Abstract

Background and purpose

Differentiation between acute flaccid myelitis (AFM) and Guillain–Barré syndrome (GBS) can be difficult, particularly in children. Our objective was to improve the diagnostic accuracy by giving recommendations based on a comparison of clinical features and diagnostic criteria in children with AFM or GBS.

Methods

A cohort of 26 children with AFM associated with enterovirus D68 was compared to a cohort of 156 children with GBS. The specificity of the Brighton criteria, used for GBS diagnosis, was evaluated in the AFM cohort and the specificity of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) AFM diagnostic criteria in the GBS cohort.

Results

Children with AFM compared to those with GBS had a shorter interval between onset of weakness and nadir (3 vs. 8 days, p < 0.001), more often had asymmetric limb weakness (58% vs. 0%, p < 0.001), and less frequently had sensory deficits (0% vs. 40%, p < 0.001). In AFM, cerebrospinal fluid leukocyte counts were higher, whereas protein concentrations were lower. Spinal cord lesions on magnetic resonance imaging were only found in AFM patients. No GBS case fulfilled CDC criteria for definite AFM. Of the AFM cases, 8% fulfilled the Brighton criteria for GBS, when omitting the criterion of excluding an alternate diagnosis.

Conclusions

Despite the overlap in clinical presentation, we found distinctive early clinical and diagnostic characteristics for differentiating AFM from GBS in children. Diagnostic criteria for AFM and GBS usually perform well, but some AFM cases may fulfill clinical diagnostic criteria for GBS. This underlines the need to perform diagnostic tests early to exclude AFM in children suspected of atypical GBS.

Keywords: acute flaccid myelitis, Brighton criteria, Guillain–Barré syndrome

A child with acute onset flaccid weakness may pose a diagnostic challenge for clinicians, with both acute flaccid myelitis (AFM) and Guillain–Barré syndrome (GBS) included in the differential diagnosis. We provide distinguishing features and recommendations, which may help clinicians in making the right diagnosis. In cases of atypical GBS, the diagnosis of AFM needs to be excluded early in the disease course, as AFM may fulfill the current clinical, cerebrospinal fluid, and nerve conduction studies diagnostic criteria for GBS.

INTRODUCTION

Both acute flaccid myelitis (AFM) and Guillain–Barré syndrome (GBS) usually present with rapidly progressive limb weakness with low tendon reflexes, preceded by a prodromal illness. At onset of disease, it may be difficult to differentiate between these two conditions, especially in children. This is demonstrated by reported cases of AFM, which were initially diagnosed as atypical GBS [1]. Early differentiation is important, because there are considerable differences in diagnostic workup, treatment options, and prognosis.

AFM has been defined by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) as acute flaccid limb weakness, combined with a spinal cord lesion in the gray matter on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) [2]. Other criteria for AFM have been proposed, with additionally required features regarding clinical course and outcome and results of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and nerve conduction studies (NCS) as well as positive diagnostic polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for enterovirus D68 (EV‐D68) and EV‐A71, which are among the viruses associated with AFM [3, 4]. GBS has been defined by diagnostic criteria from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) and more recently by diagnostic criteria from the Brighton Collaboration, in which clinical, CSF, and NCS parameters are used to classify the level of certainty of the diagnosis [5, 6].

In this study, we compared two well‐described cohorts of children diagnosed with AFM associated with EV‐D68, or GBS with respect to clinical presentation and diagnostic features and compared the specificity of current diagnostic criteria for AFM and GBS. The results were used to provide additional recommendations for an early and accurate diagnosis of either AFM or GBS.

METHODS

Study cohorts

The AFM cohort consists of 26 children (<18 years old), who were selected from a previously described cohort of 29 European patients (adults and children) with AFM associated with EV‐D68 [7]. This cohort included patients who were retrospectively identified by sending questionnaires to the European AFM Working Group. EV‐D68‐associated AFM was defined as acute onset focal limb weakness with MRI abnormalities and a positive PCR for EV‐D68 in either respiratory, fecal, blood, or CSF specimens. When MRI data were not available or MRI was described as normal, CSF pleocytosis was sufficient for a probable diagnosis of AFM, in concordance with the CDC case definition for AFM from 2018 [7, 8].

The GBS cohort is composed of 156 children (<18 years old) from nine hospitals in the Netherlands. Most patients in the GBS cohort were included in previously published studies; 68 patients were collected in a retrospective study in one hospital [9], and 14 patients were included in the International GBS Outcome Study, a prospective multicenter study [10]. The other 74 patients were retrospectively collected from nine Dutch hospitals. The NINDS diagnostic criteria from 1990 were used as guidelines for the diagnosis of GBS [6, 9, 11]. For defining the GBS electrophysiological subtypes, we used the Hadden classification [12]. From both cohorts, information was collected regarding preceding infection, first symptom, neurological deficits at admission and nadir, and results of additional tests (CSF, NCS, MRI of brain and spinal cord, and virology diagnostics), as well as treatment type and disease course. Severity of the disease at nadir was defined by the highest GBS disability score during the course of the disease. The GBS disability score includes 0 (normal), 1 (minor symptoms, capable of running), 2 (able to walk 10 m or more without assistance but unable to run), 3 (able to walk 10 m across an open space with help), 4 (bedridden or chair bound), 5 (requiring assisted ventilation for at least part of the day), and 6 (dead) [13]. Good clinical outcome was defined as reaching GBS disability score ≤ 2 at several time points during follow‐up (1 month, 2 months, 3 months, 6 months, and 12 months after onset). CSF protein level was considered to be increased when >0.65 g/L for age 1–3 months, >0.37 g/L for 3–6 months, >0.35 g/L for 6–12 months, >0.31 g/L for 1–10 years, and >0.49 g/L for 10–18 years [14].

Comparison studies

A comparison between these two cohorts was made for (i) demographic characteristics, including age, sex, and month of onset; (ii) presence, type, and timing of preceding prodromal syndrome; (iii) clinical features at admission and nadir, including severity, localization, and symmetry of muscle weakness, cranial nerve involvement, sensory deficits, reflexes, respiratory failure, and autonomic dysfunction; (iv) results of additional investigations, including CSF, NCS, and MRI; and (v) clinical course and outcome.

Diagnostic criteria

The diagnostic criteria from the Brighton Collaboration, which were previously validated for GBS in children, were applied to both cohorts (excluding the criterion of absence of an alternative diagnosis in the AFM cohort) [5, 9]. The Brighton criteria consist of the following items: (i) bilateral limb weakness, (ii) decreased or absent deep tendon reflexes in weak limbs, (iii) monophasic disease course, (iv) normal CSF cell count, (v) increased CSF protein level, and (vi) NCS findings consistent with GBS (Table S1).

The case definitions for AFM published by the CDC in 2018 and 2019 were applied to both cohorts. In the 2018 case definition, the combination of acute flaccid limb weakness and MRI abnormalities in the gray matter of the spinal cord was required for a definite diagnosis, whereas acute flaccid limb weakness combined with CSF pleocytosis fulfilled the criteria for a probable diagnosis of AFM. In the 2019 criteria, a definite diagnosis is described as a combination of acute flaccid weakness and MRI abnormalities predominantly in the gray matter, spanning one or more segments, with exclusion of malignancy, vascular disease, or anatomic abnormalities as an explanation for the spinal cord lesion. Criteria for a probable diagnosis are similar to those for a definite diagnosis, except that gray matter involvement of the spinal cord lesion has to be present but does not have to be predominant. A suspected case is defined as any case of acute flaccid limb weakness (Figure S1, Table S2) [2, 8].

Statistics

For the statistical analysis, we used SPSS 25. Continuous data were presented as means and standard deviations if normally distributed, and otherwise as medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs). Categorical data were presented as proportions. Continuous data of the two cohorts were compared with t‐test if normally distributed and with Mann–Whitney U test if not normally distributed. Proportions were compared using the chi‐squared or Fisher exact test. The survival distribution of the two groups was calculated using the log‐rank test. The Bonferroni correction was applied to correct for multiple comparisons. A two‐sided p‐value < 0.05 was considered significant.

Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and patient consents

Studies from which data were used were approved by the medical ethical review committee of the coordinating centers.

Data availability

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article, within the limits of the General Data Protection Regulation privacy regulations.

RESULTS

Demographic characteristics

Included were 26 children diagnosed with AFM associated with EV‐D68, and 156 children diagnosed with GBS. Median age of the AFM group was 3 years (IQR = 2–5, full range = 1–9) versus 7 years (IQR = 3–13, full range = 0–17) for the GBS cohort (p < 0.001; Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Demography and clinical presentation of AFM and GBS in children

| AFM, n = 26 | GBS, n = 156 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demography | |||

| Male:female (% male) | 14:12 (54) | 82:74 (53) | ns |

| Age, years, median (IQR, full range) | 3 (2–5, 8) | 7 (3–13, 17) | <0.001 |

| Antecedent events | |||

| Time antecedent event–onset weakness, days, median (IQR, full range) | 7 (5–8, 10) | 11 (7–15, 41) | ns |

| No antecedent event, n (%) | 1/26 (4) | 19/143 (13) | ns |

| Respiratory tract infection, n (%) | 23/26 (89) | 66/146 (45) | <0.001 |

| Vomiting, n (%) | 2/26 (8) | 32/118 (27) | ns |

| Diarrhea, n (%) | 5/26 (19) | 47/145 (32) | ns |

| Fever, n (%) | 22/24 (92) | 51/140 (36) | <0.001 |

| Vaccination, n (%) a | 0/2 (0) | 11/130 (9) | np |

| Time onset weakness–admission, days, median (IQR, full range) b | 0 (0, 5) | 5 (3–8, 30) | <0.001 |

| Time onset weakness–nadir, days, median (IQR, full range) c | 3 (2–5, 9) | 8 (5–10, 38) | <0.001 |

| Neurological symptoms at admission, n (%) | |||

| Sensory deficits | 0/26 (0) | 41/102 (40) | <0.001 |

| Pain | 8/24 (33) | 92/130 (71) | <0.001 |

| Limb weakness | 25/25 (100) | 122/135 (90) | ns |

| Weakness arms | 19/25 (76) | 90/131 (69) | ns |

| Weakness legs | 17/24 (71) | 121/135 (90) | ns |

| Asymmetric weakness | 14/24 (58) | 0/133 (0) | <0.001 |

| Cranial nerve involvement | 6/24 (25) | 51/141 (36) | ns |

| Autonomic dysfunction | 0/24 (0) | 13/122 (11) | ns |

| Areflexia/hyporeflexia | 19/21 (91) | 80/111 (72) | ns |

| Neurological symptoms at nadir, n (%) | |||

| Sensory deficits | 0/24 (0) | 66/112 (59) | <0.001 |

| Pain | 2/28 (7) | 107/132 (81) | <0.001 |

| Limb weakness | 25/25(58) | 145/146 (99) d | ns |

| Weakness arms | 22/25 (88) | 126/144 (88) | ns |

| Weakness legs | 20/24 (83) | 142/144 (99) | ns |

| Asymmetric weakness | 11/20 (55) | 0/142 (0) | <0.001 |

| Cranial nerve involvement | 12/25 (48) | 77/140 (55) | ns |

| Autonomic dysfunction | 3/25 (12) | 64/136 (47) | ns |

| Areflexia/hyporeflexia | 21/23 (91) | 120/129 (93) | ns |

| Mechanical ventilation, n (%) | 16 (64) | 37 (24) | <0.001 |

| Duration intubation, days, median (IQR, full range) e | 29 (15–365, 716) | 20 (12–32, 134) | ns |

| Time onset weakness–respiratory failure, days, median (IQR, full range) f | 1 (1–4, 3) | 6 (4–11, 61) | <0.001 |

Due to small patient numbers, not all items were compared (mentioned as np).

Abbreviations: AFM, acute flaccid myelitis; GBS, Guillain–Barré syndrome; IQR, interquartile range; np, not performed; ns, not significant.

The information on vaccinations in the AFM cohort was missing for 24 patients.

The median time between onset of weakness and admission was based on 18 AFM patients and 141 GBS patients.

The median time between onset of weakness and nadir was based on 17 AFM patients and 129 GBS patients.

One patient in the GBS cohort was diagnosed with sensory GBS and never developed (bilateral) limb weakness.

The median time of intubation was based on six AFM patients; this information was missing for 10 patients. In the GBS cohort, this information was complete.

The median time between onset of weakness and respiratory failure in the AFM cohort was based on five patients.

Whereas most children with AFM presented during summer and early autumn, children with GBS presented during the whole year, with the highest frequencies in June and December (p = 0.038).

Clinical presentation and course

Most children with AFM or GBS had symptoms of a preceding infection, 96% and 87%, respectively.

Time between onset of weakness and hospital admission was shorter for the children with AFM, with a median of 0 days (IQR = 0) versus 5 days (IQR = 3–8) in GBS patients (Table 1).

At admission, patients with AFM more often had asymmetric weakness than children with GBS (58% vs. 0%, p < 0.001). None of the children with AFM had sensory deficits at onset, compared to 40% of children with GBS. At onset, in 33% of children with AFM pain was reported, compared to 71% of children with GBS (Table 1).

The time between onset of symptoms and time of nadir was shorter for AFM patients (median = 3 days, IQR = 2–5 vs. median = 8 days, IQR = 5–10). At nadir, 83% of AFM patients had bilateral weakness, compared to 99% of GBS patients. Only one patient with GBS did not have bilateral weakness but a purely sensory form.

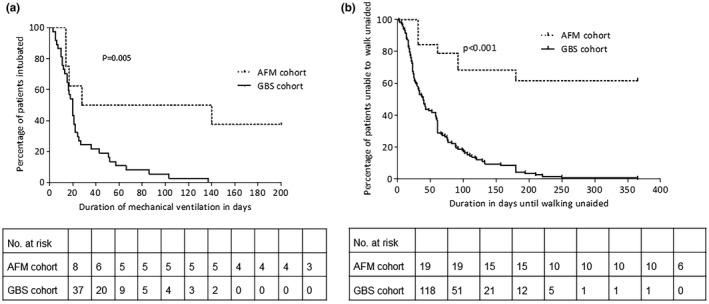

More patients with AFM required mechanical ventilation, and respiratory failure developed earlier after onset of symptoms (Table 1). Duration of mechanical ventilation was longer in AFM patients, reflecting a more severe and prolonged clinical course and poorer recovery (Figure 1a). The poor outcome of AFM compared to GBS is also reflected in the proportion of children able to walk unaided after 6 months (46% vs. 93%) and 12 months (50% vs. 99%; Figure 1b).

FIGURE 1.

(a) Duration of mechanical ventilation in the acute flaccid myelitis (AFM) and Guillain–Barré syndrome (GBS) cohorts. Three patients from the AFM cohort were still intubated at 200 days. The difference between the duration of intubation between the two groups was based on log‐rank test. (b) Long‐term prognosis, indicating time until the ability to walk unaided. Included were the patients who were unable to walk unaided at nadir (GBS disability score >2). The long‐term follow‐up was available until 1 year after onset of weakness. The difference between the duration until independent walking between the two groups was based on log‐rank test

Additional diagnostic tests

Lumbar puncture was performed in most patients with AFM and GBS, but the timing after onset of symptoms was earlier in patients with AFM compared to GBS (Table 2). In the patients with GBS, CSF protein level was more frequently elevated and higher than in the patients with AFM. GBS patients with normal CSF protein level had an earlier lumbar puncture after onset of symptoms than GBS patients with an elevated CSF protein level (median = 4 days, IQR = 3–5.75 vs. median = 7 days, IQR = 4–11, p < 0.001). The median number of leukocytes in CSF was higher for the AFM cohort (79 vs. 4/μL, p < 0.001), as was the proportion of patients with CSF pleocytosis (Table 2). A cytoalbuminologic dissociation was less often found in the AFM group.

TABLE 2.

Additional diagnostic test results in children with AFM and GBS

| Procedure | AFM, n = 26 | GBS, n = 156 | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| LP | |||

| LP performed, n (%) | 23/26 (89) | 143/154 (93) | ns |

| Time onset weakness–LP, days, median (IQR, full range) a | 1 (1–2, 4) | 6 (4–9, 32) | <0.001 |

| Raised protein level, n (%) b | 12/17 (71) | 111/141 (79) | ns |

| Protein concentration in CSF, g/L, median (IQR, full range) c | 0.44 (0.30–0.59, 1.39) | 0.76 (0.43–1.61, 7.57) | 0.004 |

| Leukocyte number in CSF, median (IQR, full range) d | 79 (25–149, 414) | 4 (1–9, 133) | <0.001 |

| CSF leukocyte count ≤ 5, n (%) | 3/20 (15) | 86/133 (65) | <0.001 |

| CSF leukocyte count 5–50, n (%) | 5/18 (28) | 40/133 (30) | ns |

| CSF leukocyte count ≥ 50, n (%) | 11/18 (61) | 5/133 (4) | <0.001 |

| Cytoalbuminologic dissociation, n (%) e | 3/16 (19) | 99/132 (75) | <0.001 |

| MRI, n (%) | |||

| MRI performed | 24/24 (100) | 16/113 (14) | <0.001 |

| MRI lesions brainstem | 18/24 (75) | 1/8 (13) | np |

| MRI lesion spinal cord | 19/23 (83) | 0/8 (0) | np |

| MRI nerve root thickening | 5/21 (24) | 3/7 (43) | np |

| NCS | |||

| NCS performed, n (%) | 11/26 (42) | 96/120 (80) | <0.001 |

| Time onset weakness–NCS, days, median (IQR, full range) f | 6 (4–9, 14) | 9 (5–14, 36) | ns |

| Normal, n (%) | 1/11 (10) | 8/94 (9) | np |

| Equivocal, n (%) | 4/10 (40) | 16/85 (19) | np |

| Unresponsive, n (%) | 0/10 (0) | 1/85 (1) | np |

| AMAN, n (%) | 5/10 (50) | 8/85 (9) | np |

| AMSAN, n (%) | 0/10 (0) | 2/85 (2) | np |

| AIDP, n (%) | 0/10 (0) | 50/85 (59) | np |

Where p > 0.05, this is mentioned as ns. Due to small patient numbers, not all items were compared (mentioned as np).

Abbreviations: AFM, acute flaccid myelitis; AIDP, acute inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy; AMAN, acute motor axonal neuropathy; AMSAN, Acute motor and sensory axonal neuropathy; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; GBS, Guillain–Barré syndrome; IQR, interquartile range; LP, lumbar puncture; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; NCS, nerve conduction studies; np, not performed; ns, not significant.

The information on onset weakness and performing LP was available for 15 patients from the AFM cohort and for 117 patients from the GBS cohort.

Raised protein was defined as a protein level of >0.65 g/L for the age of 1–3 months, >0.37 g/L for 3–6 months, >0.35 g/L for 6–12 months, >0.31 g/L for 1–10 years, and >0.49 g/L for 10–18 years.

The information on protein concentration in CSF was available for 15 AFM patients and 138 GBS patients.

The information on the number of leukocytes in CSF was available for 18 AFM patients and 133 GBS patients.

Cytoalbuminologic dissociation: protein level > the age dependent reference values and leukocytes < 50.

In 52 patients from the GBS cohort, the information for onset of weakness and NCS was missing.

MRI was performed in almost all AFM patients, but in only 14% of the GBS patients. Lesions of the spinal cord and brainstem were more often seen in AFM patients, whereas the presence of nerve root enhancement was found equally frequently (Table 2).

NCSs were performed in 42% of patients with AFM and 80% of patients with GBS. These were normal in one AFM patient, examined on the first day of symptoms, but revealed abnormalities in most patients, most often consistent with axonal damage. In GBS patients, abnormalities were found in 91% of patients, most often compatible with a demyelinating polyneuropathy (Table 2).

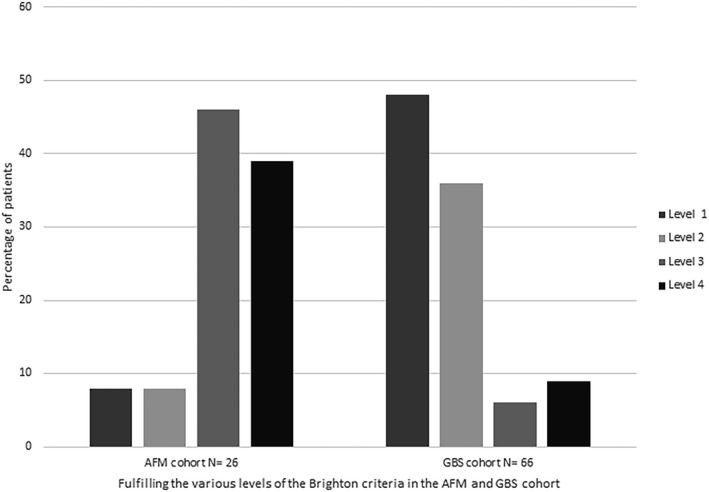

Evaluation of clinical criteria

The Brighton criteria for GBS were evaluated in the AFM cohort (except for the criterion of excluding alternative diagnosis). Two (8%) of the patients with AFM fulfilled all the Brighton criteria for a diagnosis of GBS at Level 1 certainty, two (8%) reached Level 2, 12 (46%) reached Level 3, and 10 (39%) reached Level 4 (Figure 2, Table S1). For the 2018 CDC criteria for AFM, all of our AFM patients with sufficient data fulfilled the criteria for definite or probable AFM. Of a subset of 38 GBS patients with sufficient data, 32 fulfilled the criteria for probable AFM with a CSF pleocytosis (Figure S1, Table S2), but MRI was not performed in any of these patients. Of the patients with GBS, none fulfilled the 2019 CDC criteria for probable or definite AFM. From the AFM cohort, three patients (13%) also did not fulfill these criteria (Figure S1, Table S2).

FIGURE 2.

Performance of the Brighton diagnostic criteria for Guillain–Barré syndrome (GBS) in the acute flaccid myelitis (AFM) and GBS cohorts. Percentage of patients fulfilling the various levels of the GBS diagnostic criteria from the Brighton Collaboration (except for the criterion to exclude an alternative diagnosis in the AFM cohort) are shown [5]. Level 1: Patient fulfills all criteria. Level 2: All items of Level 1 except the cerebrospinal fluid findings are not required. Level 3: All items of Level 2 except nerve conduction studies findings are not required. Level 4: No alternative diagnosis can be present; all other criteria are not required. For the AFM patients, this criteria was excluded

DISCUSSION

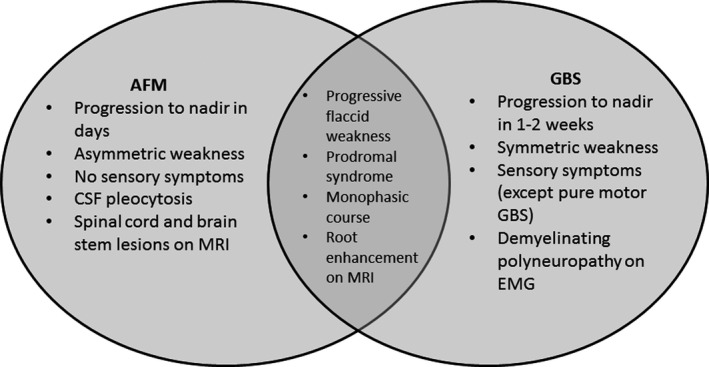

This comparative study in children shows that there is a considerable overlap in the clinical presentation of AFM and GBS, in accordance with the differential diagnosis in current practice. The majority of children with either AFM or GBS presented with a prodromal disease and progressive flaccid weakness of the limbs with reduced reflexes, and had a monophasic disease course. Some of the AFM patients even fulfilled the clinical diagnostic criteria for GBS, at least if involvement of spinal cord gray matter and viral infections related to AFM are not taken into account.

Nonetheless, our study also shows that there are important distinguishing early features, as illustrated in Figure 3. AFM compared to GBS in children is more rapidly progressive, and clinical nadir is usually reached within days and related to the presence of asymmetric limb weakness and absence of sensory deficits. The numbers for sensory deficits and pain in the AFM cohort may, however, be an underestimation, as the age in the AFM cohort is significantly lower and the assessment of pain and sensory deficits may be challenging in younger children.

FIGURE 3.

Venn diagram illustrating overlapping and differentiating features of acute flaccid myelitis (AFM) and Guillain–Barré syndrome (GBS). The indicated features are suggestive of either diagnosis, but they are not necessarily present or exclusive. CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; EMG, electromyography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging

CSF pleocytosis (>50 cells/µL) is frequent in AFM but rare in GBS, but an increase in protein level or mildly elevated cell count (5–50/µL) does not differentiate between AFM and GBS. NCS performed after the acute stage of disease frequently show peripheral nerve involvement in both disorders, but usually demyelinating in GBS and always axonal in AFM. Later in the disease course, it becomes evident that a protracted course and persistent weakness are associated with AFM.

The demography, clinical presentation, diagnostic test results, and clinical course of the presented cohorts of children with AFM and GBS resemble other cohorts of patients with these conditions [15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20]. Therefore, these characteristics are likely representative for children with either AFM or GBS.

This is the first comparative study between GBS and AFM, both in children and adults. A recent study did compare a group with restrictively defined or "true" AFM with a group of patients with alternative diagnoses, matching the 2018 case definition of the CDC [3]. Several clinical factors, such as the asymmetry and the absence of sensory deficits, resemble the distinctive features found in our study. Further similarities are the CSF pleocytosis and MRI abnormalities that were more often found in the "true" AFM group [3].

The CDC criteria are highly selective in excluding GBS, as there is a focus on MRI findings to make a probable or definite diagnosis of AFM. Also in our cohort, none of the children with GBS fulfilled the 2019 CDC criteria. MRI may be normal in the early phase of AFM or can show only subtle abnormalities [15]. Therefore, a combination of clinical criteria and results from diagnostic tests may be more appropriate, as was suggested previously [3]. The content of different criteria does, however, depend on the goal for which these criteria are used; a broader case definition should be used for case detection, whereas a restricted definition is more suitable for research purposes. Recently, an international working group proposed new diagnostic criteria for AFM, which are broadly similar to most recent CDC criteria. CSF pleocytosis and the presence of sensory deficits were adequately suggested as markers for an alternate diagnosis [21].

The criteria developed by the Brighton Collaboration for the diagnosis GBS were developed as case definitions for vaccine safety studies but also reflect the diagnostic workup for GBS in current clinical practice [5]. The current study shows that children with AFM may fulfill the clinical diagnostic criteria for GBS of a rapidly progressive and bilateral weakness, reduced reflexes in affected limbs, and a monophasic disease course. In addition, patients with AFM may have the cytoalbuminologic dissociation in CSF and in half of the cases have an axonal pattern in NCS that may be misclassified as the acute motor axonal neuropathy subtype of GBS. The implication of these findings for clinical practice is that when AFM is not excluded by conducting MRI and virology, these patients may be falsely diagnosed with GBS.

The Brighton classification requires the exclusion of other causes, but without specifying which other causes need to be excluded in which patients. Importantly, there is only a short time window early in the disease course when AFM can be accurately excluded by performing MRI and virological PCR testing to prove an infection with EV‐D68 or EV‐A71. These investigations can, however, be inconclusive and lose their diagnostic sensitivity later in the disease course [15, 22]. Serological testing may indicate a previous enterovirus infection, but the subtype cannot be determined [22]. By the time of receiving the results of the NCS showing an axonal neuropathy or lack of recovery, it may be too late to exclude the diagnosis of AFM. Therefore, we recommend considering the diagnosis of AFM early in the disease course of patients suspected of GBS, especially if they present with a rapidly progressive or asymmetric limb weakness or lack of sensory deficits or a CSF pleocytosis. Prompt diagnostic studies should then be performed, including CSF investigations, MRI of the brain and spinal cord, and adequate virological testing, particularly on respiratory material.

Differentiation of AFM and GBS is important for several reasons. First, accurate diagnosis is important for informing patients and relatives about the expected prognosis and preparing patients for rehabilitation. The current study demonstrates the substantial difference in clinical course and outcome, which is much worse in AFM than GBS, in accordance with previous studies investigating the outcome either in AFM [23, 24, 25] or GBS [18, 19]. Second, accurate diagnosis is important to start and develop targeted treatment of AFM and GBS. At present, proven effective treatments for GBS are intravenous immunoglobulins (IVIg) or plasma exchange, although these require further confirmatory studies. Although there is no proven effective treatment available for AFM yet, most patients are treated with IVIg, which might have a beneficial effect early in the disease course. Steroids were associated with a deterioration of motor symptoms in the mouse model of AFM [26, 27, 28]. Third, AFM and GBS may both occur during outbreaks, and to be able to monitor the background incidence rates accurate diagnosis is essential.

Our study has several strengths. First, we included two well‐described cohorts of children with either AFM or GBS, which are compatible with reports in literature regarding their clinical features, especially with respect to those features that were found to be discriminative between both conditions. Second, both cohorts are among the largest pediatric cohorts of AFM and GBS described in literature. Third, the AFM cohort included only EV‐D68‐positive cases, leading to a more certain diagnosis of AFM and improving the homogeneity of the AFM cohort.

On the other hand, the selection of EV‐D68‐positive cases could also be seen as a limitation, as it may lead to a selection bias. The phenotype of AFM with a proven EV‐68 infection may be more severe than AFM associated with other viruses or AFM without a proven viral infection [16]. For example, patients with AFM associated with EV‐A71 have an earlier onset of weakness after the prodromal syndrome, milder weakness, more rapid improvement, and a higher chance of full recovery, compared to patients with EV‐D68‐associated disease [29]. This could indicate that our results are not generalizable to AFM caused by other infectious agents. However, the similarities in clinical features and ancillary investigations between our cohort of AFM patients and larger cohorts described in literature suggest that the observed differences at onset of disease are also valid for the whole group of AFM patients. The poor prognosis of AFM in comparison with GBS in children observed in the current study, however, may be influenced by a selection bias toward more severe cases of AFM.

Further limitations include a selection bias by inclusion of cases matching current criteria for AFM and GBS, making some differences between the groups obvious. For example, as MRI abnormalities in the spinal cord are required for the diagnosis of AFM and only a limited number of children with GBS underwent MRI, it is not surprising that these abnormalities are more often found in the AFM group. However, we consider that this does not hinder the finding of differentiating features, which was the main purpose of this study. The identification of AFM patients by sending questionnaires to clinicians and microbiologists could lead to an overrepresentation of severe cases. Therefore, the outlined differences in outcome between AFM and GBS may be an overestimation of the true differences. Nonetheless, the available follow‐up data on AFM show persistence of significant neurological deficits after 1 year, supporting the authenticity of the found differences [17, 24, 25]. The limited group size, predominantly in the AFM group, hinders multivariate analysis. The recommendations made are based on the differentiating features between AFM and GBS, and they are not specific for the differentiation between AFM and other conditions, such as transverse myelitis. Furthermore, the recommendations for clinical differentiation and diagnostic studies are not externally validated. This will be necessary to confirm the validity of these recommendations.

CONCLUSIONS

A child with acute onset flaccid weakness may pose a diagnostic challenge for clinicians, with both AFM and GBS included in the differential diagnosis. We provide distinguishing features and recommendations, which may help clinicians in making the right diagnosis.

Diagnostic criteria for AFM and GBS usually perform well in children. However, in cases of atypical GBS, the diagnosis of AFM needs to be excluded early in the disease course, as AFM may fulfill the current clinical, CSF, and NCS diagnostic criteria for GBS.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

M.C.d.W. has received honoraria paid to her institution by Novartis for serving on a steering committee and presenting at a conference, and has received research funding from the Epilepsiefonds (Dutch Epilepsy Foundation), Hersenstichting, and Sophia Foundation. B.C.J. has received funding for travel from Baxter International, and has received research funding from the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development, Erasmus MC, Prinses Beatrix Spierfonds, Stichting Spieren voor Spieren, CSL‐Behring, Grifols, Annexon, Hansa Biopharma, and the GBS‐CIDP Foundation International. None of the other authors has any conflict of interest to disclose.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Jelte Helfferich: Formal analysis (equal), investigation (equal), methodology (equal), writing–original draft (equal), writing–review & editing (equal). Joyce Roodbol: Formal analysis (equal), investigation (equal), methodology (equal), writing–original draft (equal), writing–review & editing (equal). Marie‐Claire de Wit: Writing–review & editing (equal). Oebele F. Brouwer: Conceptualization (equal), supervision (equal), writing–review & editing (equal). Bart C. Jacobs: Conceptualization (equal), supervision (lead), writing–review & editing (lead).

Supporting information

APPENDIX 1.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

| Name | Location | Contribution |

|---|---|---|

| Jelte Helfferich, MD | University of Groningen, Groningen, the Netherlands | Acquisition and analysis of the data; drafted the manuscript |

| Joyce Roodbol, MD | University Medical Center Rotterdam, Rotterdam, the Netherlands | Acquisition and analysis of the data; drafted the manuscript |

| Marie‐Claire de Wit, MD, PhD | University Medical Center Rotterdam, Rotterdam, the Netherlands | Revised the manuscript for intellectual content |

| Oebele F. Brouwer | University of Groningen, Groningen, the Netherlands | Designed the study, revised the manuscript, and supervised the analysis of the data and writing of the manuscript |

| Bart C. Jacobs | University Medical Center Rotterdam, Rotterdam, the Netherlands | Designed the study, revised the manuscript, and supervised the analysis of the data and writing of the manuscript |

APPENDIX 2.

COINVESTIGATORS

2016 Enterovirus D68 Acute Flaccid Myelitis Working Group

| Name | Location | Contribution |

|---|---|---|

| Stephan W. Aberle, MD | Medical University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria | Acquisition of the data |

| Theresia Popow‐Kraupp, MD | Medical University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria | Acquisition of the data |

| Lubomira Nikolaeva‐Glomb, MD, PhD | National Center of Infectious and Parasitic Diseases, Sofia, Bulgaria | Acquisition of the data |

| Petra Rainetova | National Reference Laboratory for Enteroviruses, Prague, Czech Republic | Acquisition of the data |

| Sofie Midgley, PhD | Statens Serum Institute, Copenhagen, Denmark | Acquisition of the data |

| Thea Kølsen Fischer, MD, PhD | Statens Serum Institute, Copenhagen, Department of Public Health, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen and Nordsjaellands Hospital, Hillerød, Denmark | Acquisition of the data |

| Grethel Simonlatser | Laboratory of Communicable Diseases, Tallinn, Estonia | Acquisition of the data |

| Carita Savolainen‐Kopra, PhD | National Institute for Health and Welfare, Helsinki, Finland | Acquisition of the data |

| Bruno Lina, MD, PhD | National Reference Center for Enteroviruses and Parechoviruses, Hospices Civils de Lyon, Lyon, France | Acquisition of the data |

| Isabelle Schuffenecker, MD, PhD | National Reference Center for Enteroviruses and Parechoviruses, Hospices Civils de Lyon, Lyon, France | Acquisition of the data |

| Melodie Aubart, MD, PhD | Necker‐Enfants Malades University Hospital, Paris, France | Acquisition of the data |

| Cyril Gitiaux, MD, PhD | Necker‐Enfants Malades University Hospital, Paris, France | Acquisition of the data |

| Denise Antona, MD | Santé publique France, Saint‐Maurice, France | Acquisition of the data |

| Anna Maria Eis‐Hübinger, MD, PhD | University of Bonn Medical Center, Bonn, Germany | Acquisition of the data |

| Stephan Buderus, MD | GFO Kliniken Bonn, St. Marien‐Hospital, Bonn, Germany | Acquisition of the data |

| Marcus Panning, MD | Institute for Virology, Medical Center–University of Freiburg, Faculty of Medicine, University of Freiburg, Freiburg, Germany | Acquisition of the data |

| Markus Nowotny, MD | University Medical Center of the Johannes Gutenberg University, Mainz, Germany | Acquisition of the data |

| Lisa Kiechle, MD | University Medical Center of Johannes Gutenberg University, Mainz, Germany | Acquisition of the data |

| Sindy Böttcher, PhD | Robert Koch Institute, Berlin, Germany | Acquisition of the data |

| Mária Takács, PhD | National Public Health Institute, Budapest, Hungary | Acquisition of the data |

| Ágnes Farkas, PhD | National Public Health Institute, Budapest, Hungary | Acquisition of the data |

| Arthur Löve, MD, PhD | National University Hospital Reykjavik, Reykjavik, Iceland | Acquisition of the data |

| Fausto Baldanti, MD, PhD | University of Pavia, Pavia, Italy | Acquisition of the data |

| Maria Rosaria Capobianchi, PhD | Lazzaro Spallanzani National Institute for Infectious Diseases, Rome, Italy | Acquisition of the data |

| Maria Beatrice Valli | Lazzaro Spallanzani National Institute for Infectious Diseases, Rome, Italy | Acquisition of the data |

| Susanna Esposito, MD | Pediatric Clinic, Università degli Studi di Perugia, Perugia, Italy | Acquisition of the data |

| Elena Pariani, PhD | University of Milan, Milan, Italy | Acquisition of the data |

| Sandro Binda, PhD | University of Milan, Milan, Italy | Acquisition of the data |

| Rinze Neuteboom, MD, PhD | Erasmus Medical Center, Rotterdam, the Netherlands | Acquisition of the data |

| Suzan Pas, PhD | Microvida, Roosendaal, the Netherlands | Acquisition of the data |

| Kimberley Benschop, PhD | National Institute for Public Health and the Environment, Bilthoven, the Netherlands | Acquisition of the data |

| Adam Meijer, PhD | National Institute for Public Health and the Environment, Bilthoven, the Netherlands | Acquisition of the data |

| Svein Arne Nordbø, MD | Department of Medical Microbiology, St. Olav's Hospital, Trondheim University Hospital and Department of Clinical and Molecular Medicine, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Trondheim, Norway | Acquisition of the data |

| Maria Hafstrøm, MD, PhD | Department of Pediatrics, St. Olav's Hospital, Trondheim University Hospital and Department of Clinical and Molecular Medicine, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Trondheim, Norway | Acquisition of the data |

| Susanne Gjeruldsen Dudman, MD, PhD |

|

Acquisition of the data |

| Helle Cecilie Viekilde Pfeiffer, MD, PhD | Oslo University Hospital, Oslo, Norway and Copenhagen University Hospital, Hvidovre, Denmark | Acquisition of the data |

| Raquel Guiomar | National Influenza and Other Respiratory Viruses Reference Laboratory, National Institute of Health Dr Ricardo Jorge, Lisbon, Portugal | Acquisition of the data |

| Paula Palminha | Laboratory of Vaccine Preventable Diseases, National Institute of Health Dr Ricardo Jorge, Lisbon, Portugal | Acquisition of the data |

| Inês Costa | National Influenza and Other Respiratory Viruses Reference Laboratory, National Institute of Health Dr Ricardo Jorge, Lisbon, Portugal | Acquisition of the data |

| Andrea Sofia Dias | Pediatric Intensive Care, Hospital Pediátrico de Coimbra, Centro Hospitalar e Universitário de Coimbra, Coimbra, Portugal | Acquisition of the data |

| Cristina Tecu, MD, PhD | National Institute for Medical‐Military Research and Development "Cantacuzino," Bucharest, Romania | Acquisition of the data |

| Carmen Maria Cherciu | National Institute for Medical‐Military Research and Development "Cantacuzino," Bucharest, Romania | Acquisition of the data |

| Ivana Lazarevic, MD, PhD | Institute of Microbiology and Immunology, Faculty of Medicine, University of Belgrade, Belgrade, Serbia | Acquisition of the data |

| Svetlana Filipović‐Vignjević, MD | Institute of Virology, Vaccines, and Sera "Torlak," Belgrade, Serbia | Acquisition of the data |

| Natasa Berginc | National Laboratory of Health, Environment, and Food, Ljubljana, Slovenia | Acquisition of the data |

| Mónica Gozalo Margüello | Marqués de Valdecilla University Hospital, Santander, Spain | Acquisition of the data |

| María Cabrerizo, PhD | Spanish National Poliovirus Laboratory, Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Madrid, Spain | Acquisition of the data |

| Juan Pablo García Iñiguez, MD, PhD | Pediatric Intensive Care Unit, Miguel Servet Children's Hospital, Zaragoza, Spain | Acquisition of the data |

| Sonia Perez Castro | University Hospital of Vigo and Inflammatory and Infectious Diseases & Immune Disorders Group, Galicia Sur Health Research Institute, Vigo, Spain | Acquisition of the data |

| Carlos Rodrigo, MD, PhD | Vall d'Hebron University Hospital and Autonomous University of Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain | Acquisition of the data |

| Andrés Antón, PhD | Vall d'Hebron University Hospital, Barcelona, Spain | Acquisition of the data |

| Núria Rabella Garcia, MD, PhD | Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain | Acquisition of the data |

| Robert Dyrdak | Karolinska Institute and Karolinska University Hospital, Stockholm, Sweden | Acquisition of the data |

| Jan Albert, MD, PhD | Karolinska Institute and Karolinska University Hospital, Stockholm, Sweden | Acquisition of the data |

| Rolf Kramer, PhD | European Public Health Microbiology Training Program (EUPHEM), European Center for Disease Prevention and Control, Stockholm, Sweden | Acquisition of the data |

| Sybil Stacpoole, PhD | Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Cambridge, UK | Acquisition of the data |

| Rhys Thomas, MD | Newcastle University, Newcastle, UK | Acquisition of the data |

| Niamh O'Flaherty, MD | National Virus Reference Laboratory, University Center Dublin, Dublin, Ireland | Acquisition of the data |

| Richard Drew, MD | Rotunda Hospital and Temple Street Children's University Hospital, Dublin, Ireland | Acquisition of the data |

| Kate Templeton, PhD | Royal Hospital for Sick Children, Edinburgh, UK | Acquisition of the data |

| Catherine McDougall, MD, PhD | Royal Hospital for Sick Children, Edinburgh, UK | Acquisition of the data |

| Paul Eunson, MD | Royal Hospital for Sick Children, Edinburgh, UK | Acquisition of the data |

| Nandita Chinchankar | Royal Hospital for Sick Children, Edinburgh, UK | Acquisition of the data |

| Jay Shetty, MD, PhD | Royal Hospital for Sick Children, Edinburgh, UK | Acquisition of the data |

| Catherine Moore, PhD | Public Health Wales, Cardiff, Wales, UK | Acquisition of the data |

| Christopher Williams, PhD | Public Health Wales, Cardiff, UK | Acquisition of the data |

| Marjolein Knoester, MD, PhD | University Medical Center Groningen, Groningen, the Netherlands | Acquisition of the data |

| Randy Poelman | University Medical Center Groningen, Groningen, the Netherlands | Acquisition of the data |

| Coretta van Leer‐Buter, MD, PhD | University Medical Center Groningen, Groningen, the Netherlands | Acquisition of the data |

| Bert Niesters, PhD | University Medical Center Groningen, Groningen, the Netherlands | Acquisition of the data |

Dutch Pediatric GBS Study Group

| Name | Location | Contribution |

|---|---|---|

| Marc Engelen, MD, PhD | Children's Hospital–Academic Medical Center, Amsterdam, the Netherlands | Acquisition of the data |

| Corrie E. Erasmus, MD, PhD | Amalia Children's Hospital–Radboud University Medical Center, Nijmegen, the Netherlands | Acquisition of the data |

| Karin Geleijns, MD, PhD | Wilhelmina Children's Hospital–University Medical Center Utrecht, Utrecht, the Netherlands | Acquisition of the data |

| Irene A. W. Kotsopoulos, MD, PhD | Amphia Hospital, Breda, the Netherlands | Acquisition of the data |

| Joost Nicolai, MD, PhD | Maastricht University Medical Center, Maastricht, the Netherlands | Acquisition of the data |

| Jikke‐Mien F. Niermeijer, MD, PhD | Elisabeth Tweesteden Hospital, Tilburg, the Netherlands | Acquisition of the data |

| Erik H. Niks, MD, PhD | Leiden University Medical Center, Leiden, the Netherlands | Acquisition of the data |

| Johnny P. A. Samijn, MD | Maasstad Hospital, Rotterdam, the Netherlands | Acquisition of the data |

Helfferich J, Roodbol J, de Wit M‐C, Brouwer OF, Jacobs BC; the 2016 Enterovirus D68 Acute Flaccid Myelitis Working Group and the Dutch Pediatric GBS Study Group . Acute flaccid myelitis and Guillain–Barré syndrome in children: A comparative study with evaluation of diagnostic criteria. Eur J Neurol.2022;29:593–604. doi: 10.1111/ene.15170

Jelte Helfferich and Joyce Roodbol contributed equally to this article.

The 2016 Enterovirus D68 Acute Flaccid Myelitis Working Group and the Dutch Pediatric GBS Study Group members are listed in Appendix 2.

Funding information

The Prinses Beatrix Spierfonds funded the PhD project of J.R. on GBS in children (project number: W.OR12‐04)

Contributor Information

Bart C. Jacobs, Email: b.jacobs@erasmusmc.nl.

the 2016 Enterovirus D68 Acute Flaccid Myelitis Working Group and the Dutch Pediatric GBS Study Group:

Stephan W. Aberle, Theresia Popow‐Kraupp, Lubomira Nikolaeva‐Glomb, Petra Rainetova, Sofie Midgley, Thea Kølsen Fischer, Grethel Simonlatser, Carita Savolainen‐Kopra, Bruno Lina, Isabelle Schuffenecker, Melodie Aubart, Cyril Gitiaux, Denise Antona, Anna Maria Eis‐Hübinger, Stephan Buderus, Marcus Panning, Markus Nowotny, Lisa Kiechle, Sindy Böttcher, Mária Takács, Ágnes Farkas, Arthur Löve, Fausto Baldanti, Maria Rosaria Capobianchi, Maria Beatrice Valli, Susanna Esposito, Elena Pariani, Sandro Binda, Rinze Neuteboom, Suzan Pas, Kimberley Benschop, Adam Meijer, Svein Arne Nordbø, Maria Hafstrøm, Susanne Gjeruldsen Dudman, Helle Cecilie Viekilde Pfeiffer, Raquel Guiomar, Paula Palminha, Inês Costa, Andrea Sofia Dias, Cristina Tecu, Carmen Maria Cherciu, Ivana Lazarevic, Svetlana Filipović‐Vignjević, Natasa Berginc, Mónica Gozalo Margüello, María Cabrerizo, Juan Pablo García Iñiguez, Sonia Perez Castro, Carlos Rodrigo, Andrés Antón, Núria Rabella Garcia, Robert Dyrdak, Jan Albert, Rolf Kramer, Sybil Stacpoole, Rhys Thomas, Niamh O'Flaherty, Richard Drew, Kate Templeton, Catherine McDougall, Paul Eunson, Nandita Chinchankar, Jay Shetty, Catherine Moore, Christopher Williams, Marjolein Knoester, Randy Poelman, Coretta van Leer‐Buter, Bert Niesters, Marc Engelen, Corrie E. Erasmus, Karin Geleijns, Irene A. W. Kotsopoulos, Joost Nicolai, Jikke‐Mien F. Niermeijer, Erik H. Niks, and Johnny P. A. Samijn

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

J.H. and J.R. had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

REFERENCES

- 1. Williams CJ, Thomas RH, Pickersgill TP, et al. Cluster of atypical adult Guillain‐Barre syndrome temporally associated with neurological illness due to EV‐D68 in children, South Wales, United Kingdom, October 2015 to January 2016. Euro Surveill Bull Eur Mal Transm Eur Commun Dis Bull. 2016;21(4):26‐32. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2016.21.4.30119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. CSTE . Revision to the standardized case definition, case classification, and Public Health Reporting for Acute Flaccid Myelitis.

- 3. Elrick MJ, Gordon‐Lipkin E, Crawford TO, et al. Clinical subpopulations in a sample of North American Children diagnosed with acute flaccid myelitis, 2012–2016. JAMA Pediatr. 2019;173(2):134‐139. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.4890 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kramer R, Lina B, Shetty J. Acute flaccid myelitis caused by enterovirus D68: Case definitions for use in clinical practice. Eur J Paediatr Neurol EJPN Eur Paediatr Neurol Soc. 2019;23(2):235‐239. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpn.2019.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sejvar JJ, Kohl KS, Gidudu J, et al. Guillain‐Barré syndrome and Fisher syndrome: case definitions and guidelines for collection, analysis, and presentation of immunization safety data. Vaccine. 2011;29(3):599‐612. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Asbury AK, Cornblath DR. Assessment of current diagnostic criteria for Guillain‐Barre syndrome. Ann Neurol. 1990;27(Suppl):S21‐S24. doi: 10.1002/ana.410270707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Knoester M, Helfferich J, Poelman R, et al. Twenty‐nine cases of enterovirus‐D68‐associated acute flaccid myelitis in Europe 2016: a case series and epidemiologic overview. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2019;38(1):16‐21. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000002188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. CSTE . Acute Flaccid Myelitis (AFM) 2018 Case Definition.

- 9. Roodbol J, de Wit M‐CY, van den Berg B, et al. Diagnosis of Guillain‐Barré syndrome in children and validation of the Brighton criteria. J Neurol. 2017;264(5):856‐861. doi: 10.1007/s00415-017-8429-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jacobs BC, van den Berg B, Verboon C, et al. International Guillain‐Barré Syndrome Outcome Study: protocol of a prospective observational cohort study on clinical and biological predictors of disease course and outcome in Guillain‐Barré syndrome. J Peripher Nerv Syst. 2017;22(2):68‐76. doi: 10.1111/jns.12209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Roodbol J, de Wit MCY, Walgaard C, de Hoog M, Catsman‐Berrevoets CE, Jacobs BC. Recognizing Guillain‐Barre syndrome in preschool children. Neurology. 2011;76(9):807‐810. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31820e7b62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hadden RD, Cornblath DR, Hughes RA, et al. Electrophysiological classification of Guillain‐Barré syndrome: clinical associations and outcome. Plasma Exchange/Sandoglobulin Guillain‐Barré Syndrome Trial Group. Ann Neurol. 1998;44(5):780‐788. doi: 10.1002/ana.410440512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hughes RA, Newsom‐Davis JM, Perkin GD, Pierce JM. Controlled trial prednisolone in acute polyneuropathy. Lancet (London, England). 1978;2(8093):750‐753. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(78)92644-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kahlmann V, Roodbol J, van Leeuwen N, et al. Validated age‐specific reference values for CSF total protein levels in children. Eur J Paediatr Neurol EJPN Eur Paediatr Neurol Soc. 2017;21(4):654‐660. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpn.2017.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Messacar K, Schreiner TL, Van HK, et al. Acute flaccid myelitis: a clinical review of US cases 2012–2015. Ann Neurol. 2016;80(3):326‐338. doi: 10.1002/ana.24730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chong PF, Kira R, Mori H, et al. Clinical features of acute flaccid myelitis temporally associated with an enterovirus D68 outbreak: results of a Nationwide Survey of Acute Flaccid Paralysis in Japan, August‐December 2015. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;66(5):653‐664. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix860 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Yea C, Bitnun A, Robinson J, et al. Longitudinal outcomes in the 2014 acute flaccid paralysis cluster in Canada. J Child Neurol. 2017;32(3):301‐307. doi: 10.1177/0883073816680770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Korinthenberg R, Schessl J, Kirschner J. Clinical presentation and course of childhood Guillain‐Barre syndrome: a prospective multicentre study. Neuropediatrics. 2007;38(1):10‐17. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-981686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bradshaw DY, Jones HRJ. Guillain‐Barre syndrome in children: clinical course, electrodiagnosis, and prognosis. Muscle Nerve. 1992;15(4):500‐506. doi: 10.1002/mus.880150415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ye Y‐Q, Wang K‐R, Sun L, Wang Z. Clinical and electrophysiologic features of childhood Guillain‐Barre syndrome in Northeast China. J Formos Med Assoc. 2014;113(9):634‐639. doi: 10.1016/j.jfma.2012.08.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Murphy OC, Messacar K, Benson L, et al. Acute flaccid myelitis: cause, diagnosis, and management. Lancet (London, England). 2021;397(10271):334‐346. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32723-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Schubert RD, Hawes IA, Ramachandran PS, et al. Pan‐viral serology implicates enteroviruses in acute flaccid myelitis. Nat Med. 2019;25(11):1748‐1752. doi: 10.1038/s41591-019-0613-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Roodbol J, de Wit M‐CY, Aarsen FK, Catsman‐Berrevoets CE, Jacobs BC. Long‐term outcome of Guillain‐Barré syndrome in children. J Peripher Nerv Syst. 2014;19(2):121‐126. doi: 10.1111/jns5.12068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kirolos A, Mark K, Shetty J, et al. Outcome of paediatric acute flaccid myelitis associated with enterovirus D68: a case series. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2018;61(3):376‐380. doi: 10.1111/dmcn.14096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Martin JA, Messacar K, Yang ML, et al. Outcomes of Colorado children with acute flaccid myelitis at 1 year. Neurology. 2017;89(2):129‐137. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000004081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hughes RAC, Swan AV, van Doorn PA. Intravenous immunoglobulin for Guillain‐Barré syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;2014(9):CD002063. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002063.pub6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hixon AM, Clarke P, Tyler KL. Evaluating treatment efficacy in a mouse model of enterovirus D68‐associated paralytic myelitis. J Infect Dis. 2017;216(10):1245‐1253. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jix468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hopkins SE, Elrick MJ, Messacar K. Acute flaccid myelitis‐keys to diagnosis, questions about treatment, and future directions. JAMA Pediatr. 2018;173(2):117. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.4896 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Messacar K, Spence‐Davizon E, Osborne C, et al. Clinical characteristics of enterovirus A71 neurological disease during an outbreak in children in Colorado, USA, in 2018: an observational cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20(2):230‐239. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(19)30632-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article, within the limits of the General Data Protection Regulation privacy regulations.

J.H. and J.R. had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.