Abstract

The Hippocratic Oath is the oldest and wisest description of our profession. It contains profound wisdom on the nature of health, healing, and the relationships both within and without that are necessary to the good practice of medicine. The practices described in its lines are antidotes for much of what ails modern medicine.

Keywords: Aristotle, bioethics, Hippocratic Oath, history of medicine, history of philosophy, philosophy of medicine

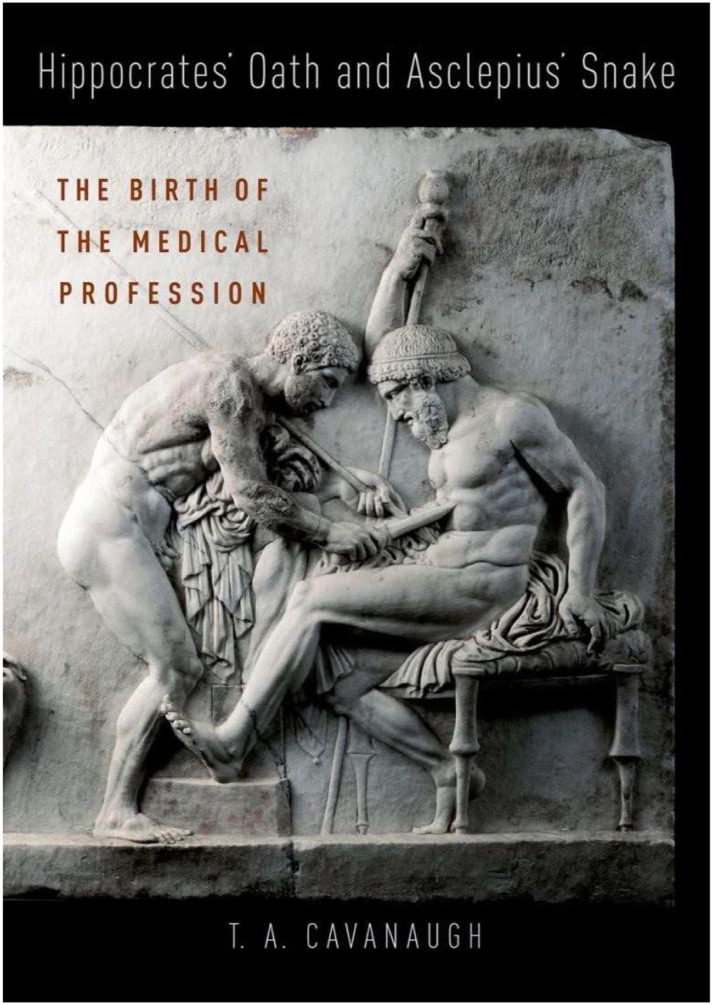

The Relief of Telephus serves as cover art to a wonderfully insightful recent addition to the medical profession’s perennial task of self-understanding (Figure 1). (Cavanaugh, 2018). The Relief dates to the first century BC and was on display in the Roman city, Herculaneum, until the city was destroyed in the same eruption of Mt. Vesuvius that destroyed Pompeii in the first century AD (LIMC 2021).

Figure 1.

Cover of Hippocrates' Oath and Asclepius' Snake: The Birth of the Medical Profession

The etched marble shows the wounded Telephus attended by his wounder, Achilles. Telephus was the King of Mysia and successfully defended his kingdom from attack by Achilles and the Greeks who mistook Mysia’s fare shores for those of Troy.

Telephus’ kingdom was saved, but Telephus was struck by the spear of Achilles. His wound would not mend so he consulted the Oracle at Delphi, the most sacred of all of Apollo’s temples.

Apollo was son of Zeus and brother to Athena and Ares. He was the god of sun and light, healing and disease, truth and prophecy, music and dance. He was “the most Greek of the Greek gods” (Isler-Kerényi and Watson 2007). The Oracle at Delphi was known for dispensing especially sage wisdom from the god of wisdom. It was the Oracle of Delphi who told the world to “Know Thyself,” to have “Nothing in Excess,” and to “Listen and Observe,” among other maxims.

The Oracle told Telephus that the “wounder will heal.” Telephus sought out Achilles, but Achilles responded that he was a warrior, not a healer. Wise Odysseus understood that it was not Achilles who was to mend Telephus, but Achilles’ spear; that which wounded Telephus’ thigh.

The Relief shows the result of Odysseus’ insight. Achilles is scraping iron filings from the tip of his spear into the wounded Telelphus’ thigh thereby healing him. The wounder heals.

Dual natures are a theme in much of Greek mythology. Zeus, father of the gods, became father through patricide. Achilles, greatest of all warriors, was laid low by a wound to the lowliest portion of his body, his heal. Apollo was the god of healing, but also the god of plagues and pestilence.

The potential dual nature of medicine is why Thomas Cavanaugh, Professor of Philosophy at the University of San Francisco, chose the Relief of Telephus as cover art in his search for the essence of our profession in his outstanding book, Hippocrates’Oath and Asclepius’ Snake: The Birth of the Medical Profession. The Relief depicts the wounder healing. Cavanaugh shows the foundational moral dilemma of medicine is the inversion: healers wounding. The healer wounding is the problem that defines every medical encounter, that has always defined every medical counter, and that will always define every medical encounter.

Iatrogenic 1 harm is the lynchpin of our entire profession and comes in a variety of flavors: Therapeutic Wounding, Error, and Role Conflation (Cavanaugh, 2018, 19‐22) The first form is essential to medical therapy. Medicine, by its nature, consists of healers wounding. Broken noses must be re-broken to set them straight. Antibiotics that cause diarrhea, stain teeth, and damage kidneys are given to eliminate infection. Sedation and neuromuscular blockade, which deprive man of his rational and bodily faculties, are sometimes needed to help patients overcome septic shock to retain those same faculties. These acts of wounding are mostly unintended and always incidental to the aimed for good. These wounds of treatment can be minimized, but they cannot be eliminated from medical practice.

The second form of iatrogenic harm comes from errors. The thriving fields of quality assurance and continuous improvement have grown out of our attempts to eliminate this source of harm. Rightfully so. We should seek to minimize failings to achieve best medical practice. But we also know that medicine is practiced by fallible beings upon fallible beings. Like the iatrogenic harm of therapeutic wounding, the iatrogenic harm of medical error will never be eliminated completely or with certainty.

The last form of iatrogenic harm is the most problematic. It is so problematic that reflection upon this harm served as the source of the Hippocratic Oath: iatrogenic harm due to role conflation. Knowing how to heal also entails knowing how to harm.

Our tribe’s medicine men have always been as much feared as esteemed because they could use their knowledge of disease and prescription to harm just as easily as they could to help.

Given the ubiquitous nature of harm in the medical encounter, it can be hard to know which sort of harm is happening. It can be hard to know which role a physician is playing: healer or wounder. Importantly, while the other two forms of harm cannot be completely dispensed with, the harm of role conflation can. This is the point of the Hippocratic Oath. The Oath is first and foremost a promise that physicians will not intentionally harm for the purpose of harming; that they will not harm by conflating their role as healer with wounder.

This paper will not venture into the questions of whether Hippocrates was the actual author of the Oath or how prevalent the Oath was in the ancient world, even though these are interesting concerns in their own right. 2 What is most important regarding the Oath is that it exposes the essence of medicine, its essential difficulties, and its internal solutions.

I swear by Apollo Physician and Asclepius and Hygieia and Panaceia and all the gods and goddesses, making them my witnesses, that I will fulfill according to my ability and judgment this oath and this covenant:

To hold the one who has taught me this art as equal to my parents and to live my life in partnership with him, and if he is in need of money to give him a share of mine, and to regard his offspring as equal to my brothers in male lineage and to teach them this art—if they desire to learn it—without fee and covenant; to give a share of precepts and oral instruction and all the other learning to my sons and to the sons of him who has instructed me and to pupils who have signed the covenant and have taken an oath according to the medical law, but no one else.

I will apply dietetic measures for the benefit of the sick according to my ability and judgment; I will keep them from harm and injustice.

I will neither give a deadly drug to anybody who asked for it, nor will I make a suggestion to this effect. Similarly I will not give to a woman an abortive remedy. In purity and holiness I will guard my life and my art.

I will not use the knife, not even on sufferers from stone, but will withdraw in favor of such men as are engaged in this work. Into whatever houses I may enter, I will come for the benefit of the sick, remaining clear of all voluntary injustice and of other mischief and of sexual deeds upon bodies of females and males, be they free or slaves.

Things I may see or hear in the course of the treatment or even outside of treatment regarding the life of human beings, things which one should never divulge outside, I will keep to myself, holding such things shameful to be spoken.

If I fulfill this oath and do not violate it, may it be granted to me to enjoy life and art, being hon- ored with fame among all men for all time to come; if I transgress it and swear falsely, may the opposite of all this be my lot (Kass 1985) 3 .

The Hippocratic Oath is not a list of rules—of “thou shalls” and “thou shall nots.” And it is not a list of potentially agreed upon action items between so called “healthcare consumers” and “providers.” In fact, the only part of the Oath that looks at all like a contract is the second paragraph which deals with how doctors are to treat themselves and their students. There is nothing contractual about how a doctor should treat his patients. Promises to protect and care for patients, and hopes for glory if those promises are fulfilled, are what guide the doctor–patient relationship.

The Hippocratic Oath is a description of what the good doctor looks like; of the ends, means, limits, and circumstances of what good medical practice looks like. It is a collection of the kind of virtues that make a good doctor. The Oath’s middle paragraphs make the purpose of medicine clear: doctors are to help their patients become healthy using only those means that respect the person and the art while acknowledging the limits to what the physician has expertise in.

The Oath’s beginning and end situate medicine in a web of relationships between physicians and society, physicians and teachers, and physicians and patients. Technique and relationship: medicine requires mastery of both and commitment to only use the former in aid of the latter to be successful.

I swear by Apollo Physician and Asclepius and Hygieia and Panaceia and all the gods and goddesses, making them my witnesses, that I will fulfill according to my ability and judgment this oath and this covenant:

It was customary in Greek culture to swear by a god when promising or certifying; and by gods if something of particular importance was at stake. Every morning Greeks would offer prayers to Zeus Ktesios (Zeus, Protector of Wealth), Zeus Herkeios (Zeus, Protector of House-Boundary), and Apollo Agyius (Apollo, Protector of the Entrance to the House) (Cavanaugh 2018, 66). But it was not customary to swear by goddesses, much less by all the gods and goddesses. The solemnity of an oath that begins with all of these extraordinary incantations could not be more clear.

Apollo, the “most Greek of all the Greek gods” (Isler-Kerényi and Watson 2007) is the first witness to the Hippocratic Oath. He is specified in his role as physician because he had many roles, some of which were opposed to medicine. Dual natures again. The second witness is Apollo’s son, the demigod, Asclepius. Asclepius’ mother was the beautiful, but adulterous, Princess Coronis. Apollo impregnated Coronis, but she subsequently slept with a mortal while pregnant with Apollo’s child. When Apollo learned of Coronis’ infidelity (he was the god of prophecy, after all), he killed her. Not wanting to also kill his unborn son, he delivered Asclepius by caesarean section on the princess’ funeral pyre. Asclepius was then given over to the centaur Chiron to be instructed in the medical arts. Apollo was foster father to Chiron and raised him in the knowledge of medicine, herbs, prophecy, and hunting. 4

Asclepius is the demigod of health and object of the Ascelpiad clan which worshiped him in numerous dedicated temples throughout the Greek world. The Asclepiads were physicians who passed their tradition on within their families; only sons of Asclepiads could become Asclepiads. More importantly to our purposes, the Asclepiads were famous for delimiting their practice. They were renowned for acknowledging what they could not heal. In a world of sorcery, ascription of disease to defects in character or disfavor with the gods, and quackery, the Asclepiads were trusted to only attempt to heal what they thought could be healed.

Hippocrates was an Asclepiad. His Oath is both an enumeration of an already ancient tradition and an innovative solution to the problem of confining the tradition to male lineage. 5

The third and fourth witnesses are daughters of Asclepius: Hygeia and Panaceia. Hygeia means “health,” from which we derive our word “hygiene.” Panaceia—“pan” for “all,” “akos” for “cure,” is an ancillary goddess who aids physicians in the use of healing substances, salves, and compresses. She is not a sorceress; she is the goddess of the material used in the treatment of the sick (Cavanaugh 2018, 48). Finally, the Oath calls all the gods and goddesses to witness. A student promising to live up to the terms of the contract that follow the invocation with his Asclepiad teacher and then to the promises to his patients could not swear a stronger vow.

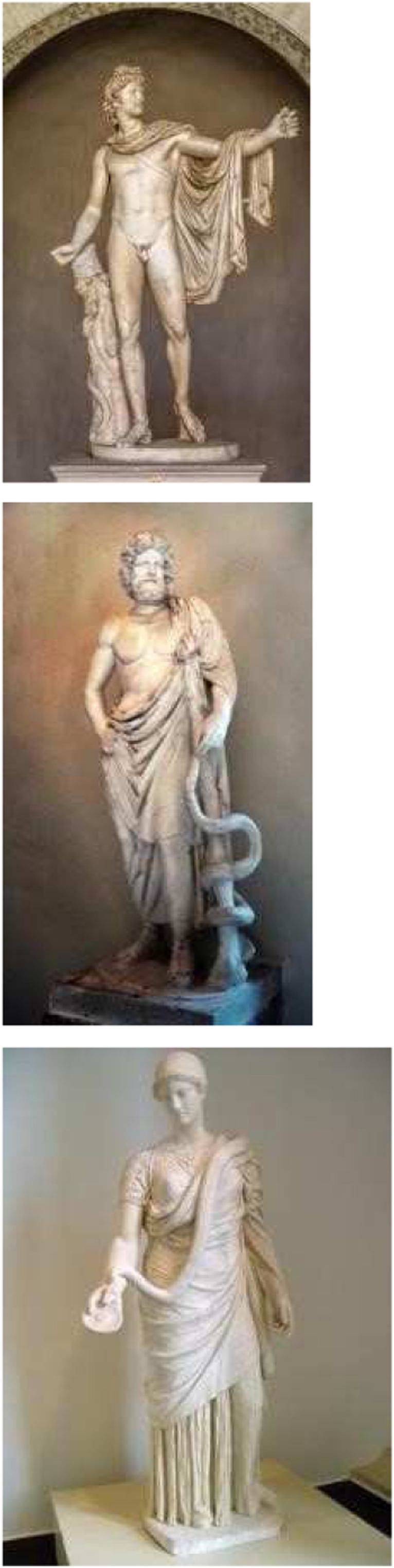

If one chanced to see statues of Apollo, Asclepius, Hygeia, and Panaceia together, one would notice a preponderance of snakes and staffs accompanying these gods and goddesses of health (Figure 2). The staff represents the itinerant nature of our profession. Physicians in the ancient world would walk from village to village seeking to help. Physicians in the not so ancient world made house calls. The historical practice of our profession had us meeting our patients in their places of comfort rather than requiring them to come to ours.

Figure 2.

Pictures of Apollo, Asclepius, Hygeia 11.

One of the most important books in the Hippocratic Corpus, The Epidemics, gets its name from this practice (Cavanaugh 2018, 11). “Epi” is Greek for “upon,” or “about,” “demos” means “village.” The Epidemics consisted of those things seen as physicians walked about the villages, from place to place. As will be shown below, the Oath takes this iatrogenic invasion of privacy into account. The Epidemics is where the most famous of Hippocratic teachings is found. It is the prime directive of Hippocratic medicine and is so fundamental that it is merely assumed in the Oath without actually being given: “First, do no harm” (Hippocrates, Epidemics 1, 11).

So much for the staff. Why all the snakes? There are multiple theories as to why Apollo, Asclepius, Hygieia, and Panaceia are all accompanied by snakes (Cavanaugh 2018, 7-14). It may be due to the regenerative nature of snakes seen in their molting. Molting looks like the renewal and restoration hoped for by medicine. It may be to call to mind snakes’ knowledge of the earth. Medicine uses earth’s healing remedies that snakes would have familiarity with given their grounded nature.

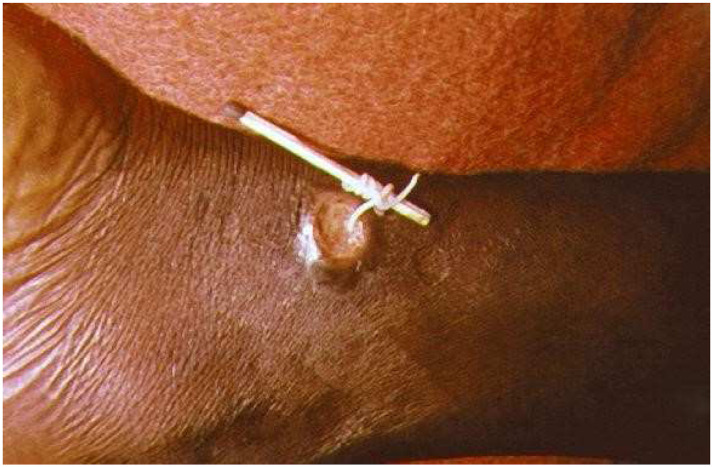

Perhaps the snake around the staff represents a still common, but ancient, therapy for a still common, but ancient, disease, Guinea Worm infestation. The Guinea Worm can be extracted from its exit wound by wrapping it around a stick and slowly turning (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Guinea worm extraction 12.

A better reason for the snakes harkens back to the problem of dual natures in general, and the problem of role conflation specific to medicine. Much of Asclepius’ medicinal prowess came from his father, Apollo, and his centaur-teacher, Chiron, but some of it also came from Medusa, by way of Athena.

Athena acquired two vials of blood from Medusa and gifted them to Asclepius (Apollodorus, 3.10.3). One vial came from a vein on Medusa’s right, the other from a vein on her left. Blood from Medusa’s right-side could heal; it would allow Asclepius to even raise men from the dead. But blood from her left would kill.

The Greeks were not the only ones concerned about dual natures. Moses’ staff could both part the waters of the Red Sea 6 and make water spring forth from rock. 7 Moses also placed a bronze snake on his staff to protect those who were bitten by venomous snakes in the Wilderness. 8

The Christological significance of Moses’ saving staff has been given physical form at the Franciscan Monastery at Mt. Nebo, in Jordan. Mt. Nebo is where Moses died overlooking the promise land he was not allowed to enter. A sculpture of Moses’ staff and snake overlooks the same vista (Figure 4). 9

… that I will fulfill according to my ability and judgment this oath and this covenant

Figure 4.

Mt. Nebo 13.

The invocation ends by telling us that both an oath and a covenant follow. The second paragraph is the covenant: a contract between students and teachers of the medical art.

To hold the one who has taught me this art as equal to my parents and to live my life in partnership with him, and if he is in need of money to give him a share of mine, and to regard his offspring as equal to my brothers in male lineage and to teach them this art—if they desire to learn it—without fee and covenant; to give a share of precepts and oral instruction and all the other learning to my sons and to the sons of him who has instructed me and to pupils who have signed the covenant and have taken an oath according to the medical law, but no one else.

The second paragraph is the only element resembling a contract to be found in premodern medicine and it clearly does not pertain to providers or consumers of health care. It only concerns teachers and students. The covenant described is a Hippocratic innovation to the Asclepiad tradition of only allowing physician-fathers to teach their sons the art. Solon, the ancient lawgiver of Athens, predating Hippocrates and Socrates by about 200 years, decreed that fathers who taught their sons a livelihood were owed the support of their sons in the fathers’ old age (Cavanaugh 2018, 49). Asclepiads without sons or with sons too young to teach were unable to take advantage of wise Solon’s law. Likewise, men desiring to be physicians without an Asclepiad father would be unable to take advantage of wise Asclepius’ teachings.

Hippocrates, acting the part of the practical physician we all aspire to be, found a solution that worked out well for everyone. Any Asclepiad in good standing (see the terms of the Oath) can teach anyone else so long as they promise to become the kind of physician who will “first, do no harm.” In return, the student will treat his mentor as his father, taking care of him in old age and teaching his other natural sons, if needed.

The second paragraph has physicians promise to treat their teachers and students as family. This family is comprised of all those who have promised to acquire the character of the good doctor described in the Oath. And only those. We do not have to be a particular kind of person to learn the medical art. But we must become a particular kind of person to practice it. This is a reminder that physicians, and man in general, is neither self-made nor self-sufficient. We must be aware that we owe a debt to those before us that can only be paid to those who come after.

The oath proper begins in the third paragraph. Remember, this oath follows an invocation to increasingly less ambiguous gods of health. Apollo’s role conflation is so evident that he has to be given a surname to mark his role. Asclepius is less ambiguous than Apollo, but his ability to save and kill with Medusa’s blood is problematic. The roles of Asclepius’ daughters, Hygieia and Panaceia, are the least ambiguous. The terms of the Oath serve to eliminate all such ambiguity about the role of mortal tenders of health.

The Greek word for “oath” is “horkos” and is etymologically related to the word “harkos,” the Greek word for “fence,” that which encloses (Cavanaugh 2018, 42). An oath binds a juror (an oath-taker) to act within a defined field of activity using defined methods of action. Methods not allowed by the oath are actions outside the limits; they are out of bounds as violations of harkos and horkos. An oath regarding medical practice will therefore necessarily describe the ends, means, limits, and circumstances of what good medical practice looks like.

Because medicine inherently involves iatrogenic harm and because there are those who would take advantage of this to inflict intentional harm, Asclepiads—Hippocratics—promise to themselves and to the world that they will, “first, do no harm” in their ends or their means.

I will apply dietetic measures for the benefit of the sick according to my ability and judgment; I will keep them from harm and injustice.

The third Paragraph begins, “I will apply dietetic measures for the benefit of the sick according to my ability and judgment.” Medicine’s end is to serve sick individuals. Not society nor abstract notions of mankind or patients. And only because they are sick. Not because they have rights, desires, or demands for health.

Medicine’s means are described as “dietetic measures” which referred to those techniques that physicians could use to help the body maintain the balance of health. Dietetics are not merely remedies for disease; they are prescriptions for health. Prescribing a diet and exercise program is not just to avoid coronary artery disease. It is to make our patients happier, healthier, and stronger.

The end of the third paragraph and the whole of the fourth make clear that this seeking of health is not solely dependent on patient desires. Health is an objective good. The good physician will not harm their patient even if the patient desires this. These notions of health and medicine were radically uprooted in late modernity as emphasis on subjectivity and individuality came to reign. But this does not mean that the modern move was correct or wholly successful. In fact, we are gradually re-discovering these ancient truths.

Galen was the greatest of Hippocratic physicians and his medical theory was still being employed 1700 years after his death. Galen understood health as a balance between three kinds of things: Natural Things, Contra-Natural Things, and Non-Natural things (van’t Land 2012).

The seven Natural Things were out of man’s control and naturally tended towards achieving the balance of health: elements, complexions, humors, members, spirits, virtues, and operations. The three Contra-Natural Things were pathologies only somewhat under man’s control: causes, signs, and diseases. The six Non-Natural Things were the things that man had control over. We must therefore use reason to balance the six Non-Natural Things to thereby achieve health.

Galen said that health resulted from moderation of

Air

Sleep and wake

Diet

Passions of the mind

Exercise and rest

Retention and evacuation of wastes

Galen’s list looks remarkably similar to evidence-based recommendations for nonpharmaceutical interventions for hypertension (Fu et al. 2020), pain (Tick et al. 2018), and depression (Gartlehner et al. 2017). It is hard to overstate Galen’s influence on medicine. The six Non-Natural Things were still in use in modified form in the 1800s and were known as the Laws of Health (Berryman 2010). It was only with the advent of modern medicine in the late 1800s and early 1900s that the focus on health shifted to a focus exclusively on disease.

Balancing the Non-Naturals to achieve health was what dietetics were for. They helped achieve health, understood as a bodily virtue, the well-working of the organism as a whole (Kass 1985). 10 Hippocratic physicians promised that they would only do things to help the body function well.

I will neither give a deadly drug to anybody who asked for it, nor will I make a suggestion to this effect. Similarly I will not give to a woman an abortive remedy. In purity and holiness I will guard my life and my art.

The prohibitions on euthanasia, abortion, and other anti-life acts in the Oath are not religiously informed notions. Physician-mediated killing, whether via euthanasia or abortion, seeks to relieve suffering by destroying the body. They are therefore prohibited because they are not proper to medicine. These acts are outside the bounds of medicine because they do not assist the body to function well. The Oath understood physicians as experts guiding nature to assist nature. Only actions that aim at health then are proper to medicine.

I will not use the knife, not even on sufferers from stone, but will withdraw in favor of such men as are engaged in this work.

Humility is the virtue required to know the proper limits of an art and it is also the impetus behind the fifth paragraph’s prohibition on the practice of surgery. Columbia’s Medical School is called the Columbia College of Physicians and Surgeons. This is a reminder that these two healing arts used to be much more separate. Physicians used not to be trained in the art of surgery and vice versa. The Hippocratic Oath is not anti-surgery. It says physicians should “withdraw in favor of such men as are engaged in this work.” The Oath is deferential to surgery because surgery is out of the scope of a physician’s training.

The forswearing of surgery is no longer the case for medical training, but the advice to limit one’s practice to one’s competence is still appropriate. Remember, the Asclepiads-cum-Hippocratics were famous for their humility in the face of disease. And as much as justice demands that we only practice our expertise, it also demands that we recognize the advantages of our position.

Into whatever houses I may enter, I will come for the benefit of the sick, remaining clear of all voluntary injustice and of other mischief and of sexual deeds upon bodies of females and males, be they free or slaves.

The sixth and seventh paragraphs recognize that the medical relationship is an inherently unequal one and therefore demands special protections. To be sick is to be humbled by one’s own mortality. Illness disturbs the body and the soul and for these reasons, physicians must strive to protect whatever dignity of the patient they can. To do this, they promise not to take advantage of their patients either in word or deed. The unequal nature of the medical relationship cannot engender the sort of equality a sexual relationship requires.

Things I may see or hear in the course of the treatment or even outside of treatment regarding the life of human beings, things which one should never divulge outside, I will keep to myself, holding such things shameful to be spoken.

The license to hear intimate and embarrassing details of a patient’s life is not unlimited. Physicians are granted the privilege of intimacy for the purpose of healing. Speaking of these details outside this purpose is another non-medical act. Again, the Hippocratic Oath is not just a list of dos and don’ts. It is much more a description of the character required for medical practice.

If I fulfill this oath and do not violate it, may it be granted to me to enjoy life and art, being honored with fame among all men for all time to come; if I transgress it and swear falsely, may the opposite of all this be my lot.

The bookends of the Oath seek to further situate the dependency of the art. The invocation to the myriad gods that begins the Oath should call to mind the deep gravity of what the art hopes to accomplish. If this is accomplished, the final paragraph shows it to be a great accomplishment worthy of praise. If the gravity of the art is violated, this is an act worthy of blame.

There is much pagan wisdom to take from the Oath, but another source of wisdom, from a higher source, also speaks to the Oath’s concerns. The fifth chapter of the Gospel of John tells of Christ’s encounter with a paralyzed man just outside of the walls of Jerusalem at the Pool of Bethesda. The ill, blind, and lame would come to the pool in hopes of being healed.

Now there is in Jerusalem at the Sheep Gate a pool called in Hebrew Bethesda, with five porticoes. In these lay large number of ill, blind, lame, and crippled. One man was there who had been ill for thirty-eight years. When Jesus saw him lying there and knew that he had been ill for a long time, he said to him, “Do you want to be well?” The sick man answered him, “Sir I have no one to put me into the pool when the water is stirred up; while I am on my way, someone else gets down there before me.” Jesus said to him, “Rise, take up your mat, and walk.” (John 5:2-9)

Immediately, the man became well, took up his mat, and walked. Later, Christ was called to answer to the Jews why he had healed the man on the sabbath. Christ said he healed the man because he only does what he sees his father doing.

Jesus answered them, “My Father is at work until now, so I am at work … A son cannot do anything on his own, but only what he sees his father doing, for what he does, his son will also do.” (John 5:17, 19)

Christ, the physician, is practicing His Father’s craft.

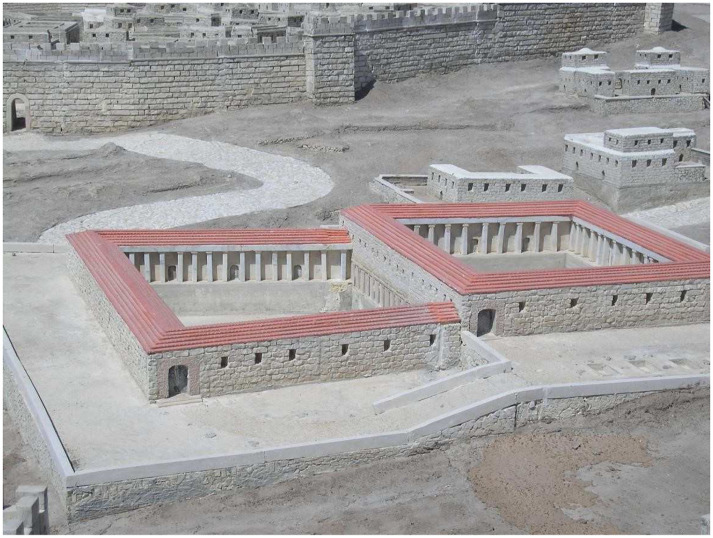

There is evidence that the Pool of Bethesda was an Asclepion, a temple to the god Asclepius (Thompson 2017) (Figure 5). There were hundreds of such temples throughout the Mediterranean and the sick would make pilgrimages to them in hopes that Asclepius would cure them. John only records four healings of Christ: Lazarus, a blind man, the royal official’s son, and the man at Bethesda. The Synoptics record many other healings, but none of these. John’s description of the healing at the Pool of Bethesda compels his readers to see parallels with Asclepius.

Figure 5.

Pool of Bethesda 14.

Both Christ and Asclepius were sons of a god and mortal women, both were agents of healing, both learned their arts from their fathers, both raised the dead. Why else tell us of a healing by Christ at a temple of Asclepius? Because John knew that Asclepius was no comparison to Christ even if there were similarities.

Christ’s answer to the Jews went further than just claiming he was doing his Father’s work. Christ says that those who believe in him thereby believe in the Father and through this belief have eternal life, avoid condemnation, and pass from death to life (John 5:24).

In a world where iatrogenic harm is rampant, where legal and explicit euthanasia is spreading, where illicit and hidden euthanasia is commonplace, where abuse and isolation have increased exponentially as the byproduct of physician recommendations to stop a pandemic; in such a world, we would do well to remember our Asclepiad and Hippocratic forebears.

How much good could be done by just promising to “first, do no harm”? By promising only to seek our patient’s health, and no other desire? By promising to always put our personal advantages second to our patients’? How much better would the world be if we were all Hippocratics? Quite a bit better.

But what did the paralytic man say? “I have no one…” The paralytic man had no one to help him, not even at an Asclepion. Now imagine that we are not just physicians at an Asclepion. We are now physicians in the guise of Christ. Grace builds upon nature. By sanctifying the natural virtues of Hippocratic medicine, we would be ready to cure our brethren not just for a moment, but for an eternity. And not just the few who make it to the pool first. We would offer cures to those, for sure. But we would also be offering cures to their families, to their friends, to everyone they encountered. Because through their encounter with us in the guise of Christ Physician, they would then become other Christ Physicians.

Christ, Physician, help us to be Hippocratics in your image. Christ, Physician, let our patients “have someone” through us through you.

Biography

William Stigall, MD, MA, is a Pediatric Critical Care Physician and Bioethicist. During residency and fellowship, Dr. Stigall obtained a Master’s in Philosophy from the University of Dallas. He has been a member and chair of multiple bioethics committees and has taught bioethics at the University of Dallas since 2012. He is a Pediatric Intensivist at Cook Children’s Medical Center and is Medical Director of Cook’s Human Research Protection Program.

Notes

from “iatros,” Doctor; and “genic,” born of

For the record, I believe he was, and I believe it was. See Ludwig Edelstein’s preeminent work, The Hippocratic Oath: Text, Translation, and Interpretation for a review of controversies surrounding the Oath (Edelstein 1943).

Hippocratic Oath, translated by Ludwig Edelstein, edited by Leon Kass in Toward a More Natural Science. The Oath as transmitter of wisdom on the doctorly virtues is best detailed by Kass in Toward a More Natural Science. It should be required reading for anyone practicing or interested in medicine.

Chiron comes from the Greek “cheir,” meaning “hand.” Chiron is a Cheirogon: one who works with his hands. “Surgeon” is the anglicization of Cheirogon. Chiron is also the first to instruct men in taking oaths.

After the Oath’s invocation of gods, but before the Asclepiad promises not to harm, comes the Hippocratic innovation. Unrelated males who promise to act as sons to Asclepiad physicians can be taught this august practice.

Exodus 14:14.

Exodus 17:5-7.

Numbers 21:8-9.

Not all staffs and snakes are created equal. The snakes on the staffs of Apollo, Asclepius, and Moses are solitary. Another ancient staff has two snakes intertwined along with a pair of wings. This is of the Caduceus. The Caduceus does not have a staff; it has a rod. And it is not Asclepius’; it is Hermes’. That is why the Caduceus also has the wings of Hermes. Hermes, Romanized as Mercury, was the messenger of the gods. He carried a rod because messengers carried messages or credentials for safe passage in rods. Hermes was also the god of commerce, thieves, and, most unfortunately for medical usages of the Caduceus, also in charge of the conduct of the dead to Hades.

Statues of Mercury with a Caduceus stand outside the Federal Reserve in Kansas City and atop the entrance to Grand Central Station in New York City. The United States had Mercury Dimes before affixing President Franklin Roosevelt’s profile to them in 1945.

The origin of the snakes on the Hermes’ rod is unclear. Perhaps it has to do with their connotations of death. Perhaps it has to do with Hermes’ ability to bring harmony from strife as is required in emissaries and negotiators of commerce. Whatever it is, it is not medicinal!

Kass traces the etymology of the world ‘‘health’’ from wholeness and well-functioning (Kass 1985, Ch 6, ‘‘The End of Medicine and the Pursuit of Health”). ‘‘Health’’ is from the Old English ‘‘hal’’ meaning ‘‘wholeness.’’ To heal means ‘‘to make whole.’’ As Dr. Kass says, ‘‘to be whole is to be healthy, and to be healthy is to be whole.’’ The Greeks had two distinct words for health: ‘‘hygieia’’ (Asclepius' daughter) meant ‘‘living well’’; and ‘‘euexia,’’ ‘‘well-habited-ness,’’ which meant a good habit of body. Neither English nor Greek words for health are related to words for disease. English stresses wholeness. Greek stresses functioning and the activity of the whole. In particular, the Greek emphasizes the need for both good habits and proper attention to attain and preserve health.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD

William Stigall, MD, MA https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9179-4111

References

- Apollodorus. 1921. Apollodorus, The Library, edited by Frazer James. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Berryman J. W. 2010. “Exercise is Medicine.” Current Sports Medicine Reports 9 (4): 195‐201. doi: 10.1249/JSR.0b013e3181e7d86d. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20622536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavanaugh T. A. 2018. Hippocrates’ Oath and Asclepius’ Snake: The Birth of the Medical Profession. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Edelstein L. 1943. The Hippocratic Oath, Text, Translation and Interpretation. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins press. [Google Scholar]

- Emerson W. K. 2016. “The Caduceus as an Army Insignia.” The AMEDD Historian 13: 1-5. https://history.amedd.army.mil/newsletters/HistoryNewsletterNo13.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Fu J., Liu Y., Zhang L., Zhou L., Li D., Quan H., Zhu L., Hu F., Li X., Meng S., Yan R., Zhao S., Onwuka J. U., Yang B., Sun D., Zhao Y.. 2020. “Nonpharmacologic Interventions for Reducing Blood Pressure in Adults With Prehypertension to Established Hypertension.” Journal of the American Heart Association 9 (19): e016804. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.120.016804. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32975166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gartlehner G., Wagner G., Matyas N., Titscher V., Greimel J., Lux L., Gaynes B. N., Viswanathan M., Patel S., Lohr K. N.. 2017. “Pharmacological and Non-Pharmacological Treatments for Major Depressive Disorder: Review of Systematic Reviews.” BMJ Open 7 (6): e014912. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016014912. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28615268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hippocrates. 1868. Hippocrates Collected Works, edited by Jones W. H. S.. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Isler-Kerényi C., Watson W. G. E.. 2007. “Modern Mythologies“DIONYSOS” Versus “APOLLiO.” In Dionysos in Archaic Greece, In An Understanding through Images, 235‐254. Netherlands: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Kass L. R. 1985. Toward a More Natural Science. Mumbai: Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- LIMC, Digital . 2021. Lexicon Iconographicum Mythologiae Classicae. Monument #8717. Accessed 08 2021. https://weblimc.org/page/monument/2079320. [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers Timothy. 2002. The Battle of the Snakes: Staff of Aesculapius vs. Caduceus. CA: Premium Care Internal Medicine. https://www.premiumcaremd.com/blog/the-battle-of-the-snakes-staff-ofaesculapius-vs-caduceus. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson Robin. 2017. “Healing at the Pool of Bethesda: A Challenge to Asclepius.” Bulletin for Biblical Research 27 (1): 65‐84. [Google Scholar]

- Tick H., Nielsen A., Pelletier K. R., Bonakdar R., Simmons S., Glick R., Ratner E., Lemmon R. L., Wayne P., Zador V., Medicine Pain Task Force of the Academic Consortium for Integrative and Health . 2018. “Evidence-Based Nonpharmacologic Strategies for Comprehensive Pain Care.” Explore 14 (3): 177‐211. doi: 10.1016/j.explore.2018.02.001. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29735382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van’t Land K. 2012. “Internal, Yet Extrinsic: Conceptions of bodily Space and Their Relation To causality In Late meEval University Medicine.” In Medicine and Space: Body, Surroundings and Borders in Antiquity analysis, edited by Baker Patricia A., Nijdam Han, van’t Land Karine. Nijmegen: Brill. [Google Scholar]