Abstract

Objective

To explore the current practice and perceptions of health visitors in supporting multiple birth families.

Design and sample

Practicing health visitors across the United Kingdom were invited to complete a cross‐sectional, descriptive, online survey. The questionnaire covered multiple birth caseload, education received about multiples and the experience of working with families. Two‐hundred and ninety health visitors completed the questionnaire. Descriptive and inferential statistics were used for analysis of the quantitative components and thematic analysis for the qualitative data.

Results

Most health visitors had twins on their current workload. Most health visitors had not received any specific training or continuing professional development regarding the needs of multiple birth families. Supporting the families within the confines of reduced time and increased workload was challenging. Daily tasks of caring for multiples were the main areas that health visitors and parents wanted more information about.

Conclusions

In the United Kingdom, health visitors are uniquely positioned to support multiple birth families, in particular during the more challenging early years. However, the findings of this study suggest that many health visitors are aware that the care and support that they are able to provide multiple birth families falls short of meeting their needs

Keywords: families, health visiting, multiple births, parents, public health nursing, triplets, twins

1. INTRODUCTION

In the United Kingdom (UK), health visitors are registered nurses / midwives with a post‐graduate community health qualification. They are public health practitioners who work with families with children under 5 years of age offering support, guidance and early intervention through the Healthy Child Program (Department of Health, 2009). Within their family support role, health visitors are uniquely positioned to work with multiple birth families, promoting wellbeing and facilitating referral for ongoing support (Hamill, 2014; Harvey et al., 2014). This ongoing support is becoming increasingly imperative with the rise in the rates of multiple births (twins, triplets and higher order multiples) in the United Kingdom over the last 40 years to approximately 15 per 1000 maternities (Office for National Statistics, 2020). This pattern is seen globally with the increased use of medically assisted reproduction being the major cause of the global increase in multiple births (Fell & Joseph, 2012; Monden et al., 2021).

Advancements in specialist antenatal care and subsequent survival of premature infants are contributory factors to the increase in the number of multiple birth families. As parents adjust to family life and caring for two or more babies, who may have been born prematurely, they are faced with many social, emotional, practical, and economic challenges. (Harvey et al., 2014) Pregnancy and the transition to parenthood are widely recognized as critical time periods that will influence longer term outcomes for infants and their families (Department of Health & Social Care, 2021). Multiple birth families require health and social care practitioners who are both knowledgeable and responsive and are able to adapt and lead in the provision of high quality, individualized care, and support (Jena et al., 2011; Nurse & Kenner, 2011; Ooki & Hiko, 2012)

Multiple births present an increased risk of complications for the mother and her babies, which can affect family life and wellbeing. Multiple birth pregnancies can result in maternal complications such as hypertension, gestational diabetes, anxiety, and depression (Dodd et al., 2015; El‐Toukhy et al., 2018) which may extend into the postnatal period (Ooki & Hiko, 2012). Anxiety and depression experienced by multiple birth parents can be detrimental to parenting behaviors and child development (Bryan, 2003; Domato, 2005). Mothers of multiples often feel isolated and there is a higher divorce rate in multiple birth families (Bryan, 2003; Jena et al., 2011).

Many multiples are born preterm (before 37 completed weeks) (NICE, 2019). Consequently, parents are often unable to attend antenatal classes (Redshaw et al., 2011) so they may be less prepared for parenthood. Prematurity can have an adverse impact on adaptation to family life, particularly if one baby is discharged home before the other(s). Breast feeding rates for multiples are lower than for singletons (Ostlund et al., 2010; Whitford et al., 2017). The incidence of cerebral palsy is higher for multiples than for singletons. There is a higher incidence of developmental delay and autistic spectrum disorder compared to singletons (Shinwell et al., 2009). The impact of these difficulties on family life is apparent irrespective of them being present in only one of the children (Bryan, 2003).

Multiple birth children are often seen as “one unit” by both the family and society more widely. The resulting lack of individuality and identify can inhibit early child development with potential longer‐term consequences affecting their relationship with each other and their own emotional wellbeing (Bryan, 2003). The needs of other children in the family can be neglected. Siblings may display regressive and attention‐seeking behaviors (Bryan, 2003; Harvey et al., 2014; Scoats et al., 2018). In addition, there is a higher incidence of child abuse in multiple birth families (Bryan, 2003). Bereavement can have an impact on family‐wellbeing. Multiple pregnancies account for higher numbers of perinatal deaths compared to singletons (Montacute & Bunn, 2016; Office for National Statistics, 2020). This means parents may be grieving for one baby whilst caring for the survivor(s) (Expert Group on Multiple Births after IVF, 2006).

Adapting to parenthood and caring for two (or more) children of the same age presents parents with physical, emotional, practical, and economic challenges (El‐Toukhy et al., 2018; Heinonen, 2015; Leonard & Denton, 2006) and the first year can be particularly difficult (Harvey et al., 2014). Multiple birth parents want information and emotional support on all aspects of childcare including guidance on feeding, sleeping, and coping with behavioral problems from knowledgeable health visitors (Hamill, 2014; Harvey et al., 2014; Jenkins & Coker, 2010). Whilst most parents need advice and support on the transition to parenthood and caring for their infants, this is particularly the case for parents of multiples. The exact nature of this care and support should be tailored to meet individual needs to ensure it is effective (Donetto & Maben, 2014; Heinonen, 2016; Redshaw et al., 2011). However, the support provided by health visitors is variable and often does not meet the needs of multiple birth families (Harvey et al., 2014; Scoats et al., 2018). Few health visiting teams in the United Kingdom have a “multiple births champion” or “multiple births care pathway” (Hamill, 2014). Furthermore, there is a lack of guidance or standards in the United Kingdom for healthcare professionals generally and health visitors in particular on the longer‐term care and support needs of multiple birth families. The extent to which the needs of these families are currently addressed in health visiting curricula and professional development is unknown.

There has been limited research involving healthcare professionals generally (Heinonen, 2016) and health visitors specifically to explore their experiences supporting multiple birth families. In order to develop evidence based multiple birth services it is important to understand the health visitor perspective and the challenges they face. Workload pressures can sometimes negatively impact on their role (Alamad et al., 2018; Donetto & Maben, 2014) and it is likely that supporting multiple birth families adds to their workload, especially given the challenges that families face.

The need for research to facilitate the provision of evidence‐based care by health visitors for multiple birth families has been identified (Harvey et al., 2014; Scoats et al., 2018; Wenze et al., 2015). More broadly, contemporary evidence is required to support the development of policy, health visiting education and service provision to provide effective, individualized care and support for multiple birth families (Alamad et al., 2018; Harvey et al., 2014). To this end, our study provides evidence of the current practice, education and continuing professional development of health visitors working in the United Kingdom with multiple birth families.

2. METHODS

2.1. Study design

The aim of the study was to establish an evidence base of health visitor experiences and perceptions in supporting multiple birth families.

The study objectives were:

To explore the current practice of health visitors supporting multiple birth families.

To explore the nature and extent of education and professional development received by health visitors about supporting multiple birth families.

To inform health visitor practice to improve the provision of care and support to multiple birth families.

In order to meet the aim and objectives, we undertook a cross‐sectional, descriptive, online survey of health visitors. This approach was chosen as it enabled us to collect quantitative and qualitative data from a large number of participants over a wide geographical area. The approach is cost‐effective and time‐efficient for the participants with fewer ethical implications in comparison to other research methods (Harvey & Land, 2017)

2.2. Sample and recruitment

Purposive sampling was used to ensure that we recruited participants for whom the study aim would be meaningful (Harvey & Land, 2017). The inclusion criteria for the study were health visitors who were practicing in the United Kingdom as they would be able to provide the necessary perspective on the phenomenon under study (Silverman, 2014). Health visitors who were no longer practicing or were outside of the United Kingdom were excluded as we wanted to gain insight into current practices within the United Kingdom.

The sample size was determined based on the reported numbers of practicing health visitors in May 2019. At that time, there were 8100 health visitors working for NHS England, 1357 health visitors in Scotland (Merrifield, 2017), 876 in Wales (Sherwood, 2019), and 526 in Northern Ireland (Department of Health, 2019). The research team statistician identified an optimum sample size of 300 participants to provide a 5% margin of error. The participants were recruited through professional networks and social media linked to professional groups. Subsequently, the survey yielded 290 usable questionnaires.

2.3. Ethical considerations

The study was approved by a university ethics committee. “Online Surveys” was chosen as the platform for distribution which is compliant with all UK data protection laws (see https://www.onlinesurveys.ac.uk/) The link to the survey and the participation information leaflet were hosted on a university website. On accessing the survey but before completing the questionnaire, potential participants were required to tick boxes to indicate their consent to participate. No participant personal information was required for the survey apart from date of qualification and the type of geographical location of their practice (e.g., inner city or rural). Each participant was allocated a randomly generated 4‐digit identity number. The confidentiality of all data was ensured in accordance with the university policy. Although it was considered unlikely that the survey would cause the participants distress, potential sources of support were identified in the information leaflet.

At the end of the questionnaire, participants could opt in to enter a prize draw for a £30.00 shopping voucher. Details were provided in the information leaflet and in the final section of the survey. In order to enter, the participants needed to provide their work email which was securely stored following university policy and destroyed once the draw had taken place.

2.4. Data collection

The use of an online survey enabled us to access a large number of practicing health visitors across the United Kingdom who were working with a diverse selection of families within different communities. This allowed us to gain an understanding of the variations in current practice in supporting multiple birth families. The questionnaire was developed based on the findings of an exploratory focus group study of health visitors from the West Midlands (a mainly urban and ethnically diverse region) conducted by members of the research team in 2017–2018 (Alamad et al., 2018). The survey was piloted with eight local health visitors and minor changes made. The pilot demonstrated that the questionnaire took between 10 and 15 min to complete.

The questionnaire consisted mostly of closed questions and Likert scales to enable collection of quantitative data. Open questions were included to capture more detailed qualitative data about the experiences of participants. There were 37 questions in total.

It was distributed via “Online Surveys” (www. onlinesurveys.ac.uk) which is commonly used by academic researchers in UK higher education institutions. The survey was launched in 2019 and open to participants for 17 weeks. One reminder was sent.

The questions in the survey related to:

Participant demographic information such as date qualified as a health visitor, case load, number of multiple birth families on their case load, county and type of location of practice (inner city, town or rural). Information about participant names, ages, gender and exact location of work was not requested.

Participant perceptions of the needs and challenges faced by multiple birth families.

The challenges that participants encounter when supporting multiple birth families.

The nature and extent of any educational or professional development the participants had received about supporting multiple birth families.

Participant identification of any continuing professional development (e.g., study days, accredited modules, workshops etc.) they felt they needed about supporting multiple birth families.

2.5. Data analysis

The quantitative data were analyzed using descriptive statistics and appropriate statistical tests to explore potential correlations. Analysis was based on chi‐square testing of the response variables as a function of health visitor experience. Experience was measured by time spent practicing as a health visitor (excluding periods of maternity / sick / unpaid leave) and was dichotomized into less than versus more than 5 years’ experience, which was chosen to give the most even split. An initial inspection of the data identified five topics for statistical investigation:

The positive aspects of working with multiple birth families

The challenges / difficulties encountered when working with multiple birth families

Aspects of parenting parents of multiples want information / guidance about

Guidance / information / resources which would help when working with multiple birth families

Work outside the health visitor role undertook during visits.

Each topic represents a multiple response question in the survey, with the frequency of each unique response tested for an association with length of time in practice. Multiplicity was corrected for via the Sidak correction, resulting in the reported Sidak‐corrected values with a critical value of 0.05. The quantitative data analysis was led by the research team statistician to ensure accuracy and rigor.

Qualitative data arising from participant responses to the open questions were analyzed thematically by two members of the research team. This is a flexible and widely used approach which, when applied systematically, enhances the trustworthiness and rigor of the study (Nowell et al., 2017). The participant responses to each question were read to ensure familiarity with the content and context. Sections of the responses were coded, with new codes created when the data appeared to capture something different. The codes were then formed into broad themes and where appropriate, subthemes. The nature of the broad themes and subthemes for each question were largely influenced by the characteristics of the original question. However, it was ensured that the broad themes and subthemes reflected the range and breadth of participant responses, irrespective of whether they related to the original question. Once all of the responses had been coded, the coding framework was reviewed and amended for each question. Following the analysis the themes were reviewed by a multiple births specialist and a health visitor.

3. RESULTS

3.1. The participants

In order to practice as a health visitor in the United Kingdom, the participant has to be registered with the Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC) as either a nurse or midwife and have completed an approved Specialist Community Public Health Nurse (SCPHN) program (Nursing & Midwifery Council, 2004). Almost all participants held a nursing qualification with Adult Nursing being the most common (Table 1). Nearly two thirds of the participants (n = 181; 62.84%) had been practicing as a health visitor for 5 years or more. Most participants practiced in a town (n = 172; 49.02%) and most of the participants were from England (Table 2).

TABLE 1.

Primary qualification of participants (N = 290)

| Primary qualification | n (% of participants) |

|---|---|

| Adult nursing | 196 (67.58%) |

| Child nursing | 39 (13.44%) |

| Learning disability nursing | 6 (2.06%) |

| Mental health nursing | 8 (2.75%) |

| No other additional qualifications identified: Health Visitor only | 29 (10%) |

| Midwifery | 12 (4.13%) |

TABLE 2.

Health visitor practice (N = 290)

| Length of time practicing as a health visitor | n |

|---|---|

| Less than 5 years | 107 |

| More than 5 years | 181 |

| Unknown | 2 |

| Practice setting | |

| Rural | 37 |

| Town | 172 |

| Inner city | 76 |

| Unknown | 5 |

| Country of practice | |

| England | 259 |

| Northern Ireland | 1 |

| Scotland | 15 |

| Wales | 14 |

| Unknown | 1 |

3.2. Health visitor multiple birth caseload

At the time of the survey, most of the health visitors had twins on their caseload (250/284, 88.02%). In contrast, 47/278 (16.90%) health visitors had triplets on their caseload and 6/278 (2.15%) had quadruplets. For just over a fifth of the health visitors, the current number of multiples on their case load was less than usual. However, for most of the remainder the number was static (67%).

3.3. Shaping current health visitor multiple birth practice

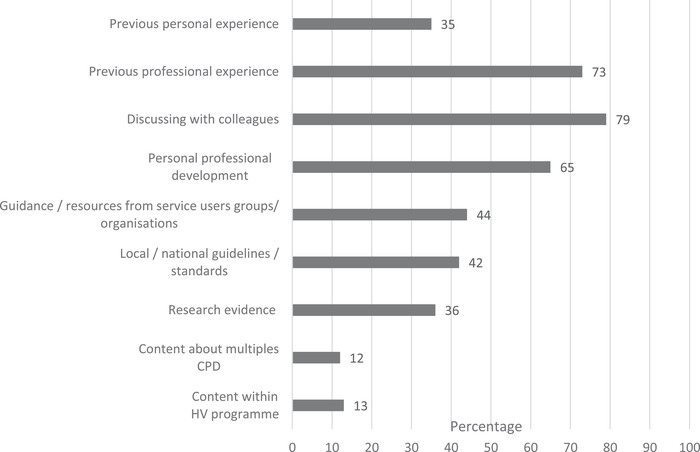

The responses indicated that only 2% of respondents had received one or more specific sessions about multiples during their health visitor program whilst 63% of respondents had received no content. These findings were echoed in relation to continuing professional development with 80% of respondents not attending any sessions related to multiple birth families. Consequently, the respondents relied primarily on “professional experience” (73%) and “discussion with colleagues” (79%) to inform their practice with multiple birth families (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Factors influencing health visitor practice with multiple birth families

The health visitors were asked about their personal experiences of multiples. Nearly half of the respondents did not have any personal experience (47%). Amongst the remaining respondents, 32% had multiples in their immediate and wider family and 12% were parents of multiples.

The health visitors with personal experience of multiples were asked to expand upon the ways in which this impacted on their work with multiple birth families. Whilst some felt their personal experience had no impact on their practice many of the responses related to being able to “understand the challenges” that multiple birth families encounter and the practical and emotional difficulties that they face.

I have greater empathy and can give practical tips. I understand the stress and anxiety involved in parenting multiples, and the guilt of not being able to give exclusive love to one. (7178).

A further theme related to “improving my practice”. The health visitors recounted how their personal experience of multiple birth experiences led them to adapting their practice.

Helped my families past and present with twins find coping techniques, give them hints and tips and advice which is not provided in books or guidance websites which are all singleton orientated. (0691)

In the third theme “promoting individuality of multiple birth children” the health visitors drew on their personal experiences to explain the importance of the children establishing their own identity.

As an identical twin I am aware of the need for twins to have the freedom to develop their own sense of self outside of the relationship. (6168)

3.4. Adapting health visitor practice to support multiple birth families

Although most health visitors had multiple birth families on their caseload, only 5% of their practice areas had a specific care pathway and less than 1% had a “multiple births champion” or lead for multiple births. The health visitors were asked about the accessibility of their clinic‐based health visitor services. 86% of respondents considered their clinic setting to be accessible and the families were able to have appointments that were either concurrent or combined (85%).

During the exploratory focus groups (Alamad et al., 2018), several health visitors voiced concern at how difficult it could be logistically for some multiple birth parents to access clinic‐based health visitor services. However, 86% of respondents in this survey, considered their clinic setting to be accessible and the families were able to have appointments that were either concurrent or combined (85%).

3.5. Health visitor experience working with multiple birth families

The health visitors were asked to identify the most difficult time period for parents of multiples from birth to 60 months. The 0–12 month period was cited as the most challenging by 88% of the health visitors. In contrast, the 49–60 month period which covers the time when children start school was not selected.

The health visitors were asked to consider the positive aspects for them of working with multiple birth families. The most frequent responses were seeing parents’ confidence grow (61%), the development of their own skills and knowledge in relation to multiple births (58%) and experiencing greater continuity of care (48%). There were no significant differences in the positive aspects of working with the families based on the health visitor time in post. Using the free‐text option, some health visitors, particularly those with personal experience of multiple births, identified the rewards they gained from working with these families:

Interested in supporting children with special needs, not uncommon in multiple births. (2813)

With regard to the challenges and difficulties that health visitors encountered working with multiple birth families, it was clear that the additional time required to provide care for multiple birth families was the most prominent challenge (Figure 2). Extra work was generated in terms of double appointment times (23%), needing more home visits (18%) and persuading managers to allow this extra time (8%). Participants who were qualified for less than 5 years were more likely to feel challenged by a lack of knowledge about supporting the families (), limited awareness of third sector / local support services () and lack of experience pertaining to multiple births ().

FIGURE 2.

The challenges / difficulties identified by health visitors when working with multiple birth families

The health visitors were asked on which aspects of parenting that parents of multiples wanted information and guidance. The majority of the health visitors (60%) identified aspects of caring for multiple birth children covered information and guidance on infant nutrition, managing crying, developing a relationship with both children and sleep and bed‐sharing. Child development and the promotion of individuality were identified by 18% of the health visitors as the next most common areas of guidance required by parents. The health visitors wanted similar information and guidance to the parents with 50% wanting further information on the various aspects of child care and development and 25% wanting information on bereavement. There were no significant differences between the information and guidance asked for based on the health visitor's time in post.

The health visitors identified a number of resources that they felt would help facilitate the support they gave to multiple birth families. A directory of third sector support services (e.g., charities, voluntary organizations and local support groups) was the most frequent suggestion (23%). Other resources included national or local guidelines (18%) or a multiple birth care pathway (17%). Those who had been qualified for 5 years of more, were more likely to request continuing professional development on multiple births ().

Caring for multiple birth families can sometimes involve “hidden work” such as hands‐on childcare which does not fit the current remit of the health visitor role (Alamad et al., 2018). Nearly 100% of respondents, irrespective of time in post, provided examples of additional work they undertook while visiting these families. This included playing with or distracting other siblings (86%), feeding babies and dressing children (55% and 56%, respectively). Over half of respondents (56%) visited multiple birth families with a colleague or nursery nurse to share the workload.

The final free‐text question of the survey provided the health visitors with the opportunity to share any additional experiences of working with multiple birth families. Just under a third (86/290) responded. Three themes were identified from the analysis of these data.

“Personal / professional experiences” was the largest theme outlining experiences and the impact of working with multiple birth families. Some health visitors had previously run dedicated support groups which were no longer running due to cessation of funding. Others described the challenges they encountered and the personal rewards they experienced when trying to provide the best support possible to multiple birth families. Some described the frustration they felt when their colleagues or managers did not recognize the specific needs of these families. Whilst some health visitors related their practice to their personal experience of multiple birth, others identified their perceived lack of knowledge.

Sometimes feel I am under skilled as a practitioner to support multiples fully due to limited knowledge and time constraints. (5347)

The second theme “service provision” recognized the impact of the withdrawal of services for multiple birth families over recent years and proposed suggestions about the ways in which support for families could be improved.

A care pathway of optional extra visits would be very helpful. (0413)

I think they do need more support but staff shortages reduce the ability to offer this. (9152)

The third theme explored “family experiences”. The health visitors reiterated the impact of multiple birth on families and indicated that families had increased needs when compared to families with singletons. The increased prevalence of preterm birth, health and developmental concerns and bereavement amongst multiple birth children were recognised as impacting families’ experiences.

Having more than 1 of the same age is not like having more than one child of differing ages ‐ it's really hard work for these parents ‐ in all aspects of their lives. (0065)

4. DISCUSSION

This study used a cross‐sectional, descriptive survey to obtain an invaluable, first‐hand insight into the experiences of health visitors supporting multiple birth families across the United Kingdom. The wider challenges and pressures that they face and the influence of workload configuration on providing an effective service were able to be identified. The findings of this study replicate those of an earlier small‐scale qualitative study with health visitors in the United Kingdom (Alamad et al., 2018) and public health nurses in Finland (Heinonen, 2017).

It might be assumed that the survey would only attract health visitors who already favor and/or have personal experience of multiples. However, some respondents gave responses which indicated that they felt multiple birth families did not have particular or specific needs. In addition, almost half of respondents did not have personal experience of multiple birth.

A previous small‐scale study with health visitors indicated a lack of content relating to multiple births in health visitor education (Alamad et al., 2018). It was therefore considered important to see if this was an issue nationally. The study provides evidence of the lack of education and continuing professional development that health visitors in the United Kingdom receive about multiple births. This should be of concern to policy makers, those responsible for service provision and institutions providing health visitor education and continuing professional development given the specific impact that multiple births can have on family wellbeing (Bryan, 2003; Jena et al., 2011, El‐Toukhy et al., 2018; Scoats et al., 2018). The current lack of robust evidence, guidelines and standards for health visitors about providing care and support to multiple birth families compounds the problem regarding the lack of education. This deficit is most keenly felt by health visitors qualified for 5 years or less, who expressed feeling particularly challenged by their lack of knowledge and awareness of third sector support. Consequentially health visitors are most likely to base their practice on their previous professional experience and discussion with colleagues.

It is clear that many health visitors enjoy working with multiple birth families and are aware of the challenges that multiple birth families face. These health visitors do their best to support families within the confines of their role and the availability of ever diminishing resources. In some instances, health visitors indicated that they undertook “hidden” work by carrying out activities that they are not “allowed” to do, such as bathing or feeding multiple birth infants. The performance of hidden work echoes the findings of the earlier qualitative study (Alamad et al., 2018). Bereavements featured prominently as an area requiring health visitor support in the exploratory study (Alamad et al., 2018), this was also the case for the survey, with 25% of health visitors selecting this as an area they felt they needed more information about. However, only 6% of respondents reported bereavement as an area parents need guidance on.

The health visitors almost unanimously agreed that the most challenging time‐period for multiple birth families is the 0–12 month time‐period, which is endorsed by other evidence (Harvey et al., 2014). None of the health visitors selected the 49–60 month time‐period which is when most families will be preparing their children for transition to school. The evidence suggests that the period of transition to school may be regarded as a stressful time for families (Darbyshire et al., 2014; Huser et al., 2016) and may be even more stressful for multiple birth families as they are faced with decisions about classroom separation (Alexander, 2012; White et al., 2018). These effects are exacerbated where multiples are born prematurely (Blackburn & Harvey, 2018). This lack of recognition by the respondents that this period of transition might present additional stressors for families with multiple births, represents a potential area of unrecognized and unmet need for the health visiting service. The widespread lack of a designated care pathway for multiple birth families suggests that policy makers and those responsible for service provision fail to recognize the specific needs of multiple birth families from birth to starting in Reception class.

This is the first such study to generate evidence regarding health visitor experiences supporting multiple birth families in the United Kingdom. Although responses were received from all four nations of the United Kingdom, it is acknowledged that the study findings were predominantly from England. A potential limitation in the use of the online survey was sampling bias with younger practitioners who are more confident with online activities completing the survey, however, this cannot be confirmed as participant age was not requested. It is recognized that recipients may have chosen to ignore the request or failed to complete due to lack of time or interest in the subject. Overall, the study provided health visitors with the opportunity to clarify their challenges, needs and concerns both about working with multiple birth families and the wider challenges of their role

5. CONCLUSION

There is increasing global recognition of the importance of early childhood development (WHO, 2020) and the critical first 1001 days (Department of Health & Social Care, 2021). The global twinning rates are increasing (Monden et al., 2021) placing greater demand on health and social care services. Health visitors, like other public health nurses globally, have in‐depth knowledge of the health and social care needs of their communities and this enables them to advocate for families. (Institute of Health Visiting, 2019) In the United Kingdom, health visitors are uniquely positioned to support multiple birth families, in particular during the more challenging early years (Hamill, 2014; Harvey et al., 2014). However, the findings of this study suggest that many health visitors are aware that the care and support that they are able to provide multiple birth families falls short of meeting their needs. This is a call for greater recognition of the individualized needs of multiple birth families.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We wish to thank the Burdett Trust for Nursing for the funding in support of this study, Dr Cheryll Adams and the Communications Team from the Institute of Health Visiting and the health visitors for taking the time to complete the survey.

The article draws upon information from the original report which was produced for the Burdett Trust for Nursing. The report is available at: www.bcu.ac.uk/support‐mbf

Turville, N. , Alamad, L. , Denton, J. , Cook, R. , & Harvey, M. (2022). Supporting multiple birth families: Perceptions and experiences of health visitors. Public Health Nursing, 39, 229–237. 10.1111/phn.13008

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- Alamad, L. , Denton, J. , & Harvey, M. (2018). Health Visitors’ experiences supporting multiple birth families: An exploratory study. Journal of Health Visiting, 6(12), 610–620. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, M. T. (2012). Educating multiples in the classroom: Together or separate? Early Childhood Education Journal, 40, 133–136. 10.1007/s10643-011-0501-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blackburn, C. , & Harvey, M. (2018). ‘A different kind of normal’: Parents’ experiences of early care and education for young children born prematurely. Early Childhood Development and Care, 190(3), 296–309. 10.1080/03004430.2018.1471074 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan, E. (2003). The impact of multiple preterm births in the family. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 110(s20), 24–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darbyshire, N. , Finn, B. , Griggs, S. , & Ford, C. (2014). An unsure start for young children in English urban primary schools. The Urban Review, 46, 816–830. 10.1007/s11256-014-0304-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health . (2009). Healthy child programme. Pregnancy and the first five years of life. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/167998/Health_Child_Programme.pdf

- Department of Health . (2019). Northern Ireland health and social care (HSC) workforce census March 2019. Department of Health . [online] Health. https://www.health-ni.gov.uk/publications/northern-ireland-health-and-social-care-hsc-workforce-census-march-2019

- Department of Health and Social Care . (2021). The best start for life. A vision for the 1,001 critical days . https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/973112/The_best_start_for_life_a_vision_for_the_1_001_critical_days.pdf

- Dodd, J. M. , Dowswell, T. , & Crowther, C. A. (2015). Specialised antenatal clinics for women with a multiple pregnancy for improving maternal and fetal outcomes (Review). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2015(11), CD005300. 10.1002/14651858.CD005300.pub4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domato, E. (2005). Parenting multiple infants. Newborn and Infant Nursing Reviews, 5(4), 208–214. [Google Scholar]

- Donetto, S. , & Maben, J. (2014). ‘These places are like a godsend’: A qualitative analysis of parents’ experiences of health visiting outside the home and of children's centres services. Health Expectations, 18(6), 2559–2569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El‐Toukhy, T. , Bhattacharya, S. , & Akande, V. A. the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (2018). Multiple pregnancies following assisted conception. Scientific Impact Paper no. 22. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 125(5), e12–e18. 10.1111/1471-0528.14974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Expert Group on Multiple Births after IVF . (2006). One child at a Time: Reducing multiple births after IVF .

- Fell, D. B. , & Joseph, K. (2012). Temporal trends in the frequency of twins and higher‐order multiple births in Canada and the United States. BMC pregnancy and childbirth, 12, 103. 10.1186/1471-2393-12-103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamill, C. (2014). Specialist support for parents of twins. Journal of Health Visiting, 2(11), 586–588. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, M. E. , Athi, R. , & Denny, E. (2014). Exploratory study on meeting the health and social care needs of mothers with twins. Community Practitioner, 87(2), 28–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, M. & Land, L. (2017) Research methods for nurses and midwives: theory and practice. Los Angeles: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Heinonen, K. (2015). Methodological and hermeneutic reduction – A study of Finnish multiple‐birth families. Nurse Researcher, 22(6), 28–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinonen, K. (2016). Supporting multiple‐birth families at home. International Journal of Caring Sciences, 9(2), 422–431. [Google Scholar]

- Heinonen, K. (2017). Social‐and health‐care professionals’ meetings with multiple birth families – challenges and the need for more training and education. Journal of Health Science, 6, 310–328. [Google Scholar]

- Huser, C. , Dockett, S. , & Perry, B. (2016). Transition to school: Revisiting the bridge metaphor. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 24(3), 439–449, 10.1080/1350293X.2015.1102414 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Health Visiting , (2019). Health visiting in England: A vision for the future . https://ihv.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/7.11.19-Health-Visiting-in-England-Vision-FINAL-VERSION.pdf

- Jena, A. B. , Goldman, D. P. , & Joyce, G. (2011). Association between the birth of twins and parental divorce. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 117(4), 892–897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins, D. A. , & Coker, R. C. (2010). oping with triplets: Perspectives of parents during the first four years. Health Social Work, 35(3), 169–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard, I. , & Denton, J. (2006). Preparation for parenting multiple children. Early Human Development, 82, 371–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrifield, N . (2017). Warning drive to boost Scottish health visitor workforce falling behind target. Nursing Times, [online] https://www.nursingtimes.net/news/workforce/warning-over-drive-to-boost-scottish-health-visitor-workforce-20-06-2017 [Google Scholar]

- Monden, C. , Pison, G. , & Smits, J. (2021). Twin peaks: More twinning in humans than ever before. Human Reproduction, 36(6), 1666–1673. 10.1093/humrep/deab029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montacute, R. , & Bunn, S. (2016). Infant Mortality and Stillbirth in the UK. , Number 527 May 2016 London: The Parliamentary Office of Science and Technology. [Google Scholar]

- NICE . (2019). Twin and triplet pregnancy. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng137 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowell, L. , Norris, J. , White, D. , & Moules, N. (2017). Thematic analysis: Striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 16, 1–13. 10.1177/1609406917733847 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nursing & Midwifery Council . (2004). Standards of proficiency for specialist community public health nurses. https://www.nmc.org.uk/standards/standards-for-post-registration/standards-of-proficiency-for-specialist-community-public-health-nurses/

- Nurse, S. , & Kenner, C. (2011). Multiples in the newborn intensive care unit: Parents’ and nurses’ perspectives. Newborn and Infant Nursing Reviews, 11(4), 175–179. [Google Scholar]

- Office for National Statistics . (2020). Birth Characteristics in England and Wales : (2019). https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/livebirths/datasets/birthcharacteristicsinenglandandwales/

- Ooki, S. , & Hiko, K. (2012). Strategy and practice of support for families with multiple births children: Combination of Evidence‐based Public Health (EBPH) and Community‐Based Participatory Research (CBPR) Approach Public Health. InTech, 405–430. 10.5772/36112 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ostlund, A. , Nordstrom, M. , Dykes, F. , & Flackling, R. (2010). Breastfeeding in preterm and term twins, maternal factors associated with early cessation: A population based study. Journal of Human Lactation, 26(3), 354–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redshaw, M. , Henderson, J. , & Kurinczuk, J. J. (2011). Maternity care for women having a multiple birth. Oxford: National Perinatal Epidemiology Unit. [Google Scholar]

- Scoats, R. , Denton, J. , & Harvey, M. (2018). One too many? Families with multiple births. Community Practitioner, 91(10), 20–31. [Google Scholar]

- Sherwood, B. (2019). Staff directly employed by the NHS in Wales, at 30 September 2018 . [online] Welsh Government. https://gov.wales/sites/default/files/statistics-and-research/2019-03/staff-directly-employed-by-the-nhs-30-september-2018-167.pdf

- Shinwell, E. S. , Haklai, T. , & Eventov‐Friedman, S. (2009). Outcomes of multiplets. Neonatology, 95(1), 6–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman, D. (2014). Interpreting qualitative data (5th ed.). SAGE Publications Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- White, E. K. , Garon‐Carrier, G. , Tosto, M. G. , Malykh, S. B. , Li, X. , Kiddle, B. , Riglin, L. , Byrne, B. , Dionne, G. , Brendgen, M. , Vitaro, F. , Tremblay, R. E. , Boivin, M. , & Kovas, Y. (2018). Twin classroom dilemma: To study together or separately? Developmental Psychology, 54(7), 1244–1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitford, H. M. , Wallis, S. K. , Dowswell, T. , West, H. M. , & Renfrew, M. J. (2017). Breastfeeding education and support for women with twins or higher order multiples (Review). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2017(2), CD012003. 10.1002/14651858.CD012003.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenze, S. J. , Battle, C. L. , & Tezanos, K. M. (2015). Raising multiples: Mental health of mothers and fathers in early parenthood. Archives of Women's Mental Health, 18(2), 163–176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO , (2020). Improving early childhood development: WHO guideline . https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/97892400020986 [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.