Abstract

Mefenamic acid represents a widely used nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) to treat the pain of postoperative surgery and heavy menstrual bleeding. Like other NSAIDs, mefenamic acid inhibits the synthesis of prostaglandins by nonselectively blocking cyclooxygenase (COX) isoforms COX-1 and COX-2. For the improved selectivity of the drug and, therefore, reduced related side effects, the carborane analogues of mefenamic acid were evaluated. The ortho-, meta-, and para-carborane derivatives were synthesized in three steps: halogenation of the respective cluster, followed by a Pd-catalyzed B–N coupling and hydrolysis of the nitrile derivatives under acidic conditions. The COX inhibitory activity and cytotoxicity for different cancer cell lines revealed that the carborane analogues have stronger antitumor potential compared to their parent organic compound.

1. Introduction

Mefenamic acid (1, Scheme 1) is a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) with a wide range of pharmacological activities such as analgesic, anti-inflammatory, and antipyretic activity. It is used for treatment of muscular aches, menstrual cramps, headache, dental pain, and as a painkiller after surgeries.1−3 Based on its structure, mefenamic acid is a derivative of N-aryl anthranilic acid and it belongs to the class of fenamic acids.4−6 Like many NSAIDs, mefenamic acid binds to cyclooxygenase (COX) and thus inhibits the synthesis of prostaglandins.

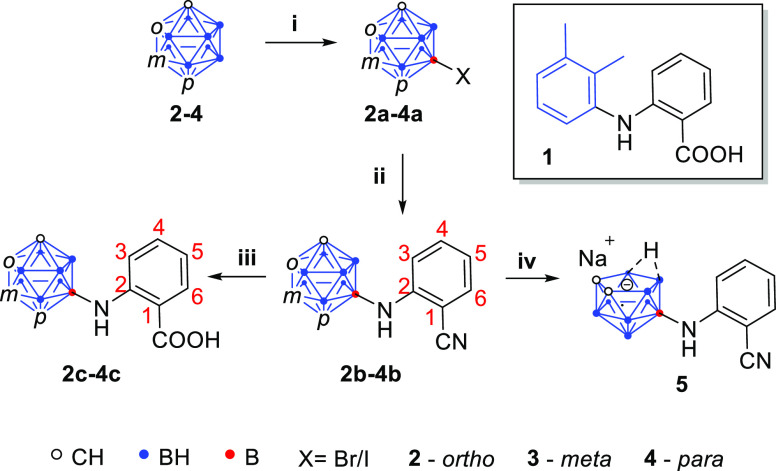

Scheme 1. Synthesis of Carborane Analogues of Mefenamic Acid.

Reaction conditions: (i) halogenation of the cluster: 0.5 equiv of I2 or Br2, mixture of HNO3/H2SO4 (1:1, v/v) in glacial acetic acid, 60–80 °C for 1–4.5 h, 81–97%; (ii) B–N coupling of 2a–4a with 2-aminobenzonitrile with Pd(dba)2–BINAP–KOt-Bu or Sphos-Pd-G3–Sphos–K3PO4 as a catalyst in 1,4-dioxane, 70–95 °C for 18.5–46 h, 30–62%; (iii) hydrolysis of 2b–4b using 40 vol % aq H2SO4 in glacial acetic acid, 90–120 °C for 7–23 h, 57–91%; (iv) deboronation of 2b using NaF in ethanol/water (3:2, v/v) at 90 °C for 6 h quantitatively gave compound 5.

COX, on the other hand, is a homodimer and integral membrane protein that exists in two isoforms: COX-1, which is constitutively expressed in most tissues and is known as a “housekeeping” enzyme, and COX-2, which is inducible and primarily associated with pain, fever, and inflammation.7 Both isoforms share a similar structure and high sequence identity (Figure 1); thus, many NSAIDs, including mefenamic acid, are nonselective on their mode of action.8 The crystal structure for the binding of mefenamic acid with the enzyme was reported by Orlando and Malkowski, verifying the binding in the active site of cyclooxygenase and the interaction of its carboxylic acid group with the amino acids Tyr-385 and Ser-530 (Figure 2).9

Figure 1.

Structures of COX-1 and COX-2. Isoleucine-to-valine substitution opens up the hydrophobic pocket in COX-2 compared to COX-1. Tyr-385 and Ser-530 are essential for COX activity. Adopted from Mengle-Gaw and Schwartz.10

Figure 2.

Structure of mefenamic acid cocrystallized with human COX-2. Reprinted from Orlando and Malkowski.9

Nonselective COX inhibition by NSAIDs causes several malfunctions in the human body, e.g., gastrointestinal disorder after long-term use. Serious side effects of mefenamic acid are related to the reduction of the amount of the cytoprotective prostaglandins, which causes gastric irritation, gastric ulcers, dyspepsia, and bleeding.11 Furthermore, extended exposure to mefenamic acid could cause hepatotoxicity and nephrotoxicity.12

The above-mentioned facts were the reason why investigations on finding a way to reduce the side effects of NSAIDs became a very important task for pharmaceutical chemistry. As a result, many studies on the structure of COX and also on the mode of action of drugs were conducted, which revealed that besides many similarities between the two isoforms, the active site of COX-2 is approximately 25% larger than that of COX-1. Therefore, a size enlargement of classical NSAIDs resulted in COX-2 selectivity.13

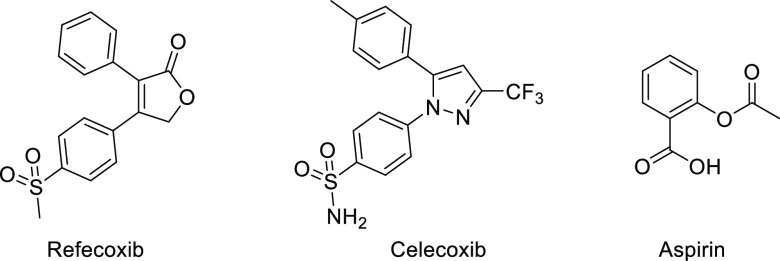

Accordingly, celecoxib and refecoxib, larger molecules compared to other NSAIDs, were introduced as COX-2 selective inhibitors (Figure 3).8 However, rofecoxib had to be withdrawn from the market as it was reported to be the main cause of cardiovascular disorders, which caused the death of patients with Alzheimer’s disease, while celecoxib is used due to similar reasons nowadays only for certain indications like rheumatoid arthritis or Morbus Bechterew after the risk-to-benefit analysis by the physician.14

Figure 3.

Chemical structures of refecoxib, celecoxib, and aspirin.

The interest in research on NSAIDs was further increased when their cytotoxic properties were revealed.15,16 It is believed that they display their anticancer effects through inhibition of COX-2, because this isoform is supposed to play a role in carcinogenesis and is often overexpressed in human premalignant and malignant tissues. However, NSAIDs also promote apoptosis through mechanisms that are independent of COX inbibiton.17 Thus, mefenamic acid was found to promote cytostatic activity against various cancer types such as human liver cancer cells (CHANG and HuH-7) by inducing apoptosis18 and was reported to have cytotoxic properties when administered to human breast cancer (MCF-7), human bladder (T24), human lung carcinoma (A-549), and mouse fibroblast-like cells (L-929).19

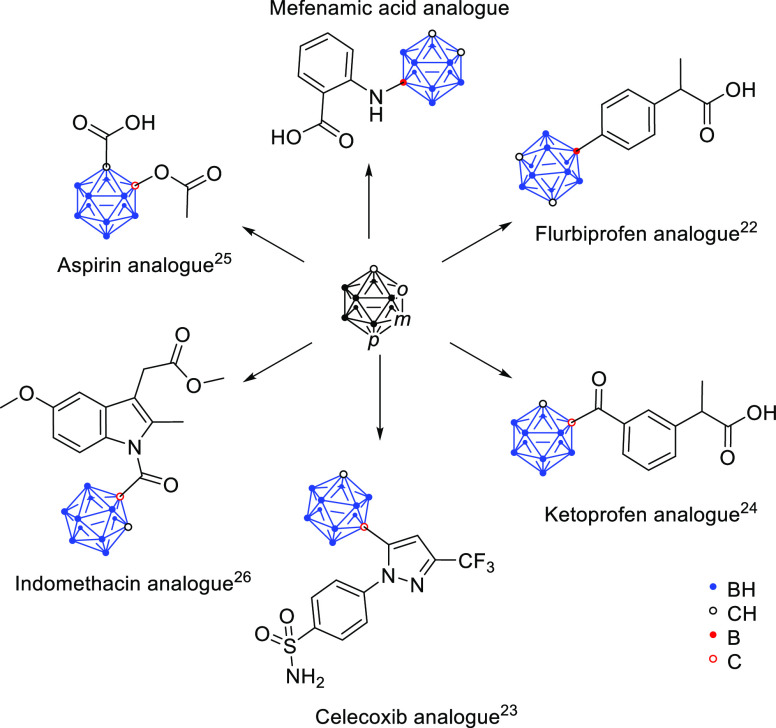

Based on their role on treatment of inflammation and their cytotoxic activity, NSAIDs became an attractive target on drug design technology to synthesize compounds with improved COX-2 selectivity and less side effects. A more recent and very interesting strategy on this topic is incorporation of the 12-vertex dicarba-closo-dodecaborane (carborane) as a bioisosteric replacement of a phenyl ring and as a hydrophobic moiety.13,20−26

Carboranes are icosahedral clusters where at least one BH− vertex in (B12H12)2− is replaced by an isolobal CH vertex. The most prominent species is dicarba-closo-dodecaborane. These clusters are used as aryl mimetics for biologically active compounds, and due to the high boron content, carboranes are also studied as potential reagents for use in boron neutron capture therapy (BNCT).27 They are very hydrophobic, generally exhibit low toxicity, and are metabolically stable boron clusters that can exist in three different isomers: ortho (1,2-), meta (1,7-), and para (1,12-) dicarba-closo-dodecaborane, herein numbered as 2, 3, and 4, respectively (Scheme 1).21,28,29 Because of their remarkable properties, carboranes became a very interesting tool for drug design and medicinal chemistry. Above all, many carborane analogues of NSAIDs were reported by our group (Scheme 2).22,24−26,30−32 For example, asborin (Scheme 2) as a carborane analogue of aspirin (Figure 3) was found to inhibit COX in a weaker manner compared with aspirin but revealed aldo/keto reductase 1A1 as another prominent biological target of the carborane analogue.25 On the other hand, the modification of the nonselective COX inhibitor indomethacin with a carborane moiety resulted in a shift toward COX-2 selective inhibition, which was the most potent for the nido-indoborin analogue.26

Scheme 2. Carborane Analogues of NSAIDs.

In this paper, we present the carborane analogues of mefenamic acid, where the 2,3-dimethylphenyl moiety of the drug is substituted by the carborane. This replacement allowed a good comparison of the properties of the carborane-containing and phenyl-containing derivatives of mefenamic acid. The three isomers (ortho, meta, and para) were used to evaluate whether the properties of the compounds are influenced by the stability of the clusters.21 The corresponding nido-analogue of mefenamic acid (5) was synthesized taking into consideration that deboronation can occur under basic conditions28 and improves the solubility in aqueous media. The products were fully characterized and tested in vitro for their COX-isoform selective inhibitory potential and their cytotoxic activity.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Chemical Design Concept

Mefenamic acid (1) consists of two substituted phenyl rings linked by an NH bridge (Scheme 1). In this work, the dimethyl-substituted phenyl ring was substituted with carborane for size enlargement and hydrophobicity.

2.1.1. Synthesis of the Carborane Analogues of Mefenamic Acid

A three-step synthesis was employed to obtain the carborane analogues of mefenamic acid, starting from halogenation of the cluster, followed by a Pd-catalyzed Buchwald–Hartwig-type B–N coupling with 2-aminobenzonitrile and subsequent hydrolysis of the nitrile under acidic conditions to afford the desired carboxylic acid derivatives. Furthermore, in the case of the ortho-analogue 2b, sodium fluoride-mediated deboronation of the cluster resulted in the nido-analogue 5.

For the synthesis of the halogenated products 2a–4a, we employed a slightly modified literature procedure.33,34 The iodination of isomers 3 and 4 was performed with 0.5 equiv of iodine (I2) in a 1:1 (v/v) mixture of HNO3/H2SO4 to afford the iodo-carboranes 3a and 4a in excellent yields. Moreover, as the coupling reactions of the ortho isomer using the respective iodinated cluster (9-I-1,2-C2B10H11) in the subsequent step were not successful, the brominated compound 2a was synthesized from 2 under similar conditions.

The B–N coupling of the halogenated carboranes via palladium catalysts was also reported before.35−38 Adopting the reaction conditions reported by Mukhin et al. for the amidation of 9-iodo-para-carborane,38 the coupled products 2b–4b were obtained in good yields. As a modification, we used a Pd(dba)2–BINAP–KOt-Bu system (BINAP = 2,2′-bis(diphenylphosphino)-1,1′-binaphthyl; dba = dibenzylideneacetone) in 1,4-dioxane as a catalyst to couple the halogenated meta and para isomers 3a and 4a with 2-aminobenzonitrile and obtained 3b in 57% yield and 4b in 62% yield. The coupling of the ortho isomer was not successful when 9-iodo-1,2-dicarba-closo-dodecaborane was used (see the Supporting Information, Table S2). However, reacting the brominated cluster 2a with the aryl amine in the SPhos-Pd-G3–SPhos–K3PO4 system (SPhos = 2-dicyclohexylphosphino-2′,6′-dimethoxybiphenyl; SPhos-Pd-G3 = 2-dicyclohexylphosphino-2′,6′-dimethoxybiphenyl [2-(2′-amino-1,1′-biphenyl)]palladium(II) methanesulfonate) in 1,4-dioxane as a catalyst afforded the desired product 2b in 30% yield. As it is obvious even from the yields of the products 3b (57%) and 4b (62%), the meta and para isomers were the most favorable substrates for the coupling reaction because of their chemical stability, while for the ortho isomer, the deboronation of the cluster under basic conditions represents a marked drawback.

The final step in the synthetic protocol was the acidic hydrolysis of the nitriles 2b–4b in refluxing aqueous H2SO4 (40 vol %) or a mixture of glacial acetic acid and aqueous H2SO4 (40 vol %), respectively, to obtain the final products 2c–4c in quantitative yield. The nitriles 2b–4b and carboxylic acids 2c–4c were fully characterized, and their structures were confirmed by single-crystal structure analysis (see the Supporting Information for all analogues and Figure 4 for 3b and 3c).

Figure 4.

Molecular structures of the meta-carborane analogues of the nitrile precursor (left, 3b) and mefenamic acid (right, 3c). Legend: beige, B; black, C; white, H; yellow, N; blue, O. The ortho and para isomers are presented in the Supporting Information.

The nido-carborane analogue of mefenamic acid (5) was quantitatively synthesized via deboronation of 2b by using sodium fluoride in a 2:3 (v/v) mixture of ethanol/water.

2.2. Biological Evaluation: Potential for COX Inhibition and Cytotoxicity

2.2.1. COX Inhibition Studies

Inhibition potency against ovine COX-1 and human COX-2 was investigated using the COX Fluorescent Inhibitor Screening Assay Kit (Cayman Chemical Company) and celecoxib (6) as a reference. An initial screening was performed utilizing both isoforms and the compounds 2b–4b and 2c–4c at a concentration of 100 μM.

Nitriles 2b–4b and carboxylic acids 2c–4c containing an intact carborane cluster were found to be rather inactive. For this group, lack of inhibition or percent inhibition below 50% did not necessitate further IC50 determination. Interestingly, the nido-carborane-based nitrile 5 showed markedly higher inhibition of 83 and 76% for COX-1 and COX-2, respectively, at 100 μM. Subsequent IC50 determination revealed rather nonselective inhibition of both enzymes with an IC50(COX-1) of 40 μM and an IC50(COX-2) of 33 μM (Table 1).

Table 1. COX Inhibition of Compounds 2b–4b, 2c–4c, and 5 as well as the References Mefenamic Acid (1) and Celecoxib (6).

| % inhibition

@ 100 μMa |

IC50 [μM] |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| COX-1 | COX-2 | COX-1 | COX-2 | |

| 2b | 32 | 28 | ||

| 3b | 22 | 13 | ||

| 4b | 12 | n. i. | ||

| 2c | n. i. | n. i. | ||

| 3c | 11 | n. i. | ||

| 4c | 7 | n. i. | ||

| 5 | 83 | 76 | 40 | 33 |

| 1b | 59 | 20 | 0.12 | |

| 6c | >100 | 0.10 | ||

% Inhibition values lower than 5% or negative values compared to the initial activity in the absence of an inhibitor were interpreted as “no inhibition” (n. i.).

Ambiguous COX inhibition. For COX-2, no IC50 could be determined.

Celecoxib (6) served as the reference. The pIC50 (pIC50 = −log10(IC50 [M])) was found to be 6.97 ± 0.31 (mean ± SD, n = 4; IC50 = 100 ± 78 nM).

Notably, mefenamic acid (1) gave ambiguous results within this assay. While an IC50(COX-1) value of 0.12 μM was in general agreement with the literature value of 1.94 μM in blood,39 inhibition showed a plateau of around 60% in a concentration range between 1 and 100 μM. For COX-2, no IC50 value could be determined due to similar and even decreasing inhibition values with increasing concentrations (see Figure S80, Supporting Information).

Further efforts were performed to determine COX inhibition in the presence of bovine serum albumin (BSA) as a solubilizer (for a more detailed discussion, see the Supporting Information). Briefly, these experiments showed that high concentrations of BSA in the range of 100 μM to 2 mM interfered with the COX assay due to apparent complete inhibition of COX activity itself. Under optimized conditions, concentrations of 10 μM BSA or lower were tolerated and allowed investigation of COX inhibition in the presence of BSA, i.e., for SC560, 2b, 3b, and 5, but revealed no marked differences in the inhibition pattern in the presence or absence of BSA. However, for inhibitor concentrations higher than 10 μM, principally no equimolar BSA concentration could be applied in this setting.

2.2.2. Cytotoxicity

Treatment of four colon cancer cell lines (mouse CT26, human HT-29, SW480, and HCT116), differing in the status of COX-2 expression, with the range of concentrations of mefenamic acid derivatives 2b–4b, 2c–4c, and 5 revealed a dose-dependent decrease of cell viability after 72 h of incubation. The carborane-containing compounds were more efficient in suppressing cancer cell growth than mefenamic acid (Table 2 and Figure S84, Supporting Information).

Table 2. IC50 Values (μM) of Compounds on Tested Cancer Cell Lines.

| cell line | CT26 |

HT29 |

SW480 |

HCT116 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COX-2 | + |

+ |

– |

– |

||||

| MTT | CV | MTT | CV | MTT | CV | MTT | CV | |

| 1 | 114 ± 4.2 | 163 ± 2.0 | >200 | >200 | 104 ± 6.4 | 120 ± 6.1 | 96.2 ± 7.9 | 101 ± 6.5 |

| 2b | 38.3 ± 0.4 | 47.2 ± 2.3 | 45.6 ± 2.7 | >200 | 39 ± 1.2 | 24 ± 0.8 | 34.4 ± 1.8 | 35.5 ± 3.1 |

| 3b | 22.4 ± 1.7 | 37.4 ± 1.2 | 46.4 ± 2.9 | 116 ± 2.2 | 23.8 ± 2.1 | 24.9 ± 1.8 | 28.2 ± 1.8 | 31.8 ± 2.3 |

| 4b | >200 | >200 | >200 | >200 | >200 | >200 | >200 | >200 |

| 2c | 61.6 ± 0.1 | 93.3 ± 5.7 | 183 ± 3.7 | >200 | 77.6 ± 0.1 | 75.6 ± 4.0 | 74.6 ± 4.8 | 83.6 ± 3.8 |

| 3c | 76.5 ± 2.8 | 160 ± 6.6 | 184 ± 4.5 | >200 | 90.6 ± 3.3 | 117 ± 7.9 | 93.2 ± 7.6 | 147 ± 8.6 |

| 4c | 72.6 ± 4.5 | 137 ± 3.1 | 165 ± 0.3 | >200 | 77.8 ± 0.4 | 76.4 ± 3.5 | 67.6 ± 1.3 | 77.4 ± 3.4 |

| 5 | 167 ± 8.8 | 150 ± 4.9 | 141 ± 7.8 | 182 ± 1.7 | 121 ± 4.5 | 84 ± 3.3 | 129 ± 10 | 115 ± 6.0 |

According to the literature data, the cytotoxic potential of mefenamic acid varied from 100 to 200 μM (Chang and Huh-7, liver and pancreatic tumor cell lines) to approximately 20 μM in the case of human breast, bladder, and non-small lung cancer cell lines.18,19 Based on the mentioned data, IC50 values detected on colon cancer cell lines in this study were placed in the higher micromolar range. In general, the activity of the nitrile carborane derivatives was more potent in comparison to carboxylic counterparts. Therefore, compounds 2b and 3b were selected as the most potent as estimated on the basis of both 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl-2H-tetrazonium bromide (MTT) and crystal violet (CV) assays (Supporting Information, Figure S84). Exposure of primary peritoneal exudate cells to 2b and 3b showed that in contrast to 3b, which decreased the viability of primary cells in the same manner as tumor cells, compound 2b did not disturb the viability of primary cells in the range of doses up to 200 μM, indicating the selectivity of this compound toward the malignant phenotype (see Table S10, Supporting Information).

Given that 2b and 3b were the most potent against HCT116 and SW480 that are COX-2-negative cell lines and less potent against COX-2-positive cells (CT26 and HT29), it is plausible to assume that their cytotoxic action is unrelated to the inhibition of this enzyme. In concordance, low COX-2 inhibitory potential (Table 1 and Figure S84, Supporting Information) also suggests that their antitumor activity is probably COX-2-independent.

Numerous examples in the literature describe the existence of direct intracellular targets of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and COX-2 inhibitors that are independent of COX-2 but can be crucial for realization of their cytostatic/toxic action against cancer cells.40,41 Namely, an alternative target for different NSAIDs is cyclic-guanosine monophosphate phosphodiesterase, which is further involved in regulation of the signaling network, causing the activation of protein kinase G (PKG), one of the leading regulators of an apoptotic process. This molecule amplified the proapoptotic signal through β-catenin degradation, MEKK1 and JNK activation, and inactivation of antiapoptotic Bcl-2 protein. In addition, it was shown that one of NSAID targets is the retinoic X receptor that subsequently blocked Akt signaling. The proapoptotic effect of NSAIDs can be realized by direct modulation of NFkB, which is known as a link between inflammation and tumorigenesis.

The cell division rate of HCT116 and SW480 cells exposed to an IC50 dose of 2b or 3b was remarkably lower in comparison to untreated cells and similar to those observed upon exposure of cells to an IC50 concentration of mefenamic acid. In parallel, intensified apoptosis triggered by 2b and 3b was more evident on the SW480 cell line than the HCT116 cell line, with a dominant effect of 2b.

Apoptosis was followed by moderate activation of caspases in both cell lines (Figure 5). Using a fluorescence-labeled pan-caspase inhibitor, caspase activation in 0.5, 1.1, and 5.6% HCT116 cells treated with an IC50 dose of mefenamic acid, 2b, and 3b, respectively, was detected. In SW480 cells, treatment with mefenamic acid, 2b, and 3b resulted in caspase activation in 5.2, 3.2, and 6.8% cells, respectively.

Figure 5.

Effects of 2b and 3b on the proliferation and apoptotic process. HCT116 and SW480 cells were exposed to an IC50 dose of 2b or 3b and mefenamic acid (MEFA). (A, B) Cell proliferation, (C, D) apoptotic cell fraction, and (E, F) caspase activation were evaluated after 72 h of treatment. Data are representative from three independent experiments. CFSE, carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester; Annexin V-FITC, Annexin V conjugated to fluorescein isothiocyanate; PI, propidium iodide; Apostat, FITC-conjugated pan-caspase inhibitor.

Remarkably, all treatments led to a strong autophagic response in HCT116 cells, while the potentiation of autophagy was less pronounced in SW480 cells; these results suggest that autophagy opposes apoptotic cell death (see Figure S85, Supporting Information). It is a well-described phenomenon in which an autophagic process serves as a cell-protective mechanism preventing cell death by removal and recycling of damaged intracellular structures.42 Neutralization of autophagy by addition of the specific inhibitor chloroquine further potentiated the drug’s cytotoxicity, confirming the cytoprotective role of this process. Measurement of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (ROS/RNS) upon treatment with 2b and 3b showed that ROS/RNS production is potentiated only by exposure to 2b (Figure 6). Since ROS/RNS are known cytodestructive molecules,43,44 they can be at least partly responsible for apoptotic cell death induced by treatment with 2b, but not for 3b. One of the main reasons for the results concerning ROS/RNS tests could be the time-dependent deboronation of 2b in cell culture medium, which has a slightly basic pH value.

Figure 6.

HCT116 and SW480 cells were exposed to an IC50 dose of 2b, 3b, and mefenamic acid (MEFA, 1), and ROS/RNS production was evaluated after 72 h of treatment. Treatment with 2b increased ROS/RNS production in both HCT116 and SW480 cells. Representative data from three independent experiments are presented.

3. Conclusions

Carborane analogues of mefenamic acid (1) bearing nitrile (2b–4b) or carboxylic acid moieties (2c–4c) were prepared employing the three isomers (ortho, meta, and para). Furthermore, the nido derivative 5 was successfully synthesized from the closo compound 2b. The nido-carborane analogue 5 exhibited markedly high COX inhibition of 80 and 76% for COX-1 and COX-2 at 100 μM concentration, respectively, while the other derivatives were found to be rather inactive. The carborane-containing derivatives have stronger antitumor potential compared to mefenamic acid with the nitriles 2b and 3b being the most potent. Their tumoricidal action against HCT116 and SW480 is based on inhibition of cell division and resulting apoptosis, while all cells involve autophagy to counteract the cytotoxic action of 2b and 3b.

4. Experimental Part

4.1. Synthesis

4.1.1. Materials and Methods

All commercially available reagents were purchased from common suppliers and used without further purification. Reactions including carboranes were carried out under a nitrogen atmosphere using the Schlenk technique. For column chromatography, silica gel (60 Å) from Acros was used. The particle size was in the range of 0.035–0.070 mm. Reactions were monitored by thin-layer chromatography (TLC) using silica gel 60 F254-coated glass plates from Merck. Carborane-containing compounds were stained with 5% solution of palladium dichloride in methanol. 1,4-Dioxane was dried over CaH2 and further distilled over sodium benzophenone ketyl prior to use.

NMR data were collected with an Avance DRX 400 spectrometer (1H-NMR, 400.13 MHz; 13C-NMR, 100.63 MHz; 11B-NMR, 128.38 MHz) or an Ascend 400 spectrometer (1H-NMR, 400.16 MHz; 13C-NMR, 100.63 MHz; 11B-NMR, 128.38 MHz) from Bruker. The 1H- and 13C-NMR spectra were referenced to tetramethylsilane (TMS) and the 11B-NMR spectra to the Ξ scale.45 Deuterated solvents were purchased from Eurisotop with a deuteration rate of 99.80%. The chemical shifts are reported in parts per million (ppm).

High-resolution ESI mass spectrometry (HR-ESI-MS) was carried out on an Impact II from Bruker Daltonics. The simulation of the mass spectra was conducted with a web-based program from Scientific Instrument Services Inc. (Palmer, MA, USA).46

The IR spectra were obtained with a Nicolette IS5 (ATR) from Thermo Fisher (Waltham, MA, USA). The signal intensity was classified as weak (w), medium (m), or strong (s).

Analytical HPLC was performed with the following system: column Luna C18 (Phenomenex, 250 × 4.6 mm, 5 μm) with a guard column, Agilent 1200 HPLC: pump G1311A, auto sampler G1329A, column oven G1316A, degasser G1322A, UV detector G1315D, γ detector Gabi Star (Raytest), flow rate = 1 mL/min, (A) MeCN/(B) H2O + 0.1% TFA (trifluoroacetic acid), gradient t0 min 45/55, t3.0 min 45/55, t28.0 min 95/5, t34.0 min 95/5, t35.0 min 45/55, t40.0 min 45/55. The products were monitored at λ = 254 nm.

Data for X-ray structures were collected on a Gemini diffractometer (Rigaku Oxford Diffraction) using Mo-Kα radiation (λ = 71.073 pm). Data reduction was performed with CrysAlis Pro47 including the program SCALE3 ABSPACK48 for empirical absorption correction. All structures were solved by dual-space methods with SHELXT-201849 and refined with SHELXL-2018.50 Nonhydrogen atoms were refined with anisotropic thermal parameters, and a difference-density Fourier map was used to locate hydrogen atoms. Carborane carbon atoms were localized with a bond length and displacement parameter analysis. Further details and CCDC numbers are given in the Supporting Information.

The halogenated products 2a–4a were prepared according to slightly modified literature procedures (for details, see the Supporting Information).33,34

4.1.2. B–N Coupling of Halo-Carboranes

The general procedure for B–N coupling of halo-carboranes 2a–4a was similar for all the isomers.

A Schlenk flask was charged with 0.3–1 mmol of the corresponding halo-carborane (2a–4a), 2-aminobenzonitrile, base, catalyst, and ligand, and the mixture was suspended in 3–10 mL of 1,4-dioxane. Then, the flask was placed in a preheated oil bath and the mixture was stirred for 18–46 h at 70 or 95 °C, respectively. The reaction was monitored by TLC (silica gel, n-hexane/ethyl acetate, 4:1 (v/v)). In the end, the turbid brown mixture was cooled to room temperature and was diluted with diethyl ether. The resulting suspension was filtered through a silica pad. The filtrate was collected, and the solvent was evaporated under reduced pressure to give the crude product as an orange solid or paste. The crude products were further purified via column chromatography (silica gel, n-hexane/ethyl acetate, 1:0 → 4:1 (v/v)). From the pure fractions, single crystals were obtained by layering a saturated dichloromethane solution of the product with n-hexane.

N-(1,2-Dicarba-closo-dodecaboran-9-yl)-2-benzonitrile (2b) was synthesized from 2a (223 mg, 1 mmol), 1 equiv of amine (118 mg, 1 mmol), 4 equiv of K3PO4 (849 mg, 4 mmol), 5 mol % SPhos-Pd-G3, and SPhos in 3 mL of dry 1,4-dioxane. The mixture was stirred at 70 °C for 46 h. 2b was obtained as a light yellow powder. Yield: 30% (79 mg, 0.30 mmol). Mp: 158–159 °C. 1H-NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): δ = 1.56–3.16 (br, 9H, BH), 3.47 (br s, 1H, CH-cluster), 3.53 (br s, 1H, CH-cluster), 4.40 (s, 1H, NH), 6.65 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H, CH), 7.21−7.35 (m, 3H, CH) ppm. 13C{1H}-NMR (CDCl3, 101 MHz): δ = 43.5 (CH, C-cluster), 50.3 (CH, C-cluster), 97.7 (C, C–1), 113.7 (CH, C–3), 116.8 (C, CN), 118.3 (CH, C–5), 132.6 (CH, C–6), 133.6 (CH, C–4), 150.9 (C, C–2) ppm. 11B{1H}-NMR (CDCl3, 128 MHz): δ = −16.7 (s, 2B, BH), −15.7 (s, 2B, BH), −14.7 (s, 2B, BH), −9.7 (s, 2B, BH), −3.4 (s, 1B, BH), 7.8 (s, 1B, BN) ppm. 11B-NMR (CDCl3, 128 MHz): δ = −16.8 (d, J = 152.3 Hz, 2B), −15.7 (d, J = 130.5 Hz, 2B), −14.6 (d, J = 149.8 Hz, 2B), −9.7 (d, J = 151.1 Hz, 2B), −3.4 (d, J = 149.6 Hz, 1B), 7.8 (s, 1B, BN) ppm. HR-ESI-MS (positive mode, in acetonitrile) m/z [M + H]+: calculated, 261.2386; found, 261.2340; the observed isotopic pattern was in agreement with the calculated one. HPLC tR = 21.25 min; purity: 99.5% relative area. IR: ṽ (ATR): 3398 (m, NH), 3050 (s, CH-cluster), 2591 (s, BH), 2210 (m, CN), 1601–1430 (m-w, CC), and 751 (m, BB) cm–1. The Rf of 2b in the mixture of n-hexane/ethyl acetate (7:3 (v/v)) is 0.37.

N-(1,7-Dicarba-closo-dodecaboran-9-yl)-2-benzonitrile (3b) was synthesized from 3a (81 mg, 0.3 mmol), 1 equiv of amine (35.4 mg, 0.3 mmol), 1.2 equiv of KOt-Bu (40.4 mg, 0.36 mmol), 20 mol % Pd(dba)2, and BINAP in 4 mL of dry 1,4-dioxane. The mixture was stirred at 95 °C for 21 h. 3b was obtained as a light yellow powder. Yield: 57% (44.5 mg, 0.17 mmol). Mp: 116–118 °C. 1H-NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): δ = 1.91–3.26 (br, 9H, BH), 2.90 (br s, 2H, CH-cluster), 4.50 (s, 1H, NH), 6.68 (t, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H, CH), 7.29−7.38 (m, 4H, CH) ppm. 13C{1H}-NMR (CDCl3, 101 MHz): δ = 51.1 (CH, C-cluster), 97.8 (C, C–1), 113.8 (CH, C–3), 116.8 (C, CN), 118.2 (CH, C–5), 132.6 (CH, C–6), 133.6 (CH, C–4), 151.0 (C, C–2) ppm. 11B{1H}-NMR (CDCl3, 128 MHz): δ = −23.0 (s, 1B, BH), −19.1 (s, 1B, BH), −15.4 (s, 2B, BH), −14.3 (s, 2B, BH), −11.2 (s, 1B, BH), −7.5 (s, 2B, BH), 1.4 (s, 1B, BN) ppm. 11B-NMR (CDCl3, 128 MHz): δ = −23.0 (d, J = 182.7 Hz, 1B), −19.1 (d, J = 182.5 Hz, 1B), −15.4 (d, J = 161.3 Hz, 2B), −14.2 (d, J = 153.6 Hz, 2B), −11.2 (d, J = 151.2 Hz, 1B), −7.5 (d, J = 162.8 Hz, 2B), 1.4 (s, 1B, BN) ppm. HR-ESI-MS (positive mode, in acetonitrile) m/z [M + H]+: calculated, 261.2386; found, 261.2410; the observed isotopic pattern was in agreement with the calculated one. HPLC tR = 22.30 min; purity: 98.9% relative area. IR: ṽ (ATR): 3394 (m, NH), 3052 (s, CH-cluster), 2599 (s, BH), 2207 (m, CN), 1606–1429 (m-w, CC), and 754 (m, BB) cm–1. The Rf of 3b in n-hexane/ethyl acetate (4:1 (v/v)) is 0.33.

N-(1,12-Dicarba-closo-dodecaboran-2-yl)-2-benzonitrile (4b) was synthesized from 4a (162 mg, 0.6 mmol), 1 equiv of amine (70.8 mg, 0.6 mmol), 1.2 equiv of KOt-Bu (80.8 mg, 0.72 mmol), 20 mol % Pd(dba)2, and BINAP in 10 mL of dry 1,4-dioxane. The mixture was stirred at 95 °C for 18.5 h. 4b was obtained as a white powder. Yield: 62% (97.1 mg, 0.37 mmol). Mp: 133–134 °C. 1H-NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): δ = 1.41–3.11 (br, 9H, BH), 2.87 (br s, 1H, CH-cluster), 3.15 (br s, 1H, CH-cluster), 4.65 (s, 1H, NH), 6.79 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H, CH), 7.40−7.52 (m, 3H, CH) ppm. 13C{1H}-NMR (CDCl3, 101 MHz): δ = 62.2 (CH, C-cluster), 68.5 (CH, C-cluster), 98.8 (C, C–1), 114.7 (CH, C–3), 117.8 (C, CN), 118.3 (C, C-5), 132.6 (CH, C–6), 133.8 (CH, C–4), 150.1 (C, C–2) ppm. 11B{1H}-NMR (CDCl3, 128 MHz): δ = −20.4 (s, 1B, BH), −16.7 (s, 2B, BH), −15.7 (s, 4B, BH), −14.7 (s, 2B, BH), −4.0 (s, 1B, BN) ppm. 11B-NMR (CDCl3, 128 MHz): δ = −20.5 (d, J = 169.8 Hz, 1B), −17.4 to −14.1 (br, J = 153.8, 144.8, 8B), −3.9 (s, 1B, BN) ppm. HR-ESI-MS (positive mode, in acetonitrile) m/z [M + H]+: calculated, 261.2386; found, 261.2360; the observed isotopic pattern was in agreement with the calculated one. HPLC tR = 24.83 min; purity: 98.6% relative area. IR: ṽ (ATR): 3363 (m, NH), 3052 (s, CH-cluster), 2602 (s, BH), 2215 (m, CN), 1603–1435 (m-w, CC), and 745 (m, BB) cm–1. The Rf of 4b in the mixture of n-hexane/ethyl acetate (4:1 (v/v)) is 0.81.

4.1.3. Hydrolysis of the Nitriles

The general procedure for the hydrolysis of the nitrile analogues was similar for all the isomers.

In a 25 mL round-bottom flask, 0.07–0.23 mmol of the nitrile derivative (2b–4b) was dissolved in glacial acetic acid and then an aqueous solution of sulfuric acid (aq H2SO4, 40 vol %) was added in one portion. The flask was connected to a condenser and placed into a preheated oil bath. The reaction mixture was stirred at 120 °C for 7–23 h. The reaction was monitored by TLC (silica gel, n-hexane/ethyl acetate, 7:3 (v/v)). After completion, the reaction mixture was cooled down to room temperature and diluted with ice-cold water, forming a suspension that was extracted with diethyl ether. The organic phase was collected, dried over MgSO4, filtered, and evaporated to dryness to yield the crude product as a white to yellowish-white powder. The crude product was further purified via column chromatography (silica gel, n-hexane/ethyl acetate, 7:3 (v/v)). From the pure fractions, single crystals were obtained by dissolving the product in a small amount of dichloromethane and layering with n-hexane.

N-(1,2-Dicarba-closo-dodecaboran-9-yl)-2-benzoic acid (2c) was synthesized from 2b (17 mg, 0.1 mmol) in 6 mL of 40 vol % aqueous solution of H2SO4 and 10 mL of glacial acetic acid. The mixture was stirred at 120 °C for 23 h. 2c was obtained as a light gray powder. Yield: 89% (16.9 mg, 0.06 mmol). Mp: 236–237 °C. 1H-NMR ((CD3)2CO, 400 MHz): δ = 1.84–2.98 (br, 9H, BH), 4.49 (br s, 2H, CH-cluster), 6.57 (m, 1H, CH), 7.29 (m, 2H, CH), 7.89 (m, 1H, CH), 8.05 (s, 1H, NH), 10.9 (br s, 1H, OH) ppm. 13C{1H}-NMR ((CD3)2CO, 101 MHz): δ = 44.3 (CH, C-cluster), 51.9 (CH, C-cluster), 110.9 (C, C–1), 114.6 (CH, C–3), 114.9 (CH, C–5), 131.8 (CH, C–6), 133.8 (CH, C–4), 152.6 (C, C–2), 169.9 (C, COOH) ppm. 11B{1H}-NMR ((CD3)2CO, 128 MHz): δ = −16.5 (s, 2B, BH), −15.9 (s, 2B, BH), −14.6 (s, 2B, BH), −10.1 (s, 2B, BH), −4.1 (s, 1B, BH), 7.8 (s, 1B, BN) ppm. 11B-NMR ((CD3)2CO, 128 MHz): δ = −16.2 (d, J = 186.9 Hz, 2B), −15.9 (d, J = 154.8 Hz, 2B), −14.6 (d, J = 167.6 Hz, 2B), −10.1 (d, J = 148.8 Hz, 2B), −4.1 (d, J = 147.7 Hz, 1B), 7.8 (s, 1B, BN) ppm. HR-ESI-MS (negative mode, in acetonitrile) m/z [M – H]−: calculated, 278.2184; found, 278.2190; the observed isotopic pattern agreed with the calculated one. HPLC tR = 16.62 min; purity: 98.5% relative area. IR: ṽ (ATR): 3312 (m, NH), 3300–2500 (s, vbr, OH), 2922 (s, CH-cluster), 2611 (s, BH), 1643 (s, CO), 1576–1407 (m-w, CC), and 747 (m, BB) cm–1. The Rf of 2c in the mixture of n-hexane/ethyl acetate (7:3 (v/v)) is 0.22.

N-(1,7-Dicarba-closo-dodecaboran-9-yl)-2-benzoic acid (3c) was synthesized from 3b (60 mg, 0.2 mmol) in 11.5 mL of 40 vol % aqueous solution of H2SO4. The suspension was stirred at 120 °C for 19.5 h. 3c was obtained as a white powder. Yield: 91% (58 mg, 0.21 mmol). Mp: 219–220 °C. 1H-NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): δ = 1.56–2.98 (br, 9H, BH), 2.87 (br s, 2H, CH-cluster), 6.63 (m, 1H, CH), 7.35 (m, 2H, CH), 7.85 (s, 1H, NH), 7.97 (m, 1H, CH), 10.4 (br s, 1H, OH) ppm. 13C{1H}-NMR (CDCl3, 101 MHz): δ = 29.7 (CH, C-cluster), 50.9 (CH, C-cluster), 110.2 (C, C–1), 115.3 (CH, C–3), 115.4 (CH, C–5), 132.4 (CH, C–6), 134.8 (CH, C–4), 153.1 (C, C–2), 172.6 (C, COOH) ppm. 11B{1H}-NMR (CDCl3, 128 MHz): δ = −23.2 (s, 1B, BH), −19.1 (s, 1B, BH), −15.5 (s, 2B, BH), −14.2 (s, 2B, BH), −11.2 (s, 1B, BH), −7.4 (s, 2B, BH), 1.7 (s, 1B, BN) ppm. 11B-NMR (CDCl3, 128 MHz): δ = −23.6 (d, J = 182.7 Hz, 1B), −19.1 (d, J = 182.0 Hz, 1B), −15.5 (d, J = 167.7 Hz, 2B), −14.2 (d, J = 168.9 Hz, 2B), −11.2 (d, J = 151.3 Hz, 1B), −7.4 (d, J = 160.8 Hz, 2B), 1.7 (s, 1B) ppm. HR-ESI-MS (negative mode, in acetonitrile) m/z [M – H]−: calculated, 278.2184; found, 278.2180; the observed isotopic pattern agreed with the calculated one. HPLC tR = 18.40 min; purity: 99.5% relative area. IR: ṽ (ATR): 3304 (m, NH), 3300–2500 (s, vbr, OH), 3051 (s, CH-cluster), 2598 (s, BH), 1651 (s, CO), 1578–1408 (m-w, CC), and 742 (m, BB) cm–1. The Rf of 3c in the mixture of n-hexane/ethyl acetate (4:1 (v/v)) is 0.24.

N-(1,12-Dicarba-closo-dodecaboran-2-yl)-2-benzoic acid (4c) was synthesized from 4b (39 mg, 0.15 mmol) in 8 mL of 40 vol % aqueous solution of H2SO4 and 15 mL of glacial acetic acid. The mixture was stirred at 120 °C for 7 h and further for 17 h at 90 °C. 4c was obtained as a white powder. Yield: 57% (25 mg, 0.09 mmol). Mp: 227–228 °C. 1H-NMR ((CD3)2CO, 400 MHz): δ = 0.90–3.0 (br, 9H, BH), 3.47 (br s, 1H, CH-cluster), 3.77 (br s, 1H, CH-cluster), 6.74 (ddd, J = 8.1, 7.0, 1.2 Hz, 1H, CH), 7.46 (ddd, J = 8.7, 7.0, 1.7 Hz, 1H, CH), 7.57 (dd, J = 8.6, 1.2 Hz, 1H, CH), 7.96 (dd, J = 8.0, 1.7 Hz, 1H, CH), 8.42 (s, 1H, NH), 11.1 (br s, 1H, OH) ppm. 13C{1H}-NMR ((CD3)2CO, 101 MHz): δ = 61.9 (CH, C-cluster), 73.0 (CH, C-cluster), 113.5 (C, C–1), 115.4 (CH, C–3), 116.5 (CH, C–5), 131.8 (CH, C–6), 134.2 (CH, C–4), 151.3 (C, C–2), 169.9 (C, COOH) ppm. 11B{1H}-NMR ((CD3)2CO, 128 MHz): δ = −21.1 (s, 1B, BH), −16.9 (s, 2B, BH), −15.8 (s, 4B, BH), −14.6 (s, 2B, BH), −3.3 (s, 1B, BN) ppm. 11B-NMR ((CD3)2CO, 128 MHz): δ = −21.0 (d, J = 170.6 Hz, 1B), −16.9 (d, J = 153.6 Hz, 2B), −15.8 (d, J = 153.6 Hz, 4B), −14.6 (d, J = 157.4 Hz, 2B), −3.3 (s, 1B, BN) ppm. HR-ESI-MS (negative mode, in acetonitrile) m/z [M – H]−: calculated, 278.2184; found, 278.2190; the observed isotopic pattern agreed with the calculated one. HPLC tR = 21.86 min; purity: 98.6% relative area. IR: ṽ (ATR): 3304 (m, NH), 3300–2500 (s, vbr, OH), 2921 (s, CH-cluster), 2597 (s, BH), 1660 (s, CO), 1578–1403 (m-w, CC), and 741 (m, BB) cm–1. The Rf of 4c in the mixture of n-hexane/ethyl acetate (4:1 (v/v)) is 0.32.

4.1.4. Deboronation of 2b

In a 25 mL round-bottom flask, a mixture of 5 mL of ethanol/water (3:2 (v/v)) was degassed for 30 min under a nitrogen flow. Then, 2b (50 mg, 0.19 mmol) and NaF (39.8 mg, 0.95 mmol) were added and the resulting mixture was stirred at 90 °C for 6 h. In the end, the reaction mixture was cooled to room temperature and was concentrated under reduced pressure. The desired product 5 was precipitated with water. The precipitate was isolated by vacuum filtration, further washed with ice-cold water, and dried under high vacuum to yield the nido derivative 5 quantitatively as a white powder.

Sodium rac-[N-(7,8-dicarba-closo-dodecaboran-6-yl)-2-benzonitrile] (5): Mp: 248–249 °C. 1H-NMR ((CD3)2SO, 400 MHz): δ = 0.31–1.75 (br, 8H, BH), 1.56 (br s, 1H, CH-cluster), 1.75 (br s, 1H, CH-cluster), 6.51 (s, 1H, NH), 7.18−7.31 (m, 4H, CH) ppm. 11B{1H}-NMR ((CD3)2SO, 128 MHz): δ = −37.5 (s, 1B, BH), −31.3 (s, 1B, BH), −24.2 (s, 1B, BH), −22.2 (s, 1B, BH), −21.2 (s, 1B, BH), −18.9 (s, 1B, BH), −14.1 (s, 1B, BH), −11.6 (s, 1B, BH), −0.6 (s, 1B, BN) ppm. 11B-NMR ((CD3)2SO, 128 MHz): δ = −37.5 (d, J = 140.3 Hz, 1B), −31.3 (d, J = 119.1 Hz, 1B), −24.2 (d, J = 156.2 Hz, 1B), −22.2 (d, J = 131.8 Hz, 1B), −21.2 (d, J = 140.8 Hz, 1B), −18.9 (d, J = 161.3 Hz, 1B), −14.1 (d, J = 137.5 Hz, 1B), −11.6 (d, J = 134.6 Hz 1B), −0.6 (s, 1B, BN) ppm. HR-ESI-MS (negative mode, in acetonitrile) m/z [M – Na]−: calculated, 250.2212; found, 250.2200; the observed isotopic pattern agreed with the calculated one. HPLC tR = 17.53 min; purity: 97.1% relative area. IR: ṽ (ATR): 3208 (m, NH), 2977 (s, CH-cluster), 2535 (s, BH), 2247 (w, CN), 1587–1455 (m-w, CC), and 756 (m, BB) cm–1. The Rf of 5 in ethyl acetate is 0.45.

4.2. Biological Evaluation

4.2.1. Evaluation for COX Inhibition

The COX inhibition activity against ovine COX-1 and human COX-2 was determined using the fluorescence-based COX assay COX Fluorescent Inhibitor Screening Assay Kit (Cayman Chemical Company, Ann Arbor, MI, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions as previously reported by us.22

4.2.2. Evaluation for Cytotoxicity

4.2.2.1. Materials and Methods

Cell culture medium RPMI-1640, fetal bovine serum (FBS), and penicillin/streptomycin 100× solution (working solution: 100 units/mL penicillin and 100 μg/mL streptomycin) were obtained from Capricorn Scientific (Ebsdorfergrund, Germany). Trypsin (powder), sterile-filtered cell culture-grade dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT), crystal violet (CV), and propidium iodide (PI) were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA). Annexin V-FITC was from BD Pharmingen (San Diego, CA USA), ApoStat was purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN, USA), and acridine orange (AO) was from Labo-Moderna (Paris, France). Carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE) and dihydrorhodamine 123 (DHR) were obtained from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA, USA). Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and trypsin solution for cell detachment were made in-house.

Tumor cell lines used in this study were mouse colon carcinoma cell line CT26, human colorectal adenocarcinoma cell lines HT-29 and SW480, and human colorectal carcinoma cell line HCT116. All tumor cell lines were cultivated in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% FCS and antibiotics (culture medium) at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2. Peritoneal macrophages were collected from the peritoneal cavity of Balb/C mice from the Institute for Biological Research “Siniša Stanković” (IBISS), University of Belgrade, Serbia, by cavity rinse with ice-cold PBS. Macrophages were cultivated in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 5% FCS and antibiotics at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2. The handling of animals and protocols for obtaining macrophages is in agreement with the rules of European Union and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at IBISS (no. 02-09/16).

For cell treatments, mefenamic acid (1) and its carborane-containing analogues (2b–4d, 3c–4c, and 5) were dissolved in DMSO and stock solutions (200 mM) were kept at −20 °C for a maximum period of 1 month. Working solutions were prepared in culture medium just before the treatment; the highest concentration of DMSO was 0.1%.

4.2.2.2. Viability Tests

Cytotoxicity was determined by MTT and CV assays using cell viability as an indicator.51 All measurements were carried out in triplicate.

CT26 cells (4 × 103/well), HT-29 (1.5 × 104/well), SW480 (3 × 103/well), the human colorectal carcinoma cell line HCT116 (5 × 103/well), and primary mouse peritoneal macrophages (1.5 × 105/well) were seeded in 96-well plates and left to adhere overnight before being treated for 72 h with a 0–200 μM dose range of mefenamic acid and its carborane-containing analogues (2b–4d, 2c–4c, and 5). MTT and CV tests were performed as described elsewhere.52 To determine the outcome of induced autophagy, HCT116 and SW480 cells were treated with an IC50 dose of 2b–4d, 2c–4c, and 5 or mefenamic acid concurrently with the autophagy inhibitor chloroquine (20 μM). Cell viability was assessed by CV tests after 72 h for HCT116 or 48 h for SW480 cells.

4.2.2.3. Flow Cytometry Analysis

For flow cytometry analyses, HCT116 (2 × 105/well) and SW480 (1.5 × 105/well) cells were seeded in six-well plates and treated with an IC50 dose of 2b, 3b, or mefenamic acid (1) for 72 h (or 48 h for autophagy detection in SW480 cells). For evaluation of the rate of cancer cell proliferation when exposed to test compounds, HCT116 and SW480 cells were prelabeled with 1 μM CFSE. At the end of the treatment, for the detection of apoptosis, cells were double-stained with Annexin V-FITC and PI (15 μg/mL) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. To check if apoptotic cell death was accompanied by caspase activation, cells were stained with a fluorescently labeled pan-caspase inhibitor, ApoStat, according to the manufacturer’s protocol. For detection of treatment-induced autophagy, cells were collected at the end of the treatment, stained with 10 μM AO solution for 15 min at 37 °C, and washed thoroughly with PBS before flow cytometry analysis. For detection of intracellular ROS/RNS production, cells were treated with 2b, 3b, or mefenamic acid (1) in the presence of 1 μM DHR in culture medium. Flow cytometry analyses were performed with a Partec Flow Cytometer, and data were analyzed using FlowJo software (Tree Star).

Acknowledgments

M.L. and J.P. thank the Helmholtz Association for funding a part of this work through the Helmholtz Cross-Program Initiative “Technology and Medicine–Adaptive Systems”. The excellent technical assistance of Mareike Barth, Johanna Wodtke, and Catharina Knöfel is greatly acknowledged.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.2c01523.

Spectroscopic and spectrometric analysis; solubility and stability tests; modeling of the interaction of carboranyl analogues of mefenamic acid with the solubilizing agent; further COX inhibition tests and cytotoxicity results (PDF)

Crystallographic data and crystal structures of carboranyl analogues (2b–4b and 2c–4c) (CIF)

Author Contributions

L.U. and E.H.-H. carried out the conceptualization. L.U., M.M., M.L., J.D., and P.L. provided the methodology. L.U., M.M., D.M.-I., S.M., M.B.S., and M.L. performed the validation. L.U., M.M., M.L., D.M.-I., and P.L. conducted the formal analysis. J.P., D.M-I., and E.H.-H. provided the resources. L.U. prepared the original draft of the manuscript. All authors reviewed and edited the manuscript. L.U. carried out the visualization. E.H.-H. supervised the study. L.U. and E.H.-H. conducted the project administration. E.H.-H., D.M.-I., and J.P. carried out the funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Support from the Deutscher Akademischer Austauschdienst (DAAD; funding program number: 57381412; funding program: Research Grants–Doctoral Programmes in Germany 2018/2019) and the Graduate School BuildMoNa (L.U.) is acknowledged. Support from the Development of the Republic of Serbia (451-03-68/2022-14/200007) is also gratefully acknowledged (M.M., D.M.-I., and S.M.). We thank the German Research Foundation (DFG; Development of carborane-based COX-2 inhibitors for theranostic approaches; HE 1376/54-1 PI 304/7-1 (E.H.-H., M.L., and J.P.) for financial support.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Kemisetti D. P.; Manida S.; Aukunuru J.; Chinnala K. M.; Rapaka N. K. Synthesis of prodrugs of mefenamic acid and their in vivo evaluation. Int. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2014, 6, 437–442. [Google Scholar]

- Nija B.; Rasheed A.; Kottaimuthu A. Development, Characterization, and Pharmacological Investigation of Sesamol and Thymol Conjugates of Mefenamic Acid. J. Evol. Med. Dent. Sci. 2020, 9, 3909–3916. [Google Scholar]

- Jarrar Q. B.; Hakim M. N.; Cheema M. S.; Zakaria Z. A.. In vitro characterization and in vivo performance of mefenamic acid-sodium diethyldithiocarbamate based liposomes. Braz. J. Pharm. Sci. 2019, 55, 10.1590/s2175-97902019000117870. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shirvani M. A.; Motahari-Tabari N.; Alipour A. The effect of mefenamic acid and ginger on pain relief in primary dysmenorrhea: a randomized clinical trial. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2015, 291, 1277–1281. 10.1007/s00404-014-3548-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baum C.; Kennedy D. L.; Forbes M. B. Utilization of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Arthritis Rheum. 1985, 28, 686–692. 10.1002/art.1780280613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husain A.; Ahuja P.; Ahmad A.; Khan S. A. Synthesis, Biological Evaluation and Pharmacokinetic Studies of Mefenamic Acid - N-Hydroxymethylsuccinimide Ester Prodrug as Safer NSAID. Med. Chem. 2016, 12, 585–591. 10.2174/1573406412666160107113548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marnett L. J. The COXIB experience: a look in the rearview mirror. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2009, 49, 265–290. 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.011008.145638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaux C.; Charlier C. Structural approach for COX-2 inhibition. Mini Rev. Med. Chem. 2004, 4, 603–615. 10.2174/1389557043403756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orlando B. J.; Malkowski M. G. Substrate-selective Inhibition of Cyclooxygeanse-2 by Fenamic Acid Derivatives Is Dependent on Peroxide Tone. J. Biol. Chem. 2016, 291, 15069–15081. 10.1074/jbc.M116.725713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mengle-Gaw L. J.; Schwartz B. D. Cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors: promise or peril?. Mediators Inflammation 2002, 11, 864195. 10.1080/09629350290000041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derle D. V.; Gujar K. N.; Sagar B. S. Adverse effects associated with the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: An overview. Indian J. Pharm. Sci. 2006, 68, 409. 10.4103/0250-474X.27809. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Somchit M. N.; Sanat F.; Hui G. E.; Wahab S. I.; Ahmad Z. Mefenamic Acid induced nephrotoxicity: an animal model. Adv. Pharm. Bull. 2014, 4, 401–404. 10.5681/apb.2014.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stockmann P.; Gozzi M.; Kuhnert R.; Sárosi M. B.; Hey-Hawkins E. New keys for old locks: carborane-containing drugs as platforms for mechanism-based therapies. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2019, 48, 3497–3512. 10.1039/C9CS00197B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celecoxib still on the market: but for whose benefit? Prescrire Int. 2005, 14, 177–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thun M. J.; Henley S. J.; Patrono C. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs as anticancer agents: mechanistic, pharmacologic, and clinical issues. J. Natl. Cancer. Inst. 2002, 94, 252–266. 10.1093/jnci/94.4.252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rüegg C.; Zaric J.; Stupp R. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and COX-2 inhibitors as anti-cancer therapeutics: hypes, hopes and reality. Ann. Med. 2003, 35, 476–487. 10.1080/07853890310017053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathew B.; Hobrath J. V.; Lu W.; Li Y.; Reynolds R. C. Synthesis and preliminary assessment of the anticancer and Wnt/β-catenin inhibitory activity of small amide libraries of fenamates and profens. Med. Chem. Res. 2017, 26, 3038–3045. 10.1007/s00044-017-2001-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo D. H.; Han I.-S.; Jung G. Mefenamic acid-induced apoptosis in human liver cancer cell-lines through caspase-3 pathway. Life Sci. 2004, 75, 2439–2449. 10.1016/j.lfs.2004.04.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovala-Demertzi D.; Hadjipavlou-Litina D.; Staninska M.; Primikiri A.; Kotoglou C.; Demertzis M. A. Anti-oxidant, in vitro, in vivo anti-inflammatory activity and antiproliferative activity of mefenamic acid and its metal complexes with manganese(II), cobalt(II), nickel(II), copper(II) and zinc(II). J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 2009, 24, 742–752. 10.1080/14756360802361589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valliant J. F.; Guenther K. J.; King A. S.; Morel P.; Schaffer P.; Sogbein O. O.; Stephenson K. A. The medicinal chemistry of carboranes. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2002, 232, 173–230. 10.1016/S0010-8545(02)00087-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Scholz M.; Hey-Hawkins E. Carbaboranes as pharmacophores: properties, synthesis, and application strategies. Chem. Rev. 2011, 111, 7035–7062. 10.1021/cr200038x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saretz S.; Basset G.; Useini L.; Laube M.; Pietzsch J.; Drača D.; Maksimović-Ivanić D.; Trambauer J.; Steiner H.; Hey-Hawkins E.. Modulation of γ-Secretase Activity by a Carborane-Based Flurbiprofen Analogue. Molecules 2021, 26, 10.3390/molecules26102843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buzharevski A.; Paskas S.; Sárosi M.-B.; Laube M.; Lönnecke P.; Neumann W.; Mijatovic S.; Maksimovic-Ivanic D.; Pietzsch J.; Hey-Hawkins E. Carboranyl Analogues of Celecoxib with Potent Cytostatic Activity against Human Melanoma and Colon Cancer Cell Lines. ChemMedChem 2019, 14, 315–321. 10.1002/cmdc.201800685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buzharevski A.; Paskas S.; Laube M.; Lönnecke P.; Neumann W.; Murganic B.; Mijatovic S.; Maksimovic-Ivanic D.; Pietzsch J.; Hey-Hawkins E. Carboranyl Analogues of Ketoprofen with Cytostatic Activity against Human Melanoma and Colon Cancer Cell Lines. ACS Omega 2019, 4, 8824–8833. 10.1021/acsomega.9b00412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholz M.; Bensdorf K.; Gust R.; Hey-Hawkins E. Asborin: the carbaborane analogue of aspirin. ChemMedChem 2009, 4, 746–748. 10.1002/cmdc.200900072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholz M.; Blobaum A. L.; Marnett L. J.; Hey-Hawkins E. Synthesis and evaluation of carbaborane derivatives of indomethacin as cyclooxygenase inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2011, 19, 3242–3248. 10.1016/j.bmc.2011.03.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barth R. F.; Mi P.; Yang W. Boron delivery agents for neutron capture therapy of cancer. Cancer Commun. 2018, 38, 35. 10.1186/s40880-018-0299-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimes R. N.Carboranes, 3rd ed., Academic Press Inc: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; ISBN 9780128018941. [Google Scholar]

- Hey-Hawkins E.; Teixidor C. V.. Boron-Based Compounds: Potential and Emerging Applications in Medicine; 1st ed., John Wiley & Sons Ltd: Oxford, United Kingdom, 2018.; ISBN 9781119275589. [Google Scholar]

- Neumann W.; Xu S.; Sárosi M. B.; Scholz M. S.; Crews B. C.; Ghebreselasie K.; Banerjee S.; Marnett L. J.; Hey-Hawkins E. nido-Dicarbaborate Induces Potent and Selective Inhibition of Cyclooxygenase-2. ChemMedChem 2016, 11, 175–178. 10.1002/cmdc.201500199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laube M.; Neumann W.; Scholz M.; Lönnecke P.; Crews B.; Marnett L. J.; Pietzsch J.; Kniess T.; Hey-Hawkins E. 2-Carbaborane-3-phenyl-1H-indoles--synthesis via McMurry reaction and cyclooxygenase (COX) inhibition activity. ChemMedChem 2013, 8, 329–335. 10.1002/cmdc.201200455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gozzi M.; Schwarze B.; Hey-Hawkins E. Half- and mixed-sandwich metallacarboranes for potential applications in medicine. Pure Appl. Chem. 2019, 91, 563–573. 10.1515/pac-2018-0806. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Himmelspach A.; Finze M. Dicarba- closo -dodecaboranes with One and Two Ethynyl Groups Bonded to Boron. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2010, 2010, 2012–2024. 10.1002/ejic.201000064. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Štíbr B.; Tok O. L.; Holub J. Quantitative Assessment of Substitution NMR Effects in the Model Series of o-Carborane Derivatives: α-Shift Correlation Method. Inorg. Chem. 2017, 56, 8334–8340. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.7b01023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dziedzic R. M.; Saleh L. M. A.; Axtell J. C.; Martin J. L.; Stevens S. L.; Royappa A. T.; Rheingold A. L.; Spokoyny A. M. B-N, B-O, and B-CN Bond Formation via Palladium-Catalyzed Cross-Coupling of B-Bromo-Carboranes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 9081–9084. 10.1021/jacs.6b05505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beletskaya I. P.; Bregadze V. I.; Kabytaev K. Z.; Zhigareva G. G.; Petrovskii P. V.; Glukhov I. V.; Starikova Z. A. Palladium-Catalyzed Amination of 2-Iodo-para-carborane. Organometallics 2007, 26, 2340–2347. 10.1021/om0611756. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sevryugina Y.; Julius R. L.; Hawthorne M. F. Novel approach to aminocarboranes by mild amidation of selected iodo-carboranes. Inorg. Chem. 2010, 49, 10627–10634. 10.1021/ic101620h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukhin S. N.; Kabytaev K. Z.; Zhigareva G. G.; Glukhov I. V.; Starikova Z. A.; Bregadze V. I.; Beletskaya I. P. Catalytic Amidation of 9-Iodo- m -carborane and 2-Iodo- p -carborane at a Boron Atom. Organometallics 2008, 27, 5937–5942. 10.1021/om800635d. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cryer B.; Feldman M. Cyclooxygenase-1 and Cyclooxygenase-2 Selectivity of Widely Used Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs. Am. J. Med. 1998, 104, 413–421. 10.1016/S0002-9343(98)00091-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osafo N.; Agyare C.; Obiri D. D.; Antwi A. O.. Mechanism of Action of Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs. In Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs; Al-kaf A. G. A., Ed.; InTech, 2017.

- Gurpinar E.; Grizzle W. E.; Piazza G. A. COX-Independent Mechanisms of Cancer Chemoprevention by Anti-Inflammatory Drugs. Front. Oncol. 2013, 3, 181. 10.3389/fonc.2013.00181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Towers C. G.; Wodetzki D.; Thorburn A. Autophagy and cancer: Modulation of cell death pathways and cancer cell adaptations. J. Cell. Biol. 2020, 219, e201909033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mijatović S.; Savić-Radojević A.; Plješa-Ercegovac M.; Simić T.; Nicoletti F.; Maksimović-Ivanić D. The Double-Faced Role of Nitric Oxide and Reactive Oxygen Species in Solid Tumors. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 374. 10.3390/antiox9050374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aggarwal V.; Tuli H. S.; Varol A.; Thakral F.; Yerer M. B.; Sak K.; Varol M.; Jain A.; Khan M. A.; Sethi G. Role of Reactive Oxygen Species in Cancer Progression: Molecular Mechanisms and Recent Advancements. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 735. 10.3390/biom9110735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris R. K.; Becker E. D.; Cabral De Menezes S. M.; Goodfellow R.; Granger P. NMR nomenclature: Nuclear spin properties and conventions for chemical shifts (IUPAC recommendations 2001). Concepts Magn. Reson. 2002, 14, 326–346. 10.1002/cmr.10035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isotope Distrribution Calculator and Mass Spec Plotter. https://www.sisweb.com/mstools/isotope.htm.

- Rigaku Oxford Diffraction. CrysAlisPro Software system; Rigaku Corporation, Oxford, UK.

- SCALE3 ABSPACK:Empirical absorption correction using spherical harmonics.

- SHELXT: G. M. Sheldrick, Acta Cryst. A71 (2015) 3–8]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- SHELXL: G. M. Sheldrick, Acta Cryst. C71 (2015) 3–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Mijatovic S.; Maksimovic-Ivanic D.; Radovic J.; Popadic D.; Momcilovic M.; Harhaji L.; Miljkovic D.; Trajkovic V. Aloe-emodin prevents cytokine-induced tumor cell death: the inhibition of auto-toxic nitric oxide release as a potential mechanism. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2004, 61, 1805–1815. 10.1007/s00018-004-4089-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drača D.; Mijatović S.; Krajnović T.; Pristov J. B.; Đukić T.; Kaluđerović G. N.; Wessjohann L. A.; Maksimović-Ivanić D. The synthetic tubulysin derivative, tubugi-1, improves the innate immune response by macrophage polarization in addition to its direct cytotoxic effects in a murine melanoma model. Exp. Cell Res. 2019, 380, 159–170. 10.1016/j.yexcr.2019.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.