Abstract

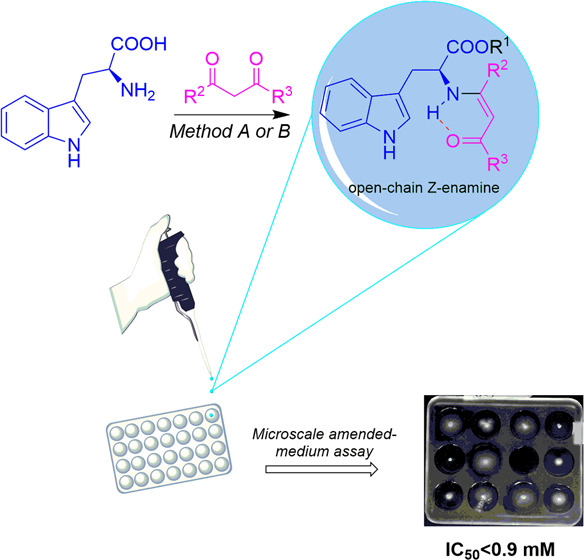

Schiff bases are widely used molecules due to their potential biological activity. In this manuscript, we presented the synthesis and NMR study of new enamine Schiff bases derived from l-tryptophan, showing that the Z-form of the enamine is the main tautomeric form for aliphatic precursors. The DFT-B3LYP methodology at the 6-311+G**(d,p) level suggested that the tautomeric imine forms are less stable than the corresponding enamine forms. Their isomerism depends on the formation of intramolecular hydrogen bonds and steric factors associated with the starting carbonyl precursors. The in vitro biological activity tests against Fusarium oxysporum revealed that acetylacetone derivatives are the most active agents (IC50 < 0.9 mM); however, the antifungal activity could be disfavored by bulky groups on ester and enamine moieties. Finally, the structure-based virtual screening through molecular docking and MM-GBSA rescoring revealed that Schiff bases 3e, 3g, and 3j behave putatively as binders for target proteins involved in the life processes of F. oxysporum. In this sense, molecular dynamics analysis showed that the ligand–protein complexes have good stability with root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) values within the allowed range. Therefore, the present study paves the way for designing new antifungal compounds based on l-tryptophan-derived Schiff bases.

Introduction

Fusarium oxysporum is a broad-spectrum phytopathogen that significantly impacts the agricultural sector, precisely many horticultural, field, ornamental, and forest crops in agricultural and natural ecosystems.1,2 It is known that diseases caused by F. oxysporum and the wide range of mycotoxins can contaminate agricultural products, rendering them unsuitable for human consumption. Different strategies have been developed to achieve its control,3 the chemical control being the most broadly employed. However, the secondary effects generated by synthetic fungicides with high residuality can be even more harmful than the pathogen. These effects only appear when the amount of pesticide in the body is more significant than it can eliminate, so it accumulates and reaches the toxic level.4 In addition, the frequent use of pesticides can harden or stunt cultivars of a species. Combinations of agrochemical agents are often used, seeking a synergistic effect on the different pathogens, ending up enhancing their effects and causing chemical alterations that originate new chemical substances and generate resistance in the phytopathogen.5,6 Moreover, the combination of substances with probable carcinogenic or endocrine-disrupting effects may produce unknown adverse health effects. Therefore, determining “safe” levels of exposure to individual pesticides may underestimate actual health effects, also ignoring chronic exposure to multiple chemicals. Considering the health and environmental effects of chemical pesticides, several alternatives have been sought that allow chemical pest control with minimal impact, which should be based on a drastic reduction in the application of residual chemical pesticides to benefit health, the environment, and the economy.7

The use of eco-friendly chemical compounds such as biofungicides, elicitors, plant activators, and synthetic analogues that may be bioisosteres of secondary metabolites with potential antifungal activity has emerged.8−11 The Bioorganic Chemistry laboratory at Universidad Militar Nueva Granada has recently oriented its research to develop new antifungal agents based on common amino acids. These compounds of high importance for human health12 have been used for developing new technologies based on biologically active molecules to combat and/or remedy the damages caused by multiple phytopathogens in the agricultural sector and have gained significant interest in recent years.13,14 The structural modification of amino acids and peptides through conventional organic chemistry reactions is a valuable and versatile tool for accessing new biologically active molecules. For instance, a new series of dithiocarbamate-linked peptidomimetics were prepared in situ through the reaction between dithiocarbamic acid intermediate, amino acid ester, carbon disulfide, and N-protected amino/peptide alkyl iodide under mild conditions.15 Functional multidentate ligands based on pyrazole and amino acid derivatives were prepared by the reaction of amino acid ester hydrochlorides and (3,5-dimethyl-1H-pyrazole-1-yl)methanol. These compounds showed suitable antifungal activities against F. oxysporum f.sp. albedinis.16 Recently, several quinoxaline hydrazide derivatives such as heterocyclic compounds containing quinoxaline linked to 1,3,4-oxadiazolethione or pyrazole and Schiff’s bases were obtained and tested against Alternaria brassicicola and F. oxysporum, showing high biological activities.17 These antecedents have inspired us to continue studying the derivatization of amino acids adding imine and/or enamine group as pharmacophore,18,19 using conventional reactions toward an eco-friendly protocol with a slight environmental impact, taking advantage of the Schiff condensation reaction.20−24 From medicinal and pharmaceutical perspectives, Schiff bases have demonstrated a potential interest due to their demonstrated biological activities such as anti-inflammatory,25,26 analgesic,25,27 antimicrobial,17,23,28,29 anticonvulsant,30,31 antituberculous,32 anticáncer,33 antioxidant,34,35 anthelmintic,36 antiviral,37 and antifungal.34,38−41 Many Schiff bases have also been used as substrates to prepare numerous biologically active compounds, becoming interesting precursors in organic syntheses. Recently, a series of chitosan derivatives40,42 were successfully synthesized via the Schiff reaction employing aldehydes with a high degree of substitution, among those bearing active halogenated aromatic imines. The antifungal activity studies against Botrytis cinerea, F. oxysporum f. sp. cucumerinum, and F. oxysporum f. sp. niveum showed that double Schiff bases of chitosan derivatives exhibited enhanced antifungal activity in comparison to that of chitosan, concluding that the higher degree of substitution was another positive effect to improve the antifungal activity.40 Reactions of 5-(morpholinosulfonyl)indol-2,3-dione with appropriate amines or hydrazide derivatives afforded several Schiff bases, which exhibit significant antibacterial activity against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria and potential inhibitory activity against DNA gyrase isolated from Staphylococcus aureus.29 Schiff bases derived from inulin showed significantly improved antioxidant and antifungal activities than pure inulin.34,38,41

Continuing our research, we describe the synthesis and characterization of a series of novel Schiff bases 3a–l derived from l-tryptophan, which were obtained by employing two methodologies. A structural analysis using uni- and bidimensional (1D and 2D) NMR experiments is also described, which led us to conclude the existence of the enamine tautomer only in the CDCl3 liquid phase. A DFT-B3LYP analysis at the level 6-311+G**(d,p) is presented, performing a comparison between both the selected experimental and theoretical, representative C=C-NH and C=N stretching band frequencies for the synthesized compounds to understand the leading electronic and hindrance structural factors, which determine the stabilization of the preferred tautomeric forms. The antifungal activities of the products 3a–l were tested against F. oxysporum, using a microscale amended-medium protocol. Finally, molecular docking and molecular dynamics were performed against several enzymatic targets of the studied phytopathogen. The results revealed that some Schiff bases have a strong binding affinity for target proteins involved in the life processes of F. oxysporum, which are discussed below (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1. Synthesis of Enamines 3a–l.

Results and Discussion

Synthesis

Two methodologies were performed and subsequently optimized to obtain novel Schiff bases derived from l-tryptophan. Method A employed a 2-step linear strategy. The first step involved the l-tryptophan esterification reactions following the previously reported procedure,43 affording 2-aminoesters 1a–d as hydrochloride salts, which were collected by vacuum filtration. Thus, the second step comprised the reactions of 1a–d·HCl against 1,3-dicarbonyl compounds 2a–c, carried out in tetrahydrofuran (THF) under reflux during 20–30 h in the presence of triethylamine (TEA). Contrarily, method B employed a one-pot strategy. First, 2-aminoesters 1a–d were obtained in situ by reaction between l-tryptophan and the respective alcohol in SiMe3Cl or SOCl2 at reflux conditions for 5 h. TEA was then added until achieving a basic medium. Then, the dicarbonyl compounds 2a–c were added to keep the reflux conditions until total reagents were consumed. The obtaining yields for both methods A and B are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Yields of the Synthesized Compounds 3a–l Using Method A or B.

| product | method A: linear strategy reaction conditions for each step 1. and 2. (solvent, temperature, time) | yield (%) | method B: one-pot reaction conditions (solvent, temperature, time) | yield (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3a | 1. MeOH, rt, 24 h; 2. THF, reflux, 20 h | 45 | MeOH, reflux, 20 h | 89 |

| 3b | 1. EtOH, rt, 24 h; 2. THF, reflux, 20 h | 31 | EtOH, reflux, 20 h | 85 |

| 3c | 1. i-PrOH, rt, 24 h; 2. THF, reflux, 20 h | 17 | i-PrOH, reflux, 20 h | 77 |

| 3d | 1. n-BuOH, rt, 24 h; 2. THF, reflux, 20 h | 12 | n-BuOH, reflux, 20 h | 76 |

| 3e | 1. MeOH, rt, 24 h; 2. THF, reflux, 25 h | 41 | MeOH, reflux, 25 h | 81 |

| 3f | 1. EtOH, rt, 24 h; 2. THF, reflux, 25 h | 33 | EtOH, reflux, 25 h | 74 |

| 3g | 1. i-PrOH, rt, 24 h; 2. THF, reflux, 25 h | 15 | i-PrOH, reflux, 25 h | 69 |

| 3h | 1. n-BuOH, rt, 24 h; 2. THF, reflux, 25 h | 9 | n-BuOH, reflux, 25 h | 66 |

| 3i | 1. MeOH, rt, 24 h; 2. THF, reflux, 30 h | 40 | MeOH, reflux, 30 h | 75 |

| 3j | 1. EtOH, rt, 24 h; 2. THF, reflux, 30 h | 29 | EtOH, reflux, 30 h | 72 |

| 3k | 1. i-PrOH, rt, 24 h; 2. THF, reflux, 30 h | 16 | i-PrOH, reflux, 30 h | 67 |

| 3l | 1. n-BuOH, rt, 24 h; 2. THF, reflux, 30 h | 8 | n-BuOH, reflux, 30 h | 65 |

On the other hand, to explore structural and quantum features of products 3a–l, optimization of the molecular structure and total energy calculations were performed for enamine 3 and imine 4 forms (Scheme 2), using the method DFT-B3LYP at the level 6-311+G**(d,p) assuming gas phase. The total energies for Z-enamine, E-enamine, and imine forms and ΔEE-enamine-imine and ΔEE-enamine- Z-enamine differences were computed, whose results are presented in Table 2. Total energies were within the −955.918 to −1227.468 Hartree range, and the energy differences were between −0.013 and −7.320 Hartree.

Scheme 2. Enamine and Imine Tautomeric Forms of the Synthesized Compounds.

Table 2. Calculated DFT-B3LYP Total Energies for the Two Possible Z- and E-Isomeric Enamine (3)–Imine (4) Tautomers.

| product | Z-enamine form energya | E-enamine form energya | imine form energya | ΔEaE-enamine–imine | ΔEaE-enamine– Z-enamine |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3a | –955.977 | –955.990 | –955.918 | –0.072 | –0.013 |

| 3b | –996.722 | –996.743 | –996.671 | –0.072 | –0.021 |

| 3c | –1028.131 | –1034.645 | –1034.573 | –0.072 | –6.514 |

| 3d | –1067.169 | –1073.967 | –1073.888 | –0.079 | –6.798 |

| 3e | –1109.516 | –1109.537 | –1109.472 | –0.065 | –0.021 |

| 3f | –1148.821 | –1148.855 | –1149.787 | –0.068 | –0.034 |

| 3g | –1181.408 | –1188.169 | –1188.098 | –0.071 | –6.761 |

| 3h | –1220.637 | –1227.468 | –1227.396 | –0.072 | –6.831 |

| 3i | –1026.964 | –1033.434 | –1033.359 | –0.075 | –6.470 |

| 3j | –1071.834 | –1077.981 | –1070.911 | –0.070 | –6.147 |

| 3k | –1105.055 | –1112.092 | –1112.013 | –0.079 | –7.037 |

| 3l | –1144.092 | –1151.412 | –1151.331 | –0.081 | –7.320 |

All of the energy values are expressed in Hartree.

The yields for compounds 3a–l varied according to the respective alcohol precursor (Table 1) since a greater alkyl substituent at the ester group conduced a yield reduction. Alkyl 2-aminoesters 1c and 1d derived from isopropanol and n-butanol and extended long-chain alcohols are less reactive against compounds 2. An apparent steric hindrance in the transition state of the nucleophilic addition reaction in the first step of the expected reaction mechanism presumably reduces the rate, making it the limiting step for the formation of compounds 3. The differences between methods A and B can be rationalized according to the stability and THF solubility of l-tryptophan-derived 2-aminoesters 1a–d. It was evidenced that compounds 1a–d hydrolyze by absorbing humidity from the environment. On the other hand, compounds 1a–d showed poor solubility in THF even at reflux conditions despite their polarity (calculated dipole moment between 0.6812 and 0.8578 D). For this reason, method B is more efficient since compounds 1a–d are obtained in situ and, subsequently, underwent a condensation reaction with the carbonyl compounds 2a–c, affording Schiff bases 3a–l.

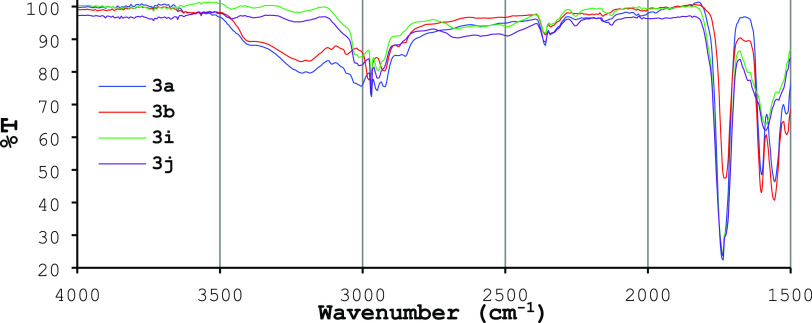

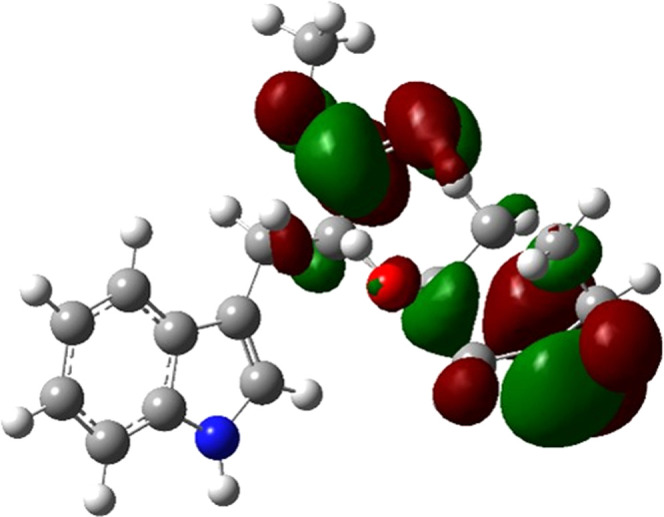

Compounds containing a hydrogen atom on the α position at the C=N bond can experience tautomerism. Several studies have shown that imine tautomers are chemically more stable than enamine tautomers. However, the enamine–imine energetical interconversion barrier is lesser, by 1 order of magnitude, than that of keto–enol tautomerization.44 This tautomer quantitative ratio largely depends on the solvent polarity, the chemical structures of reactants, and the temperature.45 In all performed reactions, one of these tautomeric forms was detected. According to the results in Table 2, the enamine tautomeric forms are more stable than the imine forms, differing in their energy by 0.065–0.081 Hartree. Although the literature establishes that the imine form tends to be more favored, these calculations suggested that the presence of a carbonyl group in position 3 at the C=N group increases the electronic system stability by conjugation of the π-system, as shown by the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) representation in compound 3a (Figure 1). This orbital showed an occupancy of 0.00544 as a Rydberg-type orbital, comprising an s (6.50%) and p 14.38 (93.50%) hybridization, which confirmed the extension of the conjugated π-system for enamine forms.

Figure 1.

Representation of LUMO for compound 3a (isovalue: 0.02).

The DFT-B3LYP analysis on the Z- and E-isomers of the enamine tautomers of compounds 3a–l showed that the E-isomer should be more stable than the Z-isomer. The calculated energies exhibited slight differences for compounds 3a,b and 3e–f, obtained from methyl and ethyl esters 1a,b, indicating that the two isomers should be found at similar ratios. However, the calculated energy differences increase dramatically in compounds 3c,d and 3g–h, obtained from isopropyl and n-butyl esters 1c,d. In the case of derivatives 3i–l obtained from cyclic dicarbonyl compounds as 2c, the energy differences were found around −6.5 Hartree, increasing as the size of the R2 side chain of the RCOOR moiety increases. The repulsive interactions between the C=O and the R2 side chain can explain these results experienced by the hypothetical Z-isomer. Moreover, the bulky indolyl group and axial hydrogen atoms of the cyclohexanone-type ring could undergo a disfavorable steric hindrance. In addition, the conformation to be adopted of the cyclic system in 3i–l leads to unfavorable torsional stresses that reduce its stability (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Proposed molecular structure for the Z-isomer 3l.

Remarkably, 1D and 2D NMR experiments allowed us to identify the synthesized compounds 3a–h as the Z-enamine tautomers, whereas compounds 3i–l were identified as the E-enamine tautomers. All of the 1H NMR spectra showed a singlet signal between δH 4.0 and 5.0, characteristic of the C=C–H moiety. The signals for the NH-C=C fragment appeared around δH 8.0–9.0 for compounds 3a–h. However, these signals for compounds 3i–l were observed between δH 4.0 and 5.0 as doublets (J = 7.6 Hz). The 13C NMR spectra showed two signals for the enamine group, viz., the respective carbon atom directly attached to the NH group at δC 160, and the C=CH carbon atoms showed signals between δC 80 and 90. Two-dimensional (2D) NMR experiments such as 2D correlation spectroscopy (2D-COSY), heteronuclear single quantum coherence (HSQC), heteronuclear multiple bond correlation (HMBC), and 2D nuclear Overhauser effect spectroscopy (2D-NOESY) were also recorded for a CDCl3 solution of compound 3a to confirm the enamine’s presence and establish the isomerism for the enamine functional group. The 2D-COSY spectrum indicated 1H–1H couplings according to the shown cross peak between the H attached to the chiral carbon (δH 4.45) with the NH proton (δH 11.07) (Figure 3a). Moreover, coupling with the methylene protons (CH2) (δH 3.31) was also observed. HSQC experiment revealed a correlation between the signals at δH 4.97 and δC 96.67, assigned to the C=C–H moiety (Figure 3b). Furthermore, the HMBC experiment showed that the signal at δH 4.97 (C=CH) correlated with the signals at δC 197.9, 161.8, 29.4, and 19.0 (Figure 2c). Thus, the full previous information allowed complete assignments of both 1H and 13C atoms in products 3a–l.

Figure 3.

Two-dimensional (2D) experiments for compound 3a in CDCl3. (a) 2D-COSY, (b) HSQC, (c) HMBC, and (d) 2D-NOESY.

Additionally, 2D-NOESY experiments evidenced a spatial correlation between the hydrogen atom in the enamine fragment (C=CH, δC 4.97) and the methyl protons (Hb) on the H3C–CO moiety, which resonates at δH 1.68 (Figure 3d). A similar correlation is observed with the methyl protons Ha on the H3C–C=C moiety, resonating at δH 2.03, but only presented in compounds 3a–h. According to the DFT-B3LYP analysis, the formation of the Z-isomer instead of the E-isomer for compounds 3a–h is unexpected. We proposed that this formation is favored by forming an intramolecular H-bonding interaction between N–H and C=O in the enamine fragment. These interactions could be rationalized considering NMR results and Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR) spectra. The hydrogen atom signals of the NH group in compounds 3a–h were shifted to a low field in the 1H NMR experiments (up to δH 10). FT-IR spectra of selected compounds confirmed an intramolecular H-bonding interaction between N–H in the enamine fragment and the C=O group in compounds 3a–h (Figure 4). The stretching absorption of the C=C bond of the enamine group appeared for all compounds as a signal of medium intensity (ca. 1605 cm–1). However, the position of this band varied in each enamine and, therefore, it appeared at 1595 cm–1 for compounds 3i–j. The wavenumber differences of this absorption band can be rationalized as an inductive effect produced by a partial electronic delocalization in the C=C-NH moiety, and due to the H-bonding interaction, a band displacement at a higher frequency is observed. The C=O stretching band of the ester group appeared as a high-intensity band around 1737 cm–1 for all compounds, showing that this functional group is not involved in the inter- or intramolecular interactions. The most relevant result is the appearance of a widened band for compounds 3a,b in the 2800–3420 cm–1 region, which is a characteristic of compounds experiencing these kinds of interactions. Compounds 3i–j (cyclohexane-1,3-dione 2c derivatives) did not show this widening band, showing sharp and differentiable bands corresponding to the C(sp3)–H stretching absorptions around 2970 cm–1 and C(sp2)–H and N–H bands above 3000 cm–1. Under this context, we concluded that E isomerism is predominant in cyclic 1,3-dicarbonyl derivatives, as observed for compounds 3i–l. These results suggested that the formation of an intermolecular H-bonding influences the reaction pathway, favoring the formation of Z-isomers derived from aliphatic 1,3-dicarbonyl compounds via a kinetic control.45

Figure 4.

FT-IR spectra in the region between 1500 and 4000 cm–1 of selected compounds 3a,b and 3i–j.

Antifungal Activity of the Synthetic Compounds

In vitro antifungal activity testing against F. oxysporum was performed using a microscale amended-medium assay.46 Compounds 3a–l were evaluated at five concentrations in the 10–500 μg/mL range, using fludioxonil as the reference antifungal. The results were expressed as a half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50 in mM) for each compound, summarized in Table 3. The IC50 values ranged between 0.60 and 3.86 mM, including four compounds that exceeded the highest test concentration, i.e., IC50 > 100 mM for compounds 3g,h,k,l.

Table 3. Antifungal Activity of Compounds 3a–l against F. oxysporum.

| product | IC50 (mM)a |

|---|---|

| 3a | 0.60 ± 0.02 |

| 3b | 0.52 ± 0.03 |

| 3c | 0.72 ± 0.02 |

| 3d | 0.87 ± 0.06 |

| 3e | 0.60 ± 0.05 |

| 3f | 2.90 ± 0.03 |

| 3g | >100 |

| 3h | >100 |

| 3i | 3.86 ± 0.02 |

| 3j | 2.55 ± 0.01 |

| 3k | >100 |

| 3l | >100 |

| fludioxonil | 0.061 ± 0.002 |

Data expressed as mean values ± standard deviation (SD) (n = 3).

Compounds 3a–l exhibited an in vitro antifungal activity on the mycelial growth of F. oxysporum at different levels (Table 3). Results suggested that the size of the substituent and the electronic character in the enamine-3-one fragment influence antifungal activity. The lowest IC50 values were measured for compounds 3a–d (0.60 mM < IC50 < 0.87 mM), which were achieved from acetylacetone 2a. On the other hand, the highest IC50 values were obtained for those compounds with isopropyl or n-butyl as R2 side chains and derived from ethyl acetoacetate and cyclohexane-1,3-dione, possibly by conferring higher hydrophobicity (cLogP > 3.0) in comparison to that of methyl and ethyl substitutions (1.9 < cLogP < 2.8). Moreover, compounds 3e,f,k,l showed lower activity than compounds 3a,b, suggesting that the presence of the ester group in conjugation with the enamine fragment and the presence of a bulky group, as a cyclohexane-3-one system, affected the inhibitory action of these compounds. In this regard, bulky substituents could promote the formation of hydrophobic interactions and avoid the correct binding mode within specific fungal targets. Therefore, a structure–activity (SA) trend can be deduced with this small compound set since the antifungal activity is enhanced by short alkoxy groups and small R4 substitutions at ester and enamine moieties. However, the influence of the enamine E/Z isomerism of most active compounds on the antifungal activity is unclear and could be further studied.

Homology Modeling of F. oxysporum Enzyme Targets

To expand our study toward enzyme targets in F. oxysporum that putatively interact with the synthesized compounds 3a–l, a search for filamentous fungus enzymes as molecular targets for antifungals was initially performed.47−49 Thus, four enzymes were found to have the highest susceptibility to heterocyclic-containing antifungals, namely, eburicol 14α-demethylase, β-tubulin, cytochrome b, and topoisomerase II.47 However, the crystal structures of the selected targets have not been determined for F. oxysporum. Therefore, we build homology models for the four enzymes. All amino acidic sequence identity (% IDEN) between selected templates and UniProt query proteins was more significant than 50%. This outcome indicates that the selected templates are optimal (i.e., templates with a % IDEN greater than 30% allow for generating more reliable models)50 and, therefore, the homology modeling would be successful. In this regard, the quality results obtained from validating the homology models are presented in Table 4. The global model quality estimate (GMQE) value was also considered an overall model quality parameter, expressed between 0 and 1 (i.e., 1 indicates the highest model reliability).51,52 Our models showed GMQE values close to 1, indicating good reliability of the model construction. On the other hand, the ProSA-web-calculated Z-scores assessed the structure’s total energy deviations concerning an energy distribution derived from random conformations, which indicated an excellent overall quality for all models. The Ramachandran plot evidenced the energetically allowed regions for the dihedral angles of a protein (i.e., a good quality model would be expected to have more than 90% in the most favored regions).53 Our models presented values greater than 90% and showed that most amino acid residues were located in preferred regions (Supporting Information, Table S1). These validation results indicated that the four modeled F. oxysporum enzymes are suitable for subsequent docking studies.

Table 4. Validation of the Models by Homology.

| homology model | PDB template | % IDENa | GMEQb | Ramachandran plotc | Z-scored |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| eburicol 14α-demethylase (FoEDM) | 6CR2-chain A | 66.8 | 0.82 | 90.5% | –9.63 |

| β-tubulin (FoβT) | 5ZXH-chain B | 83.4 | 0.86 | 90.9% | –10.07 |

| cytochrome b (FoCCb) | 1EZV-chain C | 57.8 | 0.78 | 94.6% | –4.05 |

| topoisomerase II (FoTI-II) | 1QZR-chain A, B | 52.7 | 0.76 | 91.3% | –9.25 |

% IDEN: % sequence identity.

GMEQ: global model quality estimation.

Ramachandran plot: energetically allowed regions of a protein (expressed in %).

Z-score: estimates the general quality of the model.

Molecular Docking Studies: Selected F. oxysporum Targets and Schiff Bases

A structure-based virtual screening54 was then conducted through molecular docking and binding free-energy calculations using Glide Standard Precision (SP) mode and molecular mechanics combined with the generalized Born surface area (MM-GBSA), respectively, to discriminate the potential of the synthesized Schiff bases 3a–l as binders for the modeled F. oxysporum targets and their putative binding modes. The respective results are shown in the Supporting Information (Tables S2 and S3). Table 5 shows the results of those Schiff bases with the best affinity values for each test enzyme.

Table 5. Results of Molecular Docking and Binding Free Energies for Schiff Bases.

| receptor | compound | GlideScore | ΔG MM-GBSAa |

|---|---|---|---|

| eburicol 14-α-demethylase | 3g | –7.24 | –46.65 |

| β-tubulin | 3e | –2.77 | –47.07 |

| cytochrome b | 3j | –6.16 | –65.12 |

| topoisomerase II | 3e | –5.70 | –61.86 |

GlideScore was calculated in kcal/mol. The Glide SP visualization module was used to analyze the coupled poses, and the binding free energy (kcal/mol) was calculated using molecular mechanics-generalized Born surface area (MM-GBSA).

Many of the fungicides used are demethylation inhibitors (DMIs), blocking the cytochrome P450-dependent enzyme eburicol 14α-demethylase (CYP51), which is essential for synthesizing ergosterol, a necessary constituent of the plasma membrane of fungi.55 It has been reported that the antifungal activity of many compounds depends on their ability to inhibit the activity of CYP51 enzymes that are part of cytochrome P450.56 In our study, compound 3g exhibited the best binding free energy (−46.65 kcal/mol) and interaction profile with the F. oxysporum eburicol 14α-demethylase (FoEDM), involving hydrophobic contacts with residues Tyr76, Leu79, Phe84, Val89, Met104, Phe183, Phe188, Ala257, Leu258, Met260, Ala261, Ile327, Leu463, and Phe464 (Figures 5a and S1a). In addition, polar-type interactions were also observed with Tyr90, Thr80, His264, and Ser462. Tyr90 interacted with 3g via an H-bonding with the enamine N–H, while Ser462 interacted with the indole N–H. The Phe183 residue presented π–π stacking-type interactions with the indole group. These residues differed from those reported for other heterocyclic antifungals (e.g., azoles),57 indicating a particular binding mode of this Schiff base within the active site of FoEDM.

Figure 5.

Three-dimensional (3D) structures of the best docking poses of ligand–receptor complexes. (a) F. oxysporum eburicol 14α-demethylase (FoEDM)...3g; (b) F. oxysporum β-tubulin (FoβT)...3e; (c) F. oxysporum cytochrome b (FoCCb)...3j; and (d) F. oxysporum topoisomerase II (FoTI-II)...3e. Receptor residues and ligands are sketched in gray lines and black sticks, respectively. Heme group in FoEDM is sketched in green sticks. Relevant interactions between the ligand and receptor per complex are depicted by dashed tubes (light blue = π–π stacking; orange = hydrophobic; yellow = hydrogen bond).

In the case of the F. oxysporum β-tubulin (FoβT), compound 3e exhibited the best binding free energy (−47.07 kcal/mol) and docking outcome. β-tubulin polymerization inhibitor fungicides help induce mitotic arrest by binding to this enzyme.58 The interactions observed between 3e and FoβT showed hydrophobic-type interactions with residues Val236, Cys239, Leu240, Leu246, Leu250, Leu253, Ile316, Ala352, and Ile368 (Figures 5b and S1b). They presented polar-type interactions with residues Thr237, Gln245, Asn247, Ser248, Ans156, Ser314, Gln350, and Thr351. It was observed that the indole nitrogen of 3e presented a H-bonding interaction with Ser314, while Gln550 presented this same interaction with the ester carbonyl group. In addition, residues Asp249 and Lys252 showed electrostatic-type interactions. Compound 3e exhibited interactions with different residues than other antifungals (e.g., methyl benzimidazole carbamates), and such observed interacting residues are not involved in fungicide resistance (e.g., Glu198),59 which is a very positive fact for further development as fungal β-tubulin inhibitors based on this Schiff base.

The cytochrome bc1 complex is a central part of the fungal cellular respiratory chain, one of the agricultural fungicides’ molecular targets. Hence, studies against this complex or parts of it can offer a reasonable control solution by developing new respiratory chain inhibitors.60 In our simulations, compound 3j exhibited the best binding free energy (−65.12 kcal/mol) within the active site of F. oxysporum Cytochrome b (FoCCb). For the 3j...FoCCb complex, residues Tyr132, Met139, Trp142, Va146, Ile147, Leu150, Leu159, Ile270, Val271, Pro272, Leu276, Phe279, Tyr280, Leu283, and Met296 presented hydrophobic-type interactions (Figures 5c and S1c). The residues Glu273 and Arg284 showed electrostatic interactions, while Thr266 presented a polar-type interaction. The Tyr280 residue raised a π–π stacking-type interaction with the indole group’s aromatic ring and an H-bonding with the cyclohexanedione carbonyl group. Compound 3j displayed crucial interacting residues, such as Tyr132, Glu273, and Tyr275, reported for other broad-spectrum fungicides (e.g., quinone outside inhibitors), and a spherical and compact shape, which are key features to favor both Coulomb and van der Waals interactions to bind the target and be effective against nonresistant and resistant fungal pathogens.61

Finally, topoisomerase-inhibiting compounds affect DNA replication and transcription in many phytopathogenic fungi such as F. oxysporum. Both processes are necessary to maintain DNA topology,62 modifying the growth and morphology negatively.63 The best binding free energy (−61.86 kcal/mol) was obtained for compound 3e within the active site of F. oxysporum topoisomerase II (FoTI-II). The resulting 3e...FoTI-II complex formed hydrophobic-type interactions with residues in chains A and B of the enzyme, such as Ile29 (B), Tyr36 (A and B), Leu132 (B), Leu133 (A and B), Tyr152 (A and B), and Leu156 (B) (Figures 5d and S1d). Additionally, other critical polar-type interactions were also observed. For instance, 3e interacted with Gln25 (A, B), His28 (A, B), Thr35 (A, B), Asn150 (A, B), Ser370 (A, B), and Gln371 (A, B) residues. Furthermore, the Tyr36B residue presented a π–π stacking-type interaction with the indole group’s aromatic ring. In contrast, the Gln371B residue showed an H-bonding with the ester carbonyl group. These interactions have also been observed in other antibiotics and antifungals to favor the target binding.64

Molecular Dynamics Simulations: Selected F. oxysporum Targets and Best-Docked Schiff Bases

Trajectories of the best-docked ligand–receptor complexes were monitored through the geometric properties during a 100 ns molecular dynamics (MD) simulation. Hence, the structural stability of the receptor was evaluated by measuring the time-dependent distance between different positions (in Å) of the set of atoms through the root-mean-square deviations (RMSDs).65 The results indicated that all evaluated complexes have stable trajectories throughout the simulation time with average fluctuations of 1–3 Å. The protein FoEDM showed fluctuations between the first 5 ns with an RMSD of 0.4 Å. In comparison, the FoEMD...3g complex showed an RMSD of 0.6 Å that was maintained throughout the MD simulation (Figure 6a). The interaction analysis (Figure S2a) showed that hydrophobic interactions are the most frequent throughout the simulation, with residues Tyr76, Phe84, Phe183 Ala275, and Phe464. Hydrogen bond-type interactions were also observed with residues Tyr90 and Ser462. Fluctuations for the FoβT protein were observed at 10 ns with an RMSD of 0.45 Å, maintained throughout the MD simulation. The FoβT...3e complex showed three fluctuations between 18 and 45 ns with an RMSD of 2.5 Å but stabilized at the MD simulation ending (Figure 6b). The interaction analysis led to observing that the residues Cys239 and Leu253 presented hydrophobic interactions. Ser314 showed hydrogen bond-type interactions, while the Gln245, Asn256, and Gln350 residues showed hydrogen bond-type interactions and those mediated by water bridges (Figure S2b). On the other hand, FoCCb fluctuated around 5 and 50 ns with an RMSD of 0.4 Å, while the ligand–protein complex had an RMSD value of 0.5 Å. Both stabilize throughout the rest of the MD simulation (Figure 6c). The most frequent interactions during the simulation are hydrophobic contacts (Figure S2c). FoTI-II fluctuated around 5 ns with an RMSD value of 1 Å, and FoTI-II...3e showed fluctuations between 10 and 70 ns with an RMSD value of 1.6 Å but stabilized at the MD simulation ending (Figure 6d). The interaction analysis showed that hydrophobic contacts are the most frequent interactions (Figure S2d). These RMSD profiles indicated that the best-docked Schiff bases can stabilize the modeled enzymes after 50 ns, although the best outcome was achieved for FoEDM...3g and FoCCb...3j complexes, involving hydrophobic interactions as the main driving force for the molecular recognition of these enzymes by 3g and 3j as binders.

Figure 6.

RMSD plots after molecular dynamics simulations for the test protein...ligand complexes. (a) F. oxysporum eburicol 14α-demethylase (FoEDM)...3g; (b) F. oxysporum β-tubulin (FoβT)...3e; (c) F. oxysporum cytochrome b (FoCCb)...3j; and (d) F. oxysporum topoisomerase II (FoTI-II)...3e. αβ.

Conclusions

We developed a high-yielding and green synthesis of novel Schiff bases derived from l-tryptophan and 1,3-dicarbonyl compounds, obtained easily and efficiently in good overall yields after two steps (65–89%). The 1D and 2D NMR experiments established that enamine tautomer is favored, evidencing a tautomeric shift in the liquid phase. FT-IR and DFT calculations suggested that these tautomers are also predominant in solid and gas phases. Still, their formation is strongly affected by the presence of electronic and steric hindrance features and the formation of an intramolecular H-bonding interaction. Additionally, compounds 3a–l exhibited an in vitro antifungal activity at different levels, including IC50 values of active compounds within the 0.60–3.86 mM range. The SA trend suggested that bulky groups at ester and enamine moieties of this compound set negatively influenced their antifungal activity against F. oxysporum. Finally, molecular docking and MM-GBSA binding energy calculations showed a strong binding behavior between certain Schiff bases and the selected proteins involved in the vital processes of F. oxysporum. The molecular docking analysis was extended by the results of the 100 ns MD simulations. This analysis showed that the ligand–protein complexes have good stability with RMSD values within the allowed range. Therefore, these results will be helpful in the future for the design of new antifungals based on the Schiff base driven from l-tryptophan.

Materials and Methods

General Information

Compounds 3a–l were purified by standard techniques. The synthesized compounds were purified by flash chromatography using silica gel 60 (230–400 mesh) and petroleum ether (40:60): ethyl acetate as the mobile phase. The purity of the compounds was checked by thin-layer chromatography performed with Merck Silica Gel 60 F254 aluminum sheets. Spots were detected by their absorption under UV light (254 nm). Uni- and bidimensional NMR experiments were recorded on a BRUKER Avance III HD Ascend 400 spectrometer using CDCl3 as the solvent with tetramethylsilane (TMS) as an internal standard at room temperature. Chemical shifts are given in δ (ppm) relative to TMS, and the coupling constants J are given in hertz (Hz). Liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC/MS) experiments were performed on an LCMS 2020 spectrometer (Shimadzu, Columbia, MD), comprising a Prominence high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) system coupled to a single quadrupole analyzer with electrospray ionization (ESI). A Synergi column (150 × 4.6 mm, 4.0 μm) was used for analysis at 0.6 mL/min using mixtures of acetonitrile (A) and 1% formic acid (B) in gradient elution. ESI was operated simultaneously in positive and negative ion modes (scan 100–2000 m/z), a desolvation line temperature at 250 °C, nitrogen as a nebulizer gas at 1.5 L/min, a drying gas at 8 L/min, and a detector voltage at 1.4 kV. Accurate mass data were recorded by high-resolution MS (HRMS) on a micrOTOF-Q II mass spectrometer (Bruker, Billerica, MA). ESI was also operated in positive and negative ion modes (scan 100–2000 m/z), a desolvation line temperature at 250 °C, nitrogen as a nebulizer gas at 1.5 L/min, a drying gas at 8 L/min, a quadrupole energy at 7.0 eV, and a collision energy 14 eV. The sign of the optical specific rotations for all of the compounds was determined with a Jasco P-2000 Polarimeter (JASCO Co., Ltd., Mary’s Court, PA) in a quartz cell (1.0 cm), and the value is an average of 10 measures.

General Procedure for the Synthesis of Compounds 3a–l

Compounds 1a–d were prepared based on the methodology previously reported in the literature.43l-Tryptophan (1 mmol) was mixed with trimethylsilyl chloride (3 mmol) in 10 mL of the desired alcohol (ROH, R = Me, Et, i-Pr, n-Bu). The mixture was heated under reflux conditions for 4 h. The reaction crude was distilled at a reduced pressure until dryness, affording in situ compound 1. Then, a mixture of TEA (2 mmol) and 1,3-dicarbonyl compound 2 (1 mmol) in the respective alcohol was added to the crude compound 1, heated under reflux conditions during 20–30 h. The reaction progress was monitored by thin-layer chromatography until the reagents were not detected. The solvent was then removed by vacuum distillation. The residue was purified by flash column chromatography eluting with petroleum ether/ethyl acetate (70:30) to give pure products 3a–l. Yields for each compound are reported in Table 1. Spectroscopic data for the characterization of compounds 3a–l are presented in the Supporting Information.

DFT-B3LYP Calculations

All of the theoretical calculations were performed using the Gaussian package.66 The geometric structure of the compounds 3a–l was fully optimized without imposing any symmetry constraint with Becke’s three-parameter hybrid functional with the Lee–Yang–Parr correlation functional (B3LYP) at the level 6-311+G**(d,p).

Antifungal Assay

Compounds 3a–l were assessed against F. oxysporum following the previously reported 12-well plate amended-medium method to evaluate the in vitro inhibition of mycelial growth.46 IC50 values were calculated from log(doses) versus mycelial growth inhibition curves through nonlinear regression using GraphPad Prism 9.0 for Windows.

Homology Modeling of F. oxysporum Molecular Targets

The selection of F. oxysporum molecular targets was made according to literature reports regarding the action mechanism of some fungicides by functional groups.67−69 Based on this survey, four receptors were selected to involve vital pathogen processes and, therefore, considered as crucial molecular targets to be explored: eburicol 14-α demethylase, β-tubulin, cytochrome b, and topoisomerase II. The F. oxysporum sequence search was performed using UniProt and NCBI database. Then, homologous proteins were identified by BLAST. Suitable molecular templates were downloaded from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) database, considering crystal resolution and interactions of cocrystallized ligands with key residues. Sequence editing was done with BioEdit v 7.2.5.70 Sequence alignment was done with Unipro UGENE v. 36 and Clustal W algorithm.71 Homology models were built with the SWISS-MODEL server.51 PROCHECK53 and ProSA-web72 servers were used to validate the stereochemical and energetic quality of the models by homology.

Protein Preparation and Grid Generation

The Protein Preparation Wizard module of the Schrödinger suite was used to prepare the homology models. The structures were processed by removing water molecules, adding hydrogen atoms, and filling the chains and loops. Model refinement was done by energy-minimizing the structures employing the OPLS3 force field.72 The active sites for each of the targets were obtained from the published literature.73−76 Grid boxes were centered at reported binding sites for each target. Outer box edges were set to 30Å, thus resulting in a box volume of 30 × 30 × 30 Å for all of the enzymes.

Structural Optimization of Schiff Bases

All ligands were sketched with the Maestro Suite and prepared with the LigPrep module (Schrödinger 2017). Ligand energy minimization was performed using the OPLS3 force field.77

Molecular Docking and Binding Free-Energy Calculation

Molecular docking calculations were performed with the Glide software, using the Glide Standard Precision (SP) mode, which uses a series of hierarchical filters to find the best ligand binding poses in a space within the protein binding site, previously mapped and constructed (grid box).78 The filters included a systematic search approach, which samples the ligands for a positional, conformational, and orientational space before evaluating the energetic interactions with the protein.79 Default docking parameters were used, and the top-10 docking solutions (according to the glide score) for each ligand were kept for the postdocking process.80 In addition, the scope of the employed docking protocol was also assessed through redocking using the cocrystallized ligands, retrieved from the starting templates used for the homology model building. Thus, the cocrystallized ligands were deeply minimized and, subsequently, docked using the same Glide-based protocol. The differences between cocrystallized and redocked ligands were found to be reasonable (RMSD < 1), indicating that the employed docking protocol was suitable to discriminate binders. Finally, all docking solutions were rescored using MM-GBSA (molecular mechanics combined with the generalized Born surface area) to calculate the binding free energy for each of the studied compounds with higher precision. This rescoring allows a more reliable pose ranked. The implementation of MM-GBSA was done with the Prime module from Schrodinger.

Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations

MD simulations were analyzed only for the ligand with the best-docked complex possessing the best MM-GBSA-derived binding free energy. It was carried out in Desmond81 and was implemented as the next step to expand the information on the binding mode between the ligand and the protein over time. First, the system was solvated with the simple point charge (CP) water model in an orthorhombic box. Next, the system was neutralized with Na+ or Cl– ions. The final concentration of NaCl was set at 0.15 M. The default relaxation Desmond protocol was applied, applying a spring constant of kcal × mol–1 × Å–2 to the atoms of the protein backbone during 20 ns. Then, the simulations were extended other 100 ns without restrictions. The integration of the motion equations was performed using an NPT ensemble with a time step of 2 fs. The Martyna–Tobias–Klein barostat method was used to keep the pressure constant at 1 atm with a relaxation time of 2 ps. The temperature was kept constant at 300 K, using the Nose–Hoover thermostat method with a relaxation time of 1 ps. Trajectories were monitored using geometric properties throughout the simulation time; the most common measure of these deviations or structural fluctuations over time is made by calculating the square root of the mean deviations (RMSD), which helps evaluate the structural stability of the receptor by measuring the time-dependent distance between the different positions (Å) of the set of atoms. The VMD82 and Desmond software were used to visualize and analyze MD trajectories.

Acknowledgments

The present work is a product derived from the project IMP-CIAS-2294 funded by Vicerrectoría de Investigaciones at UMNG-Validity 2018. The authors thank the RamirezLab research group of the Universidad de Concepción (Chile) for the use of the computational platform.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- DFT

density functional theory

- B3LYP

Becke, 3-parameter, Lee–Yang–Parr

- NMR

nuclear magnetic resonance

- THF

tetrahydrofuran

- TEA

triethylamine

- COSY

correlated spectroscopy

- HSQC

heteronuclear single quantum coherence

- HMBC

heteronuclear multiple bond correlation

- NOESY

nuclear Overhauser effect spectroscopy

- MD

molecular dynamics

- FoEDM

eburicol 14α-demethylase

- FoβT

β-tubulin

- FoCCb

cytochrome b

- FoTI-II

topoisomerase II

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.2c02614.

Characterization data for compounds 3a–l, molecular docking, and molecular dynamics results (PDF)

Author Contributions

The manuscript was written with the contributions of all authors. D.Q. and E.C.-B. designed the research and revised the manuscript; P.B.-M., L.D.B., and F.O. performed the synthesis and characterization of the products. D.Q. performed DFT/B3LYP calculations; P.B.-M. determined the antifungal activity of the products against F. oxysporum and performed molecular docking and dynamics simulations. All authors analyzed the data and read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have approved the final version of the manuscript.

This research received no external funding.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Ma L.-J.; Geiser D. M.; Proctor R. H.; Rooney A. P.; O’Donnell K.; Trail F.; Gardiner D. M.; Manners J. M.; Kazan K. Fusarium Pathogenomics. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2013, 67, 399–416. 10.1146/annurev-micro-092412-155650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean R.; Van Kan J. A. L.; Pretorius Z. A.; Hammond-Kosack K. E.; Di Pietro A.; Spanu P. D.; Rudd J. J.; Dickman M.; Kahmann R.; Ellis J.; Foster G. D. The Top 10 Fungal Pathogens in Molecular Plant Pathology. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2012, 13, 414–430. 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2011.00783.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okolle N. J. Alternatives to Synthetic Pesticides for the Management of the Banana Borer Weevil (Cosmopolites Sordidus) (Coleoptera: Curculioniidae). CAB Rev. 2020, 15, 1–24. 10.1079/PAVSNNR202015026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aktar W.; Sengupta D.; Chowdhury A. Impact of Pesticides Use in Agriculture: Their Benefits and Hazards. Interdiscip. Toxicol. 2009, 2, 1–12. 10.2478/v10102-009-0001-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cedergreen N.; Dalhoff K.; Li D.; Gottardi M.; Kretschmann A. C. Can Toxicokinetic and Toxicodynamic Modeling Be Used to Understand and Predict Synergistic Interactions between Chemicals?. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 14379–14389. 10.1021/acs.est.7b02723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iftikhar S.; Bengyella L.; Shahid A. A.; Nawaz K.; Anwar W.; Khan A. A. Discovery of Succinate Dehydrogenase Candidate Fungicides via Lead Optimization for Effective Resistance Management of F. oxysporumf. Sp. Capsici. 3 Biotech 2022, 12, 102 10.1007/s13205-022-03157-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicolopoulou-Stamati P.; Maipas S.; Kotampasi C.; Stamatis P.; Hens L. Chemical Pesticides and Human Health: The Urgent Need for a New Concept in Agriculture. Front. Public Health 2016, 4, 148 10.3389/fpubh.2016.00148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lilai S. A.; Kapinga F. A.; Nene W. A.; Mbasa W. V.; Tibuhwa D. D. The Efficacy of Biofungicides on Cashew Wilt Disease Caused by Fusarium oxysporum. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2022, 163, 453–465. 10.1007/s10658-022-02489-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mejía C.; Farfán D.; Montaña J. S.; Restrepo S.; Jiménez P.; Danies G.; Rodríguez-Bocanegra M. X. Acibenzolar-S-Methyl Induces Protection against the Vascular Wilt Pathogen Fusarium oxysporum in Cape Gooseberry (Physalis Peruviana L.). J. Plant Dis. Prot. 2021, 128, 449–456. 10.1007/s41348-021-00427-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno-Velandia C. A.; Ongena M.; Cotes A. M. Effects of Fengycins and Iturins on Fusarium oxysporum f. Sp. Physali and Root Colonization by Bacillus Velezensis Bs006 Protect Golden Berry Against Vascular Wilt. Phytopathology 2021, 111, 2227–2237. 10.1094/PHYTO-01-21-0001-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AL-Shammri K. N.; Elkanzi N. A. A.; Arafa W. A. A.; Althobaiti I. O.; Bakr R. B.; Moustafa S. M. N. Novel Indan-1,3-Dione Derivatives: Design, Green Synthesis, Effect against Tomato Damping-off Disease Caused by Fusarium oxysporum and in Silico Molecular Docking Study. Arab. J. Chem. 2022, 15, 103731 10.1016/j.arabjc.2022.103731. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Massey K. A.; Blakeslee C. H.; Pitkow H. S. A Review of Physiological and Metabolic Effects of Essential Amino Acids. Amino Acids 1998, 14, 271–300. 10.1007/BF01318848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jastrzębowska K.; Gabriel I. Inhibitors of Amino Acids Biosynthesis as Antifungal Agents. Amino Acids 2015, 47, 227–249. 10.1007/s00726-014-1873-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alcazar-Fuoli L. Amino Acid Biosynthetic Pathways as Antifungal Targets for Fungal Infections. Virulence 2016, 7, 376–378. 10.1080/21505594.2016.1169360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemantha H. P.; Sureshbabu V. V. A Simple Approach for the Synthesis of New Classes of Dithiocarbamate-Linked Peptidomimetics. Tetrahedron Lett. 2009, 50, 7062–7066. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2009.09.172. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boussalah N.; Touzani R.; Souna F.; Himri I.; Bouakka M.; Hakkou A.; Ghalem S.; Kadiri S. El. Antifungal Activities of Amino Acid Ester Functional Pyrazolyl Compounds against Fusarium oxysporum f.Sp. Albedinis and Saccharomyces Cerevisiae Yeast. J. Saudi Chem. Soc. 2013, 17, 17–21. 10.1016/j.jscs.2011.02.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boraei A. T. A.; El Tamany E. S. H.; Ali I. A. I.; Gebriel S. M. Antimicrobial Evaluation of New Quinoxaline Derivatives Synthesized by Selective Coupling with Alkyl Halides and Amino Acids Esters. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 2017, 54, 2881–2888. 10.1002/jhet.2896. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kajal A.; Bala S.; Kamboj S.; Sharma N.; Saini V. Schiff Bases: A Versatile Pharmacophore. J. Catal. 2013, 2013, 1–14. 10.1155/2013/893512. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Qin W.; Long S.; Panunzio M.; Biondi S. Schiff Bases: A Short Survey on an Evergreen Chemistry Tool. Molecules 2013, 18, 12264–12289. 10.3390/molecules181012264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborti A. K.; Bhagat S.; Rudrawar S. Magnesium Perchlorate as an Efficient Catalyst for the Synthesis of Imines and Phenylhydrazones. Tetrahedron Lett. 2004, 45, 7641–7644. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2004.08.097. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bhagat S.; Sharma N.; Chundawat T. S. Synthesis of Some Salicylaldehyde-Based Schiff Bases in Aqueous Media. J. Chem. 2013, 2013, 1–4. 10.1155/2013/909217. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Parsaee Z.; Joukar Bahaderani E.; Afandak A. Sonochemical Synthesis, in Vitro Evaluation and DFT Study of Novel Phenothiazine Base Schiff Bases and Their Nano Copper Complexes as the Precursors for New Shaped CuO-NPs. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2018, 40, 629–643. 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2017.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur G.; Sharma S.; Kaur P.; Gaba J. Synthesis of Some Schiff Bases of o-Phenylenediamine and Their Antimicrobial Activity. Pestic. Res. J. 2019, 31, 74–80. 10.5958/2249-524X.2019.00008.6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hejchman E.; Kruszewska H.; Maciejewska D.; Sowirka-Taciak B.; Tomczyk M.; Sztokfisz-Ignasiak A.; Jankowski J.; Młynarczuk-Biały I. Design, Synthesis, and Biological Activity of Schiff Bases Bearing Salicyl and 7-Hydroxycoumarinyl Moieties. Monatsh. Chem. 2019, 150, 255–266. 10.1007/s00706-018-2325-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Murtaza S.; Akhtar M. S.; Kanwal F.; Abbas A.; Ashiq S.; Shamim S. Synthesis and Biological Evaluation of Schiff Bases of 4-Aminophenazone as an Anti-Inflammatory, Analgesic and Antipyretic Agent. J. Saudi Chem. Soc. 2017, 21, S359–S372. 10.1016/j.jscs.2014.04.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pandey A. K.; Kashyap P. P.; Kaur C. D. Anti-Inflammatory Activity of Novel Schiff Bases by in Vitro Models. Bangladesh J. Pharmacol. 2017, 12, 41–43. 10.3329/bjp.v12i1.29675. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sondhi S. M.; Singh N.; Kumar A.; Lozach O.; Meijer L. Synthesis, Anti-Inflammatory, Analgesic and Kinase (CDK-1, CDK-5 and GSK-3) Inhibition Activity Evaluation of Benzimidazole/Benzoxazole Derivatives and Some Schiff’s Bases. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2006, 14, 3758–3765. 10.1016/j.bmc.2006.01.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alam S.; Khan F. Virtual Screening, Docking, ADMET and System Pharmacology Studies on Garcinia Caged Xanthone Derivatives for Anticancer Activity. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 5524 10.1038/s41598-018-23768-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salem M. A.; Ragab A.; El-Khalafawy A.; Makhlouf A. H.; Askar A. A.; Ammar Y. A. Design, Synthesis, in Vitro Antimicrobial Evaluation and Molecular Docking Studies of Indol-2-One Tagged with Morpholinosulfonyl Moiety as DNA Gyrase Inhibitors. Bioorg. Chem. 2020, 96, 103619 10.1016/j.bioorg.2020.103619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rather B.; Paneersalvam P.; Raj T.; Ishar M. P. S.; Singh B.; Sharma V. Anticonvulsant Activity of Schiff Bases of 3-Amino-6,8-Dibromo-2-Phenyl-Quinazolin-4(3H)-Ones. Indian J. Pharm. Sci. 2010, 72, 375–378. 10.4103/0250-474X.70488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandey S.; Srivastava R. S. Synthesis and Characterization of Some Heterocyclic Schiff Bases: Potential Anticonvulsant Agents. Med. Chem. Res. 2011, 20, 1091–1101. 10.1007/s00044-010-9441-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aboul-Fadl T.; Mohammed F. A.-H.; Hassan E. A.-S. Synthesis, Antitubercular Activity and Pharmacokinetic Studies of Some Schiff Bases Derived from 1- Alkylisatin and Isonicotinic Acid Hydrazide (Inh). Arch. Pharm. Res. 2003, 26, 778–784. 10.1007/BF02980020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali S. M. M.; Azad M. A. K.; Jesmin M.; Ahsan S.; Rahman M. M.; Khanam J. A.; Islam M. N.; Shahriar S. M. S. In Vivo Anticancer Activity of Vanillin Semicarbazone. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 2012, 2, 438–442. 10.1016/S2221-1691(12)60072-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y.; Mi Y.; Li Q.; Dong F.; Guo Z. Synthesis of Schiff Bases Modified Inulin Derivatives for Potential Antifungal and Antioxidant Applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 143, 714–723. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.09.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakır T. K.; Lawag J. B. Preparation, Characterization, Antioxidant Properties of Novel Schiff Bases Including 5-Chloroisatin-Thiocarbohydrazone. Res. Chem. Intermed. 2020, 46, 2541–2557. 10.1007/s11164-020-04105-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Patil S. A.; Prabhakara C. T.; Halasangi B. M.; Toragalmath S. S.; Badami P. S. DNA Cleavage, Antibacterial, Antifungal and Anthelmintic Studies of Co(II), Ni(II) and Cu(II) Complexes of Coumarin Schiff Bases: Synthesis and Spectral Approach. Spectrochim. Acta, Part A 2015, 137, 641–651. 10.1016/j.saa.2014.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang B.; Liu Y.; Wang Z.; Li Y.; Wang Q. Antiviral Activity and Mechanism of Gossypols: Effects of the O2– Production Rate and the Chirality. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 10266–10277. 10.1039/C6RA28625A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wei L.; Tan W.; Zhang J.; Mi Y.; Dong F.; Li Q.; Guo Z. Synthesis, Characterization, and Antifungal Activity of Schiff Bases of Inulin Bearing Pyridine Ring. Polymers 2019, 11, 371 10.3390/polym11020371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei L.; Tan W.; Wang G.; Li Q.; Dong F.; Guo Z. The Antioxidant and Antifungal Activity of Chitosan Derivatives Bearing Schiff Bases and Quaternary Ammonium Salts. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019, 226, 115256 10.1016/j.carbpol.2019.115256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei L.; Zhang J.; Tan W.; Wang G.; Li Q.; Dong F.; Guo Z. Antifungal Activity of Double Schiff Bases of Chitosan Derivatives Bearing Active Halogeno-Benzenes. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 179, 292–298. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2021.02.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y.; Mi Y.; Sun X.; Zhang J.; Li Q.; Ji N.; Guo Z. Novel Inulin Derivatives Modified with Schiff Bases: Synthesis, Characterization, and Antifungal Activity. Polymers 2019, 11, 998 10.3390/polym11060998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X. L.; Niu H. Y.; Zhang S. X.; Cai Y. Q. Preparation of a Chitosan-Coated C<inf>18</Inf>-Functionalized Magnetite Nanoparticle Sorbent for Extraction of Phthalate Ester Compounds from Environmental Water Samples. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2010, 397, 791–798. 10.1007/s00216-010-3592-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J.; Sha Y. A Convenient Synthesis of Amino Acid Methyl Esters. Molecules 2008, 13, 1111–1119. 10.3390/molecules13051111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basa P. N.; Bhowmick A.; Schulz M. M.; Sykes A. G. Site-Selective Imination of an Anthracenone Sensor: Selective Fluorescence Detection of Barium(II). J. Org. Chem. 2011, 76, 7866–7871. 10.1021/jo2013143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalmykov P. A.; Khodov I. A.; Klochkov V. V.; Klyuev M. V. Theoretical and Experimental Study of Imine-Enamine Tautomerism of Condensation Products of Propanal with 4-Aminobenzoic Acid in Ethanol. Russ. Chem. Bull. 2017, 66, 70–75. 10.1007/s11172-017-1701-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marentes-Culma R.; Orduz-Díaz L.; Coy-Barrera E. Targeted Metabolite Profiling-Based Identification of Antifungal 5-n-Alkylresorcinols Occurring in Different Cereals against Fusarium oxysporum. Molecules 2019, 24, 770 10.3390/molecules24040770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazu T.; Bricker B.; Flores-Rozas H.; Ablordeppey S. The Mechanistic Targets of Antifungal Agents: An Overview. Mini-Rev. Med. Chem. 2016, 16, 555–578. 10.2174/1389557516666160118112103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma C.; Chowdhary A. Molecular Bases of Antifungal Resistance in Filamentous Fungi. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2017, 50, 607–616. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2017.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odds F. C.; Brown A. J. P.; Gow N. A. R. Antifungal Agents: Mechanisms of Action. Trends Microbiol. 2003, 11, 272–279. 10.1016/S0966-842X(03)00117-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forrest L. R.; Tang C. L.; Honig B. On the Accuracy of Homology Modeling and Sequence Alignment Methods Applied to Membrane Proteins. Biophys. J. 2006, 91, 508–517. 10.1529/biophysj.106.082313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waterhouse A.; Bertoni M.; Bienert S.; Studer G.; Tauriello G.; Gumienny R.; Heer F. T.; De Beer T. A. P.; Rempfer C.; Bordoli L.; Lepore R.; Schwede T. SWISS-MODEL: Homology Modelling of Protein Structures and Complexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, W296–W303. 10.1093/nar/gky427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biasini M.; Bienert S.; Waterhouse A.; Arnold K.; Studer G.; Schmidt T.; Kiefer F.; Cassarino T. G.; Bertoni M.; Bordoli L.; Schwede T. SWISS-MODEL: Modelling Protein Tertiary and Quaternary Structure Using Evolutionary Information. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42, 252–258. 10.1093/nar/gku340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laskowski R. A.; MacArthur M. W.; Moss D. S.; Thornton J. M. PROCHECK: A Program to Check the Stereochemical Quality of Protein Structures. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 1993, 26, 283–291. 10.1107/s0021889892009944. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q.; Shah S.. Structure-Based Virtual Screening. In Protein Bioinformatics. Methods in Molecular Biology, Wu C.; Arighi C.; Ross K., Eds.; Humana Press: New York, NY, 2017; Vol. 1558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liaras K.; Soković M.. Synthetic Antifungal Compounds. In Antifungal Compounds Discovery; Elsevier, 2021; pp 167–262. 10.1016/b978-0-12-815824-1.00005-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sagatova A. A.; Keniya M. V.; Wilson R. K.; Monk B. C.; Tyndall J. D. A. Structural Insights into Binding of the Antifungal Drug Fluconazole to Saccharomyces Cerevisiae Lanosterol 14α-Demethylase. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2015, 59, 4982–4989. 10.1128/AAC.00925-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosam K.; Monk B. C.; Lackner M. Sterol 14α-Demethylase Ligand-Binding Pocket-Mediated Acquired and Intrinsic Azole Resistance in Fungal Pathogens. J. Fungi 2021, 7, 1. 10.3390/jof7010001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X.; Zhang P.; Perez-Rodriguez V.; Souders C. L.; Martyniuk C. J. Assessing the Toxicity of the Benzamide Fungicide Zoxamide in Zebrafish (Danio Rerio): Towards an Adverse Outcome Pathway for Beta-Tubulin Inhibitors. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2020, 78, 103405 10.1016/j.etap.2020.103405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vela-Corcía D.; Romero D.; de Vicente A.; Pérez-García A. Analysis of β-Tubulin-Carbendazim Interaction Reveals That Binding Site for MBC Fungicides Does Not Include Residues Involved in Fungicide Resistance. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 7161 10.1038/s41598-018-25336-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang F.; Li H.; Wang L.; Yang W. C.; Wu J. W.; Yang G. F. Design, Syntheses, and Kinetic Evaluation of 3-(Phenylamino)Oxazolidine-2, 4-Diones as Potent Cytochrome Bc1 Complex Inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2011, 19, 4608–4615. 10.1016/j.bmc.2011.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arakawa A.; Kasai Y.; Yamazaki K.; Iwahashi F. Features of Interactions Responsible for Antifungal Activity against Resistant Type Cytochrome Bc1: A Data-Driven Analysis Based on the Binding Free Energy at the Atomic Level. PLoS One 2018, 13, e0207673 10.1371/journal.pone.0207673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarolim K.; Del Favero G.; Ellmer D.; Stark T. D.; Hofmann T.; Sulyok M.; Humpf H.-U.; Marko D. Dual Effectiveness of Alternaria but Not Fusarium Mycotoxins against Human Topoisomerase II and Bacterial Gyrase. Arch. Toxicol. 2017, 91, 2007–2016. 10.1007/s00204-016-1855-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen L. L.; Fostel J. M. DNA Topoisomerase Inhibitors as Antifungal Agents. Adv. Pharmacol. 1994, 29, 227–244. 10.1016/S1054-3589(08)61140-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jadhav A. K.; Karuppayil S. M. Topoisomerase II as a Target for Repurposed Antibiotics in Candida Albicans: An in Silico Study. In Silico Pharmacol. 2021, 9, 24 10.1007/s40203-021-00082-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angarita-Rodríguez A.; Quiroga D.; Coy-Barrera E. Indole-Containing Phytoalexin-Based Bioisosteres as Antifungals: In Vitro and in Silico Evaluation against Fusarium oxysporum. Molecules 2020, 25, 45 10.3390/molecules25010045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisch M. J.; Trucks G. W.; Schlegel H. B.; Scuseria G. E.; Robb M. A.; Cheeseman J. R.; Scalmani G.; Barone V.; Mennucci B.; Petersson G. A.;et al. Gaussian 09, revision, A.02; Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford, CT, USA, 2009.

- Edel-Hermann V.; Lecomte C. Current Status of Fusarium oxysporum Formae Speciales and Races. Phytopathology 2019, 109, 512–530. 10.1094/PHYTO-08-18-0320-RVW. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ngowi A. V. F.; Mbise T. J.; Ijani A. S. M.; London L.; Ajayi O. C. Smallholder Vegetable Farmers in Northern Tanzania: Pesticides Use Practices, Perceptions, Cost and Health Effects. Crop Prot. 2007, 26, 1617–1624. 10.1016/j.cropro.2007.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louca Christodoulou D.; Kanari P.; Kourouzidou O.; Constantinou M.; Hadjiloizou P.; Kika K.; Constantinou P. Pesticide Residues Analysis in Honey Using Ethyl Acetate Extraction Method: Validation and Pilot Survey in Real Samples. Int. J. Environ. Anal. Chem. 2015, 95, 894–910. 10.1080/03067319.2015.1070408. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hall T. A.BioEdit: A User-Friendly Biological Sequence Alignment Editor and Analysis Program for Windows 95/98/NT, Nucleic Acids Symposium Series; Information Retrieval Ltd: London, 1999; Vol. 41, pp 95–98. [Google Scholar]

- Okonechnikov K.; Golosova O.; Fursov M. Unipro UGENE: A Unified Bioinformatics Toolkit. Bioinformatics 2012, 28, 1166–1167. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos P.; Lopez-Vallejo F.; Ramírez D.; Caballero J.; Mata Espinosa D.; Hernández-Pando R.; Soto C. Y. Identification of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis CtpF as a Target for Designing New Antituberculous Compounds. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2020, 28, 115256 10.1016/j.bmc.2019.115256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friggeri L.; Hargrove T. Y.; Wawrzak Z.; Blobaum A. L.; Rachakonda G.; Lindsley C. W.; Villalta F.; Nes W. D.; Botta M.; Guengerich F. P.; Lepesheva G. I. Sterol 14α-Demethylase Structure-Based Design of VNI ((R)-N-(1-(2,4-Dichlorophenyl)-2-(1H-Imidazol-1-Yl)Ethyl)-4-(5-Phenyl-1,3,4-Oxadiazol-2-Yl)Benzamide)) Derivatives To Target Fungal Infections: Synthesis, Biological Evaluation, and Crystallograph. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 61, 5679–5691. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.8b00641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z.; Ma L.; Wu C.; Meng T.; Ma L.; Zheng W.; Yu Y.; Chen Q.; Yang J.; Shen J. The Structure of MT189-Tubulin Complex Provides Insights into Drug Design. Lett. Drug Des. Discovery 2019, 16, 1069–1073. 10.2174/1570180816666181122122655. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Esser L.; Zhou F.; Zhou Y.; Xiao Y.; Tang W.; Yu C.-A.; Qin Z.; Xia D. Hydrogen Bonding to the Substrate Is Not Required for Rieske Iron-Sulfur Protein Docking to the Quinol Oxidation Site of Complex III. J. Biol. Chem. 2016, 291, 25019–25031. 10.1074/jbc.M116.744391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Classen S.; Olland S.; Berger J. M. Structure of the Topoisomerase II ATPase Region and Its Mechanism of Inhibition by the Chemotherapeutic Agent ICRF-187. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2003, 100, 10629–10634. 10.1073/pnas.1832879100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tripathi M. K.; Sharma P.; Tripathi A.; Tripathi P. N.; Srivastava P.; Seth A.; Shrivastava S. K. Computational Exploration and Experimental Validation to Identify a Dual Inhibitor of Cholinesterase and Amyloid-Beta for the Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Comput.-Aided Mol. Des. 2020, 34, 983–1002. 10.1007/s10822-020-00318-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friesner R. A.; Banks J. L.; Murphy R. B.; Halgren T. A.; Klicic J. J.; Mainz D. T.; Repasky M. P.; Knoll E. H.; Shelley M.; Perry J. K.; Shaw D. E.; Francis P.; Shenkin P. S. Glide: A New Approach for Rapid, Accurate Docking and Scoring. 1. Method and Assessment of Docking Accuracy. J. Med. Chem. 2004, 47, 1739–1749. 10.1021/jm0306430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernández-Rodríguez M.; Rosales-Hernández M.; Mendieta-Wejebe J.; Martínez-Archundia M.; Correa Basurto J. Current Tools and Methods in Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations for Drug Design. Curr. Med. Chem. 2016, 23, 3909–3924. 10.2174/0929867323666160530144742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez D.; Caballero J. Is It Reliable to Take the Molecular Docking Top Scoring Position as the Best Solution without Considering Available Structural Data?. Molecules 2018, 23, 1038 10.3390/molecules23051038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowers K. J.; Chow D. E.; Xu H.; Dror R. O.; Eastwood M. P.; Gregersen B. A.; Klepeis J. L.; Kolossvary I.; Moraes M. A.; Sacerdoti F. D.; Salmon J. K.; Shan Y.; Shaw D. E. In Scalable Algorithms for Molecular Dynamics Simulations on Commodity Clusters, ACM/IEEE SC 2006 Conference (SC’06); IEEE, 2006; pp 43–43. [Google Scholar]

- Humphrey W.; Dalke A.; Schulten K. VMD: Visual Molecular Dynamics. J. Mol. Graphics 1996, 14, 33–38. 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.