Abstract

Recently it was reported that methanogens of the genus Methanobrevibacter exhibit catalase activity. This was surprising, since Methanobrevibacter species belong to the order Methanobacteriales, which are known not to contain cytochromes and to lack the ability to synthesize heme. We report here that Methanobrevibacter arboriphilus strains AZ and DH1 contained catalase activity only when the growth medium was supplemented with hemin. The heme catalase was purified and characterized, and the encoding gene was cloned. The amino acid sequence of the catalase from the methanogens is most similar to that of Methanosarcina barkeri.

Methanogens are anaerobic microorganisms that form methane as the end product of their energy metabolism. They all belong to the Archaea (34, 36). Five taxonomic orders of methanogens have been identified (4): Methanococcales, Methanobacteriales, Methanomicrobiales, Methanosarcinales, and Methanopyrales. Of these, the Methanosarcinales appear to have the most metabolic capabilities, as evidenced by a larger genome with twice as many open reading frames as other methanogens (see below), by the ability to utilize a broader spectrum of substrates (4), and by the possession of cytochromes (10, 13, 19) and of other heme-containing proteins such as catalase (30). Heme proteins appear to be lacking in members of the other orders (9, 13, 19, 32)

Given that only methanogens of the Methanosarcinales are capable of synthesizing heme, it was quite a surprise when Leadbetter and Breznak (20) reported that they had found catalase-like activity in Methanobrevibacter species that colonize the peripheral microoxic region of the hindgut of termites. The methanogens, which were shown to be relatively aerotolerant, reside on or near the hindgut epithelium. Catalase-like activity was also found in an authentic strain of Methanobrevibacter arboriphilus (formerly M. arboriphilicus) (1), indicating that the catalase-like activity was not restricted to the Methanobrevibacter species adapted to the hindgut of termites.

One explanation for the findings in reference 20 could be that Methanobrevibacter species contain a nonheme catalase, such as the manganese catalase found in Thermus thermophilus (14) and lactic acid bacteria (12). This explanation was ruled out, however, by our finding, reported here, that catalase activity in M. arboriphilus strains was dependent on the presence of heme in the growth medium. We present evidence that M. arboriphilus contains a heme catalase which is formed from apoprotein synthesized by the methanogen and hemin taken up from the medium.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Organism, plasmid, phages, and chemicals.

M. arboriphilus strains AZ (DSMZ 744) and DH1 (DSMZ 1125) were from the Deutsche Sammlung von Mikroorganismen und Zellkulturen (Braunschweig, Germany). The cloning vector λZAP Express, the helper phage ExAssist, Escherichia coli strains XL1 Blue-MRF′ and XLOLR, and Pfu DNA polymerase were from Stratagene. Ampicillin, kanamycin, and 2,2′-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzthiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) diammonium salt (ABTS) were from Sigma. Synthetic oligonucleotides were obtained from MWG-Biotech. The digoxigenin labeling kit and the luminescence detection kit for nucleic acids were from Roche. All DNA-modifying enzymes were from United States Biochemicals. The Thermo Sequenase fluorescence-labeled primer cycle sequencing kit with 7-deaza-dGTP, the ALF Express DNA sequencer, fast protein liquid chromatography equipment and columns, and standard proteins for polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) and gel filtration columns were from Amersham Pharmacia Biotech.

Purification of catalases.

M. arboriphilus strains AZ and DH1 were grown autotrophically with H2 and CO2 with shaking (130 rpm) at 37°C in a 2-liter bottle sealed with a butyl rubber stopper and a plastic screw cap containing 1 liter of medium as described previously (1). The gas phase was H2-CO2 (4:1) pressurized to 150 kPa. The cells were harvested in the late exponential phase at a cell concentration of 1 g (wet mass)/liter.

Catalase was purified from 4 g (wet mass) cells of M. arboriphilus strain AZ grown in the presence of 30 μM hemin. The cells were suspended in 50 ml of 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0). The cell suspension was passed three times through a French pressure cell at 110 MPa. Cell debris was removed by centrifugation for 20 min at 25,000 × g and 4°C. The cell extract was centrifuged at 150,000 × g and 4°C for 30 min. Ammonium sulfate powder was added to the supernatant to a final concentration of 60%. The solution was incubated at 0°C for 10 min and was centrifuged at 25,000 × g at 4°C for 15 min. The supernatant was applied to a phenyl-Sepharose 26/10 column that was equilibrated with 2 M ammonium sulfate in 50 mM MOPS (morpholinepropanesulfonic acid)-KOH (pH 7.0). Catalase was eluted from the column with 500 ml of a decreasing linear gradient of ammonium sulfate (2 to 0 M). The flow rate was 4 ml/min. Fractions of 8 ml were collected. Catalase activity eluted at 0.56 to 0.40 M ammonium sulfate. The fractions containing catalase activity were combined and concentrated by filtration (30-kDa cutoff) (Millipore) and diluted with 50 mM MOPS-KOH (pH 7.0). The solution was applied to a Resource Q column (6-ml volume) that was equilibrated with 50 mM MOPS-KOH (pH 7.0). Catalase was eluted from the column with 200 ml of an increasing linear gradient of NaCl (0 to 1 M). The flow rate was 3 ml/min. Fractions of 3 ml were collected. Catalase activity was eluted at 0.33 to 0.37 M NaCl. The fractions containing catalase activity were combined and concentrated by filtration (30-kDa cutoff) and diluted with 10 mM potassium phosphate (pH 7.0). The solution was applied to a ceramic hydroxyapatite (Bio-Rad) column (1 ml) that was equilibrated with 10 mM potassium phosphate (pH 7.0). Catalase was eluted from the column with 20 ml of an increasing linear gradient of potassium phosphate (10 to 500 mM). The flow rate was 1 ml/min. Fractions of 0.4 ml were collected. Catalase activity was eluted at 150 to 250 mM potassium phosphate. The fractions containing catalase activity were combined and concentrated to 0.2 ml using a Centricon 30 microconcentrator (Millipore). The solution was applied to a Superdex 200 column (1 by 30 cm) that was equilibrated with 100 mM potassium phosphate (pH 7.0). The flow rate was 0.5 ml/min. Fractions of 0.5 ml were collected. The fractions containing catalase activity were combined and concentrated to 0.15 ml. The enzyme was routinely stored at 4°C. Under this condition, the catalase activity remained constant for at least 2 months.

Molecular properties of catalase.

Analytical gel filtration was performed by chromatography on a Superdex 200 (1- by 30-cm) column which was equilibrated with 100 mM potassium phosphate (pH 7.0). The column was calibrated by standard protein solution containing ferritin (440 kDa), catalase (bovine liver) (232 kDa), aldolase (158 kDa), ovalbumin (43 kDa), and RNase A (13.7 kDa). Native PAGE was performed using a gradient gel (4 to 15%) from Bio-Rad. Thyroglobulin (669 kDa), ferritin (440 kDa), catalase (bovine liver) (232 kDa), lactate dehydrogenase (140 kDa), and bovine serum albumin (67 kDa) were used for calibration of the gel. The molecular mass of the purified protein was determined by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization–time of flight (mass spectrometry) (MALDI-TOF [MS]) using Voyager-DERD from Applied Biosystems. The N-terminal sequence of the protein was determined on a 477 A protein-peptide sequencer from Applied Biosystems.

Determination of enzyme specific activity.

Catalase activity was routinely determined spectrophotometrically at 25°C by monitoring the decrease in absorbance at 240 nm (ɛ240 = 39.4 M−1 cm−1) of 13 mM H2O2 in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) (2, 24). One unit is defined as the amount of enzyme that catalyzes the oxidation of 1 μmol of H2O2 min−1 under the assay conditions used here. Peroxidase activity was tested spectrophotometrically at 25°C in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) with 1.0 mM H2O2 and ABTS as substrates.

Protein concentrations were determined as described in reference 5 using reagents from Bio-Rad Laboratories and bovine serum albumin as a standard.

Generation of a hybridization probe for the kat gene.

The oligonucleotides 5′-AATAAGAAGAAGTTTACTACTAATAAAGG (sense) and 5′-TCTCCTAGCATTGTGTAGTTTGTTCCTTT (antisense) were derived from the N-terminal amino acid sequence of purified catalase. The 25-μl PCR mixture contained 2.5 ng of genomic DNA of M. arboriphilus strain AZ, 1.3 U of Pfu DNA polymerase, 100 μM deoxynucleoside triphosphate, 2.0 mM MgCl2, and 0.5 μM concentrations of each of the two primers. The temperature program was 5 min at 95°C, 30 cycles of 30 s at 94°C and 1 min at 40°C, and a final step of 5 min at 72°C. The PCR product was cloned into the pCR-Blunt vector using an Invitrogen Zero Blunt PCR cloning kit. The identity of the cloned fragment was determined by DNA sequencing. The following 26-base oligonucleotide probe was designed from the PCR product: 5′-GTAATGGATGCCTGATCATTAGGTAC. The oligonucleotide was subjected to 3′ labeling with digoxigenin-dUTP following a protocol from Roche and then used for Southern hybridizations (29) of M. arboriphilus genomic DNA digested to completion with restriction endonucleases. The hybridization and washing conditions were 15 mM sodium citrate, pH 7.0, containing 150 mM NaCl and 50°C.

Cloning and sequencing of the kat gene.

The DNA from M. arboriphilus strain AZ was partially digested with the restriction enzyme Sau3AI. The DNA fragments (6 to 10 kb) were purified, and a λZAP Express library was prepared as described previously (31). The 26-base probe for kat was used to screen the library. E. coli cells were infected with packaged λZAP DNA and plated onto Luria-Bertani agar (29). Positive clones were identified by plaque hybridization. Excision and recircularization of pBK-CMV and its insert generated plasmid clones. A DNA fragment cloned into pBK-CMV vector was sequenced using the dideoxynucleotide method with fluorescence-labeled primers by MWG AG Biotech.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence of the kat gene from M. arboriphilus strain AZ is available under accession number AJ300838 in the EMBL database.

RESULTS

Cell extracts of M. arboriphilus strains AZ and DH1 grown in standard medium, which was supplemented with 0.1% yeast extract, exhibited weak catalase activity (Table 1). When hemin (30 μM) was added to the medium, the catalase activity was dramatically increased. In the case of a medium containing neither yeast extract nor hemin, no catalase activity was detected. The presence and absence of hemin in the growth medium did not have a significant effect on the growth rate and the cell concentration reached. The lag period after inoculation was, however, much more variable and generally longer when hemin was omitted. The catalase activity was associated with the soluble cell fraction. It was not sensitive to air. Therefore, the enzyme could be purified under oxic conditions.

TABLE 1.

Catalase activity in two M. arboriphilus strains grown in the absence and presence of yeast extract (0.1%) and/or hemin (30 μM)

| Strain and growth supplement | Catalase activity in cell extract (U/mg) |

|---|---|

| AZ | |

| None | <0.1 |

| Yeast extract | 9 |

| Yeast extract + hemin | 240 |

| DH1 | |

| None | <0.1 |

| Yeast extract | 7 |

| Yeast extract + hemin | 300 |

Purification.

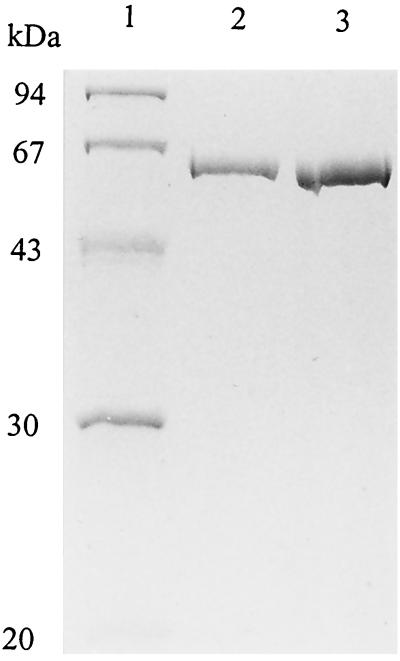

The catalase was purified in five steps to 500-fold in a 30% yield (Table 2). From 160 mg of cell extract protein, 0.1 mg of purified enzyme with a specific activity of 120,000 U/mg was obtained. Sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-PAGE of the purified enzyme revealed the presence of only one band at an apparent molecular mass of 60 kDa (Fig. 1).

TABLE 2.

Purification of catalase from M. arboriphilus strain AZ grown in the presence of hemin (30 μM)

| Fraction | Amt of protein (mg) | Activity (U) | Sp act (U/mg) | Purification (fold) | Yield (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 240,000 × g supernatant | 160 | 39,000 | 240 | 1 | 100 |

| 70% (NH4)2SO4 supernatant | 55 | 29,000 | 530 | 2 | 74 |

| Phenyl-Sepharose | 5.0 | 24,000 | 4,800 | 20 | 62 |

| Resource Q | 0.45 | 22,000 | 49,000 | 204 | 56 |

| Hydroxyapatite | 0.20 | 17,000 | 85,000 | 354 | 44 |

| Superdex 200 | 0.10 | 12,000 | 120,000 | 500 | 31 |

FIG. 1.

SDS-PAGE of purified catalase from M. arboriphilus strain AZ. Protein was separated on a 12% polyacrylamide gel and subsequently stained with Coomassie brilliant blue. Lane 1, low-molecular-mass standards (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech); lane 2, 1 μg of purified catalase; lane 3, 2 μg of purified catalase.

Molecular properties.

The purified catalase eluted from gel filtration columns (Superdex 200) with an apparent molecular mass of 260 kDa (data not shown). MALDI-TOF (MS) showed that the molecular mass of the monomer is 57.7 kDa. These data suggest that the catalase is a homotetrameric enzyme.

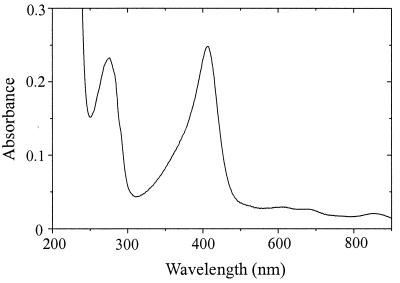

The UV/visible spectrum of the purified catalase indicated the presence of a heme prosthetic group (Fig. 2). The native enzyme had a Soret peak at 407 nm. This peak was shifted to 426 nm upon addition of 10 mM cyanide (data not shown). The prosthetic group was not reducible by 1 mM dithionite (data not shown). The ratio of absorbance at 407 nm to that at 280 nm was 1.0. These are properties of monofunctional heme catalases (6, 33).

FIG. 2.

UV/visible spectrum of catalase purified from M. arboriphilus strain AZ grown in the presence of hemin (30 μM). The solution was 30 μg of enzyme in 50 μl of 100 mM potassium phosphate, pH 7.0. The spectrum was recorded with a Zeiss Specord S10 diode array spectrophotometer; the light path was 0.3 cm.

The N-terminal amino acid sequence of the purified catalase was determined by Edman degradation: SNKKKFTTNKGIPVPNDQASITTGKGSNYTMLGDSXLTEKXAXFGXXXIP. The sequence shows similarity to the N-terminal amino acid sequence of monofunctional heme catalases, but the identity was relatively low.

Catalytic properties.

The activity of the purified catalase was routinely assayed at a H2O2 concentration of 13 mM. When the concentration was increased, the specific activity increased from 120,000 U/mg to approximately 400,000 U/mg at 60 mM H2O2. The concentration dependence between 8 and 50 mM followed the Michaelis-Menten equation: a plot of 1/v versus 1/[S] was linear (v is the reaction rate; S is the subtrate) (data not shown). At H2O2 concentrations higher than 60 mM the rate no longer increased. Fifty percent of the maximal activity was observed at a H2O2 concentration of approximately 30 mM.

The catalase activity was inhibited by cyanide and azide, with half-maximal inhibition being observed at concentrations of 80 and 1 μM, respectively.

The purified catalase did not catalyze the oxidation of ABTS by H2O2 and thus did not possess peroxidase activity (26).

Catalase-encoding gene.

From the N-terminal amino acid sequence of the purified catalase, two PCR primers were synthesized to obtain a homologous probe for the kat gene encoding the catalase. A Sau3AI gene bank from M. arboriphilus strain AZ was screened with the probe. Of 4,000 plaques, 14 were positive. A plasmid containing the gene with its flanking regions was obtained from one of the positive plaques and sequenced.

Comparison of the N-terminal amino acid sequence of the catalase determined by Edman degradation with that deduced from the gene sequence revealed the lack of the N-terminal methionine indicating posttranslational modification. The kat gene starts with an ATG codon, stops with a TGA codon, and is 1,509 bp long. The DNA G+C content was 34 mol%, and thus, it was higher than the average G+C content (25.5 mol%) of the M. arboriphilus strain AZ genome (1).

The nucleotide sequence predicts that the catalase should be composed of 502 amino acids and should have a mass of 57,507 Da, considering the lack of the N-terminal methionine. The value has to be compared with the apparent molecular mass of 57.7 kDa determined for the catalase subunit by MALDI-TOF (MS). From the amino acid sequence a pI of 6.3 was calculated. The amino acid sequence deduced from the nucleotide sequence was highly similar to those of monofunctional heme catalases (Table 3). Amino acids at the active site of the catalases were conserved in the deduced amino acid sequence.

TABLE 3.

Percent sequence identity within the conserved core region of the catalase amino acid sequencea

| Species (accession no.) | %

Identityb

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

| 1. Methanobrevibacter arboriphilus (AJ300838) | 100 | 67.1 | 59.8 | 56.6 | 60.6 | 59.4 | 54.3 | 47.9 | 36.5 |

| 2. Methanosarcina barkeri (CAA06774) | 100 | 67.7 | 66.3 | 67.4 | 66.9 | 52.6 | 50.6 | 36.3 | |

| 3. Dictyostelium discoideum (AAC36743) | 100 | 63.7 | 63.7 | 63.7 | 51.1 | 47.0 | 37.0 | ||

| 4. Drosophila melanogaster (P17336) | 100 | 75.4 | 76.3 | 50.6 | 45.1 | 37.4 | |||

| 5. Bos taurus (P00432) | 100 | 94.0 | 53.1 | 47.4 | 38.6 | ||||

| 6. Homo sapiens (P04040) | 100 | 51.1 | 46.3 | 38.6 | |||||

| 7. Glycine max (AAB88172) | 100 | 50.3 | 36.3 | ||||||

| 8. Escherichia coli (P21179) | 100 | 40.8 | |||||||

| 9. Penicillium janthinellum (P81138) | 100 | ||||||||

The sequence 2 bp upstream of the kat gene showed a ribosome binding site (AGATGATAAA) which was deduced from the 3′-terminal 16S rRNA sequence of M. arboriphilus strain DH1 (GAUCACCUCCU-3′) (The sequence was from Ribosomal Database Project II [http://www.cme.msu.edu/RDP/html/index.html].) The upstream region of the translation initiation codon (ATG) was highly AT rich (12 mol% GC in 1 kbp).

With the homologous probe used to screen for the kat gene, Southern hybridizations were performed. In each restriction digest of genomic DNA, only one band was observed, indicating that the genome of M. arboriphilus strain AZ harbors only one kat gene.

An open reading frame of 393 bp starts 34 bp downstream of the kat gene. An analysis using the BLAST search program (National Center for Biotechnology Information [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST/]) indicated that the deduced amino acid sequence of the open reading frame is significantly similar to that of the probable membrane protein from E. coli of unknown function (37). The downstream region of this open reading frame was highly AT rich (12 mol% GC in 0.4 kbp).

DISCUSSION

The results clearly indicate that M. arboriphilus strain AZ contains within its genome a kat gene which encodes a monofunctional heme catalase. Active catalase was, however, formed by the anaerobe only when hemin was present in the growth medium, indicating that M. arboriphilus cannot synthesize heme, which therefore has to be imported by the organism. The same results were obtained for M. arboriphilus strain DH1. Strain AZ has been isolated from digested sludge of an anaerobic sewage treatment plant near Zürich, Switzerland (38), and the type strain DH1 has been isolated from wet-wood cores of trees growing near Madison, Wis. (39). Hemin is predicted to be available at relatively high concentrations in both anaerobic habitats, since in anaerobic environments heme released upon degradation of heme-containing proteins is only very slowly metabolized: known pathways require molecular oxygen to initiate heme degradation (8). It is therefore very likely that both M. arboriphilus strains also synthesize active catalase in their natural environments despite the fact that they cannot synthesize heme.

The Methanobrevibacter strains RFM1, RFM2, and RFM3 isolated from the hindgut of termites are very close relatives of M. arboriphilus (20, 21). They were reported to exhibit catalase activity after growing on media predicted to contain heme from the additives yeast extract and rumen fluid. The catalase activity of strain RFM1 was determined to be 54 μmol of H2O2 decomposed per min per mg of cell extract protein (20). The specific activity was thus on the same order as that of cell extract of M. arboriphilus grown in the presence of low hemin concentrations (see Results).

This is not the first report on an organism capable of synthesizing heme catalase apoprotein but not heme. Examples include many lactic acid bacteria which, like M. arboriphilus, can grow in the absence of hemin but which form active catalase only when the growth medium is supplemented with hemin (11, 18). Haemophilus influenzae requires heme for growth and active catalase formation (3, 22), and so does Bacteroides fragilis (27). Lactic acid bacteria, H. influenzae, and B. fragilis have close relatives which can synthesize heme, indicating that this trait was lost in these organisms. The presence of a kat gene in their genome can thus be explained. Close relatives of Methanobrevibacter, however, cannot synthesize heme and do not contain heme proteins.

Sequence comparison reveals that the catalase sequence from M. arboriphilus is most similar to that of M. barkeri (Table 3). From codon usage differences, it has been deduced that the kat gene of M. barkeri is relatively new in this organism (30). A kat gene encoding a monofunctional heme catalase is not found in the genomes of Halobacterium species NRC1 (6, 25), Archaeoglobus fulgidus (16), Thermoplasma acidophilum (28), Aeropyrum pernix (15), and Sulfolobus solfataricus (http://www.cbr.nrc.ca/sulfhome/), which all can synthesize heme. Halobacterium species and A. fulgidus do contain bifunctional catalase-peroxidase enzymes (7, 16, 25), which are, however, phylogenetically not related to the monofunctional heme catalases (23). It thus appears that among the archaea the presence of heme catalase is restricted to Methanosarcina species and Methanobrevibacter species.

Where did the kat gene in Methanobrevibacter species come from? In rotten wet wood, these archaea live in close proximity to many other microorganisms, which may include cellular slime molds such as Dictyostelium. In the hindgut of termites, the close proximity of the methanogens to the epithelial cells of the insect and to the microorganisms of the intestinal flora would allow lateral gene transfer.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Max-Planck-Gesellschaft, by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, and by the Fonds der Chemischen Industrie.

Footnotes

Dedicated to Hans Trüper on the occasion of his 65th birthday.

REFERENCES

- 1.Asakawa S, Morii H, Akagawa-Matsushita M, Koga Y, Hayano K. Characterization of Methanobrevibacter arboriphilicus SA isolated from a paddy field soil and DNA-DNA hybridization among M. arboriphilicusstrains. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1993;43:683–686. . (Erratum, 44:185, 1994.) [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beers R F, Jr, Sizer I W. A spectrometric method for measuring the breakdown of hydrogen peroxide by catalase. J Biol Chem. 1952;195:133–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Biberstein E, Gills M. Catalase activity of Haemophilusspecies grown with graded amounts of hemin. J Bacteriol. 1961;81:380–384. doi: 10.1128/jb.81.3.380-384.1961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boone D R, Whitman W B, Rouvière P. Diversity and taxonomy of methanogens. In: Ferry J G, editor. Methanogenesis. New York, N.Y: Chapman & Hall; 1993. pp. 35–80. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bradford M M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown-Peterson N J, Salin M L. Purification and characterization of a mesohalic catalase from the halophilic bacterium Halobacterium halobium. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:378–384. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.2.378-384.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown-Peterson N J, Salin M L. Purification of a catalase-peroxidase from Halobacterium halobium: characterization of some unique properties of the halophilic enzyme. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:4197–4202. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.13.4197-4202.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brumm P J, Fried J, Friedmann H C. Bactobilin: blue bile pigment isolated from Clostridium tetanomorphum. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1983;80:3943–3947. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.13.3943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bult C J, White O, Olsen G J, Zhou L, Fleischmann R D, Sutton G G, Blake J A, FitzGerald L M, Clayton R A, Gocayne J D, Kerlavage A R, Dougherty B A, Tomb J F, Adams M D, Reich C I, Overbeek R, Kirkness E F, Weinstock K G, Merrick J M, Glodek A, Scott J L, Geoghagen N S M, Venter J C. Complete genome sequence of the methanogenic archaeon, Methanococcus jannaschii. Science. 1996;273:1058–1073. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5278.1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deppenmeier U, Müller V, Gottschalk G. Pathways of energy conservation in methanogenic archaea. Arch Microbiol. 1996;165:149–163. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hertel C, Schmidt G, Fischer M, Oellers K, Hammes W P. Oxygen-dependent regulation of the expression of the catalase gene katA of Lactobacillus sakeiLTH677. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:1359–1365. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.4.1359-1365.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Igarashi T, Kono Y, Tanaka K. Molecular cloning of manganese catalase from Lactobacillus plantarum. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:29521–29524. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.47.29521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jussofie A, Gottschalk G. Further studies on the distribution of cytochromes in methanogenic bacteria. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1986;37:15–18. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kagawa M, Murakoshi N, Nishikawa Y, Matsumoto G, Kurata Y, Mizobata T, Kawata Y, Nagai J. Purification and cloning of a thermostable manganese catalase from a thermophilic bacterium. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1999;362:346–355. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1998.1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kawarabayasi Y, Hino Y, Horikawa H, Yamazaki S, Haikawa Y, Jin-no K, Takahashi M, Sekine M, Baba S, Ankai A, Kosugi H, Hosoyama A, Fukui S, Nagai Y, Nishijima K, Nakazawa H, Takamiya M, Masuda S, Funahashi T, Tanaka T, Kudoh Y, Yamazaki J, Kushida N, Oguchi A, Kikuchi H. Complete genome sequence of an aerobic hyper-thermophilic crenarchaeon, Aeropyrum pernixK1. DNA Res. 1999;6:83–101. doi: 10.1093/dnares/6.2.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Klenk H P, Clayton R A, Tomb J F, White O, Nelson K E, Ketchum K A, Dodson R J, Gwinn M, Hickey E K, Peterson J D, Richardson D L, Kerlavage A R, Graham D E, Kyrpides N C, Fleischmann R D, Quackenbush J, Lee N H, Sutton G G, Gill S, Kirkness E F, Dougherty B A, McKenney K, Adams M D, Loftus B, Venter J C. The complete genome sequence of the hyperthermophilic, sulphate-reducing archaeon Archaeoglobus fulgidus. Nature. 1997;390:364–370. doi: 10.1038/37052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klotz M G, Klassen G R, Loewen P C. Phylogenetic relationships among prokaryotic and eukaryotic catalases. Mol Biol Evol. 1997;14:951–958. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a025838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Knauf H J, Vogel R F, Hammes W P. Cloning, sequence, and phenotypic expression of katA, which encodes the catalase of Lactobacillus sakeLTH677. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:832–839. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.3.832-839.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kühn W, Fiebig K, Hippe H, Mah R A, Huser B A, Gottschalk G. Distribution of cytochromes in methanogenic bacteria. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1983;20:407–410. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leadbetter J R, Breznak J A. Physiological ecology of Methanobrevibacter cuticularis sp. nov. and Methanobrevibacter curvatus sp. nov., isolated from the hindgut of the termite Reticulitermes flavipes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:3620–3631. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.10.3620-3631.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leadbetter J R, Crosby L D, Breznak J A. Methanobrevibacter filiformissp. nov., a filamentous methanogen from termite hindguts. Arch Microbiol. 1998;169:287–292. doi: 10.1007/s002030050574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Loeb M R. Ferrochelatase activity and protoporphyrin IX utilization in Haemophilus influenzae. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:3613–3615. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.12.3613-3615.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Loewen P C, Klotz M G, Hassett D J. Catalase—an “old” enzyme that continues to surprise us. ASM News. 2000;66:76–82. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nelson D P, Kiesow L A. Enthalpy of decomposition of hydrogen peroxide by catalase at 25°C (with molar extinction coefficients of H2O2solutions in the UV) Anal Biochem. 1972;49:474–478. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(72)90451-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ng W V, Kennedy S P, Mahairas G G, Berquist B, Pan M, Shukla H D, Lasky S R, Baliga N S, Thorsson V, Sbrogna J, Swartzell S, Weir D, Hall J, Dahl T A, Welti R, Goo Y A, Leithauser B, Keller K, Cruz R, Danson M J, Hough D W, Maddocks D G, Jablonski P E, Krebs M P, Angevine C M, Dale H, Isenbarger T A, Peck R F, Pohlschroder M, Spudich J L, Jung K-H, Alam M, Freitas T, Hou S, Daniels C J, Dennis P P, Omer A D, Ebhardt H, Lowe T M, Liang P, Riley M, Hood L, DasSarma S. Genome sequence of Halobacteriumspecies NRC-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:12176–12181. doi: 10.1073/pnas.190337797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pütter J, Becker R. Peroxidases. In: Bergmeyer H U, Bergmeyer J, Graßl M, editors. Methods of enzymatic analysis. 3rd ed. III. Weinheim, Germany: Verlag Chemie; 1983. pp. 286–293. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rocha E R, Smith C J. Biochemical and genetic analyses of a catalase from the anaerobic bacterium Bacteroides fragilis. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:3111–3119. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.11.3111-3119.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ruepp A, Graml W, Santos-Martinez M L, Koretke K K, Volker C, Mewes H W, Frishman D, Stocker S, Lupas A N, Baumeister W. The genome sequence of the thermoacidophilic scavenger Thermoplasma acidophilum. Nature. 2000;407:508–513. doi: 10.1038/35035069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning, a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shima S, Netrusov A, Sordel M, Wicke M, Hartmann G C, Thauer R K. Purification, characterization, and primary structure of a monofunctional catalase from Methanosarcina barkeri. Arch Microbiol. 1999;171:317–323. doi: 10.1007/s002030050716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shima S, Weiss D S, Thauer R K. Formylmethanofuran:tetrahydromethanopterin formyltransferase (Ftr) from the hyperthermophilic Methanopyrus kandleri: cloning, sequencing and functional expression of the ftr gene and one step purification of the enzyme overproduced in Escherichia coli. Eur J Biochem. 1995;230:906–913. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1995.tb20635.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smith D R, Doucette-Stamm L A, Deloughery C, Lee H, Dubois J, Aldredge T, Bashirzadeh R, Blakely D, Cook R, Gilbert K, Harrison D, Hoang L, Keagle P, Lumm W, Pothier B, Qiu D, Spadafora R, Vicaire R, Wang Y, Wierzbowski J, Gibson R, Jiwani N, Caruso A, Bush D, Reeve J N. Complete genome sequence of Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicumΔH: functional analysis and comparative genomics. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:7135–7155. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.22.7135-7155.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Terzenbach D P, Blaut M. Purification and characterization of a catalase from the nonsulfur phototrophic bacterium Rhodobacter sphaeroidesAth 2.4.1 and its role in the oxidative stress response. Arch Microbiol. 1998;169:503–508. doi: 10.1007/s002030050603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thauer R K. Biochemistry of methanogenesis: a tribute to Marjory Stephenson. Microbiology. 1998;144:2377–2406. doi: 10.1099/00221287-144-9-2377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.von Ossowski I, Hausner G, Loewen P C. Molecular evolutionary analysis based on the amino acid sequence of catalase. J Mol Evol. 1993;37:71–76. doi: 10.1007/BF00170464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wolfe R S. 1776–1996: Alessandro Volta's combustible air. ASM News. 1996;62:529–534. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zavitz K H, DiGate R J, Marians K J. The priB and priC replication proteins of Escherichia coli. Genes, DNA sequence, overexpression, and purification. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:13988–13995. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zehnder A J B, Wuhrmann K. Physiology of a Methanobacteriumstrain AZ. Arch Microbiol. 1977;111:199–205. doi: 10.1007/BF00427839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zeikus J G, Henning D L. Methanobacterium arbophilicumsp. nov. An obligate anaerobe isolated from wetwood of living trees. Antonie Leeuwenhoek. 1975;41:543–552. doi: 10.1007/BF02565096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]