Abstract

Introduction

Traditional, complementary and alternative medicine (TCAM) refers to a broad range of health practices and products typically not part of the 'conventional medicine' system, and its use is substantial among the general population. TCAM products and therapies may be used in addition to, or instead of, conventional medicine approaches, and some have been associated with adverse reactions or other harms.

Objectives

The aims of this systematic review were to identify and examine recently published national studies globally on the prevalence of TCAM use in the general population, to review the research methods used in these studies and to propose best practices for future studies exploring prevalence of use of TCAM.

Methods

MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL, PsycINFO and AMED were searched to identify relevant studies published since 2010. Articles/reports describing the prevalence of TCAM use in a national study among the general population were included. The quality of included studies was assessed using a risk of bias tool developed by Hoy et al. Relevant data were extracted and summarised.

Results

Forty studies from 14 countries, comprising 21 national surveys and one cross-national survey, were included. Studies explored the use of TCAM products (e.g. herbal medicines), TCAM practitioners/therapies, or both. Included studies used different TCAM definitions, prevalence time frames and data collection tools, methods and analyses, thereby limiting comparability across studies. The reported prevalence of use of TCAM (products and/or practitioners/therapies) over the previous 12 months was 24–71.3%.

Conclusion

The reported prevalence of use of TCAM (products and/or practitioners/therapies) is high, but may underestimate use. Published prevalence data varied considerably, at least in part because studies utilise different data collection tools, methods and operational definitions, limiting cross-study comparisons and study reproducibility. For best practice, comprehensive, detailed data on TCAM exposures are needed, and studies should report an operational definition (including the context of TCAM use, products/practices/therapies included and excluded), publish survey questions and describe the data-coding criteria and analysis approach used.

Plain Language Summary

Traditional, complementary and alternative medicine (TCAM) includes products (e.g. herbal medicines, dietary supplements) and therapies/practices (e.g. chiropractic, acupuncture), and is a popular healthcare choice for many people. This study systematically reviewed national surveys of TCAM use around the world. We identified studies carried out in 14 different countries and one continent (Europe) on the extent of use of TCAM in the general population. TCAM use was found to be substantial, ranging from 24 to 71.3% in different countries. National surveys use different methods and different survey questionnaires. Some studies did not publish the survey questionnaire that they used and/or did not describe the types of TCAM included in the study. This means that it is not possible to compare the results between countries or to do further data analysis. For example, the survey questions from different countries asked people if they had ‘used’ or ‘seen a practitioner’ for a specific therapy, such as homeopathy. These questions look similar, but could elicit different answers from people. This means that the answers to these questions cannot be pooled together or compared directly. Also, some studies collected information on use of a category of TCAM products, such as herbal medicines, but other studies collected information on use of specific herbal medicines, such as St John’s wort. New surveys of the extent of use of TCAM should provide full information on the types of TCAM products, practices and therapies included in the study and consider collecting comprehensive information on use of specific TCAM products, practices and therapies.

Key Points

| The prevalence of use of traditional, complementary and alternative medicine (TCAM) in the general population is substantial. |

| TCAM prevalence studies use different operational definitions, methods and data collection tools (including question types), which limits comparability across studies and further analyses. |

| For best practice, TCAM prevalence studies should provide an operational definition for TCAM and describe the range of TCAM practices/therapies/products included, collect comprehensive (specific) data on TCAM practices/therapies/products exposures and describe the data-coding criteria and processes used in the study. |

Introduction

The terms 'complementary medicine', 'alternative medicine' and 'complementary and alternative medicine' (CAM) refer to a broad set of health practices and products typically not part of the 'conventional medicine' system [1, 2]. The term 'traditional medicine' (TM) refers to ancient healthcare systems indigenous to different cultures developed before the presently known contemporary conventional medicine [2]. More recently, the term 'integrative medicine' (IM) has been introduced to describe the combined use of 'conventional' and traditional, complementary and alternative medicine (TCAM) approaches in a patient-focused manner to achieve positive health outcomes for individual patients [3]. In 2022, researchers established an operational definition for ‘complementary, alternative and integrative medicine’ (CAIM); the definition included 604 TCAM therapies, an update from the 259 that were listed on the Cochrane Complementary Medicine website [4]. The World Health Organization’s (WHO’s) global report on traditional and complementary medicine 2019 used the term ‘traditional and complementary medicine (T&CM)’ to ‘merge the terms traditional medicine and complementary medicine, encompassing products, practices and practitioners’ [2]. Globally, these terms (CAM, TM, IM and CAIM) are often used interchangeably and are evolving, and universal definitions do not exist despite multiple efforts to reach consensus [5, 6]; understandably so, because what is considered mainstream/non-mainstream healthcare differs across countries/regions, and may change over time.

TCAM is a popular healthcare choice among patients and consumers, in part due to widely held beliefs that TCAM products/preparations are composed of natural, safe ingredients, and that TCAM practices are holistic and without risk of harm [7, 8]. In some countries, such as China and South Korea, the use of TM is prominent due to its strong historical and cultural roots; in many other countries, use of TM is less prominent but very important culturally and socially nevertheless [9]. TCAM use is also widespread because of its availability and (relative) affordability and where people have limited access to conventional healthcare. In the United States (US), retrospective analysis data on costs and use of healthcare and health insurance coverage revealed that individuals without health insurance were 50% more likely than people with health insurance to seek TCAM provider care [10]. In some populations, TM is the only source of healthcare; the ratio of traditional healers to the African population is 1:500, whereas the ratio of medical doctors to the population is 1:40,000 [11]. Dissatisfaction with conventional medicine is also a driver for TCAM use [7, 12], and up to two-thirds of TCAM users do not disclose TCAM use to 'conventional' health practitioners [13]. This raises concerns, as there is evidence that use of some TCAM products and therapies is associated with adverse reactions [14, 15], including when, for example, TCAM products or preparations are used concurrently with conventional medicines [16, 17].

Nationally representative periodic surveys are useful in exploring trends in TCAM use and could provide estimates of exposures to TCAM products and therapies. The most recent and comprehensive systematic review on the prevalence of TCAM use across 15 countries, published in 2012, reported that the prevalence of use of any TCAM over the previous 12 months in the general population was up to 76% [18]. New nationally representative studies on the prevalence of TCAM use among the general population [19, 20], as well as among patients with a range of different medical conditions [21, 22], and in various healthcare settings [23–25], have now been published; it is, therefore, timely to examine new information on trends in TCAM use.

A long-standing problem [or challenge] with TCAM prevalence studies is differences in methods used internationally, which limits the comparability of findings across studies. Estimates of prevalence of use of TCAM vary depending on how TCAM is defined and how definitions are operationalised in different studies. For instance, it was found that the reported prevalence of TCAM use was inflated when studies included prayer as a TCAM approach in their operational definition [18].

Against this background, this systematic review aims to identify and examine recently published national studies globally on the prevalence of TCAM use in the general population and describe the research methods used in these studies to propose best practices for future studies exploring prevalence of use of TCAM. The specific review research questions are:

What operational definitions, data collection tools, and methods were used in national studies on TCAM prevalence of use published during 2010–2019?

What is the prevalence of TCAM use in the general populations reported in these studies?

Methods

Operational Definition

In this systematic review, the term TCAM was used and operationally defined as ‘encompass[es] all health systems, modalities, and practices not typically considered part of conventional western medicine that is used for health maintenance, disease prevention, and treatment’ [26]; this included:

- TCAM products/preparations

-

oComplementary medicines: Includes, but is not limited to, products or preparations described as natural health products, complementary/alternative medicines/remedies, dietary supplements, nutraceuticals and/or TMs (products or preparations used in TM systems, such as traditional Chinese medicine, Ayurvedic medicine)

-

o

- TCAM practices/therapies

-

oComplementary therapies/practices: Includes, but is not limited to, mind-body therapies (e.g. hypnotherapy, yoga), manipulative/body-based methods (e.g. osteopathy, chiropractic), and energy therapies (e.g. reiki, therapeutic touch)

-

oTraditional medicine practices, such as traditional Chinese medicine, Ayurvedic medicine, as well as other treatments, such as acupuncture and cupping.

-

o

Search Strategy

The following databases were searched to retrieve potentially relevant articles: MEDLINE, EMBASE, AMED, CINAHL and PsycINFO. The search terms employed were related to three concepts: 'traditional, complementary and alternative medicine', 'prevalence' and 'national' (see electronic supplementary material 1). In addition, government 'surveillance' data (national surveys/census) and reports on TCAM use in the US, Canada, the United Kingdom (UK), Australia and New Zealand were also searched. Reference lists of included articles were checked for additional relevant studies. The search was limited to English language articles/reports published from January 1, 2010 to October 7, 2019. All articles/reports were imported to a reference manager software (EndNote), where duplicates were removed and studification (grouping publications from the same study) was undertaken.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Articles/reports were included if they reported the prevalence of TCAM use in a national study among the general population. Prevalence could be reported based on any defined period (e.g. current use, lifetime use, use in previous 12 months). Studies/reports describing the use of single TCAM products/therapies (rather than overall TCAM use) and/or conducted in sub-populations (e.g. specific clinical conditions, demographic groups) were excluded.

Study Selection, Quality Assessment and Data Extraction

Articles were selected in two phases by two reviewers (ELL, NR) independently using EndNote reference manager; titles and abstracts were screened, then full texts for potentially relevant articles were retrieved and screened to identify studies meeting inclusion criteria. As one article may report findings across several 'waves' of a survey/study, or one wave of a survey may be reported by several articles, this systematic review reports each wave of a national survey (rather than the individual article) as a unit of analysis. Data relevant to the review research questions were extracted from included studies using a data extraction form developed by the research team, and study quality was assessed by two authors (ELL, NR) independently. Study quality was assessed using a risk of bias tool developed by Hoy et al., 2012 [27] specifically for prevalence studies. The tool comprises ten items assessing internal and external validity biases (low/high risk) and a summary item on the overall risk of bias (low/medium/high risk). The ten individual items are assessed as having a high risk of bias if the information reported in the text was inadequate or unclear. At all stages, any discrepancies were discussed and solved by consensus, or by referral to a third reviewer (JB). The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) checklist was used to guide reporting of this review [28].

Ethical Approval

Ethical approval was not sought, as this review involved completed studies only.

Results

Characteristics of Included Studies

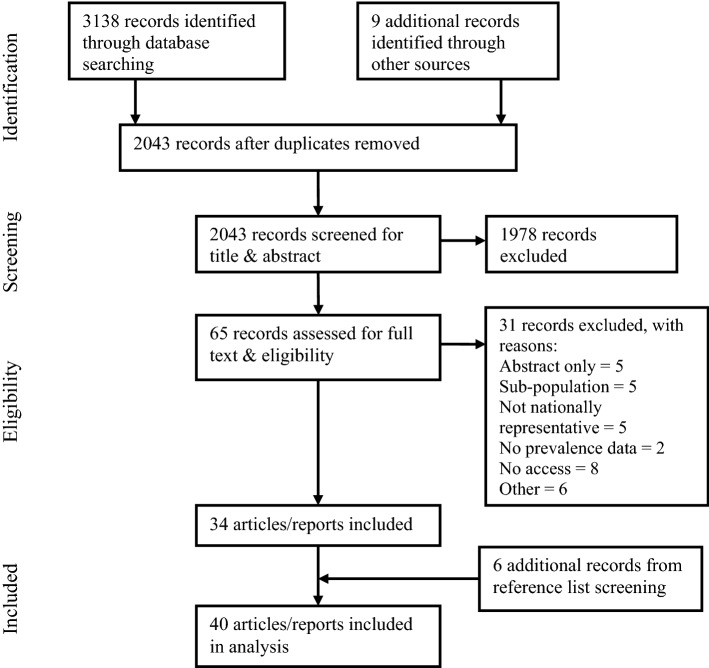

In total, 40 articles/reports (Fig. 1) across 14 countries met the inclusion criteria, representing 21 national surveys and one cross-national survey (21 countries from the European Social Survey [ESS]). The ESS was considered as one wave/study as only the overall (rather than individual country) prevalence of each TCAM practitioner consultation was reported. Collectively, 40 waves/studies were included for analysis in this systematic review (see electronic supplementary material 2). Of the 21 national surveys and one cross-national survey, eight explored the prevalence of use of TCAM products and TCAM practitioners [19, 29–37], eight explored the use of TCAM products only [38–52], and four explored consultations with TCAM practitioners only [53–56]. The older waves of the Australian National Health Survey [57] and US National Health and Interview Survey (NHIS) [58–65] explored use of TCAM practitioners and TCAM products, but recent waves of these surveys assessed use of TCAM products only [66] and TCAM practitioners only [67], respectively.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of literature search and study selection process. PRISMA preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analyses

Operational Definitions

An operational definition was not reported in most studies (57.5%); where reported, definitions used were not identical across studies. Both the Taiwanese and South Korean surveys broadly adopted the US National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM) (now the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health [NCCIH]) description that (T)CAM is ‘a group of diverse medical and healthcare systems, practices, and products that are not generally considered part of conventional medicine’ [3]. When scrutinised, the Taiwanese survey adopted additional criteria to specifically exclude use of TCAM where delivered/practised by conventional medical doctors [35]. The South Korean survey included some TCAM therapies specific to the country, such as 'spa for health reasons', 'hand acupuncture' and 'taping therapy', that were outside the NCCAM description/classification system [40].

Operational definitions differed across surveys and between waves/studies within the same national survey. In the US NHIS 2002, 2007 and 2012 surveys, the TCAM approaches explored varied across different survey waves. Use of traditional healers and 'movement therapies' was included in the 2007 wave, but not for 2002. In total, the use of 119 non-vitamin, non-mineral dietary supplements was queried in NHIS 2012 versus 44 in NHIS 2007. The NHIS 2002, but not 2007 and 2012, included herbal teas [58–65].

Data Analysis and Reporting

Comparing data for the prevalence of use of TCAM practitioners/therapies across studies is complex because the questions asked in each survey differed. For instance, some surveys asked participants if they have 'seen/talked to a chiropractor' [19, 29], while others explored whether participants 'are receiving chiropractic manipulation' [61, 63, 65]. For certain therapies, such as homeopathy and aromatherapy, some questions did not specify or further explore whether access was through practitioners or self-purchase of products without prior consultation with a health practitioner (Box 1) [34, 37].

|

How often have you used one of the following therapies in the last 12 months? • Acupuncture • Homeopathy • Herbal medicine • Shiatsu/foot reflexology • Autogenic training, hypnosis • Neural therapy • Traditional Chinese medicine • Bioresonance therapy • Indian medicine/Ayurveda • Osteopathy • Other therapies, e.g. kinesiology, Feldenkrais method etc. |

DURING THE PAST 12 MONTHS, did you see a practitioner for homeopathic treatment? |

Except for the US National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 1999–2012 [47–52], US NHIS 2002–2012 [58–65] and several other studies [39, 40, 46, 66], the prevalence of use of TCAM products was reported in terms of product categories (e.g. herbal medicines) only, rather than the actual/individual products at a genus (e.g. Hypericum), species (e.g. Hypericum perforatum L.), or common name level (e.g. St John's wort). In addition, the grouping of products, or product categories, was inconsistent across studies. For example, one study reported the prevalence of use of vitamins/minerals and 'herbal remedies' separately [43], whereas the Australian National Health Survey 2007–2008 reported the prevalence of use of vitamins, minerals and 'herbs' collectively [57]. Regarding multi-ingredient products (e.g. multivitamins, vitamin C + echinacea), it is unclear how products were coded, categorised and analysed in the studies. Thus, the reported prevalence for categories (e.g. 'herbal medicines') may vary depending on the coding criteria adopted by different studies. In the US NHANES, ‘multivitamins, multiminerals’ (MVMM) were defined as products 'containing at least three vitamins with or without minerals' [47–52]; one article defined MVMM as products containing ten or more vitamins/minerals and, consequently, reported a lower prevalence of use [47].

Prevalence Time Frames

Various prevalence time frames were operationalised: 14 surveys used ‘previous 12 months’ [19, 29, 33–37, 40, 44–46, 53–55, 57–65, 67], four used ‘previous 30 days/month/4 weeks’ [30–32, 39, 47–52, 58–65] and three used ‘lifetime’ [36, 43, 56]. The remaining surveys used other prevalence time frames (‘previous 2 weeks’ [66], ‘previous 24 hours’ [38], ‘at least 2 weeks on a continuous basis in the past year’ [41] and ‘for more than 2 weeks in the past year or more than once in the past month’ [42]). Two surveys used more than one prevalence time frame. The Health Survey for England [36] used both ‘lifetime’ and ‘previous 12 months’, and the US NHIS in 2007 [58–64] and 2012 [61, 63, 65] used ‘previous 12 months’ and ‘previous 30 days’. The Australian National Health Survey used ‘previous 12 months’ to assess the use of TCAM practitioners and products in 2007–2008 [57], and used ‘previous 2 weeks’ to assess the use of TCAM products only in 2014–2015 [66].

Data Collection Tools

In all included studies, a structured questionnaire was used to collect data on an individual's TCAM use. For 22 studies, the questionnaire used was published [32, 34, 36, 37, 43, 47–54, 56, 58–67]. Of the remaining studies, 14 described the questionnaire used [19, 29–31, 33, 35, 38–41, 44, 45, 55, 57]. Question types (e.g. open/closed questions), phrasing and extent of detail surrounding TCAM use varied across studies.

Survey questions on TCAM products use took several forms. Most studies required participants to state the names (not further defined) or 'brands' of the individual product(s) used [19, 29, 38, 39, 41, 47–52, 66]. The South Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey limited participants to specify up to a maximum of four products [41]. An Australian cross-sectional survey [19, 29] adapted the International Complementary and Alternative Medicine Questionnaire (I-CAM-Q), a tool that allowed respondents to list up to three products in pre-specified product categories (‘Herbs/Herbal Medicine’, ‘Vitamins/Minerals’, ‘Homeopathic remedies’ and ‘Other Supplements’ [68]). It is unclear whether the Australian study implemented these limits, as the adapted questionnaire used in the study was not published [19, 29].

The Australian National Nutrition and Physical Activity Survey asked participants to state the Australian Register of Therapeutic Goods (ARTG) identification number found on 'supplement' containers, which was then matched to the ARTG list of over 10,000 'dietary supplements'/complementary medicines that can lawfully be supplied in Australia [38]. Several studies instructed participants to select from a list of product categories (e.g. herbal remedies, vitamins/minerals) [43] or individual products (e.g. valerian, Ginkgo biloba, vitamin C) [46, 58–65] with/without an ‘other’ option provided for reporting products used but not captured by the list. Some studies utilised showcards (lists/examples of individual products) to aid participant understanding and response [40, 58–65]. One survey asked participants if they used 'traditional herbs and/or vitamins/supplements' as part of a broader question on their use of medicines in self-treatment; data on specific products used were not collected [32]. Other information was collected regarding participants' use of TCAM products, including use frequency [39, 43–52], dose per 'serving' [41], duration of use [47–52], manufacturer name [39, 47–52], estimated cost [19, 29, 44, 45, 58–65], whether a practitioner was consulted or use was self-selected [19, 29, 58–65], source of product (e.g. pharmacy) [43] and health reasons for use [43–45, 58–65].

Similarly, questions capturing TCAM practitioners/therapies accessed also varied. Most studies allowed participants to select from a list of practitioners and/or therapies, with an 'other' option to collect data on practitioners/therapies not listed [19, 29–31, 34, 36, 53, 54]; two studies did not provide this option [32, 37]. Two studies used showcards listing types of TCAM therapies [36, 37]. Several studies asked participants about their consultations with each practitioner type and/or use of therapies individually (instead of selecting from a list) [33, 58–65, 67]. Two studies used open questions, asking participants to state types of practitioners consulted [56] and therapies used, without mentioning any specific TCAM practitioners/therapies [35]. One survey asked participants about visits to traditional practitioners as part of a broader question on healthcare utilisation [32]. Other information collected regarding TCAM practitioners/therapies used included frequency of consultations with practitioners [53, 54, 58–65], reasons for use [30, 31, 33, 35, 56, 58–65], cost [32, 33, 58–65] and, for therapies used, whether a practitioner was consulted [36] and whether the therapy was self- or practitioner-administered [33].

Data Collection Methods and Survey Modes

In a majority of included studies, surveys were interviewer-administered [30–33, 35–42, 44, 45, 47–54, 57–67]. Eight studies utilised a self-administered survey [19, 29, 34, 43, 46, 55, 56], and of these, five used a paper-based survey [34, 55, 56], two studies were administered online [19, 29, 46] and one study did not report the survey mode [43]. For the two online-based surveys, market research companies were employed to recruit a convenience sample of participants from the companies' respective member databases [19, 29, 46].

Study Quality

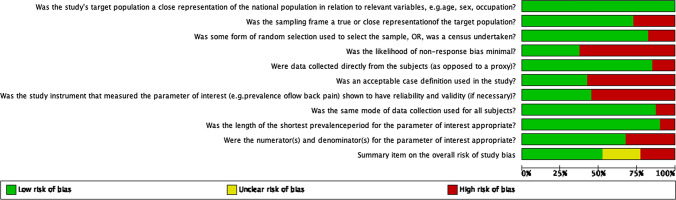

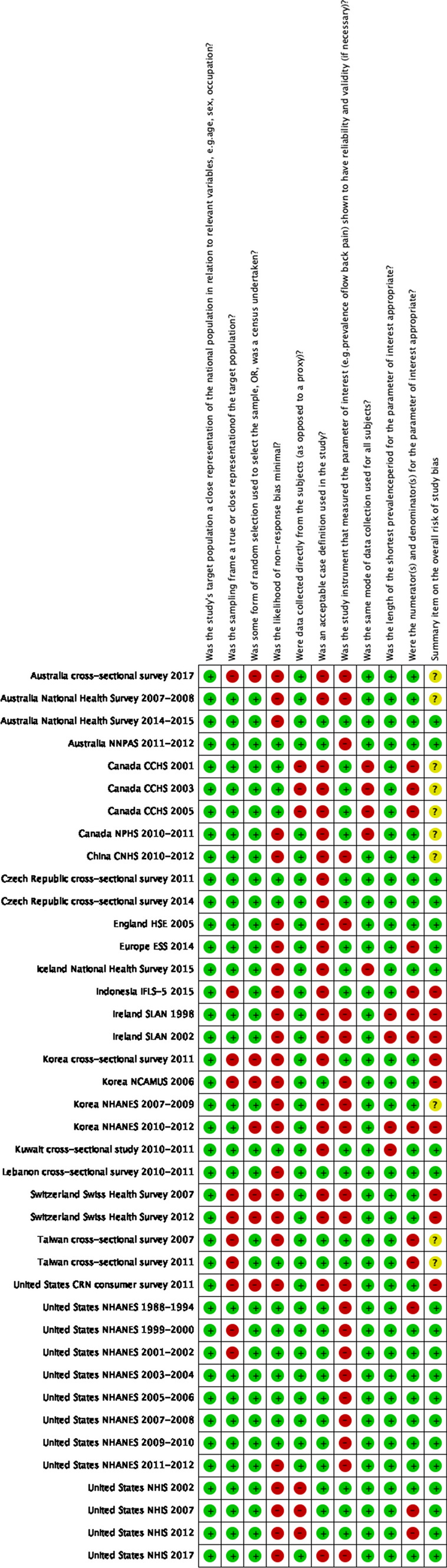

Although most studies (77.5%) were assessed as being at moderate or low risk of bias, none met all ten criteria for low risk of bias (Figs. 2, 3). A majority of studies was rated high risk for the likelihood of non-response bias (62.5%), acceptable case definition used (57.5%) and instrument reliability and validity (55%).

Figure 2.

Overview of risk of bias assessment of included studies

Figure 3.

Details for risk of bias assessment for included studies. NHANES National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, NHIS National Health and Interview Survey, SLAN Survey of Lifestyle, Attitudes and Nutrition

Prevalence of TCAM Use

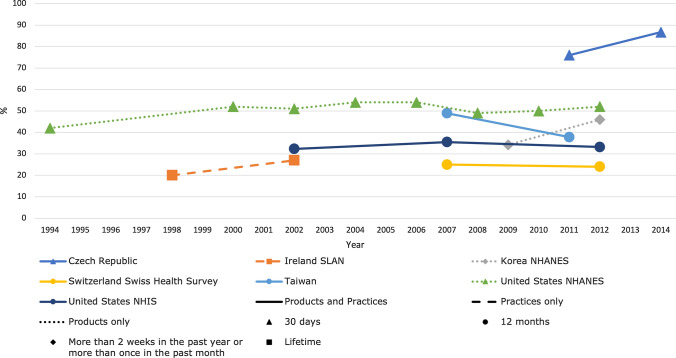

For national surveys with multiple waves/studies, the reported prevalence of TCAM use remained stable (the largest difference being 12%) over time in each respective country (Fig. 4). Prevalence of overall TCAM (products and practitioners) use over the previous 12 months ranged from 24% in the Swiss Health Survey 2012 [34] to 71.3% in a South Korean study in 2011 [33] (Table 1).

Figure 4.

Trends in prevalence of TCAM use by country for countries with at least two data collection waves from a nationally representative study. For data collected over several years (e.g. 2007–2009), the prevalence data are plotted at the end of the data collection period (e.g. 2009). Solid and perforated lines between consecutive points are for illustrative purposes only and are not intended to represent linearity. NHANES National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, NHIS National Health and Interview Survey, SLAN Survey of Lifestyle, Attitudes and Nutrition, TCAM traditional, complementary and alternative medicine

Table 1.

Prevalence of use of TCAM reported in included studies

| Country | Name of survey (if available) | Wave (year) of survey | Ref. | Sample age | Sample size (N) | TCAM terminology used | Time frame | Overall TCAM use (%)* | TCAM practitioner/therapy use only (%)* | TCAM products use (%)* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Australia | – | 2017 | [19, 29] | 18+ | 2019 | CM | Previous 12 months | Overall CM use = 63.1, *includes practitioner and treatment |

Consult at least one CM practitioner = 36 Massage therapist = 20.7 Chiropractor = 12.6 Yoga teacher = 8.9 Any CM practice (meditation, qi gong, etc) = 18.7 |

Using any CM product = 50.3 Vitamin/mineral supplements = 47.8 Aromatherapy oils = 11.1 Western or Chinese herbal medicines = 9.5 |

| Australia | National Health Survey | 2007–2008 | [57] | 18+ | 15,799 | CAM *(include practitioner and products) | Previous 12 months | Any CAM use = 38.4 (n = 6067) |

(% of n = 6067) CAM practitioner use (regardless of product use) = 37.9 |

(% of n = 6067) Vitamin, mineral, and herb use only = 62.1 |

| 2014–2015 | [66] | 14,560 | DSs *(report products only) | Previous 2 weeks | – | – |

At least one DS = 43.2 (% of n = 19,257—included participants < 18 years old) Multivitamin/mineral (without herbal extracts) = 17.5 Fish oil (without added nutrients) = 9.2 Vitamin D = 7.1 |

|||

| Australia | National Nutrition and Physical Activity Survey | 2011–2012 | [38] | 19+ | 4895 | DS | 24-h dietary recall | – | – |

Any supplement: Men = 34 Women = 47 Vitamins = 18.1 Herbal = 15.6 Multivitamin = 15.2 |

| Canada | Canadian Community Health Survey | 2001 | [53] | 12+ | Total 2001–2005: 400,055 | CAM, *practitioner only (no products) | Previous 12 months | – |

Consulted CAM practitioner = 12.4 (% of n = CAM users) Massage therapy = 62.9 Acupuncture = 18.3 Homeopathy = 18.2 |

– |

| 2003 | [53] | |||||||||

| 2005 | [53] | |||||||||

| Canada | National Population Health Survey | 2010–2011 | [54] | 20+ | 6562 | CAM | Previous 12 months | – |

Overall CAM use = 24.5 *Practitioner only Chiropractor = 13.4 Massage therapist = 7.6 Acupuncturist = 2.4 |

– |

| China | China Nutrition and Health Surveillance | 2010–2012 | [39] | 6+ | 74,501 | Nutrient supplement | Previous month | – | – | Nutritional supplement use = 0.71 |

| Czech Republic | - | 2011 | [30] | 15+ | 1797 | CAM | Past 30 days | Any CAM = 76 | Massage = 19.9 |

Vitamins and mineral = 54.6 Herbal teas = 47.8 |

| 2014 | [31] | 1805 | Any CAM = 86.7 | Massage = 26.1 |

Vitamins and mineral = 56.5 Herbal teas = 53.2 |

|||||

| England | Health Survey for England | 2005 | [36] | 16+ | 7630 | CAM | Lifetime and previous 12 months |

Lifetime: Overall CAM = 44.0 Previous 12 months: Overall CAM = 26.3 |

Lifetime: Massage = 13.1 Aromatherapy = 11.2 Acupuncture/acupressure = 11.2 Previous 12 months: Consulted a practitioner = 12.1 |

– |

| Europe | European Social Survey | 2014 | [37] | 15+ | NR | CAM | Previous 12 months | All countries: At least one CAM = 26 |

Massage therapy = 11.9 Homeopathy (unspecified if through practitioner) = 5.7 Osteopathy = 5.2 Herbal treatments (unspecified if through practitioner) = 4.6 |

– |

| Iceland | National Health Survey | 2015 | [55] | 18–75 | 1599 | CAM, *include practitioner only | Previous 12 months | – |

Any CAM treatment = 40.2 *Practitioner only Massage/medical massage = 27.1 Yoga/meditation = 19.3 Acupuncture = 8.5 |

– |

| Indonesia | Indonesia Family and Life Survey | 2015 | [32] | 15+ | 31,415 | Traditional practitioner, traditional medicine, CM | Previous month/4 weeks |

Traditional practitioner and/or traditional medicine use = 24.4% CM = 32.9 |

Traditional practitioner (shaman, wiseman, Chinese herbalist, masseur, acupuncturist, etc.) = 4.2 Self-treatment: Coining or massage = 26.5 |

Self-treatment: Consumed traditional herbs or traditional medicines as treatment = 19.7 Used vitamin/supplements = 9.7 |

| Ireland | Survey of Lifestyle Attitude and Nutrition | 1998 | [56] | 18+ | 6539 | CAM | Lifetime | – | Attended CAM practitioner = 20 | – |

| 2002 | [56] | 5992 | – |

Attended CAM practitioner = 27 Acupuncture = 7.8 Reflexology = 7 Homeopathy = 6.2 |

– | |||||

| South Korea | – | 2011 | [33] | 18+ | 1284 | CAM | Previous12 months | At least one CAM therapy = 71.3 |

Manipulative and body-based therapies = 23.6 Thermotherapy = 13.7 Massage = 6.8 Physical therapy with home medical devices = 5.8 Korean medicine practices by non-institutional practitioners = 12.5 Bloodletting therapy = 7.2 Acupuncture = 3.3 Cupping therapy = 3.0 Mind-body medicine = 4.8 Qigong training = 2.1 Forest therapy = 1.8 Spiritual treatment = 0.9 |

Natural products = 58.8 Dietary treatment = 34.5 Raw material = 32.9 Functional food = 31.6 |

| South Korea | National Complementary and Alternative Medicine Use Survey | 2006 | [40] | 30–69 | 3000 | DSs | Previous 12 months | – | – |

Any DS = 62.4 Ginseng = 23.1 Multivitamins = 14 Glucosamine = 9.6 |

| South Korea | National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey | 2007–2009 | [41] | 20+ | 16,031 | DSs | At least 2 weeks on a continuous basis in the past year | – | – | DSs = 34.2 |

| 2010–2012 | [42] | 15,789 | More than 2 weeks in the past year or more than once in the past month | – | – | DSs = 45.96 | ||||

| Kuwait | – | 2010–2011 | [43] | 20–80 | 1173 | Natural health products | Lifetime | – | – |

Natural health products = 71.4 Herbal remedies = 41.3 Vitamins/minerals = 33.3 Amino acids and essential fatty acids = 11.3 |

| Lebanon | – | 2010–2011 | [44, 45] | 18+ | 1500 | CAM products | Previous 12 months | – | – |

Any CAM product = 29.9 (n = 448) (% of n = 448) Folk herbs = 75 Natural health products = 31.7 Folk foods = 13.2 |

| Switzerland | Swiss Health Survey | 2007 | [34] | 15+ | 14,432 | CM | Previous12 months | Any = 25 |

Homeopathy = 8.2 Naturopathy = 7.7 Osteopathy = 6.8 Herbal medicine (unspecified if through practitioner) = 5.0 |

– |

| 2012 | [34] | 18,357 | Any = 24 |

Naturopathy = 7.7 Homeopathy = 6.4 Osteopathy = 5.4 Herbal medicine (unspecified if through practitioner) = 2.7 |

– | |||||

| Taiwan | – | 2007 | [35] | 18+ | 1260 | CAM | Previous 12 months | CAM therapies = 48.9 |

Chinese medicine herbs (unspecified if through practitioner) = 31.6 Tuina = 24.4 Health supplement products (unspecified if through practitioner) = 12.8 |

– |

| 2011 | [35] | 2266 | CAM therapies = 37.8 |

Chinese medicine herbs (unspecified if through practitioner) = 25.4 Health supplement products (unspecified if through practitioner) = 16 Tuina = 13.4 |

– | |||||

| United States | Council for Responsible Nutrition consumer survey | 2011 | [46] | 18+ | 2015 | Nutritional/DSs | Previous 12 months | – | – |

Supplement users = 69.0 Vitamin or mineral = 67 Specialty supplementsa = 35 Herbals or botanicals = 23 |

| United States | National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey | 1988–1994 | [48] | 20+ [47, 48] | NR | DS | Previous 30 days | – | – |

At least one DS = 42 [48] At least one multivitamins/multiminerals = 30 [48] |

| 1999–2000 | [47–49] | 20+ [47] | 4863 [47] | – | – |

Any supplement product = 52 [47] Any vitamin = 47 [47] Any mineral/element = 42 [47] |

||||

| 2001–2002 | [47–49] | 5396 [47] | – | – |

Any supplement product = 51 [47] Any vitamin = 47 [47] Any mineral/element = 43 [47] |

|||||

| 2003–2004 | [47–50] | 5028 [47] | – | – |

Any supplement product = 54 [47] Any vitamin = 49 [47] Any mineral/element = 45 [47] |

|||||

| 2005–2006 | [47–50] | 4972 [47] | – | – |

Any supplement product = 54 [47] Any vitamin = 49 [47] Any mineral/element = 46 [47] |

|||||

| 2007–2008 | [47, 49, 51, 52] | 5930 [47] | – | – |

Any supplement product = 49 [47] Any vitamin = 44 [47] Any mineral/element = 40 [47] |

|||||

| 2009–2010 | [47, 49, 52] | 6213 [47] | – | – |

Any supplement product = 50 [47] Any vitamin = 45 [47] Any mineral/element = 39 [47] |

|||||

| 2011–2012 | [47] | 5556 [47] | – | – |

Any supplement product = 52 [47] Any vitamin = 48 [47] Any mineral/element = 39 [47] |

|||||

| United States | National Health Interview Survey | 2002 | [58, 60, 61, 63] | 18+ |

30,472 [61] Total 2002–2012: 88,962 [63] |

CAM, CH | Previous12 months and 30 daysb |

Previous 12 months: Any CH approach = 32.3 [63] |

Previous 12 months: Deep-breathing exercises = 11.6 [63] Meditation = 7.6 [63] Chiropractic or osteopathic manipulation = 7.5 [63] |

Previous 12 months: Non-vitamin, non-mineral DSs = 18.9 [63] Herbal preparations and DS use = 18.9 [61] |

| 2007 | [58–64] |

22,657 [61] Total 2002–2012: 88,962 [63] |

Previous 12 months: Any CH approach = 35.5 [63] |

Previous 12 months: Deep-breathing exercises = 12.7 [63] Meditation = 9.4 [63] Chiropractic or osteopathic manipulation = 8.6 [63] |

Previous 12 months: Non-vitamin, non-mineral DS s = 17.7 [63] Herbal preparations and DS use = 17.9 [61] |

|||||

| 2012 | [61, 63, 65] |

34,525 [61] Total 2002–2012: 88,962 [63] |

Previous 12 months: Any CH approach = 33.2 [63] |

Previous 12 months: Deep-breathing exercises = 10.9 [63] Chiropractic or osteopathic manipulation = 8.4 [63] Meditation = 8.0 [63] |

Previous 12 months: Non-vitamin, non-mineral DSs = 17.7 [63] Herbal preparations and DS use = 17.9 [61] |

|||||

| 2017 | [67] | 26,742 | Included CAM practitioners and yoga only, *no CAM products | – |

Previous 12 months: Practiced yoga = 13.49 Used spiritual meditation = 11.41 Seen/talked to a chiropractor = 11 |

– |

In bullet points: Up to top 3–4 prevalence reported in respective study

CAM complementary and alternative medicine, CM complementary medicine, CH complementary health, DS dietary supplement, TCAM traditional, complementary and alternative medicine

*Terms and prevalence are extracted exactly as described in respective studies

aSpecialty supplements: 14 specialty supplements were listed, including omega-3 or fish oil, glucosamine and/or chondroitin, fibre, flaxseed oil, coenzyme Q10, probiotics, melatonin, superfruits, resveratrol, lutein, soy protein, SAM-e (S-adenosyl-l-methionine), plant sterols or stanols, and soy isoflavones

bIn 2007 and 2012, respondents were also asked if they had taken any herbal preparations and DSs during the past 30 days and then identify specific herbal preparations and DSs from a list

Discussion

This systematic review examined national studies published during 2010–2019 exploring the prevalence of TCAM use in the general population. The wide range of prevalence (24–71.3%) reported across countries is unsurprising; studies used different TCAM definitions, prevalence time frames, data collection tools and approaches to analysis. Hence, a pooled prevalence was not calculated, and direct comparisons of prevalence data across studies, over time and across locations, are not feasible. Nevertheless, the prevalence of any TCAM use is substantial (at least one-fifth of the general population) and is consistent over time. A lack of comprehensive data collection (e.g. context of TCAM use: access through practitioner or self-treatment) and inadequate reporting (e.g. operational definition, product categorisation/coding) further challenge accurate interpretation of study results. Compared with an earlier systematic review, trends were similar, with a reported prevalence of any TCAM use over 12 months ranging from 9.8 to 76% [18]. Seven of the 40 included studies in the present review were reported in a previous systematic review (conducted in 2011) [18], mainly arising as the present review also included studies published in 2010. Hence, this systematic review analysed an additional 33 prevalence studies, 20 of which were conducted from 2010 onwards. There were other fundamental differences between the previous [18] and the present systematic reviews. These include differences in the methods used. For example, our search strategy included the term ‘integrative medicine’ (not included in the previous systematic review’s search strategy), and the previous systematic review included sub-national studies, whereas the present systematic review focused on national studies only.

Standard definitions for individual terms (TCAM, CAM, TM and IM) and classification of practices/therapies and products may not be universally applied in studies or even relevant. Boundaries between TCAM products/preparations/practices and conventional medicines/practices evolve, are not always explicit and differ across countries/regions. In China, traditional Chinese medicine is central to the national healthcare system and is practised alongside ‘Western’ medicine at all healthcare service levels in the country [69]. In any country/region, over time, new products/practices are introduced, and what constitutes 'conventional' and 'complementary' medicine may change [26]. For example, in the USA, osteopathic medicine is recognised as a branch of the medical profession [70]. Ambiguities also arise where TM preparations/products (i.e. traditionally processed herbal extracts/decoctions) are used to treat ‘Western’ medicine diagnoses, such as hypertension and type 2 diabetes mellitus [71, 72], and at the 'food–medicine interface/border', where products such as herbal teas (e.g. green/black tea) and 'superfoods' (e.g. chia seeds, hemp seed) are marketed for and consumed in anticipation of health benefits [73, 74]. It is at researchers’ discretion whether such products are included/excluded in TCAM prevalence studies, and participants are relied upon to consider, recall and declare use of such products in relation to questions regarding TCAMs.

Conventional medicines and medical devices and statutorily regulated conventional medicine practitioners (e.g. doctors, pharmacists, nurses) typically are subject to comprehensive, robust regulations. Regulations can also apply to elements of TCAM, although regulatory frameworks for TCAM products and practitioners vary across countries. For products meeting regulatory definitions for TCAMs in specific countries, regulations may range from ‘light-touch’ to comprehensive pre-market evaluation of product quality, safety and efficacy (as for 'conventional' medicines) [75–77]. Similarly, regulation of TCAM practitioners is not present in every country or, if present, does not necessarily apply to all types of TCAM practitioners [2]. Even where specific types of TCAM practitioners are statutorily regulated, the extent of regulation (such as requirements regarding education and training, licensing and registration, and practice of TCAM) differs [78]. While a product/practitioner’s regulatory status should not be regarded as a benchmark to determine whether a product/practice is ‘complementary’ or ‘conventional’, being 'regulated' may elicit or strengthen the perception—at least among some stakeholders—of a genuine shift towards the TCAM product/practice becoming ‘conventionalised’. This has several implications, including product/practice acceptance by practitioners (whether from a conventional or TCAM background) and consumers; in some countries, regulation may be a pre-requisite for (but does not necessarily lead to) the product/practice being funded as part of a nation’s healthcare system. Certainly, for conventional health practitioners, once a TCAM product is regulated, even if through a ‘light-touch’ framework (typically based on products meeting accepted quality standards, containing only 'low-risk' ingredients and having evidence of effectiveness based on documented traditional use), this may provide some legitimacy and some assurance of product quality, safety and effectiveness [79].

In terms of TCAM practices/therapies, the concept of IM/health—not to be confused with 'integrated care'—is gaining traction [80], with some conventional practitioners recommending [81, 82] and administering [83] certain TCAM practices/therapies to their patients. Whether this should be considered ‘conventional’ or 'complementary medicine' can be debated; perhaps the more important consideration is the basis (e.g. evidence-based medicine) for conventional practitioners to employ these practices/therapies in their practice. This review found that standard definitions and TCAM classification systems do not fit the healthcare system and regulatory context for TCAM products and TCAM practitioners in different countries. Understandably, studies typically modify standard definitions and classification systems to suit their respective study contexts [35, 40]. These operational definitions for individual studies are essential and must be reported to facilitate interpretation and cross-study comparisons of results. Operational definitions should cover the context of TCAM use (e.g. self-selected products/therapies only), practices/therapies and/or products included and any specific exclusions (e.g. use of prayer, TCAM provided by conventional practitioners).

Participants' responses to questions on TCAM use depend on the type (open/closed) and the precise wording of questions asked. For example, questions asking whether a respondent had (1) ever used e.g. homeopathy, (2) seen a practitioner for e.g. homeopathy or (3) consulted e.g. a homeopath would capture different responses. The first question would capture use regardless of access type (self-selected/through a practitioner). The second question would only capture use when accessed through any practitioner; the third question specifies the particular type of practitioner. Also, these two questions imply a consultation with a practitioner but not the actual use of the TCAM product/therapy (e.g. homeopathic remedies).

Survey questions on TCAM products collect data at different levels of specificity; data are typically collected at the category (e.g. herbal products), active ingredient(s) (e.g. valerian) or proprietary/brand name (e.g. 'Nature Well’s Sleep Support' [fictitious product name]) level. Accuracy of data collected is dependent on respondents’ understanding and interpretation of these terms (‘category’, ‘active ingredient(s)’, ‘proprietary/brand name’) and ability to extract information (including identifying active ingredient[s]) from product labels. This process is further complicated for multi-ingredient products containing ingredients from different categories (e.g. turmeric [herbal ingredient] + glucosamine [non-herbal ingredient]) and/or unlabelled products, some of which may be supplied in crude form (e.g. dried plant materials). Relying on participants to categorise the products may lead to under- or over-reporting of use. Another factor to consider is the survey method. At any data collection level, if participants are tasked to provide information in a self-administered survey, there is a risk of errors and biases. Participants may categorise and consequently select the wrong category of product taken. The more specific level data would require participants to accurately recognise and transfer information, such as product (proprietary/brand) name and active ingredient(s) on the product label, into their survey response. An interviewer-administered survey may mitigate this, but this approach is resource intensive. In self-completed surveys, there may be response biases where participants use multiple products; participants might preferentially report use of single-ingredient products, products with clearer labelling and/or products they use most frequently or have used recently.

Collecting data at the proprietary/brand name or active ingredient(s) level instead of category level could be a better approach as researchers can then code/categorise the (ingredients of the) products in a standardised manner, thus increasing the accuracy and reliability of study results. For best practice, the coding criteria and processes, and the types of products included in each category, should be published to allow comparisons across studies. However, while there are internationally standardised coding frames for conventional medicines (such as WHODrug Global, an international reference for medicinal product information, maintained by the Uppsala Monitoring Centre) [84], at present, there is no comprehensive, standardised coding system for all herbal and non-herbal (e.g. ingredients from animal, mineral and bacterial sources) TCAMs. A herbal Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (H-ATC) Classification System is available and is an integrated part of WHODrug Global [84], but the H-ATC system has some limitations, including that it does not cover all herbal medicines. Development and use of a comprehensive international classification and coding framework and dictionary that provides a hierarchical structure for all TCAM products from category level to species (where relevant), animal/plant part(s) used (where relevant), active ingredient(s), type of extract, and linked to names of proprietary products (where relevant) is required. Universally coding TCAM exposures in this way would allow trends analysis and comparison across studies. Traditional Chinese medicine diagnoses components such as ‘Qi-deficiency’ and ‘damp heat’ are now incorporated as a Supplementary Chapter in the latest International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-11) [85]. Although the ICD-11 is a system of codes for medical diagnoses rather than treatments/products, this signifies a move towards a global standard coding system for some East Asian systems of TM, which could provide an essential tool for robust pharmacoepidemiological research.

Ideally, TCAM product exposure data would be collected at specific levels (e.g. tightly defined active ingredient[s] and proprietary product name), particularly where it is essential to accurately record participants’ exposures to specific substances/ingredients. However, collecting data at this level must be weighed against the need for researchers to categorise the products, which will increase the time and cost of the study. In the future, it may be possible to trace individual batches of TCAM products, for example, herbal ingredients from the grower through all elements of the supply chain to the specific batch of finished, marketed product using blockchain technology [86, 87]. Some progress in this area has been made, but multiple challenges remain, particularly with respect to multi-ingredient products (where it is complex to track each ingredient’s supply chain), high implementation costs and concerns related to privacy and intellectual property protection [86]. While recording exposures to this level of detail may appear superfluous with respect to prevalence of use, from a pharmacovigilance perspective, for TCAMs, such as herbal medicines, there are instances where traceability of product ingredients to their source could be desirable, even essential, due to the variability in the chemical profiles of herbal raw materials and finished products. A specific batch of raw material could be processed in different ways, sold through different importers and distributers and ultimately be included in multiple different products in different countries. If the original batch of material had variations in its chemical profile, including contaminants, it could be important to be able to trace exposures to material from that batch. This is illustrated in part by an example from the UK where specific batches of a registered herbal medicinal product containing St John's wort (Hypericum perforatum L.) were recalled due to presence of a toxic pyrrolizidine alkaloid (which does not occur naturally in this plant) at concentrations above acceptable limits [88].

In countries where TCAM product registration is required, collecting product registration numbers (such as the ARTG identifier number [89] or the Traditional Herbal Registration Number [UK]) [90] would reduce the need for participants to interpret and transfer information on product labels. This, however, does not apply to all TCAM products/preparations (including TMs) as many do not require registration. Collecting barcodes (including QR codes) is another option, as product information can then be traced to a certain extent. However, this would only apply to manufactured/finished products, where barcodes are mainly used for inventory management, and do not apply to traditional preparations. The information available from barcodes is also limited; the product ingredient list may not be available or sufficiently detailed/described. This is particularly an issue for herbal substances, which may be described only with common names (e.g. echinacea) without reference to the specific plant species and part(s) used. Botanical nomenclature is complex, lacks uniformity and, if used incorrectly, may lead to situations resulting in adverse health outcomes [91, 92]. One potential solution is to collect photographs of TCAM products/preparations that participants consume. Increasingly, online surveys are being utilised instead of paper-based surveys, and this provides an opportunity for more accurate data collection for TCAM use. Participants can provide photographs of product labels or capture information on ingredients in TMs, and researchers would then categorise the products accordingly as far as possible. The quality of information would be somewhat assured as participants are not relied upon to recognise and provide specific product information.

Internationally, substantial resource is expended in undertaking national surveys to determine and analyse trends in the prevalence of use of TCAM. As discussed, the prevalence of TCAM use is substantial, which raises questions about how this healthcare is funded. Funding models for TCAM need to be considered on a country-by-country and therapy-by-therapy basis. While some TCAM use is provided or funded through health systems in certain countries, such as China and South Korea [2], for many other therapies, evidence indicates that at least a substantial proportion of TCAM access is paid for out of pocket by consumers [93, 94]. In 2007, adults in the US spent $33.9 billion out of pocket on TCAM products and practices, and this accounted for 11% of all out-of-pocket healthcare expenditures in the country [94]. Such spending may indicate that consumers at least perceive they have unmet healthcare needs and see the value of TCAM in managing their health.

This review summarises the evidence of consistent and substantial use of TCAM at a population level. Furthermore, the review also identifies methodological limitations in data collection that are likely to under- rather than over-estimate prevalence of use. In addition to the high prevalence of TCAM use, many studies have reported a high prevalence of concurrent use of TCAM and conventional medicine(s) [95, 96]. These findings, taken together, have important implications for all health practitioners involved in providing patient care; the concurrent use of conventional medicine and TCAM raises safety concerns due to reports of important adverse reactions resulting from interactions between conventional and herbal medicines [97, 98]. Patient care risks also arise from the observation that TCAM is frequently self-prescribed by consumers [99], is used outside the conventional healthcare system and its use is often not disclosed to conventional health practitioners [13]. While mechanical injury and infection complications following the use of certain TCAM practices (e.g. acupuncture) have been observed and organ toxicity from the use of specific TCAM products has been seen [100–102], if the consumer does not disclose TCAM use, then there is a risk of misdiagnosis and/or inappropriate treatment. In essence then, achieving quality use of conventional medicine(s) (and TCAM approaches) and patient-centred care requires patients’ use of all healthcare approaches (including TCAM) to be considered and recorded. To optimise use of medicines and other healthcare approaches, healthcare practitioners and patients could be best served by having access to a comprehensive medication/treatment history of all medicines and other healthcare products and practices used by their patients and recorded in electronic medical records. An important additional benefit would be for the potential to use such real-world data in pharmacoepidemiological studies exploring the benefits and harms of TCAM approaches.

Prevalence data are affected by many factors, including differences in study design and methods, data collection tools and operational definitions used; these variations between studies are inevitable, partly due to geographical and cultural influences and the availability and position of TCAM in a country’s/region’s healthcare system. Studies need to be homogenous to allow appropriate cross-study comparisons and for pooled and trend analyses to be conducted. However, many of the current studies reported prevalence of TCAM use at a categorical level (e.g. 'herbal medicine', rather than a proprietary/brand or active ingredient level [e.g. ginkgo leaf extract]) and lack published descriptions (e.g., definition of and inclusion/exclusion of products in each category) to assess homogeneity adequately across studies. Evidently, there is a need for comprehensive, detailed data on TCAM exposures to be collected and reported in TCAM prevalence studies. Hence, in addition to reporting based on guidelines, such as the STROBE statement [103], the following best practices are recommended:

Operational definitions are essential, should be set a priori and reported for individual studies; the definition should describe the context of TCAM use (e.g. self-selected or prescribed products/therapies), practices/therapies and/or products included, and any specific exclusions (e.g., use of prayer, exercise, TCAM provided by conventional health practitioners).

The data collection tool (e.g., questionnaire) used in individual studies, including descriptions of any changes to the tool across waves of the same survey, should be published.

The data coding criteria and process and the types of products/therapies/practices included in each TCAM category should be reported. This includes describing how multi-ingredient products containing ingredients across different categories and unlabelled products are coded and analysed.

This systematic review identified and examined recently published national studies on the prevalence of TCAM use in the general population. To our knowledge, this is the first study that systematically reviewed the data collection tools and methods used in national prevalence surveys in the TCAM area. The validity of this review is also enhanced by using two independent reviewers for study screening and selection, data extraction and risk of bias assessment. Although a comprehensive search strategy was developed and used, some studies may have been missed, given the lack of uniformity in TCAM terminologies used in this area. Heterogeneity in research design and the methods of included studies limited the ability to analyse further and draw broader conclusions regarding the prevalence of TCAM use from this review.

Conclusion

The prevalence of use of TCAM, as determined by national studies, is substantial, and evidence indicates this is sustained over time. The studies reviewed here probably underestimate TCAM use due to methodological limitations, particularly those relating to the nuanced differences in questions relating to prevalence of use and differing levels of specificity in relation to exposures to specific TCAM products/practices/therapies. For best practice, studies need to provide an operational definition outlining the context of TCAM use and the range of practices/therapies and/or products included in the study, and state any specific exclusions. Survey questions should be published, and the coding criteria and processes should be described in detail to allow the reproducibility of study findings and cross-study comparisons.

Declarations

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions. No sources of funding were used to assist in the preparation of this review.

Conflict of interest

ELL has received a bursary from the University of Maryland School of Medicine/Cochrane Complementary Medicine Field for working on a Cochrane Systematic Review and is currently a doctoral candidate studying the prevalence of use of TCAM and conventional medicines in New Zealand; part of this work is funded by a Health Research Council grant (2020–2022) for which JB is the principal investigator. NR has no conflict of interest to declare. JH is a co-investigator for a Health Research Council grant exploring prevalence of use of TCAM and conventional medicines in New Zealand. JB has received fees, honoraria and travel expenses from the Pharmaceutical Society of New Zealand (PSNZ) for preparation and delivery of continuing education material on complementary medicines for pharmacists (2013, 2015); has provided consultancy to the Pharmacy Council of New Zealand on Code of Ethics statements on complementary medicines (unpaid) and competence standards (paid); was a member of the New Zealand Ministry of Health Natural Health Products (NHPs) Regulations Subcommittee on the Permitted Substances List (2016–2017); and led the Herbal and Traditional Medicines Special Interest Group (2017–2022) of the International Society of Pharmacovigilance. JB is a registered pharmacist (academic) in New Zealand and has a personal viewpoint that supports regulation for complementary medicines. JB is the principal investigator for a Health Research Council grant exploring prevalence of use of TCAM and conventional medicines in New Zealand. JB has undertaken other research exploring pharmacists’ views on and experiences with complementary medicines, supported by the Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain (RPSGB), New Zealand Pharmacy Education and Research Fund and University of Auckland. JB was the principal author of a reference textbook on complementary medicines and, at that time, received royalties with respect to sales of that publication from Pharmaceutical Press, the publishing arm of the RPSGB. JB is a co-author/co-editor of other books relevant to complementary medicines and receives royalties from Elsevier and SpringerNature/MacMillan Education. As a member of the School of Pharmacy staff, University of Auckland, JB has interactions with individuals in senior positions in the pharmacy profession. The School of Pharmacy has strategic relationships with several pharmacy organisations and receives support in various forms, such as sponsorship of student events, and guest lectures given by individuals from those organisations.

Availability of data and material

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Code availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Ethics approval

This is a systematic review. No ethical approval is required.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the idea for the article. ELL and JB developed the literature search strategy. ELL performed the literature search. ELL and NR performed the study screening, selection and data extraction. ELL drafted the article, and JB, NR and JH critically revised the work. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

E Lyn Lee, Email: elyn.lee@auckland.ac.nz.

Noni Richards, Email: noni@akohiringa.co.nz.

Jeff Harrison, Email: jeff.harrison@auckland.ac.nz.

Joanne Barnes, Email: j.barnes@auckland.ac.nz.

References

- 1.Ahuriri-Driscoll A, Boulton A, Stewart A, Potaka-Osborne G, Hudson M. Ma mahi, ka ora: by work, we prosper-traditional healers and workforce development. N Zeal Med J. 2015;128(1420):34–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.WHO global report on traditional and complementary medicine. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2019.

- 3.National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health. Complementary, alternative, or integrative health: what's in a name? 2018. https://nccih.nih.gov/health/integrative-health. Accessed 5 Jan 2020.

- 4.Ng JY, Dhawan T, Dogadova E, Taghi-Zada Z, Vacca A, Wieland LS, et al. Operational definition of complementary, alternative, and integrative medicine derived from a systematic search. BMC Complement Med Ther. 2022;22(1):104. doi: 10.1186/s12906-022-03556-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gaboury I, April KT, Verhoef M. A qualitative study on the term CAM: is there a need to reinvent the wheel? BMC Altern Med. 2012;12:131. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-12-131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holmberg C, Brinkhaus B, Witt C. Experts' opinions on terminology for complementary and integrative medicine - a qualitative study with leading experts. BMC Altern Med. 2012;12:218. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-12-218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reid R, Steel A, Wardle J, Trubody A, Adams J. Complementary medicine use by the Australian population: a critical mixed studies systematic review of utilisation, perceptions and factors associated with use. BMC Altern Med. 2016;16:176. doi: 10.1186/s12906-016-1143-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Welz AN, Emberger-Klein A, Menrad K. Why people use herbal medicine: insights from a focus-group study in Germany. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2018;18(1):92. doi: 10.1186/s12906-018-2160-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Health Organisation. The Regional Strategy for Traditional Medicine in the Western Pacific (2011–2020). Geneva: World Health Organization; 2012. https://iris.wpro.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665.1/5538/9789290615590_eng.pdf.

- 10.Lewing B, Sansgiry SS. PHP65—examining costs, utilization, and driving factors of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) services. Value Health. 2018;21:S97. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2018.04.657. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abdullahi AA. Trends and challenges of traditional medicine in Africa. Afr J Tradit Complement Altern Med. 2011;8(5 Suppl):115–123. doi: 10.4314/ajtcam.v8i5S.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sirois FM. Motivations for consulting complementary and alternative medicine practitioners: a comparison of consumers from 1997–8 and 2005. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2008;8:16. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-8-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Foley H, Steel A, Cramer H, Wardle J, Adams J. Disclosure of complementary medicine use to medical providers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):1573. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-38279-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ernst E. Adverse effects of spinal manipulation: a systematic review. J R Soc Med. 2007;100(7):330–338. doi: 10.1177/014107680710000716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.He W, Zhao X, Li Y, Xi Q, Guo Y. Adverse events following acupuncture: a systematic review of the Chinese literature for the years 1956–2010. J Altern Complement Med. 2012;18(10):892–901. doi: 10.1089/acm.2011.0825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vohra S, Cvijovic K, Boon H, Foster BC, Jaeger W, LeGatt D, et al. Study of natural health product adverse reactions (SONAR): active surveillance of adverse events following concurrent natural health product and prescription drug use in community pharmacies. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(9):e45196-e. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0045196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Awortwe C, Makiwane M, Reuter H, Muller C, Louw J, Rosenkranz B. Critical evaluation of causality assessment of herb-drug interactions in patients. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2018;84(4):679–693. doi: 10.1111/bcp.13490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harris PE, Cooper KL, Relton C, Thomas KJ. Prevalence of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) use by the general population: a systematic review and update. Int J Clin Pract. 2012;66(10):924–939. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2012.02945.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Steel A, McIntyre E, Harnett J, Foley H, Adams J, Sibbritt D, et al. Complementary medicine use in the Australian population: Results of a nationally-representative cross-sectional survey. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):17325. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-35508-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Esmail N. Complementary and alternative medicine: Use and public attitudes 1997, 2006 and 2016. Canada: Fraser Institute; 2017.

- 21.Jermini M, Dubois J, Rodondi PY, Zaman K, Buclin T, Csajka C, et al. Complementary medicine use during cancer treatment and potential herb-drug interactions from a cross-sectional study in an academic centre. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):5078. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-41532-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mbizo J, Okafor A, Sutton MA, Leyva B, Stone LM, Olaku O. Complementary and alternative medicine use among persons with multiple chronic conditions: results from the 2012 National Health Interview Survey. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2018;18(1):281. doi: 10.1186/s12906-018-2342-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.von Conrady DM, Bonney A. Patterns of complementary and alternative medicine use and health literacy in general practice patients in urban and regional Australia. Aust Fam Physician. 2017;46(5):316–320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ross EM, Darracq MA. Complementary and Alternative Medicine practices in military personnel and families presenting to a military emergency department. Mil Med. 2015;180(3):350–354. doi: 10.7205/MILMED-D-14-00304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jatau AI, Aung MM, Kamauzaman TH, Chedi BA, Sha'aban A, Rahman AF. Use and toxicity of complementary and alternative medicines among patients visiting emergency department: systematic review. J Intercult Ethnopharmacol. 2016;5(2):191–197. doi: 10.5455/jice.20160223105521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zollman C, Vickers A. What is complementary medicine? BMJ. 1999;319(7211):693–696. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7211.693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hoy D, Brooks P, Woolf A, Blyth F, March L, Bain C, et al. Assessing risk of bias in prevalence studies: modification of an existing tool and evidence of interrater agreement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2012;65(9):934–939. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Harnett JE, McIntyre E, Steel A, Foley H, Sibbritt D, Adams J. Use of complementary medicine products: a nationally representative cross-sectional survey of 2019 Australian adults. BMJ Open. 2019;9(7):e024198. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-024198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pokladnikova J, Selke-Krulichova I. Prevalence of complementary and alternative medicine use in the general population in the Czech Republic. Forsch Komplementarmed. 2016;23(1):22–28. doi: 10.1159/000443712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pokladnikova J, Selke-Krulichova I. The use of complementary and alternative medicine by the general population in the Czech Republic: a follow-up study. Complement Med Res. 2018;25(3):159–166. doi: 10.1159/000479229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pengpid S, Peltzer K. Utilization of traditional and complementary medicine in Indonesia: results of a national survey in 2014–15. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2018;33:156–163. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2018.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Baek SM, Choi SM, Seo HJ, Kim SG, Jung JH, Lee M, et al. Use of complementary and alternative medicine by self- or non-institutional therapists in South Korea: a community-based survey. Integr Med Res. 2013;2(1):25–31. doi: 10.1016/j.imr.2013.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Klein SD, Torchetti L, Frei-Erb M, Wolf U. Usage of complementary medicine in Switzerland: results of the Swiss Health Survey 2012 and development since 2007. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(10):e0141985. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0141985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chang MY, Liu CY, Chen HY. Changes in the use of complementary and alternative medicine in Taiwan: a comparison study of 2007 and 2011. Complement Ther Med. 2014;22(3):489–499. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2014.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hunt KJ, Coelho HF, Wider B, Perry R, Hung SK, Terry R, et al. Complementary and alternative medicine use in England: results from a national survey. Int J Clin Pract. 2010;64(11):1496–1502. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2010.02484.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kemppainen LM, Kemppainen TT, Reippainen JA, Salmenniemi ST, Vuolanto PH. Use of complementary and alternative medicine in Europe: health-related and sociodemographic determinants. Scand J Public Health. 2018;46(4):448–455. doi: 10.1177/1403494817733869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Burnett AJ, Livingstone KM, Woods JL, McNaughton SA. Dietary supplement use among Australian adults: findings from the 2011–2012 National Nutrition and Physical Activity Survey. Nutrients. 2017;9(11):14. doi: 10.3390/nu9111248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gong W, Liu A, Yao Y, Ma Y, Ding C, Song C, et al. Nutrient supplement use among the Chinese population: a cross-sectional study of the 2010–2012 China Nutrition and Health Surveillance. Nutrients. 2018;10(11):12. doi: 10.3390/nu10111733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ock SM, Hwang SS, Lee JS, Song CH, Ock CM. Dietary supplement use by South Korean adults: Data from the national complementary and alternative medicine use survey (NCAMUS) in 2006. Nutr Res Pract. 2010;4(1):69–74. doi: 10.4162/nrp.2010.4.1.69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kang M, Kim DW, Baek YJ, Moon SH, Jung HJ, Song YJ, et al. Dietary supplement use and its effect on nutrient intake in Korean adult population in the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey IV (2007–2009) data. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2014;68(7):804–810. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2014.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kim JW, Lee SH, Kim JE, Han KD, Kwack TE, Kim BS, et al. The association between taking dietary supplements and healthy habits among Korean adults: results from the fifth Korea National Health and Nutritional Examination Survey (2010–2012) Korean J Fam Med. 2016;37(3):182–187. doi: 10.4082/kjfm.2016.37.3.182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Awad A, Al-Shaye D. Public awareness, patterns of use and attitudes toward natural health products in Kuwait: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Altern Med. 2014;14:105. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-14-105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kharroubi S, Chehab RF, El-Baba C, Alameddine M, Naja F. Understanding CAM use in Lebanon: findings from a national survey. Evid Based Complement Altern Med. 2018;2018:4169159. doi: 10.1155/2018/4169159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Naja F, Alameddine M, Itani L, Shoaib H, Hariri D, Talhouk S. The use of complementary and alternative medicine among Lebanese adults: results from a national survey. Evid Based Complement Altern Med. 2015;2015:682397. doi: 10.1155/2015/682397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dickinson A, Blatman J, El-Dash N, Franco JC. Consumer usage and reasons for using dietary supplements: report of a series of surveys. J Am Coll Nutr. 2014;33(2):176–182. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2013.875423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kantor ED, Rehm CD, Du M, White E, Giovannucci EL. Trends in dietary supplement use among US adults from 1999–2012. JAMA. 2016;316(14):1464–1474. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.14403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gahche J, Bailey R, Burt V, Hughes J, Yetley E, Dwyer J, et al. Dietary supplement use among U.S. adults has increased since NHANES III (1988–1994). NCHS Data Brief. 2011;(61):1–8. [PubMed]

- 49.Chen F, Du M, Blumberg JB, Chui KKH, Ruan M, Rogers G, et al. Association among dietary supplement use, nutrient intake, and mortality among U.S. adults. Ann Intern Med. 2019;170(9):604–613. doi: 10.7326/M18-2478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bailey RL, Gahche JJ, Lentino CV, Dwyer JT, Engel JS, Thomas PR, et al. Dietary supplement use in the United States, 2003–2006. J Nutr. 2011;141(2):261–266. doi: 10.3945/jn.110.133025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kennedy ET, Luo H, Houser RF. Dietary supplement use pattern of U.S. adult population in the 2007–2008 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) Ecol food nutr. 2013;52(1):76–84. doi: 10.1080/03670244.2012.706000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bailey RL, Gahche JJ, Miller PE, Thomas PR, Dwyer JT. Why US adults use dietary supplements. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(5):355–361. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.2299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Metcalfe A, Williams J, McChesney J, Patten SB, Jette N. Use of complementary and alternative medicine by those with a chronic disease and the general population—results of a national population based survey. BMC Altern Med. 2010;10:58. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-10-58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Canizares M, Hogg-Johnson S, Gignac MAM, Glazier RH, Badley EM. Changes in the use practitioner-based complementary and alternative medicine over time in Canada: cohort and period effects. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(5):e0177307. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0177307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gunnarsdottir TJ, Orlygsdottir B, Vilhjalmsson R. The use of complementary and alternative medicine in Iceland: results from a national health survey. Scand J Public Health. 2019:1403494819863529. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 56.Fox P, Coughlan B, Butler M, Kelleher C. Complementary alternative medicine (CAM) use in Ireland: a secondary analysis of SLAN data. Complement Ther Med. 2010;18(2):95–103. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2010.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Spinks J, Hollingsworth B. Policy implications of complementary and alternative medicine use in Australia: data from the National Health Survey. J Altern Complement Med. 2012;18(4):371–378. doi: 10.1089/acm.2010.0817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Su D, Li L. Trends in the use of complementary and alternative medicine in the United States: 2002–2007. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2011;22(1):296–310. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2011.0002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Upchurch DM, Rainisch BK. A sociobehavioral model of use of complementary and alternative medicine providers, products, and practices: findings from the 2007 National Health Interview Survey. Evid Based Complement Altern Med. 2013;18(2):100–107. doi: 10.1177/2156587212463071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wu CH, Wang CC, Kennedy J. Changes in herb and dietary supplement use in the U.S. adult population: a comparison of the 2002 and 2007 National Health Interview Surveys. Clin Ther. 2011;33(11):1749–1758. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2011.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wu CH, Wang CC, Tsai MT, Huang WT, Kennedy J. Trend and pattern of herb and supplement use in the United States: results from the 2002, 2007, and 2012 national health interview surveys. Evid Based Complement Altern Med. 2014;2014:872320. doi: 10.1155/2014/872320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Upchurch DM, Rainisch BW. The importance of wellness among users of complementary and alternative medicine: findings from the 2007 National Health Interview Survey. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2015;15:362. doi: 10.1186/s12906-015-0886-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Clarke TC, Black LI, Stussman BJ, Barnes PM, Nahin RL. Trends in the use of complementary health approaches among adults: United States, 2002–2012. Natl Health Stat Report. 2015;79:1–16. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]