Abstract

Background

Non-adherence to medication is a major obstacle in the treatment of depressive disorders. We systematically reviewed the literature to evaluate the effectiveness of interventions aimed at improving adherence to medication among adults with depressive disorders with emphasis on initiation and implementation phase.

Methods

We searched Medline, EMBASE, The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), PsycINFO, Social Science Citation Index and Science Citation Index for randomized or non-randomized controlled trials up to January 2022. Risk of bias was assessed using the criteria of the Cochrane Collaboration. Meta-analyses, cumulative and meta-regression analyses for adherence were conducted.

Results

Forty-six trials (n = 24,324) were included. Pooled estimate indicates an increase in the probability of adherence to antidepressants at 6 months with the different types of interventions (OR 1.33; 95% CI: 1.09 to 1.62). The improvement in adherence is obtained from 3 months (OR 1.62, 95% CI: 1.25 to 2.10) but it is attenuated at 12 months (OR 1.25, 95% CI: 1.02 to 1.53). Selected articles show methodological differences, mainly the diversity of both the severity of the depressive disorder and intervention procedures. In the samples of these studies, patients with depression and anxiety seem to benefit most from intervention (OR 2.77, 95% CI: 1.74 to 4.42) and collaborative care is the most effective intervention to improve adherence (OR 1.88, 95% CI: 1.40 to 2.54).

Conclusions

Our findings indicate that interventions aimed at improving adherence to medication among adults with depressive disorders are effective up to six months. However, the evidence on the effectiveness of long-term adherence is insufficient and supports the need for further research efforts.

Trial registration

International Prospective Register for Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) number: CRD42017065723.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12888-022-04120-w.

Keywords: Major Depressive Disorder, Meta-analysis, Systematic review, Treatment Adherence

Introduction

Depression is a common mental disorder typically chronic, disabling and frequently comorbid that affects more than 260 million people every year [1] and causes considerable personal suffering and has great economic costs for Western societies [2]. Depression was expected to be the leading cause of disability in 2030 [3] but, as early as 2021, it was declared the leading cause of disability worldwide and a major contributor to the overall global burden of disease according to the World Health Organization [4].

Although pharmacological treatment of depressive disorders has shown a considerable efficacy, patients do not always take their medication as instructed. When talking about the behaviors of patients in taking medication, adherence and persistence need to be examined.

Medication adherence can be defined as the process to which a patient acts within the prescribed range and dose of a dosage regimen, described by three quantifiable phases: 1) initiation, when patient takes the first dose; 2) implementation, defined as the process to which a patient's actual dosing corresponds to the prescribed dosing regimen; and 3) discontinuation, when the next dose to be taken is omitted and no more doses are taken thereafter [5]. Persistence refers to the duration of time from initiation to discontinuation of therapy [5]. In this sense, non-adherence to appropriately prescribed medicines remains a major challenge in current clinical psychiatric practice that compromises the efficacy of available treatments and interferes with patient recovery [6].

The impact of non-adherence to antidepressants increases the likelihood of relapse and/or recurrence, emergency department visits, and hospitalization rates; increases symptom severity and decreases treatment response and remission rates [7]. Non-adherence subsequently translates to an increase in medical and total healthcare utilization [7]. Available literature shows primary medication adherence (when a patient properly fills the first prescription for a new medication) rates ranging between 74 and 82% [8, 9], but unfortunately, approximately 50% of patients prematurely discontinue therapy [10, 11].

Socio-demographic variables, such as age, positive attitudes to prescribed medication and previous experiences were found to be factors predicting better adherence in patients with depressive disorders. Conversely, experience of side effects, dissatisfaction with treatment and a poor patient–professional relationship were found to be associated with poorer adherence [12].

Several interventions have been designed to improve medication adherence. Some evidence suggests that multifaceted interventions targeting the patient, physician and structural aspects of care are more effective than single-component interventions [13–15]. However, it is considered that intervention strategies should be designed to address the specific factors associated with non-adherence to psychotropic medication for each psychiatric disorder [16, 17]. Moreover, interventions rarely target the adherence phase but recruit patients independently of their treatment journey that is, at the beginning (initiation), during implementation or while discontinuing (persistence) [18].

The aims of the present study are to identify, critically assess and synthesize the available scientific evidence on the effectiveness of interventions aimed at improving adherence (initiation and the implementation phase) to medication among adults with depressive disorders.

Material and methods

A systematic review and meta-analysis were performed according to the Cochrane Handbook [19] and reported in accordance to Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [20]. The protocol of the present review was registered in Prospero (CRD42017065723).

Information sources and search strategy

The following electronic databases were searched (January 2022): Medline (OVID interface), EMBASE (Elsevier interface), CENTRAL (The Cochrane Library interface), PsycINFO (EBSCO interface), SCI-EXPANDED (Web of Science interface) and SSCI (Web of Science interface). The search strategy was initially developed in Medline, using a combination of controlled vocabulary and free text terms and was then adapted for each of the other databases. Search terms included the following: depressive disorder, medication and adherence. Searches were limited to the English and Spanish languages and no date restriction was imposed. The full search strategy is available in Supplementary Material (see Supplementary Table 1). The reference lists of all included papers were also examined to identify possible additional studies meeting selection criteria.

Selection criteria

Studies were eligible for inclusion if they fulfilled the following criteria: 1) randomized controlled trials (RCTs) or non-randomized controlled trials (nRCTs), with allocation of both individuals and clusters; 2) any type of intervention (whether they were psychotherapeutic, educational interventions or other clinical intervention such as monitoring and adjustment of pharmacological treatment) aimed at increasing adherence (initiation and/or implementation phase) to anti-depressive medication administered to adults (18–65 years) with a diagnosis of depressive disorder. If a study addressed a heterogeneous group of patients, the study was included as long as the results for patients meeting the inclusion criteria were reported separately or they accounted for more than 80% of the target population. If the phase of adherence was not specified according to the taxonomy of Vrijens et al. [5], the reviewers determined the phase in which the evaluation was carried out based on the characteristics described in the study (adherence measurement method and moment); 3) usual care or alternative intervention as comparison group; 4) studies assessing initiation or implementation phase divided into three temporary spaces: short-term (closest to 3 months), medium-term (closest to 6 months) or long-term (closest to 12 months) adherence to prescribed medication; 5) studies published in English or Spanish. Exclusion criteria included: 1) studies examining patients with bipolar depression or schizoaffective disorder, and 2) studies with fewer than 10 study participants.

Study selection process

Two reviewers addressed eligibility independently and in duplicate. Firstly, the title and abstract of references identified in the electronic search were screened. Secondly, the full text of the studies that appeared to fulfil the pre-specified selection criteria was read and evaluated for inclusion. Disagreements between reviewers were resolved through discussion with the research team until consensus was reached.

Data collection process

A data extraction form was prepared by the authors, pilot tested on two studies and refined accordingly. One reviewer extracted the following data from the included studies: identification of the article (author, date of publication, country), study objective and methodology (design, context, duration), details of participants (selection criteria and demographics), interventions (type, modality and number of sessions), comparators and outcome (adherence definition, measurement method and value), and finally results. A second reviewer subsequently verified the extracted data. When any required information was missing or unclear in a paper, an effort was made to contact the corresponding author.

Risk of bias assessment

Two reviewers independently and in duplicate assessed risk of bias of included studies using the Cochrane Risk of Bias tools for RCT (RoB 2.0) [21] with the additional guidance for cluster-RCT [22] and nRCT (ROBINS-I) [23]. Discrepancies of judgments between the reviews were discussed by the research team until consensus was reached.

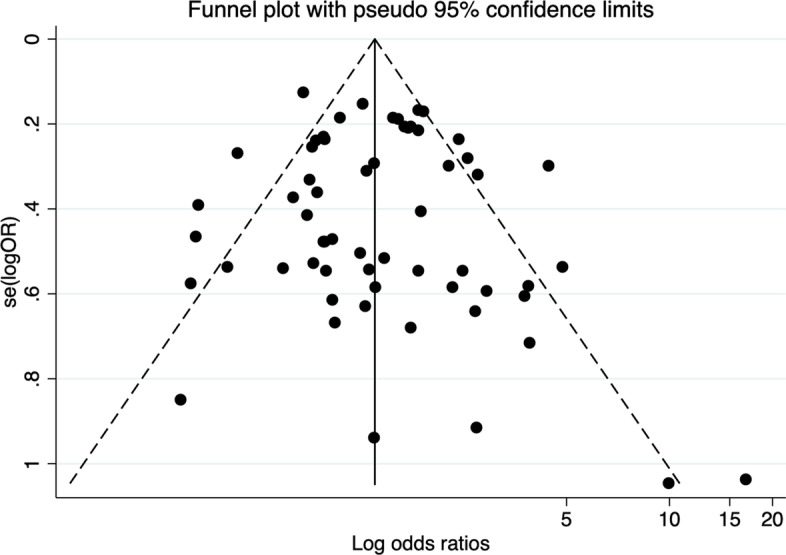

Assessment of publication bias

According to the recommendations of the Cochrane Collaboration [19], the presence of publication bias was assessed considering the size and sponsorship of the included studies, and by constructing a funnel plot and computing the Egger’s regression test using metafunnel and metabias commands in STATA version 14, respectively.

Analysis and synthesis of results

Meta-analyses and forest plots were performed for the adherence rate using the metan commands in STATA version 14. Effects of interventions were estimated as odd ratios (OR), with 95% confidence intervals (CI). Heterogeneity was assessed using the I2 statistic. When there was heterogeneity (I2 ≥ 25%), meta-analyses were performed using a random-effects model using the method of DerSimonian and Laird and taking the estimate of heterogeneity from the Mantel–Haenszel model. When there was neither clinical nor statistical heterogeneity, a fixed-effect model was used [24].

Several sources of heterogeneity relating to the characteristics of the study population and the interventions were anticipated. Predictive variables included age, gender, diagnoses, type of intervention, providers of the intervention (multidisciplinary vs. non-multidisciplinary team), modality of intervention (face-to-face vs. telephone, mails and/or website) and number of sessions. When reported in most studies, the effect of these study-level variables on the effectiveness closest to six months after intervention using subgroup analyses (diagnoses, type of intervention, providers of intervention and modality of intervention) and meta-regression techniques (age, gender, and number of sessions) were explored using the metareg command.

Sensitivity analyses were conducted to assess the stability of the effects of excluding certain types of studies (n-RCT).

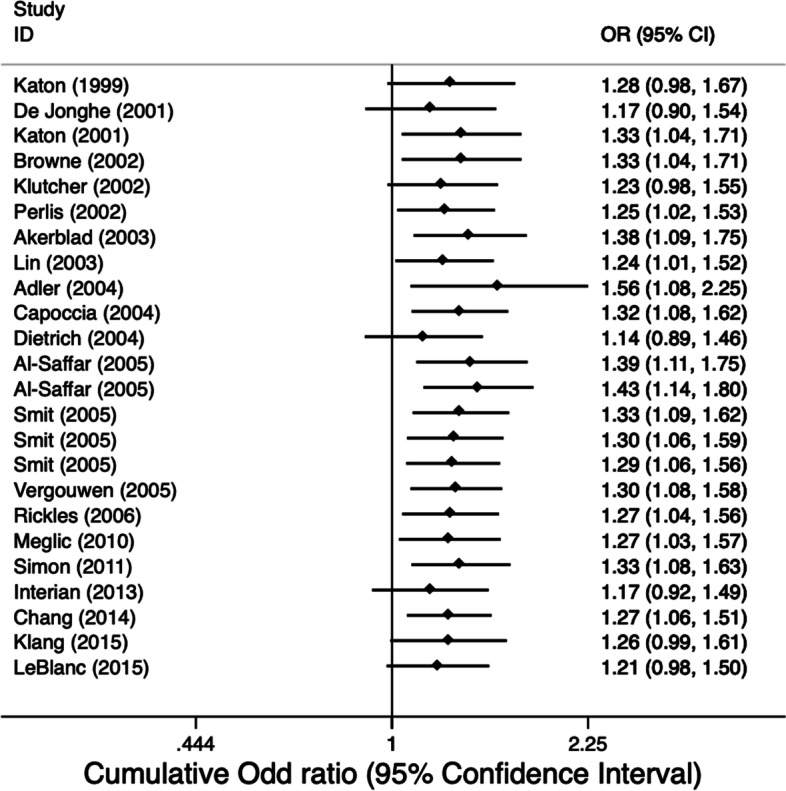

Cumulative meta-analysis was used to evaluate the sufficiency and stability over time of the effects of interventions aimed at increasing adherence to anti-depressive medication. Studies were sequentially added by year of publication to a random- effects model using the metacum user-written command.

Results

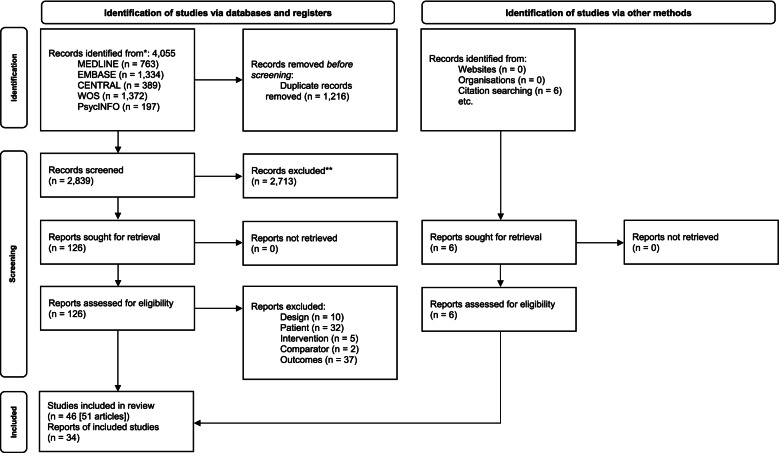

Out of a total of 2,839 initially identified references after eliminating duplicates, 40 studies were selected after full-text screening (Fig. 1). The manual search provided six additional studies, thus, 46 studies (published in 51 papers) were finally eligible for inclusion according to the pre-established selection criteria [25–75].

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of the selection process of studies

Characteristics of included studies

The 46 included trials were published in English between 1976 and 2021 (Table 1). Thirty-four are individual-RCT [25, 29–36, 40, 42–44, 46, 48–52, 55–61, 64–67, 70, 71, 74, 75], seven are cluster-RCT [26, 38, 41, 52, 53, 63, 72], four are individual-nRCT [28, 39, 45, 47], and one is cluster-nRCT [27]. The duration of reported follow-up ranged from 4 to 76 weeks (median 32 weeks). Seven studies specified incentive payments to patients [27, 29, 38, 39, 46, 55, 61] and 43 of them were carried out in outpatient [25, 26, 28–43, 46–74].

Table 1.

Main characteristics of included studies

| Study Country | Design | Follow-up (w) | Sample | Intervention | Outcome | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Size | Age (years) Mean, (SD) | Gender (female) (%) | Diagnoses | Inclusion Criteria | Type | Modality | Nº of sessions | Duration (m) | Staff qualification | Measure | Period (w) | |||||

| N | IG | CG | ||||||||||||||

| Adler et al., 2004 USA [25] | RCT | 16 | 533 | 268 | 265 | 42.3 (13.9) | 71.80 | MDD ± PDD |

≥ 18 years MDD and/or PDD (DSM-IV) English reading comprehension |

CCM | Face-to-face | 9 | 6 | Doctoral-level clinical pharmacist | Correct medication intakes |

Base 12 24 |

| Akerblad et al., 2003 Sweden [26] | Cluster RCT | 24 | 1,031 | 366 | 339 | 48.4 (14.36) | 28.10 | MDD |

≥ 18 years MDD (DSM-IV) SSRI prescription |

Education + support (programme RHYTHMS) | Letters + telephone | 5 letters + 4 telephone calls | 6 | GPs | Self-report | 24 |

| Serum levels | 24 | |||||||||||||||

| Appointments kept | 24 | |||||||||||||||

| Composite index | 24 | |||||||||||||||

| Aljumah and Hassali, 2015 Saudi Arabia [59] | RCT | 16 | 239 | 119 | 120 | 39.5 (NR) | 58.16 | MDD |

18–60 years MDD (DSM-IV) AD prescription |

SDM | Face-to-face | 2 | 6 | Pharmacist, psychiatrist and trained nurse | MMAS | 12 |

| Al-Saffar et al., 2008, 2005 Kuwait [37] | RCT | 20 | 300 | 100 | 100 | NR | 33.10 | MDD |

≥ 18 years Unipolar depression (ICD-10) TCA or SSRI prescription |

Counselling | Face-to-face + leaflet | 1 | NA | Trained pharmacist | Self-report + Pill count |

20 6 |

| 100 | Education + support | Leaflet | Correct medication intakes | 6 | ||||||||||||

| Browne et al., 2002 Canada [70] | RCT | 24 | 707 | 212 | 196 | 42.4 (NR) | 68.00 | PDD ± MDD |

18–75 years PDD ± MDD (DSM-IV) |

Interpersonal psychotherapy | Face-to-face | 10 | 6 | Masters-level therapist | Correct medication intakes | 24 |

| Capoccia et al., 2004 USA [71] | RCT | 52 | 74 | 41 | 33 | 38.7 (13.5) | 57.00 | Depressive episode |

≥ 18 years Depressive episode New AD prescription |

CCM | Telephone | 16 | 12 | Clinical pharmacist | Self-report |

12 24 36 52 |

| Chang et al., 2014 USA [72] | Cluster RCT | 24 | 915 | 503 | 411 | 46.03 (21.49) | 66.30 | MDD |

≥ 18 years MDD Newly prescribed AD Capable of self-management and understand English |

Monitoring and feedback to physicians about the patient's symptom severity | Telephone | 6 | 6 | GPs or internal medicine doctors | Correct medication intakes and adapted questions from MMAS |

12 24 |

| de Jonghe et al., 2001 Netherlands [74] | RCT | 24 | 167 | 83 | 84 | 34 (19–60) | 62.00 | PDD ± MDD |

18–60 years DSM-III criteria MDD with or without dysthymia 17-item HDRS ≥ 14 Written informed consent |

Short Psychodynamic Supportive Psychotherapy | Face-to-face | 16 | 6 | Psychiatrist ± fully trained psychotherapist | Pharmacotherapy dropout rates | 24 |

| Desplenter et al., 2013 Belgium [27] | Cluster nRCT | 52 | 99 | 41 | 58 | 46.10 (11.10) | 62.60 | MDD |

≥ 18 years; MDD ( DSM-IV-TR) AD prescription Dutch speaking Could be reached by telephone for follow-up |

Tailoring counselling or counselling intervention | Telephone | 1 | 1 day | Pharmacist | MMAS |

4 12 |

| Gervasoni et al., 2010 Switzerland [28] | nRCT | 2 | 131 | 81 | 50 | 36.24 (19–62) | 59.54 | Moderate or severe depressive episode |

18–65 years; Moderate or severe depressive episode without psychotic characteristics (ICD-10) MADRS scale ≥ 25 |

Monitoring and motivational support | Telephone | 3 | 2 weeks | Psychiatrist and research nurse | AD plasma level | 2 |

| Guo et al., 2015 China [65] | RCT | 24 | 81 | 44 | 37 | 41.10 (12.10) | 64.16 | Moderate to severe MDD |

Outpatients 18–65 years Non-psychotic MDD ( DSM-IV) HAM-D ≥ 17 |

Measurement-based care | Face-to-face | NA | NA | Psychiatrist and raters | NR | 12 |

| Hammonds et al., 2015 USA [29] | RCT | 4 | 57 | 30 | 27 | 20.6 (4.3) | 85.96 | MDD (89,4%) |

18–30 years AD prescription English speaking Patients who had an Android or iPhone smartphone |

Medication reminder app | Smartphone | Until study termination | 1 | Trained research assistant | Correct medication intakes | 4 |

| Interian et al., 2013 USA [30] | RCT | 20 | 50 | 26 | 24 | 40.6 (16.90)a | 76.00 | MDD or PDD |

≥ 18 years MDD or PDD (DSM-IV) AD prescription |

Motivational Enhancement Therapy | Face-to-face | 3 | 5 | Clinical psychologist and psychology doctoral students | Pill Count |

5 20 |

| John et al., 2016 India [31] | RCT | 6 | 39 | 17 | 22 | 34 (21–46) | 61.53 | Mild depression, moderate depression or PDD |

18–60 years Depression or PDD (ICD-10) AD monotherapy 12–23 HAM-D score |

Educational | Face-to-face | NR | NR | Clinicians | Correct medication intakes | 6 |

| Katon et al., 2002 USA [32] | RCT | 112 | 171 | NR | NR | 46.95 (18–80) | 74.55 | MDD |

18–80 years; new AD prescription ≥ 11 SCL-20 and > 4 DSM-IV or < 4 DSMIV and ≥ 11,5 SCL-20 |

CCM | Face-to-face | 0–7 | 28 | GPs and psychiatrist | Adequate prescription refills |

24 48 72 96 112 |

| Katon et al., 2001 USA [33] | RCT | 52 | 386 | 194 | 192 | 46.0 (17.85)a | 73.70 | MDD or PDD |

18–80 years MDD or PDD AD prescription |

CCM | Mail + website | 4 mailings + 3 telephone calls | 12 | GPs, psychologists, nurse practitioners and social worker | Automated data on refill |

12 24 36 52 |

| Katon et al., 1999 USA [34] | RCT | 24 | 228 | 114 | 114 | 46.9 (19.38)a | 74.50 | MDD or PDD or anxiety |

18–80 years MDD or PDD ≥ 4 DSM- III-R major depressive symptoms + SCL-20 score ≥ 1.0 or < 4 major depressive symptoms + SCL-20 score ≥ 1.5 |

CCM | Book + videotape + face-to-face | ≤ 7 | 6 | GPs and psychiatrist | Automated data on refill |

4 12 24 |

| Katon et al., 1996 USA [35] | RCT | 12 | 153 | 31 | 34 | 44.4 (26.88)a | 73.86 | MDD |

18–75 years Definite or probable MDD or PDD SCL-20 score ≥ 0.75 Willingness to take AD |

CCM | Book + videotape + face-to-face | 4–6 sessions + 4 telephone calls | 6 | GPs and psychologist | Automated data on refill |

4 12 |

| Katon et al., 1995 USA [36] | RCT | 12 | 217 | 108 | 109 | 35.9 (28.83)a | 77.60 | MDD or PDD |

18–780 years Definite or probable MDD or PDD SCL-20 score ≥ 0.75 Willingness to take AD |

CCM | Book + videotape + face-to-face | 4 | 1 | GPs, therapists and psychiatrists | Automated data on refill |

4 12 |

| Keeley et al., 2014 USA [38] | Cluster RCT | NR | 175 | 85 | 86 | 33.40 (38–60) | 38.05 | Depression |

≥ 18 years newly diagnosed English speakers Consenting patients Positive Patient Health Questionnaire ≥ 10 PHQ-9 score |

Motivational Interviewing | Face-to-face | 4 | 13 | GPs | NR | |

| Klang et al., 2015 Israel [39] | nRCT | 24 | NR | 173 | 12,746 | 50.5 (25.96)a | 68.05 | Depressive episode |

≥ 18 years Depressive episode (DSM-IV) Escitalopram prescription |

Pharmacist adherence support | Face-to-face | 6 | NR | Community Pharmacist | Correct medication intakes |

4 24 |

| Kutcher et al., 2002 Canada [40] | RCT | 29 | 269 | 131 | 138 | NR | NR | MDD |

MDD (DSM-IV) Contraceptive method in females of childbearing years |

Education + support (programme RHYTHMS) | Letters + telephone | 5 letters + 4 telephone calls | 6 | Research nurses | Pill count | NR |

| LeBlanc et al., 2015 USA [41] | Cluster RCT | 24 | 297 | 138 | 139 | 43.5 (43.54)a | 66.92 | Moderate to severe depression |

≥ 18 years Moderate/Severe depression PHQ-9 score ≥ 10 |

SDM | Face-to-face | 2 | 6 | Clinicians | Automated data on refill | 24 |

| Lin et al., 2003 USA [42] | RCT | 52 | 386 | 194 | 192 | 46.0 (17.85)a | 26.40 | High risk for recurrent depression |

18–80 years AD prescription Improvement of depressive episode (≥ 4 DSM- III-R major depressive symptoms or 4 major depressive symptoms + SCL-20 score ≥ 1.5) High risk of relapse (≥ 3 lifetime depressive episodes or a history of dysthymia) |

CBT + motivational interviewing + education | Face-to-face + telephone | 2 sessions + 3 telephone calls | 12 | Psychologist, psychiatric nurse and social worker | % of days covered | 52 |

| Lin et al., 1999 USA [43] | RCT | 19 | 156 | 63 | 53 | 44.10 (13.60) | 81.00 | MDD |

18–80 years AD prescription SCL-20 score ≥ 0.75 |

CCM | Face-to-face | 4 + 2 optional | 4.75 | GPs and psychologists | Self-reported and adequate pharmacotherapy according to pharmacy data | 19 |

| Mantani et al., 2017 Japan [44] | RCT | 17 | 164 | 81 | 83 | 40.90 (NR) | 53.05 | MDD ± anxiety | 25–59 years; MDD without psychotic features (DSM-5 and PRIME-MD); antidepressant-resistant, BDI-II ≥ 10 for ≥ 4 weeks; AD in monotherapy (not antipsychotics or mood stabilizers); smartphones users; being an outpatient; no plan to transfer within 4 months | Smartphone CBT | Smartphone | 8 | 2.25 | Psychiatrists | Discontinuation of protocol antidepressant treatment by week 9 | 17 |

| Marasine et al., 2020 Nepal [69] | RCT | 16 | 196 | 98 | 98 | NR | 142 (72,45) | Depression |

18–65 year Diagnosed with depression AD prescription |

Education + support | Face-to-face + leaflet | 1 | NA | Clinical pharmacist | MMAS | 16 |

| Meglic et al., 2010 Slovenia [45] | nRCT | 24 | 19 | 10 | 9 | 35.71 (12.11) | 86.00 | Depression or mixed anxiety and depression disorder |

ICD10 group F32 or F41.2 first time or after a remission > 6 months Newly AD Internet and mobile phone BDI-II ≥ 14 |

CCM | Telephone + website | NR | 6 | GPs and psychologist | Correct medication intakes | 24 |

| Mundt et al., 2001 USA [46] | RCT | 30 | 246 | 124 | 122 | 40.5 (16.57)a | 82.83 | MDD |

MDD (DSM-IV) Symptom duration of ≥ 1 month AD prescription Hamilton Depression score ≥ 18 |

Education + support (programme RHYTHMS) | Mail + telephone | 1mailing + telephone calls | 7 | NR | Medication days | 30 |

| Myers and Calvert, 1984 UK [49] | RCT | NR | 120 | 40 | 40 | 41.7 (29.79) | 74.20 | Depression |

Depression, reactive or endogenous Dothiepin prescription |

Education | Leaflet | 1 | NA | NA | Correct medication intakes |

3 6 |

| Myers and Calvert, 1976 UK [47] | nRCT | NR | 89 | 46 | 43 | 47.8 NR | 66.30 | Depression |

21–77 years ≥ Attack of primary depression, reactive or endogenous Dothiepin prescription |

Education | Leaflet | 1 | NA | NA | Correct medication intakes | NR |

| Nwokeji et al., 2012 USA [50] | RCT | 52 | 166 | 101 | 65 | 47.8 (12.01)a | 88.00 | MDD |

MDD AD prescription |

Enhanced care | Mail + telephone | NR | 12 | Nurses and social worker | % of days covered | 52 |

| Perahia et al., 2008 11 European countries [51] | RCT | 4 | 962 | 485 | 477 | 46.2 (18.46)a | 64.20 | MDD |

≥ 18 years MDD (DSM-IV) Hamilton Depression score ≥ 15 Access to a telephone |

Education | Telephone | 3 | 12 | GPs or psychiatrists | Pill count |

2 6 12 |

| Perlis et al., 2002 USA [75] | RCT | 28 | 132 | 66 | 66 | 39.9 (14.57)a | 54.60 | MDD |

18–65 years MDD (DSM-III-R) Hamilton Depression score ≥ 16 History of ≥ 3 major depressive episodes, diagnosis of current episode as chronic; history of poor interepisode recovery; or both MDD and PDD |

CBT | Face-to-face | 19 | 28 | Clinicians and psychologists | Correct medication intakes | 28 |

| Pradeep et al., 2014 India [52] | Cluster RCT | 24 | 260 | 122 | 138 | NR | 100.00 | MDD + PD, social phobia or GAD |

Women ≥ 18 years MDD (DSM-IV-TR) |

Education + support | Face-to-face | 2 | 4 | Health workers | Duration of compliance (days) | 28 |

| Richards et al., 2016 UK [53] | Cluster RCT | 52 | 581 | 276 | 305 | NR | 71.94 | Depressive episode |

≥ 18 years Depressive episode (ICD-10) |

CCM | Face-to-face | 6–12 | ≥ 3 | Trained care managers, GPs and mental health worker | Self-report |

16 52 |

| Rickles et al., 2006, 2005 USA [54, 55] | RCT | 24 | 63 | 31 | 32 | 37.6 (17.15)a | 84.10 | Depressive symptoms |

≥ 18 years BDI-II ≥ 16 Willingness to take AD |

Education + monitoring | Telephone | 3 | 3 | Trained pharmacist | Medication intakes |

12 24 |

| Salkovskis et al., 2006 UK [56] | RCT | 26 | 77 | 39 | 38 | 40.5 (NR) | 81.82 | Depressive disorder |

17–70 year AD prescription |

Self-help programme | Telephone | NR | 6.5 | GPs | Length of time medication | 26 |

| Simon et al., 2011 USA [58] | RCT | 24 | 197 | 104 | 93 | 45.5 (NR) | 72.12 | Depressive disorder |

≥ 18 years New AD No AD ≥ 270 days before Online messaging |

Support | Telephone | 4 | 4 | GPs, psychiatrist and nurse | Using antidepressant for over 90 days | 24 |

| Simon et al., 2006 USA [57] | RCT | 24 | 207 | 103 | 104 | 43.0 (21.21)a | 65.00 | MDD or PDD |

≥ 18 years MDD or PDD New AD prescription |

Support | Telephone | 3 | 3 | Nurses | Automated data on refill | 12 |

| Smit et al., 2005 Netherlands [60] | RCT | 52 | 267 | 112 | 72 | 42.8 (19.39)a | 63.20 | MDD |

18–70 years MDD (DSM-IV) |

Education | Face-to-face + telephone | 3 | 3 | GPs | Correct medication intakes |

12 24 36 52 |

| 39 |

Education + psychiatric consultation |

4 | 3 | GPs and psychiatrist | ||||||||||||

| 44 |

Education + CBT |

15 | 3 | GPs and clinical psychologist | ||||||||||||

| Vannachavee, 2016 Thailand [61] | RCT | 6 | 60 | 30 | 30 | 45.3 (22.70)a | 84.00 | MDD |

≥ 18 years MDD (DSM-IV-TR) A new AD prescription Thai speaking |

Educational, motivational and cognitive intervention | Face-to-face | 4 | 1,5 | Candidate master degree researcher and nurses | Self-Medication Intake Record Form | 6 |

| Vergouwen et al., 2009, 2005 Netherlands [62, 63] | Cluster RCT | 26 | 211 | 101 | 110 | 43.0 (20.29)a | 67.40 | MDD |

≥ 18 years MDD (DSM-IV) |

Education + support + active participation in treatment process with discussion on AD | Mail + face-to-face | 7 visits | 6,5 | GPs | Self-report + pill counts |

10 26 |

| Wiles et al., 2014, 2013 UK [65, 66] | RCT | 52 | 469 | 234 | 235 | 49.6 (11.7) | 72.30 | MDD + PD, social phobia or GAD |

18–75 years AD prescription Patients’ adherence to the prescribed AD BDI-II ≥ 14 |

CBT | Face-to-face | 12–18 | 12 | Trained CBT therapist | 4-item MMAS (80%) | 48 |

| Wiles et al., 2008 UK [64] | RCT | 16 | 25 | 14 | 11 | 45.3 (NR) | 84 |

18–65 years Depressive disorder (ICD-10) AD ≥ 15 BDI-II Positive Morisky-Green-Levine test |

CBT | Face-to-face | 12–20 | 4 | GPs, psychiatrist and psychologist | 4-item MMAS (80%) | 16 | |

| Yusuf et al., 2021 [68] | RCT | 24 | 120 | 60 | 60 | NR | 81 (890.20) | MDD |

≥ 18 years MDD (ICD-10) AD prescription |

Education + support | Face-to-face + telephone | 1 sessions + 6 telephone calls | 6 | Pharmacist | MMAS | 24 |

aOwn estimation, AD Antidepressant, AG Agoraphobia, Base Baseline, CBT Cognitive behavioural therapy, CCM Collaborative care model, CG Control group, Cluster RCT Cluster randomized controlled trials, GAD Generalized anxiety disorder, GP General practitioner, IG Intervention group, m months, MDD Major depressive disorder, MMAS Morisky Medication Adherence Scale, N total sample, NA Not applied, NR Not reported, nRCT non-randomized controlled, PC Panic disorder, PDD Persistent depressive disorder or Dysthymic Disorder, Reminder APP Medication reminder app, SDM Share decision making, RCT Randomized controlled trials, w weeks

Study size ranged from 19 to 12,919 participants, with a mean average of 526 per study. In the 46 studies, a total of 31,832 participants were recruited and 24,324 were finally assigned to intervention (RCT: 7,608; cluster-RCT: 3,470; nRCT: 13,147; cluster-nRCT: 99). The mean age of participants was 42.40 years (SD: 15.66) and 65.05% of them were female. Approximately 10% were lost in the follow-up, thus 2,404 patients completed the studies.

Most of the studies enrolled patients with depression at different levels of severity. However, five studies required a combination of major depressive disorder with panic disorder, social phobia or generalized anxiety disorder, or anxiety [34, 44, 45, 52, 65, 66].

All the studies assessed individual interventions and used usual care as comparator. In general, the number of sessions or contacts of the interventions ranged from 1 to 20. A total of 10 studies assessed the effects of the Collaborative Care Model (CCM) consisting of the following four elements of collaborative care: 1) a multi-professional approach to patient care; 2) a structured management plan, included either or both pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions; 3) scheduled patient follow-ups to provide specific interventions, facilitate treatment adherence, or monitor symptoms or adverse effects; and 4) enhanced inter-professional communication. Five studies assessed the effects of interventions with only an educational focus while eight studies evaluated the effects of education and support, three of them used the RHYTHMS programme, a patient education programme which mails information directly to patients being treated with antidepressant medicines in a time-phased manner. Education was also added to Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT), CBT and motivational interview, coaching, monitoring and psychiatric consultation. Psychotherapy was another type of included intervention; in particular, six studies used CBT, one study included short psychodynamic supportive psychotherapy and one study included interpersonal psychotherapy. Other types of interventions were shared decision-making, support, counselling, the use of medication reminder applications for mobile phones, Enhanced Care and Treatment Initiation and Participation, an intervention aimed at modifying factors such as psychological barriers, concerns about treatment, fear of antidepressants and misconceptions of depression treatment.

Intervention modalities included face-to-face meetings alone (18 studies) or in combination with telephone conversations (3 studies), leaflets (2 study), videotapes (2 studies), mails (1 study) or website. Eight studies used telephone-conversations and two studies used the same intervention in combination with mails and one study combined the same intervention with letters. Moreover, leaflets were used in three of the studies, while consultation of websites was included in two studies. Another intervention modality was the use of a smartphone (2 studies).

The intervention providers varied among studies: multidisciplinary teams (16 studies), primary care professionals -general practitioners, clinicians or internal medicine doctors- (8 studies), pharmacists (8 studies); psychiatrists, psychologists or therapists (5 studies), nurses (2 studies), research assistant (1 study), and health worker (1 study). In the remaining studies, the providers were required to deliver intervention (2 studies) or not reported (1 study).

All patients in the included studies were in the implementation phase of the adherence. Twenty-five studies provided short-term (ranged from 4 to 16 weeks), 22 studies provided mid-term (ranged from 20 to 36 weeks), and seven studies provided long-term (ranged from 48 to 76 weeks) outcomes. Both self-report and direct measures were used for assessing adherence. Approaches for subjectively assessed adherence included questionnaires, diaries and interviews, and approaches for objectively assessed adherence included electronic measures, pill count and plasma drug concentration.

Risk of bias in the included studies

Out of the 41 RCTs identified, three were classified as having low risk of bias in all RoB 2.0 domains [34, 57, 70] (Table 2). In the remaining RCTs, the most common methodological concerns involved bias arising from the randomization generation and allocation concealment process (3 RCTs at high RoB) and bias in measurement of the outcome (6 at high RoB).

Table 2.

Risk of bias of included RCTs

| Cluster-RCTs | |||||||

| Study | Domains | ||||||

| Randomization process | Identification and recruitment of participants | Effect of assignment to intervention | Missing outcome data | Measurement of the outcome | Selection of the reported result | ||

| Akerblad 2003 [26] | High | Low | Low | Low | Some concerns | Low | |

| Chang 2014 [72] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Some concerns | Low | |

| Keeley 2014 [38] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Some concerns | Some concerns | |

| LeBlanc 2015 [41] | Unclear | Low | Some concerns | Low | Some concerns | Low | |

| Pradeep 2014 [52] | Some concerns | Low | Low | Some concerns | Low | Low | |

| Richards 2016 [53] | Low | Low | Low | Low | High | Low | |

| Vergouwen 2009, 2005 [62, 63] | Low | Low | Low | Some concerns | Some concerns | Low | |

| Individually RCTs | |||||||

| Study | Domains | ||||||

| Randomization process | Effect of assignment to intervention | Missing outcome data | Measurement of the outcome | Selection of the reported result | |||

| Adler 2004 [25] | Low | Low | Low | High | Low | ||

| Aljumah & Hassali, 2015 [59] | Low | Some concerns | High | Low | Low | ||

| Al-Saffar 2008, 2005 [37, 48] | Low | Low | Some concerns | Some concerns | Low | ||

| Browne 2002 [70] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | ||

| Capoccia 2004 [71] | Some concerns | Low | Low | Some concerns | Low | ||

| De Jonghe 2001 [74] | Low | Some concerns | Low | Some concerns | Some concerns | ||

| Guo 2015 [67] | Some concerns | Low | Low | Some concerns | Some concerns | ||

| Hammonds 2015 [29] | Some concerns | Some concerns | Some concerns | Low | High | ||

| Interian 2013 [30] | Some concerns | Low | Low | Low | Low | ||

| John 2016 [31] | Low | Low | Some concerns | High | Some concerns | ||

| Katon 2002 [32] | Some concerns | Low | Some concerns | Some concerns | Some concerns | ||

| Katon 2001 [33] | Some concerns | Some concerns | Low | Some concerns | Low | ||

| Katon 1999 [34] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | ||

| Katon 1996 [35] | Some concerns | Some concerns | Low | Some concerns | Low | ||

| Katon 1995 [36] | Low | Low | Low | Some concerns | Low | ||

| Kutcher 2002 [40] | Low | Some concerns | High | Some concerns | Low | ||

| Perlis 2002 [75] | Some concerns | Low | Low | Some concerns | Low | ||

| Lin 2003 [42] | Some concerns | Low | Low | Low | Low | ||

| Lin 1999 [43] | Some concerns | Low | Some concerns | High | Low | ||

| Mantani 2017 [44] | Low | Low | Low | Some concerns | Low | ||

| Mundt 2001 [46] | Some concerns | Some concerns | Low | Some concerns | Low | ||

| Myers & Calvert, 1984 [49] | Some concerns | Low | Low | Some concerns | Low | ||

| Nwokeji 2012 [50] | High | Low | Low | Some concerns | Low | ||

| Perahia 2008 [51] | Some concerns | Low | Low | High | Low | ||

| Salkovskis 2006 [56] | Some concerns | Low | Some concerns | High | Some concerns | ||

| Rickles 2006, 2005 [54, 55] | Low | Low | High | Low | Low | ||

| Simon 2006 [57] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | ||

| Simon 2011 [58] | Low | Low | Low | Some concerns | Low | ||

| Smit 2005 [60] | High | Some concerns | Low | Low | Low | ||

| Vannachavee 2016 [61] | Some concerns | Low | Some concerns | Low | Low | ||

| Wiles 2014, 2013 [65, 66] | Low | Low | Some concerns | Some concerns | Low | ||

| Wiles 2008 [64] | Low | Low | Low | Some concerns | Low | ||

| Marasine, 2020 [69] | Low | Some concerns | Some concerns | Low | Low | ||

| Yusuf, 2021 [68] | Low | Some concerns | Some concerns | Low | Low | ||

High, High risk of bias, Low Low risk of bias, Unclear Unclear risk of bias

RCTs Randomized controlled trials

For the five n-RTCs identified, risk of bias was generally low-to-moderate across all of them, all presenting risk of bias in at least three domains (Table 3).

Table 3.

Risk of bias of included nRCTs

| Study | Domains | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bias due to confounding | Bias in selection of participants | Bias in classification of interventions | Bias due to deviations from intended interventions | Bias due to missing data | Bias in measurement of outcomes | Bias in selection of the reported result | |

| Desplenter et al., 2013 [27] | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | NI | Moderate | Moderate |

| Gervasoni et al., 2010 [28] | Serious | Low | Moderate | Low | NI | Low | Low |

| Myers and Calvert, 1976 [47] | NI | NI | Low | Low | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate |

| Klang et al., 2015 [39] | Moderate | NI | Low | Low | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate |

| Meglic et al., 2010 [45] | Moderate | Low | Moderate | Low | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate |

Serious Serious risk of bias, Moderate Moderate risk of bias, Low Low risk of bias

NI No information, nRCTs non-randomized controlled trials

Publication bias

No evidence of publication bias was found according to the funnel plot of the observed effect (Fig. 2) and the Egger’s regression test (P = 0.50).

Fig. 2.

Funnel plot – Potential publication bias

Synthesis of results

Results on adherence of the selected studies are available in the Supplementary Material (see Supplementary Table 2). Results of all meta-analyses and subgroup analysis are also available in the Supplementary Material (see Supplementary Tables 3 and 4).

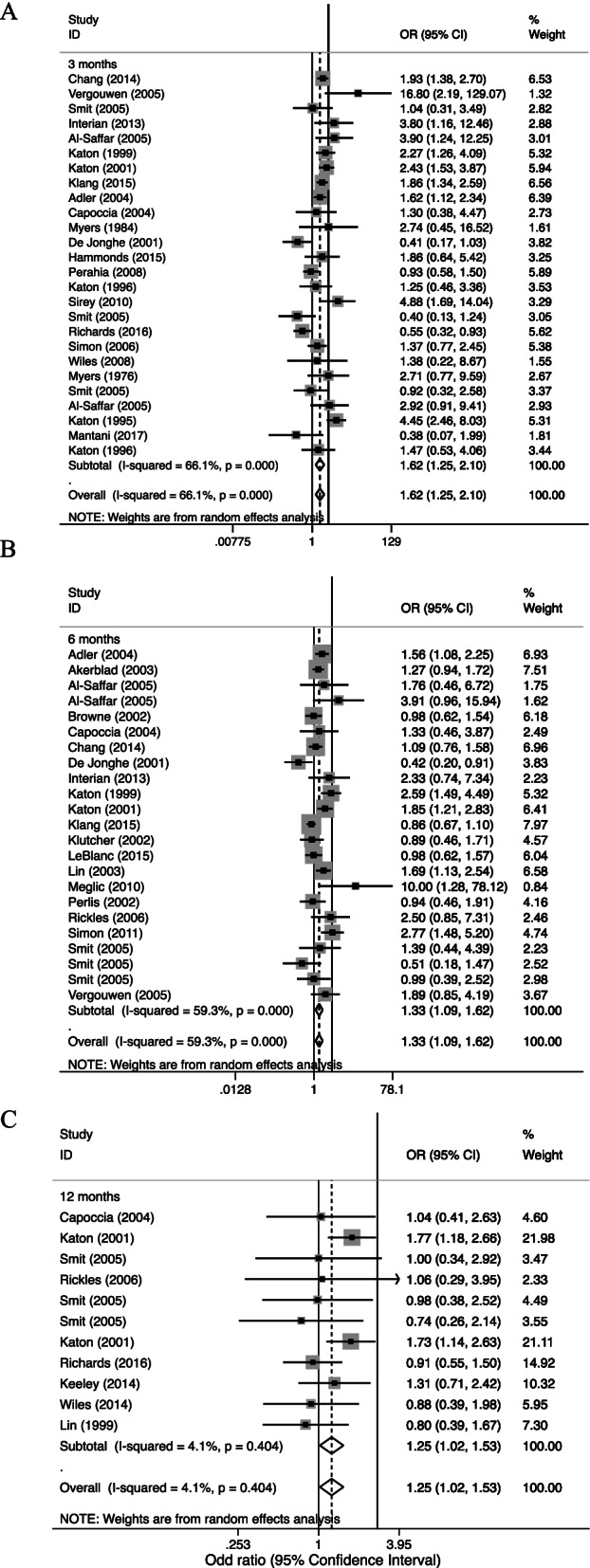

Interventions aimed at improving the implementation phase of medication adherence in adults with depressive disorders had a positive effect on adherence outcome at 6 months after intervention compared with usual care (Odd ratio [OR] 1.33, 95% confidence interval [95% CI]: 1.09 to 1.62; p < 0.01) (Fig. 3). As anticipated, there was a moderate level of heterogeneity between studies (I2 = 59.30%).

Fig. 3.

Forest plots for effect of intervention on adherence rate. Note: A at 6 months; B at 6 months; C at 12 months

In the patients of these studies, the overall trend for clinical improvement was observed to emerge at 3 months after intervention (OR 1.62, 95% CI: 1.25 to 2.10; p < 0.01) but the effect was attenuated at 12 months after intervention (OR 1.25, 95% CI: 1.02 to 1.53; I2 = 4.10%; p = 0.40) (Fig. 3). Substantial between-study heterogeneity was also found at 3 months (I2 = 66.10%).

Causes of heterogeneity

Sufficient study-level data were available from 35 of the studies for the effect of the predictor variables to be entered into a subgroup or meta-regression analysis. Results of subgroup analysis and meta-regression are available in the Supplementary Material (see Supplementary Tables 3 and 4, respectively).

Diagnosis

Interventions aimed at improving adherence to medication when addressed to adults with depression at different levels of severity were associated with a significantly increased effect size (OR Major depressive disorder or dysthymic disorder and anxiety studies 2.77, 95% CI: 1.74 to 4.42; p < 0.01; OR High risk for recurrent depression 1.69, 95% CI: 1.13 to 2.54; p = 0.01; OR Major depressive disorder or dysthymic disorder 1.32, 95% CI: 1.08 to 1.61; p < 0.01; I2 = 35.80%). However, pooled effect sizes of studies on patients with depressive symptoms (OR, 2.50, 95% CI: 0.86 to 7.31; p = 0.29; I2 = NA%), depressive episode (OR, 0.88, 95% CI: 0.69 to 1.12; p = 0.29; I2 = 0%), and major depressive disorder with or without dysthymic disorder (OR, 0.68, 95% CI: 0.30 to 1.50; p = 0.29; I2 = 70.70%) were not statistically significant.

Type of intervention

In the case of CCM interventions, the pooled result showed a significant increase in adherence (OR 1.88, 95% CI: 1.40 to 2.54; p < 0.27; I2 = 23.00%) compared to the control group. However, statistically significant differences were not found for other specific forms of intervention (see Supplementary Table 3).

Providers of the intervention

A multi-professional approach to patient care involving at least one primary care provider and another health professional (e.g., nurse, psychologist, psychiatrist or pharmacist) was associated with an increased effect size (OR 1.73, 95% CI: 1.21 to 2.46; I2 = 53.70%). A non-multidisciplinary approach was not statistically significant (OR 1.15, 95% CI: 0.94 to 1.40; I2 = 42.90%).

Modality of intervention delivery

Effect sizes did not significantly differ by the modality of intervention delivery used (see Supplementary Table 3).

Other sources of heterogeneity

The number of intervention sessions was related to adherence (β, -0.08; 95% CI: -0.14 to -0.02). However, none of the other sources of heterogeneity investigated (age and gender of participants) had an effect.

Cumulative meta-analysis of outcome at 6 months

When we assess interventions aimed at improving adherence to medication over time (Fig. 4), it is unclear whether earlier trials meeting the inclusion criteria demonstrated a high degree of heterogeneity or a high percentage of negative results. There is a sufficient body of evidence to demonstrate a reliable, consistent and statistically significant benefit of interventions aimed at improving adherence to medication over usual care. In general, the overall effect size has remained relatively stable within an effect size between OR 1.17 and 1.56.

Fig. 4.

Cumulative meta-analysis of studies ordered by year of publication

Discussion

Our findings support and confirm the notion that interventions aimed at improving adherence to medication among adults with depressive disorders are effective in improving outcomes in implementation phase of adherence in the studied patients, when these were analysed at 3 and 6 months after the intervention. The evidence, when given using cumulative meta-analysis, shows that further trials are unlikely to overturn this positive result. However, it is possible to appreciate a small decline in effect size over time.

The evidence shows that collaborative care is effective in improving adherence. In this respect, a multi-professional approach to patient care was more effective than primary or mental healthcare teams. This finding supports the idea that collaborative care might not only be clinically effective for symptom management in adults with depressive disorders [76, 77], but could also have a major effect on improving adherence to treatment [7]. This is in line with previous literature and suggests that multifaceted interventions targeting all dimensions that affect medication adherence problems, i.e., the patient, the healthcare provider and the health care delivery system, are more effective than single-component interventions to improve medication adherence [14, 15]. In fact, this positive effect of multicomponent interventions has also been observed in other psychiatric disorders [16, 17] and non-psychiatric pathologies [78]. Moreover, the number of intervention sessions was negatively related to adherence. A similar result has been observed in other studies of behaviour changes [79, 80]. Although the optimal number of intervention sessions is not clear, this a priori surprising result would support the usefulness of brief interventions or therapies to improve treatment adherence, however, it needs to be confirmed with more research.

Nevertheless, subgroup analyses indicate how other characteristics of the intervention may not help to enhance adherence. The modality of intervention and the provider profile were unrelated to effect size. Effect sizes also did not differ significantly by the modality of intervention delivery used (face-to-face vs. telephone, mails and/or website). Computer support systems, mobile technologies, web-based e-mail or telephone-based assistance can be used for improving adherence to medication [81, 82]. In this regard, these interventions may be available across different geographic areas and in different clinical settings [83].

Generally, it might be expected that patients with severe symptoms would have different treatment and support needs, and thus may profit from this type of interventions compared to patients with moderate or mild symptoms. However, the findings here do not show a clearly relationship between the severity of disease and adherence. Several interventions are effective in improving adherence outcomes among patients diagnosed with depression and anxiety at the same time. Although effectiveness is also demonstrated in the cases of patients at high risk of recurrent depression and in patients with major depressive disorder or dysthymic disorder, the results do not present such high values. Other patient characteristics such as age or gender were unconnected to adherence outcome.

The main limitation of the present review is the methodological differences between studies, mainly the diversity of both intervention procedures and severity and diagnosis of depressive disorder of participants, as well as the absence of an adequate psychopathological evaluation of the patients included in the studies. Interventions aimed at improving medication adherence among adults with emotional disorders have been designed with varying levels of intensity. Consequently, the review here found significant between-study heterogeneity. Subgroup and meta-regression analyses have been used to explore some of the issues related to the diversity of interventions (i.e.: type of intervention and providers) and patients’ characteristics (i.e.: severity of depression) that may influence the adherence result. Although, up to 770 determinants of adherence have been described in previous literature [84], only a few could be explored in this review. Although the prescribed antidepressant treatment has been shown to be a predictor of adherence [85, 86], most included studies did not report the specific antidepressant medicines that patients receive (Table 1). Moreover, there were studies that did not specify the patient´s phase of adherence, some of them because they were published before the publication of Vrijens et al. taxonomy [5]. However, after the evaluation based on the characteristics of the studies, we have determined that all patients in the included studies were in the implementation phase of the adherence. Finally, the exclusive reliance on English-language studies may not represent all the evidence. For this reason, we have also considered studies published in Spanish, however, limiting the systematic review to studies written in English and Spanish, which could introduce a language bias.

Despite all these limitations, our comprehensive systematic review provides an updated assessment of the effectiveness of different types of interventions aimed at improving medication adherence among adults with emotional disorders, supported by meta-analyses, using cumulative meta-analysis, assessing risk of bias of included studies, exploring important sources of heterogeneity and following rigorous and transparent methods compared to the previous systematic review [15].

The systematic review reported here shows that interventions aimed at improving short and medium-term adherence to medication among adults with depressive disorders are effective. Compared to short and medium-term adherence outcome, the available evidence on the effectiveness of long-term adherence is insufficient and supports the need for further research efforts.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Supplementary Table 1. Search strategy.

Additional file 2: Supplementary Table 2. Results on adherence in the included studies.

Additional file 3: Supplementary Table 3. Meta-Analyses of Adherence outcome and Subgroup Analyses.

Additional file 4: Supplementary Table 4. Meta-Regression Analyses (6 months).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Leticia Rodríguez for her guidance in developing the search strategy.

Authors’ contributions

BGdL and TP-S participated in the conceptualization, methodology, writing and the editing. CR-A, PS-P, DB-Q, MT-M participated in the supervision, drafting and revision. MT-M also participated in the project administration. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. BGdL and TP-S contributed equally.

Funding

This study has been funded by Instituto de Salud Carlos III through the project "PI18/00767" (Co-funded by European Regional Development Fund/European Social Fund "A way to make Europe"/"Investing in your future").

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Beatriz González de León and Tasmania del Pino-Sedeño are contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.GBD 2017 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 Diseases and Injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease Study 2017. Lancet. 2018;392:1789–858. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32279-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kazdin AE, Rabbitt SM. Novel models for delivering mental health services and reducing the burdens of mental illness. Clin Psychol Sci. 2013;1:170–191. doi: 10.1177/2167702612463566. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization. The global burden of mental disorders and the need for a comprehensive, coordinated response from health and social sectors at the country level. 2011; December:1–6. http://www.who.int/mental_health/WHA65.4_resolution.pdf.

- 4.World Health Organization. Depression. 2021. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/depression.

- 5.Vrijens B, De Geest S, Hughes DA, Przemyslaw K, Demonceau J, Ruppar T, et al. A new taxonomy for describing and defining adherence to medications. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2012;73:691–705. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2012.04167.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de las Cuevas C, Peñate W, de GarcíaCecilia JM, de Leon J. Predictive validity of the Sidorkiewicz instrument in Spanish: Assessing individual drug adherence in psychiatric patients. Int J Clin Heal Psychol. 2018;18:133–42. doi: 10.1016/j.ijchp.2017.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ho SC, Chong HY, Chaiyakunapruk N, Tangiisuran B, Jacob SA. Clinical and economic impact of non-adherence to antidepressants in major depressive disorder: a systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2016;193:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fischer MA, Stedman MR, Lii J, Vogeli C, Shrank WH, Brookhart MA, et al. Primary medication non-adherence: analysis of 195,930 electronic prescriptions. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25:284–290. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1253-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Simon GE, Johnson E, Stewart C, Rossom RC, Beck A, Coleman KJ, et al. Does patient adherence to antidepressant medication actually vary between physicians? J Clin Psychiatry. 2018;79:7–10. doi: 10.4088/JCP.16m11324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garrido MM, Boockvar KS. Perceived symptom targets of antidepressants, anxiolytics, and aedatives: the search for modifiable factors that improve adherence. J Behav Heal Serv Res. 2014;41:529–538. doi: 10.1007/s11414-013-9342-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee M, Lee H, Kang SG, Yang J, Ahn H, Rhee M, et al. Variables influencing antidepressant medication adherence for treating outpatients with depressive disorders. J Affect Disord. 2010;123:216–221. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hung CI. Factors predicting adherence to antidepressant treatment. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2014;27:344–349. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chong WW, Aslani P, Chen TF. Effectiveness of interventions to improve antidepressant medication adherence: A systematic review. Int J Clin Pract. 2011;65:954–975. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2011.02746.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pampallona S, Bollini P, Tibaldi G, Kupelnick B, Munizza C. Patient adherence in the treatment of depression. Br J Psychiatry. 2002;180:104–109. doi: 10.1192/bjp.180.2.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vergouwen ACM, Bakker A, Katon WJ, Verheij TJ, Koerselman F. Improving adherence to antidepressants: a systematic review of interventions. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64:1415–1420. doi: 10.4088/JCP.v64n1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Semahegn A, Torpey K, Manu A, Assefa N, Tesfaye G, Ankomah A. Psychotropic medication non-adherence and associated factors among adult patients with major psychiatric disorders: a protocol for a systematic review. Syst Rev. 2018;7:10. doi: 10.1186/s13643-018-0676-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Loots E, Goossens E, Vanwesemael T, Morrens M, Van Rompaey B, Dilles T. Interventions to improve medication adherence in patients with schizophrenia or bipolar disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:10213. doi: 10.3390/ijerph181910213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Allemann SS, Nieuwlaat R, van den Bemt BJF, Hersberger KE, Arnet I. Matching adherence interventions to patient determinants using the theoretical domains framework. Front Pharmacol. 2016;7:429. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2016.00429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Higgins J, Green S. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Version 5. The Cochrane Collaboration; 2011.

- 20.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, The PRISMA, et al. statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2020;2021:372. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Higgins JP, Savović E, Page MJ, Sterne JA. Revised Cochrane risk of bias tool for randomized trials (RoB 2.0). In: Chandler J, McKenzie I, Boutron I, Welch V, editors. Cochrane Methods. Cochrane Database of Systematic Review; 2016. p. (Suppl 1).

- 22.Eldridge S, Campbell M, Campbell M, Dahota A, Giraudeau B, Higgins J, et al. Revised Cochrane risk of bias tool for randomized trials (RoB 2.0) Additional considerations for cluster-randomized trials. Cochrane Methods. 2016;18.

- 23.Sterne JA, Hernán MA, Reeves BC, Savović J, Berkman ND, Viswanathan M, et al. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ. 2016;355:i4919. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i4919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dersimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7:177–188. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Adler DA, Bungay KM, Wilson IB, Pei Y, Supran S, Peckham E, et al. The impact of a pharmacist intervention on 6-month outcomes in depressed primary care patients. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2004;26:199–209. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2003.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Akerblad A-C, Bengtsson F, Ekselius L, von Knorring L. Effects of an educational compliance enhancement programme and therapeutic drug monitoring on treatment adherence in depressed patients managed by general practitioners. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2003;18:347–354. doi: 10.1097/01.yic.0000091305.72168.6e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Desplenter F, Laekeman G, Simoens S. Differentiated information on antidepressants at hospital discharge: a hypothesis-generating study. Int J Pharm Pract. 2013;21:252–262. doi: 10.1111/ijpp.12001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gervasoni N, Legendre-Simon P, Aubry JM, Gex-Fabry M, Bertschy G, Bondolfi G. Early telephone intervention for psychiatric outpatients starting antidepressant treatment. Nord J Psychiatry. 2010;64:265–267. doi: 10.3109/08039480903528641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hammonds T, Rickert K, Goldstein C, Gathright E, Gilmore S, Derflinger B, et al. Adherence to antidepressant medications: a randomized controlled trial of medication reminding in college students. J Am Coll Heath. 2015;63:204–208. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2014.975716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Interian A, Lewis-Fernández R, Gara MA, Escobar JI. A randomized-controlled trial of an intervention to improve antidepressant adherence among latinos with depression. Depress Anxiety. 2013;30:688–696. doi: 10.1002/da.22052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.John AP, Singh NM, Nagarajaiah, Andrade C. Impact of an educational module in antidepressant-naive patients prescribed antidepressants for depression: Pilot, proof-of-concept, randomized controlled trial. Indian J Psychiatry. 2016;58:425–31. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.196710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Katon W, Russo J, Von Korff M, Lin E, Simon G, Bush T, et al. Long-term Effects of a collaborative care intervention in persistently depressed primary care patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17:741–748. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.11051.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Katon W, Rutter C, Ludman EJ, Von Korff M, Lin E, Simon G, et al. A randomized trial of relapse prevention of depression in primary care. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:241–247. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.3.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Katon W, Von KM, Lin E, Simon G, Walker E. Stepped collaborative care for primary care patients with persistent symptoms of depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56:1109–1115. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.12.1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Katon W, Robinson P, Von KM, Lin E, Bush T, Ludman E, et al. A multifaceted intervention to improve treatment of depression in primary care. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1996;53:924–932. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830100072009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Katon W. Collaborative management to achieve treatment guidelines. JAMA. 1995;273:1026. doi: 10.1001/jama.1995.03520370068039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Al-Saffar N, Abdulkareem A, Abdulhakeem A, Salah A, Heba M. Depressed patients’ preferences for education about medications by pharmacists in Kuwait. Patient Educ Couns. 2008;72:94–101. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Keeley RD, Burke BL, Brody D, Dimidjian S, Engel M, Emsermann C, et al. Training to use motivational interviewing techniques for depression: a cluster randomized trial. J Am Board Fam Med. 2014;27:621–636. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2014.05.130324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Klang SH, Ben-Amnon Y, Cohen Y, Barak Y. Community pharmacists’ support improves antidepressant adherence in the community. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2015;30:316–319. doi: 10.1097/YIC.0000000000000090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kutcher S, Leblanc J, Maclaren C, Hadrava V. A randomized trial of a specific adherence enhancement program in sertraline-treated adults with major depressive disorder in a primary care setting. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2002;26:591–596. doi: 10.1016/S0278-5846(01)00313-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.LeBlanc A, Herrin J, Williams MD, Inselman JW, Branda ME, Shah ND, et al. Shared decision making for antidepressants in primary care a cluster randomized trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175:1761–1770. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.5214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lin EHB, Von Korff M, Ludman EJ, Rutter C, Bush TM, Simon GE, et al. Enhancing adherence to prevent depression relapse in primary care. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2003;25:303–310. doi: 10.1016/S0163-8343(03)00074-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lin EHB, Simon GE, Katon WJ, Russo JE, Von Korff M, Bush TM, et al. Can enhanced acute-phase treatment of depression improve long-term outcomes? A report of randomized trials in primary care. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:643–645. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.4.643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mantani A, Kato T, Furukawa TA, Horikoshi M, Imai H, Hiroe T, et al. Smartphone cognitive behavioral therapy as an adjunct to pharmacotherapy for refractory depression: Randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2017;19:1–20. doi: 10.2196/jmir.8602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Meglic M, Furlan M, Kuzmanic M, Kozel D, Baraga D, Kuhar I, et al. Feasibility of an eHealth service to support collaborative depression care: results of a pilot study. J Med Internet Res. 2010;12:1–17. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mundt JC, Clarke GN, Burroughs D, Brenneman DO, Griest JH. Effectiveness of antidepressant pharmacotherapy: the impact of medication compliance and patient education. Depress Anxiety. 2001;13:1–10. doi: 10.1002/1520-6394(2001)13:1<1::AID-DA1>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Myers ED, Calvert EJ. The effect of forewarning on the occurrence of side-effects and discontinuance of medication in patients on dothiepin. J Int Med Res. 1976;4:237–240. doi: 10.1177/030006057600400405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Al-Saffar N, Deshmukh AA, Carter P, Adib SM. Effect of information leaflets and counselling on antidepressant adherence: open randomised controlled trial in a psychiatric hospital in Kuwait. Int J Pharm Pract. 2005;13:123–132. doi: 10.1211/0022357056181. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Myers E, Calvert E. Information, compliance and side-effects: a study of patients on antidepressant medication. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1984;17:21–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1984.tb04993.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nwokeji ED, Bohman TM, Wallisch L, Stoner D, Christensen K, Spence RR, et al. Evaluating patient adherence to antidepressant therapy among uninsured working adults diagnosed with major depression: results of the Texas demonstration to maintain independence and employment study. Adm Policy Ment Heal Ment Heal Serv Res. 2012;39:374–382. doi: 10.1007/s10488-011-0354-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Perahia DGS, Quail D, Gandhi P, Walker DJ, Peveler RC. A randomized, controlled trial of duloxetine alone vs. duloxetine plus a telephone intervention in the treatment of depression. J Affect Disord. 2008;108:33–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2007.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pradeep J, Isaacs A, Shanbag D, Selvan S, Srinivasan K. Enhanced care by community health workers in improving treatment adherence to antidepressant medication in rural women with major depression. Indian J Med Res. 2003;461:236–245. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Richards DA, Bower P, Chew-Graham C, Gask L, Lovell K, Cape J, et al. Clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of collaborative care for depression in UK primary care (CADET): a cluster randomised controlled trial. Health Technol Assess (Rockv) 2016;20:1–192. doi: 10.3310/hta20140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rickles NM, Svarstad BL, Statz-Paynter JL, Taylor LV, Kobak KA. Pharmacist telemonitoring of antidepressant use: Effects on pharmacist-patient collaboration. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2005;45:344–353. doi: 10.1331/1544345054003732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rickles N, Svarstad B, Statz-Paynter J, Taylor L, Kobak K. Improving patient feedback about and outcomes with antidepressant treatment: a study in eight community pharmacies. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2006;46:25–32. doi: 10.1331/154434506775268715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Salkovskis P, Rimes K, Stephenson D, Sacks G, Scott J. A randomized controlled trial of the use of self-help materials in addition to standard general practice treatment of depression compared to standard treatment alone. Psychol Med. 2006;36:325–333. doi: 10.1017/S0033291705006422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Simon GE, Ludman EJ, Operskalski BH. Randomized trial of a telephone care management program for outpatients starting antidepressant treatment. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57:1441–1445. doi: 10.1176/ps.2006.57.10.1441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Simon GE, Ralston JD, Savarino J, Pabiniak C, Wentzel C, Operskalski BH. Randomized trial of depression follow-up care by online messaging. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26:698–704. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1679-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Aljumah K, Hassali MA. Impact of pharmacist intervention on adherence and measurable patient outcomes among depressed patients: a randomised controlled study. BMC Psychiatry. 2015;15:1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12888-015-0605-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Smit A, Tiemens BG, Ormel J, Kluiter H, Jenner JA, van de Meer K, et al. Enhanced treatment for depression in primary care: First year results on compliance, self-efficacy, the use of antidepressants and contacts with the primary care physician. Prim Care Community Psychiatry. 2005;10:39–49. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Vannachavee U, Seeherunwong A, Yuttatri P, Chulakadabba S. The effect of a drug adherence enhancement program on the drug adherence behaviors of patients with major depressive disorder in Thailand: a randomized clinical trial. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2016;30:322–328. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2015.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Vergouwen AC, Burger H, Verheij TJ, Koerselman F. Improving patients’ beliefs about antidepressants in primary care. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;11:48–52. doi: 10.4088/PCC.08m00686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Vergouwen AC, Bakker A, Burger H, Verheij TJ, Koerselman F. A cluster randomized trial comparing two interventions to improve treatment of major depression in primary care. Psychol Med. 2005;35:25–33. doi: 10.1017/S003329170400296X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wiles N, Hollinghurst S, Mason V, Musa M, Burt V, Hyde J, et al. A randomized controlled trial of cognitive behavioural therapy as an adjunct to pharmacotherapy in primary care based patients with treatment resistant depression: a pilot study. Behav Cogn Psychother. 2008;36:21–33. doi: 10.1017/S135246580700389X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wiles N, Thomas L, Abel A, Ridgway N, Turner N, Campbell J, et al. Cognitive behavioural therapy as an adjunct to pharmacotherapy for primary care based patients with treatment resistant depression: results of the CoBalT randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2013;381:375–384. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61552-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wiles N, Thomas L, Abel A, Barnes M, Carroll F, Ridgway N, et al. Clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of cognitive behavioural therapy as an adjunct to pharmacotherapy for treatment-resistant depression in primary care: the CoBalT randomised controlled trial. Health Technol Assess. 2014;18:1–167. doi: 10.3310/hta18310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Guo T, Xiang YT, Xiao L, Hu CQ, Chiu HFK, Ungvari GS, et al. Measurement-based care versus standard care for major depression: a randomized controlled trial with blind raters. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172:1004–1013. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.14050652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yusuf H, Magaji MG, Maiha BB, Yakubu SI, Haruna WC, Mohammed S. Impact of pharmacist intervention on antidepressant medication adherence and disease severity in patients with major depressive disorder in fragile north-east Nigeria. J Pharm Heal Serv Res. 2021;12:410–416. doi: 10.1093/jphsr/rmab030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Marasine NR, Sankhi S, Lamichhane R. Impact of pharmacist intervention on medication adherence and patient-reported outcomes among depressed patients in a private psychiatric hospital of Nepal: a randomised controlled trial. Hosp Pharm. 2020;57(1):26–31. doi: 10.1177/0018578720970465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Browne G, Steiner M, Roberts J, Gafni A, Byrne C, Dunn E, et al. Sertraline and/or interpersonal psychotherapy for patients with dysthymic disorder in primary care: 6-Month comparison with longitudinal 2-year follow-up of effectiveness and costs. J Affect Disord. 2002;68:317–330. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0327(01)00343-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Capoccia KL, Boudreau DM, Blough DK, Ellsworth AJ, Clark DR, Stevens NG, et al. Randomized trial of pharmacist interventions to improve depression care and outcomes in primary care. Am J Heal Syst Pharm. 2004;61:364–372. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/61.4.364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Chang TE, Jing Y, Yeung AS, Brenneman SK, Kalsekar ID, Hebden T, et al. Depression monitoring and patientbehavior in the clinical outcomes in measurement-based treatment (COMET) Trial. Psychiatr Serv. 2014;65:1058–1061. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201300326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Crockett J, Taylor S, Grabham A, Stanford P. Patient outcomes following an intervention involving community pharmacists in the management of depression. Aust J Rural Health. 2006;14:263–269. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1584.2006.00827.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.De Jonghe F, Kool S, Van Aalst G, Dekker J, Peen J. Combining psychotherapy and antidepressants in the treatment of depression. J Affect Disord. 2001;64:217–229. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0327(00)00259-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Perlis RH, Nierenberg AA, Alpert JE, Pava J, Matthews JD, Buchin J, et al. Effects of adding cognitive therapy to fluoxetine dose increase on risk of relapse and residual depressive symptoms in continuation treatment of major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 22(5):474–80. 10.1097/00004714-200210000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 76.Ekers D, Murphy R, Archer J, Ebenezer C, Kemp D, Gilbody S. Nurse-delivered collaborative care for depression and long-term physical conditions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2013;149:14–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Van den Broeck K, Remmen R, Vanmeerbeek M, Destoop M, Dom G. Collaborative care regarding major depressed patients: a review of guidelines and current practices. J Affect Disord. 2016;200:189–203. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.04.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Conn VS, Ruppar TM, Enriquez M, Cooper PS, Chan KC. Healthcare provider targeted interventions to improve medication adherence: systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Clin Pract. 2015;69(8):889–99. doi: 10.1111/ijcp.12632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Farmer AJ, McSharry J, Rowbotham S, McGowan L, Ricci-Cabello I, French DP. Effects of interventions promoting monitoring of medication use and brief messaging on medication adherence for people with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review of randomized trials. Diabet Med. 2016;33:565–579. doi: 10.1111/dme.12987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.MacDonald L, Chapman S, Syrett M, Bowskill R, Horne R. Improving medication adherence in bipolar disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 30 years of intervention trials. J Affect Disord. 2016;194:202–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Dayer L, Heldenbrand S, Anderson P, Gubbins PO, Martin BC. Smartphone medication adherence Apps: potential benefits to patients and providers. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2013;53:172–181. doi: 10.1331/JAPhA.2013.12202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Rootes-Murdy K, Glazer KL, Van Wert MJ, Mondimore FM, Zandi PP. Mobile technology for medication adherence in people with mood disorders: a systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2017;227:613–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2017.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Cavanagh K. Geographic inequity in the availability of cognitive behavioural therapy in england and wales: a 10-year update. Behav Cogn Psychother. 2014;42:497–501. doi: 10.1017/S1352465813000568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kardas P, Lewek P, Matyjaszczyk M. Determinants of patient adherence: a review of systematic reviews. Front Pharmacol. 2013;4:91. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2013.00091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Keyloun KR, Hansen RN, Hepp Z, Gillard P, Thase ME, Devine EB. Adherence and persistence across antidepressant therapeutic classes: a retrospective claims analysis among insured us patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) CNS Drugs. 2017;31(5):421–432. doi: 10.1007/s40263-017-0417-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ji N-J, Jeon S-Y, Min K-J, Ki M, Lee W-Y. The effect of initial antidepressant type on treatment adherence in outpatients with new onset depression. J Affect Disord. 2022;311:582–587. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2022.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Supplementary Table 1. Search strategy.

Additional file 2: Supplementary Table 2. Results on adherence in the included studies.

Additional file 3: Supplementary Table 3. Meta-Analyses of Adherence outcome and Subgroup Analyses.

Additional file 4: Supplementary Table 4. Meta-Regression Analyses (6 months).

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.