Abstract

PURPOSE

For real-world evidence, it is convenient to use routinely collected data from the electronic medical record (EMR) to measure survival outcomes. However, patients can become lost to follow-up, causing incomplete data and biased survival time estimates. We quantified this issue for patients with metastatic cancer seen in an academic health system by comparing survival estimates from EMR data only and from EMR data combined with high-quality cancer registry data.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients diagnosed with metastatic cancer from 2008 to 2014 were included in this retrospective study. Patients who were diagnosed with cancer or received their initial treatment within our system were included in the institutional cancer registry and this study. Overall survival was calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method. Survival curves were generated in two ways: using EMR follow-up data alone and using EMR data supplemented with data from the Stanford Cancer Registry/California Cancer Registry.

RESULTS

Four thousand seventy-seven patients were included. The median follow-up using EMR + Cancer Registry data was 19.9 months, and the median follow-up in surviving patients was 67.6 months. There were 1,301 deaths recorded in the EMR and 3,140 deaths recorded in the Cancer Registry. The median overall survival from the date of cancer diagnosis using EMR data was 58.7 months (95% CI, 54.2 to 63.2); using EMR + Cancer Registry data, it was 20.8 months (95% CI, 19.6 to 22.3). A similar pattern was seen using the date of first systemic therapy or date of first hospital admission as the baseline date.

CONCLUSION

Using EMR data alone, survival time was overestimated compared with EMR + Cancer Registry data.

INTRODUCTION

Routinely collected data from the electronic medical record (EMR) show great promise for studying outcomes of cancer treatments and creating predictive models.1,2 Many studies have used EMR data to measure survival outcomes such as overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival.3,4 Use of EMR survival data is attractive because it is readily available, free, and timely, unlike databases such as the National Death Index (NDI) that have a substantial time lag before death data become available. However, EMR follow-up information is known to be incomplete for many reasons, such as patients transferring care to other centers.5 This could result in biased estimates of survival time.6 We sought to quantify the magnitude of this issue for patients with metastatic cancer seen in an academic health care system by comparing survival estimates generated in two ways: with EMR data only and with EMR data combined with high-quality cancer registry data. We chose this patient population for analysis because cancer registry follow-up data were available and the high mortality rate of metastatic cancer meant that there would be sufficient death events for analysis.

CONTEXT

Key Objective

To determine whether electronic medical record (EMR) data provide accurate estimates of survival time for patients diagnosed with metastatic cancer.

Knowledge Generated

Survival time was greatly overestimated when using electronic medical data alone, compared with a higher-quality data source that included cancer registry data. A majority of deaths were not recorded in the EMR.

Relevance

For real-world evidence studies and predictive models that use survival end points, if the only data source is the EMR, then results may be misleading.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient Population

One EMR has been used in the Stanford Health Care system for inpatient and outpatient care since 2008 (Epic, Verona, WI). The EMR was used at one tertiary care hospital, one freestanding cancer center, and multiple outpatient clinics. We used the Stanford Cancer Registry to identify patients age 18 years or older diagnosed with cancer from February 29, 2008 (when the current EMR entered broad use), to December 31, 2014. Patients were included in the cancer registry if they were diagnosed with cancer or received their initial treatment in the Stanford Health Care system. Patients were only included in this study if they had distant metastases at the time of cancer diagnosis as indicated by either clinical or pathologic staging. For patients diagnosed with multiple metastatic cancers, only the one with the earliest diagnosis date was used. Patients with no follow-up data available in the EMR or Cancer Registry were excluded. Only patients with at least one clinical note after the date of cancer diagnosis were included because we only wanted to include patients who received some care in our health system, and a completed encounter without a note was unlikely to represent substantial interaction.

Dates of systemic therapy administration or prescriptions were identified by matching EMR records to a custom list of 231 antineoplastic systemic therapies. Dates of hospitalization were recorded from the EMR. Patient demographics were obtained from the cancer registry.

Survival Estimation Methods

We compared two data sources for survival estimation. For the EMR-only source, alive/dead status, date of last follow-up/contact, and date of death were obtained from the EMR (Epic, Verona, WI). For patients not known to be deceased, date of last follow-up was the last date of a completed hospital, clinic, telephone, or virtual encounter.

For the EMR + Cancer Registry data source, EMR vital status information was supplemented with data from the Stanford Cancer Registry. The Stanford Cancer Registry receives vital status information yearly from the California Cancer Registry (CCR). The CCR is one of the registries used in the SEER program, and since 1988, all cancers diagnosed in California are required to be reported to the CCR. The CCR has rigorous methods to determine the death date or for patients not known to be deceased, the date of last follow-up/contact.7,8 Death data are obtained from the NDI, Social Security Death Master File, death certificates, and other sources. The date of last contact is determined using hospital data, driver's license applications, Medicare data, and others. See the variable Follow-Up Last Type Patient in the CCR data dictionary for a full list of data sources.8 Because of the inclusion of NDI data, the result is very close to a complete death data set.9,10 When a death date was recorded in both the EMR and Stanford Cancer Registry, in > 95% of cases, the two dates were identical. In the small proportion of cases where the two dates differed, the date from the EMR was used, because of a coding decision in the database that was made before this study was performed. For patients not known to be deceased, the date of last follow-up from either EMR or Cancer Registry was used, whichever was later.

Death and follow-up data were right-truncated at the end of 2019 to ensure complete data from the Cancer Registry and at least 5 years of potential follow-up for all patients. Therefore, patients with death or last follow-up recorded after 2019 were marked as alive with last follow-up on December 31, 2019.

Statistical Analysis

Survival time was calculated from several baseline time points: date of cancer diagnosis, date of first systemic therapy after cancer diagnosis (if any), and date of first hospitalization after cancer diagnosis (if any). For each baseline time point, only patients for whom that time point was in 2014 or earlier were included (eg, if a patient was diagnosed with cancer in 2014, but their first hospitalization was not until 2016, they would not be included in the hospitalization analysis). Survival distribution was calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method. Patients not known to be deceased were censored at the time of last follow-up. To compare survival distribution between the two data sources, a Cox proportional hazards model was fit with the data source as the single predictor and a hazard ratio was calculated. The data set used for fitting the Cox model had two rows per patient: one row for EMR follow-up data and the other row for EMR + Cancer Registry follow-up data.

Analysis was performed using R version 3.6.2. This retrospective study was approved by our institution's institutional review board.

RESULTS

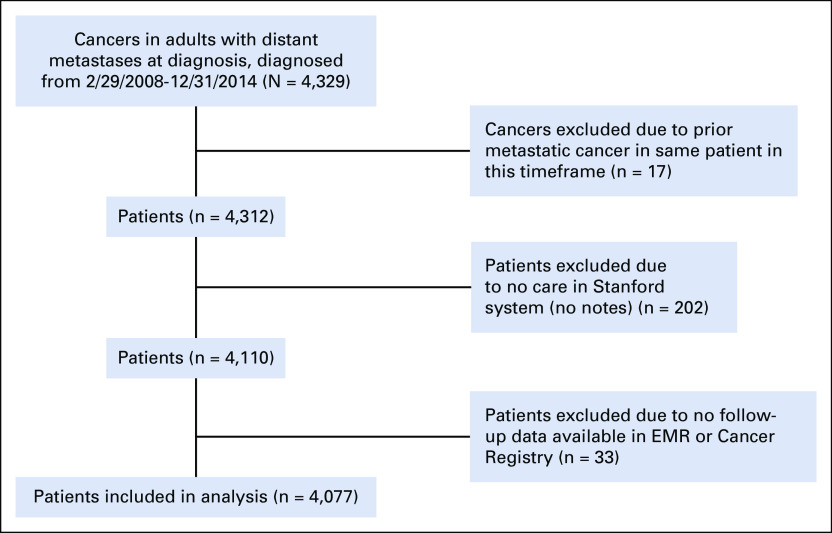

There were 4,077 patients included in the Stanford Cancer Registry who were diagnosed with metastatic cancer between 2008 and 2014 and were eligible for the current analysis. Figure 1 shows the number of patients excluded for the reasons mentioned in the Materials and Methods section. Patient characteristics are listed in Table 1. There were 1,301 deaths recorded in the EMR and 3,140 deaths recorded in the Cancer Registry. There were no deaths recorded in the EMR but not in the Cancer Registry. The median follow-up using EMR alone was 14.5 months, compared with 19.9 months when using EMR + Cancer Registry data. For patients not marked as deceased in either source, the median follow-up using EMR alone was 54.0 months, compared with 67.6 months when using EMR + Cancer Registry data. For patients marked as deceased in Cancer Registry but not EMR, the median time from last recorded EMR follow-up to death was 1.8 months (first/third quartiles: 0.7/5.4 months).

FIG 1.

Flow diagram showing included patients. EMR, electronic medical record.

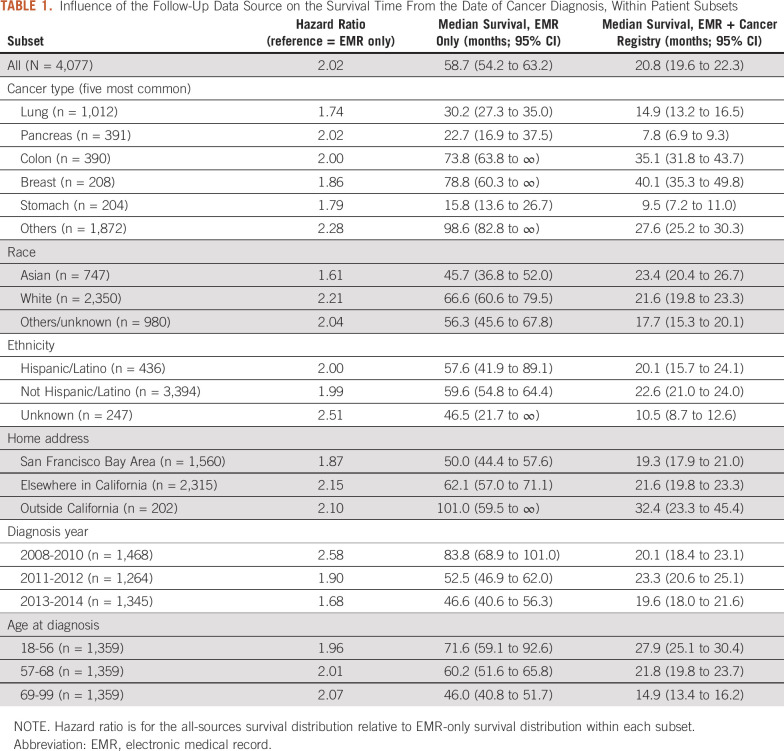

TABLE 1.

Influence of the Follow-Up Data Source on the Survival Time From the Date of Cancer Diagnosis, Within Patient Subsets

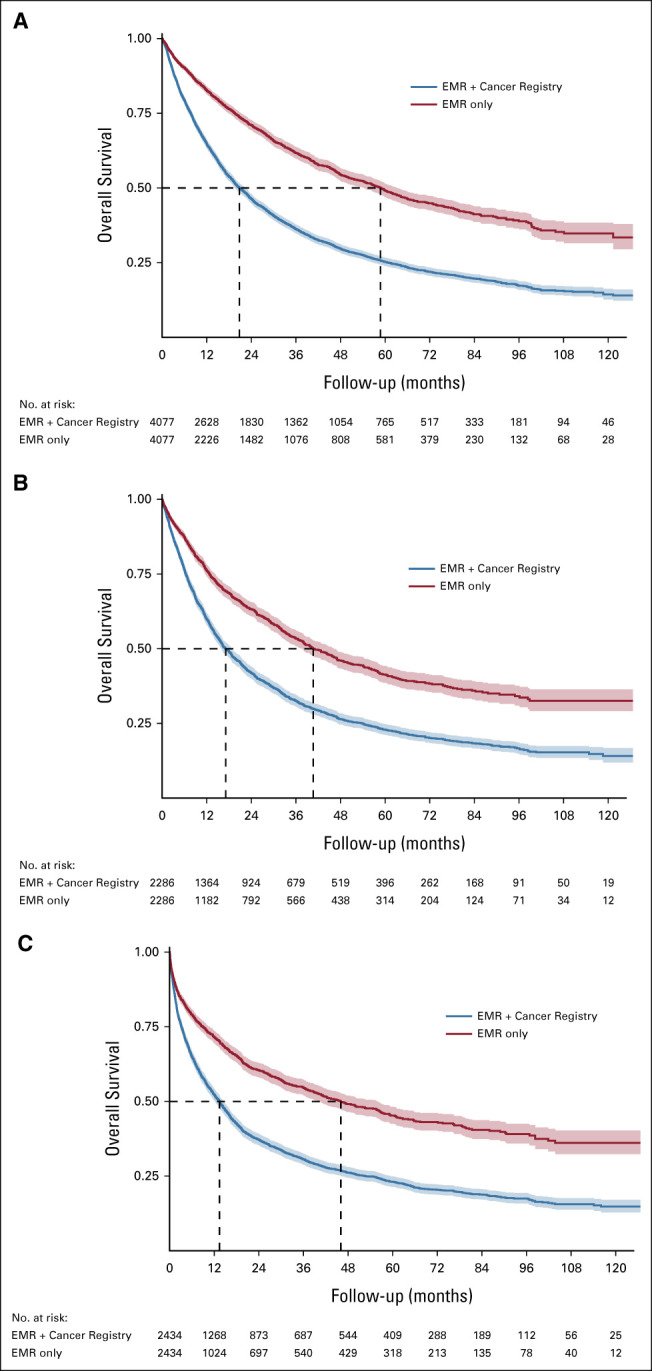

Survival distributions using EMR-only versus EMR + Cancer Registry data are shown in Figure 2. The median OS from the date of cancer diagnosis using EMR data was 58.7 months (95% CI, 54.2 to 63.2); using EMR + Cancer Registry data, it was 20.8 months (95% CI, 19.6 to 22.3). The hazard ratio for the EMR + Cancer Registry data compared to EMR data was 2.02. There were 2,286 patients who received systemic anticancer therapy. Using the date of first systemic therapy as the baseline instead of the diagnosis date, the median OS for EMR versus EMR + Cancer Registry data sources was 40.7 months (95% CI, 37.6 to 46.2) versus 17.1 months (95% CI, 15.9 to 18.7) and the hazard ratio was 1.76. There were 2,434 patients with hospitalization after cancer diagnosis. Using the first admission date as the baseline, the median OS for EMR versus EMR + Cancer Registry data sources was 46.1 months (95% CI, 40.0 to 55.9) versus 13.4 months (95% CI, 12.2 to 14.4) and the hazard ratio was 1.86. Results within patient subgroups are shown in Table 1.

FIG 2.

OS distributions using EMR only versus EMR + Cancer Registry data, estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method: (A) time from cancer diagnosis, (B) time from first systemic therapy, and (C) time from first hospitalization. Shaded bands indicate 95% CIs. EMR, electronic medical record; OS, overall survival.

DISCUSSION

For patients with metastatic cancer seen for inpatient or outpatient care in an academic health care system, only 41% of deaths were captured in the EMR. As a result, using EMR data alone caused survival time to be severely overestimated compared with using EMR + Cancer Registry data. This pattern was present across patient subgroups and baseline time points (time of diagnosis, first systemic therapy, and first hospitalization). A previous study of community oncology practices had similar findings: 66% of deaths were recorded in the EMR, using NDI as a gold standard, resulting in upward bias of the survival curve.6

It is not surprising that many deaths occurring at home or at outside facilities were not recorded in the EMR since the EMR is mainly used for patient care and billing, and recording deceased patients' exact date of death is not essential for either of these functions. For deceased patients not recorded as deceased in the EMR, there was a small median difference of 1.8 months from last EMR follow-up to death. Therefore, many of these patients were being seen regularly at our institution but died elsewhere and our staff were either not notified or failed to record the death. This suggests that the bias in survival estimates is not just due to patients transferring outpatient care to other centers.

The overestimation of survival time in the EMR-only data set is likely due to informative censoring: sicker patients who are closer to death are more likely to be lost to follow-up. For instance, patients who travel to an academic center for a clinical trial of a new treatment may stop coming when the treatment stops working well; patients who enroll on hospice usually cancel all their other medical appointments. This is a fundamental issue that cannot be easily overcome by statistical corrections such as inverse probability of censoring weighting since all subgroups showed a large bias in the same direction.11 Using supplemental data sources can increase sensitivity, but many deaths are missing in commonly used sources such as the Social Security Administration Death Master File.6,12

The observed pattern could cause misleading results from real-world evidence studies that, for instance, include patients receiving a specific treatment and compare the observed survival distribution to that seen in prior clinical trials. It would also cause predictive models to be miscalibrated and predict overly long survival time. Although some mortality prediction models are trained using high-quality data sources such as national health system databases, there are many counterexamples.13,14

There are several limitations to this study. First, we only evaluated EMR data from one academic health care system located in a region with many competing centers; it is possible that other institutions have more complete EMR data or that data could be made more complete by pooling data from multiple centers. Second, we only used structured EMR data for this analysis. It is likely that some patients had EMR notes stating that the patient was deceased, and manually going through notes could have increased accuracy. However, this is unlikely to substantially increase completeness, as a previous study showed only a 2% increase in sensitivity for detecting death by manually reviewing charts.6

In summary, for retrospective studies evaluating survival end points, use of EMR follow-up data alone is likely to severely overestimate the survival time. We recommend that such data are supplemented with more complete data from sources such as the NDI or other registries.

Michael F. Gensheimer

Employment: Roche/Genentech (I)

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Roche/Genentech (I)

Research Funding: Varian Medical Systems

Open Payments Link:

Balasubramanian Narasimhan

Consulting or Advisory Role: Genentech

A. Solomon Henry

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Pfizer

Daniel L. Rubin

Consulting or Advisory Role: Roche/Genentech

Research Funding: GE Healthcare (Inst), Philips Healthcare (Inst)

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: Several pending patents on AI algorithms (Inst)

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

SUPPORT

Supported in part by the National Cancer Institute (Cancer Center Support Grant number 5P30CA124435) and National Institutes of Health/National Center for Research Resources (CTSA award number UL1 RR025744). B.N.'s work was funded by Stanford Clinical & Translational Science Award grant 5UL1TR003142-02 from the NIH National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Michael F. Gensheimer, Daniel L. Rubin

Collection and assembly of data: Michael F. Gensheimer, A. Solomon Henry, Douglas J. Wood

Data analysis and interpretation: Michael F. Gensheimer, Balasubramanian Narasimhan

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated unless otherwise noted. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/cci/author-center.

Open Payments is a public database containing information reported by companies about payments made to US-licensed physicians (Open Payments).

Michael F. Gensheimer

Employment: Roche/Genentech (I)

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Roche/Genentech (I)

Research Funding: Varian Medical Systems

Open Payments Link:

Balasubramanian Narasimhan

Consulting or Advisory Role: Genentech

A. Solomon Henry

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Pfizer

Daniel L. Rubin

Consulting or Advisory Role: Roche/Genentech

Research Funding: GE Healthcare (Inst), Philips Healthcare (Inst)

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: Several pending patents on AI algorithms (Inst)

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Di Maio M, Perrone F, Conte P.Real-world evidence in oncology: Opportunities and limitations Oncologist 25e746–e7522020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hersh WR, Weiner MG, Embi PJ, et al. Caveats for the use of operational electronic health record data in comparative effectiveness research Med Care 51S30–S372013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sperduto PW, Yang TJ, Beal K, et al. Estimating survival in patients with lung cancer and brain metastases: An update of the graded prognostic assessment for lung cancer using molecular markers (Lung-molGPA) JAMA Oncol 3827–8312017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shafqat H, Gourdin T, Sion A.Immune-related adverse events are linked with improved progression-free survival in patients receiving anti-PD-1/PD-L1 therapy Semin Oncol 45156–1632018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clarke CA, Glaser SL, Leung R, et al. Prevalence and characteristics of cancer patients receiving care from single vs. multiple institutions Cancer Epidemiol 4627–332017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Curtis MD, Griffith SD, Tucker M, et al. Development and validation of a high-quality composite real-world mortality endpoint Health Serv Res 534460–44762018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Benjamin DJ, Klapheke A, Lara PN, et al. A population-based study of incidence and survival of 1588 thymic malignancies: Results from the California Cancer Registry Clin Lung Cancer 20477–4832019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.California Cancer Registry . California Cancer Registry Research Data Dictionary. 2020. https://www.ccrcal.org/wpfd_file/california-cancer-registry-research-data-dictionary-march-2020_v1-1/ [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eisenstein E, Curtis L, Prather K, et al. NIH Collaboratory Living Textbook of Pragmatic Clinical Trials. 2020. Using death as an endpoint.https://rethinkingclinicaltrials.org/chapters/design/choosing-specifying-end-points-outcomes/using-death-as-an-endpoint/ [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johnson CJ, Weir HK, Fink AK, et al. The impact of National Death Index linkages on population-based cancer survival rates in the United States Cancer Epidemiol 3720–282013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Willems S, Schat A, van Noorden M, et al. Correcting for dependent censoring in routine outcome monitoring data by applying the inverse probability censoring weighted estimator Stat Methods Med Res 27323–3352018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Levin MA, Lin H, Prabhakar G, et al. Alive or dead: Validity of the social security administration death master file after 2011 Health Serv Res 5424–332019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Adler ED, Voors AA, Klein L, et al. Improving risk prediction in heart failure using machine learning Eur J Heart Fail 22139–1472020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nguyen OK, Makam AN, Clark C, et al. Vital signs are still vital: Instability on discharge and the risk of post-discharge adverse outcomes J Gen Intern Med 3242–482017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]