Abstract

Background

Chronic unilateral vestibulopathy (CUVP) is often accompanied by dizziness and postural instability, which restrict patients' daily activities. It is important to understand central compensation mechanisms underlying these symptoms in patients with CUVP by evaluating their brain functional status.

Purpose

To analyze the changes in resting‐state intranetwork and internetwork functional connectivity (FC) and explore the state of central vestibular compensation in patients with CUVP.

Study type

Retrospective.

Population

Eighteen patients with right‐sided CUVP and 18 age‐ and sex‐matched healthy controls.

Field strength/sequence

A 3.0 T, three‐dimensional magnetization‐prepared rapid gradient‐echo (MP‐RAGE) and resting‐state echo‐planar imaging (EPI) functional MRI sequences.

Assessment

FC alterations were explored using independent component analysis (ICA). Twelve independent components were identified via ICA. Dizziness Handicap Inventory (DHI) score for all patients was determined.

Statistical tests

Two‐sample t test, family‐wise error (FWE) correction, Pearson correlation coefficient (r). A P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Compared with healthy controls, patients with CUVP showed significantly decreased FC in the right middle occipital gyrus within the lateral visual network, and significantly increased FC in the right supplementary motor area within the sensorimotor network. The FC was decreased between the medial visual and auditory networks, the right frontoparietal and posterior default networks, as well as the sensorimotor and auditory networks. There was a significant negative correlation between the FC changes in the visual, auditory networks and the DHI score in patients with CUVP (r = −0.583).

Data conclusion

Compared to healthy controls, the FC was significantly decreased in the right visual cortex and significantly enhanced in the right sensorimotor network in patients with CUVP. Patients with CUVP showed decreased FC between multiple whole‐brain networks, suggesting that abnormal integration of multisensory information may be involved in the occurrence of chronic dizziness and instability in patients with CUVP.

Level of evidence

4

Technical Efficacy

Stage 2.

Keywords: chronic unilateral vestibulopathy, resting‐state fMRI, independent component analysis, visual network, sensorimotor network

Chronic unilateral vestibulopathy (CUVP) is not uncommon in clinical practice and is usually secondary to acute unilateral vestibulopathy (AUVP), which can last for 3 months or more. 1 CUVPs are often accompanied by symptoms such as chronic dizziness and/or postural instability, which seriously affect patients' quality of life. 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 In clinical practice, clinicians often pay more attention to the evaluation of the degree of peripheral damage and symptomatic treatment but ignore the evaluation of central compensation and individualized vestibular rehabilitation programs. 5 At the early stage of the static compensation process after AUVP, static symptoms, such as spontaneous nystagmus, skew deviation and balance disturbance, can occur. 2 These are mostly relieved by initiating static compensation progress at the level of the vestibular nuclei of the brainstem within 4–6 weeks. 2 , 3 , 4 Afterward, dizziness and instability can still be induced during daily high‐frequency and high‐speed activities, so central dynamic compensation needs to be initiated 6 , 7 , 8 and corresponding sensory and behavioral substitutions achieved to form a new control strategy. However, central dynamic compensation is slow and incomplete, resulting in the evolution to chronicity and CUVP over time. 1 , 2 , 3 , 6 , 7

In recent years, functional MRI (fMRI) has been widely used to investigate vestibular compensation mechanisms, and provides an important tool for investigating patients with unilateral vestibulopathy (UVP). 3 Helmchen et al 8 conducted an fMRI study on patients with vestibular neuritis. In that study, a brain network including parietal lobe, superior parietal lobule, posterior cingulate gyrus, middle frontal gyrus, middle temporal gyrus, parahippocampal gyrus, anterior cingulate gyrus, insular lobe, and putamen was isolated by independent component analysis (ICA). This network participates in spatial orientation and multisensory integration. 9 In the acute phase, the resting‐state functional activity of the network was decreased, especially in the intraparietal sulcus. Brain function returned to normal after 3 months, and the greater the change, the better the prognosis. Further analysis revealed that the degree of improvement in brain network function was related to the degree of recovery of clinical symptoms, suggesting that the body had undergone continuous sensory remodeling with central compensation. At present, studies of brain function changes in patients with unilateral vestibulopathy have mainly focused on patients with complete compensation during the acute and recovery (3 months) phases. 8 , 10 , 11 However, a previous study 12 has shown that when disturbing vision and proprioception, patients with CUVP have greater center‐of‐pressure sway compared to healthy subjects. These patients rely more on vision and somatosensory inputs to maintain their balance. This finding suggests that sensory substitution is involved in central dynamic compensation. 12 The achievement of central vestibular compensation depends more on the brain network composed of multiple brain regions and the synergy between multiple brain networks. 9 , 13 Therefore, it is important to understand the pathophysiological and central compensation mechanisms underlying chronic dizziness and instability in patients with CUVP by systematically evaluating brain functional status based on multiple whole‐brain functional networks.

Consequently, the aim of this study was to investigate the alterations in brain network connectivity patterns in patients with CUVP by using ICA, to explore whether the central vestibular dynamic compensation mechanisms underlying CUVP are involved in the chronicity of clinical symptoms, and thus to provide a scientific theoretical basis for the clinical diagnosis and vestibular rehabilitation of CUVP.

Subjects and Methods

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Peking University Aerospace School of Clinical Medicine. All subjects volunteered to participate in this study and signed informed consent.

Subjects

Eighteen patients with right‐sided CUVP who were treated in our hospital from September 2018 to September 2019 were included in this study. There were 6 males and 12 females, with an average age of 47.94 ± 11.01 years, all patients were right handed. Inclusion criteria were 1) patients who had a previous history of acute vestibular syndrome, with acute onset of persistent vertigo/dizziness and instability lasting days to weeks; and 2) patients with progressive acute vestibular dysfunction who did not have a full recovery and still presented with persistent dizziness instability after 3 months. CUVP was diagnosed according to the caloric test, UVP was defined as a reduced response of >25% (i.e. canal paresis [CP] > 25%) on one side, as calculated using Jongkees' formula. 14 Exclusion criteria were patients who had ophthalmic disease, eye movement disorders or who were unable to see objects; patients who had severe cervical spondylosis, severe cardiovascular disease, severe central nervous system disease; patients with contraindication to MRI, such as claustrophobia; and patients who had previous history of acute vestibular syndrome accompanied by auditory symptoms (such as hearing loss or tinnitus), central vestibular disorders, head injury, severe anxiety or depression.

Detailed medical information of all patients, including sex, age, current medical history (disease duration, symptoms during onset, onset duration, onset triggers, trigger factors, and concomitant symptoms) and past medical history, was collected. All patients underwent vestibular evaluations such as videonystagmography (VNG) evaluation, caloric test, video head impulse test (vHIT), and vestibular evoked myogenic potential test (VEMP). Routine brain MRI was also performed to exclude severe neurological diseases. Dizziness Handicap Inventory (DHI) score for all patients was determined. 15

Eighteen age‐ and gender‐matched healthy subjects were also included in the study during the same period. They were all right handed. All patients and subjects underwent fMRI.

Image Acquisition

The images were acquired using a 3.0‐T MR scanner (MAGNETOM Skyra syngo MR D13; Siemens, Germany) with a 16‐channel head and neck coil. During image acquisition, subjects' heads were fixed using foam padding to reduce movement, and earplugs were used to reduce scanner noise. Subjects were instructed to relax, keep eyes closed, and stay awake during scanning. Structural images were recorded using a three‐dimensional magnetization‐prepared rapid gradient‐echo (MP‐RAGE) sequence with the following parameters: repetition time (TR) = 1900 msec, echo time (TE) = 2.43 msec, flip angle = 8°, field of view (FOV) = 256 × 256 × 256 mm3, voxel size: 1.0 × 1.0 × 1.0 mm3, and a total of 192 slices were acquired. Functional images were obtained using an echo‐planar imaging (EPI) sequence with the following parameters: TR = 2000 msec, TE = 30 msec, flip angle = 90°, FOV = 222 × 222 × 222 mm3, voxel size = 3.0 × 3.0 × 3.0 mm3. A total of 200 volumes were collected with a scanning time of 6 minutes and 48 seconds. All subjects remained awake during the scan and no significant discomfort was reported during or after the scan.

Preprocessing of fMRI Data

fMRI data were processed with DPABI software on the MATLAB2013 platform. 16 Data were converted from DICOM to NIFTI format. The first 10 time points of the functional images in each patient were deleted due to the possible instability of the initial MRI signal. Then slice timing and realignment were conducted. To ensure the accuracy of the position information, subjects with excessive head motion (1.5 mm translation or 1.5°rotation in x, y, or z) were excluded. Furthermore, using DARTEL (http://rfmri.org/dpabi), fMRI images were spatially normalized to Montreal Neurological Institute space and resampled to 3 × 3 × 3 mm3 cubic voxels. Finally, images were smoothed using Gaussian kernel with full‐width at half‐maximum of 8 mm to reduce registration errors and increase the normality of the data.

Independent Component Analysis

ICA was performed using GIFT software (Version3.0a, http://mialab.mrn.org/software/gift/index.html). 1) Data reduction was conducted using principle component analysis; 2) the minimum description length was used to estimate the number of independent components; 3) the infomax algorithm was utilized for group ICA analysis. To ensure data repeatability, we performed the ICASSO 17 for 100 times; and (4) the independent component (IC) time courses and spatial map of individual subjects were reverse reconstructed using spatial–temporal regression. After the reverse reconstruction, the time course of each participant's IC and space IC was acquired and the spatial map was converted into a z‐score. The network components were identified in accordance with a previous study. 17 In totally, 12 independent components were obtained.

Statistical Analysis

INTRANETWORK FUNCTIONAL CONNECTIVITY ANALYSIS

For each independent component of all subjects, two‐tailed two‐sample t‐test was conducted in healthy controls and patients with CUVP, respectively, to generate sample‐specific spatial map and spatial pattern MASK for each network component. Multiple comparisons were corrected with the false discovery rate (cluster‐level FDR) method (P < 0.05). Each mask of the healthy controls and CUVP patients was further combined into the total MASK of each component. Then, a two‐tailed two‐sample t‐test with regressing covariates, such as age and gender, was conducted to compare the FC differences within each network component between CUVP patients and healthy controls. The results of multiple comparisons were corrected by family‐wise error (cluster‐level FWE) (P < 0.05). Mean z scores of brain regions with significant FC difference was extracted by using the software tool kit (REST) and was compared across groups by using an SPSS software.

INTERNETWORK FC ANALYSIS

To evaluate functional network connectivity (FNC) between the network components identified using ICA, time courses of 12 network components for each subject were detrended and despiked using 3dDespike5, filtered using a fifth‐order Butterworth low‐pass filter with a high‐frequency cutoff of 0.15 Hz. Subsequently, pairwise correlations of these network components were calculated and then transformed using the Fisher' s Z‐transformation. Therefore, a 12 × 12 matrix was obtained. A two‐tailed two‐sample t‐test was conducted to compare the differences in FNC between patients with CUVP and healthy controls. The results of multiple comparisons were corrected by cluster‐level FWE (P < 0.05). Mean z scores of brain regions with significant FC difference was extracted by using the software tool kit (REST) and was compared across groups by using an SPSS software.

CORRELATION ANALYSIS

A linear regression analysis was performed to explore the relationship between the changes in FC patterns and clinical manifestations such as duration of disease, DHI, CP in patients with CUVP using Pearson correlation analysis.

Results

Clinical Data

All patients showed both chronic dizziness and instability, and these symptoms worsened when turning the head quickly and during movement. The median duration of disease was 10 months (interquartile range 12 months), the average CP value was 46.15% ± 13.26%; the average DHI score was 41.22 ± 5.62; there was no significant correlation between CP value and the duration of disease (P = 0.733), CP and DHI score (P = 0.176), horizontal canal vHIT gains and the duration of disease (P = 0.167), horizontal canal vHIT gains and DHI score (P = 0.176), as well as duration of disease and DHI score (P = 0.791) (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Baseline Information for CUVP Patients and Healthy Controls

| CUVP | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DHI | HCs | |||||||||||||

| ID | Gender | Age | Duration (month) | CP (%) | Gain | Vertigo spells (3 months) | Dizziness/Unsteadiness | DHI‐T | DHI‐P | DHI‐E | DHI‐F | ID | Gender | Age |

| 01 | M | 52 | 12 | 79 | 0.67↓ | ‐ | √ | 36 | 18 | 10 | 8 | 01 | M | 60 |

| 02 | F | 64 | 7 | 41 | 0.88 | ‐ | √ | 34 | 12 | 10 | 12 | 02 | F | 57 |

| 03 | F | 49 | 36 | 100 | 0.67↓ | ‐ | √ | 32 | 16 | 8 | 8 | 03 | F | 49 |

| 04 | F | 38 | 60 | 45 | 1.05 | ‐ | √ | 44 | 18 | 12 | 14 | 04 | M | 52 |

| 05 | F | 17 | 48 | 40 | 1.01 | ‐ | √ | 40 | 12 | 16 | 12 | 05 | F | 28 |

| 06 | M | 42 | 5 | 49 | 0.79 | ‐ | √ | 38 | 10 | 12 | 16 | 06 | F | 40 |

| 07 | F | 40 | 10 | 40 | 0.83 | ‐ | √ | 38 | 14 | 10 | 14 | 07 | F | 39 |

| 08 | M | 42 | 8 | 57 | 1.11 | ‐ | √ | 42 | 10 | 12 | 20 | 08 | M | 50 |

| 09 | F | 61 | 6 | 53 | 0.79 | ‐ | √ | 40 | 20 | 10 | 10 | 09 | F | 68 |

| 10 | M | 52 | 12 | 75 | 0.94 | ‐ | √ | 36 | 12 | 14 | 10 | 10 | F | 56 |

| 11 | F | 48 | 6 | 56 | 0.57↓ | ‐ | √ | 42 | 20 | 12 | 10 | 11 | M | 46 |

| 12 | F | 55 | 72 | 63 | 0.97 | ‐ | √ | 42 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 12 | F | 50 |

| 13 | F | 49 | 10 | 100 | 0.77↓ | ‐ | √ | 52 | 20 | 20 | 12 | 13 | F | 39 |

| 14 | M | 52 | 12 | 73 | 0.79 | ‐ | √ | 48 | 22 | 12 | 14 | 14 | M | 23 |

| 15 | F | 41 | 5 | 40 | 0.99 | ‐ | √ | 42 | 18 | 12 | 12 | 15 | M | 40 |

| 16 | F | 48 | 12 | 100 | 0.62↓ | ‐ | √ | 52 | 18 | 16 | 18 | 16 | F | 41 |

| 17 | F | 65 | 6 | 80 | 0.55↓ | ‐ | √ | 46 | 14 | 20 | 12 | 17 | F | 40 |

| 18 | M | 48 | 8 | 70 | 0.67↓ | ‐ | √ | 38 | 10 | 12 | 16 | 18 | F | 58 |

| 47.90 ± 11.01 | ‐ | 64.50 ± 21.26 | ‐ | ‐ | 35.89 ± 6.70 | 13.00 ± 4.30 | 11.89 ± 4.25 | 11.56 ± 3.54 | 46.44 ± 11.38 | |||||

M = male; F = female; CP = canal paresis; vHIT = video head impulse test; DHI = dizziness handicap inventory; DHI‐T = DHI‐total; DHI‐P = DHI physical subscale; DHI‐E = DHI emotional subscale; DHI‐F = DHI functional subscale.

fMRI Data

RESTING‐STATE NETWORK COMPONENT

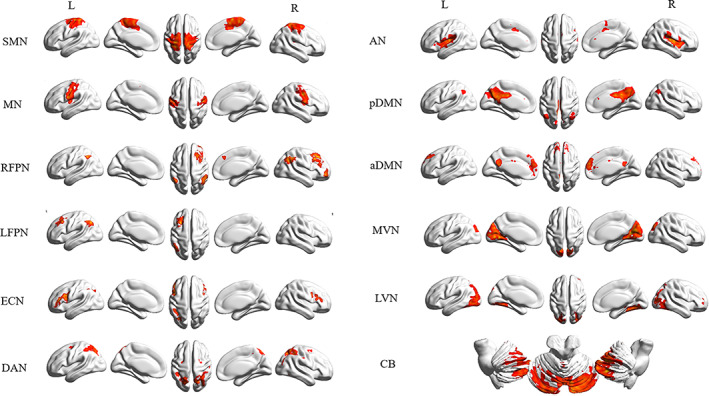

Twelve independent components obtained were shown in Fig. 1. The anterior default mode network (aDMN) mainly included the medial prefrontal cortex and anterior cingulate cortex. The posterior default mode network (pDMN) mainly included posterior cingulate cortex, precuneus, lateral parietal and middle temporal gyrus. The medial visual network (MVN) consisted of the primary visual cortex, including the occipital pole, cuneus, and precuneus. The lateral visual network (LVN) encompassed higher‐order visual processing areas including bilateral occipital cortices, bilateral occipital fusiform gyrus, and parts of the occipitotemporal junction. The auditory network (AN) mainly included bilateral superior temporal gyrus, Helsh gyrus and posterior insular gyrus. The motor network (MN) mainly included bilateral precentral gyrus and supplementary motor area (SMA). The sensorimotor network (SMN) was mainly composed of sensorimotor cortex, SMA, and secondary sensorimotor cortex. The left and right frontoparietal networks (L/RFPN) mainly included dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and posterior parietal cortex. The executive control network (ECN) included dorsal medial prefrontal cortex, bilateral anterior prefrontal cortex and bilateral superior parietal cortex. The dorsal attention network (DAN) included the inferior frontal gyrus, inferior parietal lobule, angular gyrus, and supramarginal gyrus. The cerebellum network (CN) included the bilateral cerebellum.

FIGURE 1.

Twelve independent components were identified using independent component analysis, including anterior default mode network (aDMN), posterior default mode network (pDMN), medial visual network (MVN), lateral visual network (LVN), motor network (MN), sensorimotor network (SMN), left frontoparietal network (LFPN), right frontoparietal network (RFPN), executive control network (ECN), dorsal attention network (DAN), and cerebellum network (CB).

INTRANETWORK FC

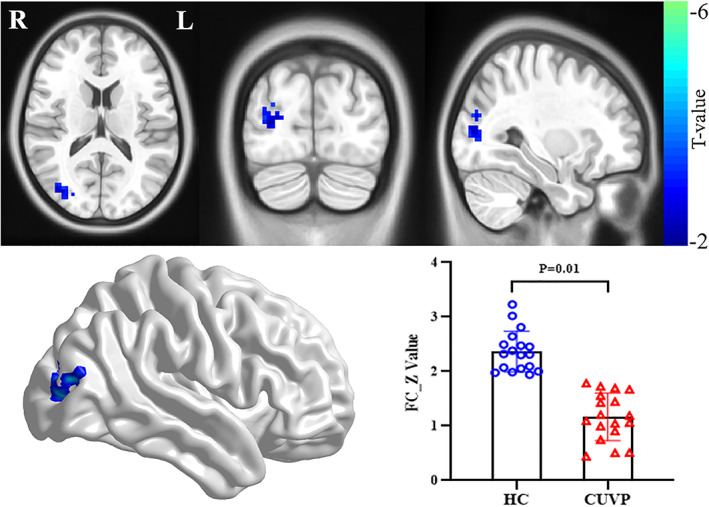

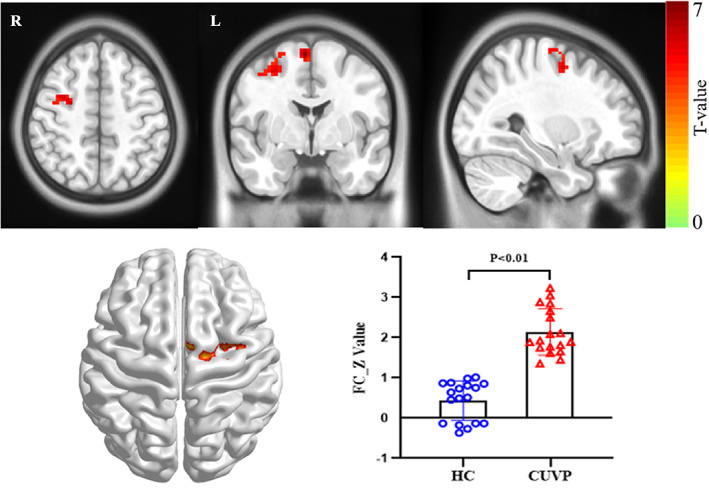

Compared with healthy controls, patients with CUVP showed significantly decreased FC in the right middle occipital gyrus within the LVN (X = 3, Y = −84, Z = 66, cluster size = 88, t = −4.12, Fig. 2) and significantly increased FC in the right SMA within the SMN (X = 6, Y = −3, Z = 66, cluster size = 107, t = 3.67, Fig. 3).

FIGURE 2.

Significant differences in intranetwork functional connectivity in the right middle occipital gyrus within the LVN between patients with CUVP compared with healthy controls.

FIGURE 3.

Significant differences in intranetwork functional connectivity in the supplementary motor area within SMN between patients with CUVP compared with healthy controls.

INTERNETWORK FC

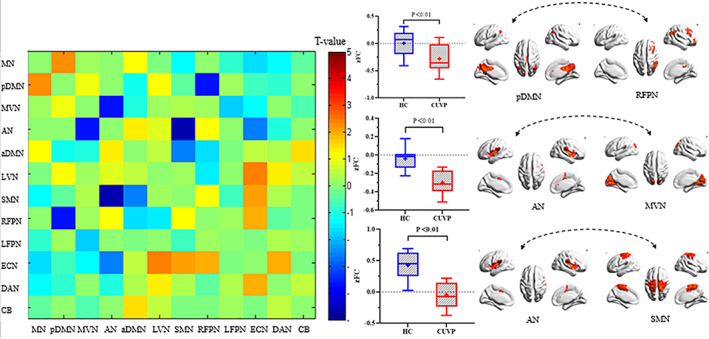

Compared with healthy controls, the FC was significantly decreased between the MVN and AN (P < 0.01, t = −3.64), the RFPN and pDMN (P < 0.01, t = −3.67), as well as between the SMN and AN (P < 0.01, t = −4.66) in patients with CUVP (Fig. 4; Supplementary Figure S1 and S2).

FIGURE 4.

Significant differences in internetwork functional connectivity between patients with CUVP compared with healthy controls.

CORRELATION ANALYSIS

There was a significant negative correlation between the FC of the MVN, AN, and the DHI score in patients with CUVP (r = −0.583), whereas there was no significant correlation between changes in FC of brain networks and CP values in patients with CUVP (P = 0.763).

Discussion

Altered Intranetwork FC in Patients With CUVP

In the present study, intranetwork FC analysis revealed decreased FC in the right middle occipital gyrus within LVN in patients with CUVP. It is well known that vision, vestibular and somatosensory systems work together to perceive our body and its relationship with the environment, which are further integrated and coordinated by the central nervous system to accurately perceive spatial location, ensure clear and stable vision and postural balance during various movements. 12 , 18 The interaction between different senses makes it possible for sensory substitution in patients with unilateral peripheral vestibular dysfunction (UPVD). 12 When one sense is absent, the body will compensate for the lack through substitution of other senses. Many studies have found that when disturbing vision and proprioception, patients with UPVD exhibit greater center‐of‐pressure sway than healthy subjects, indicating that patients with UPVD rely more on vision and somatosensory input to maintain their balance. 19 , 20 zu Eulenburg et al 21 demonstrated increased gray matter volume in visual, motor cortical areas, gracile nucleus, and bilateral somatosensory cortex in patients with VN. A voxel‐based morphometry study of nine patients with vestibular neuritis performed by Hong et al 22 showed that gray matter volume was increased in the lingual gyrus of the occipital lobe in patients. The results of these studies indicated that the functional activities in the visual cortex, somatosensory cortex and subcortical structure were enhanced in patients with VN, which supported the mechanism of sensory substitution. The results of our study revealed decreased FC in the right middle occipital gyrus within LVN in patients with CUVP, suggesting that the dynamic compensation is not complete in these patients, and that a strong sensory substitution mechanism is not initiated, which may lead to chronic dizziness. However, in order to further verify these findings, further studies are needed to investigate the structural changes such as gray matter volume difference between the patients with CUVP and health controls and explore whether changes in FC is related with brain structure changes in patients with CUVP.

In this study, we also found that the FC in the SMA within SMN was enhanced in patients with CUVP. A study has shown that SMA contributes to regulation of posture and control of movement and is an important node in the information flow of postural regulation (cortex‐parieto‐occipital junction‐SMA‐premotor cortex [PMC]‐anterior horn of spinal cord), which plays an important role in high‐level motor control, such as gait adjustment. 23 SMA receives information about the external environment and internal states of the body from the parieto‐occipital junction and receives input from the basal ganglia and cerebellum through the thalamus. After the information is integrated and processed, SMA projects the efferent information to the motor areas, which are then involved in postural regulation and motor control. 23 , 24 The expected postural control can be achieved by activating SMA, which is responsible for motion programming of movements based on visual motion processing. Premotor area (PM)/SMA may forward programs of precise foot–foot movement to the primary motor cortex and then send movement commands via corticospinal tract. The programs of precise movement and postural control are generated in the PMC and SMA. The vestibule, vision, and proprioceptive sensations are integrated in the parieto‐occipital cortex, the bodily information is then transmitted to the PM/SMA, that encodes movement patterns. 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 Therefore, it can be speculated that due to reduced spontaneous activity in the visual cortex in patients with CUVP, information flow into areas such as SMA through the parieto‐occipital cortex is reduced, functions attributed to the SMA including self‐initiation and planning of movements, and feedback calibration are not accurate, so patients with CUVP have to strengthen postural control through behavioral substitution to maintain their balance. However, this may form high‐risk postural control strategies, leading to instability.

Altered Internetwork FC in Patients With CUVP

In this study, the internetwork FC analysis revealed weakened FC between the LVN and AN, as well as between the SMN and AN in patients with CUVP. Studies have shown that AN, VN, and SMN are independent processing systems for auditory, visual, and sensorimotor functions, respectively, that further integrate visual, vestibular information and different spatial frames of reference, therefore, ensuring the accuracy of spatial orientation, forming clear spatial perception. 18 , 27 , 28 In this study, we found that: 1) AN is mainly composed of the temporal lobe and parietal cortex around the lateral fissure, which is mainly involved in auditory information processing and plays a major role in spatial perception and orientation. Studies 29 , 30 have shown that auditory and vestibular information converge in the overlapping areas of the caudal part of the superior temporal sulcus and posterior insula, suggesting that AN highly overlaps with the vestibular cortex and is a multi‐sensory integration cortex. 31 Previous fMRI studies on patients with UPVD during the recovery period showed that the vestibular cortex with enhanced FC was mostly located within AN. 8 , 10 , 11 , 19 , 20 , 21 2) LVN is the visual association cortex and participates in the integration of visual information and other information. 32 3) SMN, which was first identified by Biswal et al, 33 mainly includes the primary motor cortex (Ml), SMA, and PMC and plays an important role in execution and coordination of movement. Previous studies have shown that SMA is an important node in the postural regulation network and is essential for accurate gait control. 23 , 24 , 25 , 33 The temporoparietal cortex includes the posterior parietal cortex and vestibular cortex, which can integrate real‐time signals in the vision, proprioceptive and vestibular sensations, so that the body's environmental information can be always updated and then transmitted to SMA to encode information for body posture control. 25 We speculated that the synergy between visual–auditory‐vestibular‐sensorimotor regions is decreased in patients with CUVP, which in turn affects the coordination and integrity of motion perception, spatial orientation and motor regulation, resulting in chronic dizziness/instability.

In this study, the internetwork FC analysis also revealed decreased FC between pDMN and RFPN in patients with CUVP. 1) DMN was discovered by Raichle et al 34 and is the most important component of the resting‐state brain network and the most widely studied brain network. DMN mainly contains medial prefrontal cortex, posterior cingulate cortex, precuneus, anterior cingulate cortex, bilateral inferior parietal lobule, and medial temporal lobe. 35 Among these brain regions, the medial prefrontal cortex and anterior cingulate cortex belong to aDMN, and the remaining regions, such as posterior anterior cingulate cortex, precuneus, and bilateral angular gyrus belong to pDMN. 2) Frontoparietal network (FPN) is also known as frontoparietal control network or executive attention network and is mainly composed of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and posterior parietal cortex. 36 RFPN is right sided, containing a dorsal pathway including angular gyrus, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, frontal eye field and insula, that participates in cognitive control such as memory, attention, and visual processing 37 and almost any cognitive control tasks, as well as somatosensory perception and pain processing. A study 38 found that FPN is between the DAN and DMN, which is related to the integration of information from these two networks.

A previous study 39 documented mutual antagonism between task negative network (DMN) and task positive network (FPN, DAN), with DMN being positively activated during the resting state and deactivated during the task states, while task positive networks display opposite patterns of activation. It is believed that spontaneously organized brain functional activities exist during states of rest or quiet wakefulness, and these spontaneous brain activities during the resting state may be closely related to human thought, emotion and self‐cognitive processes. Klingner et al 11 performed an fMRI study on patients with AUVP and found that the FC between DMN and multiple other networks, including the somatosensory cortex, auditory/vestibular/insular cortex, motor cortex, occipital cortex, LFPC and RFPC, was reduced. With the restoration of peripheral vestibular function, the FC returns to normal. The author believed that this is a compensatory strategy of body, which can meet the increased demand on task networks to deal with multisensory conflicts, even during a resting state. In this study, reduced FC between pDMN and RFPN was observed in patients with CUVP. This may be the result of the body's long‐term adaptation, with task positive networks being further strengthened to obtain information about the surrounding environment and patients' own spatial position.

DHI was developed by Jacobson and Newman 15 and is widely used to determine the self‐perceived handicap on emotion (E), physical (P), and functional (F) aspects as a consequence of dizziness and unsteadiness. The physical subscale of the DHI assesses the physical factors associated with dizziness/unsteadiness, the functional subscale of the DHI assesses functional consequences of dizziness/unsteadiness, and the emotional subscale of the DHI assesses emotional consequences of dizziness/unsteadiness, such as feelings of depression and anxiety. In this study, the average DHI score for patients with CUVP indicated that they had a moderate level of disability. There were no significant differences between the total and subscale scores (F, E, and P) of the DHI. These results suggest that in addition to chronic vestibular symptoms of varying severity, such as head movement‐ and visually‐induced dizziness, patients with CUVP may often present with varying degrees of anxiety and depression. There was no significant correlation between CP value and the duration of disease, as well as total and subscale scores (F, E, and P) of the DHI. This result is consistent with previous studies showing that there was no correlation between peripheral vestibular function impairment and chronic symptoms. 2 , 5 Residual peripheral vestibular function deficiency cannot be the sole factor for chronicity of clinical symptoms in patients with CUVP. This may be due to the fact that vestibular compensatory mechanisms have not properly restored higher order perceptual functions, leaving patients vulnerable to subjective sensations of dizziness and unsteadiness in motion environments.

In this study, correlation analysis revealed a negative correlation between the FC of the MVN, AN, and the DHI score, but no significant correlation between changes in FC of brain networks and CP values in patients with CUVP, indicating that chronic symptoms following CUVP may be related to incomplete vestibular central compensation, rather than to the degree of peripheral vestibular loss. A previous study 5 also showed that the chronicity of clinical symptoms in patients with CUVP may be related to incomplete vestibular central compensation, psychosocial factors and persistent over‐reliance on visual signals. In this study, due to the feelings of fear and dread caused by the severe symptoms such as dizziness and unsteadiness during the acute phase, all patients actively avoided visual stimuli and did not undergo active vestibular rehabilitation treatment. For such patients, vestibular suppressants may be used, which in turn lead to a decrease in sensitivity to visual stimuli, failure of initiation of strong visual substitution, and poor visual substitution. This may ultimately result in chronic dizziness and unsteadiness. These symptoms are aggravated during turning head quickly and movement. Therefore, we speculate that psychological factors and visual dependence may affect vestibular central compensation and the extent of recovery after vestibular rehabilitation in patients with CUVP, which might be related to the chronicity of dizziness symptoms. However, their relationship needs to be explored in future studies.

Limitations

This study had several limitations. First, this study had a small sample size and data were collected retrospectively from a single center. Second, we choose eyes‐closed condition for fMRI data acquisition in the present study. However different eye state can produce different patterns of brain activity. The differences in FC between eyes‐open and eyes‐closed conditions in patients with CUVP can be explored in the future. Third, central compensation may be different in CUVP patients with different etiologies and disease duration, future multimodal imaging studies may need to explore the alterations in brain structure and function in CUVP patients in order to confirm our findings. Moreover, in this study, we did not perform a comprehensive psychological assessment in patients with CUVP, and did not observe the influence of the psychological factors, such as anxiety and depression, on the clinical outcomes. Further studies with larger sample size are needed to explore the relationship between psychological factors and altered FC by assessing the psychological state of patients with CUVP.

Conclusions

The FC was decreased in the right visual cortex and enhanced in the right sensorimotor network in patients with CUVP. These results document incomplete central vestibular dynamic compensation in patients with CUVP and that visual substitution is poor in these patients who rely more on strengthening body postural control through behavioral substitution. The FC between multiple whole‐brain networks in patients with CUVP were decreased, suggesting that abnormal integration of multisensory information in patients with CUVP may be involved in the occurrence of chronic dizziness and instability. These findings are of importance for understanding vestibular compensation in patients with CUVP.

Conflicts of Interests

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interests.

Supporting information

Figure S1 The functional network connectivity in patients with CUVP.

Figure S2 The functional network connectivity in healthy controls.

Acknowledgment

The study was supported by Aerospace Center Hospital (grant no. YN201802).

Lihong Si and Bin Cui contributed equally to this paper.

References

- 1. Kerber KA. Chronic unilateral vestibular loss. Handb Clin Neurol 2016;137:231‐234. 10.3109/00016489.2016.1172730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lacour M, Helmchen C, Vidal PP. Vestibular compensation: The neuro‐otologist's best friend. J Neurol 2016;263(Suppl 1):S54‐S64. 10.1007/s00415-015-7903-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cousins S, Cutfield NJ, Kaski D, et al. Visual dependency and dizziness after vestibular neuritis. PLoS One 2014;9(9):e105426. 10.1371/journal.pone.0105426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cousins S, Kaski D, Cutfield N, et al. Vestibular perception following acute unilateral vestibular lesions. PLoS One. 2013;8(5):e61862. 10.1371/journal.pone.0061862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cousins S, Kaski D, Cutfield N, et al. Predictors of clinical recovery from vestibular neuritis: A prospective study. Ann Clin Transl Neurol 2017;4(5):340‐346. 10.1002/acn3.386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lopez C, Borel L, Magnan J, Lacour M. Torsional optokinetic nystagmus after unilateral vestibular loss: Asymmetry and compensation. Brain 2005;128(Pt 7):1511‐1524. 10.1093/brain/awh504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Borel L, Harlay F, Magnan J, Chays A, Lacour M. Deficits and recovery of head and trunk orientation and stabilization after unilateral vestibular loss. Brain 2002;125(Pt 4):880‐894. 10.1093/brain/awf085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Helmchen C, Ye Z, Sprenger A, Münte TF. Changes in resting‐state fMRI in vestibular neuritis. Brain Struct Funct 2014;219(6):1889‐1900. 10.1007/s00429-013-0608-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Raiser TM, Flanagin VL, Duering M, van Ombergen A, Ruehl RM, Zu EP. The human corticocortical vestibular network. Neuroimage 2020;223:117362. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2020.117362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Roberts RE, Ahmad H, Patel M, et al. An fMRI study of visuo‐vestibular interactions following vestibular neuritis. Neuroimage Clin 2018;20:1010‐1017. 10.1016/j.nicl.2018.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Klingner CM, Volk GF, Brodoehl S, Witte OW, Guntinas‐Lichius O. Disrupted functional connectivity of the default mode network due to acute vestibular deficit. Neuroimage Clin. 2014;6:109‐114. 10.1016/j.nicl.2014.08.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Eysel‐Gosepath K, McCrum C, Epro G, Brüggemann GP, Karamanidis K. Visual and proprioceptive contributions to postural control of upright stance in unilateral vestibulopathy. Somatosens Mot Res 2016;33(2):72‐78. 10.1080/08990220.2016.1178635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Perlbarg V, Marrelec G. Contribution of exploratory methods to the investigation of extended large‐scale brain networks in functional MRI: Methodologies, results, and challenges. Int J Biomed Imaging 2008;2008:218519. 10.1155/2008/218519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Schmäl F, Lübben B, Weiberg K, Stoll W. The minimal ice water caloric test compared with established vestibular caloric test procedures. J Vestib Res 2005;15(4):215‐224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jacobson GP, Newman CW. The development of the dizziness handicap inventory. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1990;116(4):424‐427. 10.1001/archotol.1990.01870040046011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chao‐Gan Y, Yu‐Feng Z. DPARSF: A MATLAB toolbox for "pipeline" data analysis of resting‐state fMRI. Front Syst Neurosci 2010;4:13. 10.3389/fnsys.2010.00013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Himberg J, Hyvärinen A, Esposito F. Validating the independent components of neuroimaging time series via clustering and visualization. Neuroimage 2004;22(3):1214‐1222. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bronstein AM. Multisensory integration in balance control. Handb Clin Neurol 2016;137:57‐66. 10.1016/B978-0-444-63437-5.00004-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Alessandrini M, Pagani M, Napolitano B, et al. Early and phasic cortical metabolic changes in vestibular neuritis onset. PLoS One. 2013;8(3):e57596. 10.1371/journal.pone.0057596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bense S, Bartenstein P, Lochmann M, Schlindwein P, Brandt T, Dieterich M. Metabolic changes in vestibular and visual cortices in acute vestibular neuritis. Ann Neurol 2004;56(5):624‐630. 10.1002/ana.20244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. zu Eulenburg P, Stoeter P, Dieterich M. Voxel‐based morphometry depicts central compensation after vestibular neuritis. Ann Neurol 2010;68(2):241‐249. 10.1002/ana.22063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hong SK, Kim JH, Kim HJ, Lee HJ. Changes in the gray matter volume during compensation after vestibular neuritis: A longitudinal VBM study. Restor Neurol Neurosci 2014;32(5):663‐673. 10.3233/RNN-140405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Nakajima T, Hosaka R, Tsuda I, Tanji J, Mushiake H. Two‐dimensional representation of action and arm‐use sequences in the presupplementary and supplementary motor areas. J Neurosci 2013;33(39):15533‐15544. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0855-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Shima K, Tanji J. Both supplementary and presupplementary motor areas are crucial for the temporal organization of multiple movements. J Neurophysiol 1998;80(6):3247‐3260. 10.1152/jn.1998.80.6.3247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Roland PE, Larsen B, Lassen NA, Skinhøj E. Supplementary motor area and other cortical areas in organization of voluntary movements in man. J Neurophysiol 1980;43(1):118‐136. 10.1152/jn.1980.43.1.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mihara M, Miyai I, Hatakenaka M, Kubota K, Sakoda S. Role of the prefrontal cortex in human balance control. Neuroimage 2008;43(2):329‐336. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Roberts RE, Ahmad H, Arshad Q, et al. Functional neuroimaging of visuo‐vestibular interaction. Brain Struct Funct 2017;222(5):2329‐2343. 10.1007/s00429-016-1344-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Beauchamp MS, Lee KE, Argall BD, Martin A. Integration of auditory and visual information about objects in superior temporal sulcus. Neuron 2004;41(5):809‐823. 10.1016/s0896-6273(04)00070-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lopez C, Blanke O, Mast FW. The human vestibular cortex revealed by coordinate‐based activation likelihood estimation meta‐analysis. Neuroscience 2012;212:159‐179. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2012.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Andersen RA. Multimodal integration for the representation of space in the posterior parietal cortex. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 1997;352(1360):1421‐1428. 10.1098/rstb.1997.0128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Oh SY, Boegle R, Ertl M, Stephan T, Dieterich M. Multisensory vestibular, vestibular‐auditory, and auditory network effects revealed by parametric sound pressure stimulation. Neuroimage 2018;176:354‐363. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2018.04.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Smith SM, Fox PT, Miller KL, et al. Correspondence of the brain's functional architecture during activation and rest. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2009;106(31):13040‐13045. 10.1073/pnas.0905267106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Biswal B, Zerrin Yetkin F, Haughton VM, Hyde JS. Functional connectivity in the motor cortex of resting human brain using echo‐planar MRI. Magn Reson Med 1995;34(4):537–541. 10.1002/mrm.1910340409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Gusnard DA, Akbudak E, Shulman GL, Raichle ME. Medial prefrontal cortex and self‐referential mental activity: Relation to a default mode of brain function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2001;98(7):4259‐4264. 10.1073/pnas.071043098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Buckner RL, Andrews‐Hanna JR, Schacter DL. The brain's default network: Anatomy, function, and relevance to disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2008;1124:1‐38. 10.1196/annals.1440.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Barrós‐Loscertales A, Costumero V, Rosell‐Negre P, Fuentes‐Claramonte P, Llopis‐Llacer JJ, Bustamante JC. Motivational factors modulate left frontoparietal network during cognitive control in cocaine addiction. Addict Biol 2020;25(4):e12820. 10.1111/adb.12820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Costumero V, Rosell‐Negre P, Bustamante JC, et al. Left frontoparietal network activity is modulated by drug stimuli in cocaine addiction. Brain Imaging Behav 2018;12(5):1259‐1270. 10.1007/s11682-017-9799-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Vincent JL, Kahn I, Snyder AZ, Raichle ME, Buckner RL. Evidence for a frontoparietal control system revealed by intrinsic functional connectivity. J Neurophysiol 2008;100(6):3328‐3342. 10.1152/jn.90355.2008 Erratum in: J Neurophysiol. 2011;105(3):1427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Raichle ME, Snyder AZ. A default mode of brain function: A brief history of an evolving idea. Neuroimage 2007;37(4):1083‐1090; discussion 1097‐9. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.02.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1 The functional network connectivity in patients with CUVP.

Figure S2 The functional network connectivity in healthy controls.