Abstract

Background/Aim: There have not been enough recent studies investigating the incidence or efficacy of dose reduction in adjuvant chemotherapy for epithelial ovarian cancer. This study examined whether patients who needed dose reduction showed poorer survival outcomes.

Patients and Methods: From 2011 to 2021, 102 patients were included in the study. Patients who underwent neoadjuvant chemotherapy and those with early-stage disease were excluded. Patients were divided into two groups: those who had a ≥60% dose reduction during the whole period of first-line adjuvant chemotherapy, and those with dose reductions <60%. Of the 102 patients, 38 (37.3%) underwent dose reduction ≥60%.

Results: PFS was significantly longer in the group whose dose reductions were ≥60%, whereas OS was not significant.

Conclusion: A dose reduction of ≥60%, determined by patients’ medical conditions, during first-line of adjuvant chemotherapy does not negatively influence survival outcomes, such as OS and PFS, in advanced epithelial ovarian cancer.

Keywords: Chemotherapy, clinical outcomes, dose reduction, ovarian cancer, overall survival, progression-free survival

Epithelial ovarian cancer is a refractory disease with a high mortality rate and high risk of recurrence. It is the eighth most common malignancy in women (1). The standard treatment involves surgical resection of lesions and adjuvant chemotherapy (2). Despite a few uncertainties, adjuvant chemotherapy is beneficial, even at very early stages (3).

Recent studies have indicated that almost half the patients with advanced ovarian cancer experience dose reductions during chemotherapy (4,5). Earlier studies reported that over 77% of the patients with stage I to III ovarian cancer were prescribed dose reductions ≥15% compared to the planned regimens; this was more than twice that of breast cancer and slightly lower than that of colorectal cancer (6). Several comparative studies have reported adverse effects of dose reduction on survival outcomes; however, the definition of dose reduction was inconsistent, and recent studies are lacking (4,5,7). There have been no randomized controlled trials or meta-analyses; there have been a few observational studies. Gynecological oncologists decide the dose reduction based on their subjective judgment, without the benefit of sufficient reliable evidence. Dose reduction decisions are commonly based on hematological toxicity and chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy (CIPN) (8,9). The incidences of hematologic toxicity and CIPN during chemotherapy for ovarian cancer occur in approximately 88% and 20% of cases, respectively (10,11).

Although adjuvant chemotherapy is necessary, and its dose is frequently reduced, there are not sufficient recent studies on the incidence or efficacy of dose reduction. Therefore, the present study examined whether patients who required dose reductions during first-line adjuvant chemotherapy had worse survival outcomes.

Patients and Methods

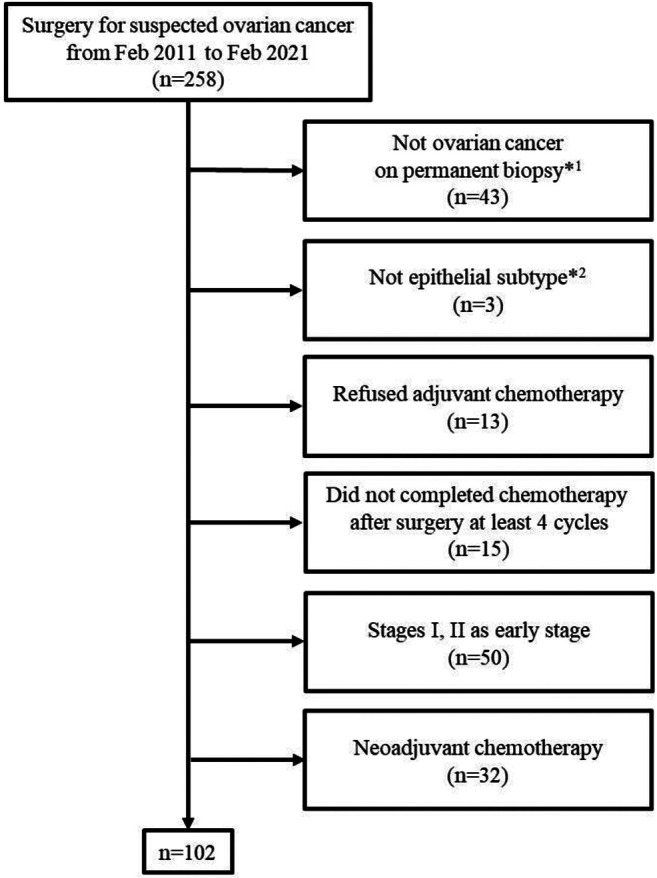

Patients. The medical records of 258 patients who underwent surgery for suspected ovarian cancer at the Kyungpook National University Chilgok Hospital (KNUCH) from February 2011 to February 2021 were reviewed. A total of 43 patients were excluded because they had not been diagnosed with primary ovarian cancer. Three cases whose histologic subtypes were not epithelial were also excluded. Thirteen patients were excluded because they refused adjuvant chemotherapy after surgery. Fifteen patients were excluded because they could not complete at least four cycles of first-line adjuvant chemotherapy (12). Fifty patients with early-stage (I and II) ovarian cancer were excluded. Thirty-two patients who underwent neoadjuvant chemotherapy were excluded. In total, 102 patients who completed the standard treatment, consisting of debulking surgery and adjuvant chemotherapy, were included in this study (Figure 1). The stage of ovarian cancer was evaluated according to the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics staging criteria (13). This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of KNUCH (KNUCH 2021-12-031).

Figure 1. Flow diagram for patient selection. *1Included benign, borderline, and other primary malignancies, such as endometrial cancer or colon cancer; *2included germ cell tumor, sex cord stromal tumor, and other subtypes.

Surgery. All operations and further treatments were conducted by four experienced gynecologic oncologists at the KNUCH. Optimal debulking surgeries for ovarian cancer included total hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo–oophorectomy, lymphadenectomy from the pelvic side to the infra-renal level, omentectomy, and resection of other metastatic lesions. A surgery was defined as suboptimal when the residual tumor was larger than 1 cm (14).

Chemotherapy. For first-line adjuvant chemotherapy, all patients received a combination of taxane and platinum agents; the dose of taxane was calculated as 175 mg/m2, and AUC 5 was used to determine the dose of the platinum agent. The included participants were divided into two groups; one underwent a dose reduction of chemotherapy agents <60%, and the other group’s dose reductions were ≥60% during the whole period of first-line adjuvant chemotherapy. We determined 60% as the threshold because it was the most common reduction in the group that underwent the dose reduction in our data. The interval to initiation was defined as the number of days from surgery to first administration of chemotherapy agents. The duration was defined as the number of days from the first to last day of administration of chemotherapy agents. We intended to keep the interval between administrations at 21 days; for example, a patient has 105 days as the planned duration for all six cycles of chemotherapy but can complete the chemotherapy within 105 days or more; the number of days beyond the planned duration was defined as the total delay. Delivered dose intensity was defined as the sum of the total ratio of chemotherapy agents administered over the course; for example, when a patient used 100% of the chemotherapy agent in each of the six cycles, we recorded it as 600%. Relative dose intensity (RDI) was the ratio of the delivered dose intensity divided by the planned dose intensity. Total dose reduction was the sum of each ratio of reduction; for example, when a patient used 90% in every six-cycle, we recorded it as 60%.

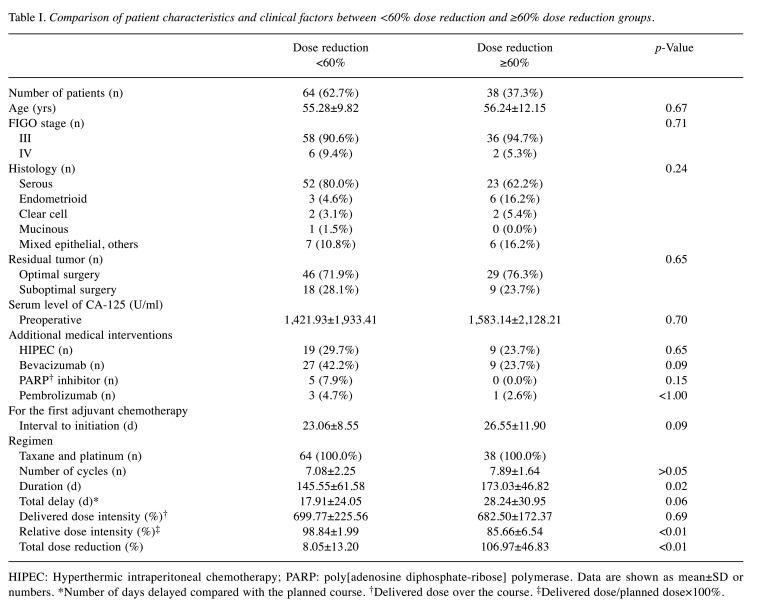

Additional medical interventions. Some patients underwent one or more additional treatments based on their medical conditions; such as hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC), bevacizumab, poly(adenosine diphosphate-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitors, and pembrolizumab. HIPEC included patients who underwent HIPEC during the first debulking surgery or the second surgery to resect metastatic lesions. Patients who used bevacizumab with taxane and platinum or as a maintenance regimen were included. Regarding PARP inhibitors and pembrolizumab, we included patients who used one of them for at least four weeks (Table I).

Table I. Comparison of patient characteristics and clinical factors between <60% dose reduction and ≥60% dose reduction groups.

HIPEC: Hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy; PARP: poly[adenosine diphosphate-ribose] polymerase. Data are shown as mean±SD or numbers. *Number of days delayed compared with the planned course. †Delivered dose over the course. ‡Delivered dose/planned dose×100%.

Statistical analysis. The data of the two groups were compared using the Student’s t-test and the Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test. To analyze OS and PFS, Kaplan-Meier survival analysis and Cox regression were used. Linear regression was also applied for subgroup analysis. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (version 26; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) and MedCalc (version 20.026; MedCalc Software Ltd., Ostend, Belgium).

Results

Out of 102 patients, 64 (62.7%) underwent chemotherapy agent dose reductions <60% during first-line adjuvant chemotherapy, and 38 (37.3%) underwent dose reductions ≥60%. There were no significant differences between the two groups in terms of age, stage, histology, residual tumors, and preoperative serum levels of cancer antigen 125 (CA-125). No significant difference was found in the number of patients who underwent HIPEC or used bevacizumab, PARP inhibitors, or pembrolizumab. For chemotherapy, there were no significant differences in interval to initiation, regimen, number of cycles, total delay, and delivered dose intensity of chemotherapy agents. Significant differences were found for chemotherapy duration, RDI, and total dose reduction (p=0.02, p<0.01, and p<0.01, respectively) (Table I).

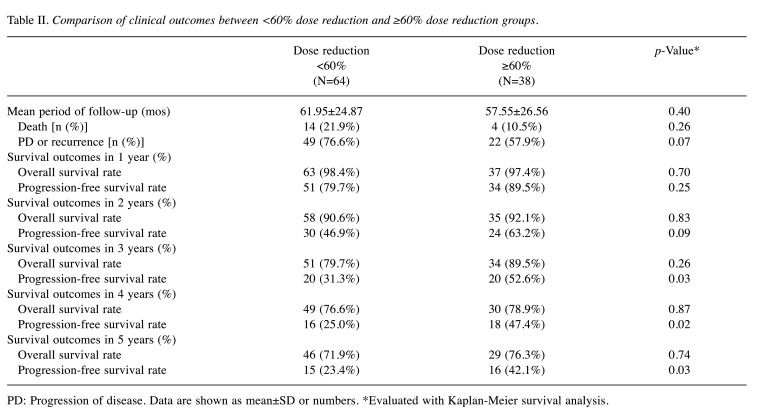

Clinical outcomes were compared between the two groups. Mean follow-up periods were 61.95±24.87 (mos) and 57.55±26.56 (mos) in the <60% and ≥60% dose reduction groups, respectively. In this period, 14 (21.9%) patients died, and progression or recurrence of disease occurred in 49 (76.6%) patients in the <60% group; four (10.5%) patients died, and progression or recurrence occurred in 22 (57.9%) patients in the ≥60% group. No significant difference was observed (p=0.26, p=0.07). Over 3 years, the OS rate was 79.7% and 89.5% in the <60% and ≥60% reduction groups, respectively, but this difference was not significant (p=0.26). For PFS, significant differences began to appear from the third year onwards, and the PFS rate was significantly higher in the ≥60% dose reduction group compared to the <60% dose reduction group (52.6% vs. 31.3%, respectively; p=0.03). In 5 years, the OS rates were 71.9% and 76.3% in the <60% and ≥60% reduction groups, respectively, but the difference was not significant (p=0.74). The PFS rate was significantly higher in the ≥60% dose reduction group compared with the <60% dose reduction group (42.1% vs. 23.4%, respectively; p=0.03) (Table II).

Table II. Comparison of clinical outcomes between <60% dose reduction and ≥60% dose reduction groups.

PD: Progression of disease. Data are shown as mean±SD or numbers. *Evaluated with Kaplan-Meier survival analysis.

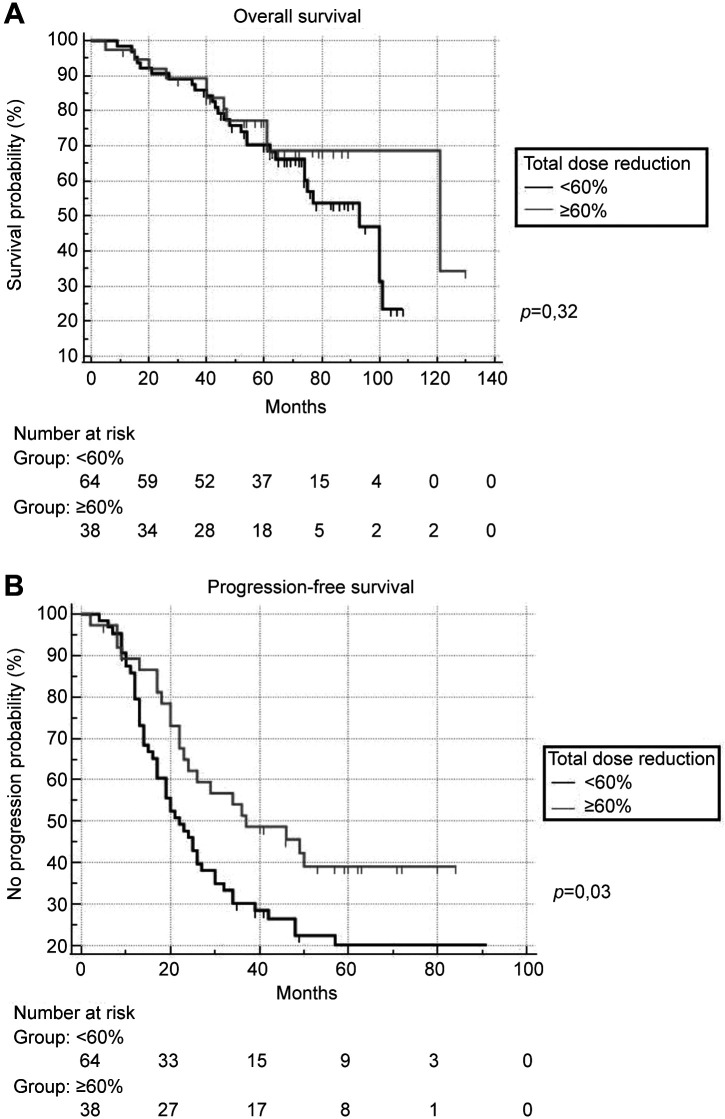

OS and PFS within the whole follow-up period are shown on the Kaplan-Meier curve. PFS was significantly longer in the ≥60% dose reduction group (p=0.03), whereas the OS was not significantly different between the groups (p=0.32) (Figure 2). The hazard ratio (HR) was evaluated using multivariate and univariate Cox regression. For OS, the HR of the ≥60% dose reduction group was 0.80 (p=0.80; 95% CI=0.155-4.160) for the multivariate analysis and 1.44 (p=0.32; 95% CI=0.699-2.977) for the univariate analysis compared with the <60% dose reduction group. For PFS, the HR of the ≥60% dose reduction group was 1.88 (p=0.02; 95% CI=1.111-3.182) for multivariate and 1.75 (p=0.03, 95% CI: 1.056-2.903) for univariate analyses.

Figure 2. Comparison of (A) overall survival and (B) progression-free survival between <60% dose reduction and ≥60% dose reduction groups.

Discussion

In this study, we showed that total dose reductions of 60% during first-line adjuvant chemotherapy did not negatively influence the OS and PFS in advanced epithelial ovarian cancer; furthermore, PFS was significantly longer in the ≥60% dose reduction group. The longer PFS may have been due to prolonged suppression of tumor cell proliferation. Both groups appeared to have a similar delivered dose intensity (p=0.69); however, the ≥60% dose reduction group underwent first-line adjuvant chemotherapy with a significantly longer duration (p=0.02) and more cycles of chemotherapy at a nearly significant level (p>0.05). This suggests that the length of chemotherapy may be more important for PFS than the dosage of chemotherapy agents. However, these factors were not enough to significantly influence the OS. This supports the completion of first-line chemotherapy with more cycles and lower intensity. However, the benefit of dose reduction on the PFS was insufficient to justify it because more cycles of chemotherapy can increase adverse effects, such as hypersensitivity to the chemotherapy agents and toxicity (15).

This study shows clinical value because studies that specify clinical factors related to the delay of duration and dose reduction of chemotherapy agents are rare in advanced epithelial ovarian cancer research. Unlike other recent studies (4,5), we showed successfully controlled clinical factors related to chemotherapy. The influence due to the delivered dose of chemotherapy agents, delay within duration, interval to initiation, and regimen treatment could be excluded. Both groups in this study also showed that additional treatments such as HIPEC, bevacizumab, PARP inhibitors, and pembrolizumab were controlled to an insignificant level.

We conducted subgroup analyses to evaluate the relationship between total dose reduction and survival outcomes; first, patients were divided into two groups based on 0% (not reduced group vs. reduced group), and second, patients were divided into two groups based on 30% (<30% vs. ≥30%). Whereas OS was not significantly different, PFS was significantly longer in two subgroups [>0%, N=57 (55.9%), p<0.05; ≥30%, N=46 (45.1%), p=0.04]. Another subgroup analysis was performed to determine which factors were significantly correlated with PFS; thus, all factors in Table I were included and analyzed by multiple linear regression. In all patients (N=102), suboptimal surgery, duration and total delay were significantly correlated (β=−0.27, p<0.01; β=0.35, p=0.01; β=−0.51, p<0.01). In the ≥60% dose reduction group (N=38), age, suboptimal surgery, and total delay were significantly correlated (β=−0.41, p<0.01; β=−0.47, p<0.01; β=−0.51, p<0.01), whereas no significant correlation was found in the <60% dose reduction group. Based on the p values in Table I, the total delay may have an important influence on PFS; we plan to study this further.

We searched a recent Cochrane study on the adverse effects of dose reduction on advanced ovarian cancer (4); this is a follow-up study of GOG-182 (16), a randomized controlled phase-III trial. The authors grouped patients who underwent dose reduction and protraction of chemotherapy in the dose modification group; however, a subgroup analysis for dose reduction was not conducted. Dose modification resulted in shorter OS and PFS over 10 years [adjusted HR=1.26, p=0.02, 95% CI=1.04-1.54 (OS); adjusted HR=1.43, p<0.01, 95% CI=1.19-1.72 (PFS)]. In this study, dose reduction was defined as a change of dose to 0.85 or less; however, the dose of carboplatin was determined with AUC 6; in the present study, we used AUC 5. In another recent study on advanced ovarian cancer, the authors evaluated the relationship between the RDI and OS. In that study, shorter OS was observed with RDI<85% (HR=1.94, p=0.03, 95% CI=1.09-3.46); however, the number of patients in the dose reduction group was not mentioned, and PFS was not evaluated (5).

We performed subgroup analyses to compare our results with the abovementioned studies despite many limitations. Of 134 patients with stage III and IV ovarian cancer, 26 were categorized as RDI <85% and analyzed using Kaplan-Meier survival and Cox regression analyses. No significant differences were found in OS and PFS in this subgroup by Kaplan-Meier survival analysis [p=0.39 (OS), p=0.20 (PFS)]. The differences were also not significant by Cox regression analysis [p=0.59 (OS), p=0.79 (PFS)].

This study has certain limitations. First, it was a retrospective study using data from a single center. Second, confounding factors, such as the patient performance status and the toxicity of chemotherapy agents, were not reviewed; thus, we could not determine the specific factors that resulted in the dose reductions. Third, we were unable to quantify the dose of additional medical interventions, such as HIPEC, bevacizumab, PARP inhibitor, and pembrolizumab. We could control the number who used those regimens or drugs, but their influence on the OS and PFS could not be evaluated thoroughly. Fourth, we could not analyze within a broad spectrum of dose reduction due to the small number of patients included in this study. There were too few patients with an 80% total dose reduction to evaluate appropriately.

In conclusion, an appropriate dose reduction by 60% during first-line adjuvant chemotherapy due to patients’ medical conditions does not negatively influence OS and PFS of patients with advanced epithelial ovarian cancer. Further studies should be conducted to determine specific factors influencing length of PFS.

Conflicts of Interest

The Authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Authors’ Contributions

DG HONG conceived of, and supervised, the study. J LEE performed analytic calculations. Both DG HONG and J LEE contributed to drafting of the manuscript. J LEE and JM KIM processed the clinical data. YH LEE designed the figures and revised the tables. GO CHONG helped supervise the study. All Authors discussed the results and contributed to the final manuscript.

References

- 1.Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, Bray F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(3):209–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Armstrong DK, Alvarez RD, Bakkum-Gamez JN, Barroilhet L, Behbakht K, Berchuck A, Chen LM, Cristea M, DeRosa M, Eisenhauer EL, Gershenson DM, Gray HJ, Grisham R, Hakam A, Jain A, Karam A, Konecny GE, Leath CA, Liu J, Mahdi H, Martin L, Matei D, McHale M, McLean K, Miller DS, O’Malley DM, Percac-Lima S, Ratner E, Remmenga SW, Vargas R, Werner TL, Zsiros E, Burns JL, Engh AM. Ovarian cancer, version 2.2020, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2021;19(2):191–226. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2021.0007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lawrie TA, Winter-Roach BA, Heus P, Kitchener HC. Adjuvant (post-surgery) chemotherapy for early stage epithelial ovarian cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(12):CD004706. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004706.pub5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Olawaiye AB, Java JJ, Krivak TC, Friedlander M, Mutch DG, Glaser G, Geller M, O’Malley DM, Wenham RM, Lee RB, Bodurka DC, Herzog TJ, Bookman MA. Corrigendum to “Does adjuvant chemotherapy dose modification have an impact on the outcome of patients diagnosed with advanced stage ovarian cancer? An NRG Oncology/Gynecologic Oncology Group study” [Gynecol. Oncol. 151 (2018) 18-23] Gynecol Oncol. 2019;152(1):220. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2018.10.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Denduluri N, Lyman GH, Wang Y, Morrow PK, Barron R, Patt D, Bhowmik D, Li X, Bhor M, Fox P, Dhanda R, Saravanan S, Jiao X, Garcia J, Crawford J. Chemotherapy dose intensity and overall survival among patients with advanced breast or ovarian cancer. Clin Breast Cancer. 2018;18(5):380–386. doi: 10.1016/j.clbc.2018.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Denduluri N, Patt DA, Wang Y, Bhor M, Li X, Favret AM, Morrow PK, Barron RL, Asmar L, Saravanan S, Li Y, Garcia J, Lyman GH. Dose delays, dose reductions, and relative dose intensity in patients with cancer who received adjuvant or neoadjuvant chemotherapy in community oncology practices. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2015;13(11):1383–1393. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2015.0166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fauci JM, Whitworth JM, Schneider KE, Subramaniam A, Zhang B, Frederick PJ, Kilgore LC, Straughn JM Jr. Prognostic significance of the relative dose intensity of chemotherapy in primary treatment of epithelial ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2011;122(3):532–535. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krukowski K, Nijboer CH, Huo X, Kavelaars A, Heijnen CJ. Prevention of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy by the small-molecule inhibitor pifithrin-μ. Pain. 2015;156(11):2184–2192. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sivakumaran T, Mileshkin L, Grant P, Na L, DeFazio A, Friedlander M, Obermair A, Webb PM, Au-Yeung G, OPAL Study Group Evaluating the impact of dose reductions and delays on progression-free survival in women with ovarian cancer treated with either three-weekly or dose-dense carboplatin and paclitaxel regimens in the national prospective OPAL cohort study. Gynecol Oncol. 2020;158(1):47–53. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2020.04.706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oneda E, Abeni C, Zanotti L, Zaina E, Bighè S, Zaniboni A. Chemotherapy-induced neurotoxicity in the treatment of gynecological cancers: State of art and an innovative approach for prevention. World J Clin Oncol. 2021;12(6):458–467. doi: 10.5306/wjco.v12.i6.458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Katsumata N, Yasuda M, Takahashi F, Isonishi S, Jobo T, Aoki D, Tsuda H, Sugiyama T, Kodama S, Kimura E, Ochiai K, Noda K, Japanese Gynecologic Oncology Group Dose-dense paclitaxel once a week in combination with carboplatin every 3 weeks for advanced ovarian cancer: a phase 3, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2009;374(9698):1331–1338. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61157-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bell J, Brady MF, Young RC, Lage J, Walker JL, Look KY, Rose GS, Spirtos NM, Gynecologic Oncology Group Randomized phase III trial of three versus six cycles of adjuvant carboplatin and paclitaxel in early stage epithelial ovarian carcinoma: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Gynecol Oncol. 2006;102(3):432–439. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2006.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Prat J, FIGO Committee on Gynecologic Oncology Abridged republication of FIGO’s staging classification for cancer of the ovary, fallopian tube, and peritoneum. Cancer. 2015;121(19):3452–3454. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Salani R, Axtell A, Gerardi M, Holschneider C, Bristow RE. Limited utility of conventional criteria for predicting unresectable disease in patients with advanced stage epithelial ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2008;108(2):271–275. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2007.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sliesoraitis S, Chikhale PJ. Carboplatin hypersensitivity. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2005;15(1):13–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1048-891x.2005.14401.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Copeland LJ, Bookman M, Trimble E, Gynecologic Oncology Group Protocol GOG 182-ICON5 Clinical trials of newer regimens for treating ovarian cancer: the rationale for Gynecologic Oncology Group Protocol GOG 182-ICON5. Gynecol Oncol. 2003;90(2 Pt 2):S1–S7. doi: 10.1016/s0090-8258(03)00337-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]