Abstract

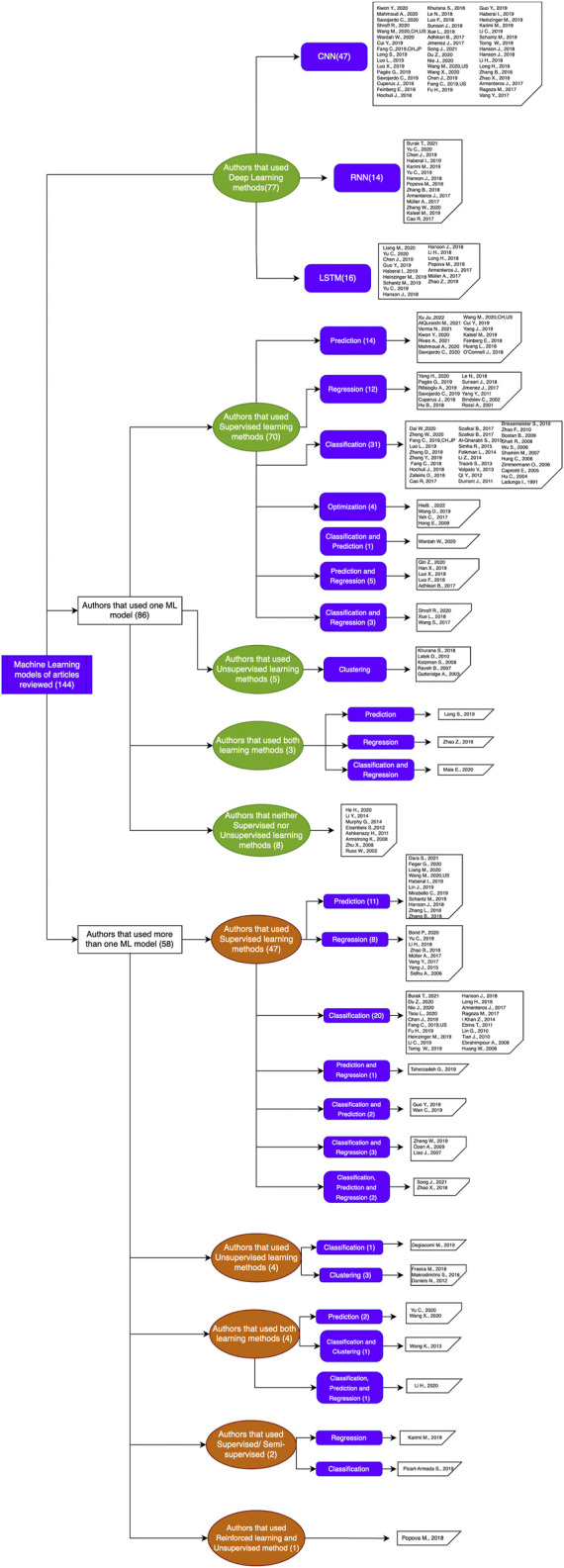

Proteins are some of the most fascinating and challenging molecules in the universe, and they pose a big challenge for artificial intelligence. The implementation of machine learning/AI in protein science gives rise to a world of knowledge adventures in the workhorse of the cell and proteome homeostasis, which are essential for making life possible. This opens up epistemic horizons thanks to a coupling of human tacit–explicit knowledge with machine learning power, the benefits of which are already tangible, such as important advances in protein structure prediction. Moreover, the driving force behind the protein processes of self-organization, adjustment, and fitness requires a space corresponding to gigabytes of life data in its order of magnitude. There are many tasks such as novel protein design, protein folding pathways, and synthetic metabolic routes, as well as protein-aggregation mechanisms, pathogenesis of protein misfolding and disease, and proteostasis networks that are currently unexplored or unrevealed. In this systematic review and biochemical meta-analysis, we aim to contribute to bridging the gap between what we call binomial artificial intelligence (AI) and protein science (PS), a growing research enterprise with exciting and promising biotechnological and biomedical applications. We undertake our task by exploring “the state of the art” in AI and machine learning (ML) applications to protein science in the scientific literature to address some critical research questions in this domain, including What kind of tasks are already explored by ML approaches to protein sciences? What are the most common ML algorithms and databases used? What is the situational diagnostic of the AI–PS inter-field? What do ML processing steps have in common? We also formulate novel questions such as Is it possible to discover what the rules of protein evolution are with the binomial AI–PS? How do protein folding pathways evolve? What are the rules that dictate the folds? What are the minimal nuclear protein structures? How do protein aggregates form and why do they exhibit different toxicities? What are the structural properties of amyloid proteins? How can we design an effective proteostasis network to deal with misfolded proteins? We are a cross-functional group of scientists from several academic disciplines, and we have conducted the systematic review using a variant of the PICO and PRISMA approaches. The search was carried out in four databases (PubMed, Bireme, OVID, and EBSCO Web of Science), resulting in 144 research articles. After three rounds of quality screening, 93 articles were finally selected for further analysis. A summary of our findings is as follows: regarding AI applications, there are mainly four types: 1) genomics, 2) protein structure and function, 3) protein design and evolution, and 4) drug design. In terms of the ML algorithms and databases used, supervised learning was the most common approach (85%). As for the databases used for the ML models, PDB and UniprotKB/Swissprot were the most common ones (21 and 8%, respectively). Moreover, we identified that approximately 63% of the articles organized their results into three steps, which we labeled pre-process, process, and post-process. A few studies combined data from several databases or created their own databases after the pre-process. Our main finding is that, as of today, there are no research road maps serving as guides to address gaps in our knowledge of the AI–PS binomial. All research efforts to collect, integrate multidimensional data features, and then analyze and validate them are, so far, uncoordinated and scattered throughout the scientific literature without a clear epistemic goal or connection between the studies. Therefore, our main contribution to the scientific literature is to offer a road map to help solve problems in drug design, protein structures, design, and function prediction while also presenting the “state of the art” on research in the AI–PS binomial until February 2021. Thus, we pave the way toward future advances in the synthetic redesign of novel proteins and protein networks and artificial metabolic pathways, learning lessons from nature for the welfare of humankind. Many of the novel proteins and metabolic pathways are currently non-existent in nature, nor are they used in the chemical industry or biomedical field.

Keywords: artificial intelligence, proteins, protein design and engineering, machine learning, deep learning, protein prediction, protein classification, drug design

Introduction

Protein science witnesses the most exciting and demanding revolution of its own field; the magnitude of its genetic–epigenetic—molecular networks, inhibitors, activators, modulators, and metabolite information—is astronomical. It is organized in an open “protein self-organize, adjustment and fitness space”; for example, a protein of 100 amino acids would contain 20100 variants, and a process of searching–finding conformations in a protein of 100 amino acids can adopt ∼1046 conformation and a unique native state, the protein data exceeding many petabytes (1 petabyte is 1 million gigabytes) (Kauffman, 1992).

Therefore, the use of artificial intelligence in protein science is creating new avenues for understanding the ways of organizing and classifying life within its organisms to eventually design, control, and improve this organization. In this respect, protein synthesis is a case in point. Indeed, the discovery of the underlying mechanism of protein synthesis is an inter-field discovery, that is, “a significant achievement of 20th century biology that integrated results from two fields: molecular biology and biochemistry” (Baetu, 2015). More recently, the field of protein science is, in turn, another inter-field enterprise, this time between molecular biology and computer science, or better said, between a cross-functional team of researchers (biochemists, protein scientists, protein engineers, system biology scientists, bioinformatics, between others). Nowadays, it is possible to classify, share, and use a significant number of structural biology databases helping researchers throughout the world. Once the mechanism of DNA for protein synthesis is deduced, it will then be possible to replicate it via computational strategies through artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) algorithms that can provide important information such as pattern recognition, nearest neighbors, vector profiles, back propagation, among others. AI has been used to exploit this novel knowledge to predict, design, classify, and evolve known proteins with improved and enhanced properties and applications in protein science (Paladino et al., 2017; Wardah et al., 2019;Cheng et al., 2008; Bernardes and Pedreira, 2013), which, in turn, makes its way to solve complex problems in the “fourth industrial revolution” and open new areas of protein research, growing at a very fast speed.

The techniques of machine learning are a subfield of AI, which has become popular due to the linear and non-linear processed data and the large amount of available combinatorial spaces. As a result, sophisticated algorithms have emerged, promoting the use of neural networks (Gainza et al., 2016) However, in spite of the large amount of research done in protein science, as far as we know, there are neither systematic reviews nor any biochemical meta-analysis in the scientific literature informing, illuminating, and guiding researchers on the best available ML techniques for particular tasks in protein science; albeit there have been recent reviews such as the work of AlQuraishi (2021), Dara et al. (2021), and Hie and Yang (2022), which prove that this inter-field is on evolution. By a biochemical meta-analysis, we mean an analysis resulting from two processes: identification and prediction. The former consists of identifying AI applications into the protein field where we classify and identify active and allosteric sites, molecular signatures, and molecular scaffolding not yet described in nature.

Each structural signature, pattern, or profile constitutes a singular part of the whole “lego-structure-kit” that is the protein space that includes the catalytic task space and shape space, which Kauffman (1992) defines as an abstract representation or mapping of all shapes and chemical reactions that can be catalyzed onto a space of task. The latter process is an analysis of the resulting predictions of structures, molecular signatures, regulatory sites, and ligand sites. Both processes are related to each other in the sense that the proteins in the identification process are searching targets of the 3D-structure for the prediction process that predicts the protein conformation multiple times from a template family or using model-free approach. The biochemical meta-analysis includes formulating the research question, searching and classifying protein tasks in the selected studies, gathering AI–PS information from the studies, evaluating the quality of the studies, analyzing and classifying the outcomes of studies, building up tables and figures for the interpretation of evidence, and presenting the results.

This study puts forward the use of ML classes and methods to address complex problems in protein science. Our point of departure is the state of the art of the AI–PS binomial; by binomial, we mean a biological name consisting of two terms that are partners in computational science as well as in biomedical or biotechnological science as a “two-feet principle” in order to understand, enhance, and control protein science development from an artificial intelligence perspective. Our cross-functional team aims at accelerating the steps of translating the basic scientific knowledge from protein science laboratories into AI applications. Here, we report a comprehensive, balanced systematic review for the literature in the inter-field and a biochemical meta-analysis, which includes a classification of screened articles: 1) by the ML techniques, they use and narrowing down the subareas, 2) by the classes, methods, algorithms, prediction type and programming language, 3) by some protein science queries, 4) by protein science applications, and 5) by protein science problems. Moreover, we present the main contributions of AI in several tasks, as well as a general outline of the processes that are carried out throughout the construction of the models and their applications. We outline a discussion on the best practices of validation, cross-validation, and individual control of testing ML models in order to assess the role that they play in the progress of ML techniques, integrating several data types and developing novel interpretations of computational methodology, thus enabling a wider range of protein’s-universe impacts. Finally, we provide future direction for machine learning approaches in the design of novel proteins, metabolic pathways, and synthetic redesign of protein networks.

Materials and Methods

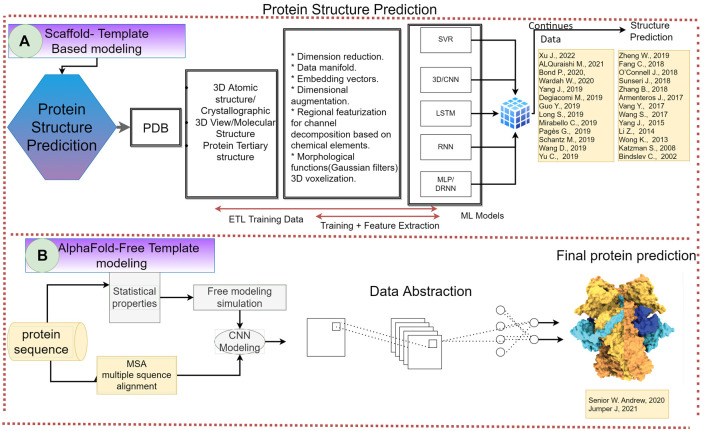

A systematic review of the scientific literature found in the period (until February 2021) was carried out for this study (Figures 1–3) following the PIO (participants/intervention/outcome) approach and according to PRISMA declaration (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) Supplementary. No ethical approval or letter of individual consent was required for this research.

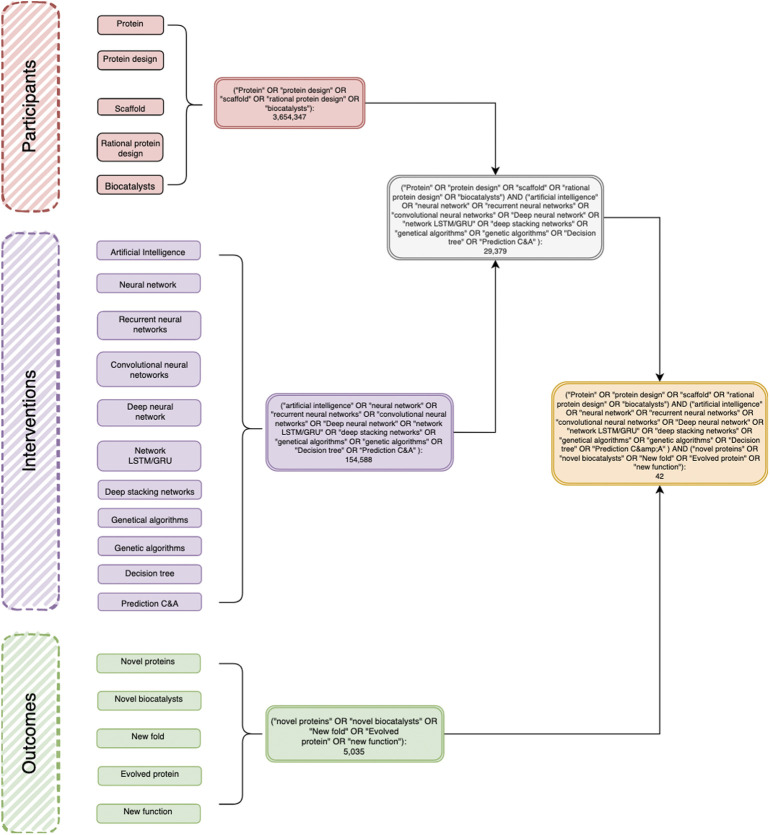

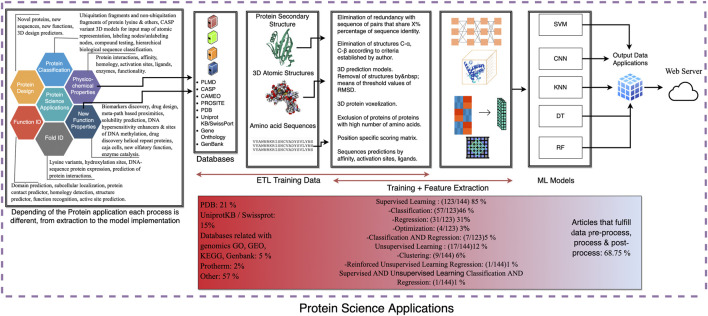

FIGURE 1.

A representative decision diagram showing the articles retrieved using the PIO strategy in the PubMed database. P (participants): Protein, Protein Design, Scaffold, Rational protein design, Biocatalysts. I (intervention): Networks: Neural networks, Recurrent neural networks, Networks LSTM/GRU, Convolutional neural network, Deep belief networks, Deep stacking networks C5.0; Genetic algorithms; Artificial intelligence; Decision trees; Classification; Prediction C&A; Software: Weka, RapidMiner, IBM Modeler; Programming Languages: Python, Java, OpenGL, C++ Shell; Development platform: Caffe Deep Learning, TensorFlow, IBM Distributed Deep Learning (DDL); Paradigm: Supervised Learning, Unsupervised learning, Reinforced learning, new function.

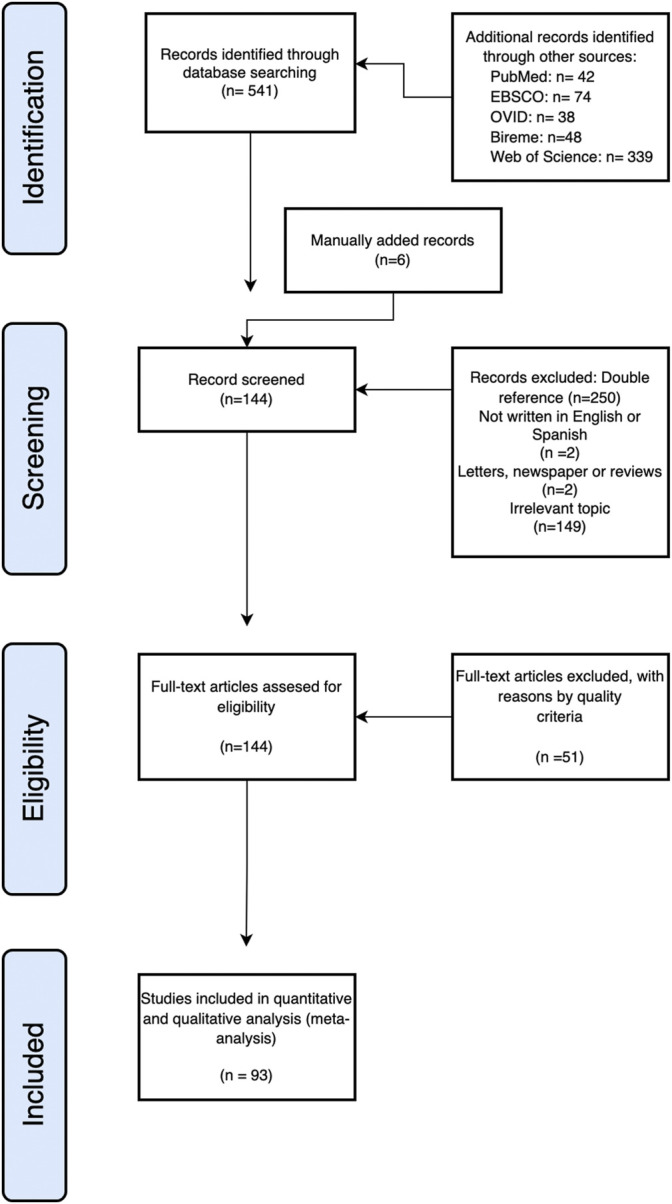

FIGURE 3.

Flowchart of the review process. A PRISMA flowchart of the systematic review on AI for protein sciences.

PIO Strategy

One of the main objectives is to discuss new information in the latest findings about the functions of AI in protein design. Furthermore, this review and meta-analysis intend to include a wide scope of the status of artificial intelligence in protein science. The PIO (participants, intervention, and outcome) strategy was used to systematically search all databases and was the methodology to address the following research questions: What is the state of art in the use of artificial intelligence in the protein science field? What is the use of neural networks in the rational design of proteins? Which neural networks are used in the rational design of proteins? Protein design is currently considered a challenge. As artificial intelligence makes progress, this is presented as a solution to various issues toward addressing how this new branch can be used for the creation of high precision models in protein design. Following the PIO strategy, the next terms were used for the research.

Participants: articles about proteins and their MeSH terms in general were considered for inclusion; we gave special consideration to protein design and their related terms such as scaffold (as a main structure or template), rational design, and biocatalysts (as a main task target for protein evolution and design in the chemical–biotechnological industry and biomedical field):

• protein

• protein design

• scaffold

• rational protein design

• biocatalysts

Intervention: studies with any types of algorithms, software, programming language, platform, or paradigm using alone or in combination were selected.

Types of algorithms:

• neural networks

• recurrent neural networks

• network LSTM/GRU

• convolutional neural network

• deep belief networks

• deep stacking networks C5.0

• genetic algorithms

• artificial intelligence

• decision trees

• classification

• prediction C&A

Software:

• Weka

• RapidMiner

• IBM Modeler

Programming languages:

• Python

• Java

• OpenGL

• C++

• Shell

Development platform:

• Caffe

• DeepLearning4j

• TensorFlow

• IBM distributed deep learning (DDL)

Paradigm:

• supervised learning

• unsupervised learning

• reinforced learning

Outcomes:

• novel proteins

• protein structure prediction

• novel biocatalysts

• new fold

• evolved protein

• new function

Databases and Searches

The electronic databases used were PubMed, Bireme, EBSCO, and OVID. The concepts with similarity were searched with “OR,” and within the groups of each element of the PIO research, they were searched with the word “AND.” Next, a diagram was constructed in order to show the history of searches and concepts used (figure tree diagram). This figure describes in full detail the searching strategy in the PubMed database as well as all keywords used. Moreover, it includes the number of resulting articles. Subsequently, the results obtained from these searches were recorded. The references themselves were then downloaded into the Mendeley database. All references were taken, organized, and saved in Mendeley, eliminating duplicates for the final result.

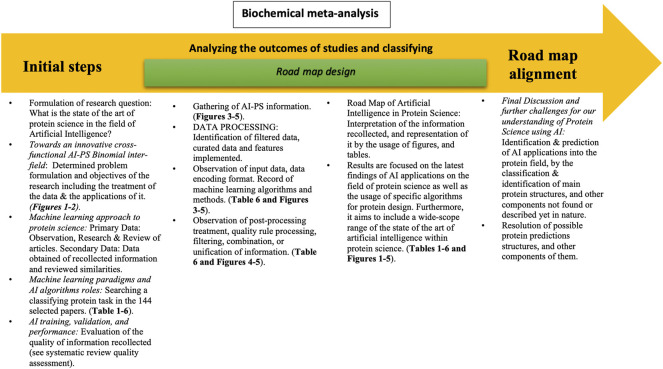

Biochemical Meta-analysis

The biochemical meta-analysis included formulating the research question, searching and classifying protein tasks in the 144 selected studies, gathering AI–PS information from the 144 studies, evaluating the quality of the studies (as described in the systematic review, see flowchart of PRISMA), analyzing and classifying the intervention and outcome of studies (networks, software, programming languages, development platforms, paradigms, novel proteins, novel scaffold, new fold, etc.), and building up tables and figures for the interpretation of evidence and presenting the results.

By a biochemical meta-analysis, we mean an analysis resulting from two processes: identification and prediction. The former consists of identifying AI applications into the protein field: classify and identify active and allosteric sites, molecular signatures, and molecular scaffolding not yet described in nature, each of which constitute a single part of a grand-type Lego structure. The latter is an analysis of resulting predictions: structures, molecular signatures, regulatory and ligand sites, etc.

Biochemical Meta-Analysis and Designing the Road Map

PRELIMINARY: we determined the formulation of the problem and objectives of the research within the figure, which includes the treatment of the data and their applications. Note: the information was acquired from a list of various databases from which data were analyzed.

DATA COLLECTION: primary data: observation, research and review of articles. Secondary data: data of the reviewed articles and information shared among keywords.

DATA PRE-PROCESSING (ETL and training): identification of filtered data, curated data, and features implemented; machine learning input relationship with protein science servers.

DATA PROCESSING (training data and feature extraction): observation of input data and data encoding format. Record of machine learning algorithms and methods. Recognition of key information for processing data within databases.

DATA POST-PROCESSING: observation of post-processing treatment, rule quality processing, filtering, combination, or unification of information.

MEASURE: explanation of the process, the values of different metrics for the quantification of magnitudes, and the contribution for the completion within the process of information.

ANALYZE: identify the application of machine learning algorithm in which the input of the dataset to process data format, training set, and 3D structures.

IMPROVE: determine the set to whom these new forms will be applied in models of the researched data and contribute to future implementations in protein science.

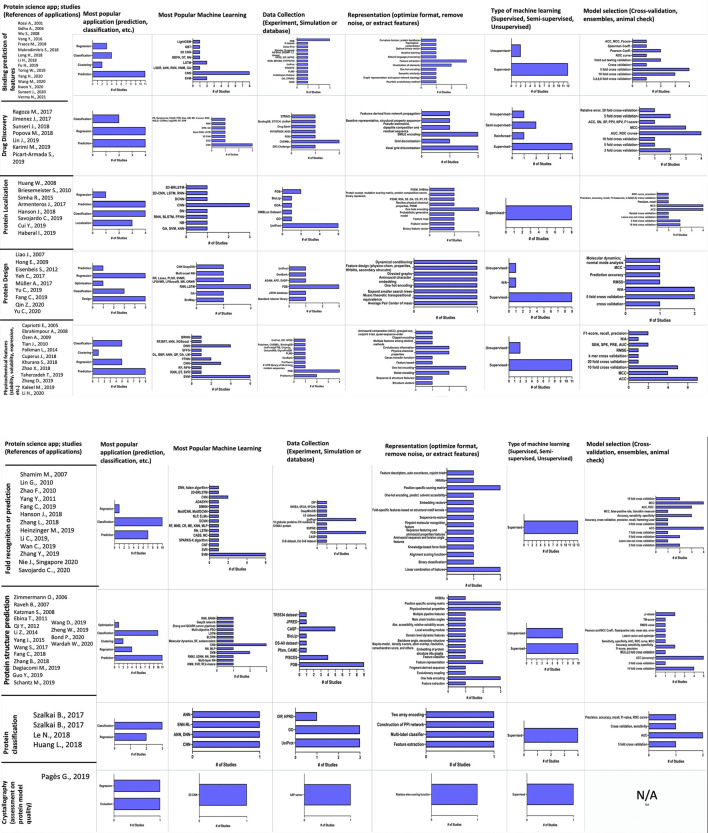

Concerning the computational aspects as to how articles were classified, three initial divisions were made and are displayed in Table 1: Pre-process, process, and post-process, each of which contain, in turn, the following items:

TABLE 1.

An overview of the included articles on study and algorithm features based in their characteristics, strengths, limitations, and measure of precision.

| Author/Year of Publication/Setting | Classes of machine learning | Methods | Algorithms | Protein Query | Characteristics | Strengths | Limitations | Validation and performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study characteristics and algorithm aspects | ||||||||

| Song J., 2021, China (Song et al., 2021) | Connectionist and Symbolist | An ensemble predictor with a deep convolutional neural network and LightGBM with ensemble learning algorithm | CNN, LightGBM | A sequence-based prediction method for protein–ATP-binding residues, including, PSSM, the predicted secondary structure, and one-hot encoding | The CNN frameworks are proposed as a multi-incepResNet-based predictor architecture and a multi-Xception-based predictor architecture. LightGBM, as a Gradient Boosting Decision Tree (GBDT) for classification and regression merged by an ensemble learning algorithm | The model enriches the protein–ATP-binding residue prediction ability using sequence information. Outstanding performance using ensemble learning algorithm in combination with a deep convolutional neural network and LightGBM as an ATP-binding tool | Distribution of the specific weights was calculated according to the ratio between the positive instances and the negative instances to solve the imbalance problem. The sensitivity prediction was only 0.189. This can be attributed by its very limited prediction coverage and the limited number of sequences in the training set | AUC (0.922 and 0.902), MCC (0.639 and 0.0642), and 5-fold cross-validation |

| Verma N., 2021, US (Verma et al., 2021) | Connectionist | A DNN framework (Ssnet), for the protein–ligand interaction prediction, which utilize the secondary structure of proteins extracted as a 1D representation based on the curvature and torsion of the protein backbone | DNN | Information about locations in a protein where a ligand can bind, including binding sites, allosteric sites, and cryptic sites, independently of the conformation | Curvature and torsion of protein backbone, feature vector for ligand. Multiple convolution networks with varying window sizes as branch convolution | The model does not show biases in the physicochemical properties and necessity of accurate 3D conformation while requiring significantly less computing time. Fast computation once the model is trained with weights bare fixed. No requirement of high-resolution structural data | Ssnet being blind to conformation limits its capability to account for mutations resulting from the same fold but significant difference in binding affinity. Ssnet should be treated as a tool to cull millions of drug-like molecules and not as an exact binding affinity prediction tool | AUC, ROC, and EF scores |

| Bond. S, 2020, US (Bond et al., 2020) | Connectionist | CCP4i2 Buccaneer automated model-building pipeline | PDB | Correctness of protein residues | Visual examination by the crystallographer. Coot provides validation tools to identify Ramachandran outliers, unusual rotamers, and other potential errors, as well as an interface to some tools from MolProbity | No cutoff has to be chosen | It may also have difficulties in that a residue built into the solvent 5 A° away from the structure is no different than one 10 A° away | COD for main chain 0.751; COD for side chain 0.613 |

| Kwon Y., 2020, Korea (Kwon et al., 2020) | Connectionist | A new neural network model for binding affinity prediction of a protein–ligand complex structure | 3D-CNN | Protein–protein complexes in a 3D structure | Ensemble of multiple independently trained networks that consist of multiple channels of 3D CNN layers. Protein–ligand complexes were represented as 3D grids voxelized binding pocket and ligand | Higher Pearson coefficient (0.827) than the state-of-the-art binding affinity prediction scoring functions. Accurate ranking of the relative binding affinities of possible multiple binders of a protein, comparable to the other scoring functions | For docking power, the Ak-score-single model is not as prominent as the other criteria models | Spearman and Pearson correlation coefficients |

| Li H., 2020, France, Hong Kong (Hongjian et al., 2021) | Connectionist, Symbolist and Analogist | Analyzed machine learning scoring functions for structure-based virtual screening | RF, BRT, kNN, NN, SVM, GBDT, multi-task DNN XGBoost | Comparison and review of machine learning scoring functions and classical scoring functions | Machine learning-based scoring function performs better than classical scoring functions, outperforming the average classical methods | Machine learning-based scoring function has introduced strong improvements over classical scoring functions, benchmarks for SBVS. | Current SBVS benchmarks do not actually mimic real test sets, and thus their ability to anticipate prospective performance is uncertain | N/A |

| Liang M., 2020, China (Liang and Nie, 2020) | Connectionist | Method that uses the relation between amino acids directly to predict enzyme function | RN, LSTM | State description matrix containing structural information by four parts, amino acid name (N), angles φ and ψ(A), relative distance (RD), and relative angle γ (RA) | A three-layer MLP; a four-layer MLP; a three-layer MLP, all with ReLU nonlinearities. The final layer was a linear layer that produced logits for optimization with a softmax loss function | Structural relationship information of amino acids and the relationship inference model can achieve good results in the protein functional classification | The model is currently only for single-label classification rather than multi-label classification and only predicts proteins approximately into six major classes. The training has a considerable time during the entire experiment; further optimization is necessary to improve performance | Accuracy, ROC curve, AUC, 3-fold cross-validation |

| Nie J., 2020, Singapore, Taiwan (Sua et al., 2020) | Probabilistic inference, symbolist, and analogist | Identification of lysine PTM site from a convolutional neural network and sequence graph transform techniques | RF, SVM, MNB, LR, Max Entropy, KNN, CNN, MLP | A computational technique to improve the identification of reaction sites for multiple lysine PTM sites in a protein sample | Improves the performance of identifying lysine PTM sites by using a novel combination with convolutional neural networks and sequence graph transform | As the current model that we are proposing is a multilabel model, it is very generalizable, especially when it comes to combinations of multilabel that the dataset does not have. In addition, such combinations of multilabel will increase the test sample size and provide a better idea of the accuracy of the model | Deep learning models are black-box models and may not be very useful for trying to understand the causes of PTMs and how to affect them. We gather that scientists would like to know the cause and effect in order to propose disease modification methods, rather than just pure identification of PTM’s | Cross-validation, precision accuracy, recall, Hamming-loss |

| Qin Z., 2020, US (Qin et al., 2020) | Connectionist | Learn method on amino acid sequence folds into a protein structure, along with the phi–psi angle information for high resolution of protein structure | MNNN | Prediction with only primary amino acid sequence without any template or co-evolutional information | Performs labeling of dihedral angles, combined with the sequence information, allowing the phi–psi angle prediction and building the atomic structure | Prediction consumes less than six orders of magnitude time. Prediction of the structure of an unknown protein is achieved, showing great advantage in the rational design of de novo proteins | Prediction accuracy can be further improved by incorporating new structure to refine the model | Prediction accuracy (85%) |

| Savojardo C., 2020, Italy (Savojardo et al., 2020a) | Connectionist | A method for protein subcellular localization prediction | DeepMITO, 1D-CNN | Performing proteome-wide prediction of sub-mitochondrial localization on representative proteomes | Its major characteristics is to combine proteome-wide experimental data with the predicted annotation of subcellular localization at submitochondrial level and complementary functional characterization in terms of biological processes and molecular functions. Evolutionary information, in the form of Position-Specific Scoring Matrices (PSSM) | The model allows users to search for proteins by organisms, mitochondrial compartment, biological process, or molecular function and to quickly retrieve and download results in different formats, including JSON and CSV | N/A | MCC coefficient |

| Wang M., 2020, US (Wang M. et al., 2020a) | Symbolist | A topology-based network tree, constructed by integrating the topological representation and NetTree for predicting protein–protein interaction (PPI) | TopNetTree, CNN, GBT | Protein structures, protein mutation, and mutation type | Convolutional Neural Networks, used in their Top Net Tree model, as a second module: consisting of the CNN-assisted GBT model | The proposed model achieved significantly better Rp than those of other existing methods, indicating that the topology-based machine learning methods have a better predictive power for PPI systems | Both GBTs and neural networks are quite sensitive to system errors of training of a model The ΔΔG of 27 non-binders (–8 kcal mol–1) did not follow the distribution of the whole dataset. | Person coefficient (Rp) = 0.65/0.68 and 10-fold cross-validation |

| Wardah W., 2020, Australia, Fiji, Japan, US (Wardah et al., 2020) | Pattern recognition | A convolutional neural network to identify the peptide-binding sites in proteins | CNN | Amino acid residues to create the image-like representations by feature vectors | Sets of convolution layers for image operations, followed by a pooling layer and a fully connected layer. The internal weights of the network were adjusted using the Adam optimizer. Bayesian optimization uses calculated values for configuring the model’s hyper-parameters based on prior observations | The model is able to predict a protein sequence with the highest sensitivity compared to any other tool | Improvement and especially in reducing the number of non-binding residues that get falsely classified as binding sites. Better feature engineering to produce better protein–peptide-binding site prediction results. More advanced computing environment | Sensitivity, specificity, AUC, ROC curve, and MCC coefficient |

| Yu C., 2020, Taiwan, US (Yu and Buehler, 2020) | Connectionist | A deep neural network model is based on translating protein sequences and structural information into a musical score, reflecting secondary structure information and information about the chain length and different protein molecules | RNN, LSTM | A vibrational spectrum of the amino acid, comprising amino acid sequence, fold geometry, or secondary structure | The RNN layers, Long Short-Term Memory Units are for time sequence features, alongside a dynamical conditioning. The attention dynamical conditioning model monitors the note velocity changes of the note sequences | The deep neural network is capable of training, classifying, and generating new protein sequences, reproducing existing sequences, and completely new sequences that do not exist yet. The model generates new proteins with an embedded secondary structure approach | The method could be extended to address folded structures of proteins by including more spatial information (relative distance of residuals, angles, or contact information). As well as the addition of combined optimization algorithms, like genetic algorithms | Molecular dynamics equilibration with normal mode analysis |

| Cui Y., 2019, China (Cui et al., 2019) | Pattern recognition | A deep learning model sequence-based for ab initio protein–ligand-binding residue prediction | DCNN | Protein sequences in order to construct several features for the input feature map | First representation, an amino acid sequence by m x d. First convolutional layer with k x d kernel size. Stage 1, with Plain(k x 1,2c) the same as for Block(k x 1,2c). Stage 2, with a Block(k x 1,2c) and Layer normalization-GLU-Conv block | The convolutional architecture provides the ability to process variable-length inputs. The hierarchical structure of the architecture enables us to capture long-distance dependencies between the residue and those that are precisely controlled. Augmentation of the training sets slightly improves the performance | The computational cost for training increases several times. Due to the considerable data skew, the training algorithm tends to fall into a local minimum where the network predicts all inputs as negative examples | Precision, Recall, MCC |

| Degiacomi M., 2019, UK (Degiacomi, 2019) | Deep machine learning | Conformational space generator | Molecular dynamics, random forests and autoencoder algorithms | Generative neural network trained on protein structures produced by molecular simulation can generate plausible conformations | Generative neural networks for the characterization of the conformational space of proteins featuring domain-level dynamics | The auto encoder does great at describing concerted motions (e.g., hinge motions) than at capturing subtle local fluctuations; it is most suitable to handle cases featuring domain-level rearrangements | This generative neural network model yet lies incapable of reproducing non-diversity-related cases, which is a subject of active research in the machine learning community | Performance assessed using different sizes of latent vector and optimizer |

| Fang C., 2019, China, Japan (Fang et al., 2019) | Connectionist | Protein sequence descriptor, position-specific scoring matrix, en DCNNMoRF | DCNN | Pinpoint molecular recognition features, which are key regions of intrinsically disordered proteins by machine learning methods | Ensemble deep convolutional neural network-based molecular recognition feature prediction. It does not incorporate any predicted features from other classifiers | The proposed method is highly performant for proteome-wide MoRF prediction without any protein category bias | It is yet difficult to predict if the new models will perform better only on the results, referring to the use of a new dataset. | Sensitivity, Specificity, Accuracy, AUC, ROC curve, MCC coefficient |

| Fang C., 2019, US (Fang et al., 2020) | Connectionist | Deep dense inception network for beta-turn prediction | DeepDIN | Protein sequence by creating four sets of features: physicochemical, HHBlits, predicted shape string and predicted eight-state secondary structure | Concatenate four convolved feature maps along the feature dimension. Feed the concatenated feature map into the stringed dense inception blocks. Dense layer, with Softmax function | Proposed process for beta-turn prediction outperforms the previous authors | Of the nine cases used, the amount of data belonging to each class may not produce a model with the ability to extract features or to be well generalized. Combined features improve prediction results than those features used alone | MCC and 5-fold cross-validation |

| Fu H., 2019, China (Fu et al., 2019) | Analogist | Classification Natural language prediction (NLP) task | CNN DL | Predict Lysine ubiquitination sites in large-scale | Input fragment. Multi-convolution-pooling layers. Fully connected layers | Extract features from the original protein fragments. First used in the prediction of ubiquitination | DeepUbi is not too deep. Only two convolution-pooling structures | 4-, 6-, 8-, and 10-fold cross-validation Sensitivity, Specificity, Acc, AUC, MCC, Acc >85% AUC = 0.9066/MCC= 0.78 |

| Guo Y., 2019, US (Guo et al., 2019) | Connectionist and Symbolist | Asymmetric Convolutional neural networks and bidirectional long short-term memory | ACNNs, BLSTM, DeepACLSTM | Sequence-based prediction for Protein Secondary Structure (P.S.S.) | The DeepACLSTM method is proposed to predict an 8-category PSS from protein sequence features and profile features | The method efficiently combines ACNN with BLSTM neural networks for the PPS prediction. Leveraging the feature vector dimension of the protein feature matrix | Expensive and time consuming | CB6133 0.742 CB513 0.705 |

| Haberal I., 2019, Norway, Turkey (Haberal and Ogul, 2019) | Connectionist | Three different deep learning architectures for prediction of metal-binding of Histidine (HIS) and Cysteine (CYS) amino acids | 2D CNN, LSTM, RNN | Three methods, PAM, ProCos, and BR to create the feature set from the frame vector; applying directly to raw protein sequences without any extensive feature engineering, while optimizing the model for predicting metal-binding site | The model is a 2D-CNN with four convolution layers, two pooling, two dropout, and two multi-layer perceptron layers. Each convolution layer has 3 × 3 pixel filters | The good performance of the model demonstrates the potential application for protein metal-binding site prediction. A competitive tool for future metal-binding studies, protein metal -interaction, protein secondary structure prediction, and protein function prediction. The CNN method provides better results for the prediction of protein metal binding using PAM attributes | The overall best results were obtained for a window of size 15. The lowest result was obtained in windows of size 101. The lowest result for the ProCos was obtained with the CNN model | Precision, Accuracy, Recall F-Measures K-fold (k = 3,5) cross-validation |

| Heinzinger M., 2019, Germany (Heinzinger et al., 2019) | Connectionist | Natural language processing with Deep learning | ELMo CharCNN LSTM | Protein function and structure prediction via analysis of unlabeled big data and deep learning processing | Novel representation of protein sequences as continuous vectors using language model ELMo, using NLP. | The approach improved over some popular methods using evolutionary information, and for some proteins even did beat the best. Thus, they prove to condense the underlying principles of protein sequences. Overall, the important novelty is speed | Although SeqVec embeddings generated the best predictions from single sequences, no solution improved over the best existing method using evolutionary information | Predictions of intrinsic disorder were evaluated through Matthew’s correlation coefficient and the False- Positive Rate. Also, the Gorodkin measure was used |

| Kaleel M., 2019, Ireland (Kaleel et al., 2019) | Connectionist and Symbolist | Deep neural network architecture composed of stacks of bidirectional recurrent neural networks and convolutional layers | RSA. | Three-dimensional structure of protein prediction | Predicting relative solvent accessibility (RSA) of amino acids within a protein is a significant step toward resolving the protein structure prediction challenge, especially in cases in which structural information about a protein is not available by homology transfer | High accuracy in four different classes (75% average). They performed all the training and testing in 5-fold cross-validation on a very large, state-of-the-art redundancy reduced set containing over 15,000 experimentally resolved proteins | The protein structure prediction challenge especially in cases in which structural information about a protein is not available by homology transfer | 2-class ACC 0.805 2-class F1 0.80 3-class ACC 0.664 3-class F1 0.66 4-class ACC 0.565 4-class F1 0.56 |

| Karimi M., 2019, US (Karimi et al., 2019) | Pattern recognition | Interpretable deep learning of compound–protein affinity | RNN–CNN models | Development of accurate deep learning models for predicting compound–protein affinity using only compound identities and protein sequences | Using only compound identities and protein sequences, and taking massive protein and compound data, RNN–CNN, and GCNN trained models outperform baseline models | Compared to conventional compound or protein representations using molecular descriptors or Pfam domains, the encoded representations learned from novel structurally annotated SPS sequences and SMILES strings improve both predictive power and training efficiency for various machine learning models | The resulting unified RNN/GCNN–CNN model did not improve against unified RNNCNN | Inferior relative error in IC50 within 5-fold for test cases and 20-fold for protein classes not included for training |

| Li C., 2019, China (Li and Liu, 2020) | Constrained optimization and Connectionist | Feature extractor techniques for protein-fold recognition | MotifCNN and MotifDCNN SVM CNN | Fold-specific features with biological attributes considering the evolutionary information from position-specific frequency matrices (PSFMs) considering the structure information from residue–residue | The predictor called MotifCNN-fold combines SVMs with the pairwise sequence similarity scores based on fold-specific features | The model incorporates the structural motifs into the CNNs, aiming to extract the more discriminative fold-specific features with biological attributes, considering the evolutionary information from PSFMs and the structure information from CCMs | Existing fold-specific features lack biological evidences and interpretability, the feature extraction method is still the bottleneck for the performance improvement of the machine learning-based methods | 2-fold cross-validation, Accuracy |

| Lin J., 2019, China (Lin et al., 2019) | Analogist and evolving structures | A drug target prediction method based on genetic algorithm and Bagging-SVM ensemble classifier | GA, SVM | Protein sequences by combining pseudo amino acid, dipeptide composition, and reduced sequence algorithms | GA is used to select the druggable protein dataset. The optimal feature vectors are for the SVM classifier. Bagging-SVM ensemble is for positive and negative sample sets | The method has a high reference value for the prediction of potential drug targets. An improvement over previous methods | N/A | Acc, MCC, Sn, Sp, AUC, PPV, NPV, F1-score,ROC curve and 5-fold cross-validation |

| Pagès G., 2019, France (Pagès et al., 2019) | Connectionist | Regression structure atomic depiction with a density function | 3D CNN | Protein model quality assessment | Three convolutional layers. Fully connected layers. Use of ELU as activation function | Competitivity with single-model protein model quality assessment. Trained to match CAD-score, on stage 2 of CASP 11 | Ornate does not reach the accuracy of the best meta-methods. Scoring time about 1 s for mid-size proteins | Network running using a GeForce GTX 680 GPU |

| Picart-Armada S., 2019, Belgium, UK, Spain (Picart-Armada et al., 2019) | Pattern recognition | Network propagation machine learning methods | PR, Random Randomraw EGAD, PPR, Raw, GM, MC, Z-scores, KNN, WSLD, COSNet, bagSVM, RF, SVM | Assess performance of several network propagation algorithms to find sensible gene targets for 22 common non-cancerous diseases | Two biological networks, six performance metrics, and compared two types of input gene-disease association scores. The impact of the design factors in performance was quantified through additive explanatory models | Network propagation seems effective for drug target discovery, reflecting the fact that drug targets tend to cluster within the network | Choice of the input network and the seed scores on the genes need careful consideration due to possibility of overestimation in performance indicators | There was a dramatic reduction in performance for most methods when using a complex-aware cross-validation strategy. Three cross-validation schemes were used |

| Savojardo C., 2019, Italy (Savojardo et al., 2020b) | Connectionist | A convolutional neural network architecture to extract relevant patterns from primary features | CNN | High prediction on discriminating four mitochondrial compartments (matrix, outer, inner, intermembrane) | Two pooling layers concatenated into a single vector with four independent output units with sigmoid activation function quantifying the membership of each considered mitochondrial compartment | Model has a robust approach with respect to class imbalance and accurate predictions for the four classification compartments | Adoption of more complex architecture, like recurrent layers can improve performance. However, the use of recurrent models leads to bad performance. Impossibility to predict multiple localization for a single protein sequence | 10-fold cross-validation, MCC from 0.45 to 0.65 |

| Schantz M., 2019, Argentina, Denmark, Malaysia (Klausen et al., 2019) | Connectionist | NetSurfP-2.0 | NetSurfP-2.0 | Predict local structural features of a protein from the primary sequence | A novel tool that can predict the most important local structural features with unprecedented accuracy and runtime. Is sequence-based and uses an architecture composed of convolutional and long short-term memory neural networks trained on solved protein structures. | Predicts solvent accessibility, secondary structure, structural disorder, and backbone dihedral angles for each residue of the input sequences | The models are presented with cases that are neither physically nor biologically meaningful | CASP12 0.726 TS115 0.778 CB513 0.794 |

| Taherzadeh G., 2019, Australia, US (Taherzadeh et al., 2019) | Constrained optimization and Connectionist | Predictor method of N- and mucin-type O-linked glycosylation sites in mammalian glycoproteins | DNN, SVM | An amino acid sequence binary vector, evolutionary information, physicochemical properties | DNN uses deep architectures of fully connected artificial neural networks. And SVM linear kernel for classification techniques to predict O-linked glycosylation sites | N-glycosylation model performs equally well for intra or cross-species datasets | Limitation to typical N-linked and mucin-type O-linked glycosylation sites due to lack of data for atypical N-linked and other types of O-linked glycosylation sites | AUC MCC, accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, ROC curve, 10-fold cross-validation |

| Torng W., 2019, US (Torng and Altman, 2019) | Analogist | Classification Softmax classifier for class probabilities | 3D CNN SVM | Protein functional site detection | Protein site representation as four atom channels and supervised labels | Achieved an average of 0.955 at a threshold of 0.99 on PROSITE families. Good performance where sequence motifs are absent, but a function is known | Loss of specific orientation data. NOS structures 1TLL and 1F20 and catalytic sites in TRYPSIN-like enzymes not detected | 5-fold cross-validation Precision, Recall Precision = 0.99 Recall = 0.955 |

| Wan C., 2019, UK (Wan et al., 2019) | Connectionist | A novel method (STRING2GO), with a deep maxout neural networks for protein functional predictive information | DMNN, SVM | Protein functional biological network node neighborhoods and co-occurrence function information | The network architecture consists of three fully connected hidden layers, followed by an output layer with as many neurons as the numbers of terms selected for the biological process functional domain. A sigmoid function is used as activation function and the AdaGrad optimizer is implemented | Successful learning of the functional representation classifiers for making predictions | Potential improvement of predictive accuracy by integrating representations from other data sources with the current PPI network embedding representations | AUC, ROC, MCC |

| Wang D., 2019, China (Wang D. et al., 2020) | Evolutionary | An Artificial Intelligence-based protein structure Refinement method | Multi-objective PSO | Query sequence structures as the initial particle selection for conformation representation | Use of multiple energy functions as multi-objectives. Initialization, energy map of the initial particles. Iteration, energy landscape of the 4th iteration. Selection of non-dominated solutions and added to the Pareto set. And selection of the global best position and the best position every swarm has had by the use of the dominance relationship of swarms, moving to the optimal direction | Success of AIR can be attributed to three main aspects: the first is the anisotropy of multiple templates. The complementarity of multi-objective energy functions and the swarm intelligence of the PSO algorithm, for effective search of good solutions. The larger number of iterations allows the algorithm to perform a more detailed search on the search space, which can improve the quality of the output models | Restriction of the velocity of the dihedral angles in each iteration to a reasonable range for balancing the accuracy and the searching conformation. There are still some unreasonable solutions in the Pareto set. The final step, which ranks the structures in Pareto set, needs more studies | RMSD value |

| Yu C., 2019, US (Yu et al., 2019) | Connectionist | Regression musical patterns by the extension of protein designed | RNN LSTM | Generation of audible sound from amino acid sequence for application on designer materials | An RNN utilized for melody generation. (LSTM) for time sequence featuring | Mechanism to explain the importance of protein sequences. 4.- It can be applied to express the structure of other nanostructures | N/A | N/A |

| Zhang D., 2019, US (Zhang and Kabuka, 2019) | Connectionist | Protein sequence pre-processing, unsupervised learning, supervised, and deep feature extraction | Multimodal DNN | Identify protein–protein interactions and classify families via deep learning models | Multi-modal deep representation learning structure by incorporating the protein physicochemical features with the graph topological features from the PPI networks | The model outperforms most of the baseline machine learning models analyzed by the authors, using the same reference datasets | If there is a certain type of PPI that previous models cannot handle, the article will not say if the new model can | PPI prediction accuracy for eight species ranged from 96.76 to 99.77%, which implies the multi-modal deep representation-learning framework achieves superior performance compared to other computational methods |

| Zhang Y., 2019, China (Zhang et al., 2019) | Connectionist | A new prediction approach appropriate for imbalanced DNA–protein-binding sites data | ADASYN | Employment of PSSM feature and sequence feature for predicting DNA-binding sites in proteins | Introduction of new feature representation approach by combining position-specific scoring matrix, one-hot encoding and predicted solvent accessibility features. Apply adaptive synthetic sampling to oversample the minority class and Bootstrap strategy for a majority class to deal with the imbalance problem | Demonstration that the method achieves a high prediction performance and outperforms the state-of-the-art sequence-based DNA–protein-binding site predictors | Consideration of some other physicochemical features to construct the model and try to explain the biological meaning of CNN filters | Sensitivity, Specificity, Accuracy, Precision, and MCC coefficient |

| Zheng W., 2019, US (Zheng et al., 2019) | Probabilistic inference, Symbolist | Two fully deep learning automated structure prediction pipelines for guided protein structure prediction | Zhang-Server and QUARK | Starting from a full-length query sequence structure | Three core modules: multiple sequence alignment (MSA) generation protocol to construct deep sequence-profiles for contact prediction; an improved meta- method, NeBcon, which combines multiple contact predictors, including ResPRE that predicts contact-maps by coupling precision-matrices with deep residual convolutional neural networks; an optimized contact potential to guide structure assembly simulations | Improvement of the accuracy of protein structure prediction for both FM and TBM targets. Accurate evolutionary coupling information for contact prediction, thus improving the performance of structure prediction. And properly balancing the components of the energy function was vital for accurate structure prediction | Incorrect prediction of contacts between the N- and C- terminal protein regions. Low accuracy of contact prediction in the Terminal regions due to MSAs with many gaps in these regions, as the accuracy of contact-map prediction and FM target modeling is highly influenced by the number of effective sequences in the MSA. | TM-score and p-values |

| Cuperus J., 2018, US (Cuperus et al., 2017) | Connectionist | Regression dropout probability distribution | DNN, CNN, LSTM | Predict protein expression | Hierarchical representation of image features from data | Prediction and visualization of transcription factor binding, Dnase I hypersensitivity sites, enhancers, and DNA methylation sites | Measurement of protein expression with yeast possessing only 5000 genes | k-mer feature, Cross-validation, Held-out R2 = 0.61 |

| Fang C.,US, 2018 (Fang et al., 2018) | Pattern recognition | A deep learning network architecture for both local and global interactions between amino acids for secondary structure prediction | Deep3I | A protein secondary structure prediction model | A designed feature matrix corresponding to the primary amino acid sequence of a protein, which consists of a rich set of information derived from individual amino acid, as well as the context of the protein sequence | This model uses a more sophisticated, yet efficient, deep learning architecture. The model utilizes hierarchical deep inception blocks to effectively process local and nonlocal interactions of residues | Further application of the model to predict other protein structure-related properties, such as backbone torsion angles, solvent accessibility, contact number, and protein order/disorder region, will be done in the future | Accuracy, p-value |

| Feinberg E., 2018, China, US (Feinberg et al., 2018) | Connectionist | A PotentialNet family of graph convolutions | GCNN | A generalized graph convolution to include intramolecular interactions and noncovalent interactions between different molecules | First: graph convolutions over only bonds, which derives new node feature maps. Second: entails both bond-based and spatial distance-based propagations of information. Third: a graph gather operation is conducted over the ligand atoms, whose feature maps are derived from bonded ligand information and spatial proximity to protein atoms | Statistically significant performance increases were observed for all three prediction tasks, electronic property (multitask), solubility (single task), and toxicity prediction (multitask). Spatial graph convolutions can learn an accurate mapping of protein−ligand structures to binding free energies using the same relatively low amount of data | Drawback to train−test split is possible overfitting to the test set through hyperparameter searching. Another limitation is that train and test sets will contain similar examples | Regression enrichment factor (EF), Pearson, and Spearman coefficient, R-squared, MUE (mean-unsigned error) |

| Frasca M., 2018, Italia (Frasca et al., 2018) | Analogist | Clustering Hopfield model | COSNet ParCOSNet HNN | AFP (Automated Protein Function Prediction) | Network parameters are learned to cope with the label imbalance | Advantage of the sparsity of input graphs and the scarcity of positive proteins in characterizing data in the AFP. | Time execution increased less than the density, and more than the number of nodes | 5-fold cross-validation Implementation and execution in a Nvidia GeForce GTX980 GPU target Precision, Recall, F-score, AUPRC |

| Hanson J., Australia, China, 2018 (Hanson et al., 2019) | Pattern recognition | A sequence-based prediction of one- dimensional structural properties of proteins | CNN, LSTM-BRNN | Improving the prediction of protein secondary structure, backbone angles, solvent accessibility | The model leverages an ensemble of LSTM-BRNN and ResNet models, together with predicted residue–residue contact maps, to continue the push toward the attainable limit of prediction for 3- and 8-state secondary structures, backbone angles (h, s, and w), half-sphere exposure, contact numbers and solvent accessible surface area (ASA) | The large improvement of fragment structural accuracy. A new method for predicting one-dimensional structural properties of proteins based on an ensemble of different types of neural networks (LSTM-BRNN, ResNet, and FC-NN) with predicted contact map input from SPOT-contact. The employment of an ensemble of different types of neural networks contributes another 0.5% improvement | Long proteins are also shown to take extensive time, especially for 2D analysis tools. The use of CPU and GPU is shown to not make a major difference in the time taken, as the speed increase introduced by GPU acceleration mainly comes during training | 10-fold cross-validation, Accuracy |

| Hanson J., Australia, China, 2018 (Hanson et al., 2018) | Connectionist | Method by stacking residual 2D-CNN with residual bidirectional recurrent LSTM networks, with 2D evolutionary coupling-based information | CNN, 2D-BRLSTM | Protein contact map prediction | Transformation of sequence-based 1D features into a 2D representation (outer concatenation function). ResNet, 2D-BRLSTM and FullyConnected (FC) | Method achieves a robust performance. The model is more accurate in contact prediction across different sequence separations, proteins with a different number of homologous sequences and residues with a different number of contacts | Coding limitation environment imposed by the 2D-BRLSTM model; training and testing input is limited to proteins of length 300 and 700 residues | AUC >0.95, ROC curve, precision |

| Huang L., 2018, US (Huang et al., 2008) | Connectionist | A novel PPI prediction method based on deep learning neural network and regularized Laplacian kernel | ENN-RL | Protein–protein interaction network | Contains five layers including the input layer, three hidden layers, and the output layer. Sigmoid is adopted as the activation function for each neuron, and layers are connected with dropouts. Regularized Laplacian kernel applied to the transition matrix built upon that evolved the PPI network | The transition matrix learned from our evolution neural network can also help build optimized kernel fusion, which effectively overcome the limitation of the traditional WOLP method that needs a relatively large and connected training network to obtain the optimal weights | The results show that our method can further improve the prediction performance by up to 2%, which is very close to an upper bound that is obtained by an approximate Bayesian computation-based sampling method | Cross-validation, AUC, sensitivity |

| Khurana S., 2018,Qatar, USA (Khurana et al., 2018) | Analogist | Clustering Natural language processing task | CNN FFNN | Solubility prediction | Use additional biological features from external feature extraction tool kits from the protein sequences | DeepSol is at least 3.5% more accurate than PaRSnIP and 15% than PROSO II. DeepSol is superior to all the current sequence-based protein solubility predictors | DeepSol S2 model was surpassed by PaRSnIP on sensitivity for soluble proteins | 10-fold cross-validation Acc, MCC 15% MCC = 0.55 3.5% DeepSol S1- 69 DeepSol S2- 69% |

| Le N., 2018, Taiwan (Le et al., 2018) | Analogist | Regression Softmax layer for classification | CNN | Classify Rab protein molecules | 2D-CNN and position-specific scoring matrices. PSSM profiles of 20 × 20 matrices | Construct a robust deep neural network for classifying each of four specific molecular functions. Powerful model for discovering new proteins that belong to Rab molecular functions | Consideration of the potential effects of more rigorous classification tests | 5-fold cross-validation Sensitivity, Specificity, Acc, AUC, F-score, MCC Acc = 99, 99.5, 96.3, 97.6% |

| Li H., 2018, China (Huang et al., 2018) | Constrained optimization | Regression Adam optimizer | DNN CNN LSTM | Prediction of protein interactions | Machine learning approach for computational methods for the prediction of PPIs | Insight into the identification of protein–protein interactions (PPIs) into protein functions | Manual input of features into the networks | Hold-out testing set model validation Acc, recall, precision, F-score, MCC Acc = 0.9878 Recall= 0.9891 Precision = 0.9861 F-score= 0.9876 MCC= 0.9757 |

| Long H., 2018, China, US (Long et al., 2018) | Connectionist | Classification sigmoid function | HDL CNN LSTM RNN | Predicting hydroxylation sites | CNN deep learning model. Convolution layer consists of a set of filters through dimensions of input data | p-values between AUCs of other methods are less than 0.000001 | Comparative results for CNN and iHyd-PseCp networks | 5-fold cross-validation Sn, Sp, Acc, MCC, TPR, FPR, Precision, recall |

| Makrodimitris S., 2018, Netherlands (Makrodimitris et al., 2019) | Analogist | Clustering constrained optimization | KNN LSDR | Protein function prediction | Transformation of the GO terms into a lower-dimensional space | GO-aware LSDR has slightly better performance on SDp. LSDR reduces the number of dimensions in the label-space. Improve power of the term-specific predictors | LSDR generates inconsistent parent–child pairs. GO-aware terms have a higher inconsistencies | 3-fold cross-validation Fp, AUPRCp, SDp, Ft, AUCRPCt |

| Popova M., 2018, Russia, US (Popova et al., 2018) | Constrained optimization | Regression Stack-RNN as a generative model | Stack-RNN LSTM. | De novo drug design | Deep neural network generative novel molecules (G) and predictive novel compounds (P) | The ReLeaSe method does not rely on predefined chemical descriptors No manual feature engineering for input representation | Extension of the system to afford multi-objective optimization of several target properties | 5-fold cross-validation (5CV) model trained using a GPU Acc R2, RMSE Acc R2 = 0.91 RMSE = 0.53 |

| Sunseri J., 2018, US (Sunseri et al., 2019) | Connectionist | Regression distributed atom densities | CNN | Cathepsin S model ligand protein | CNN based on scoring functions | CNN scoring function outperforms Vina on most tasks without manual intervention | Difficulties with Cathepsin S, for de novo docking | AUC, ROC, MCC |

| Zhang B., 2018, China (Zhang B. et al., 2018) | Connectionist | A novel deep learning architecture to improve synergy protein secondary structure prediction | CNN, RNN, BRNN | Four input features; position-specific scoring matrix, protein coding features, physical properties, characterization of protein sequence | A local block comprising two 1D convolutional networks with 100 kernels, and the concatenation of their outputs. BGRU block, the concatenation of input from the previous layer and before the previous layer is fed to the 1D convolutional filter. After reducing the dimensionality, the 500-dimensional data are transferred to the next BGRU layer | The CNN was successful at feature extraction, and the RNN was successful at sequence processing. The residual network connected the interval BGRU network to improve modeling long-range dependencies. When the staked layers were increased to two layers, the performance increased to 70.5%, and three-layer networks increased further to 71.4% accuracy | When the recurrent neural network was constructed by unidirectional GRU, the performance dropped to 67.2%. The unidirectional GRU network was ineffective at capturing contextual dependencies | Precision, Recall, F1-score, macro-F1, Accuracy |

| Zhang L., 2018, China (Zhang L. et al., 2018) | Connectionist | Two novel approaches that separately generate reliable noninteracting pairs, based on sequence similarity and on random walk in the PPI network | DNN, Adam algorithm | Use of auto-covariance descriptor to extract the features from amino acid sequences and deep neural networks to predict PPIs | The feature vectors of two individual proteins extracted by AC are employed as the inputs for these two DNNs, respectively. Adam algorithm is applied to speed up training. The dropout technique is employed to avoid overfitting. The ReLU activation function and cross-entropy loss are employed, since they can both accelerate the model training and obtain better prediction results | To reduce the bias and enhance the generalization ability of the generated negative dataset, these two strategies separately adjust the degree of the non-interacting proteins and approximate the degree to that of the positive dataset. | NIP-SS is competent on all datasets and hold a good performance, whereas NIP-RW can only obtain a good performance on small dataset (positive samples ≤6000) because of the restriction of random walk and the results of extensive experiments | Precision, Accuracy, Recall, Specificity, MCC coefficient, F1-score, AUC, Sensitivity |

| Zhao X., 2018, China (Zhao et al., 2018) | Connectionist | Bi-modal deep architecture with sub-nets handling two parts (raw protein sequence and physicochemical properties) | CNN and DNN | Raw sequence and physicochemical properties of protein for characterization of the acetylated fragments | Multi-layer 1D CNN for feature extractor and DNN with attention layer with a softmax layer | Capability of transfer learning for species-specific model, combining raw protein sequence and physicochemical information | Interpretation of biological aspect, overfitting problems on small-scale data | 10-fold cross-validation; ACC = 0.708, sensitivity (SEN) = 0.723, specificity (SPE) = 0.707, AUC = 0.783, MCC = 0.251 |

| Armenteros J., 2017, Denmark (Almagro Armenteros et al., 2017) | Analogist | Classification optimization | CNN RNN BLSTM FFNN Attention models | Predict protein subcellular localization | CNN extracts motif information using different motif sizes. Recurrent neural network scans the sequence in both directions | A-BLSTM and the CONV A-BLSTM models achieved the highest performance | Training time for the full ensemble was 80 h, approximately 5 h per model | Nested cross-validation and held-out set for testing models Gorodkin, Acc, MCC 72.90% 72.89% |

| Jimenez J., 2017, Spain (Jiménez et al., 2017) | Bayesian | Regression sigmoid activation function, depicting the probability | 3D CNN | Predict protein–ligand-binding sites Drug design | Fully connected networks. Hierarchical organized layers | Four convolutional layers with max pooling and dropout after every two convolutional layers, followed by one regular fully connected layer | Demand of significant computational resources than other methods for ligand-binding prediction | 10-fold cross-validation Using Nvidia GeForce GTX 1080 GPU for accelerated computing DCC, DVO AUC, ROC, Sn, SP, Precision, F1-score, MCC, Cohen’s Kappa coefficient |

| Müller A., 2017, Switzerland (Müller et al., 2018) | Analogist | Regression SoftMax function for temperature-controlled probability | RNN LSTM | Design of new peptide combinatorial de novo peptide design | The computed output y is compared to the actual amino acid to calculate the categorical cross-entropy loss | The network models were shown to generate peptide libraries of a desired size within the applicability domain of the model | Increasing the network size to more than two layers with 256 neurons led to rapid over-fitting of the training data distribution | 5-fold cross-validation Network training and generated sequences on a Nvidia GeForce GTX 1080 Ti GPU |

| Ragoza M., 2017, US (Ragoza et al., 2017) | Connectionist | Classification distributed atom densities | CNN SGD | Protein-ligand score for drug discovery | CNN architecture: construction using simple parameterization and serve as a starting point for optimization | On a per-target basis, CNN scoring outperforms Vina scoring for 90% of the DUD-E targets | CNN performance is worse at intra-target pose ranking, which is more relevant to molecular docking | 3-fold cross-validation ROC, AUC, FPR, TPR, RF-score, NNScore. CNN-0.815 Vina-0.645 |

| Szalkai B., 2017, Hungary (Szalkai and Grolmusz, 2018a) | Pattern recognition | A classification by amino acid sequence multi-label classification ability | ANN | Protein classification by amino acid sequence | The convolutional architecture with 1D spatial pyramid pooling and fully connected layers. The network has six one-dimensional convolution layers with kernel sizes [6,6,5,5,5,5] and depths (filter counts) [128,128,256,256, 512,512], with parametric rectified linear unit activation. Each max pooling layer was followed by a batch normalization layer | The model outperformed the existing solutions and have attained a near 100% of accuracy in multi-label, multi-family classification | Network variants without batch normalization and five (instead of six) layers showed a performance drop of several percentage points. With more GPU RAM available, one can further improve upon the performance of our neural network by simply increasing the number of convolutional or fully connected layers | Precision, Recall, F1-value, AUC, ROC curve |

| Szalkai B., 2017, Hungary (Szalkai and Grolmusz, 2018b) | Logical Inference | Classification Hierarchical classification tree | ANN | Hierarchical biological sequence classification | SECLAF implements a multi-label binary cross-entropy classification loss on the output neurons | SECLAF produces the most accurate artificial neural network for residue sequence classification to date | Preparation of the input data must be done by the user | AUC |

| Vang Y., 2017, US (Vang and Xie, 2017) | Analogist | Regression Distributed representation with NLP | CNN | HLA class I-peptide-binding prediction | The CNN architecture: convolutional and fully connected dense layers | Effective for validation, distribution, and representation for automatic encoding with no handcrafted encode construction | Provided sufficient data, the method is able to make prediction for any length peptides or allele subtype | 70% training set and 30% validation set (Hold-out) and 10-fold cross-validation GPU for faster computation of model SRCC, AUC SRCC = 0.521, 0.521, 0.513 AUC= 0.836, 0.819, 0.818 66.7% |

| Wang S., 2017, US (Wang et al., 2017) | Analogist | Classification Regression Regularization and optimization | UDNN RNN 2 | Prediction of Protein Contact Map | Consists of two major modules, each being a residual neural network | 3D models built from contact prediction have Tm score >0.5 for 208 of the 398 membrane proteins | No recognition of predict contact maps from PDB. | Algorithm runs on GPU card. Acc L/k (k= 10, 5, 2, 1) Long-range 47% CCMpred- 21% CASP11–30% |

| Yeh C., 2017, UK, US (Yeh et al., 2018) | Evolving structures | Optimization GA | GA multithreaded processing | Designed helical repeat proteins (DHRs) | Iterates through mutation, scoring, ranking, and selection | Aims to control the overall shape and size of a protein using existing blocks | First workload imbalance, less efficient work sharing and overheads in scheduling | RMSD value |

| Simha R., 2015, Canada, Germany, US (Simha et al., 2015) | Bayesian | Classification Probabilistic generative model Bayesian networks | MDLoc BN | Protein multi-location prediction | Each iteration of the learning process obtains a Bayesian network structure of locations using the software package BANJO. | Improvement of MDLoc over preliminary methods with Bayesian network classifiers | MDLoc’s precision values are lower than those of BNCs, MDLoc’s | 5-fold cross-validation Presi, Recsi, Acc, F1-scoresi |

| Yang J., 2015 China, US (Yang et al., 2015) | Analogist | Regression hierarchical order reduction | SVR | Structure prediction of cysteine-rich proteins | Position-specific scoring matrix (PSSM): each oxidized cysteine residue is represented as a vector of 20 elements | Cyscon improved the average accuracy of connectivity pattern prediction | Contact information must be predicted from sequence either by feature-based training or by correlated mutations | 10-fold cross-validation and 20-fold cross-validation QC, QP 21.9% |

| Folkman L., 2014, Australia (Folkman et al., 2014) | Bayesian Constrained optimization | Classification predicted probability of the mutation | SFFS SVM EASE-MM | Model designed for a specific type of mutation | Feature-based multiple models with each model designed for a specific type of mutations | EASE-MM archived balanced results for different types of mutations based on the accessible surface area, secondary structure, or magnitude of stability changes | Using an independent test set of 238 mutations, results were compared in with related work | 10-fold cross-validation ROC, AUC, MCC, Q2, Sn, Sp, PVV, NPV AUC = 0.82 MCC = 0.44 Q2 = 74.71 Sn = 73.14 Sp = 75.28 PVV = 52.30 NPV = 88.33 |

| Li Z., 2014, US (Li et al., 2014) | Bayesian | Classification Probability output prediction | SPIN NN | Sequence profile prediction | Sequence Profiles by Integrated Neural network based on fragment-derived Sequence profiles and structure-derived energy profiles | SPIN improves over the fragment-derived profile by 6.7% (from 23.6 to 30.3%) in sequence identity between predicted and raw sequences | Minor improvement in the core of proteins, which have 10% less hydrophilic residues in predicted sequences than raw sequences | 10-fold cross-validation MSE, Precision, Recovery rate |

| Eisenbeis S., 2012, Germany (Eisenbeis et al., 2012) | N/A | N/A | N/A | Enzyme design | No network | No network | No network | — |

| Qi Y., 2012, US (Qi et al., 2012) | Connectionist | Classification Back propagation in deep layers | DNN | Prediction of local properties in proteins | An amino acid feature extraction layer. A sequential feature extraction layer. A series of classical neural network layers | For the prediction of coiled coil regions, our performance of 97.4% beats the best result (94%) on the same dataset from using the same evaluation setup | The largest improvement is observed for relative solvent accessibility prediction, from 79.2 to 81.0% in the multitask setting | 3- and 10-fold cross-validation Acc, precision, recall, F1 80.3% |

| Ebina T., 2011, Japan (Ebina et al., 2011) | Analogist | Classification Domain linker prediction SVM | DROP SVM RF | Domain predictor | Vector encoding. Random Forest feature selection. SVM parameter optimization. Prediction assessment | Advantage for testing several averaging windows, 600 properties encoded, averaged with five different windows into a 3000-dimensional vector | Computational time required for performing an exhaustive search | 5-fold cross-validation AUC, Sn, Precision, NDO, AOS |

| Yang Y., 2011, US (Yang et al., 2011) | Probability Inference | Regression probabilistic-based matching | SPARKS-X Algorithm | Single-method fold recognition | The model is built by modeller9v7 using the alignment generated by SPARKS-X | SPAKRS-X performs significantly better in recognizing structurally similar proteins (3%) and in building better models (3%) | HHPRED improve 3% over SPARKS-X due to significantly more sophisticated model building techniques | ROC, TPR, FPR |

| Briesemeister S., 2010, Germany (Briesemeister et al., 2010) | Bayesian | Classification probabilistic approach | NB | Predict protein subcellular localization | Yloc, based on the simple naive Bayes classifier | Small number of features and the simple architecture guarantee interpretable predictions | Returns in confidence estimates that rate predictions are reliable or not | 5-fold cross-validation Acc, F1-score, precision, recall |

| Lin G., 2010, US (Lin et al., 2010) | Analogist | Classification Optimization | SVM SVR | Protein folding kinetic rate and real-value folding rate | SVM classifier to classify folding types based on binary kinetic mechanism (two-state or multi-state), instead of using structural classes of all-α-class, all-β-class and α/β-class | The accuracy of fold rate prediction is improved over previous sequence-based prediction methods | Performance can be further enhanced with additional information | Leave-one-out cross-validation (LOOCV) Classification accuracy surface, Predicted precision |

| Tian J., 2010, China (Tian et al., 2010) | Analogist | Classification Optimization | RFR SVM RF | Effect on single or multi-site mutation on protein thermostability | Random forest includes bootstrap re-sampling, random feature selection, in-depth decision, tree construction, and out-of-bag error estimates | Overall accuracy of classification and the Pearson correlation coefficient of regression were 79.2% and 0.72 | Direct comparison of Prethermut with the other published predictor was not performed as a result of data limitation and differences | 10-fold cross-validation Overall accuracy (Q2), MCC, Sn, Sp, Pearson correlation coefficient ® Acc = 79.2% r = 0.72 |

| Zhao F., 2010, US (Zhao et al., 2010) | Bayesian | Classification probabilistic graphical model | CNF SVM | Protein folding | Conformations of a residue in the protein backbone is described as a probabilistic distribution of (θ, τ) | The method generates conformations by restricting the local conformations of a protein | CNF can generate decoys with lower energy but not improve decoy quality | 5-, 7-, and 10-fold cross-validation Accuracy (Q3) Q3 = 80.1% |

| Hong E., 2009, US (Hong et al., 2009) | Symbolist | Classification Branch and bound tree Logical inference | BroMap | Tenth human fibronectin, D44.1 and DI.3 antibodies, Human erythropoietin | BroMAP attempts the reduction of the problem size within each node through DEE and elimination | Lower bounds are exploited in branching and subproblem selection for fast discovery of strong upper bounds | BroMAP is particularly applicable to large protein design problems where DEE/A∗ struggles and can also substitute for DEE/A∗ in general GMEC search | N/A |

| Özen A., 2009, Turkey (Özen et al., 2009) | Analogists | Classification Regression Constrained optimization | SVM KNN DT SVR | Single-site amino acid substitution | Early Integration. Intermediate Integration. Late Integration | Possible combination including new feature set, new kernel, or a learning method to improve accuracy. | Training any classifier with an unbalanced dataset in favor of negative instances makes it difficult to learn the positive instances | 20-fold cross-validation Acc, Error rate, Precision, Recall, FP rate Acc= 0.842, 0.835 |

| Ebrahimpour A., 2008, Malaysia [(Ebrahimpour et al., 2008) | Connectionist | Classification Back and batch back propagation | ANN FFNN IBP BBP QP GA LM | Lipase production Syncephalastrum racemosum, Pseudomonas sp. strain S5 and Pseudomonas aeruginosa | ANN architecture: input layer with six neurons, an output layer with one neuron, and a hidden layer. Transfer functions of hidden and output layers are iteratively determined | Maximum predicted values by ANN (0.47 Uml -1) and RSM (0.476 U–l - 1), whereas R2 and AAD were determined as 0.989 and 0.059% for ANN and 0.95 and 0.078% for RSM, respectively | ANN has the disadvantage of requiring large amounts of training data | RMSE, R2, AAD RMSE<0.0001 R2 = 0.9998 |

| Huang W., 2008, Taiwan (Huang et al., 2008) | Analogist | Clustering Combinatorial optimization | GA SVM KNN | Prediction method for predicting subcellular localization of novel proteins | Preparation of SVM, binary classifiers of LIBSVM. Sequence representation. Inclusion of essential GO terms | Bias-free estimation of the accuracy reduces computational cost | Computational demand is impractical for large datasets | 10-fold cross-validation and leave-one-out cross-validation (LOOCV) Accuracy, MCC Acc= 90.6–85.7% |

| Katzman S., 2008, US (Katzman et al., 2008) | Bayesian | Classification Probabilistic | MUSTER SVM | Local structure prediction | Calculation of output of each unit in each layer. Soft max function to all outputs of a given layer represents valid probability distribution | Accurate predictions of novel alphabets for extending the performance | Smaller windows and number of units, the network has fewer total degrees of freedom | 3-fold cross-validation, Qn |