Abstract

Globally, 296 million people are infected with hepatitis B virus (HBV), and approximately one million people die annually from HBV-related causes, including liver cancer. Although there is a preventative vaccine and antiviral therapies suppressing HBV replication, there is no cure. Intensive efforts are under way to develop curative HBV therapies. Currently, only a few biomarkers are available for monitoring or predicting HBV disease progression and treatment response. As new therapies become available, new biomarkers to monitor viral and host responses are urgently needed. In October 2020, the International Coalition to Eliminate Hepatitis B Virus (ICE-HBV) held a virtual and interactive workshop on HBV biomarkers endorsed by the International HBV Meeting. Various stakeholders from academia, clinical practice and the pharmaceutical industry, with complementary expertise, presented and participated in panel discussions. The clinical utility of both classic and emerging viral and immunological serum biomarkers with respect to the course of infection, disease progression, and response to current and emerging treatments was appraised. The latest advances were discussed, and knowledge gaps in understanding and interpretation of HBV biomarkers were identified. This Roadmap summarizes the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and challenges of HBV biomarkers.

Subject terms: Prognostic markers, Diagnostic markers

Currently, there is no cure for hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection, which can lead to chronic liver disease and liver cancer, and only a few biomarkers are available. This Roadmap provides an overview of HBV serum biomarkers and their challenges.

Key points

As new therapies for hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection become available, new biomarkers to monitor viral and host responses are urgently needed.

This Roadmap summarizes current knowledge on existing and emerging serum biomarkers in the context of chronic HBV infection.

This Roadmap discusses the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and challenges of serum HBV biomarkers.

This Roadmap provides suggestions of the way forward to advance the biomarkers required to fast-track an HBV cure for all, irrespective of resources, HBV genotype or disease stage.

Introduction

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection can cause chronic hepatitis B (CHB), which can result in severe liver disease, including cirrhosis and liver cancer. A major challenge to recovery, even in treated individuals, is the persistence of two forms of the viral genome in hepatocytes: the replication-competent, episomal, covalently closed circular DNA (cccDNA), and the linear subgenomic HBV sequences integrated into the human genome, which do not sustain viral replication but can express some HBV antigens1. High viral loads and antigens can lead to T and/or B cell exhaustion and downregulation of innate immune sensors and pathways2–7. Current antiviral therapies, which include nucleos(t)ide analogues (NUCs) and pegylated interferon-α (peg-IFNα), decrease viral loads and lead to remission of the disease. However, although NUCs are well tolerated, they require lifelong treatment and do not target cccDNA directly8. Conversely, peg-IFNα, the only finite treatment for CHB, is less well tolerated but might affect cccDNA directly and indirectly9. Treatment results in hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) loss (also known as functional cure) in a minority of cases10,11. Consequently, new effective, finite and well-tolerated cure therapies are being sought to induce functional cure, fully controlling HBV replication and gene expression and/or ultimately eliminating cccDNA and integrated HBV DNA (also known as sterilizing cure)10,11.

CHB is a major global health challenge, and there is an urgent need to develop curative therapies for patients with CHB worldwide12. In 2020, mortality from human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, malaria and tuberculosis continued to decline, but death attributable to viral hepatitis is still increasing13, with rates predicted to double by 2040, even though effective cures for hepatitis C virus are already available. The World Health Organization (WHO) set a goal for the elimination of viral hepatitis with a 90% reduction of new HBV cases by 2030; it is unlikely to be achieved without a substantial increase in the rate of HBV diagnosis. It is estimated that less than 10% of individuals with HBV infection have been identified, and only 10% of the eligible patients receive treatment globally12. To achieve the goal set by WHO, a panel of serum biomarkers will likely be required for surveillance to predict treatment response and outcome as an armamentarium of new therapies is developed. Although a limited number of biomarkers is available that permits monitoring of HBV DNA replication and treatment response to current treatment regimens, biomarkers accurately predicting functional cure are lacking. With more than 40 new therapeutic approaches in preclinical or clinical trials14,15 targeting HBV replication or stimulating HBV-specific host immune responses, identifying suitable biomarkers will become increasingly important.

In October 2020, the International Coalition to Eliminate Hepatitis B Virus (ICE-HBV) held a virtual and interactive workshop on HBV biomarkers, at which stakeholders from academia, clinical practice and the pharmaceutical industry, with complementary expertise, presented and participated in panel discussions. The clinical utility of both classic and emerging, viral and immunological serum biomarkers with respect to the course of infection, disease progression, and response to current and emerging treatments was appraised. The latest advances were discussed and knowledge gaps in our understanding and interpretation of HBV biomarkers were identified.

This Roadmap summarizes current knowledge for existing and emerging HBV virological and immune-related biomarkers and suggests a road forward to advance the biomarkers required to fast-track an HBV cure for all, irrespective of resources, HBV genotype or disease stage.

HBV biomarkers

HBV cccDNA, the key molecule in the HBV life cycle, is first generated from incoming virions and exists as a stable minichromosome in non-dividing hepatocytes1,16. cccDNA is the template for transcription of all HBV RNAs17, including the pre-genomic RNA (pgRNA) replication intermediate that is reverse transcribed into new HBV genomes. Thus, cccDNA is responsible for the production of virions and subviral particles. A detailed description of the viral life cycle has been previously presented18. Integrated HBV sequences can encode HBsAg and seem to be a major source of HBsAg in patients who are negative for hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg)19. In addition, integrated sequences can produce truncated HBV RNAs and hepatitis B virus x (HBx) protein.

Serum biomarkers currently used in clinical practice to discriminate CHB and disease stages20 include quantitative HBsAg, HBeAg, HBV DNA (Fig. 1) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) serum levels. However, these biomarkers are not universally available, particularly in resource-limited settings (discussed later), and the classification and use of these classic markers do not completely reflect CHB complexity or HBV intrahepatic activity16. Intrahepatic measurement of cccDNA and viral RNAs might improve disease classification but entail using liver biopsy samples, which are invasive, not routine CHB care and unavailable in resource-limited settings. Furthermore, only a small section of the liver is sampled by liver biopsies, and HBV is unevenly distributed in the liver21,22. Although specific quantitative polymerase chain reactions (PCRs) for cccDNA have been developed23,24, the coexistence of HBV replicative DNA intermediates in infected cells16, including relaxed circular and integrated HBV DNA molecules, interferes with accurate cccDNA quantification. In this respect, a global collaborative project initiated by ICE-HBV aims to optimize and harmonize cccDNA detection and quantification protocols in liver tissue and cell culture.

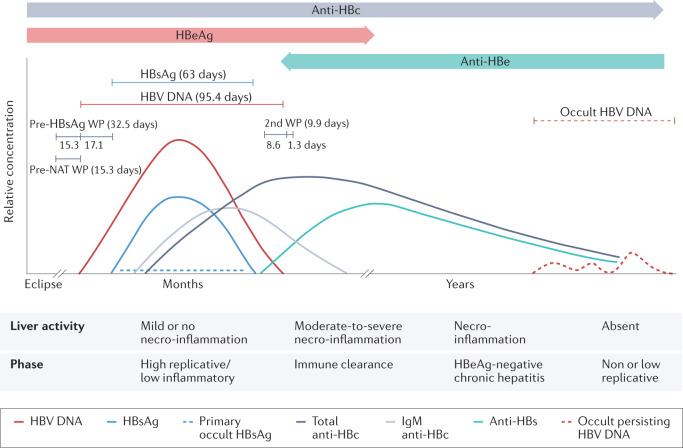

Fig. 1. Course of serum markers in acute resolving hepatitis B virus infection.

The curves in the upper part of the diagram show the relative concentration of the markers in a typical infection. The lines above the curves show the mean lengths of the detection periods of hepatitis B virus (HBV) DNA and hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) as estimated from the numbers of HBV nucleic acid testing (NAT) yields, with and without detectable HBsAg. The lengths of the pre-HBsAg and post-HBsAg window periods (WPs) and pre-NAT and post-NAT WPs as described by Weusten et al.176. In a later stage of occult HBV infection, when titres of antibodies against hepatitis B surface antigen (anti-HBs) have declined to below 10–100 mIU/mL, occult persisting HBV DNA in the liver can reappear in plasma. If infection occurs perinatally or in very early childhood, there is no full recovery because of immune system immaturity, and this can lead to chronic infection in 90% of cases. The duration of HBsAg positivity is thus prolonged. The lower panel of the figure depicts the stages of natural infection according to current European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) guidelines (hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg)-positive or HBeAg-negative disease and/or infection)177. Anti-HBc, hepatitis B c antibody; Anti-HBe, hepatitis B e antibody; HBeAg, hepatitis B e antigen. Adapted with permission from ref.178, Wiley.

Accordingly, there is a pressing need for alternative biomarkers that not only accurately reflect the intrahepatic cccDNA pool and transcriptional activity25,26 but also better characterize the different CHB disease stages and risk of complications, detect HBV integration, improve the determination of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) risk, and monitor immune status and response to therapy. For example, one study showed that HBV functional cure in 10 of 14 patients with genotype A HBV infection was associated with anti-HBsAg immune complex peaks that overlapped with ALT flares in serum levels27. This suggests the utility of hepatitis B surface antibody (anti-HBs, also known as HBsAb) immune complexes as a biomarker of functional cure and warrants further investigation in larger studies encompassing additional HBV genotypes.

Ideal biomarkers should be predictive (visible early and indicative of clinical outcome), highly specific and sensitive, HBV (sub)genotype agnostic, correlative with disease activity and severity, reflective of durable viral control, reproducible, non-invasive and accessible, rapid, simple, and inexpensive28. Biomarkers should also be accessible in resource-limited settings.

Various serum HBV markers have been proposed as surrogates for intrahepatic viral activity. These markers include the complete virion (HBV DNA, hepatitis B core antigen (HBcAg), HBsAg), subviral particles (with HBsAg), empty virus particles (with HBsAg and HBcAg but without HBV DNA or RNA), viral particles containing HBV RNA, and HBV core-related antigen (HBcrAg) consisting of the non-particulate HBeAg and the related precore protein that, like HBeAg, is also derived from the precore/core open reading frame29. We have appraised the clinical utility of both classic (HBV DNA, HBeAg and/or hepatitis B e antibody (anti-HBe), HBsAg, anti-HBs and hepatitis B core antibody (anti-HBc)) and emerging (HBV RNA, HBcrAg and HBsAg isoforms) biomarkers of HBV infection with respect to the course of infection, disease progression, and response to current and emerging treatments.

Classic biomarkers: needs and limitations

A summary of classic biomarkers is presented in Supplementary Table 1. More sensitive DNA assays might be beneficial in identifying residual and fluctuating HBV levels30,31, predicting the risk of reactivation or severe outcomes following NUC treatment withdrawal32, assessing the effect of direct antiviral agents on DNA suppression, and accurately detecting occult HBV infection (OBI)33. In light of WHO recommendations that, in settings where antenatal HBV DNA testing is not available, HBeAg testing can be used to determine eligibility for tenofovir therapy to reduce the likelihood of mother-to-child HBV transmission34, there is a need for point-of-care (POC) HBeAg assays, particularly in resource-limited settings. A limitation of all HBsAg assays is that they do not differentiate between HBsAg derived from cccDNA and integrated HBV DNA because the protein derived from either source is identical35. More research is required to determine the usefulness of quantitative anti-HBs, anti-HBe and anti-HBc assays to better characterize the risk of HCC and reactivation of HBV infection following treatment discontinuation or immunosuppression. These markers are proving useful in detecting OBI (discussed later).

Point-of-care testing: an unmet need

WHO has developed a simplified HBV treatment cascade based on the biomarkers of HBsAg, ALT, presence of cirrhosis and HBV DNA levels36. Treatment eligibility requires appropriate screening and assessment for active disease. These tools include rapid diagnostic tests and ELISA for HBsAg, HBV DNA nucleic acid testing (NAT), ALT (liver panel), and fibrosis measurements such as transient elastography or aspartate aminotransferase-to-platelet ratio index (APRI) score. In addition, regular HCC surveillance with abdominal ultrasonography alongside, or not, serum analysis of α-fetoprotein (AFP) serum levels is essential.

Unfortunately, many of these tests are not readily available as required POC tests, particularly in resource-limited settings37. Their availability will be necessary to meet the ASSURED criteria38 (Affordable, Sensitive, Specific, User-friendly, Rapid and robust, Equipment-free, and Deliverable to those that need them).

Rapid HBsAg screening tests, such as Determine HBsAg 2 (Alere Medical, Chiba-ken, Japan) and VIKIA HBsAg (bioMérieux SA, Marcy-l’Étoile, France), are available for POC screening. POC HBV DNA NAT platforms have been validated or are in development. In addition, fibrosis measurement by transient elastography (FibroScan) can be adopted for POC with a portable FibroScan; however, the availability of transient elastography is sparse in resource-limited settings39.

Rapid diagnostic tests for HBsAg for multiple HBV genotypes and subtypes40, with results available in 30 min, have been developed41. Notably, the sensitivity of HBsAg enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and rapid diagnostic tests varies for different HBV genotypes41. Genetic variability in the S gene region of HBV can also affect diagnostic efficacy and specificity42,43. HBsAg ELISA tests that include multiple monoclonal antibodies in the capture phase, together with a polyclonal conjugate phase, are more accurate. HBsAg rapid diagnostic tests are generally less sensitive than lab-based ELISA tests. In our opinion, rapid diagnostic tests, such as Determine and VIKIA, are adequate for HBV screening but are not ideal for monitoring treatment response.

Dried blood spot (DBS) tests have numerous advantages compared to obtaining a standard blood sample; namely, the capillary finger-stick does not require trained health workers, high blood volumes, basic lab facilities, electric power, or a cold chain for transport and storage44. In 2017, WHO conditionally recommended the use of DBS specimens as an option for HBV DNA NAT in settings where there were no facilities or expertise to take venous blood specimens and for persons with poor venous access36. Meta-analysis of 12 studies from Europe (France, Denmark, Germany and Spain), Africa (Ethiopia, Congo, Egypt and Zambia), India and Mexico comparing the sensitivity and specificity of DBS versus serum samples for HBV DNA showed that DBS sensitivity ranged from 93% to 100% and specificity from 70% to 100%44. The limit of detection of the HBV DNA assays for serum samples ranged from 10 IU/ml to 100 IU/ml. HBV DNA detection limits from DBS specimens ranged from approximately 900 IU/ml to 4,000 IU/ml (ref.44). Potential issues identified were the various lengths of storage before testing, ambient temperature variations, and the absence of manufacturer validation for the use of their assays with DBS samples or standardization of technical guidance. Many manufacturers and investigators have validated NAT using DBS by standardized procedures.

DBS have also been used in the HBcrAg assay, showing that HBcrAg correlated strongly with HBV DNA levels for genotypes A–E in individuals with high viral load, suggesting that DBS might be useful in resource-limited settings with limited access to NAT45. However, the assay used to measure HBcrAg, LUMIPULSE chemiluminescent enzyme immunoassay (Fujirebio, Tokyo, Japan), is currently not widely available.

Several POC or near POC NAT platforms have been developed for other blood-borne viruses, including the Xpert HCV Viral Load FS assay (Cepheid, USA), Genefrive (Manchester, UK) and the Alere (Abbott, USA). The GeneExpert platform (Cepheid, USA) is widely available across resource-limited settings where it is used routinely for tuberculosis diagnostics and HIV viral load monitoring. It is also being used to detect severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). Importantly, a GenExpert viral load assay has also been developed for HBV, which should be readily available in many resource-limited settings where GeneExpert machines have been placed to monitor other pathogens46,47. Fibrosis measurement by transient elastography can be adopted for POC with a portable FibroScan. FibroScan is the preferred method for cirrhosis and fibrosis assessment, with improved performance compared to APRI/FIB4 (ref.48). Improving the availability of the portable FibroScan in resource-limited settings should be prioritized. It is important to note that hepatic inflammation and non-fasting states can falsely increase fibrosis scores with FibroScan, so the results need to be interpreted with care.

To establish a POC model for HBV management in resource-limited settings, standardized diagnostic assays with rapid diagnostic tests or DBS using currently available HBV DNA and HBsAg biomarkers are urgently required. Together with practical and effective guidelines for disease monitoring and therapy, this will assist in reaching the WHO goals of HBV elimination, particularly in resource-limited settings, where the HBV burden is highest.

Novel or emerging biomarkers

HBV RNA

HBV cccDNA is the template for five viral transcripts: precore/core RNA, pgRNA, preS1 RNA, preS2/S RNA and X RNA17,49,50. pgRNA and precore RNA are over-length molecules of approximately 3.5-kb in size, and hence can only be transcribed from cccDNA51–55. Additional molecules transcribed from cccDNA include 5′ truncated RNAs with 3′ poly(A) tails56,57 and HBx RNA55,58. Subgenomic RNAs encoding HBx or HBsAg can also be transcribed from integrated HBV DNA, which could be 5′ truncated with poly(A) tails. At least 15 splice variants of pgRNA54–56 and two splice variants of preS2/S mRNA17, which arise from co-transcriptional processing, have been isolated from the supernatant of transfected cell lines or primary human hepatocytes54 and patient sera54,59–61. The majority of splice variants identified to date encode the 5′ region of pgRNA and their contribution to pgRNA levels detected in RNA PCR assays requires investigation.

Viral RNA does not circulate freely52 but is found in virus-like particles in serum (or supernatant of cultured cells)51,56,62. HBV RNA can also be found in capsid-antibody complexes62 and naked capsids51,62. The secreted HBV RNA-containing viral particles have a similar buoyant density to HBV DNA-containing particles. However, they are produced at lower levels and, when reverse transcription is blocked, levels increase relative to HBV DNA-containing particles53. The quasispecies of serum and intrahepatic HBV RNA are similar and homologous to cccDNA56.

Various strategies for measuring HBV RNA are shown in Table 1. Few comparisons of the different assays have been performed so far and no widely accepted (international) RNA standard is currently available63.

Table 1.

Methods for quantification of HBV RNA in serum

| Method | Details | Reverse transcription primer | Primer sites | LLOQ and LLOD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RT-qPCR | RNA isolation (including DNase treatment) and subsequent PCR method with specific primers either detecting pre-genomic or all HBV RNAs52,76,165,166 | HBV specific | Precore, X, C or S region |

2.55 log10 copies/mL (LLOQ)10; 1.85 log10 copies/mL (LLOD)63 2.6 log10 copies/mL (LLOD)75 |

| Droplet digital PCR | Droplet digital PCR53,167,168 | HBV specific | all regions | 100 copies/mL = 2 log10 copies/mL (LLOD)79 |

| 3′ Rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RACE)-based | Oligo (dT) primer plus a unique artificial anchored sequence to generate cDNA63,64,169 | Oligo(dT) primer | Poly(A) tail | 2.6–3.4 log10 copies/mL (LLOD)80,81 |

| QuantGene assays | Hybridization-based and via branched DNA signal amplification technology–measurement via luminometer54 | NA | X region | NA |

| Indirect |

HBV (DNA + RNA) minus DNA determined by real-time PCR170,171 Serum HBV pgRNA minus HBV pcRNA determined by real-time PCR172 |

HBV specific | Precore and C region | 2.2–2.3 log10 copies/mL (LLOD)170–172 |

| Commercial RNA assays (currently research use only) | ||||

| Abbotta | Serum HBV RNA, real-time PCR74 | NA | NA | 10 copies/mL (LLOD, V2) |

| Rocheb173 | Serum HBV RNA, real-time PCR | NA | NA | 10 copies/mL (LLOQ); 10–109 copies/mL (linear range) |

C, core (capsid); HBV, hepatitis B virus; LLOD, lower limit of detection; LLOQ, lower limit of quantification; NA, not applicable; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; pcRNA, precore RNA; pgRNA, pregenomic RNA; RT-qPCR, reverse transcription-quantitative PCR. aIU/ml applies to the Abbott assay; however, there is no international standard for HBV RNA and the IU reported by the Abbott assay is currently based on the WHO HBV DNA standard. bFor ‘Research Use Only’ and not FDA approved at this stage.

Clinical relevance of HBV RNA

The ratios of the different forms of HBV RNA and their importance during the different clinical phases or treatment responses are unknown. However, we consider that HBV RNA shows promise as a biomarker of treatment responses that are not predicted by serum HBV DNA levels using current NUC therapy in some settings. HBV RNA kinetics are predictors of response to treatment in patients who are HBeAg positive64. Even though HBV DNA levels decrease following NUC treatment, HBV pgRNA levels can remain relatively high, decreasing at a later stage63. This decoupling of pgRNA to HBV DNA levels can enable pgRNA to be used as a surrogate marker for cccDNA activity or cccDNA copies in the cell under NUC therapy63.

In the absence of therapeutic intervention, the level of HBV RNA in serum generally correlates closely with HBV DNA, albeit 1.5–2 logs lower65,66. The prognostic usefulness of HBV RNA in following the natural history of infection is uncertain and it has become clear, through the preparation of this Roadmap, that there is a paucity of data on its ability to predict liver-related complications, including cirrhosis or HCC. Serum HBV RNA and intrahepatic HBV RNA (primarily full-length encapsidated pgRNA51,67) levels were lower in patients with inactive HBV than in patients with CHB who were either HBeAg positive or HBeAg negative65,68. In patients with CHB, HBV RNA levels varied according to HBeAg status (being higher in patients who were HBeAg positive), with liver inflammation, HBV genotype, and basal core promoter and/or precore mutants24,53,66,69. In the HBeAg-positive phase, serum HBV RNA levels showed a better correlation to serum HBV DNA levels than to either HBsAg or HBeAg66. This correlation seemed to be genotype dependent, with HBV RNA showing a strong correlation with HBV DNA levels for genotype A and with HBsAg levels for genotypes B and C; these associations were weakest for genotype D66. The correlation of HBV RNA with HBV DNA held during the HBeAg-negative phase, with genotype-specific correlations of HBV RNA levels only determined for genotypes A and D66. The weak correlation between HBV RNA levels and HBsAg in the HBeAg-negative phase is most likely due to the large proportion of HBsAg being expressed from integrated HBV DNA.

The decline of both full-length and subgenomic HBV RNA at 3 and 6 months after the initiation of NUC treatment was the strongest predictor of HBeAg seroconversion compared to other markers, including serum levels of HBV DNA, HBsAg, HBeAg, HBcrAg and ALT as well as sex, age and HBV genotype64,70. Together with HBcrAg, serum HBV RNA levels are also a prognostic biomarker for predicting ALT flares and the likelihood of HBV reactivation following cessation of NUC therapy in the absence of detectable HBV DNA32,71. In patients who were HBeAg positive, HBV RNA correlated strongly with HBcrAg levels but this was not observed in patients who were HBeAg negative32,71. Increased HBV RNA levels can also be a marker for viral relapse after NUC discontinuation72,73.

As serum pgRNA is derived exclusively from HBV cccDNA, its measurement can reflect cccDNA activity1. It might also serve as a surrogate marker to assess the target engagement of drugs affecting serum RNA levels by affecting RNA transcription, pgRNA stability and pgRNA packaging (that is, pegylated interferons, small interfering RNAs, antisense oligonucleotides, core protein assembly modulators (also known as capsid assembly modulators (CAMs)). Indeed, the CAM NVR 3–778 plus peg-IFNα but not the NUC entecavir lowered the concentration levels of HBV RNA in serum without causing substantial changes in cccDNA loads71,74,75. Peg-IFNα treatment reduced HBV RNA levels in the liver and serum of humanized mice, with good correlations between serum and intrahepatic pgRNA levels but not with cccDNA levels, as such pgRNA reduction mostly reflected the suppression of cccDNA activity76. In patients who are HBeAg positive, low HBV RNA levels can also help predict response, HBeAg loss and sustained virological control off-treatment after peg-IFNα and combined peg-IFNα–NUC therapy52,77. Although the relevance and correlation between viral RNA serum levels and liver damage still need clarification, serum HBV RNA could help define treatment end points51,78.

HBV RNA can be an addition to HBV DNA as a biomarker in some settings, particularly in predicting which patients will benefit most from treatment cessation. However, because the contributions of serum HBV RNA derived from cccDNA, integrated HBV DNA, or splice variants were unresolved and different quantitative methods were used79, the clinical and biological importance of serum HBV RNA levels should be interpreted with caution. There are also currently no HBV RNA standards available to validate and compare assays in different laboratories. The current Abbott HBV RNA assay has utilized WHO-approved DNA standards32,63 and, until appropriate HBV RNA standards are developed and calibrated, WHO DNA standards will continue to be used where applicable. HBV RNA was undetectable by currently available assays in more than 50% of patients who were HBeAg negative and on long-term NUC therapy and could even be undetectable in patients with low HBV DNA levels (as in HBeAg-negative infection)32 who had not received treatment, suggesting the sensitivity of detection needs improvement, especially with regards to possible cross-reaction with HBV DNA. However, HBV RNA could be detected in patients who were HBV DNA negative and was shown to be an accurate predictor for patients who might relapse following NUC treatment cessation32, demonstrating the promise of this biomarker in clinical settings.

Hepatitis B core-related antigen

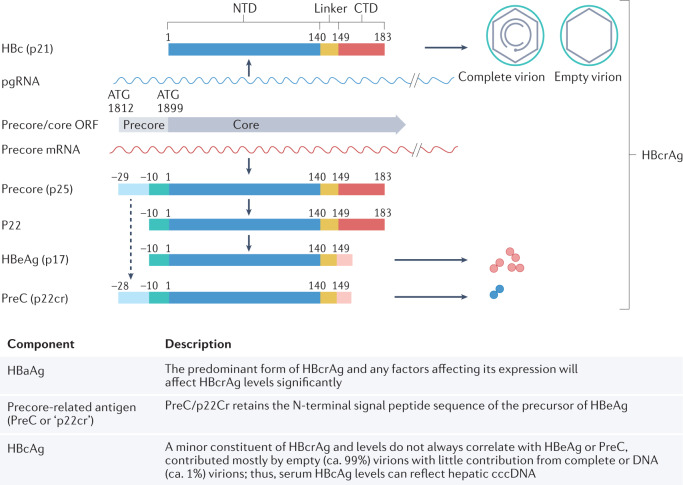

HBcrAg, a composite antigen found in the blood of patients with HBV infection, has emerged as a potential marker to monitor intrahepatic cccDNA and its transcriptional activity, thereby defining new meaningful treatment end points80–82. HBcrAg components and their biogenesis are illustrated in Fig. 2. Each HBcrAg component can have distinct functions and applications in reflecting intrahepatic viral activities29,83, varying between genotypes and individual patients29.

Fig. 2. Schematic representation of HBcrAg biogenesis29.

Hepatitis B core antigen (HBcAg), translated from pre-genomic RNA (pgRNA), forms the icosahedral capsid inside complete and empty virions179. The direct translation product from the precore mRNA is the precore precursor protein (p25), from which hepatitis B virus e antigen (HBeAg) and precore (PreC; also known as p22cr) are both derived. Removal of the N-terminal signal peptide of p25, by the signal peptidase during p25 translocation into the endoplasmic reticulum lumen, leads to the production of p22 (ref.180), which is further processed at its C-terminal domain (CTD) before being secreted as the dimeric HBeAg (p17)181,182. cccDNA, covalently closed circular DNA; HBc, hepatitis B c; HBcrAg, hepatitis B virus core-related antigen; NTD, N-terminal domain; ORF, open reading frame. Adapted with permission from ref.29, American Society for Microbiology.

Clinical relevance of HBcrAg

HBcrAg can distinguish the different clinical phases of CHB83,84, although this ability is limited by the presence of basal core promoter and/or precore mutants that influence HBeAg levels. Serum HBcrAg levels were higher in the HBeAg-positive phase than in the HBeAg-negative phase82,85,86, and correlation with intrahepatic cccDNA levels and transcriptional activity was stronger during HBeAg-positive CHB82. HBcrAg also showed potential for distinguishing between HBeAg-negative inactive and active disease82,85,87–91. Using principal component analysis, researchers could discriminate between patients who were HBeAg positive or HBeAg negative. When HBcrAg was considered, a third group of patients was identified characterized by higher cccDNA, transcriptional activity, high fibrosis and necro-inflammatory activity that could not be discriminated by serum HBV DNA and HBeAg alone32,82,92. Multiple studies show that HBcrAg correlated well with pgRNA in HBeAg-negative CHB. An improved assay for HBcrAg assay with 10-fold increased sensitivity compared to previous assays has been developed93.

HBV DNA and pgRNA levels in the liver were higher in patients who were HBcrAg positive than in those who were HBcrAg negative, suggesting active HBV replication in HBcrAg-positive livers94. HBcrAg was a non-inferior biomarker to HBV DNA in predicting cirrhosis in patients who were HBeAg negative95, with elevated HBcrAg levels in patients with CHB who were treatment naive and HBeAg negative, correlating with increased risk of progression to cirrhosis96. Thus, although an elevated HBV DNA level is still the main indicator for initiation of NUC treatment, HBcrAg might also have a role in identifying patients of high risk with an intermediate HBV viral load who could benefit from early NUC treatment to prevent progression to cirrhosis96. HBcrAg levels can also predict the risk of HCC82,94, which is important as NUC therapy does not eliminate this risk97. In a large study of 2,666 patients with CHB who were infected with genotypes B or C, HBcrAg was an independent risk factor for HCC (209 patients were positive for HCC)98. Whether this observation applies to patients with different HBV genotypes requires investigation. Despite sustained viral suppression, persistently high levels of on-treatment HBcrAg and detectable levels after antiviral therapy termination might predict long-term HCC risk in patients with CHB treated with NUC94,97,99. Detection of residual HBcrAg, in combination with secreted HBV RNA but not HBV DNA, also predicted severe relapse following NUC treatment withdrawal in three of four patients32 and might be a useful biomarker to contraindicate NUC re-treatment and predict relapse100 following treatment cessation.

HBcrAg is also associated with response to current antiviral therapy for HBeAg-positive CHB101 and, together with secreted HBV RNA, should be considered when evaluating new antiviral therapies aiming at a functional cure by direct or indirect targeting of the intrahepatic cccDNA activity102. Although used in Japan, further studies are needed to inform whether HBcrAg can be used in clinical practice more broadly.

HBcrAg assay

The current commercial HBcrAg assay, the chemiluminescent enzyme immunoassay (CLEIA; Lumipulse G HBcrAg, Fujirebio), is for research use only. It detects a combination of HBcAg, HBeAg (both free and in the HBeAg–HBe antibody complex) and precore proteins in the blood following sodium dodecyl sulfate and heat treatment103–105 and has been validated for DBS45. The relative contribution of each component of HBcrAg in this assay has not been elucidated and affects the accuracy and utility of HBcrAg as a biomarker for cccDNA. Both viral and host factors can affect the expression of the different components of HBcrAg. Mutations that affect HBeAg (and precore) expression can influence HBcrAg levels, and this reduction obviously cannot be correlated to a reduction of cccDNA activity or copy number. This is also true for increased clearance of HBeAg (and precore) from the serum via a peripheral mechanism such as antibody-mediated clearance29,106.

HBsAg isoforms

The HBsAg components, large and medium surface proteins, differ during the various phases of CHB107 and have different dynamics under treatment107,108. Except for genotype G, which has impaired HBsAg release, no difference in glycosylation, subcellular distribution, release of HBsAg or formation of subviral particles was evident between genotypes when compared in vitro109. However, there were differences in the proportions of HBsAg isoforms both intracellularly and extracellularly between different genotypes, with different post-translational modification patterns for large surface proteins109. Large and medium surface proteins were shown in patients to decrease earlier than small surface proteins prior to HBsAg loss, suggesting that these proteins might represent promising novel biomarker candidates to predict functional cure108. However, more basic research is required to understand the biology of HBsAg isoforms and their clinical relevance, particularly as surrogate markers for HBsAg expression from cccDNA versus integrated HBV DNA and to ascertain if they provide additional diagnostic benefits for the staging of CHB or in monitoring response to current treatment modalities; they might prove to be valuable in monitoring future therapeutic approaches.

HBV biomarkers during treatment

Receiver operating characteristic curves showed that absolute HBV RNA levels were consistently superior to the change from baseline for predicting peg-IFNα response in patients77. No single biomarker seemed superior when comparing HBV RNA, HBV DNA, HBeAg and HBsAg. However, HBV RNA and HBsAg were more accurate at predicting non-responders than HBeAg and HBV DNA77. Furthermore, patients with CHB who were HBeAg negative and treated with peg-IFNα showed rapid HBV RNA decline that correlated with treatment response and long-term HBsAg loss110. This finding likely reflects the ability of peg-IFNα to act as an immune modulator and to lower HBV transcript levels. Similarly, HBcrAg was associated with treatment response for NUC, with and without peg-IFNα, in patients with CHB who were HBeAg positive and in those with CHB who were HBeAg negative101,111. However, HΒcrAg was not superior to HBsAg in predicting therapy response.

The different mechanisms of action of HBV drugs might affect the performance of HBV serum biomarkers, and this needs to be considered, particularly as new therapies targeting different aspects of the HBV life cycle are developed. For example, the reduction in RNA levels was consistently higher in patients treated with CAMs in combination with NUCs than in those treated with NUCs alone112. The reduction of serum HBV RNA during treatment with CAMs is consistent with their mechanism, which blocks pgRNA packaging into capsids as required for their secretion into blood113. In this case, serum RNA will no longer correlate with cccDNA levels or transcriptional activity but can serve to monitor target engagement.

Immunological serum biomarkers

In CHB, HBV persists with dynamic variations in hepatocellular injury with inflammation versus disease and/or virus control and the participation of multiple immune effectors and regulatory pathways2–7. Given the lack of safe and convenient access to the liver compartment, examining the serum immune markers is needed to gain mechanistic, clinical and prognostic insights.

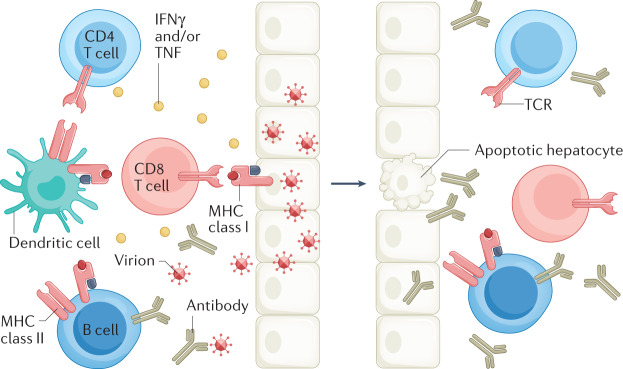

As HBV is non-cytopathic, HBV-associated liver disease is largely immune mediated, with the host immune response being induced upon viral recognition (Fig. 3). HBV persistence is associated with global and virus-specific adaptive immune dysregulation or tolerance. In persistent HBV infection without a robust adaptive immune response, multiple inflammatory mechanisms can be activated to mediate hepatocellular injury114. The immune exhaustion, tolerance and pathogenic mechanisms with associated markers and cell subsets, summarized in Box 1, also provide potential avenues for therapeutic immune restoration115.

Fig. 3. Adaptive immune responses against HBV.

Control of hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection requires both cellular (CD4+ and CD8+ T cells) and humoral (antibody production by B cells) arms. Using both cytolytic and cytokine-mediated non-cytolytic mechanisms and major histocompatibility (MHC) class I and class II antigen recognition, CD8+ T cells have a primary effector role to kill and cure HBV-infected hepatocytes7,114. CD4+ T cells have a key regulatory role144,183. Neutralizing antibodies to hepatitis B surface antigen (anti-HBsAg) bind circulating virus, thereby reducing viral spread and providing protective immunity184. A key role for B cells in protective immunity to HBV has also been suggested by the high rate of HBV reactivation in patients undergoing B cell depletion with anti-CD20 (ref.185). IFNγ, interferon-γ.

A challenge and opportunity is the measurement of biomarkers in serum that can reflect immunological activity in the liver. In theory, this could be achieved using cytokines, chemokines, and immune regulatory and metabolic factors that can be followed in relation to the clinical course of CHB and response to antiviral therapy (Box 2). Currently, none of these markers seems to be superior to other clinical and virological measures, and further investigations are required to evaluate the potential clinical role of these markers. However, they might collectively provide insights to host responses during novel HBV therapies with potential mechanistic and prognostic implications. In this regard, as a first option, serum biomarkers (for example, cytokines, chemokines, metabolic markers, soluble PD1, soluble CD14) might be more readily examined in clinical studies as only a small amount of blood is needed to measure hundreds of markers simultaneously in highly multiplexed assays116. A second option is the examination of cellular immune phenotype and function in peripheral blood. This approach can vary in complexity yet can be feasible at scale once optimized, and can range from a simple cytokine stimulation assay to assess HBV-specific T cells similar to what has been done for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)117–119 or the diagnostic test for tuberculosis that uses an IFNγ release assay120, to a more complex phenotypic and functional analysis. Considering global and virus-specific immune dysfunction in CHB, a therapeutic goal is to achieve sustained virus control with immune restoration by suppressing viral antigen expression and the viral life cycle. Accordingly, there is a strong rationale to examine how the immune phenotype and function are affected by novel therapies, including immune-modulatory therapies such as Toll-like receptors agonists, therapeutic vaccines, checkpoint inhibitors and those targeting the viral life cycle with potential immune effect121. As a third option, despite growing challenges, direct sampling of the intrahepatic compartment (for example, through liver biopsy) is needed to visualize viral and immune markers simultaneously122,123, and such analyses can currently be done more comprehensively by using various emerging highly multiplexed and computational approaches124–126 to better understand the spatial landscape of HBV and host responses in the liver.

Box 1 Mechanisms contributing to immune dysregulation or tolerance and leading to pathogenesis in CHB.

Mechanisms of T cell dysfunction

Antigen-specific exhaustion with the induction of checkpoint molecules such as PD1 and CTLA4 (refs.114,186) in addition to epigenetic changes.

T cell deletion through the pro-apoptotic protein Bcl2-interacting mediator (Bim)187 or activated NK cells188.

Induction of regulatory T cells, cytokines and chemokines189–191.

Myeloid-derived suppressor cells that secrete soluble arginase192 that can deplete arginine from T cells.

Mitochondrial alterations with further metabolic deficit193.

Mechanisms of B cell dysfunction or tolerance

Increased PD1 expression can lead to global and HBV-specific impairment of B cell differentiation and function194.

Excess HBsAg contributes to B cell exhaustion with HBeAg mediating antigen-specific immune tolerance195.

Regulatory and pathogenic mechanisms

Inflammatory cytokines and/or chemokines (for example, from dendritic cells and Kupffer cells) can increase hepatic inflammatory infiltrates, induce inflammatory NK cells and promote hepatocellular susceptibility to apoptosis.

Apoptosis can be induced through TRAILR2 (ref.196), contributing to hepatocellular injury, with fluctuations in levels of ALT, HBV DNA, HBsAg and/or HBeAg, ultimately leading to liver disease progression.

NK cells can also kill HBV-specific T cells through NKG2D-dependent and TRAIL-dependent lysis188.

Damaged hepatocytes and myeloid-derived suppressor cells release soluble arginase, which depletes arginine and leads to suppression of T cell proliferation114,191,192,197,198.

Platelets can also promote accumulation of inflammatory cells in the liver, contributing to pathogenesis199.

Liver sinusoidal endothelial cells can prime CD4+ and CD8+ T cells with diverse effects, they can also produce IL-10 and express PDL1 with potential regulatory effect with activated immune cells expressing PD1 (refs.200,201).

Altered phenotype and/or function of γδ T cells202 and mucosal-associated invariant T cells203 have been described in CHB, in association with clinical and/or therapeutic virus suppression.

Additional hepatic cells that participate in HBV immune pathogenesis include liver sinusoidal endothelial cells, myeloid-associated T cells and platelets, resulting in fibrogenesis.

ALT, alanine aminotransferase; CHB, chronic hepatitis B; HBeAg, hepatitis B e antigen; HBsAg, hepatitis B surface antigen; HBV, hepatitis B virus; NK, natural killer.

Box 2 Immunological serum markers to follow the natural history of HBV infection and outcome of antiviral therapy.

Immunological markers to follow the natural history of HBV infection

IFNα, IL-8 and NK expression of TRAIL

Pathogenetic markers correlated with viral loads and flares of liver inflammation (ALT)196:

IFNα increased TRAIL expression in peripheral NK cells, which could induce apoptosis of hepatocytes expressing TRAIL-receptor.

Induction of TRAIL-receptor expression in HBV-infected liver, whereas is IL-8 shown to increase TRAIL-receptor expression in vitro.

Chemokines CXCL9–11 and IDO

Markers associated with hepatocellular injury, immune recruitment and potential antiviral activity204:

CXCL9–11 levels correlated with ALT and IDO activity.

CXCL10 positively correlated with increased levels of ALT and T cell expression of PD1 (refs.205,206) as well as hepatic inflammatory score but negatively with serum HBV DNA and HBsAg207.

IDO is inducible in epithelial and plasmacytoid dendritic cells by IFNγ and/or TNF and has both regulatory and antiviral activities.

Metabolic markers (arginase and L-arginine)

Arginine depletion in the inflamed liver due to increased arginase as a potential mechanism for the global defect in CD8 T cell signalling and function in CHB:

L-Arginine is needed for T cell metabolism and survival.

Increased serum arginase activity and reduced serum L-arginine levels were associated with increased ALT activity and flares in patients with AHB and CHB197,198.

Increased arginase suppressed antiviral T cell function.

sPD1 and sPDL1

Soluble markers with a potential regulatory role in the PD1–PDL1 pathway192,198:

Binding of sPD1 to membrane-bound PDL1 on target tissues can block the regulatory interactions with PD1 expressed on activated immune cells or, alternatively, binding of sPDL1 to PD1-expressing immune cells can inhibit their interactions with membrane-bound PDL1 expressed by target tissues208.

Serum sPD1 levels were associated with persistently higher HBV load and higher HCC risk209.

Serum sPD1 levels were greater in CHB than in controls and positively correlated with levels of ALT, AST, total bilirubin, HBV DNA, AST to platelet ratio index ((AST/upper limit of the normal AST range) X 100/platelet count), fibrosis score Fib4, hepatic inflammatory score and fibrosis but negatively correlated with platelet count210.

As a caveat, there are assay-related issues that need to be resolved before clinical application, with additional head-to-head comparisons of the different immune assays needed to resolve discrepant sPD1 and sPDL1 levels observed in different studies211.

Immunological serum markers to follow the outcome of antiviral therapy

CXCL10

Greater serum levels at baseline and at the time of HBV DNA suppression in patients who achieved over 0.5 log decline in HBsAg on NUC therapy than those who did not212.

Decline in serum levels on antiviral therapy correlated with virological response to telbivudine treatment205.

Pre-treatment serum CXCL10 (also known as IP-10) levels were substantially greater in patients with CHB who achieved HBeAg clearance or HBsAg decline with peg-IFNα therapy207. Similarly, higher pre-treatment CXCL10 levels correlated with an increased probability of HBeAg loss after peg-IFNα therapy, with declines in HBV DNA, HBeAg and HBsAg being steeper in individuals with CXCL10 levels >150 pg/ml. However, this correlation only held for HBV infection without basal core promoter and/or precore mutants213.

Multivariate logistic regression analysis showed serum CXCL10 level to be an independent predictor of HBeAg clearance and HBsAg decline207.

Cytokines and chemokines

Substantial increases in CXCL13 and IL-21 levels were detected in patients with CHB who attained HBsAg seroconversion but not in patients with CHB with persistent HBsAg, including those with flares214.

Substantial increases in CD163, TNF, IL-12p70, IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-18, IL-10, IL-2, IFNλ2, IFNα, FAS ligand, CXCL9, CXCL10, CXCL13 and CCL4 in patients with liver damage after stopping therapy215.

CXCL9, CXCL10, CXCL11, CXCL13 and IL-21 levels were elevated at the peak of AHB; IL-21 elevation was observed only in patients with self-limiting infection but not among those with chronic evolution.

Despite the small sample size, CXCL13 and IL-21 might be markers of functional cure for both AHB and CHB214.

sPD1

Lower baseline sPD1 levels were associated with HBeAg clearance after 2 years of antiviral treatment in patients with HBeAg positive CHB216.

sCD14

sCD14, a co-receptor for lipopolysaccharides, is a biomarker in infectious and inflammatory diseases that is produced by liver monocytes, macrophages and human hepatocytes.

sCD14 levels were substantially higher in AHB than in patients with CHB or healthy individuals as controls in one study217.

sCD14 level increased substantially at 12 weeks post-treatment compared to baseline in patients with CHB receiving peg-IFNα, with the fold change being substantially higher in responders than in non-responders.

sCD14 levels correlated with markers of hepatic inflammation and fibrosis in patients infected with HCV or HBV218.

AHB, acute hepatitis B; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; CHB, chronic hepatitis B; HBeAg, hepatitis B e antigen; HBsAg, hepatitis B surface antigen; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; HCV, hepatitis C virus; IDO, indoleamine 2,3 oxygenase; IFNα, interferon-α; IFNγ, interferon-γ; NK, natural killer; NUC, nucleos(t)ide analogue; Peg-IFNα, pegylated IFNα; sCD14, secreted CD14; sPD1, soluble PD1; sPDL1, soluble PDL1.

Biomarkers of occult HBV infection

OBI is defined as the presence of cccDNA in the liver and/or HBV DNA in the blood of people who tested negative for HBsAg by currently available assays33,127. Statements on the biology and clinical effect of OBI suggested that the ideal diagnosis method for OBI is the detection of replication-competent HBV DNA in the liver33. The recommended methods included nested-PCR techniques to amplify at least three different viral genomic regions, real-time PCR assays or droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) assays. In each case, the assay must include primer sets enabling the detection of replication-competent HBV DNA33.

The diagnosis of OBI depends on the sensitivity of assays used to detect HBV DNA in liver tissue and/or blood samples and HBsAg in serum samples. Sensitivity for HBV DNA detection is improving with new technologies such as ddPCR assays. In a study of 100 transplant liver donors who were anti-HBc positive, OBI was diagnosed using four parallel nested PCRs to detect HBV surface, core, polymerase and X sequences128. Next, ddPCR was used to quantify cccDNA, which was detected in 52% (52 of 100) of the individuals who were OBI positive, with a median of 13 copies per 105 cells (95% CI 5–25)128. More sensitive HBsAg assays have also been developed. Commonly used assays detect HBsAg at 0.05 IU/ml; however, the newly developed assays can detect HBsAg with a sensitivity of 0.005 IU/ml (ref.129). These more sensitive assays can improve the detection rate of low-level HBsAg, HBsAg variants, and HBsAg with anti-HBs130,131 and can provide improved detection of OBI132.

In addition to HBsAg assays, inadequately sensitive HBV DNA assays can lead to false-negative HBV DNA results and a missed OBI diagnosis30. Commercially available real-time PCR-based assays for serum HBV DNA detection are sufficiently sensitive to detect many (but not all) OBI cases. ddPCR assays might increase the rate of OBI detection and need to be evaluated systematically in the OBI setting. In addition, consideration should be given to the need to diagnose OBI by re-screening samples by ddPCR, which is only accessible via research facilities but not routinely available in diagnostic laboratories31,133.

Lessons can be learned from HBV reactivation studies in patients with chronic hepatitis C treated with direct-acting antiviral agents. Nested-PCR testing of longitudinally collected serum samples from 40 patients revealed that serum HBV DNA was intermittently detected in 25% (10 of 40) at baseline and 52.5% (21 of 40) at 3 months after termination of direct-acting antiviral treatment. Moreover, HBsAg and HBcrAg biomarkers were negative at baseline and remained persistently negative (without any fluctuation) in all the serially collected serum samples134. Thus, as HBV DNA is usually present in low concentrations and can only be intermittently detected in people with OBI, testing blood samples collected at more than one timepoint and testing DNA extracts from at least 1 ml of serum or plasma is recommended for OBI diagnosis33,127. Indeed, it should be considered that OBI is characterized by periods of transient HBV viraemia alternating with periods in which the viral DNA is undetectable in blood135–138. Moreover, evidence demonstrated an association between the reappearance of circulating HBV DNA and phases of ALT serum level increases, suggesting a role in the transient reactivation of HBV replication in liver cell injury136,137. Furthermore, Candotti et al. described nine cases of undetected HBV transfusion-transmission from OBI-positive blood donation despite the use of highly sensitive HBsAg and HBV DNA screening assays30. Importantly, the availability of archive samples from both donors and recipients and large-volume (2–24 ml) follow-up donor samples enabled the researchers to detect HBV transfusion-transmitted infection associated with extremely low HBV DNA loads. These results led the researchers to conclude that, until more sensitive assays become available, long-term archiving of large-volume pretransfusion plasma samples from both donors and recipients is essential to identify transfusion-transmission of undetected OBI to limit delays in the therapeutic management of patients with HBV infection30.

As molecular tests are not always available, there is a strong consensus that detection of anti-HBc in the blood can be used as a surrogate biomarker for OBI in blood and/or organ donors and in people initiating immunosuppressive therapies33,139. Although serum levels of anti-HBc correlate with cccDNA positivity128, the absence of anti-HBc does not rule out OBI33. High baseline levels of anti-HBc (and low or absent anti-HBs) were shown to predict HBV reactivation in 36 of 192 patients with lymphoma and resolved HBV infection receiving B cell-depleting chemotherapies (hazard ratio of 17.29 for HBV reactivation (95% CI 3.92–76.30; P <0.001))140,141. Anti-HBc quantification and analysis of circulating HBV-specific T cells in patients who are HBsAg negative might be interesting biomarkers but require further confirmation in the setting of OBI. Currently, HBV DNA is the only reliable diagnostic marker of OBI and a standardized diagnostic procedure for OBI remains an important unmet clinical need.

Biomarkers of liver cancer

Chronic HBV infection causes liver cancer, the sixth most common cancer and the third leading cause of cancer-related death worldwide. HCC is more common in men (2–4 times higher incidence than in women) and the prognosis is poor in all regions of the world, with incidence and mortality rates being roughly equivalent. The median survival of patients with early HCC is >5 years but is <1 year when detected at an advanced stage. Due to a lack of appropriate biomarkers, most HCC cases are detected at late stages and not when the tumour is still localized and treatment options are more effective142.

Currently, HCC surveillance relies on a limited armoury of serum biomarkers and/or imaging of the affected liver. Cancer biomarkers are detected in the blood, urine or other body fluids and can indicate the presence of cancer or predict the risk of cancer development143. Ideally, biomarkers should enable early detection of cancer by screening healthy or high-risk populations, confirming the diagnosis or identifying a specific type of cancer, predicting prognosis, monitoring treatment response, and detecting early recurrence142.

The identification of biomarkers for the early detection of cancer requires the following steps131:

Phase 1: Preclinical exploratory studies: to identify promising biomarker candidates.

Phase 2: Clinical assay and validation: to detect the disease versus controls (for example, distinguish HCC from non-HCC).

Phase 3: Retrospective longitudinal repository studies: to detect preclinical disease by retrospective analysis.

Phase 4: Prospective screening studies: to determine the detection rate of the assay (sensitivity and specificity).

Phase 5: Cancer control studies: to assess the effect of screening on reducing the disease burden in the target population.

Over the past several decades, AFP has been the most extensively studied and most commonly used HCC biomarker. It has been utilized for the assessment risk of HCC in patients with cirrhosis, as a screening tool for the early detection of HCC, and as a diagnostic and prognostic tool for HCC144. In addition to AFP, a number of novel biomarkers for HCC diagnosis and monitoring are in different phases of development. Serum biomarkers currently in phase 2 (clinical assay and validation) include osteopontin, midikine, dikkopf 1, glypican 3, α1 fucosidase, Golgi protein 73 and squamous cell carcinoma antigen145–147. Serum biomarkers at more advanced stages of development include AFP (phase 5), Lens culinaris agglutinin fraction of AFP (AFP-L3) (phase 2/3) and des-γ-carboxy prothrombin (DCP) (phase 2/3)142. Genetic and cellular biomarkers (so-called liquid biopsy) under investigation include circulating tumour cells, circulating tumour DNA, microRNA and long non-coding RNA148.

AFP is the best characterized and most widely used serum biomarker for HCC surveillance. However, its effectiveness is limited as not all HCCs secrete AFP149. In addition, AFP serum levels can be elevated in patients with chronic hepatitis or cirrhosis. However, with the advent of highly effective NUCs for the treatment of CHB, elevated on-treatment AFP levels were shown in a large retrospective-prospective study to be a specific marker for HCC because falsely elevated AFP levels in 1,531 patients receiving entecavir were minimized compared to 424 patients that received no treatment, suggesting that, in this group of patients, a lower AFP cut off value could be used150. Elevated on-treatment AFP is a specific tumour marker for HCC in patients with CHB receiving entecavir150. There is little debate that AFP should not be used alone in HCC surveillance, but it has been debated whether AFP should be included in HCC surveillance due to its suboptimal sensitivity (39–65%) and specificity (76–97%)151. However, most studies show a benefit of combining AFP with ultrasonography152. Various factors can influence the performance of AFP as an HCC biomarker, including patient demographics, aetiology of underlying liver disease, severity of liver disease (cirrhosis, chronic hepatitis, serum ALT values), antiviral therapy, and tumour stage and biology153. In turn, according to the size of the tumour, the sensitivity of ultrasonography imaging for detecting HCC at an early stage is highly variable, ranging from 21% to 89% across studies included in a meta-analysis published in 2018 (ref.152). It is largely operator dependent, based on the skill of the sonographer and influenced by patient characteristics, including obesity, liver nodularity and presence of ascites154–156. A meta-analysis of 32 studies comprising 13,367 patients collected worldwide showed that ultrasonography alone detected early-stage HCC with a sensitivity of 45% compared to 63% when ultrasonography was combined with AFP (P = 0.002)152. The improved sensitivity was associated with a decrease in specificity (84% versus 92%). However, the addition of AFP to ultrasonography significantly increased the sensitivity of early HCC detection, suggesting this might be the preferred surveillance strategy for patients with cirrhosis152. Other factors to consider are the value of single timepoint versus longitudinal analysis and tailoring cut-offs according to liver disease aetiology, severity and antiviral therapy. The diagnostic value of AFP for detecting HCC was also improved when used in combination with the level of serum protein induced by vitamin K absence or antagonist II (PIVKAII) in patients of European descent157 and Asian158 (South Korea) patients with cirrhosis.

Longitudinal determinations also improve AFP performance as an HCC biomarker159. A phase III biomarker study evaluating AFP, AFP-L3, DCP and their combinations for the early detection of HCC in prospectively collected longitudinal samples from 689 patients with cirrhosis or CHB160 showed that a combination of AFP and AFP-L3 at diagnosis differentiated early-stage HCC from cirrhosis better than each biomarker individually. Investigating the sensitivity and specificity of ultrasonography alone or in combination with biomarkers showed that adding AFP to ultrasonography increased the sensitivity to 88.6%, and adding AFP plus AFP-L3 to ultrasonography increased the sensitivity to 94.3%160.

In summary, although the addition of AFP to ultrasonography imaging markedly improved the early detection of HCC, results are still suboptimal and new biomarkers to predict early-onset HCC are required. Longitudinal determination of AFP increases the sensitivity and specificity for HCC surveillance but optimal cut-offs for AFP and other biomarkers of HCC surveillance in patients with suppressed HBV and minimal hepatic inflammation are unclear. Given the high degree of heterogeneity of HCC, the combination of AFP with other biomarkers and clinical parameters improves the sensitivity and specificity of surveillance for early HCC detection.

The road forward

To map a way forward, the clinical utility of both classic and emerging viral and immunological biomarkers of HBV infection, with respect to the course of infection, disease progression, and response to current and emerging treatments, was appraised in two-panel discussions. The panels discussed the latest advances, knowledge gaps, and key challenges and opportunities for improvement were identified by addressing three key questions: do we have the appropriate biomarkers to measure HBV cccDNA, and are the emerging biomarkers relevant for measuring the mechanism of action of new drugs? What are the key biomarkers that require further research to have the strongest clinical effect? Finally, how urgent is the need for predictive immunological biomarkers for inflammation or antiviral response? The strengths and weakness of current biomarkers for addressing each of these questions are presented in Table 2, with a Roadmap outlining the actions required to address unmet clinical needs presented in Table 3.

Table 2.

Strengths, weaknesses and challenges of current and emerging HBV serum biomarkers

| Biomarker | Strength | Weakness | Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Circulating HBV DNA | Gold standard measure of HBV replication | Only an indirect measure of HBV activity in the liver; does not measure the frequency of HBV-infected cells in the liver; does not accurately reflect HBV cccDNA activity | Measuring the proportion of HBV-infected cells in the liver; improved sensitivity so that ‘undetectable’ serum HBV DNA means there is no virus in circulation: if the current PCR assay detects 10 copies/ml (10,000 copies/L), an increase in sensitivity of 50,000-fold would be needed to identify 1 circulating HBV DNA molecule; POC viral load assays are required for resource-limited settings |

| HBsAg | Best marker for monitoring functional cure (HBsAg loss); levels predict likelihood of HBsAg loss or progression to liver cancer in some clinical settings | Unsuitable as a marker of immune restoration; cannot distinguish between HBsAg derived from integrated HBV DNA or cccDNA; studies on the association with likelihood of progression to liver cancer are restricted to HBV genotypes B and C; different genotypes or subgenotypes might express different levels of HBsAg | Improved sensitivity to monitor HBsAg loss, although the clinical relevance of increased sensitivity is unclear; quantitative POC assays are required for resource-limited settings |

| HBeAg | A surrogate for HBV DNA levels in the absence of viral load testing; HBeAg loss, typically with seroconversion to anti-HBe is a current treatment end point for antiviral therapy | Ineffective in HBeAg-negative CHB | Qualitative POC assays are required for resource-limited settings as a surrogate for HBV viral load in patients who are HBeAg positive; although HBeAg loss might be less relevant in future as a treatment end point for functionally curative antivirals, it will likely still be relevant for treatment regimens that do not eliminate HBsAg expression from integrated sequences but might nonetheless induce HBeAg loss and a low HBV replication state |

| HBV RNA | Indirect measure of cccDNA transcription; some association with likelihood of treatment response | Most assays cannot distinguish HBsAg or HBx RNA derived from cccDNA or integrated HBV DNAa; contribution of non-replicative RNAs (for example, spliced RNA) to the secreted RNA pool is unknown | Clinical relevance is still unclear; assays are required to distinguish between integrated and cccDNA-derived RNA and to determine the contribution of splice variants to the RNA pool |

| HBcrAg | Accurately distinguishes between HBeAg-negative infection and active CHB, independent of HBV genotype91,174; cohort data show that HBcrAg could stratify HCC and/or cirrhosis risk in patients who are HBeAg negative in the indeterminate zone for antiviral treatment95 | Confounded by the presence of HBeAg in patients who are HBeAg positive; highly specialized assay with limited availability | Clinical relevance is still unclear in high viral load settings; less relevant in patients who are HBeAg positive, in whom much of the HBcrAg is HBeAg |

Anti-HBe, antibody against hepatitis B e antigen; cccDNA, covalently closed circular DNA; CHB, chronic hepatitis B; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; HBcrAg, hepatitis B core-related antigen; HBeAg, hepatitis B e antigen; HBsAg, hepatitis B surface antigen; HBV, hepatitis B virus; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; POC, point of care. aAbbott test has two targets enabling the discrimination of pgRNA only from all other RNA. There is no evidence of other RNA present in plasma, at least not in sufficient quantities to be detected by a sensitive PCR test. This might imply that RNA fragments derived from integrated HBV DNA fragments do not reach the plasma.

Table 3.

The road forward

| Need | Rationale | Action |

|---|---|---|

| Increased sensitivity of biomarker assays | Measurement of HBV replication below the current limit of detection, particularly in patients who are treated; improved sensitivity will enable prediction of off-treatment remission and cure (sustained response), particularly as serum does not always reflect liver pathology | Diagnostic companies should be encouraged to develop highly sensitive HBV DNA assays; improved sensitivity will also assist in the detection of OBI |

| Extrapolation of assays to different patient cohorts | The clinical value of current and emerging biomarkers needs to be assessed in different patient cohorts, including their ability to define phases of HBV natural history | Patient cohorts should include different ethnic groups, HBV (sub)genotypes, higher representation of women, individuals with HIV co-infection, pregnant and lactating people, and children; although these markers can reflect cccDNA transcription in the liver, more understanding is required on the factors regulating their expression |

| Combination of assays | It is unclear at present how best to combine biomarkers; there is no ‘silver bullet’ and determining how to integrate multiple markers and their kinetics presents major challenges | Combining HBcrAg, HBsAg and pgRNA levels predicts sustained response following treatment cessation in some settings; although these markers might reflect cccDNA transcription in the liver, more understanding is required on the factors regulating their expression; technical validation of different biomarkers for different treatment modalities in clinical trials is under way or planned; collaborations between multiple clinical trial sites is recommended to obtain sufficient statistical power; a viral biomarker composite score similar to the REACH-B175 might assist clinical decision-making; biomarkers could be combined to generate the score and to predict outcomes such as which patients would benefit from stopping therapy |

| Development of core-specific biomarkers | As HBcrAg represents multiple antigens, with HBeAg predominating, a specific core antigen biomarker would be a useful surrogate marker of cccDNA activity as its level is not affected by the presence of basal core promoter and/or precore mutants or peripheral clearance (for example, HBcAg or HBeAg antibodies) being contained in virions | Development of a core-specific biomarker is under way |

| Correlation of expression of biomarkers in liver and plasma/serum | It is unclear how accurately HBV serum biomarkers reflect the liver | Further studies in animal models and humans are required to correlate circulating markers with the intrahepatic environment |

| Definition of disease progression and treatment response | Biomarkers of treatment response and disease progression are needed | A panel of biomarkers is needed to enable clinicians to identify patients who could cease therapy with a lower risk of relapse; biomarkers of HCC are needed, particularly those that can replace or complement ultrasonography for HCC detection; issues around access to these assays must be improved, particularly in resource-limited settings |

| Development of immunological markers | Immunological markers are not as well developed as virological markers | Currently available immunological markers largely measure liver inflammation whereas, ideally, these biomarkers should predict the activity of immune targeting drugs and, ultimately, off-treatment response; to date, measuring cytokines and chemokines in the periphery has been of limited value as they are only present at the time of inflammation |

| Further studies on FNA | FNA (also known as needle biopsy) | Understanding the contribution of the relatively few hepatocytes within the FNA and how this correlates with the ‘gold standard’ liver biopsy from both an immunological and virological perspective; as FNAs are a very small representation of a large organ, with inherent risks in terms of sampling error, performing FNAs in large patient populations might be necessary; identifying suitable clinical trial sites with the necessary expertise for collection, processing and storage, and providing training for sites lacking expertise; ideal conditions for the storage of FNAs have not been defined |

cccDNA, covalently closed circular DNA; FNA, fine-needle aspiration; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; HBcAg, hepatitis B core antgen; HBcrAg, hepatitis B core-related antigen; HBeAg, hepatitis B e antigen; HBsAg, hepatitis B surface antigen; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; OBI, occult hepatitis B virus infection; pgRNA, pre-genomic RNA.

For patients with CHB undergoing, or ceasing current NUC therapy, no single biomarker is currently clearly superior in predicting treatment response or relapse across all stages of CHB. There is global consensus that achieving an HBV cure will require combination therapies, targeting different steps of the HBV replication cycle, and stimulating host immune responses to neutralize HBV infection and/or safely eradicate HBV-infected cells26. In turn, approaches that affect viral and immunological targets will require a combination of viral and immunological biomarkers to monitor progress towards the new treatment end points.

For the immediate future, HBeAg, HBsAg and HBV DNA will remain the most important viral serum biomarkers used in natural history and treatment end points because they are best validated to reflect outcomes. It is evident that biomarkers have different importance in various disease stages (HBeAg positive versus HBeAg negative), HBV genotypes and for different treatment modalities. On the other hand, HBV RNA and HBcrAg are expected to correlate with treatment response to current and new therapies but might not outperform HBsAg in predicting treatment outcome when each is taken in isolation. HBV RNA, HBcrAg and/or HBcAg tests need to be validated and standardized, and their sensitivity optimized. New biomarkers can help to dissect the mechanism of action of new drugs. Another possible benefit of these emerging biomarkers is their clinical usefulness in combination with conventional markers such as the demonstrated superiority of combining pgRNA and HBsAg levels at the time of stopping NUC for the prediction of off-treatment viral relapse71.

It is also important that biomarkers are validated for all major HBV genotypes, which exhibit marked differences in HBV natural history, disease progression and treatment response to peg-IFNα therapy161. Until new immune-mediated therapies are developed, peg-IFNα is likely to have a place in combination treatment regimens, yet it is only effective in patients with HBV infection of genotypes A and B and least effective for genotypes C and D. Although HBV sequencing and genotyping are not currently routinely undertaken prior to treatment initiation, this might need to be considered if peg-IFNα is included in treatment combinations. Although not routinely available in all settings, next-generation sequencing of complete HBV genomes prior to the initiation of antiviral therapy also shows promise as a biomarker of treatment response on NUCs, with the identification of basal core promoter mutations even at a low frequency associated with reduced likelihood of functional cure162 and ALT flare163 on therapy. As new curative therapies for HBV are developed, the effect of HBV variants on treatment response warrants further investigation where access to next-generation sequencing technology is available.

Although a number of biomarkers have been described that can monitor the course of HBV infection, it is vital, when interpreting their kinetics and variations, to determine whether they are informing on target engagement of the therapeutic agent and/or are a reflection of intrahepatic replication and immune control. The emerging biomarkers will have an important role as exploratory markers for end points and mode-of-action studies. No one biomarker yet fits all novel antiviral modalities, and an integrative approach might be necessary because the serological marker used is dependent on the mode of action of the antiviral drugs. More translational studies are required, and the relevance of these assays in the various phases of CHB natural history and in individuals of different ethnicities, age groups, sex and HBV genotypes is yet to be determined.

Currently, there are no serum or liver immunological biomarkers that are superior to clinical and virological markers in following the natural history of CHB and in monitoring therapy and HBV-specific immune responses. Markers that reflect the liver compartment will become increasingly important as access to liver tissue and standard liver biopsy become more difficult, with fine-needle aspiration (also known as fine-needle biopsy) showing promise. Monitoring intrahepatic activity will become increasingly important as therapies targeting HBV cccDNA are developed. However, in the interim, consideration should also be given to identifying the most appropriate biomarkers for treatment response using finite therapies that might reduce HBV DNA to below the limit of quantification but where HBsAg remains detectable, currently defined as a ‘partial functional cure’164. ‘Partial functional cure’ might represent an important interim step as we progress on the path to increased rates of functional cure with new finite therapies. It is likely that pgRNA, HBcrAg and its HBcAg component as emerging biomarkers as well as additional yet-unidentified markers will have an important role; therefore, an HBcAg-specific biomarker would be a valuable additional tool to help de-convolute the multiple components of the current HBcrAg assay. Biomarkers of OBI are also required as are markers that will predict the likelihood of progression to HCC, enabling earlier interventions and more accurate risk assessment. Finally, all these resources need to be made available to all persons living with CHB in an equitable and fair manner, and particularly in resource-limited settings, where much of the burden of HBV worldwide lies, with a pressing need for POC biomarkers. In partnership with the HBV-affected community, academia, clinicians, the pharmaceutical and biotech industries, and organizations such as the HBV Forum and the Hepatitis B Foundation, ICE-HBV will work with all stakeholders to ensure this indeed occurs.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Workshop Participants: The ICE-HBV HBV Serum Biomarkers Workshop was held virtually in two sessions on 5th and 12th October 2020 (https://ice-hbv.org/hbv-serum-biomarkers-workshop/). The chairs of the workshop A.K. and P.R. organized the meeting with C.P. K.M.C., M.D., P.F., D.G., J.H., H.L.A.J., D.T.Y.L., T.P., B.T. and F.V.P. presented at the workshop. O.A., M.B.M., T.M.B., H.L.Y.C., G.A.C., W.D., A.M.G., A.G., O.L., M.M., V.M., U.P., J.Y., M.F.Y. and F.B. chaired the workshop sessions and/or participated in the panel discussions. The authors thank T. Candy (VIDRL, RMH, Doherty Institute, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia) for assistance with the preparation of the manuscript.

Author contributions

P.R., A.K., K.M.C., M.D., P.F., D.G., J.H., H.L.J., D.L., M.C.P., T.P., B.T., F.B., O.M.A., M.B.M., T.B., H.L.Y.C., G.A.C., W.E.D., A.M.A.G., A.J.G., K.J., O.L., M.K.M., V.M., U.P., J.C.Y., M.F.Y. and F.Z. researched data for the article. P.R., A.K., K.M.C., M.D., P.F., D.G., J.H., H.L.J., D.L., M.C.P., T.P., B.T., F.B., O.M.A., M.B.M., T.B., H.L.Y.C., G.A.C., W.E.D., A.M.A.G., A.J.G., K.J., O.L., M.K.M., V.M., U.P., J.C.Y., M.F.Y. and F.Z. contributed substantially to discussion of the content. P.R., A.K., K.M.C., M.D., P.F., D.G., J.H., H.L.J., D.L., M.C.P., T.P., B.T., F.B., O.M.A., M.B.M., T.B., H.L.Y.C., G.A.C., W.E.D., A.M.A.G., A.J.G., O.L., M.K.M., V.M., U.P., J.C.Y., M.F.Y. and F.Z. wrote the article. P.R., A.K., K.M.C., M.D., P.F., D.G., J.H., H.L.J., D.L., M.C.P., T.P., B.T., F.B., O.M.A., M.B.M., T.B., H.L.Y.C., G.A.C., W.E.D., A.M.A.G., A.J.G., K.J., O.L., M.K.M., V.M., U.P., J.C.Y., M.F.Y. and F.Z. reviewed and/or edited the manuscript before submission.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology thanks Jia-Horng Kao, Philippa Matthews and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Competing interests