Abstract

A routine method for determining cannabinoids in Cannabis sativa L. inflorescence, based on Fast gas chromatography coupled to mass spectrometry (Fast GC/MS), was developed and validated. To avoid the decarboxylation of carboxyl group of cannabinoids, different derivatization approaches, i.e. silylation and esterification (diazomethane-mediated), reagents and solvents (pyridine or ethyl acetate), were tested. The methylation significantly increased the signal-to-noise ratio of all carboxylic cannabinoids, except for cannabigerolic acid (CBGA). Since diazomethane is not commercially available, is considered a hazardous reactive and requires 1-day synthesis by specialized chemical staff, silylation was used along the whole validation of a routine method. The method gave a fast (total analysis time < 7.0 min) and satisfactory resolution (R > 1.1), with a good repeatability (intraday < 8.38%; interday < 11.10%) and sensitivity (LOD < 11.20 ng/mL). The Fast GC/MS method suitability for detection of cannabinoids in hemp inflorescences, was tested; a good repeatability (intraday < 9.80%; interday < 8.63%), sensitivity (LOD < 58.89 ng/mg) and robustness (<9.52%) was also obtained. In the analyzed samples, the main cannabinoid was cannabidiolic acid (CBDA, 5.19 ± 0.58 g/100 g), followed by cannabidiol (CBD, 1.56 ± 0.03 g/100 g) and CBGA (0.83 g/100 g). Δ9-tetrahydrocannabivarine (THCV) was present at trace level. Therefore, the developed routine Fast GC/MS method could be a valid alternative for a fast, robust and high sensitive determination of main cannabinoids present in hemp inflorescences.

Keywords: Cannabinoids, Cannabis, Decarboxylation, Fast gas chromatography, Methylation

1. Introduction

Recently, the interest on Cannabis sativa L. has drastically increased. However, the main attention is generally addressed to psychoactive [1] and non-psychoactive compounds, such as Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (Δ9-THC) and cannabidiol (CBD). In the past, the genus Cannabis was allocated into three main species: drug-type (C. indica), with high levels of Δ9-THC, a fiber-type (C. sativa L.) with low levels of Δ9-THC and an intermediate one C. ruderalis Janish [2]. Recently, it was decided to classify all different species as C. sativa also called “hemp” when referred to industrial use (fiber-type), or “therapeutic” also called “marijuana” (drug-type) for the variety with high content of Δ9-THC (>0.6%; w/w). To date, the main use of hemp is largely related to food; in fact, hemp seeds are generally used for producing oil and flour and, depending on the Countries local regulations, they could or not be employed on the basis of their pharmacological properties [3]. However, hemp contains more than 500 different cannabinoids, of which about ten have been classified according to their chemical structure, such as Δ9-tetrahydrocannabivarin (THCV), cannabidiol (CBD), cannabigerol (CBG), Δ8-tetrahydrocannabinol (Δ8-THC), Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (Δ9-THC), cannabichromene (CBC), cannabinol (CBN), cannabidiolic acid (CBDA), Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinolic acid (THCA) and cannabigerolic acid (CBGA) [4].

Hemp cannabinoids exhibit diverse biological effects. THCV displays various pharmacological profile according to the type of molecular target (in vitro antagonistic/inverse agonistic effects and in vivo agonism effect in an anti-nociception model) [5]. The application of CBD for intractable pediatric epilepsy, has been recently studied [6]. On the other hand, CBC, which is particularly present in freshly harvested C. sativa, normalizes in vivo intestinal motility when intestinal inflammation occurs [7]. It should be pointed out that C. sativa does not produce Δ9-THC, CBD, CBG and CBC, but their respective carboxylic acid forms (precursors) Δ9-THCA, CBDA, CBGA and CBCA can undergo decarboxylation by heating or drying, and thus exhibit their corresponding biological effects [3]. The galenic preparations of cannabis (such as medicinal oils), which are important for the possibility to be employed as a whole set of cannabinoids, are characterized by a high variability [8] and require a robust, simple quality control for their titration.

Considering the abovementioned biological effects of cannabinoids, their analysis in cannabis is of great interest and importance. There are several analytical methods for determining cannabinoids, most of which use gas chromatography coupled to mass spectrometry (GC/MS) or flame ionization detector (GC/FID) and high-performance liquid chromatography coupled to mass spectrometry (LC/MS) or ultraviolet detector (LC/UV) [2–4,9–11].

When GC/MS is used, the electron impact ionization (EI) generates mass spectra, which can be compared with those present in compounds libraries for their identification. On the other hand, in LC/MS with electrospray (ESI) and atmospheric pressure chemical ionization (APCI), only molecular ions are generated without other useful fragments for compound characterization, so expensive equipment able to perform MS/MS experiments is required [12,13]. As reported in literature, the LC/MS sensitivity is lower than that of GC/MS [4]. However, there is a lot of criticism around the use of GC for cannabinoid analysis, since the high temperature of both injector and detector lead to decarboxylation of cannabinoid acids if not previously derivatized (such as silylation) [14,15]. Different silylation procedures, have been reported for this scope; Purschke et al. [16] utilized N-methyl-N-(trimethylsilyl)tri-fluoroacetamide (MSTFA), while other researchers used the combination of N, O-bis(trimethylsilyl)trifluoroacetamide (BSTFA) or MSTFA, with either trimethylchlorosilane (TMCS) or ethyl acetate [17]. However, no data are reported about esterification of cannabinoid carboxylic acids by diazomethane and the use of Fast-GC/MS for cannabinoid determination. Fast-GC/MS has demonstrated to provide the advantages of mass spectrometry boosted by the utilization of Fast chromatography. In fact, theuse of Fast GC/MS drastically reduces thetime of analysis without impairing sensitivity, resolution and other analytical parameters (such as repeatability and reproducibility). Fast GC/MS has been successfully utilized for the determination of cholesterol oxidation products in 3.5 min [18], phytosterols and phytostanols in milk dairy products in less than 10 min [19] and heroin and cocaine in 3 min [20].

To the best of our knowledge, no previous works have been published on the determination of cannabinoids in hemp in-florescences by Fast-GC/MS. The aim of this work was to develop and validate a Fast GC/MS method for determining the main cannabinoids (THCV, CBD, CBC, CBDA, THCA, Δ9-THC, Δ8-THC, CBG, CBN, and CBGA) in hemp inflorescences, as related to different derivatization reagents (silylation and esterification).

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Reagents and solvents

Chloroform, n-hexane, methanol and ethanol were purchased from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany). N° 1 filters (70 mm diameter) were used (Whatmann, Maidstone, England). N, O-Bis(-trimethylsilyl)trifluoroacetamide with trimethylchlorosilane (BSTFA:TMCS, 99:1, v/v), N-methyl-N-(trimethylsilyl)tri-fluoroacetamide:trimethylchlorosilane (MSTFA:TMCS, 99:1, v/v) and (trimethylsilyl)diazomethane solution were supplied by Sigma Aldrich (Germany). Certified phytocannabinoid mixture 1 (1 mg/mL in acetonitrile; containing cannabidiolic acid (CBDA), cannabigerolic acid (CBGA), cannabigerol (CBG), can-nabidiol (CBD), tetrahydrocannabinoid acid A (THCA), Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (Δ9-THC), Δ8-tetrahydrocannabinol (Δ8-THC) and cannabihromene (CBC) at 100 μg/mL of each compound), (−)-Δ9-THC-D3 (THCd3, 0.1 mg/mL in methanol), THCA (1.0 mg/mL in methanol) and Δ9-THC (0.1 mg/mL in methanol) were purchased from LGC Standards S.r.L. (Milano, Italy). Millipore membrane filters (0.45 μm and 0.20 μm) was supplied by Merck (Germany).

2.2. Sampling

Three different batches of hemp inflorescences (EU registered Cannabis sativa L. Futura 75 variety; fiber-type), harvested at different growing times (from middle July to the end of August 2017), were supplied by a local company (Green Valley Società Agricola S. R.L., Castelvecchio Subequo, Italy). Each batch was comprised of three independent samples (n = 3), where each sample included ten inflorescences from 10 different plants (n = 10). Before performing cannabinoids extraction, the collected samples were dried by natural ventilation at 32 ± 1 °C for 60 h. Afterwards, dried hemp’s apical and lateral peaks were sifted. The seeds with diameter >1 mm, were removed by sieving; finally, the material was ground with an analytical mill to obtain a homogeneous sample. The powdered samples were stored at −22 °C under nitrogen atmosphere, until the analysis.

2.3. Extraction

Twenty five mg of ground sample were weighed into a glass test tube and 1.5 mg of 5α-cholestane (internal standard 1, IS1) were added. The extraction was performed using 10 mL of a 9:1 (v/v) methanol/chloroform mixture. The sample was stirred for 15 min (350 oscillations/min), sonicated for 10 min, centrifuged (5 min at 1620 g) and the solvent was collected. The extraction was repeated twice and the surnatants were transferred into a 25 mL flask, which was made up to the flask volume with the same solvent. The extract was then filtered through a millipore filter (0.45 μm). One mL of the filtered extract was transferred to a glass tube that contained 0.5 μg of THCd3 (internal standard 2, IS2), taken to dryness under nitrogen flow and then derivatized.

2.4. Derivatization

Two different derivatization reactions were compared: methylation and silylation. For methylation, 1 mL of the filtered extract was added with IS2, dried under nitrogen flow, methylated with 300 μL of diazomethane, vortexed for 30 s and then dried under nitrogen flow. Silylation was then performed at 60 °C for 15 min, using 50 μL of pyridine and 150 μL of n-methyl-n-trimethylsilyltrifluoroacetamide + 1% of chlorotrimethylsilane (MSTFA-TMCS); the silylated sample was then dried at 40 °C and dissolved in 100 μL of n-hexane.

2.5. Fast gas chromatography (Fast GC/MS) analysis

The cannabinoids were determined with a Fast GC/MS Shi-madzu QP 2010 Plus instrument (Kyoto, Japan) equipped with a Restek RTX 5 column (0.1 μm film thickness, 10 m × 0.1 mm); helium was used as carrier gas (constant flow; linear velocity of 47.4 cm/s). The oven temperature was programmed from 180 °C (30 s) to 250 °C at 10 °C/min, and then to 350 °C (at 60 °C/min); final temperature was maintained for 5 min. The injector, interface and ion source temperatures were 300, 330 and 200 °C, respectively, while the filament voltage was 70 eV (electronic impact). One μL of derivatized sample was manually injected (split 1:30).

2.6. Validation of the method

The response linearity was evaluated by means of calibration curves. For each compound, a calibration curve in the concentration range of 0.25 ng/mL-25 μg/mL was built using the internal standard method. Six different concentration levels were tested in triplicates. The cannabinoids were recognized by their mass spectra and were quantified by single ion monitoring (SIM). In particular, 1 quantifier ion and 3 qualifier ions were used (Table 1) for both derivatization methods (methylation and silylation).

Table 1.

Characteristic ions of cannabinoids obtained by silylation (TMS) and methylation-silylation (MET-TMS) reactions.

| Cannabinoid | Quantifier ion (m/z) | Qualifier ions (m/z) |

|---|---|---|

| THCV-1TMS | 343 | 358, 315, 275 |

| CBD-2TMS | 390 | 458, 301, 337 |

| CBC-1TMS | 303 | 371, 386, 246 |

| Δ8-THC-1TMS | 386 | 303, 265, 330 |

| Δ9-THC-1TMS | 371 | 386, 315, 303 |

| Δ9-THCd3-1TMS (IS2) | 374 | 389, 315, 73 |

| CBG-2TMS | 337 | 321, 460, 391 |

| CBN-1TMS | 367 | 310, 382, 295 |

| CBDA-3TMS | 491 | 453, 559, 492 |

| CBDA-1MET-2TMS | 433 | 434, 501, 73 |

| THCA-2TMS | 487 | 488, 550, 413 |

| THCA-1MET-1TMS | 429 | 430, 431, 73 |

| CBGA-3TMS | 561 | 562, 417, 453 |

| CBGA-1MET-3TMS | 503 | 417, 518, 73 |

| 5α-Cholestane (IS1) | 217 | 218, 372, 357 |

The chromatographic peak resolution was determined on a critical pair (CBC and Δ8-THC), according to the following expression:

where tR is the retention time of the chromatographic peak and w is the peak width at its base level. The sensitivity and repeatability precision (intraday and interday) of the method on both standard mixture and matrix were determined. The reproducibility and recoveries on hemp inflorescences were estimated.

The limit of detection and quantification (LOD and LOQ, respectively) were calculated by the signal-to-noise ratio (S/N); LOD was expressed as S/N of 3.3:1, whereas an S/N of 10:1 was used for LOQ. The intraday and interday precision of Fast GC–MS, expressed as relative standard deviation (RSD; %) was calculated by manually injecting of samples (n = 3) in the same day (intraday precision) for three consecutive days (interday precision, n = 9). The injections were performed by different operators for testing the method precision. The recoveries of cannabinoids were estimated at two spiking levels of phytocannabinoids standard mixture (25 ng/mL (A); 25.0 μg/mL (B)) in hemp inflorescence, using the following equation:

where Cfc is the cannabinoid amount found in the spiked sample, Cc is the cannabinoid amount present in the unspiked sample and Cf is the spiked amount of cannabinoid standards. Three independent replicates (n = 3) were run for spiked and non-spiked hemp.

The method robustness (RSD; %) was assessed by determining cannabinoids in hemp inflorescence (from their extraction to the Fast GC/MS analysis) in triplicates by two different operators.

2.7. Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis of data was performed by SPSS 21.0 (IBM-SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA). Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was carried out to investigate the effect of derivatization reagents, solvents and analytical conditions. Tukey’s honest significance test and T-test were carried out at a 99% confidence level to separate means of parameters. P-values under the significance level of 0.001 were considered statistically significant.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Derivatization study

As reported in literature [4], acid cannabinoids are converted into free cannabinoids (such as CBD, CBG and Δ9-THC) after exposure to high temperature. In fact, the decarboxylation is an important reaction for efficient production of the major active components in cannabis; however, it represents an important factor to be considered when the determination of cannabinoids is to be performed by GC. The high temperature of the injector and detector could lead to a significant components loss, thus it is important to prevent their decarboxylation when both acid and free cannabinoids determination is to be carried out by GC. To date, the main strategy is to silanize acid cannabinoids [13,16]. However, to our knowledge, no data about the methylation of cannabinoid carboxylic acids has been reported. Therefore, on the basis of published GC methods [16,21–23], the silylation reaction of cannabinoids was compared to methylation with diazomethane. In order to define the best conditions of silylation, different variables were evaluated. According to previous studies, both MSTFA and BSTFA with 1% of TMCS (MSTFA-TMCS and BSTFA-TMCS, respectively) were compared. In addition, since the presence of pyridine or ethyl acetate could increase the silylation yield [24–26], the effect of the solvent was also tested.

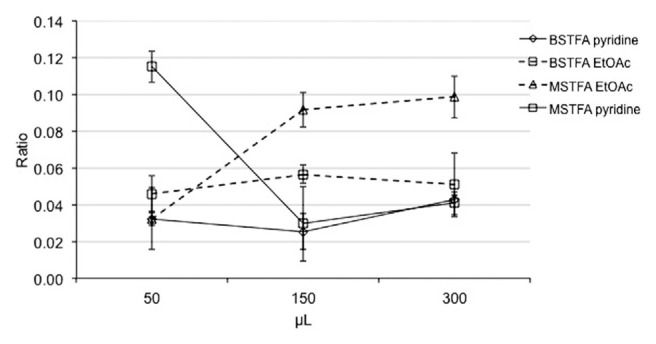

A fixed amount of Δ9-THCA standard (0.5 μg) and THCd3 standard (1 μg; internal standard, IS) reacted with 150 μL of MSTFA-TMCS or BSTFA-TMCS, in presence of an increasing amount (50, 150 or 300 μL) of pyridine or ethyl acetate at 60 °C for 30 min. The solvent was then evaporated and the sample was dissolved in 100 μL of n-hexane and injected (1 μL) in Fast GC/MS. The reaction efficiency was estimated by means of the AreaTHCA/AreaIS ratio. As reported in Fig. 1, the highest response was obtained with the lowest amount of pyridine, while the ethyl acetate led to highest reaction yields when 150 and 300 μL of solvent were used. However, the use of ethyl acetate gave a lower response than that achieved with 50 μL of pyridine. Moreover, when the reaction time was reduced to 15 min, the highest reaction yield was reached (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

Reaction efficiency (expressed as AreaTHCA/AreaIS ratio), as related to different derivatizing reagents, volume and type of solvent. Abbreviations: BSTFA pyridine, BSTFA-TMCS and pyridine; BSTFA EtOAc, BSTFA-TMCS and ethyl acetate; MSTFA EtOAc, MSTFA-TMCS and ethyl acetate; MSTFA pyridine, MSTFA-TMCS and pyridine.

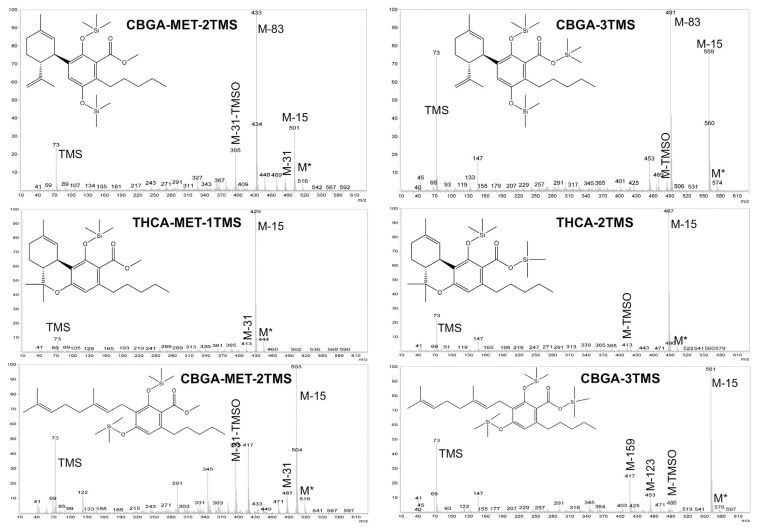

On the other hand, the carboxylic group of the cannabinoid acids could be also esterified by using diazomethane. Fig. 2 compares the mass spectra of CBDA, THCA and CBGA, respectively, obtained by silylation with MSTFA-TMCS at 60 °C for 15 min, as well as by methylation-silylation (MET-TMS). As expected, diverse mass spectra were obtained according to the different derivatization process used. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study that reports the mass spectra of methylated carboxylic cannabinoids. In general, for both methylated-silylated (MET-TMS) and silylated (TMS) cannabinoid acids, the molecular ion (M*) showed a low intensity. The M–15 fragment, which corresponds to a methyl group loss, was generally present in both MET-TMS and TMS cannabinoid acids, representing the base peak (100% of relative abundance) for THCA and CBGA (Fig. 2). In CBDA, instead, the M–83 fragment was its base peak, which corresponds to the loss of the side-chain (Fig. 2). In addition, the 73 m/z fragment (TMS group) was more noticeable in TMS cannabinoid acids than in MET-TMS cannabinoids, while M* tended to be higher in MET-TMS cannabinoids. In particular, the MET-TMS acid cannabinoids mass spectra were characterized by the presence of M–31 m/z (−OCH3) and M-31-TMSO. Furthermore, the TMS cannabinoid acid mass spectra were depicted by the presence of the M-TMSO fragment. In addition, as shown in Fig. 2, the M–15 fragment in CBDA-MET-2TMS was less intense than in CBDA-3TMS. Regarding CBGA, similar fragmentation was obtained with the two derivatization procedures, but with different relative intensity of the m/z fragments. As evidenced by these results, the derivatization reagent could thus affect the signal-to-noise ratio, impacting the method sensitivity.

Fig. 2.

Cannabidiolic acid (CBDA), tetrahydrocannabinolic acid (THCA) and cannabigerolic acid (CBGA) mass spectra, as related to methylation-silylation (MET-TMS) and silylation (TMS) derivatizations.

The response ratio (Areacannabinoid/AreaIS) of all 10 cannabinoid obtained by methylation-silylation vs. silylation with MSTFA-TMCS, was evaluated. Diazomethane generally increased the signal response, while esterification (MET-TMS) led to a significant response increase (p < 0.001) in CBD, Δ9-THC, CBG, CBN, CBDA, and THCA. This effect could be ascribed to the different reaction yield, as related to the steric hindrance of the derivatizing reagent functional group; probably the reaction of the carboxyl group with diazomethane is less affected by steric hindrance, thus leading to a complete esterification. When just silylation was considered (TMS), the contemporary presence of different TMSO groups could be disturbed by steric hindrance and the reaction could generate diverse interferences as reported by Van Look [27]. However, since diazomethane is not commercially available and requires 1-day synthesis by specialized chemical technician, trimethylsilyldiazomethane, a similar derivatizing reagent, was also tested. However, when trimethylsilyldiazomethane was used, the signal-to-noise ratio dramatically decreased and the number of unidentified peaks (to be ascribed to reagent interferences) increased, which confirms the better suitability of diazomethane as derivatizing reagent.

3.2. Optimization of the separation by Fast GC/MS method

On the basis of the abovementioned results and considering that diazomethane is not commercially available and its unsuitability for a routine method, the silylation with MSTFA-TMCS at 60 °C for 15 min was used for the whole method validation.

Literature reports that CBD, CBDA, CBGA and CBC are the main cannabinoids present in hemp inflorescences [4]; however, it is of outmost importance to carry out an accurate determination of the other minor cannabinoids, such as Δ9-THC, Δ9-THCA, CBN, THCV, CBG and Δ8-THC, which are generally present at levels that are about 100 times lower than CBD and CBDA. To overcome that problem, a double internal standard method was used, where 5α-cholestane was utilized to quantifyhigh-concentration cannabinoids (i.e. CBD and CBDA in hemp) and THCd3 for the rest of cannabinoids.

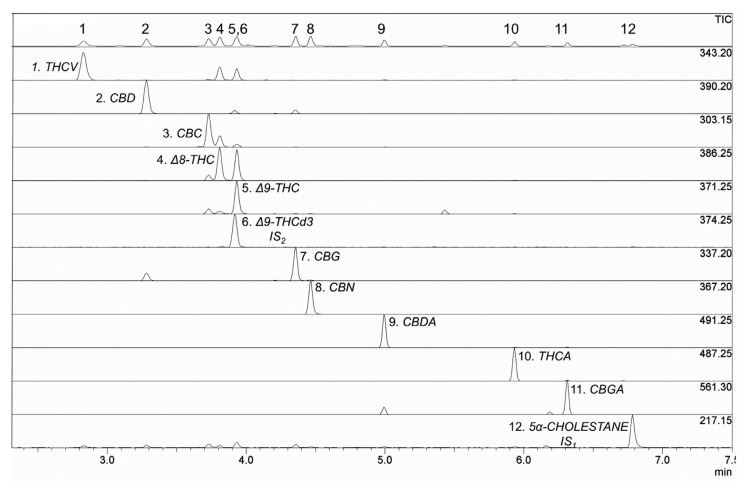

Using the analytical conditions reported in section 2.5, all compounds were well separated in less than 7 min within a time frame of 3 min (Fig. 3). Each cannabinoid was recognized by using its characteristic mass fragmentation pattern (mass spectra) produced by EI. One of the main advantages of fast separation is that all cannabinoids are fully resolved on the baseline (except for the full overlap of THC with THCd3); on the other hand, by using HPLC analysis, it is difficult to get a baseline resolution for three chromatographic pairs: Δ8-THC and Δ9-THC, CBDA and CBGA, and CBD and CBG [3].

Fig. 3.

Fast GC/MS trace of TMS derivatives of phytocannabinoids mixture.

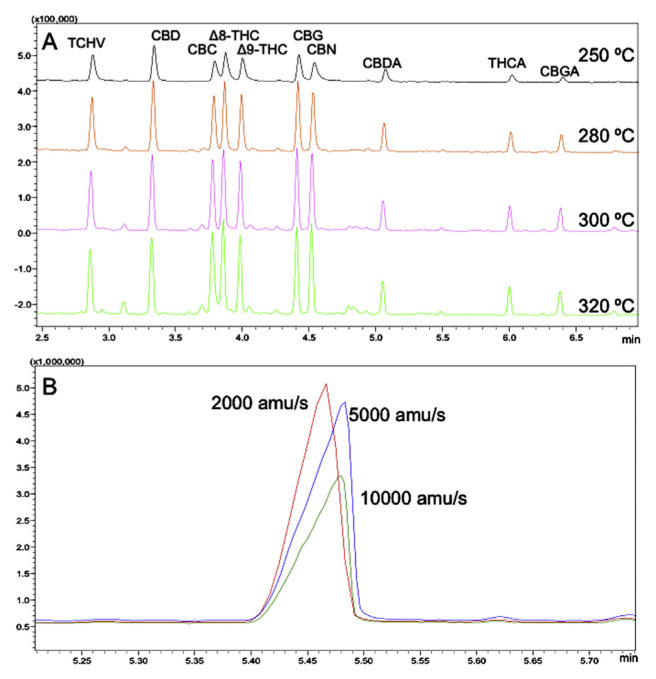

Different chromatographic and mass spectrometer conditions were tested, in order to obtain the final, optimized conditions. Several oven programs with different initial temperatures (180–250 °C), temperature increasing rates (3–25 °C/min) and linear velocities of carrier gas (0.45–1.50 mL/min), were examined; due to the thermo-sensitivity of cannabinoids, the effect of injector temperature was studied as well. As reported in Fig. 4A, when the injector temperatures was set up at 250 °C, the peak resolution decreased (R = 0.7), while higher temperatures improved peak resolution (R > 1.1) and signal intensity. However, the presence of unidentified peaks (i.e. matrix and/or reagent interferences) at higher temperature was observed. It should be noticed that the extraction method of cannabinoids was not selective, since high-boiling lipid molecules (such as tri-acylglycerols and sterols) were also present in the same extracted fraction. Thus, the risk of condensation phenomena of these high-boiling molecules in the injector is higher as the injector temperature decreases; for that reason, the injector temperature was set at 300 °C.

Fig. 4.

Fast GC/MS traces of TMS derivatives of phytocannabinoids obtained at different injector temperatures (A) and total ion current (TIC) mass spectrum of cannabidiolic acid (CBDA), as related to different quadrupole acquisition frequencies (B).

The acquisition frequency of the detector is a critical variable to be considered when a mass spectrometry analytical method is to be developed. As expected, the signal response was affected by the acquisition frequency; it is clear that, as the frequency increased from 2000 to 10 000 amu/s, the peak symmetry and signal significantly changed, thus impacting the instrumental sensitivity (Fig. 4B). Considering the results and the peak resolution, a frequency of 2000 amu/s was selected.

3.3. Method validation

The linearity of the Fast GC/MS method was evaluated by analyzing the standard solutions of phytocannabinoids using two different internal standards, 5α-cholestane and THCd3. Three independent replicates (n = 3) of each concentration level of the calibration curve were analyzed. For each individual cannabinoid, a calibration curve was generated as related to the different internal standard used. As shown in Table 2, these curves displayed a linear behavior within the concentration ranges tested, having determination coefficients (R2) that varied from 0.9907 to 0.9999 when THCd3 was used and from 0.9931 to 0.9996 when 5α-cholestane was tested. However, no significant differences (p > 0.001) were found on the linearity as related to different internal standards. The sensitivity was determined as reported by Cardenia et al. [18]. In general, the sensitivity was significantly affected by the internal standards used; indeed, when 5α-cholestane was tested, the LOD (2.19–9.40 μg/mL) was lower than those found using THCd3 (2.16–11.20 μg/mL), except for Δ9-THC and CBGA. As expected, the LOQ was also significantly affected by the different internal standards. The intraday and interday precision of the Fast GC/MS method was calculated by manually injecting (with different operators) the phytocannabinoids standard solutions (n = 3) in the same day (intraday precision) for three consecutive days (interday precision, n = 9) (Table 2). Again, the use of 5α-cholestane as internal standard significantly reduced the intraday and interday precision of the method. However, the results agree with literature data [10].

Table 2.

Analytical parameters of Fast GC/MS method, as related to different internal standards (THCd3 and 5α-cholestane).

| R2a | R2b | LOD (μg/mL)a | LOD (μg/mL)b | Sign. | LOQ (μg/mL)a | LOQ (μg/mL)b | Sign. | Intraday (RSD)a | Intraday (RSD)b | Sign. | Interday (RSD)a | Interday (RSD)b | Sign. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| THCV | 0.9992 | 0.9985 | ns | 7.32 | 3.97 | * | 22.20 | 12.00 | * | 7.63 | 3.16 | * | 10.13 | 11.10 | ns |

| CBD | 0.9981 | 0.9990 | ns | 4.29 | 2.19 | * | 13.00 | 6.63 | * | 8.38 | 2.09 | * | 9.15 | 7.76 | ns |

| CBC | 0.9999 | 0.9970 | ns | 4.62 | 2.94 | * | 14.00 | 8.91 | * | 6.06 | 3.44 | * | 6.16 | 5.08 | ns |

| Δ8-THC | 0.9994 | 0.9980 | ns | 5.72 | 2.91 | * | 17.30 | 8.82 | * | 3.49 | 3.27 | ns | 6.66 | 5.44 | ns |

| Δ9-THC | 0.9994 | 0.9981 | ns | 10.7 | 9.08 | ns | 32.40 | 18.40 | * | 0.80 | 2.37 | * | 5.59 | 5.39 | ns |

| CBG | 0.9978 | 0.9984 | ns | 2.16 | 4.07 | * | 6.55 | 12.30 | * | 1.83 | 3.36 | ns | 5.69 | 4.15 | ns |

| CBN | 0.9998 | 0.9970 | ns | 7.37 | 4.12 | * | 22.30 | 12.50 | * | 4.80 | 1.19 | * | 7.27 | 6.42 | ns |

| CBDA | 0.9951 | 0.9996 | ns | 5.31 | 7.66 | * | 16.10 | 23.20 | * | 3.63 | 2.77 | ns | 8.46 | 9.38 | ns |

| THCA | 0.9907 | 0.9948 | ns | 5.55 | 7.75 | * | 16.80 | 23.50 | * | 5.10 | 5.88 | ns | 9.50 | 10.53 | ns |

| CBGA | 0.9955 | 0.9931 | ns | 11.20 | 9.40 | ns | 34.00 | 25.50 | * | 7.53 | 2.77 | * | 8.50 | 7.25 | ns |

Sign., statistical significance; ns, not significant; the asterisks denote the level of significance at p ≤ 0.001.

THCd3 as internal standard.

5α-cholestane as internal standard.

The developed method allowed to reduce the analysis time, without losing sensitivity. The results obtained agree with available conventional GC methods [17], while the Fast GC/MS demonstrated to be more sensitive than HPLC methods [28], even though the use of MS/MS experiment could drastically improve the method sensitivity [12,29].

One sample of hemp inflorescence was used to assess the sensitivity, intraday and interday precision, recoveries and robustness of the method. As reported in Table 3, higher sensitivity was obtained using 5α-cholestane as internal standard, since both LOD (2.16 (CBC) – 58.86 (THCV) ng/mg inflorescence) and LOQ (7.18 (CBC) – 196.29 (THCV) ng/mg inflorescence) were relatively lower than those obtained using THCd3. However, the intraday repeatability was not affected by the different internal standards, whereas with 5α-cholestane the interday precision was lower for all cannabinoids, except for THCV, Δ8-THC, CBDA and THCA. Again, the sensitivity of the developed method was higher than that reported for HPLC analysis of cannabinoids in inflorescences [2]. Nevertheless, 5α-cholestane is a saturated C27 tetracyclic tri-terpene, having thus a chemical structure slightly different from those of cannabinoids. In fact, 5α-cholestane does not have hydroxyl or carboxyl groups to be derivatized, which could explain the different results obtained when compared with THCd3 as internal standard choice. Other chemicals have been also employed as internal standard for cannabinoid quantification, such as prazepam, ibuprofen, diazepam, di-n-octyl phatalate [9,17,27,29]; however, the use of deuterated cannabinoids represent a more powerful and expensive alternative.

Table 3.

Analytical parameters of Fast GC/MS method in hemp inflorescences, as related to different internal standards (THCd3 and 5α-cholestane).

| LOD (ng/mg)a | LOD (ng/mg)b | Sign. | LOQ (ng/mg)a | LOQ (ng/mg)b | Sign. | Intraday (RSD)a | Intraday (RSD)b | Sign. | Interday (RSD)a | Interday (RSD)b | Sign. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| THCV | 878.39 | 58.89 | * | 2927.98 | 196.29 | * | 9.43 | 8.05 | ns | 7.63 | 5.21 | ns |

| CBD | 193.66 | 3.74 | * | 645.55 | 12.45 | * | 8.86 | 8.42 | ns | 8.38 | 4.55 | * |

| CBC | 317.40 | 2.16 | * | 1058.00 | 7.18 | * | 6.80 | 5.55 | ns | 6.06 | 1.77 | * |

| Δ8-THC | 955.42 | 3.73 | * | 3184.75 | 12.42 | * | 9.80 | 6.49 | ns | 3.49 | 5.49 | ns |

| Δ9-THC | 1055.15 | 10.36 | * | 3517.16 | 34.53 | * | 7.57 | 6.98 | ns | 0.80 | 4.56 | * |

| CBG | 404.27 | 24.88 | * | 1347.57 | 82.93 | * | 4.64 | 6.90 | ns | 1.83 | 3.75 | * |

| CBN | 154.72 | 29.90 | * | 515.75 | 99.68 | * | 6.38 | 5.60 | ns | 4.80 | 1.88 | * |

| CBDA | 738.17 | 12.91 | * | 2460.56 | 43.05 | * | 6.11 | 5.61 | ns | 8.63 | 5.17 | ns |

| THCA | 559.23 | 7.36 | * | 1864.11 | 24.54 | * | 6.69 | 7.09 | ns | 5.10 | 3.57 | ns |

| CBGA | 950.91 | 13.58 | * | 3169.71 | 45.25 | * | 7.41 | 7.83 | ns | 8.53 | 4.94 | * |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Recovery (A)a | Recovery (A)b | Sign. | Recovery (B)a | Recovery (B)b | Sign. | Robustness (RSD)a | Robustness (RSD)b | Sign. | ||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| THCV | 88.80 | 96.67 | ns | 77.55 | 73.05 | ns | 7.11 | 8.00 | ns | |||

| CBD | 94.87 | 96.53 | ns | 74.63 | 72.03 | ns | 2.48 | 1.58 | ns | |||

| CBC | 80.27 | 90.00 | ns | 73.82 | 70.47 | ns | 5.46 | 7.32 | ns | |||

| Δ8-THC | 84.60 | 93.33 | ns | 75.42 | 71.30 | ns | 5.49 | 6.73 | ns | |||

| Δ9-THC | 81.60 | 91.28 | ns | 78.47 | 74.47 | ns | 6.69 | 8.00 | ns | |||

| CBG | 80.33 | 99.60 | ns | 74.45 | 71.23 | ns | 7.80 | 9.52 | ns | |||

| CBN | 96.60 | 89.33 | ns | 76.45 | 79.23 | ns | 7.08 | 7.77 | ns | |||

| CBDA | 102.00 | 100.04 | ns | 109.48 | 106.04 | ns | 7.53 | 8.54 | ns | |||

| THCA | 116.20 | 103.33 | ns | 105.65 | 100.40 | ns | 5.61 | 7.01 | ns | |||

| CBGA | 105.30 | 98.33 | ns | 103.35 | 101.47 | ns | 6.71 | 9.43 | ns | |||

Sign., statistical significance; ns, not significant; the asterisks denote the level of significance at p ≤ 0.001.

The results report the mean of three independent replicates (n=3).

THCd3 as internal standard.

5α-cholestane as internal standard.

The recoveries of cannabinoids in spiked industrial hemp inflorescence at two spiking levels (0.25 ng (A); 25.00 μg (B)), were evaluated. As reported in Table 3, the recoveries at both spiked levels were not significantly affected by the different internal standards, thus confirming their suitability for quantification of cannabinoids in hemp. When 0.25 ng were spiked into hemp inflorescences, the recoveries were 80.3–116.2% (with THCd3) and 89.3–103.3% (with 5α-cholestane); spiking with 25.00 μg led to 73.8–109.5% and 70.5–106.0% recoveries when THCd3 and 5α-cholestane were used, respectively. These results agree with those reported in literature; Escrivá obtained recoveries that ranged from 97.2% to 109.6% by using HPLC-DAD [17], which were marginally higher than those reported by Brighenti et al. [2] (74–91%). Citti et al. [9] found recoveries that varied from 89.2% to 99.6% in hemp seed oil when using HPLC/MS (quadrupole time of flight (QToF)) and MS/MS.

The determination of cannabinoids in hemp inflorescence (considering the whole procedure, from their extraction to Fast GC/MS analysis) performed in triplicates by two different operators, was used to assess the method robustness. No significant differences were found as related to different internal standards; the robustness was lower than 7.80% and 9.52% when THCd3 and 5α-cholestane were used as internal standards, respectively (Table 3). Therefore, the results confirm that the developed method can be used for routine determination of cannabinoids with a reduced analysis time and a less expensive internal standard (5α-cholestane) with respect to a deuterated one (THCd3).

3.4. Quantitative determination of cannabinoids in hemp inflorescences

The amount of cannabinoids can significantly change depending on pedo-climatic conditions, cultivation location, genetic variability and harvesting time [2]. In order to evaluate the method suitability for determining cannabinoids in hemp samples, three different batches of hemp inflorescences were supplied by a local company. Each batch was composed by three independent samples (n = 3), where each sample contained ten inflorescences of 10 different plants.

The use of double internal standards allowed to reduce data dispersion, thus increasing the accuracy for a wide concentration range, from more concentrated cannabinoids (such as CBDA and CBD) to less concentrated (such as CBN) or traces (such as THCV). In agreement with literature, CBDA (5.2 ± 0.58 g/100 g) was the most abundant compound, followed by CBD (1.56 ± 0.03 g/100 g), CBGA (0.83 ± 0.10 g/100 g) and CBC (0.54 ± 0.01 g/100 g). Considering that CBGA is the precursor of other cannabinoids, as well as the low presence of CBG, it can be hypothesized that all samples were stored in a conservative way, thus preventing them from degrading [30]. On the other hand, the similar amounts detected for Δ9-THC, Δ8-THC and CBN confirm the protective storage and treatment of hemp during the whole extraction and analytical procedure.

4. Conclusions

In conclusion, the Fast GC/MS method here proposed allows the quali-quantitative determination of the most common cannabinoids in short time (lower than 7.0 min), with a good resolution (R > 1.1). The method was set up and in-house validated, using a commercial standard mixture and tested on Cannabis sativa L. This Fast GC/MS method proved to be sensitive, with a high repeatability and robustness in both cannabinoids standard mixture and hemp inflorescence samples. The analytical performance, together with the consequent significant reduction in the analysis time and consumables, demonstrates that Fast GC/MS is a good alternative to other analytical and often expensive equipment, and evinces the great potential of such analytical technique, which could be also applied for the routine analysis of cannabinoids in hemp inflorescences. These results can contribute to the research on Cannabis sativa L. derivatives, which currently show a growing trend as raw material for drugs, food, fiber or building components. However, regardless of the final use of cannabis, a reliable and accurate identification and quantification of cannabinoids for the correct cannabis classification (fiber or drug type) still remains the crucial point from the legal standpoint.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Enecta B.V. (Amsterdam, NL) for having supported the research and also for supplying samples through the collaboration with Green Valley Società Agricola A R.L. (Castelvecchio Subequo, Italy).

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1. Feng L-Y, Battulga A, Han E, Chung H, Li J-H. New psychoactive substances of natural origin: a brief review. J Food Drug Anal. 2017;25:461–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jfda.2017.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Brighenti V, Pellati F, Steinbach M, Maran D, Benvenuti S. Development of a new extraction technique and HPLC method for the analysis of non-psychoactive cannabinoids in fibre-type Cannabis sativa L. (hemp) J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2017;143:228–36. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2017.05.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Citti C, Braghiroli D, Vandelli MA, Cannazza G. Pharmaceutical and biomedical analysis of cannabinoids: a critical review. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2018;147:565–79. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2017.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Leghissa A, Hildenbrand ZL, Schug KA. A review of methods for the chemical characterization of cannabis natural products. J Sep Sci. 2017;41:398–415. doi: 10.1002/jssc.201701003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. McPartland JM, Duncan M, Di Marzo V, Pertwee RG. Are cannabidiol and Δ 9-tetrahydrocannabivarin negative modulators of the endocannabinoid system? A systematic review. Br J Pharmacol. 2015;172:737–53. doi: 10.1111/bph.12944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Tzadok M, Uliel-Siboni S, Linder I, Kramer U, Epstein O, Menascu S, et al. CBD-enriched medical cannabis for intractable pediatric epilepsy. Seizure. 2016;35:41–4. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2016.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Izzo AA, Capasso R, Aviello G, Borrelli F, Romano B, Piscitelli F, et al. Inhibitory effect of cannabichromene, a major non-psychotropic cannabinoid extracted from Cannabis sativa, on inflammation-induced hypermotility in mice. Br J Pharmacol. 2012;166:1444–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2012.01879.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Carcieri C, Tomasello C, Simiele M, De Nicolò A, Avataneo V, Canzoneri L, et al. Cannabinoids concentration variability in cannabis olive oil galenic preparations. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2018;70:143–9. doi: 10.1111/jphp.12845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Citti C, Pacchetti B, Vandelli MA, Forni F, Cannazza G. Analysis of cannabinoids in commercial hemp seed oil and decarboxylation kinetics studies of cannabidiolic acid (CBDA) J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2018;149:532–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2017.11.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tsai Y-Y, Tai S-J, Huang M-C, Chang B-L, Liao C-H, Liu RH. Solid-phase extraction and gas chromatography-mass spectrometry analysis of 11-nor-9-carboxy-δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol in urine for monitoring marijuana abuse. J Food Drug Anal. 1999;7:177–84. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lin S-Y, Lee H-H, Lee J-F, Chen B-H. Urine specimen validity test for drug abuse testing in workplace and court settings. J Food Drug Anal. 2018;26:380–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jfda.2017.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Angeli I, Casati S, Ravelli A, Minoli M, Orioli M. A novel single-step GC–MS/MS method for cannabinoids and 11-OH-THC metabolite analysis in hair. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2018;155:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2018.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pacifici R, Marchei E, Salvatore F, Guandalini L, Busardò FP, Pichini S. Evaluation of cannabinoids concentration and stability in standardized preparations of cannabis tea and cannabis oil by ultra-high performance liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2017;55:1555–63. doi: 10.1515/cclm-2016-1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mudge EM, Murch SJ, Brown PN. Leaner and greener analysis of cannabinoids. Anal Chim Acta. 2017;409:3153–63. doi: 10.1007/s00216-017-0256-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Casiraghi A, Roda G, Casagni E, Cristina C, Musazzi U, Franzè S, et al. Extraction method and analysis of cannabinoids in cannabis olive oil preparations. Planta Med. 2018;84:242–9. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-123074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Purschke K, Heinl S, Lerch O, Erdmann F, Veit F. Development and validation of an automated liquid-liquid extraction GC/MS method for the determination of THC, 11-OH-THC, and free THC-carboxylic acid (THC-COOH) from blood serum. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2016;408:4379–88. doi: 10.1007/s00216-016-9537-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Escrivá Ú, Andres-Costa MJ, Andréu V, Picó Y. Analysis of cannabinoids by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry in milk, liver and hemp seed to ensure food safety. Food Chem. 2017;228:177–85. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2017.01.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cardenia V, Rodriguez-Estrada MT, Baldacci E, Savioli S, Lercker G. Analysis of cholesterol oxidation products by Fast gas chromatography/mass spectrometry. J Sep Sci. 2012;35:424–30. doi: 10.1002/jssc.201100660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Inchingolo R, Cardenia V, Rodriguez-Estrada MT. Analysis of phytosterols and phytostanols in enriched dairy products by fast gas chromatography with mass spectrometry. J Sep Sci. 2014;37:2911–9. doi: 10.1002/jssc.201400322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Amirav A. Fast heroin and cocaine analysis by GC–MS with Cold EI: the important role of flow programming. Chromatographia. 2017;80:295–300. doi: 10.1007/s10337-017-3249-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Emídio ES, de Menezes Prata V, Dórea HS. Validation of an analytical method for analysis of cannabinoids in hair by headspace solid-phase microextraction and gas chromatography-ion trap tandem mass spectrometry. Anal Chim Acta. 2010;670:63–71. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2010.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gasse A, Pfeiffer H, Köhler H, Schürenkamp J. Development and validation of a solid-phase extraction method using anion exchange sorbent for the analysis of cannabinoids in plasma and serum by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. Int J Leg Med. 2016;130:967–74. doi: 10.1007/s00414-016-1368-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Aldlgan AA, Torrance HJ. Bioanalytical methods for the determination of synthetic cannabinoids and metabolites in biological specimens. TrAC Trends Anal Chem (Reference Ed) 2016;80:444–57. doi: 10.1016/j.trac.2016.03.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lachenmeier DW, Kroener L, Musshoff F, Madea B. Determination of cannabinoids in hemp food products by use of headspace solid-phase microextraction and gas chromatography? mass spectrometry. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2004;378:183–9. doi: 10.1007/s00216-003-2268-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Nadal X, del Río C, Casano S, Palomares B, Ferreiro-Vera C, Navarrete C, et al. Tetrahydrocannabinolic acid is a potent PPARγ agonist with neuroprotective activity. Br J Pharmacol. 2017;174:4263–76. doi: 10.1111/bph.14019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Citti C, Battisti UM, Braghiroli D, Ciccarella G, Schmid M, Vandelli MA, et al. A metabolomic approach applied to a liquid chromatography coupled to high-resolution tandem mass spectrometry method (HPLC-ESI-HRMS/MS): towards the Comprehensive evaluation of the chemical Composition of cannabis medicinal extracts. Phytochem Anal. 2018;29:144–55. doi: 10.1002/pca.2722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Van Look G, editor. Silylating Agents Derivatization Reagents Protecting-Group Reagents Organosilicon Compounds Analytical Applications Synthetic Applications. Buchs, Switzerland: Fluka Chemie Ag; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Patel B, Wene D, Fan Z (Tina) Qualitative and quantitative measurement of cannabinoids in cannabis using modified HPLC/DAD method. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2017;146:15–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2017.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Jamwal R, Topletz AR, Ramratnam B, Akhlaghi F. Ultra-high performance liquid chromatography tandem mass-spectrometry for simple and simultaneous quantification of cannabinoids. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2017;1048:10–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2017.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hanuš LO, Meyer SM, Muñoz E, Taglialatela-Scafati O, Appendino G. Phytocannabinoids: a unified critical inventory. Nat Prod Rep. 2016;33:1357–92. doi: 10.1039/C6NP00074F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]