Abstract

The Covid‐19 pandemic has challenged the resilience of care organisations (and those dependent on them), especially when services are stopped or restricted. This study focuses on the experiences of care organisations that offer services to individuals in highly precarious situations in 10 European countries. It is based on 32 qualitative interviews and three workshops with managers and staff. The four key types of organisations reviewed largely had the same adaptation patterns in all countries. The most drastic changes were experienced by day centres, which had to suspend or digitise services, whereas night shelters and soup kitchens had to reorganise broadly their work; residential facilities were minimally affected. Given the drastic surge in demand for services, reliance on an overburdened (volunteer) workforce, and a lack of crisis plans, the care organisations with long‐term trust networks with clients and intra‐organisational cooperation adapted easier. The outcomes were worse for new clients, migrants, psychologically vulnerable people, and those with limited communicative abilities.

Keywords: Covid‐19, organisation, pandemic, resilience, social care

Introduction

Crises bring unwanted and negative consequences that exceed what individuals, organisations, and communities have institutionalised as ‘normal’ activities and circumstances (van Laere, 2013). The Covid‐19 pandemic of 2020–21 has put to the test social care organisations and their clients’ abilities to cope with extraordinary routines. Furthermore, the resilience of the services (and those dependent on them) was brought into question when the work of care organisations was stopped to mitigate the spread of the virus or impeded owing to a shortage of personnel. At its extreme, the halting of governmental or non‐governmental services sets at increased risk the people who are dependent on these services for basic needs such as food and shelter (The World Bank, 2020; Choolayil and Putran, 2021). The loss of service to users already vulnerable due to domestic violence, homelessness, or drug or alcohol addiction may have dramatic ramifications. Furthermore, the stigmatisation of immigrants, Roma, and homeless persons as the spreaders of disease in many places throughout Europe (Holt, 2020; Mukumbang, 2021) calls for swift action by care organisations and the research community to protect human rights and prevent further marginalisation of those in already vulnerable situations.

Crisis in general results in circumstances which cannot be handled by normal resources and organisation and involves a transformation in the focus of operations in comparison to usual proceedings (Deverell and Stiglund, 2015). The Covid‐19 pandemic has concentrated the lens on existing structural inequalities and disadvantages, while simultaneously altering the reality within which social service providers negotiate practice (Banks et al., 2020; Nisanci et al., 2020). What is more, the pandemic may offer insights into how the nature and practice of social service provision can be redefined in response to an emergency.

This paper spotlights the experiences of four key types of care organisations (soup kitchens, day centres, temporary shelters, and residential facilities) that offer services to individuals in highly precarious situations or to those living on the street. The study examines the resilience of care services during the first wave of the Covid‐19 pandemic (March–June 2020), and its aims are threefold: (i) to explore if and how the activities of care organisations were altered due to the challenges introduced by the Covid‐19 pandemic; (ii) to identify the factors facilitating or impeding the ability of care organisations to provide relevant help to their users—that is, their level of resilience; and (iii) to analyse the outcomes for the different groups of clients of the care organisations.

To meet these objectives, the paper draws together the experiences of care organisations in major urban centres of 10 selected countries in Europe: Czech Republic; Estonia; Finland; Germany; Hungary; Italy; Lithuania; Norway; Portugal; and The Netherlands. These countries were chosen because they are democratic EU nations with different welfare and socioeconomic security levels and varied infection rates that may shape the pandemic's impacts on care organisations and their clients. Only in a few of them have first steps been taken to assess and tailor systematically mitigation measures to address social vulnerabilities in crises (Orru et al., 2021). The study applies an inductive multiple case study approach (Yin, 2014), which is based on 32 semi‐structured interviews and three workshops with managers and staff at care organisations (see Tables A1 and A2 in the Appendix).

Table A1.

List of interviews

| Number | Place | Date | Institution/organisation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Prague, Czech Republic | 29 May 2020 | TSA, national coordinator for social services |

| 2 | Prague, Czech Republic | 24 June 2020 | TSA social services centre |

| 3 | Tallinn, Estonia | 29 May 2020 | TSA alcohol rehabilitation centre |

| 4 | Tallinn, Estonia | 8 June 2020 | TSA day centre for material and social support for homeless and materially insecure individuals |

| 5 | Tallinn, Estonia | 16 June 2020 | Department of Social Welfare, one of Tallinn district governments |

| 6 | Tallinn, Estonia | 17 June 2020 | Welfare Centre, night shelter and resocialisation unit |

| 7 | Tallinn, Estonia | 30 June 2020 | Tallinn Social Work Centre, resocialisation accommodation |

| 8 | Helsinki, Finland | 9 June 2020 | TSA night shelter for homeless |

| 9 | Helsinki, Finland | 1 June 2020 | TSA social service centre, social counselling |

| 10 | Tampere, Finland | 28 May 2020 | TSA day centre for material and social support |

| 11 | Cologne, Germany | 8 June 2020 | The Salvation Army (TSA), Territorial Social Programmes |

| 12 | Hamburg, Germany | 19 June 2020 | TSA homeless shelter |

| 13 | Hamburg, Germany | 26 June 2020 | German Red Cross, day centre |

| 14 | Hamburg, Germany | 3 July 2020 | German Red Cross, strategy department. |

| 15 | Budapest, Hungary | 24 June 2020 | TSA, temporary shelter, rehabilitation hostel, day centre |

| 16 | Budapest, Hungary | 25 June 2020 | The Budapest Methodological Centre of Social Policy and its Institutions, homeless services |

| 17 | Budapest, Hungary | 19 June 2020 | Hungarian Red Cross, Department of Disaster Management |

| 18 | Budapest, Hungary | 1 July 2020 | The Hungarian Charity Service of the Order of Malta, central Hungary |

| 19 | Rome, Italy | 5 June 2020 | TSA homeless shelter |

| 20 | Rome, Italy | 16 July 2020 | Day centre, reception attendance services |

| 21 | Bolzano, Italy | 16 July 2020 | Day care centre for material and social support |

| 22 | Rome, Italy | 23 July 2020 | 24‐hour reception and care centre |

| 23 | Klaipeda, Lithuania | 28 May 2020 | TSA day centre for material and social support of homeless |

| 24 | Klaipeda, Lithuania | 30 June 2020 | Association of Social Workers |

| 25 | Vilnius, Lithuania | 8 July 2020 | Food bank, collects and distributes food aid |

| 26 | Oslo, Norway | 9 June 2020 | TSA housing facility for homeless people with drug or alcohol addiction |

| 27 | Oslo, Norway | 11 June 2020 | TSA day centre for active users of drugs or alcohol |

| 28 | Oslo, Norway | 12 June 2020 | Substance abuse care provision |

| 29 | Colares, Portugal | 31 March 2021 | TSA, residential centre for materially disadvantaged |

| 30 | Lisbon, Portugal | 14 April 2021 | TSA, Centre for Homeless People |

| 31 | Lisbon, Portugal | 14 April 2021 | TSA, Centre for Families and Needy People |

| 32 | Groningen, The Netherlands | 13 July 2020 | TSA day centre for material and social support of homeless |

Table A2.

List of workshops

| Place | Date | Facilities |

|---|---|---|

| Tallinn, Estonia | 15 June 2021 | Social welfare centre (homeless night shelter, day centre, long‐term rehabilitation shelter); re‐socialisation centre with 10 establishments (long‐term shelters, women's and family refuge, homeless night shelter, long‐term rehabilitation shelter for people with mental health challenges and alcohol abusers) (12 participants) |

| Oslo, Norway | 29 June 2021 | TSA (The Salvation Army) migration centre, TSA food distribution centre, TSA drug and alcohol rehabilitation centre (7 participants) |

| Tartu, Estonia | 25 August 2021 | Soup kitchen, homeless soup kitchen, rehabilitation centre (homeless night shelter, day centre, long‐term shelter), church charity (food and clothing) (5 participants) |

The analytical level on which we focus in the present study is care organisations: local and international non‐governmental organisations (NGOs) whose services are targeted at those in materially (and psychologically) difficult situations in cities (not long‐term care for the elderly or those with disabilities). We chose this level as it is the one that to a large extent defines resilient responses in the reviewed countries, such as by establishing teams across care organisations (for instance, the Salvation Army offices in large cities) for coordinated efforts. Whereas the gathered material does not allow for in‐depth comparisons between the 10 countries, our main focus remains on the variance of coping patterns within and across the different types of organisations in different national framework conditions.

This study offers important insights into what could be the strategies and the role of social care providers when faced with health crises. The Covid‐19 pandemic has provided an opportunity to reflect on the nature and practice of social service provision in order to increase preparedness for similar events in the future. It is necessary to learn from these experiences to facilitate better preparedness and optimal strategies for adaptation.

The resilience of care organisations: theoretical perspectives

The impact of crises on organisations

Existing studies indicate that large‐scale and abrupt changes may challenge the core elements of organisations: their goals, available capacities and resources, and established routines, as well as the organisational structures that support their operations in normal times (Boin and ‘t Hart, 2006). A crisis is characterised by an organisation's inadequacy concerning the ability and expertise required to handle an event as its impacts exceed what the organisation is designed to deal with (Deverell and Stiglund, 2015). During the first wave of the pandemic, while the demands for services increased, the care providers’ financial means and (human) resources diminished, and some services had to close due to financial stress and operating restrictions (Amadasun, 2020; Banks et al., 2020).

Formal and informal aspects influencing organisational resilience

In the present study, we analyse the responses of care organisations to the Covid‐19 pandemic in terms of organisational resilience. Resilience refers to a system's capacity to absorb and return to a stable state after a disruption. Barabási and Pósfai (2016, p. 303) note that: ‘A system is resilient if it can adapt to internal and external errors by changing its mode of operations, without losing its ability to function'.

One of the most well‐known approaches to organisational resilience is high reliability organisation (HRO) research, which focuses on the common characteristics of high‐risk organisations (such as aviation and nuclear facilities) that perform better on safety than one would expect (LaPorte and Consolini, 1991; Weick, Sutcliffe, and Obstfeld, 1999). HRO researchers largely relate the concept of high reliability culture to resilience (Wildavsky, 1988), arguing that cultural modes of control are essential in crisis situations. By means of organisational culture, HROs may switch between different structural modes of operation: while routine operations involve traditional, bureaucratic organisation, critical operations entail delegation premised on a centralised culture (LaPorte and Consolini, 1991). The foundation for this flexible structure is the existence of an integrated culture, centralising members around the same decision premises.

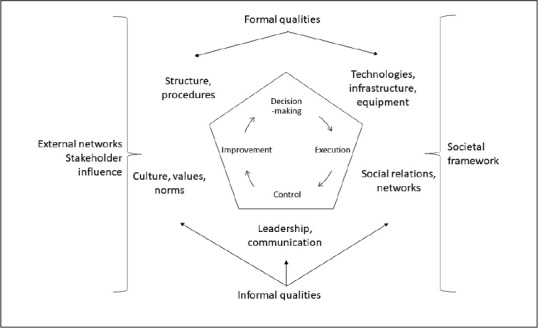

We take the Pentagon model as our point of departure in analysing the factors influencing the resilience of care organisations during the Covid‐19 pandemic (Schiefloe, 2011). The model originally centred on the organisational level, but in line with Rolstadås et al. (2014), we have adapted it, including some factors related to framework conditions. There are several different theoretical models that can be used to assess organisational resilience (see, for example, Gallopin, 2006; Deverell and Stiglund, 2015), yet a number of them are often tailored to specific settings or types of analysis. The main advantages of the Pentagon model are two‐fold: (i) as a general sociological model, it can be applied in explorative analysis in various empirical settings, ranging from fire protection to blowouts in the oil sector (see, for example, Schiefloe and Vikland, 2006; Rolstadås et al., 2014; Halvorsen, Almklov, and Gj⊘sund, 2017); and (ii) it allows for a multifaceted (including technology, structure, and culture) and multi‐layered analysis, with the organisation as the main actor in the study and influencing factors related to the organisational level (meso level) and framework conditions (macro level).

Organisational aspects

The Pentagon model (see Figure 1) focuses on five key organisational aspects: structure; technologies, infrastructure, and equipment; culture; leadership and communication; and social relations and networks (Schiefloe, 2011). The first two concentrate on formal aspects of organisations, whereas the latter three centre on informal aspects. Below, we briefly integrate these aspects into previous research by NGOs and in reference to the Covid‐19 pandemic:

Figure 1.

The Pentagon model with five key organisational aspects: structure; technologies, infrastructure, and equipment; culture; leadership and communication; and social relations and networks

Source: authors, adapted from Schiefloe (2011).

Structure. This concerns not only defined roles, responsibilities, and authority in the formal organisation, but also its procedures, regulations, and working requirements. Care NGOs are frequently part of a larger organisational network of branches, headed by a central organisation, and often rely on a voluntary workforce.

Technology, infrastructure, and equipment. This denotes the hardware, tools, and infrastructure that members of the organisation are dependent on or use to perform their activities. In a care institution this will include physical buildings and rooms, as well as hygiene facilities to protect against infection transmission (Tan and Chua, 2020). Okorley and Nkrumah (2012) point to the availability and quality of material resources for work as a factor that influences the performance of local NGOs.

Culture. This refers to factors such as shared concepts, values, norms, knowledge, and established expectations related to common ‘ways of working'. The shared ways of thinking (also related to identities and emotions) and acting provide a basis for interpreting the world, and (re)creating these interpretations in social interaction as a way of motivating and legitimising actions (Schein, 2004).

Leadership and communication. This entails management practices, work processes, flows of information, communication, cooperation, and coordination. Previous research indicates that leadership is the most important factor influencing the organisational sustainability of the needs‐based and demand‐driven programmes commonly carried out by NGOs (Okorley and Nkrumah, 2012). Top managers play a central role in adjusting the managerial and operational levels (including their own leadership, competencies, and styles) to deal with abrupt and large‐scale changes (Schein, 2004; Deverell and Olsson, 2010) and the need for extraordinary management and improvisation (Stern, 2009).

Social relations and networks. This refers to the informal structure and the social capital of the organisation. Key words and phrases are trust, friendship, access to knowledge and experiences, informal power, alliances, competition, and conflicts (Rolstadås et al., 2014). Quality and availability of personnel is a principal factor here. A situation like the pandemic will often involve lower numbers of actively working staff because of the lockdown health security measures, due to the decreasing levels of economic resources (Nisanci et al., 2020), fear of infection, and burnout (Sim and How, 2020).

According to the Pentagon model, next to internal dynamics, the organisation's functioning is shaped by the context in which it operates: the external framework conditions.

External framework conditions

We divided the external framework conditions into four categories. First is external networks with other care organisations or state institutions. A crisis for an organisation can be described as a situation where an actor alone cannot handle a specific event based on the goals, capacities, routines, and structures to which the organisation must relate (Deverell and Stiglund, 2015). Collaboration becomes a pivotal part of how organisations are expected to respond. Good relations that have been fostered before the crisis benefit organisational coping during the event (Alpaslan, Green, and Mitroff, 2009).

The second is what we refer to as the societal framework, that is, the national economic, legal, and political contexts. This refers to economic and other types of support from national and local authorities, social care providers, and NGOs. Previous research indicates that the availability of funds is crucial for successful NGO performance (Okorley and Nkrumah, 2012). Impending crises may lead to financing difficulties, such as halted donations due to economic hardship (Nisanci et al., 2020). However, next to financial security, public recognition of individuals in vulnerable situations and the need for support organisations facilitate their crisis response work (Oostlander, Bournival, and O'Sullivan, 2020).

Third is the social welfare context, which concerns the national unemployment level and the national welfare level. These factors will influence care organisations’ abilities to help, as they affect the degree of poverty and the help supplied by the welfare state. This indicates the need for the societal assistance that NGOs can provide.

Fourth is the level of Covid‐19 infection in the studied countries/cities at given points in time. This is the ultimate indicator of the need for help extended by NGOs in society, as it offers a measure of health status in society. In addition, high levels of infections are generally accompanied by lockdowns and restriction of activities, entailing higher numbers of unemployed people and rates of poverty.

Materials and methods

We combined qualitative personal interviews and workshops with document analysis, and carried out 32 qualitative interviews and three workshops with managers and staff of government services and NGOs (such as the Red Cross and the Salvation Army) across 10 European countries. A purposive sampling strategy was employed during the country studies to capture the experiences of four key types of organisations providing various services:

soup kitchens (and food banks) attended by homeless or those with difficulties coping due to their material or psychological situation;

day centres that offer counselling and hygiene facilities to the homeless and individuals with coping difficulties;

temporary shelters, including night shelters and refuges, for individuals who spend their day elsewhere; and

residential facilities offering 24/7 services, including resocialisation and alcohol and drug rehabilitation activities, which clients utilise for up to several months.

Upon written informed consent, the semi‐structured interviews with participants focused on: (i) the ways in which the organisation responded to the challenges introduced by the first wave of the Covid‐19 pandemic; (ii) what helped or hindered the response; and (iii) what were the effects on the organisation's clients. All together, 32 interviews (lasting approximately 60 minutes each) were conducted between May 2020 and April 2021. Key informants were determined on the basis of their level of experience and involvement in addressing pandemic‐related influences on the care organisation, whereas many interviewees were engaged with or overseeing several care organisations.

The same research questions were administered in three online workshops with the representatives of care organisations in Estonia and Norway from June–September 2021. The study team members first introduced the results of individual interviews and then asked for participants’ reflections on the findings from the perspective of their organisation.

As background for the interviews and workshops, we analysed, inter alia, publicly accessible policy documents and official guidelines, including state‐ and municipal‐level government regulations in response to the pandemic. We looked for documents concerning restrictions and changes in the availability of financial support as well as the care organisations’ responses to these factors. In addition, we evaluated stories in major daily newspapers that related in particular to the situation of vulnerable groups during the pandemic. Altogether 38 policy documents, 37 media articles, and 29 other types of documents (such as reports on crisis response, statistics, and care organisations) were scrutinised in line with the research questions.

Our research team members, who also performed the interviews, shared the task of undertaking preliminary analyses of interviews and documents, with those in languages other than English being read and summarised in case studies by native speakers. For each country analysis there were two deliverables: an answer sheet with brief answers to thematic questions about organisation responses and influencing factors; and a longer more detailed country study narrative. We then used qualitative thematic content analysis (Nowell et al., 2017) of the country reports to identify major commonalities and differences in the ways in which organisations responded.

To understand the societal framework conditions that may affect the responses, we searched for statistics on the state's welfare level (OECD, 2020), as well as the infection rate per 100,000 (ECDC, 2020) and unemployment‐level dynamics (Eurostat, 2020) between March and June 2020. The Organisation for Economic Co‐operation and Development (OECD)'s social expenditure percentage of gross domestic product (GDP) was the indicator used to measure countries’ welfare level. This indicator is suitable for our study because it considers social policy areas such as old age, survivors, incapacity‐related benefits, health, family, active labour market programmes, unemployment, and housing. The infection rate per 100,000 was calculated based on the total cases reported monthly in 2020 and the countries’ total population in 2019. The raw data were provided by the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC, 2020), and the unemployment rates were collected from Eurostat (2020) and represent the percentage of the active population unemployed monthly in 2020.

Results

We focused on the state's welfare level (OECD, 2020), the infection rate per 100,000 (ECDC, 2020), and unemployment‐level dynamics (Eurostat, 2020) in the period between March and June 2020. Table 1 presents the figures.

Table 1.

Case study countries’ welfare level, infection rate per 100,000, and unemployment dynamics in the study period, March–June 2020

| Czech Republic | Estonia | Finland | Germany | Hungary | Italy | Lithuania | Norway | Portugal | The Netherlands | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unemployment | Infection | Unemployment | Infection | Unemployment | Infection | Unemployment | Infection | Unemployment | Infection | Unemployment | Infection | Unemployment | Infection | Unemployment | Infection | Unemployment | Infection | Unemployment | Infection | |

| March | 2.1 | 28.2 | 4.8 | 53.9 | 6.7 | 23.7 | 3.8 | 74.5 | 3.7 | 5.0 | 8.5 | 167.1 | 6.6 | 17.3 | 3.6 | 79.2 | 6.2 | 62.4 | 2.9 | 68.0 |

| April | 2.2 | 43.0 | 6.0 | 71.8 | 7.3 | 65.1 | 4.0 | 117.1 | 4.1 | 23.4 | 7.4 | 168.7 | 7.8 | 31.9 | 4.1 | 64.6 | 6.3 | 177.9 | 3.4 | 156.5 |

| May | 2.4 | 15.5 | 7.0 | 15.0 | 8.0 | 34.8 | 4.2 | 26.9 | 4.8 | 11.2 | 8.7 | 48.2 | 8.5 | 10.6 | 4.6 | 14.0 | 5.9 | 73.1 | 3.6 | 43.1 |

| June | 2.7 | 24.2 | 8.0 | 9.2 | 7.9 | 6.9 | 4.3 | 15.4 | 4.9 | 2.8 | 9.4 | 12.9 | 8.8 | 5.2 | 5.2 | 8.3 | 7.3 | 94.5 | 4.3 | 22.9 |

| Welfare level | 19.2 | 17.7 | 29.1 | 25.9 | 18.1 | 28.2 | 16.7 | 25.3 | 22.6 | 28.9 | ||||||||||

Source: authors.

The unemployment level increased in the 10 countries in the period under review, March–June 2020. The most noteworthy changes were in Estonia and Lithuania, where the unemployment rate rose from 4.8 to 8.0 and from 6.6 to 8.8, respectively. The infection rate per 100,000 peaked in April in all of the case study countries (ECDC, 2020). On average, the highest infection rates per 100,000 were in Portugal and Italy, and the lowest was in Hungary. Comparatively, countries such as Estonia, Italy, and Lithuania had higher unemployment levels than those with higher peaks and average infection rates per 100,000 (for instance, Germany and The Netherlands). Case study countries’ welfare levels were, as noted, based on the OECD's social expenditure percentage of GDP. Countries’ social expenditure was between 16 and 30 per cent of their GDP (OECD, 2020).

Responses to the challenges introduced by the pandemic to the care organisations

The first aim of the study was to explore if and how the activities of care services were altered due to the challenges introduced by the Covid‐19 pandemic. The first‐wave effects were mainly derived from the declarations of an emergency and lockdowns by the national governments and the regulations imposed to prevent the spread of the virus. A more detailed overview of the challenges posed by the pandemic, institutional responses, influencing factors, and impacts on clients in the studied countries based on the results from interviews and document analysis is presented in Table A3 in the Appendix.

Table A3.

Challenges posed by the pandemic, institutional responses, influencing factors and impacts on clients in studied countries

| Country | Challenges introduced by the pandemic | Institutional response | Influencing factors: theoretical categories | Outcomes for users in the first wave. Did they receive help, in lower numbers, reduced form? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Czech Republic |

|

|

|

|

| Estonia |

|

|

|

|

| Finland |

|

|

|

|

| Germany |

|

|

|

|

| Hungary |

|

|

|

|

| Italy |

|

|

|

|

| Lithuania |

|

|

|

|

| Norway |

|

|

|

|

| Portugal |

|

|

|

|

| The Netherlands |

|

|

|

|

Source: authors.

Organisations providing care quickly made rearrangements that allowed for necessary services to be offered while remaining in compliance with government regulations. Based on our analysis, four key types of organisations could be distinguished according to their nature of services and the related rearrangements owing to the pandemic. Our evidence shows that inside these four key types, organisations followed largely the same adaptation patterns in all of the studied countries:

First, soup kitchens (food banks) could no longer serve food inside their premises. As a response, often with the help of volunteers and private companies, soup kitchens transitioned from serving food on the spot to distributing packages on a pick‐up basis or delivering it to homes. ‘We closed our soup kitchen at first’ said the interviewee from Estonia (29 May 2020), ‘but then we reminded ourselves what our organisation stands for and found ways to continue providing food for those in need'. Owing to the increasing numbers of individuals with economic problems, and the halt of existing sources for the homeless, such as begging and food leftovers from restaurants, the need for food support doubled or even tripled in some cases. As a Lithuanian interviewee (8 July 2020) put it: ‘Before we had to deliver for 60 individuals in one place, now the situation is as if we had to deliver food for 60 individuals in 60 places'.

Second, the most drastic changes occurred in day centres, which were closed to clients in response to government restrictions. That meant the suspension of physical meetings to provide services and amenities such as psychological support (counselling, therapies, social interaction with clients and staff), hygiene facilities (toilets, showers, laundry), activities (newspapers, television, Wi‐Fi, books), and warm rooms (possibility to use a kitchen to make tea). In physically closed day centres, communication, psychological assistance, and instructions to apply for allowances and other support were given to the clients by telephone or via the internet (e‐mail, Skype). New solutions such as Wi‐Fi networks extended to outside of the shelter, telephone‐charging points, and laundry pick‐ups were created to help clients. In Estonia, one day centre provided clothes to the homeless by noting a description of what they required by telephone. Furthermore, several day centres transitioned to distributing food outside their premises. For example, a day centre in Norway got the food delivery running in just two days after the first lockdown. In addition, many care workers from day centres (Czech Republic, Italy, Norway, and The Netherlands) changed the mode to operating on the streets, looking for the homeless to furnish them with food, masks, and other material resources.

Third, night (temporary) shelters stayed open and, in many cases (Czech Republic, Estonia, Germany, Hungary, and The Netherlands) shifted to 24‐hour service provision, to limit contact among clients who usually freely go around outside. In many cases, the clients were provided with material goods such as special food and cigarettes to curb a willingness to leave for the streets (Czech Republic and Estonia). To entertain clients who typically spend their days moving about, the managers supplied (reading and colouring) books and collections of old action and war films and necessary equipment for watching them.

Fourth, residential facilities stopped accepting new clients, but continued working. To protect the health of clients and staff, everyday life was rearranged, including the suspension of joint activities and one‐to‐one counselling sessions. While movement outside of the premises was limited for clients, facilities faced difficulties meeting social distancing requirements (because of a lack of space and the unsuitable structure of buildings, such as common toilets). For the same reason, changes were made to working schedules to avoid unnecessary mixing of personnel. Similar to temporary shelters, new activities were introduced in residential facilities to entertain clients during restrictions on socialisation and movement. For instance, a puppy was adopted by a residential centre in Portugal to calm clients.

All types of care organisations played an important role in the dissemination of reliable information on message boards, in leaflets, and by telephone to keep clients updated on the situation of the pandemic and government regulations. Overall, many countries (Czech Republic, Estonia, Germany, Hungary, Italy, and Lithuania) faced a significant increase in demand for both food aid and accommodation. The latter was solved by the opening of emergency shelters in some countries (Czech Republic, Germany, and The Netherlands), whereas some homeless people had to stay on the streets in others due to overcrowded shelters or camps (Hungary and Italy). A much higher workload along with many of the employees and volunteers belonging to risk groups (elderly or with chronic diseases) created staff shortages. Another common challenge in all countries was a lack of personal protective equipment (PPE) at the beginning of the crisis and higher operating costs owing to the rearrangements of work, an increase in services offered or the number of clients, and additional disinfection.

Factors influencing the coping of care organisations

The second aim of the study was to identify factors facilitating or impeding the care organisations’ abilities to provide relevant help to their users, that is, their level of resilience.

Organisational structures to cope with high workload and stress

For the staff of all types of care organisations, but particularly for temporary shelter and day centre personnel, the extended opening hours and/or the introduction of additional services was physically exhausting and demanded extra workers. Many organisations experienced shortages of staff, partly due to quarantines in the early phase of the pandemic, and partly because a high proportion of the volunteers were relatively old and hence were in the infection risk groups. Moreover, in the early phase, the rosters involved risk of infection and/or quarantines: ‘everybody would meet everybody'. This was changed to minimise social contact between workers and to increase resilience.

A positive was that volunteers at organisations in most countries helped to fill the gaps left by staff in risk groups (older age or chronic diseases). By drawing on the resources and possibilities within the existing organisational structure, younger volunteers were recruited. Nevertheless, it was not always easy to find new volunteers. As a soup kitchen representative said at the Estonian workshop (25 August 2021): ‘We pray every day that we would find someone, or they would find us'.

Regardless of the acquisition of some additional workers, operating on the verge of burnout was commonly reported among staff members in most of the organisations. For example, a day centre representative reported to the Norwegian workshop (28 June 2021) that care workers felt as if they were not able to do enough. This sense was exacerbated by feeling obliged to assist with the digitalisation of services, whereas normal services like self‐help groups and one‐on‐one sessions were put on hold.

Furthermore, in all types of organisations, it was emphasised that the intense work and concern about infection were mentally stressful, and that supervision by and psychological support from colleagues were limited. A source of emotional stress for operators was having to implement the closure measures. In Italy, for instance, the manager of a day care centre pointed out (16 July 2020): ‘It was very painful for us, having to tell users that we couldn't accommodate them'.

Culture

The culture of the care organisations was cited as an important facilitating factor by many of the interviewees from all types of organisations. They said that their actions and commitment to dealing with the crisis was guided by this common idea of the mission of care NGOs in society: ‘to help vulnerable people in need'. The perseverance of staff helped with reaching out to clients who they had not been able to connect with previously. ‘You keep on trying, and maybe the next day the client is less intoxicated and is able to reason better, and then something clicks', explained a Norwegian workshop participant when talking about informing the clients about risks and restrictions (28 June 2021). Some staff of social service centres, such as in the Czech Republic, also shared positive feelings of being able to put their Christian faith in action or feeling appreciated by their clients in a difficult period. And interviewed staff members in Germany expressed their gratitude for being a part of the response and assisting the most vulnerable in their community.

Technologies, infrastructure, and equipment

Interviewees generally reported that the physical facilities of day centres, temporary shelters, and residential facilities were unsuitable for a pandemic, including small rooms and people sharing a toilet and hygiene amenities. A care centre representative in Budapest, Hungary, clarified the space constraints (25 June 2020): ‘At one point we had to recommend clients to stay on the street, forest, or any outdoor areas since it was much safer there'. The downsizing of the scale of services met with a lot of frustration, as was the case in other countries, such as Norway.

In some physically closed day centres, the transition to digital counselling enabled the staff to maintain contact with their clients in new ways. However, experiences of this were mixed, and it was not welcomed by all personnel. Interviewees highlighted that social work is by essence not suitable to being done from distance. It was stressed that personal contact has to be established to help people open up about their situation and real needs. A Lithuanian social worker commented (30 June 2020): ‘You can give consultations via phone, but this way you can't see if everything is fine through non‐verbal cues, when [the] situation may be critical in real life'.

Internal relations between clients and staff

Enforcing hygiene and distancing regulations in temporary shelters and residential facilities was challenging. Clients were somewhat negative and agitated at the beginning of the crisis, yet they became increasingly more accepting of rules and grateful for support. In some countries (Estonia and Italy), a need for ongoing persuasion to follow safety instructions was needed and underscored. In the words of a social work centre representative in Estonia (30 June 2020): ‘We explained and explained … and explained once more … and this had finally a reassuring effect'. In soup kitchens and temporary and residential facilities in some countries, such as Estonia, Finland, Germany, Norway, and The Netherlands, it was underlined that good relationships with clients were essential to conveying crisis messages and ensuring compliance with restrictions.

Expressions of gratitude, the feeling of solidarity with other clients, and understanding and collaborative residents helped the staff to manage the situation as a whole. For example, the Estonian workshop (25 August 2021) revealed that clients of the temporary shelter that had turned into a 24‐hour centre appreciated that staff stayed around and were available for consultations every day throughout the lockdown. The significance of a long‐term relationship of trust between the staff and the clients was cited as a key factor in successful adaptation to the situation in many organisations. This relationship helped to reinforce the message that the restrictions are purposeful: ‘If a rule is put into force, then there must be a reason for that', noted a participant at the Estonian workshop (25 August 2021) while explaining compliance attitudes.

Leadership, communication, and cooperation

In many cases, the organisation leaders relied on their long‐term experience in the field when adapting to Covid‐19 and finding solutions. As one of the Estonian soup kitchen representatives pointed out (25 August 2021): ‘We have been in the field for 20 years, and we have seen other, even more severe crisis situations, and these experiences have helped to overcome also current difficulties'. An interviewee at a Portuguese day centre (14 April 2021) added: ‘The pandemic experience has taught us to rethink the intervention model without losing the reason why we serve the population that is in our care. More than ever, it is a mission far greater than the set of tasks we must perform on a daily basis'.

Cooperation between different (types of) care organisations grew even stronger. For example, in Finland, collaboration occurred in the provision of food and clean needles for the homeless, whereas in Lithuania, telephones and a workspace for psychologists to establish a helpline were supplied. In Norway, care organisations increased cooperation to synchronise food distribution in Oslo city centre, whereas in Hungary, the existing alliance of care NGOs and government authorities was employed to coordinate care work.

External framework conditions: social relations and networks

The public health and economic situation, crisis management context, and in particular, insufficient or delayed support from the authorities challenged the coping of all types of organisations. Confusing official rules and a lack of guidelines were repeatedly singled out, particularly by the representatives of temporary shelters. It was said that social care for the homeless and other vulnerable groups tends to ‘fall in between’ guidelines, as these organisations are neither health institutions nor care homes. In the majority of cases, the first impression was that the generally under‐recognised groups had become even more invisible: ‘It felt like the city had forgotten us’ (Helsinki, 9 June 2020).

In several cases, strong advocacy by social services helped to make their voices heard. From the beginning of the crisis, managers of social centres were confronted with policies and restrictions that did not account for the needs of social service centres and their clients. In a couple of countries (Czech Republic and Hungary), care organisations brought their concerns to their local government and asked for clarification regarding regulations and requested that the government provide PPE, financial resources to care services, and emergency accommodation for the homeless.

In some other countries, it was easier for the care organisations to convey their needs. For instance, interviewees in Germany and Norway, the countries with a stronger relationship between social services and the government, noted that the authorities were open to the requests of welfare organisations as they have an ongoing understanding of the needs of the populations with which they work. These positive exchanges and the clarity of information received were vital for staff morale and led to personnel not only feeling equipped to disseminate accurate information to clients, but also knowledgeable about ways to rearrange services to align with regulations. However, certain client groups served by organisations (migrant day centre) were considered by the local government only after the second wave of the pandemic, following a long lament (Norwegian workshop, 28 June 2021). Most notably, in Hungary, the government and the Hungarian Association of NGOs for Development and Humanitarian Aid were called into action to ensure that their professional activities were coordinated without overburdening any organisations, and that all assistance, including communication materials, was provided to all parts of the country.

When it comes to societal recognition, some interviewees (Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Italy, and Norway) stated that general negative attitudes towards homeless people in society worsened, as they were seen as spreaders of the virus and thus stigmatised. Stark political resentment towards the homeless culminated in the criminalisation of homelessness in the Czech Republic and further tightening of the bans on the homeless staying in public places in Hungary. In Italy, some centres closed; others resisted, having to make their own arrangements without much support or guidance from state institutions.

Overall, the interviewed staff members (in, for example, Czech Republic, Hungary, Italy, and Norway) pointed out that the pandemic revealed the structural inequalities that exist within the welfare systems for certain populations. The pandemic aggravated the situation among some groups, such as migrants, who were not able to receive the same services (attendance and emergency support) due to their different legal status in Italy and Norway, among other countries.

As for material support, donations from communities and private companies, as well as the voluntary workforce, were an important source of help in many countries. Lastly, the fact that the beginning of the pandemic was in the spring of 2020 noticeably lessened the negative impact of day centres closing down, since it was not so cold outside.

Outcomes of the pandemic for users

The third aim of the study was to examine the outcomes for different groups of clients. Below, we summarise the results that are relevant to this objective.

First, the interviews revealed the multifaceted impacts of the Covid‐19 crisis on homeless people and the clients of care services. Clients of residential centres such as rehabilitation or night shelters that reorganised to achieve full provision felt most safe and taken care of.

Access to night shelters and soup kitchens (food banks) was mostly provided to all who required it, although numbers increased significantly, and sometimes doubled due to new, ‘first‐time’ clients (Czech Republic, Estonia, Finland, and Norway). Those who were managing (some economic hardship or difficulties with independent psychological coping) prior to the crisis faced more difficulties owing to the decreasing chances of returning to work, meeting with social workers, and suspended access to day centres during the emergency.

Country‐by‐country differences appeared among the homeless clients of night shelters. Frustration manifested among the homeless because they lived a paradox of not being allowed to be on the street and having nowhere to stay—they were often fined and removed by police in the Czech Republic and Hungary. This also occurred among migrant groups living on the street in Italy.

In most countries, homeless and other materially or psychologically disadvantaged clients lost their usual access to day centres and their services, such as toilets, showers, entertainment, kitchen amenities, and a washing machine, as well as to psychosocial assistance, including counselling, therapies, or other personal interaction with staff. Those who were among the most fragile in these groups or who lacked the means or skills to access digital counselling may not have reached out for help at all.

The loss of the routine and social circle normally provided by the day and residential centres was another reason for difficulties with the restrictions. Despite efforts to communicate with clients using telephones and the internet, social isolation and loneliness were described, impacting more severely on those with psychological disorders.

Digital counselling was often not accessible due to a lack of digital literacy skills or access to the internet. Certain client groups (such as migrants and refugees) did not have the access permits or the digital and/or language skills necessary to communicate using digital services (Norwegian workshop, 28 June 2021). Furthermore, it was difficult to help individuals who frequented drug and alcohol rehabilitation centres and supply them with information and guidelines, as they are often difficult to reach and do not show up to their appointments (Norwegian workshop, 28 June 2021). In addition, it was reported that clients with more private problems or who were more closed in nature, as well as new clients, might have not expressed their need for help by telephone. A positive was that many of the clients started to use the internet—for example, using digital signatures and communicating via e‐mail.

The psychologically fragile clients struggled the most due to increased fears and paranoias. Interviewed personnel worried that the effect on their emotional well‐being would worsen in time.

Discussion

Challenges introduced by the Covid‐19 pandemic on care organisations The first aim of the study was to explore if and how the activities of care organisations were altered due to the challenges introduced by the Covid‐19 pandemic. On average, the highest infection rates per 100,000 were in Portugal and Italy, and were the lowest in Hungary. Estonia, Finland, and Lithuania had higher unemployment levels. Many countries faced a significant rise in demand for both food aid and accommodation, particularly for ‘first‐time’ clients, but also for the homeless who were banned from the streets. Linking the country statistics and interview results, the increased demand for food and shelter appears to be particularly stark in those countries where the employment opportunities decreased the most (Estonia, Finland, and Lithuania). These results are in accordance with descriptions from previous research on the first wave, indicating greater demand for services, while the care providers faced challenges related to diminishing means and operating restrictions (Amadasun, 2020; Banks et al., 2020; Dayson et al., 2021).

Our study reveals that across countries, the different types of services experienced similar changes: immediate cancellation of socialisation activities and obligations to close down some facilities. Night shelters and soup kitchens had to reorganise broadly their work to minimise contacts, but residential facilities were minimally affected. The most drastic changes were experienced by day centres, which had to suspend a large proportion of their client services, such as hygiene facilities, socialising (comforting from staff and peers), and a warm room, due to the lockdowns. Only in some day centres were psychological assistance and counselling regarding applications for allowances and other support available by telephone or via the internet. Yet, not all of the clients were able to access the digitalised services owing to a lack of skills and equipment and being frightened by the new situation and requirements.

In all care organisations, staff invested effort in supplying information and guidance to their clients and in reaching out to local homeless people to make sure that they stayed safe. This role was particularly important to alleviate clients’ susceptibility to rumours and false claims that may increase their risk (Hansson et al., 2020), as was particularly evident during the Covid‐19 crisis (Hansson et al., 2021). Volunteers were involved in distributing food and other aid on the streets or delivering it to homes.

In the absence of specific guidelines in the early phases of the pandemic, organisations had to come up with their own rules to maintain operations safely and find resources to support their clients without provision from authorities. This resembles the core of the definition of resilience that we apply in the present study: the capacity to adapt to internal and external errors by changing the mode of operations, without losing the ability to function (Barabási and Pósfai, 2016, p. 303). At the same time, however, our results confirm the lack of consideration of social vulnerabilities in risk assessments and crisis planning to support those who have fallen into a vulnerable situation or seen one aggravated due to the crisis (Orru et al., 2021), including among care organisations in European countries.

Factors facilitating or impeding the care organisations’ resilience

The second aim of the study was to identify the factors facilitating or impeding the ability of social organisations to provide relevant help to their users, that is, their level of resilience. Based on the Pentagon model of Schiefloe (2011), some of the main factors impeding resilience were related to the formal aspects of the organisations, in other words, the organisational structure. Most notable in this regard were a lack of personnel, rosters that were unsuitable for a pandemic, a high workload and stress, especially in night shelters that now turned into long‐term shelters, and infrastructure (inappropriate physical facilities), particularly in day centres and night shelters, but also in soup kitchens.

Additional factors were negative external framework conditions. The public health situation and economic and crisis management context in many country cases were characterised by insufficient or delayed support from the government and municipalities. Our results on the lack of information and guidelines issued by official sources and the lack of authorities’ recognition of care organisations’ contribution to providing safety to large population groups confirm earlier findings (Banks et al., 2020; Oostlander et al., 2020). In some countries, a general negative attitude towards homeless people in society worsened as they were seen as spreaders of the virus and thus stigmatised.

We may conclude, based on the Pentagon model, that some of the main factors facilitating resilience were related to leadership and culture, particularly in the day centres and night shelters that had to reorganise their services to a large extent. Leadership was central, as leaders, at different levels, were cooperating within and across the organisation and were crucial in producing new solutions—this is in accordance with previous research (Schein, 2004; Deverell and Olsson, 2010; Okorley and Nkrumah, 2012). Moreover, in several cases, strong advocacy by the leaders of social services helped to make their voices heard.

The results also indicate that the mission to assist is an important component of the organisational culture that guided their actions and commitment in dealing with the crisis. Several institutions compensated for the challenging physical infrastructure vis‐à‐vis infection control through innovative solutions, such as inventive ways of entertaining quarantined clients, food deliveries and trucks, and approaching clients on the streets. In these ways, they were still able to provide help to their clients, that is, maintain organisational resilience. The development of such solutions was to a great extent related to experienced staff's knowledge of their clients. This conclusion that culture may be a crucial source of resilience, galvanising members around the same decision premises, is in line with the focus of HRO research (LaPorte and Consolini, 1991; Weick, Sutcliffe, and Obstfeld, 1999). However, when confronted with a lack of human and material resources, pursuing the mission to aid risks the physical and mental health of staff and cannot be sustained during a long‐term crisis.

Social relations and networks were also important. The changed situation and new modes of operating affected internal relations between staff and clients in all types of organisation. Explaining and enforcing the safety restrictions and rearrangements required a lot of effort by staff members. Yet, in some countries (such as Estonia, Finland, Germany, and Norway), collaborative relations between residents and staff helped in particular to manage the situation as a whole. Here, solidarity between clients and staff even increased.

As for external relations, the study demonstrates that the common objective to assist vulnerable people facilitated collaboration between organisations and the development of workable solutions among soup kitchens, day centres, and night shelters (such as in Estonia, Finland, Hungary, and Norway). This confirms the understanding that in a time of crisis, organisations (and individuals) benefit from the good relations that have been fostered before the event. Crises, though, especially long‐term ones like the Covid‐19 pandemic, also tend to introduce a new set of stakeholders and forms of collaboration, which need to be created within a limited amount of time (Alpaslan, Green, and Mitroff, 2009). Established collaborative projects indicate the significance of social capital that emanates from external networks as a fundamental factor in improving the resilience of organisations.

The analysis highlights the role of social service centres as advocates for policies more in tune with the needs of their clients. The pandemic revealed the structural inequalities that exist within welfare systems towards certain population groups, which aggravate the situation of those who are already vulnerable. For instance, the migrants’ inhibited access to basic emergency services demonstrates the lack of consideration of social vulnerabilities in crisis planning in many of the European countries reviewed in existing studies (see, for instance, Orru et al., 2021). Monitoring governmental policies and flagging plans and recommendations that are harmful to vulnerable groups are examples of the work done to enhance the external conditions in which the organisations needed to operate during the Covid‐19 pandemic. This is vital in a time of crisis, as existing studies indicate that disasters can be used as an excuse to marginalise and scapegoat further vulnerable groups, including immigrants, ethnic minorities, and those living in poverty (Devakumar et al., 2020; Nisanci et al., 2020; Mukumbang, 2021). It is likely that without the intervention of care services, governmental responses would have been much slower and less attuned to the real needs of the homeless.

However, the studied country authorities demonstrated varied responsiveness to the pleas of organisations. Advocacy work was more successful in countries where stronger alliances between the state and non‐governmental care services existed before the crisis (such as in Estonia, Germany, and Hungary). By contrast, in some countries (such as Italy and Lithuania), many closures of centres could have been prevented if the government had been willing to work with social services to make sure that they were able to administer their operations in a safe way instead of requiring a halt to all face‐to‐face interactions, such as in day centres.

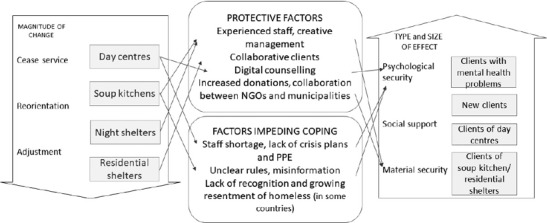

Figure 2 sums up the main factors facilitating and impeding resilience.

Figure 2.

Changes introduced in organisations, protective factors and factors impeding coping, and the size and types of effects on clients

Source: authors.

Outcomes for the different groups of clients

The third aim of the study was to assess the outcomes for the different groups of clients. Figure 2 shows that the pandemic and the subsequent responses of the studied care organisations entailed different types of outcomes for different types of clients relying on different types of services. Overall, some of the greatest effects of the pandemic were experienced by the individuals who had to turn to care services for the first time. These people had been struggling to cope economically or due to mental health prior to the pandemic, and given the overwhelming health, social, and economic aspects of the crisis, they experienced a loss of hope in entering the job market or finding other ways of improving their situation. This indicates the very dynamic nature of social vulnerability in a crisis, as calamities may push people who have coped sufficiently well before into a vulnerable situation.

The existing clients of residential rehabilitation facilities or night shelters that reorganised to achieve full provision felt most safe and taken care of. In contrast, frustration appeared among the homeless because, paradoxically, they were not allowed to be on the street but had nowhere to stay—often they were fined and removed by police in Czech Republic and Hungary. This was also the case in Italy for migrant groups living on the street. In addition, despite efforts to communicate with clients using the telephone and the internet, social isolation and loneliness were described, impacting more severely on those with mental disorders. Furthermore, the digitalised service formats did not permit all individuals who were in need of support to be reached owing to poor access to the internet or digital skills. Lastly, psychologically fragile clients struggled the most owing to increased fears and paranoias. Thus, although the care organisations were able to maintain operations, they were less successful in providing help to some groups.

Methodological limitations and issues for future research

This explorative study on care organisations’ responses to the Covid‐19 pandemic of 2020–21 necessarily used a qualitative approach to map out the different responses by different types of organisations and the variety of determinants of responses by these organisations. The main analytical focus was not a comparison of countries, nor of individual organisations within the 10 countries. The findings of this study should be seen as a starting point for a more detailed investigation to define the impacts of Covid‐19 and safety measures among different types of care services and different groups of service users. Future studies could also conduct in‐depth comparisons of national contexts, using more data from each country. For a more detailed understanding of the relevance of these factors, a more structured survey engaging more organisations would be a welcome development. Current research centred on the experiences of the homeless and individuals in precarious situations that have reached out to care organisations reveals that they are ‘saved', as one of the interviewees put it, at least to some extent. However, the resilience of those individuals in vulnerable situations that do not receive the support of any governmental or non‐governmental agencies needs further investigation. Future research should take a more in‐depth look at the perspectives of clients of care organisations.

Conclusion

Instead of closing down as a response to the Covid‐19 threat and associated restrictions, the care organisations employed their long‐term experiences and trust networks in dealing with clients, and shifted their structure and mode of operations to pursue the mission. Across countries, relatively similar changes occurred in the four key types of care organisations: while day centres needed to suspend their support or digitalise fundamental counselling activities, night shelters and soup kitchens broadly reorganised their work to minimise contacts; residential facilities were minimally affected. However, the increasing demand for services, the overburdening of staff with new tasks (such as digitalisation), and the mounting infection threat rarely met with appropriate support from health and care authorities. Therefore, the vulnerability of the limited (volunteer) workforce and organisational coping became evident. Those with a closer working relationship with other care organisations and governmental institutions fared better in mobilising support to meet the surge in need for food and accommodation assistance, reworking their services, and disseminating accurate information. The infrastructure, including inappropriate physical facilities, and a lack of PPE for infection control were the main factors impeding resilience.

This study demonstrates that existing structural inequalities, including limited access to official (health) emergency services, aggravate the situation of those who are already vulnerable (such as migrants owing to poor communication skills) during the crisis unless they find support networks within care organisations, among others. In spite of the relatively resilient response of the care organisations, outcomes were worse among some types of vulnerable groups than others. Next to psychologically fragile clients and migrants, new clients—individuals who found themselves in a vulnerable situation for the first time—were critically challenged. Future research should take an in‐depth look at these sources and mechanisms of vulnerability during crises. National and municipal risk analyses and contingency planning should incorporate the views and experiences of care organisations to ensure fair representation of these actors and their clients’ needs. Crisis support funds and stronger institutional alliances with care organisations are needed to maintain access to safe services and trusted (information) networks among those who have fallen into a vulnerable situation. Both anti‐discrimination measures and proactive awareness‐raising are crucial to prevent the discrimination of disadvantaged groups in future crises.

Appendix

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

Endnotes

Kati Orru is an Associate Professor in Sociology of Sustainability at the Institute of Social Sciences, University of Tartu, Estonia; Kristi Nero is a PhD candidate at the Institute of Social Sciences, University of Tartu, Estonia; Tor‐Olav Nævestad is a Chief Research Sociologist at the Transport Economics Institute, Norway; Abriel Schieffelers is a Project Coordinator at the European Affairs Office, Salvation Army, Belgium; Alexandra Olson is a Project Coordinator at the European Affairs Office, Salvation Army, Belgium; Merja Airola is a Senior Scientist at the VTT Technical Research Centre of Finland, Finland; Austeja Kazemekaityte is a PhD candidate at the University of Trento, Italy; Gabriella Lovasz is a Senior Project Officer at Geonardo Ltd, Hungary; Giuseppe Scurci is a Researcher at the University of Trento, Italy; Johanna Ludvigsen is a Chief Research Economist at the Transport Economics Institute, Norway; and Daniel A. de los Rios Pérez is a Lecturer at the Jönköping International Business School, Jönköping University, Sweden.

References

- Alpaslan, C.M. , Green S.E., and Mitroff I.I. (2009) ‘Corporate governance in the context of crises: towards a stakeholder theory of crisis management’. Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management. 17(1). pp. 38–49. 10.1111/j.1468-5973.2009.00555.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Amadasun, S. (2020) ‘Social work and Covid-19 pandemic: an action call’. International Social Work. 63(6). pp. 753–756. 10.1177/0020872820959357. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Banks, S. et al. (2020) ‘Practising ethically during Covid-19: social work challenges and responses’. International Social Work. 63(5). pp. 569–583. 10.1177/0020872820949614. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barabási, A.-L. and Pósfai M. (2016) Network Science. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. [Google Scholar]

- Boin, A. and 't Hart P. (2006) ‘The crisis approach’. In Rodríguez H., Quarantelli E.L., and Dynes R. (eds.) Handbook of Disasters Research. Springer, New York, NY. pp. 42–54. [Google Scholar]

- Choolayil, A.C. and Putran L. (2021) ‘The Covid-19 pandemic and human dignity: the case of migrant labourers in India’. Journal of Human Rights and Social Work. 6(3). pp. 225–236. 10.1007/s41134-021-00185-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dayson, C. , Bimpson E., Ellis-Paine A., Gilbertson J., and Kara H. (2021) ‘The “resilience” of community organisations during the Covid-19 pandemic: absorptive, adaptive and transformational capacity during a crisis response’. Voluntary Sector Review. 12(2). pp. 295–304. 10.1332/204080521X16190270778389. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Devakumar, D. , Shannon G., Bhopal S.S., and Abubakar I. (2020) ‘Racism and discrimination in Covid-19 responses’. The Lancet. Correspondence. 395(10231). p. 1194. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30792-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deverell, E. and Olsson E.-K. (2010) ‘Organizational culture effects on strategy and adaptability in crisis management’. Risk Management. 12(2). pp. 116–134. 10.1057/rm.2009.18. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Deverell, E. and Stiglund J. (2015) ‘Crisis: designing a method for organizational crisis investigation’. In Schiffino N. et al. (eds.) Organizing after Crisis: The Challenge of Learning. P.I.E. Peter Lang, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- ECDC (European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control) (2020) Covid-19 Situation Update for the EU/EEA, as of 5 October 2021. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/cases-2019-ncov-eueea (last accessed on 7 October 2021). [Google Scholar]

- Eurostat (2020) Unemployment by sex and age – monthly data. Website. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/une_rt_m/default/table?lang=en (last accessed on 7 October 2021).

- Gallopin, G. (2006) ‘Linkages between vulnerability, resilience and adaptive capacity’. Global Environmental Change. 16(3). pp. 293–303. 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2006.02.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Halvorsen, K. , Almklov P.G., and Gj⊘sund G. (2017) ‘Fire safety for vulnerable groups: the challenges of cross-sector collaboration in Norwegian municipalities’. Fire Safety Journal. 92 (September). pp. 1–8. 10.1016/j.firesaf.2017.05.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hansson, S. et al. (2020) ‘Communication-related vulnerability to disasters: a heuristic framework’. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction. 51 (December). Article number: 101931. 10.1016/j.ijdrr.2020.101931. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hansson, S. et al. (2021) ‘Covid-19 information disorder: six types of harmful information during the pandemic in Europe’. Journal of Risk Research. 24(3–4). pp. 380–393. 10.1080/13669877.2020.1871058. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Holt, E. (2020) ‘Covid-19 lockdown of Roma settlements in Slovakia’. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 20 (6). p. 659. 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30381-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaPorte, T.R. and Consolini P.M. (1991) ‘Working in practice but not in theory: theoretical challenges of high-reliability organizations’. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory. 1(1). pp. 19–47. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1181764. [Google Scholar]

- Mukumbang, F.C. (2021) ‘Pervasive systemic drivers underpin Covid-19 vulnerabilities in migrants’. International Journal for Equity in Health. 20. Article number: 146. 10.1186/s12939-021-01487-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nisanci, A. , Kahraman R., Alcelik Y., and Kiris U. (2020) ‘Working with refugees during Covid-19: social worker voices from Turkey’. International Social Work. 63(5). pp. 685–690. 10.1177/0020872820940032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nowell, L.S. , Norris J.M., White D.E., and Moules N.J. (2017) ‘Thematic analysis: striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria’. International Journal of Qualitative Methods. 16(1). 10.1177/1609406917733847. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) (2020) ‘Social expenditure – aggregated data’. OECD.Stat website. https://stats.oecd.org/viewhtml.aspx?datasetcode=SOCX_AGG&lang=en (last accessed on 7 October 2021).

- Okorley, E.L. and Nkrumah E.E. (2012) ‘Organisational factors influencing sustainability of local non-governmental organisations: lessons from a Ghanaian context’. International Journal of Social Economics. 39 (5). pp. 330 –341. 10.1108/03068291211214190. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oostlander, S.A. , Bournival V., and O'Sullivan T.L. (2020) ‘The roles of emergency managers and emergency social services directors to support disaster risk reduction in Canada’. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction. 51 (December). Article number: 101925. 10.1016/j.ijdrr.2020.101925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orru, K. et al. (2021) ‘Approaches to “vulnerability” in eight European disaster management systems’. Disasters. 10.1111/disa.12481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Rolstadås, A. , Tommelein I., Schiefloe P.M., and Ballard G. (2014) ‘Understanding project success through analysis of project management approach’. International Journal of Managing Projects in Business. 7(4). pp. 638–660. 10.1108/IJMPB-09-2013-0048. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schein, E.H. (2004) Organizational Culture and Leadership. Third edition. Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, CA. [Google Scholar]

- Schiefloe, P.M. (2011) Mennesker og samfunn. Fagbokforlaget, Bergen. [Google Scholar]

- Schiefloe, P.M. and Vikland K.M. (2006) ‘Formal and informal safety barriers: the Snorre A incident’. In Soares C.G. and Zio E. (eds.) Safety and Reliability for Managing Risk. Taylor and Francis, London. pp. 419–426. [Google Scholar]

- Sim, H. and How C. (2020) ‘Mental health and psychosocial support during healthcare emergencies – Covid-19 pandemic’. Singapore Medical Journal. 61(7). pp. 357–362. 10.11622/smedj.2020103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern, E.K. (2009) ‘Crisis navigation: lessons from history for the crisis manager in chief’. Governance. 22(2). pp. 189–202. 10.1111/j.1468-0491.2009.01431.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tan, L.F. and Chua J.W. (2020) ‘Protecting the homeless during the Covid-19 pandemic’. Chest. 158(4). pp. 1341–1342. 10.1016/j.chest.2020.05.577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The World Bank (2020) ‘Food security and Covid-19’. Agriculture and Food Brief. 23 August. Website. https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/agriculture/brief/food-security-and-covid-19 (last accessed on 7 October 2021).

- van Laere, J. (2013) ‘Wandering through crisis and everyday organizing: revealing the subjective nature of interpretive, temporal and organizational boundaries’. Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management. 21(1). pp. 17–25. 10.1111/1468-5973.12012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weick, K.E. , Sutcliffe K.M., and Obstfeld D. (1999) ‘Organizing for high reliability: processes of collective mindfulness’. Research in Organizational Behavior. 21. pp. 81–123. [Google Scholar]

- Wildavsky, A.B. (1988) Searching for Safety. Transaction Books, New Brunswick, NJ. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.K. (2014) Case Study Research: Design and Methods. SAGE Publications, Inc., Thousand Oaks, CA. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.