Abstract

This article systematically reviewed 34 rigorous evaluation studies of couple relationship education (CRE) programs from 2010 to 2019 that met the criteria for Level 1 well‐established interventions. Significant advances include reaching more diverse and disadvantaged target populations with positive intervention effects on a wider range of outcomes beyond relationship quality, including physical and mental health, coparenting, and even child well‐being, and evidence that high‐risk couples often benefit the most. In addition, considerable progress has been made delivering effective online CRE, increasing services to individuals rather than to couples, and giving greater attention to youth and young adults to teach them principles and skills that may help them form healthy relationships. Ongoing challenges include expanding our understanding of program moderators and change mechanisms, attending to emerging everyday issues facing couples (e.g., healthy breaking ups, long‐distance relationships) and gaining increased institutional support for CRE.

Keywords: couples < populations, diversity < populations, evidence‐based < theory/model, intervention/technique < clinical, practice development < professional/practice issues, review of literature < research

INTRODUCTION

There are many changes in the nature of family formation, dissolution, and committed relationships over the past few decades in the United States and around the world that demand the attention of couple relationship education (CRE) practitioners and researchers (See Markman et al., 2019, for an overview of many of these trends). Despite all the changes, the institution of marriage is still valued by most young people and forming and sustaining a healthy romantic relationship remains an important life goal for most U.S. youth (National Marriage Project, 2019). Even with these aspirations, relationship break‐up and distress are common and associated with a host of negative effects on the emotional and physical well‐being of children, youth, and adults (Baucom et al., 2015; Johnson et al., in press). Accordingly, the need for effective—and up‐to‐date—CRE has only increased over the past 40 years.

Important developments in the CRE field are documented by several valuable reviews (e.g., Markman et al., 2019; Stanley et al., 2020) as well as important meta‐analytic studies (e.g., Hawkins & Erickson, 2015; Hawkins, Hokanson, et al., 2021; Lucier‐Greer & Adler‐Baeder, 2012). These reviews of CRE have documented how participation in educational interventions, on average, helps both advantaged and disadvantaged couples strengthen relationship skills and increase satisfaction, but also pointed out critical gaps in the field and areas of needed improvement. Our current review shows how the field has made significant progress, actively addressing many of these gaps and shortcomings.

The CRE field is dedicated to helping people achieve the dreams they have for a happy, lifetime love by teaching skills and principles to help couples form and sustain healthy relationships. While there is considerable variation in the specific skills and principles addressed in the wide range of curricula used, most research‐based curricula focus on strengthening three general core pillars of relationship health (Stanley et al., 2020): (a) managing negative emotions associated with inevitable conflicts and talking about sensitive issues employing behavioral skills (e.g., time out, speaker‐listener technique); (b) enhancing positive connections (e.g., friendship, sensuality); and (c) strengthening commitment (e.g., prioritizing relationship, seeing the future). CRE is an important couple intervention option to prevent relationship dysfunction and to address common (but often serious) problems that nearly all people encounter. Our focal outcomes are relationship satisfaction, quality, stability, and interaction skills. But as detailed later on, we also include in our review the effects of CRE on individual health (e.g., depression) and family outcomes (i.e., coparenting, child well‐being). Our focus here will be on CRE that attempts to embrace both basic relationship science and rigorous program evaluation. Also, we focus on relationship education delivered to couples rather than to individuals, consistent with the scope of this special issue. CRE exists outside the United States, especially in Western Europe, Great Britain, Australia, and parts of Asia. But this review is dominated by U.S. research because this is where the vast majority of CRE evaluation has been done. Finally, we focus our attention on rigorous randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of CRE programs from 2010 to 2019. The aim of this article was to review these recent RCTs and to classify the current state of the evidence for CRE.

METHOD

Inclusion/exclusion criteria and search procedures

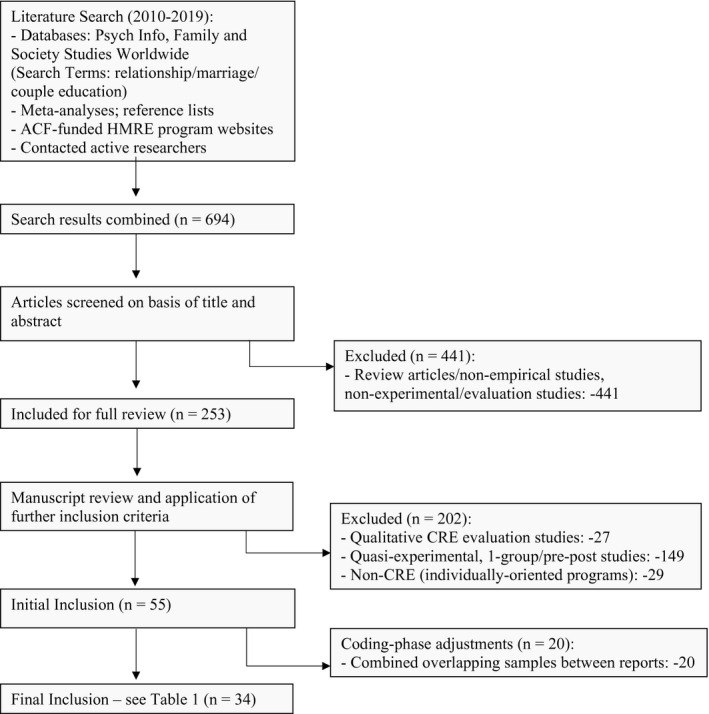

The search process for this systematic review was folded into the search process for two CRE meta‐analytic study projects and included several steps. To identify potential studies, we first searched two electronic databases (PsychINFO; Family & Society Studies Worldwide). We experimented with a range of search terms and combinations of terms, but employing the standard search terms “relationship education,” “marriage education,” and “couple education” proved to be the best starting point because it captured CRE evaluation studies while limiting the number of (more plentiful) correlational studies of couples. For the systematic review, we extracted studies published between January 2010 and December 2019. In addition, we looked at several meta‐analytic studies and conceptual review articles for citations of potential studies. Also, we examined references from studies that met our search criteria for potential studies that may have been missed. During the process, we also contacted active researchers in this field for clarifications about certain studies (e.g., overlapping samples) and asked them if they had any studies (in press or unpublished) that we might have missed. This process produced nearly 700 studies for preliminary review, with 257 studies receiving an extended or full review.

For inclusion in this systematic review, a report had to meet the following criteria: (a) Rigorously reviewed empirical evaluation of a relationship education program. Note that a few studies were final reports of government‐funded studies to the funding agency. Also note that some CRE programs included coparenting, parenting, or fathering content. To include studies of these kinds of hybrid programs, we required that the primary focus of the evaluated program—at least 50% of the curriculum—be on the couple relationship. (b) Quantitative evaluation. We excluded a substantial number of evaluation studies that reported only qualitative data from CRE programs (n = 27). (c) Intervention targeted to adult couples in a relationship. A number of studies evaluated relationship education programs for youth and single young adults, but because the curricula for these programs are substantially different from adult CRE programs (and the studies targeted different outcomes), we excluded them from this systematic review (n = 29). Similarly, some CRE programs allowed individuals in a couple relationship to attend without partners, but the proportion of lone‐attenders was less than one‐third of the sample in all these studies, so all were included. (d) Randomized controlled trial. This criterion excluded a large group (n = 149) of 1‐group/pre‐post studies, quasi‐experimental studies (randomization not assured), and “Superiority” studies (comparing 2+ CRE interventions, with no control group). Figure 1 graphically summarizes the search and inclusion/exclusion decision process.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of search and coding for CRE RCT studies 2010–2019

Ultimately, we reviewed 55 RCT CRE studies. However, in a number of instances, different studies employed the same or substantially overlapping samples. These studies (from similar author teams) reported the same outcomes at later time points or a different set of outcomes. So, we collapsed studies with overlapping‐samples into one “unit of analysis” (n = 20 from 6 different projects). Thus, we reviewed 34 independent studies.

FINDINGS

Overview

The results of our review are presented in Table 1. We summarize these results briefly here. Within the 34 RCT CRE studies between 2010 and 2019, there were 16 distinct CRE programs evaluated. PREP‐based curricula were the most evaluated programs, constituting almost half (n = 17) of all the RCT CRE studies in Table 1. Couple CARE was the next most evaluated program (n = 4). In terms of study designs, about one‐third employed no‐treatment controls, but 11 used wait‐list controls (Many of the studies were conducted in field conditions where program administrators are reluctant to refuse treatment). Seven studies employed some kind of low‐dose active‐treatment control and four studies used alternative‐treatment controls. About a third of the studies (n = 11) had significant proportions of non‐White and lower‐income subjects. Although couple relationship constructs were the most frequent outcomes assessed, many studies also included individual well‐being/health measures (n = 10) and/or co‐parenting/parenting/child measures (n = 11). Nine studies assessed some form of couple aggression/violence. Twenty‐four studies included follow‐up assessments, with half of them longer than 1 year. Nearly all studies found significant treatment effects; only two did not (and 1 study did not report significance tests). Significant findings for key outcomes are short‐handed in the last column of Table 1 (Of course, most studies also reported non‐significant findings, as well; non‐significant outcomes are not listed in the last column of the table).

Table 1.

Efficacy and effectiveness RCT studies of couple relationship education interventions (2010–2019)

| Authors, year (overlapping sample studies) | Study design, conditions/curricula | N | Sample characteristics | Focal outcomes | Assess‐ment points |

Significant results ‐ latest assessment (effect size, if reported) T = treatment group C = control group |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bakhurst et al. (2017) |

|

32 couples |

Age: Men: M = 34.3; Women: M = 32.8; Married: 85% Location: Australia |

Satisfaction; Stability; Communication; Aggression | Pre, Post | None |

|

Barton, Beach, Wells, et al. (2018) (Barton, Beach, Bryant, et al., 2018; Barton et al., 2015, 2017; Beach et al., 2014; Lavner et al., 2019) |

|

346 couples |

Age: Men: M = 39.9; Women: M = 36.6; Race/Ethnicity: 100% AA Married: 63% Location: Southeast USA |

Communication; Satisfaction; Confidence; Coparenting; Parental Monitoring; Youth Exposure to Interparental Conflict | Pre, 9, 17, 25 months |

T > C: satisfaction, communication, confidence, co‐parenting, parental monitoring, youth exposure to interparental conflict (Post‐intervention change in couple functioning predicted coparenting at 25 months) |

| Bodenmann et al. (2014) |

|

330 couples |

Age: Men = M = 41.4; Women M = 40.0 Race: 100% White Married: 71% Location: Switzerland |

Dyadic Coping; Positive Communication; Negative Comm.; Conflict Resolution; Satisfaction | Pre, Post, 3, 6 months |

T1&T2 > C: dyadic coping (women), positive comm., conflict resolution (women), satisfaction (women, men T1 only) T1&T2 < C: negative comm. (women) |

| Bradley et al. (2014) |

|

115 couples |

No demographic information provided Location: not given |

Self‐reported IPV; Observed Propensity toward Violence (Contempt, Belligerence, Domineering, Anger, Defensiveness) | Pre, Post, 9, 15 months | T < C: observed propensity toward violence outcomes (men only) |

| Braithwaite & Fincham (2011) |

|

77 couples | Age: M = 19.92; Race/Ethnicity: 3% AA/10% L‐H Cohabiting: 20% Location: Florida | Satisfaction; Commitment; Communication; Psychological Aggression; Physical Assault; Depression; Anxiety | Pre, 1.5‐ months Post |

T > C: commitment (men), communication T < C: psych. aggression, phys. assault, depression |

| Braithwaite & Fincham (2014) |

|

52 couples | Age: M = 32.36; Race/Ethnicity: 21% AA/7% L‐H Married: 100% Location: Florida | Self‐ and Partner‐reported (SR, PR) Psychological Aggression, Physical Aggression | Pre, Post, 12 months | T < C: PR physical aggression (females), SR physical aggression; PR psych. aggression (female), SR psych. aggression (male) |

|

Buzzella et al. (2012) |

|

12 same‐sex male couples |

Age: M = 44 Race/Ethnicity: Caucasian 90%, Hispanic 5%, Asian 5%. Married: 75% Engaged: 25% Location: Boston area |

Satisfaction; Confidence; Communication; Problem solving; Stress | Pre, Post, 3 months | Significance tests not reported. |

| Carlson et al. (2014) |

|

54 couples |

Age: Men: M = 34.24; Women: M = 33.17 Race/Ethnicity: 14% AA/55% L‐H/7% Asian‐American Married: 100% Location: USA |

Satisfaction | Pre, Post | T > C: satisfaction |

| Cordova et al. (2014) |

|

215 couples |

Age: Women = 45, Men = 47 Race/Ethnicity: 93% W/3% AA/3% Asian American Married: 100% Location: Boston area |

Satisfaction, Emotional Intimacy, Felt Acceptance | Pre, Post, 2, weeks, 6, 12, 12.5, 18, 24 months | T > C: intimacy (d = .36); acceptance (women: d = .23) |

| Cowan et al. (2011) |

|

113 couples |

Age: 37.5 Race/Ethnicity: 84% W/7% AA/7% Asian/2% L‐H/ Married: 100% Location: California Bay Area |

Satisfaction; Communication; Parenting Style; Child Behavior Problems | Pre, Post, 5, 6, 10 years |

T1 > C: satisfaction, communication, behavior problems T2 > C: satisfaction (mothers), communication (mothers) |

| Doss et al. (2016) |

|

300 couples |

Age: M = 36.11 Race/Ethnicity: 17% AA/10% L‐H Married: 80% Location: USA |

Satisfaction; Confidence; Positive/Negative Relationship Quality; Depression; Anxiety; Health; Quality of Life | Pre, Mid‐treatment, Post | T > C: satisfaction (d = .69); confidence (d = .47); neg. rel. quality (d = .57); depression (d = .71); anxiety (d = .94); health (d = .51); life quality (d = .44). |

| Fallahchai et al. (2017) |

|

76 couples |

Age: M = 32.34; Married: 100% Location: Bandar Abbas, Iran |

Satisfaction; Couple Conflict | Pre, Post, 12 months |

T > C: satisfaction T < C: conflict |

| Feinberg et al. (2010) (Feinberg et al., 2014, 2015; Solomeyer et al., 2014) |

|

169 couples | Age: Men: M = 29.8; Women: M = 28.3; Married: 82% Location: Pennsylvania | Couple Relationship; Parenting Stress, Self‐efficacy, Depression; Coparenting; Harsh Parenting; Child Emotional Adjustment; Child Behavior Problems | Pre, 3, 6, 12 months |

T < C: parental stress (d = .16); harsh parenting (d's = .30–.36); child behavioral problems (for families with boys; d's = .62–.81); satisfaction (for families with boys; d = .71) T > C: self‐efficacy (d = .18); coparenting (d = .18) |

| Halford et al. (2010) |

|

71 couples |

Age: Men: M = 31; Women: M = 29 Race/Ethnicity: 90%+ W Married: 70% Location: Brisbane, Australia |

Satisfaction, Self‐regulation; (observed) Negative Communication; Parenting Stress |

Pre, Post, 5, 12 months |

T < C: negative communication T > C: satisfaction, self‐regulation (women), parenting stress (women) |

| Halford et al. (2017) |

|

182 couples |

Age: Men: M = 45, Women = 43 Married: 69% Location: Unspecified |

Satisfaction; Mental Health | Pre, Post, 6, 12, 18, 30, 48 months | None |

| Jones et al. (2018) (Feinberg & Jones, 2018; Feinberg, Jones, Hostetler, et al., 2016; Feinberg, Jones, Roettger, et al., 2016) |

|

399 couples |

Age: Men: M = 31; Women: M = 29 Race/Ethnicity: 85%W Location: Pennsylvania |

Positive/Negative Coparenting; Positive/Negative Parenting; Coparenting Positivity/Negativity; Depression, Anxiety; Child Behavior Problems | Pre, 10, 24 months |

T > C: pos. parenting (d = .18) T < C: neg. coparenting (d = .38), neg. parenting (d = .41), child behavior problems (internalizing; d = .19) |

|

Kalinka et al. (2012) |

|

79 couples |

Age: M = 28 Race/Ethnicity: 84% W/7% L‐H/6% Bi‐racial/3% AA Married: 73%; Location: USA |

Conflict Resolution; Satisfaction | Pre, 1, 2 months | T > C: satisfaction (g = .24), conflict resolution (g = .42) |

| Kröger et al. (2018) |

|

32 militarycouples |

Age: Mid‐ Thirties Race/Ethnicity: 100% W Married: 50% Location: Germany |

Satisfaction; Conflict; Psychological Distress |

Pre, Post, 2 months (no follow‐up for controls) |

T > C: satisfaction, conflict (men) |

| Loew et al. (2012) |

|

32 couples |

Age: M = 44.82; Race/Ethnicity: 89% W; 3% L‐H Married: 100% Location: USA |

Positive Communication/Conflict Management; Negative Communication | Pre, Post | T > C: positive communication/conflict management |

| Lowenstein et al. (2014) (Rhoades, 2015; Williamson et al., 2016) |

Curricula: Within Our Reach; For Our Families, For Our Children; Loving Couples, Loving Children; PREP‐Becoming Parents |

6,298 couples |

Age: M = 31; Race/Ethnicity: 43% L‐H/11% AA/25% W/25% Mixed‐Other; Married: 82%; Location: USA (8 independent sites) |

Relationship Quality, Stability; Positive/Negative Communication; Psychological Abuse; Psychological Distress; Cooperative Co‐parenting |

Pre, 12‐months, 30 months |

T > C: (combined sies) quality (d = .13), coparenting (men; d = .05) T < C: neg. comm (women d = −.12; men d = −.09); abuse (women d = −.07; men d = −.10); distress (women; d = −.09) (Communication gains did not mediate outcome change; WOR program sites ‐ pattern of small treatment effects [Md = .14]) |

| McCormick et al. (2017) |

Curricula: Loving Couples, Loving Children; PREP‐Becoming Parents; PREP‐Within Our Reach; For Our Family, For Our Children |

97 couples | Age: Men: M = 39; Women: M = 38; Race/Ethnicity: 27% AA/26% L‐H Married: 100% Location: USA | Relationship Quality, Conflict; Daily Mood, Stress (diary reports) | Pre, 30 months | T < C: association between negative moods and conflict (for women), association between stress and conflict (for husbands). |

| Markman et al. (2013) |

|

193 couples |

Age: Men: M = 27; Women: M = 25; Race/Ethnicity: Women 84% C/12% L‐H, 2% Men: 87% C/10% L‐H/% Engaged couples Location: USA |

Divorce; Aggression; Negative Communication (observed) | Pre, Post, 8 years (average) |

T > C: divorce among higher initial neg. comm. couples T < C: divorce among lower initial neg. comm. couples (general divorce non‐significant) |

| Moore et al. (2012) (Amato, 2014; Wood et al., 2012; Wood et al., 2014) |

Loving Couples, Loving Children; Love's Cradle; PREP‐Becoming Parents |

5,102 couples |

Age: M = 24; Race/Ethnicity: 52% AA/20% L‐H/12% W/16% Mixed‐Other Married: 7% Cohabiting: 55% Location: USA (8 separate sites) |

Relationship Happiness, Support, Stability; Conflict, Fidelity, Positive Attitudes toward Marriage; Communication; IPV; Coparenting; Parenting Behavior; Child Behavior Problems | Pre, 12, 36 months |

(combined sites) None T > C: stability (OKC site; 49% vs. 41%) (T > C: relationship quality outcomes at 12 months for most disadvantaged couples) |

| Moore et al. (2018) |

Curricula: Within Our Reach; Loving Couples, Loving Children |

1,595 couples |

Age: M = 35; Race/Ethnicity: 78% L‐H/10% AA/12% Other Married: 59% Location: NYC, El Paso |

Relationship Quality, Stability, Commitment; Positive/Negative Communication; IPV; Coparenting; Depression |

Pre, 12 months |

(combined sites) T > C: Stability (d = .11), commitment (d = .12), coparenting (d = .10) T < C: neg. comm. (d = −.07), IPV (d = −.30), depression (women; d = −.14). |

| Petch et al. (2012) |

|

250 couples |

Age: Men: M = 31; Women: M = 29 Married: 65% Location: Australia |

Satisfaction; Negative Communication; Parenting Stress; Intrusive Parenting; IPV | Pre, 4, 16, 28 months |

T < C: neg. comm. (women) T > C: satisfaction (high‐risk women) |

| Pruett et al. (2019) |

|

239 couples |

Age: Fathers M = 32; Mothers M = 29 Race/Ethnicity: 52% L‐H/34% W/8% AA Married: 49%; Romantically Involved 43% Location: California |

Couple Conflict; Parenting Conflict; Parenting Quality; Parenting Stress; Harsh Parenting; Risk for Child Abuse; Child Behavior Problems | Pre, 2, 18 months |

T < C: couple conflict (d = .42) (Decline in couple conflict associated with decreases in harsh parenting, which was associated with fewer child behavior problems) |

|

Rienks et al. (2011) (only coded: FRAME – Couples, not men only, women only) |

|

103 couples | Age: Men: M = 36; Women: M = 31.3; Race/Ethnicity: 34% AA/22% L‐H Married: 70% Cohabiting: 30% Location: Denver, CO area | Adjustment, Satisfaction; Negative Communication.; Coping Efficacy; Anxiety, Depression; Father Involvement; Parenting Alliance | Pre, Post | T > C: father involvement (Greater parental alliance predicted greater father involvement among treatment couples) |

| Roddy et al. (2018) |

|

300 couples |

Age: M = 37.4; Race/Ethnicity: 15% AA/10% L‐H Married: 80% Cohabiting: 14% Location: USA |

Relationship Satisfaction | Pre, Post | T > C: satisfaction (Treatment effect not moderated by pre‐IPV) |

| Rogge et al. (2013) |

|

174 engaged/newly wed couples |

Age: Men: M = 29.3; Women: M = 27.9 Race/Ethnicity: 55% W/21% L‐H/11% AS/5% AA/8% Other Cohabitating: 72% Location: Unspecified |

Relationship Dissolution, Satisfaction | Pre, 2, 6, 12, 24, 36 months | All Ts > C: dissolution (11% vs. 24%) |

|

Stanley et al. (2014) (Allen, Rhoades et al., 2011; Allen, Stanley et al., 2011; Allen et al., 2012; Rhoades et al., 2015) |

|

662 couples |

Age: Men: M = 28.5; Women: M = 27.7 Race/Ethnicity: 70% W/12% L‐H/11% AA/2% NA‐AN/7% Mixed/Other Married: 100% Location: USA |

Divorce; Relationship Quality, Satisfaction; Communication; Confidence; Dedication | Pre, Post, 6, 12, 18, 24 months | T < C: divorce (8% vs. 15%) (effect stronger for minority couples) |

| Trillingsgaard et al. (2016) |

|

233 couples |

Age: Men: M = 39, Women: M = 37 Married: 80% Location: Denmark |

Relationship Satisfaction; | Treatment: Pre, 10, 21, 34, 47, 54 weeks; Control: Pre, 10, 54 weeks | T > C: Satisfaction (d = .48); Responsiveness/Attention (d = .43); Emotional Safety (d = .21) |

| Wadsworth et al. (2011) |

|

173 couples |

Age: Men: M = 34; Women: M = 31 Race/Ethnicity: 33% W/28% AA/24% L‐H/6% AI/10% Mixed/Other Married: 67% Location: Denver, CO |

Financial Worries; Problem Solving; Coping Efficacy Avoidance, Emotional Numbing, Emotional Regulation; Depression | Pre, Post |

T < C: financial worries, avoidance, numbing T > C: regulation, problem solving (women) |

| Whitton et al. (2016) |

|

20 same‐sex male couples |

Age: Men: M = 40; Race/Ethnicity: 83% W/10% AA/3% L‐H Married: 20% Location: Midwest USA |

Satisfaction; Instability; (observed) Positive/Negative Communication; Stress; Social Support | Pre, Post, 3 months |

T > C: satisfaction (d = .18), stability (d = .31), pos. comm. (d = .38), social support (d = .30) T < C: neg. comm. (d = .37), stress (d = .45) |

| Zemp et al. (2016) |

|

150 couples |

Age: Men: M = 39.7; Women: M = 37.4 Location: Switzerland |

Relationship Quality; Parenting; Child Behavior Problems | Pre, Post, 6, 12 months (analyses did not include 6, 12 months follow‐ups) | T1 > C: relationship quality (mothers) (enhanced quality associated with reduced child behavioral problems [mothers]) |

In brief, the vast majority of these rigorous CRE studies find significant program effects on couple relationships, physical and mental health, coparenting, and even child well‐being, although they usually do not find positive effects on all their targeted outcomes. As mentioned above, many studies now target more diverse and disadvantaged populations and most samples now are much larger than in previous decades. Data regularly are analyzed with sophisticated methods (e.g., multi‐level modeling). Many of these studies include longer‐term follow‐up assessments of program effects, with many studies finding effects are maintained, some are diminished but still evident, a few find that effects disappear, and a few are actually strengthened. Early studies of federally funded CRE programs targeted to disadvantaged couples found few significant, long‐term effects. But second‐ and third‐wave studies of these community programs have found a more consistent pattern of small‐to‐moderate positive effects (Hawkins, Hokanson, et al., 2021). Of course, these generalities cover a great deal of variation. And our generally positive assessment of CRE research here should not be taken as a signal that the field has arrived. Later in this article, we point out some important gaps and needed improvements. First, however, we highlight important developments in the field over the last decade.

Extended CRE services to more diverse and disadvantaged couples

Perhaps, the most significant advancement in the CRE field in the United States over the last decade has been a strong—even dominant—practice and research focus on CRE for more diverse and disadvantaged target populations (e.g., Moore et al., 2018; Wood et al., 2014), addressing a limitation noted in earlier critiques (Johnson, 2012). The primary reason for this has been the adoption of CRE as a social policy tool to address family instability among disadvantaged families (Hawkins, Hokanson, et al., 2021). The U.S. federal government (Administration for Children and Families) invested $800 million between 2010–2019 in free community‐based CRE (and RE) programs that served a diverse population of adults (and youth). These efforts have reached an estimated 2.5 million lower‐income people since 2007; 85% of participants were poor or near‐poor and two‐thirds were non‐White. This policy funding also has supported many program evaluation studies (Hawkins, Hokanson, et al., 2021).

One major advance in the past decade then is that CRE programs have included more diverse and more at‐risk, lower‐income couples (Hawkins, Hokanson, et al., 2021) and racially/ethnically diverse participants (especially Hispanic/Latino and African American couples; e.g., Barton et al., 2018), stepfamilies (e.g., Reck et al., 2020), military couples (Stanley et al., 2014), as well as programs tailored for LGBTQ couples (Whitton et al., 2016). A number of implementation studies have documented strategies for recruiting and retaining diverse and disadvantaged couples (e.g., Zaveri & Baumgartner, 2016). In addition, there was a substantial increase in program delivery and evaluation research with unmarried, cohabiting parents (e.g., Wood et al., 2014), many of whom desire more stable and stronger relationships (Halpern‐Meekin, 2019). These relationships are less stable due in part to the increased sociodemographic risks and social inequality that stress unmarried unions (at least in the United States). Some programs targeted to racial/ethnic minorities do address how systematic stresses, inequality, and institutional racism can impact relationships. But the field could be more attentive to these issues (Randles, 2017) and to developing and evaluating culturally sensitive adaptations of programs. Moreover, facilitator training no doubt could do more to sensitize educators to these stresses and even help them identify personal biases that diminish their effectiveness. Also, many of these more vulnerable couples have increased risks owing to rapid relationship development (Sassler et al., 2012) and the formation of inertia for remaining together prior to the development of a mutual commitment to building a future together (Stanley et al., 2020). Such conditions of relationship development likely lead to an increased percentage of relationships where the partners are asymmetrically committed (Stanley et al., 2017). Such dynamics are now becoming more widely considered in the CRE field, which grew from a foundation where mutual, well‐timed commitments to the future were mostly assumed prior to couples seeking CRE services.

This outreach to more diverse and disadvantaged couples brought in larger numbers of distressed couples (Bradford et al., 2015). Thus, there has been a significant increase in research of educational programs serving distressed couples, and the evidence to date shows that distressed (and disadvantaged) couples generally benefit more from CRE than non‐distressed couples (Stanley et al., 2020). Couples with a history of trauma and intimate partner violence (IPV) also are participating in CRE. And some have worried that offering CRE to traumatized couples could be dangerous. The field has given this issue significant and thoughtful attention (Bradley et al., 2014; Roddy et al., 2018; Stanley et al., 2020) and some studies have shown that CRE can reduce IPV (e.g., Braithwaite & Fincham, 2014). Our review indicates no evidence that it increases risk. Many programs now employ protocols for dealing with IPV, including screening for IPV and providing resources and referrals for safety.

Efficient and effective CRE online

An important innovation in the CRE field over the past decade has been experimentation with service delivery, with an emphasis on easier access and more privacy. A small but growing body of work supports the effectiveness of online delivery of evidence‐based CRE (Doss et al., 2019; Halford et al., 2017). In fact, some of the largest effect sizes in programs working with disadvantaged couples have been in studies of online programs (Doss et al., 2020). Many couples in face‐to‐face CRE programs report that they benefit from being with other couples who are experiencing similar problems that help them normalize their challenges (Halpern‐Meekin, 2019); this benefit is diminished in remote online delivery. But Doss and his colleagues (2020) speculate that online programs compensate by enrolling couples who may be especially motivated to work on their relationship because they have proactively initiated help‐seeking through online searches—they are in the “action” stage of behavior change (Prochaska & Norcross, 2001)—rather than responding to recruitment tactics that can lead to enrolling people in services who have only modest motivation to work on their relationship (Carlson et al., 2014). Another advantage of self‐paced online programs is that couples can begin the services right away rather than waiting for the next class to start and can absorb curriculum at their own pace rather than the facilitated group pace. Such programs range in the amount of professional content, from exclusively online with no professional support (Braithwaite & Fincham, 2011), through a few brief support phone call sessions (Doss et al., 2020), to regular sessions of online skills coaching (Halford et al., 2017). Couple attrition rates can be higher in online CRE without professional support (Busby et al., 2015). Future research could explore optimal levels of support for cost‐effective delivery of online CRE.

Extended range of targeted and measured outcomes in CRE programs

Another important development in CRE research has been an increase in the range of outcomes studied. Growing beyond relationship satisfaction and communication skills outcomes that were the focus in earlier studies (Hawkins et al., 2008), many recent studies now include measures of relationship stability (e.g., Moore et al., 2018; Stanley et al., 2014), relationship confidence/commitment/hope (e.g., Hawkins et al., 2017), relationship aggression/violence (e.g., Roddy et al., 2018), individual mental and physical health outcomes (e.g., Barton et al., 2020; Roddy et al., 2020), and child and family functioning, including father involvement (e.g., Cowan & Cowan, 2019). The CRE field has advanced to understand that continuing a relationship is not always the best outcome (Stanley et al., 2020). This broader range of assessment provides a more robust and holistic portrait of couple functioning and individual well‐being and most of these studies report modest positive treatment effects on this expanded range of outcomes. Given trends of deteriorating mental and physical health, and the strong linkages between relationship functioning and adult and child mental and physical health (Markman & Rhoades, 2012), we should welcome the contributions of CRE to improved emotional and physical health.

DISCUSSION: PROGRESS, NEEDED IMPROVEMENTS, AND HOPES FOR FUTURE PROGRESS

As the preceding section documents, the past decade of CRE work has produced noteworthy progress; research over the past decade on the effectiveness of CRE has been strong and growing stronger. If this article was ever made into a movie here is what part of the trailer might say (imagine the voice we associate with trailers): Coming to a community near you, research‐based programs that help you strengthen your relationship, learn to talk without fighting, and protect and preserve your fun, friendship, commitment, and sensuality, while taking a class that will be fun, enjoyable, and entertaining.

All the programs reviewed are based on research and theory from cognitive behavioral and social learning theory perspectives. If we were to classify the accumulated evidence base as a whole, the set of CRE studies presented in Table 1 checks all the boxes for the highest designation using the Southam‐Gerow and Prinstein (2014) framework: Level 1‐Well‐established Interventions. Specifically, the CRE field: (a) serves diverse populations with preventative education, (b) has evaluated the effects of these programs with dozens of rigorous RCT studies employing reliable and valid measurement of relevant outcomes; and (c) have performed appropriate data analyses with adequate statistical power. In addition, most CRE programs were evaluated multiple times, several of them by independent research teams. Finally, the leading curricula have intervention manuals and rigorous facilitator training programs.

But this success should not mask important gaps in the field that will need our attention over the next decade and beyond. In the following section, we highlight a number of important practice and research areas for growth and improvement.

More work on moderators and mechanisms of change

Moderators

Previous reviews (e.g., Wadsworth & Markman, 2012) called for more research on understanding who benefits the most from CRE. In our systematic review of CRE research over the past decade, we explicitly attended to moderators of program effects when they were included in evaluation studies (RCT and non‐RCT), especially initial relationship distress/risk, economic disadvantage, race and ethnicity, and gender. Overall, this body of work suggests that participants who come to CRE programs with greater distress and disadvantage benefit more from such interventions, perhaps because they are motivated for change and have more room to improve. Efforts by program developers over the past 15 years to revise curricula to anticipate the different life experiences of more distressed and disadvantaged participants likely have helped. (For fuller reviews of research on CRE moderators, see Palmer & Hawkins [2019a ] and Stanley et al. [2020 ]).

The range of our explorations for program moderators, however, should expand beyond preexisting personal characteristics. For instance, we could use more exploration of how individual personality characteristics and relational patterns moderate program effects. And we believe broader social factors, including differences within and between countries are ripe for exploration. Halford's research on couples in three different countries is an excellent example of how such comparisons can be accomplished (Halford & van de Vijver, 2020).

Mechanisms of change

Similar to other fields (e.g., Kazdin, 2009), there is a limited amount of work exploring how CRE works. This weakness was identified in a previous review (Wadsworth & Markman, 2012) but we have not made enough progress here. There has been a spattering of attention on change mechanisms that make CRE most effective, including studies that link positive changes in communication skills to positive relationship outcomes consistent with cognitive‐behavioral and social learning theories that undergird the vast majority of CRE programs (e.g., Barton et al., 2017; Hawkins et al., 2017). A few studies do not find this link (e.g., Williamson et al., 2016), and more research is needed. Other studies have focused on intervention processes such as the facilitator alliance and group cohesion (e.g., Ketring et al., 2017; Owen et al., 2013) or couple joint attendance versus just one partner attending alone (e.g., Carlson et al., 2014) (For a review of mediator research, see Palmer & Hawkins, 2019b; Stanley et al., 2020). We need a greater commitment to uncovering the mechanisms of change and test them with experimental designs and rigorous mediator analyses.

More integration of couple education with other family processes

Embracing a more systemic view of couple interventions, many CRE evaluation studies now are assessing the impact on coparenting (Feinberg et al., 2010), parenting (Pruett et al., 2019), and child well‐being outcomes (Cowan et al., 2011; Zemp et al., 2016). A recent meta‐analytic study found evidence of small but significant effects on coparenting and child well‐being (Hawkins, Serrao‐Hill, et al., 2020). Several studies have documented specific pathways from improvements in couple relationships to better coparenting and parenting behavior to children's well‐being (e.g., Barton et al., 2015; Pruett et al., 2019). For many, the ultimate end of CRE efforts is better outcomes for children, not just happier adult relationships.

At the policy level, the overarching goal of government support for CRE programs is to provide a more stable and healthier environment for children. And one of the major motivations for couples seeking help for their relationship is to give their children a better life, especially showing them an example of loving parents who are not fighting with each other (Halpern‐Meekin, 2019). Moreover, as a result of participation in CRE programs, some individuals will identify the need to end the romantic relationship (Stanley et al., 2020) but may also have a need to build a healthy coparenting relationship for the sake of their children. Cowan and Cowan (2019) called for breaking down the silos between couple, coparenting, fathering, and parenting education, while maintaining a strong focus on the couple relationship, and have shown in their own work how valuable such integration can be. We agree that the field needs to offer education to meet a fuller range of presenting needs, perhaps developing adaptations, add‐in modules, or tailoring interventions to the needs of participants experiencing specific family life transitions.

More attention to individually oriented relationship education for youth

Programs for couples have dominated the relationship education field, and that is where our attention has been in this review. Early CRE efforts emphasized preventative efforts such as premarital education to help engaged couples prepare for marriage (e.g., Markman & Floyd, 1980) and enrichment programs for early married couples to keep those relationships strong (Accordino & Guerney, 2003). But the world is different from it was 4 decades ago; union formation is much more complex now and the need for relationship literacy is greater (Clyde et al., 2020). If we wait until contemporary couples form romantic unions, we risk waiting until trajectories of relationship and family formation have already greatly increased risks for unhealthy relationships and family instability. As we move forward, building on pioneering efforts of programs like Love Notes, Connections, and Relationship Smarts, relationship literacy education for youth and young adults should be an important priority for the field. Furthermore, not all adults in a romantic relationship can or want to attend a relationship program with a partner. They too could use help sorting out their relationships, perhaps particularly regarding making decisions to leave unhealthy or unsafe unions (Rhoades & Stanley, 2011).

More attention to missed content

With so many changes over the past 4 decades in relationship dynamics and types, CRE programming may need an update. Earlier, we wrote that most CRE curricula generally focus on three core content areas: managing negative emotions, enhancing positive emotions, and strengthening commitment. But these general content areas do not cover the full range of valuable instruction. We are not aware of published, systematic efforts to match contemporary relationship needs to current CRE curriculum content. One effort (Futris & Adler‐Baeder, 2013) highlights potential missing content in CRE programing (e.g., self‐care, extra‐dyadic support). And questions about missing content are highly salient for some minorities groups. For example, LGBTQ couples and intercultural couples express concern about the misunderstanding of their issues by CRE service providers (Halford & van de Vijver, 2020; Scott & Rhoades, 2014).

Going forward, program developers should consider other important and timely content. For instance, many people are searching the internet for relationship advice. What kind of information are they getting and likely acting on? We doubt that a great deal of the advice is empirically informed, much less leading people to services they may find useful. While working on the article, we conducted an analysis of recent major search engine requests about romantic relationships to explore potential missing content. A little more than half of the searches asked questions about relationship break ups and another 25% dealt with long‐distance romantic relationships. No other topic accounted for more than 5% of inquiries. We doubt that CRE deals much with these topics, though at least one individually oriented program explicitly deals with ending unhealthy relationships or taking a break from the relationship (Pearson et al., 2015). Across the field, we could be better at helping individuals deal with decisions about breaking up and how to do it in more healthy ways. In addition, many people today are trying to manage long‐distance romantic relationships, perhaps as a result of many unions forming through online dating. We could do more to help people better navigate the complexities of distance.

More work on briefer interventions

A legitimate critique of the CRE field is that it has struggled to attract large numbers of couples with intensive, in‐person, multi‐week program formats. Participation barriers have been well known for some time (Markman & Rhoades, 2012) but often are hard to address, including a stigma with seeking relationship help, not wanting to share one's private business in a public setting, syncing schedules to attend with a partner or spouse, and logistical challenges such as transportation and childcare. One solution may be to work toward providing more avenues of relationship education in brief and widely available modalities. Traditional CRE has emphasized learning a lengthy set of principles and skills known to improve relationship quality, but these traditional program offerings require a big commitment of time. Busy, stressed couples find it difficult to give that commitment upfront. We need more exploration of briefer and simpler interventions. For example, brief (2‐session), private relationship check‐up interventions have shown promise in rigorous evaluation work (Cordova et al., 2014; Gordon et al., 2018). Busby and colleagues (2015) found much higher rates of couple agreement to complete brief online CRE (one session) than more extended online CRE (six sessions). Braithwaite and Fincham (2009) have found significant relationship effects with just a brief computer‐based program. Also, the Singapore Family Ministry is offering (and doing an evaluation of) a 2‐hour version of the 8‐hour PREP program (Nazar, Personal Communication, July 2019). One review of 12 brief couple intervention efforts found evidence that they can strengthen relationships (Kanter & Schramm, 2018). But more experimental research is needed that directly compares dosages of the same program and their effects on key outcomes.

Also, there is budding work in offering regular micro‐interventions, such as Marriage Minute (https://www.gottman.com/marriage‐minute/), which involves 1‐minute readings of important relationship principles and nudges for action sent to subscribers twice a week. Similarly, the Singapore Family Ministry will be posting weekly research‐based nuggets that are deconstructed from the PREP program. A variety of types of briefer, evidence‐based micro‐interventions would represent an important area of innovation in the field that could substantially increase reach (Lucier‐Greer et al., 2017). Of course, research is only beginning on these kinds of micro‐interventions and there is reason to be cautious about their effectiveness (e.g., Hatch et al., 2019). Also, it is easy to imagine brief CRE programs for couples dealing with specific issues such as taking on caring responsibilities for aging relatives, managing political differences between partners, or dealing with the stresses of the COVID‐19 pandemic. Recruiting into such offerings may be easier because there is a service offered for meeting a current, concrete need. And when one specific challenge has been addressed, couples may be more likely to seek brief help for the next challenge, amounting to a model of distributing dose across time rather than concentrating it at one point.

More systematic efforts to increase case management, coaching, and use of direct assistance and incentives

One of the most difficult issues faced by community CRE programs is ongoing challenges associated with getting couples to enroll and participate in CRE programs and to decrease program attrition (e.g., Hui, Personal Communication, August 2020). Here we briefly raise two potential solutions, at least for programs with substantial funding. First, case management that involves assigning a staff person to work with the couple throughout the program has been used successfully in some settings and should be expanded and evaluated when employing more intensive interventions. For example, in the MotherWise program (Rhoades, 2018), the person who does the intake serves as the participant's case manager and coach and continues to work with the participant to reinforce the skills learned and help develop links with other community resources. Second, the use of incentives or “direct assistance” has been found to substantially increase participant motivation at all stages of the program (Rhoades, 2018). We believe that program funders should consider including direct assistance in plans for future CRE (and RE) efforts for lower‐income populations.

Dealing with increased participation of distressed couples

As more distressed couples and couples with trauma history are taking advantage of CRE, there is a question of whether clinical training of facilitators would be helpful to strengthen their ability to deal effectively with some of the issues that could surface during relationship education—not to provide clinical services but to be able to identify issues and be sensitive to the need for further help (Bradford et al., 2015; Karam, et al., 2015). Some have been concerned about such recommendations since it could blur core distinctions between CRE and couples therapy (CT) (e.g., Markman & Ritchie, 2015). One core distinction most relevant here is that CRE participants are encouraged not to disclose highly personal relationship issues in the group setting, but save those issues for a private discussion with a coach (if one is available) who is helping them learn a skill. In contrast, personal disclosure is a key part of therapy. Knowing that personal disclosure is not encouraged is likely one of the reasons many participants are attracted to CRE as opposed to therapy and may be one of the reasons distressed couples choose to participate in CRE. However, this is an empirical question that should inspire future research that includes examining generational differences (e.g., Are younger adults less likely to be concerned about disclosure given social media experiences?). Of course, there are other relevant differences between CRE and CT including intervention settings, costs, and the fact that CRE service providers are typically not therapists but are only trained in delivering a specific CRE program. There are, however, obvious overlaps in aspects of approaches and strategies employed in both CRE and CT, including employing common skills that enable them to be active, structured, and reinforcing (Markman & Rhoades, 2012). Nevertheless, most experts recognize the need for facilitators to have better support, training, supervision, and back up for handling things well and staying on task. The level and kind of training for CRE facilitators is an important evolving issue and will benefit from continued discussion and research in the field.

Continuing efforts to reach lower income couples

Efforts to reach more diverse, especially low‐income couples have required some thoughtful curriculum development and adaptation, although the core skills and principles remain (e.g., Rhoades & Stanley, 2011). Importantly, we believe that extending the reach of no‐cost CRE to more diverse and disadvantaged couples—who often need these services the most—is consistent with a burgeoning social justice agenda in the United States. In saying this, we acknowledge healthy, ongoing debates among scholars and policy observers about the merits and wisdom of a policy to use public funding to help increase family stability with these kinds of “soft skills” educational programs (Randles, 2017) or whether a focus on behavioral skills can produce sustained improvements in these stressed couple relationships (e.g., Johnson, 2012; Karney & Bradbury, 2020). We anticipate that the next decade of research will bring even greater clarity to these important issues.

Continue more use of online CRE

Online CRE programs offer advantages in outreach and efficiency that the field needs if it wants to move beyond a limited‐access service to a public health service that meets a widespread need. The recent COVID‐19 pandemic strongly impacted the CRE field (Lutui & Hawkins, 2021). For instance, before the pandemic almost all federally supported CRE programs were delivered face‐to‐face. But by May 2020, program administrators shifted to varying forms of online delivery. For similar reasons, the U.S. Armed Forces shifted to the use of both a self‐directed, online version of PREP (ePREP) and to virtual workshops. For many programs, the training of facilitators also has moved online, with a growing component of the training covering how to lead virtual workshops effectively. Co‐author Halford is a director at Relationships Australia (Queensland) that during the pandemic moved almost exclusively to online and video delivery of what had been face‐to‐face couple and family services. Given the effects and popularity of these services, going forward they plan to discuss with clients the choice of what service delivery mode might work best for them, including the use of video, telephone, and online delivery. This innovative “omni‐channel delivery” approach provides clients at various stages of family development the ability to access services at various intensity levels using a variety of methods of which face‐to‐face is just one option.

We believe these shifts will have a lasting impact on the field. Having invested enormous amounts of work to transfer programs online as a result of the pandemic, practitioners will be more likely to make use of online services in the future. We have already heard from administrators that they believe they are reaching some people in their communities who they would never reach if they continued to require them to come to their meeting places (Lutui & Hawkins, 2021). Post‐pandemic, we anticipate CRE programs could use both face‐to‐face and online delivery in the same program (e.g., Petch et al., 2012) and some services might offer online options to start and then offer more with face‐to‐face sessions, or vice versa. Online programming also may facilitate more tailoring of content to meet unique client needs (Baucom et al., 2015). With so much recent work to transfer programs online, practitioners will be more likely to provide both online (synchronous and asynchronous) as well as in‐person services.

More strategizing to sustain CRE programming

Finally, we worry about how to keep successful evidence‐based CRE programs serving more disadvantaged populations going if/when public funding dries up. For example, we know of several community agencies that were funded with early U.S. federal dollars to deliver CRE to disadvantaged couples for a 5‐year grant cycle that did not get refunded and their CRE efforts disappeared. While the federal policy initiative has been a boon for CRE in the United States, long‐term funding is always a question. Current legislators are a generation removed from the original TANF legislation that sparked the policy innovation. We anticipate that federal welfare policy at some point over the next decade will undergo another major revision. Whether CRE funding will be continued remains unknown, but political and fiscal realities may outweigh the emerging, mixed evidence base of this social policy.

Accordingly, we believe there is a need to diversify institutional support for CRE. For instance, state governments could set aside a small proportion of block‐grant TANF funds for programs to help couples form and sustain healthy relationships. Federal policymakers could think about creative mechanisms for incenting state efforts. In addition, 10 U.S. states have provided financial incentives in the form of marriage license discounts to couples who participate in premarital education, although these state policies have not translated into reduced divorce rates perhaps due to poor implementation (Clyde et al., 2020). States could consider using a part of marriage license fees to support CRE efforts.

We think that local communities, too, can organize to promote and offer CRE services. Community marriage initiatives in Chattanooga TN (First Things First) and in Jacksonville FL (Live the Life) have shown how community organizing efforts can promote availability and participation in CRE, and one quasi‐experimental study of the Jacksonville initiative reported significantly larger declines in the local divorce rate over a 3‐year period in relation to comparable counties (Wilcox et al., 2019). In addition, we think there is ample room for private enterprise to become strong supporters of CRE given what we know about how relationship problems impact workplace productivity (Turvey & Olson, 2006). Insurance companies and government health policies could subsidize participation in CRE, given cost savings due to the health benefits of healthy relationships (Robles et al., 2014).

Also, we believe there will continue to be a big role for the faith and educational sectors to support high‐quality CRE instruction. For 4 decades (and even before), religious organizations have been a major sponsor and provider of CRE, although, with declining rates of religious participation among young adults in the United States, we cannot expect religious organizations to carry as heavy a provider load as in the past. But religious organizations may be well suited to reach higher‐risk groups such as Hispanic immigrants and African Americans who are more likely to stay connected to organized religion. In addition, high schools and colleges are an important source of RE for youth and young adults. Community colleges that serve primarily disadvantaged young adults are especially needed to offer RE courses.

In sum, widespread institutional support for CRE will be crucial if we are to reach the numbers of couples who could benefit from these services. While there are notable illustrations of support for RE in each of these sectors, more buy‐in will be needed, and a strategy for how we get this kind of buy‐in does not exist currently. There is no one policy lever to pull. We think this is a major challenge we face and by shining light on it, we hope the next decade review will show progress in efforts to increase CRE support into more institutional budgets.

CONCLUSION

We have outlined notable progress in the CRE field over the past decade in this article. But just as hikers who arrive at the summit of one peak often only see more clearly the higher peaks beyond, there is yet a long way to go up a steep path. CRE will continue to be an important area of practice and research over the next decade. Innovation in the field will expand, driven by a social world in which relationships are becoming more diverse, increasingly complex, less institutionalized, and less circumscribed by widely shared norms, not to mention a growing understanding of the importance of strong social and personal relationships to mental and physical health (Holt‐Lunstad et al., 2017). We hope this review has engendered a sense of accomplishment while still spurring the further progress the field needs. We have high hopes that the best work in the CRE field is yet to come.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Scott Stanley and Howard Markman own a business that develops and sells relationship education curricula (PREP) including versions of PREP and Within My Reach. Galena Rhoades has been involved in developing relationship education curricula disseminated by PREP, including curricula such as Within My Reach.

Dr. Kim Halford is an author of the Couple CARE program that is discussed in the current paper. He has received royalties from the sale of that program, and consulting fees for training people in use of the program.

Markman, H. J. , Hawkins, A. J. , Stanley, S. M. , Halford, W. K. , & Rhoades, G. (2022). Helping couples achieve relationship success: A decade of progress in couple relationship education research and practice, 2010–2019. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 48, 251–282. 10.1111/jmft.12565

REFERENCES

* = study included in systematic review and summarized in Table 1.

- Accordino, M. P. , & Guerney, B. G., Jr (2003). Relationship enhancement couples and family outcome research of the last 20 years. The Family Journal, 11, 162–166. 10.1177/1066480702250146 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- * Allen, E. S. , Rhoades, G. K. , Stanley, S. M. , Loew, B. , & Markman, H. J. (2012). The effects of marriage education for army couples with a history of infidelity. Journal of Family Psychology, 26, 26–35. 10.1037/a0026742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- * Allen, E. , Rhoades, G. K. , Stanley, S. M. , & Markman, H. J. (2011). On the home front: Stress for recently deployed Army couples. Family Process, 50, 235–247. 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2011.01357.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- * Allen, E. S. , Stanley, S. M. , Rhoades, G. K. , Markman, H. J. , & Loew, B. A. (2011). Marriage education in the Army: Results of a randomized clinical trial. Journal of Couple and Relationship Therapy, 10, 309–326. 10.1080/15332691.2011.613309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- * Amato, P. R. (2014). Does social and economic disadvantage moderate the effects of relationship education on unwed couples? An analysis of data from the 15‐month Building Strong Families evaluation. Family Relations, 63, 343–355. 10.1111/fare.12069 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- * Bakhurst, M. G. , McGuire, A. C. L. , & Halford, W. K. (2017). Relationship education for military couples: A pilot randomized controlled trial of the effects of Couple CARE in Uniform. Journal of Couple & Relationship Therapy, 16, 167–187. 10.1080/15332691.2016.1238797 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barton, A. W. , Beach, S. R. H. , Bryant, C. M. , Lavner, J. A. , & Brody, G. H. (2018). Stress spillover, African Americans’ couple and health outcomes, and the stress‐buffering effect of family‐centered prevention. Journal of Family Psychology, 32, 186–196. 10.1037/fam0000376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- * Barton, A. W. , Beach, S. R. H. , Kogan, S. M. , Stanley, S. M. , Fincham, F. D. , Hurt, T. R. , & Brody, G. H. (2015). Prevention effects on trajectories of African American adolescents’ exposure to interparental conflict and depressive symptoms. Journal of Family Psychology, 29, 171–179. 10.1037/fam0000073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- * Barton, A. W. , Beach, S. R. H. , Lavner, J. A. , Bryant, C. M. , Kogan, S. M. , & Brody, G. H. (2017). Is communication a mechanism of relationship education effects among rural African Americans? Journal of Marriage and Family, 79, 1450–1461. 10.1111/jomf.12416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- * Barton, A. W. , Beach, S. R. H. , Wells, A. C. , Ingels, J. B. , Corso, P. S. , Sperr, M. C. , Anderson, T. N. , & Brody, G. H. (2018). The Protecting Strong African American Families Program: A randomized controlled trial with rural African American couples. Prevention Science, 19, 904–913. 10.1007/s11121-018-0895-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton, A. W. , Lavner, J. A. , & Beach, S. R. H. (2020). Can interventions that strengthen couples’ relationships confer additional benefits for their health? A randomized controlled trial with African American couples. Prevention Science, 22, 386–396. 10.1007/s11121-020-01175-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baucom, D. H. , Epstein, N. B. , Kirby, J. S. , & LaTaillade, J. L. (2015). Cognitive‐behavioral couple therapy. In Gurman A. S., Lebow J. L. & Snyder D. K. (Eds.), Clinical handbook of couple therapy (5th ed., pp. 23–60). Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- * Beach, S. R. H. , Barton, A. W. , Lei, M. K. , Brody, G. H. , Kogan, S. M. , Hurt, T. R. , Fincham, F. D. , & Stanley, S. M. (2014). The effect of communication change on long‐term reductions in child exposure to conflict: Impact of the Promoting Strong African American Families (ProSAAF) program. Family Process, 53, 580–595. 10.1111/famp.12085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- * Bodenmann, G. , Hilpert, P. , Nussbeck, F. W. , & Bradbury, T. N. (2014). Enhancement of couples’ communication and dyadic coping by a self‐directed approach: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 82, 580–591. 10.1037/a0036356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford, A. B. , Hawkins, A. J. , & Acker, J. (2015). If we build it, they will come: Exploring policy and practice implications of public support for couple and relationship education for lower income and relationally distressed couples. Family Process, 54, 639–654. 10.1111/famp.12151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- * Bradley, R. P. C. , Drummey, K. , Gottman, J. M. , & Gottman, J. S. (2014). Treating couples who mutually exhibit violence or aggression: Reducing behaviors that show a susceptibility for violence. Journal of Family Violence, 29, 549–558. 10.1007/s10896-014-9615-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Braithwaite, S. R. , & Fincham, F. D. (2009). A randomized clinical trial of a computer based preventive intervention: Replication and extension of ePREP. Journal of Family Psychology, 23, 32–38. 10.1037/a0014061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- * Braithwaite, S. R. , & Fincham, F. D. (2011). Computer‐based dissemination: A randomized clinical trial of ePREP using the actor partner interdependence model. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 49, 126–131. 10.1016/j.brat.2010.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- * Braithwaite, S. R. , & Fincham, F. D. (2014). Computer‐based prevention of intimate partner violence in marriage. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 54, 12–21. 10.1016/j.brat.2013.12.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busby, D. M. , Larson, J. H. , Holman, T. B. , & Halford, W. K. (2015). Flexible delivery approaches to couple relationship education: Predictors of initial engagement and retention of couples. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24(10), 3018–3029. 10.1007/s10826-014-0105-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- * Buzzella, B. A. , Whitton, S. W. , & Tompson, M. C. (2012). A preliminary evaluation of a relationship education program for male same‐sex couples. Couple and Family Psychology: Research and Practice, 1, 306–322. https://doi‐org.erl.lib.byu.edu/10.1037/a0030380 [Google Scholar]

- Carlson, R. G. , Fripp, J. , Munyon, M. D. , Daire, A. P. , Johnson, J. M. , & DeLorenzi, L. (2014). Examining passive and active recruitment for low‐income couples in relationship education. Marriage & Family Review, 50, 76–91. 10.1080/01494929.2013.851055 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clyde, T. L. , Hawkins, A. J. , & Willoughby, B. J. (2020). Revising premarital interventions for the next generation. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 46, 149–166. 10.1111/jmft.12378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clyde, T. L. , Wikle, J. S. , Hawkins, A. J. , & James, S. L. (2020). The effects of premarital education promotion policies on U.S. divorce rates. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 26, 105–120. 10.1037/law0000218 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- * Cordova, J. V. , Fleming, C. J. E. , Morrill, M. I. , Hawrilenko, M. , Sollenberger, J. W. , Harp, A. G. , Gray, T. D. , Darling, E. V. , Blair, J. M. , Meade, A. E. , & Wachs, K. (2014). The Marriage Checkup: A randomized controlled trial of annual relationship health checkups. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 82, 592–604. 10.1037/a0037097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowan, C. P. , & Cowan, P. A. (2019). Enhancing parenting effectiveness, fathers’ involvement, couple relationship quality, and children’s development: Breaking down the silos in family policy making and service delivery. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 11, 92–111. 10.1111/jftr.12301 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- * Cowan, C. P. , Cowan, P. A. , & Barry, J. (2011). Couples’ groups for parents of preschoolers: Ten‐year outcomes of a randomized trial. Journal of Family Psychology, 25, 240–250. 10.1037/a0023003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- * Doss, B. D. , Cicila, L. N. , Georgia, E. J. , Roddy, M. K. , Nowlan, K. M. , Benson, L. A. , & Christensen, A. (2016). A randomized controlled trial of the web‐based OurRelationship program: Effects on relationship and individual functioning. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 84, 285–296. 10.1037/ccp0000063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doss, B. D. , Knopp, K. , Roddy, M. K. , Rothman, K. , Hatch, S. G. , & Rhoades, G. (2020). Online programs improve relationship functioning for low‐income couples: Results from a nationwide randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 88, 283–294. 10.1037/ccp0000479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doss, B. D. , Roddy, M. K. , Nowlan, K. M. , Rothman, K. , & Christensen, A. (2019). Maintenance of gains in relationship and individual functioning following the online OurRelationship program. Behavior Therapy, 50(1), 73–86. 10.1016/j.beth.2018.03.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- * Fallahchai, R. , Fallahi, M. , & Ritchie, L. L. (2017). The impact of PREP training on marital conflicts reduction: A randomized controlled trial with Iranian distressed couples. Journal of Couple & Relationship Therapy, 16, 61–76. 10.1080/15332691.2016.1238793 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- * Feinberg, M. E. , & Jones, D. J. (2018). Experimental support for a family systems approach to child development: Multiple mediators of intervention effects across the transition to parenthood. Couple and Family Psychology: Research and Practice, 7, 63–75. 10.1037/cfp0000100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- * Feinberg, M. E. , Jones, D. E. , Hostetler, M. L. , Roettger, M. E. , Paul, I. M. , & Ehrenthal, D. B. (2016). Couple‐focused prevention at the transition to parenthood, a randomized trial: Effects on co‐parenting, parenting, family violence, and parent and child adjustment. Prevention Science, 17, 751–764. 10.1007/s11121-016-0674-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- * Feinberg, M. E. , Jones, D. E. , Kan, M. L. , & Goslin, M. C. (2010). Effects of family foundations on parents and children: 3.5 years after baseline. Journal of Family Psychology, 24, 532–542. 10.1037/a0020837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- * Feinberg, M. E. , Jones, D. E. , Roettger, M. E. , Hostetler, M. L. , Sakuma, K.‐L. , Paul, I. M. , & Ehrenthal, D. B. (2016). Preventative effects on birth outcomes: Buffering impact of maternal stress, depressions, and anxiety. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 20, 56–65. 10.1007/s10995-015-1801-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- * Feinberg, M. E. , Jones, D. E. , Roettger, M. E. , Solmeyer, A. , & Hostetler, M. L. (2014). Long‐term follow‐up of a randomized trial of family foundations: Effects on children's emotional, behavioral, and school adjustment. Journal of Family Psychology, 28, 821. https://doi‐org.erl.lib.byu.edu/10.1037/fam0000037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- * Feinberg, M. E. , Roettger, M. , Jones, D. E. , Paul, I. M. , & Kan, M. L. (2015). Effects of a psychosocial couple‐based prevention program on adverse birth outcomes. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 19, 102–111. 10.1007/s10995-014-1500-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Futris, T. G. , & Adler‐Baeder, F. (2013). The National Extension Relationship and Marriage Education Model: Core teaching concepts for relationship and marriage enrichment programming. National Extension Relationship and Marriage Education Network. https://www.fcs.uga.edu/docs/NERMEM.pdf#page=7

- Gordon, K. C. , Cordova, J. V. , Roberson, P. N. , Miller, M. , Gray, T. , Lenger, K. A. , Hawrilenko, M. , & Martin, K. (2018). An implementation study of relationship checkups as home visitations for low‐income at‐risk couples. Family Process, 58, 247–265. 10.1111/famp.12396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- * Halford, W. K. , Petch, J. , & Creedy, D. K. (2010). Promoting a positive transition to parenthood: A randomized clinical trial of couple relationship education. Prevention Science, 11, 89–100. 10.1007/s11121-009-0152-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- * Halford, W. K. , Rahimullah, R. H. , Wilson, K. L. , Occhipinti, S. , Busby, D. M. , & Larson, J. (2017). Four year effects of couple relationship education on low and high satisfaction couples: A randomized clinical trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 85, 495–507. 10.1037/ccp0000181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halford, W. K. , & van de Vijver, F. (2020). Culture, couple relationships standards and relationship education. In Halford W. K. & van de Vijver F. (Eds.), Cross–cultural family research and practice (pp. 677–718). Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Halpern‐Meekin, S. (2019). Social poverty: Low‐income parents and the struggle for family and community ties. New York University. [Google Scholar]

- Hatch, S. G. , Dowdle, K. K. , Aaron, S. C. , & Braithwaite, S. R. (2019). Marital text: A feasibility study. The Family Journal, 26, 351–357. 10.1177/1066480718786491 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins, A. J. , Allen, S. E. , & Yang, C. (2017). How does couple and relationship education affect relationship hope? An intervention‐process study with lower income couples. Family Relations, 66, 441–452. 10.1111/fare.12268 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins, A. J. , Blanchard, V. L. , Baldwin, S. A. , & Fawcett, E. B. (2008). Does marriage and relationship education work? A meta‐analytic study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 76(5), 723–734. 10.1037/a0012584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins, A. J. , & Erickson, S. E. (2015). Is couple and relationship education effective for lower income participants? A meta‐analytic study. Journal of Family Psychology, 29, 59–68. 10.1037/fam0000045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins, A. J. , Hokanson, S. , Loveridge, E. , Milius, E. , Duncan, M. , Booth, M. & Pollard, B. (2021). How effective are ACF‐funded couple relationship education programs? A meta‐analytic study. in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Hawkins, A. J. , Serrao‐Hill, M. , Eliason, S. A. , Simpson, D. M. & Hokanson, S. (2021). Do couple relationship education programs affect coparenting, parenting, and child wellbeing outcomes? A meta‐analytic study. Manuscript under review.

- Holt‐Lunstad, J. , Robles, T. F. , & Sbarra, D. A. (2017). Advancing social connection as a public health priority in the United States. American Psychologist, 72, 517–530. 10.1037/amp0000103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson et al (in press).

- Johnson, M. D. (2012). Healthy marriage initiatives: On the need for empiricism in policy implementation. American Psychologist, 67, 296–308. 10.1037/a0027743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- * Jones, D. E. , Feinberg, M. E. , Hostetler, M. L. , Roettger, M. E. , Paul, I. M. , & Ehrenthal, D. B. (2018). Family and child outcomes 2 years after a transition to parenthood intervention. Family Relations, 67, 270–286. 10.1111/fare.12309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- * Kalinka, C. J. , Fincham, F. D. , & Hirsch, A. H. (2012). A randomized clinical trial of online‐biblio relationship education for expectant couples. Journal of Family Psychology, 26, 159–164. 10.1037/a0026398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanter, J. B. , & Schramm, D. G. (2018). Brief interventions for couples: An integrative review. Family Relations, 67, 211–226. 10.1111/fare/12298s [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Karam, E. A. , Antle, B. F. , Stanley, S. M. , & Rhoades, G. K. (2015). The marriage of couple and relationship education to the practice of marriage and family therapy: A primer for integrated training. Journal of Couple & Relationship Therapy, 14, 277–295. 10.1080/15332691.2014.1002655 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Karney, B. F. , & Bradbury, T. N. (2020). Research on marital satisfaction and stability in the 2010s: Challenging conventional wisdom. Journal of Marriage and Family, 82, 111–116. 10.1111/jomf.12635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin, A. E. (2009). Understanding how and why psychotherapy leads to change. Psychotherapy Research, 19, 418–428. 10.1080/10503300802448899 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ketring, S. A. , Bradford, A. G. , Davis, S. Y. , Adler‐Baeder, F. , McGill, J. , & Smith, T. A. (2017). The role of the facilitator in couple relationship education. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 43, 374–390. 10.1111/jmft.12223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- * Kröger, C. , Kliem, S. , Zimmermann, P. , & Kowalski, J. (2018). Short‐term‐effectiveness of a relationship education program for distressed military couples, in the context of foreign assignments for the German armed forces. Preliminary findings from a randomized controlled study. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 44, 248–264. 10.1111/jmft.12250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- * Lavner, J. A. , Barton, A. W. , & Beach, S. R. H. (2019). Improving couples’ relationship functioning leads to improved coparenting: A randomized controlled trial with rural African American couples. Behavior Therapy, 50, 1016–1029. 10.1016/j.beth.2018.12.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- * Loew, B. , Rhoades, G. , Markman, H. , Stanley, S. , Pacifici, C. , White, L. , & Delaney, R. (2012). Internet delivery of PREP‐based relationship education for at‐risk couples. Journal of Couple & Relationship Therapy, 11, 291–309. 10.1080/15332691.2012.718968 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- * Lowenstein, A. E. , Altman, A. , Chou, P. M. , Faucetta, K. , Greeney, A. , Gubits, D. , Harris, J. , Hsueh, J. , Lundquist, L. , Michalopoulos, C. , & Nguyen, V. Q. . (2014). A family‐strengthening program for low‐income families: Final impacts from the Supporting Healthy Marriage evaluation, technical supplement . OPRE Report 2014‐09B. Office of Planning, Research, and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

- Lucier‐Greer, M. , & Adler‐Baeder, F. (2012). Does couple and relationship education work for individuals in stepfamilies? A meta‐analytic study. Family Relations, 61, 756–769. 10.1111/j.1741-3729.2012.00728.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lucier‐Greer, M. , Birney, A. J. , Gutierrez, T. M. , & Adler‐Baeder, F. (2017). Enhancing relationship skills and couple functioning with mobile technology: An evaluation of the Love Every Day mobile intervention. Journal of Family Social Work, 21, 152–171. 10.1080/10522158.2017.1410267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutui, S. , & Hawkins, A. J. (2021). What did the pandemic teach us about online relationship education and therapy? Institute for Family Studies Blog. https://ifstudies.org/blog/what‐did‐the‐pandemic‐teach‐us‐about‐online‐relationship‐education‐and‐therapy [Google Scholar]

- Markman, H. J. , & Floyd, F. (1980). Possibilities for the prevention of marital discord: A behavioral perspective. American Journal of Family Therapy, 8, 29–48. 10.1080/01926188008250355 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Markman, H. J. , Halford, W. K. , & Hawkins, A. J. (2019). Couple and relationship education. In Friese B. H., Whisman M., Celana M., Deater‐Decard K. & Jouriles E. N. (Eds.), Handbook of Contemporary Family Psychology: Family therapy and training (pp. 307–324). APA. [Google Scholar]

- Markman, H. J. , & Rhoades, G. K. (2012). Relationship education research: Current status and future directions. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 38, 169–200. 10.1111/j.1752-0606.2011.00247.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- * Markman, H. J. , Rhoades, G. K. , Stanley, S. M. , & Peterson, K. M. (2013). A randomized clinical trial of the effectiveness of premarital intervention: Moderators of divorce outcomes. Journal of Family Psychology, 27, 165–172. https://doi‐org.erl.lib.byu.edu/10.1037/a0031134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]