Abstract

Introduction

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) is a leading cause of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. The majority of VTE events are hospital‐associated. In 2008, the Epidemiologic International Day for the Evaluation of Patients at Risk for Venous Thromboembolism in the Acute Hospital Care Setting (ENDORSE) multinational cross‐sectional study reported that only approximately 40% of medical patients at risk of VTE received adequate thromboprophylaxis.

Methods

In our systematic review and meta‐analysis, we aimed at providing updated figures concerning the use of thromboprophylaxis globally. We focused on: (a) the frequency of patients with an indication to thromboprophylaxis according with individual models; (b) the use of adequate thromboprophylaxis; and (c) reported contraindications to thromboprophylaxis. Observational nonrandomized studies or surveys focusing on medically ill patients were considered eligible.

Results

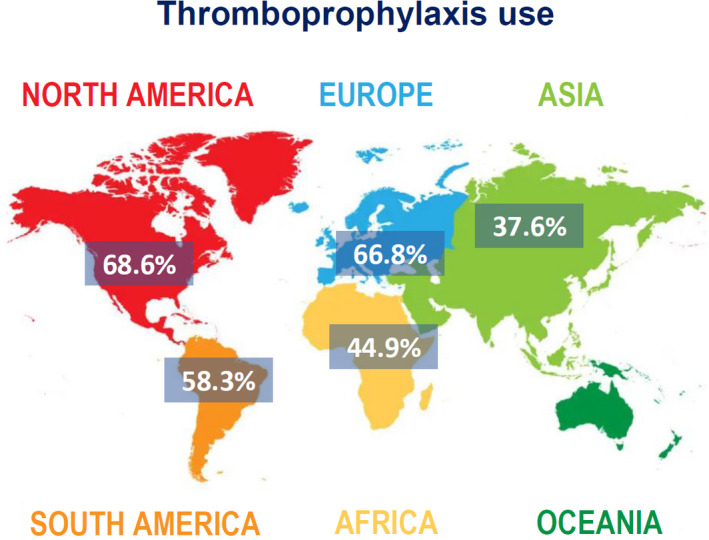

After screening, we included 27 studies from 20 countries for a total of 137 288 patients. Overall, 50.5% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 41.9–59.1, I 2 99%) of patients had an indication to thromboprophylaxis: of these, 54.5% (95% CI: 46.2–62.6, I 2 99%) received adequate thromboprophylaxis. The use of adequate thromboprophylaxis was 66.8% in Europe (95% CI: 50.7–81.1, I 2 98%), 44.9% in Africa (95% CI: 31.8–58.4, I 2 96%), 37.6% in Asia (95% CI: 25.7–50.3, I 2 97%), 58.3% in South America (95% CI: 31.1–83.1, I 2 99%), and 68.6% in North America (95% CI: 64.9–72.6, I 2 96%). No major differences in adequate thromboprophylaxis use were found across risk assessment models. Bleeding, thrombocytopenia, and renal/hepatic failure were the most frequently reported contraindications to thromboprophylaxis.

Conclusions

The use of anticoagulants for VTE prevention has been proven effective and safe, but thromboprophylaxis prescriptions are still unsatisfactory among hospitalized medically ill patients around the globe with marked geographical differences.

Keywords: epidemiology, thromboprophylaxis, thrombosis, venous thromboembolism, World Thrombosis Day

Essentials.

In 2008, ENDORSE reported only 40% of medical patients receiving adequate thromboprophylaxis.

We did a meta‐analysis of 27 studies (N = 137 288) to provide updated figures on a global scale.

Despite improvement, its use is still unsatisfactory (55%) with marked geographical differences.

The World Thrombosis Day is instrumental to increase VTE awareness and reduce disease burden.

1. INTRODUCTION

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) is a leading cause of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. 1 , 2 VTE impairs patient prognosis and causes patient discomfort, longer hospitalizations, and higher health care costs. 3 , 4 , 5 The majority of VTE events are hospital‐associated, occurring during hospitalization or within 90 days of hospital discharge 6 : with more than 20 million hospital admissions in the European Union and around 35 million in the United States per year, 7 , 8 there is an urgent need to tackle this issue on a global scale. 5 , 9

Several risk assessment models, scores, and classifiers have been developed to identify high‐risk medical patients who would benefit from in‐hospital and postdischarge thromboprophylaxis on the basis of a risk‐benefit principle. 5 This means avoiding exposing patients with a low risk to unnecessary anticoagulation and consequent bleeding risk, but, and conversely, promoting the use of thromboprophylaxis among patients estimated to have a substantial VTE risk. 10 , 11

In several countries, national health care strategies and a systematic approach to prevention of hospital‐associated VTE have been integrated into routine care, resulting in a reduction of deaths and costs. 9 However, systematic strategies for VTE prevention are often not uniformly implemented, even within individual countries. The World Health Organization, in cooperation with the World Thrombosis Day and numerous other stakeholders, is currently enacting initiatives to reduce hospital‐associated VTE as a part of a global program to reduce preventable mortality from noncommunicable diseases. 12 A key aspect of this process is the evaluation and implementation of currently available assessment measures and therapies.

In 2008, the Epidemiologic International Day for the Evaluation of Patients at Risk for Venous Thromboembolism in the Acute Hospital Care Setting (ENDORSE) cross‐sectional study with around 70 000 patients from 32 countries showed that there is a substantial proportion of high‐risk hospitalized patients, but a low prevalent use of appropriate thromboprophylaxis. 13 In this systematic review of the literature and meta‐analysis, we examined the evolution of these figures among acutely ill medical patients in more recent years.

2. METHODS

We conducted a systematic review of the literature focusing on the use of risk assessment models and pharmacological thromboprophylaxis in acutely medically ill patients during hospitalization. We screened relevant publications including trials, cohort studies, case‐control studies, and surveys in PubMed and Web of Science that appeared over the past decade (2010–) using predefined search terms. Search criteria included "thromboprophylaxis," "prophylaxis," and “venous thromboembolism,” also "RAM" and "risk assessment method"; a complete overview of the search criteria has been attached (Appendix S1). Papers were not limited to the English language. The first literature search was on the January 15, 2021, and was updated thereafter. Studies retrieved by a predefined literature search strategy were selected based on titles and abstracts. All parts of the systematic review were performed separately in a standardized manner by two reviewers (G.F. and E.M.).

Studies were considered eligible if they fulfilled the following criteria: (a) observational nonrandomized studies or surveys focusing on medically ill patients (e.g., those who were hospitalized because of a medical, not surgical, condition); and (b) reporting the prevalent use of risk assessment models (and presenting the number of patients for each risk class) and of thromboprophylaxis. A description of each model is presented in the Supplementary Material. In‐hospital thromboprophylaxis was defined as the use of pharmacological agents at a prophylactic dose and having been defined as “adequate” in the individual studies based on currently accepted definitions.

We focused on the following study outcomes: (a) patients with an indication for thromboprophylaxis according with individual risk assessment models or classifiers; (b) use of thromboprophylaxis; and (c) reported reasons for not giving thromboprophylaxis to patients with another indication.

The data were extracted using a charting table, which was developed to record key information from sources relevant to the review questions. The findings were descriptively presented, with tables and figures to support the data, when appropriate. The following data were extracted: first author, year of publication, study design, number of study participants, sex, characteristics of the study population, and rate of the outcomes. Search results were screened independently by two reviewers for the relevance of titles/abstracts and full texts of the studies fulfilling the inclusion criteria. Disagreements were solved by a third reviewer.

We performed subgroup analyses investigating separately the frequency of patients classified at high risk and the rate of thromboprophylaxis used in each cohort by focusing on individual models, provided that the number of observations was deemed adequate for a subgroup analysis. We also analyzed the use of adequate thromboprophylaxis among high‐risk patients by geographical differences. We calculated weighed and unweighed rates of the outcomes of interest applying a random‐effect model (95% confidence interval [CI]). We assessed (statistical) heterogeneity of exposure effects by calculating the I 2 statistic, which summarizes the amount of variance among studies beyond chance. Heterogeneity was defined as low (I 2 < 25%), moderate (I 2 = 25%–75%), or high (I 2 > 75%). The presence of publication bias was evaluated by visually inspecting funnel plots. We did not perform a formal quality assessment of the included studies (i.e., with the Newcastle‐Ottawa score) because we anticipated that the vast majority of the studies would have not had our research question as one of the predefined outcomes of interest: as a consequence, many items of available scales would have not applied. We have provided a summary of the study design for each study.

3. RESULTS

Our literature search identified 2191 records in PubMed and 675 in Web of Science. The process of study selection is summarized in Figure S1. Eventually, we included 27 studies in our analysis for a total of 137 288 patients: of those, 15 were multicentric and six were conducted prospectively. Size, setting, quality assessment, and general characteristics of the included studies are summarized in Table 1. Reflecting their reported use in the studies selected by our systematic review, the following risk assessment models or classifiers were included for analysis: Padua Prediction score, Geneva score, Caprini score, and the American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) criteria. The baseline characteristics of patients included in the individual studies are summarized in Table 2, including the prevalence of VTE risk factors that would mandate a primary thromboprophylaxis, such as reduced mobility, cancer, cardiopulmonary diseases, prior VTE, and acute infection. The Padua Prediction score (n = 10, 35%; n = 71 649) and the scheme proposed by the ACCP guidelines for VTE prophylaxis (n = 10, 35%; n = 4914) were the most frequently used models in the literature. Other risk assessment tools included the Caprini (n = 7, 25%; n = 61 258) and the Geneva (n = 1, 3.5%; n = 1478) scores (Table 3). None of the eligible studies focused on the IMPROVE risk assessment model.

TABLE 1.

Size, setting, and general characteristics of the included studies

| First author | Centers, n | Study Design | Age (Median) | Men (%) | Country/Region | Exclusion Criteria | Number of Patients |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grant, 2018 25 | 52 | n.s. | 65 | 45 | United States | <48 h hospitalization, ICU | 44 775 |

| Flanders, 2014 26 | 35 | Retrospective | 66 | 43 | United States | <18 years, pregnancy, surgery during hospitalization, ICU, palliative care, VTE <6 months | 31 260 |

| de Bastos, 2013 27 | 1 | Cohort | 65 | 43 | Brazil | <18 years, ongoing anticoagulation, DVT | 27 221 (surgical and OB/GYN patients included) |

| Gafter‐Gvili, 2020 28 | 1 | Retrospective | 67 | 51 | Israel | <48 h hospitalization, ongoing anticoagulation, surgery, active bleeding, hemoglobin <8 g/dl, platelet count <50 000/ml | 18 890 |

| Mahlab‐Guri, 2020 29 | 1 | Retrospective | 68 | 47 | Israel | ≤18 years, ongoing anticoagulation, VTE | 3000 |

| Łukaszuk, 2016 30 | 1 | Retrospective | 66 | 56 | Poland | <18 years, <24 h hospitalization, ICU | 2011 |

| Nieto, 2014 31 | 78 | Retrospective | 78 | 51 | Spain | <40 years, <96 h hospitalization, admission for diagnostic procedures, VTE, surgery | 1623 |

| Spirk, 2015 32 | 8 | Prospective | 65 | 53 | Switzerland | <18 years, ongoing anticoagulation, unable to provide an informed consent | 1478 |

| Rossetto, 2013 33 | 1 | n.s. | 82 | 61 | Italy | Ongoing anticoagulation, contraindication to anticoagulation | 803 |

| Zwicker, 2014 34 | 5 | Prospective | 56 | 56 | United States | Ongoing anticoagulation | 775 |

| Vazquez, 2014 35 | 28 | Cross‐sectional | 65 | 53 | Argentina | <21 years, ongoing anticoagulation, pregnancy, postpartum, DVT, ICU | 729 |

| Kingue, 2014 36 | 14 | Cross‐sectional | 61 | 49 | Sub‐Saharan Africa | <40 years | 567 |

| Vincentelli, 2016 37 | 23 | Cohort | 72 | n.a. | Italy | ≤18 years, insufficient medical data, VTE, the presence of caval filters, contraindications for pharmacological prophylaxis, and recent (≤60 days) major trauma or major surgery | 520 |

| Sharif‐Kashani, 2012 38 | 1 | Prospective | 52 | 62 | Iran | <18 years, <72 h hospitalization, ongoing anticoagulation, ICU | 481 |

| Tazi‐Mezalek, 2018 39 | 7 | Cross‐sectional | 60 | n.a. | Morocco | <40 years, pregnancy, postpartum, VTE | 467 |

| Farhat, 2018 40 | 1 | Cross‐sectional | n.a. | n.a. | Brazil | <18 years, <24 h hospitalization, ongoing anticoagulation, pregnancy, postpartum, unavailable information | 369 |

| Moorehead, 2017 41 | 1 | Retrospective | 54 | n.a. | United States | INR >1.3, <72 h hospitalization, ongoing anticoagulation, VTE, active bleeding, liver transplantation, active renal or hematologic malignancy, coagulation deficiency | 300 |

| Bâ, 2011 42 | 12 | Cross‐sectional | 62 | 54 | Senegal | <40 years, VTE | 278 |

| Panju, 2011 43 | 2 | Retrospective | n.a. | n.a. | Canada | <18 years, ongoing anticoagulation | 233 |

| Guermaz, 2015 44 | >1 | Observational | 61 | n.a. | Algeria | <40 years, no acute illness | 229 |

| Gharaibeh, 2015 45 | 1 | Cross‐sectional | n.a. | 52 | Jordan | <18 years, <24 h hospitalization, ongoing antithrombotic treatment | 220 |

| Wessels, 2012 46 | 29 | Prospective | 53 | 56 | South Africa | <18 years, ongoing anticoagulation, no written informed consent | 219 |

| Ayalew, 2018 47 | 1 | Cross‐sectional | 40–45 | 48 | Ethiopia | Ongoing anticoagulation | 206 |

| Lanthier, 2010 48 | 1 | Cross‐sectional | 71 | 46 | Canada | <18 years, ongoing anticoagulation | 183 |

| Shah, 2020 49 | 2 | Prospective | 65 | 59 | Cyprus | <18 years, SVT, contraindication to anticoagulation, DVT in the prior 3 months | 180 |

| Nkoke, 2020 50 | 2 | Prospective | 54 | 48 | Cameroon | <72 h hospitalization, ongoing anticoagulation, VTE | 147 |

| Manoucheri, 2015 51 | 1 | Cross sectional | n.a. | n.a. | Iran | <16 years, <72 h hospitalization, ongoing anticoagulation | 124 |

Abbreviations: DVT, deep vein thrombosis; ICU, intensive care unit; INR, international normalized ratio; n.a., not available or not applicable; OB/GYN, obstetrics and gynecology; SVT, superficial vein thrombosis; VTE, venous thromboembolism.

TABLE 2.

Baseline characteristics of patients from the included studies

| First Author | Reduced Mobility, n (%) | Cancer, n (%) | Respiratory or Heart Failure, n (%) | Prior VTE, n (%) | Obesity, n (%) | Recent Stroke or Myocardial Infarction, n (%) | Acute Infection, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gafter‐Gvili, 2020 28 | 2381 (12) | 3460 (18) | 934 (5) | 150 (1) | 3602 (19) | n.a. | 2887 (14) |

| Mahlab‐Guri, 2020 29 | 831 (28) | 223 (7) | 562 (19) | 56 (2) | 387 (13) | 194 (6) | 951 (32) |

| Nkoke, 2020 50 | 45 (31) | 4 (3) | 19 (13) | 1 (1) | 12 (8) | 9 (6) | n.a. |

| Shah, 2020 49 | 180 (100) | n.s. | 8 (4) | n.a. | 38 (21) | 8 (4) | n.a. |

| Ayalew, 2018 47 | 44 (21) | 18 (9) | 26 (13) | 1 (1) | n.a. | 22 (11) | 106 (52) |

| Farhat, 2018 40 | 214 (58) | 25 (7) | 57 (15) | 1 (1) | 38 (10) | 12 (3) | 87 (24) |

| Moorehead, 2017 41 | n.s. | 45 (15) | 89 (29) | 14 (5) | 82 (27) | 13 (4) | n.a. |

| Łukaszuk, 2016 30 | n.a. | 551 (27) | 42 (2) | 13 (1) | 349 (17) | n.a. | 780 (39) |

| Vincentelli, 2016 37 | 157 (30) | 40 (8) | 160 (30) | n.a. | n.a. | 18 (3) | 46 (9) |

| Gharaibeh, 2015 45 | 84 (surgical patients included) | n.s. | n.a. | n.a. | 92 (42) | n.a. | n.a. |

| Guermaz, 2015 44 | 61 (27) | 7 (3) | 14 (6) | 5 (2) | 40 (18) | 19 (8) | 64 (28) |

| Spirk, 2015 32 | 403/962 (high risk patients) (42) | 351 (36) | 513 (53) | 120 (13) | 180 (19) | 56 (4) | 403 (42) |

| Flanders, 2014 26 | n.a. | 4334 (21) | n.a. | 1139 (5) | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| Kingue, 2014 36 | 132 (23) | 42 (7) | n.a. | n.a. | 59 (10) | 145 (26) | 135 (24) |

| Nieto, 2014 31 | 853 (53) | 93 (6) | 282 (17) | n.a. | n.a. | 68 (4) | 279 (17) |

| Vazquez, 2014 35 | 330 (45) | 159 (22) | 85 (12) | 21 (3) | 330 (45) | n.a. | n.a. |

| Zwicker, 2014 34 | 54 (10) | 528 (100) | 49 (9) | 58 (11) | 128 (24) | 5 (1) | 165 (31) |

| de Bastos, 2013 27 | n.a. | 1096 (11) | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 1099 (11) | n.a. |

| Rossetto, 2013 33 | 266/296 (high risk patients) (85) | 65 (24) | 120 (31) | 23 (9) | n.a. | 7 (3) | 122 (32) |

| Sharif‐Kashani, 2012 38 | 128 (27) | 70 (15) | 13 (3) | 4 (1) | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| Lanthier, 2010 48 | 71 (39) | 29 (16) | n.a. | 8 (4) | 44 (24) | n.a. | n.a. |

Abbreviations: n.a., not available or not applicable; VTE, venous thromboembolism.

TABLE 3.

List of the risk assessment models and thromboprophylaxis used in each study

| First Author | Risk Assessment Method | Cutoff | Number of Patients | TP Indicated Solely Based on Score | TP Indicated Based on Score in Patients Without Contraindications or Exclusion Criteria | TP iven |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grant, 2018 25 | Padua | ≥4 | 44 775 | 12 226 | 10 422 | 7955 |

| Flanders, 2014 26 | Caprini | ≥3 | 31 260 | n.a. | 20 794 | 14 563 |

| de Bastos, 2013 27 | Caprini | High risk | 27 221 (surgical and OB/GYN patients included) | n.a. | 5227 | 1420 |

| Gafter‐Gvili, 2020 28 | Padua | ≥4 | 18 890 | n.a. | 4370 | 1573 |

| Mahlab‐Guri, 2020 29 | Padua | ≥4 | 3000 | 728 | 618 | 136 |

| Łukaszuk, 2016 30 | Caprini | ≥5 | 2011 | n.a. | 888 | 309 |

| Padua | ≥4 | 2011 | n.a. | 428 | 167 | |

| Nieto, 2014 31 | ACCP 2008 | 1623 | 930 | 771 | 645 | |

| Spirk, 2015 32 | Geneva risk score | ≥3 | 1478 | 962 | 898 | 572 |

| Rossetto, 2013 33 | Padua | ≥4 | 803 | n.a. | 296 | 262 |

| Zwicker, 2014 34 | Padua | ≥4 | 775 | n.a. | 377 | 297 |

| Vazquez, 2014 35 | ACCP 2008 | 729 | 729 | 620 | 385 | |

| Kingue S, 2014 36 | ACCP 2004 | 567 | n.a. | 353 | 128 | |

| Vincentelli, 2016 37 | Padua | n.a. | 520 | n.a. | 165 | 100 |

| Sharif‐Kashani, 2012 38 | ACCP 2008 | 481 | n.a. | 221 | 63 | |

| Tazi‐ Mezalek, 2018 39 | ACCP 2008 | 467 | 250 | 250 | 126 | |

| Farhat, 2018 40 | Padua | ≥4 | 369 | 154 | 140 | 91 |

| Moorehead, 2017 41 | Padua | ≥4 | 300 | n.a. | 95 | 66 |

| Bâ, 2011 42 | ACCP 2004 | 278 | 152 | 136 | 46 | |

| Panju, 2011 43 | ACCP | 233 | 233 | 170 | 91 | |

| Guermaz, 2015 44 | ACCP | 229 | 172 | 152 | 103 | |

| Gharaibeh, 2015 45 | Caprini | ≥3 | 220 | n.a. | 127 | 82 |

| Wessels, 2012 46 | Caprini | ≥3 | 219 | n.a. | 154 | 119 |

| Ayalew, 2018 47 | Padua | ≥4 | 206 | n.a. | 78 | 21 |

| Lanthier, 2010 48 | ACCP | 183 | n.a. | 88 | 67 | |

| Shah, 2020 49 | Caprini | ≥ 5 | 180 | 140 | 140 | 82 |

| Nkoke, 2020 50 | Caprini | High‐risk | 147 | 139 | 118 | 26 |

| Manoucheri, 2015 51 | ACCP | 124 | n.a. | 114 | 48 |

Abbreviations: ACCP, American College of Chest Physicians; n.a., not available or not applicable; OB/GYN, obstetrics and gynecology, TP, thromboprophylaxis.

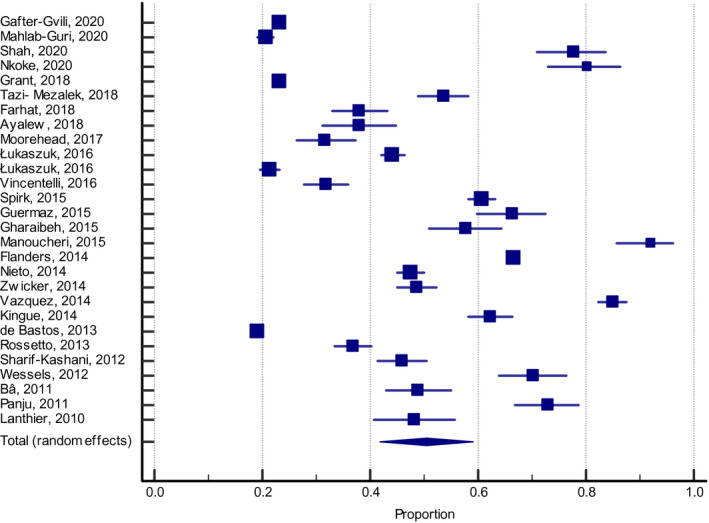

Overall, 50.5% (95% CI: 41.9–59.1, I 2 99%) of hospitalized medically ill patients were classified as having a high VTE risk according to a risk assessment tool or to the ACCP criteria (Figure 1). This percentage was 30.4% (95% CI: 27.4–33.5, I 2 97%) for the Padua Prediction score, 59.5% (95% CI: 34.9–81.8, I 2 99%) for the Caprini score, and 63.1% (95% CI: 52.3–73.4, I 2 98%) for the ACCP criteria.

FIGURE 1.

Patients classified at a high risk of VTE according to risk assessment models or ACCP criteria (all studies). ACCP, American College of Chest Physicians; VTE, venous thromboembolism

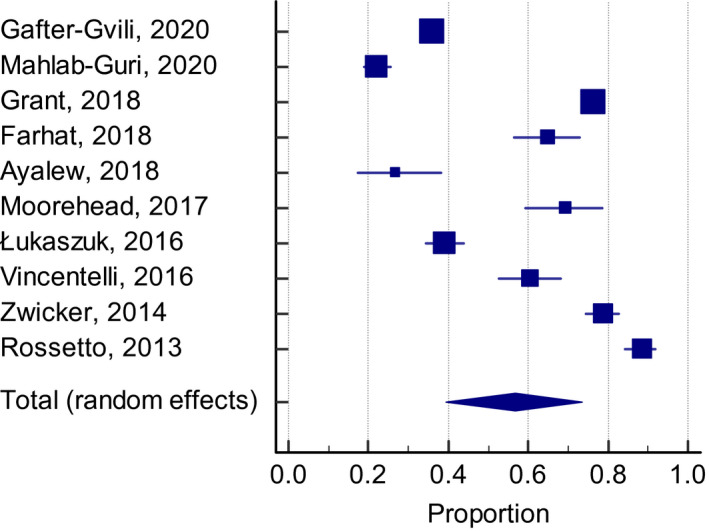

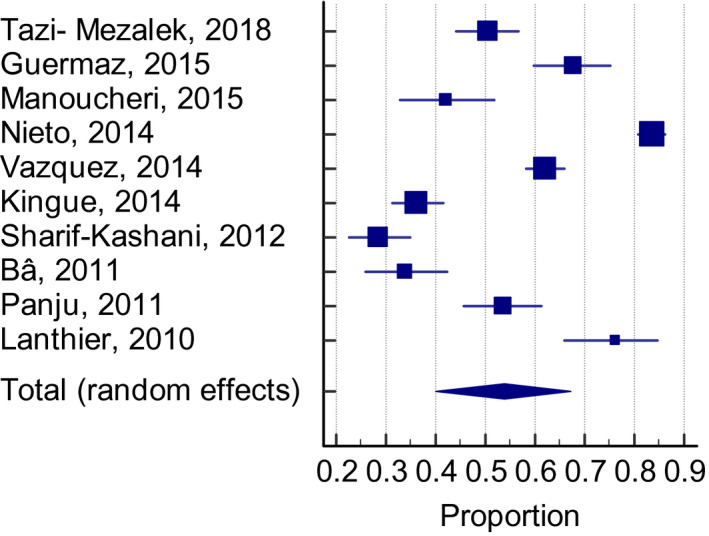

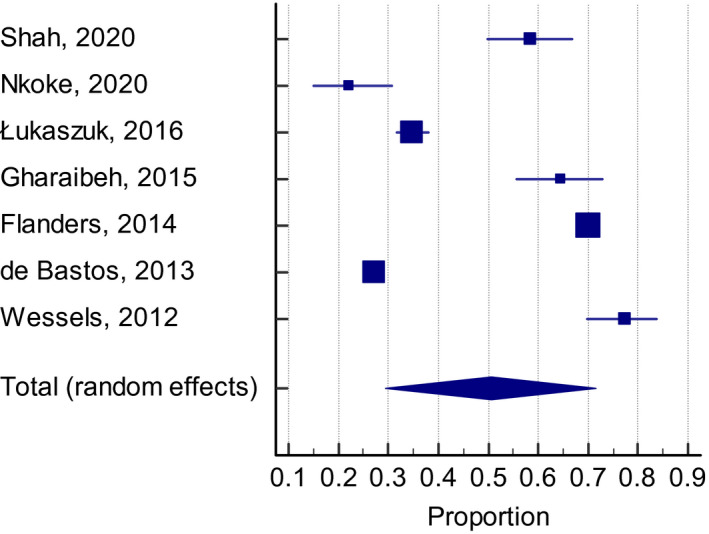

Overall, 54.5% (95% CI: 46.2–62.6, I 2 99%) of patients who were classified to be at a high VTE risk received adequate thromboprophylaxis, defined as the use of pharmacological agents at a prophylactic dose, and had been determined in the individual studies based on currently accepted definitions. The frequency of thromboprophylaxis use was similar across groups: 56.9% (95% CI: 39.6–73.4, I 2 99%) for the Padua Prediction score (Figure 2), 53.8% (95% CI: 40.1–67.2, I 2 98%) for the ACCP criteria (Figure 3), and 50.5% (95% CI: 29.4–71.5, I 2 99%) for the Caprini score (Figure 4).

FIGURE 2.

Adequate thromboprophylaxis use among high‐risk patients according with the Padua Prediction score

FIGURE 3.

Adequate thromboprophylaxis use among high‐risk patients according with the ACCP criteria. ACCP, American College of Chest Physicians

FIGURE 4.

Adequate thromboprophylaxis use among high‐risk patients according with the Caprini score

The use of adequate thromboprophylaxis was 66.8% in Europe (95% CI: 50.7–81.1, I 2 98%), 44.9% in Africa (95% CI: 31.8–58.4, I 2 96%), 37.6% in Asia (95% CI: 25.7–50.3, I 2 97%), in South America 58.3% (95% CI: 31.1–83.1, I 2 99%), whereas the percentage was higher in North America with 68.6% (95% CI: 64.9–72.6, I 2 96%) of patients (Figure 5).

FIGURE 5.

Geographical differences in thromboprophylaxis use

A total of 14 studies reported the frequency of relative and absolute contraindications to thromboprophylaxis among hospitalized medically ill patients. In five studies, this figure was specified for the total of patients with otherwise a formal indication for its use. In nine studies, it was reported for the total of included patients. A summary of the study characteristics and reasons for not giving thromboprophylaxis is shown in Table 4. Active bleeding was considered a contraindication in all reviewed papers. Following active bleeding, the most prevalent contraindication was thrombocytopenia with cutoff levels varying across studies from <50 000 × 109/L (n = 5), 75 000 109/L (n = 1), to 100 000 109/L (n = 2). In one study no threshold was defined. A bleeding disorder was reported in seven of the 11 papers as a contraindication. In five studies, patients presenting with renal failure did not receive thromboprophylaxis: the exact definition of renal failure was specified only in two studies.

TABLE 4.

Contraindications to pharmacological thromboprophylaxis as listed in each study

| Study | Contraindicated/Total Patients, n | Bleeding, n (%) | Definition of Bleeding | Thrombocytopenia, n (%) | Definition of Thrombocytopenia (109/l) | Renal Failure, n (%) | Definition of Renal Failure | Other Reasons, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Guermaz, 2015 44 | 38/229 | n.a. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. |

| Panju, 2011 43 | 63/233 | n.a. | Hemoglobin <100 g/L, suspected or active bleeding, recent gastrointestinal bleeding | n.s. | <100 000 oder HIT n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. |

| Flanders, 2014 26 | 6398/31 260 | n.a. | Gastrointestinal or genitourinary bleeding within the last 6 months; high‐bleeding‐risk procedure, intracranial hemorrhage within the past year | n.s. | <50 000 oder HIT | n.s. | n.s. | Coagulopathy, hypersensitivity to unfractionated or low molecular weight heparin; severe head, spinal cord, or extremity trauma within the 24 h before admission; or intracranial lesion, neoplasm (n.s.) |

| Sharif‐Kashani, 2012 38 | 23/481 | 6 (27) | Active gastrointestinal bleeding, massive hemoptysis | n.s. | n.s. | 14 (60%) | n.s. | Hepatic dysfunction, anemia with hematocrit < 30% 17 (73) |

| Kingue, 2014 36 | 254/567 | 28 (12) | Active bleeding, intracranial hemorrhage | 21 (8) | n.s. | 88 (15.5%) | n.s. | Hepatic dysfunction, known bleeding disorder, aspirin on admission, NSAID on admission, active gastro‐duodenal ulcer 205 (80) |

| Ayalew, 2018 47 | 50/206 | 15 (30) | Active bleeding, severe trauma to head or spinal cord with hemorrhage in past 4 weeks | 25 (50) | <50 000 or coagulopathy | Hepatic dysfunction 10 (20) | ||

| Zwicker, 2014 34 | 247/775 | 92 (37) | Active bleeding, history of hemorrhage | 163 (66) | <50 000 or HIT | Patient refusal 12 (5) | ||

| Bâ, 2011 42 | 22/278 | 8 (36) | Active bleeding, intracranial hemorrhage | n.s. | n.s. | Hepatic dysfunction, unknown bleeding syndrome, active duodenal ulcer 14 (64) | ||

| Vazquez, 2014 35 | 129/729 | n.a. | Active bleeding, recent (in the past 7 days) major bleeding | n.s. | <50 000 or coagulopathy | n.s. | Creatinine clearance <30 mL/min | Active peptic ulcer, severe liver failure (n.s.) |

| Study | Contraindicated/High‐risk Patients With Indication, n | Bleeding, n (%) | Definition of Bleeding | Thrombocytopenia, n (%) | Definition of Thrombocytopenia (G/l) | Renal Failure, n (%) | Definition of Renal Failure | Other Reasons, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mahlab‐Guri, 2020 29 | 110/728 | 50 (45) | Recent bleeding, Intracranial hemorrhage in the past year | 39 (35) | <75 000 or HIT | Hepatic dysfunction, active peptic disease, coagulopathy 21 (20) | ||

| Grant, 2018 25 | 1804/12 226 | n.a. | Active bleeding, intracranial hemorrhage within the past year; other hemorrhage within the past 6 months | n.s. | <50 000 or coagulopathy | Hemophilia, or other significant bleeding disorder (n.s.) | ||

| Nieto, 2014 31 | 159/930 | n.a. | Active bleeding, recent intracranial hemorrhage; Active gastrointestinal ulcer | n.s. | n.s. | History of intracranial or aortic aneurysm (n.s.) | ||

| Nkoke, 2020 50 | 21/139 | 12 (57) | Active bleeding, intracranial hemorrhage | 1 (8) | <100 000 | 7 (5%) |

Creatinine clearance <30 ml/min |

Hepatic impairment 1 (0.7%) |

| Farhat, 2018 40 | 14/154 | n.a. | Active bleeding; ongoing anticoagulation; uncontrolled arterial hypertension (n.s.) | n.s. | Cutoff not defined | ‐ |

Abbreviations: CI, contraindicated; HIT, heparin‐induced thrombocytopenia; n.a., not available or not applicable; NSAID, nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drug.

4. DISCUSSION

The results of this systematic review and meta‐analysis of global studies indicate that, in contrast to guideline recommendations, the frequency of thromboprophylaxis prescriptions is still unsatisfactory among hospitalized medically ill patients. In 2008, a global multinational cross‐sectional survey, the ENDORSE study, including close to 70 000 hospitalized patients from 32 countries, of whom approximately 38 000 were categorized as medical inpatients, showed that 42% of medical inpatients were classified at high risk of VTE defined by the ACCP criteria and only 40% of this subgroup received adequate thromboprophylaxis. 13 Our systematic review and meta‐analysis of studies published since then, which included more than 135 000 patients from 20 countries, showed that the percentage of adequately thromboprophylaxed patients lags far behind what one would expect, being currently around 54% of those with an indication and after the exclusion of a variable number of patients on therapeutic anticoagulation before hospital admission.

This apparent overall increase of in‐hospital thromboprophylaxis over the past decade should be principally read as positive and could have resulted from a number of different reasons, including a general increased awareness of the need for VTE prevention. In comparison with the ENDORSE study, a fair improvement in the rate of the use of adequate thromboprophylaxis is recognizable primarily in Africa among all continents, improving from approximately 27%–29% in the ENDORSE study to 45% in this analysis. Moreover, we found that the use of adequate thromboprophylaxis still markedly varied across geographic regions, ranging from 38% in Asia to 69% in North America. This may be due to several factors, including national guidelines, VTE awareness, 14 health care standards, variable VTE prevalence among regions, 2 and reimbursement system. 15 In contrast, we could not find major deviations from model to model, indicating that thromboprophylaxis was given to a similar percentage of patients irrespective of the model that had been used.

Our results also showed that the most frequently reported reasons not to give thromboprophylaxis were the presence of active bleeding or a high risk of bleeding, including thrombocytopenia (with several different cutoffs), and renal or liver dysfunction. In many cases, however, the risk factors for bleeding may also represent predisposing factors for VTE, such as thrombocytopenia in cancer patients, recent trauma, or organ failure. This indicates that alternative preventive measures, such as mechanical thromboprophylaxis, the use of which for patients with contraindications to pharmacological thromboprophylaxis was sparsely mentioned, or novel and possibly safer pharmacological agents, 16 are urgently needed to reduce the individual risk of VTE but not that of bleeding.

The global VTE burden can be substantially reduced with the implementation of validated risk assessment models in clinical practice, with tailoring individual thromboprophylaxis, and with control measures to assess whether thromboprophylaxis is adequately prescribed. 17 , 18 , 19 The Padua Prediction score and the ACCP guidelines were the most frequently adopted scores in surveys included in our systematic review, followed by the Caprini and Geneva scores. We noted that applying different risk assessment models to a similar cohort of patients resulted in a different proportion of patients being classified as high risk. 20 Indeed, their performance largely varies, as recently demonstrated in an ad hoc analysis, 20 and their adoption should depend not only on general factors (again, their performance), but also on other aspects, including the target population, general acceptance and collection of specific clinical items for their calculation, and on the expected VTE prevalence in the target population. Indeed, the present study did not aim to study the performance of the different risk assessment methods, but to focus on the implementation on any strategy to risk stratify medical patients and on its consequences. In fact, some of the included models are not adequately validated for medical patients, such as the Caprini score. In contrast, one of the most frequently validated risk assessment models, the IMPROVE, 17 , 21 , 22 is probably too “young” to have been introduced in clinical practice and subsequently described in surveys or in population studies.

Raising awareness among health care professionals proved to be a successful method for improving the adequacy of venous thromboprophylaxis. 23 , 24 The World Thrombosis Day on October 13 is organized on a yearly basis, with events through the year as well, to raise awareness and improve the care of patients with thrombosis with the participation of hundreds of organizations around the globe. It is an educational initiative, with the aim of reducing the disease burden caused by VTE.

The present systematic review and meta‐analysis has a number of limitations related to the observational nature of the studies reviewed and their own limitations. Based on our search strategy, some important studies possibly were not included because not all relevant papers may have been listed in PubMed or Web of Science. 52 The studies in our systematic review were a combination of prospective, cross‐sectional, and retrospective registries. The risk assessment method used for the revaluation of VTE risk was also diverse with the use of three different risk assessment models plus the ACCP criteria. Furthermore, the cutoff for being classified as high risk for VTE was not homogeneously defined in different studies, and the exclusion criteria were also heterogeneously defined. The high clinical and statistical heterogeneity observed across studies, finally, may prevent an obvious interpretation of these results.

In conclusion, hospital‐associated VTE is known to be a mostly preventable cause of morbidity and mortality in medical hospitalized patients. The use of anticoagulants for VTE prevention has been proven effective and safe, but thromboprophylaxis prescriptions are still unsatisfactory among hospitalized medically ill patients around the globe with marked geographical differences.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Dr. Barco has received honoraria from Boston Scientific, Concept Medical, INARI, Bayer, LeoPharma; institutional grants from Sanofi, Bard, Bentley, Concept Medical, Boston Scientific, Concept Medical; and support for congress participation and travel from Daiichi Sankyo and Bayer. Dr. Áinle: research grants (paid to university): Bayer, Daiichi‐Sankyo, Actelion, Leo Pharma. Dr. Ageno has received research support from Bayer and honoraria from Aspen, Bayer, BMS/Pfizer, Leo Pharma, Norgine, Sanofi, Daiichi Sankyo. Dr. Castellucci has received honoraria from Bayer, BMS‐Pfizer Alliance, The Academy, LEO Pharma, Sanofi, and Servier; she holds a Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada National New Investigator Award, and a Tier 2 research Chair in Thrombosis and Anticoagulation Safety from the University of Ottawa. The other authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Gabor Forgo: data collection, data analysis and interpretation, drafting the article. Maria Cecilia Guillermo Esposito: data collection, revision of the article, provided critical feedback and interpretation of the results, final approval. Walter Ageno, Lana A. Castellucci, Gabriela Cesarman‐Maus, Henry Ddungu, Erich Vinicius De Paula, Mert Dumantepe, Maria Cecilia Guillermo Esposito, Stavros V. Konstantinides, Nils Kucher, Claire McLintock, Fionnuala Ní Áinle, Alex C. Spyropoulos, Tetsumei Urano, Beverley J. Hunt: interpretation of the results, revision of the article, provided critical feedback, final approval. Stefano Barco: concept and supervision of the study, drafting the article, interpretation of the results, final approval. An informed consent is not needed for the conduction of systematic reviews and meta‐analyses.

Supporting information

Appendix S1

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Open Access Funding provided by Universitat Zurich.

Forgo G, Micieli E, Ageno W, et al. An update on the global use of risk assessment models and thromboprophylaxis in hospitalized patients with medical illnesses from the World Thrombosis Day steering committee: Systematic review and meta‐analysis. J Thromb Haemost. 2022;20:409–421. doi: 10.1111/jth.15607

Manuscript Handled by: David Lillicrap

Final decision: David Lillicrap, 18 November 2021

REFERENCES

- 1. Wendelboe AM, Raskob GE. Global burden of thrombosis: epidemiologic aspects. Circ Res. 2016;118(9):1340‐1347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Barco S, Valerio L, Gallo A, et al. Global reporting of pulmonary embolism‐related deaths in the World Health Organization mortality database: vital registration data from 123 countries. Res Pract Thromb Haemost. 2021;5(5):e12520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Raskob GE, Spyropoulos AC, Cohen AT, et al. Association between asymptomatic proximal deep vein thrombosis and mortality in acutely Ill medical patients. J Am Heart Assoc. 2021;10(5):e019459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Barco S, Woersching AL, Spyropoulos AC, Piovella F, Mahan CE. European Union‐28: an annualised cost‐of‐illness model for venous thromboembolism. Thromb Haemost. 2016;115(4):800‐808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Pandor A, Tonkins M, Goodacre S, et al. Risk assessment models for venous thromboembolism in hospitalised adult patients: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2021;11(7):e045672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. MacDougall K, Spyropoulos AC. New paradigms of extended thromboprophylaxis in medically Ill patients. J Clin Med. 2020;9(4):1002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Statista . Total number of hospital admissions in the U.S. from 1946 to 2018 . https://www.statista.com/statistics/459718/total‐hospital‐admission‐number‐in‐the‐us/. Accessed July 2, 2020.

- 8. Gateway EHI Number of all hospital discharges. 2020, september 6. Available at: https://gateway.euro.who.int/en/indicators/hfa_535‐6011‐number‐of‐all‐hospital‐discharges/

- 9. Hunt BJ. Preventing hospital associated venous thromboembolism. BMJ. 2019;365:l4239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Darzi AJ, Karam SG, Charide R, et al. Prognostic factors for VTE and bleeding in hospitalized medical patients: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Blood. 2020;135(20):1788‐1810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Stuck AK, Spirk D, Schaudt J, Kucher N. Risk assessment models for venous thromboembolism in acutely ill medical patients. A systematic review. Thromb Haemost. 2017;117(4):801‐808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Dugani S, Gaziano TA. 25 by 25: achieving global reduction in cardiovascular mortality. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2016;18(1):10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cohen AT, Tapson VF, Bergmann J‐F, et al. Venous thromboembolism risk and prophylaxis in the acute hospital care setting (ENDORSE study): a multinational cross‐sectional study. Lancet. 2008;371(9610):387‐394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wendelboe AM, McCumber M, Hylek EM, Buller H, Weitz JI, Raskob G. Global public awareness of venous thromboembolism. J Thromb Haemost. 2015;13(8):1365‐1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mahan CE, Barco S, Spyropoulos AC. Cost‐of‐illness model for venous thromboembolism. Thromb Res. 2016;145:130‐132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mavromanoli AC, Barco S, Konstantinides SV. Antithrombotics and new interventions for venous thromboembolism: exploring possibilities beyond factor IIa and factor Xa inhibition. Res Pract Thromb Haemost. 2021;5(4). 10.1002/rth2.12509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mahan CE, Liu Y, Turpie AG, et al. External validation of a risk assessment model for venous thromboembolism in the hospitalised acutely‐ill medical patient (VTE‐VALOURR). Thromb Haemost. 2014;112(4):692‐699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Rosenberg D, Eichorn A, Alarcon M, McCullagh L, McGinn T, Spyropoulos AC. External validation of the risk assessment model of the international medical prevention registry on venous thromboembolism (IMPROVE) for medical patients in a tertiary health system. J Am Heart Assoc. 2014;3(6):e001152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Germini F, Agnelli G, Fedele M, et al. Padua prediction score or clinical judgment for decision making on antithrombotic prophylaxis: a quasi‐randomized controlled trial. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2016;42(3):336‐339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Horner D, Goodacre S, Davis S, Burton N, Hunt BJ. Which is the best model to assess risk for venous thromboembolism in hospitalised patients? BMJ. 2021;373:n1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Spyropoulos AC, Cohen SL, Gianos E, et al. Validation of the IMPROVE‐DD risk assessment model for venous thromboembolism among hospitalized patients with COVID‐19. Res Pract Thromb Haemost. 2021;5(2):296‐300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Goldin M, Lin SK, Kohn N, et al. External validation of the IMPROVE‐DD risk assessment model for venous thromboembolism among inpatients with COVID‐19. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2021;52(4):1032‐1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sharif‐Kashani B, Raeissi S, Bikdeli B, et al. Sticker reminders improve thromboprophylaxis appropriateness in hospitalized patients. Thromb Res. 2010;126(3):211‐216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Butkievich LE, Stacy ZA, Daly MW, Huey WY, Taylor CT. Impact of a student‐supported pharmacy assessment program on venous thromboembolism prophylaxis rates in hospitalized patients. Am J Pharm Educ. 2010;74(6):105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Grant PJ, Conlon A, Chopra V, Flanders SA. Use of venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in hospitalized patients. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(8):1122‐1124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Flanders SA, Greene MT, Grant P, et al. Hospital performance for pharmacologic venous thromboembolism prophylaxis and rate of venous thromboembolism: a cohort study. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(10):1577‐1584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. de Bastos M, Barreto SM, Caiafa JS, Bogutchi T, Rezende SM. Assessment of characteristics associated with pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis use in hospitalized patients: a cohort study of 10,016 patients. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2013;24(7):691‐697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Gafter‐Gvili A, Drozdinsky G, Zusman O, Kushnir S, Leibovici L. Venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in acute medically ill patients: a retrospective cohort study. Am J Med. 2020;133(12):1444‐1452 e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Mahlab‐Guri K, Otman MS, Replianski N, Rosenberg‐Bezalel S, Rabinovich I, Sthoeger Z. Venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in patients hospitalized in medical wards: a real life experience. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020;99(7):e19127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lukaszuk RF, Plens K, Undas A. Real‐life use of thromboprophylaxis in patients hospitalized for pulmonary disorders: a single‐center retrospective study. Adv Clin Exp Med. 2018;27(2):237‐243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Nieto JA, Cámara T, Camacho I. Venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in acutely ill hospitalized medical patients. A retrospective multicenter study. Eur J Intern Med. 2014;25(8):717‐723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Spirk D, Nendaz M, Aujesky D, et al. Predictors of thromboprophylaxis in hospitalised medical patients. Explicit ASsessment of Thromboembolic RIsk and Prophylaxis for Medical PATients in SwitzErland (ESTIMATE). Thromb Haemost. 2015;113(5):1127‐1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Rossetto V, Barbar S, Vedovetto V, Milan M, Prandoni P. Physicians' compliance with the Padua prediction score for preventing venous thromboembolism among hospitalized medical patients. J Thromb Haemost. 2013;11(7):1428‐1430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Zwicker JI, Rojan A, Campigotto F, et al. Pattern of frequent but nontargeted pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis for hospitalized patients with cancer at academic medical centers: a prospective, cross‐sectional, multicenter study. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(17):1792‐1796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Vazquez F, Watman R, Tabares A, et al. Risk of venous thromboembolic disease and adequacy of prophylaxis in hospitalized patients in Argentina: a multicentric cross‐sectional study. Thromb J. 2014;12:15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kingue S, Bakilo L, Ze Minkande J, et al. Epidemiological African day for evaluation of patients at risk of venous thrombosis in acute hospital care settings. Cardiovasc J Afr. 2014;25(4):159‐164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Vincentelli GM, Monti M, Pirro MR, et al. Perception of thromboembolism risk: differences between the departments of internal medicine and emergency medicine. Keio J Med. 2016;65(2):39‐43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Sharif‐Kashani B, Shahabi P, Raeissi S, et al. AssessMent of ProphylAxis for VenouS ThromboembolIsm in hospitalized patients: the MASIH study. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 2012;18(5):462‐468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Tazi Mezalek Z, Nejjari C, Essadouni L, et al. Evaluation and management of thromboprophylaxis in Moroccan hospitals at national level: the Avail‐MoNa study. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2018;46(1):113‐119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Farhat F, Gregorio HCT, de Carvalho RDP. Evaluation of deep vein thrombosis prophylaxis in a general hospital. J Vasc Bras. 2018;17(3):184‐192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Moorehead KJ, Jeffres MN, Mueller SW. A retrospective cohort analysis of pharmacologic VTE prophylaxis and Padua prediction score in hospitalized patients with chronic liver disease. J Pharm Pract. 2017;30(1):58‐63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Bâ SA, Badiane SB, Diop SN, et al. A cross‐sectional evaluation of venous thromboembolism risk and use of venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in hospitalized patients in Senegal. Arch Cardiovasc Dis. 2011;104(10):493‐501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Panju M, Raso D, Patel A, Panju A, Ginsberg J. Evaluation of the use of venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in hospitalised medical patients. J R Coll Physicians Edinb. 2011;41(4):304‐308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Guermaz R, Belhamidi S, Amarni A. The PROMET study: prophylaxis for venous thromboembolic disease in at‐risk patients hospitalized in Algeria. J Mal Vasc. 2015;40(4):240‐247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Gharaibeh L, Albsoul‐Younes A, Younes N. Evaluation of venous thromboembolism prophylaxis after the introduction of an institutional guideline: extent of application and implementation of its recommendations. J Vasc Nurs. 2015;33(2):72‐78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Wessels P, Riback WJ. DVT prophylaxis in relation to patient risk profiling ‐ TUNE‐IN study. S Afr Med J. 2012;102(2):85‐89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ayalew MB, Horsa BA, Zeleke MT. Appropriateness of pharmacologic prophylaxis against deep vein thrombosis in medical wards of an Ethiopian referral hospital. Int J Vasc Med. 2018;2018:8176898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Lanthier L, Béchard D, Viens D, Touchette M. Evaluation of thromboprophylaxis in patients hospitalized in a tertiary care center: an applicable model of clinical practice evaluation. Revision of 320 cases. J Mal Vasc. 2011;36(1):3‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Shah SS, Abdi A, Özcem B, Basgut B. The rational use of thromboprophylaxis therapy in hospitalized patients and the perspectives of health care providers in Northern Cyprus. PLoS One. 2020;15(7):e0235495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Nkoke C, Tchinde Ngueping MJ, Atemkeng F, Teuwafeu D, Boombhi J, Menanga A. Incidence of venous thromboembolism, risk factors and prophylaxis in hospitalized patients in the South West region of Cameroon. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2020;16:317‐324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Manoucheri R, Fallahi MJ. Adherence to venous thromboprophylaxis guidelines for medical and surgical inpatients of teaching hospitals, Shiraz‐Iran. Tanaffos. 2015;14(1):17‐26. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Martinez R, Carrizo C, Cuadro R, et al. Insufficient adherence to the prevention of venous thromboembolic disease in Uruguayan hospitals. A serious health problem. Rev Urug Med Int. 2020;5(3):4‐13. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1