Abstract

DNA sequences were analyzed for three groups of species from the Lepocinclis genus (L. acus‐like, L. oxyuris‐like, and L. tripteris‐like) along with cellular morphology. Phylogenetic analyses were based on nuclear SSU rDNA, LSU rDNA, and plastid‐encoded LSU rDNA. DNA sequences were obtained from species available in culture collections (L. acus SAG 1224‐1a and UTEX 1316) and those isolated directly from the environment in Poland (48 isolates), resulting in 79 new sequences. The obtained phylogenetic tree of Lepocinclis included 27 taxa, five of which are presented for the first time (L. convoluta, L. gracillimoides, L. longissima, L. pseudospiroides, and L. torta) and nine taxonomically verified and described. Based on morphology, literature data, and phylogenetic analyses, the following species were distinguished: in the L. acus‐like group, L. longissima and L. acus; in the L. tripteris‐like group, L. pseudospiroides, L. torta, and L. tripteris; in the L. oxyuris‐like group, L. gracillimoides, L. oxyuris var. oxyuris, and L. oxyuris var. helicoidea. For all verified species, diagnostic descriptions were emended, nomenclatural adjustments were made, and epitypes were designated.

Keywords: Euglenida, environmental sampling, Lepocinclis, microalgae, nSSU rDNA, phylogeny, taxonomy

Abbreviations

- BI

Bayesian inference

- bs

bootstrap

- ML

maximum likelihood

- nt

nucleotide

- pp

posteriori probability

- rbs

rapid bootstrap

Lepocinclis was described in the 19th century (Perty 1849), but its diagnostic description was emended at the beginning of the 21st century due to five species being transferred from Euglena into Lepocinclis based on molecular data (L. acus, L. butschlii, L. oxyuris, L. ovum, and L. tripteris; Marin et al. 2003). Lepocinclis is currently classified in the family Phacaceae, together with the representatives of Phacus, Discoplastis (Kim et al. 2010) and Flexiglena (Łukomska‐Kowalczyk et al. 2021). All family representatives possess numerous, discoidal, parietal chloroplasts without pyrenoids.

Currently there are over 114 species names (as well as 176 intraspecific names) listed under Lepocinclis in Algaebase, of which 85 are flagged as taxonomically accepted (http://www.algaebase.org; Guiry and Guiry 2021). The number of taxa continues to change as taxonomic verifications are still ongoing, but only 21 taxa have been sequenced (Marin et al. 2003, Kosmala et al. 2005, Bennett and Triemer 2012, Kim et al. 2015, Łukomska‐Kowalczyk et al. 2020). The main reason for such a poor representation is the limited number of species available in culture collections. What follows is the necessity to isolate representatives directly from the environment. Recently, this method was used to verify the large L. ovum‐like species complex wherein 14 epitypes were designated, including Lepocinclis globulus, the generitype species (Łukomska‐Kowalczyk et al. 2020). The research presented herein focuses on three species groups of Lepocinclis (L. acus‐like, L. oxyuris‐like, and L. tripteris‐like), the representatives of which are common and cosmopolitan in freshwater habitats. However, the discrimination of the taxa within these groups based on morphological traits has been tedious and therefore widely discussed by the authors of critical monographs (Gojdics 1953, Pringsheim 1956, Popova 1966, Popova and Safonova 1976, among others). In this study, phylogenetic and morphological analyses combined with a review of the literature concerning Lepocinclis allowed an increase in the number of sequenced taxa of three species complexes and a comparison of morphological and DNA sequences of new isolates along with information from the literature. The study resulted in the following: (a) the assessment of morphological and genetic diversity; (b) verification of diagnostic morphological features for distinct taxa (well‐established clades); (c) reconstruction of phylogenetic relationships; and (d) taxonomic verification, emending diagnoses and designating epitypes for well‐distinguished taxa.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sampling and morphological study

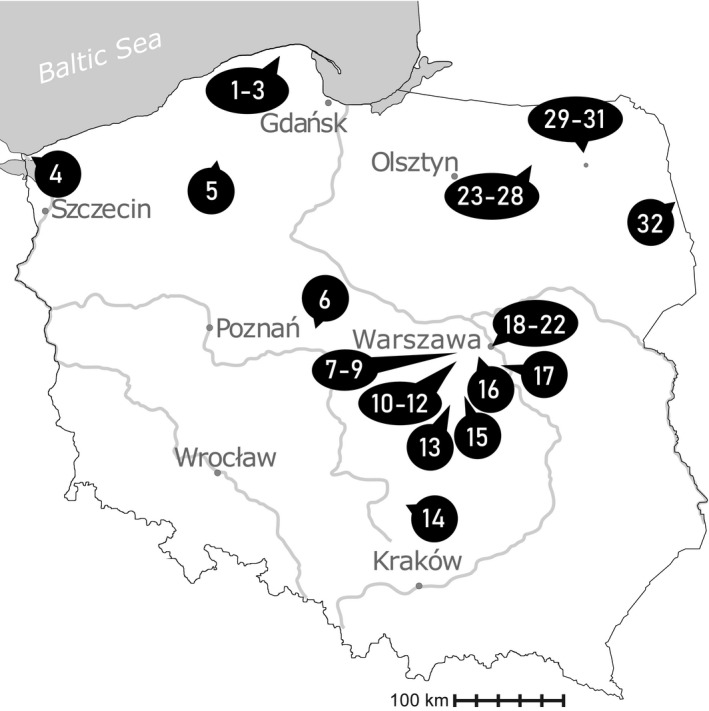

During ten seasons (2011–2020), plankton samples were collected from 32 eutrophic water bodies located in Poland (Fig. 1), using a plankton net with a mesh size of 10 µm. Samples were screened in terms of their species diversity and 4–90 cells (Table S1), exhibiting the same morphology, were isolated from the sample using a micromanipulator (MM‐89 Narishige) with a micropipette installed on a Nikon Ni‐U microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan; see Figs. [Link], [Link], [Link]). Morphological studies (descriptions and measurements) and documentation (photographs and video clips) of the isolated cells (isolates) of the Lepocinclis morphotypes and those of strains from culture collections were taken with a NIKON Eclipse E‐600 microscope with differential interference contrast, equipped with the NIS Elements Br 3.1 software (Nikon, Japan) for image processing and recording. Photographs (and video clips) were taken using a NIKON DX‐1200 digital camera connected to the microscope. The NIS Elements Br measurement program was used for morphometric studies; three parameters were measured for the cells of each isolate (strain) — cell length, cell width, and tail length (which was defined as the hyaline projection); measurements were conducted from photographs of the isolates (strains; as in Figs. [Link], [Link], [Link]). The data were analyzed using the R v.3.2.0 software (R Development Core Team 2008); means and standard deviations are given in Table 1. Isolates (i.e., morphologically identical cells) were transferred through multiple drops of sterile media (to clean the sample), and kept frozen at −80°C until DNA extraction.

Fig. 1.

Map illustrating sampling locations in Poland. The names of lakes or towns in which the studied water bodies were located are marked with numbers: (1) Słajszewo, (2) Jęczewo, (3) Perlinko, (4) Świnoujście, (5) Brzezie, (6) Mąkolno, (7) Boża Wola, (8) Piorunów, (9) Błonie, (10) Izdebno Kościelne 1, (11) Izdebno Kościelne 2, (12) Izdebno Nowe, (13) Cielądz, (14) Łysaków, (15) Biała Rawska, (16) Pruszków, (17) Baniocha, (18) Imielin, (19) Łazienki, (20) Moczydło, (21) Glinianki Włościańskie, (22) Jelonki, (23) Urwitałt 13, (24) Urwitałt 15, (25) Urwitałt 16, (26) Urwitałt 17, (27) Urwitałt 19, (28) Urwitałt 20, (29) Kije, (30) Dunajek, (31) Oracze, and (32) Wojnowce.

Table 1.

Comparison of morphological traits among the study’s isolates/strains of Lepocinclis (* based on three images available on the website of SAG Algae Collection; ** based on a single photograph sent by Bennet & Triemer.*** based on figure 1f in Bennet and Triemer 2012).

| Taxon | Isolate/strain | Number of measured cells | Cell length (μm) Mean ± SD | Cell width (μm) Mean ± SD | Tail length (μm) Mean ± SD | Cell shape | Number and shape of large paramylon grains |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L. acus | SAG 1224‐1a | 3* | 116.9 ± 13.3 | 8.0 ± 0.5 | 12.5 ± 0.5 | Narrow‐spindle | a few, rod‐shaped |

| UTEX 1316 | 18 | 122.0 ± 6.7 | 10.1 ± 1.6 | 11.7 ± 2.4 | |||

| UW1932Kij | 5 | 156.0 ± 7.4 | 13.0 ± 1.7 | 29.6 ± 1.9 | |||

| UW2441Swi | 88 | 147.3 ± 7.6 | 10.7 ± 1.3 | 22.1 ± 3.5 | |||

| UW2444Pio | 20 | 136.8 ± 4.9 | 9.6 ± 1.2 | 14.5 ± 2.1 | |||

| UW2462Mak | 22 | 144.8 ± 4.0 | 12.8 ± 1.3 | 23.1 ± 3.5 | |||

| UW2554BWo | 25 | 162.4 ± 9.5 | 11.3 ± 1.1 | 34.0 ± 5.8 | |||

| L. convoluta | UW1666Ur13 | 20 | 141.7 ± 2.9 | 13.1 ± 1.4 | 25.8 ± 2.6 | Fusiform, spirally twisted | 6–8 concave plates |

| L. gracillimoides | UW1580Laz | 6 | 297.5 ± 10.0 | 23.7 ± 2.1 | 36.6 ± 4.1 | Cylindrical with furrow | two rod‐shaped |

| UW1956Jel | 9 | 309.7 ± 11.2 | 24.9 ± 1.7 | 47.5 ± 7.3 | |||

| UW2000Blo | 14 | 288.9 ± 10.0 | 23.2 ± 2.7 | 32.5 ± 5.6 | |||

| UW2161Ban | 12 | 291.3 ± 11.6 | 24.4 ± 1.8 | 33.9 ± 6.5 | |||

| UW2536Mak | 13 | 278.2 ± 5.7 | 22.4 ± 2.3 | 26.5 ± 2.4 | |||

| L. longissima | UW2443Pio | 35 | 317.8 ± 8.2 | 10.8 ± 1.3 | 51.4 ± 7.0 | Cylindrical, greatly elongated | a few, rod‐shaped |

| UW2460Mak | 50 | 312.2 ± 10.0 | 12.9 ± 1.1 | 35.5 ± 6.0 | |||

| UW2466Jel | 79 | 309.3 ± 6.7 | 13.5 ± 1.0 | 39.4 ± 6.1 | |||

| UW2553BWo | 56 | 284.5 ± 9.8 | 13.2 ± 1.3 | 51.1 ± 5.9 | |||

| L. oxyuris var. helicoidea | Preisfeld | 1** | 436.0 | 39.4 | 30.3 | Cylindrical with furrow | several, rod‐shaped |

| UW1819Ora | 18 | 330 ± 13.7 | 33.8 ± 3.3 | 30.6 ± 3.8 | |||

| UW1904Woj | 1 | 385.0 | 43.0 | 30.0 | |||

| UW2251Tot | 10 | 320.2 ± 9.9 | 34.3 ± 4.2 | 26.5 ± 3.9 | |||

| L. oxyuris var. oxyuris | MSU | 1*** | 160.0 | 16.0 | 22.6 | Cylindrical with furrow | two, ring‐shaped |

| UW1582Laz | 2 | 140.0 ± 2.8 | 16.8 ± 0.3 | 17.5 ± 0.7 | |||

| UW1644Ur16 | 1 | 168.0 | 18.0 | 23.0 | |||

| UW1657Ur20 | 9 | 164.0 ± 8.8 | 19.3 ± 1.9 | 20.9 ± 2.0 | |||

| UW1717Brz | 26 | 209.7 ± 6.4 | 21.6 ± 1.6 | 23.3 ± 3.0 | |||

| UW1818Ora | 26 | 135.4 ± 6.0 | 20.4 ± 2.0 | 21.6 ± 3.2 | |||

| UW1820Ora | 4 | 196.3 ± 5.8 | 19.1 ± 3.6 | 22.8 ± 3.1 | |||

| UW1942Moc | 21 | 153.6 ± 5.4 | 18.6 ± 2.1 | 17.9 ± 1.7 | |||

| UW1951Imi | 21 | 156.2 ± 5.0 | 19.4 ± 1.6 | 18.7 ± 2.5 | |||

| UW2198Pru | 5 | 159.5 ± 4.6 | 21.3 ± 2.0 | 21.4 ± 2.6 | |||

| UW2201Ban | 18 | 162.7 ± 7.2 | 20.7 ± 2.5 | 19.6 ± 4.0 | |||

| UW2260Sla | 7 | 172.2 ± 4.8 | 16.8 ± 3.5 | 28.5 ± 2.8 | |||

| UW2391IK2 | 53 | 170.1 ± 7.2 | 19.9 ± 2.2 | 19.6 ± 3.3 | |||

| UW2432Jec | 27 | 203.0 ± 6.2 | 22.3 ± 2.0 | 21.2 ± 2.8 | |||

| UW2561BWo | 40 | 179.3 ± 7.0 | 18.7 ± 1.6 | 18.9 ± 3.9 | |||

| L. pseudospiroides | UW1567Ur15 | 15 | 211.6 ± 10.0 | 18.3 ± 1.4 | 23.1 ± 2.4 | Loosely twisted corkscrew | two, rod‐shaped |

| UW1791Dun | 17 | 183.1 ± 5.6 | 16.3 ± 1.0 | 30.6 ± 3.2 | |||

| UW1959Woj | 20 | 188.6 ± 5.3 | 15.6 ± 1.5 | 26.0 ± 3.4 | |||

| UW2188BRa | 11 | 187.3 ± 5.8 | 16.4 ± 1.5 | 22.2 ± 2.3 | |||

| UW2421INo | 13 | 194.5 ± 4.1 | 16.0 ± 1.4 | 25.3 ± 3.9 | |||

| UW2464Mak | 45 | 196.8 ± 3.5 | 16.9 ± 1.2 | 25.4 ± 2.6 | |||

| UW2474Per | 42 | 197.6 ± 4.6 | 17.9 ± 1.2 | 21.8 ± 3.4 | |||

| L. torta | UW2419INo | 17 | 78.4 ± 1.8 | 11.4 ± 0.8 | 14.2 ± 1.6 | Tightly twisted corkscrew | two, rod‐shaped |

| UW2475Per | 56 | 81.8 ± 5.5 | 15.5 ± 1.8 | 15.5 ± 2.4 | |||

| UWOB | 15 | 64.0 ± 6.2 | 11.8 ± 1.2 | ||||

| L. tripteris | UW2187Cie | 11 | 109.7 ± 3.4 | 13.5 ± 1.3 | 18.3 ± 2.2 | Loosely twisted corkscrew | two, rod‐shaped |

| UW2463Mak | 83 | 114.2 ± 3.6 | 15.8 ± 1.3 | 19.9 ± 2.6 | |||

| UW2484Lys | 42 | 108.1 ± 3.2 | 14.0 ± 1.0 | 17.7 ± 1.9 |

DNA isolation, amplification, and sequencing

Isolation of total DNA from samples (environmental samples and laboratory cultures of strains), PCR amplification of three genes (nSSU rDNA, nLSU rDNA, and cpLSU rDNA), and purification and sequencing of the PCR products were performed using methods as previously described (Zakryś et al. 2002, Łukomska‐Kowalczyk et al. 2021). An additional step of whole genome amplification was carried out in the case of environmental samples (Bennett and Triemer 2012). We used the previously described primers for nSSU rDNA (Kim et al. 2010, Łukomska‐Kowalczyk et al. 2020), nLSU rDNA (Kim et al. 2013, Łukomska‐Kowalczyk et al. 2021), and cpLSU rDNA (Kim et al. 2010) amplification. To obtain some sequences, nested PCR method was used.

Sequence accession numbers, alignment, and sequence analyses

Seventy‐nine new sequences used in the present study were submitted to GenBank with the following accession numbers: nSSU rDNA: MW730858‐MW730903; nLSU rDNA: MW730840‐MW730857 and cpLSU rDNA: MW748160‐MW748174. Information about the accession numbers for the nSSU, nLSU, and cpLSU rDNA sequences reported here and those used for phylogenetic analyses are shown in Table S1. Two datasets were used for analyses, nSSU, nLSU, and cpLSU rDNA (or only two of three) of 65 strains/isolates and only nSSU rDNA sequences of 106 strains/isolates. The nSSU rDNA sequences from both datasets, nLSU and cpLSU were aligned separately using FSA 1.15.7 (Bradley et al. 2009) with the default options. Alignments were inspected by eye and corrected if necessary. Regions of doubtful homology between sites were removed from the alignments using TrimAl 1.2 with the option “automated1” (Capella‐Gutierrez et al. 2009). After trimming, 1457, 722, and 1657 positions remained for nSSU rDNA, nLSU rDNA, and cpLSU rDNA, respectively (three genes analysis) and 1393 positions for nSSU rDNA in the single gene analysis. The final dataset for the analysis based on three genes concatenated in SeaView (Gouy et al. 2010) consisted of 3836 positions.

Sequence diversity of nSSU rDNA was calculated using the Mega X software (Kumar et al. 2018) as pair‐wise distance based only on unambiguously aligned positions. Partition homogeneity test was performed by PAUP* (Version 4.0a169).

Phylogenetic analyses

The model of sequence evolution was selected using ModelTest‐NG (Darriba et al. 2020). The model was chosen based on BIC criteria for each of the four alignments and for three combined alignments (nSSU rDNA, nLSU rDNA, and cpLSU rDNA for the three gene tree; Lanave et al. 1984, Tavare 1986, Rodriguez et al. 1990). TrNef model was used for Maximum Likelihood (ML) and Bayesian inference (BI) analysis of the single gene (nSSU rDNA only) alignment (Base frequencies: 0.2500 0.2500 0.2500 0.2500; Substitution Rates: 1.0000 3.4572 1.0000 1.0000 5.5798 1.0000; Invariant sites prop: 0.3951; Gamma shape: 0.5629). GTR model was used for BI (Base frequencies: 0.2645 0.2082 0.2655 0.2618; Substitution Rates: 0.9974 3.5255 1.3916 0.4559 4.8567 1.0000; Invariant sites prop: 0.4508; Gamma shape: 0.6428), and GTR, GTR, and TrNef models were used in ML analysis for three partitions (genes) — nSSU rDNA, nLSU rDNA, and cpLSU rDNA, respectively. Both ML trees were inferred using RAxML‐NG (Kozlov et al. 2019) with robustness inferred by rapid bootstrapping (1,000 pseudoreplicates). For the three‐marker tree, we used three partitions with individual α‐shape parameters and empirical estimated base frequencies parameters. Both Bayesian inferences were performed in MrBayes 3.2.6 software (Ronquist and Huelsenbeck 2003) with default priors. A gamma correction with eight categories and proportion of invariable sites were used. Two independent runs with four Markov chains were performed. In each run, the chains lasted for 10,000,000 generations and trees were sampled every 1000 generations. The first 25% of trees were discarded as burn‐in. Convergence among runs was assumed as the average standard deviation of split frequencies was below 0.01. The trees were visualized using FigTree v.1.4.2 (available at http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software).

The alignments and corresponding phylogenetic trees have been submitted to TreeBase (Study Accession URL: http://purl.org/phylo/treebase/phylows/study/TB2:S28370.

RESULTS

Phylogenetic analyses and morphological characteristics

The partition homogeneity test (P values equal to 0.01) showed that all three datasets could be combined. The topologies of the ML and BI trees were almost identical, save for the unstable position of Lepocinclis convoluta and some solutions regarding positions of a few representatives of the Lepocinclis oxyuris clade and of Phacus.

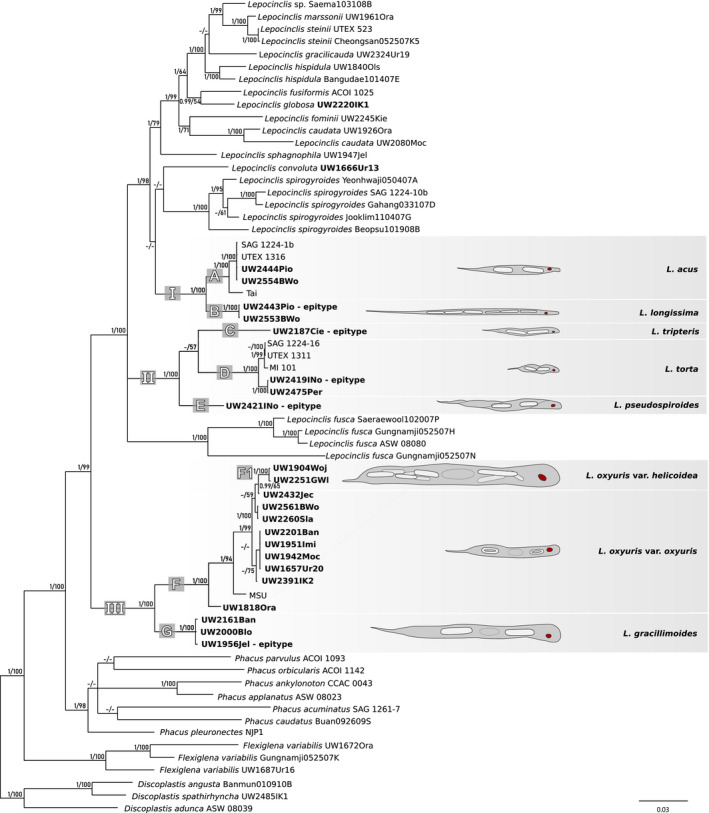

Representatives of the three analyzed groups of taxa (Lepocinclis acus‐like, L. tripteris‐like, and L. oxyuris‐like) formed three well‐supported clades (I, II, and III) on the Bayesian and ML phylogeny trees obtained for both analyses. (Fig. 2; Fig. S4 in the Supporting Information). ML trees are not presented. Taking into account morphological data, seven species were distinguished, labeled here as groups A‐G (Fig. S4) or five groups and two singlets (C, E; Fig. 2). All of the species were distinguishable by their morphological characteristics: the number and shape of the paramylon grains and the size and shape of the cells (Table 1).

Fig. 2.

Consensus Bayesian tree based on 65 sequences of nSSU rDNA, 56 of nLSU rDNA and 53 of cpLSU rDNA representing 65 strains or isolates. Strains or isolates with at least one sequence represented for the first time are indicated in bold type. Nodes are labeled with the Bayesian posterior probability (pp) values and rapid bootstrap (rbs) values obtained by maximum‐likelihood analyses, respectively. The pp values <0.90, rbs values <50, and clades not present in the particular analysis are marked with a hyphen (‐). Scale bar represents number of substitutions per site. [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Clade I included two acus‐like species forming strongly supported sister subclades, a Lepocinclis acus clade (A, pp = 1; rbs = 100) and a L. longissima clade (B, pp = 1; rbs = 100). The nSSU rDNA interspecific variability ranged between 5.9% and 7.5% (Table S2 in the Supporting Information). Subclade A included five sequences of L. acus, one environmental isolate from Thailand, two newly obtained Polish isolates, and two strains from culture collections (Fig. 2). The nSSU rDNA tree included two more sequences from culture collection strains and an additional three sequences from Poland (Fig. S4). The genetic diversity of nSSU rDNA did not exceed 4.3% (Table S2). Subclade B consisted of two isolates of L. longissima, both newly obtained from Poland (Fig. 2). There were two more Polish isolates on the nSSU rDNA tree (Fig. S4). Genetic variability of nSSU rDNA among the isolates was not observed (Table S2). Both species can easily be distinguished by cell shape and size. Representatives of L. longissima were characterized by greatly elongated, cylindrical cells (around 300 µm), whereas cells of L. acus were more narrow and spindle‐shaped (around 150 µm long; Fig. 3, a and g; Table 1).

Fig. 3.

Light microscope photographs showing an overview of living cells of the studied Lepocinclis strains (=isolates): (a) fusiform cell of Lepocinclis acus (strain SAG 1224‐1b) ending with a sharp hyaline tail; (b) cylindrical cell of L. gracillimoides (isolate UW1956Jel) with two visibly large, rod‐like paramylon grains (arrows); (c) cylindrical cell of L. oxyuris var. oxyuris (isolate UW1942Moc) with a visible furrow (arrowhead) and two large, ring‐shaped paramylon grains (arrows); (d) large, cylindrical cell of L. oxyuris var. helicoidea (isolate UW2251GWl) with visibly large, rod‐shaped paramylon grains located in groups on both sides of the nucleus (arrows); (e, f) L. convoluta (isolate UW1666Ur13): (e) spirally twisted cell with distinctive paramylon grains laterally located along the cell (arrows), (f); high magnification of the large grains in the form of concave plates (arrows); (g) cylindrical cell of L. longissima (isolate UW2443Pio) ending with a sharp hyaline tail; (h, i) spindle‐like, tightly twisted cells of L. torta (isolate UW2419INo); (j, k) fusiform, loosely twisted cells of L. tripteris: (j) isolate UW2187Cie (k) isolate UW2484Lys; (l, m) cylindrical, loosely twisted cells of L. pseudospiroides (isolate UW2421INo). Scale bars 10 µm. [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Clade II represented corkscrew‐shaped cells (triangular in cross section) of Lepocinclis tripteris‐like species and consisted of one subclade and two single isolate branches (C‐E). Interspecific variability of the species was observed (9.4–12.6%; Table S3 in the Supporting Information). The single isolate forming branch C represented Lepocinclis tripteris species (Fig. 2). On the nSSU rDNA tree, it formed a well‐supported clade (pp = 1; rbs = 100) with two other sequences from Poland (Fig. S4). There was no genetic variability of nSSU rDNA in the samples (Table S3). Representatives of this species were loosely twisted like the cells of L. pseudospiroides, but smaller (around 100 µm long; Fig. 3 j and k; Table 1). The relationship of subclade D (pp = 1; rbs = 100) to branch C was unresolved due to very weak support (Fig. S4). Subclade D consisted of two groups representing L. torta, one with three strains from culture collections (four on the nSSU rDNA tree) and the other with two Polish isolates. Genetic variability of the species did not exceed 3% (Table S3). Cells of L. torta were tightly twisted and about twice as small as the cells of L. pseudospiroides (around 80 µm long; Fig. 3 h and i; Table 1). Branch E was a single isolate of L. pseudospiroides obtained from Poland (Fig. 2). On the nSSU rDNA tree, this isolate formed a maximally supported clade with six other sequences from Poland (Fig. S4). There was no genetic variability of nSSU rDNA between the samples (Table S3). The individuals of L. pseudospiroides were loosely twisted (cells around 200 µm long; Fig. 3 l and m; Table 1).

The earliest branching clade of Lepocinclis representing oxyuris‐like species (III) consisted of two sister subclades, L. gracillimoides (G) and L. oxyuris (F). Both clades were strongly supported (pp = 1, rbs = 100; Fig. 2). The interspecific variability between the species did not exceed 13.1% (Table S4 in the Supporting Information). Subclade F consisted of 12 samples of L. oxyuris — 11 newly obtained isolates from Poland and one strain from a culture collection (Fig. 2). On the nSSU rDNA tree, there were seven more nSSU rDNA sequences, six newly obtained from isolates from Poland and one strain from a culture collection (Fig. S4). Genetic variability of nSSU rDNA between the sequences of this species varied from 0.0 to 5.8% (Table S4). Two varieties were delimited within the clade of L. oxyuris. One, var. oxyuris, was a paraphyletic group of samples (Fig. 2), and its genetic variability did not exceed 5.6% (Table S4). The other variety (var. helicoidea) formed a maximally supported clade (F1) that branched as a sister clade to one of the isolates of L. oxyuris var. oxyuris on the Bayesian tree with moderate support (pp = 0.99, rbs = 65; Fig. 2). Genetic variability of this variety did not exceed 0.8% (Table S4). Both varieties differ in cell size and number and shape of paramylon grains. Lepocinclis oxyuris var. oxyuris has smaller cells (130–210 µm) than L. oxyuris var. helicoidea (around 350–400 µm), and they differ in the number and shape of the paramylon grains. Cells of var. oxyuris possess two ring‐shaped grains, whereas cells of var. helicoidea have a few rod‐shaped paramylon grains (Fig. 3, c and d; Table 1). The interspecific variability between these two varieties did not exceed 5.8% (Table S4). The L. gracillimoides subclade (G) included three newly obtained isolates from Poland (Fig. 2). On the nSSU rDNA tree, this clade was represented by five new sequences obtained from Poland (Fig. S4). Genetic variability of nSSU rDNA of this species did not exceed 1.6% (Table S4). Cells of L. gracillimoides possess two rod‐shaped paramylon grains (one located anterior to the nucleus and the other posterior to it; Fig. 3b and Table 1).

Genetic variability

Analysis of 24 nSSU rDNA sequences from the oxyuris‐like group, 15 from the tripteris‐like group and 14 from the acus‐like group revealed that interspecific genetic diversity varied from 5.9% (between Lepocinclis longissima and L. acus) to 13.1% (between L. oxyuris and L. gracillimoides; Tables [Link], [Link], [Link]). The intraspecific diversity varied from 0.0% to 5.8% (between L. oxyuris var. helicoidea and L. oxyuris var. oxyuris). Genetic variability of nSSU rDNA was not observed within the L. tripteris, L. pseudospiroides, and L. longissima species, even when the strains or isolates originated from different parts of the world (for example Polish isolate of L. acus UW2444Pio and strain SAG 1224‐1b from the United Kingdom).

Coexistence of species

Strains were isolated from 32 eutrophic water bodies located throughout Poland (Fig. 1). The occurrence of more than one taxon from each of the three groups (Lepocinclis acus‐like, L. tripteris‐like, and L. oxyuris‐like) was noted in many places (Table S5 in the Supporting Information). Lepocinclis oxyuris var. oxyuris and L. acus occurred the most often and at the highest densities. Lepocinclis longissima, L. pseudospiroides, L. tripteris, and L. torta were less common and observed at lower densities. Lepocinclis oxyuris var. helicoidea and L. gracillimoides were the most rare and noted at low densities.

Taxonomic revisions

Lepocinclis taxa vary in size and cell shape, but all contain numerous, parietal, small, discoid chloroplasts that lack pyrenoids. They also possess large paramylon grains within the cell, the shape, number, and position of which are diagnostic features.

Herein, phylogenetic and morphological analyses and a review of the literature focused on the three species groups of Lepocinclis (L. acus‐like, L. tripteris‐like, and L. oxyuris‐like), which could not be distinguished by morphology alone.

The study’s basis was to define a species as a group of singular morphotypes, which create a (well supported) clade on the phylogenetic tree. For these species, diagnostic descriptions were emended, epitypes designated, and the nomenclature revised.

Given that the isolated cells were destroyed for DNA extraction, the photographs are designated as epitypes (see International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants; Shenzhen Code; chapter II, section 2, article 9.9; Turland et al. 2018).

Lepocinclis Perty, 1849: 28, emended by Marin & Melkonian 2003 in Marin et al. 2003: 103.

Lepocinclis acus (O.F.Müller) B. Marin & Melkonian 2003 in Marin et al. 2003: 104 (Fig. 3a ).

Emended diagnosis: Cells rigid, fusiform (100–162 × 7.5–16 µm), apically elongated into a “snout,” terminated with a sharp hyaline tail (on average 12–29 µm). Large, rod‐shaped paramylon grains (several to many). Periplast slightly spirally striated following the longitudinal axis.

Lectotype: designated herein, individual marked as “b” in Ehrenberg’s unpublished drawing no. 546 (Ecdraw546), in the Ehrenberg Collection (Institut für Paläontologie, Museum für Naturkunde, Humboldt Universität zu Berlin, Invalidenstr. 43, D10115 Berlin, Germany; see Fig. S5 in the Supporting Information).

Representative DNA sequences: GenBank AJ532460, JN603872, EF525351.

Representative strain: SAG 1224‐1b.

Homotypic synonyms: Euglena acus (O. F. Müller) Ehr. 1830: 508; 1831: 72, 151, pl. 1, fig. 3.

Heterotypic synonyms: Euglena acus var. rigida E. Hübner 1886: 9, fig. 11b; E. acus var. minor Hansgirg 1892: 173; E. acus var. lata Svirenko 1915a: 110 and 130, pl. 2, fig. 11; E. acus var. van‐oyei Deflandre 1924: 242; E. acus var. angularis L.P. Johnson 1944: 114, pl. 3, fig. 14d; E. acutissima Lemmermann 1904: 122, pl. 1, fig. 27; E. acutissima var. parva Playfair 1921: 121, pl. 4, figs. 7, 8; E. acusformis J. Schiller 1925: 94, pl. 3: fig. 17.

Comments: The Polish populations were identified based on the fusiform cell shape and size. Of the 19 individuals visible in Ehrenberg’s original drawing (ECdraw 546 – see Fig. S5), many are regularly spindle‐shaped, with some showing metaboly. Due to the rigidness of the cell, this seems implausible, as normally the cells only bend. Moreover, the individuals vary significantly in terms of size, what is further confirmed by the handwritten note at the bottom of the image (155, 108–77, 6–58, 2 µm). The cell marked as “b” was chosen as the lectotype as it represents well both the size and shape of a swimming cell (the drawing depicts the effect of the flagellum’s movement). The results presented herein further show that the slightly spiral periplast striation is also a diagnostic trait, one never mentioned by Ehrenberg. The size and shape of the cells as well as the periplast striation distinguish Lepocinclis acus from L. longissima (for more details see Discussion and comments for L. longissima). The taxa that constitute L. acus synonyms are those whose cell morphology corresponds to the emended diagnostic description.

Lepocinclis autumnalis S.P. Chu, 1936: 266, figure 1.

Epitype: figure 3r designated in Łukomska‐Kowalczyk et al. 2020.

Representative DNA sequence: GenBank MK534193.

Lepocinclis caudata (A.M. Cunha) Pascher 1927: 592.

Epitype: figure 3q designated in Łukomska‐Kowalczyk et al. 2020.

Representative DNA sequence: GenBank MK534196.

Lepocinclis conica (P. Allorge & M. Lefèvre) Zakryś & M.Łukomska in Łukomska‐Kowalczyk et al. 2020: 289, fig. 3h.

Epitype: figure 3h designated in Łukomska‐Kowalczyk et al. 2020.

Representative DNA sequence: GenBank MK534183.

Lepocinclis convoluta (Korshikov) Zakryś & Chaber, comb. nov. (Fig. 3 e and f).

Basionym: Euglena convoluta Korshikov 1941, Arch. Protist. 95 (1): 23, fig. 1, a and b.

Emended diagnosis: Cells are spirally twisted (120– 150 × 10–17 µm), hardly metabolic, spindle‐like, narrowing toward the ends: apically elongated into a “snout” and oblique, gradually narrowing posteriorly to form a long (19–29 µm), sharp, hyaline caudus. The large, distinctive paramylon grains form concave plates, laterally arranged in the cell; the terminal grains are much smaller. There are around 6–8 large grains, located along the cell peripherally under the periplast, and numerous small grains (mostly ring‐shaped) scattered throughout the cell. Periplast spirally striated. Flagellum short (1/6–1/2 of the cell length) but typical swimming is rarely observed; the cells usually move very slowly and are capable mostly of only slow corkscrew‐like twisting and untwisting, and a longitudinal contraction of the body.

Type locality: Russia, Gorky Disctrict, flocks of benthic cyanobacteria on a bank of small river Seryosha.

Representative DNA sequences: GenBank MW730863, MW730841.

Representative locality: Eutrophic ponds in the Mazurian Lake District near Urwitałt village.

Heterotypic synonym: Euglena breviflagellum Prescott & Gojdics in Prescott 1944: 364–365, pl. 3, figs. 23, 24 (Gojdics 1953, for more details see Discussion section).

Comments: Euglena breviflagellum has been included as a Lepocinclis convoluta synonym as no diagnostic traits have been found that would distinguish the two species.

Lepocinclis cylindrica (Korshikov) W. Conrad 1934: 212, figure 11.

Epitype: figure 3f designated in Łukomska‐Kowalczyk et al. 2020.

Representative DNA sequence: GenBank MK534184.

Lepocinclis fominii (Y.V. Roll) Zakryś & M.Łukomska in Łukomska‐Kowalczyk et al. 2020: 290, figure 3 n and o.

Epitype: fig. 3o designated in Łukomska‐Kowalczyk et al. 2020.

Representative DNA sequence: GenBank MK534200.

Lepocinclis fusca (G.A. Klebs) Kosmala & Zakryś in Kosmala et al. 2005: 1264, figure 1A.

Holotype: Designated herein, Klebs 1883, pl. 3, figure 13.

Epitype: figure 1A in Kosmala et al. 2005 designated herein that supports the holotype (Klebs 1883, pl. 3, fig. 13).

Representative strain: ACOI 1414.

Representative DNA sequence: GenBank AY935691.

Comments: As the epitypification statement published in Kosmala et al. 2005 (p. 1264) does not include the phrase “designated here” (or an equivalent), thus the nomenclatural act has not been effected in accordance with ICN Art. 7.11 (Turland et al. 2018) and is designated herein.

Lepocinclis fusiformis (H.J. Carter) Lemmermann 1901: 89.

Epitype: figure 3l designated in Łukomska‐Kowalczyk et al. 2020.

Representative DNA sequence: GenBank AY935697.

Lepocinclis globosa Francè 1893: 94, pl. 2, figure 4.

Epitype: figure 3e designated in Łukomska‐Kowalczyk et al. 2020.

Representative DNA sequence: GenBank MK534208.

Lepocinclis globulus Perty 1849: 28.

Epitype: figure 3d designated in Łukomska‐Kowalczyk et al. 2020.

Representative DNA sequence: GenBank MK534218.

Lepocinclis gracilicauda (Deflandre) Zakryś & M.Łukomska in Łukomska‐Kowalczyk et al. 2020: 291, figure 3p.

Epitype: figure 3p designated in Łukomska‐Kowalczyk et al. 2020.

Representative DNA sequence: GenBank MK534224.

Lepocinclis gracillimoides Zakryś & Chaber nom. nov. (Fig. 3b ).

Nomen novum: Lepocinclis gracillimoides (≡ E. oxyuris var. gracillima Playfair 1921, Proc. Linnean Soc. N. S. Wales 46 (1): 119, pl. 3, fig. 19), non Lepocinclis gracillima W. Conrad 1935, Mémoire du Musée Royal d'Histoire Naturelle de Belgique 21: 67, fig. 64.

Etymology: The name gracillimoides refers to the name gracillima.

Emended diagnosis: Cells elongated cylindrical (220–330 × 17–30 µm), hardly metabolic, slightly flattened, with a furrow running the entire length of the cell; apically widely rounded, in the back gradually narrowing and terminated with a sharp hyaline tail (on average 32–50 µm). Two large, rod‐shaped paramylon grains, one of which is in front of and the other behind the nucleus. Flagellum is very short, which often results in a lack of movement.

Holotype: Playfair 1921, pl. 3, figure 19 (see Fig. S6 in the Supporting Information).

Epitype: Figure 3b designated herein that supports the holotype (Playfair 1921, pl. 3, fig. 19).

Type locality: freshwater ponds, Australia.

Representative DNA sequence: GenBank MW730866, MW730842.

Representative locality: Eutrophic park pond (Schneider’s Pond) in Jelonki (district of Warsaw, Poland).

Homotypic synomyms: Euglena oxyuris f. gracillima (Playfair) Popova 1955: 180; Lepocinclis oxyuris var. gracillima (Playfair) D.A. Kapustin 2011: 140.

Heterotypic synomyms: Euglena antefossa L.P. Johnson 1944: 108 and 109, fig. 7, A and B. E. oxyuris var. major Woronichin in Popova 1947: 50; L. oxyuris f. major (Woronichin) Wołowski 2011: 200; L. oxyuris var. major (Woronichin) D.A. Kapustin 2011: 139.

Comments: Following the nomenclatural priority rule, this morphological form has been assigned the name Euglena oxyuris var. gracillima. As the name Lepocinclis gracillima is already taken by a species of a different morphology (Lepocinclis gracillima W. Conrad 1935), we propose L. gracillimoides nomen novum. The morphological features of the individual seen in Playfair’s drawing (1921, pl. 3, fig. 19 ‐ see Fig. S6) correspond with those of the members of Polish populations (cells about 300 µm long with two large, rod‐like paramylon grains). However, due to the many controversies found in the literature regarding the morphology of this species and the justification of its distinguishment, we believe that designating an epitype is necessary (for more details see Discussion). All species included as L. gracillimoides synonyms have large cells (over 220 µm long), a furrow and two large paramylon grains.

Lepocinclis hispidula (Eichwald) Daday 1905: 32.

Epitype: figure 3u designated in Łukomska‐Kowalczyk et al. 2020.

Representative DNA sequence: GenBank MK534232.

Lepocinclis longissima (Deflandre) Zakryś & Chaber comb. nov. (Fig. 3g).

Emended diagnosis: Cells rigid, cylindrical, strongly elongated (250–350 × 8–16 µm), apically narrowed and elongated into a “snout”; posterior narrowed, terminated with a sharp hyaline tail (on average 35–50 µm). Several large, rod‐shaped, paramylon grains scattered in the cell. Periplast longitudinally striated.

Basionym: Euglena acus var. longissima Deflandre 1924, Rev. Algol. 1: 242, pl. 4, figs. 1, 2, 3.

Lectotype: Designated herein, Deflandre 1924, pl. 4, fig. 3 (see Fig. S7 in the Supporting Information).

Epitype: Figure 3g designated herein that supports the lectotype (Deflandre 1924, pl. 4, fig. 3).

Type locality: France, Rambouillet, Etang d'Or Pond (= Gold Pond).

Representative DNA sequences: GenBank MW730870, MW730845, MW748163.

Representative locality: Fish pond in Piorunów village.

Homotypic synonyms: Lepocinclis acus var. longissimia D. Kapustin 2011: 138.

Heterotypic synonyms: Euglena acutissima var. longa Johnson 1944: 113 and 114, figs. 13c‐e; E. acus var. longa Gojdics 1953: 99.

Comments: Polish populations of Lepocinclis longissima have been identified based on cell size and the longitudinal striation of the periplast. In his diagnostic description, Deflandre (1924) describes the cells as “spindle‐like”. However, the individuals portrayed in his drawings represent many shapes: spindle‐like (fig. 1), fusiform (fig. 2), and cylindrical (fig. 3), the last herein designated as the lectotype (see Fig. S7). Specimens of Polish populations had cylindrical cells. In the case when the cell shape is a major diagnostic trait discerning L. longissima from L. acus, the designation of an epitype for both species seems justified (for more details see Discussion and Comments for L. acus). The taxa that constitute L. longissima synonyms are those whose cell morphology corresponds to the emended diagnostic description.

Lepocinclis marssonii Lemmermann 1905: 151, pl. 4, figure 9.

Epitype: figure 3s designated in Łukomska‐Kowalczyk et al. 2020.

Representative DNA sequence: GenBank MK534233.

Lepocinclis oxyuris var. oxyuris (Schmarda) B. Marin & Melkonian in Marin et al. 2003: 104 (Fig. 3c ).

Emended diagnosis: Cells cylindrical (on average 135–210 × 16–22 µm), slightly flattened, hardly metabolic, apically rounded, posterior terminated with a sharp hyaline tail (on average 17–30 µm). A furrow runs the entire length of the cell. Flagellum (usually shorter than the length of the cell) allows active swimming; when motile, the cells show a tendency for slight spiral twisting. Two large, ring‐shaped paramylon grains, one of which is in front of and the other behind the nucleus; small grains very few in number (rod‐like, oval, ring‐like), scattered in the cytoplasm.

Lectotype: designated herein, Schmarda 1846, pl. 1, fig. II. 4 (see Fig. S8 in the Supporting Information).

Type locality: Austria, mountain spring, Ilölieu between Steinriegel and Weidling.

Representative DNA sequence: GenBank MW748167, MW730883, MW730849.

Representative locality: Eutrophic pond in Moczydło Park in Warsaw.

Heterotypic synonyms: Euglena charkowiensis Svirenko 1913: 74, 86, pl. 1, fig. 21; E. charkowiensis var. lata Christjuk 1947: 256, figs 1, 4, 17, 18; E. oxyuris f. charkowiensis (Svirenko) Bourrelly 1949: 615; E. oxyuris f. lata (Christjuk) T.G. Popova 1966: 308, pl. 36, fig. 10; Euglena estonica K. Mölder 1943: 12, pl. 1 fig. 8.

Comments: Of the seven drawings by Schmarda, image II‐4 depicts best the important diagnostic traits to which he draws attention to in his description (cylindrical cell shape and two ring‐like paramylon grains located on either side of the nucleus), which is why this image has been designated as the lectotype (see Fig. S8). The taxa that constitute Lepocinclis oxyuris synonyms are those, whose cell morphology corresponds to the emended diagnostic description.

Lepocinclis oxyuris var. helicoidea (C. Bernard) Zakryś & Chaber comb. nov. (Fig. 3d ).

Emended diagnosis: Cells elongated cylindrical (240–530 × 29–43 µm), slightly flattened, hardly metabolic, apically rounded, posteriorly terminated with a sharp hyaline tail (23–40 µm). Furrow long, reaching all the way to the tail. Several (usually 12–15) large rod‐shaped paramylon grains located in groups on both sides of the nucleus. Flagellum is very short (or nonexistent) which causes a lack of motility.

Basionym: Phacus helicoideus Bernard 1908, Protococcacées et Desmidiées: 206, fig. 563 (see Fig. S9 in the Supporting Information).

Representative DNA sequences: GenBank MW730876, MW730847, MW748165.

Representative locality: Eutrophic park pond Glinianki Włościańskie in Warsaw.

Homotypic synonyms: Phacus helicoideus C. Bernard 1908: 206, fig. 563; Euglena oxyuris var. helicoidea (C. Bernard) Playfair 1921: 119; E. helicoideus (C. Bernard) Gojdics 1953: 119.

Heterotypic synonyms: Euglena gigas Drezepolski 1925: 243 and 267, fig. 159; E. oxyuris var. major Woronichin in T.G. Popova 1947: 50; E. oxyuris f. major (Woronichin) T.G. Popova 1966: 308.

Comments: The cell size (on average 400 µm long) and the presence of several large rod‐shaped paramylon grains have allowed the identification of Polish members of Lepocinclis oxyuris var. helicoidea. The taxa that constitute L. oxyuris var. helicoidea synonyms are those, whose cell morphology corresponds to the emended diagnostic description.

Lepocinclis ovum (Ehrenberg) Lemmermann 1901: 88.

Lectotype: Ehrenberg’s unpublished drawing no. 551 (Zakryś et al. 2020).

Epitype: figure 3a in Łukomska‐Kowalczyk et al. 2020 designated in Zakryś et al. 2020.

Representative strain: SAG 1244‐8.

Representative DNA sequence: GenBank AF110419.

Lepocinclis pseudofominii (Svirenko) Zakryś & M.Łukomska in Łukomska‐Kowalczyk et al. 2020: 292, figure 3m.

Epitype: fig. 3m designated in Łukomska‐Kowalczyk et al. 2020.

Representative DNA sequence: GenBank MK534235.

Lepocinclis pseudospiroides (Svirenko) Zakryś & Chaber comb. nov. (Fig. 3 l and m).

Emended diagnosis: The rigid, corkscrew‐like cells resemble in shape those of Lepocinclis tripteris, however are twice as large (131–230 × 12–25 µm, hyaline tail 16–36 µm long). The spiral twists of the body are loose, but more numerous (usually there are three) as the cells are longer. Periplast longitudinally striated. Two large, rod‐shaped paramylon grains (one of which is in front of and the other behind the nucleus).

Basionym: Euglena pseudospiroides Svirenko 1915b: Arch. Hydrobiol. und Planktonkunde, 10: 323; pl. 4, figures 1, 2, 3.

Lectotype: designated herein, Svirenko 1915b, pl. 4, fig. 1 (see Fig. S10 in the Supporting Information).

Epitype: Figure 3l designated herein that supports the lectotype (Svirenko 1915b, pl. 4, fig. 1).

Type locality: Kharkiv district, See Lyman, river Lipow; Tomsk district, See Ostabnoje, Russia (currently Ukraine).

Representative DNA sequences: GenBank MW730896, MW730855.

Representative locality: Eutrophic pond in Izdebno Nowe village.

Homotypic synonym: Euglena tripteris var. major Svirenko 1915a: 98, 129, tab. 2 figs 1, 2, 3.

Heterotypic synonym: Euglena trisulcata L.P. Johnson 1944: 106, pl. 1, fig. 5.

Comments: Polish populations were identified based on the cell size and the level of “body twisting”. Out of three drawings by Svirenko (see Fig. S10), fig. 1, was chosen as the lectotype, as the corkscrew‐shaped cell visibly has three wings (is triangular in cross section), is slightly twisted and possesses two rod‐like paramylon grains. Due to the similarity between Lepocinclis pseudospiroides and other taxa from the L. tripteris‐like group (e.g., L. tripteris or L. torta), the designation of an epitype seems justified (for more details see Discussion section). Euglena trisulcata has been included as a L. pseudospiroides synonym due to the similar cell size and lack of other diagnostic traits that would distinguish the two species.

Lepocinclis sphagnophila Lemmermann 1904: 124.

Epitype: figure 3k designated in Łukomska‐Kowalczyk et al. 2020.

Representative DNA sequence: GenBank MK534239.

Lepocinclis spirogyroides B. Marin & Melkonian in Marin et al. 2003: 104 (new name for Euglena spirogyra Ehrenberg).

Lectotype: Designated herein figure “d” on Ehrenberg’s unpublished drawing no. 557 in the Ehrenberg Collection (Institut für Paläontologie, Museum für Naturkunde, Humboldt Universität zu Berlin, Invalidenstr. 43, D‐10115 Berlin, Germany).

Epitype: figure 1B in Kosmala et al. 2005 designated herein that supports the lectotype (figure “d” on Ehrenberg’s unpublished drawing ECdraw557).

Representative strain: SAG 1224‐13b.

Representative DNA sequence: GenBank AY935694.

Type locality: Germany, Berlin (Euglena spirogyra Ehrenberg) (according to Index Nominum Algarum).

Comments: As the epitypification statements published in Kosmala et al. 2005 (p. 1263) do not include the phrase “designated here” (or an equivalent), thus the nomenclatural act has not been effected in accordance with ICN Art. 7.11 (Turland et al. 2018) and is conducted herein. We now designate the individual labeled as “d” in Ehrenberg’s unpublished drawing no. 557, where two representatives of morphologically similar species are depicted: Lepocinclis spirogyroides (figs. a‐e) and L. fusca (fig. f). According to current knowledge, the two species differ in terms of cell size and shape as well as the morphology of mucocysts (Kosmala et al. 2005). In this case, the designation of an epitype and lectotype for L. spirogyroides seems justified. The individual labeled “d” corresponds best with the diagnostic description of E. spirogyra (for more details see Discussion in Kosmala et al. 2005).

Lepocinclis steinii Lemmermann 1904: 123.

Epitype: figure 3i designated in Łukomska‐Kowalczyk et al. 2020.

Representative DNA sequence: GenBank FJ719620.

Lepocinclis torta (A. Stokes) Zakryś & Chaber comb. nov. (Fig. 3 h and i).

Emended diagnosis: The rigid, corkscrew‐like cells resemble Lepocinclis tripteris in terms of shape, however are slightly smaller (63.5–93.5 × 10–19 µm), more twisted (two to three twists per length) and visibly spindle‐shaped in overview; hyaline tail 11–20 µm long. Periplast longitudinally striated. Two large, rod‐shaped paramylon grains (one of which is in front of and the other behind the nucleus).

Basionym: Euglena torta A. Stokes 1885, Am. Naturalist 19: 19, figure 1.

Holotype: Stokes 1885, figure 1 (see Fig. S11 in the Supporting Information).

Epitype: Figure 3h designated herein that supports the holotype (Stokes 1885, fig. 1).

Type locality: Shallow ponds in Western New York.

Representative DNA sequences: GenBank MW730899, MW730856, MW748172.

Representative locality: Eutrophic pond in Izdebno Nowe village.

Heterotypic synonyms: Euglena tripteris var. crassa Svirenko 1915a: 100, pl. 2, figures 12‐14; 1915b: 325, pl. 1, figures 12‐14, Euglena torta Korshikov 1941: 24, figure 2.

Comments: Polish populations of Lepocinclis torta were identified based on the twisted cells and the clade’s location on the phylogenetic tree, as it groups sequences representing this particular morphological form. Due to the similarity of L. torta to L. tripteris, the designation of an epitype is justified. Euglena tripteris var. crassa has been included as a L. torta synonym as no diagnostic traits have been found that would distinguish the two species.

Lepocinclis tripteris (Dujardin) B. Marin & Melkonian in Marin et al. 2003: 104 (Fig. 3 j and k).

Emended diagnosis: Cells are rigid (102–121 × 11–19 µm), triangular in cross section with visibly concave sides, which results in three convex edges (or wings) running the length of the entire slightly spirally twisted cell; this resembles a loosely twisted corkscrew (usually 1–1.5 twist per length). In overview, the body is fusiform, apically slightly narrowed and rounded, posteriorly ending with a sharp, hyaline tail (13–22 µm). Periplast longitudinally striated. Two large, rod‐shaped paramylon grains (one of which is in front of and the other behind the nucleus).

Holotype: Dujardin 1841, pl. 5, fig. 7 (see Fig. S12 in the Supporting Information).

Epitype: Figure 3j designated herein that supports the holotype (Dujardin 1841, pl. 5, fig. 7).

Type locality: France, south of Paris, freshwater, Mandon pond.

Representative DNA sequences: GenBank MW730901, MW748174.

Representative locality in Poland: Eutrophic pond in Cielądz village.

Homotypic synonyms: Phacus tripteris Dujardin 1841: 338, pl. 5, figure 7; Euglena tripteris (Dujardin) G.A. Klebs 1883: 306.

Heterotypic synonyms: Euglena tripteris var. klebsii Lemmermann 1910: 497; E. fronsundulata L.P. Johnson 1944: 105, pl. 1, figure 3.

Comments: Polish populations of Lepocinclis tripteris were identified based on the cell shape (triangular in cross section) caused by the presence of three convex edges (or wings) present along the cell length. This is clearly visible in the drawing of a representative by Dujardin (1841, pl. 5, fig. 7 see Fig. S12) and is included in the diagnostic description. On the other hand, nothing is mentioned regarding the spiral twisting of the body and it is invisible in Dujardin’s drawing (see Fig. S12). Due to the aforementioned, as well as the similarity of L. tripteris to L. pseudospiroides and other taxa from the L. tripteris‐like group, the designation of an epitype seems justified (for more details see Discussion section). Euglena tripteris var. klebsii and E. fronsundulata have been included as L. tripteris synonyms as no diagnostic traits have been found that would distinguish the three species.

DISCUSSION

Lepocinclis acus‐like group of taxa.

Lepocinclis acus (as Euglena acus) was one of the first euglenid species known to science (Ehrenberg 1830). However, since then, several taxa at various levels (species, varieties, and forms) have been described, varying in cell size and shape, as well as the shape and number of large paramylon grains (see Gojdics 1953, Huber‐Pestalozzi 1955, Pringsheim 1956, Popova 1966; AlgaeBase https://www.algaebase.org). The authors of critical monographs agree that distinguishing twelve taxa is pointless. Pringsheim (1956) justified the existence of only four varieties (typica: 104–109 × 10–11 µm; major: 120–132 × 10–12 µm; gracilis: 108–112 × 6–7 µm; longissima: 159–162 × 17–18 µm); Gojdics (1953) suggests that three are correct (typica: 150–310 × 12–14.9 µm; angularis: 52–175 × 8–18 µm and longa: 220–350 × 10–13.5 µm); and Popova (1966) also agrees on three (typica: 87–197 × 7–17.4 µm, minor: 47.8–80 × 5–9.8 µm, longissima: over 220 µm).

In the diagnostic description, Ehrenberg describes the body shape of Euglena acus representatives as fusiform. Furthermore, the majority of individuals visible on the original pencil drawing no. 546 by Ehrenberg displays a spindle‐like shape (see Fig. S5). Ehrenberg notes the length of cells as 58–155 µm. On the phylogenetic trees (Figs. 2 and S4), the strains/isolates forming the acus clade (A) possess fusiform cells around 100–160 µm in length (see Figs. 3a and S1a; Table 1). The second clade (B) groups the Polish isolates, the representatives of which have very long (on average 300 µm), cylindrical cells (Figs. 3g, S1b; Table 1). Such a morphological form was first described from France under the name E. acus var. longissima Deflandre 1924 (250–311 × 8.5–12 µm), and later from the USA as E. acutissima var. longa (Johnson 1944), considered by Gojdics (1953) as a variety of E. acus (E. acus var. longa). Taking into account the priority of the name longissima, such a name was given to clade B, which groups the Polish isolates. In Poland, in small hyper‐ and eutrophic water bodies L. acus is common, while L. longissima is found often. Both may exist in dense populations and are often noted together (see Table S5, Figs. 2, S4 with L. acus isolates: UW2444Pio, UW2462Mak, UW2554BWo and L. longissima isolates: UW2443Pio, UW2460Mak, UW2553BWo).

Lepocinclis tripteris ‐like group of taxa.

Lepocinclis tripteris (60–80 µm long) was first described as Phacus tripteris Dujardin (1841), and later moved by Klebs (1883) to Euglena (as E. tripteris). A century later, E. fronsundulata (Johnson 1944) was described from the USA, which differed from E. tripteris only by a smaller size (42–53 × 4–7 µm) and a shorter flagellum. Similar form, though more tightly twisted, was described by Stokes from the USA (1885, as E. torta, 63.5 µm long) and also by Svirenko from Ukraine (1915a, as E. tripteris var. crassa, cells: 63–83 × 15–21 µm). The literature mentions two additional taxa that are identical to E. tripteris in terms of cell shape (loosely twisted), though twice as long. The first was described from Ukraine as E. tripteris var. major (Svirenko 1915a), and later elevated to the rank of species (E. pseudospiroides Svirenko 1915b, cells: 131–192 × 18–22 µm). The second was noted from the USA as E. trisulcata Johnson (1944, cells: 205–220 × 11–15 µm).

The authors of critical monographs interpret differently the validity of distinguishing taxa based on cell size and the degree of twisting: Pringsheim (1956) is very skeptical; Gojdics (1953) includes Euglena torta as a synonym of E. tripteris and distinguishes E. pseudospiroides, E. trisulcata and E. fronsundulata; Popova (1966) deems only three varieties of E. tripteris as valid (typica, crassa, and major), and treats E. torta (similarly to Gojdics) as a synonym var. typica, while neither E. trisulcata nor E. fronsundulata are mentioned by her. In Figure 2, the three morphologically different forms (see Figs. 3, h‐m and S2), that is slightly twisted, short (on average 100 µm), slightly twisted, long (on average 200 µm) and tightly twisted, short cells (on average 80 µm) occur as separate groups that have been named respectively: tripteris, pseudospiroides and torta (Figs. 2, S4). Due to the aforementioned, the names of strains appearing until now on phylogenetic trees (Marin et al. 2003, Kosmala et al. 2005, Bennett and Triemer 2012, Kim et al. 2015, Łukomska‐Kowalczyk et al. 2020) have been changed accordingly (MI 101, SAG 1224‐16, UTEX 1311 and UWOB) from L. tripteris to L. torta.

Lepocinclis oxyuris‐ like group of taxa.

Lepocinclis oxyuris (as Euglena oxyuris) was described by Schmarda in 1846 from Austria. According to Schmarda, oxyuris cells are cylindrical, slightly flattened (tape‐like), large (180 × 22.5 µm), terminated with a sharp tail and possess two ring‐like paramylon grains. Since then, many taxa (species, varieties and forms — see AlgaeBase https://www.algaebase.org) have been described in the literature with a morphology similar to L. oxyuris. A key diagnostic trait for L. oxyuris is the presence of an indentation (so‐called furrow), running the length of the cell. Attention to this feature, however, is only made later by other researchers (Svirenko 1913, Gojdics 1953, Pringsheim 1956, Popova 1966, this study). Seven taxa possess such a furrow in the L. oxyuris‐like group, but differ in cell size and shape and in the number and shape of large paramylon grains: E. charkoviensis, E. estonica (possesses two ring‐like paramylon grains, cells 100–200 µm long); E. oxyuris var. gracillima, E. antefossa (two rod‐like paramylon grains, cells about 300 µm long) and E. oxyuris var. helicoidea (= E. helicoideus), E. oxyuris var. major, E. gigas (possesses a few rod‐like paramylon grains, cells 300–500 µm long). The validity of distinguishing the aforementioned taxa has been questioned by many researchers, similar to discriminating many intraspecific taxa (forms and varieties) of E. oxyuris. Pringsheim (1956) believes that there is only one, well‐defined species — E. oxyuris — that is very morphologically diverse. Popova (1966) distinguishes five forms of E. oxyuris based on cell size (typica, gracillima, lata, major and skvortzovii) and synonymizes the remaining taxa in the literature with one of the forms, regardless of the shape and size of the large paramylon grains. Gojdics (1953) seems inconsistent in this matter, as on one hand, she agrees with the validity of distinguishing E. antefossa and E. helicoideus (see Gojdics 1953: p. 119–120, pl. 17 fig. 3 and pl.18, fig. 1), while on the other, she treats the number and shape of paramylon grains as a variable trait in E. oxyuris (compare Gojdics 1953, pl.18, fig. 1 and pl. 20, figs. 1, a and b).

Based on morphological‐molecular research, Bennett and Triemer (2012) moved two species (Euglena oxyuris and E. helicoideus) to the genus Lepocinclis (now L. oxyuris, L. helicoidea). The two species have then grouped in a common clade in the phylogenetic tree (Bennett and Triemer 2012, p. 255 and Fig. 2) regardless of their differing morphologies (see Figs. 3, c and d, S3, a and b; Table 1). Historically, L. helicoidea was first described as a representative of Phacus (P. helicoideus Bernard 1908), but was later moved to Euglena (as E. oxyuris var. helicoidea Playfair 1921) and then elevated to the rank of species (as E. helicoideus Gojdics 1953). Soon after (and independently of the others) Drezepolski (1925) described the same species again (from Poland), giving it the name E. gigas due to its particularly large size — it is the largest known euglenid, reaching 500 µm in length. Surprisingly, after adding several sequences, both morphological forms (oxyuris and helicoidea) have remained together (see clade F on Figs. 2 and S4). This is unprecedented among autotrophic euglenids, as so far there had not been a case where a clade grouping morphologically almost indistinguishable isolates/strains was disrupted by a subclade, comprising such a unique form. Due to the aforementioned, a variety of L. oxyuris (L. oxyuris var. helicoidea) was distinguished, based on the preceding concept by Playfair (E. oxyuris var. helicoidea). Moreover, several sequences of Polish isolates identified from the literature as E. oxyuris var. gracillima have been grouped in a common, well‐supported clade (clade G on Figs. 2 and S4). As a result, the variety has been elevated to the rank of species. Due to the name gracillima being already taken, it was given a new one — L. gracillimoides (for more details see Taxonomic revisions). In terms of size and motility (lack of flagellum or flagellum very short), L. oxyuris var. helicoidea and L. gracillimoides are very similar, but differ in the number of large paramylon grains (L. oxyuris var. helicoidea — (12–15), L. gracillimoides— two; see Figs. 3, b and d and S3, b and c). Lepocinclis gracillimoides was first described from Australia (as E. oxyuris var. gracillima; Playfair 1921) and later from the USA as E. antefossa (Johnson 1944). All three morphological forms (oxyuris, helicoidea, and gracillimoides) are considered cosmopolitan, though not always common (Drezepolski 1925, Pringsheim 1956, Popova 1966, Popova and Safonova 1976, Starmach 1983, Tell and Conforti 1986, Bennett and Triemer 2012 among others). In Poland, L. oxyuris var. helicoidea and L. gracillimoides appear often, but hardly ever in high densities, while L. oxyuris is very common and is found often in dense populations. Both taxa often coexist in the same reservoirs (see Table S5).

Lepocinclis convoluta (as Euglena convoluta) was described from Russia (Korshikov 1941). It was found near the Biological Station of the State University of Gorky (Gorky District), in pools with Sphagnum on a bank of a small river, Seryosha, among flocks of benthic Cyanophyceae. Almost at the same time, it was described by Prescott and Gojdics from the USA under the name E. brevifflagellum from a pond in Massachusetts and Trilby Lake in Wisconsin (Prescott 1944). Not long after Gojdics (1953, p. 115, pl. 16, fig. 1, a‐c) deemed E. brevifflagellum a synonym of E. convoluta, as the unique morphology of this species (bolt‐like, twisted cells and distinctive paramylon grains in the form of concave plates, laterally arranged in the cell) left no doubts that the two findings were identical. It is a very rare species — so far, only three observations exist: one from the USA (Prescott 1944, Ciugulea and Triemer 2010, p. 24, figs. A‐F) and two from Europe (Korshikov 1941 and this study). The morphology of L. convoluta representatives from Poland corresponds exactly with the findings from Russia and the USA. The Polish population of L. convoluta exists in a few small, eutrophic waterbodies located in the Mazurian Lake District in the vicinity of Urwitałt village. The sequence of this species (isolate UW1666Ur13) has an unstable position on the phylogenetic tree (see Figs. 2 and S4), though it certainly remains within Lepocinclis.

Author Contributions

K. Chaber: Data curation (equal); Formal analysis (lead); Investigation (equal); Visualization (equal); Writing‐original draft (equal); Writing‐review & editing (equal). M. Łukomska‐Kowalczyk: Data curation (supporting); Formal analysis (supporting); Investigation (supporting); Methodology (supporting); Supervision (supporting); Writing‐review & editing (supporting). A. Fells: Investigation (supporting); Writing‐review & editing (equal). R. Milanowski: Conceptualization (supporting); Supervision (supporting); Writing‐review & editing (supporting). B. Zakryś: Conceptualization (lead); Data curation (equal); Funding acquisition (lead); Investigation (equal); Project administration (lead); Resources (lead); Supervision (equal); Visualization (equal); Writing‐original draft (lead); Writing‐review & editing (supporting).

Supporting information

Figure S1. Isolates of (a) Lepocinclis acus and (b) L. longissima.

Figure S2. Isolates of (a) Lepocinclis pseudospiroides, (b) L. torta and (c) L. tripteris.

Figure S3. Isolates of (a) Lepocinclis oxyuris, (b) L. oxyuris var. helicoidea and (c) L. gracillimoides.

Figure S4. Consensus Bayesian tree based on 106 nSSU rDNA sequences.

Figure S5. Ehrenberg’s unpublished drawing no. 546 (Ecdraw546) of Euglena acus; lectotype of Lepocinclis acus.

Figure S6. The original drawing of Euglena oxyuris var. gracillima, Playfair 1921, pl. 3, fig. 19; holotype of Lepocinclis gracillima.

Figure S7. The original drawing of Euglena oxyuris var. longissima, Deflandre 1924, pl. 4, fig. III; lectotype of Lepocinclis longissima.

Figure S8. The original drawing of Euglena oxyuris, Schmarda 1847, pl. 1, fig. II. 4; lectotype of Lepocinclis oxyuris.

Figure S9. The original drawing of Phacus helicoideus, Bernard 1908, pl. 16, fig. 563; holotype of Lepocinclis helicoidea.

Figure S10. The original drawing of Euglena pseudospiroides, Swirenko 1915b, pl. 4, figs. 2; lectotype of Lepocinclis pseudospiroides.

Figure S11. The original drawing of Euglena torta, Stokes 1885, fig. 1; holotype of Lepocinclis torta.

Figure S12. The original drawing of Euglena tripteris, Dujardin 1841, pl. 5, fig. 7; holotype of Lepocinclis tripteris.

Table S1. List of species and sampling data of isolates/strains used in this study.

Table S2. The nuclear SSU rDNA pair‐wise sequence distance (%) among studied strains and isolates of Lepocinclis acus and L. longissima.

Table S3. The nuclear SSU rDNA pair‐wise sequence distance (%) among studied strains and isolates of Lepocinclis pseudospiroides, L. torta and L. tripteris.

Table S4. The nuclear SSU rDNA pair‐wise sequence distance (%) among studied strains and isolates of Lepocinclis oxyuris var. oxyuris, L. oxyuris var. helicoidea and L. gracillimoides.

Table S5. Coexistence of Lepocinclis species in the studied water bodies: (#) present on the phylogeny tree, (+) absent on the phylogeny tree.

This work was supported by the OPUS 2016/23/B/NZ8/00919 grant from the National Science Centre, Poland. We thank Prof. Richard Triemer, MI, USA, for providing the photograph of L. oxyuris var. helicoidea (MSU). We are also grateful for the input of the anonymous Reviewer and Paul W. Gabrielson, who have been a great help in improving the manuscript. The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

References

- Bennett, M. S. & Triemer, R. E. 2012. A new method for obtaining nuclear gene sequences field samples and taxonomic revisions of the photosynthetic euglenoids Lepocinclis (Euglena) helicoideus and Lepocinclis (Phacus) horridus (Euglenophyta). J. Phycol. 48:254–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard, C. 1908. Protococcacées et Desmidiées d'eau douce, récoltées à Java. Departm. De l’agriculture aux Indes Neerlandaises, Batavia, p 230. [Google Scholar]

- Bourrelly, P. 1949. Euglena oxyuris Schmarda et formes affines. Bulletin Du Museum National D'histoire Naturelle, Série 2:612–6. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley, R. K. , Roberts, A. , Smoot, M. , Juvekar, S. , Do, J. , Dewey, C. , Holmes, I. & Pachter, L. 2009. Fast statistical alignment. PLoS Comput. Biol. 5:e1000392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capella‐Gutierrez, S. , Silla‐Martinez, J. M. & Gabaldon, T. 2009. TrimAl: A tool for automated alignment trimming in large‐scale phylogenetic analyses. Bioinformatics 25:972–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christjuk, P. M. 1947. Novye vodorosli iz vodoyomov Kryma [New algae from the water bodies of Crimea]. Trudy Krymsk. sel.‐choz . Inst. Im. M. I. Kalinina 2:253–8 (in Russian). [Google Scholar]

- Chu, S. P. 1936. On new and rare species of Lepocinclis . Sinensia 7:266–92. [Google Scholar]

- Ciugulea, I. & Triemer, R. E. 2010. A color atlas of photosynthetic Euglenoids. Michigan State University Press, East Lansing, p 204. [Google Scholar]

- Conrad, W. 1934. Matèriaux puor une monographie du genre Lepocinclis Perty. Arch. Protistenk 82:203–49. [Google Scholar]

- Conrad, W. 1935. Ètude systématique du genre Lepocinclis Perty. Mem. Mus. Royal D’hist. Nat. Belg. 2:1–84. [Google Scholar]

- Daday, E. 1905. Untersuchungen über die Süsswasser Microfauna Paraguays. Zoologica 18:1–349. [Google Scholar]

- Darriba, D. , Posada, D. , Kozlov, A. M. , Stamatakis, A. , Morel, B. & Flouri, T. 2020. ModelTest‐NG: a new and scalable tool for the selection of DNA and protein evolutionary models. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1:291–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deflandre, G. 1924. A propos de l'Euglena acus Ehrenb. Rev. Algol. 1:235–42. [Google Scholar]

- Drezepolski, R. 1925. Przyczynek do znajomości polskich Euglenin [Supplément à la connaissance des Eugléniens de la Pologne]. Kosmos 50:173–270 (in Polish with French summary). [Google Scholar]

- Dujardin, F. 1841. Historie naturelle des zoophytes infusoires: comprenant la physiologie et la classification de ces animaux et la manière de les etudier a l’aide du microscope. Libraire encyclopedique de Roret, Paris, p 684. [Google Scholar]

- Ehrenberg, C. G. 1830. Neue Beobachtungen über blutartige Erscheinungen in Aegypten, Arabien und Sibirien, nebst einer Uebersicht und Kritik der früher bekannten. Annalen Der Physik Und Chemie 8:477–514. [Google Scholar]

- Ehrenberg, C. G. 1831. Über die Entwickelung und Lebensdauer der Infusionsthiere; nebst ferneren Beiträgen zu einer Vergleichung ihrer organischen Systeme. Physikalishe Abhandlungen Königlichen Akademie Der Wissenschaften Zu Berlin 1832:1–154. [Google Scholar]

- Francè, H. R. 1893. Uj ostoros‐ázalékállatkák a Balatonból. Természetrajzi Füzetek 16:89–97 (in Hungarian). [Google Scholar]

- Gojdics, M. 1953. The genus Euglena. The University of Wisconsin Press, Madison, Wisconsin, p 268. [Google Scholar]

- Gouy, M. , Guindon, S. & Gascuel, O. 2010. SeaView version 4: a multiplatform graphical user interface for sequence alignment and phylogenetic tree building. Mol. Biol. Evol. 27:221–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guiry, M. D. & Guiry, G. M. 2021. AlgaeBase. World‐wide electronic publication. National University of Ireland, Galway: searched on 13 May 2021 https://www.algaebase.org. [Google Scholar]

- Hansgirg, A. 1892. Prodromus der Algenflora von Böhmen. Zweiter Teil. Arch Naturwiss Durchforsch Von Böhmen 8:1–266. [Google Scholar]

- Hüber‐Pestalozzi, G. 1955. Das Phytoplankton des Süsswassers; Systematik und Biologie: 4 Teil. Schweizerbartsche Verlagsbuchhandlung, Stuttgart, Germany, Euglenophyceen. E, p 606. [Google Scholar]

- Hübner, E. F. W. 1886. Euglenaceenflora von Stralsund Program d. Realgymnasiums zu Stralsund. K. Regierungs‐buchdruckerei, 1–20. Stralsund, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, L. P. 1944. Euglena of Iowa. Trans. Am. Microsc. Soc. 63:97–135. [Google Scholar]

- Kapustin, D. A. 2011. New nomenclature and taxonomical combinations within euglenophytes. Algologia 21:137–44 (in Ukrainian). [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J. I. , Linton, E. W. & Shin, W. 2015. Taxon‐rich multigene phylogeny of the photosynthetic euglenoids (Euglenophyceae). Front. Ecol. Evol. 3:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J. I. , Shin, W. & Triemer, R. E. 2010. Multigene analyses of photosynthetic euglenoids and new family, Phacaceae (Euglenales). J. Phycol. 46:1278–87. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J. I. , Shin, W. & Triemer, R. E. 2013. Cryptic speciation in the genus Cryptoglena (Euglenaceae) revealed by nuclear and plastid SSU and LSU rDNA gene. J. Phycol. 49:92–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klebs, G. 1883. Über die Organisation einiger Flagellaten‐Gruppen und ihre Beziehungen zu Algen und Infusorien. Untersuchung Botan. Inst. Tübingen 1:233–362. [Google Scholar]

- Korshikov, A. A. 1941. On some new or little known flagellates. Arch. Protistenk 95:21–44 (in Ukrainian). [Google Scholar]

- Kosmala, S. , Karnkowska, A. , Milanowski, R. , Kwiatowski, J. & Zakryś, B. 2005. Phylogenetic and taxonomic position of Lepocinclis fusca comb. nov. (= Euglena fusca) (Euglenaceae): Morphological and molecular justification. J. Phycol. 41:1258–67. [Google Scholar]

- Kozlov, A. M. , Darriba, D. , Flouri, T. , Morel, B. & Stamatakis, A. 2019. RAxML‐NG: a fast, scalable and user‐friendly tool for maximum likelihood phylogenetic inference. Bioinformatics 21:4453–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, S. , Stecher, G. , Li, M. , Knyaz, C. & Tamura, K. 2018. MEGA X: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. Mol. Biol. Evol. 35:1547–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanave, C. , Preparata, G. , Saccone, C. & Serio, G. 1984. A new method of calculating evolutionary substitution rate. J. Mol. Evol. 20:86–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemmermann, E. 1901. Beiträge zur Kenntniss der Planktonalgen, XII: Notizen über einige Schwebealgen. Ber. Deutsch. Bot. Ges. 19:85–95. [Google Scholar]

- Lemmermann, E. 1904. Das Plankton Schwedischer Gewaesser. Arch. Bot. 2:1–209. [Google Scholar]

- Lemmermann, E. 1905. Brandenburgische Algen III. Neue Forschungsber Biol. Stat. Plön. 12:145–68. [Google Scholar]

- Lemmermann, E. 1910. Kryptogamenflora der Mark Brandenburg und angrenzender Gebiete III. Verlag von Gebrüder Borntraeger, Leipzig, Algen, p 712. [Google Scholar]

- Łukomska‐Kowalczyk, M. , Chaber, K. , Fells, A. , Milanowski, R. & Zakryś, B. 2020. Molecular and morphological delimitation of species in the group of Lepocinclis ovum‐like taxa (Euglenida). J. Phycol. 56:283–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Łukomska‐Kowalczyk, M. , Chaber, K. , Fells, A. , Milanowski, R. & Zakryś, B. 2021. Description of Flexiglena gen. nov. and new members of Discoplastis and Euglenaformis (Euglenida). J. Phycol. 57:766–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marin, B. , Palm, A. , Klingberg, M. & Melkonian, M. 2003. Phylogeny and taxonomic revision of plastid‐containing Euglenophytes based on SSU rDNA sequence comparisons and synapomorphic signatures in the SSU rRNA secondary structure. Protist 154:99–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mölder, K. 1943. Die Flagellaten und Dinoflagellaten flora Estlands. Annales Botanici Societatis Zoologicae Botanicae Fennicae, Vanamo, Helsinki 18:1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Pascher, A. 1927. Neue oder wenig bekannte Protisten XVIII. Arch. Protistenk 58:577–98. [Google Scholar]

- Perty, M. 1849. Über verticale Verbreitung mikroskopischer Lebensformen. Mitth. Naturf. Gesellsch. Bern 17–45. [Google Scholar]

- Playfair, G. J. 1921. Australian freshwater flagellates. Proc. Linn. Soc. 46:99–146. [Google Scholar]

- Popova, T. G. 1947. Sistematiceskije zametki po evglenovym [Taxonomical note about euglenophytes]. Izv. Zap. Sib. Fil. AN SSSR Ser. Biol. 2:47–71 (in Russian). [Google Scholar]

- Popova, T. G. 1955. Euglenovyje vodorosli. Opredelitel prosnovodnych vodoroslej SSSR, 7 [Euglenophyta. The handbook of freshwater algae]. Sov. Nauka, Moscow 267 pp (in Russian). [Google Scholar]

- Popova, T. G. 1966. Flora Sporovych Rastenij SSSR, 8. [Flora plantarum cryptogamarum URSS, 8]. Euglenophyta 1. Nauka, Moskva‐Leningrad 411 pp. (in Russian).

- Popova, T. G. & Safonova, T. A. 1976. Flora Sporovych Rastenij SSSR, 9. [Flora plantarum cryptogamarum URSS, 9]. Euglenophyta 2. Nauka, Moskva‐Leningrad, 286 pp. (in Russian).

- Prescott, G. W. 1944. New species and varieties of Wisconsin algae. Farlovia 1:347–73. [Google Scholar]

- Pringsheim, E. G. 1956. Contribution towards a monograph of the genus Euglena . Nova Acta Leopold 18:1–168. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team 2008. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria: https://www.R‐project.org/. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez, F. , Oliver, J. L. , Marin, A. & Medina, J. R. 1990. The general stochastic model of nucleotide substitution. J. Theor. Biol. 142:485–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronquist, F. & Huelsenbeck, J. P. 2003. MrBayes 3: Bayesian phylogenetic inference under mixed models. Bioinformatics 19:1572–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiller, J. 1925. Die planktonischen Vegetationen des adriatischen Meeres. B. Chrysomonadina, Heterokontae, Cryptomonadina, Eugleninae, Volvocales. 1. Systematischer Teil. (Nach den Ergebnissen der österreichischen Adriaforschung in den Jahren 1911–1914). Arch. Protistenk 53:59–123. [Google Scholar]

- Schmarda, L. K. 1846. Kleine Beiträge zur Naturgeschichte der Infusorien. Verlag der Carl Haas’schen Buchhandlung, Wien, p 61. [Google Scholar]

- Starmach, K. 1983. Euglenophyta ‐ eugleniny. In Starmach, K. & Sieminńska, J. (eds) Flora Słodkowodna Polski 3. P. W. N, Warsaw, p 594. [Google Scholar]

- Stokes, A. C. 1885. Some apparently undescribed Infusoria from fresh water. Am. Nat. 19:18–27. [Google Scholar]

- Svirenko, D. O. 1913. Pervyje zvedenija o flore okrasennych Flagellata okrestnostej . Travaux De La Société Des Naturalistes À L'université Impériale De Kharkow 46:67–90 (in Russian). [Google Scholar]

- Svirenko, D. O. 1915a. Matérial pour servir à l’étude des algues de la Russie. Étude systématique et géographique sur les Euglénacées. Trav. Inst. Bot. Univ. Charkov 48:67–143 (in Russian). [Google Scholar]

- Svirenko, D. O. 1915b. Zur Kenntnis der russischen Algenflora. 2. Euglenophyceae (excl. Trachelomonas). Arch. Hydrobiol. Planktonk. 10:321–40. [Google Scholar]

- Tavare, S. 1986. Some probabilistic and statistical problems on the analysis of DNA sequences. Lec. Math. Life Sci. 17:57–86. [Google Scholar]

- Tell, G. & Conforti, V. 1986. Euglenophyta pigmentadas de la Argentina. Bibliotheca Phycologica. J. CRAMER, Berlin, Stuttgart, 301 pp. [Google Scholar]

- Turland, N. J. , Wiersema, J. H. , Barrie, F. R. , Greuter, W. , Hawksworth, D. L. , Herendeen, P. S. , Knapp, S. et al. 2018. International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants (Shenzhen Code) Regnum Vegetabile 159. Koeltz Botanical Books, Glashütten, Glashütten. [Google Scholar]

- Wołowski, K. 2011. Phyllum Euglenophyta. In John, D. M. , Whitton, B. A. & Brook, A. J. (eds) The Freshwater Algal Flora of the British Isles: An Identification Guide to Freshwater and Terrestrial Algae. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 181–239. [Google Scholar]

- Zakryś, B. , Łukomska‐Kowalczyk, M. , Chaber, K. , Fells, A. & Milanowski, R. 2020. Typification of Lepocinclis ovum (Ehrenberg) Lemmermann (Euglenophyta), a widespread freshwater species. Notulae Algarum no 144.

- Zakryś, B. , Milanowski, R. , Empel, J. , Borsuk, P. , Gromadka, R. & Kwiatowski, J. 2002. Two different species of Euglena, E.geniculata and E.myxocylindracea (Euglenophyceae), are virtually genetically and morphologically identical. J. Phycol. 38:1190–9. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Isolates of (a) Lepocinclis acus and (b) L. longissima.

Figure S2. Isolates of (a) Lepocinclis pseudospiroides, (b) L. torta and (c) L. tripteris.

Figure S3. Isolates of (a) Lepocinclis oxyuris, (b) L. oxyuris var. helicoidea and (c) L. gracillimoides.

Figure S4. Consensus Bayesian tree based on 106 nSSU rDNA sequences.

Figure S5. Ehrenberg’s unpublished drawing no. 546 (Ecdraw546) of Euglena acus; lectotype of Lepocinclis acus.

Figure S6. The original drawing of Euglena oxyuris var. gracillima, Playfair 1921, pl. 3, fig. 19; holotype of Lepocinclis gracillima.

Figure S7. The original drawing of Euglena oxyuris var. longissima, Deflandre 1924, pl. 4, fig. III; lectotype of Lepocinclis longissima.

Figure S8. The original drawing of Euglena oxyuris, Schmarda 1847, pl. 1, fig. II. 4; lectotype of Lepocinclis oxyuris.

Figure S9. The original drawing of Phacus helicoideus, Bernard 1908, pl. 16, fig. 563; holotype of Lepocinclis helicoidea.

Figure S10. The original drawing of Euglena pseudospiroides, Swirenko 1915b, pl. 4, figs. 2; lectotype of Lepocinclis pseudospiroides.

Figure S11. The original drawing of Euglena torta, Stokes 1885, fig. 1; holotype of Lepocinclis torta.

Figure S12. The original drawing of Euglena tripteris, Dujardin 1841, pl. 5, fig. 7; holotype of Lepocinclis tripteris.

Table S1. List of species and sampling data of isolates/strains used in this study.

Table S2. The nuclear SSU rDNA pair‐wise sequence distance (%) among studied strains and isolates of Lepocinclis acus and L. longissima.

Table S3. The nuclear SSU rDNA pair‐wise sequence distance (%) among studied strains and isolates of Lepocinclis pseudospiroides, L. torta and L. tripteris.

Table S4. The nuclear SSU rDNA pair‐wise sequence distance (%) among studied strains and isolates of Lepocinclis oxyuris var. oxyuris, L. oxyuris var. helicoidea and L. gracillimoides.

Table S5. Coexistence of Lepocinclis species in the studied water bodies: (#) present on the phylogeny tree, (+) absent on the phylogeny tree.