ABSTRACT

Cryptosporidium is a leading cause of moderate-to-severe diarrhea in children, which is one of the major causes of death in children under 5 years old. Nitazoxanide is the only FDA-approved treatment for cryptosporidiosis. However, it has limited efficacy in immunosuppressed patients and malnourished children. Therefore, it is urgent to develop novel therapies against this parasite. RNA interference-mediated therapies are emerging as novel approaches for the treatment of infectious diseases. We have developed a novel method to silence essential genes in Cryptosporidium using single-stranded RNA (ssRNA)/Argonaute (Ago) complexes. In this work we conducted proof-of-concept studies to test the anticryptosporidial activity of these complexes by silencing Cryptosporidium parvum nucleoside diphosphate kinase (NDK) using in vitro and in vivo models. We demonstrated that a 3-day treatment with anti-sense NDK ssRNA/Ago decreased parasite burden by ~98% on infected cells. In vivo studies showed that ssRNA/Ago complexes encapsulated in lipid nanoparticles can be delivered onto intestinal epithelial cells of mice treated orally. In addition a cryptosporidiosis-mouse model showed that treatment with NDK ssRNA/Ago complexes reduced oocyst shedding in 4/5 SCID/beige mice during the acute phase of the infection. Our findings highlight the potential use of antisense RNA-based therapy as an alternative approach to cryptosporidiosis treatment.

KEYWORDS: Cryptosporidium, cryptosporidiosis, gene silencing, Argonaute, NDK, siRNA

INTRODUCTION

Cryptosporidium is a leading cause of moderate-to-severe diarrhea in children (1–3). Nitazoxanide is the only FDA-approved medication available for cryptosporidiosis treatment, but it has limited efficacy in malnourished children and is ineffective in immunocompromised individuals. More effective treatment options are urgently needed (4, 5). We have developed a method to silence genes in this parasite using preassembled complexes of Cryptosporidium single-stranded RNA and the human enzyme Argonaute 2 (ssRNA/Ago) (6, 7). We have used this method to determine the role of selected genes during Cryptosporidium infection (8–10).

Our silencing studies indicated that silencing of C. parvum nucleoside diphosphate kinase (cgd4_1940) reduces proliferation and egress of Cryptosporidium parasites (8). Nucleoside diphosphate kinase (NDK) is a housekeeping enzyme that balances cellular nucleoside triphosphate (NTP) pools by catalyzing the reversible transfer of γ-phosphate from NTPs to nucleoside diphosphates (NDPs) (11). However, several studies have demonstrated that NDKs are also involved in other essential biological processes; for example, microbial NDKs have roles in protein histidine phosphorylation, DNA cleavage/repair, and gene regulation (11). In Leishmania and microbial infections NDK has been linked with modulation of the host immune response (12, 13). In addition, downregulation of the NDK gene arrests cell proliferation in cancer cell lines (14). Recent studies have demonstrated the feasibility of delivering small interfering RNA (siRNA) to the mouse intestines and human epithelial cells to block expression of intestinal genes (15, 16). We hypothesized that single-stranded RNA (ssRNA/Ago) complexes targeting Cryptosporidium NDK may be used orally to treat Cryptosporidium infection. However, siRNA therapeutics for the treatment of intestinal pathogens face yet unresolved problems, such as siRNA stability in the intestine, off-target effects, successful siRNA delivery into the pathogen in vivo, and nonspecific activation of the host immune system (17). We conducted a proof-of-concept study to evaluate the feasibility of using RNA-based therapy against cryptosporidiosis. We conducted experiments to show ssRNA/Ago complex delivery onto infected cells. Also, we tested gene silencing on intracellular parasites and evaluated the anticryptosporidial effect of ssRNA/Ago complexes in a mouse model of cryptosporidiosis.

RESULTS

NDK ssRNA/Ago complexes induce silencing in Cryptosporidium.

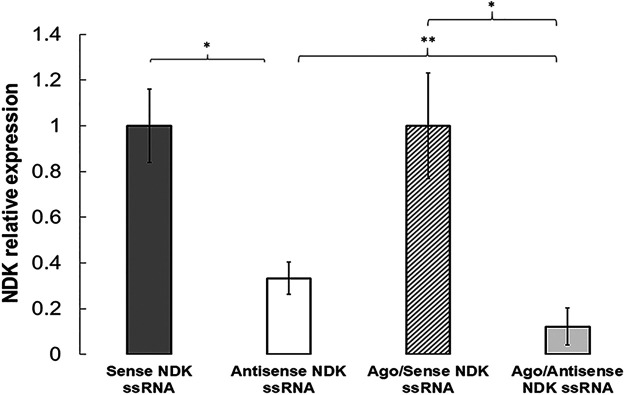

We induced silencing of NDK by transfecting NDK antisense ssRNA/Ago complexes into Cryptosporidium parvum oocysts (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Our reverse transcription-quantitative PCR (qRT-PCR) results showed that complexes targeting NDK mRNA reduced expression by 85% (Fig. 1). In contrast, naked NDK ssRNA only reduced NDK expression by 65%, and sense NDK ssRNA or scramble ssRNA did not show any effect on NDK mRNA levels. Thus, antisense NDK ssRNA, with or without Ago, significantly reduces the expression of NDK. Silencing activity of naked ssRNA may be attributed to RNAse activity; however, the results showed that Ago-dependent silencing enhances the potency of anti-sense NDK ssRNA. This result may be explained by the stability and protection of ssRNA provided by Ago (18) and by its potent slicer activity (19).

FIG 1.

NDK silencing in Cryptosporidium. Oocysts were treated with sense NDK ssRNA (dark gray), antisense NDK ssRNA (white), sense NDK ssRNA/Ago (diagonal lines), and antisense NDK ssRNA/Ago (light gray). Samples were analyzed by qRT-PCR, and NDK mRNA expression was normalized compared to Cryptosporidium GAPDH and NDK expression compared to untreated controls using the ΔΔCT method. (*, P ≤ 0.05; **, P ≤ 0.001).

ssRNA/Ago is delivered to infected cells.

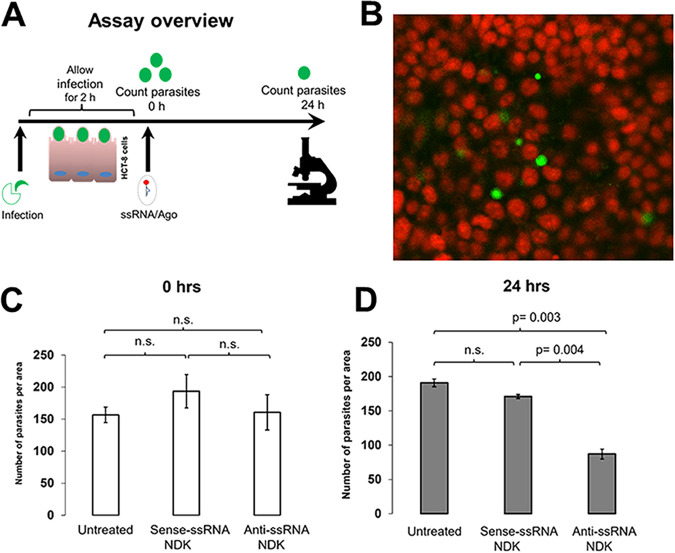

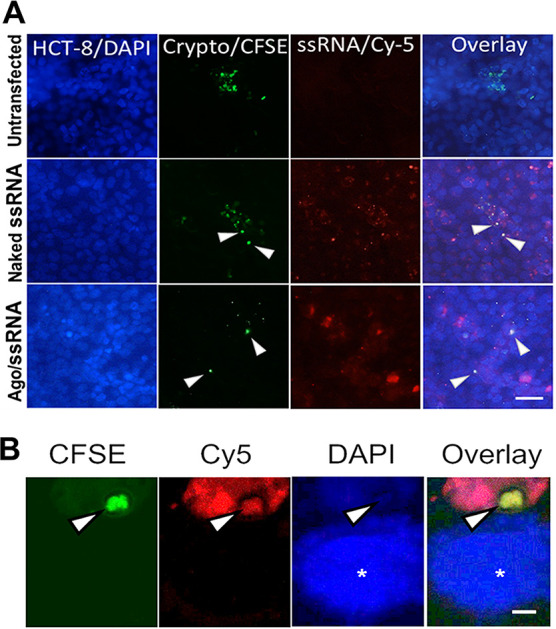

We used carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE)-labeled parasites to infect human ileocecal cells (HCT-8 cells). CFSE is an intracellular dye that only becomes fluorescent in live organisms and thus is used to track parasites on infected cells (20). After the infection, we treated intestinal cells with Cy5-ssRNA/Ago encapsulated in liposomes. Fluorescence microscopy showed that Cy5-ssRNA/Ago complexes are widely distributed among HCT-8 cells, and some of these Cy5 labeled complexes are colocalized with infected cells (Fig. 2A). In addition, confocal studies confirmed transfection of intracellular parasites (Fig. 2B and Fig. S2). These results suggest that the parasitophorous vacuole of the parasite is susceptible to transfection and therefore would not be a barrier for treating intracellular parasites with ssRNA/Ago complexes.

FIG 2.

NDK ssRNA/Ago complexes localize to infected cells. HCT-8 cells were infected with fluorescent Cryptosporidium prestained with the vital dye CFSE (green). After 24 h of infection, cells were transfected with Cy-5 labeled ssRNA (red)/Ago complexes. (A) For fluorescence microscopy, HCT-8 cells were counterstained with DAPI (blue). White arrows show the localization of intracellular parasites. Colocalization is demonstrated with ssRNA-Cy5 (naked) and Ago/ssRNA-Cy5 (complexes). Scale bar = 40 μm. (B) For confocal microscopy, HCT-8 cells cultured on coverslips were treated as before. Nuclei were stained with DAPI (white asterisk [*]). The white arrow points to an intracellular parasite, which was transfected with ssRNA/Ago complexes. Scale bar = 5 μm.

ssRNA/Ago treatment reduces Cryptosporidium infection in vitro.

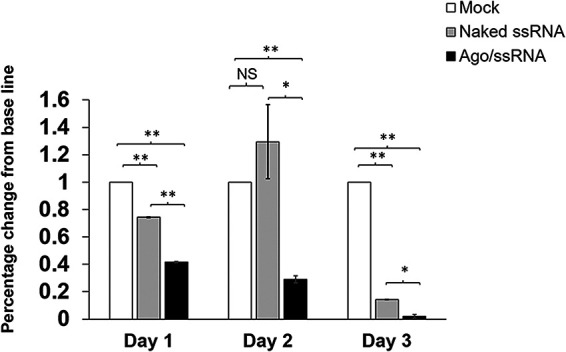

We evaluated anticryptosporidial activity of ssRNA/Ago after infection by quantitative microscopy using a fluorescent dye which has been previously validated for quantitative tracking of Cryptosporidium in cell cultures (20). In our infection assay, we used prestained sporozoites to infect cells for 2 h. After infection, ssRNA/Ago complexes were added to infected cells, and some samples were fixed immediately to determine basal infection by microscopy; other samples were fixed until the next day to determine parasite reduction after 24 h (Fig. 3A). Since compromised membranes of dead parasites leak dye, only live parasites are still fluorescent, and thus they can be easily distinguished from host cells and counted by microscopy (Fig. 3B, Data set S2). After the analysis, we did not observe significant differences in the number of parasites comparing sense NDK-ssRNA/Ago- and antisense NDK-ssRNA/Ago-treated samples and untreated samples (Fig. 3C); however, after 24 h we observed a significant reduction, ~50%, only in samples treated with antisense NDK-ssRNA/Ago (Fig. 3D). Partial reduction may be explained by the use of suboptimal doses. However, the results showed the specific anticryptosporidial effect of antisense NDK ssRNA/Ago (Fig. 3D). In a different experiment, we evaluated the antiparasitic activity of complexes but used different doses of ssRNA/Ago to treat infected cells. We added complexes to infected cells up to 3 days (3 doses) but used reverse transcriptase PCR (qRT-PCR) to evaluate parasite reduction. The rationale for this approach is the rapid turnover and postmortem decay of cellular mRNA observed in Cryptosporidium; thus, qRT-PCR is a very sensitive method that has previously been used to evaluate Cryptosporidium viability (21). For these experiments HCT-8 cells were infected with sporozoites. After 24 h, silencing complexes were added daily up to for 3 days, and then RNA was extracted and the number of parasites was evaluated by qRT-PCR; differences are shown as the percentage change from baseline. Treatment with silencing complexes quickly reduced the number of parasites as measured by qRT-PCR. After treating infected cells with antisense NDK ssRNA/Ago, we observed a 60% reduction in parasite mRNA after day 1, 75% at day 2, and 98% by day 3 (Fig. 4). Cells treated with naked RNA (free Ago) showed only a moderate reduction at day 1 and no effect by day 2; however, we observed an ~50% reduction in parasite numbers by day 3. We expected this weak silencing or no effect of naked ssRNA observed at day 1 and 2 due to susceptibility of naked ssRNA to degradation. However, partial silencing was observed by day 3; this partial silencing is explained by the cumulation of antisense RNA that circumvent RNase activity. These results confirm that Ago enhances the anticryptosporidial activity of ssRNA/Ago and suggest the feasibility of using complexes as potential treatment of cryptosporidiosis in vivo.

FIG 3.

In vitro anticryptosporidial activity of ssRNA/Ago by fluorescent quantitative microscopy. (A) Schematic illustration of anticryptosporidial assay. HCT-8 cells were infected with fluorescent-labeled Cryptosporidium for 2 h. After infection, cells were treated with anti-NDK ssRNA/Ago, sense-ssNDK/Ago (control), or untreated (Fig. S2A). (B) For fluorescence microscopy, HCT-8 cells were counterstained with propidium iodide (red), and parasites stained with vital dye CFSE (green). (C and D) After treatment, cells were fixed at 0 h and 24 h, and then the total number of parasites was evaluated by fluorescent quantitative microscopy (Fig. S2B).

FIG 4.

Anticryptosporidial activity of ssRNA/Ago by qRT-PCR. HCT-8 cells were infected with Cryptosporidium. After 24 h, infected cells were treated daily with anti-NDK ssRNA (gray bar) or anti-NDK ssRNA/Ago complexes (black bars) or were mock-infected (white bars). The total number of parasites was calculated by qRT-PCR; results of triplicates are expressed as the percentage change from baseline. (*, P ≤ 0.05; **, P ≤ 0.005).

ssRNA complexes are delivered to mouse intestine.

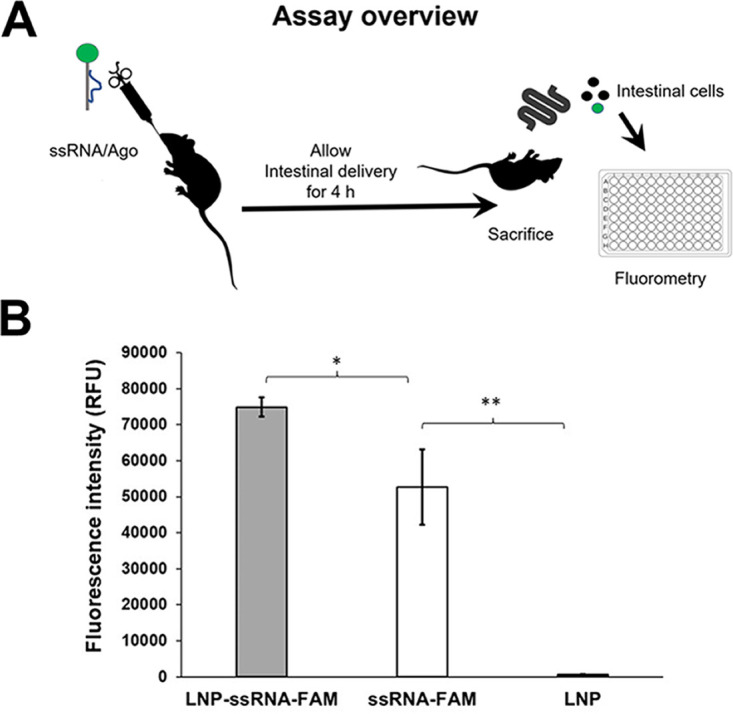

We investigated whether ssRNA/Ago complexes can reach mouse intestines after oral administration (Fig. 5A). For these experiments, we treated severe combined immunodeficiency/beige (SCIDbg) mice with labeled ssRNA, and then we analyzed ssRNA/Ago delivery with or without lipidic encapsulation on intestinal cells by fluorometry (Fig. 5A). Both naked ssRNA/Ago and complexes were detected on mouse intestinal cells 4 h after treatment. However, fluorometry experiments showed a stronger signal with encapsulated ssRNA/Ago (Fig. 5B). These results suggest that lipidic nanoparticles protect ssRNA/Ago during gastrointestinal transit since labeled complexes reach the site of Cryptosporidium infection within a few hours; however, additional studies should be conducted to confirm ssRNA/Ago uptake on intestinal cells.

FIG 5.

Intestinal cells of mice treated with labeled ssRNA. (A) Schematic illustration of mouse model. Mice treated orally with labeled ssRNA-FAM/Ago complexes encapsulated in lipid-based nanoparticles (LNP). (B) After 4 h, intestinal cells were obtained and cellular uptake was analyzed by fluorometry. Fluorescence intensity is measured in relative fluorescence units (RFU). Gray bar, mice treated with ssRNA/Ago complexes encapsulated in LNP; white bar, mice treated with ssRNA/Ago complexes without LNP; black bar, mice treated only with LNP. (*, P ≤ 0.05; **, P ≤ 0.001).

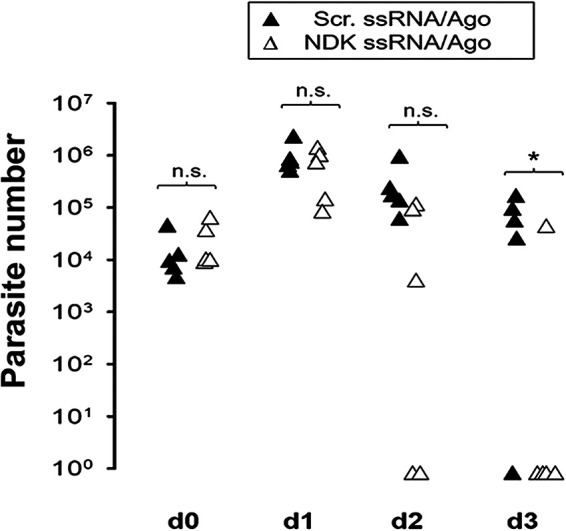

Anti-NDK ssRNA reduces the parasite burden in infected mice.

We evaluated the anticryptosporidial activity of ssRNA/Ago complexes in SCIDbg mice infected with Cryptosporidium. After oocyst shedding was confirmed, mice were treated by gavage with anti-NDK/Ago or scramble NDK/ago beginning on day 4 postinfection. In this preliminary experiment we analyzed parasites in stool samples obtained during the acute phase of the infection; this phase has been used (in the mouse-SCID model) for initial screening of new compounds with anticryptosporidial activity (22). Four of five mice treated with NDK/Ago cleared the infection by day 3 (Fig. 6). In contrast, four of five mice treated with scrambled ssRNA/Ago continued to shed oocysts at levels similar to those of untreated mice (Fig. 6). Since parasite numbers were low during the chronic phase in control animals, it was not possible to evaluate the effect of ssRNA/Ago beyond treatment. Therefore, other models should be considered (e.g., malnourished mouse model) to confirm the anticryptosporidial effect of ssRNA/Ago complexes during chronic phases of infection. Overall, our experiment confirms that NDK ssRNA/Ago has anticryptosporidial activity in vivo and suggests the feasibility of using antisense therapy to treat cryptosporidiosis.

FIG 6.

Parasite burden in stool samples of mice orally treated with ssRNA/Ago. Mice were infected with 1 × 106 parasites. After 4 days of infection, mice were treated orally with daily ssRNA/Ago complexes encapsulated in LPN. Parasite burden in 25 mg of stool was evaluated by qPCR. Black triangles, anti-NDK ssRNA/Ago complexes; white triangles, scramble ssRNA/Ago. *, P ≤ 0.05.

DISCUSSION

We induced gene silencing in Cryptosporidium using ssRNA/Ago complexes and showed that knocking down NDK expression blocks parasite proliferation (8). Here, we demonstrated the feasibility of delivering ssRNA/Ago complexes to the intestines of mice and demonstrated anticryptosporidial activity of antisense NDK ssRNA/Ago complex in vitro and in vivo. Cryptosporidium lacks RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) enzymes (23); therefore, our silencing strategy is based on the reconstitution of the small interfering RNA (siRNA) pathway by forming a minimal RNA silencing complex (7).

Recent studies have shown that siRNAs can be used therapeutically to block the synthesis of disease-causing proteins and to reduce proliferation of infectious agents (24). However, the delivery of nucleic acids by the oral route poses potential hurdles, including instability of the RNA or poor cellular uptake, thus compromising efficacy under physiological conditions. In addition, high concentrations of siRNA could also induce off-target effects or nonspecific inflammatory responses (25). We hypothesized that ssRNA/Ago complexes could induce silencing at lower concentrations. In vitro studies confirmed that low concentrations of ssRNA preloaded onto Ago induce potent silencing in transfected parasites (Fig. 1). Previous studies have shown that Ago binding protects ssRNA from degradation (18). We demonstrated that oocysts (Fig. S1S) and intracellular parasites are susceptible to transfection using a cationic lipid-based carrier system. This kind of liposome attaches to negatively charged surfaces and fuses directly to membranes. Therefore, since Cryptosporidium organisms do not have caveolins, we speculate that ssRNA/Ago complexes are introduced by clathrin-mediated endocytosis where the liposomes are fused with parasitophorous membrane and membranes of extracellular forms. Our confocal studies confirmed that ssRNA/Ago complexes cross membranes of intracellular and extracellular parasites (Fig. 2B and Fig. S2). However, additional studies should be conducted to understand how ssRNA/Ago complexes cross membranes on infected cells. For silencing experiments, we targeted Cryptosporidium nucleoside diphosphate kinase (NDK) since our previous studies have shown that NDK silencing blocks parasite proliferation without cytotoxic effects (8). Our in vitro experiments confirmed these observations by reducing parasite proliferation on infected cells (Fig. 3D) and showed that a daily treatment (up to 3 days) enhances anticryptosporidial activity (Fig. 4). Since previous studies have shown that siRNA encapsulated in lipidic nanoparticles is efficiently delivered orally on mouse intestines (15), we hypothesized that ssRNA/Ago could be delivered in vivo using same cationic lipids used in our in vitro experiments. Uptake experiments (Fig. 5B) confirmed that cationic lipids enhance delivery of complexes on epithelial cells, suggesting the feasibility to use NDK ssRNA/Ago to reduce infection in vivo. To evaluate anticryptosporidial activity in vivo, we conducted a preliminary experiment using a Cryptosporidiosis-mouse model to test if a daily treatment with NDK ssRNA/Ago (using the same doses) had anticryptosporidial activity on infected mice. Our results showed that oral treatment with complexes led to a significant reduction of parasites by day 3 in all mice, with 4 of 5 mice showing no infection (Fig. 6). However, further optimization of dose, schedule, and duration of therapy may be needed prior to initiating studies in large animal models. Our in vitro and in vivo experiments show the anticryptosporidial effect of NDK ssRNA/complexes; this effect may be attributed to the inhibition of several biological functions in which NDK may be involved. Is well known that NDKs have an important role in nucleotide synthesis. However, recent genetic experiments in this parasite showed that under certain conditions, Cryptosporidium may not require purine nucleotide synthesis (26). Those studies proposed that the parasite has evolved to import purine nucleotides, making purine salvage dispensable. Thus, the effect of NDK inhibition might be related to other NDK functions; for example, this enzyme has also been implicated in the evasion of immune response, apoptosis, and inflammation. Propionibacterium gingivalis-NDK inhibits extracellular-ATP (eATP)/P2X7-receptor-mediated cell death in gingival epithelial cells (GECs) via eATP hydrolysis (27). For Leishmania amazonensis, NDK participates in immune evasion by preventing eATP-mediated macrophage death (13). Specifically, Leishmania-secreted NDK was found to keep the host cell membrane integrity intact and stabilized the mitochondrial membrane potential in macrophages, thus preventing host-cell death (12).

A number of highly effective compounds have been developed for Cryptosporidiosis treatment (3, 28, 29). However, so far, all have failed to progress to clinical trials due to unanticipated adverse effects (30). Additional avenues are needed for novel drugs for cryptosporidiosis. Our work is based on the use of RNA interference (RNAi) as a drug. Compared to other small-molecule drugs or antibody-based treatments, ssRNA/Ago complexes can potentially have improved specificity determined by complementary base pairing, since transcriptomic data from Cryptosporidium hominis and C. parvum is available; then, ssRNA can be easily designed for other potential targets and be tested for anticryptosporidial activity. Despite the remaining challenges for using RNAi technology in therapeutics, recent studies support the feasibility of using RNAi against infectious agents by the development of novel strategies to enhance the potency, stability, and delivery of nucleic acids (24). This work describes a novel strategy for RNAi by using ssRNA/Ago complexes to reduce Cryptosporidium infection. Since our experiments for the first time tested this strategy on intestinal cells, data from this work will be useful for other groups who wish to explore the use of ssRNA/Ago complexes in therapeutics against other enteric pathogens.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

ssRNA/Ago assembling and silencing experiments.

We induced gene silencing in Cryptosporidium oocysts with ssRNA/Ago complexes or naked ssRNA as described before (6, 7). To assemble ssRNA/Ago complexes, we used capped 21-nucleotide (nt) ssRNA from Cryptosporidium (Integrated DNA Technologies, Cornville, AZ) and recombinant Argonaute (Ago2) protein as described (7). Briefly, ssRNA-hAgo2 complexes were assembled by combining 2.5 μL (100 nM) of ssRNA, 2 μL (62.5 ng/μL) of hAgo2 protein (Sino Biologicals, North Wales, PA), and 15 μL of assembling buffer [2 mM Mg (OAc)2, 150 mM KOHAc, 30 mM HEPES, 5 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), nuclease-free water]. The mixture was incubated for 1 h at room temperature and then used for transfection experiments. For parasite transfection, lyophilized protein transfection reagent (PTR) (Pro-Ject; Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL) was reconstituted in 1 mL of HEPES 100 μm and then used to encapsulate complexes. The ssRNA/Ago or naked ssRNA was encapsulated by adding 15 μL of PTR suspension and incubating the mixture for 30 min at room temperature. To transfect parasites, 5 × 105 oocysts diluted in 5 μL of water were added to each reaction tube containing complexes in PTR, and then samples were incubated at room temperature for 1 h. After incubation, we sensitized oocysts (for transfection) and activated slicer activity of hAgo2 by incubating the sample at 37°C for 2 h. After transfection, the reaction mixture was discarded after centrifuging the sample at 500 × g fir 10 min, and then the pellet of parasites was recovered and stored at −20°C for RNA extraction as described below. Then, 21 nt NDK antisense 5′-CGUGGAUUGUGGGCUAGUdTdT-3′ or sense sequences (negative control) were used to target the NDK gene (Table S1).

RNA extraction from transfected Cryptosporidium and ssRNA/Ago silencing by RT-PCR.

Prior to RNA isolation, transfected parasites (previously stored at −20°C) were thawed at room temperature (RT) and then incubated at 95°C for 2 min. Total RNA was extracted using the Qiagen RNeasy Plus minikit (Qiagen, Valencia CA). The RNA was eluted from purification columns with 100 μL of RNase-free water. The RNA concentration was determined by spectrophotometry using a NanoDrop 100 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham MA). Silencing in RNA from transfected oocysts was analyzed by qRT-PCR using a qScript one-step SYBR green qRT-PCR kit, low ROX (Quanta BioSciences/VWR, Radnor, PA). For amplification reactions we used 2 μL of purified RNA template (20 ng/μL), 5 μL of the one-step SYBR green master mix, 0.25 μL of each primer at a 10 μM concentration, 0.25 μL of the qScript one-step reverse transcriptase, and 4.25 μL of nuclease-free water for a total of 10 μL of mix per sample. The qRT-PCR mixture (total volume, 12 μL) was transferred to 96-well reaction plates (0.1 mL), and RT-PCR amplification conducted with a 7500 Fast real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) under the following cycling conditions: 50°C for 15 min, 95°C for 5 min, then 50 cycles of 95°C for 15 s and 63°C for 1 min, followed by a melting point analysis (95°C for 15 s, 60°C for 1 min, 95°C for 15 s, and 60°C for 15 s). qRT-PCR values were normalized to Cryptosporidium GAPDH (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; housekeeping gene). To calculate fold changes between NDK from control samples and NDK from silenced samples, we used the ΔΔCT method (31). The primers used for RT-PCR are indicated in the supplemental data (Table S2).

ssRNA/Ago transfection to infected HCT-8 cells by fluorescence microscopy.

Human ileocecal cells (HCT-8 cells, ATCC, Manassas, VA) and Cryptosporidium parvum parasites (Waterborne, Inc., New Orleans, LA) were used for in vitro studies. HCT-8 cells were cultured in 25-cm flasks with 5 mL of complete medium (RPMI 1640 medium; Gibco/Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Stemcell Technologies, Vancouver, Canada) and 1× antibiotic/antimycotic solution (Gibco/Thermo Fisher Scientific) at 37°C. After overnight culture, HCT-8 cells were harvested and seeded (~5 × 105 per well) onto coverslips placed in 6-well plates (Costar, Corning, NY) at 37°C for 24 h. For excystation, oocysts were washed 3 times with 250 μL of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), resuspended in 50 μL of acidic water (pH 2 to 3), and incubated for 10 min on ice. Excystation medium (complete medium supplemented with 0.8% taurocholate) was added to the sample, which was then incubated for 1 h at 37°C. The released sporozoites were stained by adding 4 μL carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE). Sporozoites (~5 × 105) were added to the HCT-8 cells (ratio, 1:1). After 2 h, sporozoite medium was removed, and 500 μL of complete medium was added. The following day, labeled-ssRNA (ssRNA-Cy5 IDT) complexes were prepared and encapsulated in PTR. The labeled complexes in PTR were used to transfect infected cells for 24 h (at 37°C). After cell transfection, medium was removed from chambers, and coverslips were placed in petri dishes for washing (3 rinses with 200 μL of PBS). Next, 1 mL of fixation solution (BD Cytofix solution; Becton and Dickson, Franklin Lakes, NJ) was added to the cells. Fixed cells were washed 3 times with 200 μL of PBS as before. After washing, the PBS was removed, and coverslips were counterstained and mounted onto microscope slides using 20 μL of DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) mounting medium (Vectashield; Vector Laboratories, Inc., Burlingame, CA). Samples were evaluated by fluorescence microscopy, using a Nikon eclipse 80i microscope and the imaging software NIS Elements (Nikon USA, Melville, NY). For confocal experiments, samples were prepared as before and evaluated by confocal microscopy using a Zeiss 880 confocal microscope and Fiji software (ImageJ, https://fiji.sc).

Anticryptosporidial activity of ssRNA/Ago by quantitative fluorescence microscopy.

We evaluated anticryptosporidial activity of NDK ssRNA/Ago complexes in vitro. For quantification, the total number of parasites was counted on infected cells treated with sense NDK ssRNA/Ago or antisense NDK ssRNA/Ago (or untreated) by fluorescence microscopy. For these experiments, first, HCT-8 cells (1 × 104) were cultured in 96-well plates overnight. The next day, cell monolayers (confluence, 80%) were infected with excysted sporozoites (1 × 104) which had been prestained with vital dye CFSE (as described above). After 2 h of infection, culture medium was removed, and then PTR-encapsulated complexes (ssRNA 100 nM/Ago 62.5 ng/μL) diluted in 250 μL of fresh RPMI medium were added to each well. After treatment, samples were incubated at 37°C overnight. After 0 and 24 h, RPMI medium was removed, and cells were washed and fixed with BD Cytofix-Crytoperm (Fisher-Scientific) solution for 30 min. Fixed cells on 96-well plates were washed and suspended in 200 μL of PBS and then counterstained with propidium iodide (Thermo-Fisher) and were stored at 4°C until analysis. For the microscopy, samples were analyzed at the University of Texas Medical Branch (UTMB) core facility using a Zeiss 880 confocal microscope; images were captured with a 20× lens objective, and the total number of parasites was quantified (area, 1.94 mm by 1.95 mm) using ImageJ processing software (Fiji). For this analysis, noise was subtracted and the watershed option was used to separate aggregated parasites. Parasite numbers were obtained from independent experiments conducted in duplicate; images and additional specifications of microscopy experiments are shown in Fig. S3.

Anticryptosporidial activity of ssRNA/Ago by quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR).

For qRT-PCR experiments, we evaluated parasite reduction on infected cells treated with ssRNA/Ago treatment up to 3 days. For these experiments, HCT-8 cells were infected as described; after infection cells were cultured for 24 h, and then complexes were added (ssRNA 100 nM/Ago 62.5 ng/μL) daily to cultured cells for up to 3 days. Treated cells were incubated and harvested at 24, 48, and 72 h, and then RNA was extracted with the RNeasy Plus kit following the vendor’s instructions, (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). After RNA extraction, samples were transferred to 1.5-mL tubes and stored frozen (–20°C) for subsequent RNA extraction. To evaluate the anticryptosporidial effect of ssRNA/Ago on treated cells, the total number of parasites was calculated (by detecting the 18s Cryptosporidium gene) by qRT-PCR in untreated samples, and then threshold cycle (CT) values were used to calculate the fold change of treated samples (compared to baseline) using the Delta-Delta CT method (2–ΔΔCT). For RT-PCR assays, CT values were normalized using Gapdh as the reference gene. Experiments were conducted in triplicate, and the data are presented as the percentage change from baseline.

Labeled complexes delivered to mouse intestines.

All animal experiments were conducted under a protocol approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Texas Medical Branch. To demonstrate delivery of complexes on mouse intestines, we used a previously described assay to measure ssRNA uptake on intestinal cells (32). For these experiments, we assembled complexes using 6-carboxyfluorescein (FAM)-labeled ssRNA and then treated 4-week-old severe combined immunodeficiency/beige (SCIDbg) mice (Jackson Laboratory, Sacramento, CA) with a single dose of PTR containing FAM-labeled ssRNA/Ago (ssRNA [100 nM]/Ago [125 ng] diluted in 100 μL of PBS) by oral gavage. PBS or naked FAM-labeled ssRNA/Ago encapsulated in PTR was given by gavage as controls. Mice were sacrificed 4 h after the oral dose, and the terminal ileum was collected. Sections of ileum (2 to 4 mm) were transferred to PBS-EDTA solution, and intestinal crypts were isolated using 2 mM EDTA in PBS as described (33). Crypts were washed twice with PBS and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 30 min. We quantified cellular uptake of FAM-labeled ssRNA/Ago by fluorometric assays as described (32). Briefly, ~500 crypts were placed in 5 mL of PBS. Cells were washed twice with PBS and lysed in 400 μL of lysis buffer (1% Triton X-100, 2% SDS in PBS) on ice for 30 min. Lysates were centrifuged (15 min, 14,000 × g, 4°C) to remove cell debris. Then, 200 μL of the supernatant was transferred to a black 96-well plate to measure the fluorescence using a FLUOstar Omega microplate reader (BMG Labtech, Inc., Cary, NC). From the sample, 50 μL was used to determine the protein content using the Micro BCA protein assay (Pierce, Rockford, IL), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. For determination of the mean fluorescence intensity, fluorescent signals were corrected for the amount of protein in the samples.

Treatment of infected mouse model in vivo and parasite quantification by qPCR.

The 5-week-old SCIDbg mice (Jackson Laboratory, Sacramento, CA) were infected by gavage with 5 × 105 C. parvum oocysts (Iowa strain; Waterborne, Inc., New Orleans, LA) contained in 100 μL of PBS as described before (22). Then, 4 days after infection, mice were treated with ssRNA/Ago complexes (prepared as before and suspended in 100 μL of H2O) by oral gavage daily for 3 days. Five animals per group were treated with ssRNA-NDK/Ago, ssRNA scramble/Ago, or PBS. After infection, stool samples were collected at during the acute phase of infection (15 days). For parasite quantification, approximately 20 mg of stool (2 pellets) was collected daily and resuspended in 1 mL of water. The samples were stored at −20°C until subsequent analysis. DNA was extracted and purified from 20 mg (2 pellets) of stool from each mouse using the QIAamp fast DNA stool minikit (Qiagen, Germantown, MD). The concentration of DNA in samples was determined by spectrophotometry. The parasite burden was determined by qPCR (Applied Biosystems 7500 real-time PCR system), using the iTaq Universal SYBR green supermix kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) with 18s primers for C. parvum as described (34). The qPCR assay was conducted under the following conditions: 1 cycle of 20 min at 55°C, 1 cycle of 5 min at 95°C and 15 s at 95°C, and 40 cycles of 1 min at 60°C. An additional dissociation stage was added at the end of the reaction to test the specificity via dissociation curve analysis. Thus, a standard curve was generated from serial dilutions of DNA extracted from a known number of parasites spiked in mouse stool. The total numbers of parasites were calculated with AB7500 software SDS v1.4.

Statistical analysis.

For all RT-PCR experiments, SigmaPlot v12 was used for the statistical analysis. Data were analyzed using the unpaired two-tailed t test and presented as means ± standard deviation (SD). A P value of <0.05 was statistically significant.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

J.O.-M. was supported by a doctoral fellowship from CONTEX program. This work was supported by the Institute for Human Infections and Immunity (IHII) at the University of Texas Medical Branch and by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), National Institute of Health (NIH) grant number R21AI151901.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available online only.

Contributor Information

A. Castellanos-Gonzalez, Email: alcastel@utmb.edu.

Jeroen P. J. Saeij, UC Davis School of Veterinary Medicine

REFERENCES

- 1.Checkley W, White AC, Jr, Jaganath D, Arrowood MJ, Chalmers RM, Chen XM, Fayer R, Griffiths JK, Guerrant RL, Hedstrom L, Huston CD, Kotloff KL, Kang G, Mead JR, Miller M, Petri WA, Jr, Priest JW, Roos DS, Striepen B, Thompson RC, Ward HD, Van Voorhis WA, Xiao L, Zhu G, Houpt ER. 2015. A review of the global burden, novel diagnostics, therapeutics, and vaccine targets for cryptosporidium. Lancet Infect Dis 15:85–94. 10.1016/S1473-3099(14)70772-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khalil IA, Troeger C, Rao PC, Blacker BF, Brown A, Brewer TG, Colombara DV, De Hostos EL, Engmann C, Guerrant RL, Haque R, Houpt ER, Kang G, Korpe PS, Kotloff KL, Lima AAM, Petri WA, Jr, Platts-Mills JA, Shoultz DA, Forouzanfar MH, Hay SI, Reiner RC, Jr, Mokdad AH. 2018. Morbidity, mortality, and long-term consequences associated with diarrhoea from Cryptosporidium infection in children younger than 5 years: a meta-analyses study. Lancet Glob Health 6:e758–e768. 10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30283-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang B, Castellanos-Gonzalez A, White AC, Jr.. 2020. Novel drug targets for treatment of cryptosporidiosis. Expert Opin Ther Targets 24:915–922. 10.1080/14728222.2020.1785432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shoultz DA, de Hostos EL, Choy RK. 2016. Addressing Cryptosporidium infection among young children in low-income settings: the crucial role of new and existing drugs for reducing morbidity and mortality. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 10:e0004242. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ashigbie PG, Shepherd S, Steiner KL, Amadi B, Aziz N, Manjunatha UH, Spector JM, Diagana TT, Kelly P. 2021. Use-case scenarios for an anti-Cryptosporidium therapeutic. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 15:e0009057. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0009057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Castellanos-Gonzalez A, Perry N, Nava S, White AC, Jr.. 2016. Preassembled single-stranded RNA-Argonaute complexes: a novel method to silence genes in Cryptosporidium. J Infect Dis 213:1307–1314. 10.1093/infdis/jiv588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Castellanos-Gonzalez A. 2020. A novel method to silence genes in Cryptosporidium. Methods Mol Biol 2052:193–203. 10.1007/978-1-4939-9748-0_11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Castellanos-Gonzalez A, Martinez-Traverso G, Fishbeck K, Nava S, White AC, Jr.. 2019. Systematic gene silencing identified Cryptosporidium nucleoside diphosphate kinase and other molecules as targets for suppression of parasite proliferation in human intestinal cells. Sci Rep 9:12153. 10.1038/s41598-019-48544-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nava S, White AC, Jr, Castellanos-Gonzalez A. 2019. Cryptosporidium parvum subtilisin-like serine protease (SUB1) is crucial for parasite egress from host cells. Infect Immun 87:e00784-18. 10.1128/IAI.00784-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nava S, Sadiqova A, Castellanos-Gonzalez A, White AC, Jr.. 2020. Cryptosporidium parvum cyclic GMP-dependent protein kinase (PKG): an essential mediator of merozoite egress. Mol Biochem Parasitol 237:111277. 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2020.111277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yu H, Rao X, Zhang K. 2017. Nucleoside diphosphate kinase (Ndk): a pleiotropic effector manipulating bacterial virulence and adaptive responses. Microbiol Res 205:125–134. 10.1016/j.micres.2017.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kolli BK, Kostal J, Zaborina O, Chakrabarty AM, Chang KP. 2008. Leishmania-released nucleoside diphosphate kinase prevents ATP-mediated cytolysis of macrophages. Mol Biochem Parasitol 158:163–175. 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2007.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Spooner R, Yilmaz O. 2012. Nucleoside-diphosphate-kinase: a pleiotropic effector in microbial colonization under interdisciplinary characterization. Microbes Infect 14:228–237. 10.1016/j.micinf.2011.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li S, Hu T, Yuan T, Cheng D, Yang Q. 2018. Nucleoside diphosphate kinase B promotes osteosarcoma proliferation through c-Myc. Cancer Biol Ther 19:565–572. 10.1080/15384047.2017.1416273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ball RL, Bajaj P, Whitehead KA. 2018. Oral delivery of siRNA lipid nanoparticles: fate in the GI tract. Sci Rep 8:2178. 10.1038/s41598-018-20632-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kriegel C, Amiji M. 2011. Oral TNF-alpha gene silencing using a polymeric microsphere-based delivery system for the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. J Control Release 150:77–86. 10.1016/j.jconrel.2010.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hu B, Zhong L, Weng Y, Peng L, Huang Y, Zhao Y, Liang XJ. 2020. Therapeutic siRNA: state of the art. Signal Transduct Target Ther 5:101. 10.1038/s41392-020-0207-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kingston ER, Bartel DP. 2021. Ago2 protects Drosophila siRNAs and microRNAs from target-directed degradation, even in the absence of 2′-O-methylation. RNA 27:710–724. 10.1261/rna.078746.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rivas FV, Tolia NH, Song JJ, Aragon JP, Liu J, Hannon GJ, Joshua-Tor L. 2005. Purified Argonaute2 and an siRNA form recombinant human RISC. Nat Struct Mol Biol 12:340–349. 10.1038/nsmb918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Feng H, Nie W, Bonilla R, Widmer G, Sheoran A, Tzipori S. 2006. Quantitative tracking of Cryptosporidium infection in cell culture with CFSE. J Parasitol 92:1350–1354. 10.1645/GE-853R.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Widmer G, Orbacz EA, Tzipori S. 1999. Beta-tubulin mRNA as a marker of Cryptosporidium parvum oocyst viability. Appl Environ Microbiol 65:1584–1588. 10.1128/AEM.65.4.1584-1588.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Castellanos-Gonzalez A, Sparks H, Nava S, Huang W, Zhang Z, Rivas K, Hulverson MA, Barrett LK, Ojo KK, Fan E, Van Voorhis WC, White AC, Jr.. 2016. A novel calcium-dependent kinase inhibitor, bumped kinase inhibitor 1517, cures cryptosporidiosis in immunosuppressed mice. J Infect Dis 214:1850–1855. 10.1093/infdis/jiw481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abrahamsen MS, Templeton TJ, Enomoto S, Abrahante JE, Zhu G, Lancto CA, Deng M, Liu C, Widmer G, Tzipori S, Buck GA, Xu P, Bankier AT, Dear PH, Konfortov BA, Spriggs HF, Iyer L, Anantharaman V, Aravind L, Kapur V. 2004. Complete genome sequence of the apicomplexan, Cryptosporidium parvum. Science 304:441–445. 10.1126/science.1094786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sajid MI, Moazzam M, Cho Y, Kato S, Xu A, Way JJ, Lohan S, Tiwari RK. 2021. siRNA therapeutics for the therapy of COVID-19 and other coronaviruses. Mol Pharm 18:2105–2121. 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.0c01239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Caffrey DR, Zhao J, Song Z, Schaffer ME, Haney SA, Subramanian RR, Seymour AB, Hughes JD. 2011. siRNA off-target effects can be reduced at concentrations that match their individual potency. PLoS One 6:e21503. 10.1371/journal.pone.0021503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pawlowic MC, Somepalli M, Sateriale A, Herbert GT, Gibson AR, Cuny GD, Hedstrom L, Striepen B. 2019. Genetic ablation of purine salvage in Cryptosporidium parvum reveals nucleotide uptake from the host cell. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 116:21160–21165. 10.1073/pnas.1908239116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Atanasova K, Lee J, Roberts J, Lee K, Ojcius DM, Yilmaz O. 2016. Nucleoside-diphosphate-kinase of P. gingivalis is secreted from epithelial cells in the absence of a leader sequence through a pannexin-1 interactome. Sci Rep 6:37643. 10.1038/srep37643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chavez MA, White AC, Jr.. 2018. Novel treatment strategies and drugs in development for cryptosporidiosis. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 16:655–661. 10.1080/14787210.2018.1500457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Janes J, Young ME, Chen E, Rogers NH, Burgstaller-Muehlbacher S, Hughes LD, Love MS, Hull MV, Kuhen KL, Woods AK, Joseph SB, Petrassi HM, McNamara CW, Tremblay MS, Su AI, Schultz PG, Chatterjee AK. 2018. The ReFRAME library as a comprehensive drug repurposing library and its application to the treatment of cryptosporidiosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 115:10750–10755. 10.1073/pnas.1810137115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Iroh Tam P, Arnold SLM, Barrett LK, Chen CR, Conrad TM, Douglas E, Gordon MA, Hebert D, Henrion M, Hermann D, Hollingsworth B, Houpt E, Jere KC, Lindblad R, Love MS, Makhaza L, McNamara CW, Nedi W, Nyirenda J, Operario DJ, Phulusa J, Quinnan GV, Sawyer LA, Thole H, Toto N, Winter A, Van Voorhis WC. 2021. Clofazimine for treatment of cryptosporidiosis in human immunodeficiency virus infected adults: an experimental medicine, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2a trial. Clin Infect Dis 73:183–191. 10.1093/cid/ciaa421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. 2001. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods 25:402–408. 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vader P, van der Aa LJ, Engbersen JFJ, Storm G, Schiffelers RM. 2010. A method for quantifying cellular uptake of fluorescently labeled siRNA. J Control Release 148:106–109. 10.1016/j.jconrel.2010.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sato T, Clevers H. 2013. Primary mouse small intestinal epithelial cell cultures. Methods Mol Biol 945:319–328. 10.1007/978-1-62703-125-7_19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hadfield SJ, Robinson G, Elwin K, Chalmers RM. 2011. Detection and differentiation of Cryptosporidium spp. in human clinical samples by use of real-time PCR. J Clin Microbiol 49:918–924. 10.1128/JCM.01733-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Tables S1 and S2; Fig. S1 to S3. Download iai.00196-22-s0001.pdf, PDF file, 0.5 MB (466.4KB, pdf)