Abstract

The present study was the first one in which parental identity statuses were investigated from the point of view of the processual identity model. The aim was the observation of individual differences among parents in respect of their parental identity (identity statuses) and differences between parents with a different identity status. In the study, 709 parents between the ages of 20 and 40 participated (64.8% women). The obtained results support the hypothesis that five different identity statuses in the parental domain could be identified, that is: Achievement, Foreclosure, Searching Moratorium, Moratorium, and Diffusion. Furthermore, hypothesized differences between different statuses regarding personality traits and well‐being have also been observed. The present study suggests that parental identity, which is often overlooked by neo‐Eriksonian identity researchers, is a fully‐fledged identity domain related to parents’ personality and well‐being and contextual factors associated with family life. The importance of the obtained results for our understanding of parental identity formation is discussed in the article.

Keywords: parental identity, parenting identity, U‐MICS, identity status, cluster analysis

Introduction

Parenthood is one of the most important roles of adulthood. Despite an increase in the rate of childlessness in the last few decades (Sobotka, 2017) and undertaking the parental role later in life in developed countries (Barclay & Myrskylä, 2016), still the vast majority of people become parents in their lives. Becoming a parent is an important turning point in a person's life, which may lead to changes of a biological, social and emotional functioning (Kohn, Rholes, Simpson, Martin, Tran & Wilson, 2012; McKenzie & Carter, 2013; Piotrowski, Brzezińska & Luyckx, 2020). Also, in people's subjective appraisal, parenthood is one of the most important social roles (Kerpelman & Schvaneveldt, 1999). Studies have shown, however, that although parenthood has developmental potential, it also carries a risk of disturbing parents' functioning. On the one hand, parenthood can give meaning to a person's life and be a source of satisfaction and personality development, but, on the other hand, parents are subject to parental stress, fatigue and limitation of the ability to satisfy their own needs, which can even lead to emotional disorders and parental burnout (Antonucci & Mikus, 1988; Doss & Rhoades, 2017; Hutteman, Hennecke, Orth, Reitz & Specht, 2014; Roskam, Raes & Mikolajczak, 2017). Searching for an answer to the question about causes of these different developmental trajectories, researchers point to demographic and social factors, as well as personality traits of parents (Nelson, Kushlev & Lyubomirsky, 2014; Oosterman, Schuengel, Forrer & De Moor, 2019; Petch & Halford, 2008). Mikolajczak, Gross and Roskam (2019) have recently conducted a review of studies on parental burnout observing that parents who are more prone to parental burnout have a high level of neuroticism, have poor stress management skills, are perfectionists and have poor parenting competences. On the other hand, high satisfaction from parenthood can be observed in parents with high levels of meaningfulness in life, whose basic needs are satisfied and who are prone to positive emotionality (Nelson et al., 2014).

Studies on factors that are conducive to the emergence of individual differences in respect of the adaptation to parenthood are crucial not only for a better understanding of the development of parents themselves, but also of their children. A high level of parental well‐being is connected with employing more optimal parenting methods (Fadjukoff, Pulkinnen, Lyyra & Kokko, 2016), whereas parental burnout increases the risk of using physical violence towards the child and developing authoritarian attitudes (Mikolajczak, Brianda, Avalosse & Roskam, 2018). Studies on factors that influence the adaptation to parenthood are, unfortunately, scarce, and they constitute a mosaic of diverse, potential causes. A factor that can help us better understand these dependencies is sense of parental identity (Delmore‐Ko, Pancer, Hunsberger & Pratt, 2000; Fadjukoff et al., 2016; Piotrowski, 2018), which may play the role of a mediator between individual and contextual factors and the person's functioning in the role of a parent.

A sense of identity is a personality characteristic taking the form of self‐definition that develops from adolescence (Erikson, 1950; Marcia, 1966). Forming and maintaining a stable sense of identity is one of the most important developmental tasks a person faces (Erikson, 1950). Marcia (1966), developing Erikson's (1950) theory, stated that identity development follows two processes: exploration, which is the consideration of various alternatives regarding, for example, political, religious, and occupational views, and commitment, which is the making of long‐term decisions in these areas that lead to the determination of one's identity. By assessing the intensity of exploration and commitment, it is possible to determine what identity status the individual currently has: Achievement (firm commitments made after a period of intensive exploration), Foreclosure (firm commitments without prior exploration), Moratorium (lack of firm commitments and current exploration) or Diffusion (lack of strong commitments and limited exploration). Consistent with Marcia's (1966) hypothesis, research has proven that individuals with Achievement status exhibit the best adjustment and individuals with Diffusion status experience the greatest severity of psycho‐social difficulties (Kroger & Marcia, 2011). Individuals with Foreclosure and Moratorium statuses tended to fall between these two extreme groups (Marcia, 1980). A major shift in identity research has been the emergence of the processual models by Luyckx, Schwartz, Berzonsky et al. (2008) and Crocetti, Rubini and Meeus (2008). These models allowed for a more detailed analysis of different forms of exploration and commitments, and allowed for the extraction of more specific identity statuses. Studies based on the processual models also confirmed that having clear and stable identity commitments across different domains is one of the key predictors of adaptation (Crocetti & Meeus, 2015). Unfortunately, in all these theoretical approaches, research on parental identity is rare. The purpose of the present study was to fill essential gaps in our knowledge of parental identity formation. Based on processual models this study set out to investigate which parental identity statuses can be observed among parents, whether individuals with different statuses differ in basic and specific personality traits (McAdams & Pals, 2006), and whether parental identity status is related to parents’ quality of life. It was assumed that adopting a person‐centered approach to the study of parental identity would enable the reliable observation of the diversity among parents in respect of their parental identity and capture parental identity complexity (Crocetti & Meeus, 2015).

Parental identity within the framework of identity status theory

Parental identity is a phenomenon that comprises the most important elements of the person's definition of oneself as a parent (What kind of parent do I want to be? Who am I as a parent?) and the degree of identification with the role of a parent (What does the role of a parent mean to me in my life?; Piotrowski, 2018). The foundations of a sense of parental identity are formed as early as adolescence, in the form of plans and expectations for parenthood (Delmore‐Ko, 2000; Gyberg & Frisén, 2017). This initial form of parental identity can then be revised when an individual is expecting their first child (Delmore‐Ko et al., 2000; Meca, Paulson, Webb, Kelley & Rodil, 2020), and after becoming a parent it is subject to further transformation as a result of specific experiences in the parental role (Fadjukoff et al., 2016; Piotrowski, 2018).

In their longitudinal study Fadjukoff et al. (2016) conducted interviews (three times: at the age of 36, 42 and 50) with 162 parents assessing the degree of commitment in the parental domain (the firmness of personal commitment to parenting) and the degree of exploration of parenting issues (the presence or absence of a period of reflection related to how the individual wants to pursue the parenting role). As predicted, they observed four identity statuses described by Marcia (1966): Achievement (a firm commitment in the parental domain preceded by a period of exploration of parental issues); Foreclosure (a firm commitment without a prior exploration of parental issues); Moratorium (lack of a firm commitment and an active, current exploration); and Diffusion (lack of commitment and lack of exploration of the parental issues). The study demonstrated an increase in the frequency of the identity Achievement in the analyzed period of time; however, it turned out that this identity status was characteristic mainly of women. Men far more frequently possessed the Foreclosure status. In this study, almost all parents turned out to possess one of these two statuses. The authors identified very few individuals with the statuses characterized by a low level of commitment (0–2% of Moratoriums in the different time points, 2–7% of Diffusions). Despite their infrequent occurrence, the individuals with the Diffusion status were characterized by higher parental stress, especially in the case of men. Regarding the importance of a parental identity status in fulfilling the parental role, it was observed that parents with the Achievement status more frequently used authoritative parenting methods, and were characterized by the highest level of generativity (Erikson, 1950) and the highest level of self‐perceived quality of life. Frisén and Wängqvist (2011) and Gyberg and Frisén (2017) used a similar methodology in their studies of young adults, and their observations were similar to the results of Fadjukoff et al. (2016). The vast majority of study participants were characterized by the committed statuses (Achievement and Foreclosure), and only a small group was characterized by the uncommitted statuses (Moratorium and Diffusion).

The studies by Fadjukoff et al. (2016), Frisén and Wängqvist (2011) and Gyberg and Frisén (2017) made it possible to better understand the role of parental identity, yet its results require broadening. For instance, why would such a small number of parents be characterized by the uncommitted statuses? Was it the result of the applied research method (interviews) or basing the studies on the classic identity status model of Marcia, which has recently met with significant criticism regarding the possibility of capturing developmental change within this theory (Meeus, 2018)? It needs to be emphasized that in the case of such a sensitive sphere as parenthood, the applied interview method could have resulted in restricting the participants' openness, which is why the dark side of parental identity failed to be captured. Or maybe in fact, the parental domain is so important for people that we seldom can observe in it uncertainty and diffusion?

Further development of research on parental identity status might be provided by studies based on processual models (Crocetti, Rubini & Meeus, 2008; Luyckx et al., 2008), which give opportunities to observe current difficulties with identity formation. Studies on the identity statuses conducted with the use of processual models (Crocetti, Rubini & Meeus, 2008; Luyckx et al., 2008) point to large individual differences, ranging from very strong commitment to very strong uncertainty, desire to change identity and difficulties with commitment‐making. Unfortunately, no research on identity statuses in the parental domain has been conducted within the processual approach to date. As one of the most important processual models used in identity research (Crocetti, Rubini & Meeus, 2008) has recently been adapted to study parental identity (Piotrowski, 2018), this approach has been used to fill in existing gaps.

The three‐dimensional model of identity formation

Meeus and Crocetti's (Crocetti, Rubini & Meeus, 2008) three‐dimensional model was developed as an extension of Marcia's (1966) theory. The authors pointed out that Marcia's model does not sufficiently analyze identity development after commitment making and distinguished three dimensions on which identity development takes place: commitment, which indicates whether an individual has made important decisions in identity domains such as education, work, and close relationships; in‐depth exploration, which is a reflective process of seeking in‐depth information about commitments made and which supports identity maintenance; and reconsideration of commitment, which is a process of comparing currently made commitments with alternative paths of identity development. High reconsideration of commitment indicates a current identity crisis resulting from the perception of commitments made as unsatisfactory and inconsistent with the individual's expectations. The research focused on the correlates of these three identity processes has revealed that commitment positively and reconsideration of commitment negatively correlate with adjustment, while in‐depth exploration is less significant for the quality of life (Crocetti, Klimstra, Keijsers, Hale & Meeus, 2009; Karaś, Cieciuch, Negru & Crocetti, 2015). Besides studies on correlates of the three identity processes, the Meeus–Crocetti model has been applied in studies on identity statuses understood as a configuration of three processes (similarly to Marcia's model, in which identity status is based on two processes).

Crocetti, Rubini, Luyckx & Meeus (2008) and Crocetti, Schwartz, Fermani, Klimstra & Meeus (2012); for a review see Crocetti, 2018; Meeus, 2018) have observed in adolescent samples five different identity statuses in such domains as education and close relationships: Achievement (high commitment, high in‐depth exploration, low reconsideration); Foreclosure (moderately high commitment, moderate/low scores on in‐depth exploration and low reconsideration of commitment); Moratorium (low commitment and in‐depth exploration, high reconsideration of commitment); Searching Moratorium (high levels of commitment, in‐depth exploration and reconsideration of commitment); and Diffusion (low levels of commitment, in‐depth exploration and reconsideration of commitment). Concerning the basic personality traits described in the Big Five model (Costa & McCrae, 1992; Crocetti, Rubini, Luyckx & Meeus 2008) found that achieved individuals were characterized by a mature personality profile (Caspi, Roberts & Shiner, 2005) with high extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness and openness to experience. Foreclosed individuals were similar to achieved individuals, although they scored slightly lower on openness to experience, conscientiousness, and agreeableness. At the same time, both statuses were characterized by an equally high quality of life and low intensity of psycho‐social problems (Crocetti, Rubini, Luyckx & Meeus, 2008). In contrast, individuals in Moratorium status were characterized by significantly lower extraversion, agreeableness, and emotional stability, and significantly higher severity of psycho‐social problems than Achievement and Foreclosure. Individuals in Searching moratorium status were personality‐wise similar to Moratorium, although it has also been shown that they may be characterized by higher extraversion and agreeableness (Hatano, Sugimura & Crocetti, 2016). Searching moratorium was also associated with significantly lower levels of psycho‐social problems than Moratorium (Crocetti, Rubini, Luyckx, et al., 2008). Individuals with Diffusion status were similar in personality traits to those with Searching moratorium status. Research on the role of more specific personality characteristics such as self‐concept clarity, aggression, and attachment style (Morsunbul, Crocetti, Cok & Meeus, 2016) has also led to similar observations regarding the functioning of individuals with different identity statuses.

Although the previous studies have reached important conclusions about the relationship between personality traits, identity statuses, and quality of life, a major limitation of these studies is that they have been conducted primarily among adolescents and emerging adults (Arnett, 2000, defines emerging adulthood as falling between the ages of 18 and 29, but previous research on the three‐dimensional model has rarely involved individuals older than 25) and have addressed a narrow range of identity domains that are central to people in these developmental periods, namely, interpersonal relationships and education. In contrast, the very few studies based on the three‐dimensional model in adulthood (Arneaud, Alea & Espinet, 2016; Crocetti, Avanzi, Hawk, Fraccarolli & Meeus, 2014), while confirming prior differences between identity statuses in terms of quality of life, have overlooked the issue of personality traits. Consequently, our knowledge of the personality correlates of identity statuses within the three‐dimensional model is limited to a small number of domains and individuals in adolescence and emerging adulthood. The parental identity domain has not been the focus of this type of research at all, not only within the three‐dimensional model (Crocetti, Rubini & Meeus, 2008) but within processual models in general.

The three‐dimensional model in the parental domain

According to Piotrowski's (2018) adaptation of the Meeus‐Crocetti model, when a person is expecting a child or becomes a parent, this role induces the incorporation of new content into the identity (Me as a parent), which can be observed in the level of parental identity commitment. Realizing the role of a parent in the following months, years and decades, the person conducts two types of exploration (Crocetti, Rubini & Meeus, 2008). In‐depth exploration is collecting deepened information on parenthood, the child and on oneself as a parent (What is it like to be a parent? What does it mean to me?). A high level of this reflective process supports commitment, leading to the stabilization of identity by supporting the formation of a clear definition of self as a parent. The other type of exploration is reconsideration of commitment, that is, comparing the person's present identity (being a parent) with an alternative one: one without children. A low level of reconsideration of commitment suggests that the person accepts and identifies strongly with the role of a parent, that Me as a parent is an important and satisfying element of the person's identity. High reconsideration of commitment can point to regrets, not accepting parenthood – dreaming of how good it would have been not to become a parent – and thus changing one's identity. In a series of studies conducted in Poland, Piotrowski (2018, 2020) has demonstrated that strong commitment is in fact a frequent situation, as the earlier studies suggested (Fadjukoff et al., 2016; Frisén & Wängqvist, 2011; Gyberg & Frisén, 2017). However, in the experience of some parents, one can also observe doubts about whether becoming a parent was a good decision, as well as a low identification with the parental role. Difficulties in forming stable, satisfaction‐yielding parental identity correlated (see Piotrowski, 2018, 2020, 2021) with anxiety, parental stress, the diffusion‐avoidant identity style (Berzonsky, 1989), attachment anxiety (Hazan & Shaver, 1987) and perfectionism (Hewitt & Flett, 1991). The three‐dimensional approach has subsequently become a basis for studies conducted by Meca et al. (2020) with a US sample. The authors demonstrated that a high level of reconsideration in the parental domain is linked to both stronger anxiety and stronger depression symptoms in parents. In turn, Schrooyen, Beyers and Soenens (2019) and Schrooyen et al. (2021), who also applied the processual approach in their studies on parental identity conducted on a Belgian sample, have observed that the difficulty in forming a clear vision of oneself as a parent is connected with negative parental experiences, mental health issues, and a greater risk of experiencing parental burnout (Mikolajczak et al., 2019). In sum, studies based upon the processual models conducted thus far (Meca et al., 2020; Piotrowski, 2018, 2020; Schrooyen et al., 2021) have univocally indicated that in the development of parental identity, we can observe difficulties that for parents can have serious consequences in the form of low quality of life and psychopathology risk. Thus, it can be predicted that by using the identity status approach and focusing on different configurations of identity processes (commitment, in‐depth exploration, reconsideration of commitment), it would be possible to observe both those parents who are characterized by healthy parental identity development (high commitment and/or low reconsideration of commitment) and those who experience significant difficulties in this process (high reconsideration of commitment).

The present study was the first one in which parental identity statuses were investigated from the point of view of the processual identity model (Crocetti, Rubini & Meeus, 2008; Piotrowski, 2018). It was assumed that adopting such an approach would not only enable the reliable observation of the individual differences in respect of parental identity, but that it would also capture to a greater extent the identity statuses characterized by a lower level of development, which was not accomplished in the earlier studies (Fadjukoff et al., 2016; Gyberg & Frisén, 2017). In line with previous research indicating the correlation of identity processes in the parental domain with personality traits (Piotrowski, 2018, 2020) and quality of life (Fadjukoff et al., 2016; Meca et al., 2020; Piotrowski, 2021) it was also decided to verify whether parents with different parental identity statuses differ in this respect.

Problem and hypotheses

The main objective of this study was to distinguish, for the first time, the parental identity statuses based on the dual‐cycle, processual Meeus–Crocetti model in samples of mothers and fathers. The focus was on parents in emerging adulthood (aged 18–29; Arnett, 2000) and early adulthood (from 30 to 40 years of age), so that the participants would still be strongly involved in the realization of the parental role due to the relatively low age of their children. Day‐to‐day involvement in the parental role was seen as a factor that could stimulate the process of parental identity formation and thus enable the relationship between parental identity construction and personality and quality of life to be fully revealed (Klimstra, Luyckx, Hale et al., 2010). Individuals above the age of 30 have so far been underrepresented in studies on identity within the dual‐cycle models, which was seen as an additional advantage of the study.

The second objective of the presented study was to evaluate the distinguished identity statuses in respect of basic and specific personality traits and quality of life. Both the basic personality traits (McAdams & Pals, 2006), which influence the wide spectrum of psycho‐social functioning and have a strong genetic component (e.g., the Big Five traits), as well as more narrow, specific personality traits (characteristic adaptations; McAdams & Pals, 2006), which are an effect of an interaction with the environment and individual adoption of certain motives and styles of functioning (e.g., attachment style, perfectionism), turned out to be connected with identity statuses in domains other than the parental one (Crocetti, Rubini, Luyckx & Meeus, 2008; Morsunbul et al., 2016). The identity statuses based on the three‐dimensional model have also been supported to be associated with the quality of life and psychopathology (Hatano, Sugimura & Crocetti, 2016; Morsunbul et al., 2016). It was anticipated that basic and specific traits and the quality of life would also be related with the parental identity statuses.

Hypothesis 1

It has been assumed that similarly to earlier studies (Crocetti, Rubini, Luyckx, et al., 2008; Crocetti et al., 2012), in the parental domain we will also be able to observe five identity statuses based on different configurations of commitment, in‐depth exploration and reconsideration of commitment. Bearing in mind the varied results obtained by Arneaud et al. (2016) and Crocetti et al. (2014), it was also anticipated, however, that we might observe a different configuration and number of identity statuses, as well.

Hypothesis 2

In line with earlier variable‐centered studies, it has been assumed that parents with the identity statuses characterized by strong commitment and low reconsideration of commitment (Achievement and Foreclosure) will be characterized by personality traits associated with good adjustment, such as high extraversion, conscientiousness, agreeableness, openness, emotional stability, and optimism (Crocetti, Avanzi, Hawk, Fraccaroli & Meeus, 2014; Crocetti, Rubini, Luyckx, et al., 2008) and the highest quality of life (Morsunbul et al., 2016), whereas parents with low commitment and low exploration but with a strong reconsideration of commitment (if such a situation should arise) will be characterized by the highest level of personality characteristics related to psycho‐social difficulties such as perfectionism and indecisiveness (Piotrowski, 2020; Piotrowski & Bojanowska, 2021) and low quality of life (Meca et al., 2020; Piotrowski, 2018). It was predicted that parents with other identity statuses would have scores that placed them between these extremes (Crocetti, Rubini, Luyckx, et al., 2008).

Material and methods

The study was approved by the Departmental Ethics Committee (SWPS University, Poznań, Poland; decision number 180901). The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. A power analysis performed with the use of G*Power 3.1.9.4 software in order to determine the minimum required sample size suggested that about 290 participants were needed for MANOVA with six potential groups (clusters), a minimum effect size of .03 (Crocetti, Rubini, Luyckx, et al., 2008), alpha level 0.05 and a power of 0.95. Data was collected in 2019.

Participants

The participants were 716 Polish parents (464 women, 64.8%). About half of the sample, mostly men, was recruited via a research panel (Polish research panel ‘Ariadna’ was used; the panel has about 100,000 users and is used for conducting national, representative studies), and the other half with the method of convenience sampling. As a result of missing data inspection, seven persons, who failed to fill in ten or more values (usually it was associated with omitting one of the questionnaires), were deleted from the database. Among the remaining 709 people who were included in the sample, 652 individuals (92%) did not have missing data, and in the case of the rest of the participants, these were only single values and they were left unchanged. The participants of the study were between the ages of 20 and 40 (M age = 34.44, SD = 3.83, Median = 35; emerging adults, ages 29 and under, accounted for 10.2%, and young adults, ages 30–40, accounted for 89.8% of the sample). The maximum age limit had been decided upon before the study started. The investigated individuals had at least 1 (n = 374, 52.8%) to 7 (n = 1) children. The age of the children ranged from 1 month to 20 years, although in the majority of cases, the participants were the parents of young children (M age = 5.58, SD = 3.99, Me = 5). In the sample, there were 534 married individuals (75.3%), 139 in an informal relationship (19.6%) and 36 single people (5.1%). Of the participants, 334 individuals (47.5%) stated that they had no financial problems, 342 people (48.2%) said they had minor financial problems and 30 individuals (4.2%) claimed that they had serious financial problems.

Measures

Parental identity processes

The Utrecht‐Management of Identity Commitments Scale (U‐MICS; Crocetti, Rubini & Meeus, 2008) in the version for investigating parental identity (Piotrowski, 2018, 2020) was applied to measure three parental identity processes: commitment (5 items, e.g. Being a parent makes me feel sure of myself); in‐depth exploration (5 items, e.g. I try to find out a lot about my child/children); and reconsideration of commitment (3 items, e.g. I often think it would have been better not to have had any children). Investigated individuals would provide their answers on a five‐point Likert scale, ranging from 1‐completely untrue to 5‐completely true. The reliability of the subscales was 0.91, 0.77 and 0.91, respectively.

Personality

Four questionnaires were used to measure basic (Big Five) and specific personality traits (perfectionism, indecisiveness, and optimism). The Big Five traits were measured using the International Personality Item Pool‐Big Five Markers‐20 (IPIP‐BFM‐20; Topolewska, Skimina, Strus, Cieciuch & Rowiński, 2014) which is a short version of IPIP‐BFM‐50 (Donnellan, Oswald, Baird & Lucas, 2006). It is a 20‐item scale for measuring the Big Five traits with 4 items for each trait (e.g., extroversion: Am the life of the party). Each item is assessed on a five‐point Likert scale, ranging from 1, very inaccurate to 5, very accurate, Cronbach’s alphas were: extroversion 0.84; agreeablenesss 0.66; conscientiousness 0.76; emotional stability 0.73; and openness 0.71. Perfectionism was measured using three subscales from the Frost Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale (FMPS; Frost, Marten, Lahart & Rosenblate, 1990; Polish adaptation Piotrowski & Bojanowska, 2021): the Personal Standard subscale (7 items, e.g. It is important to me that I be thoroughly competent in everything I do) was applied to measure perfectionistic strivings, an adaptive aspect of perfectionism (Stoeber & Otto, 2006), and the sum of two other scales, Concern over Mistakes (9 items, e.g. If I fail at work/school, I am a failure as a person) and Doubts about Actions (4 items, e.g. Even when I do something very carefully, I often feel that it is not quite done right), was used as an indicator of perfectionistic concerns, a maladaptive aspect of perfectionism. Participants would provide their answers on a five‐point Likert scale, ranging from 1, completely untrue to 5, completely true, Cronbach’s alphas were 0.76 and 0.90, respectively. Indecisiveness was measured using the Frost Indecisiveness Scale (FIS; Frost & Shows, 1993, Polish adaptation Piotrowski & Brzezińska, 2017), a 15‐item scale for measuring difficulties with decision making (e.g., I often worry about making the wrong choice). Each item is assessed on a five‐point Likert scale from 1, strongly disagree to 5‐strongly agree. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.90. Optimism was measured using the Life Orientation Test‐Revised (LOT‐R; Scheier, Carver & Bridges, 1994), a scale for measuring dispositional optimism. It is a ten‐item scale, with six items measuring optimism (e.g., In uncertain times, I usually expect the best) and four fillers assessed on a five‐point Likert scale from 1, I disagree a lot to 5, I agree a lot. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.75.

Quality of life

To assess quality of life the Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS; Diener, Emmons, Larsen & Griffin, 1985; Polish adaptation: Jankowski, 2015) was used to measure general life satisfaction (5 items; e.g., In most ways my life is close to my ideal). Each item was assessed on a five‐point Likert scale from 1, Strongly disagree to 5, Strongly agree. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.88.

Analytical strategy

Pearson's r correlation analysis was applied in order to learn about relationships between the parental identity dimensions and the remaining variables: five basic personality traits (extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, emotional stability, and openness), three specific personality traits (perfectionism, indecisiveness, and optimism), and satisfaction with life. Next, clusters of parental identity were distinguished. Distinguishing the clusters, the two‐step method advised by Gore (2000) and frequently applied in studies on the identity statuses (Crocetti, Rubini, Luyckx, et al., 2008; Luyckx et al., 2008) was used. In the first step, the results on the three dimensions of parental identity were standardized, and outliers were removed (univariate outliers were individuals with +‐ 3SD on any dimension, and multivariate outliers were individuals with high Mahalanobis distance, p < 0.001). Subsequently, a hierarchical analysis with the use of Ward's method was conducted (in subsequent analyses, 3, 4, 5 and 6 clusters were distinguished), and the initial centers of clusters obtained in the hierarchical analysis were used in the next step, to distinguish clusters using the k‐means method. The clusters distinguished in such a way were subjected to the evaluation in order to select the most optimal solution. Attention was paid to their theoretical validity (Crocetti, Rubini, Luyckx, et al., 2008); to parsimony (each cluster should be characterized by a different configuration of the dimensions); and to explanatory power (the percentage of the variance of each dimension explained by the given cluster solution should be at least 50%; Crocetti, Rubini, Luyckx, et al., 2008). In the next step, a multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was conducted in order to compare the clusters in respect of the levels of the remaining variables. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 26 (IBM Corp., 2019).

Results

Correlational analysis

The correlations between the parental identity dimensions and the remaining variables are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics and correlational analysis of the analyzed variables

| Min | Max | M | SD | Commitment | In‐depth exploration | Reconsideration of commitment | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Commitment | 1.00 | 5.00 | 3.66 | 0.88 | – | 0.34*** | −0.45*** |

| 2. In‐depth exploration | 2.20 | 5.00 | 3.98 | 0.62 | 0.34*** | – | −0.24*** |

| 3. Reconsideration of commitment | 1.00 | 5.00 | 1.53 | 0.88 | −0.45*** | −0.24** | – |

| 4. Extraversion | 1.00 | 5.00 | 3.24 | 0.91 | 0.28*** | 0.15*** | −0.17*** |

| 5. Agreeableness | 1.00 | 5.00 | 3.80 | 0.66 | 0.26*** | 0.24*** | −0.30*** |

| 6. Conscientiousness | 1.00 | 5.00 | 3.49 | 0.82 | 0.11** | 0.07 | −0.06 |

| 7. Emotional stability | 1.00 | 4.75 | 2.85 | 0.81 | 0.23*** | −0.02 | −0.25*** |

| 8. Openness | 1.00 | 5.00 | 3.78 | 0.70 | 0.05 | 0.04 | −0.09* |

| 9. Perfectionistic strivings | 1.14 | 5.00 | 3.27 | 0.72 | 0.09 | 0.06 | 0.04 |

| 10. Perfectionistic concerns | 1.00 | 5.00 | 2.41 | 0.83 | −0.23*** | −0.03 | 0.36*** |

| 11. Indecisiveness | 1.00 | 5.00 | 2.42 | 0.73 | −0.23*** | −0.04 | 0.23*** |

| 12. Optimism | 1.44 | 5.00 | 3.52 | 0.62 | 0.35*** | 0.14*** | −0.33*** |

| 13. Life satisfaction | 1.00 | 5.00 | 3.38 | 0.85 | 0.43*** | 0.20*** | −0.31*** |

p < 0.05,

p < 0.01,

p < 0.001.

The correlations between the three identity processes confirmed the earlier observations (Meca et al., 2020; Piotrowski, 2018). The data also revealed a picture of the relationships between the dimensions of parental identity, personality traits and satisfaction with life that was coherent and consistent with previous findings (Meca et al., 2020; Piotrowski, 2018, 2020, 2021). Parental identity commitment correlated positively with extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness and emotional stability, as well as with optimism and satisfaction with life, whereas it correlated negatively with perfectionistic concerns and indecisiveness. In the case of in‐depth exploration, the results confirmed its adaptive character, in the form of positive correlations with extraversion, agreeableness, optimism and satisfaction with life. In the case of reconsideration of commitment, negative relationships with extraversion, agreeableness, emotional stability and openness, optimism and satisfaction with life were observed. Reconsideration correlated positively, in turn, with perfectionistic concerns and indecisiveness.

Cluster analysis

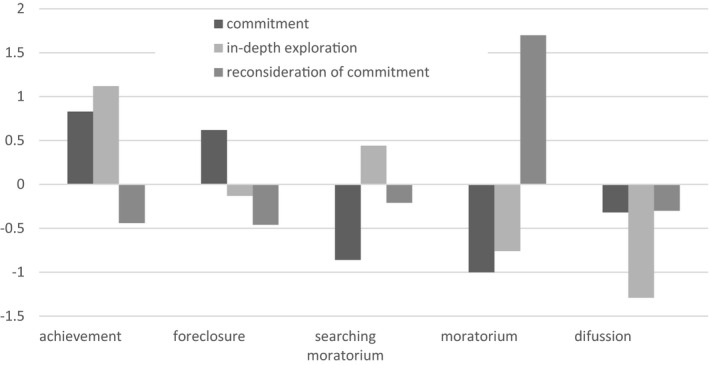

Before commencing the analysis, 11 outliers were deleted from the sample as they could disturb the analysis (Luyckx et al., 2008). In each case, these were simultaneously uni‐ and multivariate outliers. The cluster analysis was conducted on the total sample of 698 individuals (65.2% women). As a result of the comparison of different solutions, the following solutions were rejected: the 3‐cluster solution (too low percentage of the explained variance of the dimensions: from 41% to 71%); the 4‐cluster solution (in comparison with this solution, the 5‐cluster solution brought a new, specific configuration of the dimensions); and the 6‐cluster solution (in this case, two clusters were very similar to each other). The most optimal solution turned out to be the 5‐cluster solution, which explained 61–73% of the variance of the particular dimensions. All the obtained clusters were characterized by a different configuration of the identity processes, and they could be classified according to the definitions provided by Crocetti and Meeus (Crocetti, Rubini, Luyckx, et al., 2008). The clusters are presented in Fig. 1. The significance of differences in the levels of intensity of particular identity processes across statuses is included in the Supplementary Materials (Table S1).

Fig. 1.

Final cluster‐solution for the parental identity variables

Achievement (n = 162, 23.2% of the sample) is a cluster to which belonged the parents with high results on commitment and in‐depth exploration and low reconsideration of commitment. Foreclosure (n = 203, 29.1% of the sample) is a status characterized by high commitment, moderate exploration and relatively low reconsideration of commitment. Searching moratorium (n = 127, 18.2% of the sample) is a status of the parents in the case of whom in‐depth exploration was brought to the forefront, with simultaneous low commitment and moderate reconsideration of commitment. Moratorium (n = 105, 15.0% of the sample) was characterized by low results on commitment and in‐depth exploration and high reconsideration of commitment. Diffusion (n = 101, 14.5% of the sample) was a cluster to which belonged the parents with moderate levels of commitment and reconsideration of commitment and with low levels of in‐depth exploration.

Mean differences between the parental identity statuses

MANOVA revealed a significant multivariate effect of the identity status, Wilks’ λ = 0.73, F(40, 2,595) = 5.53, p < 0.001, η 2 = 0.08 (all the remaining variables, i.e., personality traits and quality of life, were treated as dependent variables). Table 2 presents the results of univariate analyses, enabling a better insight into the obtained dependencies.

Table 2.

Univariate ANOVA's and post‐hoc comparisons based upon Tukey HSD tests for the five parental identity clusters

| Parental identity statuses | F | eta2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Achievement | Foreclosure | Searching Moratorium | Moratorium | Diffusion | |||

| Extraversion | 3.51 (0.86)a | 3.34 (0.87)a,b | 3.12 (0.91)b,c | 2.97 (0.93)c | 3.13 (0.87)b,c | 7.88*** | 0.04 |

| Agreeableness | 3.98 (0.61)a | 3.96 (0.58)a | 3.83 (0.63)a | 3.48 (0.67)b | 3.58 (0.69)b | 16.41*** | 0.09 |

| Conscientiousness | 3.59 (0.85) | 3.55 (0.77) | 3.38 (0.88) | 3.42 (0.78) | 3.43 (0.77) | ns | 0.01 |

| Emotional stability | 2.91 (0.77)a | 3.02 (0.75)a | 2.77 (0.82)a | 2.47 (0.75)b | 3.02 (0.80)a | 10.27*** | 0.06 |

| Openness | 3.86 (0.67)a | 3.80 (0.70)a | 3.72 (0.73)a,b | 3.56 (0.73)b | 3.86 (0.61)a | 3.66** | 0.02 |

| Perfectionistic strivings | 3.37 (0.64) | 3.26 (0.67) | 3.14 (0.81) | 3.22 (0.71) | 3.26 (0.76) | ns | 0.01 |

| Perfectionistic concerns | 2.31 (0.77)b,c | 2.20 (0.70)c | 2.47 (0.89)b | 2.92 (0.79)a | 2.31 (0.79)b,c | 16.13*** | 0.09 |

| Indecisiveness | 2.31 (0.73)b,c | 2.26 (0.63)c | 2.53 (0.76)b | 2.78 (0.70)a | 2.39 (0.73)b,c | 11.43*** | 0.06 |

| Optimism | 3.65 (0.60)a,b | 3.71 (0.57)a | 3.49 (0.59)b | 3.07 (0.50)c | 3.50 (0.56)b | 24.07*** | 0.12 |

| Life satisfaction | 3.68 (0.73)a | 3.65 (0.70)a | 3.21 (0.79)b | 2.82 (0.87)c | 3.28 (0.82)b | 28.30*** | 0.14 |

Mean values with different indices (a, b, c) differ significantly (post‐hoc tests: Tukey HSD); SD values are put in bracket.

p < 0.05,

p < 0.01,

p < 0.001.

No differences among the statuses were observed in respect of conscientiousness and perfectionistic strivings. Between the status of Achievement and the status of Foreclosure, there were no significant differences in respect of any of the analyzed variables. The parents with the statuses of Achievement and Foreclosure were characterized by relatively high extraversion, agreeableness, emotional stability and openness, as well as low perfectionistic concerns and low indecisiveness. In both of these groups, we could also observe a higher level of optimism and satisfaction with life than in the other statuses. The parents with the statuses of Searching moratorium, Moratorium and Diffusion were characterized by lower extraversion than the others, but the Searching moratorium status had higher scores in respect of agreeableness than Moratorium and Diffusion. On the other hand, Searching Moratorium and Diffusion were similar to each other in respect of emotional stability and openness. In this case, the status of Moratorium distinguished itself by the lowest emotional stability out of all the other identity statuses and the lowest result on the dimension of openness.

Although parents with different identity statuses did not differ from one another in the level of perfectionistic strivings (motivation to achieve perfection), they differed significantly in perfectionistic concerns (fear of failure, fear of criticism). The parents with the Moratorium status had the highest result in this respect. The parents with the statuses of Achievement, Searching Moratorium, and Diffusion obtained moderate scores, and Foreclosure parents were characterized by the lowest results in this respect. Similar differences were observed in the case of indecisiveness.

The individuals with the statuses of Searching moratorium and of Diffusion were characterized by slightly lower optimism and lower satisfaction with life than the individuals with the statuses of Achievement and Foreclosure. However, they still had higher results than the individuals in the Moratorium cluster, where both optimism and satisfaction with life had the lowest values in the investigated sample.

Additional analyses

Although this was not the primary purpose of the study, as part of additional analyses it was verified whether there was a link between the identity statuses and socio‐demographic factors: gender, age of participants, educational level, number and age of children, age of becoming a parent for the first time, marital status, and financial situation. Of all the variables analyzed, only two were found to be significantly associated with parental identity status: gender, X 2 (4, N = 698) = 26.52, p < 0.001, and financial situation, X 2 (8, N = 698) = 29.58, p < 0.001 (Table 3).

Table 3.

Percentages of participants in the different identity statuses by gender and financial situation

| Parental identity statuses | Chi2 | Cramer’s V | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Achievement | Foreclosure | Searching Moratorium | Moratorium | Diffusion | |||

| Gender | 26.52*** | 0.19 | |||||

| Women | 26.6% (n = 121) | 28.8% (n = 131) | 20.9% (n = 95) | 12.3% (n = 56) | 11.4% (n = 52) | ||

| Men | 16.9% (n = 41) | 29.6% (n = 72) | 13.2% (n = 32) | 20.2% (n = 49) | 20.2% (n = 49) | ||

| Financial situation | 29.58*** | 0.15 | |||||

| No financial problems | 24.3% (n = 81) | 30.9% (n = 103) | 19.5% (n = 65) | 9.9% (n = 33) | 15.3% (n = 51) | ||

| Minor financial problems | 22.9% (n = 77) | 28.6% (n = 96) | 17% (n = 57) | 17.6% (n = 59) | 14% (n = 47) | ||

| Serious financial problems | 13.8% (n = 4) | 13.8% (n = 4) | 17.2% (n = 5) | 44.8% (n = 13) | 10.3% (n = 3) | ||

p < 0.05,

p < 0.01,

p < 0.001.

Concerning gender, it turned out that women, more often than it would result from the random distribution (according to the adjusted standardized residuals; ADJR), had the status of Searching moratorium (20.9%, ADJR = 2.5) or Achievement (26.6%, ADJR = 2.9), while they less often had the status of Moratorium (12.3%, ADJR = –2.8) and Diffusion (11.4%, ADJR = –3.1). For men, the situation was the opposite. Moratorium (20.2%) and Diffusion (20.2%) statuses had an overrepresentation of males, while Searching Moratorium (13.2%) and Achievement (16.9%) statuses had a lower percentage of males than the random distribution would suggest. For Foreclosure status, the distribution of women and men was similar (ADJR = 0.02).

In the case of financial issues, the results indicated that those with serious financial problems were more likely to be in the Moratorium status (44%, ADJR = 4.6) than the random distribution would suggest, while they were less likely to be in Achievement (13.8%, ADJR = –1.2) and Foreclosure (13.8%, ADJR = –1.9) statuses. Those with minor financial problems were also overrepresented in Moratorium status (17.6%, ADJR = 1.8), although not as much as parents with serious financial issues. In contrast, parents with no financial problems were found to be less represented in Moratorium (ADJR = –3.6) status than the random distribution would suggest (9.9%). As can be seen, it was Moratorium status that was found to be most strongly associated with parents' financial situation.

Discussion

The present study was designed to better understand the foundation of individual differences in parental identity, and to enable further development of our knowledge about personality and well‐being correlates of identity development in the parental domain (Piotrowski, 2018). The scarce research into this issue conducted so far suggests that identity processes that take place in the parental domain have significant meaning for the adaptation to parenthood (Fadjukoff et al., 2016, Meca et al., 2020; Piotrowski, 2021, Schrooyen et al., 2021), and they can explain different developmental trajectories and psychopathological symptoms experienced by parents (Meca et al., 2020; Schrooyen et al., 2021).

Identity statuses in the parental domain

The obtained results confirmed to a great extent the results observed in the other identity domains, indicating that in the domain of parental identity, we can also talk about five different identity statuses that correspond largely to Crocetti and Meeus’ assumptions (Crocetti, Rubini, Luyckx et al., 2008): Achievement (23.3% of the parents in the present study), Foreclosure (29.1% of the parents), Searching Moratorium (18.2% of the parents), Moratorium (15.0% of the parents), and Diffusion (15.0% of the parents). The conducted studies confirmed to the full extent the existence among parents of individuals who weakly identify with their role and experience significant uncertainty. These results constitute a significant complement to the qualitative studies conducted by Fadjukoff et al. (2016), Frisén and Wängqvist (2011), and Gyberg and Frisén (2017) and to quantitative studies by Meca et al. (2020), Piotrowski (2018, 2020, 2021), and Schrooyen et al. (2021).

Comparing the results with those obtained by Fadjukoff et al. (2016), Frisén and Wängqvist (2011), and Gyberg and Frisén (2017), we can conclude that studies on statuses of parental identity can to a large extent be dependent on the applied method. It seems that using multidimensional, processual approach can be a more successful technique to differentiate parents than an identity interview. Applying such a technique makes it possible to distinguish more precisely those parents who experience more difficulties, which makes it more likely to identify their potential causes. Also, we cannot rule out the possibility that using a method that guarantees parents more confidentiality results in greater admissions by a higher number of parents that they experience doubts and regrets associated with being a parent, which can be hampered during an interview. However, research on the parental identity status conducted within a qualitative methodology (e.g., Fadjukoff et al., 2016; Frisén & Wängqvist, 2011; Gyberg & Frisén, 2017) provides the opportunity for an in‐depth analysis of the course of exploration and commitment. The qualitative methodology also gives the chance to reveal the motives that drive the parent and their perception of parenting, which is difficult in quantitative research. Thus, an interesting future direction could be mixed‐methodology research, whereby questionnaire data can be used to determine identity status and interview data allow for in‐depth understandings of the perspective of the parents with different identity statuses.

The results obtained are also relevant to the further development of processual models, including the Meeus–Crocetti model (Crocetti, Rubini & Meeus, 2008). Research in the processual paradigm is heavily focused on studying adolescents and emerging adults. The studies rarely involve individuals older than 25. The results obtained support the extension of this research paradigm to other areas, both in terms of identity domains and developmental periods. The results obtained regarding the parental domain reveal that the three‐dimensional model (Crocetti, Rubini & Meeus, 2008) is a useful approach also in research conducted among adults. The fact that the same identity statuses can be distinguished in the parental domain in early adulthood (individuals in this period constituted the majority of the sample) as in other domains in adolescence (Crocetti, Rubini, Luyckx, et al., 2008), significantly supports the validity of the three‐dimensional model in adulthood and encourages to conducting research within other processual models (e.g., Luyckx et al., 2008) and in other domains that constitute the sense of identity of individuals in middle or late adulthood.

The fact that the identity statuses described by Meeus and Crocetti (Crocetti, Rubini, Luyckx, et al., 2008) are replicated across developmental periods and domains, also demonstrates a certain universality of the concept. The five distinctive, differing types/statuses reflect well the individual differences in identity development not only in adolescence and emerging adulthood but, perhaps, across the lifespan. The use of processual models, for the systematic study of adults appears to be a new and interesting area of research. Research on identity status based on qualitative methodology and conducted among individuals in middle adulthood, such as the study of Fadjukoff et al. (2016), also supports the rationale for this direction of development of the processual models.

Psycho‐social profiles of the parental identity statuses

The second hypothesis was the assumption about the existence of significant differences among parents with different statuses in respect of their personality traits and quality of life. In this case, the obtained results also support this hypothesis. Among the different parental identity statuses, we could observe a number of differences that remain in accordance with the findings of other researchers (Crocetti & Meeus, 2015), although not all clusters differed from one another to the same extent.

Studies that have been conducted for many years and have used various processual models (Crocetti, Rubini & Meeus, 2008; Luyckx et al., 2008) prove that among the identity statuses, there are two – Achievement and Foreclosure – that distinguish themselves with the highest level of adjustment and well‐being. The situation is no different in the parental domain. Between these two statuses, we could observe practically no significant differences in respect of the analyzed variables. High similarity of both of these statuses in respect of personality was also observed by other researchers (Morsunbul et al., 2016). The profile of personality traits observed in these groups in the present study suggests that Achievement and Foreclosure parental identity statuses are more often developed by parents with a personality type described as Resilient (relatively high scores on all Big Five dimensions except neuroticism; Asendorph, Borkenau, Ostendorf & Van Aken, 2001), which is also identified with a mature personality (Caspi et al., 2005). Such individuals cope better with stress, are more competent in resolving conflicts with their romantic partner, and as parents are characterized by higher sensitivity and parenting competence (Caspi et al., 2005), making their parenting experience more positive. Individuals of the Resilient type are also more optimistic (Sharpe, Martin & Roth, 2011) and have more ease in making decisions (Germeijs & Verschueren, 2011) which was also revealed in the presented study. The present results indicate that individuals with the Resilient type may also identify more strongly with the parental role and exhibit a better defined and more stable parental identity, which is also in line with studies on the personality‐identity link in other domains (Luyckx, Teppers, Klimstra & Rassart, 2014). A question worth asking here is: How, therefore, do parents with Achievement and Foreclosure statuses differ from each other? Based on the results of an earlier study by Piotrowski (2018), it is plausible that even if parents with Achievement and Foreclosure statuses do not differ in terms of personality traits, they use different identity formation strategies. Piotrowski (2018) found that in‐depth exploration in the parental domain correlates positively with the informational identity style (individuals with this identity style tend to be self‐reflective and skeptical; they intentionally evaluate self‐relevant information; Berzonsky, 1989). This suggests that it may be in the Achievement status that there is a higher intensity of information style (in‐depth exploration is higher in this status than in the Foreclosure status), which is associated with more proactive and reflective identity construction. This prediction is in line with other research on the relationship between identity style and identity statuses (Berzonsky, 1989). Thus, future research is worthwhile in examining in detail the relationship between parental identity and identity styles.

The parents with the Searching moratorium status were characterized by comparable levels of agreeableness, conscientiousness, emotional stability and openness to the parents with the status of Achievement and Foreclosure, but were less extraverted, slightly less optimistic and slightly less satisfied with their lives. In respect of the level of perfectionism and indecisiveness they also did not differ from the parents with the status of Achievement and Foreclosure. Although the parents with the Searching moratorium status can face certain difficulties associated with the adaptation to parenthood, these difficulties do not seem to result from highly stable personality reasons, but rather, from situational causes or factors associated with their parenting skills. The individuals from this group did not differ significantly in respect of their personality profile from the parents with the status of Achievement and Foreclosure (which suggests that they are also characterized by a relatively mature personality; Caspi et al., 2005), yet they were distinguished by higher levels of stress and tension and a lower satisfaction with life. This agrees with perceiving Searching Moratorium as adaptive Moratorium that can end with undertaking identity commitment in the future, but is also associated with some level of stress and anxiety (Crocetti, Rubini, Luyckx et al., 2008).

Moratorium is a status that in the typology of Meeus–Crocetti is characterized by the greatest difficulties, both when it comes to forming a stable identity and experiencing psycho‐social difficulties (Crocetti & Meeus, 2015). These conclusions also find confirmation in the parental domain. The parents with this identity status distinguished themselves markedly against the background of the remaining groups. Low emotional stability and low agreeableness in Moratorium status suggest that this group of parents may be more likely to include individuals characterized by the least mature personality, who tend to have volatile moods, react with negative emotions in many situations, and little focus on building positive relationships (Caspi et al., 2005). Low emotional stability and a tendency toward negative emotionality, pessimism, perfectionistic concerns is characteristic of a personality type called Overcontroller (Asendorph et al., 2001; Donellan & Robins, 2010; Stoeber & Otto, 2006). In contrast, low agreeableness is more typical of the Undercontroller type (Asendorph et al., 2001; Donellan & Robins, 2010), characterized by higher levels of aggression and hostility. Thus, the results indicate that individuals with both of these personality types (Over‐ and Undercontrolled) may be common among individuals with Moratorium identity status. This issue is worth addressing in future research.

Diffusion is a status of the parents characterized by moderate extraversion, but with relatively low (similar to that observed in the case of Moratorium) agreeableness. Yet, in respect of emotional stability and openness to experience, they were similar to the parents with the identities of Achievement and Foreclosure. Additionally, their perfectionistic concerns and difficulties in making decisions were rather moderate, whereas their optimism and satisfaction with life were lower than in the statuses of Achievement and Foreclosure, but still higher than in the Moratorium status.

It can be concluded that the predicted dependencies pertaining to the relation of personality and parental identity have been confirmed, noting that the differences between the status of Achievement and the status of Foreclosure turned out to be smaller than anticipated. However, consistent with previous research (Crocetti, 2018; Crocetti & Meeus, 2015; Luyckx et al., 2014), in the parental domain, as in other identity domains, basic and specific personality traits seem to be associated with the formation of a sense of identity, with a more mature personality being associated with more mature parental identity statuses. However, the causal relationship between personality and parental identity is still unexplored. Previous research focused on other identity domains suggests that there may be a reciprocal relationship between exploration and commitment and personality traits (Bleidorn et al., 2013) but in the parental identity domain such analyses have not yet been conducted, leaving room for further research.

Socio‐demographic factors and parental identity status

Fadjukoff et al. (2016), Frisén and Wängqvist (2011), and Gyberg and Frisén (2017) found that men are more often characterized by less mature parental identity than women. Similar findings were obtained in the present study. It was women who were more likely to develop Achievement status, while men were more likely to experience Diffusion, but also more likely to have the least adaptive identity status, namely Moratorium. It appears that despite many societal changes designed to support men in taking on the role of parent (e.g., the paternity leave to which men are entitled after they become parents), it is still difficult for many of them to develop a stable and clear parental identity. The difficulty men have in forming a parental identity seems to be firmly rooted in culture. The mother's role is better socially defined than the father's role (Schoppe‐Sullivan, Shafer, Olofson & Kamp Dush, 2021), and furthermore, girls are socialized to perform caregiving functions from an early age, which makes them more able to explore the parental domain (Fadjukoff et al., 2016). All of this means that it can still be difficult for men to find the answer to the question: What kind of parent do I want to be? In subsequent research on parental identity, it is worth addressing more deeply the reasons why males are more likely to form Moratorium or Diffusion status, as this has not been studied to date.

The financial situation of parents, which is related to parental stress, the quality of parental life, and the quality of the romantic relationship (Algarvio, Leal & Maroco, 2018; Nelson et al., 2014), also turned out to be important for the formation of parental identity status. Financial situation was mainly related to Moratorium status. Parents with Moratorium status were most prevalent among those with the worst (subjectively) financial situation. Financial problems are a well‐known and important risk factor in parents' lives (Waylen & Stewart‐Brown, 2010), which makes it much more difficult to cope with everyday challenges, not only parental ones. In a German study (YouGov, 2016), it has been shown that parents with financial problems are more likely to regret that they decided to have children at all. It may be that financially troubled parents have difficulty forming a stable sense of parental identity that accounts for why they begin to regret their decision to have a child. The role of gender and parental financial situation in the context of parental identity status still requires much research, which we hope will be conducted in the future.

Limitations and suggestions

The present research offers a great deal of new information about parental identity, but nevertheless, its results need to be analyzed in the context of significant limitations. First of all, the conclusions are based upon the results of a cross‐sectional study, which generates a need to conduct further studies in the longitudinal plan. Second, due to the fact that this was the first research to empirically distinguish the statuses of parental identity within the processual approach, the observations need to become a subject of verification, especially in cultures other than Polish. Third, the results come from self‐description measures, and thus, in the future it would be advisable to use other (e.g., behavioral) indicators of the functioning of parents with different statuses of parental identity. Fourth, the participants were mostly recruited with the use of convenience sampling which could limit representativeness of the results. Fifth, the theoretical model used (Crocetti, Rubini & Meeus, 2008; Piotrowski, 2018) allows for the study of parental identity among parents and those expecting the birth of their first child (Meca et al., 2020). However, as Gyberg and Frisén's (2017) study shows, it is worthwhile to study parental identity development also among people without children.

Conclusion

Studies on identity that have been conducted over the last few decades have led us to a conclusion that a sense of identity is not a uniform monolith, but rather, a system of domains loosely associated with one another that together build a sense of individual identity (Vosylis, Erentaitė & Crocetti, 2018). Parental identity has for many years remained unnoticed by researchers conducting studies within the Erikson–Marcia tradition but this situation has changed recently (Fadjukoff et al., 2016; Frisén & Wängqvist, 2011; Gyberg & Frisén, 2017; Meca et al., 2020; Piotrowski, 2018, 2021; Schrooyen et al., 2021). The results obtained in the present study lead to a conclusion that the parental domain is the subject of similar developmental mechanisms as other identity domains that build a person's general sense of identity and that parental identity development remains related to overall quality of life. There is great variation among parents in their sense of parental identity. Some are characterized by a strong identification with the role of a parent, and being a parent helps them better define who they are. Others, on the other hand, are characterized by uncertainty and confusion as parents, and their parental identity is poorly defined. The obtained results suggest that the quality of identity development is closely related to a wide range of personality traits, which may imply that parents with different personality traits cope differently with identity formation (Caspi et al., 2005), or that parental identity development may stimulate positive or negative personality changes, or, finally, that there are reciprocal relationships between these characteristics (Bleidorn et al., 2013). The long‐term interplay between parental identity and personality seem to be a new and exciting area that is worthy of further exploration.

Conflicts of interests

The author declares no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author Contributions

KP was responsible for study conceptualization, data collection, data preparation, data analysis, report writing.

Supporting information

Table S1. Mean differences in terms of identity processes across statuses: Unstandardized values.

Piotrowski, K. (2021). Parental identity status in emerging and early adulthood, personality, and well‐being: A cluster analytic approach. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 62, 820–832.

Data Availability Statement

The data and all materials used in this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

- Algarvio, S. , Leal, I. & Maroco, J. (2018). Parental stress scale: Validation study with a Portuguese population of parents of children from 3 to 10 years old. Journal of Child Health Care, 22, 563–576. 10.1177/1367493518764337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonucci, T. C. & Mikus, K. (1988). The power of parenthood: Personality and attitudinal changes during the transition to parenthood. In Michaels G. Y. & Goldberg W. A. (Eds.), The transition to parenthood. Current theory and research (pp. 62–85). New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Arneaud, M. J. , Alea, N. & Espinet, M. (2016). Identity development in Trinidad: Status differences by age, adulthood transitions, and culture. Identity, 16, 59–71. [Google Scholar]

- Arnett, J. J. (2000). Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist, 55(5), 469–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asendorph, J. B. , Borkenau, P. , Ostendorf, F. & Van Aken, M. A. G. (2001). Carving personality description at its joints: Confirmation of three replicable personality prototypes for both children and adults. European Journal of Personality, 15, 169–198. [Google Scholar]

- Barclay, K. & Myrskylä, M. (2016). Advanced maternal age and offspring outcomes: Reproductive aging and counterbalancing period trends. Population and Development Review, 42, 69–94. [Google Scholar]

- Berzonsky, M. D. (1989). Identity style: Conceptualization and measurement. Journal of Adolescent Research, 4, 268–282. [Google Scholar]

- Bleidorn, W. , Klimstra, T. A. , Denissen, J. J. A. , Rentfrow, P. J. , Potter, J. & Gosling, S. D. (2013). Personality maturation around the world: A cross‐cultural examination of social‐investment theory. Psychological Science, 24(12), 2530–2540. 10.1177/0956797613498396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi, A. , Roberts, B. W. & Shiner, R. L. (2005). Personality development: Stability and change. Annual Review of Psychology, 56, 453–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa, P. T. & McCrae, R. R. (1992). The five‐factor model of personality and its relevance to personality disorders. Journal of Personality Disorders, 6, 343–359. [Google Scholar]

- Crocetti, E. (2018). Identity dynamics in adolescence: Processes, antecedents, and consequences. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 15, 11–23. [Google Scholar]

- Crocetti, E. , Avanzi, L. , Hawk, S. T. , Fraccaroli, F. & Meeus, W. (2014). Personal and social facets of job identity: A person‐centered approach. Journal of Business and Psychology, 29, 281–300. [Google Scholar]

- Crocetti, E. , Klimstra, T. , Keijsers, L. , Hale, W. W. & Meeus, W. (2009). Anxiety trajectories and identity development in adolescence: A five‐wave longitudinal study. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 38, 839–849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crocetti, E. & Meeus, W. (2015). The identity statuses: Strengths of a person‐centered approach. In McLean K. C. & Syed M. (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of identity development (pp. 97–114). New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Crocetti, E. , Rubini, M. & Meeus, W. (2008). Capturing the dynamics of identity formation in various ethnic groups: Development and validation of a three‐dimensional model. Journal of Adolescence, 31, 207–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crocetti, E. , Rubini, M. , Luyckx, K. & Meeus, W. (2008). Identity formation in early and middle adolescents from various ethnic groups: From three dimensions to five statuses. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 37, 983–996. [Google Scholar]

- Crocetti, E. , Schwartz, S. J. , Fermani, A. , Klimstra, T. & Meeus, W. (2012). A cross‐national study of identity status in Dutch and Italian adolescents status distributions and correlates. European Psychologist, 17, 171–181. [Google Scholar]

- Delmore‐Ko, P. , Pancer, S. M. , Hunsberger, B. & Pratt, M. (2000). Becoming a parent: The relation between prenatal expectations and postnatal experience. Journal of Family Psychology, 14, 625–640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener, E. , Emmons, R. A. , Larsen, R. J. & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49, 71–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donnellan, M. B. , Oswald, F. L. , Baird, B. M. & Lucas, R. E. (2006). The Mini‐IPIP scales: Tiny yet‐effective measures of the Big Five Factors of personality. Psychological Assessment, 18, 192–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donnellan, M. B. & Robins, R. W. (2010). Resilient, overcontrolled, and undercontrolled personality types: Issues and controversies. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 4(11), 1070–1083. [Google Scholar]

- Doss, B. D. & Rhoades, G. K. (2017). The transition to parenthood: Impact on couples’ romantic relationship. Current Opinion in Psychology, 13, 25–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erikson, E. (1950). Childhood and society. New York: Norton. [Google Scholar]

- Fadjukoff, P. , Pulkinnen, L. , Lyyra, A.‐L. & Kokko, K. (2016). Parental identity and its relation to parenting and psychological functioning in middle age. Parenting: Science and Practice, 16, 87–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisén, A. & Wängqvist, M. (2011). Emerging adults in Sweden: Identity formation in the light of love, work, and family. Journal of Adolescent Research, 26, 200–221. [Google Scholar]

- Frost, R. O. , Marten, P. , Lahart, C. & Rosenblate, R. (1990). The dimensions of perfectionism. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 14, 449–468. [Google Scholar]

- Frost, R. O. & Shows, D. L. (1993). The nature and measurement of compulsive indecisiveness. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 31, 683–692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Germeijs, V. & Verschueren, K. (2011). Indecisiveness and Big Five personality factors: Relationship and specificity. Personality and Individual Differences, 50, 1023–1028. [Google Scholar]

- Gore, P. A. (2000). Cluster analysis. In Tinsley H. E. A. & Brown S. D. (Eds.), Handbook of applied multivariate statistics and mathematical modelling (pp. 297–321). San Diego, CA: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gyberg, F. & Frisén, A. (2017). Identity status, gender, and social comparison among young adults. Identity, 17, 239–252. [Google Scholar]

- Hatano, K. , Sugimura, K. & Crocetti, E. (2016). Looking at the dark and bright sides of identity formation: New insights from adolescents and emerging adults in Japan. Journal of Adolescence, 47, 156–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazan, C. & Shaver, P. (1987). Romantic love conceptualized as an attachment process. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52, 511–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewitt, P. L. & Fleet, G. L. (1991). Perfectionism in the self and social contexts: Conceptualization, assessment, and association with psychopathology. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 60, 456–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutteman, R. , Hennecke, M. , Orth, U. , Reitz, A. K. & Specht, J. (2014). Developmental tasks as a framework to study personality development in adulthood and old age. European Journal of Personality, 28, 267–278. [Google Scholar]

- IBM Corp . (2019). IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 26.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp. [Google Scholar]

- Jankowski, K. S. (2015). Is the shift in chronotype associated with an alteration in well‐being? Biological Rhythm Research, 46, 237–248. [Google Scholar]

- Karaś, D. , Cieciuch, J. , Negru, O. & Crocetti, E. (2015). Relationships between identity and well‐being in Italian, Polish, and Romanian emerging adults. Social Indicators Research, 121, 727–743. [Google Scholar]

- Kerpelman, J. L. & Schvaneveldt, P. L. (1999). Young adults’ anticipated identity importance of career, marital, and parental roles: Comparisons of men and women with different role balance orientations. Sex Roles, 41, 189–217. [Google Scholar]

- Klimstra, T. A. , Luyckx, K. , Hale, W. A. III , Frijns, T. , van Lier, P. A. C. & Meeus, W. H. J. (2010). Short‐term fluctuations in identity: Introducing a micro‐level approach to identity formation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 99, 191–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohn, J. L. , Rholes, W. S. , Simpson, J. A. , Martin, A. M. , Tran, S. & Wilson, C. L. (2012). Changes in marital satisfaction across the transition to parenthood: The role of adult attachment orientations. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 38, 1506–1522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroger, J. & Marcia, J. E. (2011). The identity statuses: Origins, meanings, and interpretations. In Schwartz S. J., Luyckx K. & Vignoles V. L. (Eds.), Handbook of identity theory and research (pp. 31–53). New York: Springer Science + Business Media. [Google Scholar]

- Luyckx, K. , Schwartz, S. J. , Berzonsky, M. D. , Soenens, B. , Vansteenkiste, M. , Smits, I. et al. (2008). Capturing ruminative exploration: Extending the four‐dimensional model of identity formation in late adolescence. Journal of Research in Personality, 42, 58–82. [Google Scholar]

- Luyckx, K. , Teppers, E. , Klimstra, T. A. & Rassart, J. (2014). Identity processes and personality traits and types in adolescence: Directionality of effects and developmental trajectories. Developmental Psychology, 50, 2144–2153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcia, J. E. (1966). Development and validation of ego‐identity status. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 3, 551–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcia, J. E. (1980). Identity in adolescence. In Adelson J. (Ed.), Handbook of adolescent psychology (pp. 159–187). New York: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- McAdams, D. P. & Pals, J. L. (2006). A new Big Five: Fundamental principles for an integrative science of personality. American Psychologist, 61, 204–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie, S. K. & Carter, K. (2013). Does transition into parenthood lead to changes in mental health? Findings from three waves of a population based panel study. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 67, 339–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meca, A. , Paulson, J. F. , Webb, T. N. , Kelley, M. L. & Rodil, J. C. (2020). Examination of the relationship between parenting identity and internalizing problems: A preliminary examination of gender and parental status differences. Identity, 20(2), 92–106. 10.1080/15283488.2020.1737070. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meeus, W. (2018). The identity status continuum revisited: A comparison of longitudinal findings with Marcia’s model and dual cycle models. European Psychologist, 23, 289–299. [Google Scholar]

- Mikolajczak, M. , Brianda, M. E. , Avalosse, H. & Roskam, I. (2018). Consequences of parental burnout: Its specific effect on child neglect and violence. Child Abuse & Neglect, 80, 134–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikolajczak, M. , Gross, J. J. & Roskam, I. (2019). Parental burnout: What is it, and why does it matter? Clinical Psychological Science, 7, 1319–1329. [Google Scholar]

- Morsunbul, U. , Crocetti, E. , Cok, F. & Meeus, W. (2016). Identity statuses and psycho‐social functioning in Turkish youth: A person‐centered approach. Journal of Adolescence, 47, 145–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, S. K. , Kushlev, K. & Lyubomirsky, S. (2014). The pains and pleasures of parenting: When, why, and how is parenthood associated with more or less well‐being? Psychological Bulletin, 140, 846–895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oosterman, M. , Schuengel, C. , Forrer, M. L. & De Moor, M. H. M. (2019). The impact of childhood trauma and psychophysiological reactivity on at‐risk women’s adjustment to parenthood. Development and Psychopathology, 31, 127–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petch, J. & Halford, W. K. (2008). Psycho‐education to enhance couples' transition to parenthood. Clinical Psychology Review, 7, 1125–1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piotrowski, K. (2018). Adaptation of the Utrecht‐Management of Identity Commitments Scale (U‐MICS) to the measurement of the parental identity domain. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 59, 157–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piotrowski, K. (2020). How good it would be to turn back time: Adult attachment and perfectionism in mothers and their relationships with the processes of parental identity formation. Psychologica Belgica, 60, 55–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piotrowski, K. (2021). Domain‐specific correlates of parental and romantic identity processes. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, Advance online publication. 10.1080/17405629.2021.1949979 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Piotrowski, K. & Bojanowska, A. (2021). Factor structure and psychometric properties of a Polish adaptation of the frost multidimensional perfectionism scale. Current Psychology, 40(6), 2754–2763. 10.1007/s12144-019-00198-w [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Piotrowski, K. & Brzezińska, A. I. (2017). Skala wymiarów rozwoju tożsamości DIDS: Wersja zrewidowana [Revised Polish adaptation of the DIDS; in Polish]. Psychologia Rozwojowa, 22, 89–111. [Google Scholar]