Abstract

Aim

This study examined the effects of group psychological counselling on transition shock in newly graduated nurses.

Background

Newly graduated nurses are often faced with transition shock as they enter the workforce. Helping them adapt to the new work environment and role as quickly as possible is an important goal for nursing managers.

Method

This prospective, parallel‐group, quasi‐experimental trial enrolled 71 newly graduated nurses who were randomly assigned to the intervention (n = 38) or control (n = 41) group. In addition to routine hospital training, the intervention group received psychological counselling. Participants were evaluated with the Transition Shock Scale of Newly Graduated Nurses before (pre) and after (post) the training with or without intervention.

Results

The total score and score on each dimension of the scale were decreased after the intervention (P < .05); control subjects showed no difference between pre‐ and post‐scores. The total score and score on each dimension were higher in the control group than in the intervention group (P < .05).

Conclusion

Psychological counselling alleviates transition shock in newly graduated nurses entering the workforce.

Implications for Nursing Management

Nursing managers can introduce group psychological counselling into their training programmes to increase the job readiness of newly graduated nurses.

Keywords: group psychological counselling, newly graduated nurses, transition shock

1. INTRODUCTION

Adapting to the work environment as quickly as possible is a challenge faced by all newly graduated nurses (Winfield et al., 2009). At the beginning of their career, newly graduated nurses face issues such as difficulty in executing medical orders, insufficient capacity, lack of technical skill and low job satisfaction, which cause considerable stress to the nurses and can result in transition shock. In this state, nurses experience feelings of self‐doubt, confusion and uncertainty about their roles because of the conflict between their previous experiences and the demands of their professional relationships and responsibilities, shortcomings in their skill set and their needs as they transition from a known to an unknown role (Duchscher, 2009).

Most newly graduated nurses face enormous pressure from their environment during role transition (Duchscher, 2009). Educational background, income level, mode of employment and place of origin are factors that influence the intensity of transition shock that nurses experience (Calleja et al., 2019; Darvill et al., 2014; Kim & Yoo, 2018). Poor transition leads to job burnout, which affects the quality of nursing care and results in high turnover in the profession. One study reported that transition shock resulted in an attrition rate of 35%–60% among newly graduated nurses after 1 year (Altier & Krsek, 2006). Therefore, helping newly graduated nurses adapt to the new work environment is an important goal for nursing managers.

Newly graduated nurses are often in a sensitive and emotionally unstable state because of changes in their interpersonal relationships, the discrepancy between their expectations and reality, stress, and other factors (Read & Laschinger, 2017). Professional training programmes do not adequately prepare nurses for their new work environment, such that they experience a strong sense of transition shock (Wildermuth et al., 2020). A positive and healthy work environment can facilitate nurses' transition to the professional realm (Calleja et al., 2019). To ensure a smooth transition, nurses need support and help from clinical instructors, the hospital department and other sources (Regan et al., 2017). Group psychological counselling can help individuals examine themselves, improve their relationships with others and adopt new attitudes and behaviours through interactions with others (Dang et al., 2014). Compared with individual counselling, group counselling can have a greater influence on participants, may be more appealing and is efficient and cost‐effective. Group counselling has been shown to reduce stress and coping skills (Ehsan et al., 2019; Karimi et al., 2019; Mirmahmoodi et al., 2020). In this study, we investigated whether group psychological counselling can reduce transition shock in newly graduated nurses and thus promote the physical and mental health of newly graduated nurses.

2. METHODS

2.1. Study design and participants

This prospective, parallel‐group, quasi‐experimental trial was conducted at a general hospital in Nanjing, Jiangsu Province, China in June 2019. Newly graduated nurses were defined as those who had worked for less than 1 year following graduation. The participants were randomly assigned to the intervention or control group. Participants in both groups were told that they would receive routine hospital training and group psychological counselling but were unaware of when the counselling would occur until they were instructed to attend the sessions. Participants in the control group did not receive group psychological until the end of all sessions of counselling in the intervention group. All participants signed a written, informed consent form before the start of the study.

Inclusion criteria were newly graduated nurses who volunteered to participate in this study. Exclusion criteria were newly graduated nurses who experienced major personal or family events that could affect their psychological state in the previous 6 months such as traffic accidents, bereavement, etc. Criteria for discontinuing participation in the study were as follows: (1) did not complete all investigations; (2) unable to continue participating in the study because of illness, pursuit of further study, maternity leave, etc.; and (3) voluntary withdrawal of informed consent during the study.

The sample size was estimated based on the , with a confidence interval of 95% (α = .05), statistical power of 90% (β = .1) and comparison boundary value of = 10.8. Based on a previous study (Zhaoxia et al., 2019), the standard deviation of the control group was S = 0.54, and the means of the intervention and control groups were = 2.14 and = 3.71, respectively. According to this calculation, the minimum sample size for each group was determined to be 20. However, considering potential dropout and in order to ensure an adequate sample size, we increased the sample size of each group by 120% (n = 22).

2.2. Data collection

Data were collected using a questionnaire consisting of two parts. The first section collected demographic information (including age, sex, marital status, education, sibship status), and the second part was a 27‐item Chinese version of Transition Shock Scale of Newly Graduated Nurses Scale (You‐ru et al., 2015), which comprises four dimensions: physical (six items), psychological (eight items), knowledge and skills (five items) and social culture and development (eight items). Answers to each item range from strongly disagree (1 point) to strongly agree (5 points). The final score for each participant (ranging from 27 to 135) was obtained from the total score of the related questions; a higher score reflected a higher degree of transition shock. The Cronbach's α coefficient of the total scale was .918, and the content validity was .906.

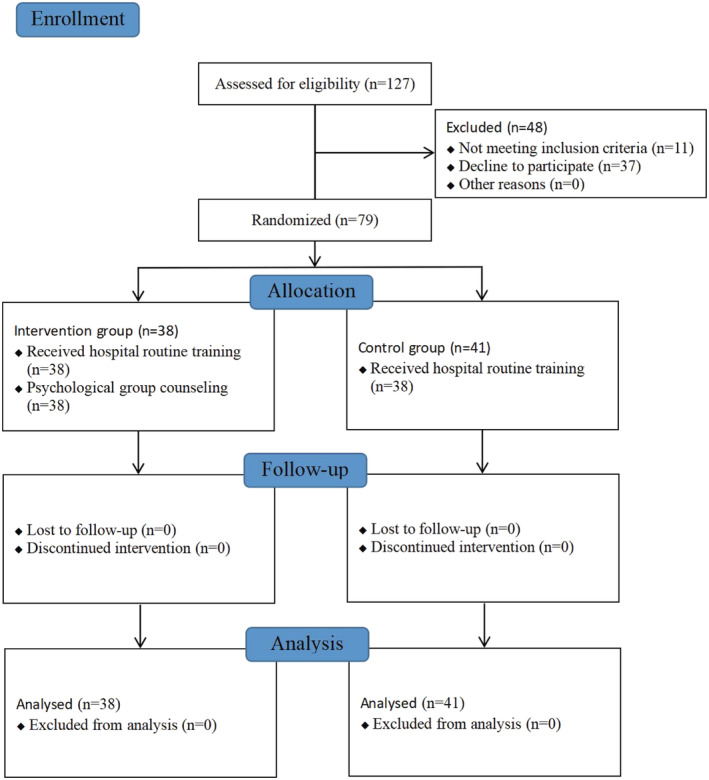

After coordinating with the relevant departments at the hospital, we recruited newly graduated nurses by convenience sampling; those who met the inclusion criteria and provided consented were enrolled. The study was explained to each participant in an in‐person interview at the hospital. We first identified 127 participants and excluded 48 (11 who did not meet the inclusion criteria and 37 who declined to participate). Thus, 79 newly graduated nurses constituted the study population. The participants were randomly assigned to the intervention and control groups using a random number table (Figure 1). Each participant completed the questionnaire before (pre) and after (post) the training (with or without intervention).

FIGURE 1.

Flow diagram at each stage of the quasi‐experimental trial

2.3. Intervention

Both groups received routine hospital training that included basic nursing theory and practical skills. The intervention group also received group psychological counselling for 5 weeks. The content of the counselling sessions (Table 1) was reviewed by professors specializing in nursing education and psychology. The intervention was carried out from September to October 2019 once a week for 60–90 min per session. To ensure maximum involvement of each participant in the intervention, the intervention group was divided into three subgroups with 12, 13 and 13 participants. Two instructors with extensive psychological counselling experience carried out the intervention at different times during the week.

TABLE 1.

The structure of the sessions and the content of psychological group counselling intervention

| Session | Theme | Target | Procedure | Homework |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Session 1 | Ice breaking action, self‐awareness | Members know each other, trust each other, and guide members to find their own advantages |

1. Self‐introduction: Pine moving, 2. Build a team and set sail: Stand together through storm and stress 3. Advantage evaluation: Self portrait |

Write a blessing for the team and use your strengths to accomplish one thing |

| Session 2 | Recognize the pressure and speak out | Recognize that pressure is common, and be good at telling it bravely |

1. Pressure ring 2. Speak out the pressure bravely 3. Facilitator summary |

Write down the things that have put pressure on you recently and how you deal with it |

| Session 3 | Control pressure and work happily | Learn how to decompress and discover your potential |

1. Share the moment of glory 2. Psychological yoga 3. Stress management training |

Use stress management training to relieve the stress caused by one thing |

| Session 4 | Barrier free communication, being grateful | Establish a good interpersonal relationship and establish the belief of being grateful for life and returning to the society |

1. Golden idea 2. Memories moved 3. Thanksgiving blessing |

Write a letter of gratitude |

| Session 5 | Harmony between you and me, towards the future | Think and plan for the future |

1. Wisdom relay 2. Time pizza 3. Unsent letter |

Develop future plans |

2.4. Data analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS v22.0 software (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). Categorical variables are described as frequencies (%), and the χ 2 test or Fisher's exact test was used to assess intergroup differences. Continuous and nonnormally distributed data were described as the median and interquartile range (25%–75%), and the Mann–Whitney U test or Wilcoxon signed‐rank test was used to evaluate intergroup differences. The threshold for significance was set to P < .05 for all tests.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Characteristics of the study population

A total of 79 newly graduated nurses (38 in the intervention group and 41 in the control group) were enrolled in the study. There were no statistically significant differences in age (χ 2 = .034, P = .854), sex (χ 2 = .431, P = .512), education level (χ 2 = .143, P = .705), marital status (χ 2 = .140, P =.708) or single‐child (χ 2 = .219, P = .639) between the two groups (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Demographic characteristics of the intervention and control group

| Variable | Intervention N (%) | Control N (%) | χ 2 | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||||

| 18–23 | 29 (76.31) | 32 (78.05) | .034 | .854 b |

| 24–30 | 9 (23.69) | 9 (21.95) | ||

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 2 (5.26) | 1 (2.44) | .431 | .512 a |

| Female | 36 (94.74) | 40 (97.56) | ||

| Education | ||||

| Junior college | 22 (57.89) | 22 (53.66) | .143 | .705 b |

| Undergraduate | 16 (42.1) | 19 (46.34) | ||

| Marital status | ||||

| Single | 36 (94.74) | 38 (92.68) | .140 | .708 a |

| Married | 2 (5.26) | 3 (7.32) | ||

| Single‐child | ||||

| No | 26 (68.42) | 26 (63.42) | .219 | .639 b |

| Yes | 12 (31.58) | 15 (36.58) | ||

Chi‐square test.

Fisher's exact test.

3.2. Transition shock evaluation

There was no statistically significant difference between two groups in physical aspect (Z = −1.096, P = .854), psychological aspect (Z = −0.413, P = .680), knowledge and skills aspect (Z = −0.143, P = .886), social culture and development aspect (Z = −0.860, P = .390) and total scores(Z = −0.648, P = .517) of the Transition Shock Scale of Newly Graduated Nurses Scale before the intervention. After the intervention, there was no significant improvement in physical aspect (Z = −1.374, P = .169), psychological aspect (Z = −0.747, P = .455), knowledge and skills aspect (Z = −0.468, P = .640), social culture and development aspect (Z = −0.033, P = .974) and total scores (Z = −0.663, P = .507) of the scale in the control group, whereas the intervention group showed significant improvement in physical aspect (Z = −3.798, P = .000), psychological aspect (Z = −3.935, P = .000), knowledge and skills aspect (Z = −3.431, P = .001), social culture and development aspec (Z = −3.112, P = .002), and total scores (Z = −4.317, P = .000) of the scale. There were also significant differences in post‐scores of physical aspect (Z = −4.182, P = .000), psychological aspect (Z = −3.980, P = .000), knowledge and skills aspect (Z = −4.547, P = .000), social culture and development aspect (Z = −3.657, P = .000) and total scores (Z = −4.345, P = .000) between groups (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Transition shock scores in the intervention and control group before and after psychological group counselling intervention`

| Variable | Before (median [IQR]) | After (median [IQR]) | Z # | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical aspect | ||||

| Intervention | 22 (18.5,25) | 18 (14.08,20) | −3.798 | .000 |

| Control | 23 (19,27.5) | 21.18 (20,24) | −1.374 | .169 |

| Z ## | −1.096 | −4.182 | ||

| P | .273 | .000 | ||

| Psychological aspect | ||||

| Intervention | 27 (22.75,31.5) | 22 (19.63,25.5) | −3.935 | .000 |

| Control | 28 (23.5,31.5) | 26.94 (24,30) | −0.747 | .455 |

| Z ## | −0.413 | −3.980 | ||

| P | .680 | .000 | ||

| Knowledge and skills aspect | ||||

| Intervention | 18 (15,20) | 15 (12.4,16) | −3.431 | .001 |

| Control | 18 (15,20) | 17.73 (16,19.5) | −0.468 | .640 |

| Z ## | −0.143 | −4.547 | ||

| P | .886 | .000 | ||

| Social culture and development aspect | ||||

| Intervention | 21 (14,25.25) | 17.32 (14.71,20) | −3.112 | .002 |

| Control | 21 (17,25) | 21.97 (19,24) | −0.033 | .974 |

| Z ## | −0.860 | −3.657 | ||

| P | .390 | .000 | ||

| Total | ||||

| Intervention | 85.5 (67,103.25) | 71.69 (61.19,83) | −4.317 | .000 |

| Control | 90 (77,102.5) | 87.82 (81.5,96) | −0.663 | .507 |

| Z ## | −0.648 | −4.345 | ||

| P | .517 | .000 | ||

Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range; Z#, Wilcoxon signed‐rank test; Z##, Mann–Whitney U test.

4. DISCUSSION

The transition shock evaluation scores of both the intervention and control groups in this study indicate that newly graduated nurses did not transition smoothly to the professional setting, consistent with previous findings (Dyess & Sherman, 2009). In the initial stage of adaptation to nursing work, newly graduated nurses face challenges in interpersonal relationships and with responsibilities, knowledge and skills. Difficulties in adapting to their professional role and overcoming transition shock can cause nurses to experience stress, role confusion, anxiety and other complex emotions and can even lead to resignation (Baumann et al., 2018; Lea & Cruickshank, 2015). A successful transition depends on organizational support; social support from senior nurses and the department can alleviate the stress of transition, improve nurses' ability to respond to work demands and reduce work‐related stress (Ashley et al., 2016; Regan et al., 2017). In the present study, our hospital adopted group psychological counselling as a way to provide support and guidance to newly graduated nurses.

The concept of transition shock is based on reality shock theory and has been proposed as an assessment model based on qualitative research (Duchscher, 2009). The model covers the physical, intellectual, emotional, developmental and sociocultural impact of transitions. The Transition Shock Scale of Newly Graduated Nurses Scale, which is based on reality shock theory but is applicable to real‐life situations, evaluates the intensity of transition shock of newly graduated nurses in four dimensions, namely, physical, psychological, knowledge and skills, and social culture and development (You‐ru et al., 2015). The physical dimension focuses on external performance, sleep, energy, etc. The psychological dimension comprises stress, feelings of inferiority and other emotions. The knowledge and skills dimension measures the ability to cope with practical problems at work. The social culture and development dimension assesses the integration of newly graduated nurses into the work environment and nursing profession. Based on these, the structure of the sessions and content of psychological group counselling intervention were formed.

Improving nurses' subjective well‐being is an effective way to enhance nurses' positive mental attitude, encourage their initiative and improve their work efficiency (Seguin, 2019). In order to increase the subjective well‐being of nurses, we used the first four counselling sessions to make the participants feel at ease by praising their colleagues, family members and friends and encouraging them to understand and actively help others and adopt positive communication methods to establish good interpersonal relationships. Newly graduated nurses can also choose to consider being busy at work as a source of happiness, as caring for and helping patients is a worthy endeavour.

Newly graduated nurses are often in an emotionally unstable state because of changes in their interpersonal relationships, conflict between their expectations and reality, stress and other factors. Improving psychological endurance can improve job satisfaction and reduce the risk of resignation (Zamanzadeh et al., 2015). In order to help participants develop their ability to cope with stress and recover quickly from stressful events, Sessions 2 and 3 were designed to allow participants to explore their own potential and strength through application of stress management skills to their life and work.

Successful adaptation to professional life by a nurse is associated with a decrease in negative emotions that reduces the impact of transition (Lan et al., 2016). Career adaptability is the ability to remain balanced during career changes, which is critical for an individual to achieve career success (Hou et al., 2012). In this study, Session 5 of the intervention was designed to provide newly graduated nurses with a quiet space to reflect on their professional goals. Rational career positioning can prevent nurses from making blind comparisons with other professions and help them maintain an appropriate career mentality while strengthening their professional identity and motivation to work and mobilizing positive factors that will allow them to cope with pressures and frustration in their work.

Most studies to date on professional training for nurses have focused on standardized methods in simulated training programmes and one‐on‐one tutorials that improve knowledge, skill level and job competency, while overlooking the fact that such interventions can add to the pressure felt by new nurses and thus achieve an effect contrary to the one that was intended. In this study, we provided group counselling to cultivate a positive attitude among participants through themed activities in a safe, non‐judgmental and respectful environment that allowed them to recognize their potential and strength, find happiness in learning, develop skills necessary for establishing positive relationships and coping with stress, and plan their careers and lives. Our results demonstrate that group psychological counselling can effectively reduce the transition shock experienced by newly graduated nurses.

4.1. Limitations

This study had some limitations. The small sample size limits the generalizability of the results; a multicenter study with a larger sample size is needed to validate our findings. The group psychological counselling only consisted of five sessions, and the long‐term impact of the intervention was not examined; this warrants further exploration in future studies to determine the cost‐effectiveness of such programmes.

5. CONCLUSION

Newly graduated nurses' overall level of coping with the transition to the work environment needs to be improved. Group psychological counselling significantly reduced transition shock in newly graduated nurses and should be integrated into professional training programmes.

5.1. Implications for nursing management

In addition to improving newly graduated nurses' knowledge and skills, nursing managers need to address the impact of transition shock. To help newly graduated nurses identify their strengths, overcome stress, build positive relationships and realize their potential, group psychological counselling can be introduced into daily management practices. Because nurses work in shifts, implementation of group sessions may be difficult. This can be circumvented by having each hospital department separately carry out group counselling sessions led by trained senior nurses. This can not only improve participation but can also allow emotional catharsis in a guided form with the nurses providing mutual support and forming a cohesive unit.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

No conflict of interest has been declared by the authors.

FUNDING INFORMATION

No funds.

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

The Ethics Committee of Jiangsu Province Hospital and Nanjing Medical University First Affiliated Hospital approved the study (approval number: 2019‐NT‐45). Written informed consent was obtained from individual participants.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Written informed consent for publication was obtained from all participants.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

B.X., S.L., W.B., M.W, Z.L. and X.W. implemented the study in China. B.X., S.L. and W.B. conducted the data analysis. B.X. and S.Y.L. wrote the initial draft of the manuscript. M.W., Z.L. and X.W. reviewed and revised the manuscript. Z.L. and X.W. designed and coordinated the study and take responsibility for the accuracy of the data analysis.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would also like to thank the Newly graduated nurses for their selfless participation as well as the nursing managers in their department.

Xu, B. , Li, S. , Bian, W. , Wang, M. , Lin, Z. , & Wang, X. (2022). Effects of group psychological counselling on transition shock in newly graduated nurses: A quasi‐experimental study. Journal of Nursing Management, 30(2), 455–462. 10.1111/jonm.13506

Bin Xu and Suyuan Li contributed to this work equally.

Contributor Information

Zheng Lin, Email: linzheng100@163.com.

Xuemei Wang, Email: treebranch701@sina.com.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- Altier, M. E. , & Krsek, C. A. (2006). Effects of a 1‐year residency program on job satisfaction and retention of new graduate nurses. Journal for Nurses in Staff Development, 22(2), 70–77. 10.1097/00124645-200603000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashley, C. , Halcomb, E. , & Brown, A. (2016). Transitioning from acute to primary health care nursing: An integrative review of the literature. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 25(15–16), 2114–2125. 10.1111/jocn.13185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumann, A. , Hunsberger, M. , Crea‐Arsenio, M. , & Akhtar‐Danesh, N. (2018). Policy to practice: Investment in transitioning new graduate nurses to the workplace. Journal of Nursing Management, 26(4), 373–381. 10.1111/jonm.12540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calleja, P. , Adonteng‐Kissi, B. , & Romero, B. (2019). Transition support for new graduate nurses to rural and remote practice: A scoping review. Nurse Education Today, 76, 8–20. 10.1016/j.nedt.2019.01.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dang, R. , Wang, Y. , Li, N. , He, T. , Shi, M. , Liang, Y. , … Hu, D. (2014). Effects of group psychological counseling on self‐confidence and social adaptation of burn patients. Zhonghua Shao Shang Za Zhi, 30(6), 487–490. 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1009-2587.2014.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darvill, A. , Fallon, D. , & Livesley, J. (2014). A different world? The transition experiences of newly qualified children's nurses taking up first destination posts within children's community nursing teams in England. Issues in Comprehensive Pediatric Nursing, 37(1), 6–24. 10.3109/01460862.2013.855841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duchscher, J. E. B. (2009). Transition shock: The initial stage of role adaptation for newly graduated registered nurses. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 65(5), 1103–1113. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2008.04898.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyess, S. M. , & Sherman, R. O. (2009). The first year of practice: New graduate nurses' transition and learning needs. Journal of Continuing Education in Nursing, 40(9), 403–410. 10.3928/00220124-20090824-03 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehsan, Z. , Yazdkhasti, M. , Rahimzadeh, M. , Ataee, M. , & Esmaelzadeh‐Saeieh, S. (2019). Effects of group counseling on stress and gender‐role attitudes in infertile women: A clinical trial. Journal of Reproduction & Infertility, 20(3), 169–177. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou, Z. , Leung, S. , Li, X. , & Hui, X. (2012). Career adapt‐abilities scale—China form: Construction and initial validation. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 80(3), 686–691. 10.1016/j.jvb.2012.01.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Karimi, Z. , Rezaee, N. , Shakiba, M. , & Navidian, A. (2019). The effect of group counseling based on quality of life therapy on stress and life satisfaction in family caregivers of individuals with substance use problem: A randomized controlled trial. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 40(12), 1012–1018. 10.1080/01612840.2019.1609635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, K. J. , & Yoo, M. S. (2018). The influence of psychological capital and work engagement on intention to remain of new graduate nurses. The Journal of Nursing Administration, 48(9), 459–465. 10.1097/NNA.0000000000000649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan, L. , Siwei, L. , Yangguang, C. , & Yanping, W. (2016). Impact of career adaptability on their transition shock for newly graduated nurses. Chinese Journal of Modern Nursing, 22(21), 2971–2974. 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1674-2907.2016.21.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lea, J. , & Cruickshank, M. (2015). Supporting new graduate nurses making the transition to rural nursing practice: Views from experienced rural nurses. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 24(19–20), 2826–2834. 10.1111/jocn.12890 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirmahmoodi, M. , Mangalian, P. , Ahmadi, A. , & Dehghan, M. (2020). The effect of mindfulness‐based stress reduction group counseling on psychological and inflammatory responses of the women with breast Cancer. Integrative Cancer Therapies, 19, 1872165251. 10.1177/1534735420946819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read, E. , & Laschinger, H. (2017). Transition experiences, intrapersonal resources, and job retention of new graduate nurses from accelerated and traditional nursing programs: A cross‐sectional comparative study. Nurse Education Today, 59, 53–58. 10.1016/j.nedt.2017.08.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regan, S. , Wong, C. , Laschinger, H. K. , Cummings, G. , Leiter, M. , MacPhee, M. , … Read, E. (2017). Starting out: Qualitative perspectives of new graduate nurses and nurse leaders on transition to practice. Journal of Nursing Management, 25(4), 246–255. 10.1111/jonm.12456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seguin, C. (2019). A survey of nurse leaders to explore the relationship between grit and measures of success and well‐being. The Journal of Nursing Administration, 49(3), 125–131. 10.1097/NNA.0000000000000725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wildermuth, M. M. , Weltin, A. , & Simmons, A. (2020). Transition experiences of nurses as students and new graduate nurses in a collaborative nurse residency program. Journal of Professional Nursing, 36(1), 69–75. 10.1016/j.profnurs.2019.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winfield, C. , Melo, K. , & Myrick, F. (2009). Meeting the challenge of new graduate role transition: Clinical nurse educators leading the change. Journal for Nurses in Staff Development, 25(2), E7–E13. 10.1097/NND.0b013e31819c76a3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- You‐ru, X. , Ping, L. , Xue‐qin, G. , Zhen‐juan, Z. , Ling, L. , Guo‐jie, L. , Wei, C. , & Shu‐fen, Y. (2015). Development and the reliability and validity test of the transition shock of newly graduated nurses scale. Chinese Journal of Nursing, 50(06), 674–678. 10.3761/j.issn.0254-1769.2015.06.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zamanzadeh, V. , Jasemi, M. , Valizadeh, L. , Keogh, B. , & Taleghani, F. (2015). Lack of preparation: Iranian Nurses' experiences during transition from college to clinical practice. Journal of Professional Nursing, 31(4), 365–373. 10.1016/j.profnurs.2015.01.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhaoxia, M. , Jie, N. , Xiaoru, C. , & Guiqin, L. (2019). The influence of positive psychology group counseling on the transition shock of newly graduated nurses. Chinese Nursing Management, 19(09), 1339–1342. 10.3969/j.issn.1672-1756.2019.09.012 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.