Abstract

It is widely accepted that adolescents who are exposed to violence are likely to become perpetrators of dating aggression. However, it remains unclear whether the effects of exposure to violence on later perpetration of dating aggression vary based on how adolescents are exposed to violence and the contexts where adolescents are exposed to violence. Thus, the relationships between two types of exposure to violence (witnessing and victimization) in early adolescence and perpetrating dating aggression in late adolescence were compared within and across three social contexts: the home, the community, and the school. Participants included 484 youth (51% females; 81% African-Americans, 18% European-Americans, 1% Hispanic or Other). Information on exposure to violence were collected at Waves 1 and 2 during early adolescence (Wave 1: M = 11.8 years old; Wave 2: M = 13.2 years old) and dating aggression data were collected during late adolescence (Wave 3: M = 18.0 years old). The results showed that across all contexts witnessing violence was a more consistent predictor of later dating aggression relative to victimization. Being exposed to violence in the home either via observation or victimization was a stronger predictor of physical dating aggression and threatening behaviors compared to being exposed to violence in the school. These findings provide a deeper understanding of the roles of various forms of exposure to violence during early adolescence in perpetrating dating aggression later in the life course.

Keywords: adolescence, dating aggression, exposure to violence, witnessing, victimization

Introduction

Although often challenged, the notion that many perpetrators of violence were exposed to violence as youth is well accepted in the literature (Gomez, 2011; Widom, 1989). This explanation has also been used to examine the phenomenon of dating aggression (i.e., aggressive behaviors expressed within the context of romantic relationships) among adolescents and young adults (see Haselschwerdt, Savasuk-Luxton, & Hlavaty, 2017 for a review of the literature). Adolescents can be exposed to violence in various contexts, most notably in the home, the community, and the school. Studies have shown that being exposed to violence within these social contexts can contribute to the perpetration of dating aggression among adolescents and young adults (Foshee et al., 2011; Fritz, Slep, & O’Leary, 2012). However, an understanding of which of these contexts are most strongly related to later perpetration of dating aggression remains unclear. Therefore, one purpose of the present study was to compare the associations between exposure to violence in each of these three contexts and later dating aggression among adolescents transitioning to young adulthood.

Furthermore, how adolescents were exposed to violence may be just as critical to later perpetration of dating aggression as the contexts in which they were exposed to violence. Specifically, adolescents may be exposed to violence by witnessing aggressive acts or by being directly victimized. However, particularly within the contexts of the community and the school, past studies have failed to distinguish between these types of exposure to violence when examining the associations between exposure to violence and dating aggression. Within the context of the home, findings have been inconsistent when both forms of exposure to violence were disentangled. For instance, some studies have shown both forms of exposure to violence to be related to dating aggression (Jouriles, Mueller, Rosenfield, McDonald, & Dodson, 2012; Morris, Mrug, & Windle, 2015); others have shown that only victimization was related to dating aggression (Brendgen, Vitaro, Tremblay, & Wanner, 2002; Simons, Lin, & Gordon, 1998) and yet others showed that witnessing interparental aggression (i.e., exposure to domestic violence in the home) had a stronger effect on perpetrating later relationship violence when controlling for experiencing parental aggression (Ehrensaft et al., 2003). Additionally, meta-analyses revealed that although both forms of exposure to violence were related to the engagement in later relationship violence, the strength between these two relationships did not significantly differ from each other (Smith-Marek et al., 2015; Stith et al., 2000). Thus, more research is needed to understand the nature of the relationship between both forms of exposure to violence and later dating aggression perpetration. This study, then, distinguishes between both forms of exposure to violence and later perpetration of dating aggression within and across the following three contexts: (a) the home, (b) the community, and (c) the school.

Social-Learning Theory

The relationship between early exposure to violence and later dating aggression can be explained through the lens of social-learning theory. According to social-learning theory, the modeling of aggression expressed by significant agents of social influence (e.g., parents, peers, community, and media) may lead to future enactments of aggression (Bandura, 1978, 2001; Elliot & Menard, 1996). Notwithstanding that the modeling of aggression during adolescence can be learned in the home, the community, or the school, social-learning theory has been most commonly used to explain the relationship between exposure to violence in the home and dating aggression.

Exposure to Home Violence

Witnessing aggression in the home during childhood and adolescence may serve as a teachable tool for the learning of ineffective conflict resolution strategies. Through the lens of social-learning theory, exposure to interpersonal violence in the home during adolescence may serve as a model for acceptable behaviors within romantic relationships (Litcher & McCloskey, 2004). Additionally, social-learning theory argues that observed behaviors are only replicated if positive outcomes after their enactment are also witnessed (Bandura, 1978, 2001). Therefore, adolescents who witnessed their parents behaving aggressively towards one another may be more likely to enact similar behaviors in their own romantic relationships should they have also observed beneficial outcomes for the perpetrator (e.g., the ending of an argument, the perpetrator getting his/her way in the relationship). This notion is supported by many studies that have shown a relationship between witnessing interparental aggression during childhood or adolescence and relationship violence in adolescence and beyond (Author Citation, 2018; Reyes et al., 2015).

However, the modeling of aggression may not only be learned by simply watching parental aggression, but also after having experienced violence from one’s parents (O’Leary, 1988; Straus, Gelles, & Steinmetz, 1980). The relationship between having experienced parental violence as a youth and later perpetration of dating aggression is supported by recent studies (e.g., Jouriles et al., 2012; Morris et al., 2015). Within the framework of social-learning theory, it may be argued that experiencing violence from the hands of one’s parents as a youth teaches one that it is acceptable to use aggression during conflicts towards someone you love or are closely attached to in the hopes of getting one’s way in the relationship. This study seeks to build on this notion by examining whether both types of exposure to violence contribute similarly to the learning of dating aggression when it occurs within the contexts of the home, the community, and the school.

Furthermore, it may be argued that adolescents’ primary exposure to romantic interactions occurs in the home and thus would have the strongest influence on later reports of perpetrating dating aggression compared to exposure to violence in other contexts. Counter to this argument would be that the relationship between exposure to violence in the home (regardless of type of exposure) and later relationship violence has generally been shown to be small (Smith et al., 2015; Stith et al., 2000). Nevertheless, the relationship between exposure to violence in the home and dating aggression must be compared to the relationship between exposure to violence in other contexts and dating aggression to make this conclusion. Thus, the relationships between both forms of exposure to violence and dating aggression were compared across the contexts of the home, the community, and the school to address this research question.

Exposure to Community Violence

Having been exposed to community violence either through witnessing or victimization from such violence has been shown to contribute to the perpetration of dating aggression among adolescents (Black et al., 2015; Malik et al., 1997). One potential explanation for the linkage between community violence and dating aggression is due to the negative characteristics that encompass these communities. Communities where violence is prevalent are likely to suffer from negative structural characteristics (e.g., poverty, high rates of unemployment, lack of home ownership, and low educational attainment), neighborhood disorder (e.g., high rates of violent crimes and other illegal activities), and social disorganization (e.g., lack of unity within one’s neighborhood) (Johnson, Parker, Rinehart, Nail, & Rothman, 2015). Past studies have shown that these factors are related to adolescent and young adult reports of perpetrating aggression towards one’s romantic partner (see Johnson et al., 2015 for a review of the literature). Just as exposure to violence in the home, it may be that being exposed to violence within one’s community serves as a model for the enactment of aggressive behaviors among adolescents. In turn, such adolescents may turn to such behaviors when involved in a conflict with their romantic partner.

Another possible explanation for the relationship between exposure to community violence and dating aggression is that the linkage between these variables may occur through the process of desensitization (i.e., a decrease in the emotional effects of violence after constant exposure to such acts). According to Ng-Mak, Salzinger, Feldman, and Stueve (2002), constant exposure to violence can lead to a normalization of violence among youth. In other words, such youth, may eventually “adapt” to violence and accept aggressive acts as normal aspects of life. Cross-sectional and longitudinal studies have found that high levels of exposure to violence within the community were related to lower levels of psychological distress and internalizing behaviors (Kennedy & Caballo, 2016; Mrug, Madan, & Windle, 2016). Mrug and Windle (2010) indicated that the effects of exposure to violence in the home on later reports of anxiety, delinquency, and aggression were stronger for adolescents who reported little or no exposure to community violence. Furthermore, Guerra, Huessman, and Spindler (2003) found that older children (4th-6th graders) who were exposed to community violence were more likely to develop normative beliefs about aggressive behaviors and were also more likely to develop aggressive fantasies over time. These findings support the notion that exposure to community violence may lead to a desensitization of violence among youth. Within a social-learning framework, it may be argued that adolescents who become desensitized to violence after constant exposure to community violence may view aggressive behaviors as normative conflict strategies and thus may carry this perspective into their romantic relationships. Therefore, this study attempts to move this literature forward by distinguishing between two types of exposure to violence within the community (witnessing and victimization) and examining their associations with later reports of perpetrating dating aggression.

Exposure to School Violence

In comparison to exposure to other forms of violence, the relationship between school violence and dating aggression remains understudied. However, Schnurr and Lohman (2008) indicated that the perception of a lack of safety in the school combined with high reports of interparental aggression predicted later forms of dating aggression among African American males. Also, Foshee et al. (2011) found that being exposed to deviant behaviors within school grounds increased the likelihood of adolescents perpetrating violence towards their peers and dating partners. Research also hints at the possible linkage between exposure to school violence and dating aggression through the influence of bullying (i.e., repetitive aggressive behaviors perpetrated with the intention to cause psychological and/or physical harm towards someone of lower social status) (Fredland, 2008) and affiliation with deviant peers.

Given the commonality of bullying in the school environment (Seals & Young, 2003), it is likely that many adolescents have been exposed to school violence through this form of aggression. Adolescents who are victimized by bullying are also likely to experience and/or express dating aggression towards their romantic partner. For instance, among a sample of predominately middle adolescents (M = 14.50 years old), Espelage and Holt (2007) found that 4.4% of their sample (n = 30) were grouped in a cluster described as “bully-victims.” Such adolescents indicated high scores for bullying in addition to high scores for having been victimized by bullying, peer sexual harassment, and psychological and physical forms of dating aggression. Also, Miller et al. (2013) indicated that 12.2% of their sample (N = 795 early adolescents) reported having perpetrated and having experienced bullying, peer sexual harassment, and psychological and physical dating aggression. These findings suggest that exposure to school violence via forms of bullying can potentially contribute to later forms of dating aggression.

From a social-learning perspective, peer groups can serve as an important mechanism for the endorsement of aggressive behaviors (Elliot & Menard, 1996). Connolly and Goldberg (1999) argued that peers can serve as a model for acceptable and/or appropriate behaviors within the context of romantic relationships. Specifically, having friends who behave aggressively towards their dating partners may lead to the perception that the use of such behaviors is justifiable in the attempt to resolve conflicts in romantic relationships (see Vézina & Hebert, 2007 for a review of this literature). Consistent with this notion, the relationship between affiliation with deviant peers and dating aggression perpetration and victimization during adolescence is well documented (e.g., Morris et al., 2015; Schnurr & Lohman, 2013). Given that many peer relationships develop within the school setting, it is possible that many adolescents may have witnessed violence on school grounds due to their affiliation with deviant peers. Thus, it was critical for the present study to expand on this literature by disentangling both forms of exposure to school violence (witnessing and victimization) and comparing their associations to later dating aggression perpetration. This study also compares these associations to the relationships between both forms of exposure to violence within the home and the community and later reports of perpetrating dating aggression.

Sex Differences

Previous studies indicated sex differences in the relationship between exposure to violence in the home and later reports of perpetrating dating aggression. For instance, Wolf and Foshee (2003) found that witnessing interparental aggression was related to perpetrating dating aggression for females only, whereas experiencing parental violence was related to perpetrating dating aggression for males. In contrast, Smith-Marek et al. (2015) indicated that being victimized by violence in the home was a stronger predictor of adult relationship violence for females relative to males. Moreover, Kinsfogel and Grych (2004) found that the relationship between witnessing interparental aggression and perpetrating dating aggression was significant only for males. This study seeks to build on this literature by examining sex differences in the relationship between both types of exposure to violence (witnessing and victimization) across various contexts (the home, the community, and the school) and later perpetration of dating aggression.

Sex along with ethnicity and socioeconomic status were also examined as covariates due to their known relationships to reports of perpetrating dating aggression. This was critical given that the prevalence rates of relationship violence are similar and at times higher for females relative to males (see Archer, 2000 for a meta-analysis review; see Straus, 2009 for a literature review). Additionally, rates of dating aggression are generally higher among ethnic minorities than whites (Caetano, Field, Ramisetty-Mikler, & McGrath, 2005) and among adolescents from lower vs. higher socioeconomic backgrounds (Author Citation, 2018; O’Keefe, 1998).

Psychological vs. Physical Aggression

Additionally, the relationships noted above were examined for the perpetration of both psychological (i.e., threatening behaviors and emotional abuse) and physical forms of dating aggression. Many adolescents and young adult women survivors of physical abuse reported that the effects of psychological aggression were even more detrimental than those of physical aggression (Follingstad, Rutledge, Berg, Hause, & Polek, 1990; Jouriles, Garrido, Rosenfield, & McDonald, 2009). Adolescent and young adult reports of experiencing and/or perpetrating psychological aggression are generally higher than reports of engaging and/or being victimized by physical aggression (Author Citation, 2019; Jouriles et al., 2009). Victims of psychological aggression are also likely to experience a range of negative physical and mental health outcomes (Taft et al., 2006). Therefore, it is essential to understand the roles of exposure to violence in the perpetration of both forms of dating aggression.

The Current Study

The primary aim of this study was to examine and compare the effects of two types of exposure to violence (witnessing and victimization) within and across the following three contexts: the home, the community, and the school. First, it was examined whether exposure to violence either through witnessing or victimization across the contexts of the home, the community, and the school predicts later reports of dating aggression (Research Question 1). Consistent with the literature, it was hypothesized that both forms of exposure to violence for each context would predict later engagement of dating aggression (Hypothesis 1). Next, it was examined whether the effects of both forms of exposure to violence on later perpetration of dating aggression vary within contexts (Research Question 2). Due to the lack of distinction between exposure to violence via witnessing or victimization in previous studies, and inconsistencies across other studies when comparing the effects of both forms of exposure to violence within the home on later perpetration of relationship violence, no hypotheses were made for this research question. Lastly, it was examined whether the effects of exposure to violence on later perpetration of dating aggression vary across contexts (Research Question 3). Because adolescents’ primary exposure to romantic interactions is generally in the home, it was expected that the effects of both forms of exposure to violence in the home on later dating aggression perpetration would be stronger than the effects of being exposed to violence in other contexts on later engagement in dating aggression (Hypothesis 2). No hypotheses were made regarding whether these relationships will differ across sexes and between psychological and physical dating aggression.

Method

Participants and Procedure

Participants were part of the Birmingham Youth Violence Study (BYVS), a longitudinal study of youth violence in Birmingham, Alabama. Using a two-stage probability sampling procedure, 17 public schools within the metropolitan area were randomly selected to obtain a representative sample. Next, all students from 5th grade classrooms in these schools were invited to participate in the study, yielding a sample of 704 adolescents who completed Wave 1 (42% recruitment rate) (Morris et al., 2015; Mrug & Windle, 2010).

Data were collected at three time points between the years of 2003–2012 (Wave 1: N = 704, M = 11.8 years old, SD = .76; Wave 2: N = 603, M = 13.2 years old, SD = .91; Wave 3: N = 502, M = 18.0 years old, SD = .83). The present study only includes 484 youth who participated in Wave 3 and provided data on dating aggression. Youth who were included (vs. excluded) were more likely to be African American (χ2 (1) = 15.42, p < .001) and female (χ2 (1) = 10.11, p < .01).

Participants in the analytic sample included 51% females; 81% were African Americans, 18% European Americans, and 1% Hispanic or Other. At Wave 1, the median household income for the analytic sample ranged from $25,001 - $30,000. Approximately 29% of the analytic sample’s primary caregivers had some college education but no college degree, and 43% of participants’ primary caregivers were married.

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. Adolescent assent or consent and parental consent (when youth were below age 18) were provided at each time point. Adolescents were informed that their participation was voluntary and that they were able to stop the interview at any time and skip any questions that they did not wish to answer. Trained interviewers administered the interviews in private spaces using Computer-Assisted Personal Interviews. Sensitive questions were completed privately by participants through the Audio-Computer Assisted-Self-Interview (ACASI). Financial compensation was provided to participants for their time ($20 at Waves 1 and 2 and $50 at Wave 3).

Measures

Exposure to Violence.

Both forms of exposure to violence (witnessing and victimization) were assessed at Waves 1 and 2 using the Birmingham Youth Violence Exposure measure (Mrug et al., 2008). Separate scores were created for witnessing violence and for being victimized by violence in each context (the school, the community, and the home). Each score was made up of three items. Specifically, for witnessing, participants were asked whether within the past 12 months they witnessed 1) a threat of physical violence, 2) actual physical violence, and 3) a threat or actual violence involving a weapon. For victimization, participants were asked whether within the past 12 months they were victims of 1) a threat of physical violence, 2) actual physical violence, and 3) a threat or actual violence involving a weapon. Endorsement of any witnessing or victimization item was followed by three contextual probes, asking whether the exposure occurred in the home, school, or neighborhood. Responses to all questions were dichotomous (0 = No, 1 = Yes). The witnessing and victimization scores for each context were created by summing the three dichotomous contextual items across the two waves. Thus, each score per context could potentially range from 0–6 with higher scores reflecting more exposure to violence. Across waves, for each context, the correlations between the items that made up the scores for witnessing and for victimization ranged from small to moderate. Specifically, for witnessing violence, inter-item correlations ranged between .11 to .49 and for victimization they ranged from .10 to .48.

Dating Aggression.

Data on perpetrating dating aggression were collected at Wave 3 using the Conflict in Adolescent Dating Relationship Inventory (CADRI; Wolfe et al., 2001). Participants reported on 18 items assessing whether they engaged in various forms of dating aggression within the past 12 months. Factor analyses conducted for the analytic sample revealed that the CADRI items loaded across three separate factors. Therefore, the following three latent factors were created: physical aggression (four items; e.g., “I threw something at him/her”), threatening behaviors (four items; e.g., “I threatened to hurt him/her”), and emotional abuse (10 items; e.g., “I did something to make him/her jealous”). These factors are consistent with the findings of Wolfe et al. (2001) in the development of this measure. All items used a dichotomous response scale (0 = No, 1 = Yes) and were summed to form the subscales. Internal consistency for each subscale was high. Specifically, Cronbach alphas were .85 for physical aggression, .77 for threatening behaviors, and .82 for emotional abuse.

Demographic covariates.

Demographic covariates included sex, ethnicity, and SES. Sex and ethnicity were dichotomized (Sex: 0 = Male, 1 = Female; Ethnicity: 0 = European American, 1 = African American or other minority). The SES score was calculated by taking the average of standardized scores (z-scores) for parental education and household income from Wave 1. Higher scores indicated higher SES.

Plan of Analysis

Preliminary analyses were conducted in SPSS Version 23 (IBM Corp.) to examine differences across sex and ethnicity in the subscales for exposure to violence and dating aggression. The summed values for perpetrating physical dating aggression, threatening behaviors, emotional abuse, and for exposure to violence either through witnessing or victimization for each context (school, community, and home) were compared across sexes via a series of t-tests.

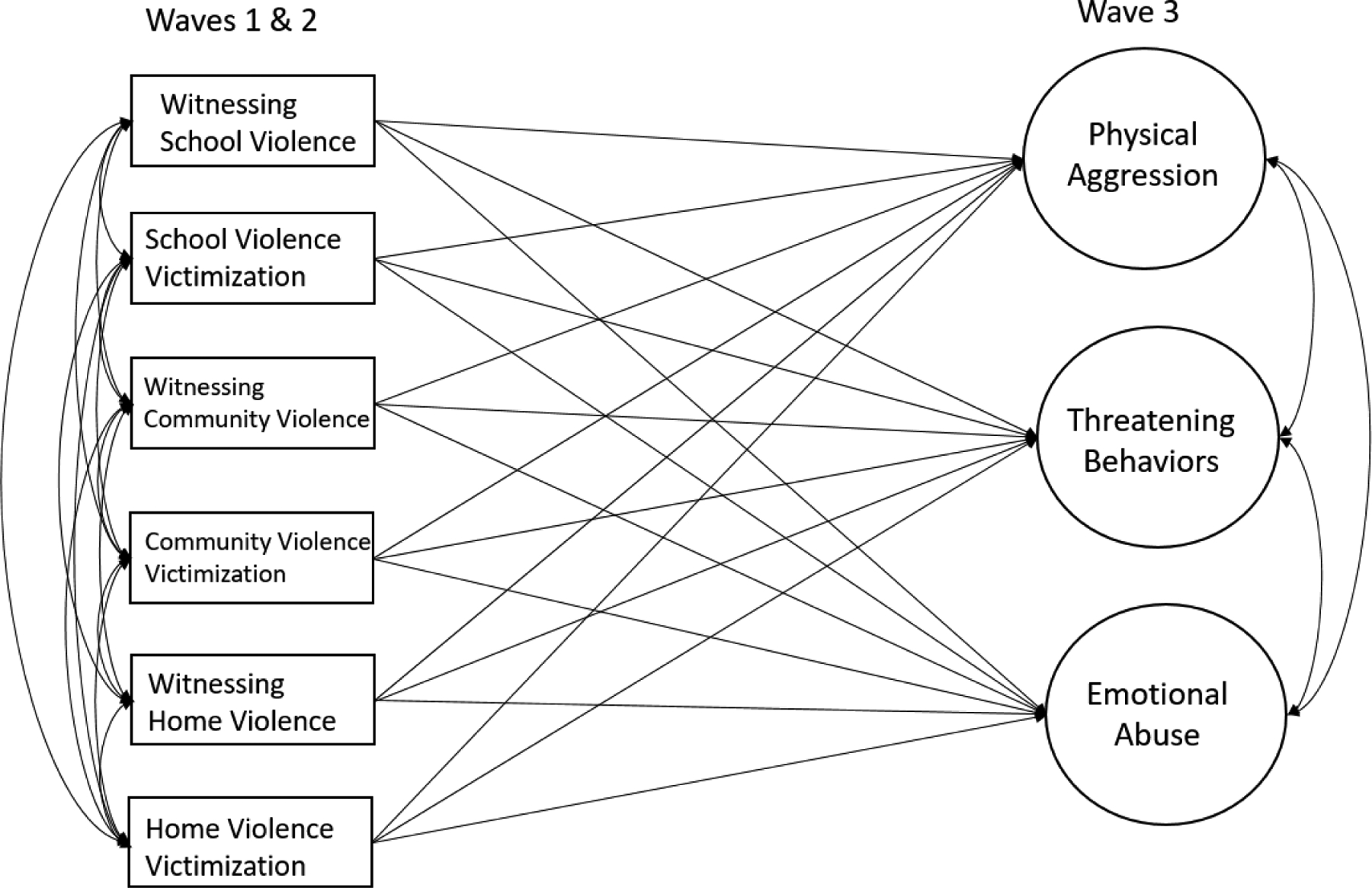

All main analyses for the current study were conducted in MPLUS Version 7 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2012). A latent factor was created for each type of dating aggression (physical aggression, threatening behaviors, and emotional abuse). Each latent factor was indicated by the items representative of each type of dating aggression. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted to examine whether the latent variables adequately fit the data. Structural equation modeling (SEM) was used to examine the research questions. In a single model, the three outcome variables (dating aggression latent factors) were predicted by all six exposure to violence variables and the demographics (sex, ethnicity, and SES) (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Hypothesized SEM model of exposure to violence across contexts predicting dating aggression. Analyses controlled for sex, ethnicity, and SES (N = 484).

As common in any longitudinal study, not all participants provided data at all three waves. Therefore, Full Information Maximum Likelihood (FIML) was used to account for missing data to include all participants who provided data for at least one wave in the analyses. For the CFA and SEM analyses, model fit was examined by the chi-square statistic (χ2), the comparative fit index (CFI), the Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and the standardized root mean square error residual (SRMR). A non-significant χ2, a CFI and/or TLI between .90 and 1.00 (Bentler & Bonnett, 1980), an RMSEA of .10 or lower (Harlow, 2014), and a SRMR of .10 or lower (Kline, 2016) were used as criteria for indicators of good model fit.

To examine whether the effects of exposure to violence either via witnessing or experiencing violence on later forms of perpetrating dating aggression varied within and across contexts (i.e., Research Questions 2 & 3), these pathways were compared by conducting a series of delta chi-square tests (Δχ2). Only paired pathways that were significant for each outcome were compared. Pathways that were compared were constrained to equality and were then compared to the model where they were free to differ. Pathways were determined as different if the change in the overall χ2 for the constrained model compared to the unconstrained model surpassed the critical value for one degree of freedom (χ2 (1) = 3.84, p < .05).

Multigroup analyses were conducted to examine whether the associations between exposure to violence and dating aggression varied across youths’ sex. Pathways from the SEM model were tested across both dichotomous groups while controlling for all demographic variables except for the one being used as a grouping factor (i.e., sex). The effects of SES and ethnicity on each latent factor were set to equality across the two groups. Due to the number of tests conducted, a p-value of .01 was used as the criterion for significance. All pathways were constrained to equality one at a time across groups (e.g., males vs. females), and this model was compared to the unconstrained model in which all the paths were free to be different across groups. Should change in the overall chi-square for the constrained model relative to the unconstrained model exceed the critical value for one degree of freedom (χ2 (1) = 6.64, p < .01), the pathway would be deemed as different across groups.

Results

Table 1 presents the means and standard deviations for all variables, as well as their intercorrelations. Approximately 24% of adolescents indicated that they perpetrated at least one type of physical dating aggression, 24% reported that they threatened their romantic partner, and 86% reported perpetrating at least one form of emotional abuse. Furthermore, between 14%−85% of adolescents were exposed to some type of violence. Specifically, 85% of adolescents witnessed and 35% of adolescents were victimized by school violence, 45% of adolescents witnessed and 14% of adolescents were victimized by violence within their community, and 15% of the sample witnessed whereas 15% of adolescents were victimized by violence in their home.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics and correlations between exposure to violence variables within and across contexts, perpetration of various forms of dating aggression, and control variables

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Witness school | - | |||||||||||

| 2. Victim school | .41*** | - | ||||||||||

| 3. Witness community | .23*** | .21*** | - | |||||||||

| 4. Victim community | .15** | .29*** | .48*** | - | ||||||||

| 5. Witness home | .16** | .23*** | .17*** | .20*** | - | |||||||

| 6. Victim home | .13** | .29*** | .12* | .17*** | .51*** | - | ||||||

| 7. Physical Aggression | .16** | −.04 | .15** | .04 | .20*** | .15** | - | |||||

| 8. Threatening Behaviors | .18*** | .02 | .13** | .04 | .25*** | .16** | .73*** | - | ||||

| 9. Emotional Abuse | .23*** | .01 | .08 | .00 | .15** | .07 | .50*** | .54* | - | |||

| 10. Female | −.01 | −.14** | −.15** | −.17*** | .07 | −.00 | .29*** | .23*** | .24*** | - | ||

| 11. Ethnic minority | .23*** | .01 | .23*** | .07 | .08 | .02 | .20*** | .16*** | .12** | .04 | - | |

| 12. SES | −.11* | −.01 | −.25*** | −.06 | −.02 | .02 | −.18*** | −.13** | −.05 | −.10* | −.34*** | - |

| M | 2.49 | .67 | 1.05 | .24 | .26 | .24 | .54 | .47 | 3.90 | .52 | .82 | −.00 |

| SD | 1.37 | 1.03 | 1.42 | .64 | .68 | .62 | 1.13 | .99 | 2.84 | .86 |

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001; N=484.

Results of t-tests comparing the two sexes revealed that females reported greater use of all three types of dating aggression (Physical aggression: t (481) = −6.65, p < .001; Threatening behaviors: t (481) = −5.28, p < .001; Emotional abuse: t (481) = −5.43, p < .001). Males reported higher levels of victimization by violence in the school (t (441) = 2.98, p < .01) and the community (t (441) = 3.65, p < .001) and reported higher levels of witnessing violence in the community (t (440) =3.20, p < .01). Additionally, participants who represented a minority ethnic background (African American or other minority background) perpetrated more physical aggression (t (481) = −4.36, p < .001), threatening behaviors (t (481) = −3.61, p < .001), and emotional abuse (t (481) = −2.66, p < .01). African Americans and other minority groups also reported higher levels of witnessing school violence (t (440) = −5.06, p < .001) and community violence (t (440) = −4.84, p < .001).

Lastly, results from CFA analyses showed that all indicators for each type of dating aggression loaded on their respective factors and that the model was an excellent fit to the data (χ2(132) = 283.51, p < .001; CFI = .95; TLI = .94; RMSEA = .05, 90% Confidence Interval (CI) = [0.04, 0.06]; SRMR = .04). Moreover, all three latent variables were highly correlated with one another and most of the items loaded strongly onto their latent variables.

Exposures to Violence Predicting Dating Aggression

The SEM model in which all six exposure to violence variables were included as predictors of each type of dating aggression was an excellent fit to the data (see Table 2). Results showed that witnessing violence in the school significantly predicted the perpetration of physical aggression, threatening behaviors, and emotional abuse. Witnessing violence in the home also significantly predicted the perpetration of all three types of dating aggression. Witnessing violence in the community only predicted the perpetration of physical aggression. Surprisingly, being victimized by violence in the school predicted lower use of physical aggression. Lastly, being victimized by violence in the home significantly predicted the use of physical aggression. On an important note, having witnessed violence across contexts more consistently predicted all three types of dating aggression than victimization. All six exposure to violence variables accounted for 11% of the variance in physical aggression, 11% of the variance in threatening behaviors, and 10% of the variance in emotional abuse. With the inclusion of demographic variables, 22%, 20%, and 16% of the variance were explained for physical aggression, threatening behaviors, and emotional abuse, respectively.

Table 2.

Standardized and unstandardized parameter estimates, R-squares, and fit statistics for contexts of exposure to violence predicting the perpetration of various forms of dating aggression.

| Physical Aggression | Threatening Behaviors | Emotional Abuse | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | (SE) | β | B | (SE) | β | B | (SE) | β | |

| Witness School | .03 | (.01) | .14** | .03 | (.01) | .14* | .06 | (.01) | .25*** |

| Victim School | −.04 | (.02) | −.14** | −.02 | (.02) | −.09 | −.03 | (.02) | −.10 |

| Witness Community | .03 | (.01) | .15** | .02 | (.01) | .08 | .02 | (.01) | .07 |

| Victim Community | −.00 | (.02) | −.00 | −.01 | (.02) | −.01 | −.02 | (.03) | −.03 |

| Witness Home | .05 | (.02) | .11* | .08 | (.02) | .20*** | .06 | (.03) | .12* |

| Victim Home | .05 | (.03) | .11* | .02 | (.03) | .05 | −.00 | (.03) | −.00 |

| Female | .17 | (.03) | .29*** | .15 | (.03) | .27*** | .17 | (.03) | .25*** |

| Ethnic minority | .06 | (.04) | .08 | .07 | (.04) | .09 | .05 | (.05) | .06 |

| SES | −.03 | (.02) | −.09 | −.02 | (.02) | −.07 | .01 | (.02) | .03 |

| R-Square | |||||||||

| Dating Violence | .22 | .20 | .16 | ||||||

| Fit Statistics | |||||||||

| Chi-Square | 494.88*** | ||||||||

| DF | 267 | ||||||||

| CFI | .93 | ||||||||

| TLI | .92 | ||||||||

| RMSEA | .04 | ||||||||

| SRMR | .04 | ||||||||

N=484

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001

Comparisons within Contexts

Comparisons within contexts of exposure to violence were conducted only for paired pathways that were significant for each outcome. Therefore, the following two pathways were compared: a) witnessing and being victimized by violence in the school predicting physical aggression, and b) witnessing and being victimized by violence in the home predicting physical aggression. Results from Δχ2 tests revealed that the positive path coefficient between witnessing violence in the school and physical aggression differed from the negative path coefficient between being victimized by violence in the school and physical aggression. A statistically significant difference between the pathways from witnessing and being victimized by violence in the home predicting physical dating aggression was not found (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Differences in pathways within contexts between types of exposure to violence (witnessing vs. victimization) predicting various forms of dating aggression.

| Physical Aggression | Threatening Behaviors | Emotional Abuse | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | (S.E) | β | B | (S.E) | β | B | (S.E) | β | |

| Witness School | .03 | (.01) | .14 ** | .03 | (.01) | .14* | .06 | (.01) | .25*** |

| Victim School | −.04 | (.02) | −.14** | −.02 | (.02) | −.09 | −.03 | (.02) | −.10 |

| Witness Community | .03 | (.01) | .15** | .02 | (.01) | .08 | .02 | (.01) | .07 |

| Victim Community | −.00 | (.02) | −.00 | −.01 | (.02) | −.01 | −.02 | (.03) | −.03 |

| Witness Home | .05 | (.02) | .11* | .08 | (.02) | .20*** | .06 | (.03) | .12* |

| Victim Home | .05 | (.03) | .11* | .02 | (.03) | .05 | −.00 | (.03) | −.00 |

| Female | .17 | (.03) | .29*** | .15 | (.03) | .27*** | .17 | (.03) | .25*** |

| Ethnic minority | .06 | (.04) | .08 | .07 | (.04) | .09 | .05 | (.05) | .06 |

| SES | −.03 | (.02) | −.09 | −.02 | (.02) | −.07 | .01 | (.02) | .03 |

| R-Square | |||||||||

| Dating Violence | .22 | .20 | .16 | ||||||

| Fit Statistics | |||||||||

| Chi-Square | 494.88*** | ||||||||

| DF | 267 | ||||||||

| CFI | .93 | ||||||||

| TLI | .92 | ||||||||

| RMSEA | .04 | ||||||||

| SRMR | .04 | ||||||||

N=484

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001

Significant differences are in bold font.

Comparisons across Contexts

Similar to when making comparisons within contexts, only paired pathways that were significant across contexts were compared. Four pairs of pathways were compared when predicting physical aggression: a) witnessing violence in the school compared to witnessing violence in the community, b) witnessing violence in the school compared to witnessing violence in the home, c) witnessing violence in the community compared to witnessing violence in the home, and d) being victimized by violence in the school compared to being victimized by violence in the home. Only one of these comparisons showed a statistically significant difference (see Table 4). Specifically, victimization by violence in the home positively predicted physical aggression, whereas victimization from violence in the school negatively predicted physical aggression.

Table 4.

Differences in pathways across contexts between types of exposure to violence predicting various forms of dating aggression.

| Physical Aggression | Threatening Behaviors | Emotional Abuse | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | (S.E) | β | B | (S.E) | β | B | (S.E) | β | |

| Witness School | .03 | (.01) | .14** | .03 | (.01) | .14 * | .06 | (.01) | .25*** |

| Victim School | -.04 | (.02) | -.14 ** | −.02 | (.02) | −.09 | −.03 | (.02) | −.10 |

| Witness Community | .03 | (.01) | .15** | .02 | (.01) | .08 | .02 | (.01) | .07 |

| Victim Community | −.00 | (.02) | −.00 | −.01 | (.02) | −.01 | −.02 | (.03) | −.03 |

| Witness Home | .05 | (.02) | .11* | .08 | (.02) | .20 *** | .06 | (.03) | .12* |

| Victim Home | .05 | (.03) | .11 * | .02 | (.03) | .05 | −.00 | (.03) | −.00 |

| Female | .17 | (.03) | .29*** | .15 | (.03) | .27*** | .17 | (.03) | .25*** |

| Ethnic minority | .06 | (.04) | .08 | .07 | (.04) | .09 | .05 | (.05) | .06 |

| SES | −.03 | (.02) | −.09 | −.02 | (.02) | −.07 | .01 | (.02) | .03 |

| R-Square | |||||||||

| Dating Violence | .22 | .20 | .16 | ||||||

| Fit Statistics | |||||||||

| Chi-Square | 494.88 | ||||||||

| DF | 267 | ||||||||

| CFI | .93 | ||||||||

| TLI | .92 | ||||||||

| RMSEA | .04 | ||||||||

| SRMR | .04 | ||||||||

N = 484

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001

Significant differences are in bold font.

The paired pathways of witnessing violence in the school compared to witnessing violence in the home was the only comparison made for the prediction of threatening behaviors. Results showed that these pathways differed from each other, with witnessing violence in the home more strongly predicting threatening behaviors compared to witnessing violence in the school (see Table 4). Pathways from witnessing violence in the school and witnessing violence in the home were also compared for the prediction of emotional abuse; however, a statistically significant difference between these pathways was not shown.

Sex Differences

All pathways were compared across sexes via multigroup tests to examine whether the pathways in the model differed between these two groups. A total of 18 comparisons (six predictors by three outcomes) were conducted. Only one test revealed a significant difference across sexes. Specifically, being victimized by violence in the school negatively predicted threatening behaviors for females (B = −.09, p < .01; β = −.27, p < .01) but was not a significant predictor of this outcome for males (B = .01, p = .27; β = .10, p = .27). Thus, these findings suggest that the model for this study generally held across sexes, though it appears that being victimized by violence in school may only be protective against using threatening behaviors in dating relationships for females.

Discussion

Previous studies suggest that early exposure to violence can contribute to later perpetration of dating aggression among youth (see Haselschwerdt et al., 2017 for a review of the literature). However, it is unknown whether the effects of exposure to violence on later reports of perpetrating dating aggression vary based on whether adolescents witnessed or were victims of violence and the social context in which adolescents were exposed to violence. Therefore, this study compared the effects of witnessing versus being victimized by violence on later perpetration of dating aggression within and across three contexts of the home, the community, and the school. Overall, findings revealed few differences in the relationship between both forms of exposure to violence (witnessing and victimization) within and across contexts. However, across contexts, witnessing violence was a more consistent predictor of later dating aggression perpetration. Moreover, being exposed to violence in the home, whether through witnessing or victimization, more strongly/consistently predicted later reports of dating aggression. These findings were shown for all three types of dating aggression (i.e., physical aggression, threatening behaviors, and emotional abuse).

When comparing the effects of witnessing and victimization within each context, only one significant difference emerged for the school setting. Unexpectedly, being victimized by school violence was negatively related to perpetrating later physical dating aggression, whereas as expected, witnessing school violence was positively related to perpetrating later physical dating aggression. The negative association between school victimization and later physical dating aggression appears to be a suppressor effect, given that zero-order correlations indicated no relationship between these two variables (see Table 1). Thus, school victimization was only related to later physical dating aggression when controlling for witnessing school violence and other forms of exposure to violence. Another interpretation may be that this relationship applies to adolescents who do not engage in any type of aggressive or delinquent behaviors. It is well documented that adolescents who engage in any or multiple kinds of deviant behaviors are also likely to engage in dating aggression (Chiodo et al., 2012; Williams et al., 2008). Thus, in this study, it may be that adolescents who were victimized by peers at school but were not involved in any other type of violence were less likely to be involved in dating aggression in the future. Future studies will need to examine whether this finding can be replicated among youth with no history of aggression or deviant behaviors to confirm this claim.

The few differences shown when comparing the relationships between both forms of exposure to violence and perpetrating later dating aggression within contexts are consistent with past findings. For instance, meta-analyses by Smith-Marek et al. (2015) and Stith et al. (2000) revealed no differences in the strengths of the relationship between witnessing violence and later relationship violence compared to victimization and later relationship violence. These results move beyond past findings by making these comparisons within contexts other than the home. Collectively, these results suggest that when both types of exposure to violence are significantly related to later relationship violence (as was shown for physical dating aggression), they can equally contribute to perpetrating such behaviors later in the life course. In accordance with social-learning theory (Bandura, 1978, 2001), these findings imply that the learning of aggression via victimization is just as important as learning by witnessing violence.

Although both forms of exposure to violence may contribute to the learning of aggression among youth, certain differences between both types may arise depending on the social context. Specifically, across contexts, controlling for the effects of exposure through victimization, witnessing violence was a more consistent predictor of later dating aggression perpetration. This suggest that although both forms of exposure to violence may hold similarities, depending on the context, learning aggression through means of observation may have a more lasting effect on perpetrating dating aggression relative to being victimized by violence. Furthermore, across contexts, being exposed to violence in the home was the strongest and/or most consistent predictor of later perpetration for all three types of dating aggression. For instance, witnessing violence in the home more strongly predicted threatening behaviors relative to witnessing violence in the school. Additionally, being victimized by violence in the home not only predicted later perpetration of physical dating aggression, but this pathway was also significantly different than the pathway between being victimized by school violence and later perpetration of physical dating aggression (the latter relationship was in the negative direction). Taken together, these findings suggest that being exposed to violence in the home has a stronger or more lasting effect on later perpetration of dating aggression relative to being exposed to violence in other contexts. Overall, these findings support the present study’s hypothesis that adolescents’ general primary exposure to romantic interactions (i.e., the home) has a stronger or a more consistent influence on being involved in an aggressive dating relationship.

Given the rise and significance of romantic relationships in adolescent development (Carver, Joyner, & Udry, 2003; Collins, 2003), it is critical to understand factors that can increase the likelihood for negative romantic experiences during this developmental period. Studies have shown that adolescents who are involved in an aggressive relationship are likely to experience various health consequences such as depression, suicidal thoughts, unhealthy weight control behaviors, and substance use (Barnyard & Cross, 2008; Silverman, Raj, Mucci, & Hathaway, 2001). Therefore, it is critical to understand the development of dating aggression among adolescent populations. These findings contribute to current understanding on how various exposures to violence can bring adverse outcomes to adolescent romantic relationships. Specifically, these findings suggest that although being exposed to violence in the home may be the most critical factor to later perpetration of dating aggression during adolescence, being exposed to violence in other settings during this time period can also increase the likelihood of later aggression in romantic relationships. These findings also suggest that adolescents are vulnerable to all forms of exposure to violence (witnessing and victimization). Thus, it is critical to address various forms of exposure to violence across various contexts to prevent the development of dating aggression during adolescence.

Consistent with this point, these findings also imply that prevention and intervention programs may need to target adolescents differently based on how they were exposed to violence. Although all forms of exposure to violence are critical to later perpetration of dating aggression, it was found that being exposed to violence in the home may be the most critical to later perpetration of such behaviors. Thus, more efforts may need to be placed on adolescents who come from a violent household to diminish their current or potential use of dating aggression. Such adolescents may be more likely to hold views that endorse the usage of aggression within romantic relationships (Litcher & McCloskey, 2004), which in turn have been shown to contribute to the perpetration of dating aggression (Litcher & McCloskey, 2004; Williams et al., 2008).

Despite the important contributions of this study, certain limitations must be recognized and addressed in future research. For instance, participants who were included in the analysis sample were more likely to have been African-Americans and female. This, along with the geographic area (participants were all from the southern region of the United States), the culture, and ethnic composition of the sample (81% of the sample were African-Americans) limits the generalizability of the present findings. Thus, this study will need to be replicated among different populations, particularly at-risk populations (e.g., low SES adolescents, inner-city youth, and juvenile delinquents) to examine whether these findings can be applied across wider populations. Moreover, the uneven distribution across ethnic groups disallowed for the examination of ethnic differences across pathways. The replication of these findings among different populations, particularly within a sample of equal ethnic distribution, will allow for the investigation of ethnic similarities and differences. Understanding potential ethnic differences in the relationship between exposure to violence and later perpetration of dating aggression is critical given that minority ethnic groups are more likely to perpetrate such behaviors relative to individuals from the majority culture (Caetano et al., 2005).

The findings of this study also will need to be replicated among a larger sample size. Results from power analyses revealed that there may not be enough power in this sample for the number of analyses conducted. Thus, the probability of Type I error in our findings must be considered. However, given that this study’s research questions were exploratory, the amount of analyses conducted were necessary and can be regarded as a stepping stone for future studies when comparing the effects of different forms of exposure to violence across various contexts.

Additionally, future studies will need to examine whether the findings of this study can be replicated using a frequency scale for measuring dating aggression. The dichotomous scale used in this study does not account for the frequency of dating aggression perpetration. Future studies will also need to examine the role of poly-victimization (i.e., exposure to violence across multiple contexts) in later perpetration of dating aggression. For instance, it will be important to examine whether exposure to violence across more than one context has a stronger effect on later dating aggression perpetration relative to being exposed to violence in one context. Lastly, should exposure to violence in the home be the primary source of exposure to violence among adolescents, future studies should also investigate whether being exposed to violence in this setting increases the odds of exposure to violence in other settings (e.g., school and community) and how this in turn relate to later perpetration of dating aggression.

Conclusion

It has often been concluded in the literature that perpetrators of dating aggression were exposed to violence as youth. Nevertheless, more research is needed to understand how the relationship between exposure to violence and later perpetration of dating aggression may vary across social contexts and based on the types of exposure to violence. Therefore, comparisons of the associations between two types of exposure to violence (witnessing vs. victimization) and later reports of dating aggression perpetration were conducted within and across three social contexts: the home, the community, and the school. Although few differences were shown within and across contexts, it was found that regardless of the social context, aggression learned either via observation or victimization can contribute to later perpetration of dating aggression. However, across contexts, exposure to violence via observation was a more consistent predictor of perpetrating dating aggression. This suggests that the impact of witnessing violence depending on the social context may be more harmful relative to being victimized by violence. Furthermore, results from comparison tests revealed that being exposed to violence in the home, whether through witnessing or victimization, was a stronger or more consistent predictor of later reports of perpetrating dating aggression than violence exposure in the school or community. These findings suggest that aggressive behaviors learned in the home may have a stronger influence on later perpetration of dating aggression relative to other contexts. Thus, these findings support the notion that adolescents’ primary and most critical exposure to romantic interactions is indeed in their home.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants K01DA024700 from the National Institutes of Health to S.M. and R49-CCR418569 from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to M.W.

References

- Archer J (2000). Sex differences in aggression between heterosexual partners: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 126, 651–680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A (1978). Social learning theory of aggression. Journal of Communication, 28(3), 12–29. DOI: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.1978.tb01621.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A (2001). Social cognitive theory of mass communication. Media Psychology, 3, 265–299. DOI: 10.1207/S1532785XMEP0303_03 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barnyard VL, & Cross C (2008). Consequences of teen dating violence: Understanding intervening variables in ecological context. Violence Against Women, 14, 998–1013. DOI: 10.1177/1077801208322058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM, & Bonnett DG (1980). Significance tests and goodness of fit in the analysis of covariance structures. Psychological Bulletin, 88, 588–606. [Google Scholar]

- Black BM, Chido LM, Preble KM, Weisz AN, Yoon JS, Delaney-Black V, Kernsmith P, & Lewandowski L (2015). Violence exposure and teen dating violence among African American youth. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 30(12), 2174–2195. DOI: 10.1177/0886260514552271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brendgen M, Vitaro F, Tremblay RE, & Wanner B (2002). Parent and peer effects on delinquency-related violence and dating violence: A test of two mediational models. Social Development, 11(2), 225–244. [Google Scholar]

- Caetano R, Field CA, Ramisetty-Mikler S, McGrath C (2005). The 5-year course of intimate partner violence among white, black, and hispanic couples in United States. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 20(9), 1039–1057. DOI: 10.1177/0886260505277783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver K, Joyner K, & Udry RJ (2003). National estimates of adolescent romantic relationships. In Florsheim P (Ed.), Adolescent romantic relations and sexual behavior: Theory, research, and practical implications (pp. 23–56). Mahwah, N.J: Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Chiodo D, Crooks CV, Wolfe DA, McIsaac C, Hughes R, & Jaffe PG (2012). Longitudinal prediction and concurrent functioning of adolescent girls demonstrating various profiles of dating violence and victimization. Prevention Science (13), 350–359. DOI: 10.1007/s11121-011-0236-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choice P, Lamke LK, & Pittman JF (1995). Conflict resolution strategies and marital distress as mediating factors in the link between witnessing interparental violence and wife battering. Violence and Victims, 10(2), 107–119. DOI: 10.1891/0886-6708.10.2.107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins WA (2003). More than myth: The developmental significance of romantic relationships during adolescence. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 13(1), 1–24. DOI: 10.1111/1532-7795.1301001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Connolly J, & Goldberg A (1999). Romantic relationship in adolescence: The role of friends and peers in their emergence and development. In Furman W, Brown BB, & Feiring C (Eds.), The development of romantic relationships in adolescence (pp. 266–290). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ehrensaft M, Cohen P, Brown J, Smailes E, Chen H, & Johnson JG (2003). Intergenerational transmission of partner violence: A 20-year prospective study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 71(4), 74–753. DOI: 10.1037/0022-006X.71.4.741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliot D, & Menard S (1996). Delinquent friends and delinquent behavior: Temporal and developmental patterns. In Hawkins JD (Ed.), Delinquency and crime: Current theories (pp. 28–67). Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Espelage DL, & Holt MK (2007). Dating violence & sexual harassment across the bully-victim continuum among middle and high school students. Journal of Youth Adolescence, 36, 799–811: DOI: 10.1007/s10964-006-9109-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Follingstad DR, Rutledge LL, Berg BJ, Hause AS, & Polek DS (1990). The role of emotional abuse in physically abusive relationships. Journal of Family Violence, 5(2), 107–120. [Google Scholar]

- Foshee VA, Reyes HLM, Ennett ST, Suchindran C, Mathias JP, Karriker-Jaffe KJ, Bauman KE, & Benefield TS (2011). Risk and protective factors distinguishing profiles of adolescent peer and dating violence perpetration. Journal of Adolescent Health, 48, 344–350. DOI: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.07.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredland NM (2008). Sexual bullying: Addressing the gap between bullying and dating violence. Advances in Nursing Science, 31(2), 95–105. DOI: 10.1097/01.ANS.0000319560.76384.8a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritz PAT, Slep AMS, & O’Leary KD (2012). Couple-level analysis of the relation between family-of-origin aggression and intimate partner violence. Psychology of Violence, 2(12), 139–153. DOI: 10.1037/a0027370 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez AM (2011). Testing the cycle of violence hypothesis: Child abuse and adolescent dating violence as predictors of intimate partner violence in young adulthood. Youth & Society, 43(1), 171–192. DOI: 10.1177/0044118X09358313 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guerra NG, Huesmann R, & Spindler A (2003). Community violence exposure, social cognition, and aggression among urban elementary school children. Child Development, 74(5), 1561–1576. DOI: 10.1111/1467-8624.00623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hare AL, Miga EM, & Allen JP (2009). Intergenerational transmission of aggression in romantic relationships: The moderating role of attachment security. Journal of Family Psychology, 23, 808–818. DOI: 10.1037/a0016740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harlow LL (2014). The essence of multivariate thinking: Basic themes and methods: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Haselschwerdt ML, Savasuk-Luxton R, Hlavaty K (2017). A methodological review and critique of the “intergenerational transmission of violence” literature. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. Advance online publication. DOI: 10.1177/1524838017692385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt MK, & Espelage DL (2005). Social support as a moderator between dating violence victimization and depression/anxiety among African American and Caucasian adolescents. School Psychology Review, 34(3), 309–328. [Google Scholar]

- IBM Corp. (2015). IBM SPSS statistics for Windows, version 23.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson RM, Parker EM, Rinehart J, Nail J, & Rothman EF (2015). Neighborhood factors and dating violence among youth: A systematic review. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 49(3), 458–466. DOI: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.05.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jouriles EN, Garrido E, Rosenfield D, & McDonald R (2009). Experiences of psychological and physical aggression in adolescent romantic relationships: Links to psychological distress. Child Abuse & Neglect, 33, 451–460. DOI: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2008.11.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jouriles EN, Mueller V, Rosenfield D, McDonald R, & Dodson MC (2012). Teens’ Experiences of harsh parenting and exposure to severe intimate partner violence: Adding insult to injury in predicting teen dating violence. Psychology of Violence, 2(2), 125–138. DOI: 10.1037/a0027264 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy TM, & Ceballo R (2016). Emotionally numb: Desensitization to community violence exposure among urban youth. Developmental Psychology, 52(5), 778–789. DOI: 10.1037/dev0000112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinsfogel KM, & Grych JH (2004). Interparental conflict and adolescent dating relationships: Integrating cognitive, emotional, and peer influences. Journal of Family Psychology, 18(3), 505–515. DOI: 10.1037/0893-3200.18.3.505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB (2016). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (4th ed.). New York, NY: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lichter EL, & McCloskey LA (2004). The effects of childhood exposure to marital violence on adolescent gender-role beliefs and dating violence. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 28, 344–357. DOI: 10.1111/j.1471-6402.2004.00151.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Malik S, Sorenson SB, & Aneshensel CS (1997). Community and dating violence among adolescents: Perpetration and victimization. Journal of Adolescent Health, 21, 291–302. DOI: 10.1016/S1054-139X(97)00143-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mihalic SW, & Elliot D (1997). A social learning theory of marital violence. Journal of Family Violence, 12(1), 21–47. [Google Scholar]

- Miller S, Williams J, Cutbush S, Gibbs D, Clinton-Sherrod M, & Jones S (2013). Dating violence, bullying, and sexual harassment: Longitudinal profiles and transitions over time. Journal of Youth & Adolescence, 42, 607–618. DOI: 10.1007/s10964-013-9914-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris AM, Mrug S, & Windle M (2015). From family violence to dating violence: Testing a dual pathway model. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. DOI: 10.1007/s10964-015-0328-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthen LK, & Muthen BO (1998–2012). Mplus: Statistical analysis with latent variables. User’s Guide. Los Angeles: Muthen & Muthen. [Google Scholar]

- Mrug S, Loosier PS, & Windle M (2008). Violence exposure across multiple contexts: Individual and joint effects on adjustment. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 78(1), 70–84. DOI: 10.1037/0002-9432.78.1.70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mrug S, Madan A, & Windle M (2016). Emotional desensitization to violence contributes to adolescents’ violent behavior. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 44(1), 75–86. DOI: 10.1007/s10802-015-9986-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mrug S, & Windle M (2010). Prospective effects of violence exposure across multiple contexts on early adolescents’ internalizing and externalizing problems. The Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 51(8), 953–961. DOI: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02222.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng-Mak DS, Salzinger S, Feldman R, & Stueve A (2002). Normalization of violence among inner-city youth: A formulation for research. American Journal of Othopsychiatry, 72(1), 92–101. DOI: 10.1037/0002-9432.72.1.92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Keefe M (1998). Factors mediating the link between witnessing interparental violence and dating violence. Journal of Family Violence, 13(1), 39–57. [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary KD (1988). Physical aggression between spouses: A social learning theory perspective. In Van Hasselt VB, Morrison RL, Bellack AS, & Hersen M (Eds.), Handbook of family violence (pp. 39–55). New York: Plenum. [Google Scholar]

- Schnurr MP, & Lohman BJ (2008). How much does school matter? An examination of adolescent dating violence perpetration. Journal of Youth Adolescence, 37, 266–283. DOI: 10.1007/s10964-007-9246-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schnurr MP, & Lohman BJ (2013). The impact of collective efficacy on risks for adolescents’ perpetration of dating violence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 42, 518–535. DOI: 10.1007/s10964-013-9909-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seals D, & Young J (2003). Bullying and victimization: Prevalence and relationship to gender, grade level, ethnicity, self-esteem, and depression. Adolescence, 38(152), 735–747. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman JG, Raj A, Mucci LA, & Hathaway JE (2001). Dating violence against adolescent girls and associated substance use, unhealthy weight control, sexual risk behavior, pregnancy, and suicidality. Journal of the American Medical Association, 286(5), 572–579. DOI: 10.1001/jama.286.5.572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons RL, Lin K, & Gordon L (1998). Socialization in the family of origin and male dating violence: A prospective study. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 60, 467–478. DOI: 10.2307/353862 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith-Marek EN, Cafferky B, Dharnidharka P, Mallory AB, Dominguez M, High J, Stith SM, & Mendez M (2015). Effects of childhood experiences of family violence on adult partner violence: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 7, 498–519. DOI: 10.1111/jftr.12113 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stith SM, Rosen KH, Middleton KA, Busch AL, Lundeberg K, & Carlton RP (2000). The intergenerational transmission of spouse abuse: A meta-analysis. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 62, 640–654. DOI: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2000.00640.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA (2009). Why the overwhelming evidence on partner physical violence by women has not been perceived and is often denied. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment, & Trauma, 18, 552–571. DOI: 10.1080/10926770903103081 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Gelles RJ, & Steinmetz SK (1980). Behind closed doors: Violence in the American family. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Taft CT, O’Farrell TJ, Torres SE, Panuzio J, Monson CM, Murphy M, & Murphy CM (2006). Examining the correlates of psychological aggression among a community sample of couples. Journal of Family Psychology, 20(4), 581–588. DOI: 10.1037/0893-3200.20.4.581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vézina J, & Hébert M (2007). Risk factors for victimization in romantic relationships of young women: A review of empirical studies and implications for prevention. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 8(1), 33–66. DOI: 10.1177/1524838006297029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widom CS (1989a). Does violence beget violence? A critical examination of the literature. Psychological Bulletin, 106(1), 3–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams TS, Connolly J, Pepler D, Craig W, & Laporte L (2008). Risk models of dating aggression across different adolescent relationships: A developmental psychopathology approach. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 76, 622–632. DOI: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.4.622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf KA, & Foshee VA (2003). Family violence, anger expression styles, and adolescent dating violence. Journal of Family Violence, 18(6), 309–316. DOI: 10.1023/A:1026237914406 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe DA, Scott K, Reitzel-Jaffe D, Wekerle C, Grasley C, & Straatman A-L (2001). Development and validation of the conflict in adolescent dating relationship inventory. Psychological Assessment, 13(2), 277–293. DOI: 10.1037///1040-3590.13.2.277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]