Abstract

Purpose:

Investigate single nucleotide variants and short tandem repeats in 44 genes related to spinocerebellar ataxia in clinical and pathologically defined cohorts of multiple system atrophy.

Methods:

Exome sequencing was conducted in 28 clinical multiple system atrophy patients to identify single nucleotide variants in spinocerebellar ataxia -related genes. Novel variants were validated in two independent disease cohorts, 86 clinically diagnosed multiple system atrophy patients and 166 pathological multiple system atrophy cases. Expanded repeat alleles in spinocerebellar ataxia genes were evaluated in 36 clinically diagnosed multiple system atrophy patients; CAG/CAA repeats in TATA-Box Binding Protein (TBP, causative of SCA17) were screened in 216 clinical and pathological multiple system atrophy patients and 346 controls.

Results:

No known pathogenic spinocerebellar ataxia single nucleotide variants or pathogenic range expanded repeat alleles of ATXN1, ATXN2, ATXN3, CACNA1A, AXTN7, ATXN8OS, ATXN10, PPP2R2B, and TBP were detected in any clinical multiple system atrophy patients. However, four novel variants were identified in four spinocerebellar ataxia-related genes across three multiple system atrophy patients. Additionally, four multiple system atrophy patients (1.6%) and one control (0.3%) carried an intermediate length 41 TBP CAG/CAA repeat allele (OR=4.11, P=0.21). There was a significant association between occurrence of a repeat length of longer alleles (>38 repeats) and an increased risk of multiple system atrophy (OR=1.64, P=0.03).

Conclusion:

Occurrence of TBP CAG/CAA repeat length of longer alleles (>38 repeats) is significantly associated with increased multiple system atrophy risk. This discovery warrants further investigation and supports a possible genetic overlap of multiple system atrophy with SCA17.

Keywords: multiple system atrophy, genetics, spinocerebellar ataxia

Introduction

Multiple system atrophy (MSA) is a progressive, neurodegenerative movement disorder characterised by α-synuclein aggregated pathology in the oligodendroglia (termed glial cytoplasmic inclusions; GCIs) [1, 2]. MSA has Parkinsonian features similar to the more common synucleinopathies such as Parkinson’s disease (PD) and dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB). However, the incidence of MSA is much lower than PD and DLB with only 3 in 100,000 persons being diagnosed over the age of 50 each year [3, 4]. The average age of onset in MSA is approximately 55 years, and the disease follows a rapid clinical course, progressing from initial symptom onset to death in typically six to ten years [5].

Clinically, MSA predominantly presents with parkinsonism, autonomic failure, pyramidal symptoms, and cerebellar ataxia [6], however MSA is more accurately classified into two clinical subtypes which are defined by specific symptoms - MSA-P by parkinsonism and MSA-C by cerebellar ataxia [6, 7]. MSA-P is commonly misdiagnosed as PD, DLB, and occasionally progressive supranuclear palsy [8, 9]. MSA-C is clinically similar to a group of disorders referred to as spinocerebellar ataxias (SCA) [10–13], whereby both present with limb and truncal ataxia involving gait unsteadiness, limb incoordination, and slurred speech. [14, 15]. These clinical subtypes reflect differences in brain pathology where MSA-P is characterised by predominantly striatonigral degeneration (SND) and MSA-C by predominantly olivopontocerebellar atrophy (OPCA); a third MSA-mixed subtype can be defined at autopsy with a combination of these two pathologies [7]. Like MSA-C, SCA is also determined by cerebellar degeneration [16]. Clinical differentiation of SCA and MSA-C is challenging and results from studies with clinical patients may need to be interpreted with caution.

SCA describes a broad range of hereditary ataxias (SCA1-44), caused by either point mutations or repeat expansions at specific loci [14, 17]. Due to the phenotypic similarities between SCA and MSA, genetic parallels may exist between the two disorders. Notably, a study performed by Kim and colleagues in the South Korean population reported that a relatively high proportion (7.3%) of clinically diagnosed MSA patients tested positive for several SCA gene mutations, with the rate being higher (10.2%) in the MSA-C group [18]. Interestingly, the gene implicated in SCA17, coding for TATA-Box Binding Protein (TBP), was responsible for more than half of the MSA cases positive for SCA mutations. Although, alleles with a repeat length >40 were considered to be pathogenic of SCA17 in this study, which is lower than the generally accepted threshold [19]. Similar findings of SCA mutations in clinical MSA patients have been reported in case studies [10–12, 20] and clinical cohorts [21], with many connections involving SCA17. Despite consistent findings, most studies have concluded that the results are due to misdiagnosis of SCA patients as MSA rather than a consequence of a direct genetic relationship between the diseases.

SCA mutations have been detected in clinical MSA, indicating that a comprehensive investigation of the association between SCA mutations and risk of MSA is warranted. Thus, we hypothesized that some clinical cases of MSA are due to pathogenic mutations in SCA-related genes and that by comprehensive screening we can identify carriers, increase diagnostic accuracy and determine the impact on MSA risk.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

A total of 86 clinically diagnosed MSA patients and 166 pathological MSA brains were included in this study. Clinical cases were recruited at Mayo Clinic Rochester (MCR) (N=36) and Mayo Clinic Jacksonville (MCJ) (N=50) (Table 1). All clinical patients were independently diagnosed by Movement Disorder experts at each respective site using Gilman et al. (2008) criteria and defined as probable (n= 78) and possible (n=8) MSA [6]. Autopsied brain tissues were received at MCJ between 1998 and 2015 and were pathologically diagnosed and characterised by a single neuropathologist (DWD). Immunohistochemistry for α-synuclein was performed on sections of the basal forebrain, striatum, midbrain, pons, medulla, and cerebellum, using NACP, 1:3000 rabbit polyclonal antibodies, to establish neuropathological diagnosis’ of MSA [2, 22]. Pathological subtype of MSA was assessed on the severity of neurodegeneration and gliosis of each vulnerable region, whereby MSA-P had more severe pathology in the striatonigral region, MSA-C had more severe pathology in the olivopontocerebellar region, and MSA-mixed had equally severe pathology in both regions [22]. Control subjects were free from neurological disease and were recruited at both MCR (N=158) and MCJ (N=188). Written consent and IRB approval was obtained for all patients included in this study. All subjects were non-Hispanic, Caucasian, and unrelated.

Table 1.

Cohort demographics.

| Clinical MSA Cohorts | Pathological MSA | Control Cohorts | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | MCR (N=36) | MCJ (N=50) | MCJ (N=166) | MCR (N=158) | MCJ (N=188) |

| Age at Study | 60.1 (45, 82) | 69.7 (49, 88) | 67.1 (47, 91) | 59.9 (43, 76) | 60.6 (18, 88) |

| Sex (male) | 22 (61.1%) | 27 (54.0%) | 96 (57.8%) | 101 (63.9%) | 83 (44.1%) |

| Probable MSA diagnosis | 36 (100%) | 42 (84.0%) | |||

| MSA subtype | |||||

| MSA-C | 18 (50.0%) | -- | 27 (16.2%) | -- | -- |

| MSA-P | 17 (47.2%) | -- | 68 (41.0%) | -- | -- |

| MSA-mixed | -- | 70 (42.2% | -- | -- | |

| MSA-Unclassified | 1 (2.8%) | 50 (100%) | 1 (0.6%) | -- | -- |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||||

| Caucasian | 28 (77.8%) | 50 (100.0%) | 165 (99.4%) | 157 (99.4%) | 188 (100%) |

| Unknown | 8 (22.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.6%) | 1 (0.6%) | 0 (0.0%) |

The sample mean (minimum, maximum) is given for age.

Clinical patients were not given a MSA subtype diagnosis. One pathological MSA patient was considered “MSA-unclassified” as the pons was unavailable for histological assessment.

MSA-C: Multiple system atrophy-cerebellar ataxia; MSA-P: Multiple system atrophy-parkinsonism; MCJ; MCR: Mayo Clinic Rochester (MN, USA); Mayo Clinic Jacksonville (FL, USA).

Sample Preparation

Genomic DNA was extracted from the buffy coat using a Qiagen DNeasy kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) for clinical MCR MSA samples and was extracted from whole blood using Autogen FlexSTAR automation (Autogen, Holiston, MA, USA) for MCJ MSA cases and all controls. Genomic DNA was extracted from the cerebellum region of the brain for all pathological MSA cases using the Autogen 245T (Autogen, Holiston, MA, USA). All extraction methods were conducted following manufacturer’s recommended protocols.

Genetic Analysis

Whole exome sequencing was performed on 28 clinical MCR MSA patients (Table 1) using the Agilent SureSelect Human All Exon V5+UTRs capture kit, with sequencing performed on an Illumina HiSeq2500 by the Mayo Clinic Genomics Core. Exome data was processed using the Mayo Genome GPS v4.0 pipeline. Functional annotations of variants were performed using ANNOVAR (version 2016Feb01). Genotype calls with GQ < 10 and/or depth (DP) < 10 were set to missing, and variants with ED > 4 were removed from all subsequent analyses. For all analyses, only variants that passed Variant Quality Score Recalibration (VQSR) and with a call rate > 95% were considered, unless otherwise specified. We extracted the identified variants for the SCA genes (Supplementary Table 1) from the generated VCF using Golden Helix (SNP & Variation Suite v8.8.3). Novel variants at the time of study were validated using bidirectional Sanger Sequencing (primer sequences are available upon request). All PCR products were purified using Agencourt AMPure XP and Agencourt CleanSeq chemistry (Beckman Coulter™, CA, USA) on a Beckman Coulter Biomek FXP liquid handler (Beckman Coulter™, CA, USA) and DNA sequencing was performed on an Applied Biosystems™ 3730xl DNA Analyzer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA). Sequences were analyzed using SeqScape™ Software v3.0 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA).

To further investigate the significance of the SNVs, the remaining clinical MCR MSA patients (N=8) and MCJ MSA patients (N=50), as well as the 166 pathological MSA cases and all 346 controls were genotyped using Agena Bioscience MassArray iPlex® Gold chemistry technology [23]. Primers were designed using MassARRAY Assay Design v.4.0.0.2 (Agena Bioscience™, San Diego, USA). Genotype calling was performed using MassARRAY Typer 4.0 v.4.0.25.73 (Agena Bioscience, San Diego, USA). No SNPs deviated from Hardy Weinberg equilibrium.

A total of 36 MCR MSA patients (Table 1) including those that had underwent whole exome sequence analysis, were investigated for pathogenic expanded repeat insertions in genes (ATXN1, ATXN2, ATXN3, CACNA1A, AXTN7, ATXN8OS, ATXN10, PPP2R2B, NOP56, and TBP) known to cause SCA (1-3, 6-8, 10, 12 and 17) (Supplementary Table 1). Microsatellite primers were designed around each region of interest (ROI) for each gene, with the forward primer being labelled with a 6-carboxyfluorescin (FAM) fluorophore. Each ROI was amplified using standard PCR and measured on an Applied Biosystems™ 3730xl DNA Analyzer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA) using GeneScan™ 400HD ROX™ Size Standard (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA). Allelic sizes were identified using GeneMapper™ software (version 5) (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA). The CAG/CAA repeats in TBP were additionally investigated in the MCJ clinical MSA cohort (N=50), all pathological MSA cases (N=166), and both control groups (N=346). Normal alleles are generally considered between 25–42 repeats, with ≥43 repeats considered to be pathogenic of SCA17 [19]; ≥43 repeats were considered pathogenic in this study.

Statistical Analysis

Association of TBP CAG/CAA repeat length with risk of MSA were evaluated using logistic regression models, where TBP CAG/CAA repeat length was examined in the four following ways in logistic regression analysis: (1) presence of a repeat length of 41, (2) presence of a repeat length on the longer allele greater than the 75th percentile (i.e. >38), (3) repeat length of the longer allele as a continuous variable, and (4) total repeat length on both alleles as a continuous variable. Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated. P-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. All statistical tests were two-sided and were performed using R (version 3.6.1) (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

No pathogenic SCA gene variants published in the literature were observed in the 28 clinical MSA patients who underwent exome sequencing; however, four novel variants in the SCA-associated genes, SPTBN2, KCNC3, NOP56, and ELOVL5 were observed (Table 2). The four variants were detected in three clinical MCR MSA cases, of which two were diagnosed with MSA-C and one with MSA-P. Pathogenic expanded repeat alleles/insertions in different genes (ATXN1, ATXN2, ATXN3, CACNA1A, AXTN7, ATXN8OS, ATXN10, PPP2R2B, NOP56, and TBP) associated with SCA were not present in any patients. However, 41 CAG/CAA repeats in TBP were observed in two individuals (both MSA-P subtype); above the pathogenic threshold as defined in the Kim et al. study [18]. Further screening in an additional MSA patients (N=216) and available controls (N=346) identified two additional pathological MSA cases (both MSA-mixed subtype) carrying the 41 CAG/CAA repeat length in TBP.

Table 2.

Summary of novel SNVs identified through Exome sequencing and associated with spinocerebellar ataxia.

| Gene | SCA | Nucleotide Change | Amino Acid Change | SIFT/Polyphen | CADD Score | MSA Subtype |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SPTBN2 | 5 | c.7024 C/T | V2342M | Tolerated/Benign | 15.88 | MSA-P1 |

| KCNC3 | 13 | c.680 T/A | E227V | Damaging/Benign | 22.1 | MSA-C |

| NOP56 | 36 | c.890 C/T | S297L | Damaging/Possibly Damaging | 25.6 | MSA-P1 |

| ELOVL5 | 38 | c.447 T/C | I149M | Damaging/Probably Damaging | 15.15 | MSA-C |

28 clinically diagnosed MSA patients (MCR cohort) were exome sequenced and novel variants associated with SCA were further Sanger sequenced for validation. Four novel SNVs were confirmed across three different patients, two of which had MSA-C.

The same patient tested positive for both mutations.

MSA-C: Multiple system atrophy-cerebellar ataxia; MSA-P: Multiple system atrophy-parkinsonism; SCA: spinocerebellar ataxia.

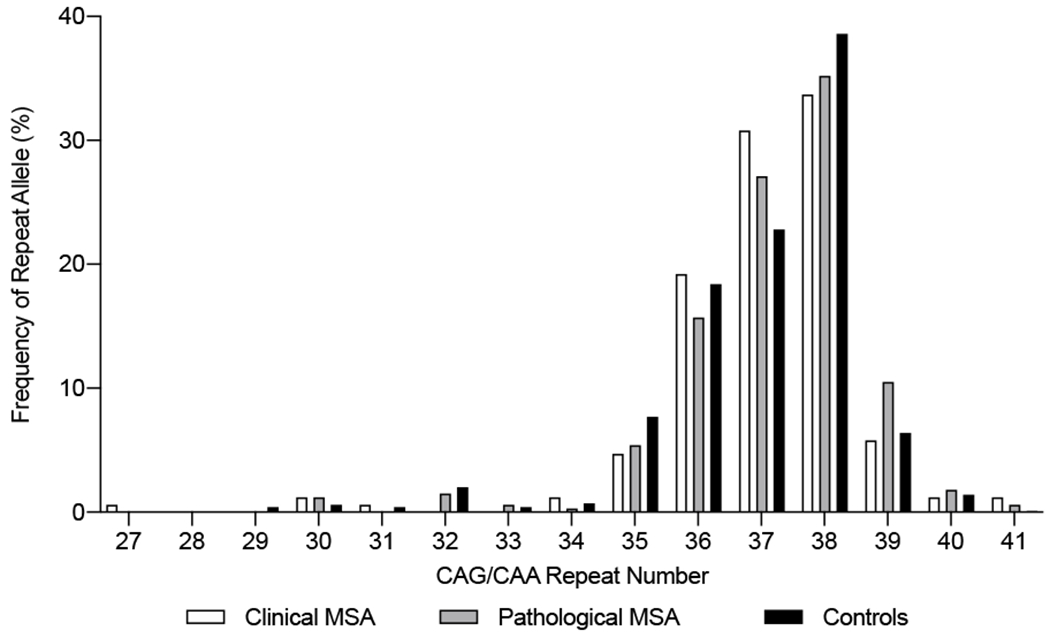

In total, four MSA patients (1.6%) and one control (0.3%) carried 41 CAG repeats in TBP (Table 3, Figure 1); although this difference did not reach statistical significance (OR=4.11, P=0.21, Table 4). However, a statistically significant association was observed between the presence of a repeat length on the longer allele >38 (i.e. >75th percentile) and increased risk of MSA (OR=1.64, P=0.030). Additionally, a significant association was observed when assessing repeat length on the longer allele as a continuous variable for an elevated MSA risk (OR [per each 1-repeat increase] =1.21, P=0.034), and a trend for such an association when assessing total repeat length (OR [per each 5-repeat increase] =1.42, P=0.066, Table 4).

Table 3.

Allele frequencies of TBP CAG/CAA repeats in MSA cases and controls.

| Allele Frequency (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Repeat Number | MCR Clinical (N=36) | MCJ Clinical (N=50) | Pathological (N=166) | MCR Controls (N=158) | MCJ Controls (N=188) |

| 27 | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| 28 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| 29 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.3) | 2 (0.5) |

| 30 | 2 (2.8) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (1.2) | 2 (0.6) | 2 (0.5) |

| 31 | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.3) | 2 (0.5) |

| 32 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (1.5) | 7 (2.2) | 7 (1.9) |

| 33 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.6) | 1 (0.3) | 2 (0.5) |

| 34 | 0 (0.0) | 2 (2.0) | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) | 4 (1.1) |

| 35 | 1 (1.4) | 7 (7.0) | 18 (5.4) | 28 (8.9) | 25 (6.6) |

| 36 | 15 (20.8) | 18 (18.0) | 52 (15.7) | 54 (17.1) | 73 (19.4) |

| 37 | 21 (29.2) | 32 (32.0) | 90 (27.1) | 73 (23.1) | 85 (22.6) |

| 38 | 28 (38.9) | 30 (30.0) | 117 (35.2) | 121 (38.3) | 146 (38.8) |

| 39 | 2 (2.8) | 8 (8.0) | 35 (10.5) | 23 (7.3) | 21 (5.6) |

| 40 | 1 (1.4) | 1 (1.0) | 6 (1.8) | 3 (0.9) | 7 (1.9) |

| 41 | 2 (2.8) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.6) | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) |

The frequency (percentage) of TBP CAG/CAA repeat length alleles from 27 to 41 is reported for each MSA cohort and control group.

MSA: Multiple system atrophy; MCR: Mayo Clinic Rochester (MN, USA); MCJ: Mayo Clinic Jacksonville (FL, USA).

Figure 1 -.

Frequencies of TBP CAG/CAA repeat alleles in the clinically and pathologically defined MSA cases and controls. The clinical MSA group comprised clinically diagnosed MCR and MCJ MSA cohorts. The control group comprised the MCR and MCJ controls cohorts. MSA: Multiple system atrophy; Mayo Clinic Rochester (MN, USA); MCJ: Mayo Clinic Jacksonville (FL, USA).

Table 4.

Association between TBP CAG/CAA repeat lengths and risk of MSA.

| No. (%) or mean (minimum, maximum) | Association with MSA | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TBP CAG/CAA repeat length variable | MSA cases (N=252) | Controls (N=346) | OR (95% CI) | P-value |

| Presence of a repeat length of 41 | 4 (1.6%) | 1 (0.3%) | 4.11 (0.45, 37.86) | 0.21 |

| Presence of a repeat length >75th percentile (i.e. >38) | 54 (21.4%) | 50 (14.5%) | 1.64 (1.05, 2.57) | 0.03 |

| Repeat length on longer allele as a continuous variable | 37.9 (35, 41) | 37.7 (32, 41) | 1.21 (1.01, 1.44)1 | 0.034 |

| Total repeat length on both alleles as a continuous variable | 74.3 (63, 79) | 74.0 (62, 79) | 1.42 (0.98, 2.07)2 | 0.066 |

ORs, 95% CIs, and p-values result from logistic regression models that were adjusted for age and sex.

OR corresponds to a one-repeat increase in repeat length on the longer allele.

OR corresponds to a five-repeat increase in total repeat length.

OR=odds ratio; CI=confidence interval.

Discussion

Several studies have investigated the association of known PD risk-variants with risk of MSA [24–28]; however there has been limited investigation into the shared genetic risk factors between SCA and MSA despite clinical and pathological overlap. Herein, we found no known pathogenic SCA mutations in 28 clinical MSA patients from exome sequencing. Furthermore, we investigated the presence of nine expanded repeats in ATXN1, ATXN2, ATXN3, CACNA1A, AXTN7, ATXN8OS, ATXN10, PPP2R2B, NOP56, and TBP - which are known pathogenic genes in SCA [14, 17, 29]. No clinical MSA patients (N=36) carried an expanded repeat in genes causative of SCA. These findings suggest that at present the utility of clinical testing of SCA genes in patients with sporadic MSA is limited.

Interestingly, an overlap between the number of CAG/CAA repeats in TBP in the pathogenic range (≥43 repeats) and the normal range (25-42 repeats) has been reported in the literature [19, 30]. Albeit rare, one study reported controls with 44 CAG/CAA repeats in TBP [31] whilst other studies reported symptomatic patients with 41 repeats [32, 33]. In our study, four MSA patients (1.6%) and one control (0.3%) carried a CAG/CAA repeat length of 41 in TBP. Notably both clinical MSA patients presented with the parkinsonian subtype and both autopsy cases showed mixed pathology on characterization. Notably in the previous study in the Japanese population the carriers of intermediate repeats presented with MSA-C, although this may be due to differences in race or other disease modifiers [18]. Thus the small number of carriers in our study precludes robust analysis but it is hoped that with larger series screening enough carriers may be identified to assess the role of the intermediate repeat lengths as phenotypic modifiers of disease.

Acknowledging the low statistical power in this study, we decided to explore the associations of the TBP CAG/CAA repeat length with disease risk from different statistical angles. We found a statistically significant association between the CAG/CAA repeat length on the longer allele >38 repeats (i.e. >75th percentile) and increased risk of MSA (OR=1.64). Moreover, a significant association was observed between the CAG/CAA repeat length on the longer allele (as a continuous variable) and increased MSA risk (OR=1.21). These data suggest that the longer CAG/CAA repeat alleles in TBP may confer elevated risk with MSA, and possibly cerebellar degeneration. It should be noted that no correction for multiple comparisons was made for the four association tests performed due to the exploratory nature of these analyses. Although the fact that there is some degree of correlation between these four statistical tests attenuates this issue somewhat, the statistically significant findings that were observed would not have survived such a correction. Therefore, it is crucial to highlight that validation of these findings will be important.

TBP encodes the general transcription factor, TATA binding protein (TBP). TBP is fundamental for the transcription of eukaryotic polymerases, including polymerase II which synthesises mRNA [34], therefore dysfunction of TBP can induce transcriptional dysregulation. Consequently, homozygous knockouts of TBP are embryonically lethal, highlighting its biological importance [35]. However, it has been demonstrated in mouse models of SCA17 that TBP with polyglutamine expansion does not impede global gene expression, and in fact only hundreds of genes are downregulated [36]. It is currently thought that polyglutamine expansions in TBP may affect the functions of other transcription factors, such as Sp1 and TFIIB, which then effects downstream transcription of genes [36, 37]. It has also been demonstrated that different numbers of polyglutamine expansions in TBP have differing effects on protein expression [36], whereby >38 (above the population average of 37) TBP polyglutamine repeats may affect transcription factors differently to <38 or >42 repeats, and could consequently lead to variations in transcription of genes which may be relevant to MSA pathogenesis.

The concept that SCA mutations may increase susceptibility to MSA is not incongruous and other reports of intermediate range expansions in SCA genes being associated with increased risk of developing neurological conditions has been reported. For example, a recent study reported that intermediate range of polyglutamine repeats in TBP (above the median) and ATXN7 (>10), which is causative for SCA7, have been associated with a heightened risk of lifetime depression [38]. Moreover, SCA gene repeat numbers have been reported to influence risk of neurodegenerative diseases [39, 40]. For instance, intermediate length polyglutamine repeats in ATXN2, the gene implicated in SCA2, have been associated with a greater risk of developing amyotrophic lateral sclerosis [40]. Furthermore, SCA gene repeats can modify neurodegenerative disease phenotypes. For example, CAG repeat number in ATXN1 modifies memory performance in Alzheimer’s disease patients [39]. These studies further support the results reported in this study by demonstrating that CAG repeats in SCA-related genes may be modifying neurodegenerative phenotypes.

Several limitations of our study should be acknowledged. Though our MSA series (in particular the neuropathological cohort) is large considering the prevalence of MSA, the cohort is small for a genetic association study, therefore power to detect statistically significant differences in a case-control association analyses is limited. Correspondingly, the possibility of a type II error (i.e. a false-negative finding) is important to consider, and we cannot conclude that no true difference exists simply due to the occurrence of a non-significant p-value. Furthermore, only a subset of clinical MSA patients underwent exome sequencing for known pathogenic SCA gene mutations, and were further screened for repeat expansions in ATXN1, ATXN2, ATXN3, CACNA1A, AXTN7, ATXN8OS, ATXN10, PPP2R2B, NOP56, and TBP. It should also be noted we are not excluding the possibility that other SCA repeats influence MSA susceptibility or phenotypic presentation, as these were not examined in the larger series as part of the current study.

In conclusion, our study demonstrates that the presence of mutations which are causative of SCA are not commonly present in MSA patients. However, our data suggest that long normal range polyglutamine repeats (>38) in TBP may confer risk to MSA. Larger case-control or meta-analytic studies are warranted to further explore the role of TBP polyglutamine repeats in MSA risk, as well as discern any influence of long normal range repeats on factors such as age of onset, disease duration, and clinical phenotypes.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Table 1

aGenes likely responsible for SCA but require further confirmation. 1: Gene was screened for known pathogenic point mutations and novel point mutations via exome sequencing (N=28). 2: Gene was screened for repeats by duplication analysis; however, duplication analysis was not possible for BEAN and DAB1 due to the absence of a positive control.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all those who have contributed to our research, particularly the patients and families who donated brain and blood samples for this work. We are grateful to all patients, family members, and caregivers who agreed to brain donation. Without their donation these studies would not have been possible. We also acknowledge expert technical assistance of Virginia Phillips for histology and Monica Castanedes-Casey for immunohistochemistry and Audrey Strongosky for her assistance in blood sample collection and brain donation arrangements. Mayo Clinic is an American Parkinson Disease Association (APDA) Mayo Clinic Information and Referral Center, an APDA Center for Advanced Research, and the Mayo Clinic Lewy Body Dementia Association (LBDA) Research Center of Excellence and a LBD Center WithOut Walls (U54 NS110435). Samples included in this study were clinical controls or brain donors to the Mayo Clinic Brain Bank in Jacksonville, which is supported by CurePSP and the Tau Consortium. SK is supported by a Jaye F. and Betty F. Dyer Foundation Fellowship in Progressive supranuclear palsy research and CorticoBasal Degeneration Solutions Research Grant. ZKW is partially supported by the Mayo Clinic Center for Regenerative Medicine, the gifts from The Sol Goldman Charitable Trust, and the Donald G. and Jodi P. Heeringa Family, the Haworth Family Professorship in Neurodegenerative Diseases fund, and The Albertson Parkinson’s Research Foundation. The funding organizations and sponsors had no role in any of the following: design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Funding:

Mayo Clinic is an American Parkinson Disease Association (APDA) Mayo Clinic Information and Referral Center, an APDA Center for Advanced Research, and the Mayo Clinic Lewy Body Dementia Association (LBDA) Research Center of Excellence and a LBD Center WithOut Walls (U54 NS110435). SK is supported by a Jaye F. and Betty F. Dyer Foundation Fellowship in Progressive supranuclear palsy research and CorticoBasal Degeneration Solutions Research Grant.

Conflicts of interest/Competing interests

Anna I. Wernick, Ronald L. Walton, Alexandra I. Soto-Beasley, Shunsuke Koga, and Rebecca R. Valentino report no disclosures.

Michael G. Heckman is a Statistical Editor of Parkinsonism & Related Disorders, and is on the editorial board of Molecular Neurodegeneration

Lukasz M. Milanowski is supported by the Polish National Agency for Academic Exchange Iwanowska’s Programme PPN/IWA/2018/1/00006/U/00001/01

Dorota Hoffman-Zacharska report no disclosures.

Dariusz Koziorowski report no disclosures.

Anhar Hassan is on the editorial board of Parkinsonism and Related Disorders, and receives research support from Intrabio.

Ryan J. Uitti is an Associate Editor of Neurology

William P. Cheshire is an Associate Editor of Clinical Autonomic Research and is on the editorial boards of Autonomic Neuroscience and Parkinsonism and Related Disorders.

Wolfgang Singer received research support from NIH (R01NS092625, U54NS065736), FDA (R01FD004789), Sturm Foundation, and Mayo Funds. He is associate editor of Clinical Autonomic Research and serves on the editorial board of Autonomic Neuroscience. He has advisory board and consulting agreements with Lundbeck, Catalyst, and Astellas.

Zbigniew K. Wszolek receives research support from P50-NS072187, NIH/NIA (primary) and NIH/NINDS (secondary) 1U01AG045390-01A1, Mayo Clinic Center for Regenerative Medicine, the gift from Carl Edward Bolch, Jr., and Susan Bass Bolch, The Sol Goldman Charitable Trust, and Donald G. and Jodi P. Heeringa, the Haworth Family Professorship in Neurodegenerative Diseases fund, and by the Albertson Parkinson’s Research Foundation. He serves as Co-Editor-in-Chief of Neurologia i Neurochirurgia Polska and is on the editorial boards of European Journal of Clinical and Experimental Medicine, Clinical and Experimental Medical Letters, and Wiadomosci Lekarskie; holds and has contractual rights for receipt of future royalty payments from patents for “A Novel Polynucleotide Involved in Heritable Parkinson’s Disease”; and received royalties from publishing Parkinsonism and Related Disorders (Elsevier, 2016, 2017) and the European Journal of Neurology (Wiley Blackwell, 2016, 2017). ZKW serves as PI or Co-PI on Abbvie, Inc. (M15-562 and M15-563), Biogen, Inc. (228PD201) grant, and Biohaven Pharmaceuticals, Inc. (BHV4157-206 and BHV3241-301). He serves as PI of the Mayo Clinic American Parkinson Disease Association (APDA) Information and Referral Center, and as Co-PI of the Mayo Clinic APDA Center for Advanced Research.

Dennis W. Dickson (DWD) receives support from P50-AG016574, P50-NS072187, P01-AG003949, and CurePSP: Foundation for PSP | CBD and Related Disorders. DWD is an editorial board member of Acta Neuropathologica, Annals of Neurology, Brain, Brain Pathology, and Neuropathology and is Editor in Chief of American Journal of Neurodegenerative Disease and International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Pathology.

Phillip A. Low receives support from Supported by NIH (P01NS44233, U54NS065736, R01 FD004789, R01 NS092625, Cure MSA Foundation, Sturm and Mayo Funds.

Owen A. Ross (OAR) receives support from R01-NS078086, P50-NS072187, and U54 NS100693, The Little Family Foundation, and the Michael J. Fox Foundation. OAR is an editorial board member of American Journal of Neurodegenerative Disease and Molecular Neurodegeneration.

Footnotes

Code availability: not applicable

Ethics approval; Consent to participate; Consent for publication: Written consent from each subject or next-of-kin was collected for all patients included in this study and IRB approval was obtained from the Mayo Clinic institutional review board for ethical conduct of research.

Availability of data and material:

All relevant data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article (and its supplementary information files). Full datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- [1].Ahmed Z, Asi YT, Sailer A, Lees AJ, Houlden H, Revesz T, Holton JL (2012) The neuropathology, pathophysiology and genetics of multiple system atrophy. Neuropathology and applied neurobiology 38: 4–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Trojanowski JQ, Revesz T (2007) M.S.A. Neuropathology Working Group on, Proposed neuropathological criteria for the post mortem diagnosis of multiple system atrophy. Neuropathology and applied neurobiology 33:615–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Bower JH, Maraganore DM, McDonnell SK, Rocca WA (1997) Incidence of progressive supranuclear palsy and multiple system atrophy in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1976 to 1990. Neurology 49:1284–1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Bjornsdottir A, Gudmundsson G, Blondal H, Olafsson E (2013) Incidence and prevalence of multiple system atrophy: a nationwide study in Iceland. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 84:136–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Fanciulli A, Wenning GK (2015) Multiple-system atrophy. N Engl J Med 372 249–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Gilman S, Wenning GK, Low PA, Brooks DJ, Mathias CJ, Trojanowski JQ, Wood NW, Colosimo C, Durr A, Fowler CJ, Kaufmann H, Klockgether T, Lees A, Poewe W, Quinn N, Revesz T, Robertson D, Sandroni P, Seppi K, Vidailhet M (2008) Second consensus statement on the diagnosis of multiple system atrophy. Neurology, 71:670–676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Koga S, Dickson DW (2018) Recent advances in neuropathology, biomarkers and therapeutic approach of multiple system atrophy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry, 89:175–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Koga S, Aoki N, Uitti RJ, van Gerpen JA, Cheshire WP, Josephs KA, Wszolek ZK, Langston JW, Dickson DW (2015) When DLB, PD, and PSP masquerade as MSA: an autopsy study of 134 patients. Neurology 85:404–412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Xie T, Kang UJ, Kuo SH, Poulopoulos M, Greene P, Fahn S (2015) Comparison of clinical features in pathologically confirmed PSP and MSA patients followed at a tertiary center. NPJ Parkinsons Dis 1:15007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Doherty KM, De Pablo-Fernandez E, Houlden H, Polke JM, Lees AJ, Warner TT, Holton JL (2016) MSA-C or SCA 17? A clinicopathological case update. Mov Disord 31:1582–1584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Doherty KM, Warner TT, Lees AJ (2014) Late onset ataxia: MSA-C or SCA 17? A gene penetrance dilemma. Mov Disord 29:36–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Smetcoren C, Weckhuysen D (2016) SCA 8 mimicking MSA-C. Acta Neurol Belg 116:221–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Lin IS, Wu RM, Lee-Chen GJ, Shan DE, Gwinn-Hardy K (2007) The SCA17 phenotype can include features of MSA-C, PSP and cognitive impairment. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 13:246–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Klockgether T, Mariotti C, Paulson HL (2019) Spinocerebellar ataxia. Nat Rev Dis Primers 5:24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Tai G, Corben LA, Yiu EM, Milne SC and Delatycki MB (2018). Progress in the treatment of Friedreich ataxia. Neurol Neurochir Pol 52: 129–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Seidel K, Siswanto S, Brunt ER, den Dunnen W, Korf HW, U. (2012) Rub, Brain pathology of spinocerebellar ataxias. Acta Neuropathol 124:1–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Bird TD, Hereditary Ataxia Overview, in: Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Pagon RA, Wallace SE, Bean LJH, Stephens K, Amemiya A (Eds.) GeneReviews((R)), Seattle (WA), 1993. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Kim HJ, Jeon BS, Shin J, Lee WW, Park H, Jung YJ, Ehm G (2014) Should genetic testing for SCAs be included in the diagnostic workup for MSA? Neurology 83:1733–1738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Nakamura K, Jeong SY, Uchihara T, Anno M, Nagashima K, Nagashima T, Ikeda S, Tsuji S, Kanazawa I (2001) SCA17, a novel autosomal dominant cerebellar ataxia caused by an expanded polyglutamine in TATA-binding protein. Hum Mol Genet 10:1441–1448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Munhoz RP, Teive HA, Raskin S, Werneck LC (2009) CTA/CTG expansions at the SCA 8 locus in multiple system atrophy. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 111:208–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Mongelli A, Sarro L, Rizzo E, Nanetti L, Meucci N, Pezzoli G, Goldwurm S, Taroni F, Mariotti C, Gellera C (2018) Multiple system atrophy and CAG repeat length: A genetic screening of polyglutamine disease genes in Italian patients. Neurosci Lett 678:37–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Ozawa T, Paviour D, Quinn NP, Josephs KA, Sangha H, Kilford L, Healy DG, Wood NW, Lees AJ, Holton JL, Revesz T (2004) The spectrum of pathological involvement of the striatonigral and olivopontocerebellar systems in multiple system atrophy: clinicopathological correlations. Brain 127:2657–2671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Gabriel S, Ziaugra L, Tabbaa D (2009) SNP genotyping using the Sequenom MassARRAY iPLEX platform, Curr Protoc Hum Genet, Chapter 2 Unit 2 12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Ai SX, Xu Q, Hu YC, Song CY, Guo JF, Shen L, Wang CR, Yu RL, Yan XX, Tang BS (2014) Hypomethylation of SNCA in blood of patients with sporadic Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol Sci 337:123–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Al-Chalabi A, Durr A, Wood NW, Parkinson MH, Camuzat A, Hulot JS, Morrison KE, Renton A, Sussmuth SD, Landwehrmeyer BG, Ludolph A, Agid Y, Brice A, Leigh PN, Bensimon G, Group NGS (2009) Genetic variants of the alpha-synuclein gene SNCA are associated with multiple system atrophy. PLoS One 4:e7114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Guo XY, Chen YP, Song W, Zhao B, Cao B, Wei QQ, Ou RW, Yang Y, Yuan LX, Shang HF. (2014) SNCA variants rs2736990 and rs356220 as risk factors for Parkinson’s disease but not for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and multiple system atrophy in a Chinese population. Neurobiol Aging 35:2882 e2881–2882 e2886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Scholz SW, Houlden H, Schulte C, Sharma M, Li A, Berg D, Melchers A, Paudel R, Gibbs JR, Simon-Sanchez J, Paisan-Ruiz C, Bras J, Ding J, Chen H, Traynor BJ, Arepalli S, Zonozi RR, Revesz T, Holton J, Wood N, Lees A, Oertel W, Wullner U, Goldwurm S, Pellecchia MT, Illig T, Riess O, Fernandez HH, Rodriguez RL, Okun MS, Poewe W, Wenning GK, Hardy JA, Singleton AB, Del Sorbo F, Schneider S, Bhatia KP, Gasser T (2009) SNCA variants are associated with increased risk for multiple system atrophy. Ann Neurol 65:610–614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Sklerov M, Kang UJ, Liong C, Clark L, Marder K, Pauciulo M, Nichols WC, Chung WK, Honig LS, Cortes E, Vonsattel JP, Alcalay RN (2017) Frequency of GBA variants in autopsy-proven multiple system atrophy. Mov Disord Clin Pract 4:574–581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Whaley NR, Fujioka S, Wszolek ZK (2011) Autosomal dominant cerebellar ataxia type I: a review of the phenotypic and genotypic characteristics. Orphanet J Rare Dis 6:33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Koide R, Kobayashi S, Shimohata T, Ikeuchi T, Maruyama M, Saito M, Yamada M, Takahashi H, Tsuji S (1999) A neurological disease caused by an expanded CAG trinucleotide repeat in the TATA-binding protein gene: a new polyglutamine disease? Hum Mol Genet 8:2047–2053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Shin JH, Park H, Ehm GH, Lee WW, Yun JY, Kim YE, Lee JY, Kim HJ, Kim JM, Jeon BS, Park SS (2015) The Pathogenic Role of Low Range Repeats in SCA17. PLoS One 10:e0135275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Nanda A, Jackson SA, Schwankhaus JD, Metzer WS (2007) Case of spinocerebellar ataxia type 17 (SCA17) associated with only 41 repeats of the TATA-binding protein (TBP) gene. Mov Disord 22:436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Origone P, Gotta F, Lamp M, Trevisan L, Geroldi A, Massucco D, Grazzini M, Massa F, Ticconi F, Bauckneht M, Marchese R, Abbruzzese G, Bellone E, Mandich P (2018) Spinocerebellar ataxia 17: full phenotype in a 41 CAG/CAA repeats carrier. Cerebellum Ataxias 5:7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Gill G, Tjian R (1992) Eukaryotic coactivators associated with the TATA box binding protein. Curr Opin Genet Dev 2:236–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Martianov I, Viville S, Davidson I (2002) RNA polymerase II transcription in murine cells lacking the TATA binding protein. Science, 298:1036–1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Friedman MJ, Shah AG, Fang ZH, Ward EG, Warren ST, Li S, Li XJ (2007) Polyglutamine domain modulates the TBP-TFIIB interaction: implications for its normal function and neurodegeneration. Nat Neurosci 10:1519–1528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Yang S, Li XJ, Li S (2016) Molecular mechanisms underlying Spinocerebellar Ataxia 17 (SCA17) pathogenesis. Rare Dis 4:e1223580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Gardiner SL, van Belzen MJ, Boogaard MW, van Roon-Mom WMC, Rozing MP, van Hemert AM, Smit JH, Beekman ATF, van Grootheest G, Schoevers RA, Oude Voshaar RC, Comijs HC, Penninx B, van der Mast RC, Roos RAC, Aziz NA (2017) Large normal-range TBP and ATXN7 CAG repeat lengths are associated with increased lifetime risk of depression. Transl Psychiatry 7:e1143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Gardiner SL, Harder AVE, Campman YJM, Trompet S, Gussekloo J, van Belzen MJ, Boogaard MW, Roos RAC, Jansen IE, Pijnenburg YAL, Scheltens P, van der Flier WM, Aziz NA (2019) Repeat length variations in ATXN1 and AR modify disease expression in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging 73:230 e239–230 e217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Elden AC, Kim HJ, Hart MP, Chen-Plotkin AS, Johnson BS, Fang X, Armakola M, Geser F, Greene R, Lu MM, Padmanabhan A, Clay-Falcone D, McCluskey L, Elman L, Juhr D, Gruber PJ, Rub U, Auburger G, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VM, Van Deerlin VM, Bonini NM, Gitler AD (2010) Ataxin-2 intermediate-length polyglutamine expansions are associated with increased risk for ALS. Nature 466:1069–1075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Table 1

aGenes likely responsible for SCA but require further confirmation. 1: Gene was screened for known pathogenic point mutations and novel point mutations via exome sequencing (N=28). 2: Gene was screened for repeats by duplication analysis; however, duplication analysis was not possible for BEAN and DAB1 due to the absence of a positive control.

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article (and its supplementary information files). Full datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.