Abstract

Herein, we report the rich morphological and conformational versatility of a biologically active peptide (PEP‐1), which follows diverse self‐assembly pathways to form up to six distinct nanostructures and up to four different secondary structures through subtle modulation in pH, concentration and temperature. PEP‐1 forms twisted β‐sheet secondary structures and nanofibers at pH 7.4, which transform into fractal‐like structures with strong β‐sheet conformations at pH 13.0 or short disorganized elliptical aggregates at pH 5.5. Upon dilution at pH 7.4, the nanofibers with twisted β‐sheet secondary structural elements convert into nanoparticles with random coil conformations. Interestingly, these two self‐assembled states at pH 7.4 and room temperature are kinetically controlled and undergo a further transformation into thermodynamically stable states upon thermal annealing: whereas the twisted β‐sheet structures and corresponding nanofibers transform into 2D sheets with well‐defined β‐sheet domains, the nanoparticles with random coil structures convert into short nanorods with α‐helix conformations. Notably, PEP‐1 also showed high biocompatibility, low hemolytic activity and marked antibacterial activity, rendering our system a promising candidate for multiple bio‐applications.

Keywords: amphiphilic systems, self-assembly, nanostructures, peptides, secondary structures

We describe the nanostructural and conformational versatility of the biologically active peptide PEP‐1, which self‐assembles into up to six different aggregate morphologies and forms up to four different secondary structures in a controlled manner depending on pH, concentration, and temperature.

Introduction

Spontaneous self‐assembly of (macro)molecular entities is omnipresent in living systems, which not only plays a critical role in corporal functions but also regulates the formation of a wide variety of dynamic supramolecular structures over different length scales. [1] In this regard, peptides represent prime candidates because of their versatile self‐assembly behaviour and multifaceted applications as advanced materials in fields such as drug‐delivery, tissue engineering, antimicrobial coating and bioinspired nanotechnology (hybrid materials for optoelectronics, nanocatalysis, biosensing etc.) among others. [2] Additionally, peptides exhibit various advantageous facets such as high biocompatibility, biodegradability, adaptable biofunctionalization, inherent biological origin, structural tunability, ease of synthesis in cost‐effective methods and high sensitivity towards environmental conditions. [3] The unique self‐assembly behavior of peptides along with their structural variety of nanoarchitectures (such as micelles, vesicles, fibrils, nanosheets, ribbons or nanotubes) and secondary structures (such as β‐sheets, α‐helices or coiled coils) [4] make them privileged building blocks in supramolecular chemistry. The subtle interplay between intermolecular non‐covalent interactions, including π‐π stacking, hydrogen bonding (H‐bonding), hydrophobic, van der Waals and electrostatic interactions, [5] as well as environmental conditions (such as pH, temperature, concentration, ionic strength etc.) play an important role in controlling the morphology and dimensions of peptide self‐assembled nanostructures. [6] Understanding such programmable self‐assembly is key to tune not only the materials properties but also the effective communication of nanomaterials with biological systems. [7]

Peptide building blocks have been widely investigated with regards to their secondary structures and nanoscale morphologies, which can be typically controlled by external stimuli and/or changing the environmental conditions. [6] Much less attention, however, has been devoted to understand the kinetic vs. thermodynamic aspects of peptide self‐assembly, particularly in the context of pathway complexity. [8] In this regard, a handful of recent reports have shown that certain peptides can form kinetically vs. thermodynamically controlled secondary structural elements (i.e. β‐sheet/random coil) depending on careful selection of the experimental conditions, typically resulting in one‐dimensional assemblies of different length. [9] However, despite their exceptional self‐assembly versatility, examples of peptides that can form multiple nanostructures as well as secondary structural elements in a controlled fashion are rare.

In this article, we demonstrate the unique nanostructural and conformational versatility of a biologically active peptide, which is able to self‐assemble into up to six distinct aggregate morphologies and form up to four different secondary structures in a controlled fashion depending on pH, concentration and temperature. To this end, we have designed an amphiphilic octapeptide, PEP‐1 (Scheme S1; Figures S1 and S2) that contains hydrophobic (Phe, Ala, Leu) as well as hydrophilic, pH sensitive (Asn, Lys, Asp) amino acids. PEP‐1 is indeed a modified version (double mutant) of a naturally occurring β‐strand peptide fragment (residue: 30–37) of a β‐sheet lectin protein, Galectin‐1, which is available in bovine spleen. [10] The peptide sequence has slightly been mutated to make this naturally occurring peptide more amphiphilic in nature. [11] Both the Leu (residue no. 34) and the Gly (residue no. 35) motifs have been replaced by Ala in order to achieve a suitable hydrophobic/hydrophilic balance.

PEP‐1 self‐assembles into pH‐responsive hydrogels and undergoes various pathway‐dependent nano‐ as well as secondary‐ structural transformations depending on the pH, concentration and temperature (Scheme 1). Furthermore, PEP‐1 also exhibits excellent biocompatibility, low hemolytic activity and notable antimicrobial activity towards both Gram‐positive and Gram‐negative bacteria, rendering our system a promising candidate for various bio‐applications. [12]

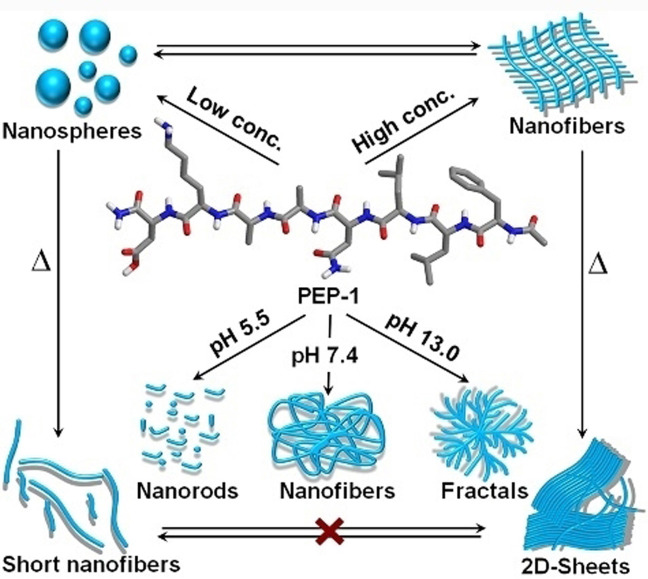

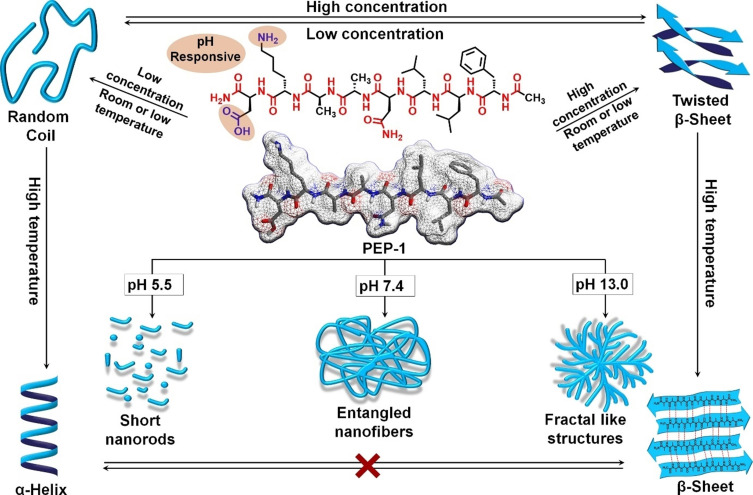

Scheme 1.

Molecular structure of PEP‐1 and schematic representation of its morphological and secondary structural transformations.

Results and Discussion

pH‐Dependent Self‐Assembly Behaviour

The presence of pH‐sensitive amino acid residues makes PEP‐1 a plausible candidate to create pH‐responsive assemblies in aqueous media. At sufficiently high concentrations (C=5×10−3 M), PEP‐1 forms stable transparent hydrogels in phosphate buffer saline (PBS) at pH 7.4 (Figure S3), whereas no hydrogelation occurs at acidic or basic pH. The investigation of the mechanical properties of the PEP‐1 hydrogel at pH 7.4 by rheometry revealed a higher value for storage modulus (G′) compared to the loss modulus (G′′), confirming the gel‐phase. The crossover point (i.e., yield stress) of the hydrogel was estimated to be 4.0 Pa indicating a weak gelation (Figure S4). Furthermore, the gel‐to‐sol transition (T gel) was examined by differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) experiments, which disclosed an endothermic peak at ≈64 °C with ΔH=1.9 J g−1 suggesting the disruption of the gel phase (Figure S5).

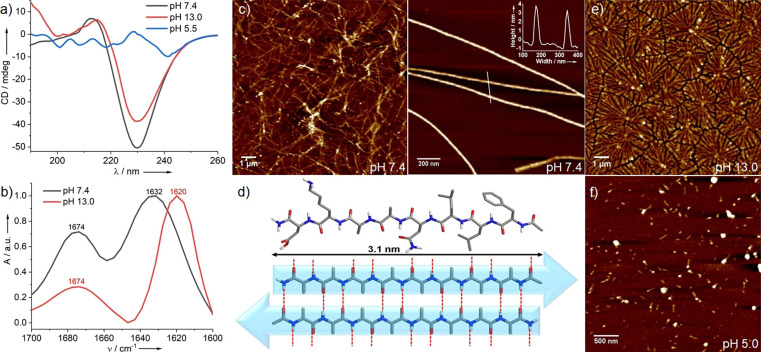

Subsequently, we investigated the pH‐dependent self‐assembly behavior of PEP‐1 under more diluted conditions through combined UV/Vis, fluorescence, FT‐IR and CD experiments. Note that no contribution from linear dichroism was observed in any of the CD studies (vide infra). Initial UV/Vis and emission studies at 5×10−4 M under neutral pH suggest that synergistic aromatic interactions between the phenylalanine residues (Figure S6a,b)[ 5c , 5d , 6c ] and intermolecular H‐bonding interactions between the peptide groups (Figure S6c) contribute to stabilize the assemblies of PEP‐1. Complementary CD experiments under identical conditions disclose a strong negative band at around 230 nm (Figure 1 a) that is a characteristic signature of twisted antiparallel β‐sheet rich structures. [13] This secondary structure is further supported by FT‐IR studies: two intense peaks at 1632 and 1674 cm−1 are observed in the amide‐I region, indicating intermolecular antiparallel β‐sheet arrangement (Figure 1 b).[ 6c , 6d ] Additional proof of the existence of β‐sheet structures is provided by Thioflavin T (ThT) fluorescence assay, where the emission intensity of the mixture PEP‐1/ThT is considerably higher than that of the free ThT (Figure S7).[ 6c , 6d ] To gain insights into the aggregate morphology formed by PEP‐1 at neutral pH, atomic force microscopy (AFM) studies on mica were conducted. As shown in Figure 1 c, entangled nanofibrillar structures with a regular height of 3.2±0.2 nm and lengths of several micrometers are observed. In some regions, isolated, well‐defined fibers can be identified (Figure 1 c right). The height of the single nanofibers matches the molecular length (3.1 nm) determined from the energy‐minimized structure of PEP‐1 (Figure 1 d top), which allowed us to propose a plausible molecular orientation during the self‐assembly process (Figure 1 d bottom and Figure S8). The prevalence of such elongated nanostructures (nanofibers) in solution was further demonstrated by angular‐dependent dynamic light scattering (AD‐DLS), revealing an anisotropic distribution (Figure S9).

Figure 1.

pH‐dependent CD (a) and FT‐IR spectra (b) of PEP‐1; c) AFM image of entangled nanofibers (left); isolated fibers with height profile in the inset (right) at pH 7.4; d) energy‐minimized structure of PEP‐1 (MM2 calculations using Chem3D 20.1) (top) and schematic representation of the formation of anti‐parallel β‐sheet conformations (bottom); AFM images at pH 13.0 (e) and 5.5 (f). [C=5×10−4 M].

Notably, increasing the pH of the system to 13.0 leads to an almost identical CD spectrum to that obtained at pH 7.4, albeit with a slightly lower intensity (Figure 1 a). These results indicate that the β‐sheet rich secondary structures formed at pH 7.4 are preserved upon increasing the pH to 13.0. The formation of anti‐parallel β‐sheet structures was further proven by the characteristic peaks at 1620 and 1674 cm−1 in FT‐IR spectroscopy (Figure 1 b). Interestingly, AFM imaging of PEP‐1 at pH 13.0 demonstrates the formation of fractal‐like structures (Figure 1 e and Figure S10) with heights around 4.5±0.2 nm and widths of ≈200–300 nm, demonstrating that PEP‐1 forms distinct nanostructures at pH 7.4 and 13.0, although the secondary structure is similar. Possibly, lateral association of β‐sheet elements along with substrate and dewetting effects facilitate the formation of the fractal‐like morphologies on mica. On the other hand, decreasing the pH value to 5.5 leads to the disruption of the β‐sheet structures, as evident by the depletion of the CD signal under these conditions (Figure 1 a). AFM reveals small elliptical or nanorod‐like structures (Figure 1 f) that are in good agreement with the destabilization of the PEP‐1 assembly at pH 5.5 (Figure 1 a). These results can be explained by the decreased solubility of PEP‐1 at pH 5.5 due to electrostatic repulsions among positively charged ammonium ions (from Lys+), which hamper not only the molecular orientations during self‐assembly, but also long‐range supramolecular polymerization.[ 6c , 6d , 14 ]

Concentration‐Dependent Self‐Assembly Behaviour

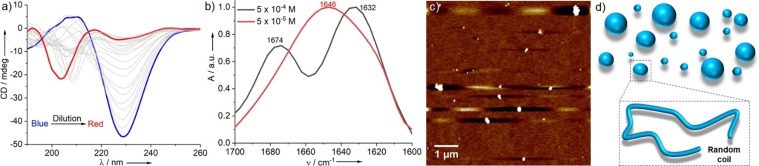

In addition to the pH dependency, we also examined whether PEP‐1 would undergo changes in the morphology and secondary structure upon varying concentration. As shown in the previous section, PEP‐1 forms twisted antiparallel β‐sheet rich secondary structures at pH 7.4 and 5×10−4 M. Interestingly, decreasing the concentration to 5×10−5 M leads to a reduction of the negative CD signal at 230 nm and a concomitant emergence of another, weaker negative CD signal at ca. 205 nm (Figure 2 a). These findings indicate the reduction of β‐sheet content in the secondary structures upon dilution. Note that the observed variations in the CD pattern upon dilution can be explained by the dynamic equilibration between two conformational structures. The reduction of β‐sheet content on dilution can be further verified by concentration‐dependent ThT fluorescence assay, where the emission intensity at 490 nm decreases upon decreasing concentration, even though the concentration of ThT remains the same (Figure S11). Interestingly, the new negative CD band between 200 to 205 nm that appears upon dilution points to the presence of random coil secondary structures (Figure 2 a), [15] as also suggested by the characteristic amide‐I band at 1646 cm−1 in FTIR experiments (Figure 2 b). [16] To further understand the influence of the secondary structures on the nanostructure morphology, we have investigated AFM under diluted conditions (5×10−5 M). The images display irregular nanoparticles with sizes between 60 and 225 nm (Figure 2 c). The formation of spherical objects was further supported by AD‐DLS, which revealed isotropic distribution of nanostructures in solution (Figure S12). This concentration‐dependent transition from nanofibers to nanoparticles might be explained by the subtle interplay between intermolecular interactions. At high concentrations, the possibility of peptide molecules to come into closer contact and engage in strong intermolecular H‐bonding is more likely, thus facilitating the β‐sheet rich secondary structures. Dilution decreases the population of molecules and, consequently, their ability to form organized H‐bonds ultimately leading to irregular spherical nanoparticles of different sizes. [6d] We attempted to unravel whether interconversion between both states (twisted β‐sheet and random coil) is possible at room temperature and at a given concentration over time. However, as shown by time‐dependent CD experiments, no significant changes in the secondary structures are observed even after 24 hours, revealing the high stability of both states at room temperature (Figure S13).

Figure 2.

Concentration‐dependent CD (a) and FT‐IR studies (b) of PEP‐1 at pH 7.4 in PBS and room temperature. c) AFM image of PEP‐1 at pH 7.4 in PBS (C=5×10−5 M); d) graphical representation of nanoparticles and corresponding random coil secondary structures at low concentration.

Unravelling the Influence of Temperature on Morphological and Secondary Structural Transitions

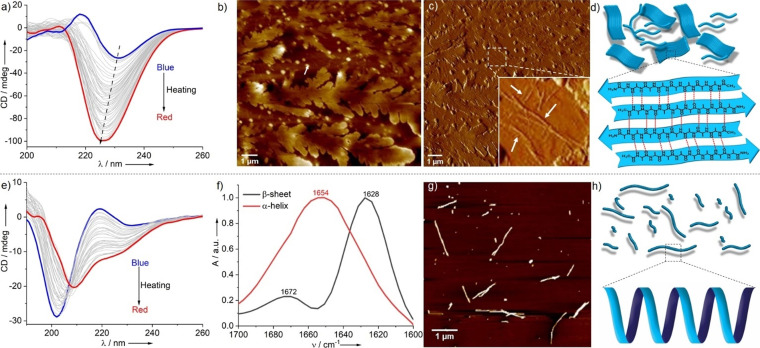

In recent years, thermal treatment protocols have been developed as a highly efficient method to isolate kinetically controlled states or to trigger the transformation of a kinetically controlled assembly into the thermodynamic state. [17] In this regard, we envisaged that interconversion between the previously generated self‐assembled structures (twisted β‐sheet and random coil) might be facilitated upon raising temperature. To our surprise, thermal annealing not only fails to initiate interconversion, but it rather enables the formation of new minima in the energy landscape. For instance, thermal treatment of the nanofibrillar structures formed at C=5×10−4 M and pH 7.4 induces a concomitant two‐fold enhancement and a shift in the CD band from 230 nm at 278 K to 225 nm at 363 K (Figure 3 a). These findings suggest that the nanofibrillar structures with twisted β‐sheet rich domains formed at room temperature represent a kinetically controlled state, which evolves into a thermodynamically controlled state (strong and well‐defined β‐sheet structures) at elevated temperatures. This effect may be rationalized by increased hydrophobic interactions upon thermal annealing, [18] which allow molecules to come into closer contact and establish strong intermolecular H‐bonding and π‐π interactions into stable conformations. This hypothesis can be verified further by combined temperature‐dependent FT‐IR and emission studies. In FT‐IR, the amide‐I band shifts to lower frequencies (from 1632 cm−1 to 1628 cm−1) upon heating to 363 K (Figure 3 f and Figure S14), implying strong intermolecular H‐bonding interactions. On the other hand, emission studies disclose a progressive reduction of the emission intensity during thermal annealing, which is in line with increased intermolecular π‐π interactions between the phenylalanine motifs upon heating (Figure S15). It has to be noted that the increased solubility and dynamic behavior of the system at high temperatures may also facilitate a molecular reorganization. To gain insights into possible morphological transformations upon raising the temperature, we have recorded AFM images of aggregate solutions of PEP‐1 at 363 K and 5×10−4 M, spin‐coated onto mica. Interestingly, thermodynamically controlled 2D sheet‐like nanostructures with branching points are observed (Figure 3 b), which significantly differ from the kinetically controlled nanofibers observed at room temperature. Upon careful analysis, we found the co‐existence of nanofibers and 2D nanosheets in some areas (Figure 3 c inset and Figure S16). These results suggest that the nanofibers formed at room temperature possibly further assemble laterally at high temperature via stronger H‐bonding and hydrophobic interactions, causing more organized β‐sheet arrangements. This phenomenon is further evidenced by AD‐DLS, where a more pronounced anisotropy is noticed in solution (Figure S17) compared to the fiber‐like nanostructures obtained at room temperature. We also questioned whether similar temperature‐dependent secondary and nanostructural transitions may occur at low concentration (5×10−5 M). Remarkably, CD experiments reveal two negative bands at 222 and 209 nm during thermal annealing (Figure 3 e) that are characteristic of an α‐helical conformation. [15] On the basis of these results, we conclude that the random coil conformation observed at 5×10−5 M is kinetically controlled and converts into a thermodynamically stable α‐helical conformation upon heating. The characteristic amide‐I band at 1654 cm−1 observed in the FT‐IR spectra upon heating further supports the formation of an α‐helix (Figure 3 f). [16] AFM studies were employed to ascertain whether this secondary structural transformation is also accompanied by a change in nanoscale morphology. Remarkably, thermodynamically controlled short nanorods are formed when the kinetically stable nanoparticles are heated to 363 K (Figure 3 g and Figure S18). The transformation of isotropic (nanoparticles at room temperature) to anisotropic nanostructures (nanorods at 363 K) is further proven by AD‐DLS (Figure S19).

Figure 3.

Temperature‐dependent CD spectra of PEP‐1 in PBS at C=5×10−4 M (a) and C=5×10−5 M (e); b) AFM image (height) of PEP‐1 at 363 K (C=5×10−4 M); c) corresponding phase image of (b) and enlarged area where nanofibers are highlighted by white arrows (inset); d) schematic representation of 2D sheet‐like structures and corresponding well‐defined β‐sheet conformations; f) FT‐IR spectra of PEP‐1 in PBS for both concentrations (C=5×10−4 M and 5×10−5 M) at 363 K; g) AFM image of PEP‐1 at 363 K (C=5×10−5 M); h) graphical illustration of short nanofibers along with α‐helix as secondary structures at 363 K.

Additional proof for the establishment of stronger intermolecular π‐π interactions upon heating was provided by temperature‐dependent emission spectra, revealing a progressive emission quenching upon annealing (Figure S20). The combined experimental findings suggest that PEP‐1 undergoes an entropy‐controlled molecular reorganization upon thermal treatment in order to maximize the non‐covalent interactions involved (H‐bonding and π‐π interactions).[ 17c , 17d ] Given the strong aggregation tendency of PEP‐1 and the fact that we were unable to identify the monomer species in any of the experiments, we hypothesize that the conformational and nanostructural transformations upon heating are consecutive processes, [8b] as also proposed for various peptide assemblies. [9] Albeit a handful of reports describing the transitions from α‐helix to β‐sheet (or vice versa) [19] or α‐helix to random coil [20] are known in the literature, peptide building blocks exhibiting such a vast variety of both morphologies and secondary structures remain, to the best of our knowledge, elusive. [9b]

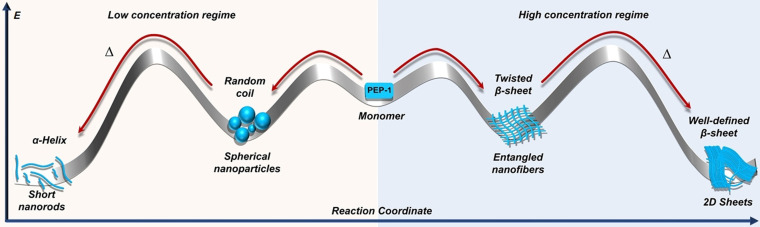

Considering the overall experimental evidence, and based on recent reports on peptide amphiphiles, [9b] we conclude that the aggregated states at room temperature for both high and low concentrations represent local minima in the energy landscape that evolve upon thermal energy input into the respective thermodynamic states. For better understanding, the different assembly pathways of PEP‐1 have been illustrated by a qualitative energy profile diagram (Figure 4). Note that due to the impossibility to extract thermodynamic parameters for the corresponding assemblies, the tentative energy diagram is only meant to give a comparative overview of the different assemblies and secondary structures depending on the temperature and concentration.

Figure 4.

Qualitative energy landscape depicting the pathway‐dependent self‐assembly of PEP‐1 at pH 7.4.

Biocompatibility and Antimicrobial Activity

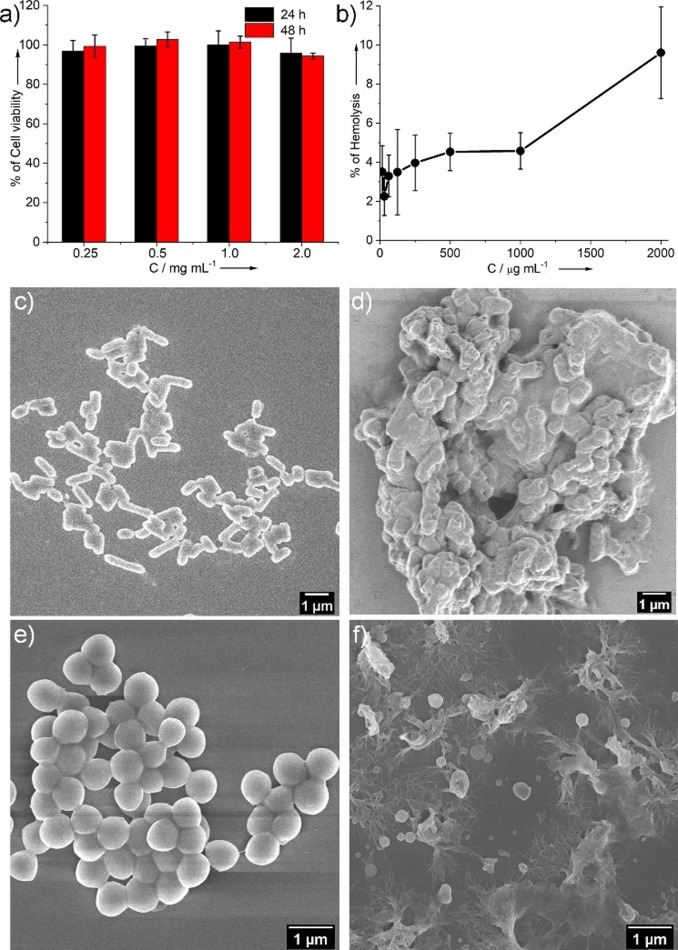

The pH‐responsive behavior of the hydrogel prompted us to investigate the biocompatibility of PEP‐1, as pH‐responsive hydrogels have been widely used as drug delivery vehicles, especially in cancer therapy. [21] For that purpose, we have investigated the cell viability of PEP‐1 by performing MTT assay with HeLa (Figure 5 a) and HEK‐293 cell lines (Figure S21). Notably, around 85–95 % cell viability was determined even at very high concentration of 2.0 mg mL−1 after 48 h of incubation at 37 °C (Figure 5 a). Additionally, we have also performed hemolysis assays of PEP‐1 with human blood, which showed low hemolytic activity (<10 %) even at high concentration (2.0 mg mL−1, Figure 5 b). These results indicate a very low capability of PEP‐1 to destruct red blood cells. As PEP‐1 contains a cationic amino acid (Lys), we were curious about the inherent antimicrobial properties of the peptide. [22] Notably, PEP‐1 exhibited anti‐microbial activity against two different clinically relevant bacterial strains, Gram‐negative E. coli and Gram‐positive S. aureus. The antibacterial activity was expressed in terms of minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC), which revealed that the PEP‐1 hydrogel is lethal for both Gram‐negative and Gram‐positive bacteria with the MIC concentration 0.31–0.62 mM (Table S1). We assume that electrostatic interactions between cationic heads of Lys moieties and the anionic bacterial membranes facilitated the entrapment of bacteria in the hydrogel, resulting in the physical destruction of the bacterial membrane and leading to cell death.[ 22a , 23 , 24 ] This hypothesis was probed by scanning electron microscopy (Figure 5 c–f; for details see SI). After treatment with the PEP‐1 hydrogel, the cell morphologies of both E. coli and S. aureus became irregular (Figure 5 d and f), in sharp contrast with the smooth and regular morphology of the untreated live bacteria (Figure 5 c and e). The overall biological studies demonstrate that PEP‐1 can become a potential candidate for applications in the field of biomedicine. The modifications of peptide‐based nanomaterials by modulating the sequences of amino acids in peptide molecules for various effective biological activities are presently underway in our laboratory.

Figure 5.

a) MTT assay of PEP‐1 with HeLa cell line; b) hemolysis assay; FESEM images of E. coli before (c) and after treatment with PEP‐1 (d); FESEM images of S. aureus before (e) and after treatment with PEP‐1 (f) [5×10−3 M].

Conclusion

In summary, we have designed an amphiphilic peptide (PEP‐1) that exhibits a rich structural variety of conformations and morphologies under controlled conditions of pH, concentration and temperature. At neutral pH (7.4), PEP‐1 self‐assembles into twisted β‐sheet rich secondary structures and forms entangled nanofibers and hydrogels. Upon altering the pH to 13.0, strong β‐sheet structures with fractal‐like nanostructures are found while disruption of the assembly and secondary structures occurs at pH 5.5. The stability of the hydrogels at neutral pH but not at pH 5.5 makes PEP‐1 a promising candidate for drug transport and delivery. [21] Concentration‐dependent studies at pH 7.4 and room temperature also revealed a rich variety of secondary conformations as well as nano‐structures. The fibers with twisted β‐sheet conformations at pH 7.4 convert into ill‐defined spherical nanoparticles upon dilution, where the peptides adopt a random coil conformation. Thus, at constant temperature (rt) and pH (7.4), PEP‐1 forms two different aggregate morphologies with distinct secondary structures (fibers with twisted β‐sheet at higher concentration vs. nanoparticles with random coil conformation at lower concentration). Interestingly, upon thermal annealing, both states evolve into new thermodynamically controlled states with distinct secondary structures: the fibers with twisted β‐sheet conformation convert into 2D sheets with strong and well‐defined β‐sheet conformation, whereas the spherical nanoparticles with random coil conformation develop into nanorods with α‐helix conformation. Thermal treatment allows the peptide units to come into closer contact, possibly influenced by changes in solvation/desolvation in aqueous media, which ultimately favors a more efficient aromatic and H‐bonding interactions. The appropriate balance of hydrophobic and polar, pH‐responsive peptide residues enables PEP‐1 to optimally respond to multiple external parameters (pH, concentration and temperature). Careful control of these variables has allowed us to produce up to six distinct aggregate morphologies and four different secondary structures from a single building block. Notably, PEP‐1 exhibits very high cell viability (85–95 %), negligible hemolytic activity and marked antimicrobial activity towards both Gram‐positive and Gram‐negative bacteria. The inherent biocompatibility and the unique supramolecular properties of our system, which in some ways resemble the complexity of some natural counterparts, may represent a new route towards multi‐stimuli responsive materials for wide range of applications in biomedicine.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supporting Information

Acknowledgements

G.G. and G.F. thank the European Commission (European Research Council) for funding (ERC‐StG‐2016 SUPRACOP‐715923). Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

G. Ghosh, R. Barman, A. Mukherjee, U. Ghosh, S. Ghosh, G. Fernández, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202113403.

Contributor Information

Dr. Goutam Ghosh, Email: gghosh.chem@gmail.com.

Prof. Dr. Suhrit Ghosh, Email: psusg2@iacs.res.in.

Prof. Dr. Gustavo Fernández, Email: fernandg@uni-muenster.de.

References

- 1.

- 1a. Whitesides G. M., Mathias J. P., Seto C. T., Science 1991, 254, 1312–1319; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 1b. Brizard A. M., van Esch J. H., Soft Matter 2009, 5, 1320–1327. [Google Scholar]

- 2.

- 2a. Dasgupta A., Das D., Langmuir 2019, 35, 10704–10724; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2b. Zhang S., Nat. Biotechnol. 2003, 21, 1171–1178; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2c. Adler-Abramovich L., Gazit E., Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014, 43, 6881–6893; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2d. Lakshmanan A., Zhang S., Hauser C. A. E., Trends Biotechnol. 2012, 30, 155–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.

- 3a. Qiu F., Chen Y., Tang C., Zhao X., Int. J. Nanomed. 2018, 13, 5003–5022; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3b. Hartgerink J. D., Beniash E., Stupp S. I., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 5133–5138; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3c. Restu W. K., Nishida Y., Yamamoto S., Ishii J., Maruyama T., Langmuir 2018, 34, 8065–8074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.

- 4a. Habibi N., Kamaly N., Memic A., Shafiee H., Nano Today 2016, 11, 41–60; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4b. Ulijn R. V., Smith A. M., Chem. Soc. Rev. 2008, 37, 664–675; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4c. Fan T., Yu X., Shen B., Sun L., J. Nanomater. 2017, 1–16; [Google Scholar]

- 4d. Hendricks M. P., Sato K., Palmer L. C., Stupp S. I., Acc. Chem. Res. 2017, 50, 2440–2448; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4e. Hamley I. W., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007, 46, 8128–8147; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2007, 119, 8274–8295; [Google Scholar]

- 4f. Hamley I. W., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 6866–6881; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2014, 126, 6984–7000; [Google Scholar]

- 4g. Liang Y., Zhang X., Yuan Y., Bao Y., Xiong M., Biomater. Sci. 2020, 8, 6858–6866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.

- 5a. Wang J., Liu K., Xing R., Yan X., Chem. Soc. Rev. 2016, 45, 5589–5604; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5b. Ghosh G., Kartha K. K., Fernández G., Chem. Commun. 2021, 57, 1603–1606; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5c. Krysmann M. J., Castelletto V., Kelarakis A., Hamley I. W., Hule R. A., Pochan D. J., Biochemistry 2008, 47, 4597–4605; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5d. Kumaraswamy P., Sethuraman S., Krishnan U. M., Soft Matter 2013, 9, 2684–2694; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5e. Hu X., Liao M., Gong H., Zhang L., Cox H., Waigh T. A., Lu J. R., Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface Sci. 2020, 45, 1–13; [Google Scholar]

- 5f. Panja S., Seddon A., Adams D. J., Chem. Sci. 2021, 12, 11197–11203; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5g. Rybtchinski B., ACS Nano 2011, 5, 6791–6818; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5h. Krieg E., Rybtchinski B., Chem. Eur. J. 2011, 17, 9016–9026; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5i. Prins L. J., Reinhoudt D. N., Timmerman P., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2001, 40, 2382–2426; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2001, 113, 2446–2492. [Google Scholar]

- 6.

- 6a. Dehsorkhi A., Castelletto V., Hamley I. W., J. Pept. Sci. 2014, 20, 453–467; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6b. Ozkan A. D., Tekinay A. B., Guler M. O., Tekin E. D., RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 104201–104214; [Google Scholar]

- 6c. Ghosh G., Barman R., Sarkar J., Ghosh S., J. Phys. Chem. B 2019, 123, 5909–5915; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6d. Ghosh G., Fernández G., Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2020, 16, 2017–2025; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6e. Falcone N., Kraatz H. B., Chem. Eur. J. 2018, 24, 14316–14328; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6f. Appel R., Tacke S., Klingauf J., Besenius P., Org. Biomol. Chem. 2015, 13, 1030–1039; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6g. Panja S., Adams D. J., Chem. Soc. Rev. 2021, 50, 5165–5200; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6h. Panja S., Dietrich B., Shebanova O., Smith A. J., Adams D. J., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 9973–9977; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2021, 133, 10061–10065; [Google Scholar]

- 6i. Ghosh G., Acta Sci. Pharm. Sci. 2021, 5, 01; [Google Scholar]

- 6j. Dowari P., Das S., Pramanik B., Das D., Chem. Commun. 2019, 55, 14119–14122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.

- 7a. Albanese A., Tang P. S., Chan W. C. W., Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2012, 14, 1–16; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7b. Mabrouk M., Das D. B., Salem Z. A., Beherei H. H., Molecules 2021, 26, 1077; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7c. Ankamwar B. in Biomedical Engineering-Technical Applications in Medicine (Eds.: Hudak R., Penhaker M., Majernik J.), InTech, Croatia, 2012, pp. 93–114. [Google Scholar]

- 8.For recent reviews on pathway complexity, see:

- 8a. Ghosh G., Dey P., Ghosh S., Chem. Commun. 2020, 56, 6757–6769; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8b. Ghosh G., Ghosh T., Fernández G., ChemPlusChem 2020, 85, 1022–1033; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8c. Hartlieb M., Mansfield E. D. H., Perrier S., Polym. Chem. 2020, 11, 1083–1110; [Google Scholar]

- 8d. Matern J., Dorca Y., Sánchez L., Fernández G., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 16730–16740; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2019, 131, 16884–16895; [Google Scholar]

- 8e. Korevaar P. A., de Greef T. F. A., Meijer E. W., Chem. Mater. 2014, 26, 576–586. [Google Scholar]

- 9.

- 9a. Korevaar P. A., Newcomb C. J., Meijer E. W., Stupp S. I., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 8540–8543; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9b. Tantakitti F., Boekhoven J., Wang X., Kazantsev R. V., Yu T., Li J., Zhuang E., Zandi R., Ortony J. H., Newcomb C. J., Palmer L. C., Shekhawat G. S., de la Cruz M. O., Schatz G. C., Stupp S. I., Nat. Mater. 2016, 15, 469–476; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9c. Kaur H., Jain R., Roy S., ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 52445–52456; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9d. Singh A., Joseph J. P., Gupta D., Sarkar I., Pal A., Chem. Commun. 2018, 54, 10730–10733; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9e. Kemper B., Zengerling L., Spitzer D., Otter R., Bauer T., Besenius P., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 534–537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Liao D. I., Kapadia G., Ahmed H., Vasta G. R., Herzberg O., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1994, 91, 1428–1432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.For recent reviews on self-assembly of amphiphilic systems, see:

- 11a. Albert S. K., Golla M., Krishnan N., Perumal D., Varghese R., Acc. Chem. Res. 2020, 53, 2668–2679; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11b. Krieg E., Niazov-Elkan A., Cohen E., Tsarfati Y., Rybtchinski B., Acc. Chem. Res. 2019, 52, 2634–2646; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11c. Sikder A., Ghosh S., Mater. Chem. Front. 2019, 3, 2602–2616; [Google Scholar]

- 11d. Krieg E., Bastings M. M. C., Besenius P., Rybtchinski B., Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 2414–2477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.For recent examples of biomedical applications of self-assembled systems, see:

- 12a. Perumal D., Golla M., Pillai K. S., Raj G., P. K. A. Krishna, Varghese R., Org. Biomol. Chem. 2021, 19, 2804–2810; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12b. Atchimnaidu S., Perumal D., Harikrishnan K. S., Thelu H. V. P., Varghese R., Nanoscale 2020, 12, 11858–11862; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12c. Shen B., Kim Y., Lee M., Adv. Mater. 2020, 32, 1905669; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12d. Kim T., Park J. Y., Hwang J., Seo G., Kim Y., Adv. Mater. 2020, 32, 2002405; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12e. Liu T., van den Berk L., Wondergem J. A. J., Tong C., Kwakernaak M. C., ter Braak B., Heinrich D., van de Water B., Kieltyka R. E., Adv. Healthcare Mater. 2021, 10, 2001903; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12f. Tong C., Wondergem J. A. J., Heinrich D., Kieltyka R. E., ACS Macro Lett. 2020, 9, 882–888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.

- 13a. Clarke D. E., Parmenter C. D. J., Scherman O. A., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 7709–7713; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2018, 130, 7835–7839; [Google Scholar]

- 13b. Pashuck E. T., Cui H., Stupp S. I., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 6041–6046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.

- 14a. Zhao Y., Yokoi H., Tanaka M., Kinoshita T., Tan T., Biomacromolecules 2008, 9, 1511–1518; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14b. Zhou X.-R., Ge R., Luo S.-Z. J., Pept. Sci. 2013, 19, 737–744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Avitabile C., D'Andrea L. D., Romanelli A., Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 4293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.

- 16a. Kong J., Yu S., Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin. 2007, 39, 549–559; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16b. Martinez G., Millhauser G., J. Struct. Biol. 1995, 114, 23–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.

- 17a. Matern J., Kartha K. K., Sánchez L., Fernández G., Chem. Sci. 2020, 11, 6780–6788; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17b. Greciano E. E., Calbo J., Ortí E., Sánchez L., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 17517–17524; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2020, 132, 17670–17677; [Google Scholar]

- 17c. Görl D., Würthner F., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 12094–12098; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2016, 128, 12273–12277; [Google Scholar]

- 17d. Syamala P. P. N., Soberats B., Görl D., Gekle S., Würthner F., Chem. Sci. 2019, 10, 9358–9366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.

- 18a. Baldwin R. L., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1986, 83, 8069–8072; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18b. Schellman J. A., Biophys. J. 1997, 73, 2960–2964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.

- 19a. Xing R., Yuan C., Li S., Song J., Li J., Yan X., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 1537–1542; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2018, 130, 1553–1558; [Google Scholar]

- 19b. Qi R., Luo Y., Ma B., Nussinov R., Wei G., Biomacromolecules 2014, 15, 122–131; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19c. Yassine W., Taib N., Federman S., Milochau A., Castano S., Sbi W., Manigand C., Laguerre M., Desbat B., Oda R., Lang J., Biochim. Biophys. Acta Biomembr. 2009, 1788, 1722–1730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.

- 20a. Huang C.-Y., Klemke J. W., Getahun Z., DeGrado W. F., Gai F., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001, 123, 9235–9238; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20b. Holtzer M. E., Bracken W. C., Holtzer A., Biopolymers 1990, 29, 1045–1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.

- 21a. Andrade F., Roca-Melendres M. M., Durán-Lara E. F., Rafael D., S. Schwartz, Jr. , Cancers 2021, 13, 1164; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21b. Raza F., Zhu Y., Chen L., You X., Zhang J., Khan A., Khan M. W., Hasnat M., Zafar H., Wu J., Ge L., Biomater. Sci. 2019, 7, 2023–2036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.

- 22a. Wan Y., Liu L., Yuan S., Sun J., Li Z., Langmuir 2017, 33, 3234–3240; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22b. Cutrona K. J., Kaufman B. A., Figueroa D. M., Elmore D. E., FEBS Lett. 2015, 589, 3915–3920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.

- 23a. Salick D. A., Kretsinger J. K., Pochan D. J., Schneider J. P., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 14793–14799; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23b. Liu Y., Yang Y., Wang C., Zhao X., Nanoscale 2013, 5, 6413–6421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.

- 24a. Konai M. M., Bhattacharjee B., Ghosh S., Haldar J., Biomacromolecules 2018, 19, 1888–1917; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24b. Takahashi H., Caputo G. A., Vemparala S., Kuroda K., Bioconjugate Chem. 2017, 28, 1340–1350; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24c. Ergene C., Yasuhara K., Palermo E. F., Polym. Chem. 2018, 9, 2407–2427. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supporting Information