Abstract

Polyimides were obtained in 99 % yield in under 1 h through the “beat and heat” approach, involving solvent‐free vibrational ball milling and a thermal treatment step. The influence of a plethora of additives was explored, such as Lewis acids, Lewis bases, and dehydrating agents, and the mechanochemical reaction was identified to run via a polyamic acid intermediate. The protocol was adopted to a range of substrates inaccessible through solution‐based processes, including perylene tetracarboxylic acid dianhydride and melamine. Furthermore, quantum chemical calculations were conducted to identify the water removal as the crucial step in the reaction mechanism. The presented method is substantially faster and more versatile than the solution‐based process.

Keywords: beat and heat, green chemistry, mechanochemistry, polymers, solvent-free

Beat and heat: Polyimides are a sought‐after class of polymers for their high‐stability bonds. However, their synthesis usually relies on toxic solvents or lengthy temperature treatments. A quick method is developed to synthesize polyimides through mechanochemistry, and the influence of typical accelerants used under these circumstances is investigated. Additionally, a range of possible building blocks for this synthesis is presented.

Introduction

Polyimides (PI) are a class of polymers that are defined by their strong covalent C−N bonds, which result in high thermal and chemical resistance while retaining superior mechanical properties and being lightweight. [1] Furthermore, they have customizable electronic properties. [2] This sparks interest for applications in many different fields such as aerospace engineering, microelectronics and energy storage. [3]

For the latter, especially cross‐linked polyimides impress with their superior chemical and thermal stability and insolubility in most media. [4] Their syntheses, however, are often time‐consuming and lack scalability. [5] Usually reported protocols rely upon the usage of high‐boiling solvents or solid‐state processes at high temperatures.[ 6 , 7 , 8 ] Although some works rely on a hydrothermal synthesis, all of them have the drawback of needing long reaction times between 12 h and 5 days, often utilizing expensive or hazardous precursors or solvents limiting their potential industrial application. [9]

One way to overcome these drawbacks is using mechanochemistry. The art of performing chemical reactions via mechanical forces has been utilized since the stone age but has only been described in greater detail within the latter half of the 20th century. [10] In the modern era, mortar and pestle have been widely replaced by ball mills and in some cases even extruders. Mechanochemistry involves reactions from all parts of organic, inorganic polymer, materials, or pharmaceutical chemistry. [11] Karak et al. showed for related polyimines how amines can be activated to produce crystalline polymers under mild conditions. [12] They used para‐toluene sulfonic acid (pTsOH) as template in a compounding process. Furthermore, low‐molecular‐weight imides based on the perylene moiety were developed. [13] Cao et al. used an extruder to produce perylene dyes at mild conditions without usage of toxic solvents. [13] This demonstrates the potential of the mechanochemical pathway for high stability polymers and low solubility precursors.

Herein, we develop a protocol for the synthesis of polyimides in high yields and short reaction times of usually less than 1 h (Figure 1). As a model reaction the polymerization between pyromellitic dianhydride (PMDA) and 1,3,5‐tri(4‐aminophenyl)benzene (TAB) was chosen. Furthermore, we expanded the concept to different polymer architectures. This was done by employing linear anhydride linking agents and varying the amine node from a diamine to a triamine onto a tetragonal building block. Lastly, we substituted the expensive amine building‐unit for melamine and synthesized a novel PI structure from perylenetetracarboxylic acid dianhydride and melamine.

Figure 1.

Formation of polymeric structure under mechanochemical influence. Our results show that a thermal step is necessary to reach a closed imide ring.

Results and Discussion

Synthesis of the model compound PI‐COF‐2

First, we tried to synthesize the model compound PI‐COF‐2 by milling 500 mg of stoichiometric amounts PMDA (241 mg, 1,1 mmol) and TAB (259 mg, 0,73 mmol) together with 3.5 g of the bulking agent sodium chloride in a MM500 mixer mill for 20 min with 22 10 mm zirconia milling balls (Table 1, entry 1). [6] The resulting greenish powder was washed with water, ethanol, and acetone, and dried at 80 °C. 13C magic angle spinning (MAS) NMR spectroscopy exhibits peaks at 167, 137, and 126 ppm, corresponding to carboxylic group derivatives, substituted aromatic carbon atoms, and unsubstituted aromatic carbons, respectively. (Figure S1 in the Supporting Information). This validates that a polymer consisting of both monomer species was yielded. The IR spectrum shows several signals, most importantly an intensive signal at 3000 cm−1, corresponding to a NH vibration, a shifted CO vibration at 1655 cm−1, and shifted CN vibrations at 1536 as well as at 1247 cm−1 (Figure 2). Elemental analysis reveals a hydrogen content of 4.23 %, which is more than the theoretical value of 3 % (Table S3). All these observations support our hypothesis of a not fully closed imide ring. This is further strengthened by the thermogravimetric analysis (TGA), which shows weight loss of 10 % up to 200 °C (Figure S4). This poly(amic acid) (PAA) intermediate is well described in the literature and has various applications itself because of higher solubility compared to the polyimide. [14]

Table 1.

Overview of parameter variation studies, described in detail in Table S1.[a]

|

Entry |

Sample‐ID |

Unique feature |

Yield [%] |

|---|---|---|---|

|

1 |

PAA‐1 |

– |

93 |

|

2 |

PAA‐2 |

2.5 min milling |

71 |

|

3 |

PAA‐3 |

5 min milling |

77 |

|

4 |

PAA‐4 |

10 min milling |

88 |

|

5 |

PAA‐5 |

15 min milling |

92 |

|

6 |

PAA‐6 |

480 min milling |

73 |

|

7 |

PAA‐7 |

4× DABCO+NaCl bm |

10 |

|

8 |

PAA‐8 |

4× FeCl3+NaCl bm |

59 |

|

9 |

PAA‐9 |

MgSO4 bm |

99 |

|

10 |

PAA‐10 |

P2O5 bm |

93 |

|

11 |

PAA‐11 |

planetary ball mill |

48 |

|

12 |

PAA‐12 |

pTsOH pre‐milling |

31 |

|

13 |

PAA‐13 |

35 Hz milling |

82 |

|

14 |

PI‐1 |

30 min 200 °C heating |

80 |

|

15 |

PI‐1 |

MgSO4 bm, 30 min 200 °C heating |

99 |

[a] PAA=poly(amic acid), PI=polyimide, bm=bulking material, DABCO=1,4‐diazabicyclo[2.2.2]octane

Figure 2.

IR spectra of the model compound produced from pyromellitic dianhydride (PMDA, bottom) and 1,3,5‐tri(4‐aminophenyl)benzene (TAB, middle) after subsequent washing with water, ethanol, and acetone, and drying at 80 °C.

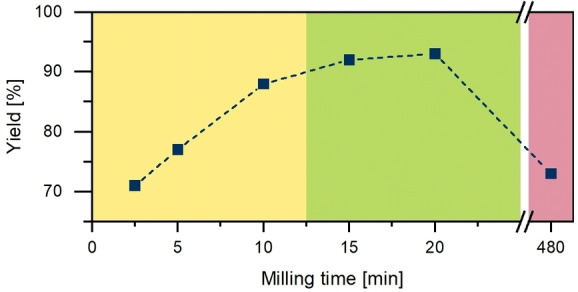

Next, the milling time was varied from 2.5 min (PAA‐2, Table 1) up to 8 h (PAA‐6, Table 1). Figure 3 shows the yield versus reaction time. The observed behavior is typical for polymerization reactions. In the first regime chain growth is dominant (Figure 3, yellow), in the second regime the polymer network is built (Figure 3, green), but partially broken by the mechanical forces in the mill, whereas at long reaction times the destructive forces exceed the formation of new bonds (Figure 3, red). This is further supported by IR spectroscopy, where PAA‐6 shows a significantly different pattern to PAA‐1 to PAA‐5 (Figure S3). The CO vibration diminishes almost completely, indicating a significant structural change.

Figure 3.

Yield of the polymer formation from PMDA and TAB with NaCl as bulking agent. Three regions are visible: chain growth (yellow), polymer network (green), and breakage (red).

After seeing no benefit of prolonged milling times, we further investigated various additives that are traditionally employed as drying agents in organic synthesis, as well as Lewis acids and bases (PAA‐7–PAA‐10). We hypothesized, that these would fulfill the purpose of either drawing the chemically bound water and thus accelerating the reaction beyond the amic acid step or accelerating it through Lewis acidity. None of the additives were sufficiently strong to achieve the desired effect to form the polyimide. All resulting polymers showed the typical green color of the poly(amic acid), which was confirmed with IR spectroscopy (Figure S3). Indeed, the yield with phosphorous pentoxide as additive was 100 %; however, IR spectra showed none of the characteristic vibrations of polyimides. Using DABCO as a Lewis base led to a drastically diminished yield of 10 %. FeCl3 as a Lewis acid had similar impact as phosphorous pentoxide, which might be caused by the oxidative nature of both additives. Yet, this impact of a Lewis base further supports a similar reaction mechanism to solvent chemistry. There, besides Brønsted acids and bases, Lewis acids are commonly used to weaken the bond between the carbonyl C and the anhydride O, whereas Lewis bases show an adverse effect. Using a milder drying agent, namely MgSO4, led to an improved yield, supporting this hypothesis further, because the removal of water is quintessential as a last step. [15]

Following this, mechanochemical parameters such as increasing the milling frequency and changing the milling mode from vibrational to planetary ball milling were investigated (PAA‐11–PAA‐13). Choosing a higher milling frequency has a slightly adverse effect on yield, decreasing it from 93 to 82 %. Planetary ball milling allows for a higher introduction of energy, and consequently it has a similar effect like longer milling time or higher milling frequency. Apparently, the poly(amic acid) structure is prone to break under high mechanical stress. One way to distribute this stress within the powder is the technique of liquid‐assisted grinding (LAG). [16] In this case, 1 mL of a variety of organic solvents as well as inorganic acids were added to the reaction mixture. The idea was that the organic solvents would promote the reaction through solvation effects, whereas the acids should serve the purpose of catalyzing the reaction similarly to solution‐based imidization processes. While some solvents did not have any significant effect on the yield, protic solvents and mineral acids decreased the yield up to about 60 % (Table S2). This leads to the hypothesis that the deprotonation of the amine building unit is crucial for the reaction. With this in mind, we tried to synthesize the model compound via a route Karak et al. described for similarly structured enamine compounds (PAA‐12). [12] They milled the amine compound together with pTsOH to form an activated structure between amine and pTsOH that formed an enamine readily afterwards. However, the reaction did not produce any insoluble product. The reason for this may be a more stable intermediate between the amine unit and the pTsOH.

The breakthrough was finally achieved by a method called “beat and heat”, where the freshly ground powder is heated to thermally accelerate the activated educts. With this the desired changes in the IR pattern (Figure 2) of imide formation were visible. We identified a temperature of 200 °C for at least 30 min as the least time to fully convert the poly(amic acid). This heating step is accompanied by a color change from green to a yellow ochre color. This suspected polyimide powder was subsequently analyzed with elemental analysis, showing a much higher C/H ratio of 24.7 close to the theoretical value (Table S4). It might be possible that moisture from the atmosphere adsorbs onto the structure. Energy‐dispersive X‐ray spectroscopy (EDS) measurements of both PAA‐1 and PI‐1 particles showed homogeneous distribution of nitrogen, oxygen, and carbon (Figures S11 and S12). 13C solid‐state NMR spectroscopy shows a higher signal‐to‐noise ratio compared to PAA‐1 with an additional shoulder around 140 ppm (Figure S2). As both the PAA as well as the PI structure are very similar, it is impossible to draw a direct conclusion from this technique; however, it confirms that no degradation during the heating step occurred. TGA was conducted to show significant thermal stability up to 450 °C (Figure S5). Interestingly, PI‐1 has a lower mass loss between 200–450 °C than PAA‐1. This supports our hypothesis that during the prolonged heating step at 200 °C more stable bonds form. Similarly to before we exchanged the NaCl bulking agent for MgSO4 to increase the yield from 80 to 99 %. To study the textural properties of both materials, PI and PAA, electron microscopy and EDS were conducted. High‐resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM) images of the MgSO4 enhanced (PI‐1 ) sample revealed two different morphologies for the 80 °C dried sample (Figure 4, left). Some particles had a sheet‐like appearance, while others had a crumpled appearance with rough surface. After the heat treatment at 200 °C, no particles of the former morphology could be found. Furthermore, the observed particles were significantly reduced in size (Figure 4, right). Additional N2 physisorption analysis shows a very similar surface texture (Table S5, Figure S8), where sample PAA‐1 has a specific surface area of 130 m2 g−1 and sample PI‐1 one of 170 m2 g−1. This can be caused by the loss of water during the heating step. Both samples exhibit type II isotherms for macroporous substances. [17] In contrast to the literature‐reported PI‐COF‐2 our synthesized PI‐1 does not show any crystallinity (Figure S10). [6] This is most likely a result of the impact forces occurring during the ball milling process.

Figure 4.

TEM images of samples from the model compound after washing and drying at 80 °C (left) and subsequent heat treatment at 200 °C (right).

Variation of building units

To show the versatility of the proposed process, a variation of building units was tested (Table 2). Once again, we did not observe PI formation under pure mechanochemical conditions. By utilizing the additional heating step, we were able to synthesize a range of polyimides from a variation of anhydrides and mellitic acid. Before, we chose the highly reactive anhydride function to promote the reaction as it is commonly done in solvent chemistry. To demonstrate the versatility of our process, we changed to a monomer with carboxylic acid functions, mellitic acid (Table 2, entry 2). The yield of only 37 % shows, that indeed, the carboxylic acid is less reactive, further emphasizing our hypothesis of a similar reaction pathway as in solvent chemistry. However, this opens this route for materials with interesting applications. [18] Furthermore, we were able to synthesize a polymer from perylene tetracarboxylic acid dianhydride (PTCDA) in good yields of 67 %. This monomer is less reactive in solution‐based processes due to its poor solubility. [19] Any solubility‐enhancing side functions that are usually grafted onto the perylene‐core are superfluous in our process. However, we noticed a downwards trend in yield with increasing anhydride size (Table 2). Additionally, PI‐2 produced a significantly lower yield than the PI produced from anhydrides, showing that the process without anhydride functions is possible but probably slower. This may also be an issue for the bigger anhydrides.

Table 2.

Impact of monomer variation on polymer yield.[a]

|

Entry |

Sample‐ID |

Anhydride |

Amine |

Yield [%] |

SSA [m2 g−1] |

Color |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1 |

PI‐1 |

|

|

99 |

169 |

yellow |

|

2 |

PI‐2 |

|

|

37 |

114 |

ochre |

|

3 |

PI‐3 |

|

|

83 |

72 |

dark grey |

|

4 |

PI‐4 |

|

|

67 |

38 |

red |

|

5 |

PI‐5 |

|

|

91 |

151 |

beige |

|

6 |

PI‐6 |

|

|

43 |

14 |

white |

|

7 |

PI‐7 |

|

|

57 |

231 |

black |

|

8 |

PI‐8 |

|

|

98 |

154 |

purple |

|

9[b] |

PI‐9 |

|

|

90 |

0 |

dark green |

[a] Reaction conditions if not stated otherwise: 0.5 g stoichiometric monomer mixture, 3.5 g MgSO4 (bulking material), 22×10 mm balls ZrO2 in a 45 mL ZrO2 vessel for 20 min. [b] Reaction was performed in a 45 mL ZrO2 vessel inside a Pulverisette7 by Fritsch at 800 rpm with MgSO4 as bulking material.

The amine functionality was varied as well, starting from a linear building unit to a tetragonal block. The yields for p‐phenylenediamine and for tetrakis(4‐aminophenyl)methane were in a similar range as observed before, while the energy‐deficient 4,4′,4′′‐triaminotriphenylamine has only about 60 % yield. Most interestingly, we were able to produce a polyimide from melamine, a usually unreactive amine compound. Even though the yield was quite low, this encouraged us to produce an imide from PTCDA and melamine. Changing to these less reactive substrates required us to adapt the previously established reaction conditions. For these reasons, we selected high‐energy milling. The yield of 90 % (Table 2, entry 9) shows that the balance between polymer growth and breakage as discussed before is highly dependent on the reactivity of monomers. Again, this is similar to the thermal reaction mechanism, where these monomers require much harsher reaction conditions compared to their smaller counterparts.[ 7 , 20 ] Our successful synthesis is a major step forward in high‐dimensional polymers, as insoluble and cheap reactants can be utilized. This also circumvents the toxicity of most amines used in polymers. With exception of sample PI‐9 all sample were amorphous. Only sample PI‐9 showed peaks between 10 and 30° 2θ (Figure S10). Usually, polymers made through mechanochemistry only exhibit short‐range order. This implies that the structure may form during the thermal treatment step.

Shaking versus baking

A question still unanswered for this reaction has puzzled mechanochemists for some time. Why do certain reactions perform extremely well under mechanochemical conditions, while others need an additional thermal treatment step? Usually, condensation reactions proceed readily in ball mills. This has frequently been shown in literature. [21] In most of these examples, the reaction proceeds through a concerted mechanism. Yet, in this case, the overall condensation reaction consists of two reaction steps. In the first step, the anhydride ring opens after nucleophilic attack by an electron‐rich amine, forming the amic acid intermediate through an addition reaction. The second step, the imide formation, is an intramolecular elimination of water after nucleophilic attack by the amide. In this case, the reaction stops after the first step, and the second step does not proceed in the ball mill without additional heating.

From a conventional wet‐chemical perspective one would either make steric hindrance or energetic effects responsible. We would exclude the first, as imide formation is already possible in solution and mechanochemistry is even of advantage when it comes to sterically demanding substrates. For instance, García and co‐workers brought sterically encumbered adamantoid phosphazanes into mechanochemical reaction, which are not processable in solution. [22] The reason for the difficult imide formation must therefore be a thermodynamic one. As even prolonged milling (PAA‐6, i. e., 480 min) gives a yield of 0 % towards the imide, we exclude the total energy introduced to be decisive. The consequent assumption would be that the energy of an individual mechanochemical momentum is not sufficient in the mechanochemical approach to surpass the activation energy needed for a nucleophilic attack by the amide, which is a poor nucleophile. However, even milling parameters allowing for the highest amount of introduced energy under lab conditions (i. e., MM500 at 35 Hz, high‐energy mill Pulverisette7) do not give any yield for imide formation. Please note that such conditions provide energies that are very high and have proven in the past to be capable of synthesizing high‐energy materials such as carbides, sulfides, and ternary nitrides mechanochemically. [23]

Indeed, it seems that thermal energy is favored over mechanical energy for conducting the second reaction step. Interestingly, James and co‐workers have formed imide bonds via extrusion and came to a similar observation, that is, that below 100 °C no imide bond is formed (yield of 0 %), while at 110 °C imide bonds are formed with a yield of >99 %. [13] This observation is a strong argument against the popular hot spot theory, which is often used for explaining reactivity of mechanochemical reaction. [24] According to the hot spot theory, high temperatures (i. e., >1000 °C) occur during the short period of milling ball collision. Since we observe 0 % yield even after 480 min of milling, no such high‐energy event could have occurred.

Looking further at the reaction mechanism quantum chemical calculations were conducted. The authors are fully aware that those calculations are normally done for gaseous systems and therefore lattice energies are neglected. Nevertheless, those calculations ratify the chemical conception a chemist has of enthalpy and entropy.

We note that the addition reaction of the two‐step condensation (amic acid formation) proceeds under five‐ring opening. This reduces the ring stress and is enthalpically but not entropically favored (Figure S14); the second reaction step (imide formation), however, proceeds under five‐ring formation and H2O elimination. It is entropy‐driven but enthalpically unfavored (Figure 5, Figure S14). [25] Although the Gibbs free energy is negative for the last step, the reaction does not proceed mechanochemically as the entropy term cannot be utilized because water cannot be removed from the sealed milling vessel. Heating the reaction mixture in an open system instead allows for effective water removal, whereas milling inside a closed vessel is allowing water to remain in the system. This was further proven by milling a sample of heat‐treated PI‐1 (final imide) with an excess amount of water (Sample PI‐PAA). By doing so, we observed a shift in the CO‐vibration (1717 vs. 1777 cm−1) caused by the back reaction to the poly(amic acid) (Figure S13). Apparently, under mechanochemical conditions, the reaction of the imide back to the amic acid is easily possible in the presence of water. This is a reversibility not observed in solution‐based chemistry, where polyimides, together with polyaramides, are known for their extreme chemical and thermal resistance and the ability to recycle such polymers is thus extremely limited. Having the possibility to reopen and close strong C−N bonds mechanochemically will opens enormous possibility for recycling or even repairing the polymer network of these materials.

Figure 5.

Enthalpies of imidization reaction calculated by means of PW6B95D3/6‐31G*//PW6B95D3/6‐31G*. [25]

Conclusions

We presented a straightforward route to synthesize various polyimides with different connectivities. In contrast to the traditional route, this way eliminates the need for toxic, high‐boiling solvents and produces the desired product in a fraction of the time formerly needed due to a so called “beat and heat” protocol with a short 30 min heating step. Interestingly, this route is also able to utilize organic acids for imide formation, whereas the traditional wet‐chemistry route was solely relying on anhydrides. This opens the possibility to further employ polyimides for lower‐cost applications by significantly reducing the costs. The use of melamine as a feasible amine linker was shown, further reducing potential costs. Additionally, we analyzed the reaction pathway using theoretical calculations to understand imide formation as an entropy‐driven reaction. Thus, new pathways are opened in recycling of high‐stability condensation polymers like polyimides or polyaramides.

Experimental Section

Organic chemicals were supplied by TCI Chemicals. Salts were purchased from Grüssing. All chemicals were used without further purification. Zirconium dioxide (Type ZY‐S) milling balls with a diameter of 10 mm were purchased from Sigmund Lindner GmbH. The average weight of one milling ball is 3.19±0.05 g.

Powder X‐ray diffraction (PXRD) measurements were conducted using a LynxEye detector operating at 30 kV acceleration voltage and 10 mA emission current using CuKα radiation (λ=1.54184 Å) on a Bruker D2 Phaser diffractometer. The observed range included 10–70° 2θ. HRTEM was carried out with a JEM 2800 microscope by JEOL. It was equipped with a Schottky‐type emission source working at 200 kV and a Gatan OneView camera (4k×4k, 25 FPS) to obtain images with a resolution of 0.09 nm. EDS elemental mapping was performed using double silicon drift detectors (SDD), with a solid angle of 0.98 steradians with 100 mm2 of detection area. TGA was conducted using a Pyris6 thermogravimetric analyzer by Perkin Elmer. Nitrogen gas with a flow rate of 20 mL min−1 was chosen, while a ramp of 10 K min−1 up to 950 K was applied. To evaluate surface texture, nitrogen physisorption measurements were carried out at 77 K with a Quadrasorb SI from Quantachrome. The total pore volume was determined at p/p 0=0.95. Specific surface areas were calculated from the Brunauer‐Emmet‐Teller (BET) equation between 0.02 and 0.25 p/p 0. 13C MAS‐NMR spectroscopy was performed on the Bruker DSX 400 spectrometer, equipped with a VTN double resonance max. 35 kHz 2.5 mm MAS 1H XBB probe head. The samples were rotated at 12 kHz and measured with ramped 1H–13 C cross polarization. As reference for the peak assignments, an adamantane probe was utilized. Fourier‐transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy was carried out on a SHIMADZU IR Spirit with QATR‐S ATR unit. Each sample was measured with 15 scans with a resolution of 4 in the range from 400 to 4000 cm−1. Quantum chemical calculations were used to calculate the energies depicted in Figure 5. All energies were obtained by means of B3LYP in combination with the 6‐31G* basis set. The nature of the stationary points was determined by subsequent frequency calculations. None of the stationary points exhibit imaginary frequencies. As it is not absolutely clear if transition states in mechanochemistry are the same as in conventional chemistry no transition states were calculated.

Experiments were carried out in mixer mills using zirconium dioxide milling material. Multiple amines and anhydrides were used in varying amounts adding up to 0.5 g. 3.5 g of bulking material was added.

Proof of principle in the MM‐500: 241 mg (1.10 mmol, 1.5 equiv.) PMDA and 259 mg (0.73 mmol, 1 equiv.) TAB were placed in a 50 mL zirconia milling jar with 22 zirconia milling balls of 10 mm diameter followed by 3.5 g of sodium chloride. The reaction mixture was then placed in the holders of the RETSCH MM500 and was mixed at 25 Hz for 20 min. Subsequently, the reaction mixture was transferred into a pore 4 frit and washed with 50 mL portions of 3× water, 1× ethanol, and 2× acetone. The resulting solid was then dried at 80 °C overnight. Experimental details for the variation of milling conditions follow the aforementioned conditions and can be found in greater detail in Tables S1 and S2.

High‐energy milling in the Pulverisette7: Similarly to the protocol described before, PMDA and TAB were placed into a 45 mL zirconia jar with 22 10 mm ZrO2 milling balls and 3.5 g NaCl. Afterwards they were milled at 800 rpm for 20 min inside a Fritsch Pulverisette 7 before being washed in a similar manner as the other samples.

Reopening of polyimide (PI‐PAA): 241 mg (1.10 mmol, 1.5 equiv.) PMDA and 259 mg (0.73 mmol, 1 equiv.) TAB were placed in a 50 ml zirconia milling jar with 22 zirconia milling balls of 10 mm diameter followed by 3.5 g of sodium chloride. The reaction mixture was then placed in the holders of the RETSCH MM500 and was mixed at 25 Hz for 20 min. The reaction mixture was then poured into a glass beaker and placed into a 200 °C oven for 30 min. Afterwards, it was milled with 3.96 mL H2O (0.22 mol, 30 equiv.) for additional 20 min. Subsequently, the reaction mixture was transferred into a pore 4 frit and washed with 50 mL portions of 3×water, 1×ethanol, and 2×acetone. The resulting solid was then dried at 80 °C overnight to yield 0.451 g of a green‐yellow powder.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supporting Information

Acknowledgements

L.B. and S.G gratefully acknowledge the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) for support of the Mechanocarb project (award number 03SF0498). L.B. acknowledges the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft for funding the Project 469290370. Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

T. Rensch, S. Fabig, S. Grätz, L. Borchardt, ChemSusChem 2022, 15, e202101975.

References

- 1. Meador M. A., Annu. Rev. Mater. Sci. 1998, 28, 599. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chopin S., Chaignon F., Blart E., Odobel F., J. Mater. Chem. 2007, 17, 4139. [Google Scholar]

- 3.

- 3a. van der Jagt R., Vasileiadis A., Veldhuizen H., Shao P., Feng X., Ganapathy S., Habisreutinger N. C., van der Veen M. A., Wang C., Wagemaker M., van der Zwaag S., Nagai A., Chem. Mater. 2021, 33, 818; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3b. Zhang M., Niu H., Wu D., Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2018, 39, 1800141; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3c. Ling Q.-D., Chang F.-C., Song Y., Zhu C.-X., Liaw D.-J., Chan D. S.-H., Kang E.-T., Neoh K.-G., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 8732; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3d. Sun B., Li X., Feng T., Cai S., Chen T., Zhu C., Zhang J., Wang D., Liu Y., ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 51837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ni H., Liu J., Wang Z., Yang S., J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2015, 28, 16. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Xiang Z., Cao D., Dai L., Polym. Chem. 2015, 6, 1896. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fang Q., Zhuang Z., Gu S., Kaspar R. B., Zheng J., Wang J., Qiu S., Yan Y., Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 4503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Treier M., Richardson N. V., Fasel R., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 14054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wang T., Xue R., Chen H., Shi P., Lei X., Wei Y., Guo H., Yang W., New J. Chem. 2017, 41, 14272. [Google Scholar]

- 9.

- 9a. Baumgartner B., Puchberger M., Unterlass M. M., Polym. Chem. 2015, 6, 5773; [Google Scholar]

- 9b. Kim T., Park B., Lee K. M., Joo S. H., Kang M. S., Yoo W. C., Kwak S. K., Kim B.-S., ACS Macro Lett. 2018, 7, 1480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.

- 10a. Tan D., García F., Chem. Soc. Rev. 2019, 48, 2274; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10b. Andersen J., Mack J., Green Chem. 2018, 20, 1435. [Google Scholar]

- 11.

- 11a. Colacino E., Porcheddu A., Halasz I., Charnay C., Delogu F., Guerra R., Fullenwarth J., Green Chem. 2018, 20, 2973; [Google Scholar]

- 11b. Colacino E., Porcheddu A., Charnay C., Delogu F., React. Chem. Eng. 2019, 4, 1179; [Google Scholar]

- 11c. Mocci R., Colacino E., de Luca L., Fattuoni C., Porcheddu A., Delogu F., ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 2100; [Google Scholar]

- 11d. Joshi H., Ochoa-Hernández C., Nürenberg E., Kang L., Wang F. R., Weidenthaler C., Schmidt W., Schüth F., Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2020, 309, 110566; [Google Scholar]

- 11e. Ohn N., Shin J., Kim S. S., Kim J. G., ChemSusChem 2017, 10, 3529; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11f. Troschke E., Grätz S., Lübken T., Borchardt L., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 6859; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11g. Crawford D. E., Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2017, 13, 65; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11h. Batzdorf L., Fischer F., Wilke M., Wenzel K.-J., Emmerling F., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 1799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Karak S., Kandambeth S., Biswal B. P., Sasmal H. S., Kumar S., Pachfule P., Banerjee R., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 1856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cao Q., Crawford D. E., Shi C., James S. L., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.

- 14a. Song Z., Zhan H., Zhou Y., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 8444; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14b. Suzuki M., Kakimoto M., Toru K., Imai Y., Iwamoto M., Hino T., Chem. Lett. 1986, 395. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wu Z., Ban F., Boyd R. J., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 3642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Friščić T., Trask A. V., Jones W., Motherwell W. D. S., Angew. Chem. 2006, 118, 7708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Thommes M., Kaneko K., Neimark A. V., Olivier J. P., Rodriguez-Reinoso F., Rouquerol J., Sing K. S., Pure Appl. Chem. 2015, 87, 1051. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wagner S., Dai H., Stapleton R. A., Illingsworth M. L., Siochi E. J., High Perform. Polym. 2006, 18, 399. [Google Scholar]

- 19.

- 19a. Maschita J., Banerjee T., Savasci G., Haase F., Ochsenfeld C., Lotsch B. V., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 15750; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19b. Zhang C., Zhang S., Yan Y., Xia F., Huang A., Xian Y., ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 13415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chu S., Wang Y., Guo Y., Zhou P., Yu H., Luo L., Kong F., Zou Z., J. Mater. Chem. 2012, 22, 15519. [Google Scholar]

- 21.

- 21a. Grätz S., Borchardt L., RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 64799; [Google Scholar]

- 21b. Haferkamp S., Fischer F., Kraus W., Emmerling F., Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2017, 13, 2010; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21c. Crawford D. E., Miskimmin C. K. G., Albadarin A. B., Walker G., James S. L., Green Chem. 2017, 19, 1507; [Google Scholar]

- 21d. Pascu M., Ruggi A., Scopelliti R., Severin K., Chem. Commun. 2013, 49, 45; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21e. Pickhardt W., Wohlgemuth M., Grätz S., Borchardt L., J. Org. Chem. 2021, 86, 14011.; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21f. Beldon P. J., Fábián L., Stein R. S., Thirumurugan A., Cheetham A. K., Friščić T., Angew. Chem. 2010, 122, 9834; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21g. Nicholson W. I., Barreteau F., Leitch J. A., Payne R., Priestley I., Godineau E., Battilocchio C., Browne D. L., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 21868; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21h. Yuan W., Garay A. L., Pichon A., Clowes R., Wood C. D., Cooper A. I., James S. L., CrystEngComm 2010, 12, 4063; [Google Scholar]

- 21i. Stolar T., Grubešić S., Cindro N., Meštrović E., UŽarević K., Hernández J. G., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 12727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Shi Y. X., Xu K., Clegg J. K., Ganguly R., Hirao H., Friščić T., García F., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 12736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.

- 23a. Jacobsen C. J. H., Zhu J. J., Lindeløv H., Jiang J. Z., J. Mater. Chem. 2002, 12, 3113; [Google Scholar]

- 23b. Ali M., Basu P., J. Alloys Compd. 2010, 491, 581; [Google Scholar]

- 23c. Tetzlaff D., Pellumbi K., Baier D. M., Hoof L., Shastry Barkur H., Smialkowski M., Amin H. M. A., Grätz S., Siegmund D., Borchardt L., Apfel U.-P., Chem. Sci. 2020, 11, 12835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.

- 24a. Ma X., Yuan W., Bell S. E. J., James S. L., Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 1585; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24b. Fischer F., Wenzel K.-J., Rademann K., Emmerling F., Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2016, 18, 23320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.M. J. Frisch, G. W. Trucks, H. B. Schlegel, G. E. Scuseria, M. A. Robb, J. R. Cheeseman, G. Scalmani, V. Barone, G. A. Petersson, H. Nakatsuji, X. Li, M. Caricato, A. V. Marenich, J. Bloino, B. G. Janesko, R. Gomperts, B. Mennucci, H. P. Hratchian, J. V. Ortiz, A. F. Izmaylov, J. L. Sonnenberg, Williams, F. Ding, F. Lipparini, F. Egidi, J. Goings, B. Peng, A. Petrone, T. Henderson, D. Ranasinghe, V. G. Zakrzewski, J. Gao, N. Rega, G. Zheng, W. Liang, M. Hada, M. Ehara, K. Toyota, R. Fukuda, J. Hasegawa, M. Ishida, T. Nakajima, Y. Honda, O. Kitao, H. Nakai, T. Vreven, K. Throssell, J. A. Montgomery Jr., J. E. Peralta, F. Ogliaro, M. J. Bearpark, J. J. Heyd, E. N. Brothers, K. N. Kudin, V. N. Staroverov, T. A. Keith, R. Kobayashi, J. Normand, K. Raghavachari, A. P. Rendell, J. C. Burant, S. S. Iyengar, J. Tomasi, M. Cossi, J. M. Millam, M. Klene, C. Adamo, R. Cammi, J. W. Ochterski, R. L. Martin, K. Morokuma, O. Farkas, J. B. Foresman, D. J. Fox, Gaussian 16 Rev. C.01, Wallingford, CT, 2016.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supporting Information