Abstract

Restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) had been used for molecular identification of Sporothrix spp., which is the causative fungi of sporotrichosis and the most prevalent deep‐seated dermatomycosis. Also, mtDNA‐RFLP had been used to investigate the molecular epidemiology of sporotrichosis. While the current standard for molecular diagnosis is performed by sequence analysis of the calmodulin gene (CAL), correspondence between the results from CAL and mtDNA is of diagnostic and epidemiological interest. Here, we investigated the correspondence between CAL and mtDNA used for molecular identification of Sporothrix globosa and S. schenckii, which are two major species. We also investigated and propose molecular markers suitable to describe the epidemiology of S. globosa, which is considered as a species with few intraspecific polymorphisms. Eighty‐seven strains morphologically identified as S. schenckii sensu lato were investigated. They were identified as group A (17 types, 17 strains) or B (14 types, 70 strains) by mtDNA‐RFLP. Partial sequences of CAL, internal transcribed spacer, and spacer between atp9 and cox2 genes of mtDNA of these strains were determined. All group A strains corresponded to S. schenckii, and group B to S. globosa. The sequences of the amplicons targeted on the spacer region in mtDNA of S. globosa ranged 510–515 bp in length and exhibited 10 molecular variations, whereas CAL indicated seven molecular variations. In conclusion, most of the S. schenckii sensu lato strains isolated from Japanese sporotrichosis patients were confirmed as S. globosa, because group B, which comprised the majority of strains, matched perfectly with S. globosa by the CAL sequencing study. We proposed sequence variations in the spacer between atp9 and cox2 genes of mtDNA as a suitable molecular epidemiological marker for S. globosa.

Keywords: calmodulin gene, genotyping, mitochondrial DNA, Sporothrix globosa, Sporothrix schenckii

1. INTRODUCTION

Sporotrichosis is the most predominant and worldwide deep‐seated dermatomycosis. The causative fungi, Sporothrix spp., which inhabits soil, causes lesions when inoculated into skin or subcutaneous tissue by tiny wounds. Sporothrix schenckii had long been regarded as the only species causing sporotrichosis until Marimon et al. 1 , 2 conducted molecular characterization of morphologically identified S. schenckii isolates using several genes including calmodulin (CAL), and proposed a new taxonomy comprising S. schenckii (sensu stricto) with some new species, S. brasiliensis, S. globosa, and S. mexicana. Now, the taxonomy morphologically identified as S. schenckii is understood to be a species complex (S. schenckii sensu lato). Historically, Ishizaki et al. 3 , 4 , 5 investigated genetic polymorphisms between S. schenckii sensu lato strains by restriction enzyme fragment length polymorphisms (RFLP) of mitochondrial (mt)DNA from the late 1980s to early 2000s, and revealed two major groups, A and B, in the species. Later, groups A and B were divided into 17 genotypes and 14 genotypes, respectively, by studies using isolates from many countries in the four continents, Eurasia, the Americas, Africa, and Australia. 6 Although the method using DNA extracted from the mitochondrial fraction recovered from homogenized fungal cells may be considered obsolete, it is still considered the most sensitive method for investigating intraspecific polymorphisms.

Here, we investigated how genotypes defined by RFLP of mtDNA 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 correspond to the latest taxonomy composed of S. schenckii and S. globosa, the latter being the most important causative species of sporotrichosis in Asia including Japan. 7 We examined a partial sequence of mtDNA, where the existence of diversity was predicted in a previous sequence study, 8 to determine whether it may be used for genotyping S. globosa to study the epidemiology of sporotrichosis.

2. METHODS

2.1. Fungal strains

Thirty‐one strains of S. schenckii sensu lato maintained in our department (Table 1) were selected. They were identified as S. schenckii based on their morphological characteristics when they were registered at our department, and their genotypes were determined by RFLP of mtDNA (Mt‐RFLP types). The panel of 31 strains comprised a representative strain of each of 31 Mt‐RFLP types; among them, 17 genotypes were classified as group A and 14 as group B. 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 These isolates originated from Japan, the USA, China, Australia, Argentina, Mexico, Venezuela, Costa Rica, South Africa, and India.

TABLE 1.

Representative strains of each mtDNA RFLP type used in this study

| No. | KMU number | Origin | Mt‐RFLP types a | Mt‐RFLP groups a | GenBank/EMBL/DDBJ accession no. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAL | ITS | Mt‐seq b | |||||

| 1 | 975 | USA | 1 | A | LC635382 | LC636163 | LC635763 |

| 2 | 2286 | Central Japan | 2 | A | LC635383 | LC636164 | LC635764 |

| 3 | 2500 | Central Japan | 3 | A | LC635384 | LC636165 | LC635765 |

| 4 | 2747 | South Japan | 4 | B | LC635385 | LC636166 | LC635766 |

| 5 | 3311 | Central Japan | 5 | B | LC635386 | LC636167 | LC635767 |

| 6 | 2750 | South Japan | 6 | B | LC635387 | LC636168 | LC635768 |

| 7 | 3360 | Central Japan | 7 | B | LC635388 | LC636169 | LC635769 |

| 8 | 2741 | West Japan | 8 | B | LC635389 | LC636170 | LC635770 |

| 9 | 2760 | South Japan | 9 | B | LC635390 | LC636171 | LC635771 |

| 10 | 2763 | South Japan | 10 | B | LC635391 | LC636172 | LC635772 |

| 11 | 2687 | South Africa | 11 | A | LC635392 | LC636173 | LC635773 |

| 12 | 3314 | Central Japan | 12 | B | LC635393 | LC636174 | LC635774 |

| 13 | 2762 | South Japan | 13 | B | LC635394 | LC636175 | LC635775 |

| 14 | 3580 | Costa Rica | 14 | A | LC635395 | LC636176 | LC635776 |

| 15 | 3504 | USA | 15 | A | LC635396 | LC636177 | LC635777 |

| 16 | 3652 | Argentina | 16 | A | LC635397 | LC636178 | LC635778 |

| 17 | 3655 | Argentina | 17 | A | LC635398 | LC636179 | LC635779 |

| 18 | 3617 | Venezuela | 18 | A | LC635399 | LC636180 | LC635780 |

| 19 | 3627 | Venezuela | 19 | A | LC635400 | LC636181 | LC635781 |

| 20 | 3621 | Venezuela | 20 | B | LC635401 | LC636182 | LC635782 |

| 21 | 3912 | Australia | 21 | B | LC635402 | LC636183 | LC635783 |

| 22 | 3492 | USA | 22 | A | LC635403 | LC636184 | LC635784 |

| 23 | 3998 | South Africa | 23 | A | LC635404 | LC636185 | LC635785 |

| 24 | 4303 | China | 24 | B | LC635405 | LC636186 | LC635786 |

| 25 | 4383 | Mexico | 25 | A | LC635406 | LC636187 | LC635787 |

| 26 | 4385 | Mexico | 26 | A | LC635407 | LC636188 | LC635788 |

| 27 | 4386 | Mexico | 27 | B | LC635408 | LC636189 | LC635789 |

| 28 | 4384 | Mexico | 28 | A | LC635409 | LC636190 | LC635790 |

| 29 | 4390 | Mexico | 29 | A | LC635410 | LC636191 | LC635791 |

| 30 | 4398 | Mexico | 31 | A | LC635411 | LC636192 | LC635792 |

| 31 | 4432 | India | 32 | B | LC635412 | LC636193 | LC635793 |

KMU number: registration number in Kanazawa Medical University.

Abbreviations: CAL, calmodulin gene; DDBJ, DNA Data Bank of Japan; EMBL, European Molecular Biology Laboratory; ITS, internal transcribed spacer; mtDNA, mitochondrial DNA; RFLP, restriction fragment length polymorphism.

Mt‐seq: partial sequence of mitochondrial DNA determined by primers 975‐8038F and 975‐9194R.

An additional 56 group B strains isolated from different regions of Japan were included in this study (Table 2). Overall, 17 strains in group A and 70 in group B were investigated.

TABLE 2.

mtDNA RFLP group B (Sporothrix globosa) strains isolated in Japan used in this study

| No. | KMU number | Geographic background of isolates a | Mt‐RFLP types b | GenBank/EMBL/DDBJ accession no | Genotypes | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAL | Mt‐seq c | Cal‐gl d | Mt‐gl e | ||||

| 1 | 2679 | Central | 4 | LC635794 | LC635952 | 1 | 4 |

| 2 | 2688 | West | 4 | LC635795 | LC635953 | 1 | 4 |

| 3 | 2747 | South | 4 | LC635385 | LC635766 | 1 | 4 |

| 4 | 3021 | Central | 4 | LC635796 | LC635954 | 1 | 4 |

| 5 | 3112 | North | 4 | LC635797 | LC635955 | 1 | 4 |

| 6 | 3191 | Central | 4 | LC635798 | LC635956 | 1 | 7 |

| 7 | 3392 | South | 4 | LC635799 | LC635957 | 1 | 4 |

| 8 | 3479 | West | 4 | LC635800 | LC635958 | 1 | 4 |

| 9 | 3877 | West | 4 | LC635801 | LC635959 | 1 | 4 |

| 10 | 4061 | Central | 4 | LC635802 | LC635960 | 1 | 7 |

| 11 | 4078 | Central | 4 | LC635803 | LC635961 | 1 | 4 |

| 12 | 4131 | West | 4 | LC635804 | LC635962 | 1 | 4 |

| 13 | 4193 | Central | 4 | LC635805 | LC635963 | 1 | 7 |

| 14 | 4230 | South | 4 | LC635806 | LC635964 | 1 | 4 |

| 15 | 4257 | West | 4 | LC635807 | LC635965 | 1 | 4 |

| 16 | 4526 | Central | 4 | LC635808 | LC635966 | 1 | 4 |

| 17 | 4670 | South | 4 | LC635809 | LC635967 | 1 | 4 |

| 18 | 6488 | Central | 4 | LC635810 | LC635968 | 1 | 7 |

| 19 | 6799 | South | 4 | LC635811 | LC635969 | 1 | 4 |

| 20 | 2746 | South | 5 | LC635812 | LC635970 | 4 | 1 |

| 21 | 2778 | South | 5 | LC635813 | LC635971 | 5 | 1 |

| 22 | 2824 | North | 5 | LC635814 | LC635972 | 4 | 1 |

| 23 | 3041 | Central | 5 | LC635815 | LC635973 | 5 | 1 |

| 24 | 3308 | North | 5 | LC635816 | LC635974 | 4 | 1 |

| 25 | 3311 | Central | 5 | LC635386 | LC635767 | 1 | 1 |

| 26 | 3341 | Central | 5 | LC635817 | LC635975 | 1 | 1 |

| 27 | 3874 | Central | 5 | LC635818 | LC635976 | 1 | 1 |

| 28 | 4073 | Central | 5 | LC635819 | LC635977 | 4 | 1 |

| 29 | 4244 | West | 5 | LC635820 | LC635978 | 4 | 1 |

| 30 | 4453 | North | 5 | LC635821 | LC635979 | 1 | 1 |

| 31 | 4669 | South | 5 | LC635822 | LC635980 | 1 | 1 |

| 32 | 4710 | Central | 5 | LC635823 | LC635981 | 1 | 1 |

| 33 | 6326 | Central | 5 | LC635824 | LC635982 | 5 | 1 |

| 34 | 6637 | Central | 5 | LC635825 | LC635983 | 4 | 1 |

| 35 | 6705 | Central | 5 | LC635826 | LC635984 | 4 | 1 |

| 36 | 6798 | South | 5 | LC635827 | LC635985 | 1 | 1 |

| 37 | 2750 | South | 6 | LC635387 | LC635768 | 1 | 4 |

| 38 | 3376 | Central | 6 | LC635828 | LC635986 | 1 | 4 |

| 39 | 3515 | Central | 6 | LC635829 | LC635987 | 1 | 2 |

| 40 | 3604 | West | 6 | LC635830 | LC635988 | 1 | 4 |

| 41 | 3693 | West | 6 | LC635831 | LC635989 | 1 | 4 |

| 42 | 3705 | Central | 6 | LC635832 | LC635990 | 1 | 4 |

| 43 | 4130 | West | 6 | LC635833 | LC635991 | 6 | 4 |

| 44 | 4238 | South | 6 | LC635834 | LC635992 | 1 | 7 |

| 45 | 6084 | North | 6 | LC635835 | LC635993 | 1 | 4 |

| 46 | 6429 | West | 6 | LC635836 | LC635994 | 1 | 9 |

| 47 | 2647 | Central | 7 | LC635837 | LC635995 | 5 | 8 |

| 48 | 3360 | Central | 7 | LC635388 | LC635769 | 1 | 2 |

| 49 | 3507 | Central | 7 | LC635838 | LC635996 | 1 | 2 |

| 50 | 4115 | North | 7 | LC635839 | LC635997 | 1 | 2 |

| 51 | 4129 | South | 7 | LC635840 | LC635998 | 1 | 2 |

| 52 | 4256 | West | 7 | LC635841 | LC635999 | 1 | 7 |

| 53 | 4648 | South | 7 | LC635842 | LC636000 | 1 | 2 |

| 54 | 6085 | West | 7 | LC635843 | LC636001 | 1 | 2 |

| 55 | 6684 | South | 7 | LC635844 | LC636002 | 1 | 2 |

| 56 | 6796 | South | 7 | LC635845 | LC636003 | 7 | 8 |

| 57 | 2741 | West | 8 | LC635389 | LC635770 | 1 | 5 |

| 58 | 2736 | West | 9 | LC635846 | LC636004 | 1 | 10 |

| 59 | 2760 | South | 9 | LC635390 | LC635771 | 1 | 4 |

| 60 | 3398 | West | 9 | LC635847 | LC636005 | 1 | 4 |

| 61 | 4132 | West | 9 | LC635848 | LC636006 | 1 | 7 |

| 62 | 4219 | Central | 9 | LC635849 | LC636007 | 1 | 4 |

| 63 | 2763 | South | 10 | LC635391 | LC635772 | 1 | 4 |

| 64 | 3314 | Central | 12 | LC635393 | LC635774 | 1 | 1 |

| 65 | 2762 | South | 13 | LC635394 | LC635775 | 1 | 4 |

KMU number: registration number in Kanazawa Medical University.

Abbreviations: CAL, calmodulin gene; DDBJ, DNA Data Bank of Japan; EMBL, European Molecular Biology Laboratory; mtDNA, mitochondrial DNA; RFLP, restriction fragment length polymorphism.

Geographic background of isolates: the regions of Japan geographically divided into four parts: Central (central Japan; central to eastern Honshu), West (western Japan; Shikoku, western Honshu), South (southern Japan; Kyushu), and North (northern Japan; northern Honshu, Hokkaido).

Mt‐seq: partial sequence of mitochondrial DNA determined by primers 975‐8038F and 975‐9194R.

Cal‐gl: genotypes based on variations of sequence of calmodulin gene.

Mt‐gl: genotypes based on variations of sequence of mitochondrial DNA determined by primers 975‐8038F and 975‐9194R.

2.2. Preparation of template DNA

Fungal DNA was extracted from colonies grown on potato dextrose agar slants or plates, as previously described 9 with slight modification. Briefly, small amounts of mycelial mat rinsed with 70% ethanol were ground in 200 μl of lysis buffer (200 mmol/L Tris‐HCl, pH 7.5, 0.5% sodium dodecylsulfate, 250 mmol/L NaCl, 25 mmol/L ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid). The homogenates were heated at 100°C for 5 min, followed by the addition of 100 μl of 3 mol/L sodium acetate (pH 7.0), centrifuged, and 300 μl of isopropanol was added to the supernatant. The precipitated DNA pellets were washed in 70% ethanol, dried, and dissolved in 100 μl of 10 mmol/L Tris‐HCl (pH 8.0) solution.

2.3. Species identification by CAL and internal transcribed spacer (ITS) of ribosome RNA genes

Partial sequence of CAL was determined with primers CL1 and CL2A, 1 , 2 , 7 and two supplemental primers f1 and r1 designed for 3ʹ‐ and 5ʹ‐ends (Table 3). Sequences near the 3ʹ‐end were determined with primers CL2A and f1 and near the 5ʹ‐end with primers CL1 and r1, respectively. The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) conditions included an initial cycle of 5 min at 94°C, followed by 35 cycles of 50 s at 94°C, 50 s at 55°C, 1 min at 72°C, and a single extension of 7 min at 72°C. 1 , 2 The sequence of ITS of ribosomal RNA gene was determined with primers ITS1 and ITS4 (Table 3) 10 as described. 1 , 2 , 7 If the strains whose nucleotide sequence did not completely match with the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) database (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST/), their conidial shape, assimilation pattern, and limitation of growth temperature were examined for species level identification.

TABLE 3.

Primers used in this study

| Target | Primers | Sequence |

|---|---|---|

| Calmodulin gene, partial 1 | ||

| CL1 | GA(GA)T(AT)CAAGGAGGCCTTCTC | |

| CL2A | TTTTTGCATCATGAGTTGGAC | |

| Near the 3ʹ‐end | f1 | AACAACGGCACCATTGACTT |

| Near the 5ʹ‐end | r1 | GTCGACCTCGTTGATCATGT |

| Internal transcribed spacer 10 | ||

| ITS1 | TCCGTAGGTGAACCTGCGG | |

| ITS4 | TCCTCCGCTTATTGATATGC | |

| Mitochondrial DNA, partial 8 | ||

| 975‐8038F | GCTAGAAATCCTTCTTTAAGAGGAC | |

| 975‐9194R | CCTTCCATTTGAGGTGTAGC | |

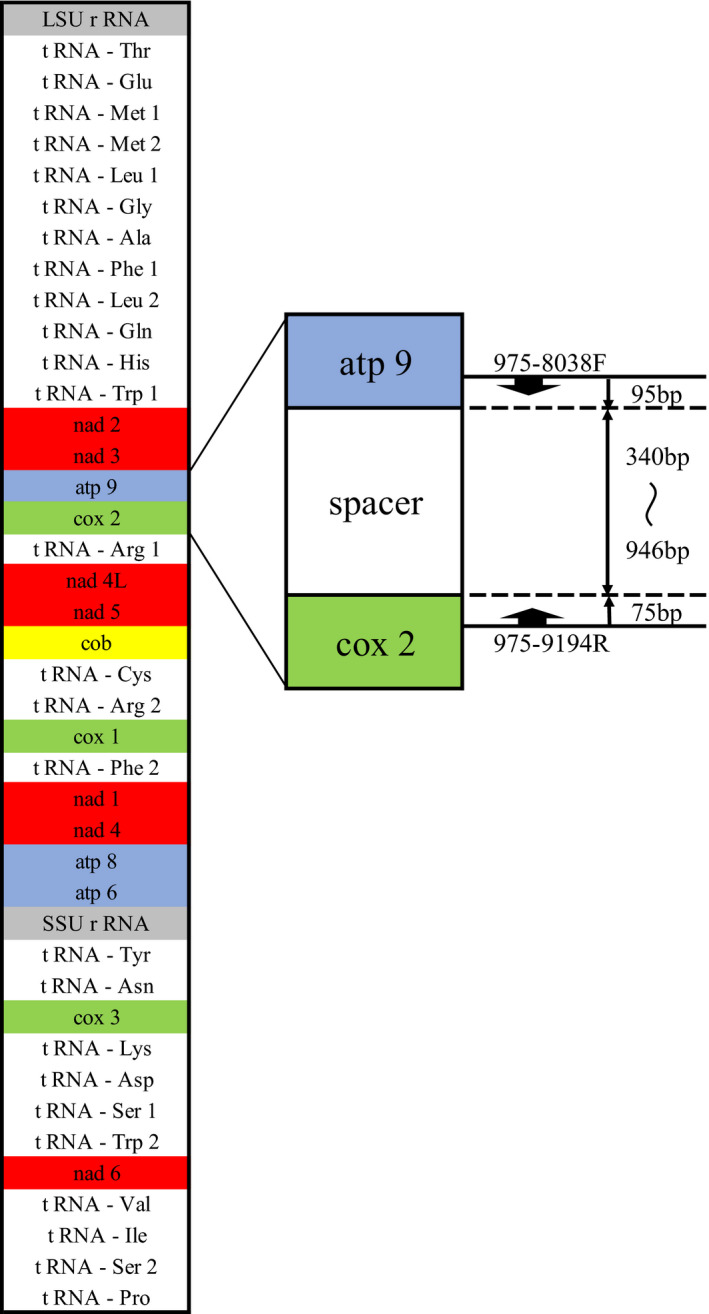

2.4. Genotyping using mtDNA

A primer pair 975‐8038F and 975‐9194R (Table 3) was used for amplification of intergenic spacer region between atp9 and cox2 genes of mtDNA (Figure 1) 8 with the PCR conditions as follows: degeneration at 94°C for 4 min, then 35 cycles of 1 min at 94°C, 2 min at 58°C, and 1.5 min at 72°C. The targeted region revealed the greatest difference between a group A strain (ATCC 10268) and a group B strain (KMU 2052). 8 Amplicons were sequenced and grouped into varieties, and subjected to RFLP with Ase I (New England Biolabs). 8 , 11

FIGURE 1.

Structure of mitochondrial DNA of Sporothrix schenckii sensu lato and target of the primers used in the study

3. RESULTS

3.1. Species identification of the fungal strains based on sequence of CAL

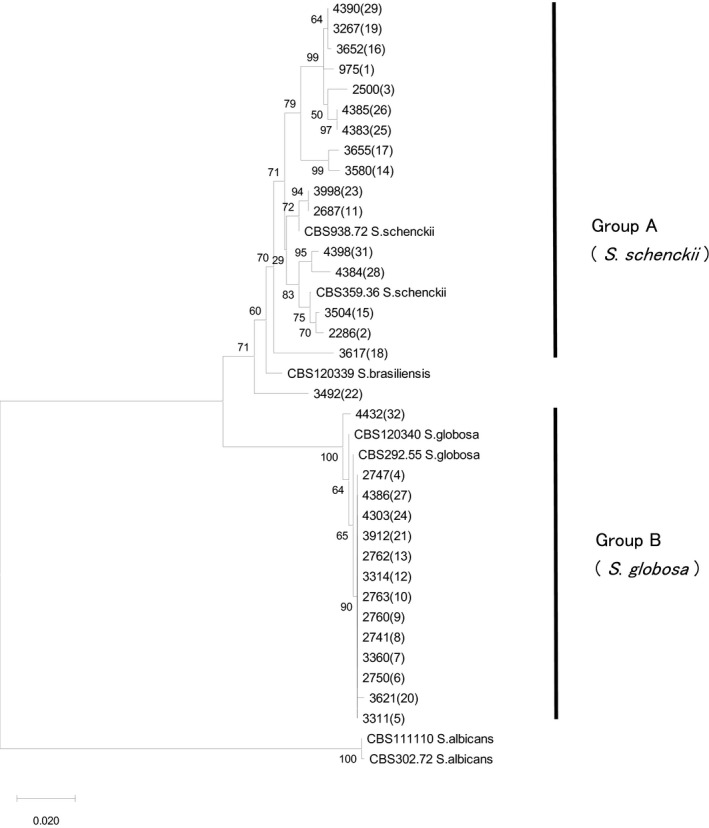

The CAL sequences of 17 strains in group A were 817–822 bp in length, among which 14 were identical to S. schenckii registered in the NCBI database (four strains, i.e., Mt‐RFLP types 19, 25, 26, and 29), or clustered together with the type strain of S. schenckii CBS359.36 (Figure 2). Two of the remaining four strains in group A (Mt‐RFLP types 14 and 17) demonstrated the cluster of S. schenckii in the ITS tree (Figure S1). The other two (Mt‐RFLP types 18 and 22) were identified as S. schenckii by physiological and morphological characters showing positivity for assimilation tests of sucrose and raffinose, growth at 37°C, and sessile pigmented conidia, consistent with those of S. schenckii. Identification of these two strains was consistent with the ITS tree (Figure S1).

FIGURE 2.

Phylogenetic tree of Sporothrix schenckii sensu lato based on partial sequence of calmodulin gene. All 17 strains from each mitochondrial (mt)DNA restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) type in group A were clustered with type strain S. schenckii CBS 359.36, and all 14 in group B with ex‐type strain S. globosa, CBS 120340, respectively. Twelve variations were found among group A strains and three among representative strains in group B. The mtDNA RFLP types are shown in parentheses. Neighbor‐joining method

The CAL sequences of all 14 representative strains in group B were 821–823 bp in length, with the strains clustered in a single branch together with type strain S. globosa CBS292.55 (Figure 2). The additional 56 strains in group B were sequenced. Seven variations were found and named Cal‐gl 1–7 in this study (Table S1).

Consequently, all group A strains corresponded to S. schenckii, and group B to S. globosa. No other species such as S. brasiliensis and S. mexicana were included in the series.

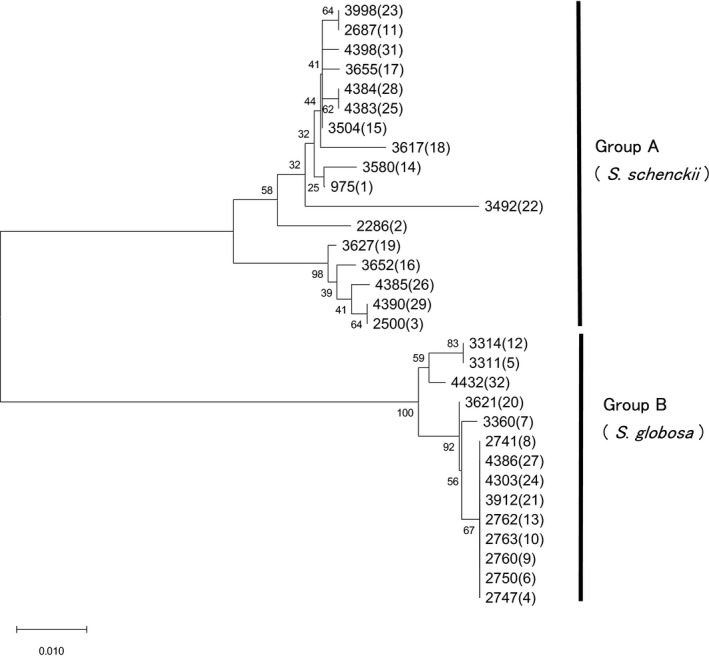

3.2. Genotyping based on sequence of mtDNA

Partial sequence of mtDNA of 17 strains belonging to group A, which corresponds to S. schenckii, and 70 strains of group B, which corresponds to S. globosa, were determined and phylogenetic trees were produced (Figure 3). The topology of each branch on the tree appeared more widely distributed than that on the CAL tree (Figure 2). In detail, the size of the amplicons of 17 strains of group A ranged 513–1116 bp, containing a spacer 343–946 bp in length, comprising 16 variations named Mt‐sch 1–16 in this study. The size of the amplicons of group B strains ranged 510–515 bp, containing a spacer 340–345 bp in length, comprising 10 variations named Mt‐gl 1–10 in this study (Table S2). The match of 70 strains was: Mt‐gl 5, 30 strains; followed by Mt‐gl 1, 18 strains; Mt‐gl 2, eight strains; Mt‐gl 3, five strains; Mt‐gl, three strains; Mt‐gl 6, two strains; and of Mt‐gl 7, Mt‐gl 8, Mt‐gl 9, and Mt‐gl 10, one strain each. The Mt‐gl typing and Mt‐RFLP typing 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 revealed incompatibility. However, only Mt‐gl 1 corresponded exactly to Mt‐RFLP type 5.

FIGURE 3.

Phylogenetic tree of Sporothrix schenckii sensu lato based on partial sequence of mitochondrial (mt)DNA by primers 975‐8038F and 975‐9194R. All 17 strains from each mtDNA restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) type in group A, namely S. schenckii, were clustered together, and all 14 in group B, namely S. globosa, were clustered together, respectively. Fourteen variations were found among group A strains, and five among representative strains in group B. The mtDNA RFLP types are shown in parentheses. Neighbor‐joining method

These sequence variations were examined by RFLP analysis, 5 but only five polymorphisms were detected among S. schenckii strains and none among S. globosa strains (Figure S2). The variations of S. globosa strains could not be detected using commercially available restriction enzymes in silico (data not shown).

4. DISCUSSION

The present study revealed that groups A and B of S. schenckii sensu lato classified by RFLP of mtDNA 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 correspond to S. schenckii and S. globosa, respectively. The molecular epidemiology of 257 strains isolated before 1990 in Japan had comprised 14 group A strains, and 243 group B strains. 4 Therefore, it can be regarded that 14 of 257 strains (5.4%) were S. schenckii, and 243 of 257 (94.6%) S. globosa. A previous molecular epidemiological study using CAL and ITS found nine strains (3.0%) of S. schenckii and 291 (97.0%) of S. globosa among 300 Japanese isolates collected independently. 7 The present study indicated that the major causative species of Japanese sporotrichosis is S. globosa. No causative species other than S. schenckii and S. globosa has been found among Japanese strains so far.

Sporotrichosis has distinctive characteristics and is known as an endemic mycosis, which is widespread. 12 In Japan, sporotrichosis tends to be concentrated in specific regions such as large river basins, but such regions exist in geographically distant locations. In addition, human activities involving contact with wood, plants, moss, and so forth have sometimes been associated with outbreaks of sporotrichosis, 12 , 13 which may affect the epidemiological distribution of Sporothrix spp. Since a case of simultaneous infection in a human by genetically distinct strains was reported, 14 molecular markers that can detect polymorphisms within a species are useful to study epidemiology.

Several molecular markers have been applied to track and monitor sporotrichosis. In particular, S. globosa is known to have low diversity 15 , 16 , 17 and considered to require sensitive markers. Intraspecific polymorphisms of CAL or ITS have been detected in only a few varieties among S. globosa strains. 8 Amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP) analysis, which detects differences in the length of fragments sandwiched between restriction enzyme cleavage sites, divided 225 clinical isolates of S. globosa from China into eight distinct clusters. 15 Multilocus microsatellite analysis is another sensitive method 17 , 18 and microsatellite markers have been reported for genotyping of S. globosa which enabled amalgamation of 120 isolates from China into three distinct clusters. 17 However, peaks for microsatellite markers sometimes shift due to differences in electrophoresis conditions and primer modification processes, and special attention is needed in inter‐laboratory comparison. 19 The most sensitive marker is RFLP analysis of mtDNA, 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 which albeit a non‐PCR‐based complicated and time‐consuming method, found 14 polymorphisms among S. globosa strains. However, the RFLP analysis was sometimes difficult to compare banding profiles and could be confused by bands of similar size or conditions of electrophoresis. In recent days, nucleotide sequence analysis has become easier, and highly variable regions of genes are targeted as molecular markers. As one candidate for this purpose, Kawasaki et al. 8 proposed the intergenic region between atp9 and cox2 genes based on sequence comparison of completely determined mtDNA of KMU975 (group A) and KMU2052 (group B) (Figure 1). Using the primer pair 975‐8038F and 975‐9194R, 10 polymorphisms were detected among 70 strains, which is fewer variations than that of RFLP analysis of whole molecule of mtDNA, yet more sensitive than sequence analysis of CAL which revealed seven variations among these strains. In addition, it is easier to sequence the partial mtDNA gene compared to CAL due to their smaller size. This marker may contribute to understanding the route of transmission of Sporothrix, especially when the source was assumed to be in the environment such as plants and soil, pet animals, or in family onset cases.

We tried to find correspondence of the present Mt‐gl types with the geographic origins of S. globosa. The 65 Japanese strains were isolated from four provinces of Japan: southern Japan (Kyushu), western Japan (Shikoku, western Honshu), central Japan (central to eastern Honshu), and northern Japan (northern Honshu, Hokkaido). However, the strains in each of the four provinces were found to be genetically polymorphic; namely 18 strains from southern Japan comprised five genotypes (Mt‐gl 1, 2, 4, 7, 8), 16 strains from western Japan seven genotypes (Mt‐gl 1–5, 9, 10), 25 from central Japan five genotypes (Mt‐gl 1, 2, 4, 7, 8), and six strains from northern Japan three genotypes (Mt‐gl 1, 2, 4).

Genotype Mt‐gl 4, the most common, was found in 27 among 65 strains, and isolated from all four provinces in Japan. Mt‐gl 4 was also found among isolates from China, Mexico, and Australia, suggesting global distribution. Genotypes Mt‐gl 1 (18 strains), and Mt‐gl 2 (eight strains) were also found in all four Japanese provinces. The proportion of Mt‐gl 1 among genotypes was low in western Japan but high in central‐east Japan. The proportion of Mt‐gl 4 among the isolates was higher in southern and western Japan, and lower in central and northern Japan. However, no particular genotype was responsible for the endemic in Japan. In China, AFLP genotyping was reported to reflect regional differences, 15 but in Japan, many people inhabit relatively small areas and farming was prevalent, so it is postulated that genotypes were affected by human activities. In addition, 18 strains of Mt‐gl 1 isolated from Japan have three types of CAL variations, and combining these markers makes more detailed genotyping of S. globosa possible.

The relationship between genotypes and virulence is of clinical interest. In a few strains belonging to Mt‐gl 1 and Mt‐gl 4, we attempted to find differences in thermotolerance and minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) for some antimycotics, which may influence their pathogenicity (Table S3), but comprehensive studies of a larger number of samples are needed to make any reliable conclusion. We would like to determine the genotype as an attribute of the maintained culture collection for further study.

In conclusion, the present study revealed that groups A and B of S. schenckii sensu lato classified by RFLP of mtDNA 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 corresponded to S. schenckii and S. globosa, respectively. S. globosa is the main pathogen of sporotrichosis in Asia, including Japan, but it is genetically less variable than S. schenckii. For molecular epidemiology, sequence information of the amplicons targeted on the spacer between apt9 and cox2 genes of mtDNA by the primer pair 975‐8038F and 975‐9194R has indicated higher discriminatory power than that of CAL, and we propose to adopt this region for a useful marker for molecular epidemiology of S. globosa.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None declared.

Supporting information

Fig S1

Fig S2

Table S1

Table S2

Table S3

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was partially supported by the Research Program on Emerging and Re‐emerging Infectious Diseases the from Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development, AMED (JP21fk0108094).

Mochizuki H, Anzawa K, Mochizuki T. Genotyping of intraspecies polymorphisms of Sporothrix globosa using partial sequence of mitochondrial DNA. J Dermatol. 2022;49:263–271. 10.1111/1346-8138.16235

REFERENCES

- 1. Marimon R, Gené J, Cano J, Trilles L, Dos Santos Lazéra M, Guarro J. Molecular phylogeny of Sporothrix schenckii . J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44:3251–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Marimon R, Cano J, Gené J, Sutton DA, Kawasaki M, Guarro J. Sporothrix brasiliensis, S. globosa, and S. mexicana, three new Sporothrix species of clinical interest. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45:3198–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Suzuki K, Kawasaki M, Ishjzaki H. Analysis of restriction profiles of mitochondrial DNA from Sporothrix schenckii and related fungi. Mycopathologia. 1988;103:147–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Takeda Y, Kawasaki M, Ishjzaki H. Phylogeny and molecular epidemiology of Sporothrix schenckii in Japan. Mycopathologia. 1991;116:9–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ishizaki H, Kawasaki M, Aoki M, Vismer H, Muir D. Mitochondrial DNA analysis of Sporothrix schenckii in South Africa and Australia. Med Mycol. 2000;38:433–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ishizaki H, Kawasaki M, Anzawa K, Mochizuki T, Chakrabarti A, Ungpakorn R, et al. Mitochondrial DNA analysis of Sporothrix schenckii in India, Thailand, Brazil, Colombia, Guatemala and Mexico. Nippon Ishinkin Gakkai Zasshi. 2009;50:19–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Suzuki R, Yikelamu A, Tanaka R, Igawa K, Yokozeki H, Yaguchi T. Studies in phylogeny, development of rapid identification methods, antifungal susceptibility, and growth rates of clinical strains of Sporothrix schenckii complex in Japan. Med Mycol J. 2016;57:E47–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kawasaki M, Anzawa K, Mochizuki T, Ishizaki H. New strain typing method with Sporothrix schenckii using mitochondrial DNA and polymerase chain reaction restriction fragment length polymorphism (PCR‐RFLP) technique. J Dermatol. 2012;39:362–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Makimura K, Tamura Y, Mochizuki T, Hasegawa A, Tajiri Y, Hanazawa A, et al. Phylogenetic classification and species identification of dermatophyte strains based on DNA sequence of nuclear ribosomal internal transcribed spacer 1 regions. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:920–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. White TJ, Bruns T, Lee S, Taylor J. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. In: Innis MA, Gelfand DH, Sninsky JJ, White TJ, editors. PCR Protocols ‐a Guide to Methods and Application. New York: Academic Press Inc.; 1990. p. 315–22. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Watanabe S, Kawasaki M, Mochizuki T, Ishizaki H. RFLP analysis of the internal transcribed spacer regions of Sporothrix schenckii . Nihon Ishinkin Gakkai Zasshi. 2004;45:165–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chakrabarti A, Bonifaz A, Gutierrez‐Galhardo MC, Mochizuki T, Li S. Global epidemiology of sporotrichosis. Med Mycol. 2015;53:3–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Coles FB, Schuchat A, Hibbs JR, Kondracki FK, Salkin IF, Dixon DM, et al. A multistate outbreak of sporotrichosis associated with sphagnum moss. Am J Epidemiol. 1992;136:475–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kobayashi H, Kawasaki M, Ishizaki H, Fukushiro R, Matsumoto R. A case of sporotrichosis caused by two genetically different Sporothrix schenckii strains. Mycopathologia. 1990;112:19–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zhao L, Cui Y, Zhen Y, Yao L, Shi Y, Song Y, et al. Genetic variation of Sporothrix globosa isolates from diverse geographic and clinical origins in China. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2017;6:e88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Moussa TAA, Kadasa NMS, Al Zahrani HS, Ahmed SA, Feng P, Gerrits van den Ende AHG, et al. Origin and distribution of Sporothrix globosa causing sapronoses in Asia. J Med Microbiol. 2017;66:560–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gong J, Zhang M, Wang Y, Li R, He L, Wan Z, et al. Population structure and genetic diversity of Sporothrix globosa in China according to 10 novel microsatellite loci. J Med Microbiol. 2019;68:248–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Taylor JW, Fisher MC. Fungal multilocus sequence typing ‐ it’s not just for bacteria. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2003;6:351–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Yamada S, Anzawa K, Mochizuki T. Molecular epidemiology of Microsporum canis isolated from Japanese cats, dogs and pet owners by multilocus microsatellite typing fragment analysis. Jpn J Infect Dis (in press). 10.7883/yoken.JJID.2020.809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig S1

Fig S2

Table S1

Table S2

Table S3