Abstract

Background

In JADE COMPARE, abrocitinib improved severity of atopic dermatitis (AD) and demonstrated rapid itch relief.

Objectives

We examined clinically meaningful improvements in selected patient‐reported outcomes (PROs).

Methods

JADE COMPARE was a multicentre, phase 3 randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial. Adults with moderate‐to‐severe AD were randomized 2:2:2:1 to receive 16 weeks of oral abrocitinib 200 or 100 mg once daily, dupilumab 300 mg subcutaneous injection every 2 weeks, or placebo, with background topical therapy. PROs included Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI), Patient‐Oriented Eczema Measure (POEM), Night Time Itch Scale (NTIS), Pruritus and Symptoms Assessment for Atopic Dermatitis, Patient Global Assessment, SCORing Atopic Dermatitis, and Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale.

Results

At week 16, the proportion of patients achieving POEM scores <3 was 21.3% and 11.7% for 200 and 100 mg abrocitinib, 12.4% for dupilumab, and 4.8% for placebo (vs. abrocitinib, P < 0.0001 and P = 0.04). Proportion achieving ≥4‐point improvement from baseline in NTIS severity was 64.3% and 52.4% for 200 and 100 mg abrocitinib, 54.0% for dupilumab, and 34.4% for placebo (vs. abrocitinib, P < 0.0001 and P = 0.007). Proportion achieving ≥4‐point improvement from baseline in DLQI was 85.0% and 74.4% for 200 and 100 mg abrocitinib, 83.4% for dupilumab, and 59.7% for placebo (vs. abrocitinib, P < 0.0001 and P = 0.005).

Conclusion

Significant improvements in PROs were demonstrated with both abrocitinib doses vs. placebo, and abrocitinib 200 mg provided numerically greater effects compared with dupilumab in patients with moderate‐to‐severe AD.

Short abstract

Linked Commentary L. Stingeni et al. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2022; 36: 326–327. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.17956.

Introduction

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a chronic, relapsing, inflammatory skin disease associated with diminished health‐related quality of life (HRQoL). 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 Reduced HRQoL in AD is strongly associated with itch, sleep disturbance, and psychological distress. 5 , 6 , 7 Increased AD severity is associated with worse HRQoL. 2 , 3 , 4 , 7 , 8 , 9

AD is managed with trigger avoidance, emollients, and topical anti‐inflammatory agents, including corticosteroids, calcineurin inhibitors, and phosphodiesterase‐4 inhibitors. 10 Patients who insufficiently respond to these therapies have limited treatment options: phototherapy, systemic immunosuppressive agents (cyclosporine, azathioprine, methotrexate, and mycophenolate mofetil), as well as baricitinib and dupilumab. Dupilumab, a humanized monoclonal antibody that inhibits the interleukin‐4 receptor‐α subunit, was approved in 2017 for the treatment of adults with moderate‐to‐severe AD. Dupilumab is effective and generally well tolerated, although ocular side effects such as conjunctivitis are common, 11 and facial erythema is a problem for some patients. 12 Furthermore, dupilumab is administered by subcutaneous injection; many patients prefer therapies with less invasive routes of administration (i.e. oral administration). 13 Many more systemic treatments are becoming available for the treatment of moderate‐to‐severe AD, with baricitinib, tralokinumab, upadacitinib, and abrocitinib recently gaining approval in some geographic regions.

Abrocitinib is an oral, once‐daily JAK‐1–selective inhibitor that was developed for the treatment of moderate‐to‐severe AD. 14 , 15 , 16 The efficacy and safety of abrocitinib 200 and 100 mg as monotherapy in comparison with placebo were demonstrated in adults with moderate‐to‐severe AD in the phase 3 JADE MONO‐1 14 and JADE MONO‐2 trials. 15 JADE COMPARE demonstrated the safety and efficacy of abrocitinib 200 and 100 mg vs. dupilumab and placebo in adults with moderate‐to‐severe AD receiving background medicated topical therapy. 16

Patient‐reported outcomes (PROs) complement clinician‐evaluated endpoints by capturing patients' perspectives on the extent of treatment benefits and clinically meaningful improvements. 17 The Harmonizing Outcome Measures for Eczema (HOME) initiative recommends that trials in patients with AD have standardized outcome assessments that incorporate both clinician‐evaluated measures and PROs. 18 JADE COMPARE included Patient‐Oriented Eczema Measure (POEM) and Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) assessments, which are core instruments recommended by the HOME initiative for evaluating patient‐reported symptoms and HRQoL, respectively. 17 , 19 Other PRO assessments were the Pruritus and Symptoms Assessment for Atopic Dermatitis (PSAAD), Patient Global Assessment (PtGA), Night Time Itch Scale (NTIS), SCORing Atopic Dermatitis (SCORAD), Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), and EuroQoL 5‐Dimension 5‐Level (EQ‐5D‐5L). These analyses evaluated PROs from JADE COMPARE in adults with moderate‐to‐severe AD.

Patients and methods

Study design, patients, and treatment

A phase 3, multicentre, randomized, double‐blind, double‐dummy, placebo‐controlled study (JADE COMPARE; NCT03720470) evaluated the efficacy and safety of abrocitinib 200 and 100 mg once daily vs. placebo and dupilumab in adults with moderate‐to‐severe AD who were receiving background medicated topical therapy. This study enrolled patients from 29 October 2018 to 5 August 2019 in North and South America, Australia, Europe, and Asia. Full inclusion and exclusion criteria have been published previously. 16 Eligible patients were aged ≥18 years, had moderate‐to‐severe AD at baseline (Investigator’s Global Assessment [IGA] ≥ 3, Eczema Area and Severity Index [EASI] ≥ 16, body surface area involvement ≥10%, Peak Pruritus Numerical Rating Scale [PP‐NRS] ≥4), and a history of inadequate response to ≥4 weeks of medicated topical therapy or required systemic therapy to control AD. The PP‐NRS was used with permission from Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc., and SAR&D. Patients who previously used a systemic JAK inhibitor or dupilumab were ineligible to participate.

Patients were randomly assigned in a 2 : 2 : 2 : 1 ratio to 16 weeks of treatment with oral abrocitinib 200 mg once daily, oral abrocitinib 100 mg once daily, subcutaneous dupilumab 300 mg every other week (following a 600‐mg loading dose), or placebo (Fig. S1, Supporting Information). Throughout the study, background medicated topical therapy with low‐ or medium‐potency topical corticosteroids, topical calcineurin inhibitors, or topical phosphodiesterase‐4 inhibitors was to be applied to areas with active lesions and for 7 days after lesions were under control (clear or almost clear) (see Supplementary Methods for additional details).

The study protocol and informed consent documents were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board and/or Independent Ethics Committee at each investigational site. The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, the International Council for Harmonization Good Clinical Practice guidelines, and all local regulatory requirements.

PRO assessments

PRO assessments included here are DLQI, 20 POEM, 21 PSAAD, 22 PtGA, NTIS, SCORAD, 23 HADS, 24 and EQ‐5D‐5L. 25 The recall period, range of scores, response criteria and/or minimal clinically important difference, and schedule of assessments are summarized in Table S1, Supporting Information. PRO assessment of peak itch severity in the previous 24 h, PP‐NRS, was a key secondary endpoint of JADE COMPARE, and results have been reported previously. 16 In addition to prespecified analyses, we conducted post hoc assessments of the proportions of patients who achieved a clinically meaningful improvement in POEM, PSAAD, PtGA, SCORAD sleep loss, HADS, and DLQI (see Results for details).

Statistical analysis

The full analysis set (FAS) included all patients who received ≥1 dose of study medication. Mixed‐model repeated measures were used to assess least squares mean (LSM) and LSM of change from baseline for DLQI, POEM, PSAAD, SCORAD sleep loss, HADS, and EQ‐5D‐5L (FAS, observed data). This model for LSM of change from baseline included the factors (fixed effects) for treatment group, disease severity group, visit, treatment‐by‐visit interaction, and relevant baseline value, while the model for LSM included the factors for treatment group, disease severity group, visit, and treatment‐by‐visit interaction. Cochran‐Mantel‐Haenszel tests (FAS, non‐responder imputation) were used to assess the proportion of patients meeting response criteria (defined in Table S1, Supporting Information). Endpoint analyses were based on available data up to and including week 16. If a patient withdrew early from the trial and no drug was dispensed at week 16, all available data for that patient were included in the analysis. Significance was indicated at the nominal level of 0.05 or 5%; there were no adjustments for multiplicity.

Results

Baseline demographics and disease characteristics

In total, 837 patients received study drug (abrocitinib, dupilumab, or placebo) and were included in this analysis. Baseline demographics and disease characteristics were balanced across groups (Table 1). Median age was 34 years; 51.1% of patients were female. According to the IGA, 65% of patients had moderate AD and 35% had severe AD. Mean (SD) EASI score was 30.9 (12.8). Mean (SD) duration of AD was approximately 23 (15) years, and mean (SD) percentage of body surface area affected was approximately 49% (23%). Use of background topical therapy is summarized in Table S2, Supporting Information.

Table 1.

Baseline demographics and disease characteristics

|

Total (N = 837) |

Placebo (n = 131) |

Abrocitinib 100 mg once daily (n = 238) |

Abrocitinib 200 mg once daily (n = 226) |

Dupilumab 300 mg every other week (n = 242) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Age in years, mean (SD) |

37.7 (14.7) | 37.4 (15.2) | 37.3 (14.8) | 38.8 (14.5) | 37.1 (14.6) |

|

Female sex, n (%) |

428 (51.1) | 54 (41.2) | 118 (49.6) | 122 (54.0) | 134 (55.4) |

| Race, n (%) | |||||

| White | 606 (72.4) | 87 (66.4) | 182 (76.5) | 161 (71.2) | 176 (72.7) |

| Black | 35 (4.2) | 6 (4.6) | 6 (2.5) | 9 (4.0) | 14 (5.8) |

| Asian | 178 (21.3) | 31 (23.7) | 48 (20.2) | 53 (23.5) | 46 (19.0) |

| Other | 18 (2.2) | 7 (5.3) | 2 (0.8) | 3 (1.3) | 6 (2.5) |

|

Duration of AD in years, mean (SD) |

22.7 (15.4) | 21.4 (14.4) | 22.7 (16.3) | 23.4 (15.6) | 22.8 (14.8) |

| IGA, n (%) | |||||

| Moderate | 541 (64.6) | 88 (67.2) | 153 (64.3) | 138 (61.1) | 162 (66.9) |

| Severe | 296 (35.4) | 43 (32.8) | 85 (35.7) | 88 (38.9) | 80 (33.1) |

|

EASI, mean (SD) |

30.9 (12.8) | 31.0 (12.6) | 30.3 (13.5) | 32.1 (13.1) | 30.4 (12.0) |

|

%BSA, mean (SD) |

48.5 (23.1) | 48.9 (24.9) | 48.1 (23.1) | 50.8 (23.0) | 46.5 (22.1) |

AD, atopic dermatitis; BSA, body surface area; EASI, Eczema Area and Severity Index; IGA, Investigator’s Global Assessment; SD, standard deviation.

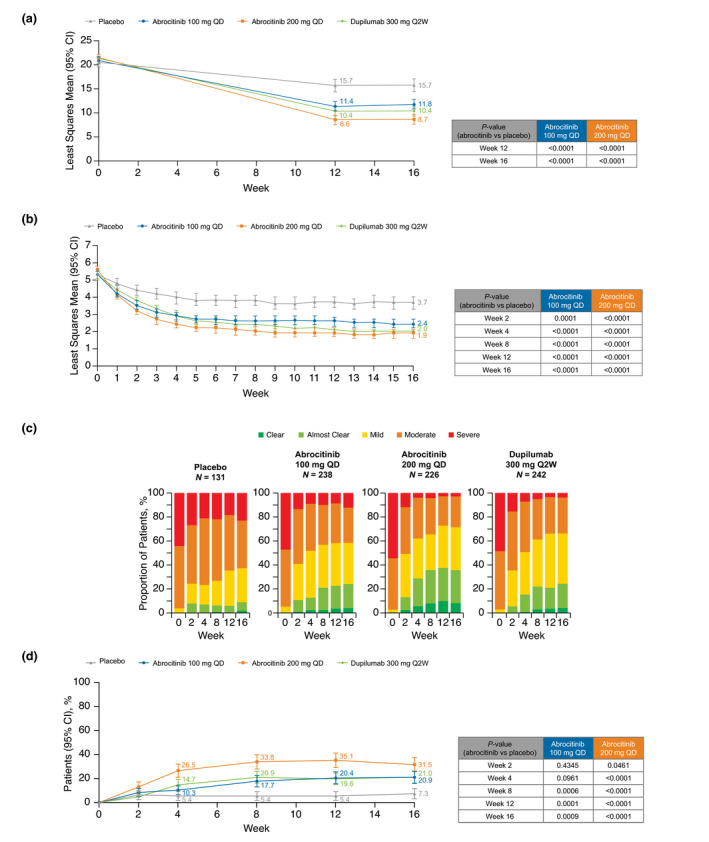

Patient‐Oriented Eczema Measure

Compared with placebo, a significant decrease in POEM scores was observed with both abrocitinib doses at weeks 12 and 16 (Fig. 1a). At week 16, LSM change from baseline in POEM score was −12.5 for abrocitinib 200 mg, −9.2 for abrocitinib 100 mg, −10.8 for dupilumab, and −5.0 for placebo (vs. both abrocitinib groups, P < 0.0001). In a post hoc analysis of proportions of patients meeting criteria for clinically meaningful improvement in POEM (achieving score <3 [among those with ≥3 score at baseline]), a higher proportion of responders was observed in both abrocitinib groups compared with placebo at weeks 12 and 16. Proportions achieving a POEM score of <3 at week 16 were 21.3% for abrocitinib 200 mg, 11.7% for abrocitinib 100 mg, 12.4% for dupilumab, and 4.8% for placebo (vs. abrocitinib groups, P < 0.0001 and P = 0.04, respectively; Table S3, Supporting Information).

Figure 1.

(a) Least squares mean Patient‐Oriented Eczema Measure (MMRM: FAS, OD), (b) least squares mean Pruritus and Symptoms Assessment for Atopic Dermatitis (MMRM: FAS, OD), (c) categorical summary of Patient Global Assessment (FAS, OD), and (d) proportion of patients achieving 'clear' or 'almost clear' and ≥2 point improvement from baseline in Patient Global Assessment (Cochran‐Mantel‐Haenszel: FAS, NRI). CI, confidence interval; FAS, full analysis set; MMRM, mixed‐model repeated measures; NRI, non‐responder imputation; OD, observed data; Q2W, every 2 weeks; QD, once daily.

Pruritus and Symptoms Assessment for Atopic Dermatitis

There was a significant decrease in AD symptom severity as measured by the PSAAD scale (range 0–10 [10 = extreme]) from week 1 with both abrocitinib doses compared with placebo, and this improvement was maintained through week 16 (Fig. 1b). At week 16, LSM change from baseline in PSAAD was −3.6 points for abrocitinib 200 mg, −2.8 for abrocitinib 100 mg, −3.4 for dupilumab, and −1.7 for placebo (vs. both abrocitinib groups, P < 0.0001). In a post hoc analysis of the proportions of patients achieving a clinically meaningful PSAAD response (achieving ≥1‐point improvement [among those with ≥1 point at baseline]), a higher proportion of responders was observed with both abrocitinib groups compared with placebo at weeks 1 through 16. At week 16, proportions achieving a PSAAD response were 82.7% for abrocitinib 200 mg, 75.9% for abrocitinib 100 mg, 80.2% for dupilumab, and 55.3% for placebo (vs. both abrocitinib groups, P < 0.0001; Table S4, Supporting Information).

Patient Global Assessment

A post hoc analysis of the proportion of patients in each PtGA category (range 0–4 [0 = clear, 4 = severe]) indicated greater improvements with both abrocitinib doses compared with placebo, with changes seen as early as week 2 (first post‐baseline assessment) (Fig. 1c). In a post hoc analysis of the proportion of patients with a clinically meaningful PtGA response (achieving 'clear' [0] or 'almost clear' [1] and ≥2 point improvement from baseline [among those with ≥2 points at baseline]), a higher proportion of responders was observed with both doses of abrocitinib compared with placebo at weeks 8, 12, and 16 (Fig. 1d). At week 16, proportions achieving a PtGA score of clear/almost clear were 31.5% for abrocitinib 200 mg, 20.9% for abrocitinib 100 mg, 21.0% for dupilumab, and 7.3% for placebo (vs. abrocitinib groups, P < 0.0001 and P = 0.0009, respectively).

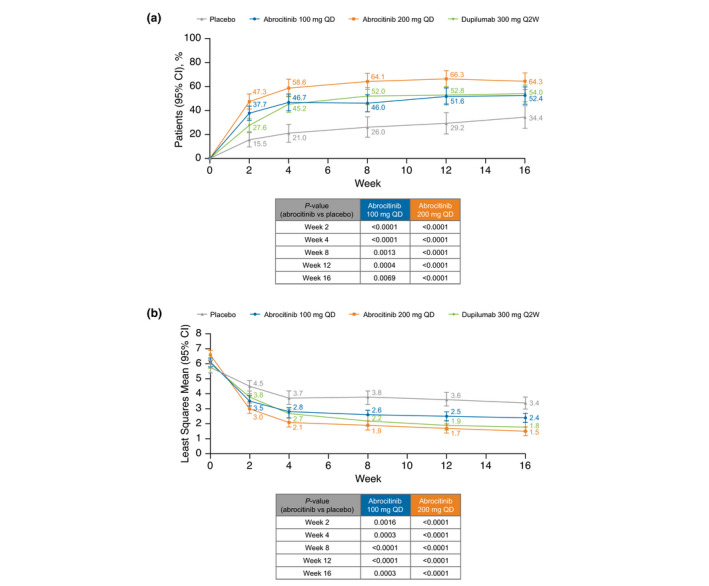

Night Time Itch Scale severity item

The proportion of patients meeting the criteria for clinically meaningful improvement (≥4‐point improvement from baseline) on the NTIS severity item (range 0–10 [10 = worst itch imaginable]) with both abrocitinib doses was significantly higher compared with placebo from week 2 to 16 (Fig. 2a). At week 16, proportions achieving clinically meaningful improvement were 64.3% for abrocitinib 200 mg, 52.4% for abrocitinib 100 mg, 54.0% for dupilumab, and 34.4% for placebo (vs. abrocitinib groups, P < 0.0001 and P = 0.007, respectively).

Figure 2.

(a) Proportion of patients achieving ≥4‐point improvement from baseline in NTIS severity item (Cochran‐Mantel‐Haenszel: FAS, NRI) and (b) least squares mean SCORAD VAS of sleep loss (MMRM: FAS, OD). CI, confidence interval; FAS, full analysis set; MMRM, mixed‐model repeated measures; NRI, non‐responder imputation; NTIS, Night Time Itch Scale; OD, observed data; Q2W, every 2 weeks; QD, once daily; VAS, visual analog scale.

SCORing Atopic Dermatitis sleep loss visual analog scale

Patients treated with abrocitinib 200 mg or 100 mg had significant improvement in LSM SCORAD sleep loss visual analog scale (VAS; range 0‐10 [10 = worst imaginable]) vs. placebo beginning at week 2 and at all time points through week 16 (Fig. 2b). At week 16, LSM change from baseline in SCORAD sleep loss VAS score was −4.8 for abrocitinib 200 mg, −3.7 for abrocitinib 100 mg, −4.3 for dupilumab, and −2.6 for placebo (vs. both abrocitinib groups, P < 0.0001). In a post hoc analysis of the proportions of patients achieving a clinically meaningful SCORAD sleep loss VAS score (<2 points [among those with ≥2 points at baseline]) at week 16, there were 68.4% responders for abrocitinib 200 mg, 52.8% for abrocitinib 100 mg, 58.5% for dupilumab, and 32.0% for placebo (vs. abrocitinib groups, P < 0.0001 and P = 0.0008, respectively) (Table S5, Supporting Information).

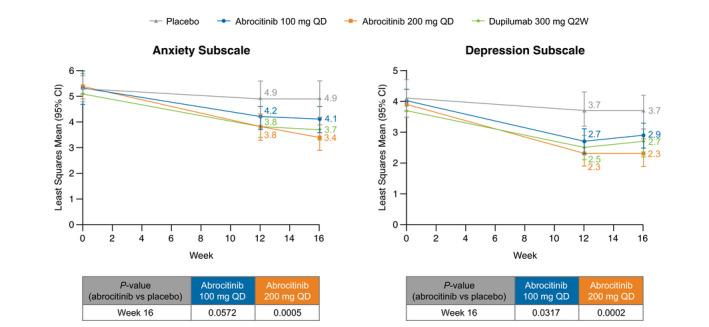

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale

Compared with placebo, significant differences in LSM scores on both HADS anxiety and depression symptom subscales (range 0–21 [21 = worst symptoms]) were seen at weeks 12 and 16 with abrocitinib 200 mg and at weeks 12 and 16 for the depression symptom subscale with abrocitinib 100 mg (Fig. 3). At week 16, LSM score change from baseline in HADS‐Anxiety score was −2.0 for abrocitinib 200 mg, −1.2 for abrocitinib 100 mg, −1.5 for dupilumab, and −0.4 for placebo (vs. abrocitinib groups, P < 0.0001 and P = 0.02, respectively). At week 16, LSM change from baseline in HADS‐Depression was −1.6 for abrocitinib 200 mg, −1.0 for abrocitinib 100 mg, −1.2 for dupilumab, and −0.3 for placebo (vs. abrocitinib groups, P < 0.0001 and P = 0.0181, respectively). In a post hoc analysis of patients with HADS‐Anxiety ≥8 at baseline (cut‐off for identification of anxiety), the proportions achieving a score of <8 points at week 16 were 53.1% (34/64) for abrocitinib 200 mg, 45.0% (27/60) for abrocitinib 100 mg, 48.9% (22/45) for dupilumab, and 23.5% (8/34) for placebo (vs. abrocitinib groups, P = 0.006 and P = 0.04, respectively; Table S6, Supporting Information). In a post hoc analysis of patients with HADS‐Depression ≥8 at baseline (cut‐off for identification of depression), the proportions achieving a score of <8 points at week 16 were 66.7% (28/42) for abrocitinib 200 mg, 68.6% (24/35) for abrocitinib 100 mg, 66.7% (24/36) for dupilumab, and 33.3% (10/30) for placebo (vs. abrocitinib groups, P = 0.007 and P = 0.005, respectively; Table S6, Supporting Information).

Figure 3.

Least squares mean Hospital and Anxiety Depression Scale—mixed‐model repeated measures (FAS, OD). CI, confidence interval; FAS, full analysis set; OD, observed data; Q2W, every 2 weeks; QD, once daily.

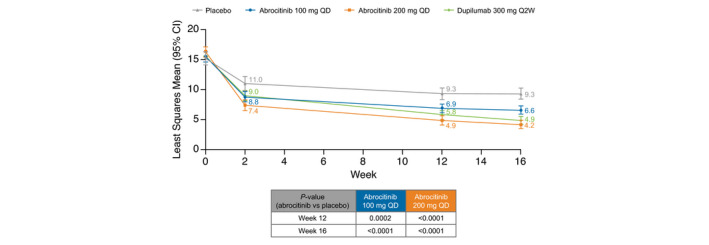

Dermatology Life Quality Index

A significant improvement in AD‐specific HRQoL as assessed by the DLQI (range 0–30 [30 = worst HRQoL]) occurred at week 2 with both abrocitinib doses compared with placebo and was maintained at weeks 12 and 16 (Fig. 4). At week 16, LSM change from baseline in DLQI score was −11.7 for abrocitinib 200 mg, −9.0 for abrocitinib 100 mg, −10.8 for dupilumab, and −6.2 for placebo (vs. both abrocitinib groups, P < 0.0001). In a post hoc analysis, a higher proportion of patients had clinically meaningful improvement in DLQI (achieving ≥4‐point improvement from baseline [among those with ≥4 points at baseline]) in both abrocitinib groups compared with placebo at weeks 2, 12, and 16. Proportions achieving clinically meaningful improvement in DLQI at week 16 were 85.0% for abrocitinib 200 mg, 74.4% for abrocitinib 100 mg, 83.4% for dupilumab, and 59.7% for placebo (vs. abrocitinib groups, P < 0.0001 and P = 0.005, respectively; Table S7, Supporting Information).

Figure 4.

Least squares mean Dermatology Life Quality Index—mixed‐model repeated measures (FAS, OD). CI, confidence interval; FAS, full analysis set; OD, observed data; Q2W, every 2 weeks; QD, once daily.

EuroQoL 5‐dimension 5‐level

A significant improvement in generic HRQoL on the EQ‐5D‐5L index value (generally range 0–1.0 [1.0 = full health]) was seen with both doses of abrocitinib compared with placebo at weeks 12 and 16 (Table S8, Supporting Information). At week 16, LSM change from baseline in EQ‐5D‐5L index value was 0.13 for abrocitinib 200 mg, 0.09 for abrocitinib 100 mg, 0.11 for dupilumab, and 0.07 for placebo (vs. abrocitinib, P < 0.0001 and P = 0.03, respectively). A significant increase in HRQoL based on EQ‐5D‐5L VAS (range 0–100 [100 = best health you can imagine]) was demonstrated with abrocitinib 200 mg compared with placebo at weeks 12 and 16; however, the abrocitinib 100 mg dose did not reach significance vs. placebo (Table S9, Supporting Information). At week 16, LSM change from baseline in EQ‐5D‐5L VAS was 16.71 for abrocitinib 200 mg, 11.22 for abrocitinib 100 mg, 14.41 for dupilumab, and 7.84 for placebo (vs. abrocitinib, P < 0.0001 and P = 0.06, respectively).

Discussion

JADE COMPARE is the first randomized, placebo‐controlled, clinical trial of abrocitinib that includes an active comparator, dupilumab, which is approved for use in moderate‐to‐severe AD. It is also the first abrocitinib clinical trial that allowed concomitant use of background medicated topical therapy, which reflects the anticipated real‐world treatment paradigm. 16

Rapid, robust improvements from baseline in PROs were consistently reported with oral abrocitinib 200 and 100 mg once daily in adults with moderate‐to‐severe AD. Significant improvements for both abrocitinib doses compared with placebo were evident as early as week 2 (first postbaseline visit for most PROs) and were generally maintained at subsequent time points up to week 16. At weeks 12 and 16, a higher proportion of patients had clinically meaningful improvements with abrocitinib 200 mg than with dupilumab or abrocitinib 100 mg. The proportion of patients with clinically meaningful improvements in PROs with abrocitinib 100 mg was similar to that with dupilumab for POEM, PtGA, NTIS severity, and HADS‐Depression and was numerically lower than dupilumab for PSAAD, SCORAD sleep, and HADS‐Anxiety at week 16. The clinically meaningful improvements (minimally clinically important differences are described in Table S1, Supporting Information) in PROs observed with abrocitinib are likely to be mediated, at least in part, by the rapid itch response demonstrated with once‐daily abrocitinib treatment in JADE COMPARE. 16

As previously reported, the safety profile of abrocitinib in JADE COMPARE was consistent with previous studies, and abrocitinib demonstrated rapid improvement in the signs and symptoms of AD compared with placebo. 16 Swift and clinically meaningful improvements in severity of patient‐reported signs and symptoms are desirable in patients with AD. 13 , 26 , 27 More than half of patients with moderate‐to‐severe AD have inadequately controlled disease despite the use of currently available therapies. 28 Such patients have increased symptoms of depression, stress, itch interfering with daily living, sleep disturbance interfering with daily living, reduced HRQoL, and work productivity impairment. 28 , 29 In this analysis, once‐daily abrocitinib demonstrated a rapid effect on the NTIS severity item and improvement in sleep loss.

LSM change from baseline in DLQI, POEM, PSAAD, HADS‐Anxiety, and HADS‐Depression at week 12 in patients who received abrocitinib 100 and 200 mg once‐daily in JADE COMPARE are comparable with data reported from phase 3 JADE MONO‐1 and MONO‐2. 14 , 15 LSM change from baseline in DLQI, POEM, and SCORAD sleep loss and the proportion of patients achieving ≥4‐point improvement in DLQI at week 16 with dupilumab in this study are comparable with dupilumab results reported from phase 3 SOLO‐1 and SOLO‐2 11 , 30 and CHRONOS. 31

The main limitation of this analysis was that this 16‐week study was relatively short; the longer‐term efficacy and safety of abrocitinib are being assessed in ongoing trials. Furthermore, there is the potential for differences between patients who elect or are eligible to participate in clinical trials and those who are treated in real‐world settings. Patients with recent (within the past year) or active suicidal ideation or clinically significant depression (based on a total score ≥15 on the Patient Health Questionnaire‐8 items) were ineligible for this trial, although ˜17% of patients met criteria for depression according to baseline HADS. Use of background medicated topical therapy and emollients in this trial increases the applicability of these findings to real‐world settings, but may have increased the placebo effect. 32 The study was not designed to evaluate the superiority of abrocitinib over dupilumab using statistical testing in these PRO endpoints (abrocitinib vs. dupilumab comparisons were performed for the key secondary endpoint [≥4‐point improvement from baseline in PP‐NRS at week 2] and are reported elsewhere). 16 However, results of these PROs consistently suggested that better efficacy was achieved with abrocitinib 200 mg than with abrocitinib 100 mg or dupilumab 300 mg every other week. The efficacy of abrocitinib 100 mg and dupilumab appeared to be similar. Adolescent patients were not included in this study; efficacy and safety of abrocitinib in adolescents have been demonstrated in phase 3 JADE TEEN. 33

In conclusion, once‐daily treatment with oral abrocitinib 200 and 100 mg in patients with moderate‐to‐severe AD in the phase 3 JADE COMPARE trial showed significantly greater improvements in all PRO assessments compared with placebo, including the core assessments recommended by HOME. Improvements occurred as early as week 2 and were sustained through week 16. Abrocitinib 200 mg appeared to have a greater effect than dupilumab.

Author contributions

MD, HV, DM, and SK contributed to the conceptualization of the study. FZ and the sponsor’s programming group performed or supported the formal analysis. All authors (JT, GY, CP, SK, C‐YC, MD, CF, FZ, DM, RR, HV) contributed to the data interpretation, critically reviewed the manuscript, and approved the submitted version.

Supporting information

Supplementary Methods

Table S1. Patient‐reported outcome measures used in this analysis

Table S2. Summary of the use of background topical therapy

Table S3. Proportion of patients achieving <3 points in Patient‐Oriented Eczema Measure—Cochran‐Mantel‐Haenszel (FAS with ≥3 points at baseline, NRI)

Table S4. Proportion of patients achieving ≥1‐point improvement from baseline in PSAAD—Cochran‐Mantel‐Haenszel (FAS with ≥1 point at baseline, NRI)

Table S5. Proportion of patients achieving <2 points in SCORAD sleep loss VAS—Cochran‐Mantel‐Haenszel (FAS with ≥2 points at baseline, NRI)

Table S6. Proportion of patients achieving <8 points in HADS‐Anxiety or HADS‐Depression at weeks 12 and 16 (FAS with ≥8 points at baseline, NRI)

Table S7. Proportion of patients achieving ≥4 points improvement from baseline in Dermatology Life Quality Index—Cochran‐Mantel‐Haenszel (FAS with ≥4 points at baseline, NRI)

Table S8. Least squares mean of change from baseline in EQ‐5D‐5L, index value—mixed‐model repeated measures (FAS, OD)

Table S9. Least squares mean of change from baseline in EQ‐5D‐5L, VAS score—mixed‐model repeated measures (FAS, OD)

Figure S1. JADE COMPARE phase 3 study design

Acknowledgements

Editorial/medical writing support under the guidance of authors was provided by Renee Gordon, PhD, CMPP, and Mariana Ovnic, PhD at ApotheCom, San Francisco, CA, USA, and was funded by Pfizer Inc., New York, NY, USA in accordance with Good Publication Practice (GPP3) guidelines (Ann Intern Med. 2015;163:461–464).

Trial registration: NCT03720470

Conflicts of interest

JPT is an advisor/investigator or speaker for Almirall, Pfizer, AbbVie, Eli Lilly, LEO Pharma, Regeneron, and Sanofi‐Genzyme and received grant funding from Regeneron and Sanofi‐Genzyme. GY is a consultant and advisor for Pfizer Inc., Bellus Health, Eli Lilly, Galderma, Kiniksa Pharmaceuticals, LEO Pharma, Novartis, Sanofi Regeneron, and Trevi Therapeutics and a principal investigator for Pfizer Inc., Galderma, Kiniksa Pharmaceuticals, LEO Pharma, Novartis, and Sanofi Regeneron. CP has been a consultant and an investigator for Almirall, Amgen, AbbVie, Bristol Myers Squibb, Boehringer Ingelheim, Celgene, Eli Lilly, Janssen, LEO Pharma, Merck, Mylan, Novartis, Pfizer, Pierre Fabre, Sanofi, and UCB. SGK is an advisory board member/consultant for AbbVie, Galderma, Incyte Corporation, Menlo Therapeutics, Pfizer Inc., Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, and Kiniksa Pharmaceuticals and has received grant funding from Galderma, Pfizer Inc., and Kiniksa Pharmaceuticals. C‐YC is an investigator for Pfizer Inc., AbbVie, Dermira, Eli Lilly, Novartis, Oneness Biotech, Regeneron, Roche, and Sanofi; a consultant for Pfizer Inc., AbbVie, Eli Lilly, Novartis, Roche, and Sanofi; a speaker for Pfizer Inc., AbbVie, Eli Lilly, Mylan, Novartis, Roche, and Sanofi; and is on advisory boards for Pfizer Inc., Mylan, Roche, and Sanofi. MD, CF, FZ, DM, RR, and HV are employees and stockholders of Pfizer Inc.

Funding sources

This trial was sponsored by Pfizer Inc. The trial sponsor, Pfizer Inc., designed the trial, collected/analysed the data, provided drug and placebo, and funded medical writing/editorial support.

Data availability statement

Upon request, and subject to certain criteria, conditions and exceptions (see https://www.pfizer.com/science/clinical‐trials/trial‐data‐and‐results for more information), Pfizer will provide access to individual de‐identified participant data from Pfizer‐sponsored global interventional clinical studies conducted for medicines, vaccines, and medical devices (1) for indications that have been approved in the US and/or EU or (2) in programs that have been terminated (i.e. development for all indications has been discontinued). Pfizer will also consider requests for the protocol, data dictionary, and statistical analysis plan. Data may be requested from Pfizer trials 24 months after study completion. The de‐identified participant data will be made available to researchers whose proposals meet the research criteria and other conditions, and for which an exception does not apply, via a secure portal. To gain access, data requestors must enter into a data access agreement with Pfizer.

References

- 1. Weidinger S, Beck LA, Bieber T, Kabashima K, Irvine AD. Atopic dermatitis. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2018; 4: 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chiesa Fuxench ZC, Block JK, Boguniewicz M et al. Atopic dermatitis in America study: a cross‐sectional study examining the prevalence and disease burden of atopic dermatitis in the US adult population. J Invest Dermatol 2019; 139: 583–590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Silverberg JI, Gelfand JM, Margolis DJ et al. Health utility scores of atopic dermatitis in US adults. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2019; 7: 1246–1252.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Silverberg JI, Gelfand JM, Margolis DJ et al. Patient burden and quality of life in atopic dermatitis in US adults: a population‐based cross‐sectional study. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2018; 121: 340–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Drucker AM, Wang AR, Li WQ, Sevetson E, Block JK, Qureshi AA. The burden of atopic dermatitis: summary of a report for the National Eczema Association. J Invest Dermatol 2017; 137: 26–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wittkowski A, Richards HL, Griffiths CE, Main CJ. The impact of psychological and clinical factors on quality of life in individuals with atopic dermatitis. J Psychosom Res 2004; 57: 195–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Simpson EL, Guttman‐Yassky E, Margolis DJ et al. Association of inadequately controlled disease and disease severity with patient‐reported disease burden in adults with atopic dermatitis. JAMA Dermatol 2018; 154: 903–912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Silverberg JI, Gelfand JM, Margolis DJ et al. Symptoms and diagnosis of anxiety and depression in atopic dermatitis in U.S. adults. Br J Dermatol 2019; 181: 554–565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. de Bruin‐Weller M, Gadkari A, Auziere S et al. The patient‐reported disease burden in adults with atopic dermatitis: a cross‐sectional study in Europe and Canada. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2020; 34: 1026–1036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Boguniewicz M, Fonacier L, Guttman‐Yassky E, Ong PY, Silverberg J, Farrar JR. Atopic dermatitis yardstick: practical recommendations for an evolving therapeutic landscape. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2018; 120: 10–22.e12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Thaçi D, Simpson EL, Deleuran M et al. Efficacy and safety of dupilumab monotherapy in adults with moderate‐to‐severe atopic dermatitis: a pooled analysis of two phase 3 randomized trials (LIBERTY AD SOLO 1 and LIBERTY AD SOLO 2). J Dermatol Sci 2019; 94: 266–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Waldman RA, DeWane ME, Sloan B, Grant‐Kels JM. Characterizing dupilumab facial redness: a multi‐institution retrospective medical record review. J Am Acad Dermatol 2020; 82: 230–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Okubo Y, Ho KA, Fifer S, Fujita H, Oki Y, Taguchi Y. Patient and physician preferences for atopic dermatitis injection treatments in Japan. J Dermatolog Treat 2020; 31: 821–830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Simpson EL, Sinclair R, Forman S et al. Efficacy and safety of abrocitinib in adults and adolescents with moderate‐to‐severe atopic dermatitis (JADE MONO‐1): a multicentre, double‐blind, randomised, placebo‐controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2020; 396: 255–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Silverberg JI, Simpson EL, Thyssen JP et al. Efficacy and safety of abrocitinib in patients with moderate‐to‐severe atopic dermatitis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol 2020; 156: 863–873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bieber T, Simpson EL, Silverberg JI. Abrocitinib versus placebo and dupilumab for atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med 2021; 384: 1101–1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Barrett A, Hahn‐Pedersen J, Kragh N, Evans E, Gnanasakthy A. Patient‐reported outcome measures in atopic dermatitis and chronic hand eczema in adults. Patient 2019; 12: 445–459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chalmers JR, Thomas KS, Apfelbacher C et al. Report from the fifth international consensus meeting to harmonize core outcome measures for atopic eczema/dermatitis clinical trials (HOME initiative). Br J Dermatol 2018; 178: e332–e341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Spuls PI, Gerbens LAA, Simpson E et al. Patient‐Oriented Eczema Measure (POEM), a core instrument to measure symptoms in clinical trials: a Harmonising Outcome Measures for Eczema (HOME) statement. Br J Dermatol 2017; 176: 979–984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Finlay AY, Khan GK. Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI)–a simple practical measure for routine clinical use. Clin Exp Dermatol 1994; 19: 210–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Charman CR, Venn AJ, Williams HC. The patient‐oriented eczema measure: development and initial validation of a new tool for measuring atopic eczema severity from the patients' perspective. Arch Dermatol 2004; 140: 1513–1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hall R, Lebwohl MG, Bushmakin AG et al. Development and content validation of pruritus and symptoms assessment for atopic dermatitis (PSAAD) in adolescents and adults with moderate‐to‐severe AD. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb) 2020; 11: 221–233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Severity scoring of atopic dermatitis: the SCORAD index . Consensus Report of the European Task Force on Atopic Dermatitis. Dermatology 1993; 186: 23–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1983; 67: 361–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Herdman M, Gudex C, Lloyd A et al. Development and preliminary testing of the new five‐level version of EQ‐5D (EQ‐5D‐5L). Qual Life Res 2011; 20: 1727–1736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Boeri M, Sutphin J, Hauber B, Cappelleri JC, Romero W, Di Bonaventura M. Quantifying patient preferences for systemic atopic dermatitis treatments using a discrete‐choice experiment. J Dermatolog Treat 2020; 1–10. 10.1080/09546634.2020.1832185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. von Kobyletzki LB, Thomas KS, Schmitt J et al. What factors are important to patients when assessing treatment response: an international cross‐sectional survey. Acta Derm Venereol 2017; 97: 86–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wei W, Anderson P, Gadkari A et al. Extent and consequences of inadequate disease control among adults with a history of moderate to severe atopic dermatitis. J Dermatol 2018; 45: 150–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ronnstad ATM, Halling‐Overgaard AS, Hamann CR, Skov L, Egeberg A, Thyssen JP. Association of atopic dermatitis with depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation in children and adults: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2018; 79: 448–456.e430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Cork MJ, Eckert L, Simpson EL et al. Dupilumab improves patient‐reported symptoms of atopic dermatitis, symptoms of anxiety and depression, and health‐related quality of life in moderate‐to‐severe atopic dermatitis: analysis of pooled data from the randomized trials SOLO 1 and SOLO 2. J Dermatolog Treat 2020; 31: 606–614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Blauvelt A, de Bruin‐Weller M, Gooderham M et al. Long‐term management of moderate‐to‐severe atopic dermatitis with dupilumab and concomitant topical corticosteroids (LIBERTY AD CHRONOS): a 1‐year, randomised, double‐blinded, placebo‐controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2017; 389: 2287–2303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Andreasen TH, Christensen MO, Halling AS, Egeberg A, Thyssen JP. Placebo response in phase 2 and 3 trials of systemic and biological therapies for atopic dermatitis—a systematic review and meta‐analysis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2020; 34: 1143–1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Eichenfield LF, Flohr C, Sidbury R. Efficacy and safety of abrocitinib in combination with topical therapy in adolescents with moderate‐to‐severe atopic dermatitis: results from JADE TEEN. JAMA Dermatol 2021; 157: 1165‐1173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Methods

Table S1. Patient‐reported outcome measures used in this analysis

Table S2. Summary of the use of background topical therapy

Table S3. Proportion of patients achieving <3 points in Patient‐Oriented Eczema Measure—Cochran‐Mantel‐Haenszel (FAS with ≥3 points at baseline, NRI)

Table S4. Proportion of patients achieving ≥1‐point improvement from baseline in PSAAD—Cochran‐Mantel‐Haenszel (FAS with ≥1 point at baseline, NRI)

Table S5. Proportion of patients achieving <2 points in SCORAD sleep loss VAS—Cochran‐Mantel‐Haenszel (FAS with ≥2 points at baseline, NRI)

Table S6. Proportion of patients achieving <8 points in HADS‐Anxiety or HADS‐Depression at weeks 12 and 16 (FAS with ≥8 points at baseline, NRI)

Table S7. Proportion of patients achieving ≥4 points improvement from baseline in Dermatology Life Quality Index—Cochran‐Mantel‐Haenszel (FAS with ≥4 points at baseline, NRI)

Table S8. Least squares mean of change from baseline in EQ‐5D‐5L, index value—mixed‐model repeated measures (FAS, OD)

Table S9. Least squares mean of change from baseline in EQ‐5D‐5L, VAS score—mixed‐model repeated measures (FAS, OD)

Figure S1. JADE COMPARE phase 3 study design

Data Availability Statement

Upon request, and subject to certain criteria, conditions and exceptions (see https://www.pfizer.com/science/clinical‐trials/trial‐data‐and‐results for more information), Pfizer will provide access to individual de‐identified participant data from Pfizer‐sponsored global interventional clinical studies conducted for medicines, vaccines, and medical devices (1) for indications that have been approved in the US and/or EU or (2) in programs that have been terminated (i.e. development for all indications has been discontinued). Pfizer will also consider requests for the protocol, data dictionary, and statistical analysis plan. Data may be requested from Pfizer trials 24 months after study completion. The de‐identified participant data will be made available to researchers whose proposals meet the research criteria and other conditions, and for which an exception does not apply, via a secure portal. To gain access, data requestors must enter into a data access agreement with Pfizer.