Table of Contents

Top 10 Take-Home Messages..........e541

Preamble..........e541

-

1.

Introduction..........e543

-

1.1.

Special Considerations..........e543

-

1.2.

Abbreviations..........e543

-

1.1.

-

2.

Methodology..........e543

-

2.1.

Writing Committee Composition..........e543

-

2.2.

Relationships With Industry and Other Entities..........e544

-

2.3.

Review of Literature and Existing Data Definitions..........e544

-

2.4.

Development of Terminology Concepts..........e544

-

2.5.

Consensus Development..........e544

-

2.6.

Relation to Other Standards..........e544

-

2.7.

Peer Review, Public Review, and Board Approval..........e544

-

2.1.

-

3.

Data Elements and Definitions..........e545

-

3.1.

Patient Demographics Including Age, Sex, Race, Ethnicity, and Social Determinants of Health..........e545

-

3.2.

COVID-19 Diagnosis..........e545

-

3.3.

COVID-19 Cardiovascular Complications..........e545

-

3.4.

COVID-19 Noncardiovascular Complications..........e546

-

3.5.

Symptoms and Signs..........e546

-

3.6.

Diagnostic Procedures..........e546

-

3.7.

Pharmacological Therapy..........e547

-

3.8.

Preventive, Therapeutic, and Supportive Procedures for COVID-19..........e547

-

3.9.

End-of-Life Management..........e548

-

3.1.

References..........e549

-

Appendix 1.

Author Relationships With Industry and Other Entities (Relevant)..........e553

-

Appendix 2.

Reviewer Relationships With Industry and Other Entities (Comprehensive)..........e553

-

Appendix 3.

COVID-19 Diagnosis..........e555

-

Appendix 4.

COVID-19 Cardiovascular Complications..........e561

-

Appendix 5.

COVID-19 Noncardiovascular Complications..........e574

-

Appendix 6.

Symptoms and Signs..........e576

-

Appendix 7.

Diagnostic Procedures..........e585

-

Appendix 8.

Pharmacological Therapy..........e594

-

Appendix 9.

Therapeutic and Supportive Procedures for COVID-19..........e602

-

Appendix 10.

End-of-Life Management..........e609

Top 10 Take-Home Messages

-

1.

This document presents a clinical lexicon comprising data elements related to cardiovascular and noncardiovascular complications of COVID-19 (coronavirus disease-2019). The writing committee considered data elements that are pertinent to the full range of care provided to these patients and intended to be useful for all care venues, including presentations related to acute COVID-19 in the ambulatory as well as the hospital setting.

-

2.

Data elements for COVID-19 diagnoses include confirmed, probable, and suspected acute COVID-19 case definitions. Postacute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 (severe acute respiratory syndrome-coronavirus-2) infection were also included.

-

3.

Acute cardiovascular complications related to COVID-19, including acute myocardial injury, heart failure, shock, arrhythmia, thromboembolic complications, and stroke, were defined.

-

4.

Data elements related to COVID-19 vaccination status, comorbidities, and preexisting cardiovascular conditions were provided.

-

5.

Postacute cardiovascular sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection and long-term cardiovascular complications of COVID-19 were defined.

-

6.

Data elements for cardiovascular mortality during acute COVID-19 were provided.

-

7.

Data elements for noncardiovascular complications were provided to help document severity of illness and other competing diagnoses and complications that may affect cardiovascular outcomes.

-

8.

Symptoms and signs related to COVID-19 and cardiovascular complications were listed.

-

9.

Data elements for diagnostic and therapeutic strategies for COVID-19 and cardiovascular conditions were provided.

-

10.

Advanced therapies, including mechanical ventilation, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, and end-of-life management strategies, were provided.

Preamble

The American College of Cardiology (ACC) and the American Heart Association (AHA) support their members’ goal to improve the prevention and treatment of cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) through professional education, research, the development of guidelines and standards, and by fostering policy that supports optimal patient care and outcomes. The ACC and AHA also recognize the importance of using clinical data standards for patient management, assessment of outcomes, and conduct of research, as well as the importance of defining the processes and outcomes of clinical care, whether in randomized trials, observational studies, registries, or quality improvement initiatives.

Clinical data standards aim to identify, define, and standardize data elements relevant to clinical topics in cardiovascular medicine, with the primary goal of assisting data collection and use by providing a corpus of data elements and definitions applicable to various conditions. Broad agreement on common vocabulary and definitions is needed to pool or compare data from the electronic health records (EHRs), clinical registries, administrative datasets, and other databases and to assess whether these data are applicable to clinical practice and research endeavors. Emerging federal standards, such as the US Department of Health & Human Services, Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology, and the US Core Data for Interoperability support efforts to “promote interoperability” and the more effective use of EHR data to improve health care quality. The purpose of clinical data standards is to contribute to the infrastructure necessary to accomplish the ACC’s mission to transform cardiovascular care and improve heart health and the AHA’s mission of being a relentless force for a world of longer and healthier lives for all individuals.

The specific goals of clinical data standards are:

-

1.

To establish a consistent, interoperable, and universal clinical vocabulary as a foundation for clinical care and research

-

2.

To facilitate the exchange of data across systems through harmonized, standardized definitions of key data elements

-

3.

To facilitate further development of clinical registries, implementable clinical guidelines, quality and performance improvement programs, outcomes evaluations, public reporting, and clinical research, including the comparison of results within and across these initiatives

-

4.

To ensure equity across all endeavors related to clinical data standards

The key data elements and definitions are a compilation of variables intended to facilitate the consistent, accurate, and reproducible capture of clinical concepts; standardize the terminology used to describe CVDs and procedures; create a data environment conducive to the implementation of clinical guidelines, assessment of patient management and outcomes for quality and performance improvement, and clinical and translational research; and increase opportunities for sharing data across disparate data sources. The ACC/AHA Task Force on Clinical Data Standards (Task Force) selects cardiovascular conditions, procedures, and other topics related to cardiovascular health and medicine that will benefit from the creation of a clinical data standard set. Experts in the subject area are selected to examine and consider existing standards and develop a comprehensive, yet not exhaustive, data standard set. When undertaking a data collection effort, only a subset of the elements contained in a clinical data standard listing may be needed or, conversely, users may want to consider whether it may be necessary to collect and incorporate additional elements. For example, in the setting of a randomized, clinical trial of a new drug, additional information would likely be required regarding study procedures and medical therapies. Alternatively, if a data set is to be used for quality improvement, safety initiatives, or administrative functions, elements such as Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes, International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) codes, or outcomes may be added. The intent of the Task Force is to standardize clinical concepts, focusing on the patient and clinical care and not on administrative billing or coding concepts. The clinical concepts selected for development are commonly cardiovascular specific, where a standardized terminology does not already exist. The clinical data standards can, therefore, serve as a guide to develop administrative data sets, and complementary administrative or quality assurance elements can evolve from these core clinical concepts and elements. Thus, rather than forcing the clinical data standards to harmonize with existing administrative codes, such as ICD-10-CM or CPT codes, we envision the administrative codes to follow the lead of the clinical data standards. This approach would allow clinical care to lead standardization of cardiovascular health care terminology.

The ACC and AHA recognize that there are other national efforts to establish clinical data standards, and every attempt is made to harmonize newly published standards with existing ones. Writing committees are instructed to consider adopting or adapting existing nationally recognized data standards if the definitions and characteristics are validated, useful, and applicable to the set under development. In addition, the ACC and AHA are committed to continually expanding their portfolio of clinical data standards and will create new standards and update existing ones as needed to maintain their currency and promote harmonization with other standards as health information technology and clinical practice evolve.

The Privacy Rule of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) privacy regulations, which went into effect in April 2003, heightened all health care professionals awareness of our professional commitment to safeguard patients’ privacy. HIPAA privacy regulations specify which information elements are considered “protected health information.” These elements may not be disclosed to third parties (including registries and research studies) without the patient’s permission and meeting all relevant privacy sharing requirements. Protected health information may be included in databases used for health care operations under a data use agreement. Research studies using protected health information must be reviewed by an institutional review board. We have included identifying information in all clinical data standards to facilitate uniform collection of these elements when appropriate. For example, a longitudinal clinic database may contain these elements because access is restricted to the patient’s health care team.

In clinical care, health care providers communicate with each other through a common vocabulary. In an analogous manner, the integrity of clinical research depends on firm adherence to prespecified procedures for patient enrollment and follow-up; these procedures are guaranteed through careful attention to definitions enumerated in the study design and case report forms. Harmonizing data elements and definitions across studies facilitates comparisons and enables the conduct of pooled analyses and meta-analyses, thus deepening our understanding of individual study results.

The recent development of quality performance measurement initiatives, particularly those for which the comparison of health care professionals and institutions is an implicit or explicit aim, has further raised awareness about the importance of clinical data standards. Indeed, a wide audience, including nonmedical professionals such as payers, regulators, and consumers, may draw conclusions about care and outcomes from these comparisons. To understand and compare care patterns and outcomes, the data elements that characterize them must be clearly defined, consistently used, and properly interpreted.

Hani Jneid, MD, FACC, FAHA

Chair, ACC/AHA Task Force on Clinical Data Standards

1. Introduction

The Task Force has undertaken the task to standardize the lexicon of cardiovascular medicine. This document provides data standards for cardiovascular and other complications related to COVID-19 infection caused by SARS-CoV-2. Our intent is to provide data elements consistent with current practice guidance and to include updated terminology and attributes in compliance with the methodology of the Task Force1 and with current policies of the ACC and AHA regarding harmonization of data across organizations and disciplines. There is increased importance of understanding acute and longitudinal impact of COVID-19 on cardiovascular health. Unfortunately, there has not been clarity or consensus on definitions of cardiovascular conditions related to COVID-19. Different diagnostic terminologies are being used for overlapping conditions such as “myocardial injury,” “myocarditis,” “type II myocardial infarction,” “stress cardiomyopathy,” or “inflammatory cardiomyopathy.”

These data standards will help standardize definitions and set the framework to capture and better understand how COVID-19 impacts cardiovascular health. This document is intended for use by researchers, registry developers, and clinicians and is proposed as a framework for ICD-10 code development of COVID-19–related cardiovascular conditions.

Specifically, COVID-19 cardiovascular data standards are of great importance to patients, providers, investigators, scientists, administrators, public health officials, policy makers, and payers. The ACC/AHA Writing Committee on Clinical Data Standards for COVID-19 (writing committee) envisions these data elements would be useful in the following broad additional categories:

-

•

Communication with patients

-

•

Inpatient and outpatient clinical programs

-

•

Clinical registries

-

•

Basic and translational research programs

-

•

Clinical research, particularly where eventual pooled analysis or meta-analysis is anticipated

-

•

Public health organizations

-

•

Organization and design of electronic medical information initiatives, such as EHRs, pharmacy databases, computerized decision support, and cloud technologies

-

•

Public health policy, health insurance coverage, and legislation development

-

•

Health system administrators for estimation of necessary resources such as protective personal equipment (PPE), testing, space and staffing needs, isolation, sanitation, or quarantine requirements

-

▪

Alternative models of health care such as telemedicine, virtual visits, and point-of-care diagnostic platforms.

The data element tables are also included as an Excel file in the Online Data Supplement.

1.1. Special Considerations

In this document, data elements were not differentiated for specific encounters, such as for inpatients versus outpatients, dates of encounter, number of encounters, baseline or repeated data elements. Databases can be built and customized according to users’ needs to capture such information. The intent of this writing committee was not to provide recommendations regarding COVID-19 treatment, and the writing committee recommends that readers follow prevailing COVID-19 management guidelines.

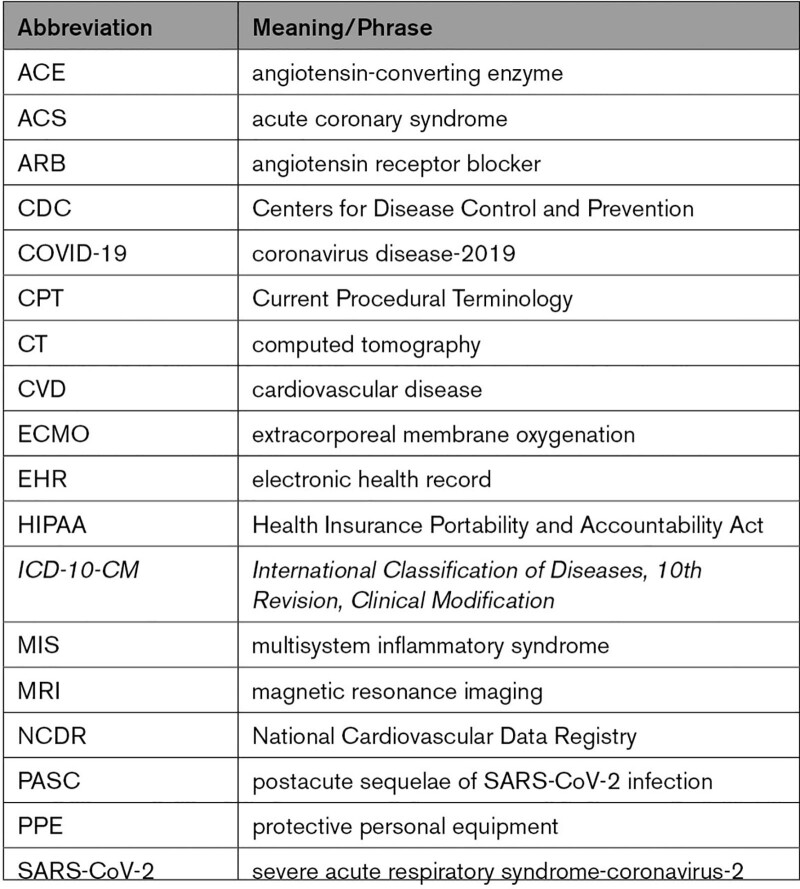

1.2. Abbreviations

2. Methodology

2.1. Writing Committee Composition

The Task Force selected the members of this writing committee. The writing committee consisted of 15 individuals with domain expertise in cardiomyopathy, infectious disease, CVD, myocarditis, cardiovascular registries, outcomes assessment, medical informatics, health information management, and health care services research and delivery.

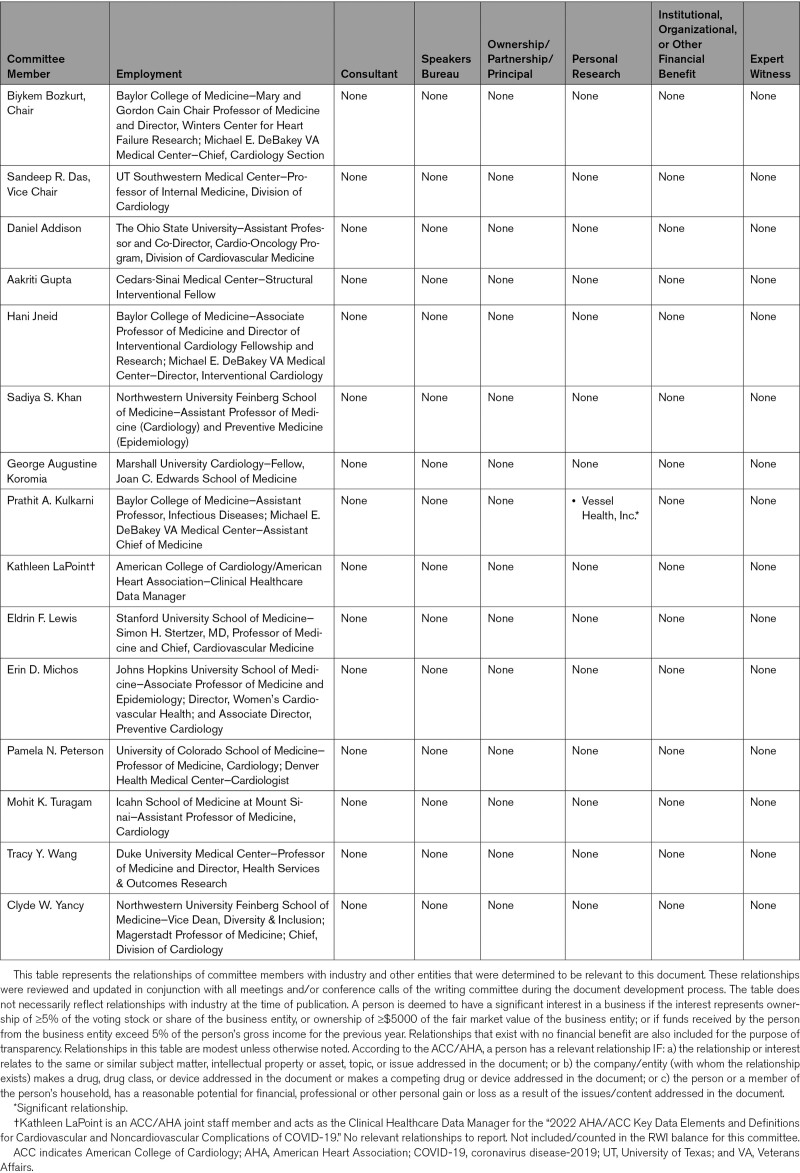

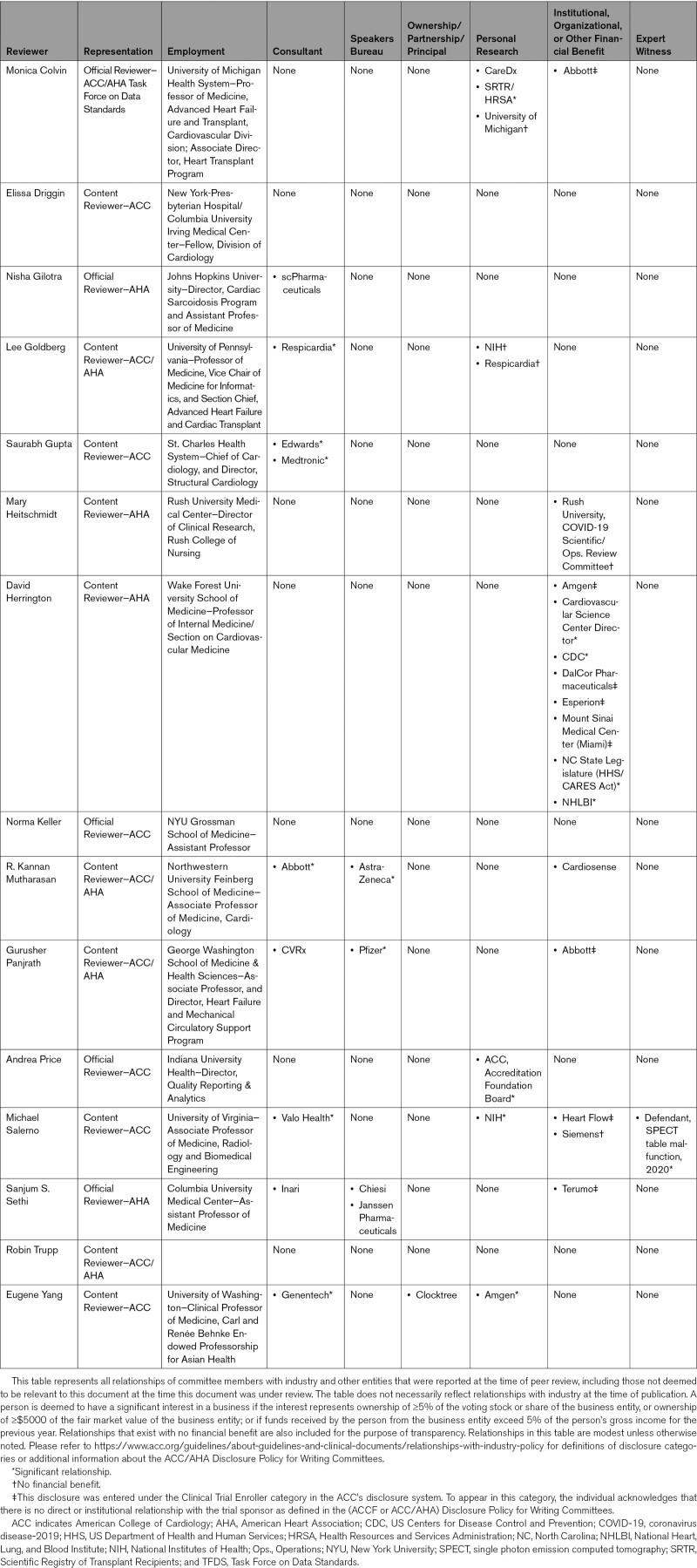

2.2. Relationships With Industry and Other Entities

The Task Force made every effort to avoid actual or potential conflicts of interest because of personal, professional, or business interests or relationships of any member of the writing committee. Specifically, all members of the writing committee were required to disclose all such relationships that could be perceived as real or potential conflicts of interest in writing. The included documentation was updated when any changes occurred. Authors’ and peer reviewers’ relationships with industry and other entities pertinent to this data standards document are disclosed in Appendixes 1 and 2, respectively. In addition, for complete transparency, the disclosure information of each writing committee member—including relationships not pertinent to this document—is available in a Supplemental Appendix. The work of the writing committee was supported exclusively by the AHA and ACC without commercial support. Writing committee members volunteered their time for this effort. Meetings of the writing committee were confidential and attended only by committee members and staff.

2.3. Review of Literature and Existing Data Definitions

A substantial body of literature was reviewed for this manuscript. The primary sources of information were the “Infectious Diseases Society of America Guidelines on the Treatment and Management of Patients with COVID-19,”2 NIH COVID-19 Treatment Guidelines,3 data definitions from the US Centers of Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and previous Task Force publications. This information was augmented by multiple peer-reviewed references listed in the tables under the column “Mapping/Source of Definition.”

2.4. Development of Terminology Concepts

The writing committee aggregated, reviewed, harmonized, and extended these terms to develop a controlled, semantically interoperable, machine computable terminology set that would be usable in as many contexts as possible. As necessary, the writing committee identified contexts where individual terms required differentiation according to their proposed use (ie, research/regulatory vs. clinical care contexts).

This publication was developed to serve as a common lexicon and base infrastructure by end users to augment work related to standardization and health care interoperability including, but not limited to, structural, administrative, and technical metadata development. The resulting appendixes (Appendixes 3 to 10) list the data element in the first column, followed by the clinical definition of the data element. The allowed responses (“permissible values”) for each data element in the next column are the acceptable means of recording this information. For data elements with multiple permissible values, a bulleted list of the permissible values is provided in the row listing the data element, followed by multiple rows listing each permissible value and corresponding permissible value definition, as needed. Where possible, clinical definitions (and clinical definitions of the corresponding permissible values) are repeated verbatim as previously published in reference documents.

2.5. Consensus Development

The Task Force established the writing committee as described in the Task Force’s methodology paper.1 The primary responsibility of the writing committee was to aggregate existing information relevant to the care of patients with CVD from external sources, such as society guidelines and existing COVID-19 data elements from the National Cardiovascular Data Registry (NCDR)4 and AHA COVID-19 Registry.5 The work of the writing committee was accomplished via a series of virtual meetings, along with extensive email correspondence. The review work was distributed among subgroups of the writing committee based on interest and expertise in the components of the terminology set. The proceedings of the workgroups were then assembled, resulting in the vocabulary and associated descriptive text in Appendixes 3 to 10. All members reviewed and approved the final lexicon.

2.6. Relation to Other Standards

The writing committee reviewed the available published data standards, including relevant data dictionaries from registries. Relative to published data standards, the writing committee anticipates that this terminology set will facilitate the uniform adoption of these terms, where appropriate, by the clinical, clinical and translational research, regulatory, quality and outcomes, and EHR communities.

2.7. Peer Review, Public Review, and Board Approval

The “2022 AHA/ACC Key Data Elements and Definitions for Cardiovascular and Noncardiovascular Complications of COVID-19” was reviewed by official reviewers nominated by the ACC and AHA. To increase its applicability, the document was posted on the ACC and AHA websites for a 30-day public comment period. This document was approved by the ACC Clinical Policy Approval Committee and the AHA Science Advisory and Coordinating Committee in February 2022, and the AHA Executive Committee in March 2022. The writing committee anticipates that these data standards will require review and updating in the same manner as other published guidelines, performance measures, and appropriate use criteria. The writing committee will therefore review the set of data elements on a periodic basis, starting with the anniversary of publication of the standards, to ascertain whether modifications should be considered.

3. Data Elements and Definitions

The writing committee explicitly elected not to include patient identification, demographic, and administrative information, such as patient sex or site of service, diagnosis, and other fundamental concept terms, including data by specific medication, as defined data elements. Comprehensive EHR solutions are anticipated to collect this information as discrete data. Furthermore, a robust solution for patient identification (eg, the unique patient identifier) is a universal requirement, whether within the context of the EHR of an individual practice or the registry aggregation of information across multiple disparate inpatient and ambulatory encounters.

3.1. Patient Demographics Including Age, Sex, Race, Ethnicity, and Social Determinants of Health

Patient age, sex, race, ethnicity, and social determinants of health are key elements in risk of infection and outcomes for COVID-19. Age, sex, race, and ethnicity are expected to be available in all EHR solutions and therefore have not been listed. We recognize the critical importance of social determinants of health, including race/ethnicity and sex, to COVID-19 and its outcomes and would like to emphasize that these variables should be captured. The Task Force has commissioned a separate data standards document to address social determinants of health for overall CVD, which we expect to be pertinent and complementary to this document, in addition to other documents published and being developed.6

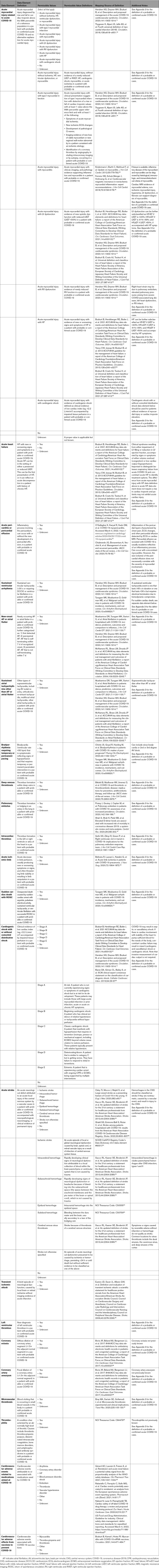

3.2. COVID-19 Diagnosis

Appendix 3 provides definitions for the diagnosis of COVID-19. A case of COVID-19 can be confirmed, probable, or suspected based on definitions from the CDC.7 A person with COVID-19 might be symptomatic or asymptomatic. Other categories of COVID-19 diagnosis provided include postacute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection (PASC) (also termed “postacute COVID-19 syndrome” or “long COVID” in the literature); persons with COVID-19 who continue to have persistently positive molecular or antigen tests after the end of their isolation period; multisystem inflammatory syndrome (MIS), a rare postinfectious inflammatory condition; prior COVID-19; and COVID-19 reinfection. The category of COVID-19 reinfection is divided into reinfection with best evidence, moderate evidence, and poor evidence, as outlined by the CDC.8 Other data elements included in this section are date of diagnosis of acute COVID-19, whether a patient was hospitalized for COVID-19 specifically or was found to have incidental SARS-CoV-2 infection at the time of hospitalization for another cause, and dates of initial hospitalization. A category also exists for exposure to someone with COVID-19 during their infectious period, with criteria based on CDC recommendations.

3.3. COVID-19 Cardiovascular Complications

Patients with underlying cardiovascular risk factors or established CVD are at greater risk for severe presentations of COVID-19. COVID-19 can also confer significant cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in patients with or without prior CVD. Approximately 10% to 20% of hospitalized patients can have evidence of myocardial injury in the setting of COVID-19.9 Proposed mechanisms include activation of inflammatory and thrombotic cascades, direct viral injury to myocytes or vascular endothelium, and worsening of underlying baseline atherosclerotic and structural abnormalities. Acute cardiovascular presentations are varied and include myocardial injury, myocarditis, acute coronary syndrome (ACS), heart failure, cardiogenic shock, arrhythmia, thromboembolic and cerebrovascular complications, and cardiac involvement and coronary artery ectasia in the setting of MIS in children (MIS-C). COVID-19 can trigger acute heart failure or cardiogenic shock. New-onset left ventricular systolic dysfunction is hypothesized to be related to myocarditis, endothelial and microvascular injury, myocardial stress in the setting of increased myocardial demand and reduced myocardial oxygenation in the setting of hypoxia, myocardial inflammation, and proinflammatory cytokine surge.10 New-onset right ventricular dysfunction can result from acute pulmonary embolism or strain from acute respiratory distress syndrome and elevated pulmonary artery pressures. Both atrial and ventricular arrhythmias have been noted.10 COVID-19 is associated with an increased risk of stroke, transient ischemic attack, and venous and arterial thromboembolic events.10 Appendix 4A summarizes the more common acute cardiovascular presentations and lists of standard data elements that describe these presentations.

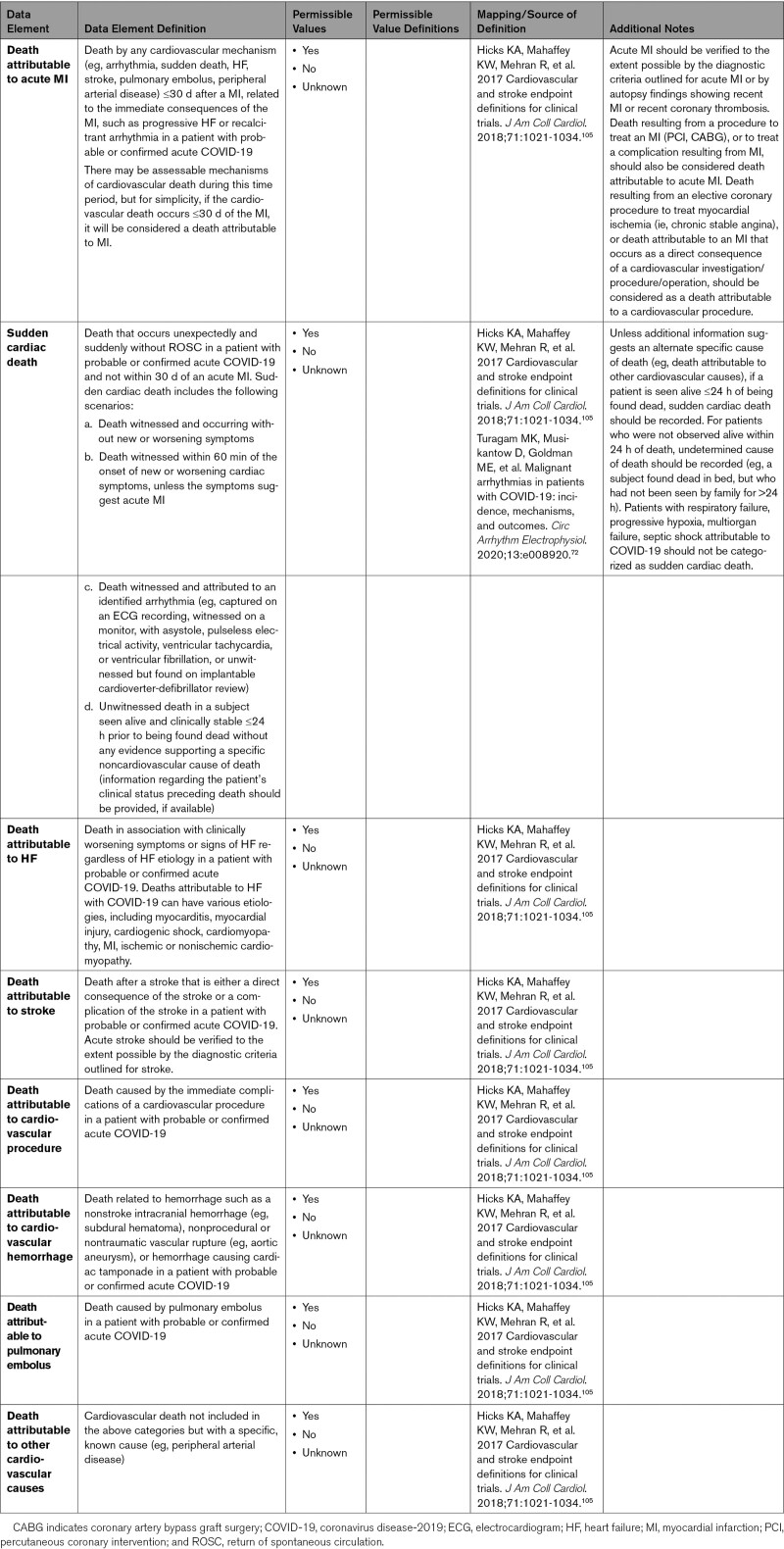

A significant proportion of patients may experience long-term complications of SARS-CoV-2 infection ≥4 weeks from the index infection, sometimes called postacute COVID-19 syndrome.11-13 Long-term cardiovascular sequelae of COVID-19 may include chest pain, palpitations, inappropriate sinus tachycardia, postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome, atrial arrhythmia, cardiomyopathy, and thromboembolism.14-16 Possible mechanisms for long-term cardiovascular complications of COVID-19 include direct and indirect viral-mediated cellular damage, procoagulant state, the immunologic response affecting the structural integrity of the myocardium, pericardium, and conduction system, and downregulation of angiotensin-converting enzyme-2 (ACE2).17-19 Myocardial abnormalities and injury have been reported on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and cardiac troponin elevations have occurred in some patients >2 months after diagnosis of COVID-19.20 Myocardial fibrosis or scar associated with cardiomyopathy from viral infection can lead to arrhythmias.21 The risk for occurrence of thromboembolic complications in the postacute COVID-19 phase is possibly associated with the duration and severity of hyperinflammatory state.13 Standard data elements that describe the long-term cardiovascular complications of COVID-19 are summarized in Appendix 4B, and data elements pertaining to cardiovascular mortality from COVID-19 are summarized in Appendix 4C.

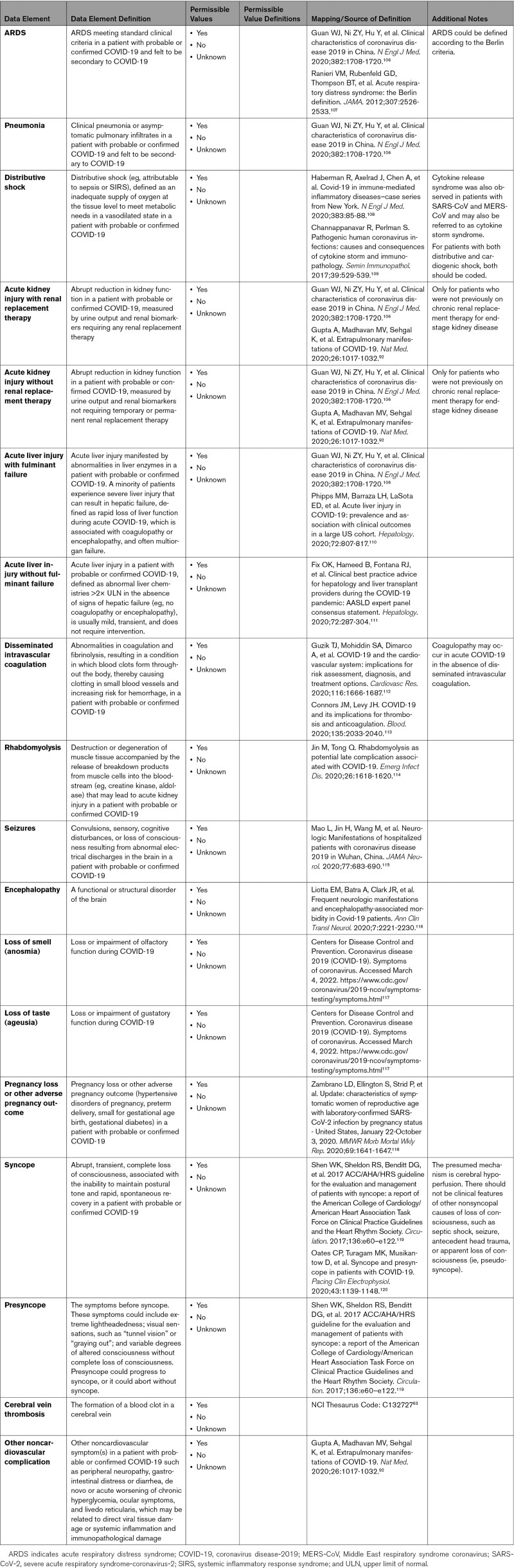

3.4. COVID-19 Noncardiovascular Complications

Appendix 5 defines the broad range of noncardiovascular complications that can occur in a probable or confirmed case of COVID-19. SARS-CoV-2 is primarily a respiratory virus that infects the upper airway and, in severe cases, can progress into a lower airway infection (pneumonia), progressive respiratory failure (acute respiratory distress syndrome), and many other systemic complications. It is uncertain whether extrapulmonary cardiovascular, as well as noncardiovascular, complications are related to indirect injury caused by systemic inflammation or to direct viral tissue damage, or both. Shock and multiorgan failure observed in severe cases of COVID-19 may be related to septic shock, cytokine storm, cardiogenic shock, obstructive shock, or mixed distributive combined with cardiogenic shock. In addition to lung and heart complications, COVID-19 can contribute to renal, hepatic, hematologic, and neurological complications. Pregnant women with COVID-19 have been identified by the CDC to be at increased risk for severe illness, and COVID-19 may be associated with pregnancy loss and other adverse pregnancy outcomes. Many other noncardiovascular symptoms during COVID-19 have been noted and include microvascular thrombosis, thrombophilia, cerebral venous thrombosis, anosmia, ageusia, rhabdomyolysis, peripheral neuropathy, gastrointestinal symptoms, de novo or acute worsening of chronic hyperglycemia, ocular symptoms, encephalopathy, skin changes, and livedo reticularis.

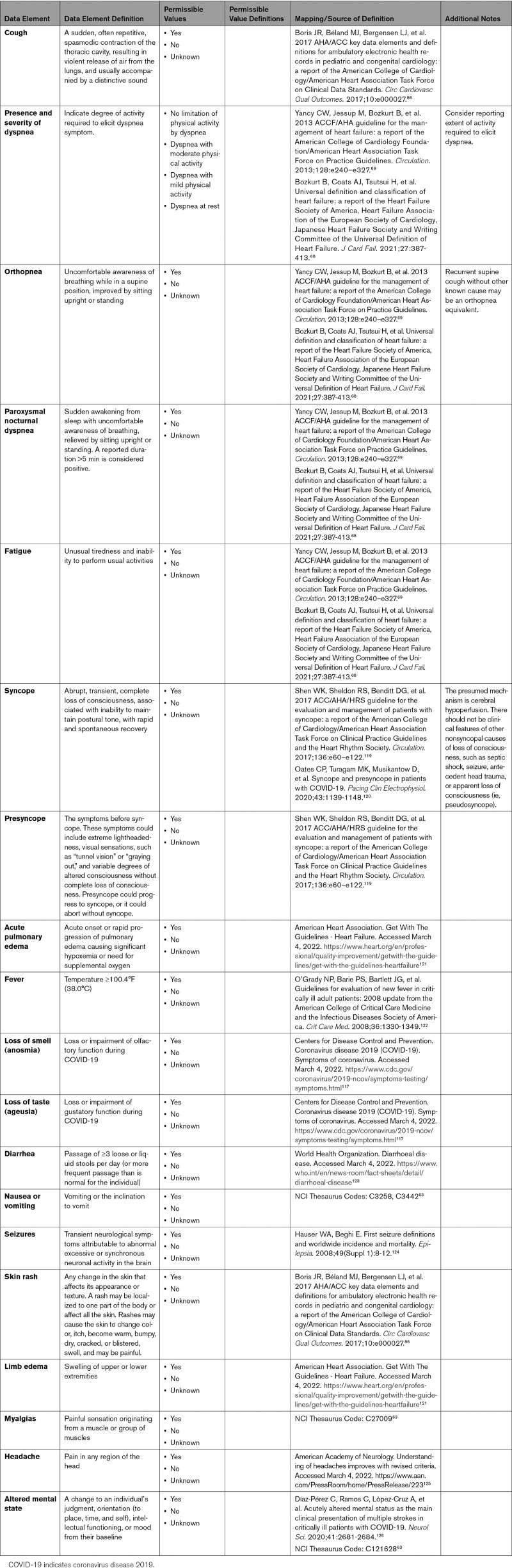

3.5. Symptoms and Signs

Appendix 6 outlines and defines common cardiovascular and noncardiovascular symptoms in patients with COVID-19, as well as an abbreviated list of physical examination findings. Symptom data elements may be derived from structured variables within the EHR (eg, chief complaint or problem list), as components of patient-reported outcomes in applied survey instruments, or as free text within clinical source documents. Because COVID-19 physical examination findings are less uniformly captured, this list focuses on signs related to potential acute cardiovascular complications from COVID-19. Future research on the postacute COVID-19 syndrome will elucidate important persistent or postacute symptoms and signs of relevance.

Although the signs and symptoms of SARS-CoV-2 infection in children may be similar to those in adults, many children are asymptomatic or may have only a few symptoms. The most common signs and symptoms of COVID-19 in hospitalized children are fever, nausea/vomiting, cough, shortness of breath, and upper respiratory symptoms.3 Although the true incidence of asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection is unknown, asymptomatic infection was reported in up to 45% of children who underwent surveillance testing at the time of hospitalization for a non–COVID-19 indication.3 SARS-CoV-2 has been associated with a potentially severe inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) and young adults (MIS-A) (Appendix 3).

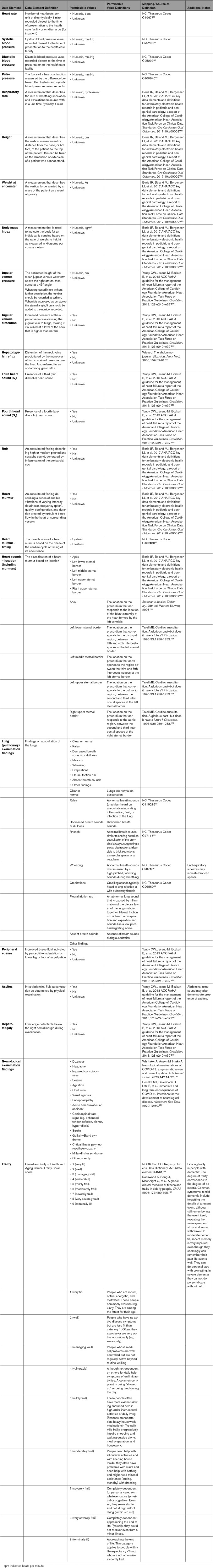

3.6. Diagnostic Procedures

As discussed previously, COVID-19 may result in a number of cardiovascular complications. The approach to these complications can involve a number of standard diagnostic procedures. Laboratory testing, including cardiac troponin, natriuretic peptide levels, complete metabolic profile, blood cell counts, coagulation parameters, and inflammatory biomarkers, can be helpful. Electrocardiography is used to identify rhythm and conduction abnormalities. Echocardiography is the most common means of assessing left ventricular ejection fraction, right ventricular function, wall motion abnormalities, and pulmonary artery systolic pressure. Other imaging procedures such as MRI may be used to assess myocardial involvement (ie, myocarditis, myocardial wall edema, myocardial fibrosis and scar), as well as other structural abnormalities and ventricular function. Several imaging techniques, including computed tomography (CT), nuclear, and coronary angiography, may be used to evaluate for obstructive coronary disease. Coronary angiography can be used to evaluate for ACS. Chest x-ray is first line for evaluating acute lung processes, and chest CT angiography may be used to further define or to evaluate for pulmonary embolus. Right heart catheterization may be used to diagnose cardiogenic shock, evaluate filling pressures, or evaluate pulmonary pressures. Venous and arterial thromboses are known to occur and can often be identified by ultrasonography, vascular, or nuclear imaging. In the case of arterial thrombosis and stroke, CT and MRI are used to define the extent and nature (ischemic vs. hemorrhagic). Appendix 7 summarizes the more common diagnostic procedures and lists standard data elements that describe the diagnostic procedures and potential findings.

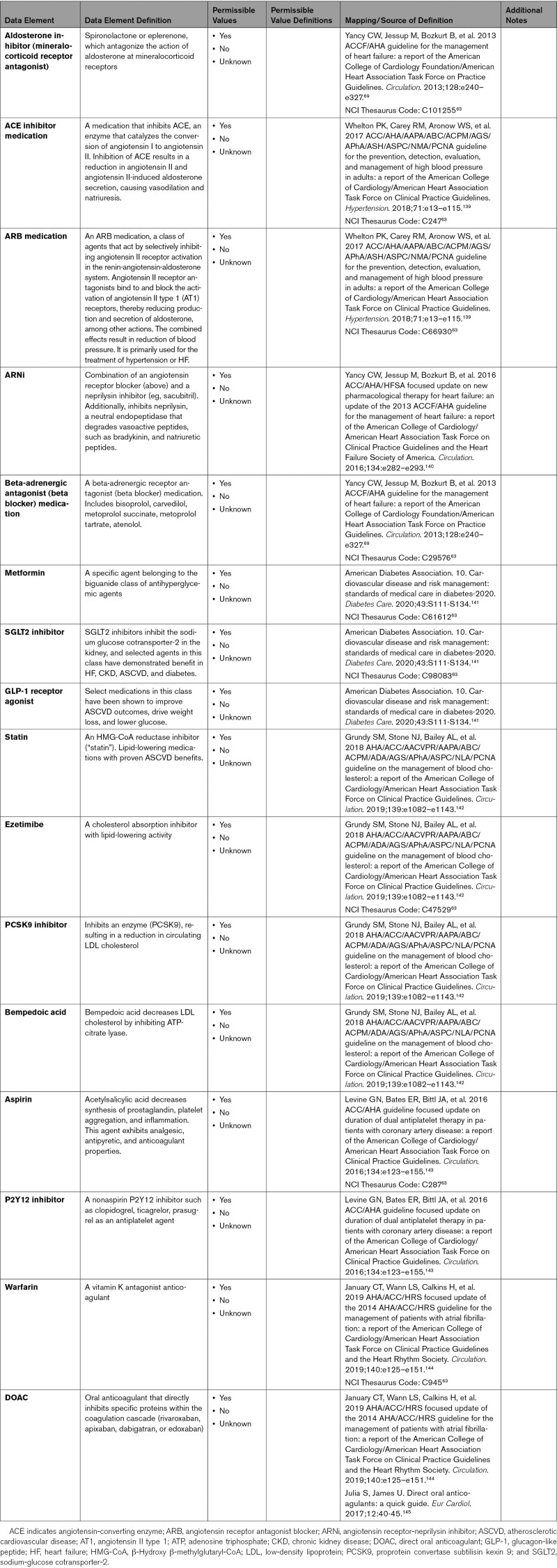

3.7. Pharmacological Therapy

A growing body of available evidence primarily supports the continuation of traditional cardiovascular therapies, including ACE inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs).22-25 These agents, as well as most other cardiovascular therapeutics, do not appear to confer an increased risk of acquiring SARS-CoV-2 infection.26,27 Large multicenter studies have demonstrated no difference in infection or mortality associated with ACE inhibitors, ARB, or any other cardiovascular therapies (antihypertensives in most cases) when continued after development of COVID-19.22-24 Appendix 8A summarizes the more common cardiovascular therapies and provides definitions for their associated data elements.

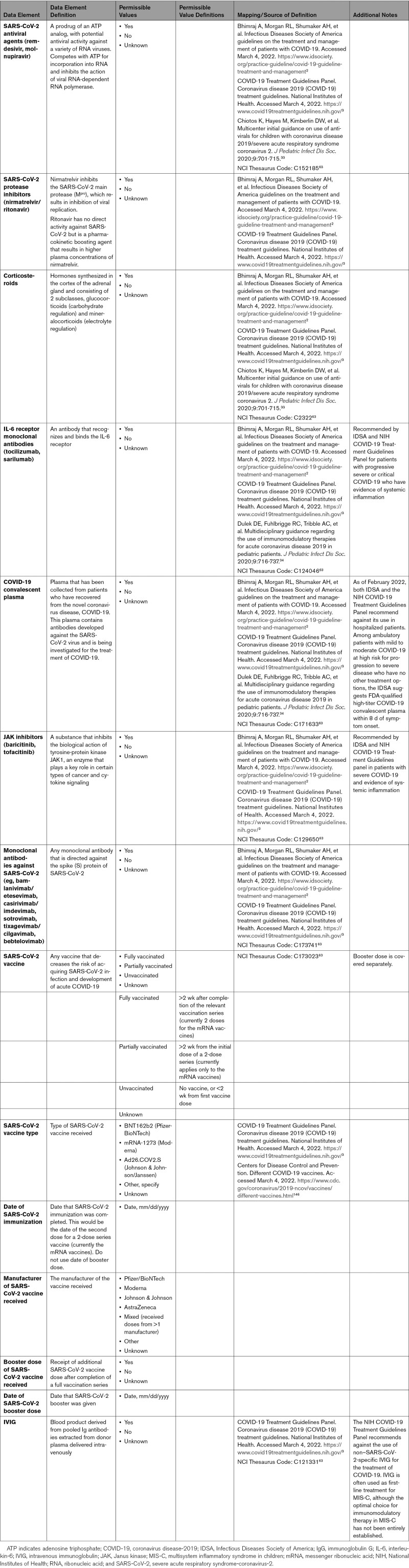

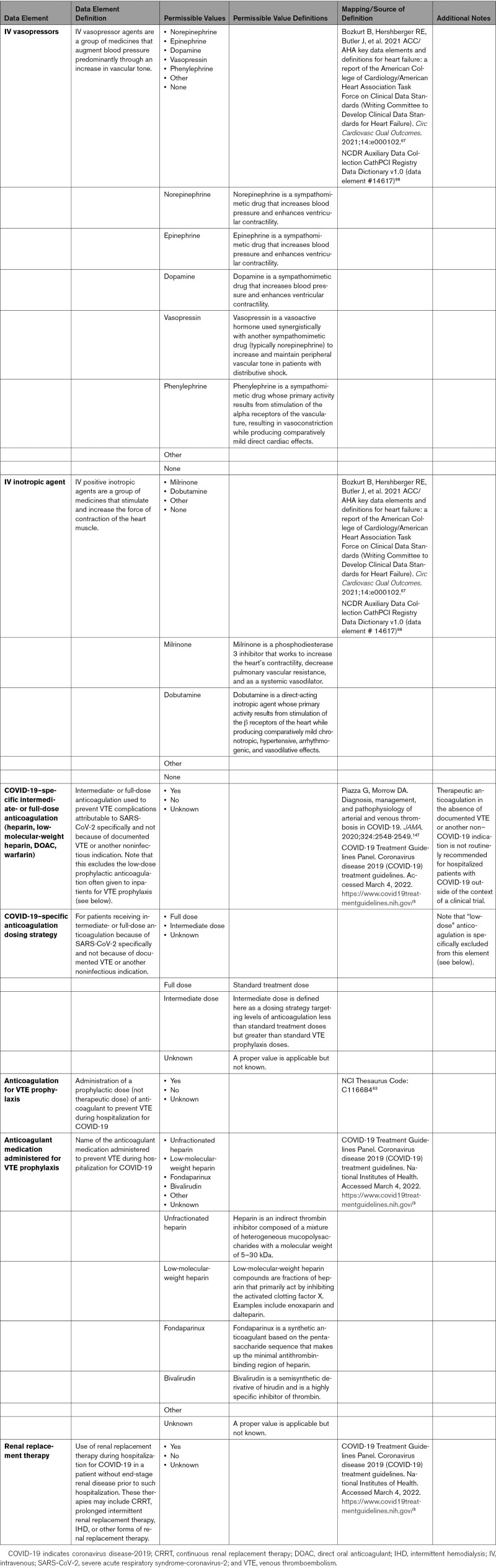

The clinical manifestations of COVID-19 can range from asymptomatic or mild respiratory disease to severe, life-threatening respiratory and hemodynamic failure. Supportive therapies are a common part of the management strategy for treatment of COVID-19. In addition to therapies used for direct antiviral activity (eg, remdesivir), other interventions (eg, proning) or medications without direct antiviral activity (eg, steroids) can be used in selected patients to decrease the morbidity and mortality associated with COVID-19. In cases of cardiogenic shock and low cardiac output associated with COVID-19, intravenous inotropic and vasopressor agents can be administered as supportive therapies. COVID-19 is also associated with a prothrombotic state and an increased incidence of thromboembolic disease.28 Prophylactic anticoagulation against venous thromboembolism is recommended.29 Therapeutic anticoagulation needs to be individualized. In critically ill patients with COVID-19, an initial strategy of therapeutic-dose anticoagulation with heparin did not result in a greater probability of survival to hospital discharge or a greater number of days free of cardiovascular or respiratory organ support than did usual-care pharmacological thromboprophylaxis.30 However, in noncritically ill patients with COVID-19, an initial strategy of therapeutic-dose anticoagulation with heparin increased the probability of survival to hospital discharge with reduced use of cardiovascular or respiratory organ support compared with usual-care thromboprophylaxis.31,32 The management of COVID-19 from the standpoint of antiviral and anti-inflammatory agents continues to evolve as new insights are discovered. In addition, although certain supportive strategies have now been shown to be effective in addressing the exaggerated inflammatory response and uncontrolled cytokine release, this remains an ongoing area of active study. Appendix 8C briefly summarizes these supportive therapies and provides definitions for their associated data elements.

Guidance for the treatment of COVID-19 in children is mostly extrapolated from recommendations for adults with COVID-19.33,34 High-quality studies, including randomized trials, are urgently needed in children and in other special populations.3 With emerging new variants of SARS-CoV-2, further studies will be needed to better understand the epidemiology, prevention, and treatment of COVID-19.

3.8. Preventive, Therapeutic, and Supportive Procedures for COVID-19

COVID-19 vaccinations have been demonstrated to be highly effective and safe in tested populations and confer protection against COVID-19.35,36 As of February 2022, the CDC recommends vaccination for everyone ≥5 years of age. Vaccination prevents not only COVID-19 but also potential cardiovascular complications related to COVID-19.37,38 In addition to vaccinations, wearing face masks, physical distancing, hand hygiene, and compliance with public health guidelines are effective in reducing spread of COVID-19.39-42

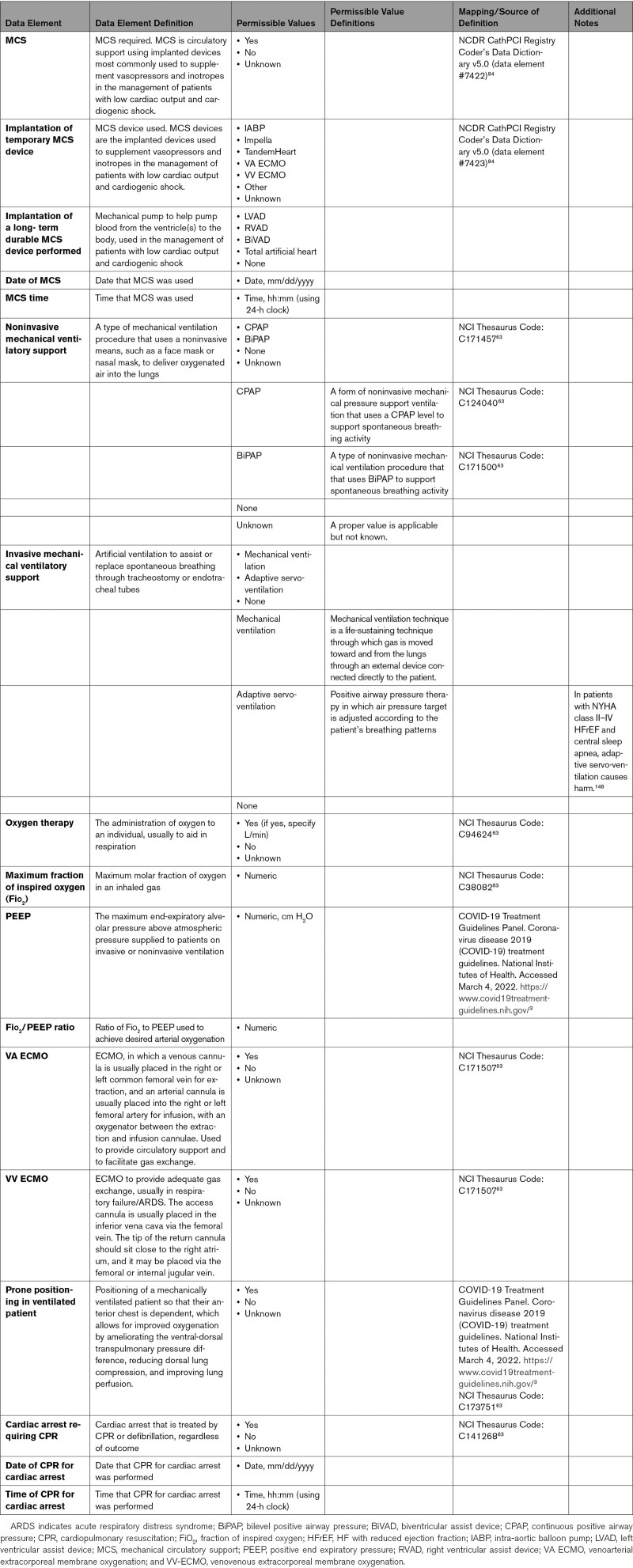

Comprehensive and reliable capture of data elements pertinent to therapeutic procedures in patients with COVID-19 is important to monitor and assess quality of care of these patients with the goal to improve their outcomes. These include but are not limited to data elements pertinent to ventilation and circulatory support, percutaneous interventional therapies, and electrophysiological procedures (Appendix 9).

Some patients with COVID-19 may experience severe cardiopulmonary complications, which can include acute respiratory distress syndrome, ACS, cardiomyopathy, acute congestive heart failure, cardiogenic shock, isolated respiratory failure, malignant ventricular arrhythmias, and cardiopulmonary arrest.43 Ventilatory support may range from noninvasive support to mechanical support, depending on severity of hypoxia. COVID-19 can result in renal injury attributable to systemic inflammation, multiorgan failure, and massive release of inflammatory cytokines, resulting in tubular and glomerular cell damage.44 Renal replacement therapy can be considered supportive in those patients without antecedent end-stage kidney disease, for whom these therapies are considered temporary. Some patients may have concomitant cardiogenic shock necessitating mechanical circulatory support, such as intra-aortic balloon pumps to more advanced percutaneous ventricular assist devices, such as Impella or TandemHeart, which unload the left ventricle directly or upstream from the left atrium.45 Patients with cardiogenic shock unresponsive to vasoactive therapies may require a circulatory support device, such as venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO). In specialized centers, ECMO devices may be used to provide adequate oxygenation (venovenous ECMO) or cardiac circulatory support (venoarterial ECMO) in patients with advanced cardiac and cardiopulmonary failure.45

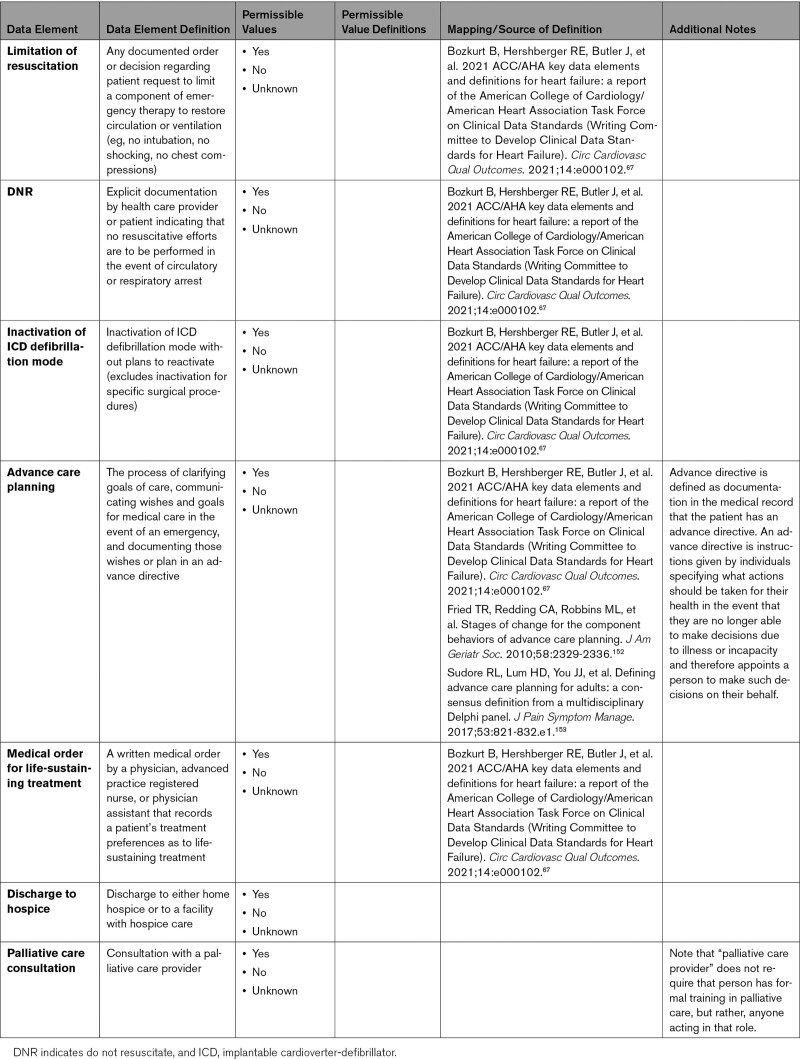

3.9. End-of-Life Management

Patients who experience COVID-19 can have life-threatening conditions attributable to respiratory, cardiovascular, and multisystem organ failure. Decisions are often made regarding escalation (and de-escalation) of therapies based on clinical course, probability of survival, and the possibility and severity of residual deficits after recovery from the acute illness. Patients who were healthy prior to COVID-19 may have different perceptions and needs about goals of care than patients with preexisting CVD. Advance care planning with the patient or family is recommended to clarify patient preferences and goals of care. Advance care planning should include advance directives and explicit documentation by health care providers regarding preferences for resuscitation and treatment preferences. For patients with severe illness, limited probability of recovery to an acceptable functional status, or poor prognosis, multidisciplinary care coordination with involvement of palliative care providers and social workers in tandem with the primary team is important. Appendix 10 provides data elements for end-of-life management.

ACC/AHA Task Force on Clinical Data Standards

Hani Jneid, MD, FACC, FAHA, Chair; Bruce E. Bray, MD, FACC, Chair-Elect; Faraz S. Ahmad, MD, MS, FACC; Deepak L. Bhatt, MD, MPH, FACC, FAHA*; Jeffrey R. Boris, MD, FACC; Mauricio G. Cohen, MD, FACC; Monica Colvin, MD, MS, FAHA; Thomas C. Hanff, MD, MSCE; Nasrien E. Ibrahim, MD, FACC, FAHA; Corrine Y. Jurgens, PhD, RN, ANP, FAHA; Dhaval Kolte, MD, PhD, FACC; Arnav Kumar, MBBS*; Nidhi Madan, MD, MPH*; Amgad N. Makaryus, MD, FACC*; Paul Muntner, PhD, FAHA; Kevin S. Shah, MD, FACC*; April W. Simon, RN, MSN; Nadia R. Sutton, MD, MPH, FACC; Anne Marie Valente, MD, FACC, FAHA

*Former Task Force member; current member during the writing effort.

Presidents and Staff

American College of Cardiology

Edward T.A. Fry, MD, FACC, President

Cathleen C. Gates, Chief Executive Officer

Richard J. Kovacs, MD, MACC, Chief Medical Adviser

MaryAnne Elma, MPH, Senior Director, Enterprise Content and Digital Strategy

Grace D. Ronan, Team Leader, Clinical Policy Publications

Leah Patterson, Project Manager, Clinical Content Development

American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association

Abdul R. Abdullah, MD, Director, Guideline Science and Methodology

American Heart Association

Donald M. Lloyd-Jones, MD, ScM, FAHA, President

Nancy Brown, Chief Executive Officer

Mariell Jessup, MD, FAHA, Chief Science and Medical Officer

Radhika Rajgopal Singh, PhD, Senior Vice President, Office of Science and Medicine

Cammie Marti, MPH, PhD, Science and Medicine Advisor, Office of Science, Medicine and Health

Jody Hundley, Production and Operations Manager, Scientific Publications, Office of Science Operations

Appendix 1. Author Relationships With Industry and Other Entities (Relevant)—2022 AHA/ACC Key Data Elements and Definitions for Cardiovascular and Noncardiovascular Complications of COVID-19

Appendix 2. Reviewer Relationships With Industry and Other Entities (Comprehensive)—2022 AHA/ACC Key Data Elements and Definitions for Cardiovascular and Noncardiovascular Complications of COVID-19 (August 2021)

Appendix 3. COVID-19 Diagnosis

Appendix 4. COVID-19 Cardiovascular Complications

A. Acute Cardiovascular Complications Related to COVID-19 Infection

Appendix 4. Continued: B. Physical Examination

Appendix 4. Continued: C. Cardiovascular Mortality During Acute COVID-19 Infection

Appendix 5. COVID-19 Noncardiovascular Complications

Appendix 6. Symptoms and Signs

A. Current Symptoms and Signs: Clinical Symptoms

Appendix 6. Continued: B. Physical Examination

Appendix 7. Diagnostic Procedures

Appendix 8. Pharmacological Therapy

A. Therapies for Preexisting Cardiovascular Disease (Patient Taking Prior to Admission)

Appendix 8. Continued: B. Therapies for COVID-19

Appendix 8. Continued: C. Therapies for Supportive Care During COVID-19 Infection

Appendix 9. Therapeutic and Supportive Procedures for COVID-19

A. Mechanical Support

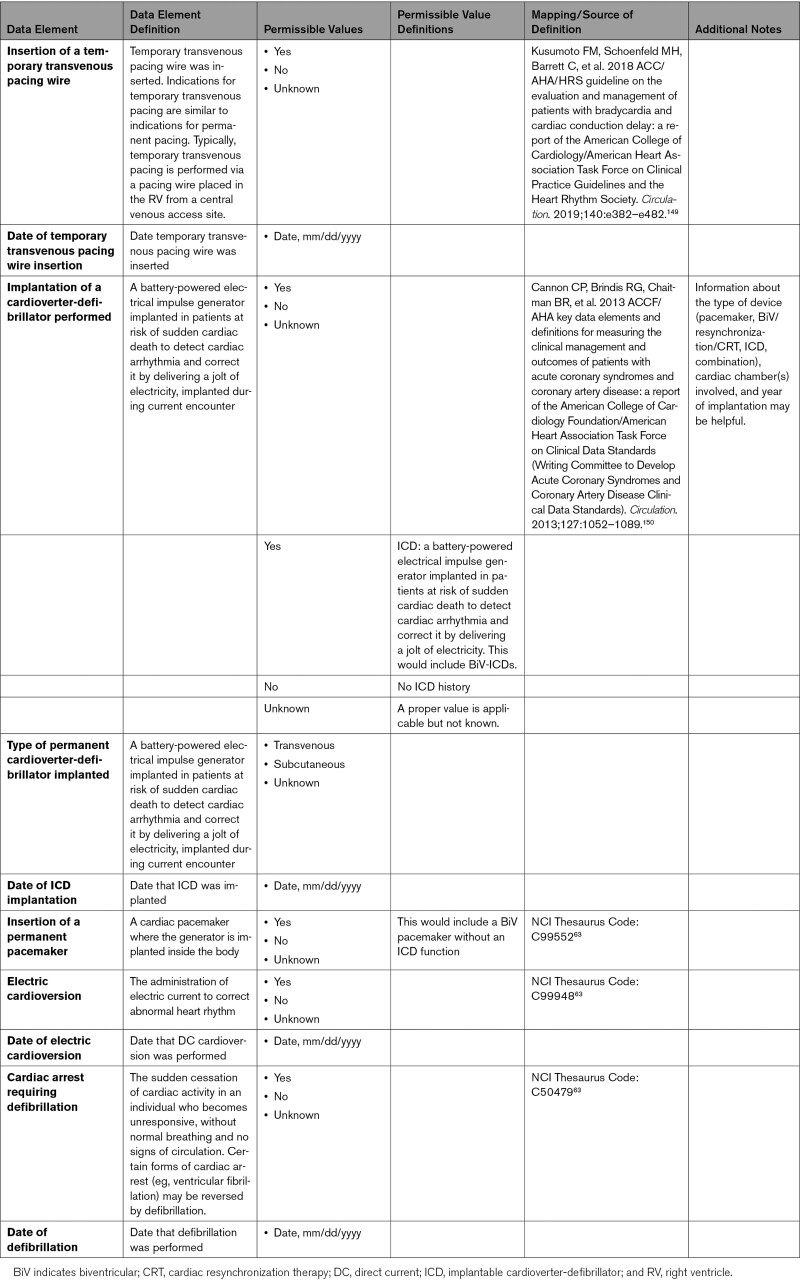

Appendix 9. Continued: B. Electrophysiological Procedures

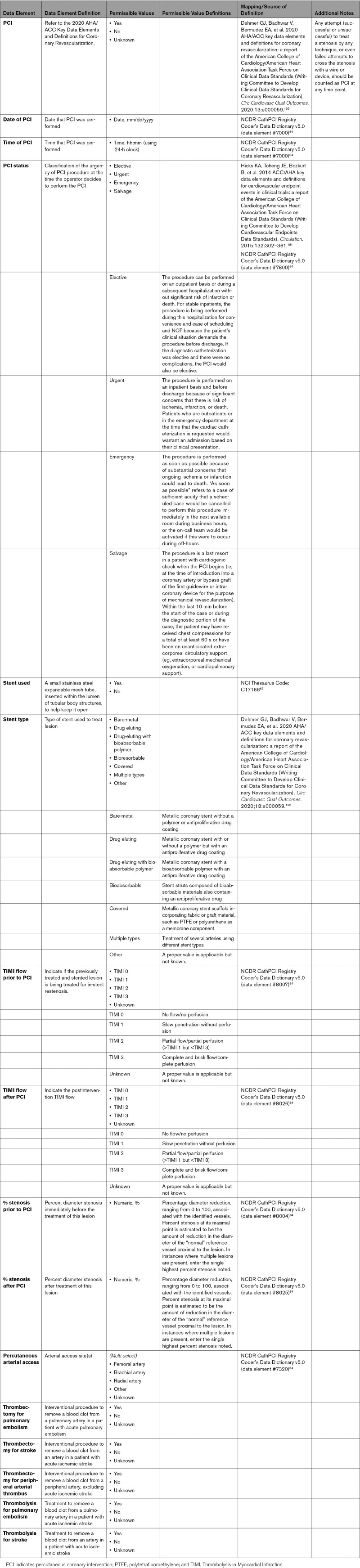

Appendix 9. Continued: C. Invasive Coronary/Vascular/Neurovascular Revascularization Treatment

Appendix 10. End-of-Life Management

Footnotes

Task Force liaison.

ACC/AHA staff.

ACC/AHA Task Force on Clinical Data Standards Members, see page 548.

The American Heart Association requests that this document be cited as follows: Bozkurt B, Das SR, Addison D, Gupta A, Jneid H, Khan SS, Koromia GA, Kulkarni PA, LaPoint K, Lewis EF, Michos ED, Peterson PN, Turagam MK, Wang TY, Yancy CW. 2022 AHA/ACC key data elements and definitions for cardiovascular and noncardiovascular complications of COVID-19: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Data Standards. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2022;15:e000111. doi: 10.1161/HCQ.0000000000000111

This document was approved by the American College of Cardiology Clinical Policy Approval Committee and the American Heart Association Science Advisory and Coordinating Committee in February 2022, and the American Heart Association Executive Committee in April 2022.

Supplemental materials are available with this article at https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/suppl/10.1161/HCQ.0000000000000111.

This article has been copublished in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

Copies: This document is available on the websites of the American Heart Association (professional.heart.org) and the American College of Cardiology (www.acc.org). A copy of the document is also available at https://professional.heart.org/statements by selecting the “Guidelines & Statements” button. To purchase additional reprints, call 215-356-2721 or email Meredith.Edelman@wolterskluwer.com.

The expert peer review of AHA-commissioned documents (eg, scientific statements, clinical practice guidelines, systematic reviews) is conducted by the AHA Office of Science Operations. For more on AHA statements and guidelines development, visit https://professional.heart.org/statements. Select the “Guidelines & Statements” drop-down menu near the top of the webpage, then click “Publication Development.”

Permissions: Multiple copies, modification, alteration, enhancement, and/or distribution of this document are not permitted without the express permission of the American Heart Association. Instructions for obtaining permission are located at https://www.heart.org/permissions. A link to the “Copyright Permissions Request Form” appears in the second paragraph (https://www.heart.org/en/about-us/statements-and-policies/copyright-request-form).

References

- 1.Hendel RC, Bozkurt B, Fonarow GC. et al. ACC/AHA 2013 methodology for developing clinical data standards: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Data Standards. Circulation. 2014;129:2346–2357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bhimraj A, Morgan RL, Shumaker AH, et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America guidelines on the treatment and management of patients with COVID-19. Accessed March 4, 2022. https://www.idsociety.org/practice-guideline/covid-19-guideline-treatment-and-management [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.COVID-19 Treatment Guidelines Panel. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) treatment guidelines. National Institutes of Health. Accessed March 4, 2022. https://www.covid19treatmentguidelines.nih.gov/ [PubMed]

- 4.National Cardiovascular Data Registry. Accessed March 4, 2022. https://cvquality.acc.org/NCDR-Home

- 5.American Heart Association COVID-19 CVD Registry. Accessed March 4, 2022. https://www.heart.org/en/professional/quality-improvement/covid-19-cvd-registry

- 6.Havranek EP, Mujahid MS, Barr DA, et al. Social determinants of risk and outcomes for cardiovascular disease: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2015;132:873–898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). 2020 interim case definition, approved August 5, 2020. Accessed March 4, 2022. https://ndc.services.cdc.gov/case-definitions/coronavirus-disease-2019-2020-08-05/

- 8.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Investigative criteria for suspected cases of SARS-CoV-2 reinfection (ICR). Accessed March 4, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/php/invest-criteria.html

- 9.Harrison SL, Buckley BJR, Rivera-Caravaca JM, et al. Cardiovascular risk factors, cardiovascular disease, and COVID-19: an umbrella review of systematic reviews. Eur Heart J Qual Care Clin Outcomes. 2021;7:330–339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hendren NS, Drazner MH, Bozkurt B, et al. Description and proposed management of the acute COVID-19 cardiovascular syndrome. Circulation. 2020;141:1903–1914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Greenhalgh T, Knight M, A’Court C, et al. Management of post-acute covid-19 in primary care. BMJ. 2020;370:m3026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shah W, Hillman T, Playford ED, et al. Managing the long term effects of covid-19: summary of NICE, SIGN, and RCGP rapid guideline. BMJ. 2021;372:n136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nalbandian A, Sehgal K, Gupta A, et al. Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome. Nat Med. 2021;27:601–615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carfì A, Bernabei R, Landi F. Persistent symptoms in patients after acute COVID-19. JAMA. 2020;324:603–605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carvalho-Schneider C, Laurent E, Lemaignen A, et al. Follow-up of adults with noncritical COVID-19 two months after symptom onset. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2020;27:258–263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang C, Huang L, Wang Y, et al. 6-month consequences of COVID-19 in patients discharged from hospital: a cohort study. Lancet. 2021;397:220–232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McElvaney OJ, McEvoy NL, McElvaney OF, et al. Characterization of the inflammatory response to severe COVID-19 illness. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;202:812–821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sungnak W, Huang N, Bécavin C, et al. SARS-CoV-2 entry factors are highly expressed in nasal epithelial cells together with innate immune genes. Nat Med. 2020;26:681–687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tang N, Li D, Wang X, et al. Abnormal coagulation parameters are associated with poor prognosis in patients with novel coronavirus pneumonia. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18:844–847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Puntmann VO, Carerj ML, Wieters I, et al. Outcomes of cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging in patients recently recovered from coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). JAMA Cardiol. 2020;5:1265–1273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu PP, Blet A, Smyth D, et al. The science underlying COVID-19: implications for the cardiovascular system. Circulation. 2020;142:68–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mehta N, Kalra A, Nowacki AS, et al. Association of use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers with testing positive for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). JAMA Cardiol. 2020;5:1020–1026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reynolds HR, Adhikari S, Pulgarin C, et al. Renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors and risk of Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:2441–2448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lopes RD, Macedo AVS, de Barros ESPGM, et al. Effect of discontinuing vs continuing angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin ii receptor blockers on days alive and out of the hospital in patients admitted with COVID-19: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2021;325:254–264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cohen JB, Hanff TC, William P, et al. Continuation versus discontinuation of renin-angiotensin system inhibitors in patients admitted to hospital with COVID-19: a prospective, randomised, open-label trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2021;9:275–284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fernández-Ruiz I. RAAS inhibitors do not increase the risk of COVID-19. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2020;17:383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ren L, Yu S, Xu W, et al. Lack of association of antihypertensive drugs with the risk and severity of COVID-19: a meta-analysis. J Cardiol. 2021;77:482–491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bellosta R, Luzzani L, Natalini G, et al. Acute limb ischemia in patients with COVID-19 pneumonia. J Vasc Surg. 2020;72:1864–1872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thachil J, Tang N, Gando S, et al. ISTH interim guidance on recognition and management of coagulopathy in COVID-19. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18:1023–1026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goligher EC, Bradbury CA, McVerry BJ, et al. Therapeutic anticoagulation with heparin in critically ill patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:777–789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lawler PR, Goligher EC, Berger JS, et al. Therapeutic anticoagulation with heparin in noncritically ill patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:790–802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lemos ACB, do Espírito Santo DA, Salvetti MC, et al. Therapeutic versus prophylactic anticoagulation for severe COVID-19: a randomized phase II clinical trial (HESACOVID). Thromb Res. 2020;196:359–366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chiotos K, Hayes M, Kimberlin DW, et al. Multicenter initial guidance on use of antivirals for children with coronavirus disease 2019/severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2020;9:701–715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dulek DE, Fuhlbrigge RC, Tribble AC, et al. Multidisciplinary guidance regarding the use of immunomodulatory therapies for acute coronavirus disease 2019 in pediatric patients. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2020;9:716–737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Polack FP, Thomas SJ, Kitchin N, et al. Safety and efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2603–2615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Baden LR, El Sahly HM, Essink B, et al. Efficacy and safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:403–416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bozkurt B, Kamat I, Hotez PJ. Myocarditis with COVID-19 mRNA vaccines. Circulation. 2021;144:471–484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Driggin E, Maddox TM, Ferdinand KC, et al. ACC health policy statement on cardiovascular disease considerations for COVID-19 vaccine prioritization: a report of the American College of Cardiology Solution Set Oversight Committee. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;77:1938–1948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Howard J, Huang A, Li Z, et al. An evidence review of face masks against COVID-19. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021;118:e2014564118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brooks JT, Butler JC. Effectiveness of mask wearing to control community spread of SARS-CoV-2. JAMA. 2021;325:998–999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Makhni S, Umscheid CA, Soo J, et al. Hand hygiene compliance rate during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Intern Med. 2021;181:1006–1008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nelson TL, Fosdick BK, Biela LM, et al. Association between COVID-19 exposure and self-reported compliance with public health guidelines among essential employees at an institution of higher education in the US. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4:e2116543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Krittanawong C, Kumar A, Hahn J, et al. Cardiovascular risk and complications associated with COVID-19. Am J Cardiovasc Dis. 2020;10:479–489. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dellepiane S, Marengo M, Cantaluppi V. Detrimental cross-talk between sepsis and acute kidney injury: new pathogenic mechanisms, early biomarkers and targeted therapies. Crit Care. 2016;20:61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gupta AK, Jneid H, Addison D, et al. Current perspectives on coronavirus disease 2019 and cardiovascular disease: a white paper by the JAHA editors. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9:e017013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Appendix A - glossary of key terms. Accessed March 4, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/php/contact-tracing/contact-tracing-plan/appendix.html#Key-Terms

- 47.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. What we know about quarantine and isolation. Accessed March 4, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/if-you-are-sick/quarantine-isolation-background.html

- 48.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Ending isolation and precautions for adults with COVID-19: interim guidance. Accessed March 4, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/duration-isolation.html

- 49.World Health Organization. A clinical case definition of post COVID-19 condition by a Delphi consensus, 6 October 2021. Accessed March 4, 2022. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-nCoV-Post_COVID-19_condition-Clinical_case_definition-2021.1

- 50.Amenta EM, Spallone A, Rodriguez-Barradas MC, et al. Postacute COVID-19: an overview and approach to classification. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2020;7:ofaa509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Datta SD, Talwar A, Lee JT. A proposed framework and timeline of the spectrum of disease due to SARS-CoV-2 infection: illness beyond acute infection and public health implications. JAMA. 2020;324:2251–2252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.National Institutes of Health. NIH launches new initiative to study “Long COVID.” Accessed March 4, 2022. https://www.nih.gov/about-nih/who-we-are/nih-director/statements/nih-launches-new-initiative-study-long-covid

- 53.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. COVID-19 rapid guideline: managing the long-term effects of COVID-19. Accessed March 4, 2022. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng188/resources/covid19-rapid-guideline-managing-the-longterm-effects-of-covid19-pdf-51035515742 [PubMed]

- 54.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Information for healthcare providers about multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C). Accessed March 4, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/mis-c/hcp/

- 55.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in adults (MIS-A). Case definition information for healthcare providers. Accessed March 4, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/mis/mis-a/hcp.html

- 56.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) 2021 case definition. Accessed March 4, 2022. https://ndc.services.cdc.gov/case-definitions/coronavirus-disease-2019-2021/

- 57.Bai L, Zhao Y, Dong J, et al. Coinfection with influenza A virus enhances SARS-CoV-2 infectivity. Cell Res. 2021;31:395–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Belongia EA, Osterholm MT. COVID-19 and flu, a perfect storm. Science. 2020;368:1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lansbury L, Lim B, Baskaran V, et al. Co-infections in people with COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Infect. 2020;81:266–275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rubin R. What happens when COVID-19 collides with flu season? JAMA. 2020;324:923–925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Su S, Liu Z, Jiang S. Double insult: flu bug enhances SARS-CoV-2 infectivity. Cell Res. 2021;31:491–492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. SARS-CoV-2 variant classifications and definitions. Accessed March 4, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/variants/variant-info.html

- 63.National Cancer Institute. NCI Thesaurus. Accessed March 4, 2022. https://ncit.nci.nih.gov/ncitbrowser/

- 64.Thygesen K, Alpert JS, Jaffe AS, et al. Fourth universal definition of myocardial infarction (2018). Circulation. 2018;138:e618–e651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kindermann I, Barth C, Mahfoud F, et al. Update on myocarditis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59:779–792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ferreira VM, Schulz-Menger J, Holmvang G, et al. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance in nonischemic myocardial inflammation: expert recommendations. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72:3158–3176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bozkurt B, Hershberger RE, Butler J. et al. 2021 ACC/AHA key data elements and definitions for heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology/ American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Data Standards (Writing Committee to Develop Clinical Data Standards for Heart Failure). Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2021;14:e000102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bozkurt B, Coats AJ, Tsutsui H, et al. Universal definition and classification of heart failure: a report of the Heart Failure Society of America, Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology, Japanese Heart Failure Society and Writing Committee of the Universal Definition of Heart Failure. J Card Fail. 2021;27:387–413. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2013;128:e240–e327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.O’Gallagher K, Kanyal R, Sado DM, et al. COVID-19 myopericarditis. Accessed March 4, 2022. https://www.acc.org/latest-in-cardiology/articles/2020/09/25/17/22/covid-19-myopericarditis

- 71.Chiabrando JG, Bonaventura A, Vecchié A, et al. Management of acute and recurrent pericarditis: JACC state-of-the-art review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75:76–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Turagam MK, Musikantow D, Goldman ME, et al. Malignant arrhythmias in patients with COVID-19: incidence, mechanisms, and outcomes. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2020;13:e008920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Musikantow DR, Turagam MK, Sartori S, et al. Atrial fibrillation in patients hospitalized with COVID-19: incidence, predictors, outcomes and comparison to influenza. J Am Coll Cardiol EP. 2021;7:1120–1130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.McNamara RL, Brass LM, Drozda JP, Jr, et al. ACC/AHA key data elements and definitions for measuring the clinical management and outcomes of patients with atrial fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Data Standards (Writing Committee to Develop Data Standards on Atrial Fibrillation). Circulation. 2004;109:3223–3243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Chinitz JS, Goyal R, Harding M, et al. Bradyarrhythmias in patients with COVID-19: marker of poor prognosis? Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2020;43:1199–1204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bikdeli B, Madhavan MV, Jimenez D, et al. COVID-19 and thrombotic or thromboembolic disease: implications for prevention, antithrombotic therapy, and follow-up: JACC state-of-the-art review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75:2950–2973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Poissy J, Goutay J, Caplan M, et al. Pulmonary embolism in patients with COVID-19: awareness of an increased prevalence. Circulation. 2020;142:184–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Shah S, Shah K, Patel SB, et al. Elevated D-dimer levels are associated with increased risk of mortality in coronavirus disease 2019: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cardiol Rev. 2020;28:295–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sethi SS, Zilinyi R, Green P, et al. Right ventricular clot in transit in COVID-19: implications for the pulmonary embolism response team. J Am Coll Cardiol Case Rep. 2020;2:1391–1396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Baran DA, Grines CL, Bailey S, et al. SCAI clinical expert consensus statement on the classification of cardiogenic shock. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2019;94:29–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Oxley TJ, Mocco J, Majidi S, et al. Large-vessel stroke as a presenting feature of Covid-19 in the young. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:e60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sacco RL, Kasner SE, Broderick JP, et al. An updated definition of stroke for the 21st century: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2013;44:2064–2089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Shakil SS, Emmons-Bell S, Rutan C, et al. Stroke among patients hospitalized with COVID-19: results from the American Heart Association COVID-19 Cardiovascular Disease Registry. Stroke. 2022;53:800–807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.National Cardiovascular Data Registry. CathPCI Registry Coder’s Data Dictionary v5.0. Accessed March 4, 2022. https://cvquality.acc.org/docs/default-source/pdfs/2019/01/10/pci-v5-0-data-dictionary-coders-rtd-07242018-uploaded-jan-10-2019.pdf?sfvrsn=b95981bf_2

- 85.Easton JD, Saver JL, Albers GW, et al. Definition and evaluation of transient ischemic attack: a scientific statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Stroke Council; Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia; Council on Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention; Council on Cardiovascular Nursing; and the Interdisciplinary Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease. Stroke. 2009;40:2276–2293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Boris JR, Béland MJ, Bergensen LJ, et al. 2017 AHA/ACC key data elements and definitions for ambulatory electronic health records in pediatric and congenital cardiology: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Data Standards. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2017;10:e000027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Bray MA, Sartain SE, Gollamudi J, et al. Microvascular thrombosis: experimental and clinical implications. Transl Res. 2020;225:105–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Gérard AO, Laurain A, Fresse A, et al. Remdesivir and acute renal failure: a potential safety signal from disproportionality analysis of the WHO safety database. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2021;109:1021–1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Rafaniello C, Ferrajolo C, Sullo MG, et al. Cardiac events potentially associated to remdesivir: an analysis from the European spontaneous adverse event reporting system. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2021;14:611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Naksuk N, Lazar S, Peeraphatdit TB. Cardiac safety of off-label COVID-19 drug therapy: a review and proposed monitoring protocol. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care. 2020;9:215–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.US Food and Drug Administration. Guideline for industry. Clinical safety data management: definitions and standards for expedited reporting (1995). Accessed March 4, 2022. https://www.fda.gov/media/71188/download

- 92.Gupta A, Madhavan MV, Sehgal K, et al. Extrapulmonary manifestations of COVID-19. Nat Med. 2020;26:1017–1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Mitrani RD, Dabas N, Goldberger JJ. COVID-19 cardiac injury: implications for long-term surveillance and outcomes in survivors. Heart Rhythm. 2020;17:1984–1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Sheldon RS, Grubb BP, 2nd, Olshansky B, et al. 2015 Heart Rhythm Society expert consensus statement on the diagnosis and treatment of postural tachycardia syndrome, inappropriate sinus tachycardia, and vasovagal syncope. Heart Rhythm. 2015;12:e41–e63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Ståhlberg M, Reistam U, Fedorowski A, et al. Post-COVID-19 tachycardia syndrome: a distinct phenotype of post-acute COVID-19 syndrome. Am J Med. 2021;134:1451–1456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Vernino S, Bourne KM, Stiles LE, et al. Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS): state of the science and clinical care from a 2019 National Institutes of Health Expert Consensus Meeting - part 1. Auton Neurosci. 2021;235:102828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Bryarly M, Phillips LT, Fu Q, et al. Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome: JACC focus seminar. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73:1207–1228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.National Cardiovascular Data Registry. Auxiliary Data Collection CathPCI Registry Data Dictionary v1.0. Accessed March 4, 2022. https://cvquality.acc.org/docs/default-source/ncdr/data-collection/cathpciaux_v1-0_datadictionarycoderspecifications_rtd.pdf

- 99.Huang L, Zhao P, Tang D, et al. Cardiac involvement in patients recovered from COVID-2019 identified using magnetic resonance imaging. J Am Coll Cardiol Img. 2020;13:2330–2339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Bajaj R, Sinclair HC, Patel K, et al. Delayed-onset myocarditis following COVID-19. Lancet Respir Med. 2021;9:e32–e34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Ackermann M, Verleden SE, Kuehnel M, et al. Pulmonary vascular endothelialitis, thrombosis, and angiogenesis in Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:120–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Moghimi N, Di Napoli M, Biller J, et al. The neurological manifestations of post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2021;21:44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Clark DE, Dendy JM, Li DL, et al. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance evaluation of soldiers after recovery from symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection: a case-control study of cardiovascular post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection (CV PASC). J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2021;23:106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Oh ES, Vannorsdall TD, Parker AM. Post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection and subjective memory problems. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4:e2119335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Hicks KA, Mahaffey KW, Mehran R, et al. 2017 Cardiovascular and stroke endpoint definitions for clinical trials. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71:1021–1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Guan WJ, Ni ZY, Hu Y, et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1708–1720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Ranieri VM, Rubenfeld GD, Thompson BT, et al. Acute respiratory distress syndrome: the Berlin definition. JAMA. 2012;307:2526–2533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Haberman R, Axelrad J, Chen A, et al. Covid-19 in immune-mediated inflammatory diseases - case series from New York. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:85–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Channappanavar R, Perlman S. Pathogenic human coronavirus infections: causes and consequences of cytokine storm and immunopathology. Semin Immunopathol. 2017;39:529–539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Phipps MM, Barraza LH, LaSota ED, et al. Acute liver injury in COVID-19: prevalence and association with clinical outcomes in a large US cohort. Hepatology. 2020;72:807–817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Fix OK, Hameed B, Fontana RJ, et al. Clinical best practice advice for hepatology and liver transplant providers during the COVID-19 pandemic: AASLD expert panel consensus statement. Hepatology. 2020;72:287–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Guzik TJ, Mohiddin SA, Dimarco A, et al. COVID-19 and the cardiovascular system: implications for risk assessment, diagnosis, and treatment options. Cardiovasc Res. 2020;116:1666–1687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Connors JM, Levy JH. COVID-19 and its implications for thrombosis and anticoagulation. Blood. 2020;135:2033–2040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Jin M, Tong Q. Rhabdomyolysis as potential late complication associated with COVID-19. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26:1618–1620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Mao L, Jin H, Wang M, et al. Neurologic manifestations of hospitalized patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Neurol. 2020;77:683–690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Liotta EM, Batra A, Clark JR, et al. Frequent neurologic manifestations and encephalopathy-associated morbidity in Covid-19 patients. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2020;7:2221–2230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Symptoms of coronavirus. Accessed March 4, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/symptoms-testing/symptoms.html

- 118.Zambrano LD, Ellington S, Strid P, et al. Update: characteristics of symptomatic women of reproductive age with laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection by pregnancy status - United States, January 22-October 3, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:1641–1647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Shen WK, Sheldon RS, Benditt DG, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/HRS guideline for the evaluation and management of patients with syncope: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation. 2017;136:e60–e122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Oates CP, Turagam MK, Musikantow D, et al. Syncope and presyncope in patients with COVID-19. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2020;43:1139–1148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.American Heart Association. Get With The Guidelines-Heart Failure. Accessed March 4, 2022. https://www.heart.org/en/professional/quality-improvement/get-with-the-guidelines/get-with-the-guidelines-heart-failure

- 122.O’Grady NP, Barie PS, Bartlett JG, et al. Guidelines for evaluation of new fever in critically ill adult patients: 2008 update from the American College of Critical Care Medicine and the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:1330–1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.World Health Organization. Diarrhoeal disease. Accessed March 4, 2022. https://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/diarrhoeal-disease

- 124.Hauser WA, Beghi E. First seizure definitions and worldwide incidence and mortality. Epilepsia. 2008;49(Suppl 1):8–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.American Academy of Neurology. Understanding of headaches improves with revised criteria. Accessed March 4, 2022. https://www.aan.com/PressRoom/home/PressRelease/223

- 126.Díaz-Pérez C, Ramos C, López-Cruz A, et al. Acutely altered mental status as the main clinical presentation of multiple strokes in critically ill patients with COVID-19. Neurol Sci. 2020;41:2681–2684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Wiese J. The abdominojugular reflux sign. Am J Med. 2000;109:59–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Stedman’s Medical Dictionary. 28th ed. Wolters Kluwer; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 129.Tavel ME. Cardiac auscultation. A glorious past-but does it have a future? Circulation. 1996;93:1250–1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Whittaker A, Anson M, Harky A. Neurological manifestations of COVID-19: a systematic review and current update. Acta Neurol Scand. 2020;142:14–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Heneka MT, Golenbock D, Latz E, et al. Immediate and long-term consequences of COVID-19 infections for the development of neurological disease. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2020;12:69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Rockwood K, Song X, MacKnight C, et al. A global clinical measure of fitness and frailty in elderly people. CMAJ. 2005;173:489–495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Douglas PS, Carabello BA, Lang RM, et al. 2019 ACC/AHA/ASE key data elements and definitions for transthoracic echocardiography: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Data Standards (Writing Committee to Develop Clinical Data Standards for Transthoracic Echocardiography) and the American Society of Echocardiography. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2019;12:e000027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Cury RC, Abbara S, Achenbach S, et al. CAD-RADSTM Coronary Artery Disease - Reporting and Data System. An expert consensus document of the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography (SCCT), the American College of Radiology (ACR) and the North American Society for Cardiovascular Imaging (NASCI). J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2016;10:269–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Dehmer GJ, Badhwar V, Bermudez EA, et al. 2020 AHA/ACC key data elements and definitions for coronary revascularization: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Data Standards (Writing Committee to Develop Clinical Data Standards for Coronary Revascularization). Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2020;13:e000059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Friedrich MG, Sechtem U, Schulz-Menger J, et al. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance in myocarditis: a JACC white paper. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:1475–1487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Common data elements. Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Accessed March 4, 2022. https://www.commondataelements.ninds.nih.gov/cde_detailed_report/23564/Imaging%20Diagnostics/Assessments%20and%20Examinations/Stroke/Cardiac%20Magnetic%20Resonance%20Imaging%20%28MRI%29

- 138.Powers WJ, Rabinstein AA, Ackerson T, et al. Guidelines for the early management of patients with acute ischemic stroke: 2019 update to the 2018 guidelines for the early management of acute ischemic stroke: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2019;50:e344–e418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Hypertension. 2018;71:e13–e115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, et al. 2016 ACC/AHA/HFSA focused update on new pharmacological therapy for heart failure: an update of the 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Failure Society of America. Circulation. 2016;134:e282–e293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.American Diabetes Association. 10. Cardiovascular disease and risk management: standards of medical care in diabetes-2020. Diabetes Care. 2020;43:S111–S134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Grundy SM, Stone NJ, Bailey AL, et al. 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA guideline on the management of blood cholesterol: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2019;139:e1082–e1143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Levine GN, Bates ER, Bittl JA, et al. 2016 ACC/AHA guideline focused update on duration of dual antiplatelet therapy in patients with coronary artery disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2016;134:e123–e155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]