Summary

Root hairs (RHs) function in nutrient and water acquisition, root metabolite exudation, soil anchorage and plant–microbe interactions. Longer or more abundant RHs are potential breeding traits for developing crops that are more resource‐use efficient and can improve soil health.

While many genes are known to promote RH elongation, relatively little is known about genes and mechanisms that constrain RH growth.

Here we demonstrate that a DOMAIN OF UNKNOWN FUNCTION 506 (DUF506) protein, AT3G25240, negatively regulates Arabidopsis thaliana RH growth. The AT3G25240 gene is strongly and specifically induced during phosphorus (P)‐limitation. Mutants of this gene, which we call REPRESSOR OF EXCESSIVE ROOT HAIR ELONGATION 1 (RXR1), have much longer RHs, higher phosphate content and seedling biomass, while overexpression of the gene exhibits opposite phenotypes. Co‐immunoprecipitation, pull‐down and bimolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC) analyses reveal that RXR1 physically interacts with a RabD2c GTPase in nucleus, and a rabd2c mutant phenocopies the rxr1 mutant. Furthermore, N‐terminal variable region of RXR1 is crucial for inhibiting RH growth. Overexpression of a Brachypodium distachyon RXR1 homolog results in repression of RH elongation in Brachypodium.

Taken together, our results reveal a novel DUF506‐GTPase module with a prominent role in repression of plant RH elongation especially under P stress.

Keywords: Arabidopsis thaliana, Brachypodium distachyon, domain of unknown function, phosphorus stress, root hair

Introduction

Under phosphorus (P) limiting conditions, plants develop shallower primary/basal roots, longer and more lateral roots, longer root hairs (RHs), or cluster roots to improve P foraging and acquisition (Lynch, 2011; Lambers et al., 2015). RHs alone can contribute 70% or more to the total root surface area and can be responsible for up to 90% of phosphate uptake (Bates & Lynch, 2001; Jungk, 2001; Haling et al., 2013; Tanaka et al., 2014; Miguel et al., 2015). The combination of long RHs and shallow basal roots in the soil’s P‐enriched top layer results in a synergistic effect on P acquisition, and translate into massive increases in biomass in cultivars with both traits (Miguel et al., 2015). Therefore, RHs are potential breeding targets for improving nutrient uptake efficiency in agriculturally important crops (Nestler & Wissuwa, 2016; Rongsawat et al., 2021).

RHs are single cell projections that originate from epidermal cells of roots called trichoblasts. They elongate through a process called tip growth. During tip growth, cell expansion is restricted to the cell apex leading to a cell that is cylindrical in shape (Bascom et al., 2018). RHs development includes RH initiation, tip growth and tip growth termination (Grierson et al., 2014). These steps of RH growth and development are tightly regulated by numerous genes, encoding transcription factors (TFs), and proteins involved in cell wall remodeling, cytoskeletal dynamics and vesicle trafficking. Furthermore, hormones such as auxin, ethylene, jasmonic acid or cytokinin and other signaling molecules including reactive oxygen species (ROS), cytoplasmic calcium ion (Ca2+) and phosphoinositides play pivotal roles in modulating RH development (Pitts et al., 1998; Kusano et al., 2014; Mendrinna & Persson, 2015; Mangano et al., 2017; Kato et al., 2019; Han et al., 2020; Tian et al., 2020; Wendrich et al., 2020).

The genetics and molecular mechanisms of RH development have been extensively studied (Parker et al., 2000; Schiefelbein, 2000; Cho & Cosgrove, 2002; Bruex et al., 2012; Lin et al., 2015; Salazar‐Henao et al., 2016; Hwang et al., 2017), leading to the identification of a number of key genes crucial to this process. RH DEFECTIVE6 (RHD6), a basic helix‐loop‐helix (bHLH) TF, plays central roles in RH development (Masucci & Schiefelbein, 1994). RHD6‐LIKE4 (RSL4), which is functionally conserved in higher plants, regulates expression of various genes involved in RH outgrowth through direct binding to specific cis‐elements (RH elements; RHEs) in their proximal promoter regions, and consequently controls RH elongation (Yi et al., 2010; Datta et al., 2015; Kim & Dolan, 2016). The MYB TF PHOSPHATE STARVATION RESPONSE1 (PHR1) and its homolog PHR1‐LIKE (PHL1), play central roles in the P starvation response of Arabidopsis (Rubio et al., 2001; Bari et al., 2006; Bustos et al., 2010; Rouached et al., 2011; Sun et al., 2016; Barragán‐Rosillo et al., 2021). Overexpression (OX) of PHR1 significantly increases RH length, whereas in the phr1 phl1 double mutant, RHs are much shorter in P‐limiting conditions (Bustos et al., 2010). Conversely, the P‐stress responsive TFs WRKY75 and bHLH32 negatively affect RH growth (Chen et al., 2007; Devaiah et al., 2007). Previous studies have also shown that the phytohormones auxin and ethylene synergistically regulate RH growth and differentiation through upregulation of a similar set of genes (Pitts et al., 1998; Bruex et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2016). Auxin and ethylene reciprocally influence each other’s biosynthesis and distribution, suggesting that complex interactions contribute to developmental outcomes (Růžička et al., 2007; Stepanova et al., 2007). Two models illustrate the roles of auxin and ethylene in the modulation of RH elongation when exposed to low external P (Song et al., 2016; Bhosale et al., 2018). For instance, in P‐limiting conditions, the endogenous auxin level is significantly elevated in the root apex, which leads to activation of AUX1‐mediated auxin transport and following the induction of ARF19, eventually stimulating RSL2 and RSL4 to enhance RH elongation (Bhosale et al., 2018). In parallel, ethylene promotes RH growth through transcriptional complexes consisting of EIN3/EIL1 and RHD6/RSL1 as the key regulators of RH initiation and elongation (Feng et al., 2017).

Genetic factors that limit the rate of RH elongation and balance the stimulating effect of auxin, ethylene and RSL2/RSL4 are less well known. Only few genes involved in termination of RH growth have been identified (Hwang et al., 2016; Shibata & Sugimoto, 2019). Here we show that P‐limitation strongly induces a gene encoding a domain of unknown function 506 (DUF506) protein and that it is a strong repressor of RH growth. OX or knockout of the gene results in strong inhibition or stimulation of RH elongation growth, respectively. The gene and its response to P‐limitation is conserved in monocot and dicot species. Moreover, the function of DUF506 in RH elongation growth is conserved in Brachypodium distachyon, suggesting that knockout or knockdown of DUF506 may be applied to promote RH growth in species of economic value.

Materials and Methods

Plant material, growth and treatment

Arabidopsis thaliana (ecotype Col‐0) seeds were sterilized according to Ying et al. (2012) and placed on half‐strength Murashige and Skoog (MS) medium ± phosphate (Caisson Labs, Smithfield, UT, USA), supplemented with 1% (w/v) sucrose, 0.5 mM MES‐KOH (pH 5.7) and solidified with 0.4% (w/v) Gelzan™ CM (MilliporeSigma, Burlington, MA, USA). The plated seeds were stratified for 3 d at 4°C in the dark before placing the plates vertically in a growth chamber (22°C, 120 µmol−2s−1 light intensity, 16 h : 8 h, light : dark cycle). Macronutrient deprivation treatments were done as described previously (Scheible et al., 2004; Bläsing et al., 2005; Morcuende et al., 2007; Bielecka et al., 2015). Plant materials were harvested by rinsing twice in demineralized water, gently blotting on tissue paper and snap‐freezing in liquid nitrogen (N2) before storage at −80°C until further use. The rxr1 (SALK_048882) and rabd2c (SALK_054626) T‐DNA insertion mutant lines were obtained from ABRC. Homozygous mutant plants were identified using the protocol available at http://signal.salk.edu/.

Identification and phylogenetic analysis of DUF506 proteins

To identify DUF506 proteins from different plant species, a Blastp search was conducted on the Phytozome v.12.1.6 website using the RXR1 domain 3 signature peptide (Fig. 2) as query sequence. DUF506 protein sequences with low E value (< 0.001) were downloaded and aligned using the Muscle algorithm with the Mega X software (Kumar et al., 2018). Sequence alignment was grayscale colored according to sequence conservation. Phylogenetic rooted tree was constructed with Mega X software by using the UPGMA (unweighted pair group method with arithmetic mean) algorithm with the default settings. Bootstrapping was performed 1000 times. The inferred trees were visualized using iTOL (Letunic & Bork, 2021).

Fig. 2.

Structure, conservation, phylogeny and distribution of domain of unknown function 506 (DUF506) proteins in plants. (a) Graphical depiction of the general one‐dimensional structure of DUF506 proteins. (b) Sequences of the conserved motifs (1, 2) and domain (3) in the 13 Arabidopsis DUF506 proteins. (c) Number of DUF506 proteins found in 15 plant species as well as the green algae Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. (d) Rooted phylogenetic tree of DUF506 proteins from Arabidopsis thaliana (red), Medicago truncatula (blue), Brachypodium distachyon (green) and Setaria viridis (black). UPGMA (unweighted pair group method with arithmetic mean) tree inferred from the MUSCLE alignment (Bootstrap, 1000 repetitions). The green algae Chlamydomonas reinhardtii DUF506 protein (Cre15.g634750, purple) was used to root the tree. The higher the bootstrap value for a particular branch, the higher the size of the blue circle. (e) Induction of At3g25240 transcript and its closest homologs from Brachypodium distachyon (Bradi2g58590), Medicago truncatula (Medtr7g053310), Panicum virgatum (Pavir.8KG231400), Setaria viridis (Sevir.5G431800) and Triticum aestivum (TraesCS3B02G600900) during phosphorus (P)‐limitation in shoots and roots. The levels of induction are not expected to be quantitatively comparable as results from the different species originate from different experiments.

Quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction

Total RNA was isolated using the RNeasy® plant mini kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized from 1 µg of DNase‐treated RNA using SuperScript™ III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT‐PCR) was performed using an Applied Biosystems (Bedford, MA, USA) 7900HT real‐time PCR system. Gene‐specific primers were designed using PrimerQuest software and their sequences are listed in Supporting Information Table S1. Results were analyzed with Sds software v.2.4 (Applied Biosystems). The Arabidopsis GAPDH (At1g13440) gene was used as reference. Experiments were repeated at least three times using cDNAs prepared from independent biological replicates.

Measurements of root hair length

Seedlings were germinated vertically for 3 d on half‐strength MS plates containing 0.4% Gelzan™ CM, and then transferred to plates containing either 0 (−P) or 675 µM (+P) phosphorus, 10 or 100 nM IAA (indole‐3‐acetic acid; MilliporeSigma), 100 nM or 1 µM ACC (1‐aminocyclopropanecarboxylic acid; MilliporeSigma). Three days after transfer, RH images were captured using a Nikon SMZ1500 fluorescence stereomicroscope (Tokyo, Japan). RH length was determined by an automatic measurement system in Matlab (Notes S1). At least 700 RHs, located 2–6 mm from the tip of the primary root of 8–10 individual plants from each line or condition, were measured. The correctness of automatic measurements was checked by comparison to manual measurements of 50 randomly selected RHs.

Generation of overexpresser and complementation lines

Full‐length (FL) coding regions of At3g25240/RXR1 or Bdi2g58590 were amplified from Arabidopsis and Brachypodium seedling cDNA, respectively, using Phusion® High‐Fidelity DNA polymerase and cloned into GATEWAY® entry vector pENTR™/SD/D‐TOPO® (Invitrogen). Sequence‐confirmed vector was used for recombination into destination vector pMDC83 (Curtis & Grossniklaus, 2003) or pANIC6B (Mann et al., 2012). For rxr1 complementation, a 1461 bp PCR fragment containing the RXR1 promoter and coding region was amplified and ligated into destination vector pMU64 which is based on pPZP200 (Hajdukiewicz et al., 1994). For rabd2c complementation, a 233‐bp promoter fragment of the RabD2c gene and its 609‐bp coding region were fused into pMU64 via Gibson assembly strategy (Gibson et al., 2009). For histochemical β‐glucuronidase (GUS) analysis, a 588‐bp promoter fragment of RXR1 was amplified from Arabidopsis genomic DNA and cloned into vector pBGWFS7 (Karimi et al., 2002). For calcium oscillation analysis, the UBQ10::GCAMP3 construct was transformed into rxr1 mutant (Kwon et al., 2018). Constructs were introduced into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101 (for Arabidopsis) or AGL1 (for Brachypodium) using a freeze–thaw procedure and were transformed into Arabidopsis (Col‐0, and mutants) by floral dipping (Zhang et al., 2006), or Brachypodium (BD21‐3) by embryogenic calli infection (Alves et al., 2009). Transformants were selected on 0.8% (w/v) agar plates containing half‐strength MS medium and 25 µg ml−1 hygromycin (Omega Scientific, Tarzana, CA, USA).

Histochemical β‐glucuronidase (GUS) staining and green fluorescent protein (GFP) imaging

GUS activity was analyzed according to Jefferson et al. (1987). Briefly, tissues were incubated in a GUS staining solution containing 100 mM sodium phosphate (pH 7.0), 1 mM EDTA, 0.05% (v/v) Triton X‐100, 1 mM potassium ferricyanide/ferrocyanide, and 0.5 mg ml−1 X‐glucuronide (Goldbio, Ann Arbor, MI, USA) at 37°C for 1 to 3 h. After removal of the staining solution, tissues were cleared in 70% (v/v) ethanol. Images were acquired using Nikon SMZ1500 stereomicroscope. Green fluorescent protein (GFP) fluorescence in pRXR1::RXR1‐GFP plants was detected and imaged with a Leica TCS SP8 confocal laser‐scanning microscope (excitation (Ex): 488 nm; emission (Em): 507 nm). Propidium iodide (PI, 1 µg ml−1) was applied to visualize the cell shape.

ATH1 gene‐chip expression analysis

Seven‐day‐old Arabidopsis root tissues were conducted to microarray analysis as described previously (Raman et al., 2019). Two biological replicates were performed for each sample. Total RNA was isolated using RNeasy® plant mini kit, quantified and evaluated for purity using a Nanodrop Spectrophotometer ND‐100 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and Bioanalyzer 2100 (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Briefly, 100 ng of total RNA was used for the expression analysis of each sample using the Affymetrix Gene Chip® Arabidopsis Genome ATH1 Array (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA, USA).

Co‐immunoprecipitation (Co‐IP)

Co‐immunoprecipitation experiments were performed using the GFP‐Trap®_M kit (ChromoTek, Planegg, Germany). Proteins were extracted by grinding roots of 10‐d‐old Arabidopsis seedlings expressing pCAMV35S::GFP or pRXR1::262268845RXR1‐GFP in liquid N2, followed by homogenization of the powdered material in two volumes of ice‐cold buffer containing 25 mM HEPES‐KOH (pH 7.5), 1 mM EGTA, 1 mM EDTA, 20% (v/v) glycerol, 10 mM MgCl2, 25 mM NaF, 0.1% (v/v) Triton X‐100, 0.1% (w/v) polyvinylpolypyrrolidone, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF, MilliporeSigma), and 10 µg ml‐1 cOmplete™ EDTA‐free protease inhibitor cocktail (MilliporeSigma). Homogenates were centrifuged at 4°C and 16 000 g for 10 min, and the supernatant re‐centrifuged for 5 min and filtered through a layer of Miracloth (MilliporeSigma). Clarified extracts were incubated with pre‐washed GFP‐Trap®_M magnetic beads on an end‐to‐end tube rotator at 4°C for 1 h, and the beads subsequently washed according to manufacturer instructions. Bound protein was eluted with 200 mM glycine (pH 2.5) and immediately neutralized with 1 M Tris (pH 10.4). Composition of the eluates was analyzed by liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC–MS) at the Charles W. Gehrke Proteomics Center (University of Missouri, Columbia, MO, USA).

Bimolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC) assay

The bimolecular fluorescence complementation analysis was performed as previously described (Waadt et al., 2014; Kudla & Bock, 2016). Briefly, FL or truncated RXR1 was fused to the N‐terminal EYFP in the pSITE‐nEYFP vector, whereas RabD2c were fused with the C‐terminal part of EYFP in pSITE‐cEYFP. These vectors were co‐transformed into Nicotiana benthamiana through agro‐infiltration (Li, 2011). Forty‐eight hours after infiltration, fluorescence was detected and imaged using a Leica TCS SP8 confocal laser‐scanning microscope (Ex: 514 nm; Em: 527 nm).

Pull‐down assays and Western blotting

For heterologous expression of RXR1, its FL cDNA was sub‐cloned into pMAL™‐c5X vector (NEB, Ipswich, MA, USA) carrying an N‐terminal MBP (maltose binding protein) tag. A C‐terminally truncated (residues 1–165; 1–165) and two N‐terminally truncated (residues 127–245; and residues 166–245) RXR1 versions were also constructed and sub‐cloned into the pMAL™‐c5X vector. For recombinant protein production, constructs were separately introduced into the Escherichia coli (Express Competent cells C2523H; NEB). The purification was performed using amylose resin (NEB) according to the manufacture’s instruction. Protein concentration was quantified using Pierce™ rapid gold BCA protein assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and finally stored in −80°C. For the generation of His6‐RabD2c, FL cDNA of RabD2c were ligated into a pRSETA vector (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The proteins were heterologously expressed in E. coli (One Shot® BL21 DE3 pLysS cells, Thermo Fisher Scientific), purified using Ni‐NTA Agarose (Qiagen) and stored in −80°C.

For semi in vivo pull‐down assays, the proteins were extracted from 10‐d‐old Arabidopsis pRXR1::RXR1‐GFP seedling root tissue as described earlier. Protein extract (1 mg) was incubated with His6‐RabD2c (1 μg) and Ni‐NTA agarose for 1 h at 4°C. The beads were washed three times with phosphate buffered saline (PBS; MilliporeSigma). Proteins bound to beads were dissociated by incubation in 100 μl of Novex™ Tris‐glycine sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) sample buffer (2×, Thermo Fisher Scientific) at 85°C for 2 min. Proteins were separated by Novex™ 10–20% Tris‐glycine gel (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and transferred to an Immobilon‐P PVDF membrane (0.45 μM; MilliporeSigma). Western blotting was performed using 5000‐fold diluted monoclonal mouse anti‐GFP antibody conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (HRP) (Meltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA, USA), and was visualized using the ECL™ Prime Western Blotting System (MilliporeSigma).

For in vitro pull‐down assays, His6‐RabD2c (1 μg) was pretreated at 22°C for 15 min in 200 μl of PBS buffer containing 1 mM of GTP‐γ‐S or GDP (MilliporeSigma), before incubation with Ni‐NTA agarose for 30 min at 4°C. Then the mixture was incubated with MBP‐RXR1 or its truncated versions (1 μg) on a rotator for another 2 h at 4°C. The resin was washed five times with PBS, and bound proteins were denatured, separated and transferred as described earlier. Western blotting was performed using 5000‐fold diluted monoclonal mouse anti‐MBP antibody conjugated to HRP (MiltenyiBiotec).

In vitro GTPase activity assay

The assay was performed as described in Pan et al. (2006). Inorganic phosphate released by GTPase activity was quantified using the EnzChek Phosphate Assay Kit (Invitrogen) by measuring the increase in absorbance at λ = 360 nm (A 360) caused by production of 2‐amino‐6‐mercapto‐7‐methylpurine. All assays were replicated at least three times and representative results are shown.

Graphs and statistical analysis

Graphs were produced and statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 9 (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA).

Accession numbers

Sequence data from this article can be found in the Phytozome 12 online genomic resource under the following accession numbers: AtRXR1 (At3g25240), AtRabD2c (At4g17530), Arabidopsis DUF506 gene family members (At1g12030, At1g62420, At1g77145, At1g77160, At2g20670, At2g38820, At2g39650, At3g07350, At3g22970, At3g54550, At4g14620 and At4g32480), AtRXR1 closest homologs Bradi2g58590, Medtr7g053310, Pavir.8KG231400, Sevir.5G431800 and TraesCS3B02G600900.

Results

Expression of AT3G25240 is strongly and specifically induced by P‐limitation

AT3G25240 is a member of a gene family encoding proteins containing DUF506. In an RNA‐sequencing (RNA‐Seq) dataset from P‐limited Arabidopsis, we found that the AT3G25240 transcript was strongly upregulated (Fig. S1; Methods S1). The strong induction of AT3G25240 during P‐limitation was confirmed by qRT‐PCR experiments, which showed that transcript levels increased nearly 1000‐fold following P deprivation and decreased after P re‐addition to liquid culture‐grown Arabidopsis seedlings (Fig. 1a,b), indicating a direct response of this gene to plant P‐status. AT3G25240 transcript abundance was inversely correlated with media P concentration (Fig. 1c), and induction during P‐limitation was attenuated in phr1 and phr1 phl1 double mutants (Fig. 1d), indicating dependence on these major transcriptional regulators of P‐starvation responses. Consistent with this observation, three PHR1‐binding sites (P1BS) are present in the AT3G25240 promoter (Fig. S2a). In contrast, to the P‐limitation response, the response of AT3G25240 transcript to sulfur, nitrogen or sugar limitation was minor (Fig. 1e). Strong induction of GUS activity during P‐limitation in cotyledons and along the main root was detected in Arabidopsis seedlings expressing GUS under control of the AT3G25240 promoter (Fig. S2b), and GFP fluorescence was evident in P‐limited seedlings expressing an AT3G25240‐GFP fusion protein under the control of the endogenous promoter (Fig. 1f–m). The 62 kD fusion protein was easily detected by Western blotting in samples from P‐limited seedlings (Fig. 1f, left panel). A faint signal was also detectable in samples from P‐replete seedlings, but required much longer exposure of the Western blot (Fig. 1f, right panel). To examine whether the weak signal under P‐replete conditions was caused by rapid degradation via proteasome, we incubated seedlings in P‐replete liquid medium containing 50 µM MG‐132 for 6 h. We found the AT3G25240 protein remained undetectable (Fig. S3). During P‐limitation GFP signal in live plants was predominantly and highly visible in nuclei of root cells in the RH‐forming zone, but not, or much less, in the root tip/expansion zone and the mature, differentiated root (Fig. 1g–j). Closer observation further revealed the presence of the GFP signal in nuclei and the cytoplasm of RH‐forming cells (trichoblasts) (Fig. 1k), and in nuclei of differentiated RHs (Fig. 1l,m) and the cytoplasm between the nucleus and RH tip (Fig. 1m).

Fig. 1.

Expression analysis of At3g25240 transcript and protein. (a) Change of At3g25240 transcript abundance, as measured by quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT‐PCR), in phosphorus (P)‐deprived vs P‐replete Arabidopsis seedling shoots (sh) and roots (ro). (b) Change of At3g25240 transcript abundance in liquid culture grown Arabidopsis seedlings during a P deprivation/re‐addition time course; 3R indicates a 3 h re‐addition of 675 µM phosphate. (c) At3g25240 transcript abundance in Arabidopsis seedlings grown on agar plates with various phosphate concentrations [Pi]. (d) At3g25240 transcript abundance in P‐deprived wild‐type (WT), phr1 mutant or phr1 phl1 double mutant seedlings, relative to seedlings grown in P‐replete conditions. (e) At3g25240 transcript abundance in P‐, nitrogen (N)‐, sulfur (S)‐ or carbon (C)‐deprived Arabidopsis seedlings. (a–e) Error bars indicate SD (n = 3). (f) Western blot analysis of P‐status dependent abundance of DUF506‐GFP fusion protein expressed under control of the endogenous promoter. Coomassie‐stained RuBisCO protein is shown as loading control. Short exposure time (1 min, left panel) easily reveals DUF506‐GFP in extracts from P‐limited (−P) seedlings. Longer exposure time (20 min; right panel) also reveals low DUF506‐GFP protein (marked with red arrowhead) in P‐sufficient (+P) conditions. (g–m) Detection of green fluorescent protein (GFP) signal in roots of Arabidopsis plantlets expressing pAt3g25240::At3g25240‐GFP. (g) Absence and (h) nuclear/cytosolic presence of GFP signal (excitation (Ex): 488 nm; emission (Em): 507 nm) in main root under +P and –P conditions, respectively. Bar, 50 µm. (i, j) GFP signal in the root hair (RH) forming zone of the main root. (k) GFP signal in RH forming trichoblasts, (l, m) GFP signal in RH nuclei and in the cytoplasm at the RH tip. Bars: (g, h, k–m) 20 µm; (i, j) 100 µm.

Occurrence of DUF506 family in plants

Genes encoding DUF506 proteins are present in monocot and dicot plants species and in green algae, e.g. Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, (Fig. 2c), but not in animals. DUF506 proteins harbor two highly conserved 9 and 11 amino acid (aa) motifs (M1, M2) and a conserved c. 80 aa domain (D3) in the C‐terminal half, as well as two variable regions at the N‐ and C‐termini (Fig. 2a,b). A phylogenetic tree constructed using DUF506 protein sequences from Arabidopsis thaliana, Medicago truncatula, Setaria viridis and B. distachyon (Fig. 2d) shows clearly defined, higher order branches containing proteins from all four species and sub‐branches that reflect the monocot/dicot divide. The response to P‐limitation of related DUF506 protein‐coding transcripts from different plant species is conserved as well (Fig. 2e).

AT3G25240/RXR1 represses root hair elongation

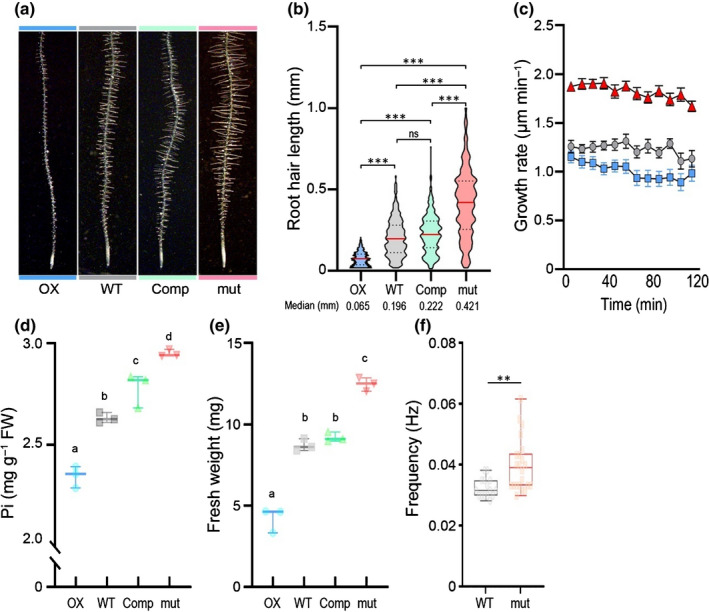

To explore the biological function(s) of AT3G25240, OX lines were generated and a homozygous transfer DNA (T‐DNA) mutant was isolated (Fig. S4). A construct expressing AT3G25240‐GFP under control of the AT3G25240 gene promoter (Fig. 1f–m) was introduced into the T‐DNA mutant for complementation, biochemical and subcellular analysis. Roots of 6‐d‐old OX seedlings displayed shorter RHs while mutant roots had longer RHs when compared to wild‐type (Figs 3a, S5). Mutant seedlings expressing AT3G25240‐GFP had RHs comparable in length to the wild‐type, indicating functional complementation, thus linking AT3G25240 to the long RH phenotype. Quantification of RH length distribution revealed that OX RHs were shorter than 200 µm, with a median length of 65 µm (Fig. 3b). Wild‐type RHs ranged from < 50 µm to sometimes up to 600 µm, with a median length of 196 µm. RHs of the mutant, subsequently named rxr1 ( repressor of excessive root hair elongation 1), were rarely < 100 µm, but c. 17% were longer than 600 µm. The rxr1 median RH length was 421 µm, i.e. more than twice that of wild‐type. The RH‐length distribution plot of the complemented rxr1 mutant was comparable to wild‐type. We further investigated RH growth rates for rxr1 mutant, OX and wild‐type in a single blind study (Fig. 3c). Such analyses revealed that mutant RHs elongate c. 50% faster and OX RHs c. 25% slower than wild‐type RHs. Furthermore, considering that RH tip cytoplasmic Ca2+ dynamics have reported to positively correlate to RH polar growth (Brost et al., 2019), we monitored the [Ca2+] oscillations frequency by transforming wild‐type and rxr1 mutants with the pUBQ10::GCAMP3 construct. The faster RH growth of rxr1 mutant was accompanied by a c. 25% higher frequency of cytosolic [Ca2+] oscillations when compared to that of wild‐type (Fig. 3f).

Fig. 3.

Effect of RXR1/At3g25240 overexpression or knockout on Arabidopsis root hair (RH) growth, phosphate content, biomass and frequency of [Ca2+] oscillations. Three‐day‐old seedlings were transferred to half‐strength MS agar (0.8% w/v) medium containing sufficient phosphate (675 µM), then grew vertically for 2 d (a and b) or 7 d (d and e). (a) Representative images showing the effect of RXR1 on RH elongation. (b) Violin plots of RH lengths in wild‐type (WT), RXR1 overexpression (OX), rxr1 mutant (mut), and complemented rxr1 mutant (Comp). The plot illustrates kernel probability density in which the width represents distribution of data points. Dash lines indicate 25th and 75th percentiles and horizontal red line is the median value. Between 787 and 819 RHs from 10 seedlings were measured for each genotype and numbers at bottom indicate median values (in millimeters) for each genotype. ***P < 0.001 indicates statistical significance as determined by one‐way ANOVA analysis; ns, no significance. (c) Time course of RH growth rate in RXR1 OX (blue), WT (gray) and rxr1 mutant (red). Data represent mean values ± SEM (n = 8). (d, e) Box plots of shoot phosphate (Pi) content (d) or fresh biomass (e) of 10‐d‐old RXR1 OX, WT, rxr1 mutant (mut) and complemented rxr1 mutant (Comp) seedlings (n = 3). Horizontal line is the median and whiskers display minimum and maximum values. Statistical significance of differences was tested by one‐way ANOVA analysis (P < 0.01) and is indicated by lowercase letters. (f) Box plot of [Ca2+] oscillations frequencies in RHs of rxr1 mutant (orange) and WT (gray) over 600 s. Box limits indicate 25th and 75th percentiles, horizontal line is the median, and whiskers display minimum and maximum values. Each semitransparent dot represents individual measurements from 7 to 11 RHs per group from four to six plants. **P < 0.01 indicates statistical significance as determined by Student’s t test.

Given the induction of RXR1 during P‐limitation and the importance of RHs for phosphate uptake (Bates & Lynch, 2001), we checked whether shorter and longer RH length in RXR1 OX and rxr1 mutant correlated with seedling phosphate content. Indeed, RXR1 OX seedlings consistently displayed reduced shoot phosphate and rxr1 mutant increased shoot phosphate contents (Fig. 3d), whereas the complemented mutant had a phosphate content more similar to that of wild‐type. RH length also positively correlated with seedling fresh weight. For instance, rxr1 mutant seedlings were 35% heavier than wild‐type seedlings, whereas RXR1 OX seedlings had a biomass only 50% that of wild‐type (Figs 3e, S6). This suggests that longer RHs not only enable higher phosphate acquisition but also that higher phosphate acquisition results in better growth.

Previous studies have demonstrated the risk of unexpected phosphate contamination in different batches of agar, which might lead to mistaken interpretations of phenotypes (Jain et al., 2009). Thus, we used 0.4% Gelzan (w/v) instead of 0.8% agar (w/v) as gelling agent to re‐examine those RH, phosphate content and aboveground growth phenotype, especially under P‐deficient condition. The RH length, as well as the phosphate content and biomass, exhibited similar results as those observed in seedlings grown on agar plates. However, differences among genotypes were not as dramatic as those grown on agar plates. For instance, RH median length of rxr1 mutant was 316 µm, which was 25% shorter than growing on P‐replete agar plates (Fig. 4a). Under P‐deprived conditions, the RH lengths of all genotypes were c. 20% longer than P‐replete seedlings. Nevertheless, the shorter or longer RH phenotypes of RXR1 OX or rxr1 mutant were consistent with what was observed on agar plates (Fig. 4b). phosphate content and biomass of rxr1 mutant also showed significant elevation under both P‐replete or deprived condition (Fig. 4c,d).

Fig. 4.

Effect of RXR1 overexpresser or knockout on Arabidopsis root hair (RH) growth, phosphate content and biomass under phosphate deficient condition. Three‐day‐old seedlings were transferred to half‐strength MS Gelzan (0.4% w/v) medium containing sufficient (675 µM) or deficient (0 µM) phosphate, then grew vertically for 2 d (a, b) or 7 d (c, d). (a) Representative images showing the effect of RXR1 on RH elongation under phosphate sufficient (top panel) or deficient (bottom panel) condition. (b) Violin plots of RH lengths in wild‐type (WT), RXR1 overexpression (OX) and rxr1 mutant (rxr1). The plot illustrates kernel probability density in which the width represents distribution of data points. Dash lines indicate 25th and 75th percentiles and horizontal black line is the median value. Between 1206 and 1332 RHs from 10 seedlings were measured for each genotype and numbers at bottom indicate median values (in millimeters) for each genotype. ***P < 0.001 indicates statistical significance as determined by one‐way ANOVA analysis. (c, d) Box plots of shoot phosphate (Pi) content (c) or fresh biomass (d) of 10‐d‐old RXR1 OX, WT and rxr1 mutant (rxr1) seedlings (n = 3). Horizontal line is the median and whiskers display minimum and maximum values. Statistical significance of differences was tested by one‐way ANOVA analysis (P < 0.01) and is indicated by lowercase letters.

Hydroponic system, as an alternative, was recommended for dissecting morphophysiological and molecular responses of Arabidopsis to different nutrient deficiencies (Jain et al., 2009). Recently, another solid‐phase buffered P system was proven to simulate the soil grow condition for studying P‐starvation response of plants (Hanlon et al., 2018). Thus, we employed both of the aforementioned systems to verify the RXR1‐related RH phenotype. Irrespective of P supply or the nature of the medium, the rxr1 mutant showed the long RH phenotype, while RXR1 OX RHs were consistently the shortest, and virtually absent in liquid medium (Fig. S7). Taken together, our results suggested that RXR1 functions as a repressor to inhibit RH elongation, regardless of P‐status.

Repression of root hair‐specific gene transcripts in RXR1 overexpressers

Due to the nuclear localization of RXR1, gene‐chip transcript profiling was performed with RXR1 OX, wild‐type and rxr1 mutant roots. Although the transcriptional changes in RXR1 OX and rxr1 mutant roots compared to wild‐type roots were overall minor, a set of more than 20 root hair specific (RHS) gene transcripts were found to be slightly (c. two‐fold) repressed in RXR1 OX root samples (Fig. 5; Table S2). No induction of these gene transcripts was found in rxr1 mutant roots. By contrast, previous gene‐chip profiling of RSL4 OX roots, which had with long RHs, showed two‐ to three‐fold induction of many of these transcripts (Yi et al., 2010).

Fig. 5.

Relative abundance of Arabidopsis root hair (RH)‐specific gene transcripts in rxr1 mutant and RXR1 overexpression (OX). Fold induction of gene transcript abundances (rxr1 mutant vs wild‐type, and RXR1 OX vs wild‐type) are plotted against each other for ATH1 gene chip data (left panel, blue symbols) and quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT‐PCR) data (right panel, red symbols). Note that a ‘fold induction’ of e.g. 0.5 equals a two‐fold decrease. Data for the depicted RH‐specific gene transcripts are also in Supporting Information Table S2, along with references.

When re‐examined by qRT‐PCR, the repression of the gene transcripts in RXR1 OX root samples was confirmed, and c. two‐fold induction of a few of the RHS gene transcripts (PER7, RHS15, IRT2, At3g07070, At5g04960) was observed in rxr1 root samples (Fig. 5). In comparison, RSL4 OX roots show c. 10‐fold induction of PER7 when examined with qRT‐PCR (Yi et al., 2010). Collectively, the results show that RXR1, despite having longer RHs, only mildly affects expression of RH‐specific gene transcripts. This suggest that RXR1 participates in other pathways rather than having a predominant function as a transcriptional regulator to control RH growth.

RXR1 affects root hair elongation independently of auxin or ethylene

Auxin and ethylene are plant hormones known for their role in RH development and elongation under P‐limitation (Nacry et al., 2005; Song et al., 2016; Feng et al., 2017; Bhosale et al., 2018). The qRT‐PCR analyses indicated that expression of RXR1 gene was not affect by IAA/auxin or ACC/ethylene treatment (Fig. 6e). To further test whether RXR1 and auxin (IAA) interact during RH elongation, RXR1 OX, wild‐type and rxr1 mutant were grown in ±100 nM IAA medium (Fig. 6a,b; also cf. Fig. S8a for ±10 nM IAA). In all three genotypes, 100 nM IAA significantly stimulated median RH length by 160–170 µm (Fig. 6b). Moreover, when growing on P‐deprived medium supplemented with auxin transporting inhibitor (NPA) or biosynthesis inhibitor (Yucasin), OX and rxr1 mutant displayed shorter and longer RHs, respectively (Fig. S8b). This observation indicates that loss or OX of RXR1 does not affect auxin sensitivity or perception.

Fig. 6.

Effect of auxin and ethylene on Arabidopsis root hair (RH) growth of RXR1 overexpressers and rxr1 mutant. (a, c) Representative images showing the effect of 100 nM indole‐3‐acetic acid (IAA) (a) or 1 µM 1‐aminocyclopropanecarboxylic acid (ACC) (b) on RH length of RXR1 overexpression (OX), wild‐type (WT) and rxr1 mutant. Bar, 1 mm. (c, d) Violin plots of RH lengths in WT, RXR1 OX and rxr1 mutant (rxr1). Plantlets were grown on 0.4% (w/v) Gelzan medium prepared with nutrient solution containing sufficient (675 µM) and 100 nM IAA (b) or 1 µM ACC (d). The plot illustrates kernel probability density in which the width represents distribution of data points. Dash lines indicate 25th and 75th percentiles and horizontal black line is the median value. Between 571 and 958 RHs from 10 seedlings were measured for each genotype and numbers at bottom indicate median values (in millimeters) for each genotype. ***P < 0.001 indicates statistical significance as determined by one‐way ANOVA analysis. (e) Change of RXR1 transcript abundance, as measured by quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT‐PCR), in the absence of phosphorus (−P), or in the presence of 100 nM IAA or 1 µM ACC. (f) Hypocotyl length of RXR1 OX (blue), WT (gray), and rxr1 mutant (red) in the presence of various ACC concentrations (n = 16). (g) Change of RXR1 transcript abundance, as measured by qRT‐PCR, in P‐deprived vs P‐replete Arabidopsis seedling of WT, rsl4, arf19, aux1, taa1, ein3 and ctr1 mutants. (e, g) Error bars indicate SD (n = 3).

Similar results were obtained with ethylene/ACC (Fig. 6c,d, also cf. Fig. S8a for ±100 nM ACC). Addition of 1 µM ACC to Gelzan plates increased median RH length strongly in OX, wild‐type and rxr1 mutant (261, 229 and 198 µm respectively; Fig. 6c,d). Additionally, OX and rxr1 mutant also did not differ from wild‐type in the classical response of dark‐grown hypocotyls to increasing ACC doses (Fig. 6f).

Lastly, we monitored the expression changes of RXR1 gene transcript in those mutants of well‐characterized auxin or ethylene signaling pathway, such as rsl4, arf19, aux1, or taa1 of auxin pathway, and ein3 or ctr1 of ethylene pathway (Fig. 6g). The induction of RXR1 transcript (−P vs +P) exhibited no conspicuous difference among those in mutant backgrounds. In parallel, the transcript abundancies of those major genes involved in either auxin or ethylene signaling were unaffected in RXR1 OX or mutant (Table S3). Thus, we conclude that RXR1 acts independently of auxin or ethylene in modulating RH elongation.

RXR1 interacts with a Rab GTPase

To identify RXR1‐interacting proteins, two independent immunoprecipitation (IP) experiments followed by mass spectrometry (MS) analysis of tryptic protein digests were conducted using the RXR1‐GFP complemented rxr1 line (cf. Fig. 3). Table 1 summarizes the proteins identified in both experiments (cf. Tables S4, S5 for more details). A Rab GTPase (RabD2c/At4g17530) showed the highest sequence coverage. Because of the known roles of Rab GTPases in directional growth processes (Preuss et al., 2004; Szumlanski & Nielsen, 2009; Peng et al., 2011), the interaction of RXR1 and RabD2c was investigated further in vitro and in vivo (Fig. 7). GFP‐tagged RXR1 protein, expressed under its native promoter, was successfully immunoprecipitated in samples generated from P–limited seedlings using recombinant His6‐tagged RabD2C protein (Fig. 7a). Similar to previous results (Fig. 1f), no RXR1‐GFP protein was detectable after short (1 min) exposure in samples prepared from P‐sufficient seedlings, nor was GFP itself immunoprecipitated by His6‐tagged RabD2C (Fig. 7a).

Table 1.

RXR1‐interacting proteins.

| AGI | Annotation | Molecular mass (kD) | Unique peptides (IP1/IP2) | Coverage (%) (IP1/IP2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| At1g12000 | Phosphofructokinase | 61 | 3/3 | 8.0/8.1 |

| At1g64440 | UDP‐glucose 4‐epimerase | 38 | 3/2 | 8.9/7.2 |

| At1g74960 | Beta‐ketoacyl‐ACP synthetase 2 | 58 | 2/3 | 3.9/7.0 |

| At1g78850 | Mannose binding lectin 1 | 49 | 1/2 | 3.0/6.6 |

| At2g46520 | Exportin‐2 | 109 | 6/4 | 7.3/5.5 |

| At3g05970 | Long‐chain acyl‐CoA synthetase 6 | 77 | 5/6 | 10.1/12.7 |

| At3g62530 | ARM repeat superfamily protein | 25 | 4/3 | 18.6/16.7 |

| At4g17530 | GTPase homolog RabD2C | 22 | 2/4 | 11.4/30.2 |

| At4g23850 | Long‐chain acyl‐CoA synthetase 4 | 75 | 3/5 | 5.7/7.7 |

| At5g11720 | Alpha‐glucosidase | 101 | 3/4 | 4.0/5.6 |

| At5g42150 | Glutathione S‐transferase | 36 | 2/7 | 5.1/25.7 |

RXR1‐GFP was immunoprecipitated with green fluorescent protein (GFP) antibodies from roots of phosphorus (P)‐limited plants expressing pRXR1:RXR1‐GFP, and co‐precipitated proteins were identified by mass spectrometry. Two independent experiments (IP1, IP2) were performed. Proteins identified in samples from RXR1‐GFP expressing plants in both experiments, but not in samples from plants expressing GFP, are listed. Using Blast‐P, protein identification probability for each protein was 100% in each of the two experiments. AGI, Arabidopsis Gene Identifier. Coverage (in %) is defined as the number of amino acids covered by the identified peptides divided by the total number of amino acids of the protein.

Fig. 7.

Interaction of RXR1 and Rab GTPase/At4g17530. (a) Immuno‐pull down of 62 kD RXR1‐GFP fusion protein expressed under control of the endogenous promoter with His6‐tagged Rab GTPase and Anti‐His antibody (right lane). Crude extract proteins (1 mg) of different genotypes were incubated with recombinant His6‐RabD2c (1 μg) and Ni‐NTA agarose for 1 h at 4°C. Coomassie‐stained RuBisCO protein is shown as loading control. Exposure time of the Western blot after treatment with anti‐GFP antibody conjugated to horseradish peroxidase was 1 min. (b) Immuno‐pull down of maltose binding protein (MBP)‐tagged DUF506 protein with His6‐tagged Rab GTPase and Anti‐His antibody in the presence of GTP but not GDP. (c) Bimolecular fluorescence complementation in Nicotiana benthamiana. Arrows point to nuclei showing yellow fluorescence as a result of full length (RXR1FL) or truncated RXR1 (RXR1166–245) and Rab GTPase (RAB) interaction. Bar, 20 µm. (d) Immuno‐pull down of His6‐tagged Rab GTPase with partial/truncated MBP‐tagged RXR1 proteins and Anti‐MBP antibody. (e) Rab GTPase activity assay in the absence or presence of the four RXR1 protein versions depicted in (d). (f) Representative images showing the root hair (RH) phenotype of wild‐type (WT), rxr1 and rabd2c single mutants, and rxr1 rabd2c double mutant under phosphorus (P)‐sufficient (top panel) or ‐deficient (bottom panel) condition. Bar, 1 mm. (g) Violin plots of RH lengths in WT, rxr1 and rabd2c single mutants, and rxr1 rabd2c double mutant grown on Gelzan plates as described in Fig. 4(a). The plot illustrates kernel probability density in which the width represents distribution of data points. Dash lines indicate 25th and 75th percentiles and horizontal black line is the median value. Between 1032 and 1316 RHs from 10 seedlings were measured for each genotype and numbers at bottom indicate median values (in millimeters) for each genotype. ***P < 0.001, or *P < 0.05 indicates statistical significance as determined by one‐way ANOVA analysis; ns, no significance.

Rab GTPases are active and interact with specific effector proteins in the GTP‐bound state (Stenmark, 2009). Hydrolysis of GTP converts the active back to the inactive conformation and leads to dissociation of the effector protein(s). To test GTP‐dependency of RXR1‐RabD2c interaction, both proteins were produced in bacteria with MBP and His6‐tags, respectively, and incubated together either in the presence of GDP or GTP‐γ‐S (a nonhydrolysable analog of GTP), followed by IP with Anti‐His6 antibody and Western detection with Anti‐MBP antibody. RXR1‐RabD2c interaction was undetectable in the presence of GDP, but was evident with GTP‐γ‐S (Fig. 7b). Considering the three conserved motifs/domains of DUF506 proteins (Fig. 2a), we generated additional three MBP tagged truncated variants of RXR1, to check for in vitro interaction with and activity of RabD2c (Fig. 7d,e). Only the RXR1 domain 3‐containing variants could interact with RabD2c, suggesting that the conserved domain 3 is critical for interaction of RabD2c GTPase.

To elucidate the RXR1 and RabD2c interaction in vivo, we performed BiFC assays by infiltration of RXR1FL, RXR1166–245 (domain 3 only) or RXR11–165 (no conserved domain)‐YFPN and RabD2c‐YFPC into N. benthamiana leaves. Nuclear yellow fluorescence was respectively detected from leaf samples that were introduced with RXR1FL‐RabD2c or RXR1166–245‐RabD2c constructs (Fig. 7c, left and middle), whereas no fluorescence signal was present when RXR11–165‐RabD2c were co‐injected (Fig. 7c, right). The BiFC results confirmed that RXR1 domain 3 mediated the interaction of RabD2c.

Next, we isolated the homozygous T‐DNA mutant of RabD2c, and generated the rxr1 rabd2c double mutant by crossing. Under P‐replete condition, the RH length and distribution of rabd2c and rxr1 rabd2c mutants were similar to those of rxr1 mutant. By contrast, when exposed to P‐limitation, rabd2c mutant exhibited slight but significant (P < 0.05) shorter RH compared to rxr1 or rxr1 rabd2c double mutant (Fig. 7f,g), implicating that beside RabD2c, additional P‐inducible interactor(s) might also simultaneously associate with RXR1 and inhibit RH growth.

To learn more about molecular and functional features of RabD2c gene, we examined the transcript changes against P‐limitation by qRT‐PCR experiments. RabD2c transcript was insensitive to P‐stress and was not regulated by RXR1 (Fig. 8a,b). Additionally, the transcript level of RabD2c was stably expressed in auxin signaling related mutants (Fig. 8c). The RH of rabd2c mutant grew c. 20% faster compared to wild‐type, similar to rxr1 (Fig. 8d). Moreover, endogenous promoter driven RabD2c gene complemented the RH phenotype of rabd2c (Fig. 8f,i), whereas OX of RabD2c could not alter RH growth (Fig. 8g,j). In complemented line, RabD2c was clearly observed in developing or mature RH nucleus (spindle‐shape, white arrow) and apex cytoplasm (Fig. 8e). In order to examine the genetic epistatic relationship between RXR1 and RabD2c, we crossed the RXR1 OX with rabd2c mutant (Figs 8h,k, S9). Relative to rabd2c mutant, significant reduction of RH length was observed in the epistatic over‐expresser (RXR1 OX rabd2c), suggesting that RXR1 dominated the inhibitory function in RXR1‐RabD2c complex.

Fig. 8.

Expression analysis of RabD2c/At4g17530 gene and Arabidopsis root hair (RH) length phenotype of RabD2c transformants. (a–c) Quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT‐PCR) analysis of RabD2c transcripts in response to phosphorus (P)‐deprivation (a), grown on agar plates with various phosphate concentrations [Pi] (b), or in P‐deprived vs P‐replete Arabidopsis seedling of wild‐type (WT), rsl4, arf19, aux1 and taa1 mutants (c). Error bars indicate SD (n = 3). (d) Time course of RH growth rate in WT (gray) and rabd2c mutant (orange). Data represent mean values ± SEM (n = 8). (e) Nuclear (arrows) and cytosolic green fluorescent protein (GFP) signal of RabD2c in primary root, developing or mature RH. Bar, 100 (primary root) or 20 (RH) µm. (f) to (h) Representative images showing the RH phenotype of WT, rabd2c mutant, complemented line (f), RabD2c over‐expresser (g), and RXR1 overexpression in rabd2c mutant (h) under P‐sufficient (top panel) or ‐deficient (bottom panel) condition. Bar, 1 mm. (i–k) Violin plots of RH lengths in WT, rabd2c mutant, complemented line (i), RabD2c overexpresser (j), and RXR1 overexpression in rabd2c mutant (k). The plot illustrates kernel probability density in which the width represents distribution of data points. Dash lines indicate 25th and 75th percentiles and horizontal black line is the median value. Between 787 and 1027 RHs from 10 seedlings were measured for each genotype and numbers at bottom indicate median values (in millimeters) for each genotype. ***P < 0.001 indicates statistical significance as determined by one‐way ANOVA analysis; ns, no significance.

Conserved regions of RXR1 are not sufficient to inhibit root hair elongation growth

Since aas 127–245 of RXR1, comprising the conserved motifs 1/2 and domain 3, were sufficient for interaction with and activity of RabD2c (Fig. 7d,e), their biological function was further investigated by transforming Arabidopsis wild‐type with RXR1127–245‐GFP driven by the CaMV35S promoter. OX of the 46 kD fusion protein (OXΔ) was detected in stably transformed lines (Fig. 9a,b) and localization of RXR1127–245‐GFP in RH nuclei (Fig. 9c) was similar to FL RXR1‐GFP (Fig. 1l,m). However, OX of truncated RXR1127–245 no longer reduced RH elongation growth (Fig. 9d,e), as well as phosphate content and seedling biomass (Fig. 9f,g). Furthermore, when overexpressing RXR1127–245‐GFP in rxr1 mutant (OXΔ rxr1), the long RH phenotype was not compromised (Fig. 9h). These results indicate that elements outside of the conserved motifs/domain of RXR1 are required to repress RH elongation.

Fig. 9.

Overexpression of conserved RXR1 regions do not inhibit Arabidopsis root hair (RH) elongation growth. (a) Construct used for transformation of wild‐type (WT) (d) and rxr1 mutant (h). The conserved motifs and domain that are sufficient for GTPase interaction and activity (cf. Fig. 5) were fused to green fluorescent protein (GFP) driven by the CaMV‐35S promoter (p35S). (b) Western blotting confirms overexpression of RXR1127–245‐GFP fusion protein. (c) Expression of RXR1127–245‐GFP fusion protein in the RH nucleus (arrow). Bar, 50 µm. (d) Representative images showing the RH phenotype of WT and RXR1127–245 overexpression (OXΔ) under phosphorus (P)‐sufficient (top panel) or ‐deficient (bottom panel) condition. Bar, 1 mm. (e) Violin plots of RH lengths in WT and OXΔ grown on Gelzan plates as described in Fig. 4(a). The plot illustrates kernel probability density in which the width represents distribution of data points. Dash lines indicate 25th and 75th percentiles and horizontal black line is the median value. Between 945 and 1047 RHs from 10 seedlings were measured for each genotype and numbers at bottom indicate median values (in millimeters) for each genotype; ns, no significance. Box plots of shoot P content (f) or fresh biomass (g) of 10‐d‐old WT (gray) and OXΔ (blue) seedlings. No statistical differences between WT and OXΔ were revealed for biomass and P content. (h) Representative images showing the RH phenotype of rxr1 mutant (rxr1) and RXR1127–245 overexpresser in rxr1 background (OXΔ/rxr1) grown on Gelzan plates as described in Fig. 4(a). Bar, 1 mm.

A close RXR1 homolog reduces root hair elongation in Brachypodium

AtRXR1 has close P‐limitation induced homologs in other species (Fig. 2e). To test if the closest Brachypodium homolog (Bdi2g58590), besides being P‐limitation induced, also affects RH length, we initially infiltrated a CaMV35S driven Bdi2g58590‐GFP construct into N. benthamiana leaves to examine its subcellular localization. Similar to AtRXR1, Bdi2g58590‐GFP preferentially localized to the nucleus (Fig. 10a). Then, we introduced the maize ubiquitin promoter directed Bdi2g58590 construct into Brachypodium BD21‐3 to generate stable OX lines. The qRT‐PCR analysis indicated the OX led to at least 100‐fold higher expression of Bdi2g58590 (Fig. 10b). Similar to OX of AtRXR1, Bdi2g58590 OX exhibited reduced RH length (Figs 10c, S10), while RH density and main root diameter (Fig. 10d) were not noticeably changed. The RH length and two‐dimensional RH convex envelope of the OX1 line was 50% reduced compared to wild‐type (Fig. 10e,f) suggesting that OX1 roots have a much smaller (< 25%) rhizosphere than the wild‐type. Moreover, the biomass of Bdi2g58590/BdiRXR1 OX plants significantly reduced (Fig. 10g,h). Because of the high similar phenotypes between AtRXR1 and BdiRXR1 OXs, we conclude that Bdi2g58590 and AtRXR1 are orthologous genes.

Fig. 10.

Overexpression of a close RXR1 homolog in Brachypodium distachyon. (a) Syringe‐infiltration of a pCaMV35S::BdiDUF506‐GFP construct into Nicotiana benthamiana leaves results in nuclear (arrow) and partial cytosolic localization of the fusion protein. Bar, 50 µm. (b) Abundance of BdiDUF506 transcript in stable overexpression (OX) lines of Brachypodium distachyon. Error bars indicate SD (n = 3). (c) Representative images showing the root hair (RH) phenotype of Brachypodium wild‐type (BD21‐3) and two stable overexpression lines (OX1 and OX2). Bar, 1 mm. (d) Quantification of main root width. (e) Example for determination of RH convex envelope as defined by the sum of areas between the yellow and cyan lines. The cyan lines are the averages of the magenta lines that connect RH tips. Bar, 1 mm. (f) Relative RH convex envelope area (wild‐type = 100%) for the genotypes shown in (c). (g) Growth aspect of the genotypes shown in (c) at an age of 6 wk, and (h) shoot fresh and dry weights of the genotypes at an age of 8 wk. Data in (d) and (h) represent mean values ± SEM (n = 10). Statistical significance of differences was tested by one‐way ANOVA analysis (P < 0.01) and is indicated by lowercase letters.

Discussion

In this work, we identified the P‐limitation specifically induced DUF506‐protein RXR1 and its interacting RabD2c GTPase as repressors of RH elongation in Arabidopsis (cf. Fig. 11) as well as B. distachyon. By doing so, we attributed biological functions to the first DUF506‐protein coding genes as well as a not well characterized Rab GTPase. RXR1 gene was chosen for research because of its transcriptional response to P‐limitation, the presence of potential orthologs in dicot and monocot plant species (Fig. 2c,d), and the general lack of information for the DUF506 gene family.

Fig. 11.

Working model for molecular function of RXR1/RabD2c in plants. RXR1/RabD2c is a novel module that represses root hair (RH) elongation independently of the stimulating effect of the phytohormone auxin and its downstream signaling pathway (Bhosale et al., 2018). When environmental phosphorus (P) nutrient is limiting, PHR1/PHL1‐dependent RXR1 expression and protein strongly increase. RXR1 interacts with GTP‐bound RabD2c through its conserved DUF506 domain (indicated in dark gray), whereas RXR1‐specific sequences (in light gray) are required to inhibit RH elongation growth. Biochemical and co‐localization evidence further suggest RXR1 might interact with UGE4, through RXR1‐specific sequences. RXR1 interaction with other proteins may modulate additional P‐limitation responses. Solid line, experimentally supported; broken line, hypothetical. Blunt‐ended line, inhibition; arrow, activation.

Rab GTPases are well‐known for intracellular vesicle trafficking and the contribution of RabA GTPases to polar‐tip cell wall deposition, that significantly influence elongation of pollen tubes and RHs, have been comprehensively investigated (Preuss et al., 2004; Blanco et al., 2009; Szumlanski & Nielsen, 2009; Ovečka et al., 2010; Berson et al., 2014). The discovered interaction of RXR1 and RabD2c spurred subsequent work because RabD2c GTPases are known to affect pollen tube tip growth (Szumlanski & Nielsen, 2009; Peng et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2012). Pollen tubes and RHs are similar in terms of their highly polarized ‘tip growth’ where cell expansion occurs at the very apex of the cell, and is supported by a tip‐focused delivery of membrane and cell wall components (Szumlanski & Nielsen, 2009). It was proposed that members of the RabD2 subclades provided overlapping but functionally distinct activities in Arabidopsis (Pinheiro et al., 2009). For instance, Golgi‐localized RabD2c and its closest homolog RabD2b (At5g47200) were found to have overlapping functions in vesicle trafficking during pollen tube growth (Peng et al., 2011). However, the role for nuclear RabD2c in RH development was unknown until now (Figs 8e, S11).

For the interaction with and activity of RabD2c in the presence of GTP, the conserved DUF506 regions of RXR1, especially domain 3, are required and sufficient (Fig. 7), suggesting that other DUF506 proteins may interact, as so‐called effector proteins (Nielsen, 2020), with Rab GTPases in a GTP‐dependent manner as well. Noteworthy, overexpressing the conserved regions (domains 1, 2 and 3) of RXR1 (i.e. RXR1127–245, OXΔ) in rxr1 mutant could not rescue the long RH phenotype (Fig. 9h), and RXR1 OX in rabd2c mutant led to reduced RH (Fig. 8h,k), hinting that N‐terminal variable sequences are required for RXR1 to repress RH elongation, supposedly through interaction with other proteins.

The extraordinary response of RXR1 transcript to P‐limitation, its dependence on PHR1/PHL1 (Fig. 1), and lack of response to other environmental and developmental factors observed in RNA‐Seq databases such as eFP browser (Winter et al., 2007) or GENEVESTIGATOR, suggests an important and specific role for RXR1 during P‐limitation. However, despite almost undetectable transcript, RXR1 protein is present at a low level and functional in P‐replete conditions, as indicated by the long RHs of P‐fed rxr1 mutants (Figs 1, 3). Given that the RH length displays no difference between rxr1 and rabd2c mutant under P‐replete condition (Fig. 7f,g), it is tempting to speculate that RXR1–RabD2c interaction is sufficient to restrict the RH elongation. Additional unknown interactors which we cannot investigate due to the low protein abundance of RXR1, or post‐translational modification, e.g. SUMOylation by SIZ1 (Miura et al., 2005), might stabilize the association to prevent proteasome mediated degradation. However, more RXR1 protein may be needed during P‐limitation to counteract a strong inducing effect of auxin (Bhosale et al., 2018) and balance RH elongation growth. RXR1 may also possess other biological functions, as suggested by its spatial expression during P‐limitation (Fig. S2) and by the existence and nature of RXR1‐interacting proteins (Table 1). In this context, UGE4, also known as RHD1 (RH Defective1), could co‐localize with FL but not truncated RXR1 in cytoplasm (Fig. S12), which supports the notion that the N‐terminal variable region is indispensable for additional interaction and repressing RH growth.

Here, we substantiate that RXR1 acts as a novel P‐inducible repressor of RH elongation, to retain the homeostasis of RH growth and energy consumption under P‐deficiency. Numerous genes affecting RH initiation, growth and shape have been identified in Arabidopsis (Salazar‐Henao et al., 2016; Shibata & Sugimoto, 2019) and other species (Marzec et al., 2015; Kim & Dolan, 2016; Kim et al., 2017). However, mutations in relatively few genes, such as PCaP2 (Kato et al., 2019), Lotus japonicas ROOT HAIRLESS LIKE4/5 (LRL4/5) (Breuninger et al., 2016), RHS10 (Won et al., 2009), GT‐2‐LIKE1 (GTL1) and its homolog DF1 (Shibata et al., 2018) resulted in longer RHs. Similar to rxr1 and rabd2c RHs, pcap2 RHs elongate at a higher rate, resulting in RHs that are c. 50% longer than wild‐type RHs (Kato et al., 2019). RHS10 was identified in silico as gene harboring RH‐specific cis‐elements in its promoter (Won et al., 2009). RHS10 encodes a proline‐rich receptor‐like kinase that localizes to the plasma membrane and exhibits association with RH cell walls (Hwang et al., 2016), which is very different to RXR1’s localization. Moreover, rhs10 mutant RHs elongate at the same rate as wild‐type RHs, but the tip‐growing period is extended, resulting in c. 35% longer RHs, whereas rxr1 and rabd2c RHs elongate faster and ultimately are 75 to > 100% longer than wild‐type RHs (Figs 3b, 7g). Furthermore, auxin or ethylene do not rescue RHS10‐inhibited RH growth (Hwang et al., 2016), but they still function in rxr1 mutant and RXR1 OX, again indicating a mechanistic difference. The trihelix TFs GTL1 and DF1 repress RH growth by direct binding to the RSL4 promoter (Shibata et al., 2018). Similar to rhs10 or RSL4 OX (Yi et al., 2010; Hwang et al., 2016), but in contrast to rxr1, rabd2c or pcap2, gtl1 df1 double mutant RHs also elongate at the same rate as wild‐type RHs, but their tip‐growing period is prolonged, resulting in c. 50% longer RHs. In summary, these results suggest that RHS10, GTL1 and DF1 are involved in termination of the tip‐growth process, while RXR1/RabD2c and PCaP2 negatively affect the rate of tip‐growth. The phenotypic similarity of rxr1, rabd2c and pcap2 RH growth may indicate a closer connection between RXR1/RabD2c and phosphoinositides, although a general role of RXR1/RabD2c in RH lipid metabolism, vesicle transport and/or peroxisomal energy production is also possible.

Mutants without RHs show reduced phosphate uptake and compromised growth on soils when phosphate availability is limited (Gahoonia et al., 2001; Brown et al., 2012; Tanaka et al., 2014). The same was observed with RXR1 overexpressers in Arabidopsis and Brachypodium, which had substantially shorter RHs, lower phosphate contents and reduced biomass irrespective of medium type or P‐supply (Figs 3, 4, 10). Vice versa, common bean genotypes with longer RHs have significantly higher phosphate acquisition and shoot biomass (Miguel et al., 2015), similar to our results with the Arabidopsis rxr1 mutant (Figs 3, 4). Interestingly, in transgenic Brachypodium lines constitutively overexpressing RSL2 or RSL3 bHLH TFs, there was no consistent relationship between long RHs, increase in phosphate uptake and higher biomass (Zhang et al., 2018). This led to the conclusion that increasing RH length through biotechnology can improve P uptake efficiency only if pleotropic effects, caused by transgene insertions or associated genomic rearrangements, on plant biomass are avoided. Nontransgenic knockout of RXR1 and potential functional homolog(s) may help in this regard, and may prove to be an effective approach to develop crops with longer RHs that are more resource‐use efficient and can improve soil health.

Author contributions

SY and W‐RS conceptualized and designed the research, analyzed and interpreted the data, and wrote the manuscript. SY performed the experimental work. FL measured RH lengths. EBB measured RH growth rates, recorded [Ca2+] oscillations and helped with or supervised some microscopic studies. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Supporting information

Fig. S1 Sashimi plots of selected, highly P‐limitation‐induced Arabidopsis gene transcripts.

Fig. S2 Expression of β‐glucuronidase activity under control of the AT3G25240 promoter.

Fig. S3 Effect of proteasome inhibitor MG132 on RXR1 protein expression.

Fig. S4 Genotypes and their RXR1 expression levels.

Fig. S5 Expression pattern of RXR1‐GFP in RXR1 overexpresser.

Fig. S6 Phenotype of 10‐d‐old Arabidopsis seedlings under P‐sufficient or deficient conditions.

Fig. S7 Robust root hair phenotypes of RXR1 overexpresser or rxr1 mutant in different growth conditions.

Fig. S8 Effect of low dosage auxin or ethylene, and auxin inhibitors on root hair growth.

Fig. S9 Subcellular localization of RXR1 in rabd2c mutant.

Fig. S10 Root hair lengths of Brachypodium genotypes.

Fig. S11 Co‐localization analysis of mCherry‐RabD2c (magenta) and Golgi marker (ST‐GFP, green) in Nicotiana benthamiana.

Fig. S12 Co‐localization analysis and root hair phenotype of uge4 mutant in different growth condition.

Methods S1 RNA‐Seq analysis.

Notes S1 Matlab original code of high‐throughput root hair length measurement.

Table S1 Sequences and purposes of primers used in the study.

Table S2 Relative expression of root‐hair specific genes in root samples of rxr1 mutant and RXR1 overexpresser.

Table S3 Expression of auxin and ethylene signaling‐related genes in root samples of rxr1 mutant and RXR1 overexpresser.

Table S4 Co‐immunoprecipitated proteins and their mass‐spectrometric peptide tags.

Table S5 Prediction of subcellular localization of RXR1‐interacting candidates.

Please note: Wiley Blackwell are not responsible for the content or functionality of any Supporting Information supplied by the authors. Any queries (other than missing material) should be directed to the New Phytologist Central Office.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank colleagues at the Noble Research Institute for their help and support: Dr Wei Liu, Alan Sparks, and Sunhee Oh for providing plasmid vectors, Dr Pooja Pant for sharing RNA‐Seq data, Sylvia Warner and Shulan Zhang for laboratory and glasshouse assistance, Amanda Hammon for plant care, Jianfei Yun and Dr Qingzhen Jiang for providing Brachypodium transformation service, and Stacy Allen and Dr Yuhong Tang for ATH1 transcript profiling service. The authors also thank Dr Michael Udvardi for critical comments on the manuscript, and Dr Brian Mooney (University of Missouri) for mass‐spectrometric services. The work was funded by the Noble Research Institute LLC.

Contributor Information

Sheng Ying, Email: yingshen@msu.edu.

Wolf‐Rüdiger Scheible, Email: tomales@gmx.de.

Data availability

The ATH1 microarray data generated during the current study are available from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) repository (GSE179573). Other data and materials that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- Alves SC, Worland B, Thole V, Snape JW, Bevan MW, Vain P. 2009. A protocol for Agrobacterium‐mediated transformation of Brachypodium distachyon community standard line Bd21. Nature Protocols 4: 638–649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bari R, Datt Pant B, Stitt M, Scheible WR. 2006. PHO2, microRNA399, and PHR1 define a phosphate‐signaling pathway in plants. Plant Physiology 141: 988–999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barragán‐Rosillo AC, Peralta‐Alvarez CA, Ojeda‐Rivera JO, Arzate‐Mejía RG, Recillas‐Targa F, Herrera‐Estrella L. 2021. Genome accessibility dynamics in response to phosphate limitation is controlled by the PHR1 family of transcription factors in Arabidopsis . Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 118: e2107558118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bascom CS Jr, Hepler PK, Bezanilla M. 2018. Interplay between ions, the cytoskeleton, and cell wall properties during tip growth. Plant Physiology 176: 28–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates TR, Lynch JP. 2001. Root hairs confer a competitive advantage under low phosphorus availability. Plant and Soil 236: 243–250. [Google Scholar]

- Berson T, von Wangenheim D, Takáč T, Šamajová O, Rosero A, Ovečka M, Komis G, Stelzer EH, Šamaj J. 2014. Trans‐golgi network localized small GTPase RabA1d is involved in cell plate formation and oscillatory root hair growth. BMC Plant Biology 14: 252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhosale R, Giri J, Pandey BK, Giehl RFH, Hartmann A, Traini R, Truskina J, Leftley N, Hanlon M, Swarup K et al. 2018. A mechanistic framework for auxin dependent Arabidopsis root hair elongation to low external phosphate. Nature Communications 9: 1409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bielecka M, Watanabe M, Morcuende R, Scheible W‐R, Hawkesford MJ, Hesse H, Hoefgen R. 2015. Transcriptome and metabolome analysis of plant sulfate starvation and resupply provides novel information on transcriptional regulation of metabolism associated with sulfur, nitrogen and phosphorus nutritional responses in Arabidopsis. Frontiers in Plant Science 5: 805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco FA, Meschini EP, Zanetti ME, Aguilar OM. 2009. A small GTPase of the Rab family is required for root hair formation and preinfection stages of the common bean‐Rhizobium symbiotic association. Plant Cell 21: 2797–2810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bläsing OE, Gibon Y, Günther M, Höhne M, Morcuende R, Osuna D, Thimm O, Usadel B, Scheible WR, Stitt M. 2005. Sugars and circadian regulation make major contributions to the global regulation of diurnal gene expression in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 17: 3257–3281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breuninger H, Thamm A, Streubel S, Sakayama H, Nishiyama T, Dolan L. 2016. Diversification of a transcription factor family led to the evolution of antagonistically acting genetic regulators of root hair growth. Current Biology 26: 1622–1628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brost C, Studtrucker T, Reimann R, Denninger P, Czekalla J, Krebs M, Fabry B, Schumacher K, Grossmann G, Dietrich P. 2019. Multiple cyclic nucleotide‐gated channels coordinate calcium oscillations and polar growth of root hairs. The Plant Journal 99: 910–923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown LK, George TS, Thompson JA, Wright G, Lyon J, Dupuy L, Hubbard SF, White PJ. 2012. What are the implications of variation in root hair length on tolerance to phosphorus deficiency in combination with water stress in barley (Hordeum vulgare)? Annals of Botany 110: 319–328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruex A, Kainkaryam RM, Wieckowski Y, Kang YH, Bernhardt C, Xia Y, Zheng X, Wang JY, Lee MM, Benfey P et al. 2012. A gene regulatory network for root epidermis cell differentiation in Arabidopsis. PLoS Genetics 8: e1002446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bustos R, Castrillo G, Linhares F, Puga MI, Rubio V, Pérez‐Pérez J, Solano R, Leyva A, Paz‐Ares J. 2010. A Central regulatory system largely controls transcriptional activation and repression responses to phosphate starvation in Arabidopsis. PLoS Genetics 6: e1001102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z‐H, Nimmo GA, Jenkins GI, Nimmo HG. 2007. BHLH32 modulates several biochemical and morphological processes that respond to Pi starvation in Arabidopsis. The Biochemical Journal 405: 191–198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho HT, Cosgrove DJ. 2002. Regulation of root hair initiation and expansin gene expression in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 14: 3237–3253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis MD, Grossniklaus U. 2003. A gateway cloning vector set for high‐throughput functional analysis of genes in planta. Plant Physiology 133: 462–469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datta S, Prescott H, Dolan L. 2015. Intensity of a pulse of RSL4 transcription factor synthesis determines Arabidopsis root hair cell size. Nature Plants 1: 15138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devaiah BN, Karthikeyan AS, Raghothama KG. 2007. WRKY75 transcription factor is a modulator of phosphate acquisition and root development in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiology 143: 1789–1801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Y, Xu P, Li B, Li P, Wen X, An F, Gong Y, Xin Y, Zhu Z, Wang Y et al. 2017. Ethylene promotes root hair growth through coordinated EIN3/EIL1 and RHD6/RSL1 activity in Arabidopsis . Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 114: 13834–13839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gahoonia TS, Nielsen NE, Joshi PA, Jahoor A. 2001. A root hairless barley mutant for elucidating genetic of root hairs and phosphorus uptake. Plant and Soil 235: 211–219. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson DG, Young L, Chuang RY, Venter JC, Hutchison CA 3rd, Smith HO. 2009. Enzymatic assembly of DNA molecules up to several hundred kilobases. Nature Methods 6: 343–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grierson C, Nielsen E, Ketelaarc T, Schiefelbein J. 2014. Root hairs. The Arabidopsis Book 12: e0172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajdukiewicz P, Svab Z, Maliga P. 1994. The small, versatile pPZP family of Agrobacterium binary vectors for plant transformation. Plant Molecular Biology 25: 989–994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haling RE, Brown LK, Bengough AG, Young IM, Hallett PD, White PJ, George TS. 2013. Root hairs improve root penetration, root–soil contact, and phosphorus acquisition in soils of different strength. Journal of Experimental Botany 64: 3711–3721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han X, Zhang M, Yang M, Hu Y. 2020. Arabidopsis JAZ proteins interact with and suppress RHD6 transcription factor to regulate jasmonate‐stimulated root hair development. Plant Cell 32: 1049–1062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanlon MT, Ray S, Saengwilai P, Luthe D, Lynch JP, Brown KM. 2018. Buffered delivery of phosphate to Arabidopsis alters responses to low phosphate. Journal of Experimental Botany 69: 1207–1219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang Y, Choi H‐S, Cho H‐M, Cho H‐T. 2017. Tracheophytes contain conserved orthologs of a basic helix‐loop‐helix transcription factor that modulate ROOT HAIR SPECIFIC genes. Plant Cell 29: 39–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang Y, Lee H, Lee Y‐S, Cho H‐T. 2016. Cell wall‐associated ROOT HAIR SPECIFIC 10, a proline‐rich receptor‐like kinase, is a negative modulator of Arabidopsis root hair growth. Journal of Experimental Botany 67: 2007–2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain A, Poling MD, Smith AP, Nagarajan VK, Lahner B, Meagher RB, Raghothama KG. 2009. Variations in the composition of gelling agents affect morphophysiological and molecular responses to deficiencies of phosphate and other nutrients. Plant Physiology 150: 1033–1049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jefferson RA, Kavanagh TA, Bevan MW. 1987. GUS fusions: beta‐glucuronidase as a sensitive and versatile gene fusion marker in higher plants. EMBO Journal 6: 3901–3907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jungk A. 2001. Root hairs and the acquisition of plant nutrients from soil. Journal of Plant Nutrition and Soil Science 164: 121–129. [Google Scholar]

- Karimi M, Inzé D, Depicker A. 2002. GATEWAY™ vectors for Agrobacterium‐mediated plant transformation. Trends in Plant Science 7: 193–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato M, Tsuge T, Maeshima M, Aoyama T. 2019. Arabidopsis PCaP2 modulates the phosphatidylinositol 4,5‐bisphosphate signal on the plasma membrane and attenuates root hair elongation. The Plant Journal 99: 610–625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim CM, Dolan L. 2016. ROOT HAIR DEFECTIVE SIX‐LIKE Class I genes promote root hair development in the grass Brachypodium distachyon . PLoS Genetics 12: e1006211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim CM, Han C‐D, Dolan L. 2017. RSL class I genes positively regulate root hair development in Oryza sativa . New Phytologist 213: 314–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kudla J, Bock R. 2016. Lighting the way to protein–protein interactions: recommendations on best practices for bimolecular fluorescence complementation analyses. Plant Cell 28: 1002–1008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Stecher G, Li M, Knyaz C, Tamura K. 2018. Mega X: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. Molecular Biology and Evolution 35: 1547–1549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusano H, Tominaga R, Wada T, Kato M, Aoyama T. 2014. Phosphoinositide signaling in root hair tip growth. In: Fukuda H, eds. Plant cell wall patterning and cell shape. New York, NY, USA: Wiley‐Blackwell, 239–267. [Google Scholar]

- Kwon T, Sparks JA, Liao F, Blancaflor EB. 2018. ERULUS is a plasma membrane‐localized receptor‐like kinase that specifies root hair growth by maintaining tip‐focused cytoplasmic calcium oscillations. Plant Cell 30: 1173–1177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambers H, Martinoia E, Renton M. 2015. Plant adaptations to severely phosphorus‐impoverished soils. Current Opinion in Plant Biology 25: 23–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letunic I, Bork P. 2021. Interactive Tree Of Life (iTOL) v.5: an online tool for phylogenetic tree display and annotation. Nucleic Acids Research 49: W293–W296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X. 2011. Infiltration of Nicotiana benthamiana protocol for transient expression via Agrobacterium. Bio‐protocol 1: e95. [Google Scholar]

- Lin Q, Ohashi Y, Kato M, Tsuge T, Gu H, Qu L‐J, Aoyama T. 2015. Glabra2 directly suppresses basic helix‐loop‐helix transcription factor genes with diverse functions in root hair development. Plant Cell 27: 2894–2906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch JP. 2011. Root phenes for enhanced soil exploration and phosphorus acquisition: tools for future crops. Plant Physiology 156: 1041–1049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangano S, Denita‐Juarez SP, Choi H‐S, Marzol E, Hwang Y, Ranocha P, Velasquez SM, Borassi C, Barberini ML, Aptekmann AA et al. 2017. Molecular link between auxin and ROS‐mediated polar growth. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 114: 5289–5294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann DGJ, LaFayette PR, Abercrombie LL, King ZR, Mazarei M, Halter MC, Poovaiah CR, Baxter H, Shen H, Dixon RA et al. 2012. Gateway‐compatible vectors for high‐throughput gene functional analysis in switchgrass (Panicum virgatum L.) and other monocot species. Plant Biotechnology Journal 10: 226–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marzec M, Melzer M, Szarejko I. 2015. Root hair development in the grasses: what we already know and what we still need to know. Plant Physiology 168: 407–414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masucci JD, Schiefelbein JW. 1994. The rhd6 mutation of Arabidopsis thaliana alters root‐hair initiation through an auxin‐ and ethylene‐associated process. Plant Physiology 106: 1335–1346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendrinna A, Persson S. 2015. Root hair growth: it's a one way street. F1000Prime Reports 7: 23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miguel MA, Postma JA, Lynch JP. 2015. Phene synergism between root hair length and basal root growth angle for phosphorus acquisition. Plant Physiology 167: 1430–1439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miura K, Rus A, Sharkhuu A, Yokoi S, Karthikeyan AS, Raghothama KG, Baek D, Koo YD, Jin JB, Bressan RA et al. 2005. The Arabidopsis SUMO E3 ligase SIZ1 controls phosphate deficiency responses. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 102: 7760–7765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]