Abstract

Objective

The purpose of this descriptive study was to evaluate the presence of telehealth content on chiropractic state board websites compared with websites from the medical and physical therapy professions during the early COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

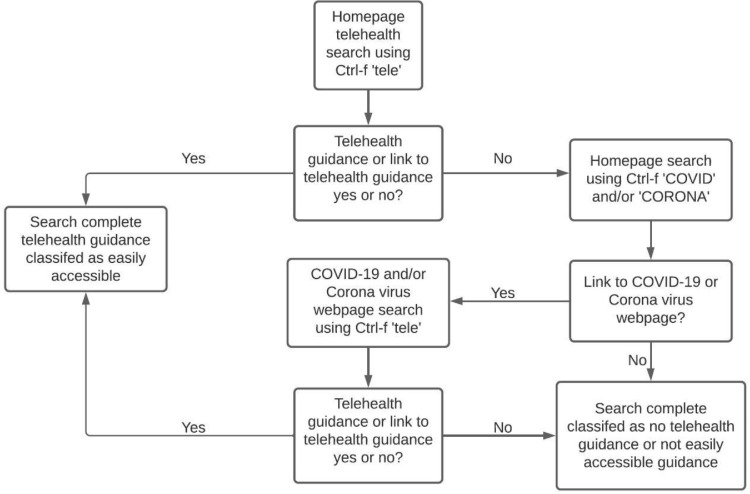

State board websites for chiropractic, medicine, and physical therapy for each of the 50 United States and the District of Columbia were searched for the word “tele” to determine if there was a link on the homepage for content related to telehealth guidance. If there was none, the homepage was queried for the word “COVID” to determine if there was a link for COVID-19–related guidance. If yes, that linked COVID-19 page was queried for the word “tele.” Consensus of 4 of 5 reviewers was sought. Binary results were entered into a separate spreadsheet for each profession (telehealth content easily accessible, yes or no). Easily accessible was defined as information found within 1 or 2 clicks. This search was performed between January 1, 2021, and March 1, 2021.

Results

There were 11 of 51 (21%) chiropractic state board websites that provided content regarding telehealth on the main page, 8 of 51 (16%) provided content on a separate COVID-19–related page, and 32 of 51 (63%) did not provide content that was accessible within 1 or 2 clicks. Comparatively, 9 of 51 (18%) medical state board websites provided content regarding telehealth on the main page, 20 of 51 (39%) provided content on a COVID-19–related page, and 22 of 51 (43%) did not provide content that was accessible within 1 or 2 clicks. Lastly, 10 of 51 (20%) physical therapy state board websites provided content regarding telehealth on the main page, 19 of 51 (37%) provided content on a COVID-19–related page, and 22 of 51 (43%) did not provide content that was accessible within 1 or 2 clicks.

Conclusion

Telehealth content was more readily available on medical and physical therapy state board websites compared with chiropractic state board websites in the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Key Indexing Terms: COVID-19, Chiropractic, Telemedicine, Physical Therapy Modalities

Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) was classified as a pandemic in March 2020 by the World Health Organization.1 To slow the spread of COVID-19 and to minimize the burden placed on the health care system in the United States (US), government organizations issued stay-at-home orders. The orders urged travel to be limited to obtaining food, seeking medical treatment, and reporting for essential employment, and they varied between state and local governments.2,3

As ambulatory clinics closed or limited face-to-face encounters in response to COVID-19 stay-at-home orders, access to care and telehealth became increasingly important. Chiropractors, physical therapists, and medical physicians used telehealth to triage and manage patients with musculoskeletal (MSK) pain.4 Empowering chiropractors and other providers to utilize telehealth allowed them to properly triage and manage patients and potentially prevented them from reporting to the emergency department unnecessarily with MSK pain, further stressing the US health care system in a time of crisis.5

Telehealth usage varied among health care professions before the beginning of the pandemic. Providers newly implementing telehealth services should be familiar with the professional regulations specific to their locality. A reasonable place to seek out practice guidelines, regardless of profession, would be their state board website. There was limited availability of web-based guidance for the chiropractic profession, which included telehealth guidance.3 Up to this point in time, there has been no assessment of the ease of accessibility of telehealth guidance or a comparison of information with other health care professions in the US.

Most chiropractors practice in private practice settings, while many physical therapists and medical doctors are part of larger health care organizations.6 These larger health care organizations often provide infrastructure, standard operating procedures, and guidance regarding changes in practice, such as transitioning to telehealth. Chiropractors, who largely operate small private practices, must turn to their state boards for guidance on procedures such as telehealth. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the presence of telehealth content on chiropractic state board websites compared with medical and physical therapy board websites during the early COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

This study was a descriptive study of publicly available websites. We chose physical therapy and medical professions as comparators because they, like chiropractors, frequently manage patients with chronic MSK conditions. The study was completed between January 1, 2021, and March 1, 2021. State board websites were accessed from the federation of state licensing boards websites for the chiropractic, medical, and physical therapy professions, respectively. If no hyperlink was available on the federation website, then Google.com was used to search for the state's licensing board website. Once on the state board website, a “search and find” method was used (CTRL + F on the Windows operating system [Microsoft, Redmond, WA]) to query the website for the term “tele,” which allowed for capture of various uses of the prefix (eg, telehealth, telerehabilitation, telemedicine). If that search returned either a guidance statement or a hyperlink to guidance information about telehealth, then that state was considered to have met criteria for providing guidance in an easily accessible manner. No further steps were taken if content related to telehealth guidance was easily accessible, as defined at the end of this section.

If there was no content related to guidance found about telehealth, then an additional search was performed using the terms “COVID” and/or “corona” to allow for the possibility of a hyperlinked webpage that may contain telehealth guidance in a separate location. If this search returned a separate webpage, then the COVID-19 webpage was also queried for the term “tele.” If guidance was available on this separate webpage, the state was still considered to have provided guidance in an easily accessible manner. Figure 1 provides a detailed flowchart of the study protocol.

Fig 1.

Flowchart diagram of study protocol.

The same protocol was used for the medical and physical therapy professions for each of the 50 states and the District of Columbia (DC). A separate spreadsheet for each profession was used to track the 3-step term search as “yes” or “no.” A total of 5 reviewers were involved in data collection. Three separate reviewers performed the protocol initially of all 50 states and DC for each profession. To reduce bias, multiple reviewers followed the same study protocol independently. Results were binary (“yes” or “no”), indicating whether guidance was or was not accessible via state board website. For any state where all 3 reviewers were not in agreement, 2 additional reviewers repeated the protocol. For those states, consensus was agreement of 4 of 5 reviewers. If any state had agreement of only 3 of the 5 reviewers, then the entire protocol was repeated by all reviewers, and the state was discussed until consensus was reached.

We defined guidance to be easily accessible if it could be found directly on the homepage or through a hyperlink that indicated it would lead specifically to telehealth guidance. Alternatively, a separate COVID-19 page, linked from the homepage, could have contained the guidance or hyperlinked to guidance. Easily accessible guidance for our purposes was defined as being available within 1 or 2 clicks from the state board homepage.

We defined “no guidance” as information that could not be found within 1 or 2 clicks. It is possible that state boards had telehealth guidance that could be found with multiple clicks from the board homepage, but we did not consider this as accessible.

Results

There were 11 of 51 (21%) chiropractic state board websites that provided guidance regarding telehealth on the main page, 8 of 51 (16%) provided guidance on a separate COVID-19–related page, and 32 of 51 (63%) did not have guidance that was easily accessible. For the medical profession, 9 of 51 (18%) state board websites provided guidance regarding telehealth on the main page, 20 of 51 (39%) provided guidance on a COVID-19–related page, and 22 of 51 (43%) did not have guidance that was easily accessible. For the physical therapy profession, 10 of 51 (20%) state board websites provided guidance regarding telehealth on the main page, 19 of 51 (37%) provided guidance on a COVID-19–related page, and 22 of 51 (43%) did not have guidance that was easily accessible (Table 1). Five states and DC (chiropractic), 7 states (medical), and 1 state (physical therapy) required input from 2 additional reviewers because the first 3 reviewers were not in agreement.

Table 1.

State by State Summary of Whether Telehealth Guidance Was Present on the Given Webpages for Each of the Respective Professions

| State or District | Telehealth Guidance or Link on Main Page? |

Has a Separate COVID-19 Page? |

Telehealth Guidance or Link on Separate COVID-19 Page? |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DC | MD | PT | DC | MD | PT | DC | MD | PT | |

| Alabama | No | Yes | No | Yes | N/A | Yes | No | N/A | Yes |

| Alaska | Yes | Yes | Yes | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Arizona | Yes | No | Yes | N/A | Yes | N/A | N/A | Yes | N/A |

| Arkansas | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | N/A | N/A | No | N/A | N/A |

| California | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | N/A | N/A | No |

| Colorado | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No |

| Connecticut | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No |

| Delaware | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No |

| District of Columbia | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No |

| Florida | No | No | No | No | No | No | N/A | N/A | No |

| Georgia | No | Yes | No | No | N/a | No | N/A | N/A | No |

| Hawaii | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No |

| Idaho | Yes | No | Yes | N/A | Yes | N/A | N/A | Yes | N/A |

| Illinois | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Indiana | No | Yes | No | Yes | N/A | Yes | No | N/A | No |

| Iowa | No | Yes | No | Yes | N/A | Yes | No | N/A | Yes |

| Kansas | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| Kentucky | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Louisiana | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| Maine | Yes | No | No | N/A | Yes | Yes | N/A | Yes | No |

| Maryland | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | N/A | N/A | Yes | N/A |

| Massachusetts | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No |

| Michigan | No | No | No | No | No | No | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Minnesota | Yes | No | No | N/A | Yes | No | N/A | No | No |

| Mississippi | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | N/a | No | No | N/A |

| Missouri | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| Montana | No | Yes | No | Yes | N/a | Yes | Yes | N/A | Yes |

| Nebraska | Yes | No | Yes | N/A | No | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Nevada | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No |

| New Hampshire | No | Yes | No | No | N/A | Yes | N/A | N/A | No |

| New Jersey | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| New Mexico | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| New York | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| North Carolina | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| North Dakota | No | No | No | No | No | No | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Ohio | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| Oklahoma | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | N/A |

| Oregon | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Pennsylvania | Yes | Yes | No | N/A | N/A | Yes | N/A | N/A | Yes |

| Rhode Island | No | No | No | No | No | No | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| South Carolina | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No |

| South Dakota | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | N/A | N/A |

| Tennessee | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No |

| Texas | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | N/A | No | Yes | N/A |

| Utah | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Vermont | Yes | No | No | N/A | Yes | Yes | N/A | No | Yes |

| Virginia | Yes | No | Yes | N/A | Yes | N/A | N/A | Yes | N/A |

| Washington | Yes | No | No | N/A | No | Yes | N/A | N/a | No |

| West Virginia | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| Wisconsin | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | N/A | Yes | N/A |

| Wyoming | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | N/A | No | Yes | N/A |

“Yes” denotes guidance or a link directly to guidance was present, “No” denotes that no telehealth guidance was present on the perspective webpage, and “N/A” denotes that telehealth guidance was present on a prior webpage or there was no existing webpage of that nature. The table represents consensus of at least 4 of 5 reviewers.

DC, chiropractic; MD, medicine; PT, physical therapy.

National guidance regarding telehealth was provided on the federation of licensing boards websites for the medical and physical therapy boards but not for the chiropractic boards. The Federation of State Medical Boards homepage featured a static “COVID-19 Resources” link where telehealth information could be found, as well as links to state-by-state telehealth information. A similar link was featured on the Federation of State Boards of Physical Therapy homepage, but the link was on a rotating banner and was visible for only 8 seconds and would not reappear for 48 seconds. So, it is possible someone could visit the homepage and miss the COVID-19 link.

Discussion

According to our search, there were fewer US chiropractic state board websites in comparison to the physical therapy and medical state board websites that included accessible telehealth guidance in the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. In response to the pandemic, state governments issued stay-at-home orders that varied from state to state, limiting travel to what was deemed “essential.” Workers, including chiropractors, medical doctors, and physical therapists, were categorized as essential or nonessential.2,3 Some states quickly categorized chiropractors as essential personnel, while other states took no formal position.3

On March 17, 2021, the Federation of Chiropractic Licensing Boards’ (FCLB) leadership issued a statement affirming that chiropractors were essential health care providers. The FCLB also contacted governors and state officials to communicate the importance of chiropractic care in mitigating the burden of MSK conditions on the health care system, thereby preserving other valuable medical resources. On March 25, 2021, the FCLB leadership sent a letter to the director of the US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, outlining chiropractic services as essential in supporting the health care system during the pandemic.7 The US Department of Homeland Security issued a memo on March 28, 2020, that classified chiropractors as essential health care workers.8 However, the memo was advisory rather than a formal federal mandate, and chiropractors were to turn to their state board regulators for more formal guidance.9 While the FCLB did aim to work with state officials and governors, they did not provide guidance on the utilization of telehealth.

Kentucky was the only state to categorize chiropractors as nonessential health care providers, shuttering chiropractic clinics from March 20, 2020, until April 27, 2020.10,11 Colorado also closed chiropractic clinics from March 19, 2020, to April 6, 2020.12 There was no mention on whether chiropractic practices could continue to operate using telehealth services. Ensuring easy to access telehealth guidance could improve continuity of care, enhance patient care, and limit income loss for private practice providers in the event of another pandemic or similarly disruptive event where clinics may be shuttered.

Although telehealth may be mentioned within some states' chiropractic scope of practice descriptions, over half of the chiropractic state boards did not provide guidance that was easily accessible as defined by our methods. We recommend that in times of emergencies, such as COVID-19, that state boards act quickly with the adaptation of state board websites to set forward-facing emphasis on practice guidance. Such guidance would be most accessible via the homepage or a direct link from the homepage to a COVID-19 resource page. We also recommend that the FCLB provide state-by-state summaries of guidance similar to the federation sites for other professions.13

We believe it is important that information regarding COVID-19 and telehealth be easy to access for clinicians. Even while following a detailed, step-by-step protocol and using a search feature, it was difficult to locate telehealth guidance and for the 5 reviewers to come to a consensus in some cases. We believe this highlights the difficulty of accessing and interpreting the information. Having telehealth and COVID-19 links on rotating banners makes the information harder to locate because the link may not be visible while searching that section of the page, and it often disables the search feature. Maine was an example of a state board website that provided easy-to-find guidance. The homepage featured a COVID-19 resources tab with various COVID-19 links for chiropractors, including a link titled “COVID-19 Telehealth Resources.” This linked to a document that provided detailed guidance for chiropractors on providing telehealth, including a telehealth toolkit, telehealth resources page, and “Provider Guide to Telehealth Reimbursement During COVID-19,” which specifically listed chiropractors.14 This telehealth guidance was easy to find from the homepage, with the information all in one place under the “COVID-19 Telehealth Resources” link.

While there are currently no systematic reviews or clinical trials pertaining to chiropractic practice and telehealth, there is some evidence that demonstrates the utility of telehealth in managing musculoskeletal conditions frequently encountered by chiropractors.15 The first step in managing musculoskeletal conditions is properly triaging the patient. This is primarily done through obtaining a patient history, which can be done via telehealth and can allow the practitioner to rule in or out red flags and determine if the patient requires emergent attention. In addition to obtaining a history, a brief exam can be performed using video platforms. The virtual exam can be used to assess for signs of neural tension, overt weakness, or red flags. There is growing evidence that exams completed via telehealth are reliable and often lead to the same or similar clinical decisions as face-to-face assessments.5

Not only can a patient with MSK concerns be adequately assessed via telehealth, but telehealth rehabilitation may be at least as effective as standard face-to-face care for various MSK conditions.16 Another study also supports the use of synchronous telehealth for the nonpharmacological management of nonacute MSK conditions.17 Green et al18 described the rapid deployment of remote MSK care via telehealth using video platforms for chiropractic services within 2 integrated health centers, highlighting the ability of chiropractic services to transition quickly to telehealth during a pandemic.

Many of the risk factors for chronic pain overlap with those risk factors for poorer outcomes after infection with COVID-19.19,20 Additionally, longer wait times for patients with chronic pain to see a provider may be associated with higher reported pain levels and difficulties with activities of daily living which is associated with depression in 50% and suicidal thoughts in 34.5%.21 Telehealth could reduce potential exposure to pathogens, especially for those at higher risk of poorer outcomes after COVID-19 infection, allow for continuity of care for chronic pain, and reduce wait times caused by clinic shuttering, but clinicians would need guidance on its use.

We believe clinicians would benefit most from guidance that is easily accessible to minimize impact on the health care system in the event of a pandemic or similarly disruptive event. We recommend that important guidance, such as telehealth guidance, be available on static links on either the homepage or event-specific webpage, such as a COVID-19 resources webpage. We suggest that guidance clearly state which types of providers can utilize telehealth, which platforms are currently acceptable for use, and how to properly code and bill for telehealth.

Limitations

A limitation of this study is that our primary results were limited to the homepage or a central COVID-19 webpage on each profession's state board website. Telehealth guidance may be elsewhere on the state board website and not directly found on the homepage or central COVID-19 webpage. However, we chose to focus only on the main pages to highlight the need for this information to be easily accessible during a time of emergency such as the COVID-19 pandemic. Also, we did not aim to determine which states sanctioned telehealth or not for each profession but rather to determine if there was any guidance at all. Therefore, we did not assess the individual guidance of each state or aim to critically critique such guidance. This guidance could include resources to providers for utilizing telehealth or could inform providers that they were not eligible to perform telehealth, and guidance provided varied among states and professions. In some cases, the linked telehealth guidance may or may not directly reference chiropractic practice. Another limitation of this study is that we compared chiropractic with the medical and physical therapy professions but did not include other relevant professions such as occupational therapy. Additionally, our search included only DC and the 50 states, and it did not aim to include Puerto Rico or other US territories. We did not evaluate other countries; therefore, our findings are limited to the US. We recognize that telehealth is a relatively new concept to the chiropractic profession and that could possibly be a reason state boards did not include this information. Lastly, any changes in telehealth guidance on the state board websites that took place after March 1, 2021, were not captured in this study.

Conclusion

During the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic, we found that it was easier to find content on medical and physical therapist state board websites relating to telehealth practice compared with chiropractic state board websites. According to our search, telehealth guidance was easily accessible on 37% of chiropractic state board websites, compared with 56% of state board websites for the medical and physical therapy professions.

Funding Sources and Conflicts of Interest

No funding sources or conflicts of interest were reported for this study. The views expressed in this article are the views of the authors and do not represent the views of the United States Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government.

Contributorship Information

Concept development (provided idea for the research): M.R.C., R.M., J.G.N.

Design (planned the methods to generate the results): M.R.C., R.M., J.G.N.

Supervision (provided oversight, responsible for organization and implementation, writing of the manuscript): M.R.C., R.M., J.G.N.

Data collection/processing (responsible for experiments, patient management, organization, or reporting data): M.R.C., R.M., J.G.N., F.B., H.T.

Analysis/interpretation (responsible for statistical analysis, evaluation, and presentation of the results): M.R.C., R.M.

Literature search (performed the literature search): M.R.C., R.M.

Writing (responsible for writing a substantive part of the manuscript): M.R.C., R.M., J.G.N., H.T., F.B.

Critical review (revised manuscript for intellectual content, this does not relate to spelling and grammar checking): M.R.C., R.M., J.G.N., H.T., F.B.

Practical Applications.

-

•

We compared the ease of accessibility of telehealth content on chiropractic state board webpages and compared the accessibility of guidance to other professions.

-

•

State board websites were searched for the word “tele” to determine if there was a link on the homepage for telehealth guidance.

-

•

Telehealth content was more readily available on medical and physical therapy state board websites compared with chiropractic state board websites in the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Alt-text: Unlabelled box

References

- 1.Fauci AS, Lane HC, Redfield RR. COVID-19 - navigating the uncharted. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(13):1268–1269. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe2002387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. COVID-19. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/communication/guidance-list.html. Accessed February 19th, 2021.

- 3.Neff SM, Roecker CB, Okamoto CS, et al. Guidance concerning chiropractic practice in response to COVID-19 in the U.S.: a summary of state regulators' web-based information. Chiropr Man Therap. 2020;28(1):44. doi: 10.1186/s12998-020-00333-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schielke AL, Babikian AR, Walsh RW, Rajagopal P. Implementation of musculoskeletal specialists in the emergency department at a level A1 VA Hospital during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Am J Emerg Med. 2021;46:722–723. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2020.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cottrell MA, O'Leary SP, Swete-Kelly P, et al. Agreement between telehealth and in-person assessment of patients with chronic musculoskeletal conditions presenting to an advanced-practice physiotherapy screening clinic. Musculoskelet Sci Pract. 2018;38:99–105. doi: 10.1016/j.msksp.2018.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Board of Chiropractic Examiners . 2020. Practice analysis of chiropractic.https://mynbce.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Practice-Analysis-of-Chiropractic-2020-5.pdf Available at: Accessed February 9, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johnson CD, Little CS, Sterling TA, Gojkovich S, Boghosian K, Ciolfi MA. Response of chiropractic organizations to the COVID-19 pandemic: a descriptive report. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2020;43(5):405.e1–405.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2020.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cybersecurity & Infrastructure Security Agency. Advisory memorandum on ensuring essential critical infrastructure workers' ability to work during the COVID-19 response. Available at: https://www.cisa.gov/sites/default/files/publications/ECIW_4.0_Guidance_on_Essential_Critical_Infrastructure_Workers_Final3_508_0.pdf. Accessed February 19, 2021.

- 9.American Chiropractic Association. Coronavirus (COVID-19). Available at: https://www.acatoday.org/News-Publications/Coronavirus-COVID-19. Accessed February 19, 2021.

- 10.Kentucky Cabinet for Health and Family Services Office of Legal Services. Elective procedure directive. Available at:https://chfs.ky.gov/agencies/dph/covid19/electiveproceduredirective.pdf. Accessed February 19, 2021.

- 11.Kentucky.gov. Gov. Beshear details next phases in reopening of health care industry. Available at:https://kentucky.gov/Pages/Activity-stream.aspx?n=GovernorBeshear&prId=146. Accessed February 19, 2021.

- 12.Colorado Official State Web Portal. Executive Order—Ordering the temporary cessation of all elective and non-essential surgeries and procedures and preserving personal protective equipment and ventilators in Colorado due to the presence of COVID-19. Available at:https://www.colorado.gov/governor/sites/default/files/inline-files/D%202020%20009%20Ordering%20Cessation%20of%20All%20Elective%20Surgeries_0.pdf. Accessed February 19, 2021.

- 13.Federation of Chiropractic Licensing Boards. COVID-19. Available at: https://www.fclb.org/Home/AboutUs/COVID-19.aspx. Accessed February 19, 2021.

- 14.State of Main Professional & Financial Regulation. Chiropractic licensure. Available at:https://www.maine.gov/pfr/professionallicensing/professions/chiropractic-licensure. Accessed February 19, 2021.

- 15.Bucki F, Clay M, Tobiczyk H, King A. Association of Chiropractic Colleges Research Agenda Conference 2020 Abstracts of Proceedings. J Chiropr Educ. 2022;34(1):58–72. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cottrell MA, Galea OA, O'Leary SP, Hill AJ, Russell TG. Real-time telerehabilitation for the treatment of musculoskeletal conditions is effective and comparable to standard practice: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Rehabil. 2017;31(5):625–638. doi: 10.1177/0269215516645148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Corso M, Cancelliere C, Mior S, et al. Are non-pharmacological interventions delivered through synchronous telehealth as effective and safe as in-person interventions for the management of patients with non-acute musculoskeletal conditions? A systematic rapid review. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2022;103(1):145–154. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2021.09.007. e11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Green BN, Pence TV, Kwan L, Rokicki-Parashar J. Rapid deployment of chiropractic telehealth at 2 worksite health centers in response to the COVID-19 pandemic: observations from the field. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2020;43(5):404.e1–404.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2020.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mills SEE, Nicolson KP, Smith BH. Chronic pain: a review of its epidemiology and associated factors in population-based studies. Br J Anaesth. 2019 Aug;123(2):e273–e283. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2019.03.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li J, Huang DQ, Zou B, et al. Epidemiology of COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical characteristics, risk factors, and outcomes. J Med Virol. 2021;93(3):1449–1458. doi: 10.1002/jmv.26424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Choinière M, Dion D, Peng P, et al. The Canadian STOP-PAIN project - Part 1: who are the patients on the waitlists of multidisciplinary pain treatment facilities? Can J Anaesth. 2010;57(6):539–548. doi: 10.1007/s12630-010-9305-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]