ABSTRACT

Yes-associated protein 1 (YAP1) is indispensable for the development of mutant KRAS-driven pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC). High YAP1 mRNA is a prognostic marker for worse overall survival in patient samples; however, the regulatory mechanisms that mediate its overexpression are not well understood. YAP1 genetic alterations are rare in PDAC, suggesting that its dysregulation is likely not due to genetic events. HuR is an RNA-binding protein whose inhibition impacts many cancer-associated pathways, including the “conserved YAP1 signature” as demonstrated by gene set enrichment analysis. Screening publicly available and internal ribonucleoprotein immunoprecipitation (RNP-IP) RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) data sets, we discovered that YAP1 is a high-confidence target, which was validated in vitro with independent RNP-IPs and 3′ untranslated region (UTR) binding assays. In accordance with our RNA sequencing analysis, transient inhibition (e.g., small interfering RNA [siRNA] and small-molecular inhibition) and CRISPR knockout of HuR significantly reduced expression of YAP1 and its transcriptional targets. We used these data to develop a HuR activity signature (HAS), in which high expression predicts significantly worse overall and disease-free survival in patient samples. Importantly, the signature strongly correlates with YAP1 mRNA expression. These findings highlight a novel mechanism of YAP1 regulation, which may explain how tumor cells maintain YAP1 mRNA expression at dynamic times during pancreatic tumorigenesis.

KEYWORDS: YAP1, HuR, pancreatic cancer, PDAC, posttranscriptional regulation

INTRODUCTION

Sustained proliferative signaling is a fundamental hallmark of cancer development (1). Consequently, tumor cells utilize RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) and microRNAs to posttranscriptionally dysregulate genes required for sustained proliferative signaling, survival, and development (2). Human antigen R (HuR; ELAVL1) is an RBP significantly upregulated in many cancers to facilitate the demands of both cell-autonomous and context-dependent gene expression (3). Using one of its RNA recognition motifs (RRMs), nuclear HuR recognizes distinct AU- and U-rich elements (AREs) found most frequently in the 3′ untranslated region (3′ UTR) of mRNA targets. HuR facilitates export of these targets to the cytoplasm and provides protection from negative regulators (e.g., microRNAs and inhibitory RBPs), thereby promoting stabilization and increased translation of the transcript (3). Based on these underlying mechanisms, cytoplasmic expression of HuR has been correlated with worse overall survival and various other pathological features in many cancers (4).

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) is one of the most lethal cancers, with an estimated 5-year overall survival rate of 10% (5). Gain-of-function mutations in the oncogene KRAS are nearly ubiquitous in PDAC (90 to 95%) and drive early neoplastic lesions (6). We previously demonstrated that pancreas-driven overexpression of HuR can cooperate with mutant KRASG12D to produce a robust fibro-inflammatory phenotype that drives a significant increase in pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasms (PanIN) and a 3.4-fold increase in PDAC incidence over mutant KRASG12D alone (7). Analysis of human patient samples demonstrated that HuR protein expression increases during the progression of PDAC cells from low- to high-grade PanINs, with the highest expression observed in invasive carcinoma (7). In addition, our lab has extensively characterized how HuR dysregulates gene expression patterns in response to a variety of intrinsic and extrinsic stressors of the tumor microenvironment (e.g., nutrient deprivation, hypoxia, growth factor stimulation, and cytotoxic agents) (3, 8–10).

The transcriptional coactivator Yes-associated protein 1 (YAP1) is an established oncogenic factor known to cooperate with mutant KRAS in driving PDAC onset, development, and maintenance (11, 12). Notably, pancreas-specific deletion of YAP1 halts the ability of mutant KRASG12D tumors to grow in vivo. YAP1 and its paralog, transcriptional coactivator with PDZ-binding motif (TAZ; WWTR1), are terminal members of the Hippo pathway, a conserved developmental pathway responsible for organ development, stemness, and cellular cross talk (13). This pathway in many malignancies regulates targets responsible for proliferation, cellular plasticity, epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition, and immune evasion (11, 14). Accordingly, in PDAC, elevated expression of YAP1 mRNA and of many of its target genes is strongly correlated with worse overall survival (hazard ratio [HR], 1.8; P = 0.005); however, the mechanism driving YAP1 overexpression is unclear (15). Unlike cervical and esophageal cancers, there are no reported gain-of-function mutations in PDAC and few cases of gene amplification (<1%) at the YAP1 locus (14, 16). Moreover, analysis of the Catalogue Of Somatic Mutations In Cancer (COSMIC) database (cancer.sanger.ac.uk) found that only 1 of 709 PDAC patient samples had copy number gains (0.14%) (17).

Here, we demonstrate for the first time in PDAC cells that HuR binds to and regulates YAP1 mRNA. This interaction provides an explanation for how YAP1 overexpression is sustained in PDAC cells. Importantly, we put forth a HuR activity signature (HAS) that closely correlates with YAP1 mRNA expression levels, which could potentially serve as an important clinical RNA-based biomarker.

RESULTS

Silencing of HuR (ELAVL1) in PDAC cells strongly impacts essential pro-oncogenic pathways, including a classic YAP1-conserved gene signature.

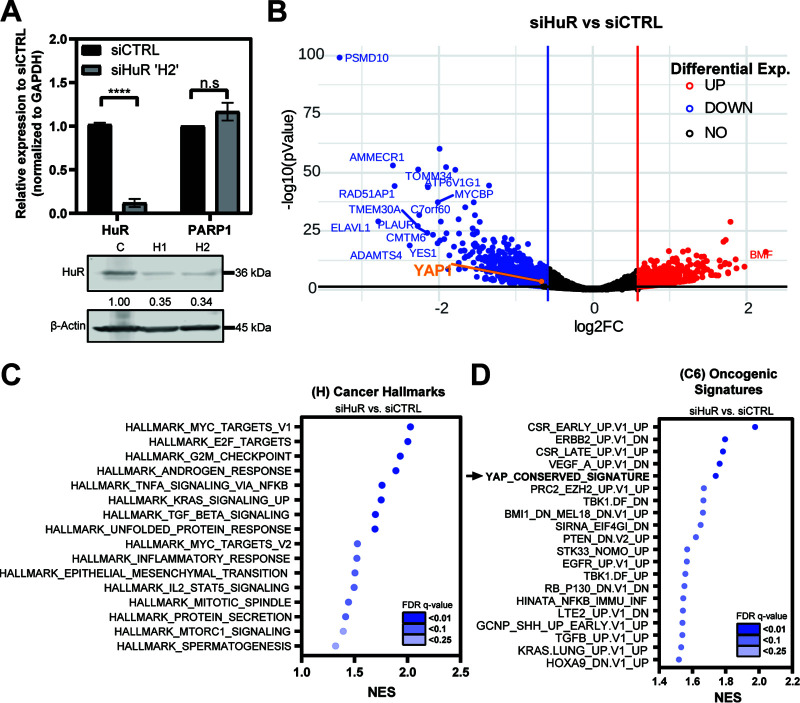

We previously demonstrated the role of HuR in regulating posttranscriptional expression of many prosurvival targets (2, 8, 9). To explore this on a transcriptome-wide scale, we performed paired-end RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) on MIA-PaCa2 cells transfected with small interfering RNAs against ELAVL1 (siHuR) or scrambled control (siCTRL), with PARP1 as a negative control (8) (Fig. 1A). Differential gene analysis of siHuR samples demonstrated that 1,554 genes were significantly downregulated and 872 were upregulated (Fig. 1B) (fold change, ±1.5; adjusted P < 0.05). Additionally, we selected a small panel of down- and upregulated genes and validated their differential expression by independent quantitative PCR (qPCR) (data not shown), confirming in all cases the validity of our RNA-Seq approach. We then performed gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) using cohorts from MSigDB (18, 19). Several “cancer hallmarks (H)” gene sets were significantly de-enriched by HuR (ELAVL1) silencing (e.g., MYC targets, E2F targets, KRAS signaling, androgen response, transforming growth factor β [TGF-β] signaling) (20, 21) (Fig. 1C; also, see Table S4 in the supplemental material). Of note, the “YAP1 conserved” signature (22) was one of the most depleted “oncogenic signatures (C6)” gene sets in the siHuR samples compared to siCTRL (Fig. 1D; Table S5). YAP1 has been proposed as an essential mediator of pancreatic tumorigenesis, due to its role as a transcriptional coactivator; however, the mechanisms that maintain its upregulation have been relatively unexplored in PDAC. Therefore, we sought to investigate whether YAP1 mRNA could be a direct target of HuR in PDAC cells.

FIG 1.

YAP1 conserved signature is strongly de-enriched in HuR knockdown samples. (A) (Top) MIA-PaCa2 cells were transfected with siRNA against HuR (siHuR ‘H2’; n = 4) and scrambled control (siCTRL; n = 4). mRNA expression of indicated targets was normalized to that of GAPDH, and PARP1 was used as a negative control. Student’s t test was performed. n.s, not significant; ****, P < 0.001. (Bottom) Knockdown validation of HuR with two siRNAs against HuR (H1 and H2, respectively) and expression relative to siCTRL, normalized to β-actin endogenous control. H2 was used for RNA-Seq experiments. (B) Volcano plots of differentially expressed genes within siHuR (n = 4) samples compared to siCTRL (n = 4) in MIA-PaCa2 cells. Cutoff is indicated at a fold change of ±1.5. (C and D) Dot plots representing the MSigDB GSEA analysis of siHuR samples showing the most significantly de-enriched gene sets. Dots are shaded according to the FDR q value and are plotted relative to normalized enrichment score (NES). (C) Cancer hallmarks (H) and (D) oncogenic signatures (C6) cohorts.

YAP1 overexpression in PDAC is not due to mutation or copy number alteration.

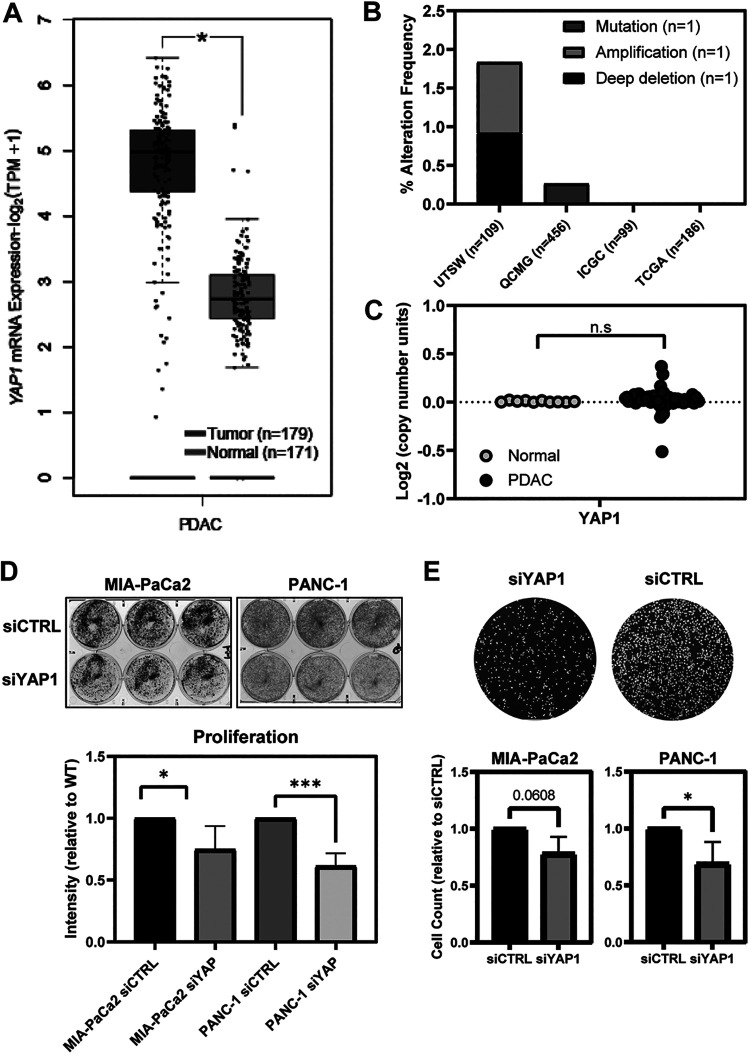

YAP1 is an essential mediator of tumor onset and development, and its overexpression has been linked to many clinicopathologic features of PDAC (11, 12). YAP1 mRNA is significantly overexpressed in PDAC samples analyzed from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) (Fig. 2A). We analyzed multiple PDAC data sets in the Cancer Biology Portal (cBioPortal) and found genetic alterations in the YAP1 locus occurred in less than 0.5% of all cases surveyed (Fig. 2B) (23). Moreover, there are almost no instances of YAP1 copy number alterations in tumor samples compared to normal tissue (Fig. 2C). Therefore, it is likely that overexpression of YAP1 in PDAC is due to epigenetic mechanisms.

FIG 2.

Overexpression of YAP1 is not due to copy number alteration or mutation in PDAC samples. (A) Box-and-whisker plot demonstrating significant overexpression of YAP1 mRNA in TCGA PDAC samples. Significant overexpression (*, P < 0.05) of tumor compared to normal using log2 FC of TPM (transcripts per million reads +1). (B) YAP1 alteration frequency (e.g., mutation, amplification, and/or deep deletion) from multiple pancreatic adenocarcinoma data sets in the cBioPortal (total n = 850; UTSW, ICGC, QCMG, and TCGA). (C) Copy number analysis of YAP1 in TCGA database comparing samples from PDAC patients to normal pancreas samples. n.s, not significant. (D) (Left) Representative crystal violet staining of proliferation assay; (right) quantification of intensity of the proliferation assay with siCTRL and siYAP1 in MIA-PaCa2 and PANC-1 cells (n = 4). (E) (Left) Representative image of DAPI staining of migration assay; (right) cell count of the migration assay with siCTRL and siYAP1 in PANC-1 and MIA-PaCa2 cells (n = 3).

YAP1 silencing yields a phenotype characterized by decreased survival and migration in PDAC cells.

Due to its programmable transcriptional regulation, YAP1 has been shown to be responsible for many cancer-associated phenotypes (11, 24, 25). One such phenotype is proliferation, which has been demonstrated to be impacted by growth factor cross talk (26). MIA-PaCa2 and PANC-1 cells were transfected with siRNA against YAP1 versus siCTRL and assessed for their growth. As expected, both cell lines demonstrated reduced growth upon YAP1 knockdown (Fig. 2D); interestingly, colony formation from single cells was not affected (data not shown), pointing at defects in proliferation rather than single-cell survival. In addition to proliferation, YAP1 has been shown to play an important role in regulating migration of tumor cells (27). YAP1 knockdown via siYAP1 demonstrated impaired migration compared to siCTRL (Fig. 2E), reaching statistical significance for PANC-1 and trending for MIA-PaCa2 (P = 0.06).

Overexpression of HuR is robustly correlated with YAP1 expression in patient samples.

To maintain the demands of increased transcription, many tumors exploit posttranscriptional RBPs and microRNAs to facilitate pre-mRNA and mature-mRNA processing and stability (28). One well-established RBP in PDAC is HuR (ELAVL1) (2, 29). Like YAP1 mRNA levels, ELAVL1 mRNA is significantly overexpressed in PDAC samples from TCGA (Fig. 3A). Moreover, there is a strong correlation between the expression of YAP1 and ELAVL1 mRNA within patient samples (Fig. 3B) (Pearson’s correlation R = 0.58; P < 0.001). We explored this connection also at the protein level by performing chromogenic immunohistochemistry (IHC) in human PDAC tumor samples. We previously demonstrated that increased HuR protein expression exponentially increases with the stage of disease (7). Cytoplasmic localization of HuR has been established as a marker for HuR RBP activity due to its role in regulating stability and translation of targets (30). In this study, we evaluated a 73-sample tissue microarray (TMA) of resected PDAC primary tumor samples and stained for both total HuR and YAP1 expression (Fig. 3C and D). High cytoplasmic HuR staining was detected in 71% (52/73) and high YAP1 expression was seen in 77% (56/73) of the patient samples. Notably, high expression for both proteins was seen in 58% (42/73) of samples (Fig. 3E).

FIG 3.

Patient tumor tissue microarray. (A) Box-and-whisker plot demonstrating significant overexpression of ELAVL-1 (HuR) mRNA in TCGA PDAC samples. Significant overexpression (*, P < 0.05) of tumor compared to normal samples using log2 FC of TPM (transcripts per million reads +1). GEPIA2 analysis is a one-way ANOVA. (B) Scatterplot demonstrating Pearson’s correlation of YAP1 mRNA expression compared to HuR (ELAVL1) mRNA in PDAC, in log2(TPM)+1. (C) The pancreatic cancer tumor tissue microarray (n = 73) was distributed over two slides. Scanned svs images are presented for PDA_1 (top) and PDA_2 (bottom) slides. IHC detection of YAP1 (left) and HuR (right) in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded PDAC tumors. (D) Representative images from 73 patient TMA slides. (E) Quantification and distribution of immunoreactivity scores for cytoplasmic HuR compared to total YAP1. The number of samples (n) staining for each group and percentage of samples in each quadrant are shown.

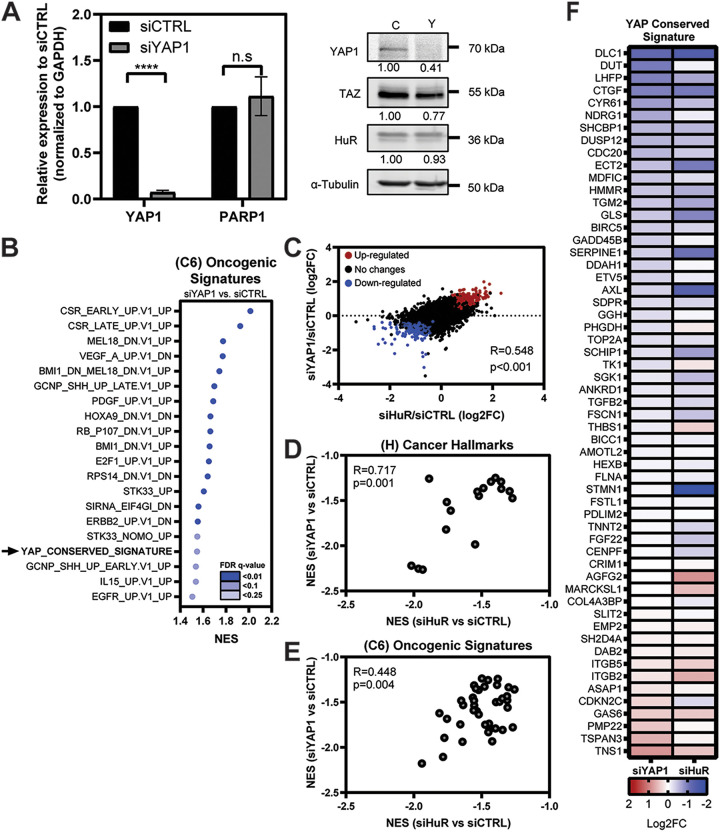

There is a significant correlation between differential expression in siHuR and siYAP1 RNA-Seq.

We then sought to assess how direct silencing of YAP1 would compare to the effects seen from siHuR using RNA-Seq as done for Fig. 1. MIA-PaCa-2 cells were transfected with siYAP1 and siCTRL (Fig. 4A) and evaluated for differential gene expression (fold change, ±1.5; adjusted P < 0.05). As expected, the “YAP1 conserved signature” was significantly de-enriched, along with many other oncogenic signaling pathways (Fig. 4B). We then compared the differential expression of all genes in both siYAP1 and siHuR samples after normalization to their control (Fig. 4C) (R = 0.548; P < 0.001). Similarly, we found a significant correlation between the impacted MSigDB hallmarks of cancer and oncogenic signature gene sets between knockdown conditions (Fig. 4D and E). Specifically interrogating the “YAP1 conserved signature,” the differential expression of many YAP1-activated targets was similarly affected in the siHuR samples, implying an overlap of function (Fig. 4F) (Pearson’s correlation, R = 0.564; P < 0.001). These data further supported our investigation into the connection between HuR and YAP1 in PDAC cells.

FIG 4.

Significant correlation between siHuR and siYAP1 differential gene expression in PDAC cells. (A) (Left) MIA-PaCa2 cells were transfected with siRNA against YAP1 (siYAP1, n = 3) and scrambled control (siCTRL, n = 3). mRNA expression of indicated targets was normalized to the GAPDH endogenous control. Student’s t test was performed. n.s, not significant; ****, P < 0.001. (Right) Knockdown validation of YAP1 and indicated proteins, showing expression relative to that of siCTRL, normalized to an α-tubulin endogenous control. (B) Dot plot representing the MSigDB oncogenic signatures (C6) GSEA analysis of siYAP1 samples, showing the most significantly de-enriched gene sets. Dots are shaded according to FDR q value and are plotted relative to NES. (C) Scatterplot demonstrating all differential gene expression between siHuR and siYAP1 samples after normalization to siCTRL. Pearson’s correlation and P values are listed on graph. Significantly downregulated (blue) and upregulated (red) genes are highlighted (adjusted P < 0.05). (D and E) Pearson’s correlation analysis of normalized enrichment scores (NES) from GSEA between siHuR and siYAP1 samples after comparison to siCTRL. Only significant gene sets (adjusted P value < 0.05) from the MSigDB (D) h.all.v7.2 hallmarks of cancer (H) and (E) oncogenic signatures (C6) are displayed. (F) Heat map demonstrating differential expression of genes within YAP conserved signature based upon log2 FC. siHuR compared to siYAP1 samples, after their normalization to siCTRL. Genes ranked in order by log2 FC based on the siHuR sample. Shading corresponds to the degree of log2 FC defined in the key.

YAP1 mRNA is a direct target of HuR.

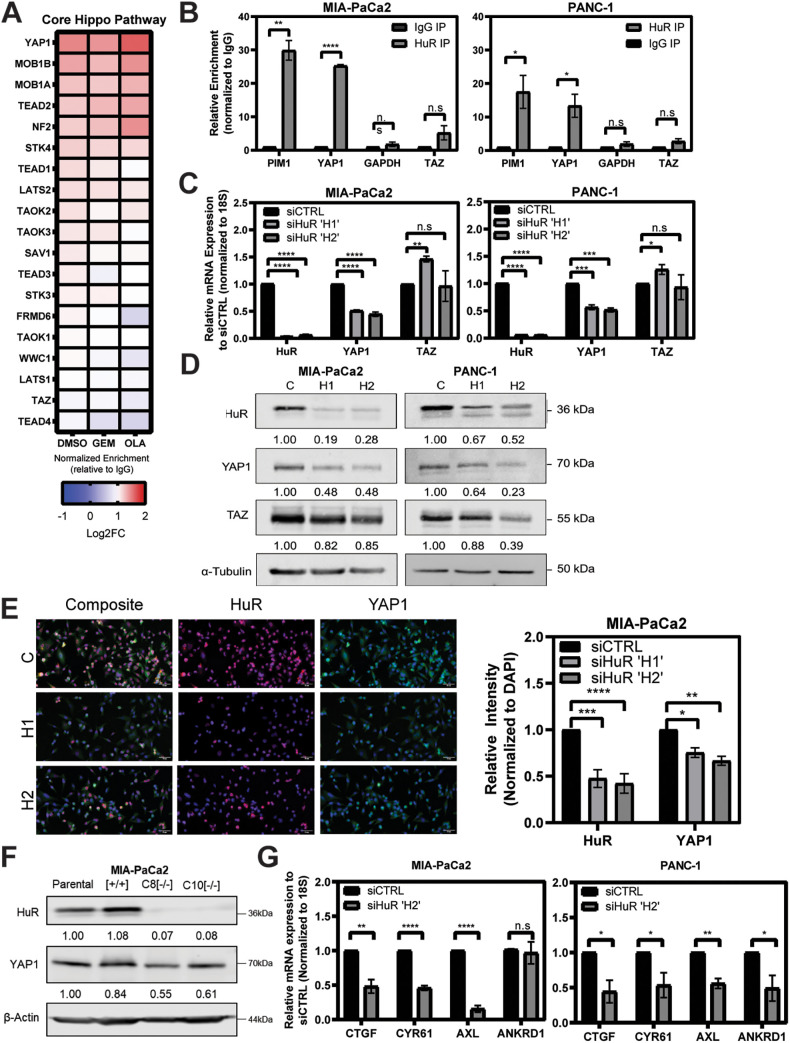

YAP1 and its paralog, TAZ, are terminal members of the developmental Hippo pathway, which is dysregulated in many cancers, with mutations, amplifications, or translocations often accounting for much of the aberrant activity (24). Thus far, we have shown a significant correlation between differential expression in siHuR and siYAP1 samples. This raises the important question of whether this correlation is due to HuR directly regulating YAP1 or rather other and even multiple Hippo pathway members. To address this, we evaluated ribonucleoprotein immunoprecipitation (RNP-IP) RNA samples run on a whole-transcriptome microarray (RNP-IP chip) (Fig. 5A) (31). MIA-PaCa2 cells were treated with established HuR-activating stressors, gemcitabine (GEM) and olaparib (OLA) (8, 31), as well as vehicle (dimethyl sulfoxide [DMSO]) representing a basal level of interaction between HuR and YAP1. RNA targets bound to HuR were assessed by determining fold change enrichment over the isotype control (IgG). From these samples, we assessed enrichment of the gene ontology (GO)-defined “core Hippo signaling” pathway. Of the transcripts in this pathway, YAP1 mRNA had the greatest enrichment associated with HuR in both basal (vehicle and DMSO treatment) and acutely stressed states. We note that this enrichment did not significantly increase in the stressed conditions over the vehicle state; therefore, subsequent characterization focused on this relationship during normal tumor cell homeostasis. Importantly, YAP1’s paralog WWTR1 (TAZ) mRNA is not bound by HuR, implying a direct HuR-YAP1 relationship. This aligns with previous work that identified YAP1 mRNA as directly regulated by HuR in osteosarcoma and peripheral neuronal sheath tumor cells (29, 32). We validated these findings by running independent RNP-IPs in two PDAC cell lines which demonstrate significant enrichment YAP1 mRNA upon HuR immunoprecipitation (Fig. 5B) (25.3- and 13.4-fold over IgG). Importantly, YAP1 pulldown is analogous to that of a previously established HuR target, proto-oncogene serine/threonine-protein kinase (PIM1), with glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) mRNA as a negative control (9). Again, we note that TAZ mRNA was not significantly isolated in either of two cell lines tested.

FIG 5.

YAP1 is a direct target of HuR and is strongly impacted by HuR silencing. (A) Heat map demonstrating the relative enrichment of mRNA targets bound by HuR compared to IgG for each listed condition (n = 2). Shading corresponds to fold change. DMSO was used as the vehicle. GEM, gemcitabine; OLA, olaparib. (B) Independent RNP-IP qPCR demonstrating relative fold enrichment of mRNA targets normalized to IgG. Relative enrichment of YAP1 and TAZ is demonstrated versus the positive control PIM1 and the negative control GAPDH. Data are combined from biological replicates for MIA-PaCa2 (n = 3) and PANC-1 (n = 4) cell lines. (C) qPCR analysis of indicated targets after 48 h knockdown with indicated siRNAs. Relative expression normalized to siCTRL. Each graph presents averages for technical replicates and combined biological replicates in triplicate, per indicated cell line. (D) Western blot analysis assessing total protein levels, after 48 h knockdown with indicated siRNAs (C, siCTRL; H1, siHuR H1; H2, siHuR H2). Relative protein expression is compared to siCTRL for each target and normalized to α-tubulin. Western blots are representative of three biological replicates performed in each indicated cell line, with molecular weights indicated to the right of each band. (E) Immunofluorescence of HuR (red) and YAP1 (green) in MIA-PaCa2 cells after 48 h knockdown with indicated siRNA (C, siCTRL; H1, siHuR H1; H2, siHuR H2). Nuclei were stained with DAPI. Magnification, ×40. The graph presents averages for technical replicates and combined biological replicates in triplicate. (F) Western blot analysis assessing total protein levels of indicated targets in two individual HuR homozygous knockout clones (C8 and C10) compared to parental and recombination control clone (+/+). Relative protein expression is compared to that of the parental clone and is normalized to β-actin. (G) Validation of YAP1 transcriptional target knockdown assessing siHuR H2 and siCTRL biological replicates from panel C in indicated cell lines. All qRT-PCR error is shown as SEM. Student’s t test was performed for panels B, C, E, and G. n.s, not significant; *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.005; ****, P < 0.001.

We then sought to determine the impact of modulating HuR expression on YAP1 mRNA and protein levels. When two independent siRNA oligonucleotides were used, knockdown of HuR resulted in significant downregulation of total YAP1 mRNA and protein in multiple PDAC cell lines via reverse transcription-qPCR (RT-qPCR) and Western blotting, respectively (Fig. 5C and D). We observed this effect in a time-dependent manner at all time points assessed (24, 48, and 72 h; data not shown). Additionally, we observed an inconsistent impact on TAZ mRNA and protein expression. This effect on TAZ at the protein level has been observed previously, and it could depend on the complex interaction and feedback from both HuR and YAP1 itself on TAZ; this would require further studies (20). Moreover, we were able to show significant decrease in YAP1 expression upon HuR knockdown via immunofluorescence, in both MIA-PaCa2 (Fig. 5E) and PANC-1 (data not shown) cells.

We also assessed constitutive loss of HuR, using knockout clones with homozygously deleted ELAVL1 (C8 and C10), previously generated with CRISPR-Cas9 editing (32). The clones demonstrate a reduction in YAP1 protein expression compared to the recombination control and the parental cell line (Fig. 5F). As YAP1 is a transcriptional coactivator, we assessed the effect of HuR knockdown on canonical Hippo target genes downstream of YAP1 (14). In both MIA-PaCa2 and PANC-1 cell lines, the knockdown of HuR significantly impacted the YAP1 transcriptional targets CTGF, CYR61, and AXL; whereas ANKRD1 was impacted only in PANC-1 cells (Fig. 5G) (33).

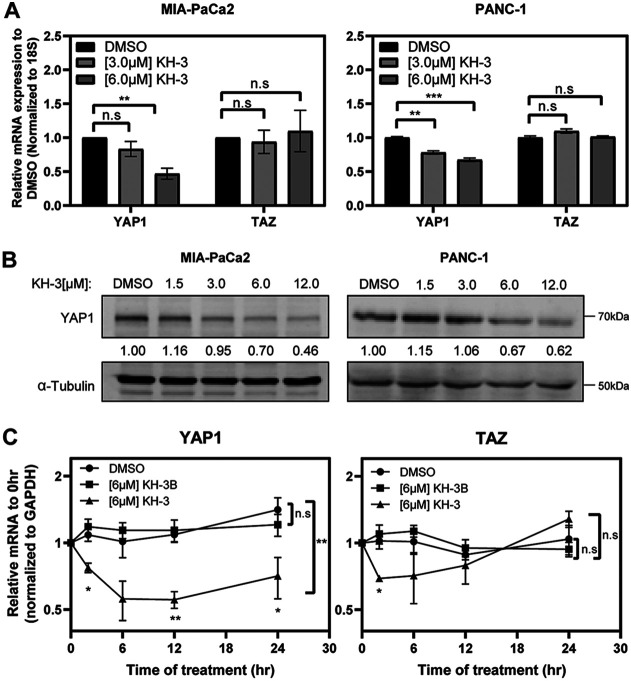

We further assessed the effect of HuR inhibition on YAP1 expression when treating cells with an established small-molecule inhibitor of HuR function, KH-3 (21, 34). This is a second-generation compound adapted from the previously developed HuR inhibitor CMLD-2 (21, 32, 34). Again, total YAP1 mRNA and protein expression was significantly impacted in a dose-dependent manner for multiple cell lines (Fig. 6A and B). Additionally, treatment with this compound over a time course demonstrates the significant impact HuR inhibition has on YAP1 mRNA over time compared to its vehicle and to KH-3B, a modified, functionally “dead” complement, with very similar chemical structure but no HuR binding activity (Fig. 6C) (34). KH-3 also affected the ability of HuR to bind to YAP1 mRNA in RNP-IP experiments (data not shown). Taken together, these data support a means of posttranscriptional regulation through HuR.

FIG 6.

YAP1 mRNA is functionally linked to HuR. (A) Relative mRNA expression of indicated targets, assessed after 24 h treatment with the HuR inhibitor KH-3 compared to the DMSO control. (B) Western blots assessing total protein levels after 24 h treatment with KH-3. Protein expression relative to DMSO, normalized to α-tubulin. Western blots are representative of three biological replicates performed for each indicated cell line, with molecular weights indicated to the right of each band. (C) MIA-PaCa2 cells were treated with fixed concentrations of KH-3 and KH-3B over a 24-h time course. Total mRNA expression is relative to that at 0 h. Student’s t test was performed for panel A. Multiple, unpaired t tests were performed at each time point for panel C, comparing KH-3 treatment to DMSO, and one-way ANOVA was performed for the overall data on three groups. n.s, not significant; *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.005.

HuR knockdown does not affect nascent YAP1 mRNA transcription.

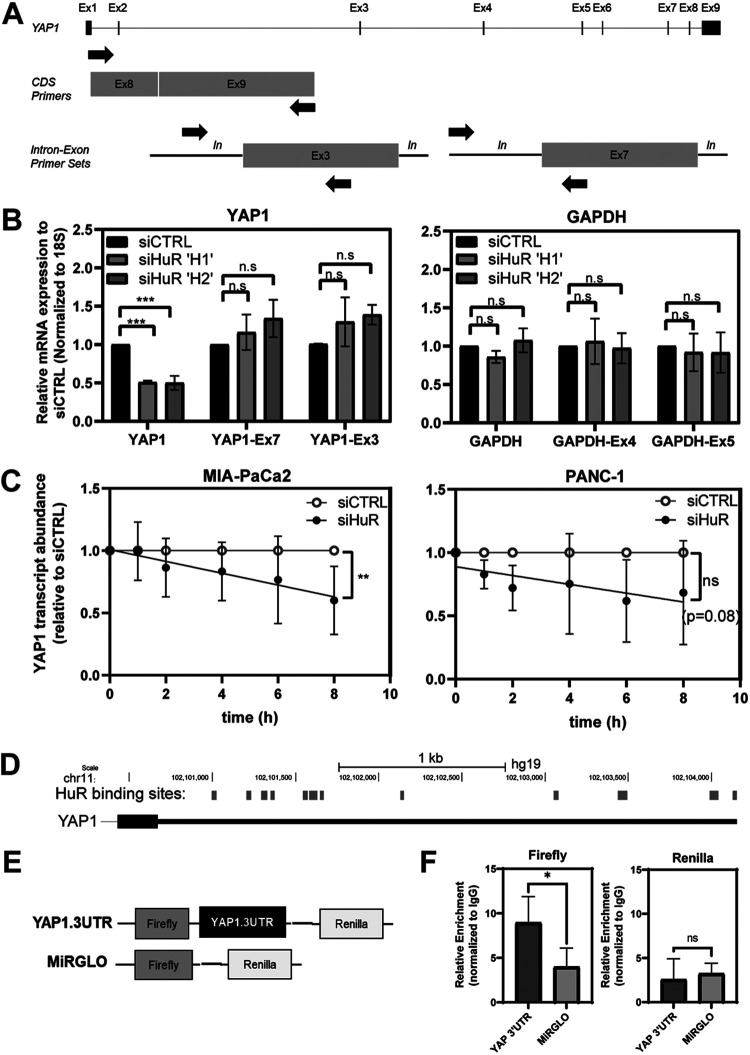

HuR has been proposed to function at virtually every stage of the RNA life cycle; however, its most prevalent function is to export mRNA cargo to the cytoplasm, where it facilitates transcript stability and increased translation (35). If HuR regulates YAP1 mRNA via its canonical mechanism, knocking down HuR should affect the levels of mature YAP1 mRNA and not YAP1 pre-mRNA. We can assess the levels of mature mRNA with exon-exon-spanning primer sets, while pre-mRNA levels can be evaluated using intron-exon-spanning primer sets (Fig. 7A). Once again, we observed that upon knocking down HuR via siRNA, the mature YAP1 mRNA is decreased, as detected by the exon-exon-spanning primers; however, when evaluating the levels of YAP1 pre-mRNA using two different intron-exon-spanning primer sets, we found that silencing of HuR had no impact on pre-mRNA levels (Fig. 7B). The same strategy was used for GAPDH as a negative control, and as expected, no differences were observed with any of the primer sets tested. Together, these data suggest that HuR regulates YAP1 expression at the mature-mRNA stage and not during pre-mRNA processing. Given the evidence accumulated so far in the regulation of YAP1 by HuR, we then asked whether HuR specifically affects the stability of YAP1 mRNA. Actinomycin D is a compound that blocks RNA polymerase activity by intercalating into DNA and halting new RNA synthesis. To assess if HuR affects stability of YAP1 mRNA, PDAC cells were transfected with either siHuR or siCTRL and then treated with actinomycin D to inhibit further transcription (36). We observed a decrease in YAP1 mRNA stability in both cell lines tested, with MIA PaCa-2 reaching statistical significance and PANC-1 approaching significance (P = 0.08) (Fig. 7C). These data suggest that one mechanism by which HuR regulates YAP1 is by affecting the stability of YAP1 mRNA.

FIG 7.

HuR does not regulate nascent YAP1 mRNA expression and affects its stability. (A) Schematic depicting the primer locations of coding sequence (CDS) primers used for mRNA expression to pre-mRNA levels depicted by expression of intron-exon-spanning primer sets. (B) Relative mRNA expression comparing CDS to intron-exon-spanning primers for YAP1 exon 7 and exon 3 (left) and GAPDH exon 4 and exon 5 (right). Student’s t test was performed. n.s, not significant; ***, P < 0.005. (C) Linear regression analysis of the YAP1 mRNA stability over time in cells treated with actinomycin D; the YAP1 mRNA in cells treated with siHuR was quantified relative to siCTRL (n = 4). Linear regression analysis was performed. n.s, not significant; **, P < 0.01. (D) Schematic of HuR binding sites predicted within the YAP1 3′ UTR from publicly available PAR-CLIP databases. Binding sites were mapped to the Genome Reference Consortium Human Build 37 (GRCh37 or hg19), which are scaled relative to their length and location on chromosome 11 (chr11). (E) Schematic of the MiRGLO dual-luciferase plasmid. (F) Quantification via qPCR of the relative enrichment of the firefly and Renilla genes in MIA-PaCa2 cells transfected with the YAP1.3′UTR reporter or MiRGlo control for 48 h; immunoprecipitation was performed with an anti-HuR antibody or an IgG control. Data depict relative enrichment with the anti-HuR antibody, normalized to IgG. Student’s t test was performed. ns, not significant; *, P < 0.05.

HuR regulates YAP1 mRNA expression via its 3′-untranslated region.

HuR recognizes its mRNA targets via its RRM domains, which have the strongest affinity for ARE sites. These sequences are frequently embedded in noncoding regions, predominantly in the 3′ UTR of mRNA (37). Often, the number of binding sites positively correlates with the degree of association and stabilization, with targets containing 8 or more AREs thought to be “high-confidence” targets (37, 38). We screened publicly available data sets of HuR immunoprecipitated samples and found a predicted 12 putative AREs in the YAP1 3′ UTR (Fig. 7D). To evaluate the direct impact on 3′ UTR regulation, we subcloned the full-length 3′ UTR sequence of YAP1 downstream of the firefly luciferase gene in the dual luciferase reporter construct MiRGLO. This bicistronic plasmid, referred to here as YAP1.3′UTR, transcribes the firefly gene as a reporter for the 3′ UTR activity, while the Renilla gene is independently regulated and serves to normalize readouts across conditions (Fig. 7E). We used this vector to assess the direct binding of HuR to the YAP1.3′UTR transcript. MIA-PaCa2 cells were transfected with YAP1.3′UTR versus the MiRGLO backbone and assessed for pulldown with an anti-HuR antibody compared to its IgG isotype control. Cytoplasmic lysates were isolated from each condition and split between beads containing anti-HuR or IgG control antibodies. To differentiate immunoprecipitation of the endogenous YAP1 from the plasmid vector, lysates were assessed with primers against the firefly and Renilla sequences (Fig. 7F). Notably, the firefly gene was significantly enriched in YAP1.3′UTR-transfected samples compared to the empty MiRGLO vector. Transcription of the Renilla gene does not depend on the subcloned 3′ UTR and did not show any differences between the 3′ UTR and empty plasmids. Together, these data demonstrate that HuR directly binds to elements in the 3′ UTR of YAP1.

HuR signature strongly predicts overall and disease-free survival.

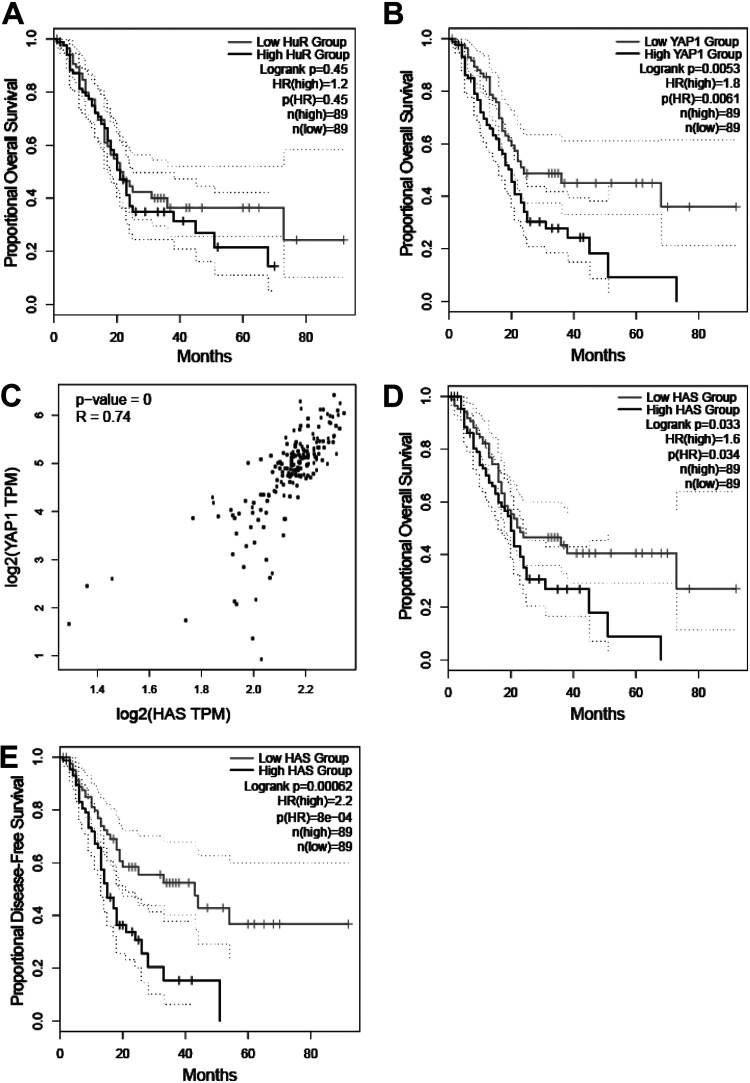

After establishing this novel connection in PDAC cells, we sought to explore its clinical relevance. To do so, we screened patient sample data from TCGA. Both HuR (ELAVL1) and YAP1 mRNAs are overexpressed in PDAC samples; however, only high YAP1 expression is considered prognostic for worse overall survival (Fig. 8A and B) (high-YAP1-group HR, 1.8; P = 0.0061; high-HuR-group HR, 1.2; P = 0.45) (15, 39). We and others demonstrated previously that the subcellular localization of HuR (i.e., cytoplasmic overexpression) is indicative of HuR activation; however, in PDAC cells, high cytoplasmic expression does not have prognostic value on its own (4, 40). Therefore, having a reliable, sensitive method to detect this activity in patient samples may provide clinical utility. To address this, we revisited our RNA-Seq results to develop our own oncogenic signaling signature based upon the top downregulated genes in siHuR samples compared to control (Table S8). Using a cutoff of log2(−1.495) or lower results in a set of 63 genes significantly silenced in siHuR samples versus siCTRL. We refer to this as the “HuR activity signature” (HAS). As expected, HAS very strongly correlated with YAP1 expression in TCGA PDAC samples (Fig. 8C) (R = 0.74; P < 0.001). Moreover, HAS robustly predicted worse overall and disease-free survival (Fig. 8D and E) (high-HAS-group HR, 1.6; P = 0.034; high-HAS-group HR, 2.2; P < 0.001). These findings suggest that transcriptional activity, as represented by HAS, may have more utility as a biomarker than the conventional readout of HuR localization (e.g., cytoplasmic HuR) (4, 40).

FIG 8.

HuR activity signature correlates with YAP1 expression and strongly predicts PDAC patient survival. (A and B) Kaplan-Meier plots demonstrating proportional overall survival in PDAC patient samples distinguished by low versus high HuR (ELAVL1) (A) and YAP1 (B) mRNA expression. (C) Pearson’s correlation analysis comparing individual YAP1 mRNA expression in log2(TPM)+1 to HAS signature. Proportional overall (D) and disease-free (E) survival predictions based upon low versus high HAS gene set expression. Log-rank (Mantel-Cox) P value and 95% confidence intervals (dotted lines) plotted on Kaplan-Meier plots. Hazard ratio of the “high” group with associated P value on the graph. All groups are distinguished based upon a median cutoff of 89 [n(high) and n(low)].

DISCUSSION

Therapeutic strategies targeting high-frequency mutations (e.g., mutant KRAS) in PDAC have proven largely unsuccessful (41). Therefore, a greater knowledge of relevant signaling pathways is required to find opportunities for novel therapeutic strategies. YAP1, as a transcriptional coactivator, has garnered much interest as an essential mediator of PDAC tumorigenesis. For instance, Gruber et al. found that YAP1 and its paralog TAZ are essential in mediating mutant KRAS-induced pancreatitis and acinar-to-ductal metaplasia, both malignant events which could develop into PanIN lesions (11). Zhang et al. found that homozygous deletion of Yap1fl/fl in mutant KrasG12D genetically engineered mouse models halted the occurrence of PDAC tumors, with and without Tp53 loss (12). Recently, Yan et al. put forth a mechanism that wild-type KRAS allele loss activates YAP1 promoting PDAC tumorigenesis (42) These studies underscore the essential role of YAP1 in PDAC biology; however, what regulates YAP1 expression remains unexplained.

Here, we provide one novel pathway that could account for YAP1 dysregulation in PDAC cells following its transcription and pre-mRNA processing. The RBP HuR (ELAVL1) is well known to upregulate factors essential for various features of tumorigenesis (8, 20, 21). This is further supported in Fig. 1, which shows that many hallmarks of tumor biology are significantly de-enriched in HuR-silenced samples. ELAVL1 and YAP1 mRNA are significantly correlated in PDAC samples, with the majority (58%) of high cytoplasmic-HuR-expressing PDACs also being positive for high YAP1 staining. We demonstrated that in PDAC cells, cytoplasmic HuR protein binds directly to the YAP1 transcript and that loss of HuR (e.g., siRNA knockdown, pharmacological inhibition, and CRISPR-mediated knockout) significantly reduces YAP1 mRNA and protein expression while also considerably affecting YAP1-regulated transcriptional targets. Moreover, we demonstrated that HuR’s control of YAP1 is due to regulation of the YAP1 3′ UTR, which is common for most established HuR targets. Together, we put forth a novel mechanism by which YAP1 is aberrantly regulated in PDAC cells.

Despite improvements to surgical techniques and adjuvant therapies, there remains a dire need for novel biomarkers to move toward patient-tailored approaches for the treatment of PDAC (20). Evidence for the essential function and overexpression of HuR in PDAC and other cancers has frequently been cited; however, neither mRNA expression (high-HuR-group HR, 1.2; P = 0.45) nor cytoplasmic immunoreactivity has been unequivocally proven to be a reliable predictive marker for survival outcomes (4, 40). Therefore, we utilized our RNA-Seq expression data to develop a signature of genes (HAS) which would reflect the HuR-dependent reactome of genes most affected by inhibition of the target. As further evidence that HuR regulates YAP1, HAS strongly correlated with YAP1 mRNA expression (R = 0.74; P < 0.001), which is well established to be prognostic for worse overall survival (high-YAP1-group HR, 1.8; P = 0.0061). Notably, a high HAS was able to predict worse overall (high-HAS-group HR, 1.6; P = 0.034) and disease-free (high-HAS-group HR, 2.2; P < 0.001) survival in PDAC samples.

We acknowledge that other mechanisms are likely at play in accounting for total YAP1 mRNA and protein expression levels in PDAC. Further, the posttranslational regulation of YAP1 (i.e., activated YAP1) has been demonstrated to be critical in PDAC tumorigenesis (11, 25). The remaining expression of YAP1 upon HuR knockdown or knockout may be accounted for by other compensatory posttranscriptional and posttranslational factors not investigated in this study (e.g., RBPs and microRNAs). Moreover, beyond the Hippo pathway, HuR may further influence YAP1 through indirect effects of complementary pathways, which were not investigated in this study. Ultimately, we believe that this work may prove to be foundational for exploiting context-dependent YAP1 expression and function in PDAC cells. Future studies will determine the context in which HuR regulates YAP1. For instance, YAP1 has recently drawn attention for its ability to compensate for oncogene addiction when mutant KRAS is suppressed (12, 25), and certain molecular subtypes of pancreatic cancer have been known to inexplicably switch away from oncogenic KRAS dependency (43–45). Future work will determine whether these states are “fixed” or “plastic” and whether the HuR-YAP1 axis could mediate the switch between these subtypes (46).

Finally, while our data provide a functional link between YAP1 and HuR and suggest translational significance, ongoing in vivo modeling will determine the significance of HuR’s regulation of YAP1 mRNA in PDAC tumorigenesis, in the context of the important tumor microenvironment. Future studies will decipher the translational significance of this interaction in relation to PDAC tumorigenesis and therapeutic resistance.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

All studies reported here were performed with the most stringent of ethics and rigor. Any patient-relevant studies are accounted for under Thomas Jefferson University IRB approval, which accounts for any consenting of patients and the ethics of using these samples. Samples were deidentified before the material was obtained by the authors and before any analyses were performed. Any patient-relevant studies performed at OHSU have been reviewed by the Integrity Department, which has determined an exemption from IRB requirements for the reasons explained above.

Cell lines and tissue culture.

Human pancreatic cancer cell lines (MIA-PaCa2 and PANC-1) were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA), confirmed negative for mycoplasma contamination, and validated using short-tandem-repeat profiling. All cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 1% l-glutamine, and antibiotics (1% penicillin-streptomycin) at 37°C and 5% CO2. MIA-PaCa2 HuR knockout clones (C8 and C10) were generated via CRISPR-Cas9 technology (Synthego, Redwood City, CA) and characterized as previously described with clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (32).

siRNA transfection.

All siRNAs were ordered from Dharmacon (Lafayette, Colorado). ON-TARGETplus control siRNA 1 (D-00110-01-05) was used as a nontargeted control (siCTRL). ON-Target plus siRNA (J-012200-07) was used against YAP1. Custom siRNAs against HuR (ELAVL1) included siHuR H1 (CCA-UUA-AGG-UGU-CGU-AUG-CUC-UU) and siHuR H2 (AAA-CCA-UUA-AGG-UGU-CGU-AUG-UU). siRNA (30 nM) was transfected with RNAiMax (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) in Opti-MEM for 48 h before assessment of knockdown, unless otherwise indicated.

Proliferation and migration assays.

For proliferation, MIA-PaCa2 and PANC-1 cell lines were transfected with siYAP1 and siCTRL, with cells seeded at 30,000 cells/well in 6-well plates. Following transfection, cells were not further manipulated until fixation and crystal violet staining 5 to 7 days later, followed by imaging and quantification using Image J software. For migration assays, cells were transfected with siYAP1 and siCTRL in 60-mm plates. After 24 h, cells were then starved in serum-free medium for an additional 24 h and then moved to migration chambers (24-well format, 8.0-μm pores; Corning) at a density of 50,000 cells per chamber, to be allowed to migrate following a 0-to-20% serum gradient. Twenty-four hours later, the membranes containing migrated cells were collected, and cells were fixed and stained with DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) for imaging and quantification.

RT-qPCR and RNA analysis.

Total RNA was isolated using an RNeasy minikit (Qiagen, Germantown, MD). Purified RNA was analyzed for quality and concentration using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and reverse-transcribed into cDNA using a high-capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit (Applied Biosystems, Waltham, MA). qPCRs were performed using SYBR green master mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and results were analyzed using the 2−ΔΔCT method as described previously (10). Data were normalized to the reference genes, 18S or GAPDH mRNA, as indicated. The NCBI Primer-BLAST tool was used to generate primer pairs for qPCR. Primers for the mRNA coding and pre-mRNA sequences were targeted against exon-exon- and intron-exon-spanning junctions, respectively. Specific forward and reverse primer sets are outlined in Table S1 in the supplemental material.

mRNA stability assay.

MIA-PaCa2 and PANC-1 cell lines were plated to 80% confluence in 60-mm plates and transfected with siHuR (H2) or siCTRL as reported above. After 24 h, each condition was treated with actinomycin D (5 μM) to inhibit further transcription. Cells were then harvested at 0, 1, 2, 4, 6, and 8 h after actinomycin D treatment. Analysis of the treatment was performed according to reference 36, which allowed us to compare different groups, with a minor modification in the final plotting in order to normalize the siHuR treatment to siCTRL, which was set as the baseline at 1. This experiment was performed in biological quadruplicate.

KH-3 compound.

The HuR inhibitor KH-3 (and the corresponding KH-3B control compound, with a related chemical structure but no HuR binding activity) was a generous gift from Liang Xu’s lab at the University of Kansas (21, 34). For mRNA time course assays, cells were treated with a fixed dose of KH-3, its functionally dead complement KH-3B, or DMSO control.

RNP-IP for endogenous and plasmid-transfected samples.

Protein extracts were isolated using the NE-PER nuclear and cytoplasmic extraction kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). Input samples for total cytoplasmic RNA and protein, as well as the nuclear fraction, were taken. Immunoprecipitation of ribonucleoprotein complexes (RNP-IP) was carried out as previously described with 30 μg of either normal rabbit immunoglobulin (IgG1; Cell Signaling) or anti- HuR polyclonal antibody (MBL International, Woburn, MA) (10). In this study, both input and immunoprecipitated RNA were reverse transcribed and the cDNA was assessed for fold change enrichment of target species, using the 2−ΔΔCT method as described previously (47). For each sample, the difference in cycle threshold values (ΔCT) was first determined between each IP sample and its respective input condition (CTIP − CTinput). Then, ΔΔCT was obtained by comparing HuR IP and its respective IgG IP control (ΔCTHuR IP − ΔCTIgG IP). RNP-IP for both endogenous and plasmid-transfected samples was performed using this analysis.

For RNP-IPs with plasmid-transfected samples, the full-length YAP1 mRNA 3′ UTR amplified from MIA-PaCa2 genomic DNA (gDNA) was subcloned into Promega’s pMiRGLO vector using XhoI and SbfI restriction enzymes (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA). The product was ligated and transformed into GC5 competent cells, and the final plasmid extracted using plasmid maxiprep kits (Qiagen, Germantown, MD). For transfection of PDAC cell lines, for each condition, two 150-mm dishes seeded at 5 × 106 cells per plate were transfected with 62.5 ng of plasmid for 48 h. Primers against the firefly and Renilla coding sequences were used to assess immunoprecipitation of the exogenous plasmid via qPCR.

The whole-transcriptome microarray on RNP-IP samples was performed (31). Briefly, cells were treated with either olaparib (10 μM) or gemcitabine (1 μM) as well as vehicle (DMSO) for 16 h, and cytoplasmic HuR was immunoprecipitated as described above. RNA from HuR RNP-IP was used to generate cRNAs and subsequently cDNAs. An Affymetrix GeneChips human Clariom D array was hybridized with fragmented and biotin-labeled target (5 μg) in 220 μL of hybridization cocktail. Target denaturation was performed at 99°C for 5 min and then 45°C for 5 min, followed by hybridization for 16 to 18 h. Raw probe intensities from the Affymetrix CEL files were preprocessed and normalized using Expression Console software 1.4 into CHP formatted files and extracted using the affxparser library in R. Probe signals were further processed by determining the average HuR intensity relative to the IgG signal to identify transcripts that are enriched for HuR binding. Differential HuR interactions were determined by fitting a linear model to the normalized HuR intensities to identify differentially bound transcripts using Limma (48).

Western blot analysis.

Cells were lysed in ice-cold RIPA buffer (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc., Dallas, TX) supplemented with fresh protease inhibitors (protease inhibitor cocktail, phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride [PMSF], and sodium orthovanadate). Protein samples were prepared in 5× Laemmli buffer and resolved by SDS-PAGE followed by transfer to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). After blocking with Odyssey (TBS [Tris-buffered saline]) blocking buffer (LI-COR), membranes were probed with primary antibodies and incubated overnight at 4°C. The membranes were incubated with near-infrared-tagged secondary antibodies (LI-COR) and then washed. Bound antibodies were visualized using an Odyssey infrared imaging system (LI-COR) and analyzed with Image Studio Lite (v 5.2) as previously described (49). Relative quantitation of band intensity was first normalized to each sample’s matched loading control (β-actin or α-tubulin where indicated) and then compared to that of the control sample. Specific primary and secondary antibodies used for detection are outlined in Table S2.

IHC, immunoreactivity scoring, and statistical analysis.

A tumor tissue microarray of PDAC samples was constructed using formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded samples from patients at the Jefferson University Hospital (Philadelphia, PA, USA) from whom consent had been obtained by the institutional review board (9). Antigen retrieval was performed on the Roche Ventana Discovery Ultra staining platform using Discovery CCI (Roche catalog no. 950-500) for a total application time of 64 min. Primary antibodies are reported in Table S2 and were diluted in antibody dilution buffer (Roche catalog no. ADB250) and applied to the slides at 36°C for 44 min. Secondary immunostaining used a horseradish peroxidase (HRP) multimer cocktail (Roche catalog no. 760-500), and immune complexes were visualized using the ultraView universal DAB (diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride) detection kit (Roche catalog no. 760-500). Slides were then washed with a Tris-based reaction buffer (Roche catalog no. 950-300) and counterstained with hematoxylin II (Roche catalog no. 790-2208) for 8 min.

For the 73 subjects with complete IHC staining and outcome data, Pearson’s correlation analysis was completed by chi-square test. Student’s t test was used to compare the results of each measured variable with control results. P values of <0.05 were considered significant. All analyses were done using GraphPad Prism (v 9). Stained tissues were scored in a blind fashion and reviewed by a pathologist (W.J.) for percent positivity of staining as described previously (9). For both YAP1 and cytoplasmic HuR, staining positivity was scored on a scale of 0% to 100% and averaged across triplicate samples. Five subjects were removed for the comparison of HuR and YAP1 for samples that did not have interpretable staining for both. Clinicopathologic data from patients composing the tissue microarray were obtained from the Thomas Jefferson University institutional cancer registry and compiled in SPSS (v 26) (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY) (see also Table S3).

Immunofluorescence.

Cells were grown on 2-well chamber slides (Thermo Fisher Scientific no. 154461). siRNA transfection was carried out as described above. After 48 h, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and permeabilized with 0.3% Triton X-100. Cells were then immunostained and mounted. Antibodies are reported in Table S2. Nuclei were stained with DAPI ProLong Gold (Life Technologies). Slides were imaged with a Leica DM6000 B upright microscope, and Image J was used for quantification of staining intensity.

RNA-Seq.

Paired-end, 150-cycle eukaryotic RNA-Seq was performed by Novogene Co., Ltd. (Sacramento, CA), using the Hi-Seq Illumina platform. Briefly, cells were transfected with siRNA oligonucleotides against HuR (siHuR) and scramble control (siCTRL) in biological quadruplicate and YAP1 (siYAP1) in biological triplicate. Total RNA was isolated using an RNeasy minikit (Qiagen). Purified RNA was analyzed for quality and concentration using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Reference genome and gene model annotation files were downloaded from genome website browsers (NCBI/UCSC/Ensembl) directly. Paired-end fastq sequences were trimmed using trim-galore (v 0.6.3) and default parameters. Pseudoalignment was performed with kallisto (v 0.44.0) using genome assembly GRCh38.p5 and gencode (v 24) annotation; default parameters were used other than the number of threads. The Bioconda package bioconductor-tximport (v 1.12.1) was used to create gene level counts and abundances (TPMs). Quality checks were assessed with FastQC (v 0.11.8) and MultiQC (v 1.7). Quality checks, read trimming, pseudoalignment, and quantitation were performed via a reproducible snakemake pipeline, and all dependencies for these steps were deployed within the anaconda package management system (50, 51). Fractional count estimates were rounded to the nearest whole number for use with DESeq2 (v 1.24.0) for differential expression analysis between two conditions/groups (four or three biological replicates per condition, as indicated). The false discovery rate (FDR) was controlled using the Benjamini-Hochberg method. An FDR (q value) threshold of 0.05 and a fold change (FC) threshold of ±1.5 were used to select significant genes. Volcano plots were generated with Rstudio. Scatterplots and heat maps were plotted using log2 FC from DESeq2 analysis (52, 53).

GSEA.

Preranked lists were generated from RNA-Seq expression data based on DESeq2 P value and fold change. The ranking was from most significant down to most significant up based on sign(FC) × [−log10(P value)]. GSEA preranked analysis, with 1,000 permutations and all basic and advanced fields set to default values (v 4.0; Broad Institute, USA), was used to analyze gene set enrichment. Gene sets used were obtained from the Molecular Signatures Database (MSigDB, v 6.0; https://www.gsea-msigdb.org/gsea/index.jsp). Cancer hallmarks (H) and oncogenic signatures (C6) were evaluated. Gene set enrichment lists for each sample within each cohort are included as Tables S4 to S7. The GSEA lists in the figures are plotted as dot plots, ranked upon their normalized enrichment score (NES), and shaded based upon their FDR q value.

GEPIA.

Box-and-whisker plots, scatterplots, and Kaplan-Meier plots for overall and disease-free survival using TCGA pancreatic cancer sample data (PAAD; referred to here as PDAC) were generated using the publicly available GEPIA v 2 platform (http://gepia2.cancer-pku.cn/#index) (39). For box plots, the method for differential analysis used by GEPIA2 is one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), using disease state as variable for calculating differential expression. All Kaplan-Meier groups were based upon median cutoff and assessed using log-rank (Mantel-Cox) hypothesis testing with 95% confidence intervals plotted on graphs. Pearson correlation analysis of TCGA patient samples was assessed by comparing log2(TPM)+1 of indicated transcripts.

HAS.

The HuR activity signature (HAS) was developed from DSEQ2 TPM files, assessing the most significantly silenced genes upon HuR knockdown (siHuR versus siCTRL) at a cutoff of log2(−1.495) or lower. This resulted in a list of 63 significantly impacted genes to represent the signature, which can be found in Table S8. This signature was assessed for Kaplan-Meier analysis of overall and disease-free survival, as well as correlation analysis to YAP1 expression using the GEPIA2 program. “High” and “low” groups were differentiated using a median cutoff of 50% for each group.

Oncomine.

The Oncomine web platform is an integrated database combining publicly available data from various cancer microarrays and was used to generate copy number analysis plots. TCGA data were filtered to compare normal samples to pancreatic cancer classifications in Microsoft Excel. Results were plotted using GraphPad Prism (v 9).

Cancer Biology Portal.

The Cancer Biology Portal (cBioPortal) is an open-access platform for cancer genomic data sets found at https://www.cbioportal.org/. Allele alteration frequency (e.g., mutations, insertions, and deletions) of YAP1 in pancreatic adenocarcinoma samples was queried from samples in the ICGC (54), QCMG (45), TCGA (original data: https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/projects), and UTSW (55) data sets using basic inputs (56, 57).

Statistics.

Data are shown in bar graphs and scatterplots as means and standard errors of the means (SEM). A P value of less than 0.05 was deemed statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed by two-tailed unpaired Student’s t tests unless otherwise specified in the figure legends. Quantifications were performed from a minimum of three experimental groups unless otherwise specified.

Data availability.

The data set supporting the conclusions of this article are available in the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO), under the accession numbers GSE167525 for RNA-Seq data (raw fastq files, optimized count data, and TPM files) and GSE166951 for RNP-IP chip microarray files. All other data sets are publicly available from corresponding web addresses.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Liang Xu and members of his laboratory for their support. We thank Raymond O’Neil for technical help as well as the support from the Advanced Light Microscopy Shared Resource at OHSU. We are grateful to Alicia Johnson, Senior Biostatistician in the Department of Surgery at OHSU, for the extensive revision of the statistical analyses performed for this study.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (R01CA212600 to J.R.B., RO1CA196228 to R.C.S., and U01CA224012 to J.R.B. and R.C.S.) and AACR grant 15-90-25-BROD to J.R.B. Both J.R.B. and R.C.S. are supported by the Brenden-Colson Center for Pancreatic Care at Oregon Health & Science University. Additional funding was supported by grants from the Newell Devalpine Foundation, the Mary M. Halinski Pancreatic Cancer Research Fund, the Hirshberg Foundation, and the Sarah Parvin Foundation.

S.Z.B. and J.R.B. designed the experiments. S.Z.B. conducted the majority of the experiments and wrote the manuscript. S.Z.B. and J.R.C. conducted RNP-IPs and data analysis in Fig. 5 to 7. H.D.H. developed the snakemake pipeline for raw data processing, alignment, and counts. C.P., A.N., and S.Z.B. performed subsequent bioinformatics analysis. A.J. carried out the experiments reported in Fig. 5A, with M.D.M. conducting analysis. G.A.M. carried out the experiments reported in Fig. 5E. C.J.Y., C.W.S., and W.J. conducted collection and analysis for Fig. 3C to E. T.L.S. conducted statistical analysis for Table S3. J.A.C. subcloned and validated plasmids. R.D.N. oversaw preparation of the manuscript and its revision. J.R.B., D.A.D., and R.C.S. provided support and design. All authors aided in manuscript preparation and editing.

We declare that we have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available online only.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. 2011. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell 144:646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brody JR, Dixon DA. 2018. Complex HuR function in pancreatic cancer cells. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA 9:e1469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Srikantan S, Gorospe M. 2012. HuR function in disease. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed) 17:189–205. doi: 10.2741/3921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tatarian T, Jiang W, Leiby BE, Grigoli A, Jimbo M, Dabbish N, Neoptolemos JP, Greenhalf W, Costello E, Ghaneh P, Halloran C, Palmer D, Buchler M, Yeo CJ, Winter JM, Brody JR. 2018. Cytoplasmic HuR status predicts disease-free survival in resected pancreatic cancer: a post-hoc analysis from the international phase III ESPAC-3 clinical trial. Ann Surg 267:364–369. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. 2020. Cancer statistics, 2020. CA A Cancer J Clin 70:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grant TJ, Hua K, Singh A. 2016. Molecular pathogenesis of pancreatic cancer. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci 144:241–275. doi: 10.1016/bs.pmbts.2016.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peng W, Furuuchi N, Aslanukova L, Huang Y-H, Brown SZ, Jiang W, Addya S, Vishwakarma V, Peters E, Brody JR, Dixon DA, Sawicki JA. 2018. Elevated HuR in pancreas promotes a pancreatitis-like inflammatory microenvironment that facilitates tumor development. Mol Cell Biol 38. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00427-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chand SN, Zarei M, Schiewer MJ, Kamath AR, Romeo C, Lal S, Cozzitorto JA, Nevler A, Scolaro L, Londin E, Jiang W, Meisner-Kober N, Pishvaian MJ, Knudsen KE, Yeo CJ, Pascal JM, Winter JM, Brody JR. 2017. Posttranscriptional regulation of PARG mRNA by HuR facilitates DNA repair and resistance to PARP inhibitors. Cancer Res 77:5011–5025. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-2704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blanco FF, Jimbo M, Wulfkuhle J, Gallagher I, Deng J, Enyenihi L, Meisner-Kober N, Londin E, Rigoutsos I, Sawicki JA, Risbud MV, Witkiewicz AK, McCue PA, Jiang W, Rui H, Yeo CJ, Petricoin E, Winter JM, Brody JR. 2016. The mRNA-binding protein HuR promotes hypoxia-induced chemoresistance through posttranscriptional regulation of the proto-oncogene PIM1 in pancreatic cancer cells. Oncogene 35:2529–2541. doi: 10.1038/onc.2015.325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lal S, Burkhart RA, Beeharry N, Bhattacharjee V, Londin ER, Cozzitorto JA, Romeo C, Jimbo M, Norris ZA, Yeo CJ, Sawicki JA, Winter JM, Rigoutsos I, Yen TJ, Brody JR. 2014. HuR posttranscriptionally regulates WEE1: implications for the DNA damage response in pancreatic cancer cells. Cancer Res 74:1128–1140. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-1915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gruber R, Panayiotou R, Nye E, Spencer-Dene B, Stamp G, Behrens A. 2016. YAP1 and TAZ control pancreatic cancer initiation in mice by direct up-regulation of JAK-STAT3 signaling. Gastroenterology 151:526–539. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang W, Nandakumar N, Shi Y, Manzano M, Smith A, Graham G, Gupta S, Vietsch EE, Laughlin SZ, Wadhwa M, Chetram M, Joshi M, Wang F, Kallakury B, Toretsky J, Wellstein A, Yi C. 2014. Downstream of mutant KRAS, the transcription regulator YAP is essential for neoplastic progression to pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Sci Signal 7:ra42. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2005049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang J, Wu S, Barrera J, Matthews K, Pan D. 2005. The Hippo signaling pathway coordinately regulates cell proliferation and apoptosis by inactivating Yorkie, the Drosophila homolog of YAP. Cell 122:421–434. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rozengurt E, Sinnett-Smith J, Eibl G. 2018. Yes-associated protein (YAP) in pancreatic cancer: at the epicenter of a targetable signaling network associated with patient survival. Signal Transduct Target Ther 3:11. doi: 10.1038/s41392-017-0005-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhou Q, Bauden M, Andersson R, Hu D, Marko-Varga G, Xu J, Sasor A, Dai H, Pawłowski K, Said Hilmersson K, Chen X, Ansari D. 2020. YAP1 is an independent prognostic marker in pancreatic cancer and associated with extracellular matrix remodeling. J Transl Med 18:77. doi: 10.1186/s12967-020-02254-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dai H, Shao YW, Tong X, Wu X, Pang J, Feng A, Yang Z. 2020. YAP1 amplification as a prognostic factor of definitive chemoradiotherapy in nonsurgical esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Med 9:1628–1637. doi: 10.1002/cam4.2761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tate JG, Bamford S, Jubb HC, Sondka Z, Beare DM, Bindal N, Boutselakis H, Cole CG, Creatore C, Dawson E, Fish P, Harsha B, Hathaway C, Jupe SC, Kok CY, Noble K, Ponting L, Ramshaw CC, Rye CE, Speedy HE, Stefancsik R, Thompson SL, Wang S, Ward S, Campbell PJ, Forbes SA. 2019. COSMIC: the Catalogue Of Somatic Mutations In Cancer. Nucleic Acids Res 47:D941–D947. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky1015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Subramanian A, Tamayo P, Mootha VK, Mukherjee S, Ebert BL, Gillette MA, Paulovich A, Pomeroy SL, Golub TR, Lander ES, Mesirov JP. 2005. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102:15545–15550. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506580102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liberzon A, Birger C, Thorvaldsdóttir H, Ghandi M, Mesirov JP, Tamayo P. 2015. The Molecular Signatures Database (MSigDB) hallmark gene set collection. Cell Syst 1:417–425. doi: 10.1016/j.cels.2015.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Palomo-Irigoyen M, Pérez-Andrés E, Iruarrizaga-Lejarreta M, Barreira-Manrique A, Tamayo-Caro M, Vila-Vecilla L, Moreno-Cugnon L, Beitia N, Medrano D, Fernández-Ramos D, Lozano JJ, Okawa S, Lavín JL, Martín-Martín N, Sutherland JD, de Juan VG, Gonzalez-Lopez M, Macías-Cámara N, Mosén-Ansorena D, Laraba L, Hanemann CO, Ercolano E, Parkinson DB, Schultz CW, Araúzo-Bravo MJ, Ascensión AM, Gerovska D, Iribar H, Izeta A, Pytel P, Krastel P, Provenzani A, Seneci P, Carrasco RD, Del Sol A, Martinez-Chantar ML, Barrio R, Serra E, Lazaro C, Flanagan AM, Gorospe M, Ratner N, Aransay AM, Carracedo A, Varela-Rey M, Woodhoo A. 2020. HuR/ELAVL1 drives malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor growth and metastasis. J Clin Invest 130:3848–3864. doi: 10.1172/JCI130379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dong R, Chen P, Polireddy K, Wu X, Wang T, Ramesh R, Dixon DA, Xu L, Aubé J, Chen Q. 2020. An RNA-binding protein, Hu-antigen R, in pancreatic cancer epithelial to mesenchymal transition, metastasis, and cancer stem cells. Mol Cancer Ther 19:2267–2277. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-19-0822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cordenonsi M, Zanconato F, Azzolin L, Forcato M, Rosato A, Frasson C, Inui M, Montagner M, Parenti AR, Poletti A, Daidone MG, Dupont S, Basso G, Bicciato S, Piccolo S. 2011. The Hippo transducer TAZ confers cancer stem cell-related traits on breast cancer cells. Cell 147:759–772. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.09.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Waddell N, Pajic M, Patch A-M, Chang DK, Kassahn KS, Bailey P, Johns AL, Miller D, Nones K, Quek K, Quinn MCJ, Robertson AJ, Fadlullah MZH, Bruxner TJC, Christ AN, Harliwong I, Idrisoglu S, Manning S, Nourse C, Nourbakhsh E, Wani S, Wilson PJ, Markham E, Cloonan N, Anderson MJ, Fink JL, Holmes O, Kazakoff SH, Leonard C, Newell F, Poudel B, Song S, Taylor D, Waddell N, Wood S, Xu Q, Wu J, Pinese M, Cowley MJ, Lee HC, Jones MD, Nagrial AM, Humphris J, Chantrill LA, Chin V, Steinmann AM, Mawson A, Humphrey ES, Colvin EK, Chou A, Australian Pancreatic Cancer Genome Initiative , et al. 2015. Whole genomes redefine the mutational landscape of pancreatic cancer. Nature 518:495–501. doi: 10.1038/nature14169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barron DA, Kagey JD. 2014. The role of the Hippo pathway in human disease and tumorigenesis. Clin Transl Med 3:25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kapoor A, Yao W, Ying H, Hua S, Liewen A, Wang Q, Zhong Y, Wu C-J, Sadanandam A, Hu B, Chang Q, Chu GC, Al-Khalil R, Jiang S, Xia H, Fletcher-Sananikone E, Lim C, Horwitz GI, Viale A, Pettazzoni P, Sanchez N, Wang H, Protopopov A, Zhang J, Heffernan T, Johnson RL, Chin L, Wang YA, Draetta G, DePinho RA. 2014. Yap1 activation enables bypass of oncogenic Kras addiction in pancreatic cancer. Cell 158:185–197. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hao F, Xu Q, Zhao Y, Stevens JV, Young SH, Sinnett-Smith J, Rozengurt E. 2017. Insulin receptor and GPCR crosstalk stimulates YAP via PI3K and PKD in pancreatic cancer cells. Mol Cancer Res 15:929–941. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-17-0023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang S, Zhang L, Purohit V, Shukla SK, Chen X, Yu F, Fu K, Chen Y, Solheim J, Singh PK, Song W, Dong J. 2015. Active YAP promotes pancreatic cancer cell motility, invasion and tumorigenesis in a mitotic phosphorylation-dependent manner through LPAR3. Oncotarget 6:36019–36031. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.5935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pereira B, Billaud M, Almeida R. 2017. RNA-binding proteins in cancer: old players and new actors. Trends Cancer 3:506–528. doi: 10.1016/j.trecan.2017.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schultz CW, Preet R, Dhir T, Dixon DA, Brody JR. 2020. Understanding and targeting the disease-related RNA binding protein human antigen R (HuR). Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA 11:e1581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Srikantan S, Gorospe M. 2011. UneCLIPsing HuR nuclear function. Mol Cell 43:319–321. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jain A, McCoy M, Coats C, Brown SZ, Addya S, Pelz C, Sears RC, Yeo CJ, Brody JR. 2022. HuR plays a role in couble-strand break repair in pancreatic cancer cells and regulates functional BRCA1-associated-ring-domain-1 (BARD1) isoforms. Cancers (Basel) 14:1848. doi: 10.3390/cancers14071848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dhir T, Schultz CW, Jain A, Brown SZ, Haber A, Goetz A, Xi C, Su GH, Xu L, Posey J, Jiang W, Yeo CJ, Golan T, Pishvaian MJ, Brody JR. 2019. Abemaciclib is effective against pancreatic cancer cells and synergizes with HuR and YAP1 inhibition. Mol Cancer Res 17:2029–2041. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-19-0589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Piccolo S, Dupont S, Cordenonsi M. 2014. The biology of YAP/TAZ: Hippo signaling and beyond. Physiol Rev 94:1287–1312. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00005.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wu X, Gardashova G, Lan L, Han S, Zhong C, Marquez RT, Wei L, Wood S, Roy S, Gowthaman R, Karanicolas J, Gao FP, Dixon DA, Welch DR, Li L, Ji M, Aubé J, Xu L. 2020. Targeting the interaction between RNA-binding protein HuR and FOXQ1 suppresses breast cancer invasion and metastasis. Commun Biol 3:193. doi: 10.1038/s42003-020-0933-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Abdelmohsen K, Gorospe M. 2010. Posttranscriptional regulation of cancer traits by HuR. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA 1:214–229. doi: 10.1002/wrna.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ratnadiwakara M, Anko ML. 2018. mRNA stability assay using transcription inhibition by actinomycin D in mouse pluripotent stem cells. Bio Protoc 8:e3072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lebedeva S, Jens M, Theil K, Schwanhäusser B, Selbach M, Landthaler M, Rajewsky N. 2011. Transcriptome-wide analysis of regulatory interactions of the RNA-binding protein HuR. Mol Cell 43:340–352. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mukherjee N, Corcoran DL, Nusbaum JD, Reid DW, Georgiev S, Hafner M, Ascano M, Tuschl T, Ohler U, Keene JD. 2011. Integrative regulatory mapping indicates that the RNA-binding protein HuR couples pre-mRNA processing and mRNA stability. Mol Cell 43:327–339. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tang Z, Kang B, Li C, Chen T, Zhang Z. 2019. GEPIA2: an enhanced web server for large-scale expression profiling and interactive analysis. Nucleic Acids Res 47:W556–W560. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Richards NG, Rittenhouse DW, Freydin B, Cozzitorto JA, Grenda D, Rui H, Gonye G, Kennedy EP, Yeo CJ, Brody JR, Witkiewicz AK. 2010. HuR status is a powerful marker for prognosis and response to gemcitabine-based chemotherapy for resected pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma patients. Ann Surg 252:499–505. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181f1fd44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zeng Q, Hong W. 2008. The emerging role of the Hippo pathway in cell contact inhibition, organ size control, and cancer development in mammals. Cancer Cell 13:188–192. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yan H, Yu C-C, Fine SA, Youssof AL, Yang Y-R, Yan J, Karg DC, Cheung EC, Friedman RA, Ying H, Chen EI, Luo J, Miao Y, Qiu W, Su GH. 2021. Loss of the wild-type KRAS allele promotes pancreatic cancer progression through functional activation of YAP1. Oncogene 40:6759–6771. doi: 10.1038/s41388-021-02040-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Singh A, Greninger P, Rhodes D, Koopman L, Violette S, Bardeesy N, Settleman J. 2009. A gene expression signature associated with “K-Ras addiction” reveals regulators of EMT and tumor cell survival. Cancer Cell 15:489–500. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Collisson EA, Sadanandam A, Olson P, Gibb WJ, Truitt M, Gu S, Cooc J, Weinkle J, Kim GE, Jakkula L, Feiler HS, Ko AH, Olshen AB, Danenberg KL, Tempero MA, Spellman PT, Hanahan D, Gray JW. 2011. Subtypes of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma and their differing responses to therapy. Nat Med 17:500–503. doi: 10.1038/nm.2344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bailey P, Chang DK, Nones K, Johns AL, Patch A-M, Gingras M-C, Miller DK, Christ AN, Bruxner TJC, Quinn MC, Nourse C, Murtaugh LC, Harliwong I, Idrisoglu S, Manning S, Nourbakhsh E, Wani S, Fink L, Holmes O, Chin V, Anderson MJ, Kazakoff S, Leonard C, Newell F, Waddell N, Wood S, Xu Q, Wilson PJ, Cloonan N, Kassahn KS, Taylor D, Quek K, Robertson A, Pantano L, Mincarelli L, Sanchez LN, Evers L, Wu J, Pinese M, Cowley MJ, Jones MD, Colvin EK, Nagrial AM, Humphrey ES, Chantrill LA, Mawson A, Humphris J, Chou A, Pajic M, Scarlett CJ, Australian Pancreatic Cancer Genome Initiative , et al. 2016. Genomic analyses identify molecular subtypes of pancreatic cancer. Nature 531:47–52. doi: 10.1038/nature16965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nicolle R, Blum Y, Duconseil P, Vanbrugghe C, Brandone N, Poizat F, Roques J, Bigonnet M, Gayet O, Rubis M, Elarouci N, Armenoult L, Ayadi M, de Reyniès A, Giovannini M, Grandval P, Garcia S, Canivet C, Cros J, Bournet B, Buscail L, Moutardier V, Gilabert M, Iovanna J, Dusetti N. 2020. Establishment of a pancreatic adenocarcinoma molecular gradient (PAMG) that predicts the clinical outcome of pancreatic cancer. EBioMedicine 57:102858. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2020.102858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang K, Pomyen Y, Barry AE, Martin SP, Khatib S, Knight L, Forgues M, Dominguez DA, Parhar R, Shah AP, Bodzin AS, Wang XW, Dang H. 2020. AGO2 mediates MYC mRNA stability in hepatocellular carcinoma. Mol Cancer Res 18:612–622. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-19-0805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ritchie ME, Phipson B, Wu D, Hu Y, Law CW, Shi W, Smyth GK. 2015. limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res 43:e47. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jain A, Agostini LC, McCarthy GA, Chand SN, Ramirez A, Nevler A, Cozzitorto J, Schultz CW, Lowder CY, Smith KM, Waddell ID, Raitses-Gurevich M, Stossel C, Gorman YG, Atias D, Yeo CJ, Winter JM, Olive KP, Golan T, Pishvaian MJ, Ogilvie D, James DI, Jordan AM, Brody JR. 2019. Poly (ADP) ribose glycohydrolase can be effectively targeted in pancreatic cancer. Cancer Res 79:4491–4502. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-18-3645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Koster J, Rahmann S. 2018. Snakemake—a scalable bioinformatics workflow engine. Bioinformatics 34:3600. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bray NL, Pimentel H, Melsted P, Pachter L. 2016. Near-optimal probabilistic RNA-seq quantification. Nat Biotechnol 34:525–527. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Erlich Y, Mitra PP, delaBastide M, McCombie WR, Hannon GJ. 2008. Alta-Cyclic: a self-optimizing base caller for next-generation sequencing. Nat Methods 5:679–682. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cock PJA, Fields CJ, Goto N, Heuer ML, Rice PM. 2010. The Sanger FASTQ file format for sequences with quality scores, and the Solexa/Illumina FASTQ variants. Nucleic Acids Res 38:1767–1771. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp1137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Biankin AV, Waddell N, Kassahn KS, Gingras M-C, Muthuswamy LB, Johns AL, Miller DK, Wilson PJ, Patch A-M, Wu J, Chang DK, Cowley MJ, Gardiner BB, Song S, Harliwong I, Idrisoglu S, Nourse C, Nourbakhsh E, Manning S, Wani S, Gongora M, Pajic M, Scarlett CJ, Gill AJ, Pinho AV, Rooman I, Anderson M, Holmes O, Leonard C, Taylor D, Wood S, Xu Q, Nones K, Fink JL, Christ A, Bruxner T, Cloonan N, Kolle G, Newell F, Pinese M, Mead RS, Humphris JL, Kaplan W, Jones MD, Colvin EK, Nagrial AM, Humphrey ES, Chou A, Chin VT, Chantrill LA, Australian Pancreatic Cancer Genome Initiative , et al. 2012. Pancreatic cancer genomes reveal aberrations in axon guidance pathway genes. Nature 491:399–405. doi: 10.1038/nature11547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Witkiewicz AK, McMillan EA, Balaji U, Baek GHee, Lin W-C, Mansour J, Mollaee M, Wagner K-U, Koduru P, Yopp A, Choti MA, Yeo CJ, McCue P, White MA, Knudsen ES. 2015. Whole-exome sequencing of pancreatic cancer defines genetic diversity and therapeutic targets. Nat Commun 6:6744. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cerami E, Gao J, Dogrusoz U, Gross BE, Sumer SO, Aksoy BA, Jacobsen A, Byrne CJ, Heuer ML, Larsson E, Antipin Y, Reva B, Goldberg AP, Sander C, Schultz N. 2012. The cBio Cancer Genomics Portal: an open platform for exploring multidimensional cancer genomics data. Cancer Discov 2:401–404. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gao J, Aksoy BA, Dogrusoz U, Dresdner G, Gross B, Sumer SO, Sun Y, Jacobsen A, Sinha R, Larsson E, Cerami E, Sander C, Schultz N. 2013. Integrative analysis of complex cancer genomics and clinical profiles using the cBioPortal. Sci Signal 6:pl1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material. Download mcb.00018-22-s0001.xlsx, XLSX file, 0.05 MB (48.7KB, xlsx)

Data Availability Statement

The data set supporting the conclusions of this article are available in the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO), under the accession numbers GSE167525 for RNA-Seq data (raw fastq files, optimized count data, and TPM files) and GSE166951 for RNP-IP chip microarray files. All other data sets are publicly available from corresponding web addresses.