Abstract

Bacterial small RNAs regulate the expression of multiple genes through imperfect base‐pairing with target mRNAs mediated by RNA chaperone proteins such as Hfq. GcvB is the master sRNA regulator of amino acid metabolism and transport in a wide range of Gram‐negative bacteria. Recently, independent RNA‐seq approaches identified a plethora of transcripts interacting with GcvB in Escherichia coli. In this study, the compilation of RIL‐seq, CLASH, and MAPS data sets allowed us to identify GcvB targets with high accuracy. We validated 21 new GcvB targets repressed at the posttranscriptional level, raising the number of direct targets to >50 genes in E. coli. Among its multiple seed sequences, GcvB utilizes either R1 or R3 to regulate most of these targets. Furthermore, we demonstrated that both R1 and R3 seed sequences are required to fully repress the expression of gdhA, cstA, and sucC genes. In contrast, the ilvLXGMEDA polycistronic mRNA is targeted by GcvB through at least four individual binding sites in the mRNA. Finally, we revealed that GcvB is involved in the susceptibility of peptidase‐deficient E. coli strain (Δpeps) to Ala‐Gln dipeptide by regulating both Dpp dipeptide importer and YdeE dipeptide exporter via R1 and R3 seed sequences, respectively.

GcvB is the master small RNA regulator of amino acid metabolism and transport. Through the compilation of RNA‐seq data sets, we validated 21 new GcvB targets, and the GcvB regulon now comprises 54 genes in Escherichia coli. GcvB represses most targets via either R1 or R3 seed sequence, but both R1 and R3 are required to fully repress gdhA. GcvB also regulates ilvLXGMEDA by binding to at least four individual sites in the mRNA.

1. INTRODUCTION

Bacteria thrive in everchanging environments by regulating their gene expression at multiple levels, including transcription, translation, RNA degradation, and protein degradation. Transcriptional regulation has been regarded as the primary level of regulation, but posttranscriptional regulation also plays an important role in fine‐tuning gene expression. Small RNAs (sRNAs) have emerged as major posttranscriptional regulators that affect translation initiation and/or mRNA stability both negatively and positively (Kavita et al., 2018; Storz et al., 2011; Wagner & Romby, 2015). In Gram‐negative bacteria, this class of sRNAs generally acts on multiple mRNAs in trans through imperfect base‐pairing interactions with the help of RNA chaperones such as Hfq and ProQ (Olejniczak & Storz, 2017; Updegrove et al., 2016; Vogel & Luisi, 2011; Woodson et al., 2018). Our knowledge of the regulatory mechanisms deployed by sRNAs relies on studies of the model organisms Escherichia coli and Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium (hereafter referred to as Salmonella). E. coli and Salmonella share dozens of conserved sRNAs displaying both conserved and specific regulatory mechanisms and targets (Hör et al., 2020).

Two decades ago, the first report identifying the sRNA GcvB in E. coli was published in this journal (Urbanowski et al., 2000). GcvB is a noncoding sRNA of ~200 nucleotides (nt) transcribed divergently from the gcvA gene, which encodes the transcriptional activator of the gcvTHP operon in the glycine cleavage (GCV) pathway (Stauffer, 2004). Transcription factors, GcvA and GcvR, regulate the transcription of gcvTHP and GcvB (Ghrist et al., 2001; Heil et al., 2002; Stauffer & Stauffer, 2005). GcvB is induced when the intracellular levels of Gly are high (Sharma et al., 2007; Urbanowski et al., 2000).

The steady‐state level of endogenous GcvB is determined not only by its de novo synthesis but also by its degradation rate. GcvB is mainly degraded by RNase E which is triggered by base‐pairing with SroC sRNA at two distal sites in the stem‐loops (SL) 1 and 4 (Miyakoshi et al., 2015). SroC is a very stable sRNA processed from the 3′ untranslated region (UTR) of gltI mRNA (Vogel et al., 2003), which is part of the polycistronic gltIJKL operon encoding the Glu/Asp ABC transporter. Comprehensive identification of RNA–RNA interactome by RIL‐seq has revealed that during aerobic growth in a peptide‐rich LB medium, 0.1% of GcvB sRNAs are associated with SroC during the exponential phase while the proportion of the GcvB‐SroC hybrid during the stationary phase dramatically increases up to ~70% of the total of GcvB (Melamed et al., 2016, 2020). Consequently, the level of GcvB was high during the exponential phase (~140 copies/cell) but decreased as the cells accumulated SroC during the stationary phase (Lalaouna et al., 2019; Miyakoshi et al., 2015).

GcvB is conserved in a wide spectrum of Gram‐negative bacteria not only in Enterobacteriaceae but also in some genera of other families such as Actinobacillus, Pasteurella, Photorhabdus, and Vibrio (Gulliver et al., 2018; McArthur et al., 2006; Sharma et al., 2007; Silveira et al., 2010). Within E. coli and Salmonella, GcvB differs by 10 nt but shares almost the same secondary structure and function. GcvB utilizes three conserved seed sequences, namely R1, R2, and R3, to regulate multiple target genes. The G/U‐rich R1 region is capable of base‐pairing interactions with the majority of GcvB target mRNAs (Pulvermacher et al., 2008, 2009a, 2009b; Sharma et al., 2007, 2011; Yang et al., 2014). Although the R2 sequence is highly conserved, it may only be utilized to repress cycA mRNA in E. coli and Salmonella (Pulvermacher et al., 2009c; Sharma et al., 2011). The R3 seed sequence located in SL4 regulates several mRNAs including phoP and lrp, which encode global transcriptional regulators (Coornaert et al., 2013; Lalaouna et al., 2019; Lee & Gottesman, 2016), while it also serves as the target site for SroC (Miyakoshi et al., 2015).

Previous studies revealed that GcvB directly regulates more than 30 genes mainly encoding amino acid transporters and metabolic enzymes in E. coli and Salmonella (Table 1). Upon recent developments in experimental RNA‐seq methodologies (Desgranges et al., 2020; Hör et al., 2018; Saliba et al., 2017), the discovery rate of sRNA targets has been refined by integrating multiple prediction tools and available global RNA–RNA interactome data sets (Arrieta‐Ortiz et al., 2020; Georg et al., 2020; King et al., 2019). Taking the advantage of combining RNA‐seq data sets, this study aims to explore the unrealized potential of GcvB regulon. To this end, we compared RNA–RNA interactome data sets in E. coli MG1655 and its derivatives in similar growth conditions: RIL‐seq (RNA interaction by ligation and sequencing) (Melamed et al., 2016, 2020), CLASH (UV cross‐linking, ligation, and sequencing of hybrids) (Iosub et al., 2020), and MAPS (MS2‐affinity purification coupled with RNA sequencing) (Lalaouna et al., 2019). We validated 21 new direct targets that were posttranscriptionally repressed by GcvB. The majority of GcvB targets are regulated via either R1 or R3 seed sequence, while GcvB utilizes both R1 and R3 to fully repress the expression of gdhA, cstA, and sucC mRNAs and to target four individual binding sites in the ilvLXGMEDA polycistronic mRNA. Finally, functional analysis of the GcvB regulon revealed that gcvB deletion restored the growth of a peptidase‐deficient E. coli strain (Δpeps) in the presence of dipeptides such as Ala‐Gln. GcvB regulates both the Dpp dipeptide importer and the YdeE dipeptide exporter by utilizing R1 and R3 seed sequences, respectively, to maintain the homeostasis of intracellular dipeptides.

TABLE 1.

GcvB regulon

| Classification | Gene | Gene product | LB_exp | LB_stat | LB_exp | M63Glu | CLASH | MAPS | Seed | Escherichia coli | Salmonella |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABC transporter | argT | Arg/Lys/Orn‐binding periplasmic protein | 5,814 | 2,754 | 40,963 | 129 | 205 | 64.2 | R1 | Conserved | Verified |

| dppA | Dipeptide‐binding periplasmic protein | 2,627 | 8,981 | 28,361 | 398 | 50 | 119.6 | R1 | Verified | Verified | |

| gltI | Asp/Glu‐binding periplasmic protein | 443 | 327 | 1,107 | 34 | 17 | 236.3 | R1 | Conserved | Verified | |

| hisQ | Arg/Lys/Orn/His ABC transporter membrane subunit | 66 | 0 | 1,979 | 0 | 0 | 42.8 | R1 | Verified | Conserved | |

| livJ | Leu/Val/Ile/Phe‐binding periplasmic protein | 80 | 49 | 191 | 547 | 0 | 22.4 | R1 | Conserved | Verified | |

| livK | Leu/Phe‐binding periplasmic protein | 16 | 0 | 179 | 85 | 12 | 10.2 | R1 | Conserved | Verified | |

| metQ (yaeC) | Met‐binding periplasmic protein | 0 | 0 | 101 | 0 | 0 | 76.4 | R1 | Conserved | Verified | |

| nlpA | Met‐binding periplasmic protein | 81 | 0 | 144 | 0 | 0 | 50.5 | R3 | Verified | Absent | |

| oppA | Oligopeptide‐binding periplasmic protein | 1,873 | 1,053 | 4,196 | 153 | 42 | 52.3 | R1 | Verified | Verified | |

| tcyJ (fliY) | Cystine‐binding periplasmic protein | 5,001 | 71 | 9,134 | 0 | 4 | 95.2 | R1 | Verified | Conserved | |

| tppB (dtpB) | Tripeptide‐binding periplasmic protein | 167 | 0 | 306 | 0 | 0 | 48.4 | R1 | Conserved | Verified | |

| STM4351 | Arg‐binding periplasmic protein | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | R1 | Absent | Verified | |

| Permease | aroP | Phe/Tyr/Trp permease | 171 | 18 | 253 | 22 | 0 | 22.4 | R1 | Verified | Conserved |

| brnQ | Leu/Val/Ile permease | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8.2 | R1 | Conserved | Verified | |

| cstA | Peptide/Pyruvate permease | 86 | 1,251 | 4,950 | 0 | 7 | 12.6 | R1/R3 | Verified | Conserved | |

| cycA | Gly/Ala/d‐Ala/β‐Ala/d‐Ser/cyclo‐Ser permease | 252 | 803 | 2,597 | 68 | 44 | 279.3 | R1/R2/R3 | Verified | Verified | |

| gltP | Asp/Glu permease | 157 | 0 | 270 | 0 | 1 | 19.4 | R1 | Verified | Conserved | |

| kgtP | 2‐oxoglutarate permease | 186 | 0 | 3,413 | 0 | 1 | 34.5 | R1 | Verified | Conserved | |

| sstT | Ser/Thr permease | 17,893 | 5,410 | 50,726 | 5,963 | 1 | 97.2 | R1 | Verified | Verified | |

| yifK | unknown permease | 1,493 | 207 | 4,738 | 23 | 23 | 35.2 | R1 | Verified | Conserved | |

| Antiporter | ydeE | Dipeptide antiporter | 35 | 22 | 164 | 0 | 0 | 9.2 | R3 | Verified | Not conserved |

| Amino acid metabolism | aroC | Chorismate synthase | 1,120 | 185 | 2,859 | 24 | 34 | 20.2 | R1 | Verified | Conserved |

| asd | Asp‐semialdehyde dehydrogenase | 110 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 15.8 | R1 | Verified | Conserved | |

| asnA | Asn synthetase A | 0 | 29 | 88 | 14 | 0 | 82.7 | R3 | Verified | Conserved | |

| asnB | Asn synthetase B | 0 | 0 | 133 | 0 | 58 | 37.8 | R1 | Verified | Conserved | |

| gdhA | Glu dehydrogenase | 618 | 230 | 3,035 | 210 | 5 | 147.0 | R1/R3 | Verified | Conserved | |

| ilvB | Acetolactate synthase I, large subunit | 599 | 177 | 3,620 | 10 | 0 | 242.6 | R1 | Verified | Conserved | |

| ilvC | Ketol acid reductoisomerase | 0 | 0 | 122 | 0 | 6 | 2.1 | R1 | Conserved | Verified | |

| ilvD | Dihydroxy acid dehydratase | 0 | 0 | 133 | 19 | 0 | 17.0 | R3 | Verified | Conserved | |

| ilvE | Leu/Val/Ile/Phe aminotransferase | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 181.4 | R1 | Conserved | Verified | |

| ilvM | Acetolactate synthase II, small subunit | 333 | 26 | 438 | 46 | 0 | 29.6 | R1 | Verified | Conserved | |

| ilvL | Ile/Val biosynthesis leader peptide | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1.0 | R1 | Verified | Conserved | |

| ivbL | Ile/Val biosynthesis leader peptide | 0 | 199 | 999 | 20 | 0 | 399.6 | R1 | Verified | Conserved | |

| map | Met aminopeptidase | 21 | 0 | 139 | 0 | 0 | 12.6 | R3 | Verified | Conserved | |

| panD | Asp 1‐decarboxylase proenzyme | 37 | 17 | 195 | 0 | 7 | 207.9 | R3 | Verified | Conserved | |

| serA | Phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase | 362 | 109 | 887 | 41 | 30 | 90.9 | R1 | Conserved | Verified | |

| thrL | Thr biosynthesis leader peptide | 482 | 1,185 | 1,944 | 30 | 8 | 124.7 | R1 | Conserved | Verified | |

| trpE | Anthranilate synthase | 0 | 107 | 37 | 0 | 0 | 4.6 | R1 | Verified | Conserved | |

| Carbon metabolism | acs | Acetyl‐CoA synthetase | 0 | 21 | 26 | 0 | 12 | 34.7 | R1 | Verified | Conserved |

| gatY | Tagatose‐1,6‐bisphosphate aldolase | 1,558 | 443 | 1,568 | 0 | 1 | 21.1 | Unknown | Verified | Conserved | |

| icd | Isocitrate dehydrogenase | 137 | 43 | 4,580 | 0 | 1 | 16.6 | R1 | Verified | Conserved | |

| purU | Formyltetrahydroforate deformylase | 265 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 36.3 | R1 | Verified | Conserved | |

| sucC | Succinyl‐CoA synthetase | 220 | 52 | 843 | 0 | 0 | 37.2 | R1/R3 | Verified | Conserved | |

| ybdH (hcxA) | Hydroxycarboxylate dehydrogenase | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 32.6 | R1 | Conserved | Verified | |

| ysgA (dlhH) | Dienelactone hydrolase | 226 | 587 | 2,227 | 0 | 15 | 105.0 | R1 | Verified | Conserved | |

| Membrane integrity | cfa | Cyclopropane fatty acid synthase | 455 | 0 | 2,203 | 0 | 106 | 10.5 | R3 | Verified | Conserved |

| inaA | Putative LPS kinase | 0 | 0 | 117 | 0 | 0 | 20.0 | R3 | Verified | Absent | |

| mltC a | Membrane‐bound lytic murein transglycosylase | 877 | 33 | 1,323 | 0 | 11 | 41.3 | R1 | Verified | Conserved | |

| RNA metabolism | ndk | Nucleoside diphosphate kinase | 0 | 0 | 43 | 0 | 0 | 31.6 | R1 | Conserved | Verified |

| rbsK | Ribokinase | 0 | 0 | 489 | 0 | 7 | 29.0 | R1 | Verified | Conserved | |

| rbn (elaC) | RNase BN | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3.1 | Unknown | Verified | Conserved | |

| Transcriptional regulator | argP (iciA) | Arg transcriptional regulator | 79 | 0 | 190 | 0 | 0 | 20.4 | R1 | Conserved | Verified |

| lrp | Leu responsive protein | 0 | 0 | 1,063 | 0 | 11 | 547.4 | R3 | Verified | Verified | |

| phoP | Mg2+ transcriptional regulator | 0 | 0 | 92 | 0 | 0 | 54.7 | R3 | Verified | Not conserved | |

| csgD | Curli transcriptional regulator | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7.1 | R1 | Verified | Conserved | |

| No regulation | raiA | Ribosome associate inhibitor A | 4,094 | 142 | 7,607 | 0 | 1 | 96.9 | Unknown | Verified | Conserved |

| Sponge | sroC | sRNA derived from gltI 3′UTR | 0 | 67,138 | 207 | 722 | 4 | 203.9 | SL1/R3 | Conserved | Verified |

| Other GcvB reads | 3,469 | 4,017 | 20,852 | 87 | 596 | ||||||

| Total GcvB reads | 51,238 | 95,686 | 211,831 | 8,645 | 1,323 | ||||||

Information on the validated targets of the GcvB regulon was sorted from RIL‐seq performed in 2016 (in orange) and 2020 (in red), CLASH (in green) and MAPS (in blue) data sets. Quantitative information for each target is presented as the number of sequenced chimeras in the RIL‐seq and in the CLASH and as the ratio of chimeras obtained in the MS2‐GcvB/untagged GcvB control in the MAPS data set. New target genes validated in this study are shown in bold font. The seed region of GcvB and the conservation of target sites in E. coli and Salmonella are indicated in the right columns.

Abbreviation: NA, not applicable.

The yggX chimera was read as mltC because it is assigned in the intergenic region of yggX‐mltC in the same operon.

2. RESULTS

2.1. Identification of new GcvB targets from RNA–RNA interactome data sets

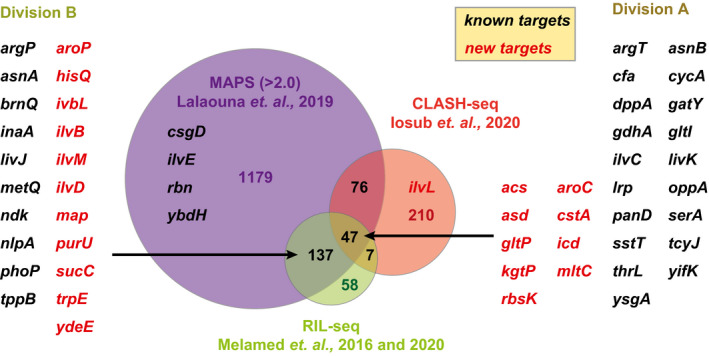

Because GcvB is considered as one of the most global sRNA regulators in terms of both its copy number and the number of its direct targets in the cell, we revisited the interactants in the available RNA–RNA interactome data sets obtained in E. coli. Through the compilation of two individual RIL‐seq data sets, a total of 249 RNAs were shown to interact with GcvB through Hfq in E. coli cells grown in LB medium to exponential and stationary phases or M63 glucose minimal medium (Melamed et al., 2016, 2020). The CLASH methodology showed a total of 262 RNAs interacting with GcvB through Hfq in LB‐grown E. coli cells at several growth phases (Iosub et al., 2020). Comparing these two independent data sets revealed 54 overlapping RNA interactants (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Venn diagram of GcvB‐interacting RNAs in the RIL‐seq, CLASH, and MAPS data sets. The cutoff ratio of interactants in the MAPS data set was set at 2.0. Validated GcvB targets found within the three methodologies are categorized into Division A. Validated GcvB targets detected by RIL‐seq and MAPS but not by CLASH are categorized into Division B. Previously known targets are shown in black, and the new targets are highlighted in red

The MAPS approach identified transcripts that specifically interacted with GcvB during growth in LB medium and facilitated the verification of genuine GcvB targets (Lalaouna et al., 2019). The MAPS data are quantitatively represented by the ratio of transcripts pulled down with the MS2‐tagged GcvB relative to those pulled down with the unlabeled GcvB. The previous MAPS study has set a strict cutoff (>20) (Lalaouna et al., 2019), but the ratio is highly dependent on the expression levels of the target mRNAs. For example, among the previously validated GcvB targets, ilvC exhibited the lowest ratio (2.1) even though GcvB forms a strong base‐pairing to repress the translation of ilvC (Sharma et al., 2011). Hence, we expected many false‐negative targets in the MAPS data set and lowered the threshold to 2.0 in this study. This increased the number of GcvB‐interacting transcripts to 1,439 (Figure 1), which may conversely include many false positives but can be further narrowed down in combination with RIL‐seq and CLASH data. Among the 1,439 genes, 184 and 123 genes were also detected by RIL‐seq and CLASH, respectively. Finally, the overlap of all the independent interactome data sets revealed 47 genes as the best ranking targets for GcvB (Division A, Figure 1).

In E. coli and Salmonella, 19 out of the 47 interactants are previously verified GcvB targets (argT, asnB, cfa, cycA, dppA, gatY, gdhA, gltI, ilvC, livK, lrp, oppA, panD, serA, sstT, tcyJ, thrL, yifK, and ysgA) (Bianco et al., 2019; Faigenbaum‐Romm et al., 2020; Lalaouna et al., 2019; Lee & Gottesman, 2016; Modi et al., 2011; Pulvermacher et al., 2008, 2009a, 2009b, 2009c; Sharma et al., 2007, 2011; Yang et al., 2014) (Table S1). Furthermore, among the 137 genes that were present in the RIL‐seq data sets but absent in the CLASH data set (Division B), we found 10 previously verified GcvB targets (argP, asnA, brnQ, inaA, livJ, metQ, ndk, nlpA, phoP, and tppB) (Figure 1). In contrast, we could not find any known GcvB targets present in the CLASH data set but absent in the RIL‐seq data sets. This is attributable to the higher stringency of the purification steps of the CLASH protocol (Iosub et al., 2020). Moreover, RIL‐seq and CLASH failed to detect four known targets, namely csgD (Andreassen et al., 2018; Jørgensen et al., 2012), ilvE (Sharma et al., 2011), rbn (Chen et al., 2019), and ybdH (hcxA) (Sharma et al., 2011).

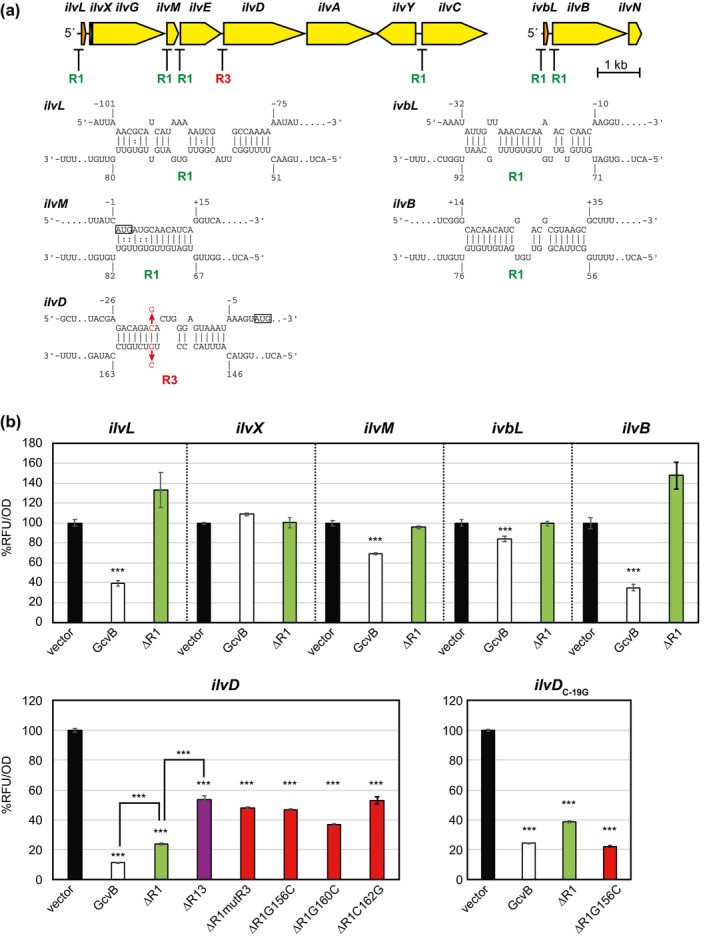

2.2. Verification of new GcvB targets by translational reporter assay

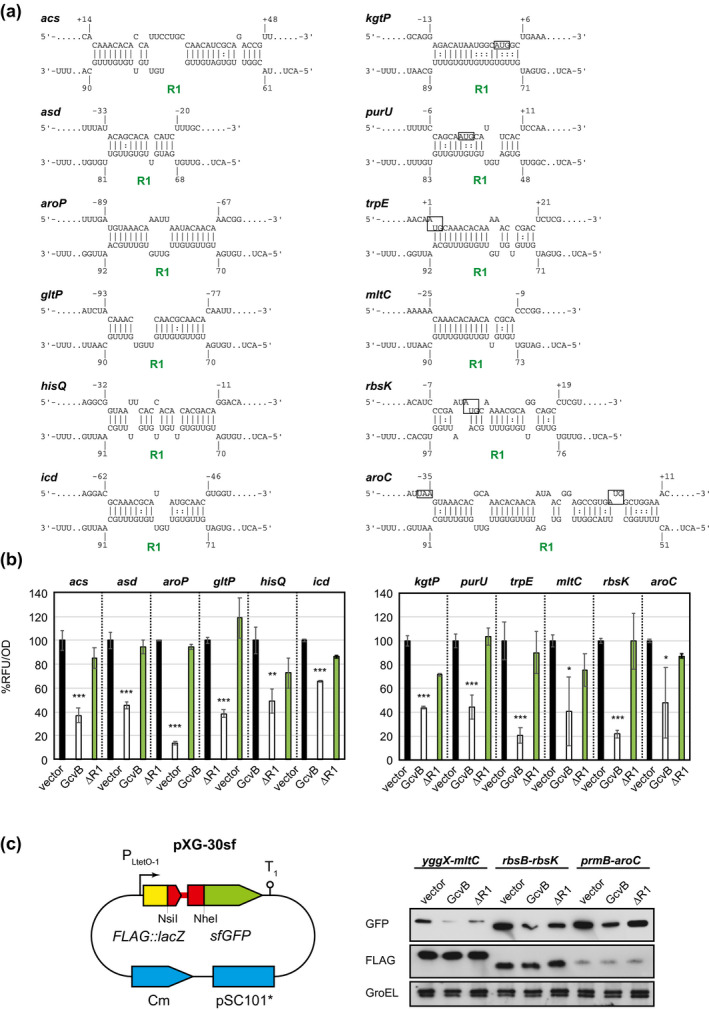

The identified overlapping targets in Division A represent the best candidates for new targets directly regulated by GcvB. Among the 28 out of 47 overlapping genes, we selected new candidates displaying abundant chimeric reads in RIL‐seq data (Table S1), namely acs, asd, cstA, icd, kgtP, gltP, hisJ‐hisQ, yggX‐mltC, prmB‐aroC, and rbsB‐rbsK. Moreover, in Division B, we also selected aroP, map, purU, sucB‐sucC, trpE, and ydeE because of their functional relevance and relationships with other targets. To verify whether GcvB regulates these candidates at the posttranscriptional level, we constructed translational fusions with the superfolder GFP (sfGFP) derived from pXG‐10sf and pXG‐30sf plasmids, which are suitable for analyzing the individual transcription units and the intraoperonic transcription units, respectively (Corcoran et al., 2012). The transcription start sites in the former constructs were retrieved from the EcoCyc database (Keseler et al., 2017, 2021). Our translational fusions include putative GcvB target sites predicted using the IntaRNA program (Mann et al., 2017). These candidate genes carry partially complementary sequences to the conserved R1 region (Figure 2a) with the exceptions of cstA, map, sucC, and ydeE, for which different interaction sites for GcvB can be identified (see below).

FIGURE 2.

New targets posttranscriptionally repressed by GcvB. (a) Base‐pairing interaction predicted by the IntaRNA program. Numbers above and below the nucleotide sequences indicate the nt location relative to the start codon of the mRNA and the transcription start site of GcvB, respectively. Start codons of mRNAs are shown in a box where displayed. (b) GFP reporter assays in Escherichia coli ΔgcvBΔsroC strain harboring pTP11 (vector), pPL‐gcvB (GcvB) or pPL‐gcvBΔR1 (GcvBΔR1). Fluorescence was measured on overnight grown cells. Mean fluorescence of biological replicates (n > 3) with SD are presented in percentage relative to the vector control. Statistical significance was calculated using one‐way ANOVA comparing GcvB or GcvBΔR1 with the vector control and denoted as follows: ***p < .001, **p < .005, *p < .05. (c) Schematic of the intraoperonic fusion construct (left). By inserting the NsiI‐NheI fragment into pXG30‐sf, the upstream and downstream ORFs (red) are fused in frame with FLAG‐lacZ (yellow) and sfGFP (green), respectively. Western blot analysis of the indicated target genes upon co‐expression of GcvB or GcvBΔR1 (right). The samples were collected at an OD600 of 1.0

To assess the direct effect of GcvB on the 12 candidate genes, we took advantage of the ΔgcvBΔsroC background for our reporter analysis throughout this study to exclude the sponging effect of SroC. Quantification of sfGFP fluorescence indicated that all translational fusions were significantly repressed by ectopically expressed GcvB (Figure 2b). The repression was fully or partially abrogated by deletion of the R1 region (GcvBΔR1). This result indicates that GcvB negatively regulates these candidate genes with various efficiencies through the R1 seed sequence at the posttranscriptional level. Notably, the expression of mltC was very low as previously observed in Salmonella (Sharma et al., 2011). For the three intraoperonic fusions with relatively low expression levels, the expression of both upstream and downstream fusions was analyzed by western blotting using anti‐FLAG and anti‐GFP antibodies, respectively. We confirmed that mltC, aroC, and rbsK were repressed by GcvB via the R1 region without affecting the expression of respective upstream genes (Figure 2c).

2.3. GdhA is posttranscriptionally regulated by both R1 and R3 seeds

Previous RIL‐seq analysis identified several genes that interact with GcvB devoid of R1, namely gdhA, cycA, gatY, cfa, yidF, panD, map, and ydeE (Melamed et al., 2016). Among them, the cfa and panD mRNAs were shown to be repressed through the R3 region (Bianco et al., 2019; Lalaouna et al., 2019), while the repression of gatY by GcvB has not been clarified in detail (Faigenbaum‐Romm et al., 2020). The previously validated genes targeted by the R3 region, inaA, nlpA, panD, and phoP (Coornaert et al., 2013; Lalaouna et al., 2019), showed relatively low chimeric reads with GcvB in the interactome data sets (Table 1). We reasoned that R1‐independent targets were underestimated in the presence of SroC and therefore looked for more R1‐independent targets by using the ΔgcvBΔsroC background. Previous studies have identified gdhA as a target of GcvB both in Salmonella and E. coli, but neither the R1 nor the R2 seed region is sufficient to regulate gdhA (Melamed et al., 2016; Sharma et al., 2011). This is reminiscent of cycA, which is redundantly regulated by the R1, R2, and R3 regions of GcvB (Lalaouna et al., 2019; Pulvermacher et al., 2009c; Sharma et al., 2011), suggesting that additional regions are involved in the posttranscriptional regulation of gdhA by GcvB.

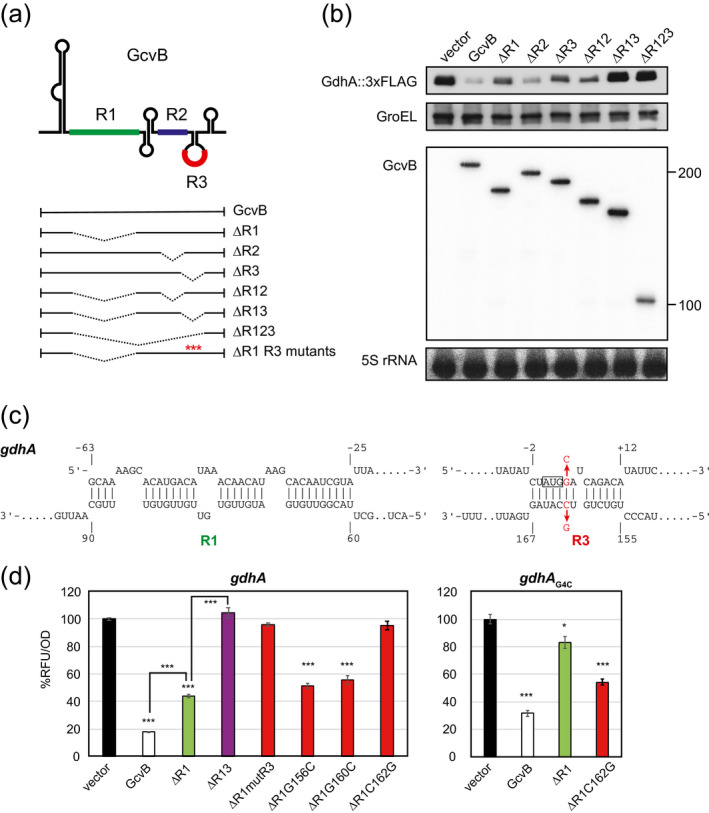

We analyzed the endogenous GdhA protein levels in E. coli during aerobic growth in LB medium. The expression of GdhA with a C‐terminal 3xFLAG was significantly elevated to the same extent in both the ΔgcvB and the ΔgcvBΔsroC deletion mutants (data not shown). We then ectopically expressed a series of GcvB deletion mutants (Figure 3a) and observed that the GdhA::3xFLAG levels were strikingly reduced by overexpression of GcvB. As expected, the repression was weakened by the deletion of the R1 region, whereas the deletion of the R2 region alone had no effect (Figure 3b), in line with the previous result using the gdhA translational fusion in Salmonella (Sharma et al., 2011). GcvB devoid of the R3 seed region (GcvBΔR3) displayed a significantly reduced ability to repress GdhA expression to almost the same level as GcvBΔR1 and further deletion of both R1 and R3 completely abolished the repression of GdhA (Figure 3b). Altogether, we conclude that GcvB relies solely on both R1 and R3 seed sequences to repress gdhA but does not require the R2 region. Remarkably, we noticed that the expression of GcvBΔR3 strikingly hindered the growth of E. coli ΔgcvBΔsroC strain (data not shown). This phenotypic defect was relieved by further deletion of the R1 region, implying that the R3 region somehow affects the regulation through R1 in E. coli. Hereafter we consider the comparison between GcvBΔR1 and GcvBΔR1ΔR3 constructs to evaluate the R3‐mediated regulation of target mRNAs.

FIGURE 3.

GcvB regulates gdhA mRNA through both R1 and R3 seed regions. (a) Schematic of GcvB and its deletion mutants. The transcribed regions are shown in plain line, and deleted regions are represented by dashed lines. Mutations in the R3 region (G156C, G160C, C162G, and mutR3) are indicated by red asterisks. (b) Western and northern blot analyses of chromosomally expressed GdhA::3xFLAG in Escherichia coli ΔgcvBΔsroC strain harboring pTP11 (vector), the GcvB‐expressing plasmid (GcvB), or its derivatives. The samples were collected at an OD600 of 1.0. (c) Base‐pairing interactions between GcvB and gdhA mRNA predicted by the IntaRNA program. (d) GFP reporter assays of gdhA::sfGFP in E. coli ΔgcvBΔsroC strain harboring pTP11 (vector), pPL‐gcvB (GcvB), or its derivatives. Mean fluorescence of biological replicates (n > 3) with SD are presented in percentage relative to the vector control. Statistical significance was calculated using one‐way ANOVA comparing GcvB or GcvBΔR1 with the vector control and denoted as follows: ***p < .001, *p < .05

Next, we investigated the base‐pairing interactions between GcvB and gdhA mRNA. Prediction by the IntaRNA program showed that the R1 and R3 regions hybridize with the 5′UTR and the translation initiation region of gdhA mRNA, respectively (Figure 3c). This suggests that our gdhA translational fusion construct equivalent to that previously used in Salmonella (Sharma et al., 2011) is sufficient to recapitulate the regulation by GcvB. In line with our western blot analysis, the GFP fluorescence of GdhA fusion protein was significantly reduced by the ectopic expression of GcvB, and the repression was partially hampered by the deletion of R1 alone and entirely lost when both R1 and R3 regions were deleted (Figure 3d). To test whether the R3 region interacts with gdhA translation initiation region by base‐pairing mechanism, we introduced point mutations in the R3 region of the GcvBΔR1 construct (Figure 3a). The repression was completely abrogated by the replacement of the 154th to 158th nt of GcvB (mutR3) (Coornaert et al., 2013) and also by the single C162G mutation (Figure 3d). Unexpectedly, the repression of GdhA::GFP fusion was not altered by G156C or G160C mutation, although the 156th and 160th guanines are likely engaged in the base‐pairing interaction. Next, we introduced a complementary mutation in the gdhA translation initiation region at the fourth nucleotide from the translational start site to compensate for the C162G mutation of GcvB. The G4C mutant of gdhA::GFP fusion was mildly affected by GcvBΔR1 but was significantly downregulated by GcvBΔR1C162G. We conclude that GcvB posttranscriptionally represses the expression of gdhA via both the R1 and R3 seed regions. Given that the two interacting regions are twisted in the two RNA molecules (Figure 3c), gdhA mRNA and GcvB are likely engaged in a complex tertiary structure if they bind with a 1:1 stoichiometry. We observed that each seed sequence contributed equally to the repression of gdhA (Figure 3b), but an in vitro study will be required to reveal how base‐pairing at the two sites inhibits the translation initiation of gdhA.

2.4. New targets regulated by both GcvB R1 and R3 regions

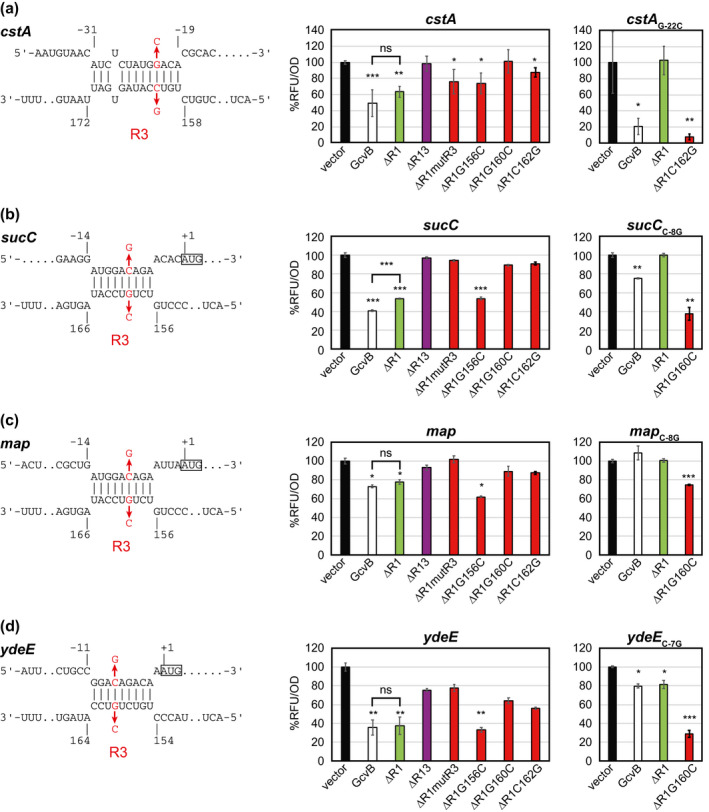

The in silico prediction suggested that additional new targets of GcvB were regulated through more than one seed sequence. As categorized into Division A (Figure 1), the cstA gene encoding an APC superfamily transporter for pyruvate and peptides was regarded as a plausible GcvB target. Our reporter analysis showed that GcvB repressed the expression of cstA translational fusion but the deletion of the R1 region alone did not significantly affect the repression of cstA (Figure 4a). The deletion of both R1 and R3 regions fully abrogated the repression by GcvB, clarifying that R3 is involved in the regulation of cstA. The G160C or C162G mutation in GcvBΔR1 significantly reduced the repression, whereas either G156C or mutR3 mutation did not affect the regulation, in agreement with the in silico prediction suggesting that the R3 region from 159th to 171st nt is engaged in the base‐pairing (Figure 4a). To confirm the base‐pairing interaction, we introduced a compensatory mutation, G‐22C, in the cstA translational fusion. In contrast to the wild type, the mutant translational fusion was significantly repressed by GcvBΔR1C162G but not at all by GcvBΔR1 (Figure 4a), indicating that R1 is also involved in the repression of cstA.

FIGURE 4.

Additional targets repressed by GcvB through both R1 and R3 or exclusively by R3. Base‐pairing interactions of (a) cstA, (b) sucC, (c) map, and (d) ydeE were predicted by IntaRNA program. GFP reporter assays of the translational fusions in overnight‐grown Escherichia coli ΔgcvBΔsroC strain harboring pTP11 (vector), pPL‐gcvB (GcvB), or its derivatives. Mean fluorescence of biological replicates (n > 3) with SD are presented in percentage relative to the vector control. Statistical significance was calculated using one‐way ANOVA comparing GcvB and its derivatives with the vector control and denoted as follows: ***p < .001, **p < .005, *p < .05

The sucC gene encoding the succinyl‐CoA synthetase β subunit was categorized into Division B (Figure 1). We constructed an intraoperonic fusion of sucB‐sucC into the pXG‐30sf plasmid (Corcoran et al., 2012). Quantification of the translational fusions revealed that sucC was repressed by GcvB via both the R1 and R3 regions (Figure 4b). While the 156th guanine is not involved in the regulation of sucC, either mutR3, G160C, or C162G mutation in GcvBΔR1 abrogated the repression (Figure 4b), suggesting that the R3 region interacts with the translation initiation region to repress sucC. Because the IntaRNA program predicted alternative interactions between sucC and the GcvB R3 region depending on permissible G‐U wobble basepairs, we tested several compensatory mutations in the sucC translational fusion. One of the mutants, sucC C‐8G, was partially repressed by GcvB, while the deletion of the R1 region alone abrogated this regulation. The repression of sucC C‐8G was restored by GcvBΔR1G160C, verifying the predicted base‐pairing interaction (Figure 4b). These results show that the intraoperonic sucC gene is the direct target of GcvB through a complex interplay of base‐pairing with the R1 and R3 regions.

2.5. New targets regulated solely by GcvB R3 region

Among the R1‐independent GcvB targets (Melamed et al., 2016), the IntaRNA program prediction suggests that the map and ydeE mRNAs can interact with the R3 region (Figure 4c,d). The map gene encodes a peptidase for the cotranslational removal of N‐terminal Met residues from many proteins (Sandikci et al., 2013). The map translational fusion showed modest repression by ectopic expression of GcvB (Figure 4c). While the R1 region had no influence on the repression, the deletion of the R3 region abrogated the repression of map by GcvB, indicating that map is solely regulated by R3. The G156C mutation did not affect the repression, supporting the predicted base‐pairing. The compensatory nucleotide exchange in map C‐8G and GcvB G160C restored the repression (Figure 4c). It is noteworthy that GcvB binds to map in the same manner as with sucC but the strength of repression is stronger in sucC probably due to additional base‐pairing interactions.

The ydeE gene is located adjacent to the mgrS‐mgrR locus and encodes a member of the drug:H+ antiporter family of major facilitator superfamily transporters whose substrate has been proposed to be dipeptides (Hayashi et al., 2010). We found that GcvB repressed the expression of YdeE although the basal translation level was very low (Figure 4d). Deletion of the R1 region alone did not significantly alter the reduction in the ydeE expression, but the repression was abolished by deleting both R1 and R3 regions, indicating that ydeE is indeed regulated by the R3 region. Mutations in the R3 region, except for G156C, disrupted this repression.

2.6. GcvB regulates the ilvLXGMEDA and ivbL‐ilvBN polycistronic mRNAs at multiple sites

The genes encoding the biosynthetic enzymes for Ile/Leu/Val branched‐chain amino acids (BCAAs) are organized into five operons, ilvXGMEDA, ilvBN, ilvIH, ilvYC, and leuABCD (Salmon et al., 2006). At the transcriptional level, ilvXGMEDA and ilvIH operons are regulated by Lrp, whereas ilvC is specifically regulated by IlvY. The ilvG, ilvB, and leuA genes are preceded by transcriptional attenuators, ilvL, ivbL, and leuL, respectively. It has been clarified in Salmonella that ilvC and ilvE are genuine targets of GcvB (Sharma et al., 2011). The GcvB target sequences in ilvC and ilvE are conserved in E. coli. Further inspection of the ilv operon members in the RNA‐seq data sets revealed that ilvX, ilvM, and ilvD genes in the same operon were enriched in Division B (Figure 1). Moreover, the ilvL attenuator region was also ligated with GcvB specifically by the CLASH approach (Figure 1), likely due to the recovery of longer chimeric RNA fragments from the optimized RNase digestion step compared with RIL‐seq and MAPS. In the second operon, both the 5′UTR of ivbL and the ivbL‐ilvB intergenic region were also categorized into Division B (Figure 1). Prediction using the IntaRNA program showed that GcvB interacts with these two polycistronic mRNAs at multiple sites (Figure 5a).

FIGURE 5.

GcvB regulates Ile/Val biosynthetic operon mRNAs at multiple sites. (a) Schematic of ilvLXGMEDA, ilvY‐ilvA, and ivbL‐ilvBN operons. The predicted base‐pairing interactions within the ilv locus in this study are shown as in Figure 2a. (b) GFP reporter assays of new ilv candidate genes. Mean fluorescence relative to the vector control of biological replicates (n > 3) with SD are presented in percentage. Statistical significance was calculated using one‐way ANOVA comparing GcvB and its derivatives with the vector control and denoted as follows: ***p < .001, **p < .005, *p < .05

Using translational fusions, we verified that GcvB indeed repressed the expression of ilvL, ilvM, ilvD, ivbL, and ilvB genes (Figure 5b). The repression of ivbL and ilvM was weaker than that of the other genes, but importantly, we did not observe any significant change in ilvX expression, which precedes the ilvG gene and encodes a small peptide (Hemm et al., 2008, 2010). As predicted, the repression of ilvL, ilvM, ivbL, and ilvB was alleviated by deleting the R1 region (Figure 5b), indicating that GcvB regulates these genes via the R1 region. In contrast, ilvD was strongly repressed by GcvBΔR1. Further deletion or mutations in the R3 region reduced but did not completely abolish the repression (Figure 5b). GcvBΔR1G156C repressed the expression of the ilvD C‐19G mutant more strongly than GcvBΔR1. This result suggests that GcvB represses ilvD through base‐pairing with the R3 seed sequence while the other GcvB regions are also involved in the repression. Overall, GcvB regulates the ilv polycistronic mRNAs by directly binding to at least four sites.

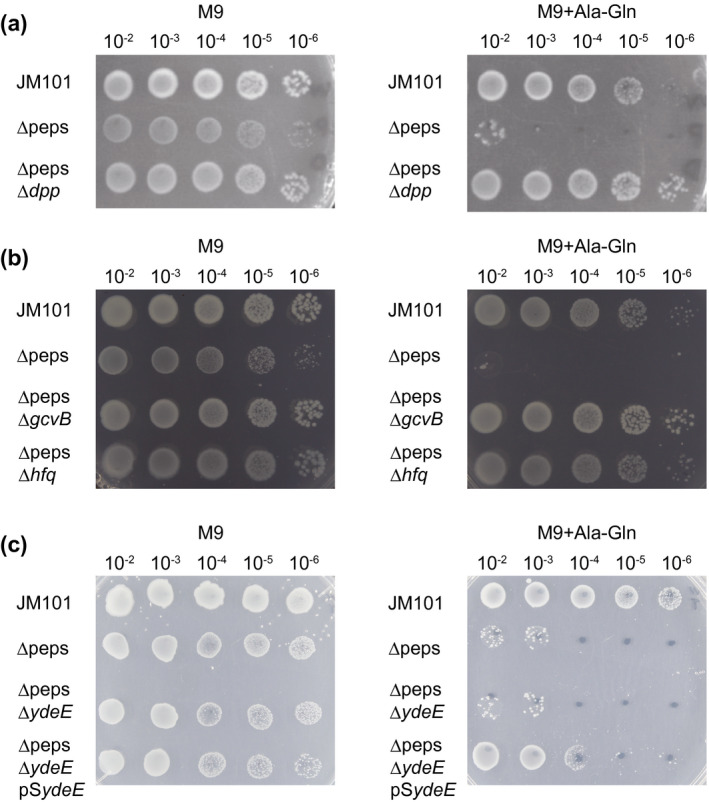

2.7. Insights into the physiological significance of the GcvB regulon

Our verification of CstA and YdeE peptide transporters as GcvB targets prompted us to investigate the phenotypic importance of GcvB in an E. coli strain sensitive to peptides. A mutant strain derived from E. coli JM101 named Δpeps has deletions of multiple peptidase‐encoding genes pepA, pepB, pepD, and pepN (Hayashi et al., 2010), which showed a slightly reduced growth compared with the wild‐type strain in the M9 agar plate and exhibited strong growth inhibition when supplemented with 0.2 mM Ala‐Gln (Figure 6a).

FIGURE 6.

Growth inhibition by Ala‐Gln dipeptide. Growth on M9 plates was compared among the wild‐type JM101 strain, Δpeps strain, and (a) ΔpepsΔdpp, (b) ΔpepsΔgcvB and ΔpepsΔhfq, and (c) ΔpepsΔydeE and ΔpepsΔydeE complemented with pSydeE. Serial dilutions of cells were spotted on M9 plate (left) or M9 plate supplemented with 0.2 mM Ala‐Gln (right) and incubated at 30℃ for 2 days

To identify the effectors and regulators involved in this toxicity, we screened the Δpeps strain for suppressor mutations rescuing the growth in the presence of Ala‐Gln. Comparative genomic analysis of 10 suppressors revealed that 8 strains carried a 95‐kb deletion encompassing the dpp locus encoding the ABC transporter for dipeptides, and the other two mutants acquired a point mutation in dppC and dppD genes, respectively (Table S2). As expected, this phenotype was suppressed by the deletion of dppABCDF (Δdpp) (Figure 6a), indicating that the E. coli cells can restore growth in the presence of Ala‐Gln only by disrupting the Dpp system.

We also noticed that one of the latter two mutants had a mutation in the gcvB gene in addition to dppC (Table S2), suggesting that GcvB is involved in the sensitivity of the Δpeps strain to Ala‐Gln independently from the dpp locus. To confirm this observation, we made ΔpepsΔgcvB and ΔpepsΔhfq double mutants and compared the growth in M9 minimal medium supplemented with 0.2 mM Ala‐Gln. Both double mutants restored growth on the M9 plate in the presence of Ala‐Gln (Figure 6b). Similar growth inhibition was observed upon adding other dipeptides such as Gly‐Gln, Gly‐Tyr, or Ala‐Tyr (Figure S1a), suggesting that this phenotype is independent of the amino acid composition of dipeptides. However, this result is counterintuitive to the fact that GcvB negatively regulates the expression of the dpp operon at the posttranscriptional level via the R1 region (Pulvermacher et al., 2009a; Sharma et al., 2007). This implied that besides dipeptide import, other pathways under the control of GcvB are also involved in the susceptibility to Ala‐Gln. The extracellular concentration of Ala‐Gln was kept constant in the ΔpepsΔgcvB double mutant throughout the growth (Figure S1b), excluding the possibility that Ala‐Gln is processed or modified in the ΔpepsΔgcvB strain.

How does the deletion of gcvB confer E. coli with Ala‐Gln tolerance? We reasoned that if the amount of extracellular Ala‐Gln dipeptide is constant, the ΔpepsΔgcvB double mutant was able to maintain a higher export level of dipeptides than the import level or bypass the toxic effect of dipeptide accumulation in the cell. We first hypothesized that Ala‐Gln dipeptide accumulation impairs amino acid biosynthetic pathways. Remarkably, the supplementation with casamino acids or a combination of single amino acids Gly, Ile, Leu, Val, Arg, and Glu restored the growth of Δpeps in the presence of Ala‐Gln (Figure S1c). This suggests that deletion of gcvB in the Δpeps mutant leads to the derepression of amino acid biosynthesis. Indeed, GcvB directly represses gdhA and several ilv biosynthetic genes (Figures 3 and 5) or indirectly affects the regulon of ArgP and Lrp transcriptional regulators in the presence of effector molecules Arg and Leu, respectively (Kroner et al., 2019; Nguyen Le Minh et al., 2018).

Given that YdeE exhibits the highest activity in dipeptide export (Hayashi et al., 2010) and is the only target of GcvB among the 34 multidrug efflux transporters in E. coli, we hypothesized that deletion of GcvB increases the expression of YdeE to facilitate the excretion of dipeptides. In line with this hypothesis, the ectopic expression of YdeE restored growth of the Δpeps strain in the presence of Ala‐Gln (Figure 6c). In contrast, the ΔpepsΔydeE double mutant exhibited a prolonged lag phase even in the M9 medium without Ala‐Gln and easily generated revertant strains (data not shown), probably due to the accumulation of endogenous dipeptides during preculture in LB medium. Therefore, we propose that GcvB regulates both import and export of dipeptides by regulating dpp and ydeE using the R1 and R3 regions, respectively, to maintain the homeostasis of intracellular dipeptides.

3. DISCUSSION

In this study, from a large number of GcvB interactants in the available RNA‐seq data sets (Figure 1), we identified 21 new target genes of GcvB in E. coli. Hence, the GcvB regulon in E. coli is much larger than expected as we bring the GcvB regulon to 54 genes regulated at either or both RNA and protein levels (Table 1). Moreover, the comparison of the RIL‐seq, CLASH, and MAPS data sets reveals 29 out of 33 previously validated targets (Figure 1), demonstrating that the combination of independent datasets strikingly increases RNA–RNA interactome precision, which is applicable to other sRNA regulators.

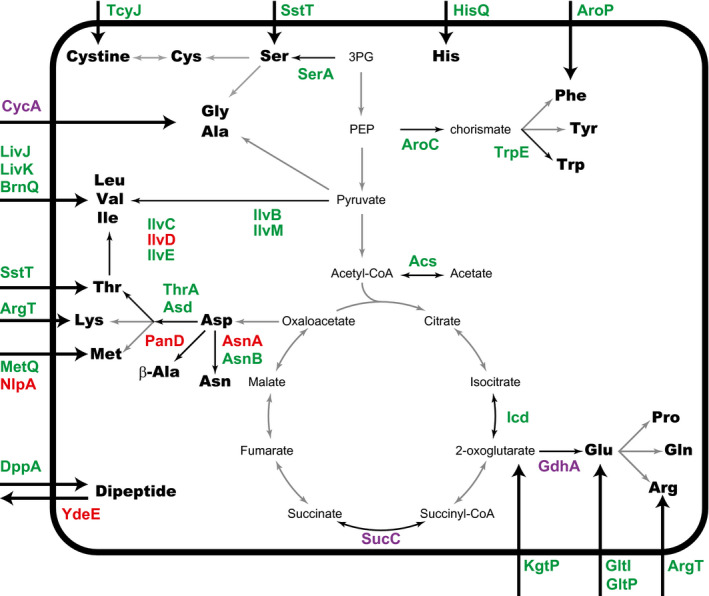

GcvB negatively regulates the expression of several ABC transporters and permeases involved in the import of various amino acids and their precursors (Figure 7). Among the ABC transporter operons, this study identified one additional target in the argT‐hisJQMP operon. Supported by the in vivo interactome data sets, we demonstrate that GcvB represses the expression of hisQ through the R1 seed sequence (Figure 2). We also identified new GcvB targets encoding permeases, namely gltP for Glu/Asp (Schellenberg & Furlong, 1977), aroP for Trp/Tyr/Phe (Brown, 1970, 1971), kgtP for 2‐oxoglutarate (Seol & Shatkin, 1991), and cstA for pyruvate and peptides (Gasperotti et al., 2020; Hwang et al., 2018; Schultz & Matin, 1991). Interestingly, the current list of GcvB regulon covers the import pathways of almost all amino acid substrates except Asn, Pro, and Gln (Figure 7). Regardless of the criteria adopted in this study, previous microarray analysis suggested that putP encoding the Pro symporter was regulated by GcvB via R1 in Salmonella (Sharma et al., 2011). Curiously, Salmonella Δhfq mutant accumulates GlnH, the periplasmic substrate‐binding protein for Gln, as well as OppA, DppA, and GltI in the periplasmic fractions (Sittka et al., 2007), suggesting that glnH is also regulated by Hfq‐dependent sRNAs. Further quantitative studies are required to understand how GcvB controls the import of each amino acid.

FIGURE 7.

GcvB posttranscriptionally regulates multiple amino acid transport and biosynthetic pathways. GcvB targets regulated by either R1, R3, or both are indicated in green, red, or purple font, respectively. In the metabolic pathway map, black arrows represent the reaction steps that are posttranscriptionally regulated by GcvB. Thick arrows represent the GcvB‐regulated transporters for amino acids and dipeptides, some of which adopt multiple substrates, for example, ArgT for Arg/Lys/Orn, CycA for Gly/Ala/β‐Ala/d‐Ala/d‐Ser/cycloserine, and GltI and GltP for Glu/Asp (Table 1)

We show that GcvB also regulates multiple enzymes involved in amino acid biosynthesis and central metabolism (Figure 7). The intermediates of TCA cycle, 2‐oxoglutarate and oxaloacetate, serve as the precursors of Glu and Asp, respectively (Reitzer, 2004). The key enzyme for Glu synthesis, GdhA, catalyzes the NADPH‐dependent amination of 2‐oxoglutarate. Remarkably, our results demonstrate that GcvB uses both the R1 and R3 regions to repress gdhA (Figure 3), emphasizing the importance of posttranscriptional regulation in the balance between amino acid synthesis and central carbon metabolism.

In contrast, Asp is synthesized by the transamination of oxaloacetate from Glu and then converted to Asn, β‐Ala, or the Asp family amino acids Thr/Met/Lys (Figure 7). The asnA, asnB, and panD genes are known to be regulated by GcvB (Lalaouna et al., 2019). The Asp family amino acids are synthesized through the common biosynthetic pathway (Patte, 1996). In this pathway, thrA is repressed by GcvB through the thrL leader region (Fröhlich & Papenfort, 2020; Sharma et al., 2011). The second step in the common pathway is catalyzed by Asp semialdehyde dehydrogenase (Asd), which is posttranscriptionally repressed by GcvB (Figure 2a). Remarkably, the target sites for GcvB and SgrS sRNAs are located upstream of the SD sequence in the asd mRNA and overlap with each other (Bobrovskyy & Vanderpool, 2016).

The polycistronic ilvXGMEDA mRNA encoding the enzymes for Ile/Leu/Val BCAA biosynthesis is redundantly regulated by GcvB (Figure 5). Although E. coli K12 strains contain a frameshift mutation in ilvG (Lawther et al., 1981), the structural genes are transcribed either from the ilvL attenuator region (Lawther & Hatfield, 1980) or from the internal promoter upstream of ilvE (Calhoun et al., 1985). Our reporter assay showed that GcvB differentially repressed the expression of the ilv operon mRNA with a major influence on the ilvD gene. In a genetic context where the whole operon is translated, it may be interesting to analyze how GcvB contributes to the posttranscriptional regulation of each gene in the polycistronic mRNA.

The biosynthesis of aromatic amino acids Trp/Tyr/Phe is regulated at the transcriptional level by the attenuators and by the transcriptional regulators TrpR and TyrR (Pittard & Yang, 2008). This study adds a new layer of regulation to the biosynthesis of aromatic amino acids. At the posttranscriptional level, GcvB represses the expression of aroC, which encodes chorismate synthase, the last enzyme in the common biosynthetic pathway for aromatic amino acids. In addition, GcvB represses the expression of trpE, which encodes anthranilate synthase, the first enzyme in the Trp biosynthetic pathway. As AroP mediates the uptake of three aromatic amino acids, GcvB can control the intracellular levels of aromatic amino acids through both biosynthetic and import pathways.

Furthermore, this study identified some additional metabolic genes regulated by GcvB which are interconnected with amino acid metabolism. GcvB modestly represses the expression of the essential map gene (Ben‐Bassat et al., 1987; Chang et al., 1989). Met aminopeptidase interacts with ribosomes to coordinate the removal of N‐terminal Met from nascent proteins (Sandikci et al., 2013), which is required for the function and stability of most proteins and probably for the recycling of the costly amino acid Met (Hondorp & Matthews, 2006). In addition, GcvB may be involved in recycling short peptides from the peptidoglycan by regulating the mltC gene encoding one of the seven membrane‐bound lytic transglycosylases in E. coli (Artola‐Recolons et al., 2014).

Surprisingly, GcvB represses the expression of the rbsK gene within the rbsDACBK operon, which encodes the d‐ribose transporter RbsABC, the ribose mutarotase RbsD, the ribokinase RbsK involved in the conversion of d‐ribose to d‐ribose 5‐phosphate, and a ProQ‐dependent sRNA RbsZ derived from the 3′UTR of rbsB (Melamed et al., 2020). The transcriptional regulator RbsR is encoded just downstream of rbsK and regulates several genes involved in purine nucleotide synthesis in addition to the rbsDACBK operon (Shimada et al., 2013). It is envisaged that the regulation of rbsK by GcvB coordinates the de novo synthetic pathway of purine nucleotides, where d‐ribose 5‐phosphate is the starting material and Gly provides the C1 units through the GCV system (Jensen et al., 2008).

Our genetic study showed that GcvB is involved in the sensitivity to dipeptides in the peptidase‐deficient E. coli strain. Through the Dpp ABC transporter, E. coli cells import dipeptides which are normally digested into single amino acids by multiple peptidases while the YdeE exporter pumps out the potentially toxic intracellular dipeptides. The deletion of gcvB restored the growth of Δpeps strain in the presence of Ala‐Gln (Figure 6b), suggesting that simultaneous regulation of both Dpp and YdeE by GcvB through different seeds is critical for the homeostasis of intracellular dipeptides (Figure 7). While dppA is a major target of GcvB (Figure S2), we observed very low basal level of ydeE translation, which was further repressed by GcvB almost to the detection limit (data not shown). From a bioengineering point of view, optimization of the GcvB regulatory network will allow the construction of highly efficient producers of Ala‐Gln, an important biomolecule in both health and food industries (Tabata & Hashimoto, 2007).

Most GcvB targets are conserved in Enterobacteriaceae, but Salmonella species lack the metQ‐homolog gene nlpA and the putative LPS kinase gene inaA while they have acquired additional GcvB targets such as STM4351 encoding an Arg‐binding periplasmic protein of an ABC transporter (Table 1). Furthermore, phoP and ydeE mRNAs are not regulated by GcvB in Salmonella because they have lost their complementary sequences to the R3 region (data not shown). A comparative RIL‐seq study will find out more GcvB targets that are both conserved and specific in Salmonella (J. Vogel, personal communication). Hence, identification and comparison of the conserved sRNA regulons among different organisms are valuable to gain more insights into the evolution of bacterial sRNA regulons.

In summary, we expanded the GcvB regulon in E. coli to 54 targets by taking advantage of available RNA‐seq data sets, revealing GcvB as the master regulator of amino acid metabolism and related pathways. Considering the estimated copy number of GcvB, competition between the target mRNAs may be an essential feature of the GcvB regulon (Bossi & Figueroa‐Bossi, 2016; Figueroa‐Bossi & Bossi, 2018). Hence, further investigation into the hierarchy of the GcvB regulon under variable physiological conditions will provide deeper insights into the sRNA regulatory circuits.

4. EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

4.1. Bacterial strains

The strains used in this study are listed in Table S3. Bacterial cells were grown at 37℃ with reciprocal shaking at 180 rpm in an LB Miller medium (BD Biosciences) or an M9 minimal medium supplemented with 0.2% glucose, 10 µg/ml thiamine (Fujifilm Wako Pure Chemical), and 200 µg/ml proline (Fujifilm Wako Pure Chemical). Where required, media were supplemented with antibiotics at the following concentrations: 50 µg/ml ampicillin (Ap), 50 µg/ml kanamycin (Km), and 12.5 µg/ml chloramphenicol (Cm).

Deletion strains were constructed using the lambda Red system as previously described (Datsenko & Wanner, 2000). E. coli gcvB, sroC, dppABCDF, and ydeE were deleted by chromosomal insertion of the pKD4‐ or pKD13‐derived PCR fragments amplified with primer pairs JVO‐0131/JVO‐0132, JVO‐7614/JVO‐7615, dppA‐P1‐R/dppA‐P4‐F, and ydeE‐P1‐R/ydeE‐P4‐F, respectively (Table S4). The 3xFLAG epitope tag at the C‐terminus of gdhA was amplified with the primer pair MMO‐0206/MMO‐0207 using pSUB11 (Uzzau et al., 2001) as a template and was introduced into the chromosome using the lambda Red system (Datsenko & Wanner, 2000). The deletion or insertion in the chromosome was confirmed by PCR, and the mutant loci were moved into the appropriate strains by P1 phage‐mediated transduction.

4.2. Oligonucleotides and plasmids

The oligonucleotides and plasmids used in this study are listed in Tables S4 and S5, respectively. The E. coli GcvB expression plasmid (pPL‐gcvB) was constructed by cloning the XbaI‐digested PCR fragment amplified with 5′‐end phosphorylated JVO‐0237 and MMO‐0086 into the pPL vector with an Ap resistance marker and a p15A ori to express GcvB from a constitutive promoter. Expression plasmids of GcvB deletion mutants were constructed via PCR amplification from the original GcvB expression plasmid using KOD plus ver.2 DNA polymerase (Toyobo), DpnI digestion of the template plasmid, and self‐ligation of purified PCR products. The plasmid‐borne GcvB was mutated by site‐directed mutagenesis via PCR amplification using overlapping primers (Tables S4). The purified PCR products were directly transformed into E. coli DH5α strain after DpnI digestion of the template plasmid. The sequences of the GcvB mutants are shown in Table S6. Translational fusions were constructed as previously described (Corcoran et al., 2012; Urban & Vogel, 2007). The detailed characteristics of reporter plasmid constructions are listed in Table S7, and the inserts of all translational fusions are listed in Table S8. The pSydeE plasmid was constructed by PCR amplification with pSydeE‐5′ and pSydeE‐3′, digestion with EcoRI and BamHI, and cloning into the pSTV28 vector (Takara Bio).

4.3. GFP fluorescence quantification

Biological triplicates of E. coli ΔgcvBΔsroC strains were inoculated from single colonies harboring a combination of the sfgfp translational fusions and the GcvB expression plasmids (Table S5) in 500 µl LB medium containing Ap and Cm in 96 deep‐well plates (Thermo Scientific) and were grown overnight at 37℃ with rotary shaking at 1,200 rpm in DWMax M‐BR‐032P plate shaker (Taitec). The overnight cultures (100 µl) were dispensed into 96‐well optical bottom black microtiter plates (Thermo Scientific) and both optical density at 600 nm (OD600) and fluorescence (excitation at 485 nm and emission at 535 nm with dichroic mirror of 510 nm, fixed gain value of 50) were measured using Spark plate reader (Tecan). The relative fluorescence unit (RFU) was calculated by subtracting the autofluorescence of bacterial cells of the same strain harboring the pPL‐gcvB plasmid and the control plasmid pXG‐0 (Urban & Vogel, 2007).

4.4. Northern blot

Northern blotting was performed according to a previously published protocol (Miyakoshi et al., 2019). Briefly, total RNA was isolated using the TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen), treated with TURBO DNase (Invitrogen), and precipitated with cold ethanol. RNA was quantified using NanoDrop One (Invitrogen). Total RNA (5 µg) was separated by gel electrophoresis on 6% polyacrylamide/7 M urea gels in 1 × TBE buffer for 3 hr at 250 V using Biometra Eco‐Maxi system (Analytik‐Jena). DynaMarker RNA Low II ssRNA fragments (BioDynamics Laboratory) were used as a size marker. RNA was transferred from the gel onto Hybond‐XL nylon membrane (GE Healthcare) by electroblotting for 1 hr at 50 V using the same system. The membrane was crosslinked with transferred RNA by 120 mJ/cm2 UV light, incubated for prehybridization in Rapid‐Hyb buffer (Amersham) at 42℃ for 1 hr, and then incubated for hybridization with a [32P]‐labeled probe JVO‐0749 and JVO‐0322 at 42℃ overnight to detect GcvB and 5S rRNA, respectively. The membrane was washed in three 15‐min steps in 5× SSC/0.1% SDS, 1× SSC/0.1% SDS, and 0.5× SSC/0.1% SDS buffers at 42℃. Signals were visualized on Typhoon FLA7000 scanner (GE Healthcare) and quantified using Image Quant TL software (GE Healthcare).

4.5. Western blot

Western blotting was performed following a previously published protocol (Miyakoshi et al., 2019). Briefly, whole‐cell samples in 1× Laemmli sample buffer (Bio‐Rad) were separated on 10% or 12% TGX gels (Bio‐Rad). Proteins were transferred onto Hybond PVDF membranes (GE Healthcare), and membranes were blocked for 10 min in Bullet Blocking One buffer (Nacalai Tesque) and were incubated overnight at 4℃ with monoclonal anti‐FLAG (Sigma–Aldrich #F1804; 1:5,000), monoclonal anti‐GFP (Sigma–Aldrich SAB2702197; 1:5,000), and polyclonal anti‐GroEL (Sigma–Aldrich #G6532; 1:10,000) antibodies diluted in Bullet Blocking One buffer. Membranes were washed three times for 15 min in 1 × TBST buffer at RT. Then membranes were incubated for 1 hr at RT with secondary antimouse or antirabbit HRP‐linked antibodies (Cell Signaling Technology #7076 or #7074; 1:5,000) diluted in Bullet Blocking One buffer and were washed three times for 15 min in 1 × TBST buffer. Chemiluminescent signals were developed using Amersham ECL Prime reagents (GE Healthcare), visualized on LAS4000 (GE Healthcare), and quantified using Image Quant TL software.

4.6. Dipeptide resistance assay

Overnight cultures of E. coli strains in LB medium were washed twice with sterile saline, and the cells were serially diluted to 10−2, 10−3, 10−4, 10−5, and 10−6. The dilutions of cells were spotted on M9 plates containing 1.5% agar (Kokusan Chemical) supplemented with 0.2 mM dipeptides, Ala‐Gln, Ala‐Tyr, Gly‐Gln, or Gly‐Tyr (Kyowa Hakko Bio). The plates were incubated at 30℃ for 2 days.

4.7. Quantification of Ala‐Gln

Cells were grown in M9 glucose minimal medium supplemented with 0.2 mM Ala‐Gln. At the indicated times, cultures were centrifuged and the supernatant was filtrated through a 0.22 µm filter. After appropriate dilution, the samples were subjected to dipeptide analysis. Dipeptide analysis was performed using the UHPLC amino acid analysis system (Nexera X2, Shimadzu) equipped with a Shim‐pack Velox C18 column (Shimadzu) and a fluorescence detector (RF‐20Axs, Shimadzu). On‐line precolumn derivatization of the primary amino group of the dipeptide with o‐phthaldialdehyde and 3‐mercaptopropionic acid was performed by coinjection function of the auto‐sampler. Separation was performed with mobile phase A (17 mM KH2PO4, 3 mM K2HPO4) and mobile phase B (water:acetonitrile:methanol = 15:45:40) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conceived and designed the experiments: MM and MW. Performed the experiments: MM, HO, ML, TK, YT, KI, MO, and MW. Analyzed the data: MM, HO, ML, TK, YT, KI, MO, TI, NI, and MW. Wrote the paper: MM, HO, ML, and MW.

Supporting information

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Research in the Miyakoshi group was supported by JSPS KAKENHI (Grant numbers JP15H06528, JP16H06190, JP19H03464, and JP16H06279 [PAGS]), The Institute for Fermentation Osaka, Takeda Science Foundation, and Waksman Foundation of Japan. Research in the Wachi Laboratory was supported by JSPS KAKENHI (grant number JP25660088). MM is supported by Tomizawa Jun‐ichi & Keiko Fund of Molecular Biology Society of Japan for Young Scientists. ML is supported by JSPS Postdoctoral Fellowship for Research in Japan. The authors thank Gianluca Matera and Jörg Vogel for sharing their data, Teppei Morita for helpful comments, Natsuko Shirai for technical assistance in reporter analysis, and the Open Research Facilities for Life Science and Technology (Tokyo Institute of Technology) for technical assistance in dipeptide analysis.

Miyakoshi, M. , Okayama, H. , Lejars, M. , Kanda, T. , Tanaka, Y. , Itaya, K. , et al (2022) Mining RNA‐seq data reveals the massive regulon of GcvB small RNA and its physiological significance in maintaining amino acid homeostasis in Escherichia coli . Molecular Microbiology, 117, 160–178. 10.1111/mmi.14814

Masatoshi Miyakoshi and Haruna Okayama should be considered joint first authors.

Contributor Information

Masatoshi Miyakoshi, Email: mmiyakoshi@md.tsukuba.ac.jp.

Masaaki Wachi, Email: mwachi@bio.titech.ac.jp.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon request.

REFERENCES

- Andreassen, P.R. , Pettersen, J.S. , Szczerba, M. , Valentin‐Hansen, P. , Møller‐Jensen, J. & Jørgensen, M.G. (2018) sRNA‐dependent control of curli biosynthesis in Escherichia coli: McaS directs endonucleolytic cleavage of csgD mRNA. Nucleic Acids Research, 46, 6746–6760. 10.1093/nar/gky479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arrieta‐Ortiz, M.L. , Hafemeister, C. , Shuster, B. , Baliga, N.S. , Bonneau, R. & Eichenberger, P. (2020) Inference of bacterial small RNA regulatory networks and integration with transcription factor‐driven regulatory networks. mSystems, 5, e00057‐20. 10.1128/mSystems.00057-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Artola‐Recolons, C. , Lee, M. , Bernardo‐García, N. , Blázquez, B. , Hesek, D. , Bartual, S.G. et al. (2014) Structure and cell wall cleavage by modular lytic transglycosylase MltC of Escherichia coli . ACS Chemical Biology, 9, 2058–2066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben‐Bassat, A. , Bauer, K. , Chang, S.Y. , Myambo, K. , Boosman, A. & Chang, S. (1987) Processing of the initiation methionine from proteins: properties of the Escherichia coli methionine aminopeptidase and its gene structure. Journal of Bacteriology, 169, 751–757. 10.1128/jb.169.2.751-757.1987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianco, C.M. , Fröhlich, K.S.A. & Vanderpool, C.K. (2019) Bacterial cyclopropane fatty acid synthase mRNA is targeted by activating and repressing small RNAs. Journal of Bacteriology, 201, e00461‐19. 10.1128/JB.00461-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobrovskyy, M. & Vanderpool, C.K. (2016) Diverse mechanisms of post‐transcriptional repression by the small RNA regulator of glucose‐phosphate stress. Molecular Microbiology, 99, 254–273. 10.1111/mmi.13230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bossi, L. & Figueroa‐Bossi, N. (2016) Competing endogenous RNAs: a target‐centric view of small RNA regulation in bacteria. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 14, 775–784. 10.1038/nrmicro.2016.129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown, K.D. (1970) Formation of aromatic amino acid pools in Escherichia coli K‐12. Journal of Bacteriology, 104, 177–188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown, K.D. (1971) Maintenance and exchange of the aromatic amino acid pool in Escherichia coli . Journal of Bacteriology, 106, 70–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calhoun, D.H. , Wallen, J.W. , Traub, L. , Gray, J.E. & Kung, H.F. (1985) Internal promoter in the ilvGEDA transcription unit of Escherichia coli K‐12. Journal of Bacteriology, 161, 128–132. 10.1128/jb.161.1.128-132.1985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang, S.Y.P. , McGary, E.C. & Chang, S. (1989) Methionine aminopeptidase gene of Escherichia coli is essential for cell growth. Journal of Bacteriology, 171, 4071–4072. 10.1128/jb.171.7.4071-4072.1989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H. , Previero, A. & Deutscher, M.P. (2019) A novel mechanism of ribonuclease regulation: GcvB and Hfq stabilize the mRNA that encodes RNase BN/Z during exponential phase. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 294, 19997–20008. 10.1074/jbc.RA119.011367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coornaert, A. , Chiaruttini, C. , Springer, M. & Guillier, M. (2013) Post‐transcriptional control of the Escherichia coli PhoQ‐PhoP two‐component system by multiple sRNAs involves a novel pairing region of GcvB. PLoS Genetics, 9, 12–14. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corcoran, C.P. , Podkaminski, D. , Papenfort, K. , Urban, J.H. , Hinton, J.C.D. & Vogel, J. (2012) Superfolder GFP reporters validate diverse new mRNA targets of the classic porin regulator, MicF RNA. Molecular Microbiology, 84, 428–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datsenko, K.A. & Wanner, B.L. (2000) One‐step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K‐12 using PCR products. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 97, 6640–6645. 10.1073/pnas.120163297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desgranges, E. , Caldelari, I. , Marzi, S. & Lalaouna, D. (2020) Navigation through the twists and turns of RNA sequencing technologies: application to bacterial regulatory RNAs. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) ‐ Gene Regulatory Mechanisms, 1863, 194506. 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2020.194506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faigenbaum‐Romm, R. , Reich, A. , Gatt, Y.E. , Barsheshet, M. , Argaman, L. & Margalit, H. (2020) Hierarchy in Hfq chaperon occupancy of small RNA targets plays a major role in their regulation. Cell Reports, 30, 3127–3138. 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.02.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figueroa‐Bossi, N. & Bossi, L. (2018) Sponges and predators in the small RNA world. Microbiology Spectrum, 6. 10.1128/microbiolspec.RWR-0021-2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fröhlich, K.S. & Papenfort, K. (2020) Regulation outside the box: new mechanisms for small RNAs. Molecular Microbiology, 114, 363–366. 10.1111/mmi.14523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasperotti, A. , Göing, S. , Fajardo‐Ruiz, E. , Forné, I. & Jung, K. (2020) Function and regulation of the pyruvate transporter CstA in Escherichia coli . International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 21, 9068. 10.3390/ijms21239068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georg, J. , Lalaouna, D. , Hou, S. , Lott, S.C. , Caldelari, I. , Marzi, S. et al. (2020) The power of cooperation: experimental and computational approaches in the functional characterization of bacterial sRNAs. Molecular Microbiology, 113, 603–612. 10.1111/mmi.14420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghrist, A.C. , Heil, G. & Stauffer, G.V. (2001) GcvR interacts with GcvA to inhibit activation of the Escherichia coli glycine cleavage operon. Microbiology, 147, 2215–2221. 10.1099/00221287-147-8-2215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulliver, E.L. , Wright, A. , Lucas, D.D. , Mégroz, M. , Kleifeld, O. , Schittenhelm, R.B. et al. (2018) Determination of the small RNA GcvB regulon in the Gram‐negative bacterial pathogen Pasteurella multocida and identification of the GcvB seed binding region. RNA, 24, 704–720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi, M. , Tabata, K. , Yagasaki, M. & Yonetani, Y. (2010) Effect of multidrug‐efflux transporter genes on dipeptide resistance and overproduction in Escherichia coli . FEMS Microbiology Letters, 304, 12–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heil, G. , Stauffer, L.T. & Stauffer, G.V. (2002) Glycine binds the transcriptional accessory protein GcvR to disrupt a GcvA/GcvR interaction and allow GcvA‐mediated activation of the Escherichia coli gcvTHP operon. Microbiology, 148, 2203–2214. 10.1099/00221287-148-7-2203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemm, M.R. , Paul, B.J. , Miranda‐Ríos, J. , Zhang, A. , Soltanzad, N. & Storz, G. (2010) Small stress response proteins in Escherichia coli: proteins missed by classical proteomic studies. Journal of Bacteriology, 192, 46–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemm, M.R. , Paul, B.J. , Schneider, T.D. , Storz, G. & Rudd, K.E. (2008) Small membrane proteins found by comparative genomics and ribosome binding site models. Molecular Microbiology, 70, 1487–1501. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06495.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hondorp, E.R. & Matthews, R.G. (2006) Methionine. EcoSal Plus, 2. 10.1128/ecosalplus.3.6.1.7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hör, J. , Gorski, S.A. & Vogel, J. (2018) Bacterial RNA biology on a genome scale. Molecular Cell, 70, 785–799. 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.12.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hör, J. , Matera, G. , Vogel, J. , Gottesman, S. & Storz, G. (2020) Trans‐acting small RNAs and their effects on gene expression in Escherichia coli and Salmonella enterica . EcoSal Plus, 9. 10.1128/ecosalplus.ESP-0030-2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, S. , Choe, D. , Yoo, M. , Cho, S. , Kim, S.C. , Cho, S. et al. (2018) Peptide transporter CstA imports pyruvate in Escherichia coli K‐12. Journal of Bacteriology, 200, e00771‐17. 10.1128/JB.00771-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iosub, I.A. , van Nues, R.W. , McKellar, S.W. , Nieken, K.J. , Marchioretto, M. , Sy, B. et al. (2020) Hfq CLASH uncovers sRNA‐target interaction networks linked to nutrient availability adaptation. elife, 9, e54655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, K.F. , Dandanell, G. , Hove‐Jensen, B. & Willemoës, M. (2008) Nucleotides, nucleosides, and nucleobases. EcoSal Plus, 3. 10.1128/ecosalplus.3.6.2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jørgensen, M.G. , Nielsen, J.S. , Boysen, A. , Franch, T. , Møller‐Jensen, J. & Valentin‐Hansen, P. (2012) Small regulatory RNAs control the multi‐cellular adhesive lifestyle of Escherichia coli . Molecular Microbiology, 84, 36–50. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2012.07976.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kavita, K. , de Mets, F. & Gottesman, S. (2018) New aspects of RNA‐based regulation by Hfq and its partner sRNAs. Current Opinion in Microbiology, 42, 53–61. 10.1016/j.mib.2017.10.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keseler, I.M. , Gama‐Castro, S. , Mackie, A. , Billington, R. , Bonavides‐Martínez, C. , Caspi, R. et al. (2021) The EcoCyc database in 2021. Frontiers in Microbiology, 12, 2098. 10.3389/fmicb.2021.711077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keseler, I.M. , Mackie, A. , Santos‐Zavaleta, A. , Billington, R. , Bonavides‐Martínez, C. , Caspi, R. et al. (2017) The EcoCyc database: reflecting new knowledge about Escherichia coli K‐12. Nucleic Acids Research, 45, D543–D550. 10.1093/nar/gkw1003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King, A.M. , Vanderpool, C.K. & Degnan, P.H. (2019) sRNA Target Prediction Organizing Tool (SPOT) integrates computational and experimental data to facilitate functional characterization of bacterial small RNAs. mSphere, 4, e00561‐18. 10.1128/mSphere.00561-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroner, G.M. , Wolfe, M.B. & Freddolino, P.L. (2019) Escherichia coli Lrp regulates one‐third of the genome via direct, cooperative, and indirect routes. Journal of Bacteriology, 201, e00411–e418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lalaouna, D. , Eyraud, A. , Devinck, A. , Prévost, K. & Massé, E. (2019) GcvB small RNA uses two distinct seed regions to regulate an extensive targetome. Molecular Microbiology, 111, 473–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawther, R.P. , Calhoun, D.H. , Adams, C.W. , Hauser, C.A. , Gray, J. & Hatfield, G.W. (1981) Molecular basis of valine resistance in Escherichia coli K‐12. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 78, 922–925. 10.1073/pnas.78.2.922 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawther, R.P. & Hatfield, G.W. (1980) Multivalent translational control of transcription termination at attenuator of ilvGEDA operon of Escherichia coli K‐12. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 77, 1862–1866. 10.1073/pnas.77.4.1862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H.J. & Gottesman, S. (2016) sRNA roles in regulating transcriptional regulators: Lrp and SoxS regulation by sRNAs. Nucleic Acids Research, 44, 6907–6923. 10.1093/nar/gkw358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann, M. , Wright, P.R. & Backofen, R. (2017) IntaRNA 2.0: enhanced and customizable prediction of RNA‐RNA interactions. Nucleic Acids Research, 45, W435–W439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McArthur, S.D. , Pulvermacher, S.C. & Stauffer, G.V. (2006) The Yersinia pestis gcvB gene encodes two small regulatory RNA molecules. BMC Microbiology, 6, 52. 10.1186/1471-2180-6-52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melamed, S. , Adams, P.P. , Zhang, A. , Zhang, H. & Storz, G. (2020) RNA‐RNA interactomes of ProQ and Hfq reveal overlapping and competing roles. Molecular Cell, 77, 411–425. 10.1016/j.molcel.2019.10.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melamed, S. , Peer, A. , Faigenbaum‐Romm, R. , Gatt, Y.E. , Reiss, N. , Bar, A. et al. (2016) Global mapping of small RNA‐target interactions in bacteria. Molecular Cell, 63, 884–897. 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.07.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyakoshi, M. , Chao, Y. & Vogel, J. (2015) Cross talk between ABC transporter mRNAs via a target mRNA‐derived sponge of the GcvB small RNA. The EMBO Journal, 34, 1478–1492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyakoshi, M. , Matera, G. , Maki, K. , Sone, Y. & Vogel, J. (2019) Functional expansion of a TCA cycle operon mRNA by a 3′ end‐derived small RNA. Nucleic Acids Research, 47, 2075–2088. 10.1093/nar/gky1243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modi, S.R. , Camacho, D.M. , Kohanski, M.A. , Walker, G.C. & Collins, J.J. (2011) Functional characterization of bacterial sRNAs using a network biology approach. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 108, 15522–15527. 10.1073/pnas.1104318108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen Le Minh, P. , Velázquez Ruiz, C. , Vandermeeren, S. , Abwoyo, P. , Bervoets, I. & Charlier, D. (2018) Differential protein‐DNA contacts for activation and repression by ArgP, a LysR‐type (LTTR) transcriptional regulator in Escherichia coli . Microbiological Research, 206, 141–158. 10.1016/j.micres.2017.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olejniczak, M. & Storz, G. (2017) ProQ/FinO‐domain proteins: another ubiquitous family of RNA matchmakers? Molecular Microbiology, 104, 905–915. 10.1111/mmi.13679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patte, J.C. (1996) Biosynthesis of threonine and lysine. In: Neidhardt, F. (Ed.) Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology. American Society for Microbiology, pp. 528–541. [Google Scholar]

- Pittard, J. & Yang, J. (2008) Biosynthesis of the aromatic amino acids. EcoSal Plus, 3. 10.1128/ecosalplus.3.6.1.8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulvermacher, S.C. , Stauffer, L.T. & Stauffer, G.V. (2008) The role of the small regulatory RNA GcvB in GcvB/mRNA posttranscriptional regulation of oppA and dppA in Escherichia coli . FEMS Microbiology Letters, 281, 42–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulvermacher, S.C. , Stauffer, L.T. & Stauffer, G.V. (2009a) Role of the Escherichia coli Hfq protein in GcvB regulation of oppA and dppA mRNAs. Microbiology, 155, 115–123. 10.1099/mic.0.023432-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulvermacher, S.C. , Stauffer, L.T. & Stauffer, G.V. (2009b) The small RNA GcvB regulates sstT mRNA expression in Escherichia coli . Journal of Bacteriology, 191, 238–248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulvermacher, S.C. , Stauffer, L.T. & Stauffer, G.V. (2009c) Role of the sRNA GcvB in regulation of cycA in Escherichia coli . Microbiology, 155, 106–114. 10.1099/mic.0.023598-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reitzer, L. (2004) Biosynthesis of glutamate, aspartate, asparagine, L‐alanine, and D‐alanine. EcoSal Plus, 1. 10.1128/ecosalplus.3.6.1.3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saliba, A.‐E. , C Santos, S. & Vogel, J. (2017) New RNA‐seq approaches for the study of bacterial pathogens. Current Opinion in Microbiology, 35, 78–87. 10.1016/j.mib.2017.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salmon, K.A. , Yang, C.‐R. & Hatfield, G.W. (2006) Biosynthesis and regulation of the branched‐chain amino acids. EcoSal Plus, 2. 10.1128/ecosalplus.3.6.1.5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandikci, A. , Gloge, F. , Martinez, M. , Mayer, M.P. , Wade, R. , Bukau, B. et al. (2013) Dynamic enzyme docking to the ribosome coordinates N‐terminal processing with polypeptide folding. Nature Structural and Molecular Biology, 20, 843–850. 10.1038/nsmb.2615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schellenberg, G.D. & Furlong, C.E. (1977) Resolution of the multiplicity of the glutamate and aspartate transport systems of Escherichia coli . Journal of Biological Chemistry, 252, 9055–9064. 10.1016/S0021-9258(17)38344-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz, J.E. & Matin, A. (1991) Molecular and functional characterization of a carbon starvation gene of Escherichia coli . Journal of Molecular Biology, 218, 129–140. 10.1016/0022-2836(91)90879-B [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seol, W. & Shatkin, A.J. (1991) Escherichia coli kgtP encodes an alpha‐ketoglutarate transporter. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 88, 3802–3806. 10.1073/pnas.88.9.3802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, C.M. , Darfeuille, F. , Plantinga, T.H. & Vogel, J. (2007) A small RNA regulates multiple ABC transporter mRNAs by targeting C/A‐rich elements inside and upstream of ribosome‐binding sites. Genes and Development, 21, 2804–2817. 10.1101/gad.447207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, C.M. , Papenfort, K. , Pernitzsch, S.R. , Mollenkopf, H.J. , Hinton, J.C.D. & Vogel, J. (2011) Pervasive post‐transcriptional control of genes involved in amino acid metabolism by the Hfq‐dependent GcvB small RNA. Molecular Microbiology, 81, 1144–1165. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07751.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimada, T. , Kori, A. & Ishihama, A. (2013) Involvement of the ribose operon repressor RbsR in regulation of purine nucleotide synthesis in Escherichia coli . FEMS Microbiology Letters, 344, 159–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silveira, A.C.G. , Robertson, K.L. , Lin, B. , Wang, Z. , Vora, G.J. , Vasconcelos, A.T.R. et al. (2010) Identification of non‐coding RNAs in environmental vibrios. Microbiology, 156, 2452–2458. 10.1099/mic.0.039149-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sittka, A. , Pfeiffer, V. , Tedin, K. & Vogel, J. (2007) The RNA chaperone Hfq is essential for the virulence of Salmonella typhimurium . Molecular Microbiology, 63, 193–217. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05489.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stauffer, G.V. (2004) Regulation of serine, glycine, and one‐carbon biosynthesis. EcoSal Plus, 1. 10.1128/ecosalplus.3.6.1.2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stauffer, L.T. & Stauffer, G.V. (2005) GcvA interacts with both the α and σ subunits of RNA polymerase to activate the Escherichia coli gcvB gene and the gcvTHP operon. FEMS Microbiology Letters, 242, 333–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storz, G. , Vogel, J. & Wassarman, K.M. (2011) Regulation by small RNAs in bacteria: expanding frontiers. Molecular Cell, 43, 880–891. 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.08.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabata, K. & Hashimoto, S.‐I. (2007) Fermentative production of L‐alanyl‐L‐glutamine by a metabolically engineered Escherichia coli strain expressing L‐amino acid alpha‐ligase. Applied and Environment Microbiology, 73, 6378–6385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Updegrove, T.B. , Zhang, A. & Storz, G. (2016) Hfq: the flexible RNA matchmaker. Current Opinion in Microbiology, 30, 133–138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]