Summary

Background

The pace of the COVID-19 pandemic poses an unprecedented challenge to the evidence-to-decision process. Latin American countries have responded to COVID-19 by introducing interventions to both mitigate the risk of infection and to treat cases. Understanding how evidence is used to inform government-level decision-making at a national scale is crucial for informing country and regional actors in ongoing response efforts.

Objectives

This study was undertaken between February-May 2021 and aims to characterise the best available evidence (BAE) and assess the extent to which it was used to inform decision-making in 21 Latin American countries, in relation to pharmaceutical (PI) and non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPI) related to COVID-19, including the use of therapeutics (corticosteroids, hydroxychloroquine/chloroquine and ivermectin), facemask use in the community setting and the use of diagnostic tests as a requirement for international travel.

Method

A three-phase methodology was used to; (i) characterise the BAE for each intervention using an umbrella review, (ii) identify government-level decisions for each intervention through a document review and (iii) assess the use of evidence to inform decisions using a novel adapted framework analysis.

Findings

The BAE is characterized by 17 living and non-living systematic reviews as evolving, and particularly uncertain for NPIs. 107 country-level documents show variation in both content and timing of decision outcomes across intervention types, with the majority of decisions taken at a time of evidence uncertainty, with only 5 documents including BAE. Seven out of eight key indicators of an evidence-to-decision process were identified more frequently among PIs than either NPI of facemask use or testing prior to travel. Overall evidence use was reported more frequently among PIs than either NPI of facemask use or travel testing (92%, 28% and 29%, respectively).

Interpretation

There are limitations in the extent to which evidence use in decision-making is reported across the Latin America region. Institutionalising this process and grounding it in existing and emerging methodologies can facilitate the rapid response in an emergency setting.

Funding

No funding was sourced for this work.

Keywords: COVID-19, Evidence, Decision-making

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

There is a growing body of evidence which suggests that substantial barriers exist which limit the extent to which research informs public health policy, particularly in the emergency setting.1,2 The evidence-base for understanding COVID-19 and its control continues to expand at an unprecedented rate, with over 9500 clinical trials and observational studies published or pre-printed by May 2021.3,4 Whilst numerous policy-tracking initiatives provide live updates of the measures taken by global governments to respond to the pandemic, the extent to which emerging scientific evidence informs both clinical management and population health decisions is limited.5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10

Added value of this study

This study suggests that the extent to which scientific evidence is reported to be used to inform both clinical management and population health decisions has been limited in the Latin American region, particularly in the early stages of the pandemic in the context of uncertain evidence. Clinical management decision-making reports both the use and assessment of evidence to a greater extent than public health decisions pointing to a fundamental difference in the decision-making process for medical versus public health decisions.

Implications of all the available evidence

A more transparent, institutionalised process for using evidence within clinical and public health decisions is urgently needed for ongoing COVID-19 response efforts.

Alt-text: Unlabelled box

Introduction

There is a well-founded consensus that policy-making in public health should be informed by evidence.1,11,12 Basing decisions on the best available evidence (BAE) allows for policy which is timely, impactful, relevant and effective.13 The COVID-19 pandemic has exposed the unique complexities of using evidence to inform public health policy in a global emergency setting.

Research-decision maker relationships have been required to adapt to the pace of the pandemic, its high stakes and many uncertainties.14 The evidence base for COVID-19 control measures is in near-constant flux, with evidence evolving and emerging at unprecedented speed. This introduces a novel challenge to traditional models of knowledge translation. In a pandemic setting, rapid and effective decision-making is crucial to saving lives, therefore, policies are often produced simultaneously to the evidence which should inform them.15

A growing body of evidence identifies that substantial barriers exist that limit or restrict the extent to which evidence is translated into policy.16, 17, 18 Factors such as multiple competing influences on policy-makers, as well as a gap in objectives between researchers and decision-makers, inadequate communication of research results and insufficient technical capacity or understanding among policy-makers of scientific data have all contributed.19,17 Specifically, in the emergency setting, factors such as previous experience of outbreaks, the influence of the media, economic interests and international pressure are identified as either disruptors or facilitators to this evidence transition process.2,20 There has been an effort to strengthen the use of evidence in national policies and guidelines within Latin America in recent years, although less specifically for the emergency setting. The extent to which evidence has informed decision-making for both clinical management and public health policy during the COVID-19 pandemic in Latin America is as yet unexamined.

Since April 2020, the Americas region has been significantly impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic.21 Over 27% of global COVID-19 deaths by June 2020 were occurring in the Latin America and Caribbean (LAC) region, and by May 2021 the Latin America and Caribbean region reached the ‘tragic milestone’ of 1 million deaths, 89% of which occurred in only five Latin American countries.22 Similar to regions across the world, there has been variation in government responses to the COVID-19 pandemic among the LAC countries, as well as differences in health system capacities and emergency preparedness.23,24

Before the roll-out of COVDI-19 vaccines, the COVID-19 emergency response in the region was focused on implementing pharmaceutical and non-pharmaceutical measures.22,25 The evidence for various antiviral or immunomodulator treatments for COVID-19 has evolved throughout the pandemic, with emerging results from interventional and observational studies. The evidence for infection prevention measures has arguably been less forthcoming, despite the widespread uptake of measures such as facemask use and physical distancing across the region and globally. This study, therefore, focuses on selected interventions which form part of this ongoing two-pronged approach to COVID-19 control. Highlighting the extent to which the BAE informs decision-making in the region may provide important insights into the capacities and priorities that govern decision-making processes in the emergency setting.

This study aims to (i) characterise the BAE for COVID-19 interventions as given by published systematic reviews and understand the evolution of this evidence-base over time, (ii) summarise the decisions taken by national governments in the LAC region in relation to the use of pharmaceutical (PI) and non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPI) and (iii) analyse the extent to which evidence was used to inform these decisions.

Methods

Scope of the study

Interventions which both treat and mitigate the risk of COVID-19 infection were selected in discussion with members of the PAHO COVID-19 Incident Management System Team. This ensured that findings were directly relevant to ongoing COVID-19 response efforts in the region. Therapeutics selected include: corticosteroids, hydroxychloroquine/chloroquine and ivermectin. These were selected as the therapeutics most tested in clinical trials as well as those most widely available and in use in the region at the time of this study. NPIs included: (i) the use of face masks in the community setting and (ii) the use of diagnostic tests as a requirement for international travel. These were selected as they are widely implemented measures and particularly sensitive to changes in pandemic progression.

Three-phase methodology

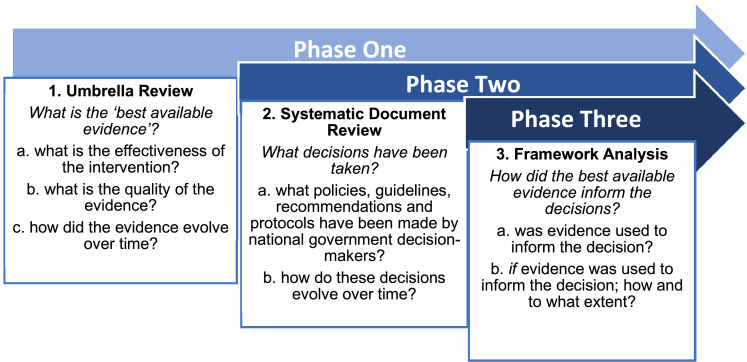

This study follows a three-phase design, as set out below in Figure 1. This allows each study objective to be addressed sequentially and for the findings of each stage to inform the next.

Figure 1.

Three-phase methodology.

Phase One: what is the best available evidence (BAE) for the selected COVID-19 interventions?

Phase One characterises the BAE for each of the selected COVID-19 interventions in terms of (i) the effectiveness of the intervention and (ii) the quality of evidence for its use, and (iii) how this evolved over time between December 2019 and March 2021. An umbrella review was undertaken, a methodology developed by the Joanna Briggs Institute which synthesises evidence reviews.26

Selection criteria

Living systematic reviews (LSR) published between December 2019 and March 2021 were included. Specific selection criteria for each intervention are provided in Appendix 1. LSRs were used given they are regularly updated to incorporate newly available evidence and have been a crucial tool for building the COVID-19 evidence-base.27,28 LSRs were identified using the Living Overview of Evidence platform (L.OVE) hosted by the Epistemonikos Foundation.29,30 Where LSRs were not found, systematic reviews (SRs) published within the same period were included using the same eligibility criteria (see below). No language restriction was applied. Included outcomes differed by intervention category; for therapeutics, outcomes included all-cause mortality in COVID-19 suspected, probable or confirmed cases in adults (>18 years) only. For face mask use in the community, setting outcomes included mask effect (mask vs no mask only), and confirmed or suspected infection rate (viral illness, COVID or coronavirus infections). For the NPI of the use of diagnostic tests as a requirement for international travel outcomes included outbreak delay, traveller infection rate and detection rate in travellers.

Eligibility criteria

Eligible reviews reported the effectiveness of the intervention, either by providing an overall effect estimate or an overall author conclusion where a lack of data limited pooled quantitative analysis. Only reviews which reported the quality of the evidence using a standardised quality assessment tool such as GRADE were deemed eligible.31 However, to balance the aims of characterising the BAE across time with the quality of the evidence, LSRs which did not report a quality assessment were included where no other eligible LSR existed at that point in time. Equally, where multiple eligible LSRs were available at various points in time, only reviews which added new evidence by including new individual studies (to avoid duplication) or different relevant outcomes were included. Narrative or commentary reviews were excluded.

Search strategy

The search was conducted between March 1-12, 2021 using the following databases: PubMed, Cochrane Library, Scopus, Epistemonikos, Virtual Health Library, Norwegian Institute of Public Health Live Map of COVID-19 Evidence, WHO Global Literature of COVID-19 and EPPI-Centre Living Map of COVID-19. Search terms were related to each of the three interventions and broadly include; (‘COVID-19’, ‘SARS-CoV-2’, ‘novel coronavirus’) and (‘corticosteroids’, ‘hydroxychloroquine’, ‘ivermectin’, ‘masks’, ‘travel test’). A full list of search terms is available in Appendix 2.

Data extraction and synthesis

Data was extracted into a pre-designed Excel template which included: (i) study author and title, (ii) dates of search interval and publication, (iii) outcome measured, (iv) effectiveness measure (as defined above) (v) quality assessment measure reported and tool used. Given the objective is to characterise rather than summarise the evidence, the extracted data was qualitatively synthesised to provide an overview of the two characterisation criteria (effectiveness and quality of the intervention). Effectiveness measures were categorised as per the review authors' conclusions as ‘beneficial’, ‘harmful’, ‘no difference’ or ‘uncertain,’ a format implemented by a number of the included current COVID-19 LSRs.32,33 ‘No difference’ is defined as evidence that the intervention provides no benefit or causes no harm compared to either standard care (in the case of therapeutic interventions) or no intervention. Quality of evidence was categorised as ‘high’, ‘moderate’, ’low’ or ‘very low’ as per the GRADE methodology applied by authors, and where non-GRADE tools were used by authors, the given quality assessment measure of the alternative tool was extracted.31

Phase Two: what decisions have been made by national government decision-makers related to interventions to control the COVID-19 pandemic?

Phase Two summarises the decisions made by national government decision-makers related to interventions to control the COVID-19 pandemic in 21 Latin American countries (listed in Appendix 3). A systematic search for ‘decision documents,’ defined as documents which contain any form of decision outcome (eg. policy, recommendation, guideline, protocol, resolution) published between December 2019 and March 2021 by country-level government decision-makers within Latin America region was undertaken between March-May 2021. The aim was to understand the scope of decisions made across the region, rather than identify and present which decisions were made by each country. This is largely because at the time of the study there were not enough available documents published by each country for a balanced analysis, and because the study aims to understand regional trends over time rather than define country-specific action, as regional findings can be more useful in informing regional-level COVID-19 control decision-making.

Selection and eligibility criteria

‘Decisions’ are defined as any protocol, guideline, recommendation, rule/requirement, regulation or law which relates to each of the selected COVID-19 interventions within a specified Latin American country. Decisions included are those made by government-level decision-making authorities such as the ministry of health (MoH) and published between December 2019 and 31 March 2021. Documents published in English, French, Spanish and Portuguese were included. Press statements, media briefings, and social media posts were excluded, as well as regional/sub-national decisions. Where multiple documents were found relating to the same intervention (including decision extensions) within one country, only documents reporting a change in the decision were included. ‘Decision changes’ are defined as documents which report a different decision from the previous, from the same decision-maker (eg. MoH).

Search strategy

The full search strategy including search terms is provided in Appendix 4. A systematic document review of both published and grey literature was conducted. First, the electronic databases included in Phase One were searched using the search terms given in Phase One and also included the general terms, “decision”, “policy”, “guideline”,” control”,” measure”,” restriction”, “recommendation”, “protocol”, “law”. Second, region-specific evidence-based policy websites such as IRIS [iris.paho.org] and BRISA [bvsalud.org]2 were searched.Third, websites for individual country ministries of health or government health authorities were searched, including country-specific coronavirus response websites. Lastly, intervention technical leads in the PAHO COVID-19 Incident Management Team were contacted to identify additional documents through PAHO country offices. Documents published in English, Spanish, Portuguese and French were included.

Data extraction and synthesis

Data was extracted onto a pre-designed Excel spreadsheet, exemplified in Appendix 5. Information extracted included: type of document (guideline, recommendation, law); source (ministry of health, presidency); date published; and a link to the full text. A qualitative synthesis of the document content was undertaken. The content of the document was screened for information relevant to the research question and relevant sections read in full. The main content of the document was categorised as either (i) recommending/advising/mandating/introducing an intervention, or (ii) recommending/advising/mandating against an intervention. Where documents contained decisions for more than one intervention (eg. more than one therapeutic), each decision was extracted separately. Within categories, there was further sub-categorisation where decisions applied only to certain groups or settings. A second review of 25% of the documents was performed independently by LR (co-author). It was deemed justifiable that a review of 25% of documents would sufficiently mitigate the risk of information bias. Data was synthesised by calculating monthly frequencies and cumulative frequencies of decisions by category and sub-category, between December 2019-March 2021.

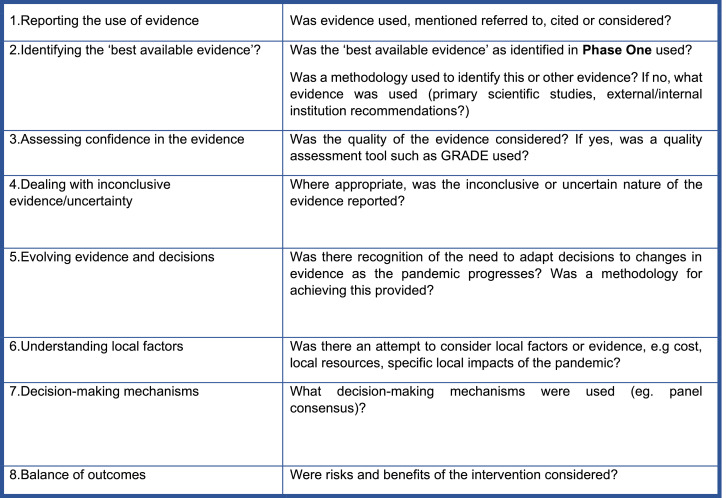

Phase Three: how did the best available evidence inform decision-making?

Phase Three consists of a ‘framework analysis’ of the use of the BAE identified in Phase One to inform the decisions identified in Phase Two. ‘Framework analysis’ is used to describe the application of an adapted framework in qualitative document content analysis. Currently, there is no existing evidence-to-decision tool specific to the emergency setting that has been used across intervention types. An adapted framework (Figure 2) was developed for this study based on the SUPPORT tools for evidence-informed policymaking (STP) and the GRADE Evidence-to-Decision (EtD) framework.13,34 The STP offers a practical process for supporting evidence-use specifically for policymakers deciding on interventions at a population level. The GRADE EtD, although it has been modified for use in various types of interventions, is primarily applied to clinical decision-making, both at the individual and population levels. This adapted framework was developed in discussion with evidence-informed policymaking experts at PAHO. The aim of the framework is to provide a tool to assess the use of evidence in decision-making across intervention types in an emergency setting. The framework is therefore adapted to specifically assess how uncertain and evolving evidence is used (criterion 3-5). The framework was piloted using a sub-set of the identified decision documents and adjustments were made. Document contents were screened for whether they fulfilled (yes) or did not fulfil (no/unclear) each criterion and frequencies were calculated.

Figure 2.

An Adapted Framework for assessing the use of evidence in decision-making in the pandemic setting.

Results

Phase one

Included studies

47 LSRs were identified on the L.OVE platform, all of which report evidence for therapeutics.29 One LSR for community mask use was identified at the eligibility stage, but none for diagnostic testing as a requirement for travel were identified. Further selection and eligibility criteria were applied as per the PRISMA flow diagram in Appendix 6. In total, 6 LSRs and 11 systematic reviews were included.32,35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59

Study characteristics

Appendix 7 includes three tables with full study characteristics. Of the 6 LSRs included, 5 were updated at least once. Five LSRs reported evidence for HCQ/CQ, 3 for corticosteroids, 2 for ivermectin, and 1 for community mask use. Seven SRs on community mask use and 4 on testing as a travel requirement were included.

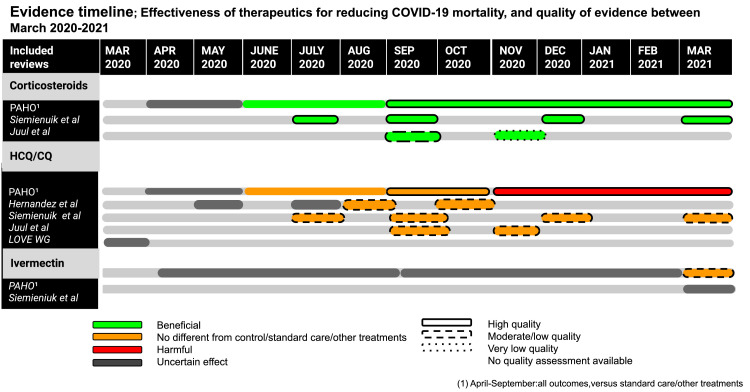

Evidence synthesis

Figure 3 shows an evidence timeline summarising the BAE for the effectiveness of each therapeutic for reducing COVID-19 mortality as well as evidence quality, between March 2020-March 2021 (March 2020 is the earliest LSR date of publication). Only corticosteroids were shown to have a beneficial effect at reducing mortality across all included studies, with evidence quality ranging from very low to high. Only HCQ/CQ was shown to have a harmful effect with high quality evidence in one LSR. All other LSRs report no difference between HCQ and controls/standard care/other treatments with either moderate/low or high quality. There was uncertain evidence for ivermectin until March 2021 where high risk of bias evidence shows no difference between its use and standard care/other treatments.

Figure 3.

Evidence timeline: therapeutics.

Appendix 8 shows an evidence timeline summarising the BAE for the effectiveness of wearing facemasks in the community setting for various COVID-19 infection outcomes. Facemask use in the community setting was found to be beneficial for a range of outcomes in all of the included studies, although with only very low or moderate/low-quality evidence. Only three of the reviews include direct evidence of facemask use with COVID-19 infection specifically, and only one of these includes only community settings.

Appendix 9 shows an evidence timeline summarising the BAE for the effectiveness of testing as a travel requirement. Only one of the included reviews includes studies which provide evidence on the use of PCR testing as a screening measure, reporting a beneficial effect (various outcomes) with very-low quality evidence for overall entry/exit screening measures.88 Three out of four studies report a beneficial effect of combined entry/exit screening measures on various infection control outcomes, with uncertain to moderate quality. No review included direct evidence on the use of PCR or antigen testing prior to or after travel.

Phase two

Included ‘decision’ documents

107 country-level documents from 21 countries (countries listed in Appendix 3a) were included for analysis (therapeutics n = 60, community mask use n = 25, testing as a travel requirement n = 21). All documents across intervention types are produced by government bodies such as the MoH, executive presidency or national congress, either solely or in partnership with national-level health partners such as medical societies or national health institutes. Appendix 3b details the number of decision documents by type.

Document review

Therapeutics

Corticosteroids. Forty-nine documents from 16 countries published between February 2020-February 2021 consider the use of corticosteroids for COVID-19 treatment. Thirty documents recommend the use of corticosteroids whilst 19 recommend against its use. Of these, 11 recommend its use for patients requiring oxygen therapy and 19 recommend its use according to disease severity or evidence of complications such as respiratory distress or inflammation.

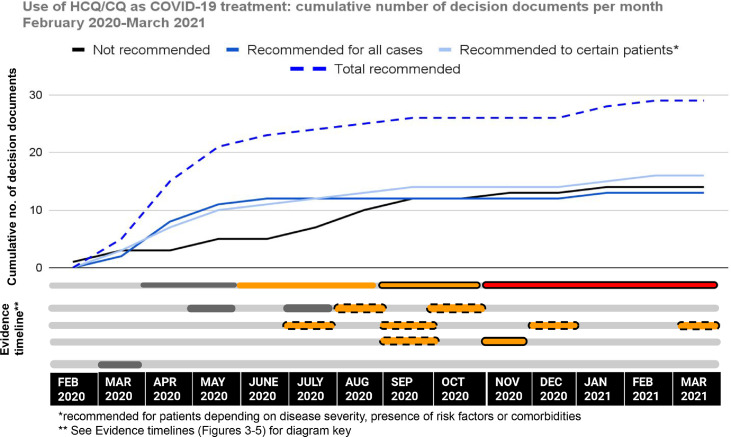

Hydroxychloroquine/Chloroquine. Forty-three documents from 15 countries published between February 2020-February 2021 consider the use of HCQ/CQ for COVID-19 treatment. Twenty-nine documents recommend the use of HCQ/CQ whilst 14 recommend against its use. Of those who recommend its use, 16 suggest its use only in certain cases according to disease severity, whereas 13 suggest its use in all suspected or confirmed patients.

Ivermectin. Nineteen documents from 12 countries published between April 2020-February 2021 consider the use of ivermectin in COVID-19 treatment. Nine documents recommend the use of ivermectin as a treatment, whilst 10 recommend against its use.

Face mask use in the community setting

Twenty-five documents from 17 countries published between March-December 2020 consider the use of facemasks in the community setting. All documents recommend the use of masks to varying extents. Nine documents recommend mask use in all areas outside the home, 7 in all public places, 6 in some public places such as indoor workplaces and 3 documents contain general recommendations for mask use in the non-specified community setting.

Diagnostic testing as a requirement for travel

Twenty-one documents from 16 countries published between June 2020 and February 2021 consider the use of diagnostic testing as a requirement for incoming international travellers. The majority recommend PCR tests only (n = 15) while 5 include the use of antigen testing and 1 includes the use of rapid antibody testing. There is a range between 24 hours and 10 days for the pre-travel testing period, the majority requiring 72 hours (n = 12). Two documents recommended testing on arrival, and 1 recommends random passenger antigen testing. Only one document recommends against the use of testing as a travel requirement.

Evidence-decision timelines

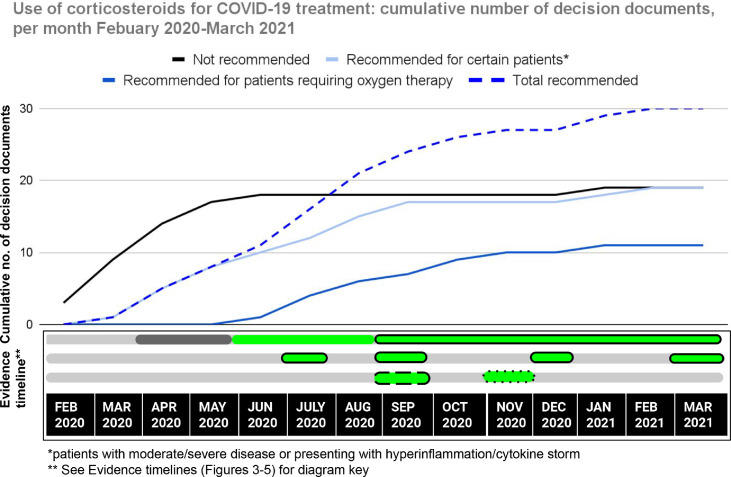

The cumulative number of country-level decision documents identified per month were plotted across the period between February-March 2021. The cumulative number of decision documents indicates the total number of decisions (including updates) made across the region per month. Appendix 12 shows the non-cumulative number of decision documents per month over the same time period.

Figure 4 shows an overall increasing trend in the number of decision documents which both recommend and do not recommend corticosteroid use, the latter stabilising by June 2020. After June 2020 there is a sharp and sustained rise in the total number of documents recommending the use of corticosteroids, particularly for patients requiring oxygen therapy. A majority of decision documents (55%, n = 27) were produced at a time when the BAE was uncertain of the effect of corticosteroid use of which 16 (59%) recommended its use.

Figure 4.

Evidence-to-decision timeline: corticosteroid use.

Figure 5 shows the evidence-decision timeline for the use of HCQ/CQ as a treatment for COVID-19. There is an initial sharp rise in the total number of documents recommending HCQ/CQ use between February and May 2020. The number of documents not recommending HCQ/CQ rises steadily across the study period, rising more steeply after June 2020. A majority of documents (63%, n = 27) were published at a time when BAE was uncertain of the effect of HCQ/CQ, of which 16 (59%) recommended its use.

Figure 5.

Evidence-to-decision timeline: HCQ/CQ use.

Figure 6 shows the evidence-decision timeline for the use of ivermectin in COVID-19 treatment. The number of documents recommending ivermectin is higher than those recommending against its use from April 2020 until January 2021, until a total of 10 documents (53%) recommend against its use by February 2021 and 9 (47%) for its use. All documents were published at a time when the BAE was uncertain as to the effect of ivermectin as a treatment for reducing mortality.

Figure 6.

Evidence-to-decision timeline: ivermectin use.

Appendix 10 shows the evidence-decision timeline for the use of face masks in the community setting. The total number of decision documents recommending face mask use in any community setting rises steeply initially from March to July 2020, then more steadily until February 2021. 60% (n = 15) of total documents were published at a time either before or after the availability of one SR of uncertain quality showing indirect evidence of benefit.

Appendix 11 shows the evidence-decision timeline for the use of testing as a travel requirement for incoming international travellers. The total number of decision documents recommending the use of testing rises consistently from May 2020 to March 2021. All were published at a time when evidence was indirect and of unclear or low/very low quality.

Phase 3

Framework analysis

The results of the framework analysis for each intervention type are given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Adapted framework criteria results.

|

![]()

For therapeutics decision documents, all eight framework criteria are fulfilled, with only three out of eight reaching a fulfilment rate of >50% (criteria 1,4 and 5). Whilst a majority report the use of evidence, criteria 2 shows that a minority is BAE (8%) and a majority (54%) of documents cite primary scientific studies providing direct or indirect evidence. Whilst a majority fulfil criteria 5, only 4 of these (10%) provide a methodology for tracking changes in evidence and incorporating them into decision-making, in all cases citing the ‘living review/guideline’ method. Importantly, whilst a minority of documents consider evidence quality (27%), with only 37.5% using a standardised quality assessment tool, the GRADE methodology was used by all six documents. Further, of the 21 documents (35%) reporting the use of decision-making mechanisms, 14 (67%) are expert recommendations and 7 are panel consensuses (34%).

In contrast, seven out of eight framework criteria for facemask use in the community setting and four out of eight for diagnostic testing as a requirement for travel are reported, neither of which has main criteria reaching >50% fulfilment. Seven out of eight criteria are reported to a higher frequency among therapeutics decision documents, with only the inclusion of local evidence/contextual factors such as the risk of importing COVID-19 variants, the lack of vaccines, and the overall risk of importing/exporting cases from high-transmission areas, reported more frequently for travel testing (17% vs 29%). Therapeutics documents mentioned factors such as cost and resource capacities, existing clinical knowledge of the specific therapeutic and the ethics of using a therapeutic with uncertain evidence of effect which was noted in one document. Further, whilst therapeutics documents report the use of scientific evidence to a greater extent than other measures, both external and internal institutional guidance (eg. WHO, MoH and internal health agencies) are reported most frequently among travel testing documents. Similarly, among both non-therapeutic measures, external and internal institutional guidance is used to a greater extent than scientific evidence.

Discussion

Results of Phase One demonstrate that the BAE for COVID-19 interventions continues to evolve, with more direct, higher quality and more frequently updated evidence for the effectiveness of therapeutics than for other measures. Phase Two shows that not only have the majority of decisions across intervention types been made in the context of uncertain or low-quality evidence, but these decisions show variation in both content and timing of decision outcomes across intervention types.

Further, there is more heterogeneity in decision outcomes concerning therapeutic interventions than other measures which are implemented more consistently across the region, although with variation in decision scope. Phase Three shows that key criteria of how evidence was used within decision-making (as defined by the proposed adapted framework criteria) are fulfilled more consistently among therapeutics decision-making documents than for other measures, although not entirely systematically across the region.

A vast majority of decision documents for therapeutic interventions reported the use of evidence (92%, n = 55), with most using evidence from primary scientific studies (54%, n = 27) and a minority using the best available evidence, as identified in Phase One (8%, n = 5). This compares with a minority of decision documents for non-pharmaceutical interventions reporting the use of evidence (28%, n = 7 for facemask use in the community setting; 29%, n = 7 for diagnostic testing as a requirement for travel), with only one document among both types of interventions reporting the use of scientific evidence for intervention effectiveness.

To the author's knowledge, this study is the first to examine the use of evidence in COVID-19 decision-making for both clinical management and public health policy decisions in the Latin America region. Numerous policy tracking initiatives have emerged since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic which tracks government policy response.5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 However, none of these include clinical management, and only one assesses the use of evidence in decision-making by evaluating an undefined ‘evidence-based justification’ and without the use of a formalised framework methodology as presented in this work.6

Implications for understanding clinical decision-making in the context of COVID-19

In the early period of the pandemic, there was heterogeneity in the decisions made by governments across the Latin American region to recommend the use of therapeutics, although to a lesser extent with corticosteroids which are recommended more consistently over time. This trend is not exclusive to LAC. Prats-Uribe et al show that HCQ/CQ particularly was used with great variability in the US, South Korea, Spain and China, whilst corticosteroid use increased sharply across all countries after June 2020.60 This coincides with the pre-print publication of preliminary results from the RECOVERY trial showing a benefit of corticosteroids for reducing 28-day mortality when used in patients requiring oxygen or ventilation; suggesting that decisions vary to a greater degree where evidence is uncertain, and this variation is diminished once more robust evidence emerges.61 Martinez-Sanz et al show that the heterogeneity in clinical decision-making seen during the earliest weeks of the COVID-19 pandemic tended to worsen with increasing clinical severity. Factors such as confidence in COVID-19 publications and their quality affect the aggressiveness of treatment approach, and regional trends were also noted with Latin America less likely to treat with aggressive therapies compared to other world regions.62

The results of this study show a substantial proportion of clinical management decisions are made without transparent reporting of important aspects of a decision-making process. This questions the quality and reliability of these decisions. Similarly, Stamm et al assessed the quality of clinical guidelines related to the COVID-19 situation using the AGREE framework, concluding that most do not fulfil basic standards of guideline development, largely due to the poor application of established methodologies such as systematic reviews and consensus processes.63 In a similar study, Dagens et al concluded that the AGREE framework is unfit for the emergent evidence context, hence the advantage of the framework presented in this study which emphasizes how evolving evidence is used.64 Whilst there are notable examples in the region of the transparent application of methodology-based evidence-to-decision frameworks for decision-making (e.g. Chile),65 there is a need for this to become more systematic across the region.

Implications for understanding decision-making in the context of uncertain and evolving evidence

Phase Two demonstrates a majority of decisions made across intervention types occurred when BAE was uncertain, or only low-quality, indirect evidence was available. Salajan et al confirmed that evidence uncertainty and ambiguity puts a major strain on decision-making, despite an expectation that public health policy and practice in an emergency be ‘grounded in the best scientific knowledge’.20 Yoo et al investigated country variations in COVID-19 control policy and demonstrated that factors such as increasing case numbers or death rates, may determine policy response, suggesting that decisions are dependent on the need for a policy rather than the ‘steady culmination of evidence’.67 Relying on a ‘pipeline model’ of knowledge transition whereby research emerges as an input to a linear process which underpins output decisions, risks that policy decisions in an evidence-scarce environment are dependent on a low flow of evidence and subsequent policy stagnation.67 Decision-makers in the emergency setting may be more pragmatically guided by Lancaster et al’s ‘evidence enough’ concept, arguing that where immediate and at-scale decisions are required, prioritising ‘what can be done’ can lead to an adaptive and flexible approach to decision-making.15 Flexibility in decision-making is crucial where evidence is actively accumulating, but transparent communication of knowledge gaps and necessary trade-offs must follow.68

Understanding evidence-use differences between clinical management and public health policy decisions

This study shows that evidence-use is more established, or reported to a greater extent, among therapeutics decisions than for other measures. This could be the result of the evidence gap for non-therapeutic measures identified in Phase One and also acknowledged by the 2019 WHO Global Influenza Programme review, showing limited evidence of mostly low-quality for infection prevention measures, with evidence consisting mainly of observational or modelling studies rather than clinical trials.69 However, clinical management is more traditionally based on a hierarchy of scientific evidence, whereas public health decisions require a more nuanced approach than following only empirical data involving a broader range of evidence from various disciplines (eg. behaviour science, human rights, economics).70,71 Cairney et al similarly argue that policy decisions are a product of discussions grounded in competing values and preferences, rather than only on scientific evidence.72 Aldort et al argue that pandemic influenza preparedness also relied heavily on expert opinion.73 This may explain why decision documents for facemask and travel testing measures report the use of both other evidence/local factors (16%, 29% respectively) and external recommendations/policy documents (43% and 57% respectively) more frequently than scientific evidence. This finding might also be explained by a possible tendency for countries to follow the recommendations of other countries, however, further research is required to conclude this. Nevertheless, as population-level measures often affect millions, the lack of a widely reported, transparent decision-making process for these interventions is concerning.

Study limitations

Firstly, assuming that reviews are best-placed for defining an evidence base for decision-making, particularly in the pandemic setting, may be flawed. This study is echoed by several papers highlighting that a robust systematic review is a lengthy process, thus unsuitable to the emergency context; highlighting complexity and uncertainty rather than ‘whether it works’, a more prudent question for time-pressured decision-makers.74,75 Whilst the use of LSRs in this study aims to overcome this limitation, it could mean high-quality SRs were excluded. Secondly, the reviews that were included in this study were not subjected to a risk of bias assessment or independent data extraction by more than one study author, which may affect internal validity. Thirdly, by only including reviews published after December 2019 as BAE, this excluded other types of best evidence that decision-makers may have used during their decision-making process. This is particularly true for evidence for the intervention of face mask use in the community for the prevention of non-COVID-19 respiratory infections. Fourthly, a relatively limited number of decision documents are included, and many are arguably a consequence of the decision-making process rather than proof of it. Particularly for non-therapeutic interventions, documents are largely legal documents (ordinances, decrees, etc.) which outline the scope and conditions of the decision taken, rather than the process which led to that decision. Further, this study arguably places too much weight on capturing the outcome of the decision-making process, rather than unpicking the procedural aspects of how evidence itself was considered, weighted or challenged, and the specific barriers to its use. Also, the evidence-decision timelines provide only visual representation, and therefore are limited in the extent to which they can provide an analysis on how decision outcomes followed evidence generation over time. This limitation also holds true for the framework analysis in Phase Three which assessed evidence use overall without providing time-dependent analysis.This mean that this paper is unable to conclude on a correlation between evidence generation and decision outcome and is limited to concluding only on whether evidence use is reported. Further, by excluding alternative information sources (eg. social media, press announcements, etc), some decision outcomes may be missed. Many countries in the region prioritised communicating decisions rapidly and widely, meaning the production of more formal documentation of the decision-making process may have been understandably side-lined or deprioritised, and there are several examples where decisions have been communicated without corresponding decision documents.76,77 This study also overlooks the importance of sub-national decision-making, particularly for federalised nations, which is important if it is conceivable that evidence used in decision-making differs greatly between sub-nations. Finally, given the rapid pace of the pandemic, by the time of writing there has been promising progress by certain countries in the region that have updated decisions and reported decision-making processes based on evidence, that has not been captured in this study.32,78

Conclusions and key recommendation

Decision-making in the context of uncertain, evolving evidence introduces unique challenges, and the extent to which evidence use in decision-making for COVID-19 interventions is reported in the LAC region is limited. In an emergency setting, decisions across intervention types occur in the context of uncertain evidence, and an approach to navigating this evidence scarcity is crucial. Whilst clinical management decisions appear to follow a process for identifying, assessing and considering evidence in decision-making to a greater extent, this process is more limited for population-level interventions. Institutionalising a transparent approach to evidence use in decision-making based on existing and emerging methodologies informed by ethical principles can facilitate rapid response and should urgently focus on including population-level measures.

Contributors

V.S.: conceptualised and developed the methodology for this paper and undertook data collection, analysis, interpretation and writing of the manuscript. L.R.: assisted in conceptualising and developing the methodology for this paper, as well as performing data analysis and interpretation. He was also involved in reviewing and editing the manuscript. L.G., J.M., J.T. and S.A. assisted in conceptualising and developing the methodology for this paper and were involved in the interpretation, and revision of the manuscript.

Ethics

This research was submitted for ethical approval to the Pan American Health Organization Ethics Review Committee (PAHOERC).

Declaration of interests

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist. Authors hold sole responsibility for the views expressed in the manuscript, which may not necessarily reflect the opinion or policy of the Pan American Health Organization.

Funding

No funding was sourced for this work.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.lana.2022.100322.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Oliver K, Innvar S, Lorenc T, Woodman J, Thomas J. A systematic review of barriers to and facilitators of the use of evidence by policymakers. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14(1):2. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-14-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control . ECDC; Stockholm: 2019. The use of evidence in decision-making during public health emergencies.https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/use-of-evidence-in-decision-making-during-public-health-emergencies_0.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abbott R, Bethel A, Rogers M, et al. Characteristics, quality and volume of the first 5 months of the COVID-19 evidence synthesis infodemic: a meta-research study. BMJ Evid-Based Med. 2022;27:169–177. doi: 10.1136/bmjebm-2021-111710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.ICTRP Search Portal, 2021. Available from: https://www.who.int/clinical-trials-registry-platform/the-ictrp-search-portal

- 5.Hale T., Webster S., Petherick A., Phillips T., Kira B. 2020. Oxford COVID_19 Government Response Tracker, Blavatnik School of Government.https://covidtracker.bsg.ox.ac.uk Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 6.The International Network for Global Science Advice (INGSA) 2020. COVID-19 Evidence to Policy Tracker.https://www.ingsa.org/covid/policymaking-tracker Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheng C, Barceló J, Hartnett AS, Kubinec R, Messerschmidt L. COVID-19 Government response event dataset (CoronaNet v.1.0) Nat Hum Behav. 2020;4(7):756–768. doi: 10.1038/s41562-020-0909-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.OECD. Tackling Coronavirus (COVID-19): contributing to a global effort, 2021. Available from: https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/country-policy-tracker/

- 9.ACAPS . ACAPS; 2020. COVID-19 Government Measures Dataset.https://www.acaps.org/covid-19-government-measures-dataset [cited 2021 May 29]. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peña SMP, Cuadrado C, Rivera-Aguirre AE, et al. 2020. PoliMap: A Taxonomy Proposal for Mapping and Understanding the Global Policy Response to COVID-19. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Macintyre S, Chalmers I, Horton R, Smith R. Using evidence to inform health policy: case study. BMJ. 2001;322(7280):222–225. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7280.222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brownson RC, Chriqui JF, Stamatakis KA. Understanding evidence-based public health policy. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(9):1576–1583. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.156224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oxman AD, Lavis JN, Lewin S, Fretheim A. SUPPORT Tools for evidence-informed health Policymaking (STP) 1: what is evidence-informed policymaking? Health Res Policy Syst. 2009;7(1):S1. doi: 10.1186/1478-4505-7-S1-S1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yang K. What can COVID-19 tell us about evidence-based management? Am Rev Public Admin. 2020;50(6–7):706–712. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lancaster K, Rhodes T, Rosengarten M. Making evidence and policy in public health emergencies: Lessons from COVID-19 for adaptive evidence-making and intervention. Evid Policy. 2020;16(3):477–490. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Choi BCK, Pang T, Lin V, et al. Can scientists and policy makers work together? J Epidemiol Commun Health. 2005;59(8):632–637. doi: 10.1136/jech.2004.031765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Head BW. Reconsidering evidence-based policy: key issues and challenges. Policy Soc. 2010;29(2):77–94. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Campbell DM, Redman S, Jorm L, Cooke M, Zwi AB, Rychetnik L. Increasing the use of evidence in health policy: practice and views of policy makers and researchers. Austr New Zeal Health Policy. 2009;6(1):21. doi: 10.1186/1743-8462-6-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harvey G, Kitson A. Translating evidence into healthcare policy and practice: single versus multi-faceted implementation strategies – is there a simple answer to a complex question? Int J Health Policy Manag. 2015;4(3):123–126. doi: 10.15171/ijhpm.2015.54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Salajan A-L, Tsolova S, Ciotti M, Suk J. To what extent does evidence support decision making during infectious disease outbreaks? A scoping literature review. Evid Policy. 2020;16 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boadle A. WHO says the Americas are new COVID-19 epicenter as deaths surge in Latin America. Reuters. 2020 https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-latam-idUKKBN2322G6 [cited 2021 May 30]; Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pan American Health Organisation (PAHO). Latin America and the Caribbean Surpass 1 Million COVID Deaths PAHO/WHO | Pan American Health Organization. [cited 2021 May 31]. Available from: https://www.paho.org/en/news/21-5-2021-latin-america-and-caribbean-surpass-1-million-covid-deaths

- 23.WHO SPAR . 2021. Strategic Partnership for Health Security and Emergency Preparedness (SPH) Portal.https://extranet.who.int/sph/spar?region=203 [cited 2021 Jun 5]. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 24.OECD. Covid-19 en América Latina y el Caribe: Panorama de las Respuestas de los Gobiernos a la Crisis. OECD, 2020. Available from: https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/covid-19-en-america-latina-y-el-caribe-panorama-de-las-respuestas-de-los-gobiernos-a-la-crisis-7d9f7a2b/

- 25.L. Horowitz and C. Zissis. Timeline: Tracking Latin America's Road to Vaccination. AS/COA, 2020. Available from: https://www.as-coa.org/articles/timeline-tracking-latin-americas-road-vaccination

- 26.Aromataris E, Fernandez R, Godfrey CM, Holly C, Khalil H, Tungpunkom P. Summarizing systematic reviews: methodological development, conduct and reporting of an umbrella review approach. JBI Evid Implement. 2015;13(3):132–140. doi: 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cochrane Collaboration . 2019. Guidance for the Production and Publication of Cochrane Living Systematic Reviews: Cochrane Reviews in Living Mode.https://community.cochrane.org/sites/default/files/uploads/inline-files/Transform/201912_LSR_Revised_Guidance.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barker J. Keeping up with COVID-19 – using living systematic reviews to close the evidence gap. F1000 Blogs. 2020 https://blog.f1000.com/2020/10/19/keeping-up-with-covid-19-using-living-systematic-reviews-to-close-the-evidence-gap/ [cited 2021 May 8]. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 29.Epistemonikos Foundation. Living Overview of the Evidence (LOVE), 2021. Available from: https://app.iloveevidence.com/loves/5e6fdb9669c00e4ac072701d?question_domain=undefined&population=5e7fce7e3d05156b5f5e032a§ion=methods&classification=all

- 30.Rada G, Pérez D, Araya-Quintanilla F, et al. Epistemonikos: a comprehensive database of systematic reviews for health decision-making. BMC Med Res Method. 2020;20(1):286. doi: 10.1186/s12874-020-01157-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.BMJ Best Practice. What is GRADE? [cited 2021 May 15]. Available from:https://bestpractice.bmj.com/info/us/toolkit/learn-ebm/what-is-grade/

- 32.Pan American Health Organisation . 2021. Ongoing Living Update of COVID-19 Therapeutic Options Summary of Evidence.https://iris.paho.org/handle/10665.2/52719 Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 33.BMJ Drug treatments for covid-19: living systematic review and network meta-analysis. BMJ. 2020;370:m2980. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m2980. https://www.bmj.com/content/370/bmj.m2980 [cited 2021 May 15]. Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alonso-Coello P, Schünemann HJ, Moberg J, et al. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 1: Introduction. BMJ. 2016;353:i2016. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Siemieniuk RA, Bartoszko JJ, Ge L, et al. Drug treatments for Covid-19: living systematic review and network meta-analysis. BMJ. 2020;370:m2980. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m2980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hernandez AV, Roman YM, Pasupuleti V, Barboza JJ, White CM. Hydroxychloroquine or chloroquine for treatment or prophylaxis of COVID-19: a living systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173(4):287–296. doi: 10.7326/M20-2496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hernandez AV, Roman YM, Pasupuleti V, Barboza JJ, White CM. Hydroxychloroquine or chloroquine for treatment or prophylaxis of COVID-19: a living systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173(4):287–296. doi: 10.7326/M20-2496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hernandez AV, Roman YM, Pasupuleti V, Barboza JJ, White CM. Update Alert 2: hydroxychloroquine or chloroquine for the treatment or prophylaxis of COVID-19. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173(7):W128–W129. doi: 10.7326/L20-1054. Epub 2020 Aug 27. PMID: 32853033; PMCID: PMC7472719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hernandez AV, Roman YM, Pasupuleti V, Barboza JJ, White CM. Update Alert 3: Hydroxychloroquine or Chloroquine for the Treatment or Prophylaxis of COVID-19. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173(11):W156–W157. doi: 10.7326/L20-1257. Epub 2020 Oct 21. PMID: 33085507; PMCID: PMC7596739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Juul S, Nielsen EE, Feinberg J, et al. Interventions for treatment of COVID-19: A living systematic review with meta-analyses and trial sequential analyses (The LIVING Project) PLoS Med. 2020;17(9) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Juul S, Nielsen EE, Feinberg J, et al. Interventions for treatment of COVID-19: Second edition of a living systematic review with meta-analyses and trial sequential analyses (The LIVING Project) PLoS One. 2021;16(3) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0248132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Epistemonikos . Epistemonikos Foundation; 2020. Systematic review-Preliminary Report; Antimalarials for the Treatment of COVID-19.https://www.epistemonikos.cl/2020/03/27/systematic-review-preliminary-report-antimalarials-for-the-treatment-of-covid-19/ [cited 2021 Jun 18]. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 43.Xiao J, Shiu EYC, Gao H, et al. Nonpharmaceutical measures for pandemic influenza in nonhealthcare settings personal protective and environmental measures. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26(5):967–975. doi: 10.3201/eid2605.190994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liang M, Gao L, Cheng C, et al. Efficacy of face mask in preventing respiratory virus transmission: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2020;36 doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2020.101751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chou R, Dana T, Jungbauer R, Weeks C, McDonagh MS. Masks for prevention of respiratory virus infections, including SARS-CoV-2, in health care and community settings: a living rapid review. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173(7):542–555. doi: 10.7326/M20-3213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chou R, Dana T, Jungbauer R, Weeks C, McDonagh MS. Masks for prevention of respiratory virus infections, including SARS-CoV-2, in health care and community settings : a living rapid review. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173(7):542–555. doi: 10.7326/M20-3213. Epub 2020 Jun 24. Update in: Ann Intern Med. 2021 Feb;174(2):W24. PMID: 32579379; PMCID: PMC7322812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chou R, Dana T, Jungbauer R, Weeks C, McDonagh MS. Update Alert 2: masks for prevention of respiratory virus infections, including SARS-CoV-2, in health care and community settings. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173(7) doi: 10.7326/l20-1067. PMID: 32853032; PMCID: PMC7472717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chou R, Dana T, Jungbauer R, Weeks C. Update Alert 3: masks for prevention of respiratory virus infections, including SARS-CoV-2, in health care and community settings. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173(12) doi: 10.7326/L20-1292. Epub 2020 Oct 27. PMID: 33105095; PMCID: PMC7596736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chou R, Dana T, Jungbauer R, Weeks C. Update Alert 4: masks for prevention of respiratory virus infections, including SARS-CoV-2, in health care and community settings. Ann Intern Med. 2021;174(2) doi: 10.7326/L20-1429. Epub 2020 Dec 29. PMID: 33370171; PMCID: PMC7774035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chou R, Dana T, Jungbauer R, Weeks C. Update Alert 5: masks for prevention of respiratory virus infections, including SARS-CoV-2, in health care and community settings. Ann Intern Med. 2021;174(4) doi: 10.7326/L21-0116. Epub 2021 Mar 9. PMID: 33683928; PMCID: PMC7974711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chu DK, Akl EA, Duda S, et al. Physical distancing, face masks, and eye protection to prevent person-to-person transmission of SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet North Am Ed. 2020;395(10242):1973–1987. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31142-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Coclite D, Napoletano A, Gianola S, et al. Face mask use in the community for reducing the spread of COVID-19: a systematic review. Front Med. 2021;7 doi: 10.3389/fmed.2020.594269. https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85099940156&doi=10.3389%2ffmed.2020.594269&partnerID=40&md5= a37587eeeee7eded979f2469f0c7826b Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jefferson T, Del Mar CB, Dooley L, et al. Physical interventions to interrupt or reduce the spread of respiratory viruses. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;11(11) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006207.pub5. PMID: 33215698; PMCID: PMC8094623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Brainard J, Jones NR, Lake IR, Hooper L, Hunter PR. Community use of face masks and similar barriers to prevent respiratory illness such as COVID-19: a rapid scoping review. Eurosurveillance. 2020;25(49) doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.49.2000725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kim MS, Seong D, Li H, et al. Comparative efficacy of N95, surgical, medical, and non-medical facemasks in protection of respiratory virus infection: a living systematic review and network meta-analysis. Rev Med Virol. 2022 doi: 10.1002/rmv.2336. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 35218279; PMCID: PMC9111143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Viswanathan M, Kahwati L, Jahn B, et al. Universal screening for SARS-CoV-2 infection: a rapid review. Cochrane Database System Rev. 2020;9(9) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD013718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Burns J, Movsisyan A, Stratil JM, et al. Travel-related control measures to contain the COVID-19 pandemic: a rapid review. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;10 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD013717. Update in: Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021 Mar 25;3:CD013717. PMID: 33502002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Grépin KA, Ho T, Liu Z, et al. Evidence of the effectiveness of travel-related measures during the early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic: a rapid systematic review. BMJ Global Health. 2021;6 doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-004537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chetty T, Daniels BB, Ngandu NK, Goga A. A rapid review of the effectiveness of screening practices at airports, land borders and ports to reduce the transmission of respiratory infectious diseases such as COVID-19. S Afr Med J. 2020;110(11):1105–1109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Prats-Uribe A, Sena AG, Lai LYH, et al. Use of repurposed and adjuvant drugs in hospital patients with covid-19: multinational network cohort study. BMJ. 2021;373:n1038. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n1038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Horby P, Lim WS, Emberson J, et al. Effect of dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 – preliminary report. medRxiv. 2020 2020.06.22.20137273. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Martínez-Sanz J, Pérez-Molina JA, Moreno S, Zamora J, Serrano-Villar S. Understanding clinical decision-making during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional worldwide survey. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;27 doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100539. https://www.thelancet.com/journals/eclinm/article/PIIS2589-5370(20)30283-2/abstract Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Dagens A, Sigfrid L, Cai E, et al. Scope, quality, and inclusivity of clinical guidelines produced early in the covid-19 pandemic: rapid review. BMJ. 2020;369 doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1936. Erratum in: BMJ. 2020 Jun 12;369:m2371. PMID: 32457027; PMCID: PMC7249097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Dagens A, Sigfrid L, Cai E, et al. Scope, quality, and inclusivity of clinical guidelines produced early in the covid-19 pandemic: rapid review. BMJ. 2020;369:m1936. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ministerio de Salud Chile. Clinical recommendations based on evidence; COVID-19, 2021 #CuidémonosEntreTodos. Available from: https://diprece.minsal.cl/temas-de-salud/temas-de-salud/guias-clinicas-no-ges/guias-clinicas-no-ges-enfermedades-transmisibles/covid-19/recomendaciones/.

- 66.Yoo JY, Dutra SVO, Fanfan D, et al. Comparative analysis of COVID-19 guidelines from six countries: a qualitative study on the US, China, South Korea, the UK, Brazil, and Haiti. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1853. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-09924-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Malterud K, Bjelland AK, Elvbakken KT. Evidence-based medicine – an appropriate tool for evidence-based health policy? A case study from Norway. Health Res Policy Syst. 2016;14(15) doi: 10.1186/s12961-016-0088-1. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4779248/ [cited 2021 May 27]. Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ford N, Thomas R, Grove J. Transparency: a central principle underpinning trustworthy guidelines. J Clin Epidemiol. 2022;142:246–248. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2021.11.025. Epub 2021 Nov 16. PMID: 34798288; PMCID: PMC8594247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.World Health Organisation (WHO) WHO. World Health Organization; 2019. WHO | Non-Pharmaceutical Public Health Measures for Mitigating the Risk and Impact of Epidemic and Pandemic Influenza.http://www.who.int/influenza/publications/public_health_measures/publication/en/ [cited 2021 May 30]. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bish A, Michie S. Demographic and attitudinal determinants of protective behaviours during a pandemic: a review. Br J Health Psychol. 2010;15(4):797–824. doi: 10.1348/135910710X485826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.de Campos-Rudinsky TC, Undurraga E. Public health decisions in the COVID-19 pandemic require more than ‘follow the science. J Med Ethics. 2021;47(5):296–299. doi: 10.1136/medethics-2020-107134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Cairney P, Oliver K. Evidence-based policymaking is not like evidence-based medicine, so how far should you go to bridge the divide between evidence and policy? Health Res Policy Syst. 2017;15(1):35. doi: 10.1186/s12961-017-0192-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Aledort JE, Lurie N, Wasserman J, Bozzette SA. Non-pharmaceutical public health interventions for pandemic influenza: an evaluation of the evidence base. BMC Public Health. 2007;7(1):208. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-7-208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Nature Evidence-based medicine: how COVID can drive positive change. Nature. 2021;593(7858):168. doi: 10.1038/d41586-021-01255-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Greenhalgh T, Malterud K. Systematic reviews for policymaking: muddling through. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(1):97–99. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ministry of Health and Social Protection Colombia . Press Bulletin No.289; 2020. Recommendation of Chloroquine, Hydroxychloroquine and lopinavir/Ritonavir to Treat COVID-19 Withdrawn.https://www.minsalud.gov.co/Paginas/Se-retira-recomendacion-de-cloroquina-hidroxicloroquina-y-lopinavir-ritonavir-para-tratar-covid-19.aspx [cited 2021 Jun 11]. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ministerio de Salud Costa Rica . 2020. Uso de Mascarilla se Recomienda en Transporte Público, Atención al Público y Reuniones.https://www.ministeriodesalud.go.cr/index.php/centro-de-prensa/noticias/741-noticias-2020/1660-uso-de-mascarilla-se-recomienda-en-transporte-publico-atencion-al-publico-y-reunione [cited 2021 Jun 11]. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ministry of Health Argentina . Argentina.gob.ar; 2021. Actualizaciones Basadas en Evidencia COVID-19.https://www.argentina.gob.ar/salud/conetec/actualizaciones [cited 2021 Jun 11]. Available from: [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.