Abstract

An effective method for designing new heterocyclic compounds of 6,7-dihydro-5H-cyclopenta[b]pyridine-3-carbonitrile derivatives (CAPDs) was presented through cyclocondensation reaction between 2,5-diarylidenecyclopentanone derivatives and propanedinitrile, and the cyclocondensation reaction succeeded using a sodium alkoxide solution (sodium ethoxide or sodium methoxide) as the reagent and the catalyst. The synthesized CAPD derivatives were employed as novel inhibitors for carbon steel (CS) corrosion in a molar H2SO4 medium. The corrosion protection proficiency was investigated by electrochemical measurements (open circuit potential vs time (EOCP vs t), potentiodynamic polarization plots (PDP), and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS)) and surface morphology (scanning electron microscopy (SEM)) examinations. The results show that the CAPD derivatives exhibit mixed type inhibitors and a superior inhibition efficiency of 97.7% in the presence of 1.0 mM CAPD-1. The adsorption of CAPD derivatives on the CS interface follows the Langmuir isotherm model, including physisorption and chemisorption. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) exploration confirmed the adsorption of the CAPD derivatives on the CS substrate. Monte Carlo (MC) simulations and DFT calculations revealed that the efficacy of the CAPD molecules correlates well with their structures, and this protection was attributed to their adsorption on the CS surface.

1. Introduction

Carbon steel (CS) is a widespread engineering and structural material in manufacturing applications1,2 because of its outstanding mechanical property and low cost. However, CS is vulnerable to corrosion through industrial operations, for example, industrial cleaning, acid pickling, acidizing, etc.3−5 The industrial cleaning performed by H2SO4 is utilized more often than HCl and HNO3. It could be ascribed to its cheap price; it does not cause pitting corrosion and its stability at higher temperature. Moreover, the addition of an inhibitor is a successful method utilized in the protection of metal from corrosion in acidic environments during industrial processes. At present, the most applicable corrosion inhibitors utilized in acidic environments relate to organic compounds, which include some species having a heteroatoms (nitrogen, sulfur, and oxygen) or conjugated-bonds.6−9 Its corrosion protection efficiency lies with the adsorption and surface-covering capabilities, which are associated with the electron density, the molecular structure of various efficient groups, the charge of the metal surface, the medium temperature, etc.10,11 The heteroatoms and conjugated bonds might offer the electron lone pair and form a coordinate bond with vacant d-orbital on the metal interface (i.e., chemisorption).12−14 Furthermore, the protective layer is formed by electrostatic attraction between the charged metal surface and the protonated inhibitor compound via physical adsorption.15,16 The adsorption films can successfully retard the attack of corrosive medium.

Heterocyclic components containing nitrogen are seemingly the essential component in the structure of numerous novel designs and the synthesis of organic components and they naturally exist as alkaloid compounds, which are vital for use as medicinal drug compounds.17 The pyridine moiety is more attractive because of its widespread chemical applications.18,19 For example, 3-cyanopyridine derivatives have many uses, such as IKKb inhibitors and A2A adenosine receptor antagonists.20 Recently, several protocols have been reported to produce 3-cyanopyridine derivatives. Even so, most of these methodologies are subject to restrictions of the highest temperatures, the time of the reaction is very high, and the yield is very low.21 Nowadays, to find an environmentally friendly catalyst that works in normal conditions is still a significant challenge for producing 3-cyanopyridine derivatives. The heterocyclic molecules used as corrosion inhibitors are revealed to have the most efficient corrosion inhibition. These molecules contain heteroatoms like nitrogen, sulfur, oxygen, benzene rings, π-bonds, and various functional groups that give noteworthy coverage of the metal surface and permit corrosion inhibition.22 Concerning eco-friendly safety concerns, numerous heterocyclic compounds that are considered to be natural/green, such as pharmaceutical molecules, biomolecules, and natural extracts, have been established as inhibitors for metal corrosion.23

In this work, the CAPD derivatives including 2-ethoxy-4-(pyridin-2-yl)-7-(pyridin-2-ylmethylidene)-6,7-dihydro-5H-cyclopenta[b]pyridine-3-carbonitrile (CAPD-1), 2-methoxy-4-(pyridin-2-yl)-7-(pyridin-2-ylmethylidene)-6,7-dihydro-5H-cyclopenta[b]pyridine-3-carbonitrile (CAPD-2), 2-methoxy-4-(pyridin-4-yl)-7-(pyridin-4-ylmethylidene)-6,7-dihydro-5H-cyclopenta[b]pyridine-3-carbonitrile (CAPD-3), and 7-(2-methoxybenzylidene)-4-(2-methoxyphenyl)-2-ethoxy-6,7-dihydro-5H-cyclopenta[b]pyridine-3-carbonitrile (CAPD-4) were synthesized and employed as efficient corrosion inhibitors for CS in a molar H2SO4 medium. The electrochemical investigations (EOCP vs t, PDP, and EIS) were utilized to study the corrosion protection performance. SEM was executed to explore the microstructure and the steel surface in blank and inhibited systems. Additionally, the mechanism and the type of adsorption process were considered. DFT calculations and MC simulations demonstrated that the proficiency of the CAPD molecules relate to their structures, and this protection was ascribed to their adsorption on the CS surface.

2. Experimental Details

2.1. Materials and Apparatus

All commercially obtainable reagents were obtained from Aldrich, Merck, and Fluka and were utilized without further refinement. All chemical reactions were observed by thin-layer chromatography (TLC) using precoated plates of G/UV-254 silica-gel (Merck 60F254) of 0.250 mm thickness with UV light (254.0 nm/365.0 nm) for visualization. Melting points were determined with a melting point device (Kofler). FTIR were measured with a Pt-ATR spectrometer (FT-IR-ALPHBROKER) by the attenuated total reflection (ATR) technique. 1H and 13C NMR spectra for all the prepared molecules were measured in d6-DMSO on a Bruker AG spectrometer Bio Spin at 400.0 and 100.0 MHz, respectively. Elemental investigates were attained on a CHN-analyzer (PerkinElmer).

2.2. General Process for Preparation of Compounds CAPD-1–CAPD-4

A mixture of 2,5-dibenzylidenecyclopentanone derivatives (0.02 mol) (2,5-bis(2-pyridinylmethylene)cyclopentanone (0.02 mol, 5.24 g), 2,5-bis(2-pyridinylmethylen)cyclopentanone (0.02 mol, 5.24 g), 2,5-bis(2-methoxybenzyliden)cyclopentanone (0.02 mol, 6.40 g), sodium alkoxide (0.02 mol) (sodium ethoxide 1.36 g or sodium methoxide 1.08 g), and propanedinitrile (0.02 mol, 1.32 g) (in the case that uses sodium ethoxide, the solvent of the reaction is ethanol; in the case using sodium methoxide, the solvent of the reaction is methanol) were refluxed for 1 h at 80 °C. The reaction mixture was allowed to cool at room temperature and diluted with 150 mL of dist. H2O. The crude product was then filtered off and washed three times with dist. H2O, and the solvent of crystallization was ethanol to produce a high purity product of cyclopentanpyridine derivatives.

2.3. Characterization Data of CAPD-1–CAPD-4

2-Ethoxy-4-(pyridin-2-yl)-7-(pyridin-2-ylmethylidene)-6,7-dihydro-5H-cyclopenta[b]pyridine-3-carbonitrile (CAPD-1)

Yield 77%; gray crystal; melting point:

149–151 °C. IR (ATR) νmax 3067, 3032

(C–H arom.), 2977, 2935 (C–H aliph.), 2204 (C≡N),

1599 (C=N) cm–1. 1H NMR (400 MHz,

DMSO-d6) δ 1.43 (t,, J = 7.0 Hz, 3H, CH3-CH2), 2.87 (t, J = 5.8 Hz, 2H, CH2-CH2 Cyclic), 3.09 (t, J = 4.1 Hz, 2H, CH2–CH2 Cyclic), 4.61

(q, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H, CH2-CH3), 7.31–7.59 (m, 9H, (8CHarom. + CH=)). 13C NMR (DMSO-d6, 100 MHz) δ 14.8, 27.2, 28.9, 63.4, 93.7, 116.0, 125.8, 128.3,

128.7, 129.2, 129.4, 129.6, 130.0, 131.0, 135.2, 136.9, 141.4, 153.0,

161.9, 164.9. Anal. Calcd for C22H18N4O (354.40): C, 74.56; H, 5.12; N, 15.81. Found: C, 74.42; H, 5.01;

N, 15.67 (Figure S1).

2-Methoxy-4-(pyridin-2-yl)-7-(pyridin-2-ylmethylidene)-6,7-dihydro-5H-cyclopenta[b]pyridine-3-carbonitrile (CAPD-2)

Yield 75%; white crystal; m.p.: 171–173

°C. IR (ATR) νmax 3058, 3021 (C–H arom.),

2994, 2951 (C–H aliph.), 2219 (C≡N), 1602 (C=N)

cm–1. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 2.89 (t, J = 6.0 Hz, 2H, CH2–CH2Cycllic), 3.10 (t, J = 6.0 Hz, 2H, CH2-CH2Cycllic), 4.13 (s, 3H, OMe), 7.43–7.60 (m, 9H, (8CHarom. + CH=)). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 27.3, 28.9, 54.8, 93.7, 116.0, 125.9, 128.3, 128.7,

129.2, 129.5, 129.6, 130.0, 131.0, 135.2, 136.9, 141.3, 153.0, 161.9,

165.3. Anal. Calcd for C21H16N4O

(340.40): C, 74.10; H, 4.74; N, 16.46. Found: C, 73.97; H, 4.61; N,

16.39 (Figure S2).

2-Methoxy-4-(pyridin-4-yl)-7-(pyridin-4-ylmethylidene)-6,7-dihydro-5H-cyclopenta[b]pyridine-3-carbonitrile (CAPD-3)

Yield 82%; white crystal; m.p.: 180–181

°C. IR (ATR) νmax 3062, 3001 (C–H arom.),

2989, 2921 (C–H aliph.), 2200 (C≡N), 1602 (C=N)

cm–1. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 2.75–2.92 (m, 4H, CH2-CH2Cycllic), 4.02 (s, 3H, OMe), 7.51–7.63

(m, 9H, (8CHarom. + CH=)). 13C NMR (100 MHz,

DMSO-d6) δ 27.1, 28.9, 54.9, 93.8,

115.9, 124.6, 128.6, 129.2, 129.4, 130.8, 131.3, 132.8, 133.8, 135.0,

135.7, 142.0, 142.1, 161.8, 165.2. Anal. Calcd for C21H16N4O (340.40): C, 74.10; H, 4.74; N, 16.46. Found:

C, 73.95; H, 4.68; N, 16.29 (Figure S3).

7-(2-Methoxybenzylidene)-4-(2-methoxyphenyl)-2-ethoxy-6,7-dihydro-5H-cyclopenta[b]pyridine-3-carbonitrile (CAPD-4)

Yield 75%; yellow crystal; m.p.: 160–161 °C. IR (ATR) νmax 3058, 3021 (C–H arom.), 2981, 2966 (C–H aliph.), 2214 (C≡N), 1605 (C=N) cm–1. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 1.43 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 3H, CH3-CH2–O), 2.89 (t, J = 5.9 Hz, 2H, CH2CH2cyclic), 3.07 (t, J = 4.7 Hz, 2H, CH2CH2cyclic), 3.81, 3.85 (s, 6H, 2OMe), 4.59 (q, J = 6.8 Hz, 2H, O-CH2-CH3), 7.00–7.02 (d, 2H, 2CHarom), 7.02–7.12 (d, 2H, 2CHarom), 7.43 (s, 1H, CH=), 7.49–7.51 (d, 2H, 2CHarom), 7.53–7.55 (d, 2H, 2CHarom). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 14.8, 27.3, 28.8, 55.7, 55.8, 63.2, 93.0, 114.7, 114.8, 116.4, 125.5, 127.3, 129.7, 130.5, 130.6, 131.2, 138.9, 152.5, 159.5, 160.7, 162.2, 165.1. Anal. Calcd for C26H24N2O3 (412.48): C, 75.71; H, 5.86; N, 6.79. Found: C, 75.77; H, 5.79; N, 6.70 (Figure S4).

2.5. Corrosion Protection Experiments

The corrosion experiments were accomplished by a Gamry galvanostat/potentiostat/ZRA electrochemical-workstation (Reference 600+) at a temperature range of 25–55 °C in 1.0 M H2SO4 as an aggressive solution. A Pt-sheet and silver/silver chloride (Ag/AgCl/KCl(sat)) were used as counter and reference electrodes, respectively. The working electrode is a CS alloy specimen (with surface area ∼0.60 cm2). The variants in the open circuit potential (EOCP) of various inhibitor doses were checked for 50 min of immersion. PDP investigations of the blank and inhibited surfaces were estimated after 50 min of immersing in the acidic solution, within the potential series from ±250.0 mV vs EOCP at a sweep rate of 0.2 mV s–1. The impedance (EIS) study was achieved employing within the frequency range from 0.10 Hz to 100.0 kHz sine wave signals of amplitude 10 mV. The EIS plots were fitted by Gamry Framework software EIS300 with an appropriate equivalent circuit. Each corrosion experiment was reiterated three times to validate the results’ reproducibility.

2.6. Corrosion Protection Capacity (PC) Calculation

PCT (%) was computed from the potentiodynamic polarization method by the following equation:24

| 1 |

where jcor0 and jcor are corrosion current densities (jcor) in the blank and occurrence of different inhibitor concentrations, respectively. PCE was also calculated from the impedance experiments by the following equation:25

| 2 |

where RP0 and RP are the polarization resistances (RP) in the absence and existence of diverse additive concentrations, respectively. The part of surface covered (θ) is correlated to the PC as26

| 3 |

2.7. Surface Analysis before and after Corrosion Inspection

The surface morphology of the uninhibited and inhibited systems after 48 h immersed in molar sulfuric acid medium at 298 K was inspected by a SEM apparatus (JSM-6610 LV model) at 20 kV as the accelerating voltage.

2.8. Computational Details

The energy minimization of the protonated form of the investigated cycloalkanapyridine derivative (CAPD) molecules in aqueous media was researched employing DFT calculations with the B3LYP-functional and DNP 4.4 basis set executed in Materials Studio V. 7.0 program in the Dmol3 module.27 The results obtained from DFT calculation including the highest occupied molecular orbital (EHOMO), the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (ELUMO), the hardness (η), the energy gap (ΔE), the electrophilicity index (ω), the electronegativity (χ), the global softness (σ), the vertical ionization potential (IP), the electron affinity (EA), the number of electrons transferred (ΔN), ΔEback-donation, and the dipole moment (μ) were investigated and computed as follows:28,29

| 4 |

| 5 |

| 6 |

| 7 |

| 8 |

| 9 |

| 10 |

where, φ denotes Fe (110) function work, χinh signifies the inhibitor electronegativity, ηinh and ηFe are the chemical hardness of inhibitor and Fe (0 eV), respectively.

For MC simulations, the proper adsorption arrangements of the protonated form of the CAPD molecules on the iron (110) interface were revealed by operating the locator module adsorption in the Materials Studio V. 7.0 program.30 First, the adsorbate species had been optimized running the COMPASS force field.31 Afterward, in a simulation box (37.24 Å × 37.24 Å × 59.81 Å), adsorption of the examined inhibitors, SO42– ions, H2O molecules, and hydronium ions with the Fe(110) surface was achieved.32

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Synthesis

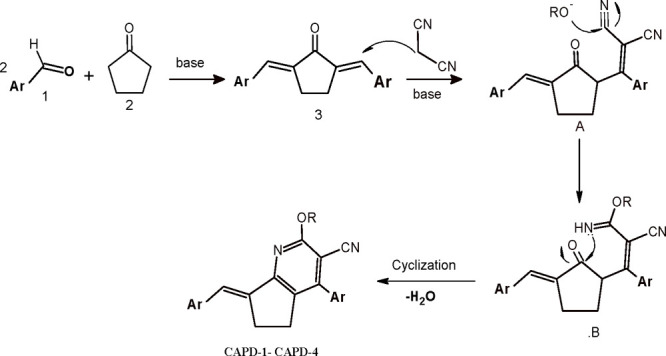

In this work, we are introducing a novel method for synthesizing some new components of highly functionalized 2-alkoxy-4-(aryl)-7-(aryl-2-ylmethylidene)-6,7-dihydro-5H-cyclopenta[b]pyridine-3-carbonitrile derivatives (CAPD-1–CAPD-4) through the facile method via cyclocondensation reaction between 2,5-diarylidenecyclopentanone and propanedinitrile. The cyclocondensation reaction successfully employed sodium alkoxide solution as the reagent and the catalyst (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1. Design of 2-Alkoxy-4-(aryl)-7-(aryl-2-ylmethylidene)-6,7-dihydro-5H-cyclopenta[b]pyridine-3-carbonitriles (CAPD-1–CAPD-4).

This methodology compromises a flexible method in tuning the molecular complexity and diversity. The reflux time to proceed to completion was ∼2 h and highly pure compounds were acquired in outstanding yields, without employing any chromatographic technique, just simply filtration and recrystallization. The proposed mechanism for the preparation of 2-alkoxy-4-(aryl)-7-(aryl-2-ylmethylidene)-6,7-dihydro-5H-cyclopenta[b]pyridine-3-carbonitriles (CAPD-1–CAPD-4) were undertaken by preparation of diarylidine cycloalpentanone derivatives 3 by Knoevenagel condensation between cyclopentanone 2 and aromatic aldehydes 1 (2 mol) (Scheme 2). The reaction progressed via Michael addition of propanedinitrile to form α, β-unsaturated cycloketones to produce adduct A, which undertakes a nucleophilic attack through alkoxide anion RO–, giving intermediate B. In this moment, intermediate B easily undergoes cyclization and dehydration to produce the wanted compounds, which was postulated previously.17

Scheme 2. Suggested Mechanism for Synthesizing of 2-Alkoxy-4-(aryl)-7-(aryl-2-ylmethylidene)-6,7-dihydro-5H-cyclopenta[b]pyridine-3-carbonitriles (CAPD-1–CAPD-4).

The structures of the designed compounds CAPD-1–CAPD-4 were approved on the basis of their IR spectrum, NMR spectrum, and elemental analysis. For example, the IR spectrum of 2-ethoxy-4-(pyridin-2-yl)-7-(pyridin-2-ylmethylidene)-6,7-dihydro-5H-cyclopenta[b]pyridine-3-carbonitrile (CAPD-1) exhibited an absorption band at 2204 cm–1 due to the C≡N group. Its 1H NMR spectrum exhibited the occurrence of triplet signals at 1.43 ppm, which represents the methyl of OEt and two triplet signals at d 2.87 and 3.09 ppm discriminatory of cyclic CH2–CH2, It also displayed a quartet signal at 4.61 ppm for OEt group and multiplet signals at 7.31–7.59 ppm, indicating aromatic protons and a CH= vinyl group. The 13C NMR spectrum of 2-ethoxy-4-(pyridin-2-yl)-7-(pyridin-2-ylmethylidene)-6,7-dihydro-5H-cyclopenta[b]pyridine-3-carbonitrile (CAPD-1) displayed 15 signals at 116.00, 125.77, 128.31, 128.74, 129.19, 129.43, 129.64, 129.97, 131.04, 135.18, 136.87, 141.41, 152.97, 161.91, and 164.93, which are characteristic the carbons of aromatic and CH= vinyllic groups; 93.73, which indicates a C≡N group; 63.38, which belongs to the methylene (CH2) group of the ethoxy group; and two CH2 cyclic groups are shown at 27.22 and 28.90 ppm, with the final the methyl of the ethoxy group appearing at 14.79 ppm.

3.2. Corrosion Mitigation Performance by the Cycloalkanapyridine Derivatives

3.2.1. Eocp vs Time Examinations

The variation in Eocp vs time plots for CS alloy in molar sulfuric medium without and with diverse concentrations of CAPD-1 (A) and with 1 × 10–3 M of different cycloalkanapyridine derivatives at 25 °C is presented in Figure 1. As previously stated, this was completed to confirm that the investigated corrosion inhibitor systems reach quasi-equilibrium prior EIS experiments.33 From the data in Figure 1, it is observable that the 2000 s to 35 min of Eocp was definite and adequate quasi-equilibrium was attained for entire corrosion systems. Moreover, the data expose that the Eocp in the presence of cycloalkanapyridine inhibitors was honorable at the beginning of the experimentations compared to that of the blank medium, whereas for the blank H2SO4 medium, the Eocp increased over time up to 2000 s, and then the Eocp for the solution containing inhibitors was still constant from 2000 to 3000 s. This is reveals of the impact of cycloalkanapyridine derivative adsorption on the steel alloy deterioration route.34 Furthermore, Figure 1 shows that the modification in the Eocp values of the acid solution containing additives compared to the blank medium (free inhibitor) is smaller than 0.085 V vs OCP, indicating that the studied cycloalkanapyridine derivatives classifying as inhibitors of anodic/cathodic-type (mixed-type inhibitors).35 For example, at 3000 s, the value of Eocp for the uninhibited system is −0.432 V, and in the presence of 1.0 mM of CAPD-1, CAPD-2, CAPD-3, and CAPD-4, the values are −0.427, −0.425, 0.426, and −0.431 V, respectively; the largest change is 0.007 V. According to these findings, cycloalkanapyridine derivatives are categorized as mixed-kind inhibitors and impede steel alloy deterioration in H2SO4 by reducing both the cathodic and anodic reactions.36

Figure 1.

Eocp vs time plots for CS alloy in molar sulfuric acid solution (A) without and with diverse concentrations of CAPD-1 and (B) with 1 × 10–3 M of different cycloalkanapyridine derivatives at 25 °C.

3.2.2. PDP Studies

PDP measurements were attained for the CS alloy in 1.0 M sulfuric acid without and with diverse concentrations of CAPD-1 (A) and with different cycloalkanapyridine derivatives at 25 °C and 1.0 × 10–3 M are depicted in Figure 2A, B. Comparable plots were acquired for the other additive compounds (CAPD-2, CAPD-3, and CAPD-4). For entirely the four cycloalkanapyridine derivatives experienced as corrosion protection additives, the cathodic and anodic branches shifted to smaller current density area in the occurrence of the inhibitors related to the uninhibited system. This indicates that the tested inhibitors diminish the jcor and consequently decrease the rate of corrosion. The Tafel diagrams correspondingly display some changes in the corrosion potential (Ecor) to more cathodic or anodic areas relative to the uninhibited solution. The shift direction is not unvarying, as it differs with additive dose. This proposes that the cycloalkanapyridine derivatives mutually influenced the cathodic and anodic deterioration reactions.

Figure 2.

PDP plots for CS alloy in molar sulfuric solution (A) without and with diverse concentrations of CAPD-1 and (B) with 1 × 10–3 M of different cycloalkanapyridine derivatives at 25 °C.

The corrosion restrictions for the corrosion process in the blank and inhibited medium containing various inhibitor doses were attained from the PDP diagrams via Tafel extrapolations to the Ecor. The acquired findings are recorded in Table 1. The detected modification in Ecor of the inhibited solution compared to the free-inhibitor containing system is usually less than 0.085 V for the four tested cycloalkanapyridine derivatives. This indicates that the tested cycloalkanapyridine derivatives may be categorized as mixed-kind inhibitors.37 Moreover, the modification in the Ecor appears to be insignificant, with a maximum change of approximately ±0.023 V (Table 1). This phenomenon proposes that the insertion of the inspected compounds to the corrosive solution only weakly disturbs (or does not disturb) the CS alloy interface.38 Such a minor modification in the Ecor has also been ascribed to the geometric hindering of the efficient locations on the metal interface by the additive species.39

Table 1. Polarization Parameters for CS Alloy in Molar Sulfuric Acid Solution without and with Diverse Concentrations of Cycloalkanapyridine Derivatives at 25 °C.

| inhibitor code | Ci (mol L–1) | jcor (μA cm–2) | –Ecor/V (Ag/AgCl) | βa (mV dec –1) | βc (mV dec –1) | θ | PCT (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| blank | 0.0 | 367.8 | 0.447 | 93.9 | 226.7 | ||

| CAPD-1 | 4.0 × 10–5 | 195.3 | 0.429 | 103.1 | 232.4 | 0.469 | 46.9 |

| 8.0 × 10–5 | 141.2 | 0.426 | 103.5 | 233.4 | 0.616 | 61.6 | |

| 2.0 × 10–4 | 79.8 | 0.438 | 105.8 | 230.8 | 0.783 | 78.3 | |

| 6.0 × 10–4 | 26.5 | 0.439 | 99.8 | 229.6 | 0.928 | 92.8 | |

| 1.0 × 10–3 | 8.4 | 0.442 | 96.8 | 230.1 | 0.977 | 97.7 | |

| CAPD-2 | 4.0 × 10–5 | 207.4 | 0.430 | 105.7 | 236.2 | 0.436 | 43.6 |

| 8.0 × 10–5 | 148.6 | 0.435 | 101.2 | 237.7 | 0.596 | 59.6 | |

| 2.0 × 10–4 | 86.4 | 0.415 | 105.6 | 232.5 | 0.765 | 76.5 | |

| 6.0 × 10–4 | 39.3 | 0.425 | 109. 9 | 242.8 | 0.893 | 89.3 | |

| 1.0 × 10–3 | 20.6 | 0.418 | 109.5 | 234.3 | 0.944 | 94.4 | |

| CAPD-3 | 4.0 × 10–5 | 211.5 | 0.451 | 108.8 | 229.6 | 0.425 | 42.5 |

| 8.0 × 10–5 | 155.5 | 0.446 | 102.6 | 234.9 | 0.577 | 57.7 | |

| 2.0 × 10–4 | 89.1 | 0.428 | 99.4 | 234.3 | 0.758 | 75.8 | |

| 6.0 × 10–4 | 45.6 | 0.437 | 106.8 | 229.6 | 0.876 | 87.6 | |

| 1.0 × 10–3 | 29.8 | 0.442 | 115.8 | 228.9 | 0.919 | 91.9 | |

| CAPD-4 | 4.0 × 10–5 | 219.2 | 0.433 | 103.7 | 229.8 | 0.404 | 40.4 |

| 8.0 × 10–5 | 158.5 | 0.421 | 104.1 | 232.5 | 0.569 | 56.9 | |

| 2.0 × 10–4 | 95.9 | 0.429 | 106.6 | 234.9 | 0.739 | 73.9 | |

| 6.0 × 10–4 | 57.3 | 0.449 | 98.2 | 230.7 | 0.844 | 84.4 | |

| 1.0 × 10–3 | 34.9 | 0.438 | 113.1 | 233.4 | 0.905 | 90.5 |

The Tafel slope values (anodic βa and cathodic βc) differ marginally with the additive dose, but are deprived of a modest certain design. Nevertheless, the anodic βa and cathodic βc values in the case of inhibitor containing solutions are usually greater than those of the uninhibited system. The difference in the anodic βa and cathodic βc values with alteration in the inhibitor dose likewise appears to be more obvious for anodic βa than cathodic βc. These interpretations indicate the construction of CAPD–iron complexes in the higher and lower oxidation states on the CS alloy interface.40 This is indicative of more protective performances of the cycloalkanapyridine derivatives on the anodic site than the cathodic one.

The jcor declines with an increase in [inhibitor dose], resulting in an increase in protection capability (PCT). The PCT of CAPD-1, CAPD-2, CAPD-3, and CAPD-4 increases from 46.9, 43.6, 42.5, and 40.4% at 0.04 mM up to 97.7, 94.4, 91.9, and 90.5% at 1.0 mM, respectively. The PCT of CAPD compounds increases incessantly as the inhibitor dose increases from 0.04 to 1.0 mM. The protection capacities PCT follow the order CAPD-1 > CAPD-2 > CAPD-3 > CAPD-4. The increase in PCT with amassed inhibitor dose might be ascribed to the increase in the adsorbed species number of the additive on the metal substrate. The molecule numbers that adsorb on the efficient places on the CS alloy rise with cumulative [inhibitor dose], resulting in an improvement in the part of the covered surface coverage, and accordingly, an increase in PCT.

3.2.3. EIS Studies

Intensely, the impedance method has been confirmed to be an efficient approach for evaluating the inhibitor performance.41,42 This is due to the additive layer on a steel interface changing the EIS responses of the metal.43 To determine the influence of cycloalkanapyridine derivatives on the deterioration performance of the CS alloy in molar H2SO4 solution at 298 K, we completed EIS experimentations. Nyquist and Bode and Bode phase modules for the CS alloy in molar H2SO4 solution without and with diverse concentrations of CAPD-1 and with a 1.0 × 10–3 M (optimum dose) concentration of different cycloalkanapyridine derivatives at 25 °C are presented in Figures 3 and 4. Overall, at small to middle frequencies, only a capacitive loop is detected for every dose, indicative of a charge-organized deterioration process.44 Nevertheless, by comparing the Nyquist graphs at 1 × 10–3 M and 6.0 × 10–4 M (higher doses) inhibited systems to others (Figure 3A), it is observed that the Nyquist diagrams did not dismiss at the ZR axis and designates a “degradation” process of EIS45 because of a slowdown in the process of charge transfer produced by the developing of the protecting layer on the steel interface.46 Solomon et al.47 stated a comparable observation for a 5.0 g of chitosan + 5.0 mM potassium iodide mixture that was used as inhibitor for St37-steel in a 15% H2SO4 solution. Zheng et al.48 described a comparable behavior for steel in a H2SO4 medium comprising 1-butyl-3-methyl-1 H-benzimidazolium iodide inhibitor.

Figure 3.

Nyquist plots for CS alloy in molar sulfuric acid solution (A) without and with different concentrations of CAPD-1 and (B) with 1 × 10–3 M of different cycloalkanapyridine derivatives at 25 °C.

Figure 4.

(A) Bode and (B) Bode phase modules for CS alloy in molar sulfuric acid solution without and with different concentrations of CAPD-1 at 25 °C.

To comprehend the physical procedures happening at the CS alloy/solution interface, the impedance findings of the uninhibited and inhibited systems were demonstrated by the equivalent circuit (EEC) presented in Figure 5C, whose collection was acquainted by the impedance singleness (Figure 5A, B). Correspondingly, the EEC in Figure 5D was utilized to model the impedance results attained for the inhibited system and its assortment was well-versed by the deterioration phenomenon in Figure 5B. The fittingness of the designated EECs is exemplified in the illustrative fitted diagrams given in Figure 5C, D. The lesser values of x2 (Table 2) show that the designated EECs were appropriate. The EECs consist of electrolyte resistance (Rsoln), polarization resistance (Rp), and a CPE (constant phase element). In addition, the EEC in Figure 5d comprises the element film resistance (Rf) in the circumstance of an inhibited system; CPE is utilized rather than a perfect capacitor attributable to the steel surface inhomogeneity49 as revealed by the semicircle insufficiency50 in Figure 5A. The frequency reliant on the EIS response of the whole EECs in Figure 5C, D could be designated by simple circuit exploration assumed in eqs 1 and 2, respectively. This permits the popularization of the Rp by eq 3 as follows:

| 11 |

| 12 |

| 13 |

The CPE impedance defined by the formula in eq 4

| 14 |

where j, Y0, and ω are an imaginary number, the CPE constant, and the angular frequency, respectively. n denotes the CPE exponent most frequently utilized as a heterogeneity indicator. The n values are recorded in Table 2.

Figure 5.

Descriptive fitted diagrams of CS alloy for (A) blank medium and (B) inhibited system and equivalent circuit used in modeling findings for (C) blank and (D) inhibited system.

Table 2. Impedance Parameters for CS Alloy in 1.0 M H2SO4 Solution without and with Diverse Concentrations of Cycloalkanapyridine Derivatives at 25 °C.

|

Qdl |

Qf |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| inhibitor code | Ci (mol L–1) | Rs (Ω cm2) | RP (Ω cm2) ± 5% SD | Cdl (μF cm–2) ± 5% SD | Y0 (μΩ–1 sn cm–2) | n ± 5% SD | Yf (μΩ–1 sn cm–2) | nf | χ2 (× 10–5) | θ | PCE (%) |

| blank | 0.0 | 0.33 | 27.21 | 957.5 | 75.6 | 0.733 | 4.68 | ||||

| CAPD-1 | 4.0 × 10–5 | 0.65 | 50.32 | 159.2 | 12.56 | 0.821 | 10.27 | 0.666 | 5.25 | 0.459 | 45.9 |

| 8.0 × 10–5 | 0.80 | 68.60 | 108.5 | 8.57 | 0.832 | 7.01 | 0.746 | 5.28 | 0.603 | 60.3 | |

| 2.0 × 10–4 | 0.78 | 130.56 | 88.5 | 6.71 | 0.914 | 5.49 | 0.762 | 5.33 | 0.791 | 79.1 | |

| 6.0 × 10–4 | 1.59 | 264.35 | 47.6 | 3.82 | 0.850 | 3.12 | 0.830 | 5.40 | 0.897 | 89.7 | |

| 1.0 × 10–3 | 2.28 | 671.61 | 25.7 | 1.45 | 0.903 | 1.18 | 0.772 | 5.61 | 0.959 | 95.9 | |

| CAPD-2 | 4.0 × 10–5 | 0.57 | 45.74 | 213.5 | 16.65 | 0.833 | 13.62 | 0.810 | 5.28 | 0.405 | 40.5 |

| 8.0 × 10–5 | 0.65 | 62.36 | 146.1 | 10.95 | 0.830 | 8.95 | 0.772 | 5.31 | 0.563 | 56.3 | |

| 2.0 × 10–4 | 0.64 | 118.69 | 119.2 | 9.54 | 0.841 | 7.80 | 0.745 | 5.33 | 0.771 | 77.1 | |

| 6.0 × 10–4 | 1.27 | 246.31 | 63.6 | 4.47 | 0.857 | 3.65 | 0.745 | 5.52 | 0.889 | 88.9 | |

| 1.0 × 10–3 | 1.19 | 590.53 | 33.9 | 3.21 | 0.905 | 2.626 | 0.799 | 5.56 | 0.953 | 95.3 | |

| CAPD-3 | 4.0 × 10–5 | 0.49 | 42.96 | 341.7 | 26.99 | 0.855 | 22.08 | 0.873 | 5.96 | 0.366 | 36.6 |

| 8.0 × 10–5 | 0.52 | 59.21 | 233.6 | 18.43 | 0.835 | 15.06 | 0.727 | 5.81 | 0.540 | 54.0 | |

| 2.0 × 10–4 | 0.73 | 107.89 | 190.7 | 15.52 | 0.855 | 12.69 | 0.790 | 5.56 | 0.747 | 74.7 | |

| 6.0 × 10–4 | 1.19 | 222.97 | 102.3 | 8.72 | 0.861 | 7.135 | 0.771 | 4.96 | 0.878 | 87.8 | |

| 1.0 × 10–3 | 1.47 | 525.31 | 53.8 | 4.26 | 0.894 | 3.48 | 0.783 | 5.16 | 0.948 | 94.8 | |

| CAPD-4 | 4.0 × 10–5 | 0.47 | 39.76 | 399.8 | 31.61 | 0.855 | 25.86 | 0.813 | 5.97 | 0.315 | 31.5 |

| 8.0 × 10–5 | 0.55 | 56.34 | 273.3 | 21.63 | 0.905 | 17.69 | 0.727 | 5.91 | 0.517 | 51.7 | |

| 2.0 × 10–4 | 0.65 | 100.98 | 223.2 | 17.76 | 0.901 | 14.53 | 0.822 | 5.65 | 0.731 | 73.1 | |

| 6.0 × 10–4 | 1.12 | 204.56 | 119.7 | 8.97 | 0.909 | 7.33 | 0.819 | 5.07 | 0.866 | 86.6 | |

| 1.0 × 10–3 | 1.38 | 411.84 | 63.3 | 5.12 | 0.896 | 4.185 | 0.824 | 5.74 | 0.933 | 93.3 | |

It was observed in Figures 3 and 4 that the impedance diameter and the Bode and phase angle modules increase in the occurrence of cycloalkanapyridine derivatives. An additional increase is also detected with cumulative inhibitor dose. This confirms the corrosion mitigation by the prepared cycloalkanapyridine derivatives inhibitors. The results in Table 2 reveals that the detected augmentation in Figure 3 in the occurrence of cycloalkanapyridine derivatives and with incremental inhibitor doses is due to an improvement of the polarization resistance of the metal, probably attributable to the additive adsorption on the electrode substrate. For example, in the blank H2SO4 solution, the Rp of the CS alloy is 27.21 Ω cm2 but improved to 50.32, 45.74, 42.96, and 39.76 Ω cm2 in the occurrence of 4.0 × 10–5 mol L–1 and this confirmed the inhibition efficiency of the CS alloy surface by 45.9, 40.5, 36.6, and 31.5% in the presence of CAPD-1, CAPD-2, CAPD-3, and CAPD-4. The Rp and ηI augmented progressively with a rise in inhibitor dose and reached a maximum of 671.61, 590.53, 525.31, and 411.84 Ω cm2 and 95.9, 95.3, 94.8, and 93.3%, respectively, at 1.0 × 10–3 mol L–1CAPD-1, CAPD-2, CAPD-3, and CAPD-4. It is reasonable to state that the assets and the film thickness of the adsorbed inhibitor enhanced with increased concentrations of CAPD-1, CAPD-2, CAPD-3, and CAPD-4 compounds. To validate the assertion of an enhanced adsorbed layer with increasing inhibitor dose, we inspected the values of the Yf and Y0. Commonly, the restrictions Yf and Y0 describe the features of a surface film of the CS alloy51 and the smaller the value, the superior the surface layer.52 As can be observed in Table 2, the value of Y0 for the uninhibited medium is 75.6 μΩ–1 sn cm–2, whereas that of the 4.0 × 10–5 mol L–1 inhibited medium is 12.56, 16.65, 26.99, and 31.61 μΩ–1 sn cm–2 in the presence of CAPD-1, CAPD-2, CAPD-3, and CAPD-4, respectively. These demonstrations that the layer designed on the CS alloy interface in H2SO4 solution containing 4.0 × 10–5 mol L–1CAPD-1, CAPD-2, CAPD-3, and CAPD-4 displayed superior characteristics compared to the alloy surface film designed in the blank corrosive medium. Moreover, the value Y0 reduced in the presence 1.0 × 10–3 mol L–1 inhibitor to 1.45, 3.21, 4.26, and 5.12 μ μΩ–1 sn cm–2, respectively, for CAPD-1, CAPD-2, CAPD-3, and CAPD-4 inhibited mediums settling the assertion of superior surface layer features in the existence of greater dose of CAPD-1, CAPD-2, CAPD-3, and CAPD-4 compounds.

The assertion of an increase in the adsorbed layer thickness with increasing concentration could be acceptable by allowing for variance in the double layer capacitance (Cdl) with inhibitor dose.53 Consequently, the Helmholtz model given in eq 5(54) is accepted to elucidate the relationship between thickness and Cdl. It is inferred from this model that a decline in the dielectric constant or an increase in the film thickness leads to a diminution in Cdl. The values of Cdl recorded in Table 2 were computed, which was suitable for the investigated systems. Meanwhile, diffusion routes were not disclosed or calculated. From Table 2, it is observed that the Cdl value gradually declined with cumulative inhibitor dose and reached a smallest value of 25.7, 33.9, 53.8, and 63.3 μF cm–2 at 1.0 mmol L–1CAPD-1, CAPD-2, CAPD-3, and CAPD-4, respectively. Similarly, the Rp and ηI show that it reasonable that the inhibitive action of the inhibitor with cumulative dose is due to an increase in the adsorbed layer thickness. Lastly, the close steadiness of the n value (i.e., 0.733–0.909) discloses a capacitive interface:55

| 15 |

where ε signifies the local dielectric constant, ε0 represents the air permittivity, A symbolizes the electrode surface area, and d represents the adsorbed film thickness.

3.3. Adsorption Considerations, Effect of Temperature, and Corrosion Mitigation Mechanism Analysis

Analysis of adsorption isotherm models allows for the clarification of the inspected cycloalkanapyridine derivative mitigation mechanism via its adsorptive behavior and strength.56 Numerous models of adsorption isotherms, for example, the Flory–Huggins, Frumkin, Temkin, Langmuir, and Freundlich models, were utilized to appropriate the PDP findings to comprehend how the molecules of the inhibitor are absorbed on the CS alloy interface. Remarkably, the monolayer adsorption of the Langmuir model was found to be the best-fit pattern (R2 > 0.999) for the prepared compounds, signifying that the investigated layers are monofilms, where the [CAPD]/θ is plotted vs the [CAPD] (cf. Figure 6) as per the following equation:57

| 16 |

where [CAPD], Kads, and θ are the CAPD concentration in mol/L, the adsorption constant, and the part of the covered surface, respectively.

Figure 6.

Plot of [CAPD]/θ vs [CAPD] for the corrosion of CS alloy in 1.0 M H2SO4 solution containing (A) CAPD-1, (B) CAPD-2, (C) CAPD-3, and (D) CAPD-4 at 298 K.

The calculated parameters are recorded in Table 3. The line regression slope is observed to be ∼1, which shows that the adsorption of CAPD compounds onto the CS alloy interface follows the Langmuir model. The order of the Kads values are CAPD-1 (1.88 × 104 L mol–1) > CAPD-2 (1.78 × 104 L mol–1) > CAPD-3 (1.69 × 104 L mol–1) > CAPD-4 (1.64 × 104 L mol–1), which agrees with the corrosion inhibition capacity of the CAPD compounds. Generally, the greater the Kads value, the superior the protection performance. The Kads value computed from the intercept of y-axes was utilized to determine the adsorption free energy (ΔGads0) by the next equation:58

| 17 |

Where the negative signal of the ΔGads0 approves that the adsorption route is certainly spontaneous. Furthermore, the value of (ΔGads) provides a strong symptom about the adsorption process nature. In this regard, it is usually decided in the previous works that ΔGads0 values = or <−20 kJ/mol are suggestive a physical adsorption nature whereas those = or >−40 kJ/mol designate its chemical adsorption route.59 The value of ΔGads (ΔGads0 = −37.22, −37.07, −36.93, and −36.84 kJ mol–1 for CAPD-1, CAPD-2, CAPD-3, and CAPD-4, respectively) attained in the present study shows that a relatively complex mixed adsorption (chemisorption and physisorption nature) is complicated and that is a predominantly chemisorption.60 This infers a main electrostatic attraction (physical adsorption) among the CAPD molecule and the CS alloy in addition to electron sharing or transfer (chemical adsorption) among CAPD molecules and the steel interface that possibly affects both cathodic and anodic locations.44

Table 3. Adsorption Parameters for the Corrosion of CS Alloy in 1.0 M H2SO4 Solution at 298 K.

| inhibitor | R2 | S = slope | ± SD | Kads (L mol–1) | ΔGads0 (kJ mol–1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAPD-1 | 0.99982 | 0.975 | 0.0079 | 1.88 × 104 | –37.22 |

| CAPD-2 | 0.99987 | 1.090 | 0.0078 | 1.78 × 104 | –37.07 |

| CAPD-3 | 0.99994 | 1.030 | 0.0051 | 1.69 × 104 | –36.93 |

| CAPD-4 | 0.99971 | 1.050 | 0.0121 | 1.64 × 104 | –36.84 |

The prepared cycloalkanapyridine derivatives demonstrated respectable protection capacities that follow the order CAPD-1 > CAPD-2 > CAPD-3 > CAPD-4 (Table 1). Their corrosion mitigation capabilities may be due to the particular molecular construction characteristics and the occurrence of heteroatoms (nitrogen atom in pyridine ring), which function as robust adsorption positions and augment its inhibition efficacy. The carbon steel alloy interface accumulates a negative charge when dipped into H2SO4 solution because sulfate ions adsorb on the steel interface [Fe + SO42– ··· → (FeSO4)ads]. In an acidic medium, cycloalkanapyridine compounds might be simply protonated, [CAPD] + H+ ↔ [CAPDH] +, because of their great electron density, producing a positively charged CAPD molecule. The physisorption can take place through electrostatic attraction between the metal negatively charged and protonated [CAPDH]+ species.61 Furthermore, chemisorption can take place through attraction of the unshared electrons on hetero atoms and/or aromatic ring π-electrons of CAPD molecules with unoccupied d-orbitals of iron atoms on a carbon steel alloy, leading to construction of coordinate bond.62 As exemplified in Figure 7, the inhibition mechanism has been planned to clarify the adsorption mode of CAPD molecules on the metal substrate. CAPD-1 was the most effective one because it comprises 3C=N and an O atom, so it shares more electrons with the molecule. The CAPD-4 compound is the smallest, most efficient one because it has a solitary C=N and an O atom.

Figure 7.

Proposed mechanisms for inhibitor molecule adsorption on the CS alloy substrate in H2SO4 solution.

To study the effect of temperature influence on the protection efficiency, we measured the PDP measurements of CS in 1.0 M H2SO4 in the absence and presence of 1.0 mM CAPD-1, CAPD-2, CAPD-3, and CAPD-4 at 298–328 K. The calculated jcor (μA cm–2) and inhibition capacity (PCT) are presented in Figure S5. The jcor values for the prepared compounds were smaller than those of the uninhibited system in the investigated temperature range. In addition, from Figure S5B, the prepared CAPD compounds were found to be accurately efficient in hindering the CS corrosion mainly at 50 °C. On the basis of the findings in Figure S5B, the protection capacity values were increased as a solution temperature increased. According to the relationship between T and PCT, the predominance adsorption mechanism is might be chemisorption.61

3.4. Surface Morphology by SEM Micrographs

The SEM micrographs of CS alloy substrates immersed in molar sulfuric acid medium for 48 h before and after dipping in blank and inhibited systems are shown in Figure 8. Before dipping, the morphology of the CS alloys surface was freshly refined and does not contain any contaminants, as realized in Figure 8A. After immersion in molar H2SO4 as a corrosive medium, the morphology of the CS alloy surface becomes rough and porous and contains some cracks, as displayed in Figure 8B, and the CS alloy was harshly rusted (corroded). Figure 8C, D shows the morphological characteristics of the protected systems containing 1.0 × 10–3 mol/L CAPD-4 and CAPD-1, respectively.

Figure 8.

SEM picture of (A) pristine CS alloy, (B) immersed in 1.0 M H2SO4 solution, and immersed in 1.0 M H2SO4 solution containing 1.0 × 10–3 mol/L (C) CAPD-4 and (D) CAPD-1, respectively.

Compared with the corroded CS alloy surface, the specimens dipped in molar sulfuric acid medium with 1.0 × 10–3 mol/L CAPD-4 was slicker; there were rare moderate scratches (Figure 8C). Furthermore, the specimen interface treated with CAPD-1 was nearly as smooth as the pristine CS alloy surface (Figure 8D). These findings show that cycloalkanapyridine derivatives might adsorb on the CS alloy substrate and form a protecting layer, resulting in a decline of contact between the corrosive medium and CS alloy.

3.5. Computational Calculations (DFT)

Figure 9 involves the optimized structures, HOMO, and LUMO distribution for the protonated form of the CAPD molecules, and the correlated theoretical parameters are arranged in Table 4. Pursuant to the FMO theory, the capacity of the acceptor or donor at the inhibitor/steel interface is designated by ELUMO and EHOMO.31 Therefore, the corrosion inhibition capacity is boosted for an inhibitor compound that has large EHOMO and small ELUMO values. As designated in Table 4, the CAPD-1 compound has a maximum EHOMO value of −5.52 eV in comparison CAPD-2, CAPD-3, and CAPD-4 molecules (−5.61, −5.96, −6.26 eV). As revealed in Figure 9, for the compound molecules, it is manifest that the EHOMO level was placed on the pyridinium, cyano, methoxy and ethoxy moieties, signifying that these places are favored for electrophilic attacks on the steel surface. These depictions approve the capability of inhibitor molecule for adsorption on the metal interface and therefore, improvement in the protection proficiency which was in great agreement with the experimental findings. Conversely, the ELUMO value is −4.75 eV for the CAPD-1 molecule (Table 4) lower than CAPD-2, CAPD-3, and CAPD-4 molecules (−4.51, −4.40, −3.41 eV). The lower ELUMO value for the CAPD-1 molecule shows the great protection capacity of the CAPD-1 molecule, which concurs well with the earlier outcomes.

Figure 9.

Optimized configuration and LUMO and HOMO orbital occupation for the studied CAPDs molecules using DFT method.

Table 4. DFT Parameters of the CAPD Compounds.

| params | CAPD-1 | CAPD-2 | CAPD-3 | CAPD-4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EHOMO (eV) | –5.52 | –5.61 | –5.96 | –6.26 |

| ELUMO (eV) | –4.75 | –4.51 | –4.40 | –3.41 |

| ΔE = ELUMO – EHOMO (eV) | 0.77 | 1.10 | 1.56 | 2.85 |

| vertical ionization potential (IP) | 5.52 | 5.61 | 5.96 | 6.26 |

| electron affinity (EA) | 4.75 | 4.51 | 4.40 | 3.41 |

| electronegativity (χ) | 5.13 | 5.06 | 5.18 | 4.83 |

| global hardness (η) | 0.39 | 0.55 | 0.78 | 1.42 |

| global softness (σ) | 2.59 | 1.81 | 1.28 | 0.70 |

| global electrophilicity index (ω) | 34.15 | 23.20 | 17.15 | 8.21 |

| no. of electrons transferred (ΔN) | 2.42 | 1.76 | 1.16 | 0.76 |

| ΔEback-donation | –0.10 | –0.14 | –0.20 | –0.36 |

| dipole moments (μ) Debye | 8.89 | 7.87 | 6.93 | 5.67 |

Similarly, the ΔE (energy gap) is a critical parameter to improve the corrosion protection capacity of the additive compound, which augments as the value of ΔE is diminished.63 As reported in Table 4, the CAPD-1 molecule has a slighter ΔE value (0.77 eV) than CAPD-2, CAPD-3, and CAPD-4 molecules (1.10, 1.56, 2.85 eV), which indicates a greater propensity of the CAPD-1 compound to be adsorbed on the steel surface. The moderately low A and high I for CAPD molecules indicate that CAPD molecules have the ability to exchange electrons with the metal surface and are adsorbed on its surface, forming a protective layer.64,65

Generally, most inhibitors have moderately small electronegativity values (χ), demonstrating the inhibitor electron provision propensity to the steel interface.66 On the other hand, the high electronegativity values (χ) also exhibit a great electron accepting capability of the inhibitor species to receive the electron from steel surface atoms and create a sturdier bond with the steel surface.67 As exhibited in Table 4, it seems that the electronegativity for CAPD molecules is slightly high, indicating that the examined molecules have back-donation ability and construct a hardier bond with the steel surface.

Moreover, the stability and reactivity of the inhibitor molecule can be assessed from the softness (σ) and hardness (η), i.e., soft compounds possess an inhibition capability greater than those of hard compounds because of the smooth electron transfer to the metal surface via the adsorption, so they act as efficient inhibitors for steel corrosion.68 As illustrated in Table 4, CAPD-1 molecules have larger σ values and smaller η values than CAPD-2, CAPD-3, and CAPD-4 molecules, providing smooth provision of electrons to the metal substrate and excellent protection abilities.

Furthermore, the ΔEback-donation and the electron transfer fraction are pivotal strictures for the inhibitor’s ability for electron accepting or donating. Therefore, if the ΔN values are greater than zero, electron transfer from the inhibitor molecule to metal surface atoms is feasible, whereas if the ΔN values are less than zero, electron transfer from steel surface atoms to the inhibitor compound is feasible (i.e., back-contribution).69 According to the data recorded in Table 4, the values of ΔN for the examined molecules are greater than zero, demonstrating that CAPD molecules are able to contribute electrons to the steel surface. Furthermore, the ΔEback-donation will be <0 when η > 0, with the electron relocating from the metal to a molecule, pursued by a back-contribution from the inhibitor molecule to the metal, and this is animatedly favored.70 In Table 4, the values of ΔEback-donation values for CAPD molecules are negative, which shows that back-contribution is desired for the CAPD molecules and forms a forceful bond.71

Furthermore, the dipole-moment is a decisive stricture that favoritisms in predictive mechanism of corrosion protection.72 The augmentation in dipole moment affords boosts the distortion energy and increases the inhibitor adsorption on the metal substrate. Consequently, the increase in dipole moment indicates a progress in corrosion inhibition ability.73 As divulged in Table 4, the CAPD-1 molecule has superior dipole moment value (8.89 debye) than CAPD-2, CAPD-3, and CAPD-4 molecules (7.87, 6.93, and 5.67 debye), which supports the greater affinity for the CAPD-1 compound to be adsorbed on the metal interface and enrich the protection.

The local reactivity of the CAPD compounds can be evaluated by reckoning the Fukui directories (fk+ and fk), the local electrophilicity (ωk±), the local softness descriptor (σk), and the dual descriptors (Δfk, Δσk, and Δωk) from the following equations:74

| 18 |

| 19 |

| 20 |

| 21 |

| 22 |

For clarification, the most meaningful results are revealed in Table S1. The evaluated Fukui directories (Table S1) detected for the inhibitor species are ascribed to the sites at which the CAPD molecules will be adsorbed onto the Fe interface. Furthermore, the local dual descriptors are more accurate and comprise more tools than the Fukui directories (fk+ and fk), the electrophilicity (ωk±), and the local softness (σk); the graphical demonstration of the dual local descriptors of the greatest illustrative active centers are displayed in Figure 10. The attained outcomes show that the sites with the Δfk, Δσk, and Δωk < 0 have the propensity to relocate electron to the steel surface. On the other hand, those sites with Δfk, Δσk, and Δωk > 0 have the ability to accept an electron from the steel. As could be seen in Figure 10, the highest active centers for electron donation are at C1, C4–C8, N9, C10, C12, N13, C14, N18, O24, N25 for CAPD-1; C1, C3–C6, C8, N9, C10, C12, N13, C14, N18, O24, N25 for CAPD-2; C1, C2, C4, C7, C10, C11, N12, N13, C14, C15, C17, C20, N21, C23, O24, N25, C26 for CAPD-3; and C1, C4, C7, C8, C10, C11, N13, C17, C18, C19, C20–C22, O24–O26, N27, C28 for CAPD-4. The active accepting centers are at C2, C15, C17, C19–C22 for CAPD-1; C2, C11, C15–C17, C19–C23 for CAPD-2; C3, C5, C6, C8, C9, C16, C18, C19, C22 for CAPD-3; and C2, C6, C12, C14–C16, C23, C30, C31 for CAPD-4.

Figure 10.

Graphical depiction of the dual descriptors (Δf, Δσ, and Δω) for the maximum active centers of the studied CAPDs molecules using the DFT method.

Finally, molecular electrostatic mapping potential (MEP) could divulge the efficient sides of the CAPDs molecules and is evaluated through the Dmol3 module. The MEP maps is a 3D image descriptor aimed at discriminating the net electrostatic influence originated on a compound by the complete charge sharing.75 In MEP mapping revealed in Figure 11, the red area depicts the great electron density extent; where the MEP is exceedingly negative (nucleophilic interaction). In contrast, the blue area designate the maximum positive zone (electrophilic attraction).76 A visual investigation of Figure 11 supports that the extreme negative portions are mainly above nitrogen and oxygen atoms; however, there is a lower electron density over the aromatic system (benzene rings). These centers with greater electron density (i.e., red zone) in additive molecules may be the best for adsorption on the steel surface, creating durable adsorbed protecting films.

Figure 11.

Graphical presentation of the MEP of the CAPD molecules using DFT method.

Conclusively, from DFT calculations, we can deduce that the CAPD compounds are effective inhibitors for CS alloy for many reasons such as high EHOMO, low ΔE, low η, high σ, and high ΔN, which indicate the donation abilities of CAPD molecules and the strong adsorption on CS alloys via adsorption centers. These centers are disclosed via the local dual descriptors and MEP, which are N and O atoms and benzene rings. Finally, the DFT calculations revealed that the order of inhibition efficiency was CAPD-1 > CAPD-2 > CAPD-3 > CAPD-4, which agrees with experimental findings.

3.6. MC Simulations

MC simulations were performed to distinguish the adsorption of the additive molecules with the steel interface in addition to suggesting an apparent idea for the adsorption process mechanism. Consequently, Figure 12 reveals the highest appropriate adsorption formations for the protonated form of the CAPD molecules on the metal interface in an acidic solution accomplished by the module of the adsorption locator, which is represented in a nearly flat arrangement, advising an enhancement in the adsorption and supreme surface covered part.77 Additionally, the reckoned results for the adsorption energies from the MC imitations are divulged in Table 5. It appears that the CAPD-1 molecule (−6241.48 kcal mol–1) has a superior negative value of adsorption energy compared to the CAPD-2, CAPD-3, and CAPD-4 molecules (−6216.32, −6161.43, −6060.88 kcal mol–1), which supposes the energetic adsorption of the CAPD-1 molecule on the metal interface, producing a steady adsorbed film and protecting the metal from deterioration. These results are in agreement with the empirical findings.78 In addition, Table 5 shows obviously that the adsorption energy value for the CAPD-1 molecule for the optimization pregeometry stage, i.e., unrelaxed (−5760.45 kcal mol–1), is more negative than that for the CAPD-2, CAPD-3, and CAPD-4 molecules (−5738.96, −5718.02, −5643.42 kcal mol–1), and for the optimization postgeometry stage, i.e., relaxed (−481.02) is greater than that for the CAPD-2, CAPD-3, and CAPD-4 molecules (−477.37, −443.42, −417.46 kcal mol–1), confirming a greater inhibition capacity for the CAPD-1 molecule than for the CAPD-2, CAPD-3, and CAPD-4 molecules.

Figure 12.

Highest proper adsorption arrangement for the CAPD molecules on the iron (110) surface accomplished by an adsorption locator module.

Table 5. Data and Descriptors Computed by the MC Simulations for the Adsorption of the CAPD Molecules on Fe (110).

| dEads/dNi (kcal mol–1) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| corrosion systems | adsorption energy/kcal mol–1 | rigid adsorption energy (kcal mol–1) | deformation energy/kcal mol–1 | inhibitor | SO42– ions | hydronium | water |

| Fe (110) | –6241.48 | –5760.45 | –481.02 | –471.73 | –119.50 | –83.43 | –13.82 |

| CAPD-1 | |||||||

| water | |||||||

| hydronium | |||||||

| SO42– ions | |||||||

| Fe (110) | –6216.32 | –5738.96 | –477.37 | –454.99 | –118.28 | –83.40 | –13.80 |

| CAPD-2 | |||||||

| water | |||||||

| hydronium | |||||||

| SO42– ions | |||||||

| Fe (110) | –6161.43 | –5718.02 | –443.42 | –429.90 | –118.54 | –83.37 | –13.36 |

| CAPD-3 | |||||||

| water | |||||||

| hydronium | |||||||

| SO42– ions | |||||||

| Fe (110) | –6060.88 | –5643.42 | –417.46 | –405.34 | –118.45 | –83.01 | –13.44 |

| CAPD-4 | |||||||

| water | |||||||

| hydronium | |||||||

| SO42– ions | |||||||

The values of dEads/dNi clarify the steel/adsorbate arrangement energy if adsorbed H2O or the inhibitor molecule has been excluded.79 The values of dEads/dNi for CAPD-1 molecules (−471.73 kcal mol–1) are higher than those for CAPD-2, CAPD-3, and CAPD-4 molecules (−454.99, −4239.90, −405.34 kcal mol–1), as revealed in Table 5, which affirms the outstanding adsorption of the CAPD-1 molecule compared to the CAPD-2, CAPD-3, and CAPD-4 molecules. Furthermore, the dEads/dNi values for hydronium ions, water molecules and sulfate ions are about −83.30, −13.61, and −118.69 kcal mol–1, respectively. These values are small in comparison with the CAPD compound values, indicating the more forceful adsorption of CAPD molecules than hydronium ions, H2O molecules, and sulfate ions, which enhanced the exchange of H2O molecules, hydronium ions, and sulfate ions by CAPD molecules. Consequently, the CAPD molecules are conclusively adsorbed on the metal interface and form a strong adsorbed shielding film, which brings about corrosion inhibition for the steel interface in a corrosive environment, as verified by experimental and theoretical research.

4. Conclusions

In the current exploration, the designing of a new heterocyclic compounds of 6,7-dihydro-5H-cyclopenta[b]pyridine-3-carbonitrile derivatives (CAPDs) and their protection effect was inspected via diverse morphological (SEM) and electrochemical (OCP, PDP, EIS) inspections and combined theoretical studies (MC simulations and DFT calculations). The different empirical approaches were in good covenant, displaying that CAPD derivatives are efficient inhibitors, and the protection capacities augmented with the increase in inhibitor concentration, reaching to the maximum values 97.7% for CAPD-1 at 1.0 × 10–3. Furthermore, the PDP plots exhibited that the synthesized CAPD derivatives could control the process of corrosion by a mixed-kind mechanism. Surface morphology investigations revealed that by augmenting the surfactant dose the steel heterogeneity declined considerably. Furthermore, the adsorption of surfactants on CS substrate follows the Langmuir model involving physisorption and chemisorption. Together with experimental examinations, the DFT calculations showed that the effective electron-rich parts of CAPD molecules are the prime sites in their adsorption. MC simulations indicate that the occurrence of the oxygen and nitrogen atoms in CAPD derivatives structures play a significant role in the adsorption method. In covenant with the experiential results, the theoretical findings demonstrated that the order of inhibition efficiency was CAPD-1 > CAPD-2 > CAPD-3 > CAPD-4. Finally, this report affords a facile synthesis of 2-alkoxy-4-(aryl)-7-(aryl-2-ylmethylidene)-6,7-dihydro-5H-cyclopenta[b]pyridine-3-carbonitrile derivatives (CAPD-1 to CAPD-4) containing electron-donating groups (pyridine and ortho methoxy phenyl). In future work, the study of electron-withdrawing groups will be our interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported through the Annual Funding track by the Deanship of Scientific Research, Vice Presidency for Graduate Studies and Scientific Research, King Faisal University, Saudi Arabia [GRANT860].

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.2c02639.

Additional experimental descriptions of synthesis of compounds 4a–k; characterization data of CAPD-1–CAPD-4 compounds; 1H and 13C NMR spectra of CAPD-1–CAPD-4; change in corrosion current density, jcor (μAcm–2) and protection capacity, PCT, of CS alloy in 1.0 M H2SO4 solution containing 1.0 mM of CAPD-1, CAPD-2, CAPD-3, and CAPD-4 at different temperatures; and the evaluated Fukui directories (PDF)

Author Contributions

H.M.A.E.-L.: Conceptualization, Supervision, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Formal analysis, Data curation, Funding acquisition, Writing-original draft, Writing-review and editing. M. M.K.: Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Funding acquisition, Writing-original draft, Writing-review and editing. K.S.i: Conceptualization, Supervision, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Formal analysis, Data curation, Funding acquisition, Writing-original draft, Writing-review and editing. A.A.A.: Conceptualization, Supervision, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Formal analysis, Data curation, Funding acquisition, Writing-original draft, Writing-review and editing.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Mao T.; Huang H.; Liu D.; Shang X.; Wang W.; Wang L. Novel Cationic Gemini Ester Surfactant as an Efficient and Eco-Friendly Corrosion Inhibitor for Carbon Steel in HCl Solution. J. Mol. Liq. 2021, 339, 117174. 10.1016/j.molliq.2021.117174. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q. H.; Hou B. S.; Li Y. Y.; Lei Y.; Wang X.; Liu H. F.; Zhang G. A. Two Amino Acid Derivatives as High Efficient Green Inhibitors for the Corrosion of Carbon Steel in CO2-Saturated Formation Water. Corros. Sci. 2021, 189, 109596. 10.1016/j.corsci.2021.109596. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Abdallah M.; Altass H. M.; Al-Gorair A. S.; Al-Fahemi J. H.; Jahdaly B. A. A. L.; Soliman K. A. Natural Nutmeg Oil as a Green Corrosion Inhibitor for Carbon Steel in 1.0 M HCl Solution: Chemical, Electrochemical, and Computational Methods. J. Mol. Liq. 2021, 323, 115036. 10.1016/j.molliq.2020.115036. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Damej M.; Benmessaoud M.; Zehra S.; Kaya S.; Lgaz H.; Molhi A.; Labjar N.; El Hajjaji S.; Alrashdi A. A.; Lee H. S. Experimental and Theoretical Explorations of S-Alkylated Mercaptobenzimidazole Derivatives for Use as Corrosion Inhibitors for Carbon Steel in HCl. J. Mol. Liq. 2021, 331, 115708. 10.1016/j.molliq.2021.115708. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thoume A.; Benmessaoud Left D.; Elmakssoudi A.; Benhiba F.; Zarrouk A.; Benzbiria N.; Warad I.; Dakir M.; Azzi M.; Zertoubi M. Chalcone Oxime Derivatives as New Inhibitors Corrosion of Carbon Steel in 1 M HCl Solution. J. Mol. Liq. 2021, 337, 116398. 10.1016/j.molliq.2021.116398. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chaubey N.; Savita; Qurashi A.; Chauhan D. S.; Quraishi M. A. Frontiers and Advances in Green and Sustainable Inhibitors for Corrosion Applications: A Critical Review. J. Mol. Liq. 2021, 321, 114385. 10.1016/j.molliq.2020.114385. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y.; Zhou L.; Tan B.; Xiang B.; Zhang S.; Wei S.; Wang B.; Yao Q. Two Common Antihistamine Drugs as High-Efficiency Corrosion Inhibitors for Copper in 0.5M H2SO4. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2021, 123, 11–20. 10.1016/j.jtice.2021.05.027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra A.; Aslam J.; Verma C.; Quraishi M. A.; Ebenso E. E. Imidazoles as Highly Effective Heterocyclic Corrosion Inhibitors for Metals and Alloys in Aqueous Electrolytes: A Review. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2020, 114, 341–358. 10.1016/j.jtice.2020.08.034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Abdellattif M. H.; Alrefaee S. H.; Dagdag O.; Verma C.; Quraishi M. A. Calotropis Procera Extract as an Environmental Friendly Corrosion Inhibitor: Computational Demonstrations. J. Mol. Liq. 2021, 337 (2), 116954. 10.1016/j.molliq.2021.116954. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kobzar Y. L.; Fatyeyeva K. Ionic Liquids as Green and Sustainable Steel Corrosion Inhibitors: Recent Developments. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 425, 131480. 10.1016/j.cej.2021.131480. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Verma C.; Rhee K. Y.; Quraishi M. A.; Ebenso E. E. Pyridine Based N-Heterocyclic Compounds as Aqueous Phase Corrosion Inhibitors: A Review. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2020, 117, 265–277. 10.1016/j.jtice.2020.12.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- El Ibrahimi B.; Jmiai A.; El Mouaden K.; Oukhrib R.; Soumoue A.; El Issami S.; Bazzi L. Theoretical Evaluation of Some α-Amino Acids for Corrosion Inhibition of Copper in Acidic Medium: DFT Calculations, Monte Carlo Simulations and QSPR Studies. J. King Saud Univ. - Sci. 2020, 32 (1), 163–171. 10.1016/j.jksus.2018.04.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw P.; Obot I. B.; Yadav M. Functionalized 2-Hydrazinobenzothiazole with Carbohydrates as a Corrosion Inhibitor: Electrochemical, XPS, DFT and Monte Carlo Simulation Studies. Mater. Chem. Front. 2019, 3 (5), 931–940. 10.1039/C9QM00096H. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon M. M.; Umoren S. A.; Quraishi M. A.; Jafar Mazumder M. A. Corrosion Inhibition of N80 Steel in Simulated Acidizing Environment by N-(2-(2-Pentadecyl-4,5-Dihydro-1H-Imidazol-1-YL) Ethyl) Palmitamide. J. Mol. Liq. 2019, 273, 476–487. 10.1016/j.molliq.2018.10.032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey T. J.; Walsh F. C.; Nahlé A. H. A Review of Inhibitors for the Corrosion of Transition Metals in Aqueous Acids. J. Mol. Liq. 2018, 266, 160–175. 10.1016/j.molliq.2018.06.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Verma C.; Lgaz H.; Verma D. K.; Ebenso E. E.; Bahadur I.; Quraishi M. A. Molecular Dynamics and Monte Carlo Simulations as Powerful Tools for Study of Interfacial Adsorption Behavior of Corrosion Inhibitors in Aqueous Phase: A Review. J. Mol. Liq. 2018, 260, 99–120. 10.1016/j.molliq.2018.03.045. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Albayati M. R.; Moustafa A. H.; Abdelhamed A. A. An Efficient Synthesis of Benzylidene-2-Alkoxy-4-Aryl-2,3-Cycloalkenopyridine-3-Carbonitrile Derivatives. Synth. Commun. 2019, 49 (19), 2546–2553. 10.1080/00397911.2019.1633672. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J.-F.; Tu S.-J.; Feng J.-C. One-Step Synthesis of Pyridine Derivatives from Malononitrile with Bisarylidenecycloalkanone under Microwave Irradiation. J. Chem. Res. 2001, 2001 (7), 268–269. 10.3184/030823401103169874. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Öztürk Ş.; Gürdere M. B.; Gezegen H.; Ceylan M.; Budak Y. Potassium Carbonate Mediated One-Pot Synthesis and Antimicrobial Activities of 2-Alkoxy-4-(Aryl)-5 H-Indeno [ 1, 2-b ] Pyridine-3-Carbonitriles. Org. Commun. 2016, 9 (4), 125–132. [Google Scholar]

- Zolfigol M. A.; Kiafar M.; Yarie M.; Taherpour A.; Saeidi-Rad M. Experimental and Theoretical Studies of the Nanostructured {Fe3O4@SiO2@(CH2)3Im}C(CN)3 Catalyst for 2-Amino-3-Cyanopyridine Preparation via an Anomeric Based Oxidation. RSC Adv. 2016, 6 (55), 50100–50111. 10.1039/C6RA12299J. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamaddon F.; Azadi D. Synthesis and Identification of Nicotinium Sulfate (3-(1-Methylpyrrolidin-2-Yl)Pyridine:H2SO4) from Tobacco-Extracted Nicotine: A Protic Ionic Liquid and Biocompatible Catalyst for Selective Acetylation of Amines. J. Mol. Liq. 2018, 255, 406–412. 10.1016/j.molliq.2017.12.107. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Verma C.; Olasunkanmi L. O.; Ebenso E. E.; Quraishi M. A. Substituents Effect on Corrosion Inhibition Performance of Organic Compounds in Aggressive Ionic Solutions: A Review. J. Mol. Liq. 2018, 251, 100–118. 10.1016/j.molliq.2017.12.055. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guo L.; Obot I. B.; Zheng X.; Shen X.; Qiang Y.; Kaya S.; Kaya C. Theoretical Insight into an Empirical Rule about Organic Corrosion Inhibitors Containing Nitrogen, Oxygen, and Sulfur Atoms. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2017, 406, 301–306. 10.1016/j.apsusc.2017.02.134. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khalaf M. M.; Tantawy A. H.; Soliman K. A.; Abd El-Lateef H. M. Cationic Gemini-Surfactants Based on Waste Cooking Oil as New ‘Green’ Inhibitors for N80-Steel Corrosion in Sulphuric Acid: A Combined Empirical and Theoretical Approaches. J. Mol. Struct. 2020, 1203, 127442. 10.1016/j.molstruc.2019.127442. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saleh M. M.; Mahmoud M. G.; Abd El-Lateef H. M. Comparative Study of Synergistic Inhibition of Mild Steel and Pure Iron by 1-Hexadecylpyridinium Chloride and Bromide Ions. Corros. Sci. 2019, 154, 70–79. 10.1016/j.corsci.2019.03.048. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Abd El-Lateef H. M.; Mohamed I. M. A.; Zhu J.-H.; Khalaf M. M. An Efficient Synthesis of Electrospun TiO2-Nanofibers/Schiff Base Phenylalanine Composite and Its Inhibition Behavior for C-Steel Corrosion in Acidic Chloride Environments. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2020, 112, 306–321. 10.1016/j.jtice.2020.06.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Abd El-Lateef H. M.; Sayed A. R.; Shalabi K. Synthesis and Theoretical Studies of Novel Conjugated Polyazomethines and Their Application as Efficient Inhibitors for C1018 Steel Pickling Corrosion Behavior. Surfaces and Interfaces 2021, 23, 101037. 10.1016/j.surfin.2021.101037. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- El-Lateef H. M. A.; Abdallah Z. A.; Ahmed M. S. M. Solvent-Free Synthesis and Corrosion Inhibition Performance of Ethyl 2-(1,2,3,6-Tetrahydro-6-Oxo-2-Thioxopyrimidin-4-Yl)Ethanoate on Carbon Steel in Pickling Acids: Experimental, Quantum Chemical and Monte Carlo Simulation Studies. J. Mol. Liq. 2019, 296, 111800. 10.1016/j.molliq.2019.111800. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mittal A.; Kakkar R. A Theoretical Assessment of the Structural and Electronic Features of Some Retrochalcones. Int. J. Quantum Chem. 2021, 121 (24), 1–12. 10.1002/qua.26797. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dehghani A.; Mostafatabar A. H.; Bahlakeh G.; Ramezanzadeh B. A Detailed Study on the Synergistic Corrosion Inhibition Impact of the Quercetin Molecules and Trivalent Europium Salt on Mild Steel; Electrochemical/Surface Studies, DFT Modeling, and MC/MD Computer Simulation. J. Mol. Liq. 2020, 316, 113914. 10.1016/j.molliq.2020.113914. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Y.; Chen S.; Guo W.; Zhang Y.; Liu G. Inhibition of Iron Corrosion by 5,10,15,20-Tetraphenylporphyrin and 5,10,15,20-Tetra-(4-Chlorophenyl)Porphyrin Adlayers in 0.5 M H2SO4 Solutions. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2007, 602 (1), 115–122. 10.1016/j.jelechem.2006.12.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Abd El-Lateef H. M.; Shalabi K.; Tantawy A. H. Corrosion Inhibition and Adsorption Features of Novel Bioactive Cationic Surfactants Bearing Benzenesulphonamide on C1018-Steel under Sweet Conditions: Combined Modeling and Experimental Approaches. J. Mol. Liq. 2020, 320, 114564. 10.1016/j.molliq.2020.114564. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Abd El-Lateef H. M.; Shalabi K.; Tantawy A. H. Corrosion Inhibition of Carbon Steel in Hydrochloric Acid Solution Using Newly Synthesized Urea-Based Cationic Fluorosurfactants: Experimental and Computational Investigations. New J. Chem. 2020, 44 (41), 17791–17814. 10.1039/D0NJ04004E. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bouassiria M.; Laabaissi T.; Benhiba F.; El Faydy M.; Fakhry H.; Oudda H.; Assouag M.; Touir R.; Guenbour A.; Lakhrissi B.; Warad I.; Zarrouk A. Corrosion Inhibition Effect of 5-(4-Methylpiperazine)-Methylquinoline-8-Ol on Carbon Steel in Molar Acid Medium. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2021, 123, 108366. 10.1016/j.inoche.2020.108366. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Verma C.; Quraishi M. A.; Ebenso E. E. Quinoline and Its Derivatives as Corrosion Inhibitors: A Review. Surfaces and Interfaces 2020, 21, 100634. 10.1016/j.surfin.2020.100634. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Murmu M.; Saha S. K.; Bhaumick P.; Murmu N. C.; Hirani H.; Banerjee P. Corrosion Inhibition Property of Azomethine Functionalized Triazole Derivatives in 1 Mol L–1 HCl Medium for Mild Steel: Experimental and Theoretical Exploration. J. Mol. Liq. 2020, 313, 113508. 10.1016/j.molliq.2020.113508. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Obot I. B.; Macdonald D. D.; Gasem Z. M. Density Functional Theory (DFT) as a Powerful Tool for Designing New Organic Corrosion Inhibitors. Part 1: An Overview. Corros. Sci. 2015, 99, 1–30. 10.1016/j.corsci.2015.01.037. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saha S. K.; Dutta A.; Ghosh P.; Sukul D.; Banerjee P. Adsorption and Corrosion Inhibition Effect of Schiff Base Molecules on the Mild Steel Surface in 1 M HCl Medium: A Combined Experimental and Theoretical Approach. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2015, 17 (8), 5679–5690. 10.1039/C4CP05614K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saha S. K. S. K.; Murmu M.; Murmu N. C. N. C.; Banerjee P. Evaluating Electronic Structure of Quinazolinone and Pyrimidinone Molecules for Its Corrosion Inhibition Effectiveness on Target Specific Mild Steel in the Acidic Medium: A Combined DFT and MD Simulation Study. J. Mol. Liq. 2016, 224, 629–638. 10.1016/j.molliq.2016.09.110. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Upadhyay A.; Purohit A. K.; Mahakur G.; Dash S.; Kar P. K. Verification of Corrosion Inhibition of Mild Steel by Some 4-Aminoantipyrine-Based Schiff Bases – Impact of Adsorbate Substituent and Cross-Conjugation. J. Mol. Liq. 2021, 333, 115960. 10.1016/j.molliq.2021.115960. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Farag A. A.; Ali T. A. The Enhancing of 2-Pyrazinecarboxamide Inhibition Effect on the Acid Corrosion of Carbon Steel in Presence of Iodide Ions. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2015, 21, 627–634. 10.1016/j.jiec.2014.03.030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cao S.; Liu D.; Ding H.; Wang J.; Lu H.; Gui J. Task-Specific Ionic Liquids as Corrosion Inhibitors on Carbon Steel in 0.5 M HCl Solution: An Experimental and Theoretical Study. Corros. Sci. 2019, 153, 301–313. 10.1016/j.corsci.2019.03.035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fekry A. M.; Mohamed R. R. Acetyl Thiourea Chitosan as an Eco-Friendly Inhibitor for Mild Steel in Sulphuric Acid Medium. Electrochim. Acta 2010, 55 (6), 1933–1939. 10.1016/j.electacta.2009.11.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arellanes-Lozada P.; Díaz-Jiménez V.; Hernández-Cocoletzi H.; Nava N.; Olivares-Xometl O.; Likhanova N. V. Corrosion Inhibition Properties of Iodide Ionic Liquids for API 5L X52 Steel in Acid Medium. Corros. Sci. 2020, 175, 108888. 10.1016/j.corsci.2020.108888. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs-Godec R.; Pavlović M. G. Synergistic Effect between Non-Ionic Surfactant and Halide Ions in the Forms of Inorganic or Organic Salts for the Corrosion Inhibition of Stainless-Steel X4Cr13 in Sulphuric Acid. Corros. Sci. 2012, 58, 192–201. 10.1016/j.corsci.2012.01.027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hsissou R.; Abbout S.; Benhiba F.; Seghiri R.; Safi Z.; Kaya S.; Briche S.; Serdaroğlu G.; Erramli H.; Elbachiri A.; Zarrouk A.; El Harfi A. Insight into the Corrosion Inhibition of Novel Macromolecular Epoxy Resin as Highly Efficient Inhibitor for Carbon Steel in Acidic Mediums: Synthesis, Characterization, Electrochemical Techniques, AFM/UV–Visible and Computational Investigations. J. Mol. Liq. 2021, 337, 116492. 10.1016/j.molliq.2021.116492. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon M. M.; Gerengi H.; Kaya T.; Kaya E.; Umoren S. A. Synergistic Inhibition of St37 Steel Corrosion in 15% H2SO4 Solution by Chitosan and Iodide Ion Additives. Cellulose 2017, 24 (2), 931–950. 10.1007/s10570-016-1128-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng X.; Zhang S.; Li W.; Gong M.; Yin L. Experimental and Theoretical Studies of Two Imidazolium-Based Ionic Liquids as Inhibitors for Mild Steel in Sulfuric Acid Solution. Corros. Sci. 2015, 95, 168–179. 10.1016/j.corsci.2015.03.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Onyeachu I. B.; Obot I. B.; Sorour A. A.; Abdul-Rashid M. I. Green Corrosion Inhibitor for Oilfield Application I: Electrochemical Assessment of 2-(2-Pyridyl) Benzimidazole for API X60 Steel under Sweet Environment in NACE Brine ID196. Corros. Sci. 2019, 150, 183–193. 10.1016/j.corsci.2019.02.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sha J.-Y.; Ge H.-H.; Wan C.; Wang L.-T.; Xie S.-Y.; Meng X.-J.; Zhao Y.-Z. Corrosion Inhibition Behaviour of Sodium Dodecyl Benzene Sulphonate for Brass in an Al2O3 Nanofluid and Simulated Cooling Water. Corros. Sci. 2019, 148, 123–133. 10.1016/j.corsci.2018.12.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gerengi H.; Sen N.; Uygur I.; Solomon M. M. Corrosion Response of Ultra-High Strength Steels Used for Automotive Applications. Mater. Res. Express 2019, 6 (8), 0865a6. 10.1088/2053-1591/ab2178. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ghelichkhah Z.; Dehkharghani F. K.; Sharifi-Asl S.; Obot I. B.; Macdonald D. D.; Farhadi K.; Avestan M. S.; Petrossians A. The Inhibition of Type 304LSS General Corrosion in Hydrochloric Acid by the New Fuchsin Compound. Corros. Sci. 2021, 178, 109072. 10.1016/j.corsci.2020.109072. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Darowicki K. Theoretical Description of the Measuring Method of Instantaneous Impedance Spectra. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2000, 486 (2), 101–105. 10.1016/S0022-0728(00)00110-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Slepski P.; Szocinski M.; Lentka G.; Darowicki K. Novel Fast Non-Linear Electrochemical Impedance Method for Corrosion Investigations. Measurement 2021, 173, 108667. 10.1016/j.measurement.2020.108667. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Darowicki K.; Orlikowski J.; Lentka G. Instantaneous Impedance Spectra of a Non-Stationary Model Electrical System. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2000, 486 (2), 106–110. 10.1016/S0022-0728(00)00111-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon M. M.; Gerengi H.; Umoren S. A. Carboxymethyl Cellulose/Silver Nanoparticles Composite: Synthesis, Characterization and Application as a Benign Corrosion Inhibitor for St37 Steel in 15% H2SO4Medium. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9 (7), 6376–6389. 10.1021/acsami.6b14153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ituen E.; Akaranta O.; James A. Evaluation of Performance of Corrosion Inhibitors Using Adsorption Isotherm Models: An Overview. Chem. Sci. Int. J. 2017, 18 (1), 1–34. 10.9734/CSJI/2017/28976. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C.; Zou C.; Cao Y. Electrochemical and Isothermal Adsorption Studies on Corrosion Inhibition Performance of β-Cyclodextrin Grafted Polyacrylamide for X80 Steel in Oil and Gas Production. J. Mol. Struct. 2021, 1228, 129737. 10.1016/j.molstruc.2020.129737. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Abd El Rehim S. S.; Sayyah S. M.; El-Deeb M. M.; Kamal S. M.; Azooz R. E. Adsorption and Corrosion Inhibitive Properties of P(2-Aminobenzothiazole) on Mild Steel in Hydrochloric Acid Media. Int. J. Ind. Chem. 2016, 7 (1), 39–52. 10.1007/s40090-015-0065-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Karthikaiselvi R.; Subhashini S. Study of Adsorption Properties and Inhibition of Mild Steel Corrosion in Hydrochloric Acid Media by Water Soluble Composite Poly (Vinyl Alcohol-Omethoxy Aniline). J. Assoc. Arab Univ. Basic Appl. Sci. 2014, 16 (1), 74–82. 10.1016/j.jaubas.2013.06.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Farag A. A.; Hegazy M. A. Synergistic Inhibition Effect of Potassium Iodide and Novel Schiff Bases on X65 Steel Corrosion in 0.5M H2SO4. Corros. Sci. 2013, 74, 168–177. 10.1016/j.corsci.2013.04.039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kousar K.; Walczak M. S.; Ljungdahl T.; Wetzel A.; Oskarsson H.; Restuccia P.; Ahmad E. A.; Harrison N. M.; Lindsay R. Corrosion Inhibition of Carbon Steel in Hydrochloric Acid: Elucidating the Performance of an Imidazoline-Based Surfactant. Corros. Sci. 2021, 180, 109195. 10.1016/j.corsci.2020.109195. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Abd El-Lateef H. M.; Shalabi K.; Tantawy A. H. Corrosion Inhibition and Adsorption Features of Novel Bioactive Cationic Surfactants Bearing Benzenesulphonamide on C1018-Steel under Sweet Conditions: Combined Modeling and Experimental Approaches. J. Mol. Liq. 2020, 320, 114564. 10.1016/j.molliq.2020.114564. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arrouji S. El; Karrouchi K.; Warad I.; Berisha A.; Alaoui K. I.; Rais Z.; Radi S.; Taleb M.; Ansar M.; Zarrouk A. Multidimensional Analysis for Corrosion Inhibition by New Pyrazoles on Mild Steel in Acidic Environment : Experimental and Computational Approach. Chem. Data Collect. 2022, 40 (March), 100885. 10.1016/j.cdc.2022.100885. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ould Abdelwedoud B.; Damej M.; Tassaoui K.; Berisha A.; Tachallait H.; Bougrin K.; Mehmeti V.; Benmessaoud M. Inhibition Effect of N-Propargyl Saccharin as Corrosion Inhibitor of C38 Steel in 1 M HCl, Experimental and Theoretical Study. J. Mol. Liq. 2022, 354, 118784. 10.1016/j.molliq.2022.118784. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Palaniappan N.; Cole I. S.; Kuznetsov A. E. Experimental and Computational Studies of Graphene Oxide Covalently Functionalized by Octylamine: Electrochemical Stability, Hydrogen Evolution, and Corrosion Inhibition of the AZ13 Mg Alloy in 3.5% NaCl. RSC Adv. 2020, 10 (19), 11426–11434. 10.1039/C9RA10702A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukovits I.; Kálmán E.; Zucchi F. Corrosion Inhibitors—Correlation between Electronic Structure and Efficiency. CORROSION 2001, 57 (1), 3–8. 10.5006/1.3290328. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yesudass S.; Olasunkanmi L. O. L.; Bahadur I.; Kabanda M. M. M. M.; Obot I. B. B.; Ebenso E. E. E. Experimental and Theoretical Studies on Some Selected Ionic Liquids with Different Cations/Anions as Corrosion Inhibitors for Mild Steel in Acidic Medium. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2016, 64, 252–268. 10.1016/j.jtice.2016.04.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Debab H.; Douadi T.; Daoud D.; Issaadi S.; Chafaa S. Electrochemical and Quantum Chemical Studies of Adsorption and Corrosion Inhibition of Two New Schiff Bases on Carbon Steel in Hydrochloric Acid Media. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2018, 13 (7), 6958–6977. 10.20964/2018.07.19. [DOI] [Google Scholar]