Short abstract

Linked Comment: A.W. Lucky and E. Pope. Br J Dermatol 2022; 186:602–603.

Plain language summary available online

1.0 Background

Optimizing outcomes for pregnant women with genetic disease has received increasing attention. 1 Improved early diagnosis and management of genetic disease, together with access to prenatal diagnostics, has meant that more women are reaching reproductive age and are able to make informed choices about pregnancy and childbirth. 2 Despite these advances, the management of pregnancy, childbirth and aftercare in epidermolysis bullosa (EB) has been infrequently evaluated in the literature.

EB encompasses a group of rare, heterogeneous, inherited disorders characterized by skin and variable mucosal fragility. In response to friction or mechanical trauma, the skin layers cleave, resulting in blistering and erosions forming within the skin and mucosae. Four major subtypes are characterized, based on the level of ultrastructural cleavage within the skin: EB simplex (EBS), junctional EB (JEB), dystrophic EB (DEB) and Kindler EB (KEB). 3

Patients with EB have variable disease severity, both within and between subtypes. Patients with mild forms of EBS, for example, may experience a limited impact on daily function and have a normal life expectancy, while patients with severe recessive DEB (RDEB) have significant morbidity and experience life‐limiting complications of their disease. 4

Purpose and scope

This article summarizes recommendations reached following a systematic literature review and expert consensus on the management of pregnancy, birth and postnatal care in women with EB. This guideline is intended to inform and support women with EB and their partners, and aid decision‐making by clinicians managing patients with EB.

Intended guideline users include women with EB and their partners, dermatologists, obstetricians, anaesthetists, neonatologists, paediatricians, nurses, allied health professionals, family practice physicians and psychologists.

Clinical practice guideline aims

To improve the effectiveness and quality of pregnancy and childbirth care for women of reproductive age with EB.

To decrease variation in clinical practice internationally.

To provide evidence‐informed recommendations that will provide measurable standards of care and benchmarks against which practice can be audited.

To highlight quality‐improvement initiatives linked to the clinical practice guidelines (CPG).

Methodology

The CPG development process established three broad clinical questions pertinent to the guideline scope.

A: Preconception and antenatal management

Can preconception and antenatal management advice support a positive pregnancy experience for women living with EB?

B: Labour and management of delivery

What is best practice for maternal assessment and management during labour for women living with EB?

C: Postnatal care and management

Are there specific postnatal care recommendations and interventions to optimize a positive pregnancy experience, including breastfeeding, in women living with EB?

For further information on the CPG methodology, see Appendix S1 (see Supporting Information) with reference to the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP), GRADE and the AGREE II instrument. 5 , 6 , 7 , 8

Results

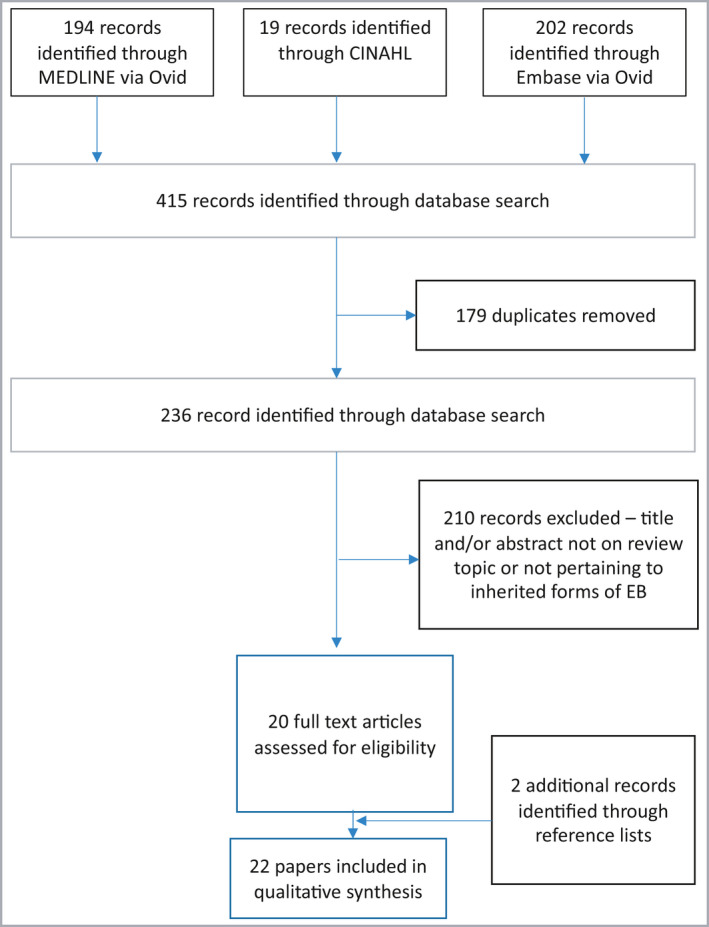

The search identified 415 papers of possible relevance (Figure 1); 22 were included in the appraisal (Table S1; see Supporting Information). The selected articles were then allocated to the three clinical questions and outcomes. The evidence quality overview of the appraised papers can be found in Tables 1 and 2. Additional references relating to other aspects of EB care or obstetric management were added during the iterative process of guideline development from expert consensus.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the systematic review. EB, epidermolysis bullosa.

Table 1.

Overview of evidence (papers appraised)

| Papers appraised | Study type | Antenatal management | Labour/delivery management | PN care + management | Total participants (n)a | No. of offspring | Type of EB in pregnant mother | Age (range) (years) | Mode of delivery | Anaesthesia |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intong 9 ,b | Retrospective | + | + | + | 44 | 112 | EBS (n = 28), JEB (n = 1), DDEB (n = 12), RDEB (n = 3) | 45·1 (22–82)c | NVD (n = 91), CS (n = 21) | ND |

| Price and Katz 11 | CSt | + | + | 1 | 1 | RDEB | 22 | CS | Regional | |

| Bolt 12 | CSt + literature review | + | + | + | 1 | 1 | RDEB | 25 | CS | Regional |

| Boria 18 | CSt | + | + | + | 2 | 3 | RDEB (n = 2) | 32·5 (25–40) | CS (n = 3) | ND |

| Shah 19 | CS | + | + | + | 1 | 1 | EBS | 27 | CS | Regional |

| Bianca 20 | CSt | + | + | + | 1 | 1 | RDEB | NS | CS | Regional |

| Büscher 21 | CSt | + | + | 1 | 2 | RDEB | 24 | NVD (n = 2) | NA | |

| Vendrell 23 | CSt | + | + | + | 0 | 1 | NA | 28 | ND | NA |

| Baloch 29 | CSt | + | + | + | 2 | 2 | RDEB (n = 2) | 31 (29–33) | NVD (n = 1), CS | Regional |

| Choi 39 | CSt | + | + | + | 3 | 10 | JEB (n = 1), RDEB (n = 2) | 36 | NVD (n = 10) | ND |

| Hayashi 40 | CSt | + | + | + | 1 | 1 | KEB | 37 | CS | Regional |

| Ozkaya 41 | CSt | + | + | + | 1 | 1 | DEB | 26 | CS | GA |

| Hanafusa 42 | CR | + | + | + | 3 | 4 | RDEB – generalized other (n = 3) | 26 (21–30) | NVD (n = 4) | NA |

| Sokhal 43 | Conference abstract | + | + | + | 1 | 1 | EB NS | 26 | CS | ND |

| Mallipeddi 44 | Conference abstract | + | + | + | 9 | 12 | EBS (n = 1), DDEB (n = 3), RDEB (n = 4), JEB (n = 1) | ND | NVD (n = 3), CS (n = 9) | ND |

| Diris 45 | CSt | + | 1 | 1 | EBS | 26 | ND | ND | ||

| Araujo 46 | CSt | + | + | 1 | 1 | RDEB | 26 | CS | Regional | |

| Colgrove 48 | CSt + literature review | + | + | + | 1 | 1 | DDEB | 19 | CS | Regional |

| Turmo‐Tejera 49 | CSt | + | 1 | 1 | RDEB | 28 | CS | Regional | ||

| Suru and and Salavastru 50 | Conference abstract | + | + | 1 | 1 | RDEB | 26 | ND | ND | |

| Broster 54 | CSt | + | + | 2 | 2 | EBS (n = 1), DDEB (n = 1) | 23·5 (17–30) | CS (n = 2) | Regional | |

| Berryhill 55 | CSt | + | 1 | 1 | RDEB | 25 | CS | GA |

CR, case report; CS, caesarean section; CSt, case study; DDEB, dominant dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa; EBS, epidermolysis bullosa simplex; GA, general anaesthetic; JEB, junctional epidermolysis bullosa; KEB, Kindler epidermolysis bullosa; NA, not applicable; ND, no data; NS, not specified; NVD, normal vaginal delivery; PN, postnatal; RDEB, recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa. aWomen with epidermolysis bullosa (EB). bIntong et al. 9 also reported on 75 mothers with EB, who gave birth to a total of 174 babies (84 babies affected by EB and 90 not affected). In this cohort, the ratio of delivery modes of EB‐affected babies was NVD : CS 67 : 17 (i.e. 4 : 1). cAge at time of responding to the survey; does not reflect age at childbirth (Intong et al.). 9 The other references reflect maternal age at time of childbirth.

Table 2.

Overview of evidence continued (guideline documents used)

| Guidelines used | Antenatal management | Labour/delivery management | PN care and management | EB‐related guidance | Pregnancy/childbirth‐related guidance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| King et al. (2021) 13 | + | + | |||

| Has et al. (2020) 22 | + | + | |||

| Pillay (2006) 24 ,a | + | + | + | + | |

| WHO (2016) 28 | + | + | |||

| Kramer et al. (2020) 30 | + | + | |||

| RCOG (2016) 36 | + | + | |||

| Hubbard and Jones (2020) 38 | + | + | |||

| NICE (2011) 47 | + | + | |||

| Denyer and Pillay (2012) 53 | + | + | + |

EB, epidermolysis bullosa; NICE, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; PN, postnatal; RCOG, Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists; WHO, World Health Organization. aExpert opinion.

Recommendations

A: Preconception and antenatal management

Pregnancies have been reported in women with all EB subtypes. 9 Fertility is not typically affected in milder forms of EB; however, comorbid medical problems in severe EB subtypes, for example nutritional compromise and low body mass index (BMI), may have an impact on ovulation. 10

As medical supportive care improves and patients transition into adulthood, more women are able to make decisions about starting a family. 11 However, in severe EB subtypes complicated by mucosal fragility (e.g. RDEB, JEB and KEB), vulvovaginal involvement may result in pain during sexual intercourse and, rarely, vaginal stenosis; 12 these factors may impact on sexual function. 13 Use of water‐based lubricants may be helpful for women with vulvovaginal involvement. Vaginal dilators are occasionally prescribed.

R1 ↑↑ Discuss and evaluate vulvovaginal manifestations of EB, where appropriate and dependent on EB subtype, as part of routine care. 14 , 15 , 16 For women with severe vaginal stenosis and dyspareunia, consider referral to an assisted conception unit.

A.1 Access to diagnostics, genetic counselling and prenatal testing

R2 ↑↑ Offer standard preconception care to women with EB, and provide access to genetic counselling where available. 17 , 18 , 19 Depending on the inheritance pattern (autosomal recessive, autosomal dominant) the risk assessment for the pregnancy can be estimated and prenatal testing offered. 11 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 Couples at reproductive risk of severe forms of EB may wish to pursue prenatal or preimplantation genetic testing, accounting for family preferences, religious/cultural beliefs and national regulations. Carrier screening of an unaffected and unrelated partner may be offered according to the individual situation and national regulations, after genetic counselling. 22

A.2 Optimizing health pre‐pregnancy

Optimizing diet and nutrition pre‐pregnancy may improve maternal and perinatal outcomes via effects on BMI or correction of micronutrient deficiencies. 27 , 28

R3 ↑↑ Follow standard preconception care guidelines for women with EB planning a pregnancy. Attention should be given to supplementing folate, managing iron and vitamin D levels, and supplementing zinc and selenium, if needed.

R4 ↑↑ Offer management of severe anaemia, chronic infection, malnutrition and oral health in women with severe EB subtypes. 29 Some patients with EB may be predisposed to gingivitis and oral ulceration. 30 , 31 Hormonal fluctuations in pregnancy may exacerbate gingival disease. 32

A.3 Medication review

Many women with severe subtypes of EB will be established on chronic medication such as analgesia (including opiates) and proton pump inhibitors.

R5 Good practice point (GPP) Review all active prescription and over‐the‐counter medicines and supplements in the context of a woman planning or establishing a pregnancy.

Drugs should only be prescribed in pregnancy if anticipated benefit to the mother with EB outweighs risk to the fetus. Where possible, avoidance of medication during the first trimester is a sensible approach.

A.4 Physiological changes in pregnancy

Important physiological and anatomical adaptations occur during pregnancy, allowing a pregnant woman to meet the metabolic demands of the developing fetus.

With rising levels of human chorionic gonadotropin in early pregnancy, many women suffer from morning sickness or hyperemesis gravidarum. Gastric acidity is increased and oesophageal sphincter tone relaxed, making reflux oesophagitis and heartburn symptoms common throughout pregnancy. 33

This is challenging for patients with EB, who may already suffer with chronic gastro‐oesophageal disease. 34 Vomiting may cause oesophageal blistering and scarring. Furthermore, a bloated sensation and constipation can develop during pregnancy, 35 and may exacerbate pre‐existing gastrointestinal complications of EB.

R6 ↑↑ Monitor and treat pregnancy‐related nausea and vomiting, particularly in women with pre‐existing gastroesophageal reflux disease or known oesophageal strictures. 24

If antisecretory/mucosal protectant prophylaxis is required for reflux management, only agents safe in pregnancy should be offered. 36 (Note the ranitidine recall by the US Food and Drugs Administration and Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency due to the ongoing investigation of a possible contaminant, N‐nitrosodimethylamine. 37 )

R7 ↑↑ Assess and manage constipation in women with EB. Patients may benefit from regular exercise, improved hydration and dietary modification. Iron supplementation may need review. Osmotic laxatives, in particular, may be helpful. 38

R8 ↑↑ Monitor gravid distention of the abdomen for impact on EB wounds. Although skin involvement does not routinely worsen during pregnancy in EB, 9 , 12 , 39 , 40 , 41 there have been occasional reports of wound deterioration related to abdominal distention. 42 , 43 , 44 , 45

A.5 Clinical examination of pregnant women during antenatal visits

R9 ↑↑ Engage the multidisciplinary team (MDT) early during pregnancy for patients with complex forms of EB. Where available, a team consisting of midwife, obstetrician, dermatologist, clinical nurse specialist, anaesthetist, occupational therapist and psychologist will improve pregnancy management. 9 , 19 , 29 , 43 , 46 If an infant with EB is expected, timely involvement of the neonatal team and paediatric EB nurse is needed.

R10 ↑↑ Perform standard antenatal investigations according to local guidelines with the following modifications (Appendix S4; see Supporting Information):

Blood pressure cuffs and tourniquets may usually be applied, taking care to avoid frictional or shearing forces.

Nonadhesive tape should be used, and padding applied under cuffs or tourniquets. 9 , 24 , 46

Ultrasound can be performed safely in a woman with EB. For abdominal ultrasound, ensure generous abdominal lubrication prior to assessment, and attempt gentle pressure. For vaginal ultrasound, the smallest probe should be selected and well lubricated prior to insertion.

R11 ↑↑ Exercise caution during examination when assessing for fundal height, to prevent unintended skin trauma. Lubricant or emollient may need to be applied to gloves and the patient’s skin before examination; a layer of Mepitel® Film may help to protect vulnerable skin. 24 If a speculum or vaginal examination (VE) is required for assessment, generous lubrication should be used.

A.6 Planning delivery, including anaesthetic assessment

R12 GPP Offer pregnant women with EB information to enable informed decision‐making about the mode of childbirth, as part of woman‐centred care. 47 Encourage women with EB to prepare a birth plan.

R13 GPP Provide antenatal care and plan delivery close to the patient’s home wherever possible. This will enable involvement of the patient’s partner, family and carers. The role of the specialist EB team is to advise local obstetric services.

Phenotypic variability both between and within EB subtypes necessitates an individualized approach when considering and planning a woman’s delivery. The EB team caring for the patient will be able to advise about risks to the baby and potential complications associated with each form of EB and how this may impact on labour and/or birth choices.

Having a diagnosis of EB is not a contraindication to vaginal birth. 9 , 12 , 19 In some cases, there may be a strong maternal preference for caesarean section (e.g. owing to fear and anxiety regarding trauma to the birth canal resulting in blistering/wounds); the benefits and risks of all options should be discussed with an obstetrician and dermatologist ideally, and an individualized birth plan agreed.

R14 ↑↑ Vaginal birth should be offered as the preferred mode of delivery for women with all EB subtypes.

R15 ↓↓ Avoid vaginal birth if:

there is a specific ‘routine’ obstetric indication for caesarean section;

there are extensive EB‐related genital blistering/wounds, or vaginal stenosis; 9 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 40 , 48

if a baby is in a breech presentation at term, an external cephalic version is not recommended, owing to shearing force that would be placed on the woman’s abdominal skin; delivery by caesarean section would be recommended.

Vaginal birth does not appear to increase the risk of subsequent vaginal scarring or stenosis, even in patients with severe RDEB. 9 , 42 , 48 There are reports of women with RDEB giving birth to more than one child vaginally, confirming the patency of the vaginal canal postdelivery. 9 , 42

Women with dominantly inherited forms of EB [e.g. EBS or dominant DEB (DDEB)] have a 50% chance of having a baby with EB. Prenatal testing in many such cases is not routinely performed as the conditions are not life limiting. In mothers expecting to deliver a baby with EB, normal vaginal delivery remains the preferred mode of delivery. 9 Antenatal engagement with the neonatal team is critical in these pregnancies.

R16 ↑↑ Arrange an anaesthetic assessment antenatally in women with a known difficult airway, restricted mouth opening or extensive wounds involving the lower back, the latter of which precludes regional anaesthesia. 11 , 21 , 29 , 49 An airway, dental and skin assessment should be undertaken, and anaesthetic plans documented. Planning should involve epidural, spinal and general anaesthetic options (e.g. for emergencies or in the setting of lower back wounds). In women with chronic pain requiring baseline opioids, planning intrapartum analgesia requirements should be undertaken.

A.7 Longer‐term planning

R17 ↑↑ Discuss longer‐term plans for bringing home the newborn as soon as possible antenatally. The antenatal management plan should include:

assessment of maternal hand function and mobility; 39

possible need for physiotherapy assessment;

review of the physical and emotional support network, including partner involvement and proposed plans for looking after the newborn; 50

discussion about breast‐ or bottle‐feeding plans (see ‘Postnatal care and management’ section).

R18 ↑↑ Offer ongoing routine EB skin monitoring and surveillance for skin cancer throughout pregnancy and the postpartum period in patients at greatest risk of EB‐related squamous cell carcinoma. 51

See Table 3 for a summary of the recommendations in pre‐conception/antenatal planning.

Table 3.

Summary of key recommendations: pre‐conception and antenatal management

| No. |

Recommendation |

Strength of recommendation | Level of evidence | Key references a |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| R1 | Discuss and evaluate vulvovaginal manifestations as part of routine care of a female patient with EB, dependent on EB subtype | ↑↑ | Low | ⇨King et al. 13 (Pettit et al., Petersen et al., Singh et al.) 14 , 15 , 16 |

| R2 |

Offer genetic counselling pre‐conception, to women with EB |

↑↑ | Low |

Boria et al., 18 Shah et al., 19 Bianca et al., 20 Büscher et al., 21 Vendrell et al. 23 ⇨Has et al., 22 Pillay 24 (Sybert, 17 Fassihi and McGrath, 25 Pfendner et al.) 26 |

| Offer prenatal testing for couples at reproductive risk of severe forms of EB in line with family preferences and national regulations | ||||

| Consider carrier screening of an unaffected and unrelated partner according to the individual case and national regulations | ||||

| R3 | Standard pre‐conception guidance should be followed for women with EB, including folic acid supplementation and correction of vitamin, mineral and micronutrient deficiencies | ↑↑ | Very low | ⇨WHO 28 , b |

| R4 | Manage anaemia, infection, malnutrition and oral health in women with severe EB subtypes antenatally | ↑↑ | Very low |

Baloch et al. 29 |

| R5 | Review prescription and OTC medicines in a woman planning or establishing a pregnancy | GPP | ⇨WHO 28 , b | |

| R6 | Monitor and treat pregnancy‐related nausea and vomiting in patients with existing gastro‐oesophageal disease or oesophageal strictures | ↑↑ | Very low | |

| R7 | Assess and manage constipation in pregnant women with EB | ↑↑ | Very low | ⇨Hubbard and Jones 38 |

| R8 | Monitor gravid distention of abdomen for impact on EB wounds | ↑↑ | Very low | Intong et al., 9 Bolt et al., 12 Choi et al., 39 Hayashi et al., 40 Ozkaya et al., 41 Hanafusa et al., 42 Sokhal et al., 43 Mallipeddi et al., 44 Diris et al., 45 Araujo et al. 46 |

| R9 | Engage MDT early during pregnancy for women with complex forms of EB | ↑↑ | Very low | Intong et al., 9 Shah et al., 19 Baloch et al., 29 Sokhal et al., 43 Araujo et al. 46 |

| R10 | Perform standard antenatal investigations according to local guidelines with suggested modifications for BP measurement, skin protection and ultrasound | ↑↑ | Very low |

Intong et al., 9 Araujo et al. 46 ⇨Pillay 24 |

| R11 | Examine cautiously to prevent unintended skin or mucosal trauma when assessing for fundal height or performing speculum or VE | ↑↑ | Very low | ⇨Pillay 24 |

| R12 | Offer information to enable women to make informed decisions on mode of childbirth and to prepare a birth plan | GPP | ⇨NICE 47 , b | |

| R13 | Provide antenatal care and plan delivery close to patients home where possible | GPP | ||

| R14 | Offer vaginal birth as preferred mode of delivery for women with all EB subtypes (but see R15) | ↑↑ | Very low | Intong et al., 9 Bolt et al., 12 Shah et al., 19 Hanafusa et al., 42 Colgrove et al. 48 |

| R15 | Avoid vaginal birth if: | ↓↓ | Very low | Intong et al., 9 Boria et al., 18 Shah et al., 19 Bianca et al., 20 Hayashi et al., 40 Colgrove et al. 48 |

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

| R16 | Arrange antenatal anaesthetic preassessment in women with potential airway issues or lower back wounds | ↑↑ | Very low | Price and Katz, 11 Büscher et al., 21 Baloch et al., 29 Turmo‐Tejera et al. 49 |

| R17 | Offer hand function and mobility assessment in preparation for bringing home neonate postdelivery | ↑↑ | Very low | Choi et al. 39 |

| R18 | Offer regular skin cancer surveillance for those at risk during antenatal period | ↑↑ | Very low | Araujo et al. 46 (Lopes et al.) 51 |

Key recommendations are based on the results of the literature review. In addition, references relating to other aspects of EB care or obstetric management were added during the iterative process of guideline development from expert consensus, and the experience of the guideline development group. The recommendations in this table are not arranged according to outcome. Instead, in Tables 3–5 they appear sequentially, in order to guide decision‐making from antenatal to postnatal care, following chronological clinical events. Recommendation strength was strongly influenced by expert panel decision‐making, which accounts for observable gaps between evidence levels and recommendation strength. The evidence level is low/very low for all recommendations. For the strength of recommendation ratings see (Appendix 2). BP, blood pressure; EB, epidermolysis bullosa; GPP, good practice point; MDT, multidisciplinary team; NICE, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; OTC, over‐the‐counter; VE, vaginal examination; WHO, World Health Organization.

Arrows denote a guideline document; articles in parentheses were added from expert consensus.

Reference contained no EB population.

B: Labour and birth

B.1 Advance preparations

R19 ↑ Consider sourcing a ‘dressings pack’ from the EB specialist team for the woman and/or baby. This could include an accessible supply of suitable dressings and silicone medical adhesive remover spray (MARS) during and after labour.

R20 GPP The patient’s handheld notes should include information about EB subtype, delivery plan and contact details for the EB specialist team. These should be accessible in case of an emergency delivery.

B.2 Engagement of neonatal team

R21 ↑↑ Liaise early with the neonatal team if there is a possibility that the baby may be born with EB (e.g. in dominantly inherited forms of EB such as EBS or DDEB, or when prenatal testing results are available). To minimize skin damage, neonates should be handled with extreme care. Vigorous rubbing to stimulate the neonate at delivery should be avoided; if oropharyngeal suction is necessary, small, well‐lubricated catheters should be used. 52

B.3 Monitoring and skincare during labour and delivery

R22 ↑↑ Ensure abdominal examinations are carried out gently, to reduce potential skin damage to the woman; lubricated gloves should be worn. Fetal monitoring equipment such as tight cardiotocography (CTG) belts may cause friction and blistering (see R24). 12 , 19

R23 ↑↑ Ensure lubrication of the speculum and/or gloves when carrying out speculum or VEs. 24 Internal examinations should only be performed when absolutely necessary. 19

R24 ↓↓ Unless the baby is known to be unaffected by EB, avoid fetal scalp electrodes and fetal blood sampling.

B.4 Skincare management during labour and birth

R25 ↑↑ Offer the following skincare adaptations during labour and birth:

staff to be made aware of patient’s skin fragility;

CTG may be used, but skin should be protected beneath the strap with Softban bandaging, cotton padding or a towel; 19 , 24

stirrups, where used, should be well padded;

avoid prolonged pressure/immobility and back rubbing, 24 , 29 as these may lead to blistering and wounds on the lower back, buttocks and arms;

encourage self‐positioning, 29 , 46 mobilizing and independent movement of the patient where possible;

pad the table and ensure a smooth surface;

pad the skin beneath the blood pressure cuff;

remove the adhesive part of electrocardiogram electrodes and secure with silicone tape (see Appendix S4).

B.5 Pressure relief

R26 ↑↑ Offer pressure relief adaptations throughout labour. Frequent position changes will reduce potential pressure damage to the skin. 19 , 29 , 49 Consider use of pressure‐relieving mattresses or pillows (e.g. Repose or international alternative); portable and inflatable options are available for the patient to bring in. To minimize perspiration, the labour room should be kept cool, particularly if the patient is lying on an occlusive surface. Air conditioning or fans may help, but can worsen dryness of the eyes.

B.6 Catheterization

R27 ↓↓ Avoid unnecessary urinary catheterization, which may damage the urethral lining of patients with severe EB subtypes. If needed, the smallest possible silicone urinary catheter should be selected. This should be well lubricated prior to insertion. 24

B.7 Cannulation and securing intravenous lines

Intravenous access may be challenging, particularly in women with more severe EB. 46

R28 GPP If venous access is difficult, offer ultrasound‐guided cannulation, where available. 19 Skin preparation should involve gently dabbing, rather than rubbing, the skin with cleansing solution. 12 , 29 , 49 Cannulas should be secured with low‐adherent film, where available. If sticky film is used, MARS should be used for its removal. 24 , 29 , 53

B.8 Analgesia

R29 ↑↑ Follow the usual obstetric practice for the use of analgesia as required during labour and delivery, with additional considerations for women with EB:

Entonox – apply Vaseline or similar greasy lubricant to the mouthpiece, to avoid frictional damage to lips. 24

Epidural – secure in the usual manner; remove with care using copious MARS.

B.9 Anaesthetic management

Ideally, anaesthetic assessment should take place antenatally for women with complex forms of EB, such as RDEB. 29

R30 ↑↑ If a caesarean section is planned, regional anaesthesia (spinal or epidural) should be offered, where possible. 9 , 19 , 29 , 46 , 49 , 54

R31 ↑↑ Adhere to the following guidance for regional anaesthesia:

Undertake skin preparation with care. Gently dab skin with cleansing fluid and avoid rubbing. Be aware of extensive wounds on the back, which may limit the feasibility of this approach.

Secure drapes with a carefully positioned towel clip. Avoid the use of sticky tape. Never stick drapes to the patient’s skin.

Use of adhesive dressings to secure the epidural safely is acceptable unless suturing is an option. To avoid skin damage, the use of MARS is essential when removing the epidural. 53

Protect the skin on the spine from potential pressure damage caused by epidural catheter by applying a protective dressing to the back underneath the tubing.

Rarely, patients with extensive skin involvement involving the back, precluding neuraxial anaesthesia, may need assessment for general anaesthetic (GA). 55

R32 ↑↑ Adhere to the following guidance if GA is needed:

Oesophageal strictures may increase the risk of regurgitation and aspiration. 29

Airway management may be complex owing to factors such as microstomia, a fixed, scarred tongue, limited neck movement due to contractures, poor dentition and oral blistering. 12 , 29 , 49

Optimal procedural positioning may be difficult owing to musculoskeletal contractures.

Generous lubrication of the lips, airways and laryngoscope blade with soft paraffin is needed to reduce the risk of facial, oropharyngeal and oesophageal blistering. 12 , 29 Avoid direct suction where possible and, ideally, use soft silicone suction devices. If using a laryngeal mask airway, this should be well lubricated and a size smaller than usually chosen. To reduce the risk of mucosal blistering, the cuff should not be fully inflated. To minimize trauma to lips, the tube should be secured with Vaseline gauze. 12

B.10 Inducing labour

R33 ↑ Consider induction of labour if needed, as this is not contraindicated in EB. 21 , 39 Care should be taken to avoid vaginal/perineal trauma when rupturing membranes and/or introducing vaginal pessaries. When carrying out speculum or VE, inserting or removing pessaries, or rupturing membranes, gloves should be well lubricated and the procedure conducted as gently as possible. 24

B.11 Birth setting

R34 Θ Hydrotherapy during labour and water birth may be considered in EB. Although home birth may be feasible, it should not be considered if there is risk of an affected neonate.

B.12 Instrumental delivery

R35 ↓↓ Avoid instrumental delivery, including vacuum suction or forceps‐assisted delivery, where possible, both to minimize skin trauma to the mother’s vulvovaginal surface and perineum, as well as to a potentially affected neonate. 9 , 19 , 24

B.13 Caesarean section

R36 ↑↑ Offer adaptations for caesarean section as follows:

Minimize handling during transfer; avoid rolling or sliding devices.

Consider the use of bipolar diathermy or a harmonic scalpel; if monopolar diathermy is used, a generous application of MARS to remove the adhesive pad is suggested.

Subcuticular sutures acceptable. 19

B.14 Episiotomy and tears

R37 ↑ The decision to undertake episiotomy should be directed by obstetric indication and may be offered in EB. Episiotomies and tears heal well in EB. 9 , 12 , 19 , 39 , 41 , 42 , 56 Stitches should be applied following standard obstetric practice and removed within the recommended timescale.

B.15 Anti‐thromboembolism management

R38 ↓↓Avoid the use of compression stockings as friction caused by their application and removal may damage the skin. 12 , 29

B.16 Mother–infant bonding/skin‐to‐skin

R39 GPP Encourage direct skin‐to‐skin contact where possible.

See Table 4 for a summary of the recommendations for labour/delivery in women with EB.

Table 4.

Summary of key recommendations: labour and management of delivery

| No. |

Recommendation |

Strength of recommendation | Level of evidence | Key references a |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| R19 | Consider providing ‘dressings pack’ for delivery | ↑ | Very low | ⇨Pillay 24 |

| R20 | Include details about EB diagnosis, delivery plan and contact details for EB team in patient’s handheld notes | GPP | ||

| R21 | Engage early with neonatal team if potential birth of affected neonate; adherence to skincare guidelines for newborn | ↑↑ | Very low | Araujo et al. 46 (Gonzalez) 52 |

| R22 | Perform abdominal examination with caution and with generous lubrication | ↑↑ | Very low |

Bolt et al., 12 Shah et al. 19 ⇨Pillay 24 |

| R23 | Perform speculum/vaginal examination if needed with caution and with generous lubrication | ↑↑ | Very low |

Shah et al. 19 ⇨Pillay 24 |

| R24 | Avoid fetal scalp electrodes and fetal blood sampling unless the baby is known to be unaffected by EB | ↓↓ | Very low | ⇨Pillay 24 |

| R25 | Offer skincare adaptations during labour including padding of equipment such as CTG belts and BP cuffs, avoidance of prolonged pressure and exclusive use of nonadhesive tape and dressings | ↑↑ | Low |

Intong et al. 9 Shah et al., 19 Baloch et al., 29 Araujo et al. 46 ⇨Pillay 24 |

| R26 | Offer pressure relief during labour with frequent positional change and use of pressure‐relieving equipment | ↑↑ | Very low | Shah et al., 19 Baloch et al., 29 Turmo‐Tejera et al. 49 |

| R27 | Avoid unnecessary urinary catheterization; if needed, the smallest possible catheter should be selected and well lubricated prior to insertion | ↑↑ | Very low | ⇨Pillay 24 |

| R28 | Offer ultrasound‐guided cannulation where available if venous access difficult | GPP | ||

| R29 | Follow usual obstetric practice for use of analgesia during labour and delivery with modification for Entonox mouthpiece and epidural securing and removal | ↑↑ | Very low | ⇨Pillay 24 |

| R30 | Regional anaesthesia should be offered where possible for CS | ↑↑ | Low | Intong et al., 9 Shah et al., 19 Baloch et al., 29 Araujo et al., 46 Turmo‐Tejera et al., 49 Broster et al. 54 |

| R31 | For regional anaesthesia: | ↑↑ | Very low | |

| ||||

| ||||

| ||||

| Apply dressings under catheter tubing | ||||

| R32 | For general anaesthesia: | ↑↑ | Very low | Bolt et al., 12 Baloch et al., 29 Turmo‐Tejera et al., 49 Berryhill et al. 55 |

| ||||

| ||||

| ||||

| R33 | Induction of labour may be considered | ↑ | Very low | Büscher et al., 21 Choi et al. 39 |

| R34 | Hydrotherapy and water birth may be considered with careful patient selection | Θ | ||

| R35 | Avoid assisted (instrumental) vaginal delivery where possible | ↓↓ | Very low |

Intong et al., 9 Shah et al. 19 ⇨Pillay 24 |

| R36 | Offer adaptations for CS including minimizing handling during patient transfer and considering use of bipolar diathermy or harmonic scalpel | ↑↑ | Very low |

Bianca et al. 20 ⇨Pillay 24 |

| R37 | Offer episiotomies in accordance with obstetric need |

↑↑ |

Very low | Intong et al., 9 Bolt et al., 12 Shah et al., 19 Choi et al., 39 Ozkaya et al., 41 and Hanafusa et al. 42 (Harris et al.) 56 |

| R38 | We strongly recommend against offering anti‐thromboembolic compression hosiery due to frictional skin damage risk |

↓↓ |

Very low | Bolt et al., 12 Baloch et al. 29 |

| R39 | Offer mother–infant bonding (skin‐to‐skin contact) should be encouraged where possible | GPP |

Key recommendations are based on the results of the literature review. In addition, references relating to other aspects of EB care or obstetric management were added during the iterative process of guideline development from expert consensus, and the experience of the guideline development group. The recommendations in this table are not arranged according to outcome. Instead, in Tables 3–5 they appear sequentially, in order to guide decision‐making from antenatal to postnatal care, following chronological clinical events. Recommendation strength was strongly influenced by expert panel decision‐making, which accounts for observable gaps between evidence levels and recommendation strength. The evidence level is low/very low for all recommendations. For the strength of recommendation ratings see (Appendix 2). BP, blood pressure; CS, caesarean section; CTG, cardiotocography; EB, epidermolysis bullosa; GPP, good practice point; MARS, medical adhesive removal spray.

Arrows denote a guideline document; articles in parentheses were added from expert consensus.

C: Postnatal care and management

C.1 Perineal care

R40 ↑↑ Adhere to guidance regarding perineal care:

Nonadherent dressings should be available for women postpartum and included in the dressings pack. 53 Postpartum vaginal discharge (lochia) can last for up to 8 weeks. Advice on soft sanitary wear and skin protection around the groin should be provided.

Both episiotomies and perineal lacerations tend to heal well in women with EB. 9 , 21 , 29 , 39 , 42 , 43

Standard obstetric management (including sutures) of the episiotomy site is recommended. 9 , 21 , 42 , 43

High‐fibre diets, drinking fluids and stool softeners, as needed, should be encouraged until perineal healing is nearly complete. Additional osmotic laxatives may be necessary.

C.2 Care of caesarean section wound

R41 ↑↑Offer nonadherent dressings and MARS for caesarean section wounds. These generally heal well; 9 , 11 , 12 , 19 , 29 , 40 , 41 , 46 , 48 , 56 however, blistering of the scar site has been described. 9 , 20 , 56

C.3 Prevention of venous thrombosis

R42 ↓↓ Avoid compression stockings for women with severe EB due to the unavoidable shearing forces associated with use. 12 , 29 Patients with EB do not appear to be at greater risk for venous thromboembolism during pregnancy/postpartum, compared with other pregnant women. 29 However, in women at high risk of a thromboembolic event, low‐molecular‐weight heparin can be given as per local guidelines. 29

C.4 Infant feeding

R43 GPP Assess factors such as the woman’s EB subtype, social support structures, condition of wounds on breasts or hands, and pain management when supporting a woman in deciding how to feed her baby.

C.5 Support for breastfeeding and breast care

R44 ↑↑

Discuss breastfeeding and/or formula feeding options with the woman antenatally. Some women will have strong intention to breastfeed their newborn, while others may be concerned about possible nipple blistering. Breastfeeding among women with EB has been reported, 9 , 12 , 18 , 24 , 29 , 42 , 44 , 48 , 54 although nipple blistering is common and may limit ongoing efforts. 12 , 29 , 42

Offer to assist with positioning of the baby and adequate latching on to the areola, which may reduce subsequent blistering. Well‐lubricated nipple shields may be useful, 12 , 19 , 24 , 29 and the support of a lactation consultant can be helpful.

C.6 Formula feeding and mixed feeding

R45 ↑↑ Plan support for women with pseudosyndactyly who may need assistance with the preparation of formula. If formula feeding or mixed feeding is chosen, management of infant formula should be included in the postnatal care plan.

C.7 Planning discharge

R46 ↑↑ In general, women with EB do not need longer postnatal hospital admission.

Plan for discharge with the following considerations:

Women may require physical aids, particularly mothers whose hands are affected by scarring or pseudosyndactyly.

Offer engagement with community midwives or health visitors. 12 , 19 , 29

Women should be screened for mood disorders and family/alternative support networks reinforced. Contact with another mother with EB (including online) may be helpful. In the case of delivery of a baby with EB, additional planning is necessary.

See Table 5 for a summary of the recommendations in postnatal care.

Table 5.

Summary of key recommendations: postnatal care and management

| No. |

Recommendation |

Strength of recommendation | Level of evidence | Key reference a |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| R40 | Offer advice on perineal management postdelivery, including: | ↑↑ | Very low | ⇨Hubbard and Jones, 38 Denyer and Pillay 53 |

| ||||

| ||||

| ||||

| R41 | Offer nonadherent dressings and MARS for CS wounds | ↑↑ | Very low | ⇨Pillay 24 |

| R42 | Avoid compression stockings postpartum (if a woman is at risk of VTE, unrelated to their EB, consider LMWH as per local guidance) | ↓↓ | Very low | Bolt et al., 12 Baloch et al. 29 |

| R43 | Offer support to a woman in deciding on infant feeding; account for factors such as EB subtype, social/family support, wound status on breasts and hands, and pain management | GPP | ||

| R44 | Offer to assist with positioning, good latching technique and possible use of nipple shields in a woman wishing to breastfeed | ↑↑ | Very low |

Intong et al., 9 Bolt et al., 12 Boria et al., 18 Baloch et al., 29 Hanufusa et al., 42 Mallipeddi et al., 44 Colgrove et al., 48 Broster et al. 54 ⇨Pillay 24 |

| R45 | Plan support for women with pseudosyndactyly who may need additional assistance and aids | ↑↑ | Very low | Bolt et al., 12 Shah et al., 19 Baloch et al. 29 |

| R46 | Offer comprehensive discharge plans, including: | ↑↑ | Very low | Bolt et al., 12 Shah et al., 19 Baloch et al., 29 Suru and Salavastru 50 |

| ||||

| ||||

| ||||

| ||||

| Liaison and planning with paediatric EB service if neonate has EB |

Key recommendations are based on the results of the literature review. In addition, references relating to other aspects of EB care or obstetric management were added during the iterative process of guideline development from expert consensus, and the experience of the guideline development group. The recommendations in this table are not arranged according to outcome. Instead, in Tables 3–5 they appear sequentially, in order to guide decision‐making from antenatal to postnatal care, following chronological clinical events. Recommendation strength was strongly influenced by expert panel decision‐making, which accounts for observable gaps between evidence levels and recommendation strength. The evidence level is low/very low for all recommendations. For the strength of recommendation ratings see (Appendix S2). CS, caesarean section; EB, epidermolysis bullosa; GPP, good practice point; LMWH, low‐molecular‐weight heparin; MARS, medical adhesive removal spray; VTE, venous thromboembolism.

Arrows denote a guideline document; articles in parentheses were added from expert consensus.

Conclusion

Women with EB should be encouraged in their reproductive choices. With the appropriate genetic counselling, and a planned approach to care, positive pregnancy experiences and outcomes for mothers with EB and their babies can be achieved. Despite the limited evidence base, it is clear that women with EB can have successful pregnancies and deliveries, even in more severe EB subtypes. MDT input is critical to ensuring sustained quality of care.

Future research

Future research should include the establishment of an international registry for pregnant women with EB. Collection of real‐world data on pregnancies and postnatal outcomes in women with EB would better direct future guideline development and more accurately refine advice, stratified according to EB subtype. This would help standardize EB pregnancy management internationally. There is a dearth of information regarding the psychological aspects of maternal and partner health related to family planning, and this should be explored.

Limitations

EB is a rare condition, posing challenges to the conduct of research. Substantial clinical heterogeneity exists between subtypes, limiting the generalizability of advice for different patient groups. Most of the available literature relates to prenatal diagnosis of severe forms of EB, as well as affected neonatal management, but specific guidance on antenatal, intra‐ and postpartum management has not been comprehensively explored. 9 These CPG recommendations are supported largely by low‐level evidence, and therefore we have relied heavily upon expert panel consensus.

Author Contribution

Danielle Talia Greenblatt: Conceptualization (equal); Data curation (equal); Formal analysis (equal); Funding acquisition (equal); Investigation (equal); Methodology (equal); Supervision (equal); Writing‐original draft (lead); Writing‐review & editing (equal). Elizabeth Pillay: Conceptualization (equal); Data curation (equal); Investigation (equal); Writing‐original draft (equal); Writing‐review & editing (equal). Karen Snelson: Conceptualization (equal); Data curation (equal); Investigation (equal); Writing‐original draft (equal); Writing‐review & editing (equal). Rebecca Saad: Investigation (equal); Methodology (equal); Writing‐original draft (equal); Writing‐review & editing (equal). Maurico Torres Pradilla: Conceptualization (equal); Investigation (equal); Methodology (equal); Writing‐original draft (equal); Writing‐review & editing (equal). Suci Widhiati Riza: Conceptualization (equal); Investigation (equal); Writing‐original draft (equal); Writing‐review & editing (equal). Anja Diem: Conceptualization (equal); Investigation (equal); Writing‐review & editing (equal). Caroline Knight: Conceptualization (equal); Writing‐review & editing (equal). Kerry Thompson: Conceptualization (equal); Investigation (equal); Writing‐review & editing (equal). Nina Azzopardi: Conceptualization (equal); Investigation (equal); Writing‐review & editing (equal). Mia Werkentoft: Conceptualization (equal); Investigation (equal); Writing‐review & editing (equal). Zena E. H. Moore: Data curation (equal); Formal analysis (equal); Investigation (equal); Methodology (equal); Writing‐review & editing (equal). Declan Patton: Data curation (equal); Formal analysis (equal); Investigation (equal); Methodology (equal); Writing‐review & editing (equal). Kattya Mayre‐Chilton: Conceptualization (equal); Formal analysis (equal); Funding acquisition (equal); Methodology (equal); Project administration (equal); Writing‐review & editing (equal). Dedee F Murrell: Conceptualization (equal); Data curation (equal); Investigation (equal); Writing‐review & editing (equal). Jemima Mellerio: Conceptualization (equal); Investigation (equal); Supervision (equal); Writing‐original draft (equal); Writing‐review & editing (equal).

Supporting information

Table S1 Appraisal tool.

Appendix S1 Stakeholder involvement and peer review, and methodology.

Appendix S2 Strength of recommendations rating.

Appendix S3 External review panel.

Appendix S4 Clinical procedure guidelines.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Kattya Mayre‐Chilton for invaluable support and guidance in coordinating this guideline. We are grateful to DEBRA International and DEBRA UK for initiating the guideline and providing financial support. We also thank DEBRA Switzerland for hosting the panel in Zermatt during the International DEBRA Congress in 2018, and the EB2020 world congress organizers for hosting our recommendation panel meeting in London.

Funding sources We thank DEBRA UK for funding the development of these guidelines. The views or interests of the funding body have not influenced the final recommendations for clinical practice.

Conflicts of interest With two exceptions (R.S. and K.M.M.‐C.), this panel of researchers has no financial conflicts of interest. R.S. declares a potential conflict from her professional work, which involves research into family experiences of epidermolysis bullosa (EB) in the first 2 years of life. Research topic crossover will occur for the newborn period. R.S. currently works in research and leads the EB Neonatal Clinical Practice Guidelines. K.M.M.C. declares a potential conflict from her professional work coordinating guidelines for DEBRA International. These authors were therefore not involved in the final recommendation editions of the manuscript or postreview panel feedback (Appendix S3; see Supporting Information). All reviewers declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the publication of this guideline.

Data availability The data are openly available in a public repository that issues datasets with DOIs.

Recommendations in these guidelines do not constitute a single approach or standard of medical care. Variations to the recommendations provided may be indicated on an individual, organizational or other basis. Considerable efforts have been made by this panel to ensure content is accurate and up to date. Users of these guidelines are strongly recommended to confirm the accuracy, validity and relevance of all information provided. The authors, DEBRA UK and DEBRA International accept no responsibility for any inaccuracies, information perceived as misleading or the success of any treatment regimen detailed in the guidelines.

The author affiliations can be found in the Appendix.

Plain language summary available online

References

- 1. Chetty S, Norton ME. Obstetric care in women with genetic disorders. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2017; 42:86–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Harris S, Vora NL. Maternal genetic disorders in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am 2018; 45:249–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Has C, Bauer JW, Bodemer C et al. Consensus reclassification of inherited epidermolysis bullosa and other disorders with skin fragility. Br J Dermatol 2020; 183:614–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Has C, Fischer J. Inherited epidermolysis bullosa: new diagnostics and new clinical phenotypes. Exp Dermatol 2019; 28:1146–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. CASP (systematic review) checklist. Available at: https://casp‐uk.net (last accessed October 2020).

- 6. Grade Working Group . The Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE). Available at http://gradeworkinggroup.org (last accessed 28 October 2021).

- 7. Dans AL, Dans LF. Appraising a tool for guideline appraisal (the AGREE II instrument). J Clin Epidemiol 2010; 63:1281–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ormerod ADHJ, Levell NJ, Smith CH, McHenry PM. Updated guidance for writing a British Association of Dermatologists clinical guideline: the adoption of the GRADE methodology. Br J Dermatol 2017; 176:44–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Intong LRA, Choi SD, Shipman A et al. Retrospective evidence on outcomes and experiences of pregnancy and childbirth in epidermolysis bullosa in Australia and New Zealand. Int J Womens Dermatol 2015; 1:26–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Farquhar CM, Bhattacharya S, Repping S et al. Female subfertility. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2019; 5:7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Price T, Katz VL. Obstetrical concerns of epidermolysis bullosa. Obstet Gynecol Surv 1988; 43:445–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bolt LA, O'Sullivan G, Rajasingham D et al. A review of the obstetric management of patients with epidermolysis bullosa. Obstet Med 2010; 3:101–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. King A, Hanley H, Popenhagen M et al. Supporting sexuality for people living with epidermolysis bullosa: clinical practice guidelines. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2021; 16:9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Pettit KA, Elas DE, Stockdale CK. Vulvar exacerbation of epidermolysis bullosa simplex: a case report. J Low Genit Tract Dis 2016; 20:e38–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Petersen CS, Brocks K, Weismann K et al. Pretibial epidermolysis bullosa with vulvar involvement. Acta Derm Venereol 1996; 76:80–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Singh C, Tripathi R, Sardana K et al. Primary amenorrhoea due to a rare cause: epidermolysis bullosa causing haematometra. BMJ Case Rep 2013; 2013:bcr2012007542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sybert VP. Genetic counseling in epidermolysis bullosa. Dermatol Clin 2010; 28:239–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Boria F, Maseda R, Martín‐Cameán M et al. Recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa and pregnancy. Actas Dermosifiliogr 2019; 110:50–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Shah N, Kumaraswami S, Mushi JE. Management of epidermolysis bullosa simplex in pregnancy: a case report. Case Rep Womens Health 2019; 24:e00140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bianca S, Reale A, Ettore G. Pregnancy and cesarean delivery in a patient with dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2003; 110:235–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Büscher U, Wessel J, Anton‐Lamprecht I et al. Pregnancy and delivery in a patient with mutilating dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa (Hallopeau‐Siemens type). Obstet Gynecol 1997; 89:817–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Has C, Liu L, Bolling MC et al. Clinical practice guidelines for laboratory diagnosis of epidermolysis bullosa. Br J Dermatol 2020; 182:574–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Vendrell X, Bautista‐Llácer R, Alberola TM et al. Pregnancy after PGD for recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa inversa: genetics and preimplantation genetics. J Assist Reprod Genet 2011; 28:825–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Pillay E. Care of the woman with EB during pregnancy and childbirth. Available at: https://www.debra.org.uk/downloads/community‐support/care‐of‐a‐woman‐with‐eb‐during‐pregnancy.pdf (last accessed 28 October 2021).

- 25. Fassihi H, McGrath JA. Prenatal diagnosis of epidermolysis bullosa. Dermatol Clin 2010; 28:231–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Pfendner EG, Nakano A, Pulkkinen L et al. Prenatal diagnosis for epidermolysis bullosa: a study of 144 consecutive pregnancies at risk. Prenat Diagn 2003; 23:447–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Stephenson J, Heslehurst N, Hall J et al. Before the beginning: nutrition and lifestyle in the preconception period and its importance for future health. Lancet 2018; 391:1830–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. World Health Organization (WHO) . WHO Recommendations on Antenatal Care for a Positive Pregnancy Experience. Geneva: WHO, 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Baloch MS, Fitzwilliams B, Mellerio J et al. Anaesthetic management of two different modes of delivery in patients with dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa. Int J Obstet Anesth 2008; 17:153–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kramer S, Lucas J, Gamboa F et al. Clinical practice guidelines: oral health care for children and adults living with epidermolysis bullosa. Spec Care Dentist 2020; 40(Suppl. 1):3–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kramer SM. Oral care and dental management for patients with epidermolysis bullosa. Dermatol Clin 2010; 28:303–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ressler‐Maerlender J, Krishna R, Robison V. Oral health during pregnancy: current research. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2005; 14:880–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Practice bulletin summary no. 153: nausea and vomiting of pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 2015; 126:687–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Fine JD, Mellerio JE. Extracutaneous manifestations and complications of inherited epidermolysis bullosa: part I. Epithelial associated tissues. J Am Acad Dermatol 2009; 61:367–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Body C, Christie JA. Gastrointestinal diseases in pregnancy: nausea, vomiting, hyperemesis gravidarum, gastroesophageal reflux disease, constipation, and diarrhea. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 2016; 45:267–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists . The management of nausea and vomiting of pregnancy and hyperemesis gravidarum. Available at: https://www.rcog.org.uk/globalassets/documents/guidelines/green‐top‐guidelines/gtg69‐hyperemesis.pdf (last accessed 28 October 2021).

- 37. Mahase E. Ranitidine: doctors should switch patients to alternative, says health department. BMJ 2019; 367:l6087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hubbard L, Jones R. Preventative nutritional care guideline: constipation management for children and adults with epidermolysis bullosa. Available at: https://www.eb‐clinet.org/fileadmin/user_upload/Media_Library/EB‐CLINET/Dokumente/CPGs/Preventative_Nutritional_Care_Guideline.pdf (last accessed 28 October 2021).

- 39. Choi SD, Kho YC, Rhodes LM et al. Outcomes of 11 pregnancies in three patients with recessive forms of epidermolysis bullosa. Br J Dermatol 2011; 165:700–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hayashi S, Shimoya K, Itami S et al. Pregnancy and delivery with Kindler syndrome. Gynecol Obstet Invest 2007; 64:72–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ozkaya E, Baser E, Akgul G et al. A pregnancy complicated with fetal growth restriction in a patient with dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa. J Obstet Gynaecol 2012; 32:302–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Hanafusa T, Tamai K, Umegaki N et al. The course of pregnancy and childbirth in three mothers with recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa. Clin Exp Dermatol 2012; 37:10–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Sokhal P, Syed S, Phelan L et al. A rare skin disorder and its management during pregnancy: epidermolysis bullosa: a case report and literature review. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2012; 97:A62. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Mallipeddi R, Pillay E, Bewley S et al. Pregnancy in epidermolysis bullosa. Br J Dermatol 2003; 149:51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Diris N, Boralevi F, Lepreux S et al. [Herpetic‐like worsening of an epidermolysis bullosa simplex during pregnancy]. Ann Dermatol Venereol 2003; 130:769–72 (in French). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Araujo M, Bras R, Frada R et al. Caesarean delivery in a pregnant woman with epidermolysis bullosa: anaesthetic challenges. Int J Obstet Anesth 2017; 30:68–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence . Caesarean section. Available at: http://guidance.nice.org.uk/CG132 (last accessed 28 October 2021).

- 48. Colgrove N, Elkattah R, Herrell H. Dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa in pregnancy: a case report of the autosomal dominant subtype and review of the literature. Case Rep Med 2014; 2014:242046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Turmo‐Tejera M, Garcia‐Navia JT, Suarez F et al. Cesarean delivery in a pregnant woman with mutilating recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa. J Clin Anesth 2014; 26:155–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Suru A, Salavastru C. Challenges in epidermolysis bullosa: maximizing pre‐ and perinatal outcomes. Int J Womens Dermatol 2018; 4:244. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Lopes J, Baptista A, Moreira A. Squamous cell carcinoma in a pregnant woman with recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa. Oxf Med Case Reports 2020; 2020:omaa059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Gonzalez ME. Evaluation and treatment of the newborn with epidermolysis bullosa. Semin Perinatol 2013; 37:32–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Denyer J, Pillay E. Best practice guidelines. Skin and wound care in epidermolysis bullosa. Available at: https://www.debra.org.uk/downloads/community‐support/woundcare‐guidelines‐2017.pdf (last accessed 28 October 2021).

- 54. Broster T, Placek R, Eggers GW, Jr . Epidermolysis bullosa: anesthetic management for cesarean section. Anesth Analg 1987; 66:341–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Berryhill RE, Benumof JL, Saidman LJ et al. Anesthetic management of emergency cesarean section in a patient with epidermolysis bullosa dystrophica polydysplastica. Anesth Analg 1978; 57:281–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Harris AG, Saikal SL, Murrell DF. Epidermolysis Bullosa patients' perception of surgical wound and scar healing. Dermatol Surg 2019; 45:280–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1 Appraisal tool.

Appendix S1 Stakeholder involvement and peer review, and methodology.

Appendix S2 Strength of recommendations rating.

Appendix S3 External review panel.

Appendix S4 Clinical procedure guidelines.