Abstract

Objectives

A majority of women and families wish that their babies be breastfed. However, too many still receive insufficient or inappropriate initial care from health professionals (HPs) who have limited breastfeeding (BF) competencies. We investigated barriers and potential solutions to improve the undergraduate training programs for various HPs.

Methods

Focus groups were carried out in three universities in Quebec and one in Ontario (Canada), with 30 faculty and program directors from medicine, midwifery, nursing, nutrition, and pharmacy. Discussions were subjected to thematic content analysis, before being validated in a strategic planning workshop with 48 participants from the same disciplines, plus dentistry and chiropractic.

Findings

Substantive improvements of undergraduate training programs for BF could be obtained by addressing challenges related to the insufficient, or lack of, (i) interactions among various HPs, (ii) opportunities for practical learning, (iii) specific standards to guide course content, (iv) real-life experience with counselling, and (v) understanding of the influence of attitudes on professional practice. Several potential solutions were proposed and validated. The re-interpretation of the results in light of various literature led to an emerging framework that takes a systems perspective for enhancing the education of HPs on BF.

Conclusions

To improve the education of HPs so as to enable them to provide relevant support for future mothers, mothers and their families, solutions need to be carried out to address challenges in the health system, the education system as well as regarding the curricular change process.

Abstract

Objectifs

La majorité des femmes et des familles souhaitent que leur bébé soit allaité. Toutefois, plusieurs ne reçoivent pas un soutien adéquat de la part de professionnels de la santé (PS) qui ont des compétences limitées en allaitement. Nous avons étudié les barrières et les solutions potentielles en vue de rehausser la formation initiale de divers PS.

Méthodes

Des groupes de discussion ont été organisés dans trois universités du Québec et une en Ontario (Canada) avec 30 directeurs de programmes et membres du corps professoral en médecine, pratique sage-femme, sciences infirmières, nutrition et pharmacie. Les discussions ont fait l’objet d’une analyse de contenu thématique laquelle fut ensuite validée dans un atelier de planification stratégique avec 48 participants des mêmes disciplines auxquelles se sont ajoutées dentisterie et chiropratique.

Résultats

Des améliorations substantielles des compétences en allaitement dans les programmes de formation initiale pourraient être obtenues en travaillant sur les défis associés à l’insuffisance, ou à l’absence de, (i) interactions entre les divers PS, (ii) opportunités d’apprentissages pratiques, (iii) normes spécifiques pour guider les contenus de cours, (iv) expériences réelles avec le counseling, et (v) compréhension de l’influence des attitudes sur la pratique professionnelle. La ré-interprétation des résultats à la lumière de la littérature a fait émerger un cadre conceptuel avec une perspective systémique pour guider le rehaussement de la formation en allaitement des divers PS.

Conclusions

Afin d’améliorer la formation des PS pour qu’ils/elles puissent fournir un soutien pertinent aux futures mères, aux mères et à leurs familles, des solutions visant à la fois les défis dans le système de santé, dans le système d’éducation et dans le processus de changement curriculaire doivent être mises en œuvre.

Introduction

There is strong epidemiological and biological evidence for the numerous benefits of breastfeeding (BF) for children, mothers, and society.1,2 However, globally, BF practice is still far from optimal.3 Many women stop BF, or stop BF exclusively, earlier than planned, often while still in maternity facilities.4-6 A large proportion of the problems they encounter could be prevented or easily addressed with appropriate support and information, especially during the first few days after birth.7 However, most health professionals (HPs) are not adequately prepared to provide BF women with relevant support. Indeed, it is increasingly recognized that the BF content in the curricula of various health professions is either insufficient, inadequate or both,8-11 translating into inadequate BF knowledge, attitudes and skills,12-16 and contributing to poor BF care.17,18 Hence the frequent calls for, and efforts towards, improved basic training of HPs19-23 which has been shown to improve the quality of care mothers receive.24,25

During the perinatal period, women experience numerous contacts with various HPs. Both HPs and mothers frequently refer to the BF difficulties associated with the discontinuity of care found along the continuum of services.26,27 This is in part related to HPs' limited BF education but also to the lack of understanding of their own role as well as that of their colleagues. This discontinuity of care increases the risk of delivering heterogeneous messages to expecting mothers and mothers, leading to inadequate support. HPs need to be prepared to not only carry out their own role and responsibilities, but to be cognizant of the roles and responsibilities of other HPs, so as to be able to refer mothers appropriately. When BF is not well established soon after birth, it is much more difficult for community services to provide adequate support to mothers so they can fulfill their own personal objectives. Hence, the relevance of ensuring adequate and harmonized initial training for all HPs to provide a well-prepared workforce. To testify such an importance, one of the 10 conditions for the success of breastfeeding within the global Baby Friendly Hospital Initiative (BFHI) is: “ensure that staff have sufficient knowledge, competence and skills to support breastfeeding.”28 This is also true for the equivalent of the initiative in Canada, the Baby-friendly Initiative29 that even goes beyond hospital settings.

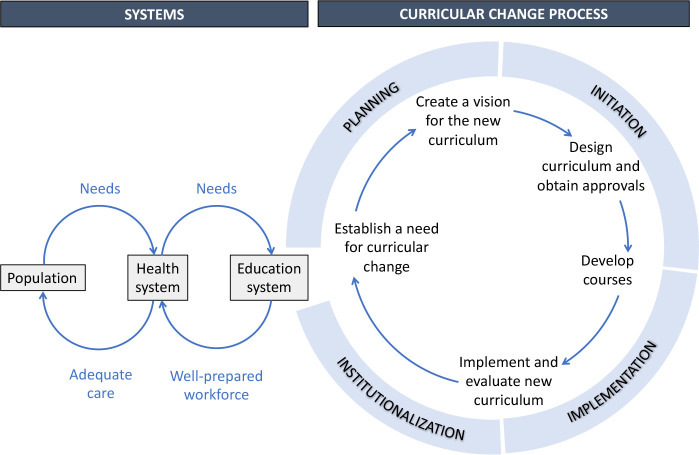

To enhance the curriculum of various health professions for more relevant support for BF, a change process is required necessitating the engagement of various actors: researchers, program directors, educators, students, and representatives from regulatory bodies. In their review on curricular change, Bland et al. acknowledge four stages for the curricular change process: planning, initiation, implementation and institutionalization.30 Our study contributes to the planning stage of the curricular change process, where “the need for change is established, a vision for change is designed, and the organizational context for change is considered.”30,p.577 Our purpose was to explore the concerns of educators, lecturers, students, and program directors regarding changes needed in curricula to enhance and better harmonize the initial training/education of HPs to enable them to better support women and families with BF. More specifically, we wanted to identify and clarify their perception as to: i) challenges related to BF education and barriers to changes needed in curricula; ii) enabling factors and potential solutions. Of note, the literature around the need to improve undergraduate curricula is itself largely founded on the needs of BF mothers. Hence our study builds on this and targets educators rather than mothers.

Box 1: Broader context.

This study was part of a broader initiative generated by the Committee on Training of the Quebec Breastfeeding Movement (known in French as “Mouvement allaitement du Québec”). Created in 2009, the Quebec Breastfeeding Movement is an independent network of individuals and organizations working towards improving BF environments. The ultimate goal of the Committee on Training was to improve and harmonize the training of HPs with regards to BF. The Committee on Training carried out a number of activities including (i) an electronic survey documenting the BF content of most training programs for HPs in Quebec (2011-2013) and the need for change 9; (ii) communications and networking activities engaging various stakeholders in the process (from 2014).

Methods

Study design

This study used an action research approach 31 as part of a broader initiative that seeks to understand and influence educational institutions and programs to improve undergraduate training for BF. It was carried out in two phases: focus groups, and the validation and enrichment of their findings in a strategic planning workshop. The research protocol was approved by the Research Ethics Board of the Centre de santé et de services sociaux – Institut universitaire de gériatrie de Sherbrooke linked to Université de Sherbrooke.

Phase 1: focus groups

Population and sampling: In the spring of 2016, we carried out focus groups in three universities in the province of Quebec (Montreal, Laval, and Sherbrooke) and one in Ontario (Ottawa). We first presented the study by e-mail to professors/educators and program directors from six health disciplinesa (dentistry, medicine, midwifery, nursing, nutrition, and pharmacy) through a list created in the process of our earlier survey which had documented the BF content of these same training programs. Within each institution, we used purposeful and snowball sampling methods to select participants. Given the limited number of responses from certain professions, we made some personal contacts to improve representation. To attempt to include the perspectives of students, we invited participants to submit the names of a few interested students. To broaden viewpoints, we also invited professionals involved at different strategic points linked to the education and health systems (i.e. clinicians and internship coordinators). Each participant signed a written informed consent before participating.

Data collection: All focus groups were facilitated in French by one person in the province of Quebec (IML), and in both English and French, by another person in Ontario (BFB). The interview guide is presented in Appendix A. A note taker (MG) captured the discussion while it was being audio-recorded. Each focus group lasted between 65 and 90 minutes.

Data analysis: Initially, two researchers (MG and IML) coded individually with cross-checking (double coding) and ongoing discussion on the codebook. Once many categories had been developed iteratively in an inductive manner, coding proceeded individually (MG) with Nvivo and discussion took place with the research team whenever needed. Templates were developed around each emerging theme, synthesizing related challenges and potential solutions. The findings exposed in these templates were later subjected to validation with the participants in the strategic workshop.

Phase 2: Strategic planning workshop

Participants: We organized a provincial workshop funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and the Quebec Ministry of Health and Social Services to (i) reflect together on the BF education of future HPs; (ii) better understand the challenges that participants face to enhance BF education of future HPs; and (iii) develop a strategic action plan to improve BF education in the province. The 48 participants were mainly educators, program directors and students from seven health disciplines from six Quebec universities and one pre-university college (CÉGEP), along with representatives from four professional regulatory bodies, guests from the network of health and social services, and from two universities from other provinces (Ontario and New Brunswick), in addition to the members of the Committee on Training of the Quebec Breastfeeding Movement and two of its administrators.

Data validation: The findings from the focus groups were discussed with the workshop participants. Gathered in six working groups, they used the templates created in Phase 1 to further discuss challenges, explore new potential solutions, and complement the information. Each group presented their results in the ensuing plenary session. A workshop report was prepared by the research team and reviewed by a representative from each of the workshop’s working groups before it was finalized and distributed to all participants.

Results

Participants

Table 1 describes the 30 focus group participants (29 women) and the 48 workshop participants (44 women). Altogether, five and seven health disciplines were represented in the focus groups and the workshop, respectively.

Table 1.

Profile of participants in focus groups (FG) and strategic planning workshop (SPW)

| FG participants (n) | SPW participants (n) | Participants common to FG and SPW (n) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Role in study activities | |||

| Participants | 30 | 36 | 10 |

| Facilitators, note takers, volunteers* | 5 | 12 | 5 |

| Region | |||

| Quebec | 23 | 34 | 10 |

| Ontario | 7 | 1 | - |

| New Brunswick | - | 1 | - |

| Affiliation** | |||

| College | 2 | 1 | - |

| University | 22 | 28 | 8 |

| Professional regulatory body | - | 2 | - |

| Health organization | 5 | 5 | 1 |

| Civil society | 1 | - | 1*** |

| Function** | |||

| Associate deans, program directors | 1 | 4 | 1 |

| Professors, teachers, lecturers, practicum coordinators | 16 | 22 | 5 |

| Students, residents | 7 | 2 | 2 |

| Delegates of professional regulatory bodies | - | 5*** | - |

| Clinicians, manager (health organization) | 5 | 5 | 1 |

| Clinicians, manager (civil society) | 1 | - | 1c |

| Other – Administrative agent | - | 1 | - |

| Discipline / Program | |||

| Chiropractic | - | 4 | - |

| Dentistry | - | 2 | - |

| Medicine | 3 | 9 | 3 |

| Midwifery | 2 | 2 | - |

| Nursing | 10 | 6 | 1 |

| Nutrition | 9 | 8 | 3 |

| Pharmacy | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Other – Lactation (IBCLC) | 3 | 4 | 2 |

| Other – Maternal & newborn care | 1 | - | - |

These individuals are not included in the other section of the table (region, organization, function, discipline). All but one, were members of the Quebec Breastfeeding Movement.

Some participants had multiple affiliations and functions, and/or had more than one professional credit. Their main affiliation, function, and discipline regarding the present project are presented in the table.

This person, a member of the Quebec Breastfeeding Movement, acted as a participant in the focus group but as a volunteer during the strategic workshop.

Two were staff of professional regulatory bodies whereas the other three were professors (n = 2) or associate dean (n = 1) in universities. The last three were double counted in the table.

Main challenges related to BF education and curricular changes

Five themes emerged regarding the main challenges of BF education. The most discussed challenges were related to the insufficient interactions among various HPs (interprofessionalism), and to the lack of practical training. Several challenges were also identified regarding course content, counselling, and attitudes.

Interprofessionalism

The lack of commonalities among the different HPs’ training programs regarding their BF content, as well as the lack of knowledge with regards to other HPs’ roles and responsibilities related to BF were perceived as important challenges to the enhancement of BF education. Such gaps can induce a confusing, and sometimes contradictory, discourse among the various HPs and contribute to a lack of continuity of care in the overall support provided to mothers and future mothers with regards to BF. The following participant refers to this challenge:

I think it's important as professionals to give the same message because when [mothers] are in a moment of insecurity, it is all new … and we hang on to information, either false or alarming or that will influence our perseverance. Then, if someone goes to see the pharmacist and he says: ‘Oh, you have cracked nipples, stop breastfeeding.’ Then, the midwife tells her: ‘Continue’, and the doctor says: ‘Well, it's not that important, I was bottle-fed and look, I am a doctor...’ If the message is contradictory, when you are in a period of uncertainties, you will perhaps let it go just because you are not sure. So it's just that ...It goes with a little teaching, if we all give a common message. Participant n°10, educator

Practical training

The paucity of practical learning, compared to theoretical learning, was emphasized in all focus groups: students are seldom given the opportunity to practice their clinical skills related to BF. Participants felt this could be attributed to the paucity of tools for teaching practical elements, and to the lack of coherence between training environments and practice settings. To enhance practical learning on BF, participants mentioned several barriers deserving of attention: the large number of students to be trained, the small number of educators knowledgeable about BF, the low priority given to BF in various settings, and the lack of resources and of time. This is illustrated in the following quote:

But when it comes to practice … I do private consultations, and when I had my first female patient... a consultation in regards with breastfeeding, I panicked. It took me a day to really prepare myself because of counselling ... yes, I know the science, but what do I do concretely? I do not know her level of education, or any of that. So really ... maybe, I don’t know ... an hour on..., something practical, how it happens in real life." Participant n°23, graduate student

Course content

The absence of specific standards or accreditation criteria for BF education of HPs in Canada was underlined:

We are very well supported on the diagnostic side, on the clinical side, but when we want to see what basic content we want to teach our medical students, we have far fewer guidelines from accreditation organizations. We could say that we have almost « carte blanche » on this side, so for the moment we are using what we already taught in the old program as a starting point for the basic content we are going to put into the new program. Participant n°5, educator

Each program seems to not only develop its own curriculum (number of hours, choice of courses, concepts, skill levels, evaluations), but it often does so with few, if any, educators trained in BF. Without guidance from accreditation organizations or regulatory bodies, HPs trained in different disciplines and/or institutions can thus end up with widely varying perceptions of what is adequate support for a woman who wishes to breastfeed. The large number of programs to be harmonized and the lack of flexibility within each program are among the barriers perceived to overcome this challenge.

Counselling

The BF knowledge students acquire during training is often insufficient to enable them to adequately counsel women and families. This participant illustrates the related difficulties encountered:

What we often forget is communication. How to communicate, that is really what breastfeeding (care) is about. [...] There is no communication training about how I will transmit information of public health or teach healthy lifestyle habits [...] How will I transfer the information? There is information about breastfeeding, but there are also knowledge, interpersonal skills and “know-how”... Participant n°19, lactation consultant

This challenge was sometimes linked to the insufficient practical learning mentioned above, such as the lack of exposure to real-life situations. In addition, key counselling situations for which HPs should be trained have not been defined. The lack of expertise of several educators related to BF counselling was also highlighted as a barrier to change.

Attitudes

Several participants recognized that, when accompanying mothers and expectant mothers, HPs are strongly influenced by all kinds of intrinsic and extrinsic factors, such as their own values, personal experiences, or social norms. A lack of understanding of the influence of attitudes on professional practice, and the difficulty in changing attitudes, which are often rooted in deep values, can make the task all the more complex. The emotional charge related to BF, a subject often perceived as sensitive and intimate, and the limited amount of time to deal with such an issue, further add to the complexity of this challenge.

Sometimes breastfeeding is complicated, and there are people who have tried and have not been able to do it as they would have liked, and that can influence them to be less supportive or in any case ... even if we do not say it, we think so strongly that the woman can feel that it is complicated and it is perhaps better (not to breastfeed) ... It means that there are … times as a professional when you do not break away from your personal experiences. Participant n°11, clinician

Potential solutions for enhancing BF education

To address the various challenges and barriers identified, several potential solutions were proposed by the focus group participants and then validated during the workshop. New ones emerging from the discussions during the workshop were also added. Shown in Table 2, they provide a useful bank of ideas to guide actions. We classified the proposed potential solutions according to the 5 emerging themes presented above, although some of them could qualify regarding more than one theme.

Table 2.

Potential solutions for enhancing BF education

| Themes | Potential solutions |

|---|---|

| Interprofessionalism | Insert a course on interprofessional collaboration and include a case study or a clinical vignette on BF. Integrate interprofessional simulations of BF situations. Promote and support the use of interprofessional education activities based on best practices (e.g., academic clinics or a simulation centre). Ensure the sharing of tools for greater standardization of education material (e.g., creation of a widely available BF support portal, video or course that can be shared among programs). Develop a communication tool on the roles of different HPs regarding BF. Promote and strengthen networking (e.g., health games, a form of interprofessional competition that allows networking in a friendly context). |

| Practical training | Determine the levels of practical/clinical expertise to be acquired in each specialty. Prioritize the students most involved with mothers (e.g., perinatal care, pediatrics, family medicine). Identify novel practicum locations and other learning sites e.g., BF clinics, community BF support organizations, birthing centres, clinics or centre for simulations in health linked to a university. Strengthen practice in clinical laboratories. Use a problem-based teaching approach. Encourage student-professional pairings and shadowing (e.g., between a student and a IBCLC certified lactation consultant for 1 or 2 days of practice). Train students to observe and analyze. |

| Course content | Define minimum competencies that all future HPs should possess and minimum competencies specific to each profession. Identify key clinical situations and critical periods during which future HPs should all be able to accompany mothers and future mothers. Incorporate supportive training hours into key clinical situations by minimizing focus on other topics (e.g., less on promoting the benefits of BF and more on providing relevant support to women). Develop common pedagogical materials: creation or use of a training video that would be accessible online and open to all programs. Make better use of existing resources (e.g., create a directory). Design a microprogram to train current and future educators. Strengthen networking among educators who teach or are responsible for BF courses. Rely on positive models used in other provinces or countries, or in other areas of expertise. |

| Counselling | Engage communication specialists and others e.g., educators, sociologists, social workers, psychologists, who can provide improved approaches (e.g., advance counselling, non-guilty approach, support relationship). Engage BF clinicians (e.g., IBCLC certified lactation consultants) not only to train students, but also to review curricula. Use the patient-as-partner* approach (e.g., integration of patients in student scenarios). Encourage the pairing between training programs and various community organizations (e.g., BF clinics, community BF support organizations). |

| Attitudes | Address the myths associated with BF. Use reflective practice in training and in practicum and help students to situate their role and personal biases towards BF. Consider the ethical obligations of each profession and make the links with BF practice. |

Abbreviations: BF, breastfeeding; HPs, health professionals; IBCLC, International Board Certified Lactation Consultant.

The patient-as-partner approach seeks to involve patients more actively in healthcare services32

Discussion

Understanding the challenges related to BF education and barriers to curricular change

The many challenges to enhance BF education and barriers to curricular change identified by focus group participants, and later validated in the strategic planning workshop, all attest to a certain awareness of the problems they pose for program planners and educators. Challenges and barriers were also strikingly similar in the different groups, though some important nuances were sometimes added. For example, while the importance of positive attitudes towards BF, and the considerable investment required to address these attitudes adequately, were clearly recognized in all groups, one participant further insisted on the need to respect a women’s choice (BF or not) and the need to make sure that no feelings of guilt were aroused by the delivery of HPs’ interventions. While for many, this type of concern would be a given, it is probably necessary to specify that it needs to be part of the curricular changes pursued. Educators need to be aware of their own, and often unconscious, attitudes regarding BF, which may impact the way they tackle BF education. In addition, the communication skills acquired for counselling in some programs of HPs may not be equal in all programs. For example, medicine has given much more attention to communication in recent years with the use of the competency framework CanMEDS.33

Of note, no barrier emerged from the focus groups with regards to interprofessionalism. This may be because the participants had not been involved in the development of interdisciplinary training and thus did not envision some of the barriers that can arise. Given its increasingly recognized relevance for the training of most professionals, universities across Canada have been encouraged to develop this area in the past years.34,35 Thus, most students now need to take interprofessional collaboration courses during their studies. Such focus may also explain why it emerged as an important theme in the discussions. In this context, an opportunity presents itself to: (i) include BF content into interprofessional courses, which would directly contribute to harmonizing BF care and practices among various HPs; (ii) pay attention to the distinct and common roles of each profession for BF care; and (iii) raise awareness on the role of BF-related community organizations. Several suggestions to do so were made by participants, and many were in line with other experiences in interprofessional education.36-40

For optimal BF education, course content should be based on the latest scientific evidence and on practical knowledge; it should thus evolve over time. Currently, the very limited number of faculty knowledgeable in the area of BF and the frequent use of outdated materials complicate the development of appropriate and relevant course content. In the future, HPs need to acquire a common understanding of the evidence base for BF and to understand BF as a biopsychosocial process that is dynamic, relational and that changes over time, so as to provide mothers with relevant and non-contradictory support. They should also know how to discuss a mother's decision for infant feeding, or how to adequately evaluate BF or infant feeding. At the time of the study, though several recommendations existed,41,42 there was no agreed core content or competency framework for HPs. However, in 2020, the World Health Organizations (WHO) and UNICEF published a Competency Verification Toolkit to help ensure that health care providers possess BF competencies43 (available in English and French): this toolkit is helping move from a paradigm based on the number of training hours in BF to one of BF competency verification. It is likely to become the gold standard in BF education.44

Regulatory bodies or other accreditation institutions could play an important role to ensure core BF competencies are inserted into the curriculum of health professions, using the newest resources in this area. In addition to the aforementioned WHO/UNICEF Competency Verification Toolkit, in 2021, the Quebec Ministry of Health and Social Services published online a revised national training on BF that takes about seven hours to complete.45 This training could be seen as a starting point in Quebec to help health care providers to acquire several BF competencies. The use of such resources is expected to facilitate the creation of harmonized and optimal course content for future HPs regarding BF, so that adequate support can be provided for all mothers and future mothers, and this, regardless of whether they breastfeed or not. Another powerful motor of change could be for regulatory bodies to include the content of the toolkit (primarily BF competencies) among their conditions to access the right to practice.46 Currently no regulatory body or accreditation institution in Quebec includes such criteria though, since September 2012, Accreditation Canada’s criteria for hospitals include many elements of the BFI.47

While the barriers to changes needed in curricula may appear difficult to overcome, they are not insurmountable. Starting with small incremental changes in curricula rather than aiming initially for total transformation may be more feasible. For example, several hours now dedicated to promoting the best-known benefits of BF could instead be used to examine processes associated with successful BF and with resolving BF difficulties. Acquiring some competencies in relation to BF can also be achieved by inserting appropriate notions in general theoretical courses such as physiology or pharmacology and not only in those related to perinatal care or pediatrics. Such approaches would limit the impact on the number of hours required, while allowing the different stakeholders to gradually engage to work on a comprehensive process. However, and as suggested by Lawrence and Lawrence,48 the BF content of training should be part of the total curriculum, as opposed to something a student can elect to do in their last year of training when most assignments are elective. BF education also needs to reach a balance between theoretical learning and practical learning in real life situations.

An emerging framework for transforming health professions education

Although participants were asked to discuss the main challenges around BF education and barriers to changes in curricula, they frequently raised issues encountered in clinical practice. This urged us to further consider the challenges experienced by the workforce and their perceived relationship to the training programs. We revisited the challenges and barriers and reclassified them. Strikingly, while doing a summary table of the findings, interlinked categories emerged as all challenges fit into three broad categories: health system, education system, and curricular change process (see Table 3). It shows that the challenges of the workforce who are in the health system can be linked to features of the education system, while related barriers linked to the curricular change process need to be considered in order to effect change.

Table 3.

Challenges related to BF education and barriers to curricular change

| Categories | Challenges of the workforce (Health system) | Challenges around BF education (Education system) | Barriers to changes needed in curricula (Curricular change process) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Themes | |||

| Interprofessionalim | New HPs lack knowledge of roles and responsibilities of other professionals related to BF | Lack of consultation among the different programs training HPs regarding their BF content | None mentioned |

| Practical training | New HPs did not acquire sufficient skills for relevant BF support (e.g., assess initial latch and sucking behaviour, identify engorgement, cracking, thrush…) | Lack of opportunity for students to practice their clinical skills for BF support Lack of tools for teaching practical elements Lack of connection between training environments and practice settings |

Lack of priority given to BF in the various programs Limited number of sites and short duration of practicum Lack of adequately trained teachers for BF Large number of students Financial issues Program rigidity Lack of time Small number of IBCLC certified lactation consultants |

| Course content | New HPs have acquired concepts that differ from one program to another and from one training institution to another | Freedom for content and lack of clarity in objectives to achieve appear to limit program development Several books and reference tools used are outdated as to BF data and recommendations BF courses are allocated without consideration for the professors/educators' expertise |

Absence of specific standards or accreditation criteria for BF education Large number of programs to be harmonized Some rigidity within programs (e.g., difficult processes for changing course outline, delays) Limited number of hours available Fixed number of credits |

| Counselling | New HPs did not acquire sufficient BF knowledge to adequately counsel women and families | Lack of exposure to real life situations Key counselling situations for which HPs should be trained, have not been defined |

Lack of available training hours to incorporate scenarios with real life situations Lack of expertise of teachers with BF counselling |

| Attitudes | HPs’ behaviours are strongly influenced by several intrinsic and extrinsic factors related to their own values, personal experiences, or social norms | Lack of understanding of the important influence of attitudes on professional practice Difficulty of changing attitudes which are often rooted in deep values (those of teachers, students, and professionals) Emotional charge related to BF |

Limited amount of time and expertise to tackle this topic |

Abbreviations: BF, breastfeeding; HPs, health professionals; IBCLC, International Board Certified Lactation Consultant

To make greater sense of our findings, we then examined frameworks related to the education system for health professions that went beyond the curricular change process. This led us to create Figure 1, which takes a systems perspective that draws attention to the various systems, parts, and steps relevant to the curricular change process; it illustrates the important links between the health system, the education system, and the curricular change process. All of those elements need to be considered to achieve the greatest changes in BF education.

Figure 1.

A systems perspective for transforming health professions education

Source: adapted from Frenk et al.,49, Bland et al.30 & Loeser et al.50

The left-hand part of Figure 1 is based on a Lancet report on the work of 20 commissioners around the globe who came together to develop a shared vision and a common strategy to transform the education of HPs for the 21st century.49 Their work presented an integrative framework that explicitly emphasizes the importance of connections and interactions between the health system and the education system to ensure a well-prepared workforce that influences health outcomes. It considers people as the co-producers and drivers of needs and demands in both systems. In Figure 1, the population appears to be the starting point to ensure that the two systems (health and education) consider, and respond to, the needs of the population.

The results of a 2014 study illustrate the needs of Quebec mothers regarding BF: (i) for primiparous mothers, more than half (53%) believe that the HPs who followed their pregnancy did not prepare them enough to face the possible challenges with BF and 60% experienced major difficulties; (ii) only 59% considered that the information provided on BF by the various HPs they met at the birth site was uniform; (iii) according to 31% of the women, the HPs who followed their pregnancy never talked about BF, or only did so during one visit (30%).51 These findings further support the need to increase BF education for HPs, especially those in contact with mothers at the birth site and during the first few weeks after birth, while BF is being established. These are good examples of the population’s needs for adequate care and of the need for linkages with the workforce (health system).

Regarding the health system, the second column of Table 3 shows the challenges for the workforce and refers to the manifestations of their competencies (or lack) regarding BF. While in-service training can address challenges in that system, such training is costly, always needs to be renewed, and does not always reach everyone who needs it. It appears more effective to target the initial training of HPs so as to address the problem at its source. A large number of potential solutions were proposed in this study and most are geared towards the education system.

Triggering a change process to transform the education of HPs on BF also requires understanding the curricular change process. To that end, the right-hand part of Figure 1 shows the various stages of the curricular change process described by Bland et al.30: planning, initiation, implementation and institutionalization. This sequential model can be insightful for those who are working (or intend to work) for curricular change. To illustrate each phase in a more concrete manner, we added within the cycle, the ones proposed by Loeser et al.,50 as they appear to provide high-level guidance to potential change agents.

The strong connection between the two systems (health and education) is not only relevant for BF education, but for many other topics. This has significant implications for how curricula are developed or enhanced over time. The fact that many educators continue to have a clinical practice helps to link those two systems, but it is not a sufficient bridge. There is a need for change agents who can facilitate various processes, share knowledge regarding specific issues, and even act as boundary spanners to connect individuals from different disciplines and from the two systems who do not normally interact.52,53 A community of practice led by a knowledge broker54 around a specific thematic content may help to go beyond disciplines and to cross the boundaries of the systems

Strengths and limitations

There are several strengths to this study. First, the focus groups took place in four universities in different regions of two provinces in Canada, representing various educational contexts. Second, most studies in health are limited to curricular change in medical programs and we have taken a more comprehensive view by including seven health professions. Third, the findings from the focus groups were validated with a group of people who represent the most involved with the issue (educators, program directors and a few students), but also representatives of the health system. Fourth, those same people proposed solutions for their own contexts, making them most likely realistic and applicable. Finally, this study has been comprehensive by reinterpreting the findings in light of the broader literature and by considering the health system, the education system and the curricular change process. The systems perspective developed and presented in Figure 1 is by itself an important contribution to broaden the understanding of related issues.

The limitations of this study include a potential selection bias when recruiting participants to the focus groups, as the people more interested in, or more concerned with BF education, were more likely to have participated in the study than those who are not. Barriers in real life may therefore be more important than those observed here, though they are not likely to be different. However, given that our goal was to engage participants in a change process related to the broader initiative, interested participants and champions were targeted, so that they could become vectors of change in their programs. While most participants were women, the few men who participated did not seem to react differently, though this may require some attention. Most of the identified challenges are similar to those described in curricular change attempts for issues other than BF.30,55-58 However, most of the curricular change experiences documented to date relate to the medical school setting, and we could find little, if any, documentation about the curricular change process for other health professions. Although the main topic of the study was BF education, many findings appear transferable to other training contexts, especially the emerging framework for transforming health professions education.

Finally, the strengths of our broader initiative (see Box 1) include: (i) building on several related efforts carried out over past years; (ii) consolidating partnerships developed with stakeholders from various academic institutions; and (iii) building on a shared desire to move towards concrete changes in seven health professions. As a direct outcome of the strategic planning workshop, 17 participants volunteered to form a strategic group to gradually take over the mandate of the Committee on Training. This group represents seven professions, nine academic institutions and two professional regulatory bodies. Members have since met on a regular basis to advance on some of the challenges identified and to move along the subsequent phases of the curricular change process.

Conclusion

In this study, we identified and linked challenges experienced by the workforce, challenges around BF education, and barriers to changes in curricula. Those need to be addressed in order to improve the training of HPs, so as to provide relevant support for future mothers, mothers and their families. These challenges and barriers largely revolve around five themes: interprofessionalism, practical training, course content, counselling and attitudes. Several solutions were also proposed and validated. A strategic group of stakeholders has emerged from the broader initiative to undertake this endeavour and continue to be in action. Overall, this study also illustrates the curricular change process that appears required for certain health issues to be better addressed in the education of HPs to ensure the needs of the population are met.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all participants in the focus groups and the strategic planning workshop at which the results of the focus groups were validated for their time, insights, and contributions to better understand the context for the breastfeeding education of health professionals. In addition, we are grateful to Dr Paul Grand’Maison, Dre Paule Lebel and Pre Louise Dumas for their contribution to the strategic planning workshop and to Marie-Caroline Bergouignan and Raphaëlle Petitjean for their help in organizing it. Discussions with Jacqueline Wassef and Myrtha Traoré, members of the Committee on Training, were of great value throughout the process of this study.

Appendix A: Interview guide for focus groups with professors and individuals responsible for breastfeeding training

This interview guide will be used to guide the interviews with professors and individuals responsible for breastfeeding training representing six health care professions targeted for this research project. Some questions may be more relevant to some professionals than others.

Date: ____________________________

Sex: F M

Profession: _____________________________

Number of years of experience working in this profession: _______________

Number of years of experience related to breastfeeding training: _______________

Based on your perception of the training currently offered to students in terms of breastfeeding in your program, what would you like to change to offer an improved support to mothers wanting to breastfeed?

To your knowledge, what would be the barriers/obstacles to modifying this training?

Mothers often complain about conflicting messages received by different professionals. To solve this issue, many people wish that the breastfeeding training be better harmonized among different health care professionals. In your opinion, which are the barriers/obstacles to harmonizing this training?

Currently, what worries you the most regarding a greater harmonization of trainings? Other preoccupations? (not necessarily related to the harmonization, but to enhancing breastfeeding competencies? Or related with the process of change?)

Currently, what worries you the most regarding changes to your own program?

According to you, which factors could facilitate a transition towards more solid breastfeeding training in health care training programs? What kind of potential solutions do you envision?

Are there key people in your departments who should participate to the process of change/enhancement? Who are they?

Thank you for your participation.

Footnotes

The overall initiative seeks to also influence chiropractic; we therefore sometimes refer to seven professions. Participants from chiropractic were involved in the workshop but not in the original survey, nor in the focus groups.

Conflicts of Interest

All authors confirmed that they have no conflict of interest related to the content of this paper.

Funding

The authors wish to thank the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (Grant #335032) and the Quebec Ministry of Health and Social Services (Ministère de la Santé et des Services sociaux du Québec) for their financial support for the strategic planning workshop. The funders played no part in the study.

Contributions

IML and MB conceptualized the study and played leadership roles throughout all stages. JL and SC commented on the development of tools and study protocols. All authors (except CP and IG) planned and carried out the validation process at the workshop. LP, IC and JHL participated in data collection for the focus groups in Quebec. BFB and CP collaborated for data collection in Ottawa, and for the interpretation of findings. IML and MG conducted data analysis, interpretation of results and drafting of the different sections of the manuscript. All authors (except BFB, CP, and IG) participated in drafting the results and discussion. IG was the advisor of IML for her post-doctoral dissertation during this study; she provided advice throughout. All authors read, commented, and approved the final manuscript.

References

- 1.Rollins NC, Bhandari N, Hajeebhoy N, et al. Why invest, and what it will take to improve breastfeeding practices? The Lancet. 2016;387(10017):491-504. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01044-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Victora CG, Bahl R, Barros AJ, et al. Breastfeeding in the 21st century: epidemiology, mechanisms, and lifelong effect. The Lancet. 2016;387(10017):475-490. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01024-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.2021 Global Nutrition Report: The state of global nutrition. Bristol, UK: development initiatives; https://globalnutritionreport.org/documents/753/2021_Global_Nutrition_Report.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 4.Neill G, Beauvais B, Plante N. Recueil statistique sur l'allaitement maternel au Québec, 2005-2006. Institut de la statistique du Québec; 2006.

- 5.Semenic S, Loiselle C, Gottlieb L. Predictors of the duration of exclusive breastfeeding among first-time mothers. Res nurs health. 2008;31(5):428-441. 10.1002/nur.20275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dixit A, Feldman-Winter L, Szucs KA. “frustrated, ”“depressed,” and “devastated” pediatric trainees US academic medical centers fail to provide adequate workplace breastfeeding support. J Hum Lact. 2015;31(2):240-248. 10.1177/0890334414568119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Semenic S, Childerhose JE, Lauzière J, Groleau D. Barriers, facilitators, and recommendations related to implementing the Baby-Friendly Initiative (BFI) an integrative review. J Hum Lact. 2012;28(3):317-334. 10.1177/0890334412445195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Simard-Émond L, Sansregret A, Dubé J, Mayrand M-H. Obstétriciens-gynécologues et allaitement maternel: pratique, attitudes, formation et connaissances. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2011;33(2):145-152. 10.1016/S1701-2163(16)34801-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Portrait de la formation en matière d’allaitement dans les programmes de formation qualifiante en santé au Québec. . 2014. https://www.inspq.qc.ca/jasp/portrait-de-la-formation-en-matiere-d-allaitement-dans-les-programmes-de-formation-qualifiante-en-sante-au-quebec. [Accessed Aug 2017].

- 10.Salas Valenzuela M, Torre Medina-Mora P, Meza Segura C. Infant feeding: a reflection regarding the nursing curricula in Mexico City. Salud colectiva. 2014;10(2):185-199. 10.18294/sc.2014.221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Webber E, Serowoky M. Breastfeeding Curricular Content of Family Nurse Practitioner Programs. J Ped Health Care. 2017;31(2):189-195. 10.1016/j.pedhc.2016.07.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pound CM, Williams K, Grenon R, Aglipay M, Plint AC. Breastfeeding Knowledge, Confidence, Beliefs, and Attitudes of Canadian Physicians. J Hum Lact. 2014:890334414535507. 10.1177/0890334414535507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sims AM, Long SA, Tender JA, Young MA. Surveying the knowledge, attitudes, and practices of District of Columbia ACOG members related to breastfeeding. Breastfeed Med. 2015;10(1):63-68. 10.1089/bfm.2014.0066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Svendby HR, Løland BF, Omtvedt M, Holmsen ST, Lagerløv P. Norwegian general practitioners' knowledge and beliefs about breastfeeding, and their self-rated ability as breastfeeding counsellor. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2016;34(2):122-129. 10.3109/02813432.2016.1160632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Feldman-Winter L, Szucs K, Milano A, Gottschlich E, Sisk B, Schanler RJ. National trends in pediatricians’ practices and attitudes about breastfeeding: 1995 to 2014. Pediatrics. 2017;140(4) 10.1542/peds.2017-1229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wallace LM, Kosmala-Anderson J. Training needs survey of midwives, health visitors and voluntary-sector breastfeeding support staff in England. Matern Child Nutr. 2007;3(1):25-39. 10.1111/j.1740-8709.2007.00079.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eisenberg SR, Bair-Merritt MH, Colson ER, Heeren TC, Geller NL, Corwin MJ. Maternal report of advice received for infant care. Pediatrics. 2015;136(2):e315-e322. 10.1542/peds.2015-0551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McAllister H, Bradshaw S, Ross-Adjie G. A study of in-hospital midwifery practices that affect breastfeeding outcomes. Breastfeed rev. 2009;17(3):11. https://search.informit.org/doi/10.3316/informit.325394244886101 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dykes F. The education of health practitioners supporting breastfeeding women: time for critical reflection. Matern Child Nutr. 2006;2(4):204-216. 10.1111/j.1740-8709.2006.00071.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Renfrew MJ, McFadden A, Dykes F, et al. Addressing the learning deficit in breastfeeding: strategies for change. Matern Child Nutr. 2006;2(4):239-244. 10.1111/j.1740-8709.2006.00068.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spatz DL, Pugh LC, Breastfeeding AAoNEPo. The integration of the use of human milk and breastfeeding in baccalaureate nursing curricula. J Nurs Outlook. 2007;55(5):257-263. 10.1016/j.outlook.2007.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine . Educational objectives and skills for the physician with respect to breastfeeding, revised 2018. Breastfeed Med. 2019;14(1):5-13. 10.1089/bfm.2018.29113.jym [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meek JY. Pediatrician competency in breastfeeding support has room for improvement. Pediatrics. 2017;140(4) 10.1542/peds.2017-2509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Feldman-Winter L, Barone L, Milcarek B, et al. Residency curriculum improves breastfeeding care. Pediatrics. 2010;126(2):289-297. 10.1542/peds.2009-3250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Holmes AV, McLeod AY, Thesing C, Kramer S, Howard CR. Physician breastfeeding education leads to practice changes and improved clinical outcomes. Breastfeed Med. 2012;7(6):403-408. 10.1089/bfm.2012.0028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barimani M, Oxelmark L, Johansson SE, Hylander I. Support and continuity during the first 2 weeks postpartum. Scand J Caring Sci. 2015;29(3):409-417. 10.1111/scs.12144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Garner CD, Ratcliff SL, Thornburg LL, Wethington E, Howard CR, Rasmussen KM. Discontinuity of breastfeeding care: “there's no captain of the ship”.Breastfeed Med. 2016;11(1):32-39. 10.1089/bfm.2015.0142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.World Health Organization . Guideline: protecting, promoting and supporting breastfeeding in facilities providing maternity and newborn services. 2017; https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/259386 [PubMed]

- 29.Breastfeeding Committee for Canada. https://breastfeedingcanada.ca/en/baby-friendly-initiative/ [Accessed Jul 2021].

- 30.Bland CJ, Starnaman S, Wersal L, Moorhead-Rosenberg L, Zonia S, Henry R. Curricular change in medical schools: how to succeed. Acad Med. 2000;75(6):575-594. 10.1097/00001888-200006000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stringer ET. Action research in education. Pearson Prentice Hall Upper Saddle River, NJ; 2008.

- 32.Karazivan P, Dumez V, Flora L, et al. The patient-as-partner approach in health care: a conceptual framework for a necessary transition. Acad Med. 2015;90(4):437-441. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Frank JR, Danoff D. The CanMEDS initiative: implementing an outcomes-based framework of physician competencies. Med teach. 2007;29(7):642-647. 10.1080/01421590701746983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Canadian Interprofessional Health Collaborative . A national interprofessional competency framework. Canadian Interprofessional Health Collaborative Vancouver; 2010. https://www.rcpi.ulaval.ca/

- 35.RCPI (Réseau de collaboration sur les pratiques interprofessionnelles en santé et services sociaux) . Schéma des pratiques de collaboration en santé et services sociaux–Guide d’accompagnement 2011:18 p. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hammick M, Freeth D, Koppel I, Reeves S, Barr H. A best evidence systematic review of interprofessional education: BEME Guide no. 9. Med teach. 2007;29(8):735-751. 10.1080/01421590701682576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gaboury I, Bujold M, Boon H, Moher D. Interprofessional collaboration within Canadian integrative healthcare clinics: Key components. Soc sci med. 2009;69(5):707-715. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.05.048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gaboury I, M. Lapierre L, Boon H, Moher D. Interprofessional collaboration within integrative healthcare clinics through the lens of the relationship-centered care model. J interprofess care. 2011;25(2):124-130. 10.3109/13561820.2010.523654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Institute of Medicine . Interprofessional education for collaboration: learning how to improve health from interprofessional models across the continuum of education to practice: workshop summary. 2013; 10.17226/13486 https://nap.nationalacademies.org/catalog/13486/interprofessional-education-for-collaboration-learning-how-to-improve-health-from [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shamian J. Interprofessional collaboration, the only way to save every woman and every child. The Lancet. 2014;384(9948):e41-e42. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60858-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine . Educational objectives and skills for the physician with respect to breastfeeding. Breastfeed Med. 2011;6(2). 10.1089/bfm.2011.9994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.United States Breastfeeding Committee . Core competencies in breastfeeding care and services for all health professionals. Washington, DC: United States Breastfeeding Committee. 2010; http://www.usbreastfeeding.org/core-competencies [Google Scholar]

- 43.World Health Organization, UNICEF . Competency verification toolkit: ensuring competency of direct care providers to implement the baby-friendly hospital initiative. 2020; https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240008854

- 44.Chapin EM, Chen C-H, Dumas L, et al. The paradigm shift in BFHI step 2: from training to competency verification. J Hum Lact. 2021:890334421995098. 10.1177/0890334421995098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ministère de la santé et des services sociaux. Formation nationale en allaitement. https://mouvementallaitement.org/ressources/formation-allaitement/ [Accessed Jul 2021].

- 46.American Academy of Pediatrics . Breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Pediatrics. 2012;129(3):e827-41. 10.1542/peds.2011-3552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Anon . Standards - Obstetric Services - for surveys starting After September 05, 2012. 2011

- 48.Lawrence RA, Lawrence RM. Breastfeeding: a guide for the medical professional. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Frenk J, Chen L, Bhutta ZA, et al. Health professionals for a new century: transforming education to strengthen health systems in an interdependent world. The Lancet. 2010;376:1923-1958. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61854-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Loeser H, O’Sullivan P, Irby DM. Leadership lessons from curricular change at the University of California, San Francisco, School of Medicine. Acad Med. 2007;82(4):324-330. 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31803337de [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Haiek L, Semenic S, Lapointe N. Étude sur les besoins et les services de première ligne en matière de soutien à l’allaitement au Québec. 2014.

- 52.Williams P. We are all boundary spanners now? Int. J. Public Sect. Manag 2013; 10.1108/09513551311293417 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pelletier D, Gervais S, Hafeez-Ur-Rehman H, Sanou D, Tumwine J. Boundary-spanning actors in complex adaptive governance systems: The case of multisectoral nutrition. Int J Health Plann Manage. 2018;33(1):e293-e319. 10.1002/hpm.2468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Glegg SM, Hoens A. Role domains of knowledge brokering: a model for the health care setting. J Neuro Phys Ther. 2016;40(2):115-123. 10.1097/NPT.0000000000000122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Muller JH, Jain S, Loeser H, Irby DM. Lessons learned about integrating a medical school curriculum: perceptions of students, faculty and curriculum leaders. Med ed. 2008;42(8):778-785. 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2008.03110.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kayyal M, Gibbs T. Managing curriculum transformation within strict University governance structures: an example from Damascus University medical school. Med Teach. 2012;34(8):607-613. 10.3109/0142159X.2012.689033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lebel P, Authier L. Repenser l'enseignement des soins aux personnes âgées pour nos futurs médecins de famille. Vie et vieillissement. 2011;9(2):14-18. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Holden CA, Collins VR, Anderson CJ, et al. “Men’s health–a little in the shadow”: a formative evaluation of medical curriculum enhancement with men’s health teaching and learning. BMC med educ. 2015;15(1):210. 10.1186/s12909-015-0489-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]