Abstract

Porphyromonas gingivalis is a keystone pathogen in periodontal disease. We herein report a dual-modal fluorescent and photoacoustic imaging probe for the detection of gingipain proteases secreted by P. gingivalis. Upon proteolytic cleavage by Arg-specific gingipain (RgpB), five-fold photoacoustic enhancement and >100-fold fluorescence activation was measured with detection limits of 1.1 nM RgpB and 5.0E4 CFU/mL bacteria in vitro. RgpB activity was imaged in porcine jaws with low-nanomolar sensitivity. Diagnostic efficacy was evaluated in gingival crevicular fluid samples from subjects with and without periodontal disease, wherein activation was correlated to qPCR-based detection of P. gingivalis (Pearson’s r = 0.71). Finally, photoacoustic imaging of RgpB-cleaved probe was achieved in murine brains ex vivo, with relevance and potential utility for disease models of general infection by P. gingivalis, motivated by the recent biological link between gingipain and Alzheimer’s disease.

Keywords: biosensors, fluorescent probes, gingipain, imaging agents, photoacoustic imaging

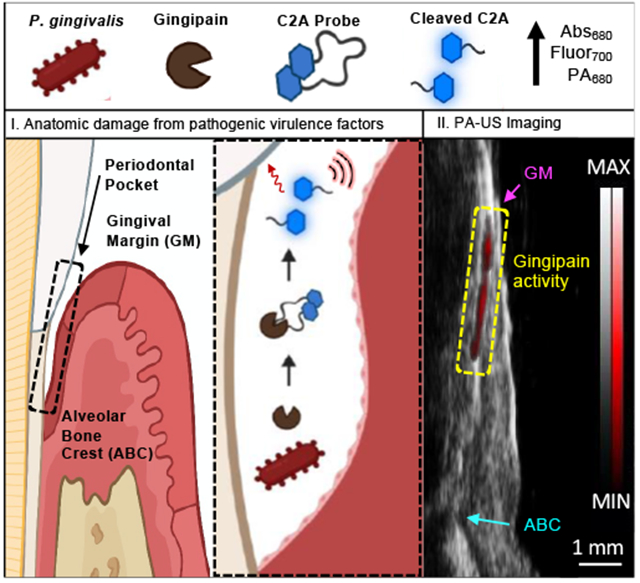

Graphical Abstract

Porphyromonas gingivalis is a keystone bacteria in periodontal disease, and the gingipain proteases from P. gingivalis are a biomarker of infection. Here, we report a small molecule contrast agent that produces fluorescence and photoacoustic signal in the presence of gingipains. We used this probe with animal models and further validated the probe with human samples of gingival crevicular fluid.

Introduction

Periodontitis is a chronic inflammatory disease that affects 46% of adults in the United States and generates billions of dollars per year in direct costs [1]. The pathogenesis of the disease remains an active research topic; however, it is principally associated with a dysbiotic oral microbiome and the accompanying immune response [2]. Periodontitis-associated bacteria reside in the subgingival crevice, and their presence in biofilms and gingival crevicular fluid contribute to degradation of host tissue and deepening of the periodontal pocket [3]. When untreated, periodontitis causes oral pain, tooth loosening, and tooth loss. Furthermore, the long-term loading of the immune system has been linked to increased risks for cardiovascular disease [4], pre-term birth [5], cancer [6], and even dementia [7].

Periodontal health is measured via periodontal probing and clinical examination with metrics that include the pocket depth, clinical attachment level, bleeding on probing, tooth mobility, and inflammation. Together, these metrics are used to form a diagnosis. In general, this established practice is functional and affordable, but pocket depth and clinical attachment level measurements suffer from relatively high inter-examiner error due to differences in probing force/angulation while also causing patient discomfort. Moreover, these techniques largely assess the effects of disease rather than using molecular diagnostics for precision health. Therefore, new techniques to detect disease at the point-of-care—particularly with utility for imaging and identification of disease at the molecular level—remain an unmet need in the field of oral health.

Many of the periodontal pathogens that have been linked to disease are anaerobic, such as Tannerella forsythia, Treponema denticola, and Porphyromonas gingivalis [8]. Among this “red complex”, P. gingivalis is the most well-studied and its presence in subgingival plaque has been correlated with disease progression in longitudinal human studies [9]. A 2018 meta-analysis of 42 studies (n = 5,884 subjects) reported the prevalence of P. gingivalis to be 78% in diseased subjects compared to 34% in healthy subjects. As a function of their anaerobic metabolism, these pathogens secrete protease virulence factors that degrade extracellular proteins and modulate the host immune response[10]. P. gingivalis, in particular, is known to secrete proteases called gingipains that exhibit trypsin-like activity [11].

Indeed, P. gingivalis and gingipain proteases have attracted attention both as diagnostic and therapeutic targets. A variety of naturally derived and synthetic gingipain inhibitors have been reported in the literature while demonstrating evidence for potential treatment of periodontal disease though clinical trials have been relatively rare [12]. Intriguingly, gingipain proteases (and P. gingivalis DNA) has been identified in the post-mortem brains of patients with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and are the target of an ongoing AD clinical trial for a small molecule gingipain inhibitor [13]. A parallel research effort is targeting P. gingivalis directly with an antibody therapy [14].

From a diagnostic perspective, advances in gingipain detection have included the development of substrates and paper-based assays for in situ analysis[15], a plasmonic nanosensor [16], and a gingipain-responsive/drug-loaded hydrogel [17]. The goal of this study was to develop an activatable probe for gingipains with utility for in vivo imaging—such work was motivated by its potential as a clinical tool for periodontal diagnosis and as a research tool for investigation of the role of gingipains in periodontitis and other diseases.

One potential diagnostic imaging modality is photoacoustic imaging—it is attractive because it augments the existing strengths of ultrasound, i.e., good tissue penetration, low cost, and real-time monitoring, with the contrast of optical methods. It can use both exogenous and endogenous contrast based on optical absorption. Many small molecule and nanoparticle contrast agents have been engineered for photoacoustic imaging and activatable probes for molecular imaging are particularly desirable [18]. Further, the dental applications of acoustic imaging (e.g., ultrasonography for anatomical damage) and nanoscale materials have been expanding[19] but they have not yet been combined for oral imaging. In previous work, we introduced a dye-peptide scaffold that exploits the intramolecular coupling of cyanine dyes to generate photoacoustic and fluorescent signal upon proteolysis by trypsin. Here, we expanded upon this exploratory work to create an activatable photoacoustic and fluorescent molecular imaging agent for gingipain proteases secreted by P. gingivalis with utility for diagnostic periodontal imaging and validation in gingival crevicular fluid samples from a clinical cohort.

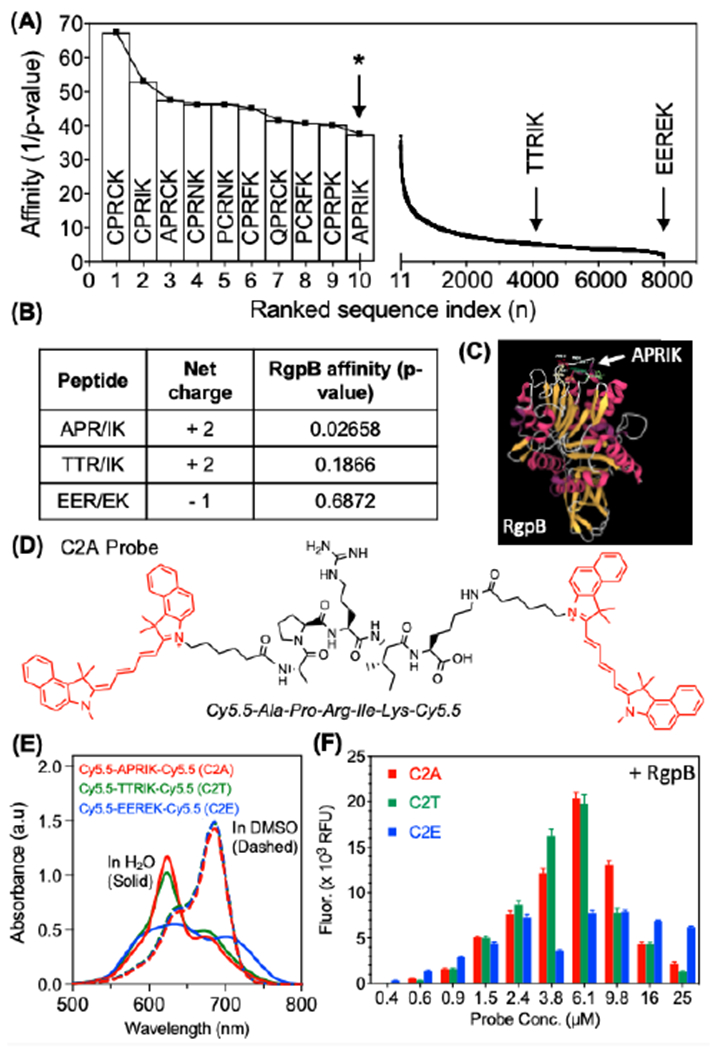

To select a gingipain-cleavable peptide substrate, we first applied a structural model of peptide-protein affinity to screen a series of pentapeptides for their affinity to the Arg-specific cysteine protease gingipain R (RgpB, PDB: 1CVR)[20]. The RgpB protease is composed of a 435-residue, single-chain polypeptide that forms a catalytic domain and an immunoglobulin-like domain [21]. The peptide candidates were generated with three constraints: a five-residue length, an arginine at the third residue (P1), and a lysine at the fifth residue (C-terminus, P2’), where substrate residues are indexed by convention as …P2-P1/P1’-P2’… and the slash denotes the cleavage site. The central arginine was necessary for cleavage by RgpB (known specificity) [22], and the C-terminal lysine was chosen for its reactive free amine. The peptide length was restricted to facilitate intramolecular interaction between N and C terminal dyes while reducing the likelihood of cleavage by off-target proteases. These conditions allowed us to generate 8,000 possible sequences that were screened for affinity to RgpB using an open-source structural model (PepSite 2.0) based upon a library of known peptide-protein complexes [20b]. The results were plotted as the inverse p-value to signify relative affinity (Fig. 1A) where the p-value represents the statistical significance for the overall score of a given binding site defined by Petsalaki et al. [23]. Of these peptides, the top result that did not contain a cysteine (excluded to reduce effects from dithiol coupling) was APRIK (p-value 0.0266) and was selected for probe synthesis. Additionally, the median result (TTRIK (p-value: 0.1866)) and last result (EEREK (p-value: 0.6872)) were synthesized and conjugated with dyes to serve as experimental controls for the model predictions (Fig. 1B). Visualization of the APRIK-RgpB interaction demonstrated that the peptide was predicted to bind the catalytic domain of RgpB (Fig. 1C, Fig. S1). The three candidate peptides were used to synthesize homodimer probes [Cy5.5]2[APRIK], [Cy5.5]2[TTRIK], and [Cy5.5]2[EEREK], referred throughout as C2A, C2T, and C2E, respectively (Fig. S2). RP-HPLC retention times for the conjugates decreased slightly from C2A (11.8 min) to C2T (11.7 min) to C2E (10.9 min), corresponding to the increasing hydrophilicity of the residues in each peptide (Fig. S3); the structures of the probes were confirmed with mass spectrometry and NMR (Fig. S3–S13).

Figure 1.

Structural selection and optical validation of photoacoustic/fluorescent peptides for RgpB. (A) Rankings of modeled peptide affinities for RgpB using an open-source structural model. All 8,000 five-residue peptides with a P1-arginine and C-terminal lysine were screened against RgpB (PDB: 1cvr). The affinities were plotted as the inverse p-values corresponding to the statistical significance of the peptide-protein interaction. APRIK was identified as the top candidate containing no cysteine residues (cysteine-containing sequences were excluded due to their potential for disulfide bridging). (B) APRIK, TTRIK (median affinity), and EEREK (lowest affinity) were selected for double conjugation with Cy5.5. (C) Structural model of top match (APRIK) with RgpB indicates preferential affinity for the catalytic domain. (D) Molecular structure of the dye-conjugated peptide, [Cy5.5]2[APRIK]. (E) Absorbance spectra of the conjugates in DMSO vs. H2O (1% DMSO) at equimolar concentrations (15 μM). (F) Fluorescence intensities for each conjugate after 1.5 h at a range of concentrations incubated with 25 nM RgpB.

The absorbance maxima of the conjugates in water were blue-shifted relative to their spectra in DMSO (Fig. 1E)—a solvatochromic effect indicative of aromatic dye stacking (specifically, H-aggregation)[24]. This blue shift confirmed intramolecular dye coupling, i.e., DMSO promotes intramolecular separation of the dyes by neutralizing their attractive π–π interactions, thus mimicking the effect of proteolytic cleavage of the peptide linker. We observed a broader and less intense peak in the 620-nm range for C2E relative to C2A/C2T. It is perhaps not surprising that variation in the sequence of the linking peptide modulated the spectral shift, as the exact shift is dependent on the spatial orientation of the dyes (side-by-side, head-to-tail, disordered, etc.). C2E may not form side-by-side intramolecular dimers as efficiently as C2A and C2T because its H-band (~624 nm) is lowest, and the overall spectrum is broadened (indicative of more scattering). Indeed, while each probe exhibited strong fluorescence quenching indicative of H-aggregates, C2E possessed the highest background fluorescence suggesting less efficient dimerization.

We measured the fluorescence from each probe at a range of concentrations upon incubation with constant RgpB and observed slightly stronger enhancement for C2A/C2T than C2E (Fig. 1F). Overall, the decreased activation at higher concentrations was caused by decreasing solubility of the probes, though if desired, this could be tuned by adjusting the percent DMSO as co-solvent (e.g., 1-3% v/v). Upon incubation of the probes with RgpB, the absorbance maxima of the dyes at 680 nm were recovered with increasing concentrations of protease (Fig. 2A, Fig. S14A, Fig. S15A). We observed reduction of the H-band and increased quenching in buffer conditions relative to water, which was attributed to nonspecific contact quenching induced by ionic charge screening (Fig. S16). Nevertheless, the fluorescence emission at 700 nm was also proportionally enhanced by RgpB cleavage (Fig. 2B, Fig. S14B, Fig. S15B). The fluorescence limits of detection were 1.1 nM, 0.6 nM, and 0.9 nM for C2A, C2T, and C2E, respectively (linearity 0 – 5 nM) (Fig. 2C, Fig. S14C, Fig. S15C) after 90 minutes. Like other proteolytic activity-based probes, the reaction rate is dependent on probe concentration, protease concentration, and buffer choice. In general, detectable signal was generated in minutes for nanomolar concentrations of RgpB and a typical reaction with 100-nM RgpB was complete in one hour (Fig. S17). The reaction rates were reduced in PBS and cell media (DMEM) relative to Tris buffer but still functional; in contrast, FBS posed a limitation as background activation was too high to detect RgpB cleavage (Fig. S18A). The probe could also tolerate pre-incubation in PBS and DMEM (2 h), but this slowed the subsequent reaction (Fig. S18B). Nevertheless, conditions were suitable for the intended application in gingival crevicular fluid (GCF).

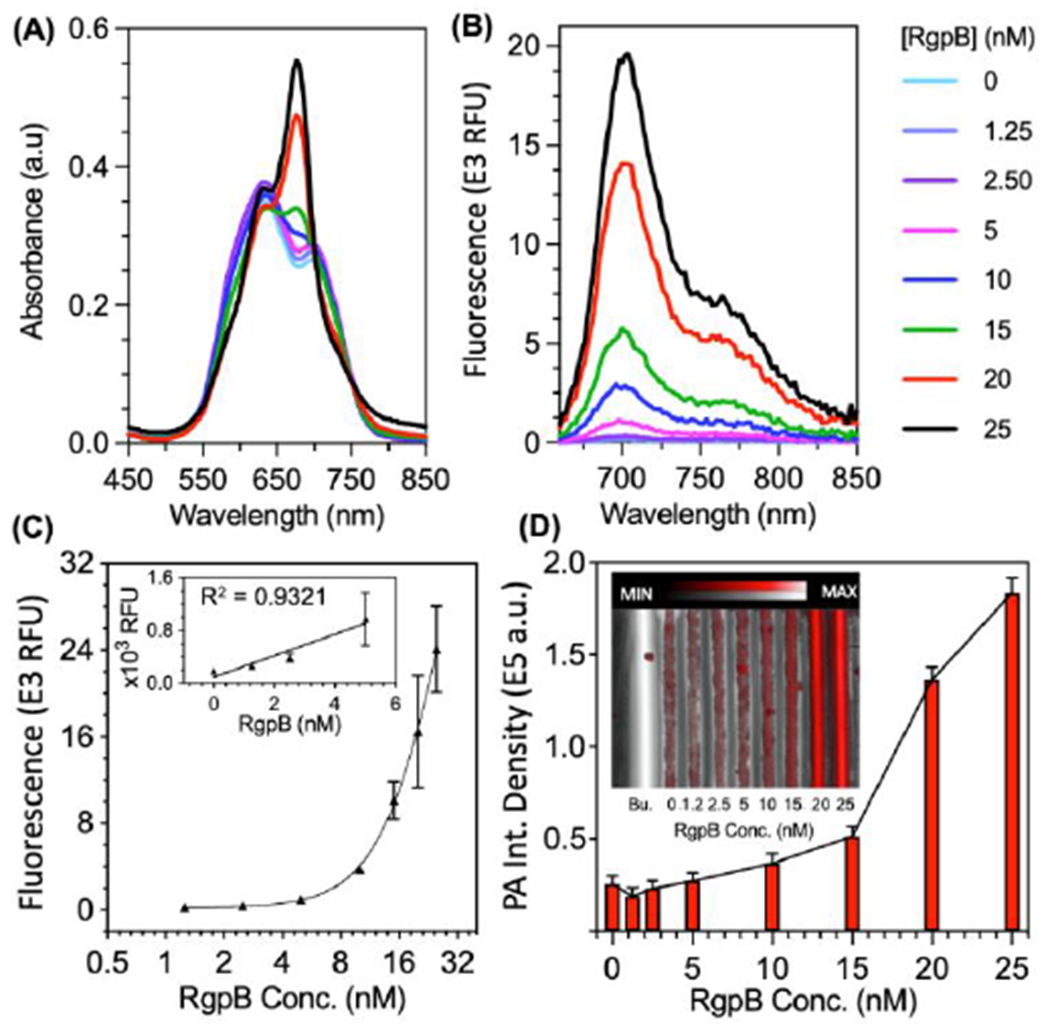

Figure 2.

Optical and photoacoustic limits of detection for C2A with recombinant gingipain (RgpB). (A) Absorbance spectra of C2A incubated with 0 – 25 nM RgpB after 90 minutes. (B) Fluorescence spectra (ex: 600 nm, em: 700 nm) of the samples after 90 minutes. (C) Fluorescence limit of detection for RgpB via fluorescence area scan (ex: 625, em: 700 nm, LOD = 1.1 nM, linear range: 0 – 5 nM, R2 = 0.93, n = 2, error = SEM). (D) Photoacoustic-ultrasound image with quantitated intensities for RgpB from 0 – 25 nM (ex: 680 nm, LOD = 15 nM, inset = raw photoacoustic ultrasound image, Bu. = buffer).

Importantly, the photoacoustic intensities of the cleaved C2A and C2T probes (excited at 680 nm) were proportional to their absorption, and the photoacoustic limit of detection was 10 nM RgpB for C2A (Fig. 2D) and 7.2 nM for C2T (Fig. S14D). Interestingly, C2E did not have photoacoustic sensitivity to RgpB at the tested concentrations even though it exhibited similar absorbance/fluorescence activation to C2A and C2T (Fig. S15). One explanation for this variation is differences between the solubilities of the probes, i.e., uncleaved C2E has less propensity to self-associate over time than C2A and C2T, leading to more absorbing dye moieties in solution that contribute to photoacoustic background. Nevertheless, while C2A and C2T were suitable for fluorescence and photoacoustic detection, we selected C2A for further experiments due to its higher predicted affinity for RgpB and higher signal to background ratio at concentrations > 6 μM.

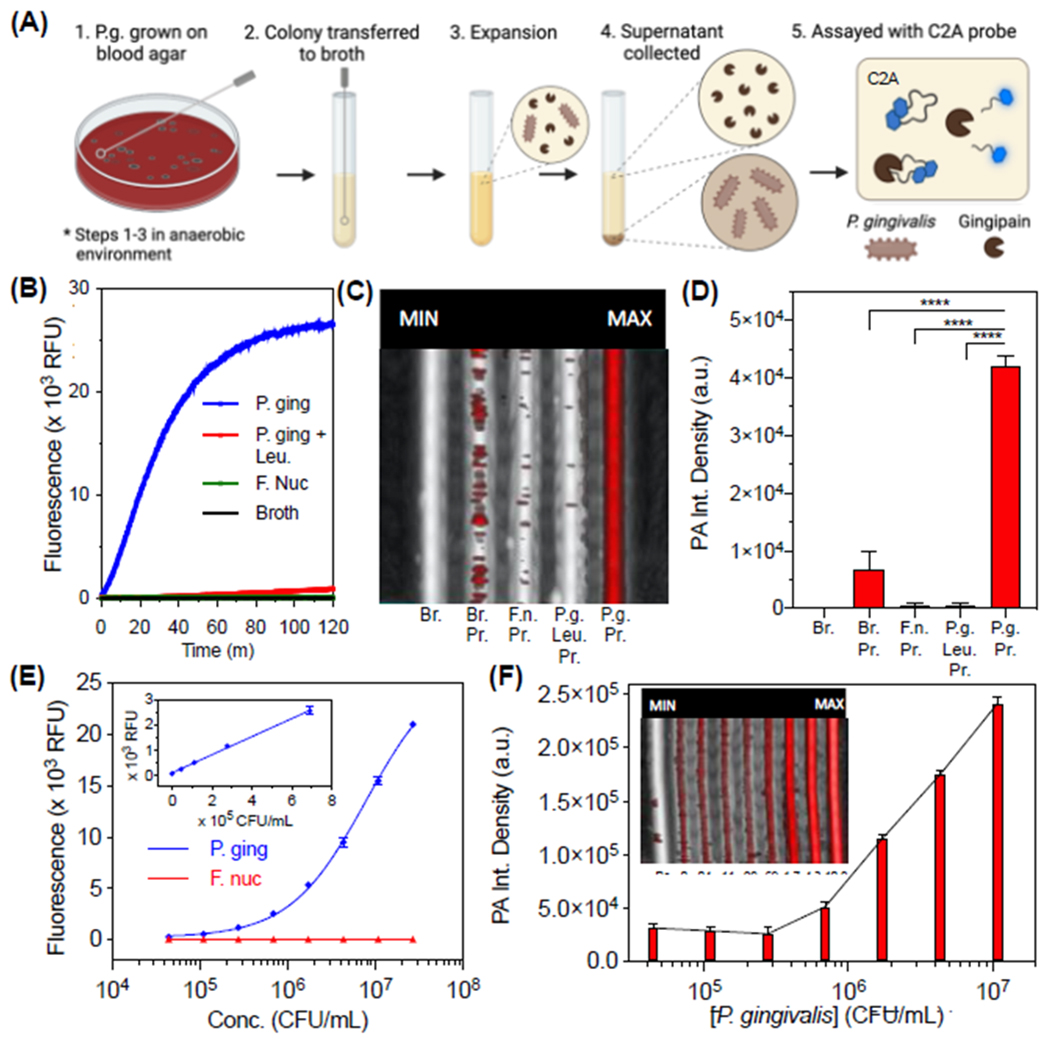

To further verify the probe’s sensitivity and selectivity for gingipains associated with P. gingivalis, we grew and isolated bacterial supernatants from both P. gingivalis and another oral anaerobe, F. nucleatum (Fig. 3A). F. nucleatum is a good negative control because it is also commonly identified in the gingival sulcus but is a saccharolytic and commensal bacterium known to not secrete gingipains [25]. These anaerobes were first grown on blood agar and enumerated from liquid suspensions via optical density after development of standard curves (Fig. S19–20). The presence of Arg-specific gingipain in the P. gingivalis cultures was confirmed with a commercially available enzyme-linked immunoassay (ELISA) kit (Fig. S21); in addition, activity was measured by incubation with a commercially available fluorescent substrate, Boc-Phe-Ser-Arg-AMC, as previously described [26] (Fig. S22). Then, upon incubation of the C2A probe with P. gingivalis supernatant, we directly observed cleavage of intact C2A (TR = 21.2 min) into Cy5.5-APR (TR = 17.2 min, [M+2H]2+ = 412.91 m/z) and IK-Cy5.5 (TR = 18.2 min, [M+2H]2+ = 454.93 m/z) fragments with HPLC and ESI-MS (Fig. S23), thus demonstrating the expected activity of Arg-gingipain in the bacterial supernatant and intended cleavage of C2A. Indeed, the probe activated fluorescence 135-fold over the course of 2 hours, corresponding to enhanced emission at 700 nm and absorbance at 680 nm (Fig. 3B, Fig. S24); this activation was reduced by 97% upon coincubation with leupeptin—a known gingipain inhibitor[27] (Fig. 3B). The fluorescence was not activated by F. nucleatum. As with fluorescence, we observed an increasing trend for the photoacoustic intensities of the samples excited at 680 nm, thus demonstrating selective photoacoustic imaging of gingipains from P. gingivalis (Fig. 3C–D). The limits of detection for the bacteria were tested via serial dilution of the supernatants in broth and determined to be 4.4E4 CFU/mL via fluorescence and 4.1E5 CFU/mL via photoacoustics (Fig. 3E–F, Fig. S25).

Figure 3.

Optical and photoacoustic properties of C2A with bacterial supernatants from cultured P. gingivalis. (A) Schematic of workflow for bacterial growth and assay. The same steps were performed for P. gingivalis and F. nucleatum. (B) Kinetics of C2A (10 µM) fluorescence activation with P. gingivalis supernatant, P. gingivalis supernatant with inhibitor (50 µM leupeptin), F. nucleatum supernatant, and culture broth alone (tryptic soy broth). Supernatants were assayed at 37 °C after 50% (v/v) dilution in buffer (final conditions: 2.5E7 CFU/mL bacteria, 20 mM Tris, 1 mM DTT, 2% DMSO, pH 7.3) (C) Photoacoustic-ultrasound MIP image of the samples with 680-nm pulsed excitation. Br = Broth, Pr = Probe, F. n. = F. nucleatum, P. g. = P. gingivalis, Leu = Leupeptin. (D) Quantitation of Panel D via integrated pixel density. Error bars = SD, asterisks denote significant difference (unpaired two-tailed t-test, p-value < 0.001). (E) Fluorescence limit of detection for P. gingivalis supernatants (LOD = 4.4E4 CFU/mL, linear range: 0 – 6.9E5 CFU/mL, R2 = 0.99). (F) PA image and quantitation of the same samples (ex: 680 nm) via integrated density (LOD = 4.1E5 CFU/mL, linear range: 0 – 4.3E6 CFU/mL, R2 = 0.94).

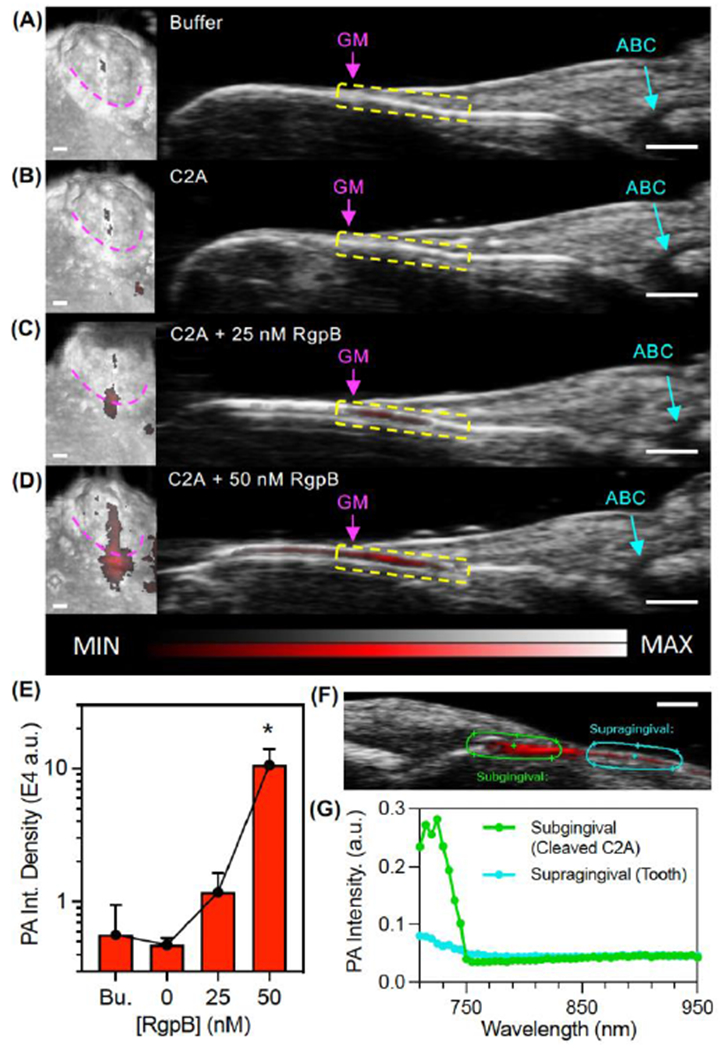

To date, reported strategies for measurement of gingipain activity have used in vitro detection methods, including a nanobody immunoassay[15b], an electrochemical biosensor[28], fluorogenic dipeptides[15a], peptide-functionalized magnetic nanobeads[29], and refractometry of protein-functionalized gold nanoparticles[16]. These have reported detection limits of 7.81E6 CFU/mL bacteria, 5E5 CFU/mL bacteria, 1E5 CFU/mL bacteria, 49 CFU/mL bacteria, and 4.3 nM Kgp (CFU/mL not reported), respectively. While the C2A probe has comparable sensitivity to these in vitro sensors (fluorescence LOD: 4.4E4 CFU/mL and 1.1 nM RgpB, photoacoustic LOD: 4.1E5 CFU/mL and 15 nM RgpB), it is the first reported gingipain probe suitable for photoacoustic imaging while also achieving a dual-modal fluorescence readout, with applicability for in vivo oral photoacoustic imaging, a technique that is gaining preclinical traction [30]. The added value of imaging is the monitoring of disease progression or response to therapy with the spatial integration of anatomic markers of disease. Indeed, to characterize the imaging performance of the C2A probe in relevant oral anatomy, it was used to resolve the periodontal pocket/gingival sulcus of intact porcine jaws with photoacoustic-ultrasound imaging (see Fig. S26 for transducer position). Here, buffer, C2A, and C2A + RgpB (25 and 50 nM), were irrigated sequentially into the gingival sulcus of the second molar of a porcine mandible (n = 3). 3D photoacoustic-ultrasonographs of the tooth/gingiva were generated (Fig. 4A, left) and anatomical markers were readily resolved in the midsagittal cross sections (Fig. 4A, right), including the gingival margin (GM, pink) and alveolar bone crest (ABC, teal). The uncleaved C2A probe did not possess significantly more photoacoustic signal (red) than buffer alone (Fig. 4B). However, C2A activated with 25-50 nM RgpB generated clear and increasing subgingival photoacoustic signal (Fig. 4C–E, yellow boxes), representing the subgingival distribution of RgpB-cleaved probe. In addition, spectral imaging could distinguish the imaging signal from cleaved C2A (< 750 nm) from the relatively flat spectra from supragingival signal caused by tooth staining (Fig. 4F–G).

Figure 4.

Photoacoustic-ultrasound imaging of RgpB-activated C2A probe in the gingival sulci of porcine jaws. (A) Left: 3D rendering of a mandibular second molar with PA signal (red) overlay on the US image (grayscale) following administration of Tris buffer at the gingival margin (pink). Right: cross-sectional image of the midsagittal plane of the tooth with the gingival margin (GM), alveolar bone crest (ABC), and gingival sulcus (yellow) labeled. (B-D) Images of the same site following administration of (B) C2A alone, (C) C2A + 25 nM RgpB, and (D) C2A + 50 nM RgpB. The sulcus was irrigated with water between imaging events. (E) Quantitation of the PA signal via integrated density for the maximum intensity projection of each PA image (n = 3 mandibles). (F) PA-US spectral image of subgingival signal corresponding to injected C2A (green ROI) and supragingival signal corresponding to background from the tooth surface (teal). (G) PA spectra of the regions in Panel F. Scale bars = 1 mm.

We performed a similar experiment in the swine mandible using fluorescence imaging to resolve the activated probe (Fig. S27). This shows the potential for alternative use in handheld intraoral fluorescence imaging which is gaining traction in image-guided oral procedures using indocyanine green (ICG)[31]. Notably, the C2A probe utilizes Cy5.5 which is a structural analog of ICG. Overall, these experiments demonstrate the ability to image the spatial distribution of subgingival gingipain activity in relation to key landmarks of oral anatomy while achieving low nanomolar sensitivity.

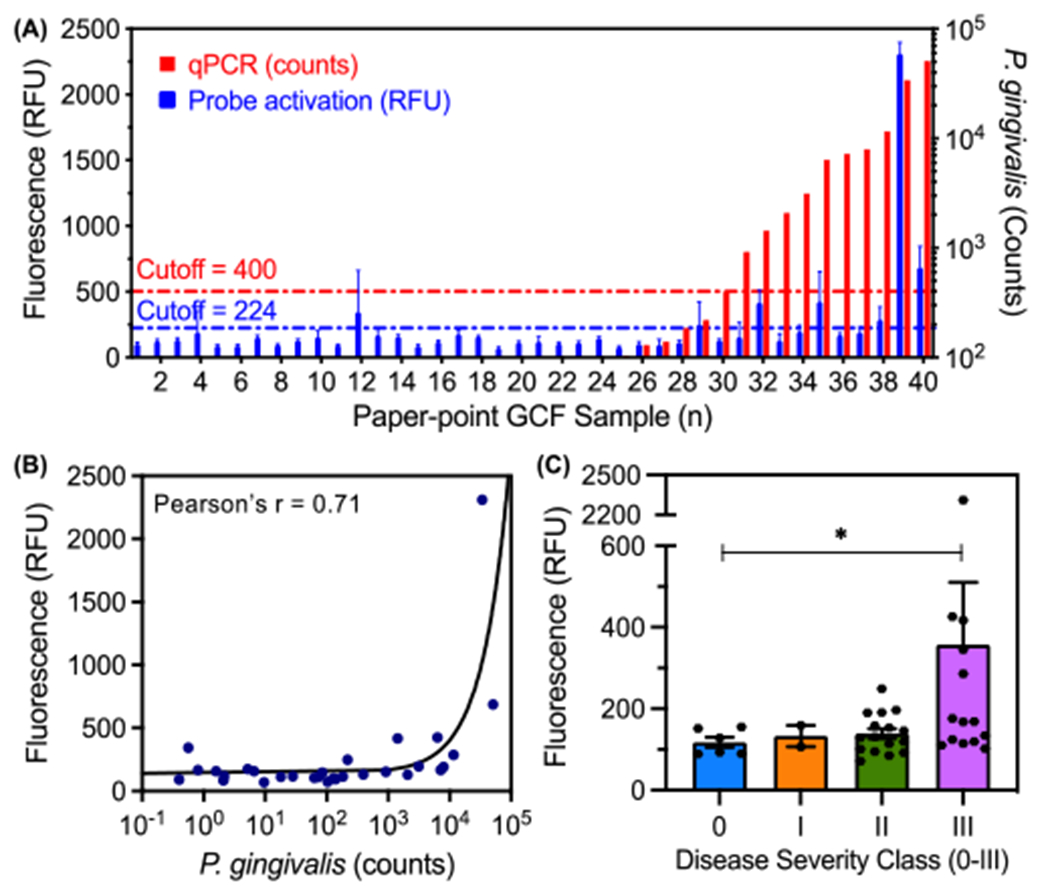

In a study by Guentsch et al., ELISA was used to identify micromolar concentrations of gingipain in gingival crevicular fluid (GCF) collected with paper point sampling from patients with periodontal disease [32]. This is well above the low nanomolar detection limits of C2A for RgpB: Therefore, to evaluate the diagnostic efficacy of the C2A probe in clinically relevant samples, we collected GCF from 40 tooth sites in a set of 20 subjects, comprising both healthy patients and individuals with symptoms of periodontal disease sampled at a dental clinic. The GCF samples were assayed with both qPCR and C2A via fluorescence to measure the number of P. gingivalis cells and proteolytic gingipain activity, respectively. Of these, 25% (10/40) contained P. gingivalis via qPCR and these were considered positives (Fig. 5A). Gingipain activity via C2A fluorescence was correlated with the PCR results (Pearson’s r = 0.71, Fig. 5B), albeit with lower sensitivity: Fluorescence activation was observed in 5/10 of the positives and 2/30 of the negatives, corresponding to a detection rate of 50% and a false positive rate of 6.67% (Fig. 5A). However, the higher sensitivity of qPCR was expected given its inherent signal amplification mechanism. And while it has value as a true independent measurement, qPCR reflects the amount of live (and metabolically active), live but senile, and dead cells. From these, only the metabolically active cells secrete gingipains, so is not a direct measurement of the protease. The activity data was also analyzed with respect to disease severity for each tooth site (Fig. 5C). Interestingly, gingipain activity was primarily observed in the GCF from Class III sites (with the greatest total facial CAL). Though half of these sites did not exhibit gingipain activity, these results support the hypothesis that local gingipain activity may contribute to more severe periodontal damage. Importantly, the significance between class II and class II in Fig. 5C is primarily driven by a few very high samples while the others are on par with class II.

Figure. 5.

Comparison between qPCR for P. gingivalis and fluorescence of C2A probe in GCF samples from a set of 20 subjects (n = 40 tooth sites). (A) Number of P. gingivalis cells (red) and probe activation (blue, gingipain activity) for each GCF sample (error bars = SD of fluorescence area scans, n = 13 points per well). (B) Correlation between number of P. gingivalis cells and probe activation (Pearson’s r = 0.71, two-tailed, p < 0.0001). (C) Probe activation for individual tooth sites from human subjects as a function of clinically diagnosed periodontal disease severity (Welch’s one-tailed t-test, 90% confidence: p-value = 0.07 < 0.10, error bars = SEM).

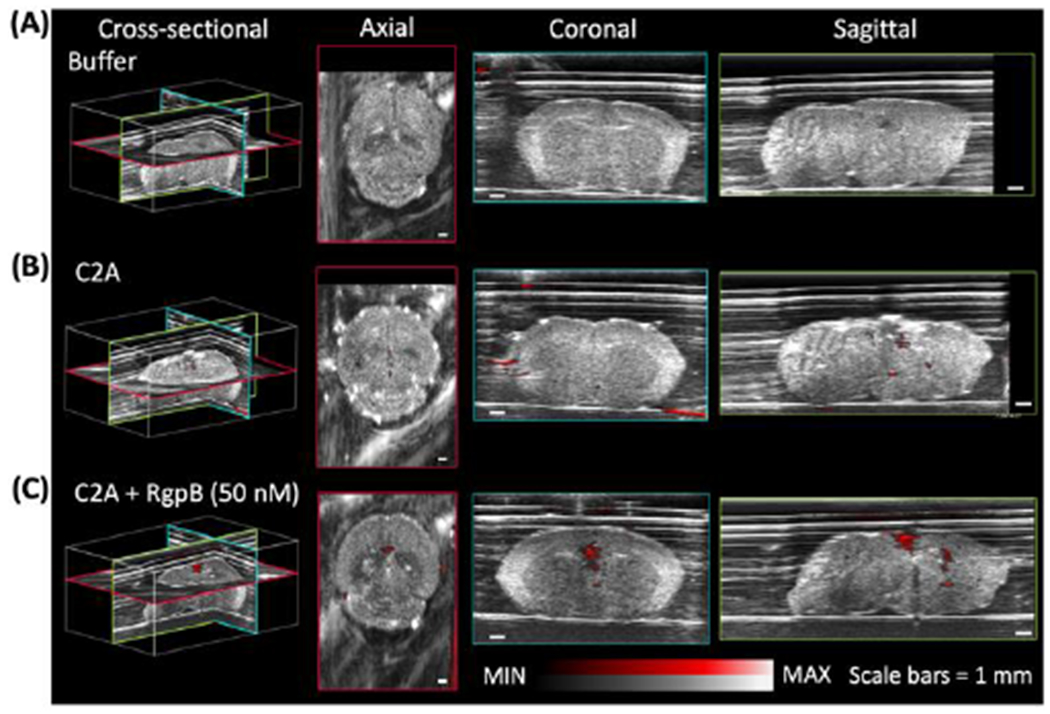

Lastly, the potential role of P. gingivalis and gingipains in neurological pathologies, especially Alzheimer’s disease, is of mounting research interest [13,33]. Photoacoustic imaging is well-suited for real-time imaging and monitoring of murine disease models, and thus we performed proof of concept imaging of cleaved and uncleaved probe in extracted murine brains (fixed in 1% agar). The C2A probe was first incubated with RgpB at increasing probe concentrations to confirm cleavage at sufficient concentrations for imaging in animal tissue (Fig. S28A–B), and the highest tested concentration (30 μM) was chosen for injection (Fig. S28C). Subsequently, aliquots of buffer, C2A, and C2A + RgpB (pre-incubated and monitored for 2 h) were injected into the lambda points of respective brains (Fig. S28D)—these were then imaged in 3D with a photoacoustic-ultrasound scanner at 680 nm using sonography gel for acoustic coupling. Negligible photoacoustic signal was detected in the buffer-injected brain (Fig. 6A), while minor background was observed for the uncleaved probe (Fig. 6B). The strongest signal was detected from the brain injected with C2A + RgpB, visible in axial, coronal, and sagittal cross-sections of the tissue (Fig. 6C). Further, spectral photoacoustic imaging of the injected brains allowed signal from C2A to be distinguished from background by its characteristic absorption/photoacoustic peak in the near infrared (Fig. S29). These experiments demonstrate that the C2A probe could have value as a research tool for gingipain imaging in more complex models of infection for Alzheimer’s disease pathogenesis. Future studies may integrate the probe with in vivo models of P. gingivalis infection, though potential limitations include issues that affect many small-molecule photoacoustic probes, including low signal to background ratio in blood at low concentrations and photoinstability associated with the dissociation of conjugated π electrons following absorption [24,34]. To improve penetration depths and specificity, another future direction may be to leverage more red-shifted dyes for ratiometric photoacoustic imaging[35] between the monomer and dimer peaks of the probe. In this work, the fixed excitation range of the laser (680-970 nm) precluded photoacoustic imaging of the blue-shifted dimer peak. Nevertheless, proof-of-concept imaging utility was demonstrated in the oral cavity and brain parenchyma using resected porcine jaws and murine brains, respectively. Lastly, in future efforts to improve sensitivity to P. gingivalis, a lysine residue could be included in the peptide linker for cleavage by Lys-gingipain (Kgp), in addition to D-amino acids for increased bacterial specificity [15a].

Figure 6.

Photoacoustic imaging of RgpB-activated C2A probe in murine brains. Photoacoustic-ultrasound images of fixed murine brains injected at the lambda point with (A) buffer, (B) C2A probe, and (C) C2A probe + RgpB, show enhanced intraparenchymal photoacoustic signal for RgpB-cleaved probe. Photoacoustic intensity (red) is overlaid on ultrasound intensity (grayscale). Scale bars = 1 mm.

In summary, a molecular imaging probe, C2A, was designed and synthesized to harness the intramolecular dimerization of peptide-linked cyanine dyes to induce fluorescence and photoacoustic off-states. Upon proteolytic cleavage by Arg-specific gingipain (RgpB), 5-fold photoacoustic enhancement and >100-fold fluorescence enhancement was achieved with detection limits of 1.1 nM RgpB and 4.4E4 CFU/mL bacteria. RgpB activity was imaged in the subgingival pocket of porcine mandibles with 25 nM sensitivity. The diagnostic efficacy of the probe was evaluated in gingival crevicular fluid (GCF) samples from subjects with (n = 14) and without (n = 6) periodontal disease; activation correlated to qPCR-based detection of P. gingivalis (Pearson’s r = 0.71), and activity was highest in subjects with the most severe disease progression. Lastly, photoacoustic imaging of RgpB-cleaved probe was demonstrated in murine brains ex vivo, thus demonstrating future utility for imaging studies of general infection by P. gingivalis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge funding from the National Institutes of Health via R21 DE029917, R21 DE029025, UL1TR001442, DP2 HL137187-S1, and S10 OD021821. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. This work was supported in part by the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship Program under grant no. DGE-1650112. C.M. graciously acknowledges funding from the ARCS (Achievement Reward for College Scientists) Foundation. J.V.J. acknowledges the generous support of The Shiley Foundation.

Footnotes

Supporting information for this article is given via a link at the end of the document.

Conflicts of interest

Jesse V. Jokerst is a co-founder of StyloSonic, LLC.

References

- [1].a) Eke PI, Dye BA, Wei L, Slade GD, Thornton-Evans GO, Borgnakke WS, Taylor GW, Page RC, Beck JD, Genco RJ, J. Periodontol 2015, 86, 611–622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Listl S, Galloway J, Mossey P, Marcenes W, J. Dent. Res 2015, 94, 1355–1361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Hajishengallis G, Nat. Rev. Immuno 2014, 15, 30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Kuboniwa M, Lamont RJ, Periodontol. 2000. 2010, 52, 38–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Leng W-D, Zeng X-T, Kwong JS, Hua X-P, Int. J. Cardiol 2015, 201, 469–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Nazir MA, Int. J. Health Sci 2017, 11, 72–80. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Michaud D, Kelsey K, Papathanasiou E, Genco C, Giovannucci E, Ann. Oncol 2016, 27, 941–947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Lee YT, Lee HC, Hu CJ, Huang LK, Chao SP, Lin CP, Su ECY, Lee YC, Chen CC, J. Am. Geriatr. Soc 2017, 65, 301–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Hajishengallis G, Lamont RJ, Mol. Oral Microbiol 2012, 27, 409–419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].a) Byrne SJ, Dashper SG, Darby IB, Adams GG, Hoffmann B, Reynolds EC, Oral Microbiology and Immunology 2009, 24, 469–477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Kinney JS, Morelli T, Oh M, Braun TM, Ramseier CA, Sugai JV, Giannobile WV, J. Clin. Periodontol 2014, 41, 113–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Graves DT, Jiang Y, Genco C, Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis 2000, 13, 227–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Imamura T, J. Periodontol 2003, 74, 111–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].a) Olsen I, Potempa J, Oral Microbiol J. 2014, 6, 24800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Kataoka S, Baba A, Suda Y, Takii R, Hashimoto M, Kawakubo T, Asao T, Kadowaki T, Yamamoto K, The FASEB Journal 2014, 28, 3564–3578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Kadowaki T, Baba A, Abe N, Takii R, Hashimoto M, Tsukuba T, Okazaki S, Suda Y, Asao T, Yamamoto K, Mol. Pharmacol 2004, 66, 1599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Dominy SS, Lynch C, Ermini F, Benedyk M, Marczyk A, Konradi A, Nguyen M, Haditsch U, Raha D, Griffin C, Holsinger LJ, Arastu-Kapur S, Kaba S, Lee A, Ryder MI, Potempa B, Mydel P, Hellvard A, Adamowicz K, Hasturk H, Walker GD, Reynolds EC, Faull RLM, Curtis MA, Dragunow M, Potempa J, Science Advances 2019, 5, eaau3333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Nara PL, Sindelar D, Penn MS, Potempa J, Griffin WST, Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease 2021, 82, 1417–1450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].a) Kaman Wendy E, Galassi F, de Soet Johannes J, Bizzarro S, Loos Bruno G, Veerman Enno CI, van Belkum A, Hays John P, Bikker Floris J, J. Clin. Microbiol 2012, 50, 104–112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Alhogail S, Suaifan GA, Bizzarro S, Kaman WE, Bikker FJ, Weber K, Cialla-May D, Popp J, Zourob M, Microchimica Acta 2018, 185, 149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Svärd A, Neilands J, Palm E, Svensäter G, Bengtsson T, Aili D, ACS Applied Nano Materials 2020, 3, 9822–9830. [Google Scholar]

- [17].Liu S, Wang Y.-n., Ma B, Shao J, Liu H, Ge S, ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 2021, 13, 36880–36893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Miao Q, Pu K, Bioconjugate Chemistry 2016, 27, 2808–2823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].a) AlKahtani RN, The Saudi Dental Journal 2018, 30, 107–116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Hannig M, Hannig C, Nature Nanotechnology 2010, 5, 565–569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Tattan M, Sinjab K, Lee E, Arnett M, Oh T-J, Wang H-L, Chan H-L, Kripfgans OD, J. Periodontol 2020, 91, 890–899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].a) Joshi BP, Zhou J, Pant A, Duan X, Zhou Q, Kuick R, Owens SR, Appelman H, Wang TD, Bioconjugate Chemistry 2016, 27, 481–494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Trabuco LG, Lise S, Petsalaki E, Russell RB, Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, W423–W427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Eichinger A, Beisel H-G, Jacob U, Huber R, Medrano F-J, Banbula A, Potempa J, Travis J, Bode W, The EMBO Journal 1999, 18, 5453–5462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Ally N, Whisstock JC, Sieprawska-Lupa M, Potempa J, Le Bonniec BF, Travis J, Pike RN, Biochemistry 2003, 42, 11693–11700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Petsalaki E, Stark A, García-Urdiales E, Russell RB, PLOS Computational Biology 2009, 5, e1000335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Moore C, Borum RM, Mantri Y, Xu M, Fajtová P, O’Donoghue AJ, Jokerst JV, ACS Sens. 2021, 6, 2356–2365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Jung Y-J, Jun H-K, Choi B-K, J. Oral Microbiol 2017, 9, 1320193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Jayaprakash K, Khalaf H, Bengtsson T, BMC Microbiol. 2014, 14, 193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Houle M-A, Grenier D, Plamondon P, Nakayama K, FEMS Microbiol. Lett 2003, 221, 181–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Park S, Park K, Na HS, Chung J, Yang H, Anal. Chem 2021, 93, 5644–5650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Skottrup PD, Leonard P, Kaczmarek JZ, Veillard F, Enghild JJ, O’Kennedy R, Sroka A, Clausen RP, Potempa J, Riise E, Anal. Biochem 2011, 415, 158–167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].a) Moore C, Bai Y, Hariri A, Sanchez JB, Lin C-Y, Koka S, Sedghizadeh P, Chen C, Jokerst JV, Photoacoustics 2018, 12, 67–74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Mozaffarzadeh M, Moore C, Golmoghani EB, Mantri Y, Hariri A, Jorns A, Fu L, Verweij MD, Orooji M, de Jong N, Jokerst JV, Biomedical Optics Express 2021, 12, 1543–1558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Lin C, Chen F, Hariri A, Chen C, Wilder-Smith P, Takesh T, Jokerst J, J. Dent. Res 2018, 97, 23–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Yang H, Kim J, Nam W, Kim HJ, Cha I.-h., Kim D, Journal of Clinical Medicine 2021, 10, 410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Guentsch A, Kramesberger M, Sroka A, Pfister W, Potempa J, Eick S, J. Periodontol 2011, 82, 1051–1060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].a) Nakanishi H, Nonaka S, Wu Z, CNS & Neurological Disorders-Drug Targets (Formerly Current Drug Targets-CNS & Neurological Disorders) 2020, 19, 495–502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Ryder MI, Periodontol J. 2020, 91, S45–S49 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Haditsch U, Roth T, Rodriguez L, Hancock S, Cecere T, Nguyen M, Arastu-Kapur S, Broce S, Raha D, Lynch CC, Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease 2020, 75, 1361–1376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Stahl T, Allen T, Beard P, in Photons Plus Ultrasound: Imaging and Sensing 2014, Vol. 8943, International Society for Optics and Photonics, 2014, p. 89435H. [Google Scholar]

- [35].a) Li Q, Ge X, Ye J, Li Z, Su L, Wu Y, Yang H, Song J, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2021, 60, 7323–7332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Zhang X, Li Z-W, Wu Y, Ge X, Su L, Feng H, Wu Z, Yang H, Song J, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2021, 60, 17647–17653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.