Abstract

Borrelia miyamotoi is an underdiagnosed cause of tick-borne illness in endemic regions and, in rare cases, causes neurological disease in immunocompetent patients. Here, we present a case of serologically confirmed Borrelia miyamotoi meningoencephalitis in an otherwise healthy patient who rapidly improved following initiation of antibiotic therapy.

Keywords: Borrelia, meningoencephalitis, miyamotoi

Diagnosis of culture-negative meningoencephalitis remains a challenge; a causative organism is not identified in 30%–60% of cases [1, 2]. Tick-borne zoonoses, including those caused by spirochetes in the Borrelia genus, are an important cause of potentially treatable meningoencephalitis in endemic regions [3]. Although B. burgdorferi remains the most common spirochetal cause of tick-transmitted central nervous system (CNS) infection, the relapsing fever spirochetes, including B. miyamotoi, have been reported to cause meningoencephalitis and should be considered in the appropriate epidemiologic setting. We report a case of meningoencephalitis due to B. miyamotoi in an immunocompetent host living in the Northeastern United States.

CASE

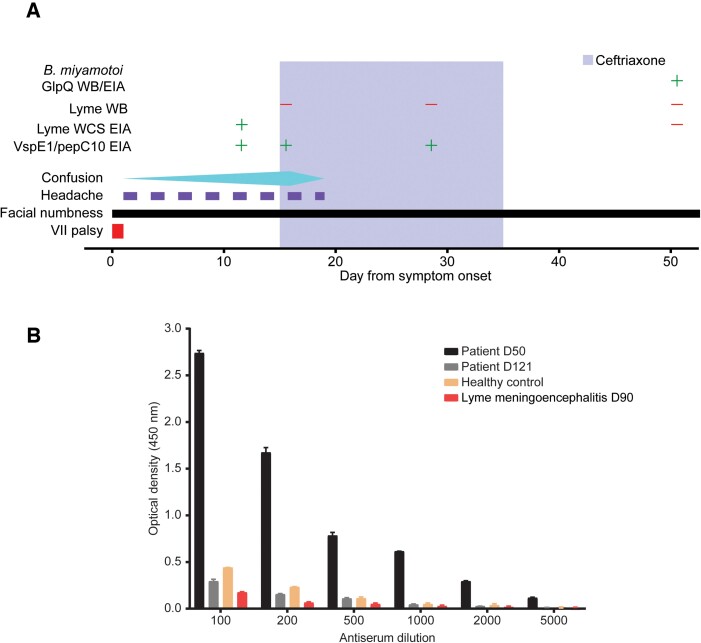

A 73-year-old male Connecticut resident was referred to our hospital in the summer of 2021 for a 16-day history of confusion and intermittent headaches (Figure 1A). His medical history included only hypertension. He did not take any medications. He was an avid gardener and had noted tick bites in the past, but none in the weeks before presentation. He had not traveled outside of the Northeastern United States in several years. His symptoms began abruptly with right-sided facial droop and associated numbness, confusion, and word-finding difficulties (Figure 1A, day 0). At that time, he underwent evaluation at another hospital where a noncontrast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan of the brain showed no evidence for acute ischemia or intracranial hemorrhage, and electroencephalography showed no seizure activity. His symptoms, which had improved, were attributed to a transient ischemic attack, and he was discharged to home with instructions to take aspirin for stroke prevention.

Figure 1.

Case timeline and serum antibody testing. A, Clinical course of a 73-year-old man with Borrelia miyamotoi encephalitis. The timeline below begins with the onset of symptoms, through hospital admission, antibiotic treatment, and recovery. Facial numbness was the only symptom that persisted at the 6-month follow-up visit (not shown). Test results for Borrelia burgdorferi EIAs and WB are shown. The antigen used in the B. burgdorferi EIA was B. burgdorferi WCS. B, EIA testing for antibodies against recombinant GlpQ in serum from the patient at day 50 (black bars) and day 90 (gray bars) after symptom onset is compared with an age-matched healthy control (orange bars) and an age-matched patient control who had recent B. burgdorferi meningoencephalitis. Abbreviations: EIA, enzyme-linked immunoassay; WB, Western blot; WCS, whole-cell sonicate.

Over the next 2 weeks, he continued to feel numbness in his right face and developed worsening confusion, intermittent headaches, and excessive fatigue; he was afebrile throughout this time (Figure 1A). Twelve days before admission (day 3 since symptom onset), he was evaluated in the emergency department of the other hospital and underwent a workup that included urinalysis, blood electrolyte measurement, and cardiac monitoring. These tests revealed no evidence for urinary tract infection or cardiac arrythmia. Focal neurological deficits were not identified. Four days before admission (day 11 since symptom onset) he returned to the emergency department again and underwent workup including complete blood count and serum testing for antibodies to Borrelia burgdorferi, the causative agent of Lyme disease, with modified 2-tier testing (MTTT; ZEUS Scientific [4]). The initial enzyme immunoassay (EIA) and the reflex immunoglobulin G/M (IgG/IgM) EIA were positive (Figure 1A). Fifteen days after symptom onset, he was referred to our hospital for further treatment.

The patient was disoriented on admission but without meningismus, and his neurological exam was without any focal deficits. He was afebrile. An MRI of the brain with contrast showed no evidence for acute ischemia, intracranial hemorrhage, or demyelination. Blood tests revealed a normal peripheral blood leukocyte count and normal liver function tests. Serum polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing for Anaplasma phagocytophilum and blood smear for Babesia microti were negative. Serum testing for HIV (fourth-generation antibody/antigen test) and Treponema pallidum–specific antibodies was negative. Other blood laboratory test results are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Laboratory Blood Data

| Variable | Reference Range, Adults | 15 Days Before Presentation, Other Hospital Emergency Room | 12 Days Before Presentation, Other Hospital Emergency Room | 4 Days Before Presentation, Other Hospital Emergency Room | On Admission, This Hospital |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | 12.0–18.0 | 15.6 | 15.6 | 15.9 | 15.8 |

| Hematocrit, % | 37.0–52.0 | 45.5 | 45.6 | 45.0 | 45.7 |

| WBC, ×1000/μL | 4.0–10.0 | 7.9 | 7.6 | 7.5 | 5.1 |

| Platelets, ×1000/μL | 140–440 | 165 | 173 | 193 | 188 |

| AST, U/L | 10–35 | 24 | |||

| ALT, U/L | 9–59 | 16 | |||

| Alkaline phosphatase, U/L | 9–122 | 54 | |||

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 0.40–1.30 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.94 |

| Blood microbiological tests | |||||

| Cryptococcal, Ag | Negative | Negative | |||

| T. pallidum, Ab | Nonreactive | Nonreactive | |||

| HIV, Ab/Ag | Negative | Negative | |||

| A. phagocytophilum, PCR | Not detected | Not detected | |||

| B. burgdorferi, Ab | Negative | IgG/IgM positive (EIA) | IgG/IgM positive (EIA), Western blot negative | ||

| Babesia smear | Negative | Negative |

Abbreviations: Ab, antibody; Ag, antigen; ALT, alanine transaminase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; EIA, enzyme immunoassay; IgG, immunoglobulin G; IgM, immunoglobulin M; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; WBC, white blood cell count.

A lumbar puncture was performed. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis demonstrated 50 white blood cells/μL (92% lymphocytes), 199.7 mg/dL protein, and a CSF/serum glucose ratio of 0.47. CSF PCR for varicella zoster virus (VZV), herpes simplex virus (HSV), cytomegalovirus (CMV), and B. burgdorferi were all negative, as were CSF antibody (EIA) tests for B. burgdorferi, Powassan virus, West Nile virus, and Jamestown Canyon virus. Other CSF laboratory tests results are shown in Table 2. On day 15, B. burgdorferi serum antibody testing was repeated with standard 2-tiered testing (STTT). The screening EIA was positive, but the reflex Western blot (WB) was negative for both IgM and IgG antibodies (Figure 1A).

Table 2.

Cerebrospinal Fluid Data

| Variable | Reference Range, Adults | On Admission, This Hospital |

|---|---|---|

| Hematology, tube 1 | ||

| RBC, cells/μL | 199 | |

| WBC, cells/μL | <6 | 50 |

| Granulocytes, % | 1 | |

| Lymphocytes, % | 92 | |

| Monocytes, % | 7 | |

| Hematology, tube 4 | ||

| RBC, cells/μL | 13 | |

| WBC, cells/μL | <6 | 73 |

| Granulocytes, % | 0 | |

| Lymphocytes, % | 95 | |

| Monocytes, % | 5 | |

| Glucose, mg/dL | 40–70 | 59 |

| Protein, mg/dL | 15.0–45.0 | 199.7 |

| Albumin, mg/dL | 10.0–30.0 | 144.8 |

| CSF microbiological tests | ||

| CSF culture gram stain | 2+ WBCs, no organisms seen, no growth | |

| VZV, PCR | Not detected | Not detected |

| HSV, PCR | Not detected | Not detected |

| CMV, PCR | Not detected | Not detected |

| B. burgdorferi, PCR | Not detected | Not detected |

| B. burgdorferi, Ab, IgG, and IgMa | Negative | Negative |

| West Nile virus, Ab, IgG, and IgMa | Negative | Negative |

| Powassan virus, Ab, IgMa,b | Negative | Negative |

| Jamestown Canyon virus, Ab, IgMa,b | Negative | Negative |

Abbreviations: Ab, antibody; Ag, antigen; CMV, cytomegalovirus; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; HSV, herpes simplex virus; IgG, immunoglobulin G; IgM, immunoglobulin M; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; RBC, red blood cell; VZV, varicella zoster virus; WBC, white blood cell.

B. burgdorferi, West Nile virus, Powassan virus, and Jamestown Canyon virus antibody testing was all done via enzyme immunoassay.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention assay.

The patient was empirically treated with intravenous ceftriaxone for treatment of presumed Lyme meningoencephalitis, and his mental status rapidly improved. He was discharged to home on day 19 to complete 3 weeks of ceftriaxone. He was seen again on day 28, at which point B. burgdorferi serum antibody was again negative by WB (Figure 1A), prompting consideration of alternative causative pathogens, including Borrelia miyamotoi. Stored serum and CSF from the initial hospitalization were not available for testing; therefore, blood was obtained at follow-up on day 50 for further testing. Serum from day 50 was tested in a research laboratory for GlpQ antibodies using recombinant GlpQ EIA (Figure 1C) and GlpQ WB, as previously described (Supplementary Figure 1) [5]. GlpQ is an immunogenic protein that is produced by B. miyamotoi and other relapsing fever Borrelia species, but not B. burgdorferi [6]. Serum from day 50 was positive for GlpQ antibodies and repeat serological testing on day 121, demonstrated decreasing GlpQ antibody titers, consistent with B. miyamotoi convalescence (Figure 1C). B. burgdorferi antibodies were again negative by EIA and WB on day 50 and day 112. The patient noted a nearly full neurological recovery on day 28, with only residual intermittent right facial numbness. Upon follow-up 6 months later, he reported a persistent and intermittent right facial numbness and tingling.

DISCUSSION

Borrelia miyamotoi, a spirochete of the relapsing fever family, is a recently discovered cause of febrile illness and meningoencephalitis in endemic regions [7]. Like Lyme disease, B. miyamotoi is transmitted by Ixodes ticks and is endemic in New England. A recent study found a seroprevalence of 2.8% for B. miyamotoi in this region, compared with 11% for B. burgdorferi [8]. Although B. miyamotoi was first identified in ticks in 1995, its clinical significance was not established until 2011, when 46 of 302 Russian patients from Yekaterinburg City who presented with nonspecific febrile illness and suspicion for tick-borne disease were confirmed to have B. miyamotoi disease (BMD) by PCR of serum [9]. Cases have since been reported in Europe, Japan, and North America. Lyme disease and other Ixodes tick-borne diseases have markedly increased in number and expanded geographically, and it is likely that human B. miyamotoi infection will eventually be found wherever Lyme disease is endemic. Because B. miyamotoi is endemic in New England and can cause relapsing fever and meningoencephalitis, it is important that clinicians recognize the spectrum of B. miyamotoi disease and challenges in diagnosis.

Our patient, who resided in an area endemic for both B. burgdorferi and B. miyamotoi, presented with facial palsy and disorientation and CSF parameters consistent with neuroborreliosis. His symptoms of encephalopathy improved rapidly with anti-Borrelia antibiotic treatment, and subsequent serologic testing failed to confirm a diagnosis of Lyme disease but was consistent with a diagnosis of B. miyamotoi infection. All previously reported cases of B. miyamotoi meningoencephalitis due to B. miyamotoi were confirmed with PCR testing on serum and/or CSF, whereas confirmation of the diagnosis in our case was accomplished only with serologic testing in addition to consistent epidemiological and clinical features. Anti–B. miyamotoi antibody decreased markedly from 2 to 4 months after diagnosis, consistent with recent acquisition of B. miyamotoi infection.

There have been 6 previously reported cases of B. miyamotoi CNS disease, with features as listed in Table 3. While confusion, meningoencephalitis, and facial nerve palsy have been reported in immunocompromised patients with B. miyamotoi disease, meningismus was the sole neurological symptom in the only other confirmed case of B. miyamotoi CNS disease in an immunocompetent patient [10]. B. miyamotoi meningoencephalitis cases are characterized by a long duration of illness, with a range of 1 week to 9 months of symptoms before diagnosis [10–14]. All reported cases to date have occurred in adults over age 50, and most (5 of 6) occurred in individuals receiving B-cell-depleting treatment with rituximab. Our case therefore highlights the need to include B. miyamotoi disease in the differential diagnosis for any patient who presents with acute onset, progressive encephalopathy with culture-negative CSF in B. miyamotoi–endemic regions, not just those who are immunocompromised.

Table 3.

Previously Reported Cases of B. miyamoti CNS Diseases

| Case | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Citation | Gugliotta et al., 2013 | Hovius et al., 2013 | Boden et al., 2016 | Henningsson et al., 2019 | Henningsson et al., 2019 | Mukerji et al., 2020 | Gandhi et al., 2022 (this case) |

| Location | New Jersey, USA | Netherlands | Germany | Sweden | Sweden | Massachusetts, USA | Connecticut, USA |

| Demographics | 80F | 70M | 74F | 53F | 66F | 63M | 73M |

| predisposing illness | Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma | Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma | Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma | None | Rheumatoid arthritis | Primary membranous nephropathy | None |

| Immunosuppression | R-CHOP; maintenance rituximab | R-CHOP; splenectomy | R-CHOP; maintenance rituximab | None | Methotrexate, rituximab | R-CHOP | None |

| Clinical symptoms and signs | Confusion | Cognitive slowing | Headache | Headache | Headache | Headache | Headache |

| Hearing loss | Memory deficits | Neck stiffness | Neck stiffness | Fatigue | Photophobia, sonophobia | Confusion | |

| Ataxia | Ataxia | Dizziness, vomiting | Fever | Fever | Word-finding difficulties | Fatigue | |

| Weight loss | Hearing loss | Neck stiffness | Facial droop | ||||

| Weight loss | Facial droop | Uveitis, vitritis | |||||

| Uveitis, iritis, vitritis | |||||||

| Duration from onset of illness to hospitalization | 4 mo | 2.5 mo | 5 d | 1 wk | 9 mo | 3 mo | 16 d |

| Treatment | IV ceftriaxone initiated (2 g dose: Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction) switched to IV penicillin G (24 MU/d for 30 d) | IV ceftriaxone (2 g 1x/d for 2 wk) | IV ceftriaxone (2 g 1x/d for 3 wk) | IV ampicillin; oral doxycycline (200 mg 2x/d for 14 d) | Oral doxycycline (200 mg 2x/d for 14 d) | IV ceftriaxone, ampicillin, vancomycin initiated; IV ceftriaxone 4 wk—switch to doxycycline due to facial rash development | IV ceftriaxone (2 g 1x/d for 3 wk) |

| Outcome | Full recovery | Full recovery | Full recovery | Full recovery | Full recovery | Full recovery | Persistent facial numbness; otherwise full recovery |

| CSF findings | |||||||

| Leukocytes, cells/μL (normal <5 cells/μL) | 65 | 388 | 70 | 321 | 331 | 146 | 50 |

| 70% lymphocytes, 23% PMN, 6% monocyte | 60% mononuclear | 61% lymphocyte, 32% PMN, 7% monocyte | 86% mononuclear | 82% mononuclear | 25% lymphocyte, 50% PMN, 25% monocyte | 92% lymphocytes, 1% PMN, 7% monocytes | |

| Protein level, mg/dL | >300 | NA | 171 | NA | NA | 358 | 200 |

| Glucose, mmol/L | 1.8 | 1.6 | 2.41 | NA | NA | 2.1 | 3.3 |

| CSF microscopy | Spirochetes visible with Giemsa stain | Spirochetes visible with dark-field microscopy | Spirochetes visible after acridin orange staining | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| B. burgdorferi testing | |||||||

| Serum | ELISA IgM, IgA, IgG: negative | C6-IFA weak positive; WB IgG: inconclusive; WB IgM: negative | CLIA: negative | CLIA: negative; ELISA IgM/IgG: negative | CLIA: negative; ELISA IgM/IgG: negative | ELISA: negative | ELISA: IgM/IgG positive; WB: negative |

| CSF | ELISA IgM, IgA, IgG: negative | C6-IFA: negative | CLIA: negative | CLIA IgM positive | CLIA IgM positive | ELISA: negative | ELISA IgM/IgG: negative; PCR negative |

| B. miyamotoi diagnosis | |||||||

| Serum | NA | PCR (flagellin) | PCR negative | PCR+ (flagellin); GlpQ IgG+, IgM+ | PCR+ (flagellin); GlpQ IgG-, IgM+ | GlpQ IgG+, IgM- | GlpQ IgG+ |

| CSF | PCR+ (flagellin and glpq) | PCR+ (flagellin, glpq, and p66) | PCR+ (panbacterial 16S rRNA) | PCR+ (flagellin, glpq, and p66) | PCR+ (flagellin, glpq, and p66) | PCR+ (glpQ) | NA |

Normal CSF protein range: 15–45 mg/dL. Normal CSF glucose range: 2.2–4.2 mmol/L.

Abbreviations: CLIA, chemiluminescent immunoassay (LIAISON); CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunoassay; IFA, immunofluorescence assay; IgG, immunoglobulin G; IgM, immunoglobulin M; IV, intravenous; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; PMN, polymorphonuclear leukocytes; R-CHOP, rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone; WB, Western blot.

B. miyamotoi disease remains a challenging diagnosis, as there are no FDA-approved tests for the diagnosis of B. miyamotoi and availability of testing is limited. Serology can help support or confirm the diagnosis; however, there are several important caveats to serological-based testing. Serologic responses may not be evident during the acute phase of illness, and thus rising antibody titers may be required to establish a diagnosis [15, 16]. The majority of patients with reported B. miyamotoi CNS disease have been treated with B-cell-depleting immunotherapies (eg, rituximab) that impair antibody production and thus may interfere with serodiagnosis. Studies in Lyme disease demonstrate that the serological response to B. burgdorferi may be delayed by the use of antimicrobials [17]; whether this is also a feature of B. miyamotoi infection is unknown. Glp, the main immunogenic antigen targeted in B. miyamotoi serological testing to date, is also present in other relapsing fever spirochetes, which will impact interpretation of this test in geographical settings where B. miyamotoi and other relapsing fever spirochetes coexist [18]. New B. miyamotoi immunoreactive antigens have been developed and can improve antibody assay sensitivity and specificity [19]. Newer diagnostic testing approaches using metagenomic next-generation sequencing may provide a useful alternative to serodiagnosis and aid in the detection of several tick-borne zoonoses, including those caused by Borrelia [20, 21].

While our patient developed anti-GlpQ antibodies, he also tested positive for Lyme disease by EIA on the MTTT, raising the question of whether he was coinfected with B. burgdorferi. However, repeated negative Lyme antibody testing by Western blot up to 16 weeks after symptom onset showed that the patient did not seroconvert and therefore experienced a single infection with B. miyamotoi. A positive serological result on B. burgdorferi EIA can be explained by the presence C6 peptide sequence within the VlsE antigen utilized in the EIA. This protein sequence has been shown to cross-react to B. miyamotoi, most likely due to homology with B. miyamotoi variable large proteins [22–24]. Our case highlights the importance of considering B. miyamotoi in clinically suspicious cases of meningoencephalitis, including when B. burgdorferi EIA results are positive but the WB is negative. This case also emphasizes the limitation of relying on EIA alone—as in the MTTT—to distinguish between BMD and Lyme disease.

CONCLUSIONS

B. miyamotoi can cause meningoencephalitis in immunocompetent patients. B. miyamotoi should be suspected in cases with clinical symptoms consistent with acute or subacute meningoencephalitis in endemic regions.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at Open Forum Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial support. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health grants T32AI007517-21A1 to S.G. and K23MH118999 to S.F.F. and by the Llura A. Gund Laboratory for Vector-borne Diseases and the Gordon and Llura Gund Foundation (P.J.K.).

Potential conflicts of interest. The authors: no reported conflicts of interest. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

Author contributions. S.G. and S.F.F. provided clinical care to the patient and wrote the manuscript with input from all authors. S.N. and M.M carried out experiments. J.Y. and A.W. provided assistance with research studies and literature review. P.J.K. and S.F.F. conceived the study and were in charge of overall direction and planning.

Patient consent. The patient’s written consent was obtained. The design of the work has been approved by the Yale University Institutional Review Board Human Investigations Committee (HIV approval # 1502015318).

Contributor Information

Shiv Gandhi, Section of Infectious Diseases, Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, Connecticut, USA.

Sukanya Narasimhan, Section of Infectious Diseases, Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, Connecticut, USA.

Aster Workineh, Section of Infectious Diseases, Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, Connecticut, USA.

Mark Mamula, Section of Rheumatology, Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, Connecticut, USA.

Jennifer Yoon, Section of Infectious Diseases, Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, Connecticut, USA.

Peter J Krause, Department of Epidemiology of Microbial Diseases, Yale School of Public Health and Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, Connecticut, USA.

Shelli F Farhadian, Section of Infectious Diseases, Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, Connecticut, USA; Department of Neurology, Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, Connecticut, USA.

References

- 1. Glaser CA, Gilliam S, Schnurr D, et al. In search of encephalitis etiologies: diagnostic challenges in the California Encephalitis Project, 1998–2000. Clin Infect Dis 2003; 36:731–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Granerod J, Cousens S, Davies NWS, Crowcroft NS, Thomas SL. New estimates of incidence of encephalitis in England. Emerg Infect Dis 2013; 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Garro AC, Rutman MS, Simonsen K, Jaeger JL, Chapin K, Lockhart G. Prevalence of Lyme meningitis in children with aseptic meningitis in a Lyme disease-endemic region. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2011; 30:990–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mead P, Petersen J, Hinckley A. Updated CDC recommendation for serologic diagnosis of Lyme disease. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2019; 68:703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Krause PJ, Narasimhan S, Wormser GP, et al. Borrelia miyamotoi sensu lato seroreactivity and seroprevalence in the Northeastern United States. Emerg Infect Dis 2014; 20:1183–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Schwan TG, Schrumpf ME, Hinnebusch BJ, Anderson DE, Konkel ME. GlpQ: an antigen for serological discrimination between relapsing fever and Lyme borreliosis. J Clin Microbiol 1996; 34:2483–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Krause PJ, Fish D, Narasimhan S, Barbour AG. Borrelia miyamotoi infection in nature and in humans. Clin Microbiol Infect 2015; 21:631–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Johnston D, Kelly JR, Ledizet M, et al. Frequency and geographic distribution of Borrelia miyamotoi, Borrelia burgdorferi, and Babesia microti infections in New England residents. Clin Infect Dis. 2022:ciac107. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciac107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Platonov AE, Karan LS, Kolyasnikova NM, et al. Humans infected with relapsing fever spirochete Borrelia miyamotoi, Russia. Emerg Infect Dis 2011; 17:1816–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Henningsson AJ, Asgeirsson H, Hammas B, et al. Two cases of Borrelia miyamotoi meningitis, Sweden, 2018. Emerg Infect Dis 2019; 25:1965–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Boden K, Lobenstein S, Hermann B, Margos G, Fingerle V. Borrelia miyamotoi-associated neuroborreliosis in immunocompromised person. Emerg Infect Dis 2016; 22:1617–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hovius JWR, De Wever B, Sohne M, et al. A case of meningoencephalitis by the relapsing fever spirochaete Borrelia miyamotoi in Europe. Lancet 2013; 382:658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mukerji SS, Ard KL, Schaefer PW, Branda JA. Case 32-2020: a 63-year-old man with confusion, fatigue, and garbled speech. N Engl J Med 2020; 383:1578–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gugliotta JL, Goethert HK, Berardi VP, Telford SR. Meningoencephalitis from Borrelia miyamotoi in an immunocompromised patient. N Engl J Med 2013; 368:240–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Aguero-Rosenfeld ME, Nowakowski J, Mckenna DF, Carbonaro CA, Wormser GP. Serodiagnosis in early Lyme disease. J Clin Microbiol 1993; 31:3090–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Steere AC, Mchugh G, Damle N, Sikand VK. Prospective study of serologic tests for Lyme disease. Clin Infect Dis 2008; 47:188–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Branda JA, Steere AC. Laboratory diagnosis of Lyme borreliosis. Clin Microbiol Rev 2021; 34:e00018-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Krause PJ, Carroll M, Fedorova N, et al. Human Borrelia miyamotoi infection in California: serodiagnosis is complicated by multiple endemic Borrelia species. PLoS One 2018; 13:e0191725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wagemakers A, Koetsveld J, Narasimhan S, et al. Variable major proteins as targets for specific antibodies against Borrelia miyamotoi. J Immunol 2016; 196:4185–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Piantadosi A, Mukerji SS, Ye S, et al. Enhanced virus detection and metagenomic sequencing in patients with meningitis and encephalitis. mBio 2021; 12:e0114321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kingry L, Sheldon S, Oatman S, et al. Targeted metagenomics for clinical detection and discovery of bacterial tick-borne pathogens. J Clin Microbiol 2020; 58:e00147-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Koetsveld J, Platonov AE, Kuleshov K, et al. Borrelia miyamotoi infection leads to cross-reactive antibodies to the C6 peptide in mice and men. Clin Microbiol Infect 2020; 26:513, e1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Molloy PJ, Weeks KE, Todd B, Wormser GP. Seroreactivity to the C6 peptide in Borrelia miyamotoi infections occurring in the Northeastern United States. Clin Infect Dis 2018; 66:1407–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sudhindra P, Wang G, Schriefer ME, et al. Insights into Borrelia miyamotoi infection from an untreated case demonstrating relapsing fever, monocytosis and a positive C6 Lyme serology. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 2016; 86:93–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.