Abstract

The rapid spread of COVID-19 has a potentially significant impact on not only physical health but also psychological well-being. To the best of our knowledge, no review thus far has consolidated the psychological impact of COVID-19 across different subpopulations. A systematic search of the literature until 15 June 2020 found 150 empirical papers pertinent to the mental health consequences of the pandemic. The majority (87.3%) were from China (45.3%), the rest of Asia (22.0%) and Europe (20.0%), and mostly examined the general population (37.3%), healthcare workers (31.3%) and those with pre-existing mental and physical illnesses (14.7%). The most common psychological responses across these subpopulations were anxiety (overall range 24.8%–49.5%), depression (overall range 18.6%–42.6%) and traumatic stress symptoms (overall range 12.7%–31.6%). Healthcare workers and those with pre-existing physical and mental illnesses were more severely affected. Future studies are needed on underexamined subgroups such as the elderly and patients who recovered from COVID-19.

Keywords: healthcare workers, infectious diseases, psychological responses, vulnerable populations

INTRODUCTION

The severity and rapid spread of COVID-19 has had a significant impact on not only the physical health of communities worldwide but also their psychological well-being. This issue is of particular concern as the battle against this pandemic becomes increasingly long-drawn and strict infection control measures have been implemented. These measures will be eased at different rates around the world but may be reinstated with new waves of infection. As of 15 June 2020, COVID-19 had infected more than eight million people across 213 countries and territories; more than 435,000 people had died from the disease and over 4.1 million had recovered.(1)

Previous studies on the psychological impact of infectious diseases have commonly reported responses in the general population such as anxiety/fear, depression, anger, guilt, grief and loss, post-traumatic stress and stigmatisation. However, there is also a greater sense of empowerment and compassion towards others.(2) Healthcare workers at the forefront of the fight against infectious diseases experience various stressors such as the fear of getting infected, losing control of the spread of the virus, and passing the virus on to their family and friends.(3) Based on these past experiences, the potential mental health repercussions of infectious disease outbreaks are increasingly being recognised and acknowledged during the current COVID-19 pandemic.

To date, although there have been various international studies on the psychosocial responses related to COVID-19, no review thus far has consolidated the extant psychological impact on the different subpopulations, such as the general population, healthcare workers and vulnerable populations, including patients with pre-existing physical or psychiatric illnesses. Hence, we aimed to examine and summarise existing studies to date regarding the psychological impact of COVID-19 on various populations through a rapid review. Understanding the psychological ramifications of this pandemic could inform healthcare systems to target policy decisions for specific populations, and to anticipate and prepare for a protracted battle against COVID-19, in the face of globally dyssynchronous and varied infection control measures.

METHODS

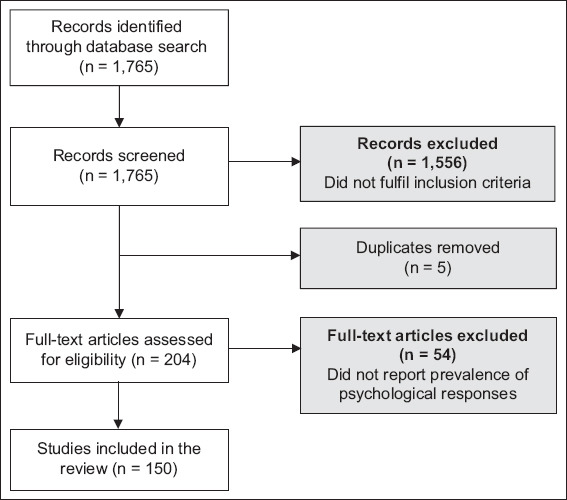

We performed a systematic search of the available literature using PubMed and MEDLINE (Ovid). The following search strategy was used ((‘Betacoronavirus’[Mesh] OR ‘Coronavirus Infections’[MH] OR ‘Spike Glycoprotein, COVID-19 Virus’[NM] OR ‘COVID-19’[NM] OR ‘Coronavirus’[MH] OR ‘Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2’[NM] OR 2019nCoV[ALL] OR Betacoronavirus*[ALL] OR Corona Virus*[ALL] OR Coronavirus*[ALL] OR Coronovirus*[ALL] OR CoV[ALL] OR CoV2[ALL] OR COVID[ALL] OR COVID19[ALL] OR COVID-19[ALL] OR HCoV-19[ALL] OR nCoV[ALL] OR ‘SARS CoV 2’[ALL] OR SARS2[ALL] OR SARSCoV[ALL] OR SARS-CoV[ALL] OR SARS-CoV-2[ALL] OR Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome CoV*[ALL]) AND (mental health OR psychiatric OR psychological)) based on recommendations.(4) Papers that were published from database inception to 15 June 2020 were considered for inclusion. Only empirical studies in the English language and papers from peer-reviewed journals that reported the psychological impact of COVID-19 on one or more populations were included. Case studies, reviews, qualitative studies and dissertations were excluded. Studies that did not report the rates or prevalence of psychological responses were also excluded. A PRISMA flow diagram depicting how articles were selected is presented in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA chart shows the article selection process.

RESULTS

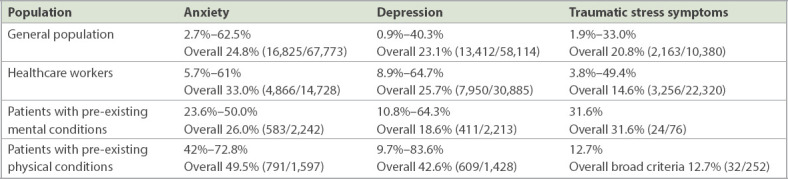

The majority of the 150 included papers originated from Asia (67.3%, n = 101), Europe (20.0%, n = 30) and North America (9.3%, n = 14). Anxiety, depression and traumatic distress were the three commonest reported psychological responses across all papers, with prevalence rates ranging from 2.7%(5) to 72.8%,(6) 0.9%(7) to 83.6%(6) and 1.9%(8) to 96.2%,(9) respectively. Detailed prevalence rates are reported in the Appendix.(5-154) Out of the 150 studies, 56 (37.3%) explored psychological responses in the general population, while 47 (31.3%) reported them within healthcare workers. Only 22 (14.7%) studies examined psychological responses in patients with pre-existing mental and physical conditions. In the general population, the prevalence of anxiety ranged from 2.7%(5) to 62.5%,(10) while that of depression ranged from 0.9%(5) to 40.3%(11) and that of post-traumatic stress symptoms ranged from 1.9%(12) to 33.0%.(13) Among healthcare workers, the prevalence of anxiety ranged from 5.7%(14) to 61.0%,(15) that of depression ranged from 8.9%(16) to 64.7%,(17) and that of post-traumatic stress symptoms ranged from 3.8%(18) to 49.4%.(19) Among patients with pre-existing mental illnesses, the prevalence of anxiety was 23.6%(5) to 50.0%(20) and that of depression was 10.8%(8) to 64.3%,(20) while only one paper reported the prevalence of post-traumatic stress symptoms to be 31.6%.(5) Among patients with pre-existing physical conditions, the prevalence of anxiety ranged from 42.0%(21) to 72.8%,(6) while that of depression ranged from 9.7%(22) to 83.6%.(6) There were relatively fewer reports on younger persons (children and youths), quarantined subgroups and COVID-19 patients. Available data suggests that the younger subgroup reported substantial rates of anxiety ranging from 24.9%(23) to 45.5%,(24) depression ranging from 9%(25) to 48.1%(26) and traumatic stress ranging from 2.7%(25) to 31.8%.(27) Those who were quarantined reported anxiety ranging from 10.2%(28) to 50.3%,(29) depression ranging from 9.0%(25) to 22.4%(30) and traumatic stress ranging from 2.7%.(25) Patients suffering from COVID-19 infection reported anxiety ranging from 2.4%(31) to 55.3%,(12) depression ranging from 12.2%(31) to 60.2%(12) and traumatic stress ranging from 1%(12) to 96.2%.(9) Table I summaries the overall prevalence rates of COVID-19-related psychological responses among the different populations.

Table I.

Overall prevalence rates of COVID-19-related psychological responses among different populations.

Measures proposed to address the mental health repercussions of the pandemic could be grouped into individual and collective measures. A total of 16 papers proposed measures that an individual could take, including ensuring adequate rest and exercise,(32-34) increasing one’s self-awareness of emerging psychological stressors and mental health issues,(32,35) and boosting one’s sense of control.(35) Collective measures proposed by 129 papers include regular crisis communications in order to ensure that accurate information is disseminated in a timely manner.(36-39) False information should also be filtered out and corrected as soon as possible.(39,40) There is a need to continually assess and monitor the psychological well-being of various populations (e.g. general population, healthcare workers and those with pre-existing physical or psychiatric conditions) in order to identify those at risk and offer early intervention.(15,41,42) It has been recommended that adequate resources be allocated to mental health interventions, which should be made available and acceptable to various subpopulations through channels, including digital means.(43) Disruption to essential medical services should be kept to a minimum such that those with pre-existing medical conditions can be supported throughout this pandemic.(44) In addition, financial and social support may be helpful for reducing the repercussions for mental health that can arise from job losses or prolonged quarantine.(30,45-48)

DISCUSSION

Our rapid review sought to capture an overview of psychological responses to date in various populations during the COVID-19 pandemic. We found that most studies focused on the general adult population, healthcare workers and the vulnerable (defined as those with pre-existing physical and psychiatric illnesses), and anxiety, depression and traumatic stress were the more commonly reported responses across studies.

By geographical region, the majority of the studies conducted were from Asia (101 papers, 67.3%), especially China (68 papers, 45.3%), followed by Europe (30 papers, 20.0%). This is likely because China was the first country to discover and experience the rapid spread of COVID-19, followed by countries in Europe. Other countries may learn from the experiences of Asia (such as China) and Europe to better plan to serve mental healthcare needs in response to changes in the respective epidemic curves over time.

In terms of prevalence rate, healthcare workers tended to report higher rates of anxiety (overall 33.0%, 4,866/14,728) but lower rates of traumatic stress (overall 14.6%, 3,256/22,320) compared with the general population (overall 24.8%, 16,825/67,773 for anxiety and 20.8%, 2,163/10,380 for traumatic stress). The higher anxiety in healthcare workers could be related to the high infectivity of COVID-19 with the resultant sharp rise in infected cases and mortality seen and managed by frontline healthcare workers, especially at the start of the pandemic when little was known about its natural history.(155) The relatively lower rate of traumatic stress in healthcare workers could be related to the better preparedness in terms of protective equipment and strict infection control measures within healthcare facilities in managing the outbreak.(49) Compared with past epidemics such as the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) outbreaks, the rates of anxiety (up to 96% in MERS vs. overall 33% in COVID-19)(15,156) and traumatic stress (25.5% in SARS vs. overall 14.6% in COVID-19)(19,157) in healthcare workers were lower during the current pandemic. This likely reflects progressive improvements in infection control measures and infrastructure that have translated to better psychological well-being since earlier outbreaks such as SARS, especially in Asia, which bore the brunt of the infection and fatality.(158) Of note, there were relatively substantial psychological responses within subgroups, such as among those with pre-existing physical and psychiatric illnesses (overall anxiety 26%–49.5%, overall depression 18.6%–42.6% and overall traumatic stress symptoms of 12.7%–31.6%).(5,6,8,20,22,44,50-65) Although less studied, psychological sequelae were noted in younger individuals such as children and youths (overall anxiety 31.0%, overall depression 34.2% and traumatic stress symptoms 11%),(23-27,39,41,66-69) individuals who were quarantined (overall anxiety 28.2%, overall depression 14.7%, overall traumatic stress symptoms 2.7%)(24,25,28-30,67,70,71) and patients who were infected with COVID-19 (overall anxiety 32.2%, overall depression 39.9%, overall traumatic stress symptoms 80.7%).(9,12,28,31,72,73) This highlights the need for active monitoring, early detection and attention to these psychological issues within the different subpopulations.

Practical implications include individual and institutional measures to address and ameliorate the psychological impact. At the institutional and governance level, useful considerations are: commitment for the long haul; timely communication about the local epidemic curve; enabling access to timely, accurate COVID-19-related information and resources for psychological help among the population and subgroups; constant review of implemented measures; and early identification of those in need of psychological help.(2) At the individual level, an emphasis on self-care and a healthy balance between work and rest, nutrition, sleep, and social connectivity(2) are crucial.

Several limitations were observed in this study. First, timely publication of appropriate reports from other affected countries worldwide would provide a better representation of the nature and scale of the psychological impact. Second, examination of the psychological sequelae in specific subgroups such as the elderly, those who have recovered from COVID-19, and patients with multiple physical and psychiatric comorbidities is warranted. Third, some specific psychosocial responses are less examined but have been observed in past infectious disease outbreaks, including stigmatisation, grief and positive growth. Fourth, a better understanding of how digitalisation has helped or hindered psychological well-being would inform measures to enhance psychological support. Fifth, there is a need to consider longitudinal studies to ascertain the longer-term psychological sequelae within the different subgroups.

In conclusion, extant studies at this juncture suggest that there are substantial COVID-19 psychological sequelae among healthcare workers and the general population, including vulnerable subgroups. Further work is needed to better understand the psychological impact on under-examined subgroups, especially prospectively, in order to optimise psychological support for them globally.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

The Appendix is available online at https://doi.org/10.11622/smedj.2020111.

REFERENCES

- 1.Worldometer. COVID-19 coronavirus pandemic. [Accessed June 15, 2020]. Available at: https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/

- 2.Chew QH, Wei KC, Vasoo S, Chua HC, Sim K. Narrative synthesis of psychological and coping responses towards emerging infectious disease outbreaks in the general population:practical considerations for the COVID-19 pandemic. Singapore Med J. 2020 Apr 3; doi: 10.11622/smedj.2020046. https://doi.org/10.11622/smedj.2020046. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sim K, Chong PN, Chan YH, Soon WS. Severe acute respiratory syndrome-related psychiatric and posttraumatic morbidities and coping responses in medical staff within a primary health care setting in Singapore. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65:1120–7. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v65n0815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shokraneh F. Keeping up with studies on COVID-19:systematic search strategies and resources. BMJ. 2020;369:m1601. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hao F, Tan W, Jiang L, et al. Do psychiatric patients experience more psychiatric symptoms during COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown?A case-control study with service and research implications for immunopsychiatry. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;87:100–6. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Almandoz JP, Xie L, Schellinger JN, et al. Impact of COVID-19 stay-at-home orders on weight-related behaviors among patients with obesity. Clin Obes. 2020 Jun 9; doi: 10.1111/cob.12386. https://doi.org/10.1111/cob.12386. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cao J, Wei J, Zhu H, et al. A study of basic needs and psychological wellbeing of medical workers in the fever clinic of a tertiary general hospital in Beijing during the COVID-19 outbreak. Psychother Psychosom. 2020 Mar 30; doi: 10.1159/000507453. https://doi.org/10.1159/000507453. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rohde C, Hougaard Jefsen O, Nørremark B, Aalkjær Danielsen A, Dinesen Østergaard S. Psychiatric symptoms related to the COVID-19 pandemic. Acta Neuropsychiatr. 2020 May 21; doi: 10.1017/neu.2020.24. https://doi.org/10.1017/neu.2020.24. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bo HX, Li W, Yang Y, et al. Posttraumatic stress symptoms and attitude toward crisis mental health services among clinically stable patients with COVID-19 in China. Psychol Med. 2020 Mar 27; doi: 10.1017/S0033291720000999. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291720000999. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Balkhi F, Nasir A, Zehra A, Riaz R. Psychological and behavioral response to the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. Cureus. 2020;12:e7923. doi: 10.7759/cureus.7923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee SA, Jobe MC, Mathis AA. Mental health characteristics associated with dysfunctional coronavirus anxiety. Psychol Med. 2020 Apr 16; doi: 10.1017/S003329172000121X. https://doi.org/10.1017/S003329172000121X. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guo Q, Zheng Y, Shi J, et al. Immediate psychological distress in quarantined patients with COVID-19 and its association with peripheral inflammation:a mixed-method study. Brain Behav Immun. 2020 May 19; doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.038. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.038. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fekih-Romdhane F, Ghrissi F, Abbassi B, Cherif W, Cheour M. Prevalence and predictors of PTSD during the COVID-19 pandemic:findings from a Tunisian community sample. Psychiatry Res. 2020 May 27; doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113131. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chew NWS, Lee GKH, Tan BYQ, et al. A multinational, multicentre study on the psychological outcomes and associated physical symptoms amongst healthcare workers during COVID-19 outbreak. Brain Behav Immun. 2020 Apr 21; doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.049. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.049. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Choudhury T, Debski M, Wiper A, et al. COVID-19 pandemic:looking after the mental health of our healthcare workers. J Occup Environ Med. 2020 May 12; doi: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000001907. https://doi.org/10.1097/JOM.0000000000001907. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tan BYQ, Chew NWS, Lee GKH, et al. Psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on health care workers in Singapore. Ann Intern Med. 2020 Apr 6; doi: 10.7326/M20-1083. https://doi.org/10.7326/m20-1083. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Elbay RY, Kurtulmuş A, Arpacioğlu S, Karadere E. Depression, anxiety, stress levels of physicians and associated factors in COVID-19 pandemics. Psychiatry Res. 2020 May 27; doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113130. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yin Q, Sun Z, Liu T, et al. Posttraumatic stress symptoms of health care workers during the corona virus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Clin Psychol Psychother. 2020;27:384–95. doi: 10.1002/cpp.2477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rossi R, Socci V, Pacitti F, et al. Mental health outcomes among frontline and second-line health care workers during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic in Italy. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e2010185. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.10185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Forlenza OV, Stella F. LIM-27 Psychogeriatric Clinic HCFMUSP. Impact of SARS-CoV-2 pandemic on mental health in the elderly:perspective from a psychogeriatric clinic at a tertiary hospital in Sao Paulo, Brazil. Int Psychogeriatr. 2020 Jun 11; doi: 10.1017/S1041610220001180. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610220001180. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yuan R, Xu QH, Xia CC, et al. Psychological status of parents of hospitalized children during the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Psychiatry Res. 2020;288:112953. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ng DWL, Chan FHF, Barry TJ, et al. Psychological distress during the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic among cancer survivors and healthy controls. Psychooncology. 2020 Jun 4; doi: 10.1002/pon.5437. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.5437. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cao W, Fang Z, Hou G, et al. The psychological impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on college students in China. Psychiatry Res. 2020;287:112934. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang Y, Zhang H, Ma X, Di Q. Mental health problems during the COVID-19 pandemics and the mitigation effects of exercise:a longitudinal study of college students in China. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:3722. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17103722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tang W, Hu T, Hu B, et al. Prevalence and correlates of PTSD and depressive symptoms one month after the outbreak of the COVID-19 epidemic in a sample of home-quarantined Chinese university students. J Affect Disord. 2020 May 13; doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.05.009. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.05.009. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Odriozola-González P, Planchuelo-Gómez Á, Irurtia MJ, de Luis-García R. Psychological effects of the COVID-19 outbreak and lockdown among students and workers of a Spanish university. Psychiatr Res. 2020 May 19; doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113108. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu CH, Zhang E, Wong GTF, Hyun S, Hahm HC. Factors associated with depression, anxiety, and PTSD symptomatology during the COVID-19 pandemic:clinical implications for U.S. young adult mental health. Psychiatry Res. 2020 Jun 1; doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113172. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang J, Lu H, Zeng H, et al. The differential psychological distress of populations affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. Brain Behav Immun. 2020 Apr 15; doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.031. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.031. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Madani A, Boutebal SE, Bryant CR. The psychological impact of confinement linked to the coronavirus epidemic COVID-19 in Algeria. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:3604. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17103604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lei L, Huang X, Zhang S, et al. Comparison of prevalence and associated factors of anxiety and depression among people affected by versus people unaffected by quarantine during the COVID-19 epidemic in Southwestern China. Med Sci Monit. 2020;26:e924609. doi: 10.12659/MSM.924609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Qi R, Chen W, Liu S, et al. Psychological morbidities and fatigue in patients with confirmed COVID-19 during disease outbreak:prevalence and associated biopsychosocial risk factors. medRxiv. 2020 May 11; https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.05.08.20031666. Preprint. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wu K, Wei X. Analysis of psychological and sleep status and exercise rehabilitation of front-line clinical staff in the fight against COVID-19 in China. Med Sci Monit Basic Res. 2020;26:e924085. doi: 10.12659/MSMBR.924085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xu J, Xu QH, Wang CM, Wang J. Psychological status of surgical staff during the COVID-19 outbreak. Psychiatry Res. 2020;288:112955. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang WR, Wang K, Yin L, et al. Mental health and psychosocial problems of medical health workers during the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Psychother Psychosom. 2020 Apr 9; doi: 10.1159/000507639. https://doi.org/10.1159/000507639. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yang H, Ma J. How an epidemic outbreak impacts happiness:factors that worsen (vsprotect) emotional well-being during the coronavirus pandemic. Psychiatry Res. 2020 Apr 30; doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113045. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113045. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Abdessater M, Rouprêt M, Misrai V, et al. COVID-19 outbreak situation and its psychological impact among surgeons in training in France. World J Urol. 2020 Apr 24; doi: 10.1007/s00345-020-03207-x. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00345-020-03207-x. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lwin MO, Lu J, Sheldenkar A, et al. Global sentiments surrounding the COVID-19 pandemic on Twitter:analysis of Twitter trends. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2020;6:e19447. doi: 10.2196/19447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Teufel M, Schweda A, Dörrie N, et al. Not all world leaders use Twitter in response to the COVID-19 pandemic:impact of the way of Angela Merkel on psychological distress, behaviour and risk perception. J Public Health (Oxf) 2020 May 12; doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdaa060. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdaa060. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhou SJ, Zhang LG, Wang LL, et al. Prevalence and socio-demographic correlates of psychological health problems in Chinese adolescents during the outbreak of COVID-19. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2020;29:749–58. doi: 10.1007/s00787-020-01541-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gao J, Zheng P, Jia Y, et al. Mental health problems and social media exposure during COVID-19 outbreak. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0231924. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0231924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li Y, Wang Y, Jiang J, et al. Psychological distress among health professional students during the COVID-19 outbreak. Psychol Med. 2020 May 11; doi: 10.1017/S0033291720001555. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291720001555. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang C, Pan R, Wan X, et al. Immediate psychological responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) epidemic among the general population in China. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:1729. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17051729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Meng H, Xu Y, Dai J, et al. Analyze the psychological impact of COVID-19 among the elderly population in China and make corresponding suggestions. Psychiatry Res. 2020 Apr 11; doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112983. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112983. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jiang H, Su H, Zhang C, et al. Challenges of methadone maintenance treatment during the COVID-19 epidemic in China:policy and service recommendations. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2020;35:136–7. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2020.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li J, Yang Z, Qiu H, et al. Anxiety and depression among general population in China at the peak of the COVID-19 epidemic. World Psychiatry. 2020;19:249–50. doi: 10.1002/wps.20758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mamun MA, Ullah I. COVID-19 suicides in Pakistan, dying off not COVID-19 fear but poverty?- The forthcoming economic challenges for a developing country. Brain Behav Immun. 2020 May 11; doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.028. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.028. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang C, Pan R, Wan X, et al. A longitudinal study on the mental health of general population during the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Brain Behav Immun. 2020 Apr 13; doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.028. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.028. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhou Y, Zhou Y, Song Y, et al. Tackling the mental health burden of frontline healthcare staff in the COVID-19 pandemic:China's experiences. Psychol Med. 2020 May 13; doi: 10.1017/S0033291720001622. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291720001622. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cai H, Tu B, Ma J, et al. Psychological impact and coping strategies of frontline medical staff in Hunan between January and March 2020 during the outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID19) in Hubei, China. Med Sci Monit. 2020;26:e924171. doi: 10.12659/MSM.924171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Brown TS, Bedard NA, Rojas EO, et al. The effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on electively scheduled hip and knee arthroplasty patients in the United States. J Arthroplasty. 2020 Apr 22; doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2020.04.052. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2020.04.052. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Colizzi M, Sironi E, Antonini F, et al. Psychosocial and behavioral impact of COVID-19 in autism spectrum disorder:an online parent survey. Brain Sci. 2020;10:E341. doi: 10.3390/brainsci10060341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Colle R, Ait Tayeb AEK, de Larminat D, et al. Short-term acceptability by patients and psychiatrists of the turn to psychiatric teleconsultation in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiat Clin Neurosci. 2020 Jun 8; doi: 10.1111/pcn.13081. https://doi.org/10.1111/pcn.13081. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Frank A, Fatke B, Frank W, Förstl H, Hölzle P. Depression, dependence and prices of the COVID-19 crisis. Brain Behav Immun. 2020 Apr 29; doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.068. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.068. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gupta MA. Spontaneous reporting of onset of disturbing dreams and nightmares related to early life traumatic experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic by patients with posttraumatic stress disorder in remission. J Clin Sleep Med. 2020 May 12; doi: 10.5664/jcsm.8562. https://doi.org/10.5664/jcsm.8562. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hao X, Zhou D, Li Z, et al. Severe psychological distress among patients with epilepsy during the COVID-19 outbreak in southwest China. Epilepsia. 2020;61:1166–73. doi: 10.1111/epi.16544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Plunkett R, Costello S, McGovern M, McDonald C, Hallahan B. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on patients with pre-existing anxiety disorders attending secondary care. Ir J Psychol Med. 2020 Jun 8; doi: 10.1017/ipm.2020.75. https://doi.org/10.1017/ipm.2020.75. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Prasad S, Holla VV, Neeraja K, et al. Parkinson's disease and COVID-19:perceptions and implications in patients and caregivers. Mov Disord. 2020;35:912–4. doi: 10.1002/mds.28088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rivetti N, Barruscotti S. Management of telogen effluvium during the COVID-19 emergency:psychological implications. Dermatol Ther. 2020 May 22; doi: 10.1111/dth.13648. https://doi.org/10.1111/dth.13648. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shalash A, Roushdy T, Essam M, et al. Mental health, physical activity, and quality of life in Parkinson's disease during COVID-19 pandemic. Mov Disord. 2020 May 19; doi: 10.1002/mds.28134. https://doi.org/10.1002/mds.28134. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Siniscalchi M, Zingone F, Savarino EV, D'Odorico A, Ciacci C. COVID-19 pandemic perception in adults with celiac disease:an impulse to implement the use of telemedicine. Digest Liver Dis. 2020 May 16; doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2020.05.014. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dld.2020.05.014. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sun S, Hou J, Chen Y, et al. Challenges to HIV care and psychological health during the COVID-19 pandemic among people living with HIV in China. AIDS Behav. 2020 May 7; doi: 10.1007/s10461-020-02903-4. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-020-02903-4. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Termorshuizen JD, Watson HJ, Thornton LM, et al. Early impact of COVID-19 on individuals with eating disorders:a survey of ~1000 individuals in the United States and the Netherlands. medRxiv. 2020 May 29; doi: 10.1002/eat.23353. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.05.28.20116301. Preprint. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Umucu E, Lee B. Examining the impact of COVID-19 on stress and coping strategies in individuals with disabilities and chronic conditions. Rehabil Psychol. 2020 May 14; doi: 10.1037/rep0000328. https://doi.org/10.1037/rep0000328. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhao Y, Wei L, Liu B, Du D. Management of transplant patients outside hospital during COVID-19 epidemic:a Chinese experience. Transpl Infect Dis. 2020 May 14; doi: 10.1111/tid.13327. https://doi.org/10.1111/tid.13327. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhou J, Liu L, Xue P, Yang X, Tang X. Mental health response to the COVID-19 outbreak in China. Am J Psychiatry. 2020 May 7; doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2020.20030304. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2020.20030304. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ma H, Miller C. Trapped in a double bind:Chinese overseas student anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic. Health Commun. 2020 Jun 12; doi: 10.1080/10410236.2020.1775439. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2020.1775439. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Saurabh K, Ranjan S. Compliance and psychological impact of quarantine in children and adolescents due to COVID-19 pandemic. Indian J Pediatr. 2020 May 29; doi: 10.1007/s12098-020-03347-3. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12098-020-03347-3. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Xie X, Xue Q, Zhou Y, et al. Mental health status among children in home confinement during the coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak in Hubei Province, China. JAMA Pediatr. 2020 Apr 24; doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.1619. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.1619. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Liang L, Ren H, Cao R, et al. The effect of COVID-19 on youth mental health. Psychiatr Q. 2020 Apr 21; doi: 10.1007/s11126-020-09744-3. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11126-020-09744-3. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Xue Z, Lin L, Zhang S, et al. Sleep problems and medical isolation during the SARS-CoV-2 outbreak. Sleep Med. 2020;70:112–5. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2020.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zhu S, Wu Y, Zhu CY, et al. The immediate mental health impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic among people with or without quarantine managements. Brain Behav Immun. 2020 Apr 18; doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.045. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.045. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zarghami A, Farjam M, Fakhraei B, Hashemzadeh K, Yazdanpanah MH. A report of the telepsychiatric evaluation of SARS-CoV-2 patients. Telemed J E Health. 2020 Jun 11; doi: 10.1089/tmj.2020.0125. https://doi.org/10.1089/tmj.2020.0125. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zhou L, Xie RH, Yang X, et al. Feasibility and preliminary results of effectiveness of social media-based intervention on the psychological well-being of suspected COVID-19 cases during quarantine. Can J Psychiatry. 2020 Jun 2; doi: 10.1177/0706743720932041. https://doi.org/10.1177/0706743720932041. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ahmad AR, Murad HR. The impact of social media on panic during the COVID-19 pandemic in Iraqi Kurdistan:online questionnaire study. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22:e19556. doi: 10.2196/19556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ahmed MA, Jouhar R, Ahmed N, et al. Fear and practice modifications among dentists to combat novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:2821. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17082821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Md Hazir A, Oli A, Zhou A, et al. Epidemic of COVID-19 in China and associated psychological problems. Asian J Psychiatr. 2020 Apr 14; doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102092. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102092. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Amerio A, Bianchi D, Santi F, et al. COVID-19 pandemic impact on mental health:a web-based cross-sectional survey on a sample of Italian general practitioners. Acta Biomed. 2020;91:83–8. doi: 10.23750/abm.v91i2.9619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Barbato M, Thomas J. Far from the eyes, close to the heart:psychological impact of COVID-19 in a sample of Italian foreign workers. Psychiatr Res. 2020 May 19; doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113113. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Barello S, Palamenghi L, Graffigna G. Burnout and somatic symptoms among frontline healthcare professionals at the peak of the Italian COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatr Res. 2020 May 27; doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113129. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Büntzel J, Klein M, Keinki C, et al. Oncology services in corona times:a flash interview among German cancer patients and their physicians. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2020 May 15; doi: 10.1007/s00432-020-03249-z. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00432-020-03249-z. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Buonsenso D, Cinicola B, Raffaelli F, Sollena P, Iodice F. Social consequences of COVID-19 in a low resource setting in Sierra Leone, West Africa. Int J Infect Dis. 2020 Jun 1; doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.05.104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2020.05.104. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Cai W, Lian B, Song X, et al. A cross-sectional study on mental health among health care workers during the outbreak of corona virus disease 2019. Asian J Psychiatr. 2020 Apr 24; doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102111. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Chen Y, Zhou H, Zhou Y, Zhou F. Prevalence of self-reported depression and anxiety among pediatric medical staff members during the COVID-19 outbreak in Guiyang, China. Psychiatry Res. 2020;288:113005. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Choi EPH, Hui BPH, Wan EYF. Depression and anxiety in Hong Kong during COVID-19. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:3740. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17103740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Civantos AM, Byrnes Y, Chang C, et al. Mental health among otolaryngology resident and attending physicians during the COVID-19 pandemic:national study. Head Neck. 2020 Jun 4; doi: 10.1002/hed.26292. https://doi.org/10.1002/hed.26292. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Consolo U, Bellini P, Bencivenni D, Iani C, Checchi V. Epidemiological aspects and psychological reactions to COVID-19 of dental practitioners in the Northern Italy districts of Modena and Reggio Emilia. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:3459. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17103459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Dixit A, Marthoenis M, Arafat SMY, Sharma P, Kar SK. Binge watching behavior during COVID 19 pandemic:a cross-sectional, cross-national online survey. Psychiatry Res. 2020 May 13; doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113089. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113089. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Dong ZQ, Ma J, Hao YN, et al. The social psychological impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on medical staff in China:a cross-sectional study. Eur Psychiatry. 2020 Jun 1; doi: 10.1192/j.eurpsy.2020.59. https://doi.org/10.1192/j.eurpsy.2020.59. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Du J, Dong L, Wang T, et al. Psychological symptoms among frontline healthcare workers during COVID-19 outbreak in Wuhan. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2020 Apr 3; doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2020.03.011. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2020.03.011. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Durankuş F, Aksu E. Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on anxiety and depressive symptoms in pregnant women:a preliminary study. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2020 May 18; doi: 10.1080/14767058.2020.1763946. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767058.2020.1763946. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.El-Zoghby SM, Soltan EM, Salama HM. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health and social support among adult Egyptians. J Community Health. 2020 May 28; doi: 10.1007/s10900-020-00853-5. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-020-00853-5. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Forte G, Favieri F, Tambelli R, Casagrande M. COVID-19 pandemic in the Italian population:validation of a post-traumatic stress disorder questionnaire and prevalence of PTSD symptomatology. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:E4151. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17114151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Forte G, Favieri F, Tambelli R, Casagrande M. The enemy which sealed the world:effects of COVID-19 diffusion on the psychological state of the Italian population. J Clin Med. 2020;9:E1802. doi: 10.3390/jcm9061802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Gómez-Salgado J, Andrés-Villas M, Domínguez-Salas S, Díaz-Milanés D, Ruiz-Frutos C. Related health factors of psychological distress during the COVID-19 pandemic in Spain. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:E3947. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17113947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.González-Sanguino C, Ausín B, Castellanos MÁ, et al. Mental health consequences during the initial stage of the 2020 coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19) in Spain. Brain Behav Immun. 2020 May 13; doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.040. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.040. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Hou T, Zhang T, Cai W, et al. Social support and mental health among health care workers during coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak:a moderated mediation model. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0233831. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0233831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Huang Y, Zhao N. Mental health burden for the public affected by the COVID-19 outbreak in China:who will be the high-risk group? Psychol Health Med. 2020 Apr 14; doi: 10.1080/13548506.2020.1754438. https://doi.org/10.1080/13548506.2020.1754438. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Kang L, Ma S, Chen M, et al. Impact on mental health and perceptions of psychological care among medical and nursing staff in Wuhan during the 2019 novel coronavirus disease outbreak:a cross-sectional study. Brain Behav Immun. 2020 Mar 30; doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.03.028. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2020.03.028. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Khanna RC, Honavar SG, Metla AL, Bhattacharya A, Maulik PK. Psychological impact of COVID-19 on ophthalmologists-in-training and practising ophthalmologists in India. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2020;68:994–8. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_1458_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Killgore WDS, Cloonan SA, Taylor EC, Dailey NS. Loneliness:a signature mental health concern in the era of COVID-19. Psychiatry Res. 2020 May 23; doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113117. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Killgore WDS, Cloonan SA, Taylor EC, et al. Suicidal ideation during the COVID-19 pandemic:the role of insomnia. Psychiatry Res. 2020 May 27; doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113134. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Lai J, Ma S, Wang Y, et al. Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e203976. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.3976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Lee M, You M. Psychological and behavioral responses in South Korea during the early stages of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:2977. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17092977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Li G, Miao J, Wang H, et al. Psychological impact on women health workers involved in COVID-19 outbreak in Wuhan:a cross-sectional study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2020 May 4; doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2020-323134. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp-2020-323134. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Li Y, Qin Q, Sun Q, et al. Insomnia and psychological reactions during the COVID-19 outbreak in China. J Clin Sleep Med. 2020 Apr 30; doi: 10.5664/jcsm.8524. https://doi.org/10.5664/jcsm.8524. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Li X, Yu H, Bian G, et al. Prevalence, risk factors, and clinical correlates of insomnia in volunteer and at home medical staff during the COVID-19. Brain Behav Immun. 2020 May 5; doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.008. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.008. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Liu CY, Yang YZ, Zhang XM, et al. The prevalence and influencing factors in anxiety in medical workers fighting COVID-19 in China:a cross-sectional survey. Epidemiol Infect. 2020;148:e98. doi: 10.1017/S0950268820001107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Liu X, Luo WT, Li Y, et al. Psychological status and behavior changes of the public during the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Infect Dis Poverty. 2020;9:58. doi: 10.1186/s40249-020-00678-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Liu N, Zhang F, Wei C, et al. Prevalence and predictors of PTSS during COVID-19 outbreak in China hardest-hit areas:gender differences matter. Psychiatry Res. 2020;287:112921. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Mazza C, Ricci E, Biondi S, et al. A nationwide survey of psychological distress among Italian people during the COVID-19 pandemic:immediate psychological responses and associated factors. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:3165. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17093165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Mo Y, Deng L, Zhang L, et al. Work stress among Chinese nurses to support Wuhan in fighting against COVID-19 epidemic. J Nurs Manag. 2020 Apr 7; doi: 10.1111/jonm.13014. https://doi.org/10.1111/jonm.13014. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Moccia L, Janiri D, Pepe M, et al. Affective temperament, attachment style, and the psychological impact of the COVID-19 outbreak:an early report on the Italian general population. Brain Behav Immun. 2020 Apr 20; doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.048. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.048. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Morgantini LA, Naha U, Wang H, et al. Factors contributing to healthcare professional burnout during the COVID-19 pandemic:a rapid turnaround global survey. medRxiv. 2020 May 22; doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0238217. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.05.17.20101915. Preprint. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Ni MY, Yang L, Leung CMC, et al. Mental health, risk factors, and social media use during the COVID-19 epidemic and cordon sanitaire among the community and health professionals in Wuhan, China:cross-sectional survey. JMIR Ment Health. 2020;7:e19009. doi: 10.2196/19009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Özdin S, Özdin ŞB. Levels and predictors of anxiety, depression and health anxiety during COVID-19 pandemic in Turkish society:the importance of gender. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2020 May 8; doi: 10.1177/0020764020927051. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764020927051. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Padala PR, Jendro AM, Gauss CH, et al. Participant and caregiver perspectives on clinical research during COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68:E14–8. doi: 10.1111/jgs.16500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Pedrozo-Pupo JC, Pedrozo-Cortés MJ, Campo-Arias A. Perceived stress associated with COVID-19 epidemic in Colombia:an online survey. Cad Saude Publica. 2020;36:e00090520. doi: 10.1590/0102-311x00090520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Podder I, Agarwal K, Datta S. Comparative analysis of perceived stress in dermatologists and other physicians during home-quarantine and COVID-19 pandemic with exploration of possible risk factors- a web-based cross-sectional study from Eastern India. Dermatol Ther. 2020 Jun 7; doi: 10.1111/dth.13788. https://doi.org/10.1111/dth.13788. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Qiu J, Shen B, Zhao M, et al. A nationwide survey of psychological distress among Chinese people in the COVID-19 epidemic:implications and policy recommendations. Gen Psychiatr. 2020;33:e100213. doi: 10.1136/gpsych-2020-100213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Ren Y, Zhou Y, Qian W, et al. Letter to the Editor “A longitudinal study on the mental health of general population during the COVID-19 epidemic in China”. Brain Behav Immun. 2020 May 6; doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.004. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.004. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Roy D, Tripathy S, Kar SK, et al. Study of knowledge, attitude, anxiety &perceived mental healthcare need in Indian population during COVID-19 pandemic. Asian J Psychiatr. Apr 8; doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102083. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102083. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Saccone G, Florio A, Aiello F, et al. Psychological impact of COVID-19 in pregnant women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020 May 7; doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2020.05.003. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2020.05.003. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Sahu D, Agrawal T, Rathod V, Bagaria V. Impact of COVID 19 lockdown on orthopaedic surgeons in India:a survey. J Clin Orthop Trauma. 2020 May 12; doi: 10.1016/j.jcot.2020.05.007. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcot.2020.05.007. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Shacham M, Hamama-Raz Y, Kolerman R, et al. COVID-19 factors and psychological factors associated with elevated psychological distress among dentists and dental hygienists in Israel. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:2900. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17082900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Shapiro E, Levine L, Kay A. Mental health stressors in Israel during the coronavirus pandemic. Psychol Trauma. 2020 Jun 11; doi: 10.1037/tra0000864. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000864. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Shen X, Zou X, Zhong X, Yan J, Li L. Psychological stress of ICU nurses in the time of COVID-19. Crit Care. 2020;24:200. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-02926-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Simpson SA, Dumas A, McDowell AK, Westmoreland P. Novel coronavirus and related public health interventions are negatively impacting mental health services. Psychosomatics. 2020 Apr 9; doi: 10.1016/j.psym.2020.04.004. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psym.2020.04.004. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Somma A, Gialdi G, Krueger RF, et al. Dysfunctional personality features, non-scientifically supported causal beliefs, and emotional problems during the first month of the COVID-19 pandemic in Italy. Pers Individ Differ. 2020;165:110139. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2020.110139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Sønderskov KM, Dinesen PT, Santini ZI, Østergaard SD. The depressive state of Denmark during the COVID-19 pandemic. Acta Neuropsychiatr. 2020 Apr 22; doi: 10.1017/neu.2020.15. https://doi.org/10.1017/neu.2020.15. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Song X, Fu W, Liu X, et al. Mental health status of medical staff in emergency departments during the coronavirus disease 2019 epidemic in China. Brain Behav Immun. 2020 Jun 5; doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.06.002. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2020.06.002. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Suleiman A, Bsisu I, Guzu H, et al. Preparedness of frontline doctors in Jordan healthcare facilities to COVID-19 outbreak. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:3181. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17093181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Sun D, Yang D, Li Y, et al. Psychological impact of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) outbreak in health workers in China. Epidemiol Infect. 2020;148:e96. doi: 10.1017/S0950268820001090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Sun Y, Li Y, Bao Y, et al. Brief report:increased addictive internet and substance use behavior during the COVID-19 pandemic in China. Am J Addict. 2020;29:268–70. doi: 10.1111/ajad.13066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Suzuki S. Psychological status of postpartum women under the COVID-19 pandemic in Japan. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2020 May 18; doi: 10.1080/14767058.2020.1763949. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767058.2020.1763949. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Tan W, Hao F, McIntyre RS, et al. Is returning to work during the COVID-19 pandemic stressful?A study on immediate mental health status and psychoneuroimmunity prevention measures of Chinese workforce. Brain Behav Immun. 2020 Apr 23; doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.055. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.055. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Taylor S, Landry CA, Paluszek MM, et al. Development and initial validation of the COVID stress scales. J Anxiety Disord. 2020;72:102232. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2020.102232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Temsah MH, Al-Sohime F, Alamro N, et al. The psychological impact of COVID-19 pandemic on health care workers in a MERS-CoV endemic country. J Infect Public Health. 2020;13:877–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2020.05.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Tian F, Li H, Tian S, et al. Psychological symptoms of ordinary Chinese citizens based on SCL-90 during the level I emergency response to COVID-19. Psychiatry Res. 2020;288:112992. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Uvais N, Nalakath M, Shihabudheen P, et al. Psychological distress during COVID-19 among Malayalam-speaking Indian expats in the middle east. Indian J Public Health. 2020;64(Suppl):S249–50. doi: 10.4103/ijph.IJPH_475_20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.van Agteren J, Bartholomaeus J, Fassnacht DB, et al. Using internet-based psychological measurement to capture the deteriorating community mental health profile during COVID-19:observational study. JMIR Ment Health. 2020;7:e20696. doi: 10.2196/20696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Varshney M, Parel JT, Raizada N, Sarin SK. Initial psychological impact of COVID-19 and its correlates in Indian community:an online (FEEL-COVID) survey. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0233874. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0233874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Voitsidis P, Gliatas I, Bairachtari V, et al. Insomnia during the COVID-19 pandemic in a Greek population. Psychiatry Res. 2020 May 12; doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113076. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113076. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Wang S, Xie L, Xu Y, et al. Sleep disturbances among medical workers during the outbreak of COVID-2019. Occup Med (Lond) 2020 May 6; doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqaa074. https://doi.org/10.1093/occmed/kqaa074. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Wang Y, Di Y, Ye J, Wei W. Study on the public psychological states and its related factors during the outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in some regions of China. Psychol Health Med. 2020 Mar 30; doi: 10.1080/13548506.2020.1746817. https://doi.org/10.1080/13548506.2020.1746817. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Wu Y, Zhang C, Liu H, et al. Perinatal depressive and anxiety symptoms of pregnant women along with COVID-19 outbreak in China. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020 May 10; doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2020.05.009. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2020.05.009. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Wu C, Hu X, Song J, et al. Mental health status and related influencing factors of COVID-19 survivors in Wuhan, China. Clin Transl Med. 2020 Jun 5; doi: 10.1002/ctm2.52. https://doi.org/10.1002/ctm2.52. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Xing J, Sun N, Xu J, Geng S, Li Y. Study of the mental health status of medical personnel dealing with new coronavirus pneumonia. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0233145. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0233145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Yang S, Kwak SG, Ko EJ, Chang MC. The mental health burden of the COVID-19 pandemic on physical therapists. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:3723. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17103723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Yassa M, Birol P, Yirmibes C, et al. Near-term pregnant women's attitude toward, concern about and knowledge of the COVID-19 pandemic. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2020 May 19; doi: 10.1080/14767058.2020.1763947. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767058.2020.1763947. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Zanardo V, Manghina V, Giliberti L, et al. Psychological impact of COVID-19 quarantine measures in northeastern Italy on mothers in the immediate postpartum period. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2020 May 31; doi: 10.1002/ijgo.13249. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijgo.13249. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Zhang Y, Ma ZF. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health and quality of life among local residents in Liaoning Province, China:a cross-sectional study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:2381. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17072381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Zhang SX, Liu J, Afshar Jahanshahi A, et al. At the height of the storm:healthcare staff's health conditions and job satisfaction and their associated predictors during the epidemic peak of COVID-19. Brain Behav Immun. 2020 May 5; doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.010. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.010. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Zhang C, Yang L, Liu S, et al. Survey of insomnia and related social psychological factors among medical staff involved in the 2019 novel coronavirus disease outbreak. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:306. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Zhao X, Lan M, Li H, Yang J. Perceived stress and sleep quality among the non-diseased general public in China during the 2019 coronavirus disease:a moderated mediation model. Sleep Med. 2020 May 21; doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2020.05.021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2020.05.021. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Zhang X, Tan Y, Ling Y, et al. Viral and host factors related to the clinical outcome of COVID-19. Nature. 2020 May 20; doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2355-0. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2355-0. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Khalid I, Khalid TJ, Qabajah MR, Barnard AG, Qushmaq IA. Healthcare workers emotions, perceived stressors and coping strategies during a MERS-CoV outbreak. Clin Med Res. 2016;14:7–14. doi: 10.3121/cmr.2016.1303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Maunder R. The experience of the 2003 SARS outbreak as a traumatic stress among frontline healthcare workers in Toronto:lessons learned. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2004;359:1117–25. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2004.1483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Shannon GW, Willoughby J. Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) in Asia:a medical geographic perspective. Eurasian Geogr Econ. 2004;45:359–81. [Google Scholar]