Abstract

Objectives

We studied apolipoprotein C‐III (apoC‐III) in relation to diabetic kidney disease (DKD), cardiovascular outcomes, and mortality in type 1 diabetes.

Methods

The cohort comprised 3966 participants from the prospective observational Finnish Diabetic Nephropathy Study. Progression of DKD was determined from medical records. A major adverse cardiac event (MACE) was defined as acute myocardial infarction, coronary revascularization, stroke, or cardiovascular mortality through 2017. Cardiovascular and mortality data were retrieved from national registries.

Results

ApoC‐III predicted DKD progression independent of sex, diabetes duration, blood pressure, HbA1c, smoking, LDL‐cholesterol, lipid‐lowering medication, DKD category, and remnant cholesterol (hazard ratio [HR] 1.43 [95% confidence interval 1.05–1.94], p = 0.02). ApoC‐III also predicted the MACE in a multivariable regression analysis; however, it was not independent of remnant cholesterol (HR 1.05 [0.81–1.36, p = 0.71] with remnant cholesterol; 1.30 [1.03–1.64, p = 0.03] without). DKD‐specific analyses revealed that the association was driven by individuals with albuminuria, as no link between apoC‐III and the outcome was observed in the normal albumin excretion or kidney failure categories. The same was observed for mortality: Individuals with albuminuria had an adjusted HR of 1.49 (1.03–2.16, p = 0.03) for premature death, while no association was found in the other groups. The highest apoC‐III quartile displayed a markedly higher risk of MACE and death than the lower quartiles; however, this nonlinear relationship flattened after adjustment.

Conclusions

The impact of apoC‐III on MACE risk and mortality is restricted to those with albuminuria among individuals with type 1 diabetes. This study also revealed that apoC‐III predicts DKD progression, independent of the initial DKD category.

Keywords: apolipoprotein C‐III, cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, diabetic nephropathy, dyslipidemia, mortality, type 1

Introduction

Despite improved treatment strategies, individuals with type 1 diabetes remain burdened with marked premature mortality, especially due to cardiovascular causes of death [1]. However, the mortality risk within this population is unequally distributed. While several factors contribute to the prognosis, its main determinant is undoubtedly the presence and degree of diabetic kidney disease (DKD) [2].

We and others have established dyslipidemia as a pivotal risk factor for DKD in type 1 diabetes, with hypertriglyceridemia showing the strongest link [3, 4]. Triglyceride concentrations have also been highly associated with events of cardiovascular disease in this patient population [5, 6]. Yet, in the context of atherosclerosis, the current understanding is that triglycerides foremost act as a surrogate marker of triglyceride‐rich lipoprotein particles (TRLs) and their cholesterol‐enriched remnants, which accumulate in atherosclerotic plaques—whereas triglycerides, per se, do not [7].

Apolipoprotein C‐III (apoC‐III) is present on circulating apolipoprotein B (apoB)–containing TRLs, HDL particles, and—to a smaller extent—on LDL particles [8]. ApoC‐III is a key regulator of triglyceride homeostasis acting through multiple pathways, such as inhibition of lipoprotein lipase (LPL)–mediated TRL lipolysis and impairment of TRL remnant clearance, hence amplifying the plasma resident time of these particles [8]. Besides, experimental evidence implies several proatherogenic outcomes of apoC‐III that go beyond the effects of the lipids. Even though apoC‐III does not bind to proteoglycans in the arterial wall itself, it modulates endothelial function and adhesiveness, facilitating the subendothelial accumulation of atherogenic lipoproteins [9]. ApoC‐III further augments arterial inflammation via various pro‐inflammatory trails [10].

In humans, apo‐CIII is encoded by the APOC3 gene on chromosome 11q23. Loss‐of‐function mutations in the gene have been associated with ∼40% lower concentrations of triglycerides, conferring a markedly reduced risk of ischemic cardiovascular disease [11, 12]. Intriguingly, glucose induces APOC3 transcription in mice [13], whereas insulin appears to have an opposite, repressing effect—supposedly via the insulin‐response element promoter on the gene [14]. Thus, apoC‐III has emerged as a possible link connecting hyperglycemia, hypertriglyceridemia, and cardiovascular disease in type 2 diabetes [13].

However, individuals with type 1 diabetes are also distinguished by elevated plasma apoC‐III levels [15, 16]. Importantly, Kanter et al. recently reported an association between apoC‐III concentrations and cardiovascular disease in type 1 diabetes, independent of LDL‐cholesterol (LDL‐C), HDL‐cholesterol (HDL‐C), and several nonlipid risk factors [17]. Along with its connection with cardiovascular outcomes, a cross‐sectional association between apoC‐III and albumin excretion rate (AER) has been seen in the DCCT/EDIC cohort comprising individuals with type 1 diabetes [18]. Yet, whether the presence and degree of DKD modulate the association between apoC‐III and macrovascular disease in type 1 diabetes is so far not known. Nor has it been elucidated whether elevated apoC‐III concentrations translate into an elevated risk of DKD progression.

Therefore, in a multicenter cohort comprising 3966 individuals with type 1 diabetes, we aimed to study the serum concentration of apoC‐III with respect to DKD progression, cardiovascular events, and all‐cause mortality. Our particular interest was to establish whether the associations are different in individuals with and without DKD.

Materials and methods

Study cohort

This study is part of the ongoing Finnish Diabetic Nephropathy (FinnDiane) Study, established in 1997 to assess chronic complications of diabetes. The FinnDiane study protocol has been published previously [19]. The FinnDiane participants have not been preselected based on DKD or other diabetic complications—the only requirement for partaking is type 1 diabetes as determined by international diagnostic criteria. To ensure the correct diabetes type, only those with diabetes onset under the age of 40 and permanent insulin treatment initiated within 1 year since diagnosis were included in the present study. An available apoC‐III measurement at the baseline visit was also required. The inclusion criteria were met by 3966 individuals.

Ethical considerations

The research plan was approved by the Ethical Committee of the Helsinki and Uusimaa Hospital District and the study was performed according to the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants provided their written informed consent prior to their inclusion in the study.

Lipids and apolipoproteins

Venous blood was drawn after a light breakfast. Triglycerides, cholesterol, and HDL‐C concentrations in total serum were analysed by automated enzymatic methods using the Konelab 60i analyser (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Finland). Serum concentrations of apoC‐III were measured immuneturbidometrically (Kamiya Biomedical Company, Seattle, WA, USA). ApoB concentrations were determined using a Cobas Mira analyser by immunoprecipitation with a commercial kit (Orion Diagnostica, Espoo, Finland) until 2006, whereafter an immunoprecipitation method with a Konelab 60i analyser and a kit from the same manufacturer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) were used. LDL‐C was calculated using the recently introduced formula by Sampson et al. [20], which—in contrast to previous ones—can be used in hypertriglyceridemic samples. Remnant cholesterol was calculated as total cholesterol‐LDL‐C–HDL‐C [21].

Diabetic kidney disease

DKD was categorized according to the most advanced stage prebaseline. Normal AER was defined as AER <20 μg/min, or <30 mg/24 h, or an albumin–creatinine ratio (ACR) <2.5 mg/mmol for men and <3.5 mg/mmol for women; microalbuminuria as an AER ≥20 and <200 μg/min, or ≥30 and <300 mg/24 h, or an ACR ≥2.5 and <25 mg/mmol for men or ≥3.5 and <35 mg/mmol for women; and macroalbuminuria as an AER ≥200 μg/min, or ≥300 mg/mmol, or an ACR ≥25 mg/mmol for men or ≥35 mg/mmol for women in two out of three consecutive measurements. Urine samples during fever, menstruation, heart failure, or after physical strain were excluded. Glomerular filtration rate was estimated (eGFR) using the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD‐EPI) formula [22]. Kidney failure was defined as ongoing dialysis or kidney transplantation due to DKD.

Progression of DKD was defined as reclassification to a more advanced albuminuria stage or initiation of kidney replacement therapy, as retrieved from medical records. The subjects were followed until progression or the most recent date of sustained DKD with a median (interquartile range [IQR]) follow‐up time of 7.6 (4.4–12.2) years.

Cardiovascular disease and mortality

A major adverse cardiac event (MACE) was defined as the first of acute myocardial infarction (AMI), coronary revascularization, or stroke through 2017. Both fatal and nonfatal events were included. These data were retrieved from the National Care Register for Health Care using the ICD and Nordic Classification of Surgical Procedure codes listed in Table S1. Only the study participants free of cardiovascular events prebaseline (90.7%) were included in the analyses where MACE served as the endpoint. The median follow‐up time for the MACE was 14.3 (10.8–17.2) years. Mortality data were obtained through 2017 from Statistics Finland, and regarding all‐cause mortality, the study participants were followed for 14.8 (11.1–17.2) years. The cause of death was classed as cardiovascular if the immediate and/or the underlying cause of death was recorded as a disease of the circulatory system (ICD‐10 I00‐I99).

Statistical analyses

Data were analysed using the R open‐source software version 4.1.1 (http://www.r‐project.org). Variable symmetry was evaluated graphically and variables with skewed distributions (apoC‐III, remnant cholesterol, triglycerides, eGFR, and high‐sensitivity C‐reactive protein [hs‐CRP]) were log‐transformed in the regression analyses. In the analyses including hs‐CRP, only those with hs‐CRP concentration below 10 mg/l were included (n = 3664) to avoid the interference of potential ongoing infections. Between‐group differences were analysed using Student's t‐test, ANOVA, Mann–Whitney U test, Kruskal–Wallis test, or Pearson's chi‐squared test, as suitable. The linear correlation between variables was assessed using Pearson's correlation coefficient. A p‐value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

The effects of apoC‐III on the outcomes of interest—progression of DKD, MACE, and all‐cause mortality—were investigated with multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression analyses. The results from these analyses are presented as hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The extent of multicollinearity in the regression models was tested with variance inflation factors, which did not exceed three in any of the models used. Separate Cox regression analyses for MACE and mortality stratified by DKD were performed. In these analyses, the individuals with micro‐ and macroalbuminuria were pooled, considering the arbitrary cut‐off values for these DKD categories.

Kaplan–Meier analysis was used to generate survival curves portraying time‐to‐event, with apoC‐III concentration quartiles as strata. Lastly, the relationship between apoC‐III and MACE/mortality was assessed allowing for nonlinearity by using restricted cubic splines. The number of knots was set to three based on Akaike‐ and Bayesian information criterion minimization. Reference was assigned to the median of apoC‐III. The Wald test was used to check for the presence of nonlinearity in these analyses.

Results

Clinical characteristics

Clinical characteristics of the complete study cohort appear in Table 1, stratified by quartiles of apoC‐III in Table S2, and by DKD category at baseline in Table S3. Of the study participants, 47.9% were women, their mean age was 39.2 years, and the mean diabetes duration 23.0 years. The cohort's median apoC‐III concentration was 7.0 (IQR 5.5–9.1) mg/dl, and a correlation between apoC‐III and remnant cholesterol (r = 0.58, p < 0.001), triglycerides (0.56, p < 0.001), and HbA1c (r = 0.16, p < 0.001) was observed. With rising apoC‐III quartile, the individuals were older, had a longer diabetes duration, worse glycemic control, higher blood pressure, and higher lipid levels. A larger proportion of individuals in the upper quartiles belonged to advanced stages of DKD. However, no difference in the sex distribution between the quartiles was noted.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of the complete study cohort

| N | 3966 |

|---|---|

| Apolipoprotein C‐III (mg/dl) | 7.0 (5.5–9.1) |

| Sex (women) | 1901 (47.9%) |

| Age (years) | 39.2 ± 12.6 |

| Age at diabetes onset (years) | 16.1 ± 9.3 |

| Diabetes duration (years) | 23.0 ± 12.9 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 25.24 ± 3.81 |

| Baseline diabetic kidney disease category | |

| Normal albumin excretion rate | 2603 (66.4%) |

| Microalbuminuria | 515 (13.1%) |

| Macroalbuminuria | 493 (12.6%) |

| Kidney failure | 310 (7.9%) |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 135 ± 19 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 79 ± 10 |

| History of smoking | |

| Current | 855 (23.2%) |

| Former | 874 (23.7%) |

| Never | 1957 (53.1%) |

| Total cholesterol (mmol/l) | 4.84 ± 0.95 |

| HDL‐cholesterol (mmol/l) | 1.39 ± 0.41 |

| LDL‐cholesterol (mmol/l) | 2.92 ± 0.86 |

| Triglycerides (mmol/l) | 1.03 (0.77–1.46) |

| Remnant cholesterol (mmol/l) | 0.43 (0.33–0.66) |

| Apolipoprotein B (mg/dl) | 84.0 ± 22.9 |

| HbA1c (mmol/mol) | 68.6 ± 16.1 |

| HbA1c (%) | 8.4 ± 3.6 |

| High‐sensitivity C‐reactive protein (mg/l) | 1.56 (0.83–3.00) |

| Estimated glomerular filtration rate (ml/min/1.73 m2) | 101 (80–115) |

| Use of RAAS inhibitor a (yes) | 1267 (32.2%) |

| Use of lipid‐lowering medication (yes) | 729 (18.5%) |

Note. Data are mean ± standard deviation, median (interquartile range), or n (%).

Abbreviation: RAAS, renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system.

ACE inhibitor and/or angiotensin II receptor antagonist.

ApoC‐III and DKD

We observed a cross‐sectional association between apoC‐III concentration and DKD category (Table S3); the median (IQR) apoC‐III was 6.5 (5.2–8.2), 6.8 (5.4–9.2), 8.9 (6.5–11.6), and 9.9 (7.5–13.2) mg/dl in those with normal AER, microalbuminuria, macroalbuminuria, and kidney failure at baseline, respectively (p for trend <0.001). Of the 310 individuals with kidney failure, 236 (76.1%) had received a kidney transplant, and their baseline apoC‐III was lower (8.9 [7.1–12.2] mg/dl) than what was noted for those treated with dialysis (12.3 [9.0–16.1] mg/dl), p < 0.001. The correlation between apoC‐III and AER was also significant: r = 0.27, p < 0.001.

Progression of DKD occurred in 451 individuals, corresponding to 14.6% of the 3085 individuals with available progression status. The progressors were characterized by a higher median apoC‐III concentration (8.1 [6.1–10.9] mg/dl) than that of those who did not progress (6.6 [5.2–8.3] mg/dl), p < 0.001.

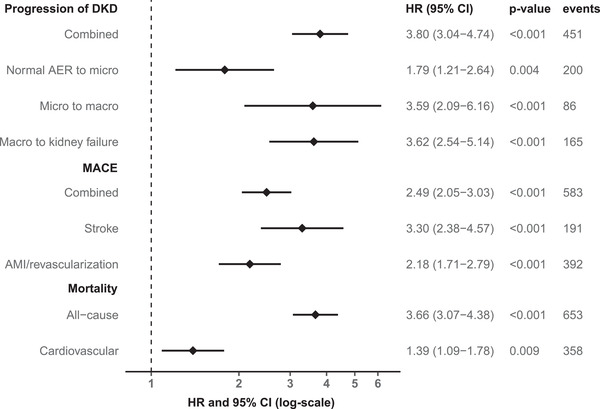

Results from Cox regression analyses for DKD progression are presented in the first panel of Table 2. Log‐transformed apoC‐III predicted progression, independent of the most stringent adjustment model, with an HR of 1.43 (95% CI 1.05–1.94, p = 0.02) when the baseline DKD category was used as a covariate instead of eGFR. The HR was 1.41 (1.03–1.91, p = 0.03) when remnant cholesterol was replaced by triglycerides in the model (Table S4) and 1.91 (1.47–2.49, p < 0.001) when apoB was chosen as a covariate (Table S5). Adjustment for hs‐CRP did not alter the significance levels of the point estimates (HR 1.43 [1.05–1.94, p = 0.02] with remnant cholesterol and hs‐CRP in the model), in contrast to additional adjustment for eGFR (Table 2, Tables S4 and S5), likely reflecting the strong influence of kidney function. Notably, apoC‐III predicted progression at all stages of the disease; HRs adjusted for sex and diabetes duration for the different steps of progression (normal AER to microalbuminuria, micro‐ to macroalbuminuria, and macroalbuminuria to kidney failure) appear in Fig. 1.

Table 2.

Cox proportional hazards regression analyses with different levels of adjustment reporting hazard ratios with 95% confidence intervals for apolipoprotein C‐III (apoC‐III)

| Hazard ratio (95% confidence interval) | p‐value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Diabetic kidney disease (DKD) progression Individuals, n = 3085 Events n = 451 (14.6%) | ||||

| Model 1 | 3.80 (3.04–4.74) | <0.001 | ||

| Model 2 | 2.41 (1.88‐3.08) | <0.001 | ||

| Model 3 | 2.04 (1.59–2.64) a | 1.19 (0.90–1.58) b | <0.001 a | 0.21 b |

| Model 4 | 1.43 (1.05–1.94) a | 0.90 (0.66–1.24) b | 0.02 a | 0.53 b |

|

Major adverse cardiac event Individuals, n = 3597 Events, n = 583 (16.2%) | ||||

| Model 1 | 2.49 (2.05–3.03) | <0.001 | ||

| Model 2 | 1.78 (1.43–2.22) | <0.001 | ||

| Model 3 | 1.30 (1.03–1.64) a | 1.31 (1.03–1.65) b | 0.03 a | 0.03 b |

| Model 4 | 1.05 (0.81–1.36) a | 1.06 (0.81–1.38) b | 0.71 a | 0.67 b |

|

Mortality Individuals, n = 3966 Events, n = 653 (16.5%) | ||||

| Model 1 | 3.66 (3.07–4.38) | <0.001 | ||

| Model 2 | 2.59 (2.11–3.18) | <0.001 | ||

| Model 3 | 1.56 (1.26–1.93) a | 1.55 (1.24–1.94) b | <0.001 a | <0.001 b |

| Model 4 | 1.28 (1.01–1.63) a | 1.27 (0.99–1.63) b | 0.04 a | 0.06 b |

Note. Model 1: sex, diabetes duration; Model 2: model 1 + systolic blood pressure, HbA1c, smoking status, LDL‐cholesterol, lipid‐lowering medication; Model 3: model 2 + baseline DKD categorya (left column) or estimated glomerular filtration rateb (right column); Model 4: model 3 + remnant cholesterol.

Fig. 1.

Forest plot illustrating sex‐ and diabetes duration–adjusted hazard ratios with 95% confidence intervals for apolipoprotein C‐III regarding separate components of the primary endpoints of interest; DKD, diabetic kidney disease; micro, microalbuminuria; macro, macroalbuminuria; MACE, major adverse cardiac event; AMI, acute myocardial infarction.

ApoC‐III and cardiovascular disease

Of the 3597 individuals included in the cardiovascular analyses, 583 (16.2%) experienced a MACE. The first‐occurring MACE was fatal or nonfatal AMI or coronary revascularization in 392 (67.2%) individuals and fatal or nonfatal stroke in 191 (32.8%). Those who experienced a MACE during follow‐up had higher baseline apoC‐III concentration than those who did not—7.7 (5.8–10.5) versus 6.7 (5.4–8.7) mg/dl, p < 0.001.

ApoC‐III was associated with the incident MACE when adjusting for sex, diabetes duration, systolic blood pressure, HbA1c, smoking status, LDL‐C, the use of lipid‐lowering medication, and baseline DKD category (Table 2). This was also the case when the DKD category was replaced by eGFR (Table 2). When the analysis was further adjusted for hs‐CRP, the point estimate for apoC‐III was unaffected in the DKD‐adjusted model (HR 1.30 [1.03–1.64, p = 0.03]) and the impact of hs‐CRP in the eGFR‐adjusted model was minor (1.29 [1.02–1.63, p = 0.03]). However, the associations between apoC‐III and MACE lost significance when remnant cholesterol was added to the models (HR 1.05 [0.81–1.36, p = 0.71] and HR 1.06 [0.81–1.38, p = 0.67], respectively), and the same was observed when remnant cholesterol was replaced by triglycerides (Table S4). HRs for the MACE components are shown separately in Fig. 1.

Next, we wanted to study those with normal AER, albuminuria, and kidney failure separately to assess whether DKD alters the association between apoC‐III and cardiovascular disease. These analyses (Table 3) revealed an association between apoC‐III and MACE only in the individuals with albuminuria—the HR for apoC‐III in this group was 1.60 (1.16–2.19, p = 0.004) with adjustment for several key modifiable and nonmodifiable risk factors (model 2) and decreased to 1.33 (0.91–1.94, p = 0.14) when remnant cholesterol was added as a covariate (model 3). The association between apoC‐III and the cardiovascular outcome was nonsignificant at all levels of adjustment in individuals with normal AER and kidney failure (Table 3).

Table 3.

Cox proportional hazards regression analyses with different levels of adjustment reporting hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for apoC‐III for individuals with normal albumin excretion rate (AER), albuminuria, and kidney failure separately

| Normal AER | Albuminuria | Kidney failure | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | p‐value | HR (95% CI) | p‐value | HR (95% CI) | p‐value | |

| MACE | ||||||

|

Individuals, n = 2496 Events, n = 223 (8.9%) |

Individuals, n = 878 Events, n = 260 (29.6%) |

Individuals, n = 206 Events, n = 97 (47.1%) |

||||

| Model 1 | 1.43 (0.96–2.12) | 0.07 | 1.96 (1.48–2.60) | <0.001 | 1.18 (0.74–1.88) | 0.48 |

| Model 2 | 1.25 (0.83–1.90) | 0.29 | 1.60 (1.16–2.19) | 0.004 | 0.94 (0.53–1.68) | 0.84 |

| Model 3 | 0.97 (0.62–1.51) | 0.88 | 1.33 (0.91–1.94) | 0.14 | 0.85 (0.45–1.59) | 0.60 |

| Mortality | ||||||

|

Individuals, n = 2603 Events, n = 177 (6.8%) |

Individuals, n = 1008 Events, n = 284 (28.2%) |

Individuals, n = 310 Events, n = 187 (60.3%) |

||||

| Model 1 | 1.82 (1.16–2.84) | 0.009 | 2.61 (1.99–3.42) | <0.001 | 1.33 (0.95–1.87) | 0.10 |

| Model 2 | 1.61 (1.01–2.54) | 0.04 | 1.99 (1.47–2.70) | <0.001 | 1.30 (0.89–1.91) | 0.18 |

| Model 3 | 1.38 (0.84–2.27) | 0.21 | 1.49 (1.03–2.16) | 0.03 | 1.16 (0.77–1.74) | 0.49 |

Note. Model 1: sex, diabetes duration; Model 2: model 1 + systolic blood pressure, HbA1c, smoking status, LDL‐cholesterol, lipid‐lowering medication; Model 3: model 2 + remnant cholesterol.

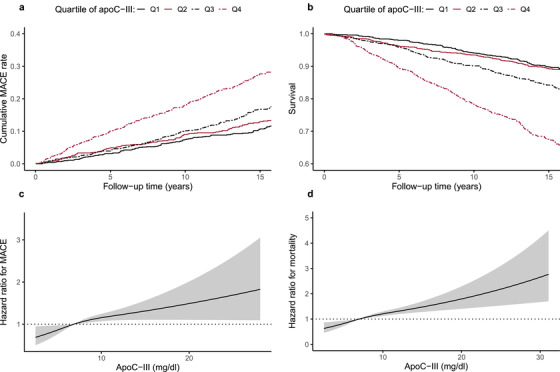

We further stratified the population by quartiles of apoC‐III and found a markedly higher cumulative risk of MACE in the highest quartile compared to the lower three (Kaplan–Meier plot in Fig. 2a; log‐rank p < 0.001). Consequently, as described in the methods section, we included apoC‐III as a nonlinear term in Cox regression using restricted cubic splines to test whether the relationship between apoC‐III and MACE was nonlinear. This analysis yielded an unadjusted nonlinear p‐value of 0.01. However, when we adjusted for sex, diabetes duration, and baseline DKD category, the relationship between apoC‐III and the cardiovascular endpoint did not deviate from linearity (nonlinear p = 0.18), as Fig. 2c illustrates.

Fig. 2.

Kaplan–Meier curves stratified by quartiles of apolipoprotein C‐III (apoC‐III) concentration with respect to (a) the cumulative major adverse cardiac event (MACE) rate and (b) mortality; black solid line, quartile 1; red solid line, quartile 2; black dashed line, quartile 3; red dashed line, quartile 4. The two latter figures illustrate the relationship between apoC‐III and (c) the MACE/(d) mortality allowing for nonlinearity. In these models, apoC‐III was included as a restricted cubic spline using three knots. Reference hazard ratio = 1 was set to the median of apoC‐III in the studied populations. The analyses in (c) and (d) are adjusted for sex, diabetes duration, and the category of diabetic kidney disease at baseline.

ApoC‐III and mortality

In all, 653 (16.5%) individuals died during follow‐up and 358 (54.8%) of the deaths were cardiovascular. The individuals who died had a higher baseline apoC‐III concentration than that of those who survived—8.4 (6.3–11.4) versus 6.7 (5.4–8.7) mg/dl, p < 0.001.

Table 2 shows that apoC‐III predicted all‐cause mortality independent of all covariates in model 4, comprising DKD category—the HR was 1.28 (1.01–1.63, p = 0.04). The point estimate was 1.37 (1.05–1.77, p = 0.02) when hs‐CRP was included in the model, 1.26 (0.99–1.61, p = 0.06) when remnant cholesterol was replaced by triglycerides (Table S4), and 1.27 (0.99–1.63, p = 0.06) when eGFR was incorporated instead of the DKD category (Table 2). In a subanalysis, apoC‐III was associated with cardiovascular mortality separately (adjusted HR 1.39 [1.09–1.78], p = 0.009, Fig. 1). Of note, the fully adjusted Cox regression analyses stratified by DKD category revealed that the association between apoC‐III and mortality was solely mediated by the individuals with albuminuria (Table 3, Table S4 and S6)—hence, this finding was analogous to the MACE observations previously presented. Another similarity with the MACE analyses was the all‐cause mortality risk in the highest apoC‐III quartile, which was distinct from the rest of the population (Fig. 2b, log‐rank p < 0.001). The relationship between apoC‐III and all‐cause mortality was nonlinear (p for nonlinearity <0.001); however, after adjustment for sex, diabetes duration, and DKD category, the nonlinearity disappeared (p for nonlinearity 0.13; Fig. 2d).

The impact of apoC‐III on the association between apoB and the outcomes

Considering the mechanistic connection between apoC‐III and apoB‐containing lipoprotein particles, we wanted to clarify the effect of apoC‐III on the relationship between apoB and the endpoints.

We found an association between apoB and DKD progression in the Cox regression analyses despite adjustment for sex, diabetes duration, systolic blood pressure, HbA1c, smoking status, and baseline DKD category (HR 1.07 [1.02–1.12] for a 10‐unit increase in apoB concentration, p = 0.003). However, the inclusion of apoC‐III to the model weakened apoB as a predictor—its HR dropped to 1.04 (0.99–1.08), p = 0.12, whereas the association between the endpoint and apoC‐III remained significant (HR 1.91 [1.47–2.49, p < 0.001], Table S5). This finding implies that apoC‐III is a stronger predictor of DKD progression than apoB in the setting of the covariates used.

However, when it comes to the cardiovascular outcome, the discovery was somewhat different. With a regression model covering nonmodifiable confounders, modifiable confounders, and apoB to depict the atherogenic lipoproteins (model 1 in Table S5), both apoC‐III (1.64 [1.30–2.06, p < 0.001]) and apoB (1.08 [1.04–1.13, p < 0.001] for a 10‐unit increase) were significantly associated with the endpoint. Removing apoC‐III from the model increased the estimate for apoB to 1.11 (1.07–1.15, p < 0.001). When DKD category was further adjusted for, the point estimate for apoB remained significant (1.07 [1.03–1.12, p < 0.001]), although the association between apoC‐III and the MACE was lost (Table S5).

As for mortality, the association with apoB was independent of sex and diabetes duration (HR for apoB 1.13 [1.09–1.16, p < 0.001]) and further of apoC‐III (HR for apoB 1.05 [1.01–1.09, p = 0.006]). Yet, the association between apoB and the outcome was lost with additional adjustment, in contrast to the results retrieved for apoC‐III (Table S5).

Discussion

ApoC‐III has received attention as a potential driver of residual cardiovascular risk in the general population [23, 24, 25], and this connection has recently been highlighted in individuals with type 1 diabetes as well [17, 26, 27]. However, to the best of our knowledge, the current study is the first one to demonstrate the impact of DKD on the association between apoC‐III and macrovascular endpoints.

DKD has been portrayed as the most devastating complication of type 1 diabetes due to its strong association with cardiovascular morbidity and mortality, and the cardiovascular risk goes together with the deterioration of kidney disease. Hence, to improve the prognosis of the patients, attempts have been made to identify factors predicting the occurrence and progression of DKD at an early stage. In the 1990s, Hughes et al. [28] reported higher apoC‐III concentrations in individuals with type 1 diabetes and advanced DKD compared with their nondiabetic counterparts. A decade later, findings from the DCCT/EDIC cohort [18] proposed a correlation between apoC‐III and microvascular diabetic complications, depicted by AER and the severity of diabetic retinopathy, in a cross‐sectional study design. Our results extend the previous findings by showing that apoC‐III also predicts the progression of DKD, independent of the initial DKD category and well‐recognized risk factors such as diabetes duration, HbA1c, blood pressure, and smoking.

In a recent case‐control study by Kanter et al. [17], comprising 181 subjects with type 1 diabetes from the CACTI cohort, apoC‐III was a stronger predictor of cardiovascular events than plasma triglycerides. With diabetic mouse models, Kanter et al. demonstrated that insulin deficiency increases apoC‐III levels approximately twofold and, importantly, that the reduction of apoC‐III prevents atherosclerosis. These findings made a convincing case for proposing apoC‐III as a major cardiovascular risk factor in type 1 diabetes.

The analyses of the current study confirm that baseline apoC‐III concentration predicts incident cardiovascular events in individuals with type 1 diabetes (n = 3597) followed for 14.3 (10.8–17.2) years. In our cohort, the association between apoC‐III and the MACE was independent of both LDL‐C concentration and lipid‐lowering therapy but lost significance when remnant cholesterol was accounted for. This raises the question of whether remnant cholesterol is an intermediate step on the pathway between apoC‐III and atherosclerosis. Considering the TRL‐metabolism‐modulating effects of apoC‐III [8], as well as the role of TRL lipids (particularly remnant cholesterol) in the development of atherosclerotic plaques [21], this theory is plausible.

However, in contrast to our hypothesis, systemic inflammation—at least when characterized by hs‐CRP—had minor effects on the association between apoC‐III and the MACE. The findings were analogous regarding the other endpoints of the study. Extensive previous research has associated chronic inflammation with the development of diabetic complications [29, 30, 31], and since apoC‐III has also been found to promote inflammation [10], one could have expected inflammation to mediate at least part of the outcomes of apoC‐III. Additional and multiple inflammatory markers should be appraised in the future to untangle this relationship fully, but based on the information our study provides, it appears that the actions of apoC‐III that increase the plasma resident time of TRL remnant particles are key.

However, the TRL remnants do not seem to explain another aspect of the results, namely the novel discovery that the association between apoC‐III and cardiovascular events is driven by individuals with albuminuria. Rather surprisingly, no association was noted between apoC‐III and the composite endpoint in the study participants who had normal AER or kidney failure. What could explain this finding? One possible differentiating factor that goes beyond the TRL lipids could be endothelial dysfunction—evidently present in diabetes [32], but especially when albuminuria co‐exists [33]. ApoC‐III has been claimed to increase the endothelial cell expression of vascular cell adhesion molecule‐1 and intercellular cell adhesion molecule‐1 by activation of PKCβ and NF‐ΚB [9]. Hence, the actions of apoC‐III lead to augmented adhesion of monocytes to endothelial cells [9] as well as inflammasome activation and impairment of endothelial regeneration after injury, resulting in organ damage [10]. Notably, in atherosclerosis, endothelial cell dysfunction plays a crucial role in provoking monocyte recruitment into the arterial intima and enhancing lipoprotein deposition, foam cell creation, and plaque progression and is, thus, considered a prerequisite for the development of atheromas [34]. Among the study population with kidney failure, a potential relationship between apoC‐III and macrovascular disease could have been attenuated by the overwhelming cardiovascular risk that burdens these individuals. Yet, it is also noteworthy that dysregulated apoC‐III production has been proposed as a putative link between immunosuppressive agents and secondary dyslipidemia [35, 36], which is frequently encountered in individuals undergoing immunosuppressive therapy. Since 76% of the study participants with kidney failure in this cohort had received a renal transplant, it is possible that the effects of immunosuppression on apoC‐III per se could account for the observed disparity between the albuminuria and the kidney failure groups.

In a descriptive time‐to‐event Kaplan–Meier analysis, the study participants in the uppermost quartile of apoC‐III displayed an outstandingly superior risk of cardiovascular events. Although this nonlinear association disappeared after adjustment, the linear relationship between apoC‐III and MACE remained strong, suggesting that the risk of MACE increases with a growing concentration of apoC‐III. This finding, together with the results from Cox regression analyses, supports the view of apoC‐III as an appealing treatment target to reduce TRLs and, consequently, the cardiovascular risk. Volanesorsen, a second‐generation antisense nucleotide agent designed to cut the production of apoC‐III by targeting its mRNA, has been developed for this purpose [37]. In clinical studies, the agent has efficiently reduced plasma triglycerides in individuals with familial chylomicronemia syndrome [38], a genetic disorder characterized by LPL deficiency, as well as in individuals with type 2 diabetes [39] and varying degrees of hypertriglyceridemia [40]. To the best of our knowledge, no studies on volanesorsen have been conducted in individuals with type 1 diabetes yet. Therefore, it remains to be discovered whether apoC‐III inhibitors will be incorporated into the treatment regimen of individuals with type 1 diabetes in the future, and in that case, what the effects on microvascular complications such as DKD may be.

We further investigated apoC‐III in relation to all‐cause mortality. Interestingly, apoC‐III was a strong predictor of premature death in our cohort—even after accounting for eGFR, which has traditionally been considered a potent risk factor. However, after stratifying the cohort based on the DKD category, an association independent of the most stringent adjustment level was—again—only seen in the subjects with albuminuria. There was an association in individuals with normal AER as well; yet, it did not persist after adjustment for remnant cholesterol/triglycerides. High apoC‐III concentration has previously been linked to cardiovascular mortality both in the general population [25] and cohorts preselected by coronary artery disease [41]. Notably, an association between apoC‐III and cardiovascular mortality alone was also observed in our cohort and, hence, our findings add to the previous ones by extending them to cover type 1 diabetes.

A key strength of this research is its large and well‐characterized population, along with the high number of events compared with many other studies in the same field. The availability of wide‐ranging data characterizing DKD (AER, eGFR, DKD baseline category, and DKD progression) enabled a multifaceted study approach. One possible weakness is the lack of direct LDL‐C measurements; however, the formula by Sampson et al. [20] for LDL‐C estimation has appeared more accurate than previous ones—particularly in hypertriglyceridemic samples. Adjusting for apoB in the regression models rendered comparable associations, further supporting the interpretation of precise LDL‐C calculations. Moreover, as with observational studies in general, our analyses cannot conclude whether apoC‐III is driving the endpoints or the endpoints are driving apoC‐III, which should be regarded when interpreting the results of our study.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this study is the first one to suggest that the association between apoC‐III and cardiovascular events is restricted to those with albuminuria among individuals with type 1 diabetes. We also show that apoC‐III predicts DKD progression as well as premature mortality—even after accounting for several established risk factors, including eGFR. New drugs reducing apoC‐III production are on the way to clinical practice. Although the current study does not take a stand on causality, the results cautiously imply that individuals with type 1 diabetes—especially those with albuminuria—could potentially benefit from this new type of therapeutic class.

Conflict of interest

P‐HG has received lecture fees from Astellas, Astra Zeneca, Boehringer‐Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, Elo Water, Genzyme, Medscape, MSD, Mundipharma, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Sanofi, and Sciarc. He is an advisory board member for AbbVie, Astellas, Astra Zeneca, Bayer, Boehringer‐Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Medscape, MSD, Mundipharma, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, and Sanofi. None of these entities participated in the design or interpretation of the study.

Supporting information

Supporting information

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the physicians and nurses at each FinnDiane center (Table S7) participating in the collection of the patient data. We also thank Hanna Olanne (Folkhälsan Research Center, Helsinki, Finland), Heli Krigsman (Folkhälsan Research Center, Helsinki, Finland), and Helinä Perttunen‐Nio (University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland) for their skilled laboratory work. This work was supported by grants from the Folkhälsan Research Foundation; the Wilhelm and Else Stockmann Foundation; the Medical Society of Finland; the Finnish Diabetes Research Foundation; the Liv och Hälsa Society; the Finnish Foundation for Cardiovascular Research; the Waldemar von Frenckell Foundation; the Finnish Kidney Foundation; the Dorothea Olivia, Karl Walter, and Jarl Walter Perklén Foundation; the Academy of Finland (grant numbers 316664 and 299200); the Signe and Ane Gyllenberg Foundation; the Sigrid Juselius Foundation; the Novo Nordisk Foundation (NNF, OC0013659); the Päivikki and Sakari Sohlberg Foundation; and by an EVO governmental grant (TYH2018207).

Jansson Sigfrids F, Stechemesser L, Dahlström EH, Forsblom CM, Harjutsalo V, Weitgasser V, et al. Apolipoprotein C‐III predicts cardiovascular events and mortality in individuals with type 1 diabetes and albuminuria. J Intern Med. 2022;291:338–349.

Fanny Jansson Sigfrids and Lars Stechemesser are co‐first authors.

Contributor Information

Fanny Jansson Sigfrids, Email: fanny.jansson@helsinki.fi.

Per‐Henrik Groop, Email: per-henrik.groop@helsinki.fi.

References

- 1. Harjutsalo V, Forsblom C, Groop P‐H. Time trends in mortality in patients with type 1 diabetes: nationwide population based cohort study. BMJ. 2011;343:d5364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Groop P‐H, Thomas MC, Moran JL, Wadén J, Thorn LM, Mäkinen V‐P, et al. The presence and severity of chronic kidney disease predicts all‐cause mortality in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes. 2009;58:1651–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tolonen N, Forsblom C, Thorn L, Wadén J, Rosengård‐Bärlund M, Saraheimo M, et al. Lipid abnormalities predict progression of renal disease in patients with type 1 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2009;52:2522–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mattock MB, Cronin N, Cavallo‐Perin P, Idzior‐Walus B, Penno G, Bandinelli S, et al. Plasma lipids and urinary albumin excretion rate in type 1 diabetes mellitus: the EURODIAB IDDM Complications Study. Diabet Med. 2001;18:59–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tolonen N, Forsblom C, Mäkinen V‐P, Harjutsalo V, Gordin D, Feodoroff M, et al. Different lipid variables predict incident coronary artery disease in patients with type 1 diabetes with or without diabetic nephropathy: the FinnDiane study. Diabetes Care. 2014;37:2374–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Koivisto VA, Stevens LK, Mattock M, Ebeling P, Muggeo M, Stephenson J, et al. Cardiovascular disease and its risk factors in IDDM in Europe. Diabetes Care. 1996;19:689–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Nordestgaard BG. Triglyceride‐rich lipoproteins and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Circ Res. 2016;118:547–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Borén J, Packard CJ, Taskinen M‐R. The roles of apoC‐III on the metabolism of triglyceride‐rich lipoproteins in humans. Front Endocrinol. 2020;11:474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kawakami A, Aikawa M, Alcaide P, Luscinskas FW, Libby P, Sacks FM. Apolipoprotein CIII induces expression of vascular cell adhesion molecule‐1 in vascular endothelial cells and increases adhesion of monocytic cells. Circulation. 2006;114:681–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zewinger S, Reiser J, Jankowski V, Alansary D, Hahm E, Triem S, et al. Apolipoprotein C3 induces inflammation and organ damage by alternative inflammasome activation. Nat Immunol. 2020;21:30–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jørgensen AB, Frikke‐Schmidt R, Nordestgaard BG, Tybjærg‐Hansen A. Loss‐of‐function mutations in APOC3 and risk of ischemic vascular disease. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:32–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. The TG and HDL Working Group of the Exome Sequencing Project, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute . Loss‐of‐function mutations in APOC3, triglycerides, and coronary disease. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:22–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Caron S, Verrijken A, Mertens I, Samanez CH, Mautino G, Haas JT, et al. Transcriptional activation of apolipoprotein CIII expression by glucose may contribute to diabetic dyslipidemia. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2011;31:513–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Li WW, Dammerman MM, Smith JD, Metzger S, Breslow JL, Leff T. Common genetic variation in the promoter of the human apo CIII gene abolishes regulation by insulin and may contribute to hypertriglyceridemia. J Clin Invest. 1995;96:2601–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Blackett P, Sarale DC, Fesmire J, Harmon J, Weech P, Alaupovic P. Plasma apolipoprotein C‐III levels in children with type I diabetes. South Med J. 1988;81:469–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Juntti‐Berggren L, Refai E, Appelskog I, Andersson M, Imreh G, Dekki N, et al. Apolipoprotein CIII promotes Ca2+‐dependent β cell death in type 1 diabetes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:10090–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kanter JE, Shao B, Kramer F, Barnhart S, Shimizu‐Albergine M, Vaisar T, et al. Increased apolipoprotein C3 drives cardiovascular risk in type 1 diabetes. J Clin Invest. 2019;129:4165–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Klein RL, McHenry MB, Lok KH, Hunter SJ, Le N‐A, Jenkins AJ, et al. Apolipoprotein C‐III protein concentrations and gene polymorphisms in type 1 diabetes: associations with microvascular disease complications in the DCCT/EDIC cohort. J Diabetes Complicat. 2005;19:18–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Thorn LM, Forsblom C, Fagerudd J, Thomas MC, Pettersson‐Fernholm K, Saraheimo M, et al. Metabolic syndrome in type 1 diabetes: association with diabetic nephropathy and glycemic control (the FinnDiane study). Diabetes Care. 2005;28:2019–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sampson M, Ling C, Sun Q, Harb R, Ashmaig M, Warnick R, et al. A new equation for calculation of low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol in patients with normolipidemia and/or hypertriglyceridemia. JAMA Cardiol. 2020;5:540–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Varbo A, Benn M, Tybjærg‐Hansen A, Jørgensen AB, Frikke‐Schmidt R, Nordestgaard BG. Remnant cholesterol as a causal risk factor for ischemic heart disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61:427–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Zhang YL, Castro AF 3rd, Feldman HI, et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:604–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. van Capelleveen JC, Bernelot Moens SJ, Yang X, Kastelein JJP, Wareham NJ, Zwinderman AH, et al. Apolipoprotein C‐III levels and incident coronary artery disease risk: the EPIC‐Norfolk prospective population study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2017;37:1206–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Pechlaner R, Tsimikas S, Yin X, Willeit P, Baig F, Santer P, et al. Very‐low‐density lipoprotein–associated apolipoproteins predict cardiovascular events and are lowered by inhibition of apoC‐III. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69:789–800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Scheffer PG, Teerlink T, Dekker JM, Bos G, Nijpels G, Diamant M, et al. Increased plasma apolipoprotein C‐III concentration independently predicts cardiovascular mortality: the Hoorn Study. Clin Chem. 2008;54:1325–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Basu A, Bebu I, Jenkins AJ, Stoner JA, Zhang Y, Klein RL, et al. Serum apolipoproteins and apolipoprotein‐defined lipoprotein subclasses: a hypothesis‐generating prospective study of cardiovascular events in T1D. J Lipid Res. 2019;60:1432–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Buckner T, Shao B, Eckel RH, Heinecke JW, Bornfeldt KE, Snell‐Bergeon J. Association of apolipoprotein C3 with insulin resistance and coronary artery calcium in patients with type 1 diabetes. J Clin Lipidol. 2021;15:235–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hughes TA, Gaber AO, Amiri HS, Wang X, Elmer DS, Winsett RP, et al. Lipoprotein composition in insulin‐dependent diabetes mellitus with chronic renal failure: effect of kidney and pancreas transplantation. Metabolism. 1994;43:333–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gohda T, Niewczas MA, Ficociello LH, Walker WH, Skupien J, Rosetti F, et al. Circulating TNF receptors 1 and 2 predict stage 3 CKD in type 1 diabetes. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;23:516–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lopes‐Virella MF, Baker NL, Hunt KJ, Cleary PA, Klein R, Virella G. Baseline markers of inflammation are associated with progression to macroalbuminuria in type 1 diabetic subjects. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:2317–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Niewczas MA, Pavkov ME, Skupien J, Smiles A, Md Dom ZI, Wilson JM, et al. A signature of circulating inflammatory proteins and development of end‐stage renal disease in diabetes. Nat Med. 2019;25:805–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Avogaro A, Albiero M, Menegazzo L, de Kreutzenberg S, Fadini GP. Endothelial dysfunction in diabetes: the role of reparatory mechanisms. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:S285–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Stehouwer CD, Lambert J, Donker AJ, van Hinsbergh VW. Endothelial dysfunction and pathogenesis of diabetic angiopathy. Cardiovasc Res. 1997;34:55–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Gimbrone MA, García‐Cardeña G. Endothelial cell dysfunction and the pathobiology of atherosclerosis. Circ Res. 2016;118:620–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kimak E, Solski J, Baranowicz‐Gaszczyk I, Ksiazek A. A long‐term study of dyslipidemia and dyslipoproteinemia in stable post‐renal transplant patients. Ren Fail. 2006;28:483–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kockx M, Glaros E, Leung B, Ng TW, Berbée JF, Deswaerte V, et al. Low‐density lipoprotein receptor‐dependent and low‐density lipoprotein receptor‐independent mechanisms of cyclosporin A‐induced dyslipidemia. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2016;36:1338–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Paik J, Duggan S. Volanesorsen: First Global Approval. Drugs. 2019;79:1349–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Gaudet D, Brisson D, Tremblay K, Alexander VJ, Singleton W, Hughes SG, et al. Targeting APOC3 in the familial chylomicronemia syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:2200–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Digenio A, Dunbar RL, Alexander VJ, Hompesch M, Morrow L, Lee RG, et al. Antisense‐mediated lowering of plasma apolipoprotein C‐III by volanesorsen improves dyslipidemia and insulin sensitivity in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2016;39:1408–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Gaudet D, Alexander VJ, Baker BF, Brisson D, Tremblay K, Singleton W, et al. Antisense Inhibition of Apolipoprotein C‐III in Patients with Hypertriglyceridemia. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:438–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Sacks FM, Alaupovic P, Moye LA, Cole TG, Sussex B, Stampfer MJ, et al. VLDL, apolipoproteins B, CIII, and E, and risk of recurrent coronary events in the cholesterol and recurrent events (CARE) trial. Circulation. 2000;102:1886–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting information