Key Points

Question

How do individuals with facial and truncal acne (FTA) or acne scars (AS) relate to their condition?

Findings

As part of 2 arms of a qualitative study, 28 individuals with active FTA and 28 with AS completed a projective exercise using a personification technique to express how they relate to their condition, highlighting the burden of their condition, their attitudes, and beliefs. It reflected the evolution of the relationship to the condition and its sequelae as an emotional path to self-acceptance.

Meaning

The FTA burden on well-being is prolonged by AS and deeply rooted in the persona of affected individuals.

This qualitative study examines how patients with facial and truncal acne or acne scars relate to their condition personification exercise.

Abstract

Importance

The association of acne with emotional and social well-being is not limited to active acne because acne scarring can extend long after cessation of active lesions.

Objective

To explore the psychosocial burden of facial and truncal acne (FTA) and acne scars (AS) in a spontaneous manner using qualitative research.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This qualitative study recruited participants via local panels. A personification exercise, “Letter to my Disease,” was developed for participants of 2 independent arms, FTA and AS, of an international qualitative study in the form of letter completion.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Study outcomes comprised perceptions, psychosocial effects of FTA and AS, and coping behaviors.

Results

A total of 60 participants were recruited for the FTA and AS study. Among participants with FTA, 17 were women (57%), 21 (70%) were aged 13 to 25 years, and 9 (30%) were aged 26 to 40 years. Twenty-six (87%) participants had severe active acne and 4 (13%) had moderate active acne. Among participants with AS, 18 were women (60%), 9 (30%) were aged 18 to 24 years, and 21 (70%) were aged between 25 and 45 years. Of these 60 participants, 56 (FTA, 28 and AS, 28) completed the projective exercise, “Letter to my Disease,” the analysis of which is presented in the current study. During completion of the letter exercise, participants spontaneously expressed emotional and physical burden as well as the social stigma associated with their skin condition. Three major themes emerged, namely, (1) burden of the condition, (2) attitudes and beliefs, and (3) relationship to the personified condition.

Conclusions and Relevance

Consistent with their skin condition, participants associated acne, through personification, with the character of an intruder and unwanted companion responsible for their poor self-esteem and emotional impairment. The findings of the joint analyses of letters (FTA and AS), as a catalytic process and free-expression space, outline the continuous burden of active acne starting from adolescence and then continuing into adulthood and beyond active lesions with AS, and highlight the struggle for self-acceptance.

Introduction

Acne is a common condition afflicting many adolescents that may even persist during adulthood.1,2,3,4 Acne has the potential to adversely affect health-related quality of life (HRQoL).5,6,7,8,9

Acne scarring is a long-term complication experienced to some extent by most who have had acne and can persist for a lifetime.10 Many studies have attempted to describe the psychosocial effects of acne, but only a few have explored the negative effects of acne scarring. Acne scarring, although poorly researched, has been associated with psychosocial morbidity and impaired HRQoL. Evidence suggests that acne scarring can negatively influence the self-esteem and self-confidence of individuals, leading to anxiety, depression, and perceived decreased employability, which in turn can affect their social and vocational functioning.11,12,13 Furthermore, acne scarring14 is associated with stigmatization, which can affect their emotional well-being and social life.15

Most studies exploring the effects of acne on psychosocial well-being have focused on facial acne using dermatology-specific questionnaires.16,17,18 In-depth data on the association of both facial and truncal active acne (FTA) and its sequelae, acne scars (AS), with the psychosocial well-being are increasing but still limited.19,20,21,22 A qualitative, in-depth exploration of burden, defined as something oppressive or worrisome,23 of active FTA and AS with a projective technique is an innovative perspective to provide an insight into HRQoL of afflicted individuals.24 The present study aimed to demonstrate the association of FTA and AS with people’s lives and their similarities despite the time elapsed since active acne for participants with AS.

Methods

In the context of the 2 qualitative study arms that were part of a larger mixed-method study22 interrogating the burden of FTA and AS, participants were asked to complete a personification exercise called “Letter to my Disease.” The study was conducted in 6 countries, namely, USA, Canada, Brazil, France, Italy, and Germany. Recruitment was performed over telephone following a purposive sample strategy. Participants were recruited via Survey Healthcare Globus, Reckner, DoxaPharma, Medothic, Latina Health Solution, and Cerner Enviza research panels using a screening questionnaire to identify the eligible participants. The participants in the FTA arm self-reported based on the following definition: comedones, inflammatory papules/pustules and nodules, and severity self-assessed using the Investigator Global Assessment (IGA) definitions.25 The participants in the AS arm had moderate-to-severe atrophic AS on their faces (regardless of the location and severity of their past active acne), as per the self-assessment of clinical acne-related scars (SCARS) definitions,26 and no active acne on the face for at least 2 years prior to the study. Participants for the FTA study arm (Table 1) were aged between 13 and 40 years with moderate-to-severe active acne on their face, neck, shoulders, chest/torso, and/or back.

Table 1. Demographics of Participants: FTA and AS Study Arms.

| Characteristic | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| AS study arm participants (n = 30) | |

| Age range, y | |

| 25 to 45 | 21 (70) |

| 18 to 24 | 9 (30) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 18 (60) |

| Male | 12 (40) |

| Previously prescribed acne treatment | |

| Yes | 22 (73) |

| No | 8 (27) |

| History of acne scar treatmenta | |

| Laser treatment | 9 (30) |

| Dermabrasion | 8 (27) |

| Retinoid acid | 8 (27) |

| None | 7 (23) |

| Alternative treatment | 4 (13) |

| FTA study arm participants (n = 30) | |

| Age range, y | |

| 13 to <25 | 21 (70) |

| 26 to <40 | 9 (30) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 17 (57) |

| Male | 13 (43) |

| Areas affected by acne besides the facea | |

| Back | 21 (70) |

| Chest/torso | 13 (43) |

| Shoulders | 10 (33) |

| Neck | 6 (20) |

| Severity: self-assessment based on the Investigator’s Global Assessment (IGA) of acne severity definitions | |

| Severe | 26 (87) |

| Moderate | 4 (13) |

| Treatment currently prescribed | |

| Topical | 16 (53) |

| Topical and systemic | 8 (27) |

| Systemic | 5 (17) |

| Do not know | 1 (3) |

Abbreviations: AS, acne scars; FTA, facial and truncal acne.

Multiple answers.

Eligible participants for the AS study arm (Table 1) were aged between 18 and 45 years.

A total of 60 individuals, 30 with active FTA and 30 with AS (5 in each country and each arm) were recruited. Four of these 60 participants did not complete the personification exercise. Data from the remaining 56 participants were included.

The Letter to my Disease exercise required participants to imagine their acne or AS with human quality or characteristics and to engage with it in writing. All participants were asked to begin the letter with “Dear acne or acne scars…” As such, participants naturally followed a conversational style of writing using the second-person pronoun to refer to FTA and AS. All letters were completed in the local language and translated into English by researchers at the local agencies. Discussions between local and main researchers on the translation were undertaken based on queries regarding the understanding of the data to mitigate the linguistic variation. The letters were compiled to produce 2 distinct data sets suitable for thematic analysis.

This technique proved to be a powerful, evocative tool for eliciting hidden meanings and emotions.27,28 The personification process of the condition disassociates the respondents to the answer they give, deactivating their conscious defenses. As such, this projective exercise gives permission to participants to challenge their condition, ask for accountability, and express their disagreement with their condition. Furthermore, it led them to formulate feelings in a way that could not have been assessed with standard guided questions.29,30,31

Thematic analysis was performed using NVivo, version 12 Plus (QSR International) to code and categorize the data. The first letters of the FTA study were initially coded by 2 researchers who then reconciled any discrepancies into a final codebook. The codebook was applied to all the letters, allowing comparison of the FTA and AS data sets (Table 2). The analytic approach used was inductive, starting from the code, that is the smallest descriptive analytic unit to the theme and its interpretative stance, forming the narrative of the emotional path of the participants in the FTA and AS arms.

Table 2. Emergent Categories and Codes Frequencies.

| Categories and codes | Representative quotation or researcher description | No. (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of occurrences FTA (n = 28)a | No. of occurrences AS (n = 28)a | Overall (n = 56)a | ||

| Psychological effect categoryb | ||||

| Effect on self-esteem | You mess with my self-esteem, and it bothers me a lot. (FTA study, Brazil) | 11 (39) | 4 (14) | 15 (27) |

| Self-conscious | I can’t go out in public without makeup, I’m afraid of people pointing it out making me feel self-conscious. (FTA study, USA) | 11 (39) | 8 (29) | 19 (34) |

| Unaware of acne outcomes | I tried to get rid of you by squeezing you and I did not know it could stain me. (FTA study, Brazil) | 4 (14) | 1 (4) | 5 (9) |

| Losing control | I didn’t choose to have you, you still came. (FTA, Canada) | 4 (14) | 0 | 4 (7) |

| Lingering burden (even if cured) | At first, I thought that you would disappear quickly and leave no traces, unfortunately this was not the case. Now I look at what remains, and I am overwhelmed at the sight. (AS, Germany) | 4 (14) | 6 (21) | 10 (18) |

| Image of self | When you look in the mirror you look terrible. (AS, Germany) | 2 (7) | 5 (18) | 7 (13) |

| Feelings and emotions categoryb | ||||

| Shame/embarrassment | I’m very ashamed because of you, very much! (FTA, Brazil) | 11 (39) | 3 (11) | 14 (25) |

| Feel ugly | But why do I feel so ugly? (FTA, Canada) | 8 (29) | 7 (25) | 15 (27) |

| Powerlessness | I cry sometimes because you come and go as you want. At the completely wrong times, as well. (FTA, USA) | 7 (25) | 2 (7) | 9 (16) |

| Unfairness | Why me? I don’t think I’ve done anything to deserve you being in my life, at all. (FTA, USA) | 5 (18) | 5 (18) | 10 (18) |

| Frustration | Something that has troubled me for years is how come there is no treatment effective enough? And why me? (AS, France) | 2 (7) | 5 (18) | 7 (13) |

| Difficult/hard | Your presence made some periods of my life really difficult, you collected all my frustrations, regrets. (AS, Italy) | 1 (3.5) | 6 (21) | 7 (13) |

| Bothersome | I find it exhausting and very annoying that I can never get rid of you. (AS, Germany) | 1 (3.5) | 5 (18) | 6 (11) |

| Sadness | You make me sad when I look at you. (AS, Brazil) | 0 | 4 (14) | 4 (7) |

| Hate | I hate you! (FTA, Canada) | 1 (4) | 3 (11) | 4 (7) |

| Physical effects categoryb | ||||

| Visible marks | Your marks on my face mean that I think about you every day. (AS, France) | 9 (32) | 8 (29) | 17 (30) |

| Cause of acne/acne scars | Some of those who suffer from acne blame hormones, eating habits, sweets, salami, greasy soaps, mum and dad who suffered from acne as adolescents too! (FTA, Italy) | 5 (18) | 3 (11) | 8 (14) |

| Irritation/redness | It turns out that you cause me discomfort, cause me irritation. (FTA, Brazil) | 5 (18) | 1 (4) | 6 (11) |

| Flare | I find it exhausting and very annoying that you break out at the worst of times. (FTA, Germany) | 4 (14) | 1 (4) | 5 (9) |

| Soreness/pain | I had lots of acne and it was sore and very ugly. (FTA, Brazil) | 4 (14) | 0 | 4 (7) |

| Skin unpleasant aspect | Ever since I went through puberty, I have always had problems with pimples and greasy, blemished skin. (AS, Germany) | 3 (11) | 3 (11) | 6 (11) |

| Extension (truncal) | When you appear on my back, I don’t get that mad. I can deal with/cover that up. Appearing on my face is a whole different story. (FTA, USA) | 3 (11) | 0 | 3 (5) |

| Reminiscence of acne | The acne went away and left me with you [scars]. (AS, Brazil) | 0 | 3 (11) | 2 (5) |

| Treatment burden categoryb | ||||

| Treatment burden (texture, odor, quantity, or other) | I wash my face 4 times a day and still look dirty. I look unclean. I look unpretty. I’ve tried birth control, different soaps. (FTA, Canada) | 6 (21) | 0 | 6 (11) |

| Financial burden | I’ve tried everything from proactive in my teen years to oil cleansing. The amount of money I’ve spent on you is crazy. (FTA, USA) | 5 (18) | 3 (11) | 8 (14) |

| Treatment lack of efficacy | How is it possible that nowadays there are efficient treatments for cancer and other serious diseases while acne that for ages has been troubling teenagers and adults can’t be successfully cured? (FTA, Italy) | 4 (14) | 4 (14) | 8 (14) |

| Lifestyle adaptation | I cannot take pictures without making changes [to my appearance] to try hide you. (FTA, Brazil) | 3 (11) | 0 | 3 (5) |

| Treatment efficacy | I am in treatment now, with a dermatologist who understood me, and I am getting success, the results are extremely visible, and I think you are, after all, leaving me. (FTA, Brazil) | 3 (11) | 2 (7) | 5 (9) |

| Attitudes and coping strategies categoryb | ||||

| Hide/cover-up | Since I can’t erase you, I decided to cover you with the beard. (AS, Italy) | 12 (43) | 11 (39) | 23 (41) |

| Hope | I hope to get rid of you as soon as possible. (FTA, Brazil) | 12 (43) | 7 (25) | 19 (34) |

| Fight | I’m fighting against you, but this is expensive. (FTA Brazil) | 6 (21) | 2 (7) | 8 (14) |

| Health care professional (HCP) follow-up | I have enough of taking burdock pills and putting cream, past adolescence I hope I will not have [acne] anymore, I have an appointment with a dermatologist in July. (FTA, France) | 4 (14) | 1 (3.5) | 5 (9) |

| Isolation | I find myself avoiding big crowds because I am self-conscious about what people might think, when they see my skin. (FTA, USA) | 4 (14) | 3 (11) | 7 (13) |

| Acceptance | Even though your presence is seen it is not felt. You remind me of a period of my life where a lot of change was happening. Because you are on my face, I see you every day, but I don’t feel less beautiful (AS, Canada) | 4 (14) | 13 (47) | 17 (30) |

| Constraints (diet, clothing, leisure) | I have to do blood tests to see if the treatment I am doing is not bad for my health, I cannot eat what I want. (FTA, Brazil) | 4 (14) | 1 (4) | 5 (9) |

| Trying to be positive | I don’t feel much about this unchosen companionship. Sometimes I ask “why me” but other than that I’m okay and feel great and confident in the skin I’m in. (AS, Canada) | 3 (11) | 6 (21) | 9 (16) |

| Socialization categoryb | ||||

| Other people’s opinion | Sometimes I find myself in situations when you become the subject of the conversation and the reason I am criticized. (FTA, Italy) | 11 (39) | 9 (32) | 20 (36) |

| Friendship | To the friends that I had, I always tried to hide you. (FTA, Brazil) | 3 (11) | 0 | 3 (5) |

| Love relationship | My boyfriend left, and I got really bad, I remember a lot of this time, because when I look in the mirror and see you, I know that you have marked my life forever. (AS, Brazil) | 0 | 3 (11) | 3 (5) |

| Work and school situation | I’ve faced social stigma at school and in the workplace. (AS, Canada) | 3 (11) | 3 (11) | 6 (11) |

| Participant’s position categoryb | ||||

| The plea/the order to leave | Don’t come back...ever!! seriously. (FTA, USA) | 16 (57) | 2 (7) | 18 (32) |

| Helplessness | But why do I feel so ugly? Why do I feel so ashamed? (FTA, Canada) | 7 (25) | 1 (3.5) | 8 (14) |

| Wish it never happened | I really would have loved to never have met you. Your marks on my face mean that I think about you every day. (AS, France) | 0 | 8 (29) | 8 (14) |

| Wish it disappears | I wish you were not there! I wish I had clean and uncomplicated skin. I hope that you will eventually disappear. (AS, Germany) | 0 | 8 (29) | 8 (14) |

| Magic spell | I truly wish there was a magic spell to make you disappear. (AS, Canada) | 0 | 3 (11) | 3 (5) |

| Personified condition’s position categoryb | ||||

| The stronger external force | I didn’t choose to have you, you still came however, and I still don’t want you. (FTA, Canada) | 11 (39) | 2 (7) | 13 (23) |

| The intruder | Acne, you are so comfortable living on my skin, I wish I could be comfortable living in it too. (FTA, Canada) | 6 (21) | 4 (14) | 10 (18) |

| The unwanted companion | My hope is that, someday soon, you will leave and never return for you are not welcome on my body. (FTA, Canada) | 4 (14) | 6 (21) | 10 (18) |

| The accountable one | Because you were in my body, I had no friends. (FTA, Brazil) | 5 (18) | 2 (7) | 7 (13) |

| The self-acceptance | It took me a while to accept these marks as part of my body, but I’ve gotten much better at accepting them. (AS, Canada) | 0 | 6 (21) | 6 (11) |

Abbreviations: AS, acne scars; FTA, facial and truncal acne.

Of the 60 participants of the qualitative FTA and AS study arms, 4 did not complete the personification exercise.

Categories are not mutually exclusive; therefore, the total percentage exceeds 100%.

This study followed the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) reporting guidelines (COREQ)32 to ensure the rigor and validity of the methodological and analytic process. Data source and researcher triangulation also support credibility of the data. The research complied with General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), all international/local data protection legislation, and Insights Association/European Society for Opinion and Marketing Research (ESOMAR)/European Pharmaceutical Market Research Association (EphMRA)/British Healthcare Business Intelligence Association (BHBIA). All adult participants provided informed consent prior to participation. Minor participants were sent an age-appropriate participant information sheet and their participation relied on both parental and their own consent. The study received approval by the Cerner Enviza Internal IRB/Ethics Committee. Study design, data collection, data management, and analyses were conducted by Cerner Enviza (Paris, France).

Results

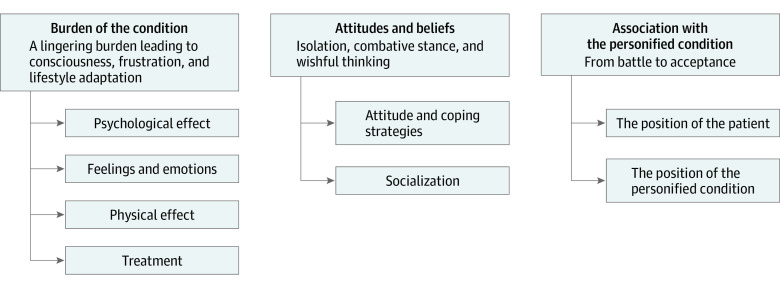

Sixty participants were recruited into FTA and AS arms. Among those in the FTA arm, 70% were aged between 13 and 25 years and 30% were aged 26 to 40 years. In the AS arm, 30% participants were aged 18 to 24 years and 70% were aged 25 to 45 years. Participant demographics and profiles are shown in Table 1. Of the 60 participants, 56 (28 in each group) completed the personification exercise. The length of letters ranged from 1 to 20 sentences. Fifty codes, organized into 8 categories of analysis (Table 2), were distilled and outlined. Three main themes emerged: (1) burden of the condition, (2) attitudes and beliefs, and (3) relationship to the personified condition (Figure 1). Although these are 2 different populations, common themes were identified in both arms that allowed a comparative analysis of the evolution of those with FTA and AS and their skin conditions.

Figure 1. Conceptual Model of Themes and Categories of FTA and AS Letters.

The 3 interpretative themes are indicated below their boldfaced theme in the upper 3 boxes. The categories are each indicated in a separate box and linked to the associated theme. AS indicates acne scars; FTA, facial and truncal acne.

Burden of the Condition: A Lingering Burden Leading to Self-Consciousness, Frustration, and Lifestyle Adaptation

This theme encompasses 4 analytical categories (Table 2).

Psychological Effects: “You Hurt me so Much Emotionally.” (AS, Canada)

Participants from the FTA and AS arms described a range of psychological consequences affecting their everyday lives and relationships. Being self-conscious was the most frequently reported psychological effect (Table 2). “I don’t feel beautiful with you and my self-esteem is lower because many others don’t like my looks either” (FTA, Germany).

Another recurrent notion was the lingering burden caused by FTA and AS. Participants described the difficulty of having to live with the constant reminder of acne because of these persistent lesions.

Poor self-esteem was more frequently mentioned by participants in the FTA arm (11 for FTA vs 4 for AS). Poor self-esteem was often associated with the lack of control over one’s condition and their inability to manage their condition (Table 2).

The image of self was expressed in the letters by participants, recollecting avoiding being photographed or self-viewing with a mirror because the only thing “noticeable” were the marks on their faces. The AS arm participants spontaneously mentioned negative image of self, more often than the FTA arm participants (Table 2), highlighting a deeply broken image of self.

Feelings and Emotions:“I Hate You.” (FTA, Canada)

Participants in the FTA arm described helplessness and unfairness of having to deal with a skin condition, for which they do not know the origin nor the means to treat or control. This sense of powerlessness was expressed by several in the FTA arm who referred to acne as an “intruder endowed with its own will, having decided to move in without being invited.”

The range of emotions described by the participants in the AS arm was broader (Table 2), and included struggle, annoyance, frustration, sadness, and resentment. Anger and hate were clearly expressed, especially by those in the AS group: “I feel anger and grief when I see you” (AS, Germany); “I hate how you look on my face!” (AS, Canada).

Physical Effects: “My Image in the Mirror is Hard to Bear.” (FTA, Germany)

Overall, the visual aspect of their skin was commonly mentioned as an adverse effect (Table 2). Physical symptoms of pain and irritation were regularly cited (Table 2). Participants expressed their perception of the unpleasant feeling of the skin being oily and having an uneven topology and/or color. Three participants in the FTA group mentioned the acne on their chest and/or back as an extension of their facial acne.

Treatment Burden23: “I Have [Had] Enough of Taking Pills and Putting [on] Cream.” (FTA, France)

The overall lack of treatment efficacy, whether prescribed or not, and its associated financial burden were stated by both groups (Table 2): “Why must half of my paycheck go toward soaps, and washes, and special makeup and makeup cleaners?” (FTA,Canada).

The inconvenience caused by treatments (texture, odor, and frequency) was cited by a few participants in the FTA arm. The code Lifestyle Adaptation (Table 2) include dietary and cleansing routines that participants in the FTA group had to adopt. The treatment burden was mentioned to a lesser extent by those in the AS arm who no longer followed restrictive diets and treatment routines.

Attitudes and Beliefs: Isolation, Combative Stance, and Wishful Thinking

The theme attitudes and beliefs includes 2 analytical categories, attitudes and coping strategies and socialization.

Attitudes and Coping Strategies: “I’m Fighting Against You, and I Had to Change a Lot in my Life Because of the Treatment.” (FTA, Brazil)

Both groups reported using make-up and clothes to cover their acne or scars as the predominant strategy to cope and maintain a social life. Another strategy was self-isolation. The term “hope” was also commonly employed, with some differences observed between FTA and AS letters. To FTA study participants, the feeling of hope appeared as an active attitude linked to treatment efficacy and improvement over time. Participants in the FTA arm described a combative stance toward their skin condition as a fight they hope to win. “I will do everything to fight you!” (FTA, Germany). Participants in the AS arm expressed being hopeful that the scars would disappear over time on one hand and accepting scars as part of their body image.

Socialization: “I Was Often Afraid to Relate to People Because of My Appearance.” (FTA, Brazil)

In both groups, the opinion of others and peer pressure were described as one of the main drivers of their emotions and choice to adopt concealing strategies. They expressed difficulties to face work and school situations.

Age range differences in the groups, with younger participants in the FTA arm, influenced the importance of different social links. The effects of acne on the social lives of participants in the FTA arm with friends was stronger, and was referred to many times (code Friendship). Peer intimacy was only mentioned in AS letters by 3 participants.

Relationship to the Personified Condition: From Battle to Acceptance

The personification of the disease revealed the broad outlines of the deep psychological effects on the participants. Some common personification traits were found in both groups, such as the image of an uninvited intruder.

Participant’s Position: “You’ve Been My Life Companion.” (FTA, Italy)

In the letters from the FTA arm, The Plea/The Order to Leave (Table 2) expressed the active attitude of participants who did everything possible to take care of their skin by adopting skin care routines, diet, and lifestyle changes but also hoped for treatment efficacy and their acne to disappear. Personification of the condition allowed the participants to order and plead: “Please leave me alone!” (FTA, USA).

In the AS arm letters, the personification approach highlighted the path taken toward acceptance. In comparison with the plea, the code Wish it never happened (Table 2) described the powerlessness linked to the growing acceptance that scars would remain.

The code Wish it disappears refer to wishful thinking because many participants in the AS group gave up on the idea of finding a medical solution to their scars. Concurring with this idea, a few AS respondents wished that there was a Magic spell to escape their scars.

Personified Condition’s Position: “Don’t Follow me Anywhere.” (AS, Canada)

The letters from both groups described the recurrent figures of The intruder and The unwanted companion, indicating that the participants felt that the FTA and subsequent AS imposed themselves in their bodies. Thus, it made them feel as if they were hosting an unwanted companion that they wished they could get rid of. “You are not welcome on my body” (FTA, Canada).

Participants in the FTA group described an alien imposing its own will and pointing to their feeling of powerlessness (code The stronger external force). Many participants in the FTA arm emphasized that the acne kept reappearing despite their efforts. “You always came back and even stronger” (FTA, Brazil).

Although AS was always considered an uninvited companion, it was acknowledged as a distinctive sign or a longstanding partner. “It’s almost laudable how you attached to me. What can I say, thank you for such devotion even if I didn’t consent? However, your presence for sure helped me to grow and to develop the awareness of the fact that the appearance is not important” (AS, Italy).

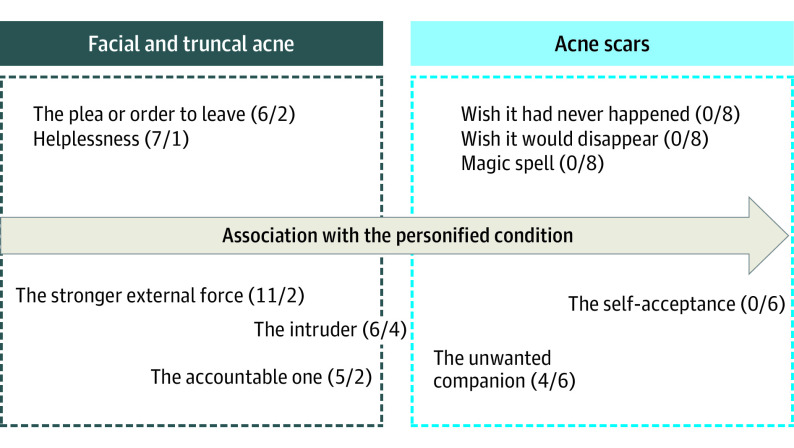

Comparison Between FTA and AS Groups

Overall, participants expressed common themes in the FTA and AS letters (Figure 2). However, poor self-esteem was more frequently expressed by participants in the FTA group than those in the AS group. The notion of shame and embarrassment was also much more common in FTA letters compared with those in the AS group.

Figure 2. The Evolution of the Relationship to the Personified Condition: A Conceptual Model.

The codes of each category (the positions of the patient and the personified condition) are placed according to their occurrences in facial and truncal acne (FTA) and acne scars (AS) letters. The occurrences are shown as follows: (x occurrence in FTA letters/x occurrence in AS letters).

Although participants in the FTA group communicated their hope of improvement, only a few of those in the AS group verbalized this hope, whereas most expressed defeat and acceptance of their state.

“I hope that one day, you will leave, and I will find my true self. One day everything will be fine” (FTA, Germany).

“I accept that you are part of me, but I will always try to find a way to make you leave forever” (AS, Brazil).

Given that the 2 groups were at different stages of the condition, more participants in the FTA group formulated a plea for acne to go away and a minority of those in the AS group rather wished it never happened in the first place.

Similarly, the personified condition was a more periodically recurring, powerful figure in the FTA group, and a longstanding, pervasive one for the AS group.

“Constant and unwanted companion” (AS, Germany).

“The more I want to get rid of you, the more you show me that you are in command of the situation” (FTA, Brazil).

Discussion

The association of acne and its sequelae with HRQoL has been demonstrated in previous studies,13 along with its adverse effects on self-image and social functioning.33 Some studies have shown that it can be defined as a chronic condition,1,34 which is in agreement with our findings.

Engaging in an imaginary conversation with their condition, participants with active acne and AS in the present study addressed the emotional/physical burden and social stigma associated with their skin condition.

The major contribution of this projective, personification approach is that it documents the unprompted voice of individuals with acne as well as of those with AS using similar exercises at different time periods during their struggle with acne. Retracing such a path would have been difficult using other methodologies.29

This approach to FTA and AS delineates the persistence of psychological and social disability owing to acne and its sequelae, similar to those in other chronic medical conditions such as asthma and diabetes.2,27 The present study provides a new perspective on the psychological and social effects of acne and AS. It allowed us to explore the emotional path starting with FTA that further progressed toward AS involving frustration and battle, leading to wishful thinking and sometimes acceptance. The recurrent image of an uninvited intruder, common in both the FTA and AS groups, was rejected by participants in the FTA group and finally accepted by some in the AS group. The main difference between active FTA and AS groups was the growing resilience of self with the sequelae of the condition, even though this was not the case for the whole AS group.

As Litchman et al27 outlined, “understanding patient’s emotional response to chronic conditions is an important aspect of patient care.” This can help physicians target relevant information and develop educational tools to address patient concerns and manage treatment expectations. Furthermore, this approach can assist in regaining control of their emotional state and develop healthy coping skills.

Limitations

Our results should be interpreted in the context of a few limitations. The limited sample size, inherent to qualitative methodology, does not allow generalization of findings or report potential cultural differences that may exist between the participants. However, qualitative approaches are meant to describe and explain processes rather than quantify phenomena. A longitudinal design to report the emotional journey with the same cohort from active acne to AS, although feasible, would be impractical. The non-English letters were translated from local language into English, which may have reduced accuracy and nuance. Considering the restrictions on collection of race and ethnicity data in Europe, this was not reported for our total sample of participants. Future studies should focus on the differences in the experience of acne according to race and ethnicity.

Conclusions

The findings of this qualitative study suggest that FTA and AS inflict considerable psychological and physical burden on individuals with these conditions. These consequences should be considered in patient treatment through awareness, education, and appropriate symptom management to address insecurity and provide a greater sense of control. Accurate diagnosis, establishing a relationship of trust between the managing physician and the patient, and discussing potential consequences with patients may help reduce frustration and anger.

References

- 1.Gollnick HPM, Finlay AY, Shear N; Global Alliance to Improve Outcomes in Acne . Can we define acne as a chronic disease? If so, how and when? Am J Clin Dermatol. 2008;9(5):279-284. doi: 10.2165/00128071-200809050-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hay RJ, Johns NE, Williams HC, et al. The global burden of skin disease in 2010: an analysis of the prevalence and impact of skin conditions. J Invest Dermatol. 2014;134(6):1527-1534. doi: 10.1038/jid.2013.446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martin AR, Lookingbill DP, Botek A, Light J, Thiboutot D, Girman CJ. Health-related quality of life among patients with facial acne—assessment of a new acne-specific questionnaire. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2001;26(5):380-385. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2230.2001.00839.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Webster GF. Clinical Presentation of Acne. In: Zeichner J, ed. Acneiform Eruptions in Dermatology: A Differential Diagnosis. Springer; 2014:13-17, doi: 10.1007/978-1-4614-8344-1_2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Halvorsen JA, Stern RS, Dalgard F, Thoresen M, Bjertness E, Lien L. Suicidal ideation, mental health problems, and social impairment are increased in adolescents with acne: a population-based study. J Invest Dermatol. 2011;131(2):363-370. doi: 10.1038/jid.2010.264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gupta MA, Gupta AK. Depression and suicidal ideation in dermatology patients with acne, alopecia areata, atopic dermatitis and psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 1998;139(5):846-850. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1998.02511.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yazici K, Baz K, Yazici AE, et al. Disease-specific quality of life is associated with anxiety and depression in patients with acne. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2004;18(4):435-439. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2004.00946.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vallerand IA, Lewinson RT, Parsons LM, et al. Risk of depression among patients with acne in the U.K.: a population-based cohort study. Br J Dermatol. 2018;178(3):e194-e195. doi: 10.1111/bjd.16099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dréno B. Assessing quality of life in patients with acne vulgaris: implications for treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2006;7(2):99-106. doi: 10.2165/00128071-200607020-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Layton AM, Henderson CA, Cunliffe WJ. A clinical evaluation of acne scarring and its incidence. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19(4):303-308. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.1994.tb01200.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dreno BL, Bettoli V, Torres Lozada V, Kang S; Global Alliance to Improve Outcomes in Acne . Evaluation of the prevalence, risk factors, clinical characteristics, and burden of acne scars among active acne patients who have consulted a dermatologist in Brazil, France and the USA. Present 23rd EADV Congr Amst Netherland. 2014;(P024). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fife D. Practical evaluation and management of atrophic acne scars: tips for the general dermatologist. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2011;4(8):50-57. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tasoula E, Gregoriou S, Chalikias J, et al. The impact of acne vulgaris on quality of life and psychic health in young adolescents in Greece: results of a population survey. An Bras Dermatol. 2012;87(6):862-869. doi: 10.1590/S0365-05962012000600007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dréno B, Tan J, Kang S, et al. How people with facial acne scars are perceived in society: an online survey. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2016;6(2):207-218. doi: 10.1007/s13555-016-0113-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goodman GJ. Treating scars: addressing surface, volume, and movement to expedite optimal results. Part 2: more-severe grades of scarring. Dermatol Surg. 2012;38(8):1310-1321. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2012.02439.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Del Rosso JQ, Stein-Gold L, Lynde C, Tanghetti E, Alexis AF. Truncal acne: a neglected entity. J Drugs Dermatol. 2019;18(12):205-1208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Poli F, Auffret N, Leccia MT, Claudel JP, Dréno B. Truncal acne, what do we know? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34(10):2241-2246. doi: 10.1111/jdv.16634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Prior J, Khadaroo A. ‘I sort of balance it out’. Living with facial acne in emerging adulthood. J Health Psychol. 2015;20(9):1154-1165. doi: 10.1177/1359105313509842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ip A, Muller I, Geraghty AWA, Platt D, Little P, Santer M. Views and experiences of people with acne vulgaris and healthcare professionals about treatments: systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative research. BMJ Open. 2021;11(2):e041794. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-041794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ip A, Muller I, Geraghty AWA, McNiven A, Little P, Santer M. Young people’s perceptions of acne and acne treatments: secondary analysis of qualitative interview data. Br J Dermatol. 2020;183(2):349-356. doi: 10.1111/bjd.18684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barbieri JS, Fulton R, Neergaard R, Nelson MN, Barg FK, Margolis DJ. Patient Perspectives on the Lived Experience of Acne and Its Treatment Among Adult Women With Acne: A Qualitative Study. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157(9):1040-1046. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.2185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tan J, Beissert S, Cook-Bolden F, et al. Evaluation of psychological well-being and social impact of atrophic acne scarring: A multinational, mixed-methods study. JAAD Int. 2021;6:43-50. doi: 10.1016/j.jdin.2021.11.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Burden. In: Merriam-Webster. Merriam-Webster, incorporated. 2022. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/burden#learn-more

- 24.Shahar G, Lerman SF. The personification of chronic physical illness: its role in adjustment and implications for psychotherapy integration. J Psychother Integration. 2013;23(1):49-58. doi: 10.1037/a0030272 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tan JKL, Tang J, Fung K, et al. Development and validation of a comprehensive acne severity scale. J Cutan Med Surg. 2007;11(6):211-216. doi: 10.2310/7750.2007.00037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tan J, Thiboutot D, Gollnick H, et al. Development of an atrophic acne scar risk assessment tool. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31(9):1547-1554. doi: 10.1111/jdv.14325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Litchman ML, Allen NA, McAdam-Marx C, Feehan M. Using projective exercises to identify patient perspectives of living with comorbid type 2 diabetes and asthma. Chronic Illn. 2021;17(4):347-361. doi: 10.1177/1742395319872788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Russell AM, Ripamonti E, Vancheri C. Qualitative European survey of patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: patients’ perspectives of the disease and treatment. BMC Pulm Med. 2016;16(1):10. doi: 10.1186/s12890-016-0171-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barton KC. Elicitation techniques: getting people to talk about ideas they don’t usually talk about. Theor Res Soc Educ. 2015;43(2):179-205. doi: 10.1080/00933104.2015.1034392 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Levin-Rozalis M. Using projective techniques in the evaluation of groups for children of rehabilitating drug addicts. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2006;27(5):519-535. doi: 10.1080/01612840600600008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Frank LK. Projective Methods. Charles C. Thomas, Publisher, Springfield, Illinois,1948;vii:86. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349-357. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thomas DR. Psychosocial effects of acne. J Cutan Med Surg. 2004;8(S4)(suppl 4):3-5. doi: 10.1007/s10227-004-0752-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zouboulis CC. Acne as a chronic systemic disease. Clin Dermatol. 2014;32(3):389-396. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2013.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]