Abstract

A PCR method was developed by which to rapidly and accurately determine the rrn arrangement of Salmonella enterica serovars. Primers were designed to the genomic regions flanking each of the seven rrn operons. PCR analysis using combinations of these primers will distinguish each of the possible arrangements of the rrn skeleton.

Although it had long been assumed that large-scale rearrangements in the bacterial chromosome are extremely rare, it is now clear that the genome arrangement of many organisms varies from strain to strain due to inversions and transpositions of large DNA fragments (D. Hughes, Genome Biol. 1:0006.1- 0006.8 [http://genomebiology.com/2000./1/6/reviews/0006.1]). Many of these rearrangements appear to be the result of homologous recombination between chromosomal regions of homology. Inversions result from recombination between indirect repeats, while transpositions result from recombination between flanking direct repeats (6).

In many organisms, the multiple, homologous rrn operons serve as targets for chromosomal rearrangements (1, 5). The Escherichia coli and Salmonella genomes each have seven rrn operons, which code for rRNA. Each rrn operon is approximately 6.5 kb and consists of genes coding for the16S, 23S, and 5S rRNAs interrupted by a spacer region between the 16S and 23S genes. The sequences of the rrn genes are greater than 99.5% identical among the seven operons, while the sequences of the spacer region are variable in the different operons (3, 8). The rrn operons are located in noncontiguous sites centered around the chromosomal origin of replication (oriC) (4). These operons are all oriented such that they are transcribed in the same direction as the chromosome replication fork. The number and location of the rrn operons are highly conserved among these enteric bacteria (7).

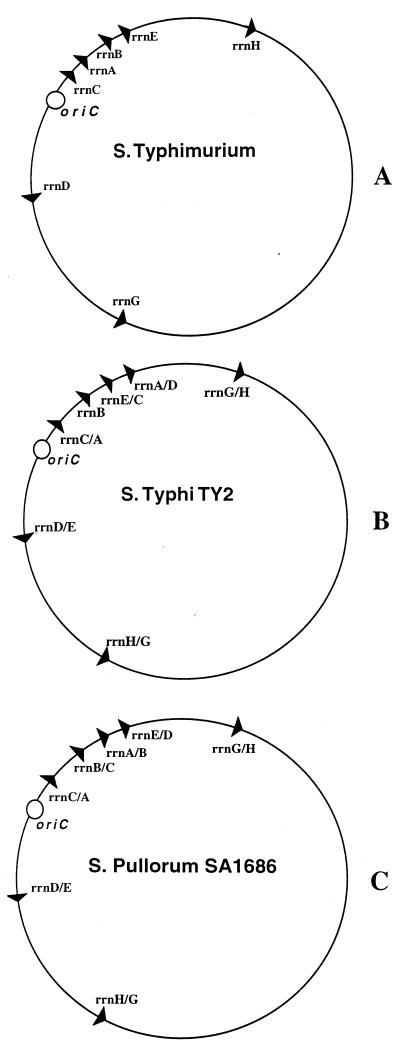

Liu and Sanderson (11, 12, 13) showed that certain serovars of Salmonella enterica have large chromosomal rearrangements between regions flanked by the rrn operons. Analysis of multiple serovars using partial digests of I-CeuI, an endonuclease specific for the 23S region of rrn operons, followed by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE), revealed that S. enterica serovars which are adapted to a particular host, such as the serovars Paratyphi, Typhi, and Gallinarum, exhibit multiple chromosomal arrangements due to recombination between rrn operons. These rearrangements include chromosomal inversions and transpositions of regions flanked by rrn operons (Fig. 1A and B). Many of the rearrangements result in nearly symmetrical inversions relative to oriC; however, transpositions may disrupt this symmetry.

FIG. 1.

The rrn skeletons of three serovars of S. enterica. (A) The serovar Typhimurium LT2 genome has the same arrangement as those of E. coli K-12 and other broad-host-range Salmonella pathogens. (B) Serovar Typhi TY2 has multiple rearrangements indicating recombination events at rrn operons. (C) Serovar Pullorum SA1686 also has a rearranged chromosome relative to that of serovar Typhimurium. The serovar Pullorum rrn skeleton was derived from the results shown in Fig. 2C. Sizes of rearranged DNA fragments vary from approximately 44 kb (about 1% of the chromosome) to 2,300 kb (nearly 50% of the chromosome).

In contrast, other serovars of the same species have remarkably stable genomes. By using the same PFGE method, Liu and Sanderson (10, 13) observed that all of the S. enterica serovars which could infect a broad range of hosts, such as serovars Typhimurium and Enteritidis, maintained a conserved genome and that their “rrn skeletons” are similar to that of E. coli K-12.

Determination of genomic arrangements has many applications in microbiology, including the analysis of population dynamics and strain typing. However, because partial digests can be unpredictable, PFGE is time consuming and requires special equipment, and analysis of the data can be tedious, we developed a simpler, rapid method of determining the rrn skeleton by using PCR. The PCR method takes advantage of genome sequence data which was unavailable when the PFGE method was designed. The PCR method also reveals the orientation of DNA between the rrn operons, whereas the PFGE method does not always allow such a distinction. Furthermore, the PCR technique always distinguishes each of the seven rrn operons while PFGE may not be sufficient to discern particular fragments if they are similar in size (13). We demonstrate the utility of the PCR approach for mapping of the rrn skeletons of multiple Salmonella serovars.

The sequences of the primers used in this study and their locations relative to proximal rrn operons are shown in Tables 1 and 2. Primers were designed based upon the sequence of DNA flanking each of the seven rrn operons in serovar Typhi. Fourteen 25-mer sequences which yielded no hairpins and minimal duplexes were chosen as primers. In order to rapidly screen all possible rrn arrangements, 49 pairs of oligonucleotides were used. Primers were resuspended to a concentration of 1 mM in Tris-EDTA buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], 1 mM EDTA) and stored at −20°C. Working stocks of 10 μM oligonucleotides in sterile distilled water were used.

TABLE 1.

Oligonucleotide primers and their genomic locations relative to rrn operons

| Primer | Sequencea | Location |

|---|---|---|

| HemG | TCCGTGGCGACTTGACTACTGTGCC | 5′ rrnA |

| MobB | TGCCTTCATTTTGCGGTGGTTAGAG | 3′ rrnA |

| MurI | GCGTCGGTGGATTGTCGGTCTATGA | 5′ rrnB |

| MurB | CCAGGCGCTCAGTAGTTGTTGTTCG | 3′ rrnB |

| YieP | GCTCCAGGCTAATACGCATCACCAG | 5′ rrnC |

| YifA | GCTGTTAGGGCACTTCACTTTGGCG | 3′ rrnC |

| YrdA | GGGTTGCCGTGTGGATTGGATGGAG | 5′ rrnD |

| AcrF | CGCAGTAGGCACAGGGGTTATGGGG | 3′ rrnD |

| PurH | CGATAGGGGCGATGTGGTGCTGTTC | 5′ rrnE |

| MetA | GGAAATCGGCATAGCGTGAGTGTGG | 3′ rrnE |

| ClpB | CCGTCGCCCTTATTCCGTCATCTTG | 5′ rrnG |

| KgtP | GCCATAACGCCACAACCGCCAGCAC | 3′ rrnG |

| YaeD | CCATCCGCAGGGCAGCATAGAAGAG | 5′ rrnH |

| YafB | CGGCAATAGCCTTTTCCATCAACGG | 3′ rrnH |

Primer sequences were derived from the serovar Typhi genome sequence determined at the Sanger Centre (www.sanger.ac.uk/Projects/S_typhi/).

TABLE 2.

Primer sets for determining the rrn skeleton

| No. | Primers | rrna |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | YrdA, KgtP | rrnD/G |

| 2 | YrdA, YifA | rrnD/C |

| 3 | YrdA, MobB | rrnD/A |

| 4 | YrdA, MurB | rrnD/B |

| 5 | YrdA, MetA | rrnD/E |

| 6 | YrdA, YafB | rrnD/H |

| 7 | ClpB, KgtP | rrnG |

| 8 | ClpB, YifA | rrnG/C |

| 9 | ClpB, MobB | rrnG/A |

| 10 | ClpB, MurB | rrnG/B |

| 11 | ClpB, MetA | rrnG/E |

| 12 | YieP, MobB | rrnC/A |

| 13 | YieP, MurB | rrnC/B |

| 14 | YieP, MetA | rrnC/E |

| 15 | YieP, YafB | rrnC/H |

| 16 | YieP, KgtP | rrnC/G |

| 17 | HemG, MobB | rrnA |

| 18 | HemG, MetA | rrnA/E |

| 19 | HemG, YafB | rrnA/H |

| 20 | HemG, KgtP | rrnA/G |

| 21 | HemG, YifA | rrnA/C |

| 22 | MurI, YafB | rrnB/H |

| 23 | MurI, KgtP | rrnB/G |

| 24 | MurI, YifA | rrnB/C |

| 25 | MurI, MobB | rrnB/A |

| 26 | MurI, MurB | rrnB |

| 27 | PurH, MetA | rrnE |

| 28 | PurH, YafB | rrnE/H |

| 29 | PurH, KgtP | rrnE/G |

| 30 | PurH, YifA | rrnE/C |

| 31 | PurH, MurB | rrnE/B |

| 32 | YaeD, YafB | rrnH |

| 33 | YaeD, YifA | rrnH/C |

| 34 | YaeD, MobB | rrnH/A |

| 35 | YaeD, MurB | rrnH/B |

| 36 | YaeD, MetA | rrnH/E |

| 37 | YaeD, KgtP | rrnH/G |

| 38 | ClpB, YafB | rrnG/H |

| 39 | YieP, YifA | rrnC |

| 40 | HemG, MurB | rrnA/B |

| 41 | MobB, PurH | rrnE/A |

| 42 | MurI, MetA | rrnB/E |

| 43 | YrdA, AcrF | rrnD |

| 44 | ClpB, AcrF | rrnG/D |

| 45 | YieP, AcrF | rrnC/D |

| 46 | HemG, AcrF | rrnA/D |

| 47 | MurI, AcrF | rrnB/D |

| 48 | PurH, AcrF | rrnE/D |

| 49 | YaeD, AcrF | rrnH/D |

Structure of the rrn operon which yields a PCR product from the indicated primer set. For example, rrnA/E represents a hybrid rrn operon with the 5′ end of rrnA and the 3′ end of rrnE.

Bacteria were grown overnight with aeration at 37°C in Luria-Bertani medium (2). The strains used included S. enterica serovar Typhimurium LT2, serovar Typhi TY2, and serovar Pullorum SA1686. Chromosomal DNA was isolated from stationary-phase bacteria from overnight cultures. DNA was purified by using a Wizard Genomic DNA Purification Kit (Promega Corp., Madison, Wis.) in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions.

The reaction mixtures initially consisted of 1 μl of template DNA, 2 μl of each primer pair stock, 1 μl of a 10 mM working stock of deoxyribonucleotides, and 16 μl of sterile distilled water in a HotStart Storage and Reaction Tube (Molecular BioProducts, Inc., San Diego, Calif.). The reaction tubes were heated to 90°C for 30 s to melt the wax pellet. Upon cooling to room temperature, the reactions were initiated with the addition of 5 μl of 10× PCR buffer, 1.5 μl of 50 mM MgCl2, 0.25 μl of Taq DNA polymerase (5 U/μl), and 23.25 μl of sterile distilled water.

The tubes were heated to 90°C for 30 s to allow the wax to melt, allowing the top and bottom layers to mix. DNA was then denatured by heating to 94°C for 30 s, followed by annealing and elongation at 70°C for 7.5 min. This cycle of denaturation, annealing, and elongation was repeated for a total of 30 cycles. Upon reaction completion,10 μl of the product was analyzed by electrophoresis on a 0.8% agarose gel and visualized with ethidium bromide (14).

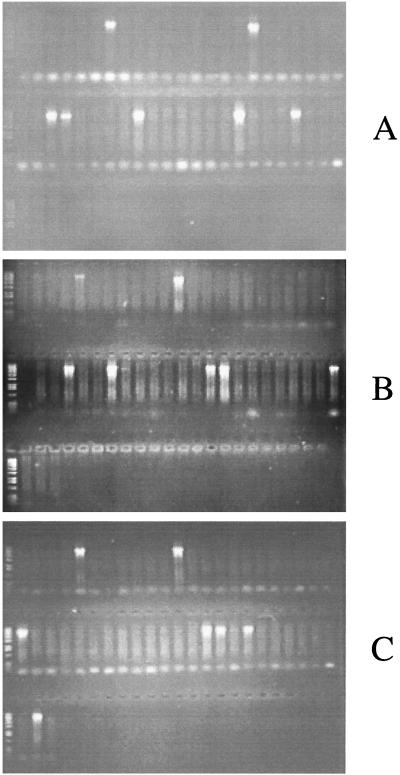

The rrn skeletons of strains of two of the S. enterica serovars have been previously mapped via the I-CeuI and PFGE technique, i.e., serovar Typhimurium LT2 (9) and serovar Typhi TY2 (12). The rrn arrangement of a strain of the third serovar, Pullorum SA1686, had not yet been determined. We used the PCR assay to confirm the results obtained for serovars Typhi and Typhimurium and to discern the arrangement of serovar Pullorum SA1686. The results for each of the three serovars tested are shown in Fig. 2. Each lane represents a different primer set. Note that each serovar yields seven bands of approximately 7 kb. Evaluation of these results yields the rrn skeleton of each strain. Figure 1A and B illustrate the results for strains LT2 and TY2, confirming the chromosomal arrangements that Liu and Sanderson previously found by using PFGE (9, 12). The arrangement of previously uncharacterized serovar Pullorum strain SA1686 is shown in Fig. 1C. These results indicate the rrn skeleton is rearranged relative to the conserved rrn arrangement of serovar Typhimurium.

FIG. 2.

PCR analysis of the rrn skeletons of S. enterica serovars. The three gels show the results obtained with the 49 primer sets for serovars Typhimurium LT2 (A), Typhi TY2 (B), and Pullorum SA1686 (C). Each lane shows the results for a single primer set, with the 49 primer sets loaded in sequential order from left to right and top to bottom. The positions correspond to the numbers shown in Table 2. Note that on each gel, 7 of the 49 lanes show bands of approximately 7 kb. The rrn skeleton can be inferred from those primer pairs that yield a PCR product.

In addition to the serovars shown here, we have used this method to determine the rrn skeletons of other Salmonella serovars, including serovar Dublin SL2260 and serovar Enteritidis LK5, which infect a variety of hosts, and serovar Gallinarum SSM1617, which is a fowl-specific pathogen (data not shown). For each serovar, we identified seven bands of the appropriate size. The results indicate that both serovars Enteritidis and Dublin have a genome arrangement like that of serovar Typhimurium, whereas the genome of serovar Gallinarum is rearranged relative to that of serovar Typhimurium.

In summary, the chromosomal gene order in many bacterial species can vary greatly, even among different strains of the same species. These large-scale genomic rearrangements are often the result of recombination between the rrn operons. In S. enterica, serovars which have multiple genomic rearrangements have very specific pathogenic host ranges, while serovars with broad host ranges have very stable chromosomes. Understanding how these rearrangements occur and why they are tolerated may provide insights into host specificity. Based upon the results, it is clear that the rrn skeletons of most, if not all, Salmonella serovars can be quickly and easily determined by the PCR method described here. Given the conserved structure of the rrn operon, it is also clear that this general approach could be applied to many other species of Bacteria and Archaea. The only requirement is the availability of genome sequence data to facilitate design of the primers.

Acknowledgments

We thank Lionello Bossi at CNRS, Gif-sur-Yvette, France, and Steve Libby at North Carolina State University for Salmonella strains. We thank Kenneth Sanderson at the University of Calgary and Robert Edwards at the University of Tennessee in Memphis for helpful discussions and advice. We thank Alison Lee for assistance in performing PCRs. We gratefully acknowledge the Sanger Centre for access to the “Salmonella typhi ” genome sequence used to construct the primers.

This work was supported by grants from the Illinois Council on Food and Agricultural Research (C-FAR 991-58-4) and the U.S. Department of Agriculture (AG 2001-35201-09950) to S.M.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anderson R P, Roth J R. Gene duplication in bacteria: alteration of gene dosage by sister-chromosome exchanges. Cold Spring Harbor Symp Quant Biol. 1979;43:1083–1087. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1979.043.01.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bertani G. Studies on lysogenesis. I. The mode of phage liberation by lysogenic E. coli. J Bacteriol. 1951;62:293–300. doi: 10.1128/jb.62.3.293-300.1951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Christensen H, Moller P L, Vogensen F K, Olsen J E. Sequence variation of the 16S to 23S rRNA spacer region in Salmonella enterica. Res Microbiol. 2000;151:37–42. doi: 10.1016/s0923-2508(00)00129-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ellwood M, Nomura M. Chromosomal location of the genes for rRNA in Escherichia coli K-12. J Bacteriol. 1982;149:458–468. doi: 10.1128/jb.149.2.458-468.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hill C W, Harvey S, Gray J A. Recombination between rRNA genes in Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium. In: Drlica K, Riley M, editors. The bacterial chromosome. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1990. pp. 335–340. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hughes D. Impact of homologous recombination on genome organization and stability. In: Charlebois R L, editor. Organization of the prokaryotic genome. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1999. pp. 109–128. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krawiec S, Riley M. Organization of the bacterial genome. Microbiol Rev. 1990;54:502–539. doi: 10.1128/mr.54.4.502-539.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lehner A F, Harvey S, Hill C W. Mapping and spacer identification of rRNA operons of Salmonella typhimurium. J Bacteriol. 1984;160:682–686. doi: 10.1128/jb.160.2.682-686.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu S-L, Hessel A, Sanderson K. Genomic mapping with I-CeuI, an intron-encoded endonuclease specific for genes for ribosomal RNA, in Salmonella spp., Escherichia coli, and other bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:6874–6878. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.14.6874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu S-L, Sanderson K. I-CeuI reveals conservation of the genome of independent strains of Salmonella typhimurium. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:3355–3357. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.11.3355-3357.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu S-L, Sanderson K. The chromosome of Salmonella paratyphi A is inverted by recombination between rrnH and rrnG. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:6585–6592. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.22.6585-6592.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu S-L, Sanderson K. Highly plastic chromosomal organization in Salmonella typhi. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:10303–10308. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.19.10303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu S-L, Sanderson K. Homologous recombination between rrn operons rearranges the chromosome in host-specialized species of Salmonella. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1998;164:275–281. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1998.tb13098.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maloy S, Stewart V, Taylor R. Genetic analysis of pathogenic bacteria: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]