Abstract

At Palmyra Atoll, the environmental DNA (eDNA) signal on tidal sand flats was associated with fish biomass density and captured 98%–100% of the expected species diversity there. Although eDNA spilled over across habitats, species associated with reef habitat contributed more eDNA to reef sites than to sand-flat sites, and species associated with sand-flat habitat contributed more eDNA to sand-flat sites than to reef sites. Tides did not disrupt the sand-flat habitat signal. At least 25 samples give a coverage >97.5% at this diverse, tropical, marine system.

Keywords: coral reef, environmental DNA, intertidal, Line Islands, Palmyra Atoll, species richness

1 |. INTRODUCTION

A camera-trap photo shows the precise time and place mountain lion P22 walked past the Hollywood sign (Riley et al., 2014). Contrary to this precision, white shark environmental DNA (eDNA) in a water sample only hints vaguely at a brush with danger (Lafferty et al., 2018). For this reason, a primary challenge for using eDNA for species detection compared to other sampling methods is quantifying inference across space and time (Goldberg et al., 2016). This challenge is even harder when extracting multi-species information from eDNA. Therefore, using eDNA as a community indicator requires defining the spatial scale at which the eDNA signal and resident species correlate. This scale varies with eDNA transport, retention and resuspension in freshwater systems (Deiner & Altermatt, 2014; Jane et al., 2015; Shogren et al., 2017). In addition to processes that occur in fresh water, oceans can have continental-scale currents and dynamic tides, potentially spreading eDNA over much larger distances than freshwater systems. This problem likely compounds as species richness increases. To better understand the scale that a marine eDNA sample represents, the extent to which tides and habitat affected the eDNA signal from marine fishes was investigated at a remote Pacific coral atoll.

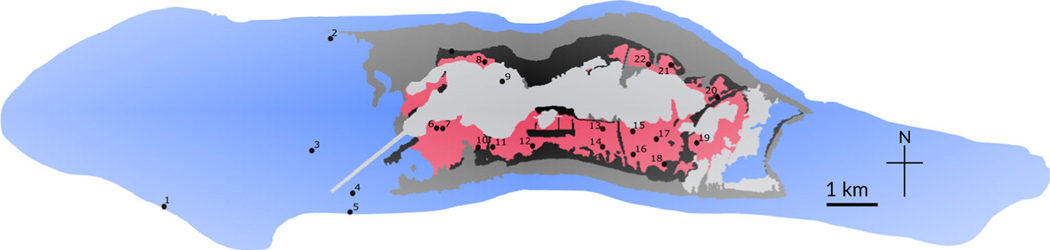

Palmyra Atoll is one of the few places where scientists can study an intact, unfished coral-reef ecosystem. This U.S. National Fish and Wildlife Refuge is 1600 km south of Hawai’i and has never supported permanent human habitation or the commercial or subsistence fisheries associated with it. Compared to inhabited atolls in the Northern Line Islands chain, marine systems in Palmyra Atoll support high apex-predator biomass (DeMartini et al., 2008; Sandin et al., 2008). The remarkable marine life at Palmyra Atoll lives in four primary marine habitats: submerged reef, intertidal reef (back reef), intertidal sand flats and deep-water lagoon (Figure 1). These habitats have different fish communities, though several fishes are habitat generalists (DeMartini et al., 2008; McLaughlin, 2018). Most sand-flat fishes are cryptic and dull in comparison with the colourful coral-reef fishes, and thus receive little notice, apart from anglers seeking bonefish (Friedlander et al., 2007).

FIGURE 1.

Habitats at Palmyra Atoll in relation to this study’s sampling sites. Palmyra Atoll (5°53′1″N 162°4′42″W) is a 12 km2 Pacific coral atoll administered as an unorganized incorporated territory and managed as a U.S. National Fish and Wildlife Refuge. A field station is run by the Nature Conservancy. Research focused on the fish communities living in the intertidal sand-flat habitat (red shading, site numbers 6–8,10–22), with comparison to fishes living on submerged reef (blue shading, site numbers 1–5) and the western lagoon (light grey shading, site number 9). ( ) Submerged reef, (

) Submerged reef, ( ) intertidal sand flat, (

) intertidal sand flat, ( ) intertidal reef flat, (

) intertidal reef flat, ( ) lagoon, (

) lagoon, ( ) offshore, (

) offshore, ( ) land, (

) land, ( ) sample site

) sample site

Although postcard-pristine, the U.S. military re-shaped Palmyra Atoll during World War II by dredging a deep-water channel and modifying the islands, sand flats and lagoons (Collen et al., 2009). The new channel increased outward flow and lowered the lagoon’s level by 30 cm. The lagoon now often appears murky, with little remaining living coral, giant clams or algae (Collen et al., 2009). Long-term goals for the atoll include restoring the lagoon to benefit marine communities by removing man-made barriers that impede circulation and replacing Cocos plantations with native forest. Therefore, there have been many studies on community structure and habitat connectivity at Palmyra, including surveying fish diversity, abundance and biomass density on the intertidal sand flats (Friedlander et al., 2007; McCauley et al., 2012; McLaughlin, 2018; Papastamatiou et al., 2009). They sought to determine whether eDNA signals might be an efficient way to describe distinct sand-flat fish communities at Palmyra Atoll. If eDNA samples represent a consistent habitat signal at Palmyra Atoll, then eDNA sampling might be a cost-effective way to monitor changes associated with lagoon restoration.

Although one might expect eDNA to be well dispersed in the ocean due to dilution and dispersion by currents (Andruszkiewicz et al., 2019), eDNA from near-shore habitats often reflects nearby (<150 m) species’ biomass (Yamamoto et al., 2016) or community structure (Djurhuus et al., 2020; Jeunen et al., 2019), even on complex coral atolls (West et al., 2020). Using striped jack (Pseudocaranxdentex) in cages, Murakami et al. (2019) found that eDNA did not travel far (79% of positive detections within 30 m), nor did it persist long after removing fish (< 2 h). Limited dispersal and short persistence means a marine eDNA sample is influenced by organisms within 60–80 m (O’Donnell et al., 2017; Port et al., 2016), which is a nice compromise between scale and extent. As a result, eDNA samples taken from adjacent bay, inner bay, main channel and outer bay have different species compositions (Jo et al., 2019), as do samples taken from surface, mid-depth and benthos (Jeunen et al., 2019; Lacoursière-Roussel et al., 2018; Yamamoto et al., 2016), or outer lagoon, surge channel and inner lagoon (West et al., 2020). Rapid eDNA degradation in near-shore waters (Collins et al., 2018), presumably due to pH, salinity and UV exposure (but see Andruszkiewicz et al., 2017), might help explain why the Cytochrome c oxidase I (COI) mtDNA signal from planktonic and benthic taxa does not seem to travel far, or be affected by tides in Hood Canal Washington (Kelly et al., 2018). If tides also do not affect the eDNA habitat signal at Palmyra Atoll, that would improve its use as a tool for assessing coral-reef fish communities here and elsewhere.

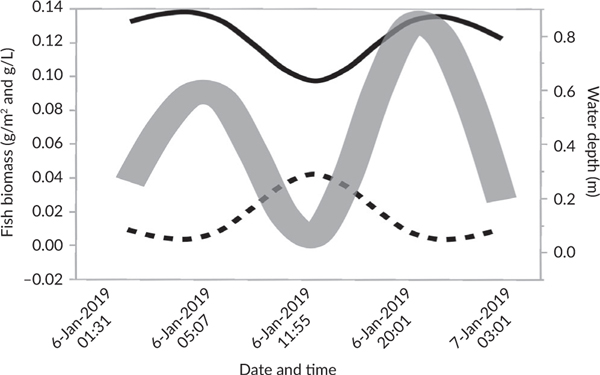

In 2017, Kelly et al.’s (2018) finding that tides had a limited effect on eDNA had not been published. Therefore, there was little insight from the literature into how tides might affect the eDNA signal on Palmyra Atoll’s intertidal sand flats. A tidal cycle on the sand flat begins with foraging shorebirds fleeing as the incoming (flood) tide brings water (and presumably eDNA) across exposed soft-sediment. This water, which had likely originated from lagoon and submerged reef habitats, floods the intertidal sand-flat habitats for a few hours, then drains back into the lagoon, before spilling out over the reef. The tidal cycle can change the biomass of fish on the flat as well as bioimass of fish per litre (Figure 2). Fish biomass per area (g m–2, solid line) declines at low tide when larger fish leave the flats. On the contrary, fish biomass per volume (g l–1, dotted line) has the opposite trend, because the remaining fishes are left in little water, making it difficult to predict how eDNA amplified from a water sample might increase or decrease with the tide. Tidal dynamics could affect eDNA composition in other ways. For example, given that most water on the sand flat originates from submerged reefs, higher eDNA concentrations from reef species on incoming tides and more eDNA from sand-flat species on outgoing tides might be predicted. In addition, some sites experience more cross-habitat water movement than others if they are near small channels between islets that have a short passage from the reef to the sand flat. Lastly, variation in temperature may affect eDNA degradation rates. Previous research at Palmyra Atoll indicates that the mean water temperature across the study sites is 31.2°C (McLaughlin, 2018). The lower an intertidal flat site’s elevation (e.g., sites that tended to be deep), the higher the average temperature and variation in temperature. After controlling for hour and depth, temperature also increases as the daytime incoming tide exposes lagoon water to heated substrate. Such heating might, therefore, increase eDNA degradation rates at incoming tides and at high water, compared to low or outgoing tides. These concerns and difficulties in predicting eDNA responses to cross-habitat tidal dynamics motivated the questions addressed here. First, is it possible to detect known differences in fish communities across habitats using eDNA? Second, do eDNA species richness and the eDNA habitat signal change with tide, depth and water age?

FIGURE 2.

Tide affects fish density. In this conceptual figure based on real data, the thick grey line shows how a typical June tidal cycle affects water depth on the flats. The thin black solid line shows how an influx of fishes at high tide increases the fish biomass density per area on the flats. Nonetheless, the dashed black line shows how the reduced water volume at low tide increases the fish biomass density per volume. It was assumed that environmental DNA concentrations would be more influenced by the volume fish density (g l–1) vs. area fish density (g m–2). (----) Biomass (g l–1), (—) biomass (g m–2), ( ) water depth (m)

) water depth (m)

2 |. METHODS

In August 2017, water samples were taken from 22 sites (Figure 1; Supporting Information Table SS1) by filling sterile Nalgene jars with surface water while wearing nitrile-free gloves. Depth and tide direction were noted for the intertidal sites (though, regrettably, temperature was not recorded). Five sites on submerged reef (2 on the fore reef, and 3 on the inner reef, 1 sample at each reef site corresponding to 2 pooled 250-ml samples taken within 10 m), 1 site in the deep-water lagoon (which is ignored here) and 16 intertidal sand-flat sites (1 sample of 250-ml per site, because higher turbidity limited the volume that could be passed through a filter) were sampled. Unfortunately, the difference in sample volumes taken from the two habitats means that when comparing reef sites to sand-flat sites, the relative proportion (rather than total counts) of fish species per sample associated with reef habitat or sand-flat habitat had to be analysed. All 16 sand-flat sites on outgoing tides and 7 of these sites again on incoming tides were sampled. The 29 samples put on ice were transported to the Palmyra Atoll lab, where they were filtered within 2 h. Because of the remote location and lack of vacuum pumps, the samples were pushed through a 0.22-um Sterivex™ filter unit (as recommended by Spens et al., 2017 and validated as equivalent to glass filters by Takahashi et al., 2020), using a sterile 50-ml syringe. All filters were preserved using Longmire’s solution (Longmire et al., 1997; Renshaw et al., 2015) and kept refrigerated until extraction in February 2019 (the authors did not collect fish, perform surgical procedures, stress fish in experiments, cause lasting harm to sentient fishes or involve sentient un-anaesthetised animals).

DNA extractions and PCR preparations were performed in a pre-PCR room, separate from all areas where post-PCR products are used. For each filter, DNA was extracted separately from both the individual filter capsules and the Longmire’s preservation solution within the capsules, resulting in 58 samples (e.g., two extractions for each of the 29 samples). After lysis buffer (720 μl buffer ATL for capsule and 180 μl for the solution extraction; Qiagen Inc., Hilden Germany) and proteinase K (80 μl and 20 μl, respectively) was added, the samples were incubated at 56°C for 24 h on a rotating incubator. A modified DNeasy™ Blood & Tissue protocol (following Spens et al., 2017) was used to extract the eDNA before amplification. Each set of 29 extractions had its corresponding extraction blank: a new Sterivex™ filter capsule with 720 μl buffer ATL and 80 μl proteinase K was used for the filter set, and a sterile microcentrifuge tube with 180 μl of ATL and 20 μl of Proteinase K was used for the Longmire’s solution set.

DNA was PCR amplified using the following primer sets with an Illumina Nextera™ adaptor modification: MiFish 12S Universal and MiFish 12S Elasmobranch (Miya et al., 2015), 18S (V8-V9; Bradley et al., 2016) and CO1 (mlCOIintF and jgHCO2198; Leray et al., 2013). PCR amplification was carried out in triplicate using a 15- μl reaction volume containing 3 μl of extract, 7.5 μl of QIAGEN Multiplex Taq PCR 2x Master Mix, 4.20 μl of dH2O and 0.15 μl of each primer (10 μmol l–1). Each set of 29 extractions had its corresponding PCR blank. For these, dH2O was used instead of DNA extract. Although CO1, 18S, MiFish 12S Universal and MiFish 12S Elasmobranch were sequenced, only the 12S data were analysed here, because these barcodes had the best coverage for fishes (CO1 detected 48 species, and 18S detected 3); nevertheless, the other barcodes give insight into different taxa at Palmyra Atoll.

Thermocycler settings for 12S reactions included an initial denaturation at 95°C for 15 min, followed by 13 touchdown cycles of (a) 94°C for 30 s; (b) annealing beginning 69.5°C for 45 s, decreasing by 1.5°C until 50°C was reached; and (c) extension at 72°C for 45 s. Subsequently, 35 additional cycles were run with a 50°C annealing temperature, followed by a 10-min final extension at 72°C. PCR replicates were pooled after verifying successful amplification. Then the PCR products were cleaned using Serapure magnetic beads (Faircloth & Glenn, 2014) to remove <100 bp fragments. Cleaned samples were quantified using the Qubit dsDNA BR Assay (Thermofisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Even numbers of molecules were pooled from each primer set for indexing. Dual i7 and i5 Illumina Nextera indices (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) were incorporated by amplification using Kapa HiFi HotStart ReadyMix (Kapa Biosystems, Wilmington, MA, USA) in 25-μl reactions of 12.5-μl mix, 0.625 μl of each index and sample volumes amounting to 10 ng of DNA for each sample. The thermocycler setting began with a 95°C incubation for 5 min, followed by 12 cycles of 98°C for 20 s, 56°C for 30 s and 72°C for 3 min, and ended with a 72°C incubation for 5 min. Indexed PCR products were again bead-cleaned and quantified. DNA libraries were pooled evenly and submitted for sequencing to the Technology Center for Genomics & Bioinformatics (TCGB) at the University of California, Los Angeles, where they were run on an Illumina MiSeq™ with Reagent Kit V3 (2 × 300 bp) at a goal depth of 40,000 reads in each direction per marker per sample.

Demultiplexed library Fastq files were processed with the Anacapa toolkit version 1 (github.com/limey-bean/Anacapa; Curd et al., 2019) using default parameters. Quality control of raw sequences and inference of Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs) was done using DADA2 (Callahan et al., 2016). Reference databases for 12S were generated in October 2019 with the Creating Reference libraries Using eXisting tools (CRUX) step of the Anacapa Toolkit (Curd et al., 2019). Taxonomy was assigned with CRUX databases, using Bowtie2 and the Bayesian Lowest Common Ancestor algorithm (BLCA; Gao et al., 2017), with a 70% bootstrap confidence. ASVs with identical taxonomy paths were merged.

Result tables were cleaned up by removing ASVs that had only one read across all samples. Sequences were decontaminated following the method proposed by Ramon Gallego and Ryan Kelly (unpubl. data). Then, sequences that experienced index hopping were removed. Poorly sequenced samples, if any, that fell below the 95% modelled normal distribution of total sequences were removed. Finally, ASVs that occurred more frequently in negative controls than in environmental samples were removed. After doing this decontamination step, reads from a filter’s solution and capsule were combined (i.e., one ASV list for each of the 29 filters after combining results processed separately for Longmire’s preservation solution and the filter capsule).

There were 321 bony fish “species” across all primer sets: 18S identified 3, CO1 identified 48 (but no sand-flat species that were not also identified by 12S), MiFish 12S Universal identified 254 species and MiFish 12S Elasmobranch identified 267 (Supporting Information Table S2). A comparison of results for the two 12S barcodes (MiFish 12S Universal and MiFish 12S Elasmobranch) indicated that results from any given site were similar for the two primers, but that each one contributed unique information (usually for rare species); therefore, the results were averaged to increase sample coverage (see Supporting Information Table S2 for the unpooled data).

From the validated data set (Supporting Information Table S3), reads for bony fishes that were identified to the species level and some reads at the genus level were retained as described later. Species represented only by a single copy across all 29 samples were excluded. It was further assumed that reads that were not central-Pacific marine fishes were from degraded eDNA or from errors in sequencing or reference library. Then reads were converted to detection or non-detection at the site level for analysis. Species-level matches for 21 out of the 39 known sand-flat species observed in the survey database were retained (McLaughlin, 2018). To expand matches between the known species and the eDNA database, the inclusion criteria were expanded to include six cases where assignment to a Genus sp. was unambiguous (e.g., there were no other common members of that genus in the study’s samples and the Genus sp. in GenBank®) and four cases where there was taxonomic revision that suggested synonymies between the study data and GenBank®. Only one sand-flat fish species (Psilogobius prolatus) was not reported in GenBank® at the species level. Nonetheless, eight species from the visual surveys could not be matched to eDNA under these criteria (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Flats species for which biomass density information was available (McLaughlin et al., 2018), including cases where Genusonly reads (*) or combined reads across environmental DNA–assigned taxa were included (**)

| Common flats species | Best eDNA Match |

|---|---|

| Abudefduf septemfasciatus | Abudefduf septemfasciatus |

| Abudefduf sordidus | Abudefduf sordidus |

| Acanthurus triostegus | Acanthurus triostegus |

| Acanthurus xanthopterus | Acanthurus xanthopterus |

| Albula glossodonta* | Albula |

| Amblygobius phalaena | Amblygobius phalaena |

| Arothron hispidus | Arothron hispidus |

| Asterropteryx semipunctata | Asterropteryx semipunctata |

| Bothus mancus | Bothus mancus |

| Carangoides ferdau | Carangoides ferdau |

| Carangoides orthogrammus* | Carangoides |

| Caranx ignobilis | Caranx ignobilis |

| Caranx melampygus* | Caranx |

| Caranx papuensis | NA |

| Chaetodon auriga | Chaetodon auriga |

| Chaetodon lunula* | Chaetodon |

| Chanos chanos | Chanos chanos |

| Crenimugil crenilabis** | Crenimugil crenilabis, Moolgarda seheli |

| Encheliophis gracilis | NA |

| Gymnothorax pictus | Gymnothorax pictus |

| Hemiramphus depauperatus* | Hemiramphus |

| Istigobius decoratus | NA |

| Istigobius ornatus | Istigobius ornatus |

| Liza vaigiensis** | Ellochelon vaigiensis |

| Lutjanus fulvus | Lutjanus fulvus |

| Lutjanus monostigma | Lutjanus monostigma |

| Mulloidichthys flavolineatus | Mulloidichthys flavolineatus |

| Myrichthys colubrinus** | Neenchelys buitendijki |

| Negaprion acutidens | NA |

| Oplopomus oplopomus | Oplopomus oplopomus |

| Parapercis sp.1 | NA |

| Pomacentrus adelus* | Pomacentrus |

| Pseudobalistes flavimarginatus | NA |

| Psilogobius prolatus | NA |

| Rhinecanthus aculeatus | Rhinecanthus aculeatus |

| Sphyraena barracuda* | Sphyraena |

| Upeneus taeniopterus | NA |

| Valamugil engeli** | Moolgarda pedaraki, Valamugil robustus |

| Valenciennea sexguttata | Valenciennea sexguttata |

Note. NA indicates no clear eDNA match to species in the visual survey.

To evaluate sample completeness, the species richness and the sample “coverage” were estimated. Species richness was estimated using the iChaoII estimator, which is a non-parametric approach of using the rarity of species occurring in the observed species richness to project an estimate that accounts for unobserved species in the sampling effort. Coverage values close to one have likely identified nearly all the species present, whereas values closer to zero indicate insufficient sampling with a greater potential for unidentified species being detected with additional sampling effort. An overview of iChaoII species richness and coverage estimators can be found in the supporting papers for the SpadeR (Chao et al., 2016) and iNext (Hsieh et al., 2016) R packages used in the study’s analysis.

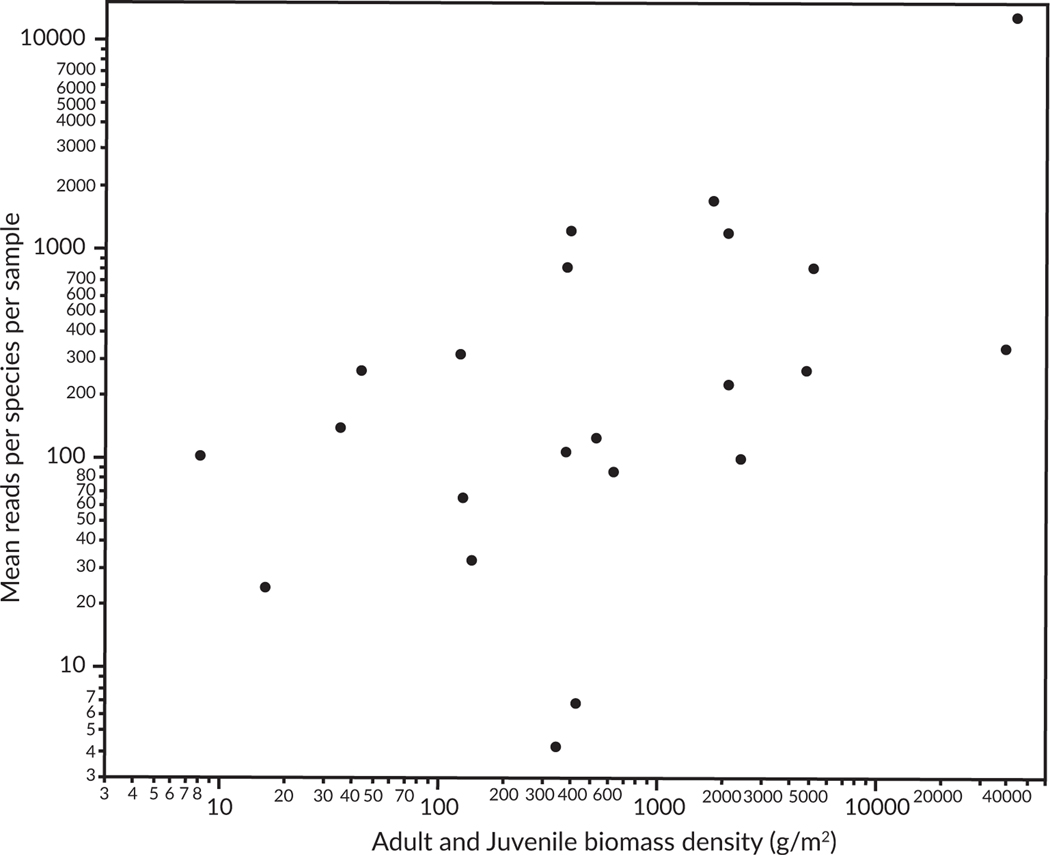

The eDNA response to fish abundance at the system level was further validated by plotting mean reads per species (mean reads from MiFish 12S Universal and MiFish 12S Elasmobranch across all sand-flat sites for 22 species for which both eDNA and biomass information was available) against species count density and biomass density estimates for fish from McLaughlin (2018) (Supporting Information Table S4). The fish abundance and length estimates were collected in August–September 2009. Then, gobies were surveyed by snorkel transect at 35 focal sites. Non-gobioid fish were surveyed at an additional 36 sites (71 total) along walking transects. Estimates for individual fish species were calibrated for water depth across 1 year of tidal cycles at each of 35 focal sites (see McLaughlin, 2018 for detailed methods). Counts were converted to biomass using length–weight regressions. eDNA samples and abundance estimates were not collected simultaneously, so site-level comparisons were not made. Instead, the pooled relative abundance of a species was used as the unit of replication, as this larger-scale sample seemed more likely to be consistent across years.

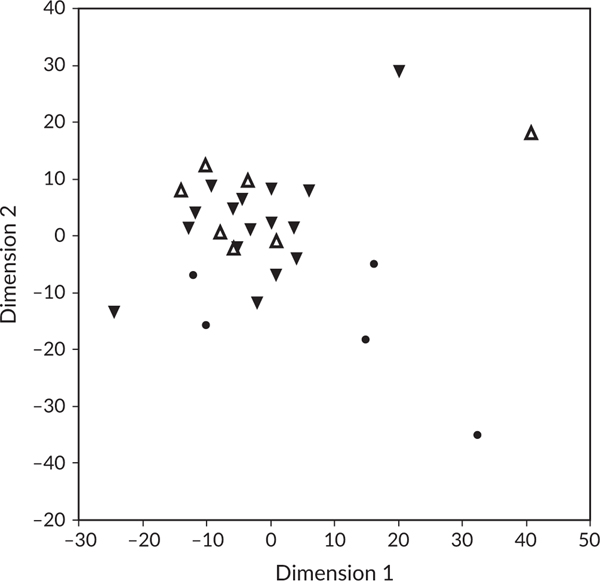

As a first pass at detecting a habitat signal and tide effect, communities inferred by eDNA analysis on water samples were plotted in two-dimensional space using multidimensional scaling (JMP®, Version Pro 14.1. SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA, 1989–2019, with ordinal transformation), and marking points by habitat and tide direction. A Shepard diagram indicated that ordinal transformation met test assumptions (stress = 0.18, R-square = 0.90). Whether habitat or tidal direction affected the community ordination was also analysed.

To establish the extent to which a sample contained eDNA from reef vs. sand-flat fishes, each species detected by eDNA was assigned to a previously determined designation based on online descriptions (Froese, R. & D. Pauly. Editors. 2019. FishBase. World Wide Web electronic publication. www.fishbase.org) supplemented with field observations at Palmyra: sand-flat associated (sand flat only, mostly sand flat, sand flat and lagoon), reef-associated (reef and lagoon, mostly reef and reef only) and general (sand flat and reef, non-specific, pelagic, bathypelagic). Then the relative frequency of detected species in each category across the sampled habitats was compared. If eDNA in a sample represented the resident fish community, it was predicted that a sand-flat sample would have relatively more reads from sand-flat-associated fishes and fewer from reef-associated fishes than a reef sample. Finally, the same response variables at the incoming and outgoing tides were compared to see if the community signal changed with tidal direction.

Linear mixed models were used to assess effects of tides and habitat on species detections in eDNA samples. Data on depths, tides and temperatures were taken from McLaughlin (2018). Data on water retention at a site were taken from Rogers et al. (2017) using ImageJ (U. S. National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA, https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/, 1997–2018) to reverse-engineer their Figure 11c. In statistical models of this study (run using JMP Pro 14.1), species detection or non-detection within a sample, or the habitat affiliations of species detected in a sample, was the dependent variable. When comparing individual species among flats, site was treated as a random effect to allow paired comparisons. When comparing habitat affiliations between reef and sand-flat sites, site was not considered a random effect because the data were proportionalized within a site to account for the aforementioned unequal sampling volumes between sand-flat and reef sites. All first-order interactions were entered into a model. A model was then simplified using BIC to reduce over-fitting (Dennis et al., 2019).

3 |. RESULTS

The 58 samples, along with the two extraction blanks and two PCR blanks, resulted in 9,024,841 reads across the four metabarcoding loci. After quality control implementation in the Anacapa Toolkit (Curd et al., 2019), taxonomic assignment to National Center for Biotechnology Information–based reference databases with the Anacapa tool CRUX, sequence decontamination and merging of results from capsule and Longmire’s solution, 3,989,287 reads from 3906 distinct ASVs were retained from the four metabarcodes used here, with a mean assigned read depth of 34,390 per metabarcode per sample and mean of 536 taxa identified per sample. Nonetheless, for the results, ASVs from the 12S Mifish_U and Mfish_E primers are reported here, as these had the best coverage for fish taxa.

The eDNA signal from all four primers included >2500 species, including many invertebrate, shark/ray, bird and mammal taxa. For instance, samples contained reads from Manta birostris, which are common on the reefs and in the lagoon; Aetobatus narinari and Charcharhinus melanopterus, which are common on reefs and flats; and Charcharhinus sp., which may refer to C. melanopterus or C. amblyrhynchos, the latter of which is common on the reefs and in the lagoon. Nonetheless, the focus is on bony fishes, because they are often well resolved, and many were specific to sand flats. In the 29 combined samples, eDNA was found to be assigned to 164 bony fish taxa validated for habitat and geography at the species level. This included 127 species from the limited reef samples, for which, on average, a 500-ml reef sample had 49.4 (±8.8 95% C.L.) species. On the contrary, eDNA was assigned to 156 species in several sand-flat samples. On average, a 250-ml sand-flat sample had eDNA assigned to 39.4 (±3.3 95% C.L.) species. Nonetheless, most (∼80%) of the validated fish eDNA detected at the sand-flat sites was from reef species, indicating substantial spillover (see Discussion). The raw data files are so large that a link was posted to a public repository (https://data.ucedna.com/research_projects/palmyra-atoll/pages/overview).

With five samples (total volume 2.5 l), and a sample coverage of 0.83, the limited reef eDNA sampling likely did not detect 56 (rare) species (Table 2). The probability of detecting a new species with one more sample was estimated as 0.17 and may be as high as 0.22. In contrast, eDNA detected 31 of the 39 previously observed sand-flat species, particularly when high tide and low tide were combined. In this case, there were potentially six undetected (rare) species, and the probability of detecting a new species with another sample collected was approximately 0.02. Nonetheless, when high tide and low tide were separated and compared, there was no evidence for a difference in species richness by tide.

TABLE 2.

Species richness inferences detectable by environmental DNA

| Location | n | S(obs) | S(Est) iChao II | S(est) 95% C.I. | Coverage | Coverage 95% C.I. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reef | 5 | 127 | 169.7 | (159.4, 183.2) | 0.83 | (0.78, 0.89) |

| Flats (low tide) | 16 | 151 | 167.2 | (161.5, 176.1) | 0.96 | (0.95, 0.97) |

| Flats (high tide) | 7 | 121 | 143.5 | (133.5, 171.2) | 0.90 | (0.86, 0.93) |

| Flats (combined) | 23 | 156 | 165.5 | (161.8, 171.3) | 0.98 | (0.98, 1) |

Note. Observed (S(obs)) and estimated (S(est)) species richness given the sampling effort for this study, by habitat. Coverage is a measure of how well a sample represents the species that are present and detectable in the system.

Although there was no relationship between the average sand-flat fish count density and copy read density (log-transformed variables, P = 0.70, r = 0.08, df = 21), the average sand-flat fish biomass density from McLaughlin (2018) was positively correlated with the average total reads per sand-flat species (log-transformed variables, P = 0.015, r = 0.51, df = 21) at sand-flat sites (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Increased reads per sample in association with the average biomass density of a species (adults and juveniles combined) per site in grams per square m. Each point represents one of 22 species for which information was available for both environmental DNA (eDNA) and biomass. Biomass data (horizontal axis) are averages from the entire sand-flat habitat taken from McLaughlin (2018). The vertical axis is the combined eDNA signal (mean reads from MiFish 12S Universal and MiFish 12S Elasmobranch across all flats sites in this study). The two variables were positively correlated (r = 0.51)

The multidimensional scaling analysis showed how eDNA samples from sand-flat habitat formed a cluster that was distinct from eDNA samples taken from the reef. Reef sites were less grouped (due to a split between fore reef sites to the left, and inner reef sites to the right) and were separated from sand-flat sites in the vertical dimension (Figure 4; T = 4.14, df = 26,1, P = 0.0003). On the contrary, eDNA samples from the sand flats did not cluster by tidal direction (Figure 4; T = 0.98, df = 21,1, P = 0.34).

FIGURE 4.

Multidimensional scaling plot (with ordinal transformation) separates flats from reef sites. Each symbol is a sample. Circles indicate reef sites (the left two are fore reef, and the right three are inner reef), and triangles indicate flats sites. Upward triangles are incoming tides, and downward triangles are outgoing tides. Reef and flats sites formed separate clusters, whereas incoming and outgoing tides did not

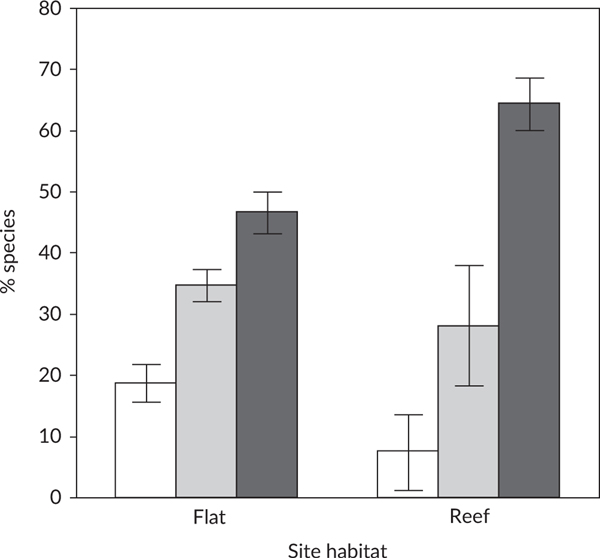

The habitat signal was reduced by spillover across habitats. At the community level, reef species dominated the relative diversity in eDNA samples at both habitats (Table 3; Figure 5), most likely due to the high reef fish richness, combined with eDNA spilling over from the reef to the sand-flat habitat. Nonetheless, a significant interaction term between habitat at the collection site and the habitat affinities of fish species detected by eDNA (P < 0.0001) indicated a habitat signal in the eDNA. Although species not associated with a particular habitat (general species) had similar relative detections of eDNA at reef sites (28% ± 6% 95% C.L.) and sand-flat sites (35% ± 3% 95% C.L.), species associated with reef habitat contributed a relatively higher proportion of the eDNA detected at reef sites (64% ± 6% 95% C.L.) than detected at sand-flat sites (47% ± 3% 95% C.L.), and species associated with sand-flat habitat contributed more eDNA at sand-flat sites (18% ± 3% 95% C.L.) than at reef sites (7.5% ± 6% 95% C.L.). Next, the extent this habitat signal changed with the tide and water age is assessed.

TABLE 3.

Proportion of species detected by environmental DNA at a site according to the habitat at the sampling site (SiteHabitat), the habitat that a fish species tends to be from (Broad_Fish_Habitat) and their interaction

| Term | Estimate | Standard error | t ratio | Prob>|t| |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 0.3333333 | 0.009781 | 34.08 | <0.0001* |

| SiteHabitat(Flat) | −2.41e-18 | 0.009781 | −0.00 | 1.0000 |

| Broad_Fish_Habitat(Flats) | −0.202206 | 0.013832 | −14.62 | <0.0001* |

| Broad_Fish_Habitat(General) | −0.019349 | 0.013832 | −1.40 | 0.1658 |

| SiteHabitat(Flat)*Broad_Fish_Habitat(Flats) | 0.0561458 | 0.013832 | 4.06 | 0.0001* |

| SiteHabitat(Flat)*Broad_Fish_Habitat(General) | 0.0326184 | 0.013832 | 2.36 | 0.0209* |

Note. Model selected by BIC included the interaction term. R-square = 0.82.

FIGURE 5.

At the community level, environmental DNA (eDNA) from reef fishes dominated all sites, but was relatively more common at reef sites than at sand-flat sites (means ± 95% confidence limits), whereas eDNA from flats fishes was relatively more common at sand-flat sites than at reef sites. Each site habitat sums to 100%. Note that data were pooled for flats sites with incoming and outgoing tides because tide did not affect eDNA from flats sites. ( ) Flat, (

) Flat, ( ) general, (

) general, ( ) reef

) reef

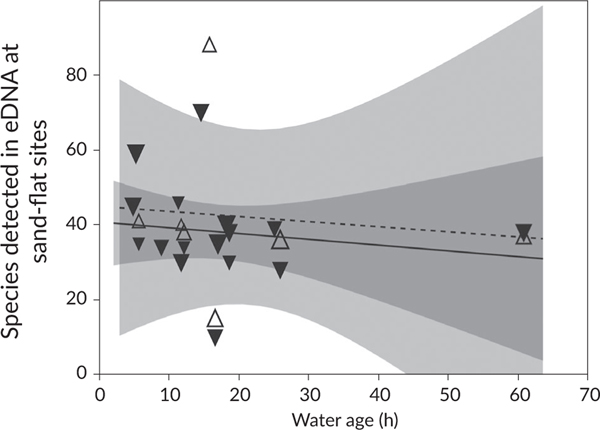

At sand-flat sites, the species richness in the eDNA signal was not associated with depth or water age, as main effects or in interactions (Table 4; Figure 6). Although more eDNA from more species was detected on the incoming tide (44 ± 9 species) compared with the outgoing tide (37.6 ± 9 species), this was not statistically significant (P = 0.06). Most variation among samples was therefore associated with the site (and measurement error).

TABLE 4.

Least-squares regression for species counts in response to tide, depth and water age

| Source | Nparm | DF | DFDen | F ratio | Prob > F |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tide | 1 | 1 | 3.531 | 7.3151 | 0.0616 |

| Water age (h) | 1 | 1 | 14.38 | 0.5090 | 0.4870 |

| Water depth | 1 | 1 | 4.531 | 0.0632 | 0.8125 |

| Tide*depth | 1 | 1 | 4.496 | 0.3324 | 0.5919 |

| Age*depth | 1 | 1 | 4.237 | 0.6992 | 0.4476 |

Note. Site was used as a random effect to allow within-site comparisons. Model selected by BIC excluded the age*tide interaction term. R-square = 0.99.

FIGURE 6.

Number of environmental DNA (eDNA) detected species vs. tide, depth and water age at sand-flat sites. The number of species detected with eDNA at flats is plotted against the age of the water mass in hours on the horizontal axis (the wide shaded areas represent 95% C.I., indicating no trend with water age, and no difference between the incoming and outgoing tides). The size of points represents relative water depth, and the markers separate incoming (upward open triangles and dashed line) and outgoing (downward closed triangles and solid line) tides (neither variable affected species richness detected at a site). (Δ) Incoming, (▾) outgoing, (----) incoming, (—) outgoing

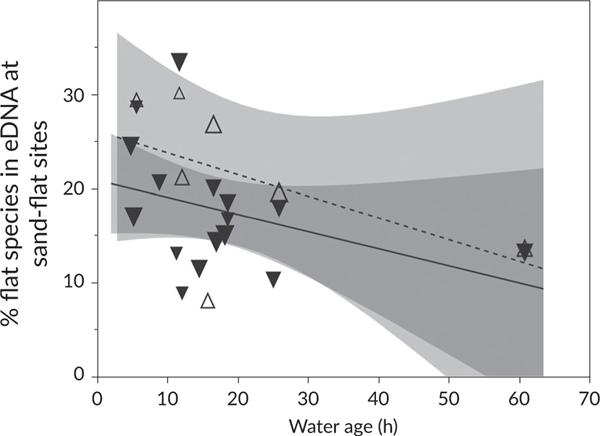

At sand-flat sites, the percentage of sand-flat species in the eDNA signal was not associated with tide or depth, as main effects or in interactions (Table 5; Figure 7). Although eDNA from more sand-flat species was (unexpectedly) found at sites with more water exchange, water mass age was not a significant effect (P = 0.09). Most variation among samples in the habitat signal was therefore associated with the site (and measurement error).

TABLE 5.

Least-squares regression for % flats species (the habitat signal) in response to tide, depth and water age

| Term | Estimate | Standard error | DFDen | t ratio | Prob > |t| |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 16.781243 | 5.558241 | 13.46 | 3.02 | 0.0095* |

| Tide | 1.4995592 | 1.011417 | 4.923 | 1.48 | 0.1992 |

| Water age (h) | −0.245522 | 0.135264 | 14.06 | −1.82 | 0.0909 |

| Depth | 14.345908 | 12.25543 | 7.876 | 1.17 | 0.2760 |

| Tide*depth | −1.328654 | 10.03852 | 7.695 | −0.13 | 0.8981 |

| Age*depth | 0.7711 | 1.554141 | 8.656 | 0.50 | 0.6321 |

Note. Site was used as a random effect to allow within-site comparisons. Model selected by BIC excluded the age*tide interaction term. R-square = 0.91.

FIGURE 7.

Habitat signal vs. tide, depth and water age. The percentage of flats species detected in environmental DNA at the flats is plotted against the age of the water mass in hours on the horizontal axis (the wide shaded areas represent 95% C.I., indicating no significant trend with water age, and no difference between the incoming and outgoing tides). The size of points represents relative water depth, and the markers separate incoming (upward open triangles and dashed line) and outgoing (downward closed triangles and solid line) tides (neither variable affected species richness detected at a site). (Δ) Incoming, (▾) outgoing, (----) incoming, (—) outgoing

4 |. DISCUSSION

eDNA was detected from roughly 80% of the sand-flat fishes known to be present at Palmyra Atoll. Most eDNA reads were identified to the species level, though eDNA was not detected at the species level from eight common species on sand flats (McLaughlin, 2018). Nonetheless, seven of these were associated with genus-level detections.

Coral atolls have more biodiversity than the temperate freshwater systems where early metabarcoding eDNA approaches were applied. For example, Olds et al. (2016) inferred the presence of 16 species from eight eDNA screened water samples and had a 0.99 (95% CI: 0.97, 1) sample coverage for a small, warm water stream in Indiana, USA. But as eDNA metagenetic studies are applied to more diverse systems (Cowart et al., 2018; Garlapati et al., 2019; Hayes et al., 2017; Jerde et al., 2019; Streit & Schmitz, 2004; Titcomb et al., 2019), it has become clear that the approximate sample sizes needed to estimate species richness can be higher. Coverage was likely improved for this study because it had four measures per sample (filter and filtrate X MiFish 12S Universal and MiFish 12S Elasmobranch). Still, the eDNA from 127 species detected in the five reef samples barely approached the 395 cumulative fish species documented at Palmyra Atoll (Mundy et al., 2010). This is in part because eDNA sampling of this study is a snapshot in time. In addition, a higher water volume sampled per site would have detected more rare species and improved site-level accuracy (Bessey et al., 2020). Regardless, even 242 water samples detected only 244 out of 602 cumulatively reported bony fish and elasmobranch species at the Cocos (Keeling) Islands (West et al., 2020), indicating that eDNA sampling, as for any sampling method, will likely miss rare species even with considerable effort, especially compared with cumulative species lists.

The habitat signal suggests that eDNA contains some site-level information about fish communities, as has been alleged in other marine eDNA studies (Jeunen et al., 2019; Murakami et al., 2019; Stat et al., 2017; West et al., 2020). Nonetheless, the sand-flat signal was diluted by eDNA from species living in adjacent habitats. Specifically, the 156 species detected in the eDNA sand-flat samples exceed the 41 fish species (including gobies) tabulated from extensive sand-flat surveys, suggesting most of the eDNA diversity at sand-flat sites originated from nearby reef or lagoon habitats (though it is certainly possible that eDNA detections represent species not easily detectable by conventional methods). More likely, this occurred because the reef has more fish species, and reefs are in close proximity to sand flats (McCauley et al., 2012; McLaughlin, 2018; Papastamatiou et al., 2010; Williams et al., 2011). Also, water spends more time on the reef (mean 20 h) (Rogers et al., 2017) than it does on the sand flat (∼12 h highlow cycle), giving it more time to accumulate and concentrate eDNA from reef fish before spilling onto the sand flat at high tide. Other reads were from pelagic or bathypelagic fishes living well outside the system, perhaps transported as larvae (West et al., 2020) or in excrement from foraging seabirds. Therefore, habitat-specific analyses using eDNA would need to account for fish movement among habitats or eDNA spillover from one habitat to the other. Using eDNA alone would have overestimated site-level fish diversity.

The association between copy reads per species and the biomass density per species indicates that eDNA was more likely to detect abundant taxa. Although variation in amplification among eDNA sequences (assay sensitivity) can reduce such correlations (Fonseca, 2018), strong associations between fish density and read density are noted in mesocosms (Evans et al., 2016), and some field studies (Evans et al., 2017; Handley et al., 2019). Some unexplained variation in field samples is expected due to eDNA transport (Andruszkiewicz et al., 2019), and higher sampling error (abundance estimates of this study were collected years before the eDNA measurements), and potentially due to wider ranges in body sizes among fish individuals. The latter reason might explain why read abundance increased with species biomass density but not species count density at Palmyra Atoll, and it would not surprise us if past failures to find an association between read abundance and species abundance were due to using count density rather than biomass density. Although the correlation between fish biomass density and read abundance helps validate that eDNA detects common fishes more than rare fishes, the unexplained variance is too high to use read abundance to predict fish abundance in this system.

This study did not find evidence that tides, depth or water mass age (or their effects through temperature) affected the eDNA richness estimate or the habitat signal, consistent with Collins et al. (2018). Possible effects alluded to in the data include more species detected on the incoming tide and a stronger habitat signal at sites with stronger currents. Neither effect was predicted, and it seems unwise to provide a post hoc interpretation without more data. Particle tracking models applied to marine systems with diverse habitats and currents may illuminate the patterns of species detection better than discrimination by species composition (Andruszkiewicz et al., 2019). Although these results suggest that sampling programmes need not fret about the tidal cycle, how tides affect the eDNA signal on the fore reef was not investigated. As the lagoon drains, turbid and heated water spills out onto the fore reef and could carry a signal from within the lagoon-flats complex. Therefore, when sampling the fore reef, it is suggested that the outgoing tide be avoided if the goal is to measure the reef fish community.

Being little affected by tides, eDNA was useful for characterizing the fish communities on the intertidal sand flats and the broader food web in which they live, consistent with Kelly et al. (2018). eDNA was used to identify several fishes that were difficult to distinguish based on morphology, a clear advantage of the eDNA metabarcoding method (Jerde et al., 2019). Furthermore, although visual surveys are likely more efficient at characterizing the fish community at a particular site (West et al., 2020), eDNA detected fishes not often seen in visual surveys, helping to reconsider the composition of the fish community at this well-studied site. Although eDNA may have higher sensitivity than visual surveys, visual surveys have higher specificity, because they do not include species absent from a site. Both sensitivity and specificity are needed for accurate fish community assessments. The other barcodes in this effort reveal information about mammals, birds, elasmobranchs, invertebrates, plants and bacteria, all of which might respond to lagoon restoration at Palmyra Atoll and would allow for whole-ecosystem biomonitoring (Stat et al., 2017; West et al., 2020). The results suggest that eDNA can be a useful tool for studying marine fish communities at other coral-reef ecosystems with important caveats about spillover across adjacent habitats.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The Nature Conservancy and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service provided support in the field. Assistance was also provided by the UCLA CALeDNA programme. Any use of trade, firm or product names in this publication is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. government.

Funding information

The president of the University of California Catalyst research grant programme (Award number: CA-16–376,437) and Howard Hughes Medical Institute (Award number: GT10483) contributed funding. A.E.G.V. is a postdoctoral fellow supported by UPLIFT: UCLA Postdocs’ Longitudinal Investment in Faculty (Award number: K12 GM106996). The Nature Conservancy contributed in-kind support. USGS EMA provided support to K.D.L.

Footnotes

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional supporting information may be found online in the Supporting Information section at the end of this article.

REFERENCES

- Andruszkiewicz EA, Koseff JR, Fringer OB, Ouellette NT, Lowe AB, Edwards CA, & Boehm AB. (2019). Modeling environmental DNA transport in the coastal ocean using Lagrangian particle tracking. Frontiers in Marine Science, 6, 477. [Google Scholar]

- Andruszkiewicz EA, Sassoubre LM, & Boehm AB. (2017). Persistence of marine fish environmental DNA and the influence of sunlight. PLoS One, 12(9), e0185043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bessey C, Jarman SN, Berry O, Olsen YS, Bunce M, Simpson T, … Keesing J. (2020). Maximizing fish detection with eDNA metabarcoding. Environmental DNA, 1–12. 10.1002/edn3.74. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley IM, Pinto AJ, & Guest JS. (2016). Design and evaluation of Illumina MiSeq-compatible, 18S rRNA gene-specific primers for improved characterization of mixed phototrophic communities. Applied Environmental Microbiology, 82(19), 5878–5891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callahan BJ, McMurdie PJ, Rosen MJ, Han AW, Johnson AJA, & Holmes SP. (2016). DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nature Methods, 13(7), 581–583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao A, Ma KH, Hsieh TC, & Chiu C. (2016). SpadeR: Species prediction and diversity estimation with R. R package version 0.1.1. [Google Scholar]

- Collen JD, Garton DW, & Gardner JPA. (2009). Shoreline changes and sediment redistribution at Palmyra Atoll (Equatorial Pacific Ocean): 1874-present. Journal of Coastal Research, 25(3), 711–722. [Google Scholar]

- Collins RA, Wangensteen OS, O’Gorman EJ, Mariani S, Sims DW, & Genner MJ. (2018). Persistence of environmental DNA in marine systems. Communications Biology, 1(1), 185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowart DA, Murphy KR, & Cheng CHC. (2018). Metagenomic sequencing of environmental DNA reveals marine faunal assemblages from the West Antarctic Peninsula. Marine Genomics, 37, 148–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curd EE, Gold Z, Kandlikar GS, Gomer J, Ogden M, O’Connell T, … Meyer RS. (2019). Anacapa toolkit: An environmental DNA toolkit for processing multilocus metabarcode datasets. Methods in Ecology and Evolution, 10(9), 1469–1475. [Google Scholar]

- Deiner K, & Altermatt F. (2014). Transport distance of invertebrate environmental DNA in a natural river. PLoS One, 9(2), e88786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeMartini EE, Friedlander AM, Sandin SA, & Sala E. (2008). Differences in fish-assemblage structure between fished and unfished atolls in the northern Line Islands, Central Pacific. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 365, 199–215. [Google Scholar]

- Dennis B, Ponciano JM, Taper ML, & Lele SR. (2019). Errors in statistical inference under model misspecification: Evidence, hypothesis testing, and AIC. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, 7, 372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djurhuus A, Closek CJ, Kelly RP, Pitz KJ, Michisaki RP, Starks HA, … Montes E. (2020). Environmental DNA reveals seasonal shifts and potential interactions in a marine community. Nature Communications, 11(1), 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans NT, Olds BP, Renshaw MA, Turner CR, Li Y, Jerde CL, … Lodge DM. (2016). Quantification of mesocosm fish and amphibian species diversity via environmental DNA metabarcoding. Molecular Ecology Resources, 16(1), 29–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans NT, Li Y, Renshaw MA, Olds BP, Deiner K, Turner CR, … Pfrender ME. (2017). Fish community assessment with eDNA metabarcoding: Effects of sampling design and bioinformatic filtering. Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences, 74(9), 1362–1374. [Google Scholar]

- Faircloth BC, & Glenn TC. (2014). Faircloth-lab serapure protocol. http://protocols-serapure.readthedocs.org/en/latest/

- Fonseca VG. (2018). Pitfalls in relative abundance estimation using eDNA metabarcoding. Molecular Ecology Resources, 18(5), 923–926. [Google Scholar]

- Friedlander A, Caselle J, Beets J, Lowe C, Bowen B, Ogawa T, … Anderson B. (2007). Aspects of the biology, ecology, and recreational fishery for bonefish at Palmyra Atoll National Wildlife Refuge, with comparisons to other Pacific Islands. Biology and management of the world’s tarpon and bonefish fisheries (pp. 28–56). Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. [Google Scholar]

- Froese R, & Pauly D. (Eds). 2019. FishBase. World Wide Web electronic publication. www.fishbase.org. [Google Scholar]

- Gao X, Lin H, Revanna K, & Dong Q. (2017). A Bayesian taxonomic classification method for 16S rRNA gene sequences with improved species-level accuracy. BMC Bioinformatics, 18(1), 247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garlapati D, Charankumar B, Ramu K, Madeswaran P, & Murthy MR. (2019). A review on the applications and recent advances in environmental DNA (eDNA) metagenomics. Reviews in Environmental Science and Bio/Technology, 18(3), 389–411. [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg CS, Turner CR, Deiner K, Klymus KE, Thomsen PF, Murphy MA, … Laramie MB. (2016). Critical considerations for the application of environmental DNA methods to detect aquatic species. Methods in Ecology and Evolution, 7(11), 1299–1307. [Google Scholar]

- Handley L, Read DS, Winfield IJ, Kimbell H, Johnson H, Li J, … Hänfling B. (2019). Temporal and spatial variation in distribution of fish environmental DNA in England’s largest lake. Environmental DNA, 1(1), 26–39. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes S, Mahony J, Nauta A, & Van Sinderen D. (2017). Metagenomic approaches to assess bacteriophages in various environmental niches. Viruses, 9(6), 127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh TC, Ma KH, & Chao A. (2016). iNEXT: An R package for rarefaction and extrapolation of species diversity (H ill numbers). Methods in Ecology and Evolution, 7(12), 1451–1456. [Google Scholar]

- Jane SF, Wilcox TM, McKelvey KS, Young MK, Schwartz MK, Lowe WH, … Whiteley AR. (2015). Distance, flow and PCR inhibition: e DNA dynamics in two headwater streams. Molecular Ecology Resources, 15(1), 216–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jerde CL, Wilson EA, & Dressler TL. (2019). Measuring global fish species richness with eDNA metabarcoding. Molecular Ecology Resources, 19(1), 19–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeunen GJ, Knapp M, Spencer HG, Lamare MD, Taylor HR, Stat M, … Gemmell NJ. (2019). Environmental DNA (eDNA) metabarcoding reveals strong discrimination among diverse marine habitats connected by water movement. Molecular Ecology Resources, 19(2), 426–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jo H, Kim DK, Park K, & Kwak IS. (2019). Discrimination of spatial distribution of aquatic organisms in a coastal ecosystem using eDNA. Applied Sciences, 9(17), 3450. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly RP, Gallego R, & Jacobs-Palmer E. (2018). The effect of tides on near shore environmental DNA. PeerJ, 6, e4521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacoursière-Roussel A, Howland K, Normandeau E, Grey EK, Archambault P, Deiner K, … Bernatchez L. (2018). eDNA metabarcoding as a new surveillance approach for coastal Arctic biodiversity. Ecology and Evolution, 8(16), 7763–7777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lafferty KD, Benesh KC, Mahon AR, Jerde CL, & Lowe CG. (2018). Detecting southern California’s white sharks with environmental DNA. Frontiers in Marine Science, 5, 355. [Google Scholar]

- Leray M, Yang JY, Meyer CP, Mills SC, Agudelo N, Ranwez V, … Machida RJ. (2013). A new versatile primer set targeting a short fragment of the mitochondrial COI region for metabarcoding metazoan diversity: Application for characterizing coral reef fish gut contents. Frontiers in Zoology, 10(1), 34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longmire JL, Maltbie M, & Baker RJ. (1997). Use of” lysis buffer” in DNA isolation and its implication for museum collections. Museum of Texas Tech University. Texas: Occasional papers / Museum of Texas Tech University, no. 163. 10.5962/bhl.title.143318. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McCauley DJ, Young HS, Dunbar RB, Estes JA, Semmens BX, & Micheli F. (2012). Assessing the effects of large mobile predators on ecosystem connectivity. Ecological Applications, 22(6), 1711–1717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin JP. (2018). The food web for the sand flats at Palmyra Atoll (Doctoral thesis), University of California; Santa Barbara, Santa Barbara, CA. [Google Scholar]

- Miya M, Sato Y, Fukunaga T, Sado T, Poulsen JY, Sato K, … Iwasaki W. (2015). MiFish, a set of universal PCR primers for metabarcoding environmental DNA from fishes: Detection of more than 230 subtropical marine species. Royal Society Open Science, 2(7), 150088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mundy BC, Wass ED, Greene B, Zgliczynski B, Schroeder RE, & Musberger C. (2010). Inshore fishes of Howland Island, Baker Island, Jarvis Island, Palmyra Atoll, and Kingman Reef. Atoll Research Bulletin, 585, 1–131. [Google Scholar]

- Murakami H, Yoon S, Kasai A, Minamoto T, Yamamoto S, Sakata MK, … Masuda R. (2019). Dispersion and degradation of environmental DNA from caged fish in a marine environment. Fisheries Science, 85(2), 327–337. [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell JL, Kelly RP, Shelton AO, Samhouri JF, Lowell NC, & Williams GD. (2017). Spatial distribution of environmental DNA in a near shore marine habitat. PeerJ, 5, e3044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olds BP, Jerde CL, Renshaw MA, Li Y, Evans NT, Turner CR, … Lamberti GA. (2016). Estimating species richness using environmental DNA. Ecology and Evolution, 6(12), 4214–4226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papastamatiou YP, Friedlander AM, Caselle JE, & Lowe CG. (2010). Long-term movement patterns and trophic ecology of blacktip reef sharks (Carcharhinus melanopterus) at Palmyra Atoll. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology, 386(1–2), 94–102. [Google Scholar]

- Papastamatiou YP, Lowe CG, Caselle JE, & Friedlander AM. (2009). Scale-dependent effects of habitat on movements and path structure of reef sharks at a predator-dominated atoll. Ecology, 90(4), 996–1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Port JA, O’Donnell JL, Romero-Maraccini OC, Leary PR, Litvin SY, Nickols KJ, … Kelly RP. (2016). Assessing vertebrate biodiversity in a kelp forest ecosystem using environmental DNA. Molecular Ecology, 25(2), 527–541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renshaw MA, Olds BP, Jerde CL, McVeigh MM, & Lodge DM. (2015). The room temperature preservation of filtered environmental DNA samples and assimilation into a phenol–chloroform–isoamyl alcohol DNA extraction. Molecular Ecology Resources, 15(1), 168–176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley SP, Serieys LE, Pollinger JP, et al. (2014). Individual behaviors dominate the dynamics of an urban mountain lion population isolated by roads. Curr Biol, 24(17), 1989–1994. 10.1016/j.cub.2014.07.029 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers JS, Monismith SG, Fringer OB, & Koweek DA. (2017). A coupled wave-hydrodynamic model of an atoll with high friction: Mechanisms for flow, connectivity, and ecological implications. Ocean Modelling, 110, 66–82. [Google Scholar]

- Sandin SA, Smith JE, DeMartini EE, Dinsdale EA, Donner SD, Friedlander AM, … Sala E. (2008). Baselines and degradation of coral reefs in the northern Line Islands. PLoS One, 3(2), e1548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shogren AJ, Tank JL, Andruszkiewicz E, Olds B, Mahon AR, Jerde CL, & Bolster D. (2017). Controls on eDNA movement in streams: Transport, retention, and resuspension. Scientific Reports, 7(1), 5065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spens J, Evans AR, Halfmaerten D, Knudsen SW, Sengupta ME, Mak SS, … Hellström M. (2017). Comparison of capture and storage methods for aqueous macrobial eDNA using an optimized extraction protocol: Advantage of enclosed filter. Methods in Ecology and Evolution, 8(5), 635–645. [Google Scholar]

- Stat M, Huggett MJ, Bernasconi R, DiBattista JD, Berry TE, Newman SJ, … Bunce M. (2017). Ecosystem biomonitoring with eDNA: Metabarcoding across the tree of life in a tropical marine environment. Scientific Reports, 7(1), 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streit WR, & Schmitz RA. (2004). Metagenomics–the key to the uncultured microbes. Current Opinion in Microbiology, 7(5), 492–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi S, Sakata MK, Minamoto T, & Masuda R. (2020). Comparing the efficiency of open and enclosed filtration systems in environmental DNA quantification for fish and jellyfish. PLoS One, 15(4), e0231718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Titcomb GC, Jerde CL, & Young HS. (2019). High-throughput sequencing for understanding the ecology of emerging infectious diseases at the wildlife-human interface. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, 7, 126 [Google Scholar]

- West KM, Stat M, Harvey ES, Skepper CL, DiBattista JD, Richards ZT, … Bunce M. (2020). eDNA metabarcoding survey reveals fine-scale coral reef community variation across a remote, tropical Island ecosystem. Molecular Ecology, 29, 1069–1086. 10.1111/mec.15382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams ID, Richards BL, Sandin SA, Baum JK, Schroeder RE, Nadon MO, … Brainard RE. (2011). Differences in reef fish assemblages between populated and remote reefs spanning multiple archipelagos across the central and western Pacific. Journal of Marine Biology, 2011, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto S, Minami K, Fukaya K, Takahashi K, Sawada H, Murakami H, … Kondoh M. (2016). Environmental DNA as a “snapshot” of fish distribution: A case study of Japanese jack mackerel in Maizuru Bay, sea of Japan. PLoS One, 11(3), e0149786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.