Majanne, et al. Pharmaceutical education in patient counseling:20 h spread over 6 years? Patient Education and Counseling. 2011;83(3):465–471. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2011.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alkhawajah AM, Eferakeya AE. The role of pharmacists in patients'education on medication. Public Health. 1992;106(3):231–237. doi: 10.1016/s0033-3506(05)80541-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hepler CD, Strand LM. Opportunities and responsibilities in pharmaceutical care. Am J Hosp Pharm. 1990;47(3):533–543. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pharmaceutical Group of the European Union (PGEU) Annual Report 2019. [cited 2021 3/9] Available from: https://www.pgeu.eu/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/200402-PGEU-Annual-Report-2019.pdf .

- 15.Dhippayom Teerapon, Krass Ines. Supporting self-management of type 2 diabetes:is there a role for the community pharmacist? Patient preference and adherence. 2015;9:1085. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S88071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Doucette WR, Witry MJ, Farris KB, et al. Community pharmacist-provided extended diabetes care. Ann Pharmacother. 2009;43(5):882–889. doi: 10.1345/aph.1L605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Seidman Kimberly, Fit Kathy E. Areas for improving care of type 1 diabetes:A role for pharmacists. Journal of the American Pharmacists Association. 2008;48(3):333–334. doi: 10.1331/japha.2008.08041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hansen Rikke, Nørgaard Lotte S, et al. Integration of and visions for community pharmacy in primary health care in Denmark. Pharmacy Practice. 2021;19(1) doi: 10.18549/PharmPract.2021.1.2212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kjeldsen LJ, Bjerrum L, Dam P, et al. Safe and effective use of medicines for patients with type 2 diabetes - A randomized controlled trial of two interventions delivered by local pharmacies. Research in social &administrative pharmacy:RSAP. 2015;11(1):47–62. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2014.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mossialos Elias, Courtin Emilie, et al. From “retailers”to health care providers:transforming the role of community pharmacists in chronic disease management. Health Policy. 2015;119(5):628–39. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2015.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Agomo CO. The role of community pharmacists in public health:a scoping review of the literature. Journal of Pharmaceutical Health Services Research. 2012;3(1):25–33. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Community Pharmacy Forward view. Voice Pharmacy. [cited 2020 September 16th] Available from: https://psnc.org.uk/national-pharmacy-services/community-pharmacy-forward-view/

- 23.Next Steps on the NSH. Five Year Forward View 2017. England NSH. [cited 2020 September 16th] Available from: https://psnc.org.uk/national-pharmacy-services/community-pharmacy-forward-view/

- 24.Hindi Ali MK, Schafheutle Ellen I, et al. Community pharmacy integration within the primary care pathway for people with long-term conditions:a focus group study of patients', pharmacists'and GPs'experiences and expectations. BMC Family Practice. 2019;20(1):26. doi: 10.1186/s12875-019-0912-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pousinho Sarah, Morgado Manuel, et al. Clinical pharmacists´interventions in the management of type 2 diabetes mellitus:a systematic review. Pharmacy Practice. 2020;18(3):2000. doi: 10.18549/PharmPract.2020.3.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hindi Ali MK, Jacobs Sally, et al. Solidarity or dissonance?A systematic review of pharmacist and GP views on community pharmacy services in the UK. Health &Social Care in the Community. 2019;27(3):565–598. doi: 10.1111/hsc.12618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hall NJ, Donovan Gemma, et al. A qualitative synthesis of pharmacist, other health professional and lay perspectives on the role of community pharmacy in facilitating care for people with long-term conditions. Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy. 2018;14(11):1043–1057. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2018.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hindi Ali MK, Schafheutle Ellen I, et al. Patient and public perspectives of community pharmacies in the United Kingdom:A systematic review. Health Expectations. 2018;21(2):409–428. doi: 10.1111/hex.12639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lutfun NH, Fernandez-Llimos Fernando, et al. Qualitative meta-synthesis of barriers and facilitators that influence the implementation of community pharmacy services:perspectives of patients, nurses and general medical practitioners. BMJ open. 2017;7(9):e015471. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-015471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Halkier Bente. Fokusgrupper (Focusgroup) 3 ed. Denmark: Samfundslitteratur; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dominik GC. What is going through your mind?Thinking aloud as a method in cross-cultural psychology. Frontiers in Psychology. 2018;9:1292. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Castensøe-Seidenfaden P, Teilmann G, Kensing F, Hommel E, Olsen BS, Husted GR. Isolated thoughts and feelings and unsolved concerns:adolescents'and parents'perspectives on living with type 1 diabetes–a qualitative study using visual storytelling. Journal of clinical nursing. 2017;26(19-20):3018–3030. doi: 10.1111/jocn.13649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Norman KD, Lincoln Yvonna S. The Sage handbook of qualitative research:sage. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Braun Virginia, Clarke Victoria, et al. Thematic analysis. Handbook of Research Methods in Health Social Sciences. 2019:843–860. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Guba EG. Criteria for assessing the trustworthiness of naturalistic inquiries. Ectj. 1981;29(2):75–91. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Justitsministeriet. Bekendtgørelse om ændring af bekendtgørelse om undtagelse fra pligten til anmeldelse af visse behandlinger, som foretages for en privat dataansvarlig:BEK nr. 410 af 09/05/2012 [Decree amending the decree on exemption from the obligation to declare certain procedures which are made for a private data controller:order no. 410 of 09/05/2012][cited 2020 10th September] Available from: https://www.retsinformation.dk/Forms/R0710.aspx?id=141758 .

- 37.WMA Declaration of Helsinki - Ethical principles for medical research involvning human subjects. Association World Medical. [cited 2020 10th September] Available from: https://www.wma.net/policies-post/wma-declaration-of-helsinki-ethical-principles-for-medical-research-involving-human-subjects/

- 38.Abrahamsen Bjarke, Burghle Hassan A, Rossing C. Pharmaceutical care services available in Danish community pharmacies. International Journal of Clinical Pharmacy. 2020;42(2):315–320. doi: 10.1007/s11096-020-00985-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Naughton Cynthia A. Patient-centered communication. Pharmacy. 2018;6(1):18. doi: 10.3390/pharmacy6010018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wolters Majanne, Hulten Rolf V, et al. Exploring the concept of patient centred communication for the pharmacy practice. International Journal of Clinical Pharmacy. 2017;39(6):1145–1156. doi: 10.1007/s11096-017-0508-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zoffmann Vibeke, Harder Ingegerd, et al. A person-centered communication and reflection model:sharing decision-making in chronic care. Qualitative Health Research. 2008;18(5):670–685. doi: 10.1177/1049732307311008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Juul Lise, Maindal Helle T, Zoffmann Vibeke, et al. Effectiveness of a training course for general practice nurses in motivation support in type 2 diabetes care:a cluster-randomised trial. PloS one. 2014;9(5):e96683. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0096683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Husted GR, Esbensen BA, Hommel E, et al. Adolescents developing life skills for managing type 1 diabetes:a qualitative, realistic evaluation of a guided self-determination-youth intervention. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2014;70(11):2634–2650. doi: 10.1111/jan.12413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Perrault Evan K, Newlon Jenny L. Patients'knowledge about pharmacists, technicians, and physicians. American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy. 2019;76(18):1420–1425. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/zxz169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lee Lyn E, Wong Se P, et al. What role could community pharmacists in Malaysia play in diabetes self-management education and support?The views of individuals with type 2 diabetes. International Journal of Pharmacy Practice. 2018;26(2):138–147. doi: 10.1111/ijpp.12374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McMillan Sara S, Kelly Fiona, Sav A, et al. Consumer and carer views of Australian community pharmacy practice:awareness, experiences and expectations. Journal of Pharmaceutical Health Services Research. 2014;5(1):29–36. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bawab Noura, Zuercher Emilie, et al. Interest in and use of person-centred pharmacy services-a Swiss study of people with diabetes. BMC Health Services Research. 2021;21(1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12913-021-06217-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.MacCallum Lori, Dolovich Lisa. Follow-up in community pharmacy should be routine, not extraordinary. SAGE Publications Sage CA:Los Angeles, CA. 2018;151(2):79–81. doi: 10.1177/171516351∴586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cheng AY. Canadian Diabetes Association 2013 clinical practice guidelines for the prevention and management of diabetes in Canada. Introduction. Canadian Journal of Diabetes. 2013;37(1):S1–3. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjd.2013.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Reeves Landon, Robinson Kristian, et al. Pharmacist interventions in the management of blood pressure control and adherence to antihypertensive medications:a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Journal of Pharmacy Practice. 2021;34(3):480–492. doi: 10.1177/0897190020903573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lakey Hannah, Boehmer Kaci, et al. Impact of a Pharmacist-Led Group Diabetes Class. Journal of Pharmacy Practice. 2020;35(1):54–56. doi: 10.1177/0897190020948678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Smith AM, Hamann Gale L, et al. Evaluation of the Addition of Pharmacist Management to a Medication Assistance Program in Patients with Hypertension and Diabetes Resistant to Usual Care. Journal of Pharmacy Practice. 2021:08971900211002138. doi: 10.1177/08971900211002138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Alsuwayni Bashayr, Alhossan Abdulaziz. Impact of clinical pharmacist-led diabetes management clinic on health outcomes at an academic hospital in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia:A prospective cohort study. Saudi Pharmaceutical Journal. 2020;28(12):1756–1759. doi: 10.1016/j.jsps.2020.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Frederick Amy, Juan Joyce, et al. Effect of Visit Frequency of Pharmacist-Led Diabetes Medication Management Program. Journal of Pharmacy Practice. 2022;35(1):70–74. doi: 10.1177/0897190020948685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shareef Javedh, Fernandes Jennifer, et al. Evaluating the effect of pharmacist's delivered counseling on medication adherence and glycemic control in patients with diabetes mellitus. J Diabetes Metab. 2016;7(3):100654. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jan JKL, Brammer Diane J, et al. Effectiveness of educational interventions to promote oral hypoglycaemic adherence in adults with type 2 diabetes:A systematic review. JBI Evidence Synthesis. 2011;9(9):269–312. doi: 10.11124/01938924-201008081-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Deters MA, Laven Anna, et al. Effective interventions for diabetes patients by community pharmacists:a meta-analysis of pharmaceutical care components. Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 2018;52(2):198–211. doi: 10.1177/1060028017733272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fonseca Joseph, Violette Richard, et al. Helping Unlock Better Care (HUB|C) using quality improvement science in community pharmacies–An implementation method. Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy. 2021;17(3):572–577. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2020.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Houle Sherilyn KD, Grindrod Kelly A, et al. Paying pharmacists for patient care:a systematic review of remunerated pharmacy clinical care services. Canadian Pharmacists Journal/Revue des Pharmaciens du Canada. 2014;147(4):209–232. doi: 10.1177/1715163514536678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Benrimoj Shalom I, Fernandez-Llimos Fernando. An international series on the integration of community pharmacy in primary health care. Pharmacy Practice (Granada) 2020;18(1):1878. doi: 10.18549/PharmPract.2020.1.1878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Anderson Claire, Sharma Ravi. Primary health care policy and vision for community pharmacy and pharmacists in England. Pharmacy Practice (Granada) 2020;18(1):1870. doi: 10.18549/PharmPract.2020.1.1870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Henman Martin C. Primary Health Care and Community Pharmacy in Ireland:A lot of visions but little progress. Pharmacy Practice. 2020;18(4):2224. doi: 10.18549/PharmPract.2020.4.2224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Raiche Taylor, Pammett Robert, et al. Community pharmacists'evolving role in Canadian primary health care:a vision of harmonization in a patchwork system. Pharmacy Practice. 2020;18(4):2171. doi: 10.18549/PharmPract.2020.4.2171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Dineen-Griffin Sarah, Benrimoj Shalom I, et al. Primary health care policy and vision for community pharmacy and pharmacists in Australia. Pharmacy Practice (Granada) 2020;18(2):1967. doi: 10.18549/PharmPract.2020.2.1967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Salgado M. Teresa, Rosenthal Meagen M, et al. Primary healthcare policy and vision for community pharmacy and pharmacists in the United States. Pharm Pract (Granada) 2020;18(3):2160. doi: 10.18549/PharmPract.2020.3.2160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Riberio Nadine, Mota-Filipe Helder, et al. Primary health care policy and vision for community pharmacy and pharmacists in Portugal. Pharm Pract (Granada) 2020;18(3):2043. doi: 10.18549/PharmPract.2020.3.2043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Westerlund Tommy, Marklund Bertil. Community pharmacy and primary health care in Sweden-at a crossroads. Pharm Pract. 2020;18(2):1927. doi: 10.18549/PharmPract.2020.2.1927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Armando Pedro D, Uema Sonia A, et al. Integration of Community pharmacy and pharmacists in primary health care policies in Argentina. Pharm Pract. 2020;18(4):2173. doi: 10.18549/PharmPract.2020.4.2173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hallit Souheil, Selwan Abou C, et al. Primary health care policy and vision for community pharmacy and pharmacists in Lebanon. Pharm Pract (Granada) 2020;18(2):2003. doi: 10.18549/PharmPract.2020.2.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hermansyah Andi, Wulandari Luh, et al. Primary health care policy and vision for community pharmacy and pharmacists in Indonesia. Pharm Pract (Granada) 2020;18(3):2085. doi: 10.18549/PharmPract.2020.3.2085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kingod N, Cleal B, Wahlberg A, et al. Online Peer-to-Peer Communities in the Daily Lives of People with Chronic Illness:A Qualitative Systematic Review. Qualitative health research. 2017;27(1):89–99. doi: 10.1177/1049732316680203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.The Association of Danish Pharmacies. Lægemidler i Danmark 2019-2020. [(accessed November 11th, 2020). 2020]. Available in Danish at: https://www.apotekerforeningen.dk/publikationer/analyser-og-fakta/aarbog-laegemidler-i-danmark .

- 73.Halliday Matthew, Mill Deanna, et al. Let's talk virtual!Online focus group facilitation for the modern researcher. Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy. 2021;17(12):2145–2150. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2021.02.00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]