Abstract

Introduction

Early intervention services for psychosis (EIS) are associated with improved clinical and economic outcomes. In Quebec, clinicians led the development of EIS from the late 1980s until 2017 when the provincial government announced EIS-specific funding, implementation support and provincial standards. This provides an interesting context to understand the impacts of policy commitments on EIS. Our primary objective was to describe the implementation of EIS three years after this increased political involvement.

Methods

This cross-sectional descriptive study was conducted in 2020 through a 161-question online survey, modeled after our team's earlier surveys, on the following themes: program characteristics, accessibility, program operations, clinical services, training/supervision, and quality assurance. Descriptive statistics were performed. When relevant, we compared data on programs founded before and after 2017.

Results

Twenty-eight of 33 existing EIS completed the survey. Between 2016 and 2020, the proportion of Quebec's population having access to EIS rose from 46% to 88%; >1,300 yearly admissions were reported by surveyed EIS, surpassing governments’ epidemiological estimates. Most programs set accessibility targets; adopted inclusive intake criteria and an open referral policy; engaged in education of referral sources. A wide range of biopsychosocial interventions and assertive outreach were offered by interdisciplinary teams. Administrative/organisational components were less widely implemented, such as clinical/administrative data collection, respecting recommended patient-to-case manager ratios and quality assurance.

Conclusion

Increased governmental implementation support including dedicated funding led to widespread implementation of good-quality, accessible EIS. Though some differences were found between programs founded before and after 2017, there was no overall discernible impact of year of implementation. Persisting challenges to collecting data may impede monitoring, data-informed decision-making, and quality improvement. Maintaining fidelity and meeting provincial standards may prove challenging as programs mature and adapt to their catchment area's specificities and as caseloads increase. Governmental incidence estimates may need recalculation considering recent epidemiological data.

Keywords: first episode psychosis, mental health services, psychosis, early intervention services, evidence based medicine, mental health policy

Abreǵe

Introduction

Les services d’intervention précoce (SIP) pour la psychose sont associés à de meilleurs résultats cliniques et économiques. Au Québec, les cliniciens ont dirigé le développement des SIP depuis la fin des années 1980 jusqu’en 2017, lorsque le gouvernement provincial a annoncé un financement spécifique aux SIP, du soutien pour la mise en œuvre et des normes provinciales. Cela constitue un contexte intéressant pour comprendre les effets des engagements politiques aux SIP. Notre objectif principal était de décrire la mise en œuvre des SIP trois ans après cette implication politique accrue.

Méthodes

La présente étude descriptive transversale a été menée en 2020 grâce à un sondage en ligne de 161 questions, modelé d’après les premiers sondages de notre équipe, sur les thèmes suivants : caractéristiques du programme, accessibilité, fonctionnement du programme, services cliniques, formation/supervision, et assurance de la qualité. Des statistiques descriptives ont été réalisées. Le cas échéant, nous avons comparé les données des programmes instaurés avant et après 2017.

Résultats

Vingt-huit sur 33 SIP existants ont répondu au sondage. Entre 2016 et 2020, la proportion de la population du Québec ayant accès aux SIP est passée de 46% à 88%; >1 300 admissions annuelles ont été déclarées par les SIP interrogés, surpassant les estimations épidémiologiques des gouvernements. La plupart des programmes ont établi des cibles d’accessibilité; adopté des critères d’admission inclusifs et une politique de référence ouverte; ils se sont engagés à l’éducation des sources de références. Une vaste gamme d’interventions biopsychosociales et d'interventions de proximité est offerte par des équipes interdisciplinaires. Les éléments administratifs/organisationnels ont été mis en œuvre à moins grande échelle, comme la collecte de données cliniques/administratives, le respect des ratios recommandées patient-intervenant pivot et l’assurance de la qualité.

Conclusion

Le soutien gouvernemental accru de la mise en œuvre, incluant le financement dédié, a mené à la mise en œuvre généralisée de SIP de bonne qualité et accessibles. Bien que des différences aient été observées entre les programmes fondés avant et après 2017, il n’y avait pas d’effet général discernable de l’année de mise en œuvre. Des difficultés persistantes pour la collecte de données peuvent entraver le suivi de la performance des SIP, la prise de décisions basée sur les données, et l’amélioration de la qualité. Maintenir la fidélité et satisfaire aux normes provinciales peut s’avérer difficile alors que les programmes évoluent et s’adaptent aux spécificités propres à leur territoire de desserte, et que le nombre de patients suivis augmente. Les estimations gouvernementale de l'incidence des premiers épisodes psychotiques pourraient devoir être recalculées au vu des données épidémiologiques récentes.

Early intervention services (EIS) for first-episode psychosis (FEP) yield superior clinical and functional outcomes compared to usual treatment. 1 However, variable adherence to standards across programs is a challenge to obtaining promised outcomes when implementing standardised healthcare models like EIS.2–4 While the availability of local guidelines alone is insufficient to ensure fidelity to core EIS components,2,5,6 mentoring and implementation guidance from peer experts and a community of practice, fidelity audits, and policy and financial support could promote fidelity.5–8

Despite lacking institutional and policy support, in 2016, Quebec's EIS offered high-quality services, while struggling with some administrative components. 7 In 2017, in line with recommendations from the Plan d’action en santé mentale 2015–2020, 9 Quebec's Ministry of Health and Social Services implemented four new measures: (1) commitment to developing EIS in every region, (2) additional recurring investments of $10 million/year dedicated to implementing and sustaining 15 new EIS, 10 (3) appointment of a specialist counsellor at the provincial Centre for Mental Health Excellence (CNESM), to support EIS implementation and quality improvement; and (4) publication of EIS standards, containing key performance indicators,11,12 the Cadre de référence : Programmes d’intervention pour premiers épisodes psychotiques 11 (the Cadre). The CNESM specialist counsellor's role is to develop and launch training programs for EIS professionals and to support programs with operational or organisational challenges. The counsellor offers onsite visits and helps develop program-specific interventions to address practice gaps.

Several institutional factors improve implementation outcomes in EIS and other mental health programs, such as dedicated funding,13–16 increased training and supervision, 17 institutional support and policy changes.5,6,17–19 Furthermore, newly created EIS can quickly reach adequate fidelity.20,21 Considering this, we expected policy changes implemented in Quebec to have a positive effect on EIS functioning. This study's main objective is to describe the state of implementation of EIS in Quebec three years after the government committed to improving quality and coverage of EIS. A secondary objective is to investigate differences between programs established before and after 2017.

Methods

A cross-sectional descriptive study was conducted via a web-based survey, adapted from a similar survey developed by the Canadian Consortium for Early Intervention in Psychosis. 8 Our team 7 had previously adapted this initial survey, based on national and international guidelines. The current survey also built on essential components of the First-Episode Psychosis Services Fidelity Scale (FEPS-FS) 22 and provincial standards. 11 It contained 161 open- and close-ended questions, with 107 follow-up questions about the following domains: program characteristics, accessibility, program operations, clinical services, training and supervision, research, and evaluation activities.

With support from the Association Québécoise des programmes pour premiers épisodes psychotiques (AQPPEP; a provincial association of EIS clinicians, peer support workers, researchers, and managers), program coordinators of all existing EIS (n = 33) were invited by email to complete the survey. Up to three reminders were sent, and respondents were contacted to clarify difficult-to-interpret data. The survey was launched February 2020 and programs were asked to complete it for the period up to February 2020 to avoid confounding by COVID-19 pandemic-related changes. Survey completion required approximately 2 hours. Telephonic assistance was offered to fill out the survey.

Data was analysed using descriptive statistics. Results were compared to performance indicators in the Cadre or thresholds proposed by FEPS-FS where the Cadre did not provide clear targets. 22 The FEPS-FS, which operationalised essential components of the model on a five-point scale, is among the most used fidelity tools and was recently revised to enable remote assessments. 23 It has been used and adapted in North America20,24 and Italy. 25 When relevant, data on programs founded before and after 2017 were compared.

This project received ethics approval from the Centre de recherche du Centre hospitalier de l’Université de Montréal and all programs agreed to data publication as reported in this paper.

Results

Twenty-eight (11 implemented after 2017) of the 33 invited EIS answered the survey completely, one small EIS declined to participate citing lack of time and four did not reply. The five non-respondent programs were non-urban sites implemented after 2017. Missing data accounted for <1%. Responses were provided by clinical team leaders (22/28) or lead psychiatrists (6/28). Three lead psychiatrists were also their program's director.

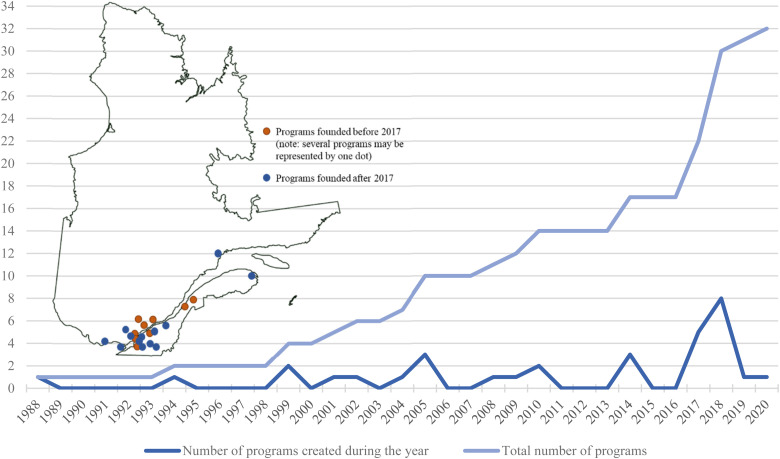

Figure 1 shows the number of EIS implemented and operating in Quebec yearly between 1988 and 2020. In 2020, approximately 2,700 young people were cared for by the 28 surveyed EIS, with around 1,340 yearly admissions. We estimate that 7.1 million inhabitants (84% of the province's population) reside in a catchment area covered by a surveyed EIS. 26 When including census data for regions covered by non-respondent EIS, 7.5 million inhabitants (88%) reside in areas offering EIS.

Figure 1.

Implementation of EIS in Quebec between 1988 and 2020.

Program Characteristics

Twenty-three services were standalone EIS; one was integrated within a flexible assertive community treatment (FACT) 27 team; another operated as an enhanced case management program,28,29 and three programs combined standalone EIS with FACT for delivery to remote parts of their catchment. FACT are interdisciplinary teams offering outreach and care of varying intensity levels for severe mental illnesses and flexibly integrate ACT and case management.27,30

Thirteen programs (6/13 founded before 2017) offered three-year follow-ups, as recommended by the Cadre. Twelve programs (9/12 founded before 2017; including 2 child-adolescent programs) offered services for more extended periods. Three EIS offer 2-year follow-ups. Of note, in our 2016 study, 5/17 programs offered a 3-year follow-up and 10/17 offered follow-up periods of ≥5 years or longer (see Supplemental Table 1). 7

While all EIS offered services for first-episode psychosis, 14 offered ultra-high risk for psychosis (UHR-P) services as recommended by the Cadre. Fewer programs founded before 2017 offered UHR-P compared to 2016. 7

Despite the recommendations of several guidelines, including the Cadre, 11 few programs engaged in quality assurance (6/28) and measured patient and treatment outcomes (8/28). Older programs were less involved in quality assurance compared to 2016, 7 though a similar proportion measured patient and treatment outcomes. 7 Only 10/28 (8/10 founded before 2017) and 14/28 (8/14 founded before 2017) programs maintained clinical and administrative databases, respectively.

Table 1 presents characteristics of the surveyed programs.

Table 1.

Program characteristics of EIS in Quebec in 2020

|

All programs

(total n = 28) |

Programs founded before 2017

(total n = 17) |

Programs founded from 2017 and onwards

(total n = 11) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Program characteristics | ||||

| Access to hospital beds | Youth-friendly unit, specific to EIS a | 1/28 | 1/17 | 0/11 |

| Regular unit in which EIS a patients are grouped, followed by EIS a psychiatrist | 3/28 | 2/17 | 1/11 | |

| Regular unit in which EIS a patients are grouped, followed by any inpatient psychiatrist | 3/28 | 3/17 | 0/11 | |

| Regular unit in which EIS a patients are not grouped, followed by EIS a psychiatrist | 7/28 | 3/17 | 4/11 | |

| Regular unit in which EIS a patients are not grouped, followed by any inpatient psychiatrist | 12/28 | 6/17 | 6/11 | |

| No access to hospital beds | 2/28 | 2/17 | 0/11 | |

| Accessibility and early detection targets | ||||

| Screening assessment | Maximum delay is set by program | 19/28 | 10/17 | 9/11 |

| Targeted maximum delay in days Median (range) |

3.0 (2-14) | 3.0 (2-14) | 3.0 (2-3) | |

| Psychiatric assessment | Maximum delay is set by program | 19/28 | 10/17 | 9/11 |

| Targeted maximum delay in days Median (range) |

14.0 (2-30) | 14.0 (2-30) | 14.0 (3-15) | |

| Time from referral to program entry | Maximum delay is set by program | 16/28 | 8/17 | 8/11 |

| Targeted maximum delay in days Median (range) |

14.0 (3-30) | 14.0 (3-30) | 7.0 (3-15) | |

| Early detection interventions | Public education | 4/28 | 4/17 | 0/11 |

| Referral sources education | 26/28 | 15/17 | 11/11 | |

| Admission criteria | ||||

| Lower age limit (excluding exclusive child and adolescent psychiatric programs) |

≤ 12 y.o. a | 14/25 | 6/14 | 8/11 |

| 14-17 y.o. a | 6/25 | 3/14 | 2/11 | |

| 18 y.o. a | 5/25 | 4/14 | 1/11 | |

| Higher age limit (excluding exclusive child and adolescent psychiatric programs) |

< 35 y.o. a | 7/25 | 7/14 | 0/11 |

| ≥ 35 y.o. a | 18/25 | 7/14 | 11/11 | |

| Services | ||||

| Targeted maximum length of follow-up in the program | 2 years | 3/28 | 2/17 | 1/11 |

| 3 years | 13/28 | 6/17 | 7/11 | |

| 4-5 years | 6/28 | 5/17 | 1/11 | |

| No maximum duration | 6/28 | 4/17 | 2/11 | |

| Services for UHR-P b | Formal UHR-P b clinic | 6/28 | 5/17 | 1/11 |

| Follow-up offered to UHR-P b patients without formal specific program | 8/28 | 6/17 | 2/11 | |

| Standardised care tools | Protocol for metabolic monitoring | 19/28 | 11/17 | 8/11 |

| Maximising engagement | ||||

| Discharge criteria | Maximum program duration completed | 22/28 | 13/17 | 9/11 |

| Remitted from positive symptoms (even if patient hasn't reached the maximum time allowed in the program) | 10/28 | 5/17 | 5/11 | |

| Patient ceased follow-up, felt better | 17/28 | 11/17 | 6/11 | |

| Patient refusal of treatment | 12/28 | 8/17 | 4/11 | |

| Noncompliance to pharmacological or nonpharmacological interventions | 0/28 | 0/17 | 0/11 | |

| Failure to keep appointments | 4/28 | 2/17 | 2/11 | |

| Others† | 10/28 | 7/17 | 3/11 | |

| Assertive outreach targeting patients who fail to keep appointments or are noncompliant to treatment | Yes | 28/28 | 17/17 | 11/11 |

| Program statistics | ||||

| Average length of follow-up in the program | 1-2 years | 15/28 | 7/17 | 8/11 |

| 3 years | 11/28 | 8/17 | 3/11 | |

| 4-5 years | 2/28 | 2/17 | 0/11 | |

| Average number of referrals per year (last 3 years) | Mean | 67.4 | 76.7 | 53.1 |

| Median (range) | 60 (2-200) | 60 (20-200) | 47 (2-130) | |

| Average number of admitted first-episode psychosis (FEP) patients per year (last 3 years) | Mean | 47.9 | 51.2 | 42.8 |

| Median (range) | 40 (2-150) | 40 (15-150) | 38 (2-80) | |

| Access to timely screening assessments | 80% of patients contacted within 72h of referral | 10/21 | 7/14 | 3/7 |

| Access to timely psychiatric evaluation | 80% of patients assessed within 2 weeks of referral | 16/24 | 9/15 | 7/9 |

| Average time from referral to program

entry (days) |

Mean | 10.5 | 12.6 | 7.3 |

| Median (range) | 7.5 (1-45) | 10.0 (2-45) | 7.0 (1-15) | |

| Proportion of time spent on outreach activities | 0-10% | 2/27 | 1/16 | 1/11 |

| 11-20% | 5/27 | 5/16 | 0/11 | |

| 21-30% | 3/27 | 3/16 | 0/11 | |

| 31-40% | 6/27 | 6/16 | 0/11 | |

| > 40% | 17/27 | 7/16 | 10/11 | |

| Patient to case manager ratios | < 15:1 | 7/26 | 5/15 | 2/11 |

| 15-19:1 | 11/26 | 4/15 | 7/11 | |

| 20:1-24:1 | 6/26 | 4/15 | 2/11 | |

| > 25:1 | 2/26 | 2/15 | 0/11 | |

Total n reported for individual outcomes may differ from the total number of programs, due to missing data (programs who did not answer the question or reported unavailable data).

: y.o.: Years old

: UHR-P: Ultra-high risk for psychosis

†: Other discharge criteria included patients wrongly admitted to the EIS (n = 1/10), patients whose needs are better fulfilled by other mental health services (n = 3/10; e.g., assertive community treatment), patients who moved outside the catchment area (n = 1/10) or whose whereabouts are untraceable (n = 1/10), and patients who completed their recovery goals (n = 1/10). The 3 child and adolescent psychiatry programs noted that reaching age 18 was a discharge criterion.

Early Identification, Program Accessibility, and Patient Engagement

To promote early detection, the Cadre recommends that programs conduct public education activities every three years; only 4 programs (all founded before 2017) do so, compared to 8/15 in 2016. 7 The majority (26/28) of programs provided targeted education to referral sources (e.g., family doctors) as the Cadre recommends.

The Cadre and several guidelines propose that individuals aged 12–35 years suffering from any psychotic disorder should be admitted if they have received less than one year of prior treatment, except psychoses secondary to medical conditions.4,12,31–36 Accordingly, all programs accepted a range of psychotic disorders, generally including affective disorders (26/28) and substance-induced psychosis (25/28), an increase from 2016. 7 Three programs were run by child and adolescent psychiatry and served only individuals younger than 17/18 years (see Table 1 for age ranges). Most programs denied using any exclusion criteria as proscribed by the Cadre.

The Cadre recommends that programs adopt an open referral policy and sets maximum delays for screening (72 h) and psychiatric assessments (2 weeks) after referral. Such targets were most commonly implemented in recently founded programs, while the proportion of older programs using them slightly declined compared to 2016. 7

Most programs accept self-referrals and referrals from family/friends, community organisations, educational institutions, and community healthcare clinics, though their use remains uncommon (see Supplemental Table 2).

Although 13 programs reported that <10% of their patients disengaged before completing the recommended follow-up duration, treatment disengagement remains an issue, 37 reflected by 6/23 programs reporting dropout rates between 20–40%.

Biopsychosocial Interventions

The Cadre suggests reviewing recovery plans every 6 months for at least 90% of patients. Twenty-seven programs reported devising such plans (≤6-month revisions: 26/27).

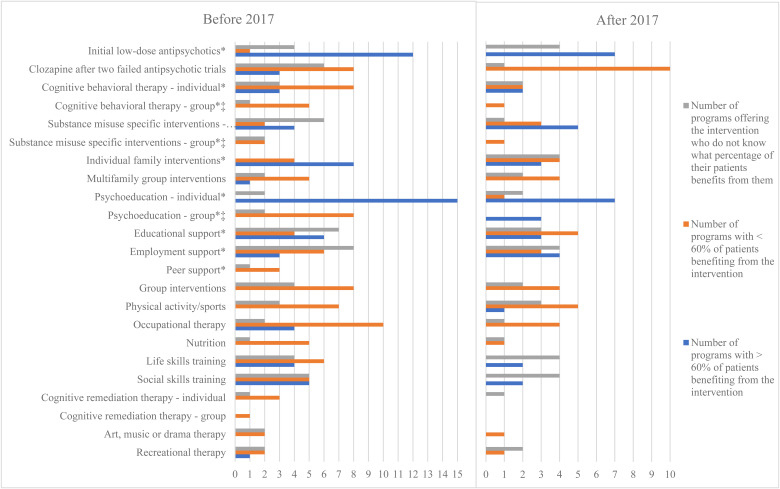

The Cadre recommends that all patients be offered the following core interventions: medication, cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), family interventions, family support and education, supported employment and education, outreach, and specific and integrated substance use interventions. The FEPS-FS 22 states that EIS must offer interventions >60% of patients to meet the fidelity threshold. Figure 2 shows the array of biopsychosocial interventions offered by programs. Between 2016 7 and 2020, older programs improved their implementation of employment and educational support interventions.

Figure 2.

Psychosocial interventions offered by quebec EIS in 2020.

*Interventions recommended by the Cadre, which does not specify if the interventions should be offered in individual or group format. †For each intervention, a certain proportion of programs reported unavailable data or not knowing how many patients benefited from said intervention. ‡All services offering group interventions for substance misuse also offer individual interventions. Among programs offering group cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), only one does not offer individual CBT.

According to the Cadre, case management should be offered to all patients with patient-to-case manager ratios <16:1. Other guidelines suggest varying ratios (10:1–20:1).4,32,35,38,39 Twenty-six of 28 programs offered case management (offered to all patients: 25/26); more older programs offered it compared to 2016. 7 Patient-to-case manager ratios varied greatly; 6/8 programs with ratios >20:1 were founded before 2017.

Outreach included varied activities for almost all programs and 17 programs (10/17 founded after 2017) reported spending >40% of their time on outreach and holding >40% of patient consultations outside the office, meeting the highest FEPS-FS standards. Programs founded before 2017 slightly increased their outreach efforts compared to 2016. 7

Most programs did not use standardised clinical tools to measure outcomes, with the exceptions of substance use scales (11/27) and metabolic monitoring protocols (19/28).

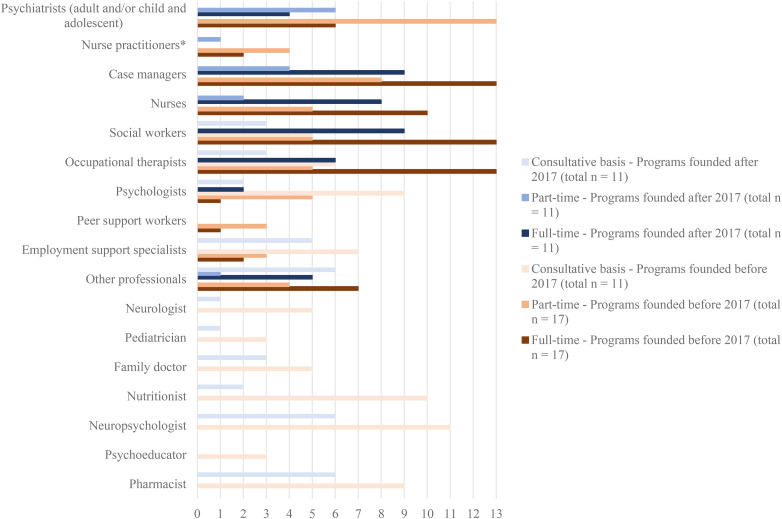

Team Composition

The Cadre specifies the required composition of EIS interdisciplinary teams. Figure 3 depicts mental healthcare professionals working in the EIS.

Figure 3.

Access to mental healthcare professionals within the EIS or for consultations, if not within EIS.

Two recent programs reported not having psychiatrists within the EIS. Specialists in core psychosocial interventions required by the Cadre were unevenly accessible: CBT (19/28), family interventions (21/28), supported employment (14/28), and substance use interventions (16/28). Two programs were devoid of specialists. In most cases, professionals had received specific training to be considered specialists.

Several guidelines4,12,32 and the FEPS-FS recommend weekly meetings of all team members to facilitate collaboration and continuity of care, a standard met by 26/27 programs.

Training and Continuing Education

To ensure quality of care, continuous education, training, and supervision should be accessible to EIS staff.4,32,35,38–40 Most programs (24/27) engaged in continuing education, commonly Among older programs, 13/17 engaged in continuing education (2016: 11/15). 7 An average of 86% (median: 100%; range 15–100) of all EIS staff had participated in continuing education in the last year. Supervision for case management and biopsychosocial interventions was available for 17/27 programs. Most programs reported that their members had accessed training on the EIS model (26/27), psychosocial interventions (23/27), and case management (13/27). Nearly half the programs (13/27) reported that training needs were met, and most (24/27) rated training opportunities in Quebec as moderate/excellent.

Discussion

Rapid High-fidelity Implementation Is Feasible With Adequate Political Support

The Plan d’action en santé mentale 2015–2020 9 required all Quebec regional health services to implement EIS. This, along with the funding commitment made in 2017, spurred the development of 16 additional EIS (11 were surveyed) within three years. In contrast, it had taken 25 years to implement 17 programs before 2017. Recently created programs have been implemented rapidly with clear mandates based on provincial standards and financial support, which possibly explains why they were able to quickly begin offering high-quality services, comparable to older programs. With 13/16 new EIS in non-academic centres, Quebec's recent large-scale implementation effort has extended the reach of EIS beyond university hospitals.

Whereas 46% of Quebec's population had access to EIS in 2016, 7 that estimate rose to 88% in 2020. However, in some regions, EIS cover large territories (13/25 covering >250 km2) which challenges accessibility for remote populations. This is a source of concern, as it has been shown in Ontario that individuals with FEP living in areas served by an EIS do not necessarily access it. 41

Numerous high-quality EIS can be rapidly implemented across a variety of regions with their own context-specific challenges. In Quebec, this was facilitated by adequate governmental support: policy changes, local guidelines, dedicated funding, and real-time implementation support from a dedicated clinical specialist. As previously demonstrated, the use of the provincial standards by older and newer programs alike suggests that local guidelines and standards may enjoy greater uptake and can improve adherence to essential components of EIS. 6

Implementation Support Improves Service Access and Quality

Overall, in line with the Cadre's recommendations, Quebec programs report offering good-quality clinical services to youth with FEP. Most programs adopt an open referral policy and inclusive admission criteria, with broader inclusions compared to 2016, suggesting that implementation of national guidelines can immediately impact programs’ admission criteria, addressing a challenge that had been reported in the 2016 survey. 7

Most programs adhere to the age range suggested by the Cadre, with programs implemented after 2017 reporting greater fidelity than older programs and providing continuity of care at the transition between adolescence and young adulthood, when the risk of service disengagement is higher.42,43 Alternatively, some programs achieved continuity of care across the 12–35 age range by partnering or merging with an adult EIS in the same catchment. No international consensus exists on the optimal age range for EIS. While Quebec's Cadre focuses on youth-friendly EIS, UK guidelines recommend EIS for 14–65 year olds. 31

Despite not always establishing formal targets, most programs reported a mean delay between referral and program entry of ≤2 weeks. Although these reports of timely access are reassuring, the absence of targets and their monitoring suggests that these results could be lost in the future. This is worrisome since increased treatment delays, and thereby DUP, can negatively impact outcomes. 44

Most programs conducted a variety of outreach activities. Almost all programs founded after 2017 met the highest FEPS-FS standards for assertive outreach, compared to <50% of older programs (despite increased uptake of outreach compared to 2016). 7 Higher patient-to-case-manager ratios and greater accessibility of urban (mostly older) programs may explain this difference. Newer programs, mostly non-urban, may be more reliant on outreach to reach their patients effectively. In general, telehealth could enhance engagement 45 among patients living in remote areas or those less likely to seek help in institutional locations.

Most programs conducted educational activities targeted at referral sources to promote early detection, a practice known to shorten DUP,46,47 improving clinical and functional outcomes.48,49 However, fewer programs held any public education activities compared to 2016, 7 which may be seen as time-consuming and resource-intensive. These could possibly be best developed and deployed by province-wide organisations (e.g., AQPPEP 50 ) and the government for wider reach, uniformity of messaging and cost-effectiveness.

Following the Cadre's standards, most programs reported follow-ups of at least 3 years during which they offered a variety of psychosocial interventions. Our previous study 7 found that Quebec EIS, especially smaller programs, struggled to offer diverse interventions. Our current findings suggest a significant improvement in this regard, with more older programs now offering educational and employment support. 7 This further highlights the impact of local standards and continuous implementation support. Nevertheless, echoing an Ontarian study 24 several programs reported that inadequate staffing or the lack of specialists limited the availability of varied interventions.

Though regular supervision and mentoring for psychosocial interventions, including case management, an essential component,21,51,52 was unavailable to >1/3 of programs, training and continuing education seemed to be widely available, which is an improvement compared to 2016. These opportunities were provided mainly through the AQPPEP, the CNESM, and the francophone branch of IEPA. 53

Almost all surveyed EIS reported having weekly team meetings, an organisational process that promotes care continuity and peer mentoring/consultation and allows the discussion of difficult/emergent situations.

Challenges Remain

Although several recently implemented programs (7/11) received dedicated funding to hire non-psychiatrist clinical staff, many older programs had not yet received additional funding to adapt to the Cadre's standards. To address staffing problems, in December 2020, 54 the health ministry announced an additional recurring investment of $10 million for EIS implementation.

Across programs, data collection and the use of measures pose challenges. This is particularly true for recently implemented programs, which may have prioritised organising services over data collection. While understandable, there is value in integrating measurement into care from the outset.

Measurement-based care can improve treatment decision-making and thereby patient outcomes. 55 The lack of data may result in erroneous impressions regarding actual practices and impede quality assurance and fidelity monitoring. For instance, most programs reported lower disengagement rates than in the literature, 56 suggesting a possible under-estimation. Therefore, EIS must be trained and supported in integrating routine measurement and data collection on key performance indicators, which should be made a standard. Further efforts are needed to amplify the importance of monitoring and reverse the worrying trend noted among older EIS to disengage from quality assurance activities. 7 Finally, although the Cadre describes the need for a common body to coordinate data collection for key indicators across EIS, this process has still not been implemented.

Our findings point to gaps between protocols and practice. EIS guidelines recommend that all programs have an open referral policy, however, formal referral pathways remain pervasive. EIS guidelines, which all programs claimed to follow, clearly proscribe treatment refusal as a reason for discharge and emphasise the need for treatment throughout the critical 2–5 year period following psychosis onset, to ensure the sustainment of remission and improved functional outcomes. 57 Yet, several programs reported prematurely discharging patients due to treatment refusal (increase since 2016 7 ) or once they reached symptomatic remission before the recommended follow-up duration.

Despite reductions in treatment delays compared to 2016, 7 setting targeted maximum delays for initial contact and assessment remains challenging for some EIS. Timely access should be urgently prioritised as it is crucial to reducing DUP, a fundamental EIS principle.

Inpatient care, a frequent portal to entry into care, can be traumatic. 58 Without the developmentally-appropriate and hope-inspiring EIS philosophy, it may negatively shape youths’ attitudes towards mental health service engagement. Thus, EIS should have access to youth-friendly hospitalisation wards and promote care continuity between inpatient and outpatient services. Only one program has a EIS-specific inpatient service. For care continuity, ten programs had the same psychiatrist for inpatient (regular wards) and outpatient services. However, in 12/25 programs, FEP patients were neither grouped together nor followed by the EIS team.

Although almost all programs offer case management (an improvement since 2016 7 ), EIS still struggle to maintain recommended patient-to-case manager ratios, similarly to Ontario, 17 although case management is an EIS pillar.

The high workload, resulting from insufficient staffing, may increase staff fatigue and turnover, and affect implementation quality.14–16,19,59 These high ratios could result from extensive early detection efforts in previous years for older programs, however, newer programs might not yet reach all FEP cases in their catchment area. Current admission rates of the 28 surveyed EIS (1,340 patients/year) already exceed predicted incidence rates for Quebec (1,080). EIS funding and staffing was established based on an assumed homogenous incidence of 45 new cases per 100,000 people aged 12–35 years. 11 However, there is strong evidence for variations in incidence rates based on urbanicity60,61; proportion of immigrants/newcomers, 62 homelessness, 63 and high-potency cannabis availability. 64 Unfortunately, high-quality psychosis incidence data is still lacking. Estimates must be revised based on simulations informed by epidemiological evidence, to ensure adequate staffing and funding. 65 Furthermore, waiting lists in adult mental health services and complex transfer processes for patients who have completed EIS follow-up also increase caseloads. This underscores the importance of streamlined pathways of care upstream and downstream of EIS.

Although most guidelines recommend UHR-P services, only a few older programs offered them; a decline in UHR-P services is noted compared to 2016. 7 This may result from the Cadre's recommendation to develop such services once FEP interventions are fully implemented and from lack of consensus on whether these patients are better served in integrated youth mental health services, which may help avoid the stigma associated with psychosis. 66

Limitations

Program directors answered the survey, and responses may therefore reflect desirability bias. However, all respondents were aware that results would be presented aggregately, that data were protected as required by the ethics committee, and that these standards would be upheld if the data were to be shared with the government. Thus, the risk of programs offering an overly positive perspective to justify government funding is minimal. Moreover, with at least half the programs lacking clinical and/or administrative databases, some reported data may not be accurate. As discussed previously, this troubling finding affects the validity of quality assurance and fidelity monitoring efforts, including this study. Furthermore, patient and carer perspectives were not included. While some surveyed EIS were in early phases of implementation, including all programs (irrespective of implementation stage) allowed us to build a comprehensive portrait of EIS implementation in Quebec. Of note, most non-respondents were smaller programs in early phases of implementation.

Conclusion

Our study provides naturalistic evidence that government involvement and dedicated funding positively influence the implementation of EIS.5,14,18,67,68 It confirms that service delivery models such as EIS that are backed by a wealth of evidence and local guidelines can be made available to wide sections of the population rapidly, while maintaining quality and fidelity.

While our study found that most programs adhere to standards and offer high-quality services, it also adds to growing evidence about implementation or evidence-practice gaps in EIS. Our findings also suggest that newer programs might require more time and support to begin implementing more complex interventions.

Ongoing monitoring of EIS performance to identify implementation strengths and gaps vis-à-vis standards and evidence is warranted. While fidelity scales could address this need, their widespread use seems incumbent on high levels of human and financial resources.24,69 However, remote or self-reported fidelity assessments may mitigate the burden of onsite fidelity audits.23,25 For jurisdictions currently developing EIS on a large scale, embedding quality assurance monitoring within the global implementation scheme should be considered.20,70 Other innovative methods to evaluate program operations and improve adherence to essential components such as rapid learning health systems are currently being studied. 71 In the latter, technology-enabled continuous data collection allows for real-time feedback and tailoring of training to data-informed implementation gaps, 72 simultaneously addressing the needs of quality monitoring and improvement. 73

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-2-cpa-10.1177_07067437211065726 for The Impact of Policy Changes, Dedicated Funding and Implementation Support on Early Intervention Programs for Psychosis by Bastian Bertulies-Esposito, Srividya Iyer and Amal Abdel-Baki in The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Amal Abdel-Baki is a founding member and elected president of the Association Québécoise des programmes pour premiers épisodes psychotiques (AQPPEP). Srividya Iyer was elected Vice-President of the International Association for Youth Mental Health in 2021.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article. Srividya Iyer was supported by a salary award from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

ORCID iDs: Bastian Bertulies-Esposito https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7285-0181

Srividya Iyer https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5367-9086

Amal Abdel-Baki https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3333-9652

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1.Correll CU, Galling B, Pawar A, et al. Comparison of early intervention services vs treatment as usual for early-phase psychosis: a systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75(6):555‐565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cocchi A, Cavicchini A, Collavo M, et al. Implementation and development of early intervention in psychosis services in Italy: a national survey promoted by the Associazione Italiana Interventi Precoci nelle Psicosi. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2018;12(1):37-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Catts SV, Evans RW, O’Toole BI, et al. Is a national framework for implementing early psychosis services necessary? Results of a survey of Australian mental health service directors. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2010;4(1):25-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ehmann T, Hanson L, Yager J, et al. Standards and guidelines for early psychosis intervention (EPI) programs. Victoria: British Columbia Ministry of Health Services; 2010. p. 105. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Csillag C, Nordentoft M, Mizuno M, et al. Early intervention services in psychosis: from evidence to wide implementation. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2016;10(6):540-546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Csillag C, Nordentoft M, Mizuno M, et al. Early intervention in psychosis: from clinical intervention to health system implementation. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2018;12(4):757-764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bertulies-Esposito B, Nolin M, Iyer SN, et al. Ou en sommes-nous? An overview of successes and challenges after 30 years of early intervention services for psychosis in Quebec: ou en sommes-nous? Un apercu des reussites et des problemes apres 30 ans de services d’intervention precoce pour la psychose au quebec. Can J Psychiatry. 2020;65(8):536-547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nolin M, Malla A, Tibbo P, et al. Early intervention for psychosis in Canada: what is the state of affairs? Can J Psychiatry. 2016;61(3):186-194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ministère de la Santé et des Services sociaux. Plan d’action en santé mentale 2015–2020. Québec: Gouvernement du Québec; 2015. p. 82. [Google Scholar]

- 10.La Presse Canadienne. Québec investit 26,5 millions en santé mentale. Le Devoir. 2017. [accessed 2017 Jun 15]. https://www.ledevoir.com/societe/sante/497541/quebec-investit-26-5-millions-en-sante-mentale.

- 11.Ministère de la Santé et des Services sociaux. Cadre de référence: programmes d’interventions pour premiers épisodes psychotiques (PIPEP). Québec: Gouvernement du Québec; 2017. p. 56. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gilbert M, Jackson O. Proposition de guide à l’implantation des équipes de premier épisode psychotique. Montréal: Centre national d'excellence en santé mentale; 2014. p. 17. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chong SA, Lee C, Bird L, et al. A risk reduction approach for schizophrenia: the early psychosis intervention programme. Ann Acad Med Singap. 2004;33(5):630-635. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lester H, Birchwood M, Bryan S, et al. Development and implementation of early intervention services for young people with psychosis: case study. Br J Psychiatry. 2009;194(5):446-450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mancini AD, Moser LL, Whitley R, et al. Assertive community treatment: facilitators and barriers to implementation in routine mental health settings. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60(2):189-195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moser LL, Deluca NL, Bond GR, et al. Implementing evidence-based psychosocial practices: lessons learned from statewide implementation of two practices. CNS Spectr. 2004;9(12):926-936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Durbin J, Selick A, Hierlihy D, et al. A first step in system improvement: a survey of early psychosis intervention programmes in Ontario. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2016;10(6):485-493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Edwards J, Harris MG, Bapat S. Developing services for first-episode psychosis and the critical period. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;187(Suppl. 48):s91-s97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brooks H, Pilgrim D, Rogers A. Innovation in mental health services: what are the key components of success? Implement Sci. 2011;6(120):1-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mascayano F, Nossel I, Bello I, et al. Understanding the implementation of coordinated specialty care for early psychosis in New York state: a guide using the re-aim framework. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2019;13(3):715-719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mueser KT, Meyer-Kalos PS, Glynn SM, et al. Implementation and fidelity assessment of the NAVIGATE treatment program for first episode psychosis in a multi-site study. Schizophr Res. 2019;204:271-281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Addington DE, Norman R, Bond GR, et al. Development and testing of the first-episode psychosis services fidelity scale. Psychiatr Serv. 2016;67(9):1023-1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Addington D, Noel V, Landers M, et al. Reliability and feasibility of the first-episode psychosis services fidelity scale-revised for remote assessment. Psychiatr Serv. 2020;71(12):1245-1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Durbin J, Selick A, Langill G, et al. Using fidelity measurement to assess quality of early psychosis intervention services in Ontario. Psychiatr Serv. 2019;70(9):840-844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Addington D, Cheng CC, French P, et al. International application of standards for health care quality, access and evaluation of services for early intervention in psychotic disorders. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2020;15(3):723-730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Institut de la statistique du Québec. Population et structure par âge et sexe - le Québec. 2019. [accessed 2021 Jun 11]. https://statistique.quebec.ca/fr/document/population-et-structure-par-age-et-sexe-le-quebec.

- 27.Nugter MA, Engelsbel F, Bahler M, et al. Outcomes of flexible assertive community treatment (FACT) implementation: a prospective real life study. Community Ment Health J. 2016;52(8):898-907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ministère de la Santé et des Services sociaux. Lignes directrices pour l’implantation de mesures de soutien dans la communauté en santé mentale. Québec: Gouvernement du Québec; 2002, p. 28. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Solomon P. The efficacy of case management services for severely mentally disabled clients. Community Ment Health J. 1992;28:163-180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lagacé G, Chassé B, Tremblay M-È. La naissance des équipes flexible assertive community treatment (Fact) au Québec. Journées annuelles de santé mentale. Conference in Montréal, Québec, 8 May 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 31.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Implementing the early intervention in psychosis access and waiting time standard: Guidance. London; 2016. p. 57. [PubMed]

- 32.Melton R, Blea P, Hayden-Lewis KA, et al. Practice guidelines for Oregon early assessment and support alliance (EASA). 2013. p. 88.

- 33.Hughes F, Stavely H, Simpson R, et al. At the heart of an early psychosis centre: the core components of the 2014 early psychosis prevention and intervention centre model for Australian communities. Australas Psychiatry. 2014;22(3):228-234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Early Psychosis Guidelines Writing Group and EPPIC National Support Program. Australian Clinical guidelines for early psychosis. Melbourne: Orygen, The National Centre of Excellence in Youth Mental Health; 2016, p. 133. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Early Intervention in Psychosis Network (EIPN). Standards for early intervention in psychosis services. London: Royal College of Psychiatrists; 2016. p. 62. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. Early psychosis intervention program standards. 2011:36 p.

- 37.Doyle R, Turner N, Fanning F, et al. First-episode psychosis and disengagement from treatment: a systematic review. Psychiatr Serv. 2014;65(5):603-611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Turner M, Nightingale S, Mulder R, et al. Evaluation of early intervention for psychosis services in New Zealand: what works? Auckland: Health Research Council of New Zealand; 2002. p. 207. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Melau M, Albert N, Nordentoft M. Programme fidelity of specialized early intervention in Denmark. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2019;13(3):627-632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nova Scotia Department of Health. Nova Scotia provincial service standards for early psychosis. Nova Scotia: Halifax; 2004. p. 7. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Anderson KK, Norman R, MacDougall AG, et al. Disparities in access to early psychosis intervention services: comparison of service users and nonusers in health administrative data. Can J Psychiatry. 2018;63(6):395-403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lal S, Malla A. Service engagement in first-episode psychosis: current issues and future directions. Can J Psychiatry. 2015;60(8):341-345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.O’Brien A, Fahmy R, Singh SP. Disengagement from mental health services. A literature review. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2009;44(7):558-568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Howes OD, Whitehurst T, Shatalina E, et al. The clinical significance of duration of untreated psychosis: an umbrella review and random-effects meta-analysis. World Psychiatry. 2021;20(1):75-95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jones AM, Shealy KM, Reid-Quinones K, et al. Guidelines for establishing a telemental health program to provide evidence-based therapy for trauma-exposed children and families. Psychol Serv. 2014;11(4):398-409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Larsen TK, McGlashan TH, Johannessen JO, et al. Shortened duration of untreated first episode of psychosis: changes in patient characteristics at treatment. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158(11):1917-1919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Melle I, Larsen TK, Haahr U, et al. Reducing the duration of untreated first-episode psychosis: effects on clinical presentation. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61(2):143-150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hegelstad WT, Larsen TK, Auestad B, et al. Long-term follow-up of the TIPS early detection in psychosis study: effects on 10-year outcome. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169(4):374-380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Malla A, Dama M, Iyer S, et al. Understanding components of duration of untreated psychosis and relevance for early intervention services in the Canadian context: comprendre les composantes de la duree de la psychose non traitee et la pertinence de services d’intervention precoce dans le contexte canadien. Can J Psychiatry. 2021. 66(10):878-886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.L’Heureux S, Nicole L, Abdel-Baki A, et al. Améliorer la détection et le traitement des psychoses débutantes au Québec : l’association québécoise des programmes pour premiers épisodes psychotiques (AQPPEP) y voit [improving detection and treatment of early psychosis in quebec: the Quebec association of early psychosis (l’association quebecoise des programmes pour premiers episodes psychotiques, AQPPEP), sees to it]. Sante Ment Que. 2007;32(1):299-315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Phillips SD, Burns BJ, Edgar ER, et al. Moving assertive community treatment into standard practice. Psychiatr Serv. 2001;52(6):771-779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Whitley R, Gingerich S, Lutz WJ, et al. Implementing the illness management and recovery program in community mental health settings: facilitators and barriers. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60(2):202-209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Conus P, Abdel-Baki A, Krebs MO, et al. Mieux diffuser le savoir et l’expérience relative à l’intervention précoce dans les troubles psychiatriques : création d’une branche francophone de l'IEPA. L’information psychiatrique. 2019;95(3):155-158. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ministère de la Santé et des Services sociaux. Le ministre Lionel Carmant annonce un financement de 10 m$ permettant d’offrir un meilleur accès aux services destinés aux jeunes ayant de premiers épisodes psychotiques. 2020. [accessed 2021 Jan 08]. Available from: https://www.msss.gouv.qc.ca/ministere/salle-de-presse/communique-2481/.

- 55.Guo T, Xiang YT, Xiao L, et al. Measurement-based care versus standard care for major depression: a randomized controlled trial with blind raters. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172(10):1004-1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mascayano F, van der Ven E, Martinez-Ales G, et al. Disengagement from early intervention services for psychosis: a systematic review. Psychiatr Serv. 2021;72(1):49-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Malla A, Joober R, Iyer S, et al. Comparing three-year extension of early intervention service to regular care following two years of early intervention service in first-episode psychosis: a randomized single blind clinical trial. World Psychiatry. 2017;16(3):278-286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rodrigues R, Anderson KK. The traumatic experience of first-episode psychosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophr Res. 2017;189:27-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Belling R, Whittock M, McLaren S, et al. Achieving continuity of care: facilitators and barriers in community mental health teams. Implement Sci. 2011;6(23):1-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Krabbendam L, van Os J. Schizophrenia and urbanicity: a major environmental influence--conditional on genetic risk. Schizophr Bull. 2005;31(4):795-799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.van Os J, Hanssen M, Bijl RV, et al. Prevalence of psychotic disorder and community level of psychotic symptoms: an urban-rural comparison. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58(7):663-668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bourque F, van der Ven E, Malla A. A meta-analysis of the risk for psychotic disorders among first- and second-generation immigrants. Psychol Med. 2011;41(5):897-910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ayano G, Tesfaw G, Shumet S. The prevalence of schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders among homeless people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry. 2019;19(1):370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Di Forti M, Quattrone D, Freeman TP, et al. The contribution of cannabis use to variation in the incidence of psychotic disorder across Europe (EU-GEI): a multicentre case-control study. Lancet Psychiat. 2019;6(5):427-436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Anderson KK, Norman R, MacDougall AG, et al. Estimating the incidence of first-episode psychosis using population-based health administrative data to inform early psychosis intervention services. Psychol Med. 2019;49(12):2091-2099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Fusar-Poli P, de Pablo G S, Correll CU, et al. Prevention of psychosis: advances in detection, prognosis, and intervention. JAMA Psychiat. 2020;77(7):755-765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nordentoft M, Melau M, Iversen T, et al. From research to practice: how OPUS treatment was accepted and implemented throughout Denmark. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2015;9(2):156-162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Dixon LB, Goldman HH, Srihari VH, et al. Transforming the treatment of schizophrenia in the United States: the RAISE initiative. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2018;14:237-258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Durbin J, Coriandoli R, Selick A, et al. Moving beyond the shoestring: highlights from a symposium to advance routine fidelity monitoring in Ontario’s community mental health and addiction system. Toronto: Centre for Addiction and Mental Health; 2020. p. 16. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Humensky JL, Bello I, Malinovsky I, et al. OnTrackNY’s learning healthcare system. J Clin Transl Sci. 2020;4(4):301-306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ferrari M, Iyer S, Leblanc A, et al. A rapid learning health system to support implementation of early intervention services for psychosis in Quebec, Canada: Study protocol. in preparation. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 72.Zurynski Y, Smith C, Vedovi A, et al. Mapping the learning health system: a scoping review of current evidence. Sydney (Australia): Australian Institute of Health Innovation, and the NHRMC Partnership Centre for Health System Sustainability; 2020. p. 63. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hart L. Capacity building interventions in health information systems: action for stronger health systems. Chapel Hill (NC): MEASURE Evaluation, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; 2018. p. 24. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-2-cpa-10.1177_07067437211065726 for The Impact of Policy Changes, Dedicated Funding and Implementation Support on Early Intervention Programs for Psychosis by Bastian Bertulies-Esposito, Srividya Iyer and Amal Abdel-Baki in The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry