PROMs collection is encouraged to involve patients in their health care

The patient is the most reliable reporter of their symptoms, function and health‐related quality of life, and can provide a holistic viewpoint of the benefits and risks of treatments or the severity of their conditions. Including the patient’s voice is critical for shared decision making and patient‐centred care. Patient‐reported outcomes (PROs) are defined as “any report of the status of a patient’s health condition that comes directly from the patient, without interpretation of the patient’s response by a clinician or anyone else”. 1 Patient‐reported outcome measures (PROMs) are validated tools or questionnaires used to collect PROs. PROMs can complement traditional methods of clinical assessment, such as medical history and physical examination. The use of systematically collected PROMs to inform the delivery of care has been researched for many years, 2 , 3 with patient and health service impacts including reduced symptom burden, improved quality of life and increased survival of patients with advanced cancer, 4 and reduced emergency department presentations in a broad population of patients with cancer. 5 As research suggests, the collection of PROMs in the clinical setting could better measure differences in the effects of health care interventions. 6 PROMs collection is encouraged in the 2020–25 National Health Reform Agreement to empower patients to be involved in their health care, improve care across the health system, and focus on outcomes that matter to patients. 7

This article outlines recommendations from the Health Services Research Association of Australia and New Zealand (HSRAANZ) for implementing PROMs to guide clinical care. It also describes the challenges that may arise and future research that may assist in the effective implementation of PROMs.

The recommendations presented in this article have been developed by members of the HSRAANZ PROMs Special Interest Group.

Recommendations

Clinician level

-

•

Clinicians are encouraged to use PROMs to detect and assess health issues that have not been routinely captured previously and take action to address areas of unmet patient needs.

-

•

Clinicians are encouraged to implement PROMs in health conditions where there are clear pathways of evidence‐based management to treat specific symptoms and aspects of functioning.

-

•

Clinicians should use PROMs that are validated, user‐friendly and written in a lay language and that comprise a limited number of items to increase uptake and avoid survey fatigue.

Health system level

-

•

Clinician knowledge and familiarity with PROs data are essential for effective implementation into clinical care. Health care institutions are encouraged to develop and invest in education and training for health care providers to facilitate clinical uptake of PROMs and their effective implementation into practice. This may also include information to support patients’ participation in PROMs programs.

-

•

Accurate interpretation of PROMs data in a timely manner is necessary to optimise patient–clinician engagement. Health systems are encouraged to invest in electronic data management to enable feedback of PROMs to clinicians and patients in a way that facilitates interpretation as a clear visual or graphical presentation. These can be presented as a longitudinal graph with trends over time and changes in symptom, functional and disease status.

-

•

Electronic capture of PROs data is feasible and beneficial compared with paper surveys. Electronic PROMs allow real‐time feedback of results, less missing data and reduced resources needed for data entry and management. Service providers are encouraged to incorporate electronic capture and storage of PROMs in online health records.

Health systems are encouraged to provide incentives to clinicians and practices (eg, funding through the National Health Reform Agreement) to implement these measures effectively. This will motivate clinicians to routinely incorporate their patients’ perspective into their busy schedules. They will be more likely to implement PROMs if there is a benefit to patient care and their clinical practice, by making care easier and more timely and reducing the administrative burden.

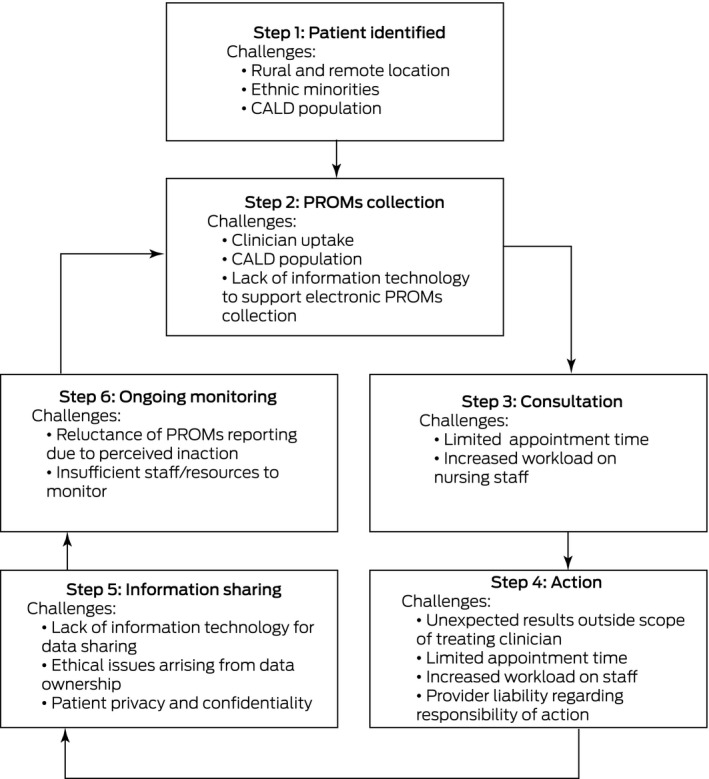

There are several challenges to consider when integrating PROMs into clinical care. As patients are recruited to PROMs collection, challenges can arise at different time points through the journey of their care (Box). It is important to note that while these exist, they are not insurmountable and can be overcome with further research on implementation in general practice and hospital clinics. Already, research into the integration of PROMs in clinical care in Australia has shown that implementation is feasible and effective. The New South Wales Agency for Clinical Innovation Patient Reported Measures program completed a pilot study 8 and demonstrated the feasibility of implementing PROMs in local health districts, community services and general practice. Principles to support the analysis and use of PROMs have been developed. 9

Box 1. Guide to the implementation and challenges of patient‐reported outcome measures (PROMs) in the clinical setting.

CALD = culturally and linguistically diverse population.

There is increased focus by health care systems to improve the value of care in terms of both value for investment and outcomes that patients value. Embedding patient‐reported measures into the clinical setting is a key component towards achieving this. Further research is underway to evaluate the applicability and benefits and harms of collecting PROMs in routine clinical care. 10 Future research should focus on investigating the feasibility of prompt feedback of patient‐reported data to clinicians and incorporating the results of patient‐reported measures into clinical practice.

With advances in technology and increased engagement by clinicians and health systems, the implementation of PROMs will be a routine part of health care provision in the future.

Competing interests

No relevant disclosures.

Provenance

Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Acknowledgements

Rachael Morton receives salary support from a University of Sydney Robinson Fellowship and a National Health and Medical Research Council Investigator Award (APP1194703). The funding source has no role in the planning, writing or publication of this work.

References

- 1. US Food and Drug Administration . Guidance for Industry: patient‐reported outcome measures: use in medical product development to support labeling claims; December 2009. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory‐information/search‐fda‐guidance‐documents/patient‐reported‐outcome‐measures‐use‐medical‐product‐development‐support‐labeling‐claims (viewed Apr 2019).

- 2. Thompson C, Sansoni J, Morris D, et al. Patient‐reported outcome measures: an environmental scan of the Australian healthcare sector. Sydney: Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care, 2016. https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/sites/default/files/migrated/PROMs‐Environmental‐Scan‐December‐2016.pdf (viewed May 2019). [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ishaque S, Karnon J, Chen G, et al. A systematic review of randomised controlled trials evaluating the use of patient‐reported outcome measures (PROMs). Qual Life Res 2019; 28: 567–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Basch E, Deal AM, Kris MG, et al. Symptom monitoring with patient‐reported outcomes during routine cancer treatment: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol 2016; 34: 557–565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Girgis A, Durcinoska I, Arnold A, et al. Web‐based Patient‐Reported Outcome Measures for Personalized Treatment and Care (PROMPT‐Care): multicenter pragmatic nonrandomized trial. J Med Internet Res 2020; 22: e19685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wagle NW. Implementing patient‐reported outcome measures. New Engl J Med Catalyst 2017; 12 Oct. http://catalyst.nejm.org/implementing‐proms‐patient‐reported‐outcome‐measures/ (viewed May 2019). [Google Scholar]

- 7. Department of Health . Addendum to the National Health Reform Agreement (NHRA) 2020–25. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2020. https://www.health.gov.au/initiatives‐and‐programs/2020‐25‐national‐health‐reform‐agreement‐nhra (viewed Mar 2021). [Google Scholar]

- 8. NSW Agency for Clinical Innovation . Patient Reported Measures: formative evaluation 2017. Sydney: ACI, 2018. https://aci.health.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0005/405446/Patient‐Reported‐Measures‐Program‐Formative‐Evaluation‐Report‐2017.pdf (viewed Jan 2021). [Google Scholar]

- 9. NSW Agency for Clinical Innovation . Analytic principles for patient‐reported outcome measures. Sydney: ACI, 2021. https://aci.health.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0007/633454/Analytic‐Principles‐for‐Patient‐Reported‐Outcome‐Measures.pdf (viewed Mar 2021). [Google Scholar]

- 10. Breidenbach C, Kowalski C, Wesselmann S, Sibert NT. Could existing infrastructure for using patient‐reported outcomes as quality measures also be used for individual care in patients with colorectal cancer? BMC Health Serv Res 2021; 21: 448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]