Abstract

Polyphenols are secondary metabolites produced in higher plants. They are known to possess various functional properties in the human body. Polyphenols also exhibit antibacterial activities against foodborne pathogens. Their antibacterial mechanism is based on inhibiting bacterial biofilm formation or inactivating enzymes. Food-derived polyphenols with such antibacterial activity are natural preservatives and can be used as an alternative to synthetic preservatives that can cause side effects, such as allergies, asthma, skin irritation, and cancer. Studies have reported that polyphenols have positive effects, such as decreasing harmful bacteria and increasing beneficial bacteria in the human gut microbiota. Polyphenols can also be used as natural antibacterial agents in food packaging system in the form of emitting sachets, absorbent pads, and edible coatings. We summarized the antibacterial activities, mechanisms and applications of polyphenols as antibacterial agents against foodborne bacteria.

Keywords: Polyphenol, Foodborne pathogen, Antibacterial activity, Antibacterial mechanism, Natural antibacterial agents

Introduction

Foodborne diseases are caused by consuming food contaminated with pathogenic bacteria, viruses, natural toxins, chemical residues, or parasites. Annually, these diseases adversely affect people's health and result in economic losses (Zhang et al., 2021). According to a report by the World Health Organization, it is estimated that, yearly, there are global outbreak of 600 million foodborne diseases, resulting in 420,000 deaths (Oliver, 2019). Among them, the main cause of foodborne disease is bacteria (66%) and the most common types are intoxication and infection (Addis and Sisay, 2015). Foodborne pathogens that cause foodborne diseases include Campylobacter jejuni, Bacillus cereus, Clostridium perfringens, Cronobacter sakazakii, Listeria monocytogenes, Escherichia coli, Salmonella spp., Staphylococcus aureus, Shigella spp., Vibrio spp., Yersinia enterocolitica, etc. (Bintsis et al., 2017).

Synthetic preservatives, such as formaldehyde, benzoate, sulfite, and nitrate, are used to inhibit the growth of microorganisms (Quinto et al., 2019). However, the safety of such preservatives is questionable as it can be associated with problems, such as allergies, asthma, skin irritation, and cancer (Silva et al., 2016; Quinto et al., 2019). In addition, consumers are increasingly aware of the adverse health effects associated with chemically synthesized preservatives, and as the demand for healthy and safe foods increases, the use of natural antimicrobials by both consumers and food manufacturers is rising (Bouarab-Chibane et al., 2019a; Rico et al., 2007).

Polyphenols have a structure of one or more aromatic rings with one or more hydroxyl groups, and more than 8,000 phenolic structures have been identified as natural compounds widely distributed in seeds, bark, leaves, roots, and fruits in the plant kingdom (Olszewska et al., 2020; Zhang and Tsao, 2016). Recently, polyphenols have been reported to exhibit antibacterial properties, inhibiting the growth of various pathogens, and can therefore be an alternative to other natural preservatives that can negatively affect the taste and sensory aspects of foods (Quinto et al., 2019). Polyphenols with antimicrobial activity also prevent the development of antibiotic resistance in bacteria (Xie et al., 2017). Hence, polyphenols have a positive effect as a natural preservative, receiving worldwide attention (Dhalaria et al., 2020).

In this paper, the antibacterial activity of polyphenols targeting food-borne pathogens and their mechanisms were summarized and investigated. In addition, the applicability of polyphenols as natural antibacterial agents was suggested by decreasing in harmful bacteria in gut microbiota and by inhibiting the growth of pathogenic bacteria in food packaging systems.

Antibacterial activities of various types of polyphenols

Polyphenols are secondary metabolites that are naturally produced in higher plants. Some of them inhibit the growth of various types of microorganisms, such as bacteria, virus, and fungi, and also have antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities (Daglia, 2012; Kumar et al., 2021; Sliva, 2020). These polyphenols include flavonoids, phenolic acids, tannins, and stilbenoids (Kumar et al., 2021). Table 1 summarizes the antibacterial activities of polyphenols according to their structures against foodborne pathogens.

Table 1.

Antibacterial activities of polyphenols against foodborne pathogen

| Class name | Subclass name | Compounds | Test method | Bacterial strain | Antibacterial activity | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flavonoid | Flavan-3-ol | (-)-Gallocatechin-3-gallate | BA50 | Bacillus cereus | 0.43 ± 0.14 nmol/well | Friedman et al. (2006) |

| Epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) | Biofilm formation | Escherichia coli O157:H7 | decreased to 56.4% at 5 µg/mL | Lee et al. (2009) | ||

| Swarming motility | Escherichia coli O157:H7 | decreased to 82.3% at µg/mL | Lee et al. (2010) | |||

| MIC |

Staphylococcus spp. Bacillus cereus Bacillus subtilis Clostridium perfringens Listeria monocytogenes Staphylococcus aureus |

50–100 µg/mL 267 µg/mL 533 µg/mL 50 µg/mL 400 µg/mL 133 µg/mL |

Taguri et al. (2006) | |||

| Flavonol | Galangin | MIC | Staphylococcus aureus | 50 µg/mL | Cushnie and Lamb (2005a, b) | |

| Viability | Staphylococcus aureus |

60-fold decrease at 50 μg/mL 1000-fold decrease at 1% |

Cushinie et al. (2003) | |||

| Myricetin-3-O-rhamnoside | MIC |

Bacillus subtilis Escherichia coli Klebsiella pneumoniae Staphylococcus aureus Candida albicans |

0.25 mg/mL 0.25 mg/mL 0.25 mg/mL 0.25 mg/mL 0.25 mg/mL |

Aderogba et al. (2013) | ||

| Quercetin-3-O-rhamnoside | MIC |

Bacillus subtilis Escherichia coli Klebsiella pneumoniae Staphylococcus aureus Candida albicans |

0.13 mg/mL > 0.25 mg/mL > 0.25 mg/mL > 0.25 mg/mL 0.25 mg/mL |

Aderogba et al. (2013) | ||

| Quercetin | MIC |

Bacillus subtilis Escherichia coli Klebsiella pneumoniae Staphylococcus aureus Candida albicans |

0.03 mg/mL > 0.25 mg/mL 0.25 mg/mL > 0.25 mg/mL 0.02 mg/mL |

Aderogba et al. (2013) | ||

| Flavanone | Sophoraflavanone G | MIC | Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus | 3.13–6.25 µg/mL | Tsuchiya et al. (1996) | |

| Exiguaflavanone D | MIC | Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus | 3.13–6.25 µg/mL | Tsuchiya et al. (1996) | ||

| Macatrichocarpins A | MIC |

Bacillus subtilis Staphylococcus aureus Enterobacter aerogenes Escherichia coli Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Salmonella typhi Shigella dysenteriae Vibrio cholerae |

26.5 µM 105.8 µM 423.3 µM 105.8 µM 211.6 µM 211.6 µM 105.8 µM 105.8 µM |

Fareza et al. (2014) | ||

| Macatrichocarpins B | MIC |

Bacillus subtilis Staphylococcus aureus Enterobacter aerogenes Escherichia coli Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Salmonella typhi Shigella dysenteria Vibrio cholerae |

50.9 µM 101.8 µM 101.8 µM 50.9 µM 50.9 µM 203.6 µM 50.9 µM 50.9 µM |

Fareza et al. (2014) | ||

| 4',7-di-O-methylnaringenin | MIC |

Bacillus subtilis Staphylococcus aureus Enterobacter aerogenes Escherichia coli Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Salmonella typhi Shigella dysenteriae Vibrio cholerae |

50.9 µM 101.8 µM 101.8 µM 50.9 µM 50.9 µM 203.6 µM 50.9 µM 50.9 µM |

Fareza et al. (2014) | ||

| Phenolic acid | Hydroxybenzoic acids | Gallic acid | Paper disc method | Escherichia coli | 12 mm at 2.5 mg/well | Díaz-Gómez et al. (2014) |

| MIC |

Pseudomonas aeruginosa Escherichia coli Staphylococcus aureus Listeria monocytogenes |

500 mg/mL 1500 mg/mL 1750 mg/mL 2000 mg/mL |

Borges et al. (2013) | |||

| Hydroxycinnamic acids | Ferulic acid | MIC |

Pseudomonas aeruginosa Escherichia coli Staphylococcus aureus Listeria monocytogenes |

100 mg/mL 100 mg/mL 1100 mg/mL 1250 mg/mL |

Borges et al. (2013) | |

| p-Coumaric acid | MIC |

Bacillus cereus Staphylococcus aureus Listeria monocytogenes Escherichia coli Shigella dysenteriae Salmonella typhimurium |

24 μg/mL 24 μg/mL 24 μg/mL 49–80 μg/mL 10 μg/mL 20–49 μg/mL |

Lou et al. (2012) Camargo et al. (2017) |

||

| Tannin | Hydrolysable tannin | Tannin acid | Paper disc method |

Escherichia coli Klebsiella pneumoniae Listeria monocytogenes Staphylococcus aureus Yersinia enterocolitica Streptococcus faecalis |

13.25 mm at 5 mg/mL 14.75 mm at 5 mg/mL 18.00 mm at 5 mg/mL 11.50 mm at 5 mg/mL 14.75 mm at 5 mg/mL 12.50 mm at 5 mg/mL |

Chung et al. (1993) |

| MIC |

Bacillus cereus Bacillus subtilis Clostridium perfringens Listeria monocytogenes Staphylococcus aureus |

533 µg/mL 667 µg/mL, 50 µg/mL 1600 µg/mL, 400 µg/mL |

Taguri et al. (2006) | |||

| Castalagin | MIC |

Escherichia coli Staphylococcus aureus Bacillus cereus Bacillus subtilis, Clostridium perfringens Listeria monocytogenes |

533 µg/mL 267 µg/mL 467 µg mL 600 µg/mL 67 µg/mL 667 µg/mL |

Puljula et al. (2020) | ||

| Taguri et al. (2006) | ||||||

| Punicalagin | MIC |

Escherichia coli Staphylococcus aureus Bacillus cereus Bacillus subtilis, Clostridium perfringens Listeria monocytogenes |

2133 µg/mL 600 µg/mL 667 µg/mL 467 µg/mL 67 µg/mL 3200 µg/mL |

Puljula et al. (2020) | ||

| Taguri et al. (2006) | ||||||

| Ellagitannin | Average growth inhibition | Escherichia coli |

oligomeric ellagitannins with a 0.5 mM: 97% monomeric ellagitannins with a 0.5 mM: 63% |

Puljula et al. (2020) | ||

| Average growth inhibition | Clostridium perfringens |

oligomeric ellagitannins with a 0.5 mM: 77% monomeric ellagitannins with a 0.5 mM: 61% |

Puljula et al. (2020) | |||

| Condensed Tannin | - | Paper disc method |

Staphylococcus aureus Bacillus subtilis Streptococcus faecalis Salmonella choleraesuis Enterococcus faecium |

8 mm 8 mm 7 mm 9 mm 9 mm |

Zarin et al. (2016) | |

| MIC |

Staphylococcus aureus Bacillus subtilis Streptococcus faecalis Salmonella choleraesuis Enterococcus faecium |

12.5 mg/mL 12.5 mg/mL 25 mg/mL 25 mg/mL 50 mg/mL |

Zarin et al. (2016) | |||

| Stilbenoids | - | Resveratrol | MIC |

Listeria monocytogenes Pseudomonas aeruginosa Escherichia coli |

50 ~ 200 μg/mL > 400 μg/mL > 400 μg/mL |

Mattio et al. (2020) Vestergaard and Ingmer (2019) |

| Extract from roots of Stemona japonica | MIC |

Staphylococcus aureus Staphylococcus epidermidis |

25 ~ 50 µg/mL 12.5 ~ 25 µg/mL |

Yang et al. (2006) | ||

| Extract from Stemona tuberosa | MIC | Klebsiella pneumoniae | 50 µg/mL | Lin et al. (2008) |

BA50 (Bactericidal activity) = defined as 50% decrease in the number of CFU, MIC (Minimum inhibitory concentration) = Lowest concentration of the compound resulting in 100% inhibition of bacterial growth

Flavonoids

Flavonoids are easily found in natural products, such as fruit, vegetable, and nuts. They are characterized by 15 carbon skeletons and have two aromatic rings containing 2-phenyl-benzo[α]pyrene or flavan nucleus connected by a heterocyclic pyran ring (Cushnie and Lamb, 2005a, b). Naturally occurring flavonoids exists mainly in glycosylated or esterified forms (Yang and Xiao, 2013). Flavonoids classified according to the differences in oxygenated heterocycles exist in various forms, such as chalcones, flavan-3-ols (catechin), flavonols, flavones, flavanones, and anthocyanidins (Cho et al., 2017; Kumar et al., 2021). Among them, flavan-3-ols, flavonols, and flavanones have a wide spectrum that exhibits high antibacterial activities so it can inhibit various foodborne pathogens, such as B. cereus, E. coli O157:H7, S. aureus, etc. (Boudjemaa, 2017; Daglia, 2012; Taguri et al., 2006; Tsao, 2010).

Flavan-3-ols

Flavan-3-ols, which are present in tea, cocoa, wine, grape, apple, peach, and bean, exist either as monomeric catechins or in a complex form with polymeric procyanidins (Manach et al., 2004; Neilson and Ferruzzi, 2011). They are subdivided according to the degree of polymerization, oxidation state, and the pattern in which the B and C rings are substituted (Neilson and Ferruzzi, 2011). According to Friedman et al. (2006), it was reported that the 3-gallate ester group present in (-)-gallocatechin-3-gallate (GCG) plays an important role in its activity. At a concentration of 0.43 ± 0.14 nmol/well, the number of CFUs of B. cereus was reduced by 50% (Friedman et al., 2006). Lee et al. (2009) reported that the activity of (-)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG), which reduced E. coli O157:H7 biofilm formation by 56.4% and inhibited colony migration, was associated with decreased production of autoinducer-2. Table 1 shows the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) concentrations of EGCG against Staphylococcus spp., C. perfringens, and other pathogenic bacteria.

Flavonols

Flavonols, commonly found in propolis, broccoli, kale, onion, blueberries, tomatoes, tea, and wine, exist in glycosylated forms (Manach et al., 2004). In addition, the B-ring exists most often in the form with hydroxyl (OH) groups at the C-3' and C-4' positions (Aherne and O’Brien, 2002). When the cytoplasm is damaged by toxic compounds, the cell releases potassium ions by the efflux system, which slows the rate of formation of fatal lesions as the cytoplasm is acidified (Epstein, 2003). S. aureus treated with galangin with a MIC concentration of 50 µg/mL lost about 21% of potassium ions in the cytoplasm compared to the control group, which was not treated with galangin (Cushnie and Lamb, 2005a, b). This suggests that galangin inhibits potassium-induced mitigation of cellular lesions. Myricetin-3-O-rhamnoside and quercetin-3-O-rhamnoside are structurally almost identical to quercetin and have antibacterial activity against B. subtilis, E. coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, S. aureus, and Candida albicans (Aderogba et al., 2013). However, the reason that the antibacterial activity is lower than that of quercetin is that sugars such as rhamnose are added to the 3-OH group and a hydroxyl group is added to the 5'-OH group. (Aderogba et al., 2013). Nitiema et al. (2012) reported that quercetin has fewer free OH groups than other phenolic compounds, which increases the chemical affinity for the microbial lipid membrane, and thus, possesses more antibacterial activities. Table 1 shows that quercetin exhibited a MIC value of 0.03 mg/mL against B. cereus, while myricetin-3-O-rhamnoside and quercetin-3-O-rhamnoside showed MIC values of 0.25 mg/mL and 0.13 mg/mL, respectively.

Flavanones

Flavanones are also found in aromatic plants, such as mint and tomato, but they are present in high concentrations in citrus fruit (Manach et al., 2004). Although flavanone itself does not show activity against methicillin resistant S. aureus (MRSA), but due to the OH group at the C-2' position of the B-ring, sophoraflavanone G and exiguaflavanone D have MIC values of 3.13–6.25 µg/mL against MRSA. (Tsuchiya et al., 1996). Prenylated flavanones, macatrichocarpin, and flavanone derivative, 4',7-di-O-methylnaringenin exhibit antibacterial activities against B. subtilis, S. aureus, Enterobacter aerogenes, E. coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Shigella dysenteria, Vibrio cholerae in the range of 50.9 to 101.8 µM (Fareza et al., 2014).

Phenolic acids

Phenolic acids are mainly found in whole grains and nuts, cocoa, fruits, and beverages, such as coffee and beer (Cueva et al., 2010; Godos et al., 2021). These acids are divided into two classes: 1) hydroxybenzoic acids, which include individual compounds, such as vanillic, gallic, salicylic acid, syringic, and protocatechuic and 2) hydroxycinnamic acids, which include ferulic, rosmarinic, p-coumaric, chlorogenic acid, cinnamic, and caffeic (Daglia, 2012; Godos et al., 2021; Manach et al., 2004). Phenolic acid has an aromatic ring with OH or methoxy groups, and the diversity is indicated by the number of OH or methoxy groups, and the antibacterial activities are related to the chemical structures (Cueva et al., 2010; Merkl et al., 2010; Sánchez‐Maldonado et al., 2011). The lengths of the saturated chains of phenolic acids were determined by the number and position of the substitutions on the benzene ring (Merkl et al., 2010; Sánchez‐Maldonado et al., 2011). Merkl et al. (2010) reported that the antibacterial effects of phenolic acids increase as the alkyl chain length increases.

Among the phenolic acids, ferulic acid showed MIC values of 1250 mg/mL and 1100 mg/mL, respectively, to the Gram-positive bacteria L. monocytogenes and S. aureus (Borges et al., 2013). In addition, ferulic acid showed MIC values of 100 mg/mL, respectively, against Gram-negative bacteria, P. aeruginosa and E. coli (Borges et al., 2013). p-coumaric acid showed antibacterial activities in E. coli, Salmonella dysenteriae and Salmonella Typhimurium (Borges et al., 2013; Lou et al., 2012). Furthermore, Camargo et al. (2017) confirmed the presence of p-coumaric and ferulic acids in dry peanuts and demonstrated antibacterial activities against B. cereus, S. aureus, L. monocytogenes, S. Typhimurium, E. coli, etc. (Camargo et al., 2017).

Tannins

Tannins, which are found in higher herbaceous and woody plants, are classified into hydrolysable tannins and condensed tannins (also called proanthocyanidin) according to their structures (Daglia, 2012; Kim et al., 2010). The hydrolysable tannins exist in the form of binding to phenolic acids and sugar esters, such as glucose (Scalbert, 1991). According to Kim et al. (2010), hydrolysable tannins prevented lipid oxidation and radical-mediated DNA-cleavage while scavenging oxygen and oxygen-derived radicals. Additionally, it has been reported that the number of free galloyl groups in ellagitannin, the type of oligomer binding, and the size of the molecule play a major role in the antibacterial activity. Ellagitannin inhibits the growth of E. coli, C. perfringens, S. aureus, and B. cereus (Puljula et al., 2020).

Condensed tannins, also called proanthocyanidins, are polymers in which flavonoids are linked through 2–50 (or more) carbon–carbon bonds, and are non-hydrolyzed, water-soluble substances (Zarin et al., 2016). In addition, condensed tannins inhibit the synthesis of beta-lactamase, which eliminates the possible development of bacterial resistance to beta-lactam antibiotics, such as penicillin and cephalosporin (Majiduddin et al., 2002). This prevents bacteria from becoming an antibiotic resistant bacteria (Joseph et al., 2016).

Stilbenoids

Stilbenoids are phenolic compounds found in various plant species, including vines, blueberries, peanuts, and pistachios. They contain stilbenes as a common backbone structure and are synthesized via the phenylpropanoid pathway in plants (Akinwumi et al., 2018). They exist as either a monomer or an oligomer, and the trans-isomer exists in a general and stable form (Akinwumi et al., 2018). Combretastatin B5 extracted from Combretum woodii leaf powder showed antibacterial activity against S. aureus (Xiao et al., 2008). Lakoochins A and Lakoochins B extracted from Artocarpus lakoocha also demonstrated antibacterial activities (Xiao et al., 2008). Resveratrol exhibited potassium leakage and propidium uptake in E. coli when treated with 182 µg/mL, indicating membrane damage, and also caused DNA damage by cleaving DNA to generate Cu (II)-peroxide complexes (Mattio et al., 2020). In addition, treatment with 228 μg/mL of resveratrol inhibits FtsZ, a key protein involved in septum formation during cell division, and interferes with cell division (Mattio et al., 2020). Resveratrol inhibited biofilm formation in Gram-negative bacteria, such as V. cholerae, P. aeruginosa, and E. coli (Mattio et al., 2020).

Mechanisms of antibacterial activities of polyphenols

Inhibition of biofilm formation (antibiofilm)

Biofilm is a community of microorganisms present on living or non-living surfaces, embedded in extracellular polysaccharides, proteins, nucleic acids, lipids, and extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) (Hall-Stoodley et al., 2004; López et al., 2010). Since biofilms are highly resistant to adverse environmental factors, such as nutrients, oxygen starvation, and pH changes, the formation of biofilms affects the growth of microorganisms and is even resistant to antimicrobial agents (Galiè et al., 2018, Miklós Takó et al., 2020). Polyphenols inhibit bacterial biofilm formation by various mechanisms, including reducing bacterial motility and surface adhesion, blocking detection, and inhibiting the expression of virulence factors associated with pathogenic behavior (Borges et al., 2012; Eydelnant et al., 2008; Khokhani et al., 2013; Miklós Takó et al., 2020; Xu et al., 2011).

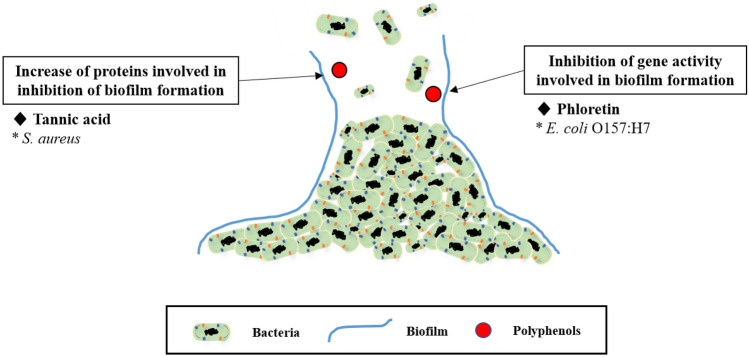

Figure 1 shows the inhibition of biofilm formation on bacteria by polyphenols. Phloretin, a flavonoid in apples, inhibits biofilm formation of E. coli O157:H7 by regulating the activity of curli genes (csgA, csgB) involved in biofilm formation (Lee et al., 2011; Payne et al., 2013). Tannic acid in black tea also inhibits biofilm formation of S. aureus by increasing the level of protein IsaA (immunodominant staphylococcal antigen A), which is involved in inhibiting biofilm formation. (Lee et al., 2011; Payne et al., 2013). Furthermore, red wine, widely known for its high content of flavonoids, has been demonstrated to strongly inhibit biofilm formation of S. aureus by hydroxyl groups present on the flavonoids. Hydroxyl groups play an important role in the formation of hydrogen bonds. Hydrogen bonding is used in living bacteria to increase solubility in water and to bind to specific sites on DNA and proteins (Cho et al., 2015).

Fig. 1.

Inhibition of biofilm formation by polyphenols

Destruction of cell wall and membrane

One of the important roles of the cell wall is to protect against osmotic pressure in Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria (Papuc et al., 2017). When the bacterial cell wall is damaged, the osmotic pressure is lowered while the ionic strength increases, and the resistance of the bacteria is reduced (Kumar et al., 2021). While exhibiting antibacterial effects, polyphenols inhibit the growth of bacteria by damaging the cell walls (Kumar et al., 2021). In addition, polyphenols interact with the cell membranes of Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria to disrupt the phospholipid or lipid bilayers, affecting fluidity, and increasing membrane permeability, thereby altering the ion transport systems (Nazzaro et al., 2013).

Figure 2 shows the antibacterial mechanism shown by polyphenols destroying the cell wall and cell membrane of bacteria. EGCG directly binds to peptidoglycan in S. aureus and damages the cell wall, thereby lowering osmotic pressure and increasing ionic strength, which reduces cell tolerance (Zhao et al., 2002). Proanthocyanidins in cranberries exhibit antibacterial activities by binding to Lipopolysaccharide(LPS), which is a major molecular component of the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria, acting as a physical barrier to protect the bacteria from the surrounding environment (Johnson et al., 2008). Proanthocyanidins of persimmon exhibit antibacterial activities against S. aureus by inducing morphological damage to cell membrane permeability and destroying membrane integrity (Wang et al., 2020). Moreover, ferulic and gallic acids interact with cell membranes in E. coli, P. aeruginosa, S. aureus, and L. monocytogenes to reduce surface negative charges, form pores, leak intracellular components, and change hydrophobicity to exhibit antibacterial activities (Borges et al., 2013; Miklós Takó et al., 2020). p-coumaric acid from apple, pear, and quinoa was involved in antibacterial activity by altering membrane permeability and pore formation in E. coli, S. dysenteriae, and S. Typhimurium (Lou et al., 2012). Catechin causes B. subtilis and E. coli to rapidly leak small molecules from the liposome inner space to agglomerate the liposome, and this action induces membrane lipid bilayer damage and apoptosis (Buzzini et al., 2007).

Fig. 2.

Antibacterial mechanism of polyphenols

Inhibition of various enzyme activities

The B rings of flavonoids can inhibit DNA and RNA synthesis by intercalating or hydrogen bonding with nucleic acid bases of bacteria. In addition, polyphenols exhibit antibacterial activities by inhibiting DNA gyrase and blocking nucleic acid synthesis (Oblak et al., 2007). DNA gyrase, a type II isomerase, plays a role in making DNA into a negative superhelical form after replication and is used to break the link between the chromosomes of two daughter cells that are connected in a loop. Therefore, it is an enzyme that is a target for antibacterial agents (Oblak et al., 2007). DNA gyrase consists of two catalytic subunits: GyrA, which is responsible for DNA breakage and recombination, and GyrB subunit, which contains an ATP-binding site (Oblak et al., 2007).

Figure 2 shows the antibacterial mechanism by which polyphenols inhibit various enzymatic activities necessary for the growth of bacteria. It has been reported that the flavonoids, such as myricetin, robinetin, and (-)-epigallocatechin, inhibit RNA synthesis in S. aureus and DNA synthesis in Proteus vulgaris (Mori et al., 1987). One of the phenolic acids, p-coumaric acid, destroys bacterial cell membranes and induces cell death by binding to DNA (Lou et al., 2012). Coumarin and cyclothialidine inhibit DNA gyrase by blocking the binding of ATP to the subunit of GyrB and exhibit antibacterial activities (Oblak et al., 2007). Quercetin, catechin, and epigallocatechin gallate have been studied and reported to possess antibacterial activities by inhibiting bacterial DNA gyrase and blocking nucleic acid synthesis (Gradišar et al., 2007; Plaper et al., 2003).

Polyphenols bind protein non-covalently and covalently, and effect antibacterial activities by sequestering and denaturing proteins into soluble or insoluble complexes (Brudzynski et al., 2015). In addition, polyphenols bind to proteins important for bacterial growth, such as enzymes, adhesin, and cell envelope transport proteins. Thus, inhibiting the protein's functions, and thereby exhibit antibacterial activities (Makarewicz et al., 2021).

Kaempferol-3-rutinoside (nicotiflorin) showed inhibitory activity against sortase A membrane enzyme, which plays an important role in the invasion of host cells of S. mutans, and showed antibacterial activity (Yang et al., 2015). Furthermore, quercetin inhibited sortase A and B, which are enzymes necessary for protein synthesis in S. aureus (Kang et al., 2006; Spirig et al., 2011). In addition, flavonoids inhibit the growth of Mycobacterium smegmatis II (FAS-II) by inhibiting fatty acid synthase, an enzyme required for fatty acid synthesis, when making the bacterial membrane (Brown et al., 2007; Mickymaray et al., 2020). Condensed tannins exhibit antibacterial activities against S. aureus, B. subtilis, Streptococcus faecalis, S. choleraesuis, Enterococcus faecium by complexing with the bacterial outer membrane porin protein and enzymes, permeases, to inhibit microbial enzymes (Joseph et al., 2016; Zarin et al., 2016).

Application of polyphenols as antibacterial agents

Effect of polyphenols on gut microbiota

Recently, many studies have reported the effects of gut microbiota on human gut health, and accordingly, studies showing the activities of polyphenols in the gut microbiota (Albenberg and Wu, 2014; Morais et al., 2016). Polyphenols can inhibit the growth of harmful microbial species, such as C. perfringens and Helicobacter pylori and in other side can establish beneficial microbial species, such as Bifidobacteriaceae and Lactobacillaceae in the gut microbiota (Aravind et al., 2021). Dietary polyphenols also produce aromatic metabolites, when ingested, which can positively affect the health of the host (Aravind et al., 2021; Cardona et al., 2013).

Polyphenols have a complex structure and large molecular weight, so their bioavailability is low. Hence, most of them are not absorbed, and only 5%–10% of the ingested amount is directly absorbed by enzymes, such as lactase-phlorizin hydrolase in the small intestine, with 90–95% of the unabsorbed in the small intestine reaching the colon in unchanged forms (Aravind et al., 2021; Gowd et al., 2019). Polyphenols delivered to the colon are degraded into low molecular weight phenolic metabolites that can be absorbed by microorganisms (Aravind et al., 2021). These phenolic metabolites then bind to albumin and reach the liver through the portal vein, where they undergo more extensive metabolic processes, such as methylation, glucuronidation, and sulfation (Aherne and O'Brien., 2002). Eventually, they produce active metabolites, such as O-glucuronides, sulfate esters, and O-methyl ether (Scalbert et al., 2002). After reaching the target tissues and cells through the processes, the remaining metabolites are excreted through urine (Gowd et al., 2019).

Decrease in harmful bacteria

Gallic acid and caffeic acid in papaya juice have been reported to lower colonic pH and inhibit Bacteroidetes, C. perfringens, and C. difficile (Fujita et al., 2017). 3-O-methylgallate, GCG, EGC, EGCG of oolong tea reduced C. histolyticum, Eubacterium, and Bacteroides (Gowd et al., 2019). Ellagitannin from walnut inhibited the growth of the Carnobacteriaceae family, and polyphenols from green tea and red wine inhibited the growth of S. enterica and E. coli O157:H7 (Byerley et al., 2017; Tombola et al., 2003). Kaempferol, ferulic acid, quercetin, and vanillic acid in quinoa seeds inhibit the growth of E. coli and S. aureus (Ahmed 2013; Miranda et al., 2014).

Increase in beneficial bacteria

Gallic acid and caffeic acid in papaya juice were reported to promote the growth of Bifidobacteria and Eubacteria (Fujita et al., 2017). Proanthocyanidins from grape peel and grape seeds increased the numbers of Lactobacillus acidophilus, Lactobacillus reuteri, Clostridiales, and Ruminococcus in the intestine (Choy et al., 2014; Pozuelo et al., 2012). There is a study which reported that 3-O-methylgallate, gallocatechin gallate (GCG), epigallocatechin (EGC), epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) of oolong tea increased the growth of Enterococcus, Bifidobacterium, and Lactobacillus (Gowd et al., 2019). Hydroxybenzoic acids, hydroxycinnamic acids, ferulic acids, and rutin in pea hull increased colonization of L. acidophilus, Lactobacillus delbrueckii, Lactobacillus casei, L. spp. and Lactobacillus bulgaricus (Guo et al., 2019).

Application of polyphenols in food packaging systems

Food packaging plays a very important role in protecting food from bacterial infection during post-processing, distribution, and storage (Huang et al., 2019). Recently, as the environmental problems caused by synthetic plastics and the health problems associated with synthetic preservatives are increasing, studies on the applications of polyphenols, which are natural preservatives, as antibacterial food packaging materials are being actively conducted (Arcan and Yemenicioğlu, 2011; Martillanes et al., 2017). Polyphenols can prevent the growth of foodborne pathogens, such as Campylobacter, Salmonella spp., and Y. enterocolitica present on food surfaces (Huang et al., 2019). Antibacterial packaging systems utilize these polyphenols, which interact with foods and packaging headspace to inhibit the growth of spoilage and pathogenic bacteria (Otoni et al., 2016).

Types of antibacterial food packaging systems

The application of polyphenols from natural extracts in the food packaging industry can further broaden the spectrum of antibacterial food packaging systems because it can solve problems, such as environmental problems and side effects associated with the use of synthetic preservatives (Arcan and Yemenicioğlu, 2011; Martillanes et al., 2017; Olszewska et al., 2020).

Antioxidant packaging methods that can delay food spoilage caused by microbial growth can be roughly classified into two types (Roman et al., 2016). The first is a separate device, a sachet and an absorbent pad (Gómez-Estaca et al., 2014). It is installed as a separate device from food and food packaging materials and exhibits antibacterial effects (Gómez-Estaca et al., 2014; Martillanes et al., 2017). The other is an edible coating, which is a packaging material (Gómez-Estaca et al., 2014). Direct incorporation of the active agent into the packaging material releases the antioxidant compound into the food and the headspace surrounding the food and exhibits its antibacterial effect (Gómez-Estaca et al., 2014; Martillanes et al., 2017).

Emitting sachets

Emitting sachets which belongs to an independent device, exhibit antibacterial effects by applying polyphenols, such as thymol and carvacrol, which are well known for their antibacterial activity against foodborne pathogens, in the form of volatile compounds (Gómez-Estaca., 2014). These compounds are released into the headspace of the package and exhibit antibacterial activities without direct contact with food (de Azeredo et al., 2013; Gómez et al., 2014; Martillanes et al., 2017).

Absorbent pads

When a food is packaged, liquid from the food collects at the bottom of the package, which can impair food quality or promote the growth of foodborne pathogens. To solve this problem, absorbent pads can be used, which are packaging devices that can delay the growth of microorganisms by absorbing liquid from food when food is placed on an absorbent pad (de Azeredo et al., 2013). In addition, carvacrol and thymol, the main phenolic components in oregano essential oil, exhibit antibacterial activities and are additionally applied to the absorbent pads where food exudates are absorbed to extend shelf life (Adam et al., 1998; Oral et al., 2009).

Edible coating

Edible coating is made from various raw materials, such as polysaccharides, proteins, and lipids, and an antioxidant packaging agents applied in direct contact with food surfaces (Baek et al., 2021; Gómez et al., 2014; Hassan et al., 2018). Antibacterial edible coatings are more effective than the direct addition of antibacterial agents to food because they can be applied where antibacterial activity is required by selectively migrating from the packaging to the food surface (Ouattar et al., 2000). There was a study to extend the shelf life of shrimp using an edible coating material containing alginate and grapefruit seed extract containing flavonoids (Baek et al., 2021; Cvetnić et al., 2004). Furthermore, a study reported that films made from 2 to 5% pomegranate peel powder containing anthocyanins inhibited the growth of S. aureus and L. monocytogenes (Hanani et al., 2019). In addition, various research has shown significant potentials for the application of polyphenols in edible coatings as antimicrobial packaging devices (Olszewska et al., 2020).

Conclusion

Antimicrobial activity of food-derived polyphenols against food-borne pathogens has been demonstrated, and the mechanism is being studied. Due to these antibacterial properties, the application of polyphenols in food as a natural preservative to replace synthetic preservatives is environmentally friendly, which may become a promising trend for pursuing an eco-friendly and healthy life in recent years. In keeping with the trends of the food industry, it has been confirmed that studies on the potential of polyphenols to have a positive effect on the human microflora and the applicability of polyphenols in food packaging are underway. However, when polyphenol is applied to food, it has a negative effect on sensory characteristics such as taste and aroma of food. For the food industry application of polyphenols, further research is needed to improve the sensory properties and consider consumer preferences.

Acknowledgements

This work was carried out with the support of “Cooperative Research Program for Agriculture Science & Technology Development (Project No. PJ01608201)” Rural Development Administration, Republic of Korea.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Ji-Yun Bae and Yeon-Hee Seo have contributed equally.

Contributor Information

Ji-Yun Bae, Email: bjy6837@kookmin.ac.kr.

Yeon-Hee Seo, Email: syh001102@kookmin.ac.kr.

Se-Wook Oh, Email: swoh@kookmin.ac.kr.

References

- Adam K, Sivropoulou A, Kokkini S, Lanaras T, Arsenakis M. Antifungal activities of Origanum vulgare subsp. hirtum, Mentha spicata, Lavandula angustifolia, and Salvia fruticosa essential oils against human pathogenic fungi. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 1998;46:1739–1745. doi: 10.1021/jf9708296. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Addis M, Sisay D. A review on major food borne bacterial illnesses. Journal of Tropical Diseases. 2015;3:4. [Google Scholar]

- Aderogba MA, Ndhlala AR, Rengasamy KR, Van Staden J. Antibacterial and selected in vitro enzyme inhibitory effects of leaf extracts, flavonols and indole alkaloids isolated from Croton menyharthii. Molecules. 2013;18:12633–12644. doi: 10.3390/molecules181012633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aherne SA, O’Brien NM. Dietary flavonols: chemistry, food content, and metabolism. Nutrition. 2002;18:75–81. doi: 10.1016/S0899-9007(01)00695-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed SA, Hanif S, Iftkhar T. Phytochemical profiling with antioxidant and antibacterial screening of Amaranthus viridis L. leaf and seed extracts. Open Journal of Medical Microbiology. 2013;3:164–171. doi: 10.4236/ojmm.2013.33025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Akinwumi BC, Bordun KM, Anderson HD. Biological activities of stilbenoids. International journal of molecular sciences. 2018;19:792. doi: 10.3390/ijms19030792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albenberg LG, Wu GD. Diet and the intestinal microbiome: associations, functions, and implications for health and disease. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:1564–1572. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.01.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aravind SM, Wichienchot S, Tsao R, Ramakrishnan S, Chakkaravarthi S. Role of dietary polyphenol on gut microbiota, their metabolites and health benefits. Food Research International. 2021;142:110189. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2021.110189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arcan I, Yemenicioğlu A. Incorporating phenolic compounds opens a new perspective to use zein films as flexible bioactive packaging materials. Food Research International. 2011;44:550–556. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2010.11.034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baek JH, Lee SY, Oh SW. Enhancing safety and quality of shrimp by nanoparticles of sodium alginate-based edible coating containing grapefruit seed extract. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules. 2021;189:84–90. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2021.08.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borges A, Saavedra MJ, Simões M. The activity of ferulic and gallic acids in biofilm prevention and control of pathogenic bacteria. Biofouling. 2012;28:755–767. doi: 10.1080/08927014.2012.706751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borges A, Ferreira C, Saavedra MJ, Simões M. Antibacterial activity and mode of action of ferulic and gallic acids against pathogenic bacteria. Microbial Drug Resistance. 2013;19:256–265. doi: 10.1089/mdr.2012.0244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boudjemaa H. Antibacterial activity of ethyl acetate extracts from algerian Cupressus sempervirens var Against some human pathogens bacteria. Algerian journal of natural products. 2017;5:524–529. [Google Scholar]

- Brown AK, Papaemmanouil A, Bhowruth V, Bhatt A, Dover LG, Besra GS. Flavonoid inhibitors as novel antimycobacterial agents targeting Rv0636, a putative dehydratase enzyme involved in Mycobacterium tuberculosis fatty acid synthase II. Microbiology. 2007;153:3314–3322. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2007/009936-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brudzynski K, Maldonado-Alvarez L. Polyphenol-protein complexes and their consequences for the redox activity, structure and function of honey. A current view and new hypothesis-a review. Polish Journal of Food and Nutrition Sciences. 2015;65:71–80. doi: 10.1515/pjfns-2015-0030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Buzzini P, Turchetti B, Ieri F, Goretti M, Branda E, Mulinacci N, Romani A. Catechins and proanthocyanidins: naturally occurring O-heterocycles with antibacterial activity. Bioactive Heterocycles IV. 239–263 (2007)

- Byerley LO, Samuelson D, Blanchard E, Luo M, Lorenzen BN, Banks S, Ponder MA, Welsh DA, Taylor CM. Changes in the gut microbial communities following addition of walnuts to the diet. The Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry. 2017;48:94–102. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2017.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardona F, Andrés-Lacueva C, Tulipani S, Tinahones FJ, Queipo-Ortuño MI. Benefits of polyphenol on gut microbiota and implications in human health. The Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry. 2013;24:1415–1422. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2013.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho HS, Lee JH, Cho MH, Lee J. Red wines and flavonoids diminish Staphylococcus aureus virulence with anti-biofilm and anti-hemolytic activities. Biofouling. 2015;31(1):1–11. doi: 10.1080/08927014.2014.991319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho JJ, Kim HS, Kim CH, Cho SJ. Interaction with polyphenols and antibiotics. Journal of Life Science. 2017;27:476–481. doi: 10.5352/JLS.2017.27.4.476. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Choy YY, Quifer-Rada P, Holstege DM, Frese SA, Calvert CC, Mills DA, Lamuela-Raventos RM, Waterhouse AL. Phenolic metabolites and substantial microbiome changes in pig feces by ingesting grape seed proanthocyanidins. Food and Function. 2014;5:2298–2308. doi: 10.1039/C4FO00325J. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung KT, Stevens SE, Jr, Lin WF, Wei CI. Growth inhibition of selected food-borne bacteria by tannic acid, propyl gallate and related compounds. Letters in Applied Microbiology. 1993;17:29–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765X.1993.tb01428.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cueva C, Moreno-Arribas MV, Martinez-Alvarez PJ, Bills G, Vicente MF, Basilio A, Lopez Rivas C, Requena T, Rodríguez JM, Bartolomé B. Antibacterial activity of phenolic acids against commensal, probiotic and pathogenic bacteria. Research Microbiology. 2010;16:372–382. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2010.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cushnie TPT, Lamb AJ. Antibacterial activity of flavonoids. International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents. 2005;26(5):343–356. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2005.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cushnie TPT, Lamb AJ. Detection of galangin-induced cytoplasmic membrane damage in Staphylococcus aureus by measuring potassium loss. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2005;101:243–248. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2005.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cushnie TPT, Hamilton VE, Lamb AJ. Assessment of the antibacterial activity of selected flavonoids and consideration of discrepancies between previous reports. Microbiological Research. 2003;158:281–289. doi: 10.1078/0944-5013-00206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cvetnić Z, Vladimir-Knežević S. Antibacterial activity of grapefruit seed and pulp ethanolic extract. Acta Pharmaceutica. 2004;54:243–250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daglia M. Polyphenol as antibacterial agents. Current Opinion in Biotechnology. 2012;23:174–181. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2011.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Azeredo HMC. Antibacterial nanostructures in food packaging. Trends in Food Science & Technology. 2013;30:56–69. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2012.11.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- de Camargo AC, Regitan-d’Arce MAB, Rasera GB, Canniatti-Brazaca SG, do Prado-Silva L, Alvarenga VO, Sant’Ana AS, Shahidi F. Phenolic acids and flavonoids of peanut by-products: Antioxidant capacity and antibacterial effects. Food Chemistry. 2017;237:538–544. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2017.05.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhalaria R, Verma R, Kumar D, Puri S, Tapwal A, Kumar V, Puri S, Tapwai A, Kumar V, Nepovimova E, Kuca K. Bioactive compounds of edible fruits with their anti-aging properties: A comprehensive review to prolong human life. Antioxidants. 2020;9(11):1123. doi: 10.3390/antiox9111123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Díaz-Gómez R, Toledo-Araya H, López-Solís R, Obreque-Slier E. Combined effect of gallic acid and catechin against Escherichia coli. LWT-Food Science and Technology. 2014;59:896–900. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2014.06.049. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein W. The roles and regulation of potassium in bacteria. Progress in Nucleic Acid Research and Molecular Biology. 2003;75:293–320. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6603(03)75008-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eydelnant IA, Tufenkji N. Cranberry derived proanthocyanidins reduce bacterial adhesion to selected biomaterials. Langmuir. 2008;24:10273–10281. doi: 10.1021/la801525d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman M, Henika PR, Levin CE, Mandrell RE, Kozukue N. Antimicrobial activities of tea catechins and theaflavins and tea extracts against Bacillus cereus. Journal of Food Protection. 2006;69:354–361. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-69.2.354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita Y, Tsuno H, Nakayama J. Fermented papaya preparation restores age-related reductions in peripheral blood mononuclear cell cytolytic activity in tube-fed patients. PLOS ONE. 2017;12:e0169240. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0169240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galiè S, García-Gutiérrez C, Miguélez EM, Villar CJ, Lombó F. Biofilms in the food industry: Health aspects and control methods. Frontiers in Microbiology. 2018;9:898. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.00898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godos J, Caraci F, Micek A, Castellano S, Dmico E, Paladino N, Ferri R, Galvano F, Grosso G. Dietary phenolic acids and their major food sources are associated with cognitive status in older italian adults. Antioxidants. 2021;10:700. doi: 10.3390/antiox10050700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Estaca J, López-de-Dicastillo C, Hernández-Muñoz P, Catalá R, Gavara R. Advances in antioxidant active food packaging. Trends in Food Science and Technology. 2014;35:42–51. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2013.10.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gowd V, Karim N, Shishir MRI, Xie L, Chen W. Dietary polyphenol to combat the metabolic diseases via altering gut microbiota. Trends in Food Science and Technology. 2019;93:81–93. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2019.09.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gradišar H, Pristovšek P, Plaper A, Jerala R. Green tea catechins inhibit bacterial DNA gyrase by interaction with its ATP binding site. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2007;50:264–271. doi: 10.1021/jm060817o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo F, Xiong H, Wang X, Jiang L, Yu N, Hu Z, Sun Y, Tsao R. Phenolics of green pea (Pisum sativum L.) hulls, their plasma and urinary metabolites, bioavailability, and in vivo antioxidant activities in a rat model. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2019;67:11955–11968. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.9b04501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall-Stoodley L, Costerton JW, Stoodley P. Bacterial biofilms: from the natural environment to infectious diseases. Nature Reviews Microbiology. 2004;2:95–108. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanani ZAN, Yee FC, Nor-Khaizura MAR. Effect of pomegranate (Punica granatum L.) peel powder on the antioxidant and antibacterial properties of fish gelatin films as active packaging. Food Hydrocolloids. 2019;89:253–259. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2018.10.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hassan B, Chatha SAS, Hussain AI, Zia KM, Akhtar N. Recent advances on polysaccharides, lipids and protein based edible films and coatings: A review. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules. 2018;109:1095–1107. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.11.097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang T, Qian Y, Wei J, Zhou C. Polymeric antibacterial food packaging and its applications. Polymers. 2019;11:560. doi: 10.3390/polym11030560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson BJ, Delehanty JB, Lin B, Ligler FS. Immobilized proanthocyanidins for the capture of bacterial lipopolysaccharides. Analytical Chemistry. 2008;80:2113–2117. doi: 10.1021/ac7024128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph N, Mirelle AFR, Matchawe C, Patrice DN, Josaphat N. Evaluation of the antimicrobial activity of tannin extracted from the barks of Erythrophleum guineensis (Caesalpiniaceae) Journal of Pharmacognosy and Phytochemistry. 2016;5:287. [Google Scholar]

- Kang SS, Kim JG, Lee TH, Oh KB. Flavonols inhibit sortases and sortase-mediated Staphylococcus aureus clumping to fibrinogen. Biological and Pharmaceutical Bulletin. 2006;29:1751–1755. doi: 10.1248/bpb.29.1751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khokhani D, Zhang C, Li Y, Wang Q, Zeng Q, Yamazaki A, Hutchins W, Zhou SS, Chen X, Yang CH. Discovery of plant phenolic compounds that act as type III secretion system inhibitors or inducers of the fire blight pathogen, Erwinia Amylovora. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2013;79:5424–5436. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00845-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim TJ, Silva JL, KimJung MKYS. Enhanced antioxidant capacity and antimicrobial activity of tannic acid by thermal processing. Food Chemistry. 2010;118:740–746. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2009.05.060. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar H, Bhardwaj K, Cruz-Martins N, Nepovimova E, Oleksak P, Dhanjal DS, Kuča K. Applications of fruit polyphenol and their functionalized nanoparticles against foodborne bacteria: a mini review. Molecules. 2021;26:3447. doi: 10.3390/molecules26113447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee KM, Kim WS, Lim J, Nam S, Youn MIN, Nam SW, Kim Y, Kim SH, Park W, Park S. Antipathogenic properties of green tea polyphenol epigallocatechin gallate at concentrations below the MIC against enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157: H7. Journal of Food Protection. 2009;72:325–331. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-72.2.325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JH, Regmi SC, Kim JA, Cho MH, Yun H, Lee CS, Lee J. Apple flavonoid phloretin inhibits Escherichia coli O157:H7 biofilm formation and ameliorates colon inflammation in rats. Infection and Immunity. 2011;79:4819–4827. doi: 10.1128/IAI.05580-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin LG, Yang XZ, Tang CP, Ke CQ, Zhang JB, Ye Y. Antibacterial stilbenoids from the roots of Stemona tuberosa. Phytochemistry. 2008;69:457–463. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2007.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López D, Vlamakis H, Kolter R. Biofilms. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology. 2010;2:a000398. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a000398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lou Z, Wang H, Rao S, Sun J, Ma C, Li J. p-Coumaric acid kills bacteria through dual damage mechanisms. Food Control. 2012;25:550–554. doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2011.11.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Majiduddin FK, Materon IC, Palzkill TG. Molecular analysis of beta-lactamase structure and function. International Journal of Medical Microbiology. 2002;292:127–137. doi: 10.1078/1438-4221-00198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makarewicz M, Drożdż I, Tarko T, Duda-Chodak A. The Interactions between polyphenols and microorganisms, especially gut microbiota. Antioxidants. 2021;10:188. doi: 10.3390/antiox10020188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manach C, Scalbert A, Morand C, Rémésy C, Jiménez L. Polyphenol: food sources and bioavailability. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2004;79:727–747. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/79.5.727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martillanes S, Rocha-Pimienta J, Cabrera-Bañegil M, Martín-Vertedor D, Delgado-Adámez J. Application of phenolic compounds for food preservation: Food additive and active packaging. Phenolic compounds–biological activity. IntechOpen. pp. 39–58 (2017)

- Mattio LM, Catinella G, Dallavalle S, Pinto A. Stilbenoids: A natural arsenal against bacterial pathogens. Antibiotics. 2020;9:336. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics9060336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merkl R, Hrádková I, Filip V, Šmidrkal J. Antibacterial and antioxidant properties of phenolic acids alkyl esters. Czech Journal of Food Sciences. 2010;28:275–279. doi: 10.17221/132/2010-CJFS. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mickymaray S, Alfaiz F, Paramasivam A. Efficacy and mechanisms of flavonoids against the emerging opportunistic nontuberculous mycobacteria. Antibiotics. 2020;9:450. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics9080450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda M, Delatorre-Herrera J, Vega-Gálvez A, Jorquera E, Quispe-Fuentes I, Martínez EA. Antibacterial potential and phytochemical content of six diverse sources of quinoa seeds (Chenopodium quinoa Willd.). Agricultural Sciences. 5: 1015 (2014)

- Morais CA, de Rosso VV, Estadella D, Pisani LP. Anthocyanins as inflammatory modulators and the role of the gut microbiota. The Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry. 2016;33:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2015.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori A, Nishino C, Enoki N, Tawata S. Antibacterial activity and mode of action of plant flavonoids against Proteus vulgaris and Staphylococcus aureus. Phytochemistry. 1987;26:2231–2234. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9422(00)84689-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nazzaro F, Fratianni F, DeMartino L, Coppola R, DeFeo V. Effect of essential oils on pathogenic bacteria. Pharmaceuticals. 2013;6:1451–1474. doi: 10.3390/ph6121451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neilson AP, Ferruzzi MG. Influence of formulation and processing on absorption and metabolism of flavan-3-ols from tea and cocoa. Annual Review of Food Science and Technology. 2011;2:125–151. doi: 10.1146/annurev-food-022510-133725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nitiema LW, Savadogo A, Simpore J, Dianou D, Traore AS. In vitro antibacterial activity of some phenolic compounds (coumarin and quercetin) against gastroenteritis bacterial strains. International Journal of Microbiology Research. 2012;3:183–187. [Google Scholar]

- Oblak M, Kotnik M, Solmajer T. Discovery and Development of ATPase inhibitors of DNA gyrase as antibacterial agents. Current Medicinal Chemistry. 2007;14:2033–2047. doi: 10.2174/092986707781368414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver SP. Foodborne pathogens and disease special issue on the national and international PulseNet network. Foodborne Pathogens and Disease. 2019;16:439–440. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2019.29012.int. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olszewska MA, Gędas A, Simões M. Antibacterial polyphenol-rich extracts: Applications and limitations in the food industry. Food Research International. 2020;134:109214. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2020.109214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oral N, Vatansever L, Sezer C, Aydın B, Güven A, Gülmez M, Başer KH, Kürkçüoğlu M. Effect of absorbent pads containing oregano essential oil on the shelf life extension of overwrap packed chicken drumsticks stored at four degrees Celsius. Poultry Science. 2009;88:1459–1465. doi: 10.3382/ps.2008-00375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otoni CG, Espitia PJP, Avena-Bustillos RJ, McHugh TH. Trends in antibacterial food packaging systems: Emitting sachets and absorbent pads. Food Research International. 2016;83:60–73. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2016.02.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ouattar B, Simard RE, Piett G, Bégin A, Holley RA. Inhibition of surface spoilage bacteria in processed meats by application of antibacterial films prepared with chitosan. International Journal of Food Microbiology. 2000;62:139–148. doi: 10.1016/S0168-1605(00)00407-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papuc C, Goran GV, Predescu CN, Nicorescu V, Stefan G. Plant polyphenol as antioxidant and antibacterial agents for shelf-life extension of meat and meat products: Classification, structures, sources, and action mechanisms. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety. 2017;16:1243–1268. doi: 10.1111/1541-4337.12298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payne DE, Martin NR, Parzych KR, Rickard AH, Underwood A, Boles BR. Tannic acid inhibits Staphylococcus aureus surface colonization in an IsaA-dependent manner. Infection and Immunity. 2013;81:496–504. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00877-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plaper A, Golob M, Hafner I, Oblak M, Solmajer T, Jerala R. Characterization of quercetin binding site on DNA gyrase. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2003;306:530–536. doi: 10.1016/S0006-291X(03)01006-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pozuelo MJ, Agis-Torres A, Hervert-Hernández D, Elvira López-Oliva M, Muñoz-Martínez E, Rotger R, Goni I. Grape antioxidant dietary fiber stimulates Lactobacillus growth in rat cecum. Journal of Food Science. 2012;77:H59–H62. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3841.2011.02520.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puljula E, Walton G, Woodward MJ, Karonen M. Antimicrobial activities of ellagitannins against Clostridiales perfringens, Escherichia coli Lactobacillus Plantarum and Staphylococcus Aureus. Molecules. 2020;25:3714. doi: 10.3390/molecules25163714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinto EJ, Caro I, Villalobos-Delgado LH, Mateo J, De-Mateo-Silleras B, Redondo-Del-Río MP. Food safety through natural antimicrobials. Antibiotics. 2019;8:208. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics8040208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roman MJ, Decker EA, Goddard JM. Biomimetic polyphenol coatings for antioxidant active packaging applications. Colloid and Interface Science Communications. 2016;13:10–13. doi: 10.1016/j.colcom.2016.06.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Maldonado AF, Schieber A, Gänzle MG. Structure–function relationships of the antibacterial activity of phenolic acids and their metabolism by lactic acid bacteria. Journal of Applied Microbiology. 2011;111:1176–1184. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2011.05141.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scalbert A. Antimicrobial properties of tannins. Phytochemistry. 1991;30:3875–3883. doi: 10.1016/0031-9422(91)83426-L. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Scalbert A, Morand C, Manach C, Rémésy C. Absorption and metabolism of polyphenols in the gut and impact on health. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy. 2002;56:276–282. doi: 10.1016/S0753-3322(02)00205-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva RFM, Pogačnik L. Polyphenols from food and natural products: Neuroprotection and safety. Antioxidants. 2020;9:61. doi: 10.3390/antiox9010061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spirig T, Weiner EM, Clubb RT. Sortase enzymes in Gram-positive bacteria. Molecular Microbiology. 2011;82:1044–1059. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07887.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taguri T, Tanaka T, Kouno I. Antibacterial spectrum of plant polyphenols and extracts depending upon hydroxyphenyl structure. Biological and Pharmaceutical Bulletin. 2006;29:2226–2235. doi: 10.1248/bpb.29.2226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takó M, Kerekes EB, Zambrano C, Kotogán A, Papp T, Krisch J, Vágvölgyi C. Plant phenolics and phenolic-enriched extracts as antimicrobial agents against food-contaminating microorganisms. Antioxidants. 2020;9:165. doi: 10.3390/antiox9020165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tombola F, Campello S, De Luca L, Ruggiero P, Del Giudice G, Papini E, Zoratti M. Plant polyphenol inhibit VacA, a toxin secreted by the gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori. FEBS Letters. 2003;543:184–189. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(03)00443-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsao R. Chemistry and biochemistry of dietary polyphenol. Nutrients. 2010;2:1231–1246. doi: 10.3390/nu2121231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuchiya H, Sato M, Miyazaki T, Fujiwara S, Tanigaki S, Ohyama M, Tanaka T, Iinuma M. Comparative study on the antibacterial activity of phytochemical flavanones against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 1996;50:27–34. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(96)85514-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang R, Zhang Y, Jia Y, Zhang M, Huang Y, Li C, Li K. Persimmon oligomeric proanthocyanidins exert antibacterial activity through damaging the cell membrane and disrupting the energy metabolism of Staphylococcus aureus. ACS Food Science & Technology. 2020;1:35–44. doi: 10.1021/acsfoodscitech.0c00021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao K, Zhang HJ, Xuan LJ, Zhang J, Xu YM, Bai DL. Stilbenoids: Chemistry and bioactivities. Studies in Natural Products Chemistry. 2008;34:453–646. doi: 10.1016/S1572-5995(08)80032-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Y, Chen J, Xiao A, Liu L. Antibacterial activity of polyphenols: Structure-activity relationship and influence of hyperglycemic condition. Molecules. 2017;22:1913. doi: 10.3390/molecules22111913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X, Zhou XD, Wu CD. The tea catechin epigallocatechin gallate suppresses cariogenic virulence factors of Streptococcus mutans. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 2011;55:1229–1236. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01016-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang NJ, Hinner MJ. Getting across the cell membrane: an overview for small molecules, peptides, and proteins. Methods in Molecular Biology. 2015;1266:29–53. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-2272-7_3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J, Xiao YY. Grape phytochemicals and associated health benefits. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition. 2013;53:1202–1225. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2012.692408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang XZ, Tang CP, Ye Y. Stilbenoids from Stemona japonica. Journal of Asian Natural Products Research. 2006;8:47–53. doi: 10.1080/10286020500382678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarin MA, Wan HY, Isha A, Armania N. Antioxidant, antibacterial and cytotoxic potential of condensed tannins from Leucaena leucocephala hybrid-Rendang. Food Science and Human Wellness. 2016;5:65–75. doi: 10.1016/j.fshw.2016.02.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Tsao R. Dietary polyphenol, oxidative stress and antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects. Current Opinion in Food Science. 2016;8:33–42. doi: 10.1016/j.cofs.2016.02.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang P, Cui W, Wang H, Du Y, Zhou Y. High-efficiency machine learning method for identifying foodborne disease outbreaks and confounding factors. foodborne pathogens and disease. Foodborne Pathogens and Disease. 2021;18:590–598. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2020.2913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao WH, Hu ZQ, Hara Y, Shimamura T. Inhibition of penicillinase by epigallocatechin gallate resulting in restoration of antibacterial activity of penicillin against penicillinase-producing Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 2002;46:2266–2268. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.7.2266-2268.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]