Abstract

Objectives

To describe and explain the outcomes of community dementia friendly initiatives (DFIs) for people with dementia and their caregivers to inform the development and tailoring of DFIs.

Methods

Literature searches on DFIs were performed through two systematic online database searches of PubMed, Embase, ASSIA, CINAHL and Google scholar. Papers were only included if they evaluated outcomes using empirical data from people with dementia or caregivers. Data collection and analysis were guided by the categorization in the DEM‐FACT taxonomy and RAMESES guidelines for realist reviews.

Results

Of 7154 records identified, 22 papers were included with qualitative, mixed method and quantitative study designs. The synthesis led to a description of programme theories addressing caring, stimulating and activating communities. Outcomes for people with dementia and caregivers included having contact with others, enjoyment and decrease of stress and, lastly, support. This synthesis also indicated how people with dementia participated in a specific role in DFIs, such as patient, team member or active citizen.

Conclusions

DFIs generate different outcomes for people with dementia and caregivers, depending on the kind of initiative and the specific role for people with dementia. These findings could be a catalyst for initiation and further development of DFIs in a dementia friendly community (DFC). This draws attention to the multiple aspects of DFCs and supports reflection on their essential principles.

Keywords: caregivers, dementia, dementia friendly communities, dementia friendly initiatives, outcomes, realist review, social participation

Key points

This is the first synthesis of the outcomes and mechanisms of dementia friendly initiatives (DFIs) using studies with empirical data from the perspective of people with dementia or caregivers.

DFIs generate different outcomes for both people with dementia and caregivers.

DFIs have different outcomes for people with dementia participating in different specific roles (i.e. patient, team member or active citizen).

DFI outcomes according to people with dementia and caregivers support both the practical development and research of how dementia friendly communities (DFCs) succeed in fulfilling their purpose.

1. INTRODUCTION

Around 50 million people have dementia worldwide. Due to changing demographics, it has been estimated that the prevalence is increasing by nearly 10 million annually, and the number of people with dementia is expected to exceed 150 million by 2050. 1 To ensure better quality of life for this rising number of people with dementia, policymakers and researchers have recognized the vital role of the concept of ‘dementia‐friendliness’, 2 which resonates with the concepts of age‐friendliness and marks a fundamental shift from a focus on meeting the physical and health needs of an individual patient with dementia to a holistic approach supporting the person living with dementia within the community to achieve the best quality of life possible. 3 The concept of dementia friendliness can apply to a range of settings, such as acute care and hospitals, long‐term care (nursing homes) and community settings or neighbourhoods. 4 The most common settings are dementia friendly communities (DFCs), 3 , 5 , 6 which are intended to be places where people with dementia and their caregivers feel understood, respected, have access to support and feel confident they can contribute, participate and engage to community life. 3 , 7 , 8 DFCs can be characterized by their location, for example a city or neighbourhood, called “location‐based DFCs, or DFCs can be organisations or entities with a specific focus, for example an airport, summarised as “communities of interests”. 6 The urgency of DFCs is recognized by international health organizations 1 , 2 and adopted by many national policies. It has also been incorporated into research agendas to improve wellbeing for people with dementia and their caregivers. 9

Although there is some overlap between the usage of DFC and dementia friendly initiatives in the literature, dementia friendly initiatives (DFIs) can be thought of as building blocks in the development of DFCs 4 , 5 DFIs are activities that aim to promote dignity, empowerment, engagement and autonomy to enable the wellbeing of people with dementia and the needs of their caregivers throughout the dementia trajectory. 4 Examples of DFIs include local neighbourhood supermarkets where staff know how to respond and offer respectful services to people with dementia, or Alzheimer Cafes which anyone with an interest in dementia can attend and learn more about dementia and its implications. 10 DFIs can be found in small scale DFCs (e.g. a specific neighbourhood) or they can be more wide reaching (e.g. in a whole city).

There is an important link between DFCs and DFIs, because DFIs are embedded in DFC and their outcomes are vital to support DFCs. Previous studies on achieving DFCs have described this process mainly from a policy perspective, for example an improved support infrastructure. 3 , 11 Other studies have addressed the priorities of people with dementia and their caregivers in guiding achievements of DFCs, such as acceptance of dementia or connection to and engagement with community life. 8 , 12 , 13 , 14 Lastly, experiences of people with dementia living in a DFC were evaluated, for example their awareness of living in a DFC. 15

However, there has been no link with DFIs in such studies or an explication of how DFIs worked for people with dementia and contributed to the DFCs. Lastly, the effects of DFIs for caregivers remain underreported, 3 , 16 although DFC also concern them in terms of their position to people with dementia.

Previous research about DFIs has reviewed both theoretical features 4 and challenges in development. 17 Previous studies have also documented DFIs in European countries. 5 , 18 Williamson created a taxonomy for DFIs (DEM‐FACT), which distinguishes three categories of DFIs: the first focuses on community support, the second on community involvement and the third on the whole community and citizenship. 5 This taxonomy also descibes the resources needed for each category of DFI and links them to the development of DFCs. However, a systematic understanding of how DFI outcomes are achieved for people with dementia and their caregivers is lacking.

Increasing knowledge about how DFIs work for people with dementia and their caregivers is important, because such insights would support future development and evaluation of DFCs. For example; policy officers and professionals can examine in advance which resources are available and/or needed to develop a DFI, with which outcomes and for whom, for example for persons with dementia and/or caregivers. Furthermore, such outcomes can also be monitored to examine the establishment of a DFC.

Therefore, in this study, a literature review was performed using the rapid realist methodology. 19 The main goal of a realist approach is to illuminate ‘what works, for whom, in what contexts and why’ by describing causal explanations using context‐mechanisms‐outcome configurations in one or more realist programme theories. 20 , 21 A rapid realist methodology was preferred to other review methods, because it prioritizes deep understanding of contextual aspects and mechanisms in building outcomes which form the basis of a realist causal explanation. 19 , 22 Further, the realist approach can improve engagement of stakeholders including professionals, policymakers and (representatives of) service users. 19 , 23 , 24 With input from these stakeholders, the review enables identification of relevant interventions related to outcomes. 19

Our research question was: how do community based DFIs work for people with dementia and their caregivers, and why? This paper presents the first findings of a three phased project which aims to study success factors in DFIs using the realist approach (Mentality project, November 2018–April 2022), funded by The Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development (ZonMw). More information about Mentality can be found on www.Mentality.space.

2. METHOD

Conforming to the realist review approach, 19 , 23 , 24 content experts and stakeholders were invited to join an advisory panel affiliated with the Mentality project. This advisory panel consisted of experts in the field of dementia and public health, representatives of people with dementia and their caregivers and stakeholders from four Dutch municipalities seeking to become dementia friendly. This review was based on five iterative stages. 25

Developing and refining research questions.

Searching for and retrieving literature.

Screening and appraising literature.

Extracting and synthesizing literature.

Validation of findings.

2.1. Developing and refining research questions

The authors consulted the advisory panel at the start of the review to confirm that the research question for the review addressed relevant gaps in the literature and covered their key interests within their field of practice.

2.2. Searching and retrieving literature

The database searches were performed from April 1, 2018 until November 30, 2019. Two searches were developed using separate search strings and databases. The first search string consisted of a combination of the following search terms: dementia friendly OR dementia positive OR dementia capable OR age friendly OR senior friendly. The following databases were searched: PubMed, Embase, ASSIA and Google Scholar, since the concept of dementia friendly is reflected in medical, social and public health science and in societal relevant reports, Google Scholar was found suitable for the search in grey literature. After consultation with the advisory panel about the initial results of the first search, they proposed a secondary search to broaden the perspective on DFIs. The second search string consisted of a combination of the following terms: dementia OR dementi* OR amenti*, as a synonym for dementia, Mesh terms, OR Alzheimer* AND social environment OR social participation OR social inclusion OR social health OR social integration. The following databases were searched: PubMed, Embase, Cinahl and Google Scholar. Cinahl was used instead of ASSIA to broaden the search for DFIs. Both search strategies were piloted and refined in consultation with the information specialist of Radboud University. The full search strategy is available in the Supplementary File 1.

2.3. Screening and appraising literature

Inclusion criteria were studies describing DFIs that were embedded in a regional policy of becoming a DFC and which were freely accessible for people with dementia, caregivers and community members. Only studies with or using empirical data from people with dementia or caregivers were included. Studies were included if they were written in English or Dutch. There was no limitation on publication date. The exclusion criteria were: studies addressing medical interventions, individual interventions, therapeutic interventions in private home settings and medically indicated homecare or day care. Policy papers, descriptions of models or frameworks without empirical data and evaluations disregarding outcomes for people with dementia and their caregivers were also excluded.

Following the RAMESES guidelines for realist reviews, papers were not ranked or excluded based on an assessment of rigour but rather as fitting in the aims of this review. 21 , 26 , 27 Thus, papers were selected on their relevance in answering the research question and for richness of data. Literature selection was done in three stages: first, screening based on title; second, screening based on abstract; and third, review of full text for eligibility. In all three stages, selection was done by four reviewers (MT, ML, JP, RJ), who double screened titles and abstract and discussed content, relevance and inclusion of the full text papers' in pairs. If needed, a third researcher was involved to achieve consensus.

2.4. Extracting and synthesizing literature

Data extraction focused on identification and elucidation of context (C), mechanism (resources and responses) (M) and outcome (O) configurations (CMOc), including noteworthy quotes. 20 After dividing the papers (randomly), data extraction was carried out by the four authors independently (MT, ML, JP, RJ). Next, the four authors checked together whether extractions were completed in the same manner, led by the main researcher (MT). A data extraction form in Excel was used, which is available in the Supplementary File 2. To ensure consistency and transparency, the definitions of CMOc which have previously been applied and described by others 27 were used by all researchers in the data extraction. See Table 1 for definitions.

TABLE 1.

Definitions CMO

| Context | Mechanisms | Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Context pertains to the backdrop of an intervention. 28 It includes pre‐existing organizational structures, cultural norms and history of the community, nature and scope of pre‐existing networks and geographic location effects 28 e.g. previous experience with dementia friendly initiatives. | Mechanisms usually pertain to cognitive, emotional or behavioural responses to intervention resources and strategies. A mechanism‐resource refers to what is triggered among the context participants/stakeholders. 28 , 29 Mechanism response refers to the response of the participants, i.e. all that suggests a change in people's minds and actions. 28 , 29 | Outcomes refer to the intended or unexpected intervention outcomes, i.e. the result of how people react to the mechanisms 28 , 30 e.g. the health and wellbeing outcomes of people with dementia and caregivers. |

If information about context or mechanisms was not clearly stated by the authors of the included studies, reviewers supplemented the CMOc by abductive reasoning (i.e. examining evidence and developing hunches or ideas about the causal factors linked to that evidence). 31 Abductive reasoning was referenced using italics in the data extraction form to maintain recognizability.

Next, configurations were categorized in the DEM‐FACT taxonomy, 5 based on the description of the initiative in the paper. This taxonomy was selected because it links DFIs to the development of DFCs, as in our inclusion criteria, and because both the taxonomy and the CMOc adopted resources for analysing DFIs. To ensure rigour, categorization took place after data extraction to ensure that all information in the papers was read thoroughly prior to categorization.

Data synthesis used an analytical inductive approach, 32 starting with configurations per category in the DEM‐FACT taxonomy. First, similar outcomes were clustered, for example outcomes such as improved interaction, reduced stress or increased enjoyment. Second, commonalities of mechanisms and contexts were also clustered, for example mechanisms referring to feelings of confidence or motivation and contextual aspects such as provision of support or a mixed group of participants. Based on these clusters, patterns in outcomes, mechanisms and contexts were outlined. An example of such a pattern was contextual factors, such as provision of support and contact leading to mechanisms such as increased familiarity and confidence which lead to outcomes such as improved interaction or enjoyment. These outlines were compared with corresponding configurations and quotes to check for consistency and explanatory power. 33 Based on these outlines, synthesized configurations were developed. By recognizing how the outcomes of one configuration became (an aspect of) the context in another configuration, these ripple effects further expounded the synthesis. 28 For example, an outcome such as improved interaction became a resource of a next context in which people with dementia felt stimulated to enjoy an activity. Finally, for each category of DEM‐FACT, middle range programme theories (MRPT) were developed around the synthesized configurations and ripple effects to summarize the nature of the CMO links. Formulating realist programme theories at the midrange level, such as MRPT, enabled both the specification of contexts, resources and responses leading to outcomes and the conceptualization and explanation of those outcomes. 34

The main researcher (MT) carried out the synthesis and discussed the outlines and ripple effects with an independent researcher (WK), who had not previously been involved in the selection, extraction and synthesizing of the literature. The MRPT were refined with SD, who was an independent reviewer. Each step of data extraction and synthesis was prepared with all authors.

2.5. Validation of findings

In the final stage of the review, the authors presented the key findings to the advisory panel for their feedback. The members of the advisory panel confirmed the usefulness and applicability of the MRPT within their context or field of expertise and made suggestions for wording.

3. RESULTS

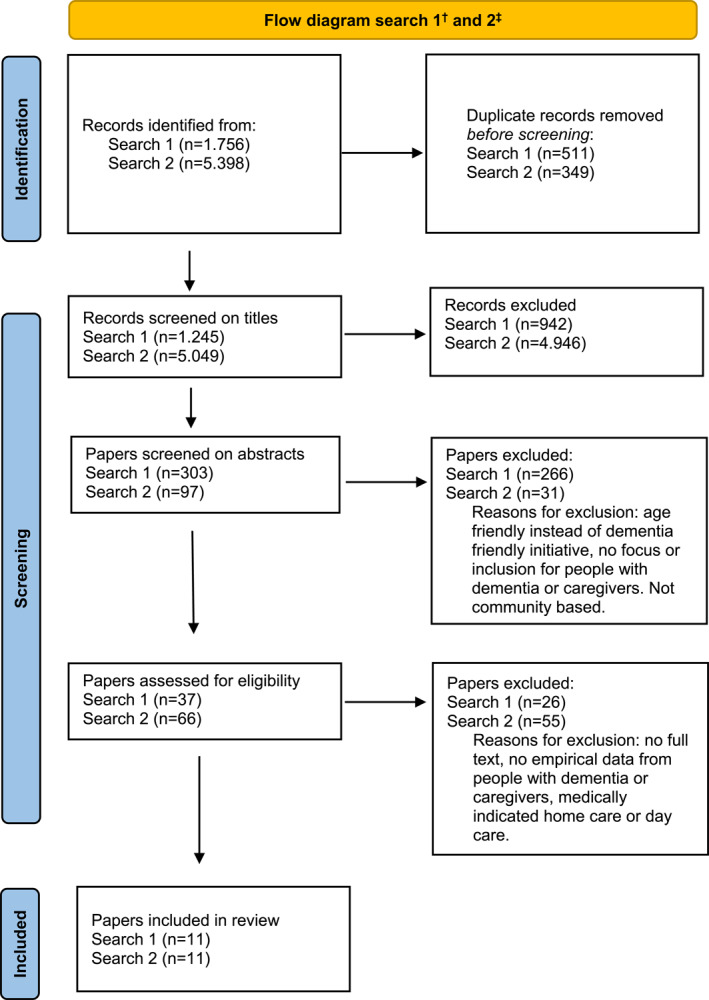

3.1. Studies retrieved

The database searches led to a total of 7154 published English language papers. After removing duplicates, 6294 papers from 2006 until 2019 were ready for initial screening based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The Figure 1 flow diagram illustrates the search results from search 1 & 2.

FIGURE 1.

Flow diagram search 1 & 2. †Search 1: search terms: dementia friendly OR dementia positive OR dementia capable OR age friendly OR senior friendly. Databases: PubMed, Embase, ASSIA and Google Scholar. ‡Search 2: search terms: a combination of dementia OR dementi* OR amenti* OR Alzheimer* AND social environment OR social participation OR social inclusion OR social health OR social integration. Data bases: PubMed, Embase, Cinahl and Google Scholar. Adapted from Page et al. 35

Of the 22 papers included, 11 were qualitative studies, 8 mixed methods studies and 3 quantitative studies. Table 2 presents an overview of the characteristics of the included papers, including their categorization in the DEM‐FACT taxonomy. See: Table 2: Overview of included papers; characteristics and categorization.

TABLE 2.

Included papers; characteristics and categorization

| Taxonomy category search | First author, year and country | Reference number | Study design | Participants | Characteristics of initiative | Aim of evaluation or research |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Community support 1 | Ward, 2018, England & Scotland, UK & Sweden | 41 | Participatory mapping | 14 carers | Neighbourhood support & physical activity | Lived experience about capabilities, capacities & competencies |

| Community support 2 | Wright, 2018. England, UK | 43 | Observation & interviews | 11 people with dementia interviewed, 19 people with dementia & 7 carers (informal & formal) observed | Exercise group, dance and walking groups | Effects on wellbeing and mood |

| Community support 2 | Nan, 2017. England, UK | 39 | Interviews | 11 carers | Dementia café ‐ offering support for carers | Experiences of carers at memory cafés |

| Community support 2 | Innovations in Dementia, 2011. England, UK | 36 | Interviews & survey | 24 people with dementia, 36 carers, 26 staff or volunteers | Public spaces, resources, networks | Challenges faced, spirit & determination |

| Community support 2 | Dow, 2011. Australia | 38 | Focus groups & observations | 37 people with dementia, carers, staff | Dementia café ‐ Social & educational service | Evaluation of service |

| Community support 1 | Mitchell, 2006. England, UK | 40 | Interviews, environmental assessment | 20 people with dementia, 25 people without dementia | Outdoor environment & lived at home or in sheltered accommodation | Interaction with outdoor environment, experiences and understanding. Identify design factors. |

| Community support 2 | Capus, 2006. England, UK | 37 | Focus group | 6 carers | Dementia café ‐ social interaction, share information, mutual support | Evaluation of service |

| Community involvement 1 | Hobden, 2019. England, UK | 47 | Interviews | 4 people with dementia, 4 carers, 6 organisers | Swimming ‐ social & physical activity | Experiences |

| Community involvement 2 | Windle, 2018. England & Wales | 53 | Interviews, self report & observation | 125 people with dementia | Art ‐ wellbeing & quality of life | Wellbeing and quality of life |

| Community involvement 1 | Gibson, 2017. Scotland, UK | 44 | Participatory, interviews and focus groups | 6 people with dementia, 5 carers (interviews) focus groups (n = 6) | Health walks ‐ development & training | Experiences |

| Community involvement 2 | Johnson, 2017. England, UK | 50 | Quantitative pre‐post, questionnaire | 66 people with dementia and carers | Art ‐ viewing group | Compare 2 activities on social activity & subjective wellbeing |

| Community involvement 1 | Carone, 2016. England, UK | 44 | Interviews | 5 people with dementia, 5 carers, 5 coaches, 5 organisers | Football ‐ social & physical wellbeing | Effect on people with dementia, carers, level of service provision |

| Community involvement 1 | Ovenden, 2019. England, UK | 46 | Interviews | 6 people with dementia, 10 carers, 6 organisers | Indoor bowling ‐ physical & mental activity | Perceived benefits for people with dementia and carers, success factors |

| Community involvement 2 | Camic, 2016. England, UK | 49 | Interviews & observations | 12 people with dementia & 12 carers | Art ‐ viewing, discussing, & making | Theoretical understanding of impact of viewing & making art |

| Community involvement 2 | Phinney, 2016. Canada | 48 | Ethnography | 12–15 people with dementia | Walking in the neighbourhood. | Social citizenship for people with young onset dementia |

| Community involvement 2 | Camic, 2014. England, UK | 52 | Quantitative & interviews pre‐post | 12 people with dementia and carers | Art ‐ viewing & making | Social inclusion, carer burden & quality of life |

| Community involvement 2 | Camic, 2013 | 51 | Quantitative & interviews | 10 people with dementia and 10 carers | Singing | Wellbeing, functioning & social exclusion |

| Whole community and citizenship 1 | Luxmoore, 2018. England, UK | 56 | Survey | 35 people with dementia | Event to showcase user‐led initiatives. | Co‐produced event to inspire |

| Whole community and citizenship 1 | Philipson, 2019. Australia | 57 | Participatory research | 147 community members, among which carers and people with dementia | Education activities | Changes in knowledge, attitudes and beliefs about dementia |

| Whole community and citizenship 1 | Reynolds, 2017. England, UK | 54 | Questionnaire | 109 audience members, including family and friends of people with dementia | Orchestra ‐ attitudes of members of audience | Impact of public perceptions |

| Whole community and citizenship 1 | McCabe, 2015. Scotland, UK | 55 | Interviews | 9 people with dementia, 3 carers. | Musical project | Evaluation of sense of purpose and enjoyment in creative music |

| Whole community and citizenship 1 | Dean, 2015. England, UK | 58 | Survey, focus groups Interviews | 15 interviews with people with dementia & stakeholders, 36 respondents to survey, further interviews | Socialise & promote wellbeing and provide different services | Evaluate dementia‐friendliness of city |

3.2. Synthesis of the papers

Evidence from these 22 papers led to the development of three MRPTs using CMOc. Each category of DEM‐FACT led to a MRPT. The category of community support led to MRPT 1: caring community, the category of community involvement led to MRPT 2: stimulating community and the category of the whole community and citizenship led to the MRPT 3: activating community. The CMOc, including supporting evidence from the papers, are available upon request.

3.3. Realist synthesis

3.3.1. MRPT 1: a caring community

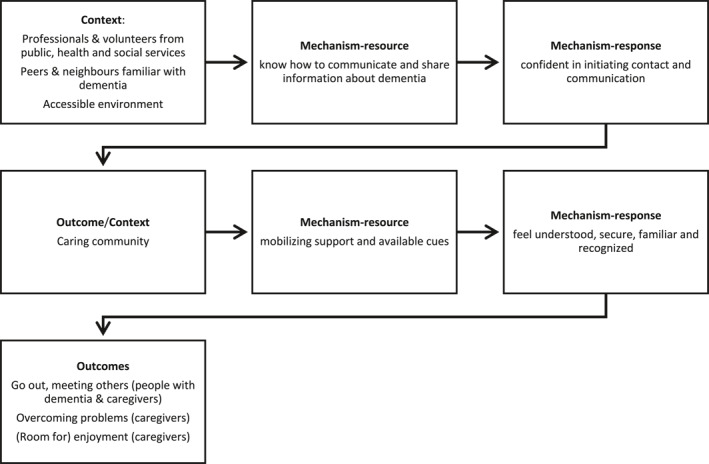

This section describes the MRPT of a caring community, which is supported by seven studies. Figure 2 outlines the characteristics of this MRPT.

FIGURE 2.

MRPT 1: caring community

This MRPT describes how DFIs used education in dementia, 36 sharing experiences 37 , 38 , 39 and adapting the social and physical environment 37 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 to create a caring community. Associated contextual characteristics were professionals from public and social services who shared their (personal) understanding and knew how to act and communicate with people with dementia and caregivers, 37 , 38 , 39 , 42 as well as neighbours and volunteers who felt familiar with the symptoms of dementia. 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 An additional feature of the context was an accessible physical environment providing support and landmarks. 38 , 41 , 42 , 43 These mechanism‐resources generated mechanism‐responses including the confidence of professionals and volunteers in initiating contact and communication with people with dementia and their caregivers. In this way, a caring community was created. By using the ripple effect concept, this community as an outcome became a new context which generated mechanisms and outcomes for people with dementia and their caregivers.

This caring community generated three outcomes: two outcomes for people with dementia and their caregivers and one for caregivers only. The first outcome was going out to supportive places 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 ; an example was walking in an adapted neighbourhood. The caring community provided resources such as social support and landmarks, which led to the responses of feeling understood and safety among people with dementia and caregivers. The second outcome, which was often combined with the first, was meeting others. 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 Examples were meeting fellow participants at a Dementia café, where the social support, as a resource, led to feelings of familiarity as a response. The third outcome, for caregivers only, was overcoming problems and (room for) enjoyment. 37 , 38 , 39 Examples included caregivers who met peers and professionals. Here, the same resource–social support–provoked feelings of recognition (response) and hence the outcome of overcoming problems (for caregivers).

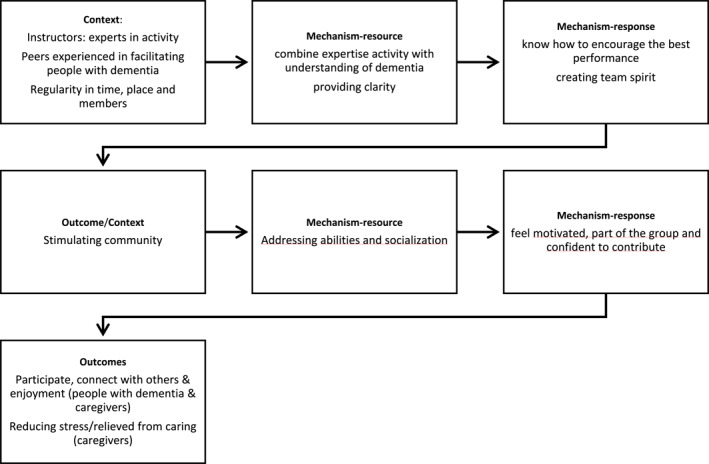

3.3.2. MRPT 2: a stimulating community

This section describes the MRPT of a stimulating community, which is supported by ten studies, the characteristics of which are outlined in Figure 3.

FIGURE 3.

MRPT 2: stimulating community

This MRPT describes how DFIs used physical exercise in a group 44 , 45 , 46 , 47 , 48 and exchanging and practising creative activities in a group 49 , 50 , 51 , 52 , 53 to create a stimulating community. Accompanying characteristics were instructors and peers, such as volunteers experienced in facilitating people with dementia. They combined their expertise in sports or creative activities with insights into dementia and complemented each other. Subsequently, they created team spirit and encouraged people with dementia and caregivers to reach maximum performance. 44 , 45 , 46 , 47 , 48 , 49 , 50 , 51 , 52 , 53 Another characteristic was regularity of activities in time and place and a fixed group, which provided a sense of routine. 44 , 45 , 47 , 48 As such, a stimulating environment was developed. By using the ripple effect concept, this community as an outcome became a new context which generated mechanisms and outcomes for people with dementia and their caregivers.

The stimulating community generated three outcomes: two for people with dementia and their caregivers and one for caregivers only. The first outcome was active participation in a group activity. 44 , 45 , 46 , 47 , 49 , 51 , 52 Examples included sport or singing in a choir, and the emphasis was on active involvement in the activity. The stimulating community provided resources such as addressing abilities instead of limitations and socialization with like‐minded group members. These resources then led to responses such as motivation, feeling like part of a group and confidence about participation during the activity. The second outcome, which was often combined with the first (active participation), was connecting with others and enjoying the activity together. 44 , 45 , 46 , 47 , 48 , 49 , 50 , 51 , 52 , 53 Examples were people with dementia who supported other participants, experienced good company and had fun together. Here, the emphasis was on the positive experience during the involvement of the activity. The third outcome, for caregivers only, was reduced stress and respite from caring. 44 , 45 , 46 , 47 , 49 , 52 Examples included experiencing a time‐out and having fun; some caregivers felt relieved that they were not ‘needed’ during the activity and others felt comfortable going home.

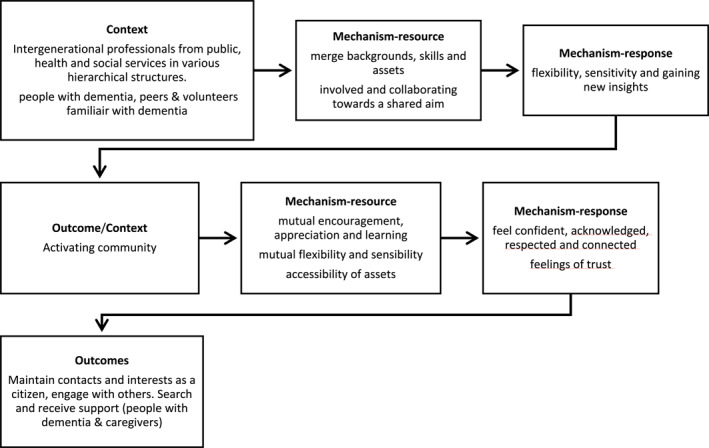

3.3.3. MRPT 3: an activating community

This section describes the MRPT for an activating community, which is supported by five studies. Figure 4 outlines the characteristics of this MRPT.

FIGURE 4.

MRPT 3: activating community

This MRPT describes how DFIs used the interdisciplinary organization of intergenerational activities in the community, together with people with dementia and their caregivers, to create an activating community. 54 , 55 , 56 , 57 , 58 Associated contextual characteristics were mixed groups of professionals, volunteers, caregivers and people with dementia, 54 , 55 , 56 , 58 coming from different organizations and associated hierarchical structures, 55 , 58 and involvement of both young and older people. 54 , 58 All merged their background, skills and community assets 55 , 57 , 58 ; participated equally in the activity 54 , 55 , 56 , 58 ; and had a significant role in achieving a shared goal. 54 , 55 , 56 , 57 , 58 These resources created responses such as sensitivity to and flexibility around each other's circumstances and gaining new insights from each other, which led to the creation of an activating community. By using the ripple effect concept, this activating community became the context which generated new mechanisms and outcomes for people with dementia and their caregivers.

This activating community generated three outcomes for both people with dementia and their caregivers. The first outcome was maintaining interests and contact with others. 54 , 55 , 56 , 58 An example was co‐organizing and participating in a music event, where a key factor was the maintenance of own activities and interests together with new and known people. Resources from this activating community were mutual encouragement, mutual appreciation and learning. This led to responses such as feelings of confidence and reciprocal acknowledgement. The second outcome was taking the initiative to go out and engage with others. 55 , 56 , 58 Examples were providing information and education about dementia to banks, retail establishments, doctors, church and clubs, planning a city trip or going out and engaging with others. The emphasis here was on contributing to society as a citizen using personal assets with both new and known people. Available resources were flexibility, sensitivity and assets from a shared network, which led to feeling respected and feeling connected with others. The third outcome was searching and receiving support 58 ; notable here was proactivity and self‐direction in the search and type of support. Important resources were flexibility and accessibility of assets and activities, and this led to feelings of acknowledgement of perceived needs and trust in services.

4. DISCUSSION

The purpose of this review was to increase our understanding of how outcomes of DFIs work for people with dementia and their caregivers, and why. Our review provides an analysis of different DFIs, which were grouped into categories of community support, community involvement or whole community and citizenship, leading to three types of communities: caring, stimulating and activating. Subsequently, these communities became the next context and generated mechanisms and outcomes for people with dementia and caregivers, illustrating a ripple effect of CMOc.

A common thread in these outcomes was having contact with others, although the content this contact differed among the communities–ranging from meeting others in the caring community to connecting with others in the stimulating community and engaging with others in the activating community. Another outcome was enjoyment with different characteristics in each community. In the caring community, enjoyment had a small role, and only for the caregiver, whereas enjoyment was a prominent outcome for both people with dementia and caregiver in the stimulating community. Rather than enjoyment, engagement with others and maintenance of interests were outcomes for both people with dementia and caregivers in the activating community. Finally, outcomes in all communities reflected aspects of support. In the caring and stimulating community, caregivers reported, respectively, overcoming problems and reduction of stress. Searching and finding support were outcomes for both caregivers and people with dementia in the activating community.

Outcomes about having contact resonate with the literature about the importance of connection and engagement for people with dementia and their caregivers in their own community. 3 , 8 , 12 , 13 , 59 , 60 Moreover, our study highlights how each category of DFI–via caring, stimulating and activating communities–generated different social contacts, with an increase in closeness in having contact. The differences in social contacts–including meeting others, connecting with others and engaging with others–can be explained by looking at the context and the accompanying mechanisms of the DFIs in the caring, stimulating and activating communities. In DFIs in the caring community, such as Alzheimer's cafés, the consequences of dementia are central, while in the DFIs in the stimulating community, such as sports activities, a shared interest brings people together, and in the DFIs of the activating community, such as organizing a congress, people are joined in a shared ambition. Subsequently, the roles of people with dementia and their caregivers differ from being a patient to a team‐member and/or to an active citizen, and the outcomes are associated with these roles.

Outcomes of enjoyment and decreased stress are also reflected in a number of studies about dementia friendly leisure. 61 , 62 , 63 Attention has been paid to the barriers and support needed to undertake leisure activities by people with dementia and their caregivers 61 , 62 and benefits of leisure according to people with dementia. 63 This supports the explanation in this study for how enjoyment and decreased stress are associated with a space for being with others, undertaking an activity together, fostering a sense of connection and team spirit with others. Our study also indicates the importance of contextual aspects such as expertise in the activity alongside understanding of dementia. An instructor with expertise knows the activity thoroughly and can encourage participants to achieve their best performance. Here, the understanding of dementia is an equally important contextual factor as expertise in the activity. The equal importance of expertise in the activity and in handling dementia also explains how outcomes of both enjoyment and decreased stress also apply for the caregiver, because they can focus on themselves during the activity or choose other ways to spend their time because the demand for caregiving may be relieved.

Support was an outcome that resonated in the DFIs in all communities. Support is an important part of the DFCs to which initiatives contribute. 3 , 7 Support as an outcome addressed the caregivers during initiatives in the caring and stimulating communities in particular. Support in the activating community took place during the activities and drew attention to the active role of people with dementia, which here is both an outcome and a contextual aspect. Studies about similar activities described how the priorities of people with dementia and others differed in campaigning 64 , 65 and challenges in activism because of the stereotypes around people with dementia. 66 Our study explained how people with dementia and caregivers can be enabled to be active citizens and how this constructed the outcomes. As such, people with dementia and their caregivers themselves were in control of their support instead of professionals.

The outcomes and mechanisms of the caring, stimulating and activating communities, are in line with the purpose of a DFC–namely, to be a place where people with dementia and their caregivers feel understood, respected, have access to support and feel confident they can contribute, participate and engage to community life. Moreover, our findings provide more depth by showing how seemingly similar feelings are built from different contexts and also lead to different outcomes. For example, feelings of being understood as a mechanism yield different outcomes in a caring community than in an activating community. For practice, such information is important to understand how a DFI can yield different outcomes and which resources are needed to achieve those outcomes. It also supports the reflection of which DFIs are required and/or feasible and for whom, for example people with dementia or caregivers. Although DFCs respond to the appeal to recognize the rights of persons with dementia as active citizens, it is important to consider the resources, commitment and capacity available for a DFI. That may imply that DFIs leading to caring–or stimulating communities are more appropriate or realistic for new DFC. Although DFCs respond to the appeal to recognize the rights of people with dementia as active citizens, it is important to represent a start of a development process towards an activating community and corresponding outcomes. 5 Evaluating the outcomes of DFIs is an crucial aspect of monitoring the purpose of a DFC. 4 , 5 Our findings could inform both qualitative and quantitative research, which underpin the evolution of new DFCs and the development of existing ones from the perspective of both the people with dementia and their caregivers. 15

Traditional systematic reviews might miss out on the hidden mechanisms or causal factors interacting within a particular context. 22 The strength of this rapid realist review is that it allowed us to examine the heterogeneity and complexity of various studies reporting on DFI outcomes, which led to a richer set of outcome data from the perspective of people with dementia and their caregivers. Next, this study gained a deep understanding of the range of mechanisms and their interaction with the community where DFIs take place. Two comprehensive search strategies–the input of the advisory panel and the use of a ripple effect of CMOc–deepened the analysis and thus were important strengths of this study. The choice to use DEMFACT to categorize DFIs matched the definition of DFIs and their role in the development of DFCs, as described in the introduction and inclusion criteria. For example, Activities of Daily Living (ADL) did not appear in DEMFACT, while they did appear in other taxonomies such as the taxonomy for social activities. 67 Furthermore, DEMFACT was also aligned with data extraction because both the taxonomy and the data extraction adopted resources for analysing DFIs. However, the choice of DEMFACT as the taxonomy influenced the development of the MRPTs.

Although our review does not cover all prevailing DFIs, a comparison with other recent studies does indicate that the included papers are relevant and representative for DFIs. 5 , 15 , 18 However, there is a risk of publication bias for other types of DFIs, which may be underreported such as DFIs about employment for people with dementia. There is a risk that evidence was excluded which may have been informative for theory development. For example, other realist reviews may include editorial or policy articles; however, our review focused on empirical studies, so our criteria excluded these types of documents. Further, although self‐reported data were anticipated, some papers also used data from professionals, peers or community members about DFI outcomes that could not be separated from self‐reported data and blurred the evidence.

5. CONCLUSION

This study demonstrates how the outcomes of DFIs for both people with dementia and their caregivers are built. It offers guidance for communities wishing to become dementia‐friendly that is appropriate and realistic for the purpose of an DFC, together with the resources, commitment and capacity available. It also shows how DFIs can attribute a specific role to people with dementia, such as patient, team member or active citizen. It draws attention to the multiple aspects of DFCs, including the participation of people with dementia, and supports reflection on its core elements–namely, recognizing and supporting the rights of people with dementia. Our MRPTs may be used to plan DFIs in a theory‐informed way and support or test DFCs in achieving their purpose. To arrive at an in‐depth understanding of which DFIs work for whom, it is necessary to have a deeper understanding of the demographics of the people with dementia and carers who participate in those DFIs. It is also important to gain an understanding of the individual characteristics of people with dementia who choose to participate in DFIs, compared to those who do not.

This study provides transparency about DFI outcomes and a reference point for future research in which these theories can be tested and refined. The results have informed the next phase of the Mentality study, in which the theories found here will be tested and refined using empirical data from nascent DFCs.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

There is no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

Supplementary Material 1

Supplementary Material 2

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank Dr. Sonia Dalkin for her feedback and refinement of the MRPT.

Thijssen M, Daniels R, Lexis M, et al. How do community based dementia friendly initiatives work for people with dementia and their caregivers, and why? A rapid realist review. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2021;1‐14. 10.1002/gps.5662

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Datasets analysed during the current study are available in the DANS EASY archive using the following link: https://doi.org/10.17026/dans‐x3z‐8m2z. These datasets were a re‐analysis of existing data, which are openly available at locations cited in the reference section.

REFERENCES

- 1. WHO . Global Action Plan on the Public Health Response to Dementia 2017 ‐ 2025. WHO; 2017. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/global‐action‐plan‐on‐the‐public‐health‐response‐to‐dementia‐2017‐‐‐2025 [Google Scholar]

- 2. WHO . Dementia; 2019. https://www.who.int/news‐room/fact‐sheets/detail/dementia [Google Scholar]

- 3. Alzheimer’s Disease International . Dementia Friendly Communities Key Principles. Alzheimer’s Disease International; 2016. https://www.alzint.org/u/dfc‐principles.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hebert CA, Scales K. Dementia friendly initiatives: A state of the science review. Dementia. 2019;18(5):1858‐1895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Williamson T. Mapping Dementia‐Friendly Communities across Europe: A Study Commissioned by the European Foundations’ Initiative on Dementia; 2016. https://ec.europa.eu/eip/ageing/sites/eipaha/files/results_attachments/mapping_dfcs_across_europe_final.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 6. Buckner S, Darlington N, Woodward M, et al. Dementia friendly communities in England: A scoping study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatr. 2019;34(8):1235‐1243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Alzheimer Society . Guidance for Communities Registering for the Recognition Process for Dementia‐Friendly Communities; 2013. https://www.alzheimers.org.uk/sites/default/files/2018‐06/DFC%20Recognition%20process%20‐%20Guidance%20for%20communities_FS%20albert_4.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 8. Smith K, Gee S, Sharrock T, Croucher M. Developing a dementia‐friendly Christchurch: perspectives of people with dementia. Australas J Ageing. 2016;35(3):188‐192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. ZonMw . Memorabel: Dementia Research and Innovation Programme; 2013. https://www.zonmw.nl/en/research‐and‐results/the‐elderly/programmas/programme‐detail/memorabel/ [Google Scholar]

- 10. Alzheimer Disease International . Dementia Friendly Communities. https://www.alzint.org/what‐we‐do/policy/dementia‐friendly‐communities/alzheimer‐cafes/ [Google Scholar]

- 11. Buckner S, Mattocks C, Rimmer M, Lafortune L. An evaluation tool for Age‐friendly and dementia friendly communities. Work Older People. 2018;22(1):48‐58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Harding AJE, Morbey H, Ahmed F, et al. What is important to people living with dementia?: the “long‐list” of outcome items in the development of a core outcome set for use in the evaluation of non‐pharmacological community‐based health and social care interventions. BMC Geriatr. 2019;19(1):94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chen M‐C, Huang H‐L, Chiu Y‐C, et al. Experiences of living in the community for older Aboriginal persons with dementia symptoms in Taiwan. Gerontologist. 2020;60(3):525‐534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wu S‐M, Huang H‐L, Chiu Y‐C, et al. Dementia‐friendly community indicators from the perspectives of people living with dementia and dementia‐family caregivers. J Adv Nurs. 2019;75(11):2878‐2889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Darlington N, Arthur A, Woodward M, et al. A survey of the experience of living with dementia in a dementia‐friendly community. Dementia. 2021;20(5):1711‐1722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Novak LS, Horne E, Brackett JR, Meyer K, Ajtai RM. Dementia‐friendly communities: A review of current literature and eflections on implementation. Curr Geriatr Rep. 2020;9(3):176‐182. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Shannon K, Bail K, Neville S. Dementia‐friendly community initiatives: An integrative review. J Clin Nurs. 2019;28(11‐12):2035‐2045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Barclay G, Tatler R, Kinross S. Dissimination Report (Deliverable 2.5). European Union Joint Action Act on Dementia; 2019. https://ec.europa.eu/research/participants/documents/downloadPublic?documentIds=080166e5ca1d18a5&appId=PPGMS [Google Scholar]

- 19. Saul JE, Willis CD, Bitz J, Best A. A time‐responsive tool for informing policy making: rapid realist review. Implement Sci. 2013;8(1):103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Pawson R, Greenhalgh T, Harvey G, Walshe K. Realist review‐‐a new method of systematic review designed for complex policy interventions. J Health Serv Res Pol. 2005;10(1_suppl):21‐34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wong G. Data gathering in realist reviews: looking for needles in haystacks. In: Emmel N, Greenhalgh J, Manzano A, Monaghan M, Dalkin S, eds. Doing Realist Research. Sage; 2018:131‐146. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Jagosh J. Realist synthesis for public health: building an ontologically deep understanding of how programs work, for whom, and in which contexts. Annu Rev Publ Health. 2019;40(1):361‐372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Abrams R, Park S, Wong G, et al. Lost in reviews: looking for the involvement of stakeholders, patients, public and other non‐researcher contributors in realist reviews. Res Synth Methods. 2021;12(2):239‐247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Abrams R, Park S, Wong G, et al. Contributor involvement in realist reviews: a review of reviews. International conference for realist research, evaluation and synthesis. Online 16–18 February 2021.

- 25. Willis CD, Saul J, Bevan H, et al. Sustaining organizational culture change in health systems. J Health Organisat Manag. 2016;30(1):2‐30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Pawson R. Digging for nuggets: how ‘bad’ research can yield ‘good’ evidence. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2006;9(2):127‐142. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wong G, Greenhalgh T, Westhorp G, Buckingham J, Pawson R. RAMESES publication standards: realist syntheses. BMC Med. 2013;11(1):21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Jagosh J, Bush PL, Salsberg J, et al. A realist evaluation of community‐based participatory research: partnership synergy, trust building and related ripple effects. BMC Publ Health. 2015;15(1). 10.1186/s12889-015-1949-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Dalkin SM, Greenhalgh J, Jones D, Cunningham B, Lhussier M. What’s in a mechanism? Development of a key concept in realist evaluation. Implement Sci. 2015;10(1):49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Westhorp G. Realist Impact Evaluation: An Introduction Published online; 2014. https://odi.org/en/publications/realist‐impact‐evaluation‐an‐introduction/ [Google Scholar]

- 31. Jagosh J, Pluye P, Wong G, et al. Critical reflections on realist review: insights from customizing the methodology to the needs of participatory research assessment: realist Review Methodology Reflection. Res Synth Methods. 2014;5(2):131‐141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Byng R, Norman I, Redfern S. Using realistic evaluation to evaluate a practice‐level intervention to improve primary healthcare for patients with long‐term mental illness. Evaluation. 2005;11:69‐93. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Gilmore B, McAuliffe E, Power J, Vallières F. Data analysis and synthesis within a realist evaluation: toward more transparent methodological approaches. Int J Qual Methods. 2019;18:160940691985975. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Jagosh J, 2019. Realist Programme Theory, Middle‐Range Theory (Formal Theory), Middle‐Range Programme Theory. CARES Summer School, Southampton 5‐8 August 2019. Southampton: 2‐25.

- 35. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2021;10(1):89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Innovations in dementia. Dementia Capable Communities The Views of People with Dementia and Their Supporters; 2011. https://www.housinglin.org.uk/_assets/Resources/Housing/OtherOrganisation/DementiaCapableCommunities_fullreportFeb2011.pdf

- 37. Capus J. The Kingston Dementia Café: the benefits of establishing an Alzheimer café for carers and people with dementia. Dementia. 2005;4(4):588‐591. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Dow B, Haralambous B, Hempton C, Hunt S, Calleja D. Evaluation of Alzheimer’s Australia vic memory lane cafés. Int Psychogeriatr. 2011;23(2):246‐255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Greenwood N, Smith R, Akhtar F, Richardson A. A qualitative study of carers’ experiences of dementia cafés: a place to feel supported and be yourself. BMC Geriatr. 2017;17(1). 10.1186/s12877-017-0559-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Mitchell L, Burton E. Neighbourhoods for life: designing dementia‐friendly outdoor environments. Qual Ageing. 2006;7(1):26‐33. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ward R, Clark A, Campbell S, et al. The lived neighborhood: understanding how people with dementia engage with their local environment. Int Psychogeriatr. 2018;30(6):867‐880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Innovations in Dementia: Dementia Capable Communities The Views of People with Dementia and Their Supporters; 2011. https://www.housinglin.org.uk/_assets/Resources/Housing/OtherOrganisation/DementiaCapableCommunities_fullreportFeb2011.pdf

- 43. Wright A. Exploring the relationship between community‐based physical activity and wellbeing in people with dementia: a qualitative study. Ageing Soc. 2018;38(3):522‐542. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Carone L, Tischler V, Dening T. Football and dementia: A qualitative investigation of a community based sports group for men with early onset dementia. Dementia. 2016;15(6):1358‐1376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Gibson G, Robertson J, Pemble C. Dementia Friendly Walking Project: Evaluation Report; 2017. http://www.pathsforall.org.uk/pfa/news/new‐research‐by‐the‐university‐of‐stirling‐on‐our‐dementia‐friendly‐walking‐project.html [Google Scholar]

- 46. Ovenden I, Dening T, Beer C. “Here everyone is the same” ‐ A qualitative evaluation of participating in a Boccia (indoor bowling) group: innovative practice. Dementia. 2019;18(2):785‐792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Hobden T, Swallow M, Beer C, Dening T. Swimming for dementia: An exploratory qualitative study: innovative practice. Dementia. 2019;18(2):776‐784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Phinney A, Kelson E, Baumbusch J, O’Connor D, Purves B. Walking in the neighbourhood: performing social citizenship in dementia. Dementia. 2016;15(3):381‐394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Camic PM, Baker EL, Tischler V. Theorizing how art gallery interventions impact people with dementia and their caregivers. Gerontologist. 2016;56(6):1033‐1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Johnson J, Culverwell A, Hulbert S, Robertson M, Camic PM. Museum activities in dementia care: using visual analog scales to measure subjective wellbeing. Dementia. 2017;16(5):591‐610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Camic PM, Williams CM, Meeten F. Does a “Singing Together Group” improve the quality of life of people with a dementia and their carers? A pilot evaluation study. Dementia. 2013;12(2):157‐176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Camic PM, Tischler V, Pearman CH. Viewing and making art together: a multi‐session art‐gallery‐based intervention for people with dementia and their carers. Aging Ment Health. 2014;18(2):161‐168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Windle G, Joling KJ, Howson‐Griffiths T, et al. The impact of a visual arts program on quality of life, communication, and well‐being of people living with dementia: a mixed‐methods longitudinal investigation. Int Psychogeriatr. 2018;30(3):409‐423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Reynolds L, Innes A, Poyner C, Hambidge S. “The stigma attached isn’t true of real life”: challenging public perception of dementia through a participatory approach involving people with dementia (Innovative Practice). Dementia. 2017;16(2):219‐225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. McCabe L, Greasley‐Adams C, Goodson K. “What I want to do is get half a dozen of them and go and see Simon Cowell”: reflecting on participation and outcomes for people with dementia taking part in a creative musical project. Dementia. 2015;14(6):734‐750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Luxmoore B, Marrett C, Calvert L, et al. Evaluation of the Good Life Festival: a model for co‐produced dementia events. Ment Health Pract. 2018;21(6):26‐31. [Google Scholar]

- 57. Phillipson L, Hall D, Cridland E, et al. Involvement of people with dementia in raising awareness and changing attitudes in a dementia friendly community pilot project. Dementia. 2019;18(7‐8):2679‐2694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Dean J, Silversides K, Crampton J. Evaluation of the York Dementia Friendly Communities Programme. Joseph Rowntree Foundation; 2015. https://www.jrf.org.uk/report/evaluation‐york‐dementia‐friendly‐communities‐programme [Google Scholar]

- 59. Silverman M. Dementia‐friendly neighbourhoods in Canada: A carer perspective. Can J Aging. 2021;40(3):451‐462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Hicks B, Innes A, Nyman SR. Experiences of rural life among community‐dwelling older men with dementia and their implications for social inclusion. Dementia. 2021;20(2):444‐463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Matthijsse M, Van de Velde I, De Klerk‐Jolink N, Timmermans O. Exploring experiences and perspectives of people living with dementia and their informal carers and entrepreneurs on dementia friendly leisure activities. Int J Integr Care. 2018;18(s2):140. [Google Scholar]

- 62. Innes A, Page SJ, Cutler C. Barriers to leisure participation for people with dementia and their carers: An exploratory analysis of carer and people with dementia’s experiences. Dementia. 2016;15(6):1643‐1665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Dupuis SL, Whyte C, Carson J, Genoe R, Meshino L, Sadler L. Just dance with me: an authentic partnership approach to understanding leisure in the dementia context. World Leis J. 2012;54(3):240‐254. [Google Scholar]

- 64. Haapala I, Carr A, Biggs S. What you say and what I want: priorities for public health campaigning and initiatives in relation to dementia. Australas J Ageing. 2019;38(Suppl 2):59‐67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Haapala I, Carr A, Biggs S. Differences in priority by age group and perspective: implications for public health education and campaigning in relation to dementia. Int Psychogeriatr. 2018;30(11):1583‐1591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Bartlett R. Citizenship in action: the lived experiences of citizens with dementia who campaign for social change. Disabil Soc. 2014;29(8):1291‐1304. [Google Scholar]

- 67. Levasseur M, Richard L, Gauvin L, Raymond É. Inventory and analysis of definitions of social participation found in the aging literature: proposed taxonomy of social activities. Soc Sci Med. 2010;71(12):2141‐2149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Material 1

Supplementary Material 2

Data Availability Statement

Datasets analysed during the current study are available in the DANS EASY archive using the following link: https://doi.org/10.17026/dans‐x3z‐8m2z. These datasets were a re‐analysis of existing data, which are openly available at locations cited in the reference section.