Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Patients with germline/somatic BRCA1/BRCA2 mutations (g/sBRCA1/2) comprise a distinct biologic subgroup of pancreas ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC).

METHODS:

Institutional databases were queried to identify patients who had PDAC with g/sBRCA1/2. Demographics, clinicopathologic details, genomic data (annotation sBRCA1/2 according to a precision oncology knowledge base for somatic mutations), zygosity, and outcomes were abstracted. Overall survival (OS) was estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method.

RESULTS:

In total, 136 patients with g/sBRCA1/2 were identified between January 2011 and June 2020. Germline BRCA1/2 (gBRCA1/2) mutation was identified in 116 patients (85%). Oncogenic somatic BRCA1/2 (sBRCA1/2) mutation was present in 20 patients (15%). Seventy-seven patients had biallelic BRCA1/2 mutations (83%), and 16 (17%) had heterozygous mutations. Sixty-five patients with stage IV disease received frontline platinum therapy, and 52 (80%) had a partial response. The median OS for entire cohort was 27.6 months (95% CI, 24.9-34.5 months), and the median OS for patients who had stage IV disease was 23 months (95% CI, 19-26 months). Seventy-one patients received a poly(adenosine diphosphate ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitor (PARPi), and 52 received PARPi monotherapy. For maintenance PARPi, 10 patients (36%) had a partial response, 12 (43%) had stable disease, and 6 (21%) had progression of disease as their best response. Six patients (21%) received maintenance PARPi for >2 years. For those with stage IV disease who received frontline platinum, the median OS was 26 months (95% CI, 20-52 months) for biallelic patients (n = 39) and 8.66 months (95% CI, 6.2 months to not reached) for heterozygous patients (n = 4). The median OS for those who received PARPi therapy was 26.5 months (95% CI, 24-53 months) for biallelic patients (n = 25) and 8.66 months (95% CI, 7.23 months to not reached) for heterozygous patients (n = 2).

CONCLUSIONS:

g/sBRCA1/2 mutations did not appear to have different actionable utility. Platinum and PARPi therapies offer therapeutic benefit, and very durable outcomes are observed in a subset of patients who have g/sBRCA1/2 mutations with biallelic status.

Keywords: biallelic, BRCA, germline, pancreas, platinum, somatic, zygosity

INTRODUCTION

In an unselected population of patients with pancreas adenocarcinoma (PDAC), 5% to 7% harbor a germline BRCA1/BRCA2 mutation (gBRCA).1 KRAS, SMAD4, TP53, and CDKN2A mutations typify the somatic genomic landscape of PDAC. Somatic BRCA1/BRCA2 mutations (sBRCA) are present in 3% to 4% of cases.2 Data in ovarian and prostate cancers indicate that the response to therapy and overall outcomes of sBRCA carriers are equivalent to those of gBRCA carriers.3,4 This observation is supported by a growing, albeit limited data set in PDAC.5–8

BRCA1 and BRCA2 are DNA damage repair genes involved in homologous recombination.9 Homologous recombination deficiency increases sensitivity to platinum DNA cross-linking agents, such as oxaliplatin, cisplatin, and carboplatin.10–12 In a randomized phase 2 trial evaluating cisplatin/gemcitabine with or without veliparib, patients with a gBRCA1/2 or PALB2 mutation had high response rates (74.1% and 65.2%, respectively) to and encouraging overall survival (OS) from frontline cisplatin-based therapy.13 In a recent retrospective analysis by Golan et al, patients with germline homologous recombination-deficient (HRD) PDAC (n = 24) who received platinum therapy had a longer median OS (mOS) (21.1 months) compared with those without an HRD alteration (mOS, 7.9 months; adjusted hazard ratio [HR], 3.36; 95% CI, 1.62-7.0; P = .001).8

Poly(adenosine diphosphate ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitor (PARPi) therapies inhibit single-strand DNA repair, resulting in the generation of double-strand breaks. In cells with deficient homologous recombination, double-strand breaks are ineffectively repaired, and accumulated DNA damage leads to cancer cell death.14–16 The landmark randomized phase 3 POLO (Pancreas Cancer Olaparib Ongoing) trial (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT02184195) evaluated maintenance olaparib in patients with gBRCA1/2. Patients who received olaparib demonstrated a longer progression-free survival compared with those who received placebo (7.4 vs 3.8 months; HR, 0.53; P = .004).17

The 2019 National Comprehensive Cancer Network Guidelines advocate for universal germline testing for all patients and somatic testing for any patient with advanced disease undergoing treatment—recommendations that were recently endorsed by the American Society of Clinical Oncology.18,19 Germline testing with a multigene panel is preferred because pathogenic germline alterations occur in up to 9.7% of patients with PDAC.20 Universal germline testing results in a significant number of undetected mutations, and prior studies suggest that patients with identified pathogenic germline alterations may have an improved survival.21–23

Given that g/sBRCA1/2 PDAC constitutes a distinct biologic subgroup, we evaluated the clinicopathologic characteristics, genomic descriptors, zygosity status, and oncogenicity of sBRCA1/2 mutations in a large patient cohort.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient Sequencing and Clinical Data Extraction

Institutional databases from Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSK) and the tumor registry were queried with Institutional Review Board oversight, using billing codes (International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision code C25; International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision code 157) to identify patients who had PDAC with g/sBRCA1/2 mutations. Patients with pathogenic/likely pathogenic variants were included. A medical record review was used to abstract clinical, pathologic, genomic, and demographic data. Zygosity was determined where feasible. All patients previously consented to an institutional protocol for genomic profiling using the capture-based, targeted sequencing panel MSK Integrated Mutation Profiling of Actionable Cancer Targets (MSK-IMPACT).24

BRCA Mutation Annotation

OncoKB, a precision oncology knowledge base for somatic mutations (www.oncokb.org),25 was used to adjudicate the oncogenicity of BRCA1/2 variants using OncoKB Curation Standard Operating Protocol, version 1.1 (Protocol 2: Assertion of the Oncogenic Effect of a Somatic Variant; https://sop.oncokb.org). Alterations were classified according to the OncoKB level of evidence indicating that the mutation is a predictive biomarker of drug response, with, e.g., level 1 alterations being US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-recognized and level 3B alterations predicting response to an FDA-approved or investigational agent in a disease setting other than the pertinent tumor type.

Germline and Somatic Zygosity of BRCA1/2

Allelic copy number state for g/sBRCA1/2 variants was determined using previously described methodology26. Allele-specific copy number inferences were made using the FACETS algorithm.27 To determine zygosity, the observed variant allele frequency of germline variants or somatic mutations in the tumor were compared with their expected values if there were a copy-number loss of heterozygosity (LOH) event targeting the wild-type allele. In addition to copy-number LOH, other types of somatic mutations also were considered for biallelic loss. For example, patients with a germline mutation and a somatic mutation or those with ≥2 somatic mutations affecting the same gene were designated as harboring biallelic inactivation.

Biostatistical Analyses

Patient and treatment characteristics were summarized using the frequency and percentage for categorical variables and the median and range for continuous features. OS was calculated from the date of diagnosis to the date of death or last follow-up. OS also was estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method and was compared between subgroups using a log-rank test. All statistical analyses were performed using R version 3.6.0 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing). All P values were 2-sided, and P values < .05 were considered to indicate statistical significance.

RESULTS

Summary Demographics

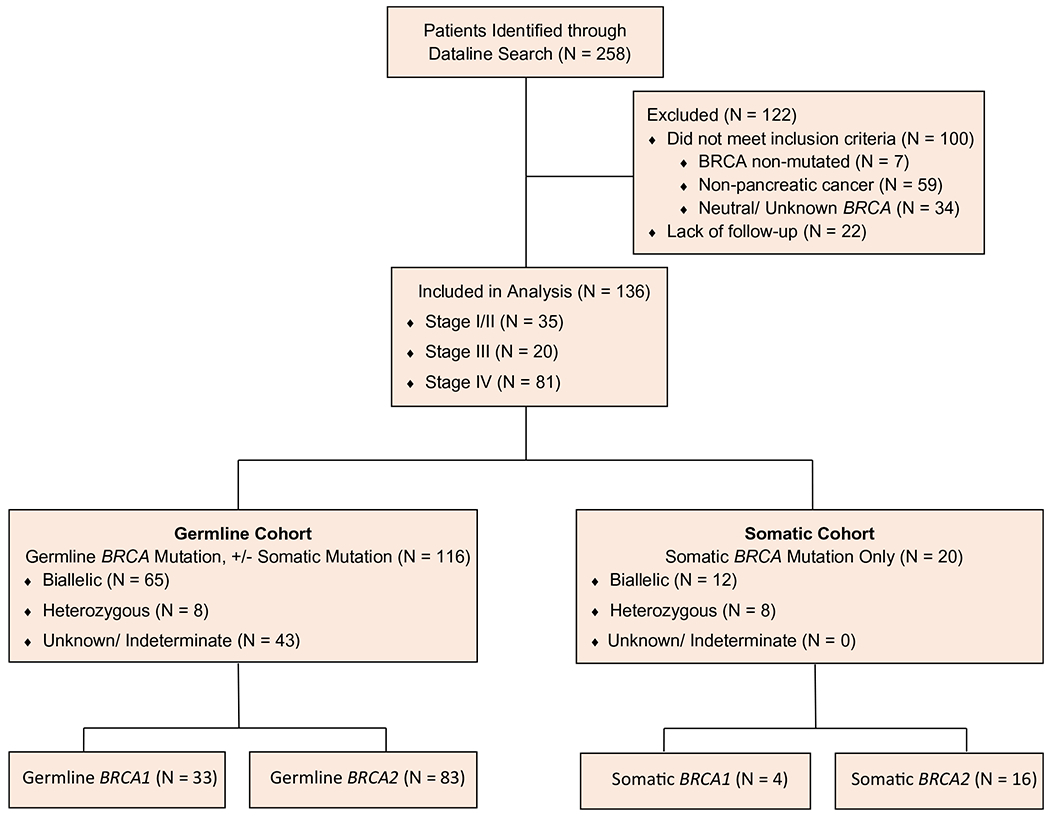

Between January 2011 and June 2020, 136 patients with g/sBRCA1/2 mutations and PDAC were identified (Fig. 1). The date for data cutoff was November 20, 2020. Patients with a gBRCA mutation were identified as germline irrespective of the presence of an sBRCA mutation; patients with an sBRCA mutation and no gBRCA mutation were identified as somatic. The median age at diagnosis for the gBRCA cohort was 60 years (range, 33-82 years), although 27 patients (23%) with a gBRCA mutation were aged ≥70 years (Table 1; see Supporting Fig. 5). Sixty-nine patients (59%) with a gBRCA mutation presented with stage IV disease. Of 52 patients with an sBRCA alteration, OncoKB annotation identified 23 who had an oncogenic sBRCA alteration. The 29 patients who had neutral mutations or variants of unknown significance were excluded from this analysis. In addition, 3 patients with sBRCA mutations that occurred as a consequence of a microsatellite-instability phenotype were also excluded.

Figure 1.

This is a CONSORT (Consolidated Standards for Reporting Trials) diagram of the current study.

TABLE 1.

Patient Characteristics, N = 136

| No. of Patients (%) |

||

|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Germline BRCA Cohort | Somatic BRCA Cohort |

| Sex | gBRCA, n = 116 | sBRCA, n = 20 |

| Men | 66 (57) | 8 (40) |

| Women | 50 (43) | 12 (60) |

| Age at diagnosis, y | ||

| Median [range], y | 60 [33-82] | 63 [25-83] |

| <40 | 4 (3) | 1 (5) |

| 40-49 | 10 (9) | 2 (10) |

| 50-59 | 42 (36) | 4 (20) |

| 60-69 | 33 (28) | 6 (30) |

| 70-79 | 22 (19) | 6 (30) |

| >80 | 5 (4) | 1 (5) |

| Histology | ||

| Adenocarcinoma | 112 (96) | 19 (95) |

| Adenosquamous | 1 (1) | – |

| Acinar | 3 (3) | 1 (5) |

| Stage at diagnosis | ||

| I/II | 30 (26) | 5 (25) |

| III | 17 (15) | 3 (15) |

| IV | 69 (59) | 12 (60) |

| Personal history of BRCA-assoc cancer | ||

| Yes | 27 (23) | 0 (0) |

| Type of BRCA-assoc cancer: Personal history | gBRCA, n = 27 | sBRCA, n = 1 |

| Breast | 19 (71) | – |

| Prostate | 6 (22) | – |

| Breast and ovarian | 2 (7) | – |

| BRCA-assoc cancer in first-degree relatives | gBRCA, n = 116 | sBRCA, n = 20 |

| Yes | 65 (56) | 4 (20) |

| Pancreatic cancer in first-degree relatives | ||

| Yes | 12 (10) | 1 (5) |

| Type of BRCA mutation | ||

| BRCA1 | 33 (28) | 4 (20) |

| BRCA2 | 83 (72) | 16 (80) |

| Zygosity | ||

| Biallelic | 65 (89) | 12 (60) |

| Heterozygous | 8 (11) | 8 (40) |

| Unknown/indeterminate | 43 | |

| AJ founder gBRCA mutation | ||

| Yes | 59 (51) | – |

| No | 57 (49) | – |

| Tumor mutation burden: Median [range], mt/Mb | 4.40 [0.0-13.2] | 5.10 [1.80-9.70] |

Abbreviations: AJ, Ashkenazi Jewish; assoc, associated; gBRCA, germline BRCA mutation; sBRCA, somatic BRCA mutation; mt/Mb, mutations per megabase.

Genomic Data

One hundred sixteen patients (85%) had a gBRCA1/2 mutation (n = 33 [28%] had a gBRCA1 mutation, and n = 83 [72%] had a gBRCA2 mutation). Fifty-nine patients (51%) had an Ashkenazi Jewish founder mutation (n = 16 had BRCA1c.68_69delAG, n = 4 had BRCA1c.5266dupC, and n = 39 had BRCA2c.5946delT). Sixty-five patients (89%) with gBRCA mutations had biallelic zygosity status, and 8 (11%) were heterozygous. Forty-three patients had unknown/indeterminate zygosity status without somatic testing or sufficient tissue for analysis. Nine patients (8%) with a gBRCA mutation had an additional pathogenic germline alteration, including alterations in ATM (n = 3), CHEK2 (n = 2), PALB2 (n = 1), MSH2 (n = 1), MSH6 (n = 1), and PMS2 (n = 1). The 3 patients with MSH2, MSH6, or PMS2 mutations were microsatellite stable and had tumor mutation burdens (TMBs) of 4.4, 5.3, and 5.9 mutations per megabase (mt/Mb), respectively. Twenty patients (15%) had an oncogenic sBRCA1/2 mutation and no gBRCA1/2mutation. Of these 20 patients, 4 (20%) had sBRCA1 mutations, and 16 (80%) had s BRCA2 mutations. Twelve patients (60%) were biallelic, and 8 (40%) were heterozygous.

In the entire cohort with somatic testing (n = 103), 90 patients (87%) had KRAS mutations, 63 (61%) had CDKN2A/CDKN2B mutations, 61 (59%) had TP53 mutations, and 33 (31%) had SMAD4 mutations, consistent with prior data, although the KRAS mutation rate may be lower.28 The median TMB was 4.40 mt/Mb (range, 0-13.2 mt/Mb) for the gBRCA cohort and 5.10 mt/Mb (range, 1.80-9.70 mt/Mb) for the sBRCA cohort. Of note, the median TMB in an unselected pancreas cohort (n = 2543) from the cBioPortal for Cancer Genomics (http://cbioportal.org)29,30 was 3.5 mt/Mb.

Family and Personal History of Cancer

Of 116 patients with gBRCA1/2 mutations, 65 (56%) reported a first-degree relative with a BRCA-associated malignancy (pancreas, breast, ovarian, prostate), of whom 13 had pancreas cancer.

Treatment Summary

Thirty-four patients (25%) underwent a Whipple surgery, and 11 (8%) underwent a distal pancreatectomy and splenectomy (see Supporting Table 1). Patients with stage IV disease who had gBRCA mutations received a median of 2 lines of therapy (range, 0-6 lines of therapy), and those with stage IV disease who had sBRCA mutations received a median of 3 lines of therapy (range, 0-5 lines of therapy) (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Stage IV Treatment Characteristics, N = 81

| No. of Patients (%) |

||

|---|---|---|

| Treatment Characteristic | Germline BRCA Cohort | Somatic BRCA Cohort |

| No of treatment lines | gBRCA, n = 69 | sBRCA, n = 12 |

| Median [range] | 2 [0-6] | 3 [0-5] |

| Frontline chemotherapy | gBRCA, n = 69 | sBRCA, n = 12 |

| Platinum | 58 (84) | 7 (58) |

| Gemcitabine and Nab-paclitaxel | 8 (12) | 4 (33) |

| Gemcitabine combination, other | 2 (3) | – |

| None | 1 (1) | 1 (8) |

| Frontline nonplatinum duration, mo | gBRCA | sBRCA |

| Median [range] | 6 [2-51] | 8 [3-40] |

| Frontline platinum duration, mo | gBRCA | sBRCA |

| Median [range] | 9 [1-31] | 10 [2-11] |

| Frontline platinum | gBRCA, n = 58 | sBRCA, n = 7 |

| Oxaliplatin | 33 (57) | 7 (100) |

| Cisplatin | 25 (43) | 0 (0) |

| Frontline platinum best overall response | gBRCA, n = 58 | sBRCA, n = 7 |

| PR | 46 (80) | 6 (86) |

| SD | 6 (10) | – |

| POD | 6 (10) | 1 (14) |

| Frontline oxaliplatin best overall response | gBRCA, n = 33 | sBRCA, n = 7 |

| PR | 28 (85) | 6 (86) |

| SD | 2 (6) | – |

| POD | 3 (9) | 1 (14) |

| Frontline cisplatin best overall response | gBRCA, n = 25 | sBRCA, n = 0 |

| PR | 18 (72) | – |

| SD | 4 (16) | – |

| POD | 3 (12) | – |

| Platinum therapy, any line | gBRCA n = 69 | sBRCA, n = 12 |

| Yes | 66 (96) | 10 (83) |

| Best overall response to platinum therapy, any line | gBRCA, n = 66 | sBRCA, n = 10 |

| PR | 50 (76) | 9 (90) |

| SD | 7 (10) | – |

| POD | 9 (14) | 1 (10) |

| Frontline nonplatinum best overall response | gBRCA, n = 10 | sBRCA, n = 4 |

| PR | 7 (70) | 1 (25) |

| SD | – | 2 (50) |

| POD | 3 (30) | 1 (25) |

Abbreviations: gBRCA, germline BRCA mutation; sBRCA, somatic BRCA mutation; Nab-paclitaxel, -bound paclitaxel; POD, progression of disease; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease.

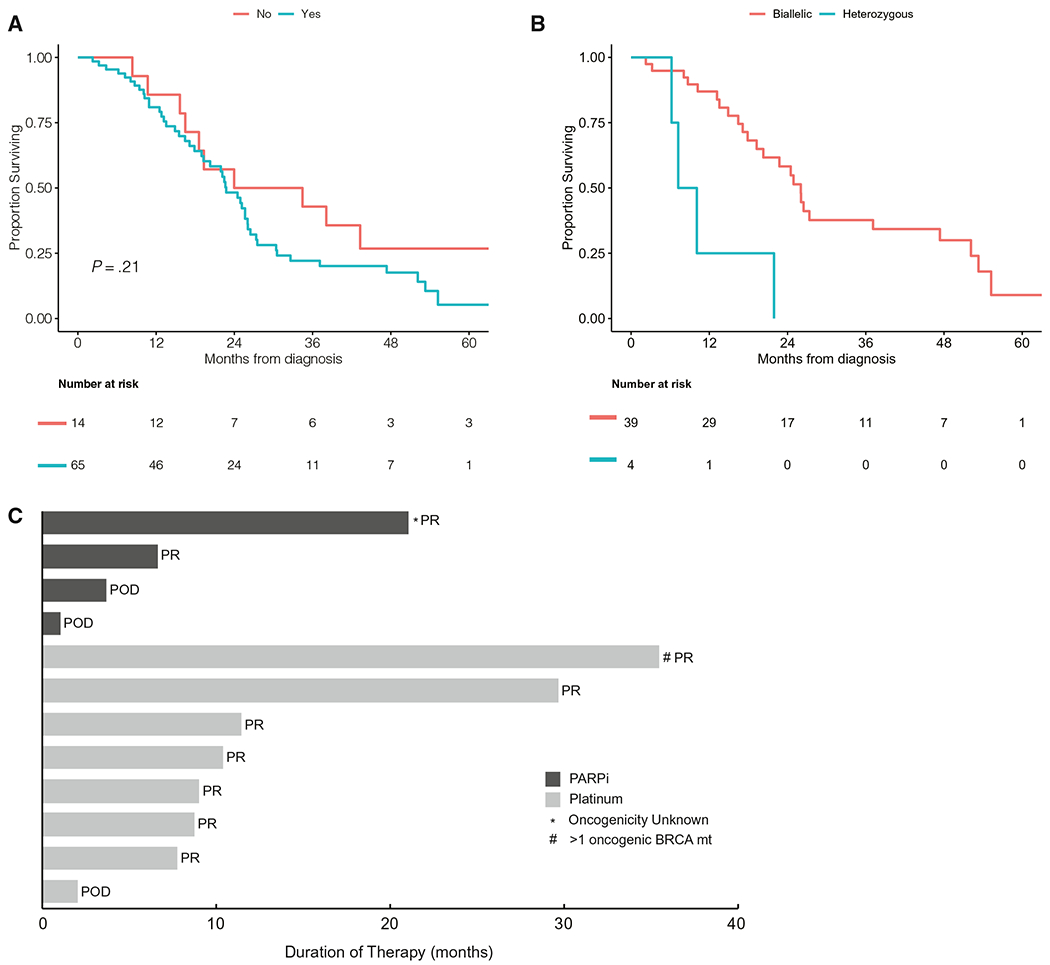

Platinum therapy

One hundred ten patients (81%) received platinum therapy as part of any metastatic line. Of 65 patients (80%) with stage IV disease who received frontline platinum, 40 (62%) received oxaliplatin, and 25 (38%) received cisplatin. Of 58 patients with stage IV disease who had gBRCA mutations and received frontline platinum, 46 (79%) had a partial response (PR), 6 (10%) had stable disease (SD), and 6 (10%) had progression of disease (POD) as their best response to therapy. Of the 7 patients with stage IV disease who had sBRCA mutations and received frontline platinum, 6 (86%) had a PR, and 1 (14%) had POD. No difference in the response rate was observed between oxaliplatin-based and cisplatin-based therapy. The median duration for frontline platinum therapy (calculated for those who developed POD) was 9 months (range, 0.5-31 months) for patients with stage IV disease who had gBRCA mutations and 10 months (range, 2-11 months) for those with stage IV disease who had sBRCA mutations. Twenty-one patients (35%) received maintenance PARPi after frontline platinum therapy, affecting the median duration of initial platinum therapy. The median duration of frontline nonplatinum therapy was 6 months (range, 2-51 months) for patients with stage IV disease who had gBRCA mutations and 8 months (range, 3-40 months) for those with stage IV disease who had sBRCA mutations. The mOS for patients with stage IV disease who received frontline platinum therapy (n = 65) was 23 months (95% CI, 19-26 months), and the mOS for those with stage IV disease who did not receive frontline platinum therapy (n = 14) was 29 months (95% CI, 19 months to NR) (Fig. 2A). Of 14 patients who did not receive frontline platinum therapy, 10 received platinum as second-line therapy; the median duration of therapy was 11 months (range, 1-35 months); and 7 patients had a PR, 1 had SD, and 2 had POD as their best response. Four patients with stage IV disease who had heterozygous BRCA mutations received frontline platinum therapy, and 3 of those 4 patients experienced POD after <6 months of treatment and had an OS <10 months.

Figure 2.

(A) Median overall survival is illustrated (A) for patients with stage IV pancreas cancer who did and did not receive frontline platinum therapy and (B) for patients with stage IV pancreas cancer who received frontline platinum therapy according to zygosity. (C) Platinum therapy and poly(adenosine diphosphate ribose) polymerase inhibitor (PARPi) therapy are illustrated in patients who had oncogenic BRCA1/BRCA2 alterations. This Swimmer plot indicates the months on therapy (either platinum-based or PARPi therapy) for 12 evaluable patients who had pancreatic cancer harboring an oncogenic* BRCA1/BRCA2 mutation (BRCA mut). Platinum response analysis was restricted to patients who had stage IV disease. Two patients with stage IV disease received platinum therapy followed by maintenance PARPi, and only their PARPi duration is captured on the plot. One patient who received a PARPi had a BRCA2 mutation of unknown significance. POD indicates progression of disease; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease.

Poly(adenosine diphosphate ribose) polymerase inhibitors

Seventy-one patients (52%) received a PARPi, 52 received PARPi monotherapy, 15 received a PARPi combined with chemotherapy, and 4 received a PARPi combined with immunotherapy (IO) (Table 3). The median duration of PARPi combined with chemotherapy or IO was 8 months (range, 1-19 months). Twenty-eight patients (54%) received PARPi monotherapy as maintenance therapy, and 24 (46%) received PARPi monotherapy at the time of disease progression. The median duration for maintenance PARPi monotherapy was 6 months (range, 1-39 months). Of 28 patients who received maintenance PARPi therapy, 10 (36%) had a PR, 12 (43%) had SD, and 6 (21%) had POD, including 1 PR in a patient with an sBRCA mutation. An additional patient who had a PR to PARPi therapy had an sBRCA variant of significance and a germline PALB2 mutation (gPALB2) and thus was not included in the general cohort. However, that patient had SD on niraparib for 21 months (Fig. 2C), likely underpinned by the gPALB2 variant. Twenty-four patients received PARPi therapy at disease progression, including 22 (92%) who were platinum-resistant and 2 who were therapy-resistant. Two of these patients (8%) had a PR, 7 (29%) had SD, and 15 (63%) had POD. The median duration of PARPi therapy administered at the time of disease progression was 2 months (range, 0.2-29 months).

TABLE 3.

Poly(Adenosine Diphosphate Ribose) Polymerase Inhibitor (PARPi) Therapy and Immunotherapy (IO)

| Variable | No. of Patients (%) |

|---|---|

| PARPi therapy: Entire cohort, n = 136 | |

| Yes | 71 (52) |

| PARPi therapy regimen: Patients who received PARPi, n = 71 | |

| Monotherapy | 52 (73) |

| PARPi and chemotherapy | 15 (21) |

| PARPi and IO | 4 (6) |

| PARPi with chemotherapy or IO: Duration | |

| Median [range], mo | 8 [1-19] |

| PARPi monotherapy: Patients who received PARPi monotherapy, n = 52 | |

| Olaparib | 40 (77) |

| Veliparib | 10 (19) |

| Multiplea | 2 (4) |

| Setting of PARPi monotherapy, n = 52 | |

| As maintenance therapy | 28 (54) |

| At POD | 24 (46) |

| PARPi monotherapy: Duration as maintenance | |

| Median [range], mo | 6 [1-39] |

| PARPi monotherapy: Duration at POD | |

| Median [range], mo | 2 [0-29] |

| Best overall response to maintenance PARPi monotherapy, n = 28 | |

| PR | 10 (36) |

| SD | 12 (43) |

| POD | 6 (21) |

| Best overall response to PARPi monotherapy at POD, n = 24 | |

| PR | 2 (8) |

| SD | 7 (29) |

| POD | 15 (63) |

| IO: Entire cohort, n = 136 | |

| Yes | 10 (7) |

| Type of IO treatment, n = 20 | |

| Anti-PD1/anti-PD-L1 | 7 (70) |

| Anti-CTLA-4 | 2 (20) |

| Combination anti-PD1/anti-CTLA-4b | 1 (10) |

| Best overall response to IO, n = 10 | |

| PR | 1 (10) |

| POD | 9 (90) |

Abbreviations: anti–CTLA-4, anticytotoxic T-lymphocyte–associated protein 4; anti-PD1, programmed death 1 inhibitor; anti–PD-L1, programmed death ligand 1 inhibitor; POD, progression of disease; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease.

One patient received olaparib, then rucaparib. One patient received olaparib, then veliparib.

One patient with a germline BRCA2 mutation had a marked partial response to combination immunotherapy initiated shortly before data cutoff.

Immunotherapy

Ten patients (7%) received IO, including 7 who received anti-PD1 (programmed death inhibitor) or PD-L1 therapy, 2 who received anticytotoxic T-lymphocyte–associated protein 4 (CTLA-4) therapy, and 1 who received combination anti-PD1 and anti–CTLA-4 therapy. Nine patients, all of whom were microsatellite-stable, experienced POD as their best response (frontline, n = 1; second line, n = 2; third line, n = 2; sixth line, n = 1). One patient with a gBRCA2 mutation who was microsatellite-stable and had a TMB of 4.4 mt/Mb initiated combination IO at the time of data cutoff and is experiencing a durable, ongoing PR.

Survival Outcomes

Among surviving patients (n = 46) at the time of data cutoff, the median follow-up was 31 months (range, 4-111 months). The mOS for the entire cohort was 27.6 months (95% CI, 24.9-34.5 months) (Fig. 3A). The mOS was 41 months (95% CI, 31 months to not reached [NR]) for patients with stage I and II disease, 42 months (95% CI, 30 months to NR) for those with stage III disease, and 23 months (95% CI, 19-26 months) for those with stage IV disease (Fig. 3B). The mOS for BRCA1 mutation carriers was 27 months (95% CI, 19-53), and it was 29 months (95% CI, 25-39 months) for BRCA2 mutation carriers (P = .64) (see Supporting Fig. 1). The mOS for the sBRCA cohort was 45 months (95% CI, 19 months to NR).

Figure 3.

Median overall survival is illustrated (A) for the entire cohort and (B) according to disease stage at diagnosis.

Zygosity Status and Survival

The mOS for stage IV biallelic patients was 25 months (95% CI, 19-52 months), and was 10 months (95% CI, 7.2 months for NR) for stage IV heterozygous patients (see Supporting Fig. 3A). The stage-adjusted HR demonstrated that germline monoallelic patients had a slightly increased risk of death compared with germline biallelic patients (HR, 1.71; 95% CI, 0.70-4.17; P = .24) (see Supporting Fig. 3B). Similarly, somatic monoallelic patients had a slightly increased risk of death compared with germline biallelic patients (HR, 1.1; 95% CI, 0.3-3.4; P = .86). Among the patients with stage IV disease who received frontline platinum, those with biallelic mutations (n = 39) had an mOS of 26 months (95% CI, 20-52 months), and, for those with heterozygous mutations (n = 4), the mOS was 8.7 months (95% CI, 6.2 months to NR). Biallelic patients who received PARPi therapy (n = 25) had an mOS of 26 months (95% CI, 24-53 months), and heterozygous patients who received PARPi therapy (n = 2) had an mOS of 8.7 months (95% CI, 7.2 months to NR). Because the OS estimates between different subgroups among patients with stage IV disease were based on small numbers, the results should be interpreted with caution.

DISCUSSION

BRCA-related PDAC represents a key subgroup of patients with unique tumor biology and an increasing number of targeted treatment options.7,31 To our knowledge, this is the most comprehensive cohort to date of patients with g/sBRCA-mutated PDAC (n = 136). Unique to this data set is the inclusion of both germline and/or somatic BRCA1/2 mutations and the detailed zygosity analysis and correlation with outcome. Golan et al observed that TMB and mutational signatures were consistent across somatic HRD and germline HRD PDAC, and durable responses to therapy were observed in patients with somatic BRCA2, XRCC2, and RAD51C alterations.8 Similarly, in a phase 2 trial of maintenance rucaparib by Reiss et al, 1 of 2 patients with sBRCA2 mutations had a durable response to PARPi therapy for >2 years.32 Furthermore, Park et al from our group observed that genomic instability and clinical outcomes between patients with germline and somatic HRD mutations were comparable.7 Herein, the difference in OS among patients with germline and somatic BRCA mutations was not significantly different (see Supporting Fig. 2). The 2-year OS rate for the germline cohort was 60% (95% CI, 52%-71%), and, for the somatic cohort, it was 62% (95% CI, 44%-89%). No statistically significant difference in OS was observed for BRCA1 versus BRCA2.

The median age at diagnosis of the gBRCA cohort was 60 years, similar to prior reports (see Supporting Table 3).33–36 In the gBRCA cohort, 27 patients (23%) were aged ≥70 years at diagnosis, and 5 were aged >80 years, emphasizing the need for age-agnostic germline testing.

This cohort of patients with g/sBRCA1/2 mutations had a notably higher OS compared with historical data for unselected PDAC. The mOS for entire cohort was 27.6 months (95% CI, 24.9-34.5 months), and the mOS for patients with stage IV disease was 23 months (95% CI, 19-26 months). A striking difference was observed in the stage IV cohort for biallelic status and improved outcome, although statistical significance was limited by the small number of patients with heterozygous zygosity (see Supporting Fig. 3). Of note, Golan et al observed that biallelic germline HRD carriers had superior OS compared with heterozygous carriers (23.3 vs 7.9 months; HR, 2.13; 95% CI, 0.88-5.16; P = .10).8 In a pan-cancer analysis by Sokol et al that measured TMB and global LOH as a surrogate for genomic instability, biallelic loss of BRCA1/2 led to significantly higher genomic instability compared with heterozygous loss of BRCA1/2, which may underscore the improved OS.37 The improved OS for the entire cohort was likely caused in part by the integration of platinum therapies, PARPi therapies, and a potential contribution from the prognostic impact of underlying disease biology. Park et al observed that patients who had HRD disease and received frontline platinum had a significantly reduced risk of disease progression compared with patients who had non-HRD disease (HR, 0.44; 95% CI, 0.28-0.66; P < .01).7

In this cohort, 65 patients with stage IV disease received frontline platinum therapy, and 52 (80%) experienced a PR to therapy. The median survival for patients with stage IV disease who received frontline platinum therapy was 23 months (95% CI, 19-26 months), which was not significantly different from patients who did not receive frontline platinum therapy (mOS, 29 months; 95% CI, 19 months to NR). Of note, the median duration of frontline and second-line platinum therapy and the response rates did not appear to be different. The median duration of frontline platinum for therapy patients with stage IV disease who had a g/sBRCA mutation was 9 months (95% CI, 1-31 months), and the median duration of second-line platinum therapy for with those with stage IV disease who had a g/sBRCA mutation was 11 months (95% CI, 1-35 months). Overall, 76 patients (94%) with stage IV disease received platinum therapy at some point during their treatment course, and 59 (78%) had a PR to treatment. These data support that platinum therapy may provide significant therapeutic benefit for patients with g/sBRCA mutations when administered as a later line of therapy.

In 2019, the phase 3 POLO trial results identified olaparib as an effective maintenance targeted therapeutic, the first of its kind with disease-specific Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval in PDAC.17 In this cohort, 52 patients received PARPi monotherapy. Of 28 patients who received maintenance PARPi therapy, 10 (35.7%) had a PR, including a PR in 1 patient with an sBRCA mutation. Several of these responses were very durable, including 3 patients who were on PARPi therapy for >2 years and an additional 3 who were on PARPi therapy for >3 years. In contrast, among the patients who received PARPi therapy at disease progression, only 2 (8.3%) had a PR, and the majority experienced POD with a short therapy duration of 2 months. PARPi therapy elicits more meaningful activity when integrated as maintenance therapy, and our data highlight the role of maintenance PARPi for sBRCA1/2 PDAC.

To date, single-agent or combination checkpoint inhibitor therapy has demonstrated little utility in PDAC outside of a small subset of 1% or 2% with mismatch repair deficiency.38,39 Some data support that patients with g/sBRCA1/2 mutations may be more predisposed to benefit from IO in view of increased genomic instability and a higher neoantigen burden.7,40,41 In an evaluation of tumor samples, Seeber et al observed that BRCA-mutated tumors had a higher TMB compared with wild-type BRCA tumors (mean, 8.7 vs 6.5 mt/Mb; P < .001).41 We also observed a higher TMB relative to the median of 3.50 mt/Mb for patients who had sporadic PDAC, with a median TMB of 4.40 mt/Mb for the gBRCA cohort and 5.10 mt/Mb for the sBRCA cohort. A recent pan-cancer study by Samstein et al supports that BRCA1/2 mutations may heighten the response to IO, specifically with respect to increased innate immune cell activity driven by BRCA2 alterations.42 In the analysis herein, 10 patients received IO, and 9 experienced POD as the best response to single-agent checkpoint inhibitor therapy; detailed outcome data on an additional patient are pending. Ongoing prospective studies will define the role of IO agents in BRCA-related PDAC and other subsets with mutations in homologous recombination genes (ClinicalTrials.gov identifiers NCT03193190 and NCT03816358) (see Supporting Table 2).

The oncogenicity of sBRCA variants underwent a rigorous adjudication in this cohort. Acknowledging the small size of our sBRCA cohort, these data suggest that an oncogenic sBRCA variant confers an equivalent benefit to platinum and PARPi therapy (relative to gBRCA), with survival outcomes of 40 months observed in selected patients. Currently, sBRCA variants in pancreas cancer are associated with a level 3A designation, as the FDA approval and NCCN language for PARPi specifies gBRCA. In addition, the number of patients with PDAC harboring sBRCA mutations who have responded to PARPi and reported in the literature is low (n = 2).5

There are several notable limitations to the current article, including the single-center, retrospective nature of the cohort and the relative lack of ethnic and racial diversity, although one-half of patients in the germline BRCA cohort had non–Ashkenazi Jewish founder mutations. Other limitations include variance in treatment regimens and durations, the 10-year time span of the study, and limited follow-up for some patients. Major strengths include the large number of patients, the analysis of both g/sBRCA1/2 variants, and zygosity status.

Conclusion

Patients who have PDAC with germline or somatic BRCA1/2 mutations comprise an extremely important minority subset, representing from 6% to 10% of all patients. The data herein support the use of platinum therapy and suggest that the use of PARPi therapy in a maintenance setting has significantly greater value over the use of PARPi therapy in the context of disease progression. Biallelic zygosity status enriches for improved outcomes to platinum and PARPi therapies. Although this study was limited by the small size of the sBRCA cohort, the therapeutic and biologic significance of biallelic g/sBRCA1/2 appears to be similar. Future directions will build on platinum and PARPi therapies and address the major challenge of de novo and acquired therapy resistance in this subset.

Supplementary Material

CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURES

Wungki Park reports a Paul Calabresi Career Development Award for Clinical Oncology (K12 CA184746) from the National Institutes of Health during the course of the study. Michel F. Burger reports research support from Grail and personal fees from Roche and Eli Lilly outside the submitted work. Debyani Chakravarty reports personal fees from Mendendi, Inc outside the submitted work. Kenneth H. Yu reports grants from Bristol-Myers Squibb (BMS) and General Oncology outside the submitted work. Geoffrey Y. Ku reports institutional research funding from AstraZeneca, BMS, and Merck; and personal fees from BMS and Merck outside the submitted work. James J. Harding reports grants from BMS; personal fees from BMS, Exelixis, Eisai, Eli Lilly, Merck, QED, ZymeWorks, Imvx, CytomX, and Adaptimmune; and participation on a data safety monitoring board or advisory board at Merck outside the submitted work. Ghassan K. Abou-Alfa reports institutional research funding from Agios, Arcus, AstraZeneca, Bayer, BioNtech, BMS, Celgene, Exelixis, Flatiron, Genentech/Roche, Genoscience, Incyte, Polaris, Puma, QED, Sillajen, and Yiviva; and personal fees from Adicet, Agios, Alnylam, AstraZeneca, Autem, Bayer, Beigene, Berry Genomics, Cend, Celgene, CytomX, Debio, Eisai, Eli Lilly, Exelixis, Flatiron, Genentech/Roche, Genoscience, Gilead, Helio, Incyte, Ipsen, Legend Biotech, Loxo, Merck, MINA, Nerviano, Polaris, QED, Redhill, Rafael, Silenseed, Sillajen, Sobi, Surface Oncology, Therabionics, Twoxar, Vector, and Yiviva outside the submitted work. Zsofia K. Stadler reports that an immediate family member serves as a consultant in ophthalmology for Alcon, Adverum, Allergen, Genentech/Roche, Gyroscope Tx, Neurogene, Novartis, Optos Plc, RegenexBio, Regeneron, and Optos Plc. Christine A. Iacobuzio-Donahue reports research support from BMS during the course of the current study. Eileen M. O’Reilly reports institutional research funding from Genentech/Roche, Celgene/BMS, BioNTech, BioAtla, AstraZeneca, Arcus, Parker Institute, and Pertzye; participation on a data safety monitory board at Cytomx Therapeutics and Rafael Therapeutics; personal fees from Sobi, Silenseed, Tyme, Seagen, Molecular Templates, Boehringer Ingelheim, BioNTech, Ipsen, Polaris, Merck, IDEAYA, Cend Therapeutics, AstraZeneca, Noxxon, and BioSapien; personal fees to her spouse from Bayer, Genentech-Roche, Celgene-BMS, and Eisai; and honoraria from Research to Practice, all outside the submitted work. The remaining authors made no disclosures.

FUNDING SUPPORT

This work was supported by a Cancer Center Support Grant (P30 CA008748) from the National Institutes of Health, the Reiss Family Foundation, and the David M. Rubenstein Center for Pancreas Cancer.

Footnotes

Additional supporting information may be found in the online version of this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Friedenson B BRCA1 and BRCA2 pathways and the risk of cancers other than breast or ovarian. MedGenMed. 2005;7:60. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lowery MA, Jordan EJ, Basturk O, et al. Real-time genomic profiling of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: potential actionability and correlation with clinical phenotype. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23:6094–6100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dougherty BA, Lai Z, Hodgson DR, et al. Biological and clinical evidence for somatic mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2 as predictive markers for olaparib response in high-grade serous ovarian cancers in the maintenance setting. Oncotarget. 2017;8:43653–43661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mateo J, Carreira S, Sandhu S, et al. DNA-repair defects and olaparib in metastatic prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1697–1708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shroff RT, Hendifar A, McWilliams RR, et al. Rucaparib monotherapy in patients with pancreatic cancer and a known deleterious BRCA mutation. JCO Precis Oncol. 2018;2:PO.17.00316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Golan T, Varadhachary GR, Sela T, et al. Phase II study of olaparib for BRCAness phenotype in pancreatic cancer [abstract]. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(4 suppl):297. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Park W, Chen J, Chou JF, et al. Genomic methods identify homologous recombination deficiency in pancreas adenocarcinoma and optimize treatment selection. Clin Cancer Res. 2020;26:3239–3247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Golan T, O’Kane GM, Denroche RE, et al. Genomic features and classification of homologous recombination deficient pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2021;160:2119–2132.e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tutt A, Ashworth A. The relationship between the roles of BRCA genes in DNA repair and cancer predisposition. Trends Mol Med. 2002;8:571–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Golan T, Javle M. DNA repair dysfunction in pancreatic cancer: a clinically relevant subtype for drug development. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2017;15:1063–1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tutt ANJ, Lord CJ, McCabe N, et al. Exploiting the DNA repair defect in BRCA mutant cells in the design of new therapeutic strategies for cancer. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 2005;70:139–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brennan GT, Relias V, Saif MW. BRCA and pancreatic cancer. JOP. 2013;14:325–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.O’Reilly EM, Lee JW, Zalupski M, et al. Randomized, multicenter, phase II trial of gemcitabine and cisplatin with or without veliparib in patients with pancreas adenocarcinoma and a germline BRCA/PALB2 mutation. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38:1378–1388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lord CJ, Ashworth A. The DNA damage response and cancer therapy. Nature. 2012;481:287–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Farmer H, McCabe N, Lord CJ, et al. Targeting the DNA repair defect in BRCA mutant cells as a therapeutic strategy. Nature. 2005;434:917–921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bryant HE, Schultz N, Thomas HD, et al. Specific killing of BRCA2-deficient tumours with inhibitors of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase. Nature. 2005;434:913–917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Golan T, Hammel P, Reni M, et al. Maintenance olaparib for germline BRCA-mutated metastatic pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:317–327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tempero MA. NCCN Guidelines updates: pancreatic cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2019;17:603–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sohal DPS, Kennedy EB, Khorana A, et al. Metastatic pancreatic cancer: ASCO clinical practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:2545–2556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rainone M, Singh I, Salo-Mullen EE, Stadler ZK, O’Reilly EM. An emerging paradigm for germline testing in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma and immediate implications for clinical practice: a review. JAMA Oncol. 2020;6:764–771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brand R, Borazanci E, Speare V, et al. Prospective study of germline genetic testing in incident cases of pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Cancer. 2018;124:3520–3527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mandelker D, Zhang L, Kemel Y, et al. Mutation detection in patients with advanced cancer by universal sequencing of cancer-related genes in tumor and normal DNA vs guideline-based germline testing. JAMA. 2017;318:825–835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lowery MA, Wong W, Jordan EJ, et al. Prospective evaluation of germline alterations in patients with exocrine pancreatic neoplasms. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2018;110:1067–1074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zehir A, Benayed R, Shah RH, et al. Mutational landscape of metastatic cancer revealed from prospective clinical sequencing of 10,000 patients. Nat Med. 2017;23:703–713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chakravarty D, Gao J, Phillips S, et al. OncoKB: a precision oncology knowledge base. JCO Precis Oncol. 2017;1:PO.17.00011. doi: 10.1200/PO.17.00011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jonsson P, Bandlamudi C, Cheng ML, et al. Tumour lineage shapes BRCA-mediated phenotypes. Nature. 2019;571:576–579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shen R, Seshan VE. FACETS: allele-specific copy number and clonal heterogeneity analysis tool for high-throughput DNA sequencing. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:e131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jones S, Zhang X, Parsons DW, et al. Core signaling pathways in human pancreatic cancers revealed by global genomic analyses. Science. 2008;321:1801–1806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cerami E, Gao J, Dogrusoz U, et al. The cBio cancer genomics portal: an open platform for exploring multidimensional cancer genomics data. Cancer Discov. 2012;2:401–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gao J, Askoy BA, Dogrusoz U, et al. Integrative analysis of complex cancer genomics and clinical profiles using the cBioPortal. Sci Signal. 2013;6:p|1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pishvaian MJ, Blais EM, Brody JR, et al. Overall survival in patients with pancreatic cancer receiving matched therapies following molecular profiling: a retrospective analysis of the Know Your Tumor registry trial. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:508–518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reiss KA, Mick R, O’Hara MH, et al. Phase II study of maintenance rucaparib in patients with platinum-sensitive advanced pancreatic cancer and a pathogenic germline or somatic variant in BRCA1, BRCA2, or PALB2. J Clin Oncol. Published online May 10, 2021. doi: 10.1200/JCO.21.00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Blair AB, Groot VP, Gemenetzis G, et al. BRCA1/BRCA2 germline mutation carriers and sporadic pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. J Am Coll Surg. 2018;226:630–637.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Golan T, Kanji ZS, Epelbaum R, et al. Overall survival and clinical characteristics of pancreatic cancer in BRCA mutation carriers. Br J Cancer. 2014;111:1132–1138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lowery MA, Kelsen DP, Stadler ZK, et al. An emerging entity: pancreatic adenocarcinoma associated with a known BRCA mutation: clinical descriptors, treatment implications, and future directions. Oncologist. 2011;16:1397–1402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Adel N Current treatment landscape and emerging therapies for pancreatic cancer. Am J Manag Care. 2019;25(1 suppl):S3–S10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sokol ES, Pavlick D, Khiabanian H, et al. Pan-cancer analysis of BRCA1 and BRCA2 genomic alterations and their association with genomic instability as measured by genome-wide loss of heterozygosity. JCO Precis Oncol. 2020;4:442–465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Marabelle A, Le DT, Ascierto PA, et al. Efficacy of pembrolizumab in patients with noncolorectal high microsatellite instability/mismatch repair-deficient cancer: results from the phase II KEYNOTE-158 study. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.O’Reilly EM, Oh DY, Dhani N, et al. Durvalumab with or without tremelimumab for patients with metastatic pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: a phase 2 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2019;5:1431–1438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Connor AA, Denroche RE, Jang GH, et al. Association of distinct mutational signatures with correlates of increased immune activity in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3:774–783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Seeber A, Zimmer K, Kocher F, et al. Molecular characteristics of BRCA1/2 and PALB2 mutations in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. ESMO Open. 2020;5:e000942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Samstein RM, Krishna C, Ma X, et al. Mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2 differentially affect the tumor microenvironment and response to checkpoint blockade immunotherapy. Nat Cancer. 2020;1:1188–1203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.