Abstract

To further refine the measurement of coparenting across family dynamics, this article presents data from 2 separately collected samples, the first consisting of 252 parents and the second consisting of 329 parents, analyzed as a pilot study of the Short-Form of the Coparenting Across Family Structures Scale (CoPAFS 27-Items). The purpose of the revised shortened tool is to further the design of an efficient and psychometrically strong tool to aid research and clinical practice with coparents. Our intent was to differentiate coparenting in intact, separated/divorced, and families where the parents were never romantically involved, between mothers and fathers, and between high- and low-income levels. This pilot test assessed psychometric properties (stability, reliability, and internal consistency) of the CoPAFS to determine whether the measure could be useful for evaluating the core dimensions of coparenting. Analyses reduced the 56-item CoPAFS scale developed from existing scales and literature to a 5-component scale of 27 items, including Respect, Trust, Valuing the other parent, Communication and Hostility. Implications for interventions and future research are briefly discussed.

Keywords: Coparenting, Family Structure, Factor Analysis, Measurement, Psychometrics

Highlights

Coparenting refers to the attitudes, beliefs and behaviors towards the child’s other parent.

Coparenting is practiced and should be assessed across all family dynamics and arrangements.

Coparenting includes five domains of respect, trust, communication, valuing the other parent and hostility.

Although there is no single, uncontested theory of coparenting (Mollà Cusí et al., 2020), modern coparenting theory, in all its variations, is premised on the notion that children are reared within a family relationship system comprised of multiple primary caregivers (Mollà Cusí et al., 2020; McHale & Sirotkin, 2019; Pruett & Pruett, 2009; Saini et al., 2019). Coparenting is defined as two or more adults engaging in the shared activities and responsibilities of raising a child (McHale & Lindahl, 2011).

Within family systems theory, the coparenting relationship constitutes a pivotal subsystem, distinct from all other family subsystems (such as the dyadic parents’ relationship; the dyadic parenting relationships of each parent with each child; the siblings’ subsystem). The coparenting relationship is different from—and should not be conflated with or reduced to—the sum of all the relationships within the family system, including the marital-relationship, the parent-child relationship, and the whole family system (e.g., Kerig, 2019; Minuchin, 1974; Margolin, 2001; McHale, 1997; Van Egeren & Hawkins, 2004; Teubert & Pinquart, 2010). Within this family systems perspective, the construct of coparenting elucidates why conflicted and even highly conflicted parents can nevertheless still parent their child(ren) competently and effectively (Pruett et al., 2017, 2019).

Coparenting research has tended so far to focus on families adjusting to parental separation/divorce, which was the original context in which attention to coparenting first emerged 5 decades ago (Margolin et al., 2001). However, coparenting refers to the coordination and distribution of parental tasks and roles taking place across all forms of family dynamics and arrangements. Coparenting is a key dynamic of families whether intact, separated/divorced, same-sex, composite stepfamilies, multiple-households, multi-generational, non-romantic contractual parenting arrangements, and other informal arrangements involving multiple primary caregivers (Feinberg, 2003; Irace, 2011; Saini et al., 2019).

The study of coparenting embraces an ‘all-gender parenting’ framework (Adler & Lentz, 2015; Cabrera & Tamis-LeMonda, 2013; Pattnaik, 2012) which affirms that parenting is practiced by people of all genders, and that parent participation in parenting tasks and roles is distinct from gender identifications (Doucet, 2013; Miller, 2010). The coordination and distribution of parental tasks and roles—coparenting—should hence be theorized, measured, and studied across all family dynamics and arrangements, without centering or otherwise privileging the patriarchal heteronormative family ideal (Amato & Afifi, 2006; Cabrera et al., 2012; Cooper, 2019; Fass, 2017; Johnson et al., 2014; Luxton, 2011).

Tremendous advances have been made in the theorization and study of coparenting in the past few decades (e.g., Feinberg, 2003; Molla Cusí et al., 2020), with increasing published reports on the effects of coparenting across family dynamics and arrangements (McHale & Sirotkin, 2019; Pruett & Pruett, 2009). Molla Cusí et al. (2020), for example, completed a systematic review of available measures of coparenting, examining the main characteristics and psychometric properties of these measures and found 26 published instruments designed to assess coparenting, including the long version of the CoPAFS (Saini et al., 2019). Based on their review, Molla Cusí et al. (2020) found that the study of coparenting is hampered by siloed attempts to define, measure and examine the effects of various aspects of coparenting on family functioning and child development along discrete lines of family status (e.g., single, married, common-law or separated).

Measuring Coparenting Relationships

Though significant heterogeneity exists across studies of the various constructs of coparenting, most studies have identified two high-order dimensions, conflict and support, and several lower-order dimensions, including triangulation (in the special and limited sense of involving parent-child coalitions that undermine the other parent and blur parent-child boundaries; Margolin et al., 2001); coparenting alliance (Hock & Mooradian, 2012, 2013; Van Egeren & Hawkins, 2004); childrearing agreement; division of labor in childrearing; support and undermining actions between co-parents; and joint family management of interactions (Feinberg, 2003; McHale & Irace, 2011).

Coparenting, conceptualized and explored within a family systems theory framework, foregrounds an understanding of coparenting as multidimensional, with the specific salient dimensions relating to features of interpersonal relations rather than individual personality characteristics, biographical-developmental indices, or individual patterns of behavior.

While there are psychometrically robust measures available for both intact and separated coparenting (Feinberg et al., 2012; Feinberg & Kan, 2008; McHale, 1997; McHale et al., 2008; Teubert & Pinquart, 2011), as aforementioned, there has been a lack of validated psychometrically robust measures reliably capable of adequately capturing the salient dimensions of the construct of coparenting across intact and separated multi-domain coparenting configurations (Molla Cusí et al., 2020).

Based on the review of the literature and an analysis of coparenting measures (Feinberg et al., 2012; Feinberg & Kan, 2008; McHale et al., 2008; McHale, 1997; Teubert & Pinquart, 2011), the 56-item Coparenting Across Family Structures Scale (CoPAFS) was developed and piloted (Saini et al., 2019). The scale captured nine dimensions of coparenting identified in the literature: (1) Communication; (2) Sharing; (3) Anger; (4) Restrictive coparenting; (5) Facilitative coparenting; (6) Respect; (7) Trust; (8) Conflict; and (9) Valuing the involvement of the other coparent. For each of the scale’s 56 items, respondents were asked to rate their agreement (ranging from 1—strongly agree—to 5—strongly disagree) with a statement concerning their coparenting relationship.

Examples for the items in the scale are: “I usually just give in to the other parent so we do not argue”; “We can usually find solutions about parenting that we are both happy with”; “I get annoyed easily about the mistakes that the other parent makes with our child”; “The other parent undercuts my decisions”; “We have similar hopes and dreams for our child”; “We generally agree on how to discipline our child”; or “Although we don’t always agree, we respect each other’s differences as parents”. The overall score for each subscale was calculated by a simple non-weighted addition of the scores on each of the subscales’ composing items, and the entire scale overall score was calculated by a simple non-weighted addition of the scores on each of the composing subscales, or in cases where only the total score for the entire scale is needed, a non-weighted addition of all the 56 items.

The initial pilot and validation study of the 56-item CoPAFS scale demonstrated the scale’s reliability and overall strong psychometric properties (Saini et al., 2019). The internal consistency of each of the 9 subscales and the CoPAFS scale as a whole, expressed as a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient, was good with only the Facilitative-Coparenting subconstruct scoring below the 0.7 cutoff. Intercorrelations for the total scale and each of the nine subconstructs were significant and ranged between 0.641 (the correlation coefficient for Facilitative coparenting and Conflict) and 0.952 (the correlation coefficient for Respect and the CoPAFS as a whole). The confirmatory factor analysis of the measurement model underlying the CoPAFS scale showed good model fit indices, with all estimates for the 9 subscales (the estimates are linear regression coefficients) significant and ranging between 0.951 and 0.747, explaining between 55.9% and 90.5% of the variation on the CoPAFS scale (Saini et al., 2019).

Purpose of This Study

Molla Cusí et al. (2020) pointed out in their comprehensive systematic review of coparenting tools that there remains the need to create a more thorough measurement of a coparenting tool while maintaining simplicity and ease of use in daily practice. The CoPAFS is designed to assess coparenting in different family configurations, considering that many if not most families move from one kind of structure to another over the years. The measure seeks to enable us to identify salient factors that underlie coparenting in an easy empirical format.

While feedback from respondents during the initial pilot study of the questionnaire was positive, several indicated that the measure had too many items to answer them all in a desirable amount of time. The purpose of the revised shortened tool in this article is to further advance the design of an efficient and psychometrically strong tool to aid research and intervention. Our intent was to explore the stability and psychometric properties of the tool as a measure of coparenting in intact, separated/divorced and families where the parents were never romantically involved, between high- and low-income levels, as well as between fathers and mothers.

Methods

Sampling Recruitment (First Sample)

The first sample was recruited through multiple websites and parenting blogs, as well as the membership emailing list of the Association of Family and Conciliation Courts (AFCC), a multidisciplinary and international organization with over five thousand legal and mental health professionals. Parents were invited to answer an online survey and forward or share the invitation with eligible clients and personal contacts. This research protocol was approved by the Smith College’s IRB Committee. The first page of the online survey consisted of an informed consent that indicated that the decision to participate was private and anonymous and the researchers had no way of knowing who specifically among those receiving the invitation to participate ended up answering the survey.

Inclusion Criteria (First Sample)

The inclusion criteria were: (1) being a parent with a child under the age of 18 years of age at the time of completing the survey; (2) being a parent who shares parenting in some capacity with at least one other parent; and (3) being a parent who is able to read English in order to provide informed consent and complete the survey.

Study Participants (First Sample)

The participants were 252 parents (81.7% mothers; 18.3% fathers) who completed the online coparenting survey on SurveyMonkey (https://www.surveymonkey.com). Of these, 219 participants (87%) completed all items. In spite of our efforts to recruit a diverse sample, the majority of the participants self-identified as Caucasian (71.8%), were highly educated (64.3% completed schooling beyond college), employed full-time (70.2%), and reported annual incomes over $80,000 (73%) (see limitations section).

Most of the parents identified as their youngest child’s biological parents (88.5%), while the remaining reported being a stepparent, adoptive parent, or legal parent. Three-quarters of the parents reported having either one child (40%) or two children (36.1%) under the age of 18, with the other participants having three children (10.3%), four children (2.4%), or five children (1.2%).

Over half of the participants were living together with the other parent, either married or in common law relationship (57.9%), a third identified as separated or divorced (33.3%), and the rest reported living together but neither married nor in a common-law relationship (2.8%). On average, participants had been in a relationship with the other parent for eight or more years (76.6%), whether or not they were separated or together at the time of completing the survey.

Sampling Recruitment (Second Sample)

The second sample was recruited through an invitation to answer an online survey relating to coparenting and COVID-19 related stressors, which was circulated in multiple online parenting groups on Facebook. To locate these groups, a search of parenting groups was conducted on Facebook and then invitations to complete the online survey was posted on these Facebook groups. The online link was open for parents to participate between March 2020 and March 2021. This research protocol was approved by the Smith College’s IRB Committee. Similar to the first study, the first page of the online survey consisted of an informed consent that indicated that the decision to participate was private and anonymous and the researchers had no way of knowing who specifically among those receiving the invitation to participate ended up answering the survey.

Inclusion Criteria (Second Sample)

Inclusion criteria for participation in the survey was: (1) self-identifying as a parent with a child under the age of 18 at the time of answering the survey; (2) self-identifying as sharing parenting with at least one other adult; (3) being able to read English in order to complete the survey. Participants were not compensated for participating in the survey.

Study Participants (Second Sample)

The final sample consisted of 329 participants, 270 (82.1%) identified as mothers and 54 (16.4%) identified as fathers (5 participants—1.5%—did not report their gender identity). Almost half of the participants (151 parents—45.9%) were in their 30 s, 128 parents (38.9) were in their 40 s, 25 parents (7.6%) were in their 20 s and 25 (7.6%) were in their 50 s or older. More than half of the parents (179–54.4%) had a university degree or above, 96 parents (29.2%) had some post-secondary education and 38 (11.5%) had a high school diploma or less.

The sample again was overwhelmingly White (269 parents—81.8%), with only 14 (4.3%) identifying as black, 20 (6.1%) identifying as Latinx, 11 (3.3%) identifying as Asian and 6 (1.8%) identifying as indigenous/Native Americans. More than half the sample (182–55.3%) reported an annual pre-tax income of $60,000 or more, and 146 (44.3%) reported an annual pre-tax income of $59,000 or less (see limitations section). Sixty percent of the sample (198 parents) were separated/divorced, 82 parents (24.9%) were never together with the coparent of their child, and 48 parents (14.6%) reported living in an intact family (cohabiting, married or common law with the coparent).

Data Analysis

In order to develop a psychometrically robust short form to the CoPAFS scale, we followed Smith et al. (2000) set of criteria for a rigorous development and validation of short forms. To identify a smaller set of items that captures as much of the variation as possible, while covering as much as possible of the content indicated by the full 56-item CoPAFS scale, we have generated two lists of such items. The first list (29 items) was generated by conducting an exploratory factor analysis, while the second list (28 items) was constructed from the highest scoring items on each of the 9 subscales composing the 56-item CoPAFS. The two lists of items were then juxtaposed, compared and reviewed by the research team, who on the basis of content-analysis and attention to the need to preserve the content coverage of the original scale, agreed on a set of 27 items, representing the independently generated lists of items.

In order to show that the short-form 27-items CoPAFS was reliable and valid, the psychometric properties of the short-form scale and the 5 subscales around which the 27-items were hypothesized to cluster, were calculated on the basis of the above described first sample. The internal consistency of each of the 5 subscales and the short-form CoPAFS scale as a whole, expressed as a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient, were measured as indicators of the internal consistency of each subscale and the total short-form CoPAFS scale.

Confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) were conducted with a maximum likelihood estimation method for each of the 5 subscales on both the first and the second samples. Confirmatory factor analysis assesses how well the measurement model underpinning the scale captures the covariance between all of the items that compose each of the 5 subscales, or in the case of the whole short-form CoPAFS scale, how well the measurement model captures the covariance between the 5 subscales. The analysis also estimates the regression coefficients for each item or subscale and the proportion of the variation of each item or subscale predicted by the model. The CFA hence provides information about the construct validity, the extent to which the subscale or scale actually measures what it was intended to measure.

Following Kline (2010), the model fit indices calculated and reported were first a chi-squared test indicating the difference between observed and expected covariance metrics. The P value of the Chi-squared test should be above 0.005 (not significant). However, as this is strongly influenced by sample size, this may be misleading in either small samples (leading to acceptance of an inappropriate model) or large samples (leading to rejection of appropriate models). Kline (2010) suggests that sample size above 200 cases may result in non-significance even when the model is appropriate. The second type of model fit indices calculated and reported was the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), which measures the discrepancy between the hypothesized model, with optimally chosen parameter estimates, and the covariance matrix. Thirdly, the root mean square residual (RMR) shows the square root of the discrepancy between the sample covariance matrix and the model covariance matrix. The Goodness of fit index (GFI) is a measure of fit between the hypothesized model and the observed covariance matrix. The normed fit index (NFI) analyzes the discrepancy between the chi-squared value of the hypothesized model and the chi-squared value of a null of baseline model in which all the variables are assumed to be uncorrelated. Comparative fit index (CFI) analyzes the model fit by examining the discrepancy between the data and the hypothesized model, while adjusting for the issues of sample size inherent in the chi-squared test of model fit.

In order to test the stability of the short form CoPAFS’ factor structure across different groups, the second sample was divided into 6 sub-samples: (1) North-American mothers cohabiting with the other parent of the child; (2) North American mothers separated/divorced from the coparent of the child; (3) North American mothers who were never together with the coparent of the child; (4) North American mothers with a yearly pre-tax income of $60.000 or above; (5) North American mothers with a yearly pre-tax income of under $60,000; and (6) fathers. To test for the invariance of the model across the groups, a multigroup confirmatory factor analysis (Putnick & Bornstein, 2016) was conducted. The invariance was tested for configural invariance, examining whether the overall factor structure stipulated by the CoPAFS 27-item measurement model fits each of the groups; metric invariance, examining whether the factor loadings (the scale item-latent factor relationship) on the CoPAFS 27-item are equivalent across the groups; and scalar invariance, examining whether the item intercepts for the CPAFS 27-item are equivalent across the groups.

Results

Exploratory Factor Analysis

To test whether the data were suitable for factor analysis, the Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity was conducted. Results showed that the sample was suitable for factor analysis (Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity = approximate chi-square 12153.72 (df = 1540) p. < 0.00). To test for sampling adequacy, the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy was conducted, and the result was 0.96 (on a scale of 0 to 1, ‘marvelous’ according to (Kaiser, 1960). Next, a correlational matrix was produced. An inspection of the correlation matrix confirmed that the majority of correlations were above 0.30 as recommended for conducting a factor analysis. The data were screened for univariate outliers. The minimum amount of data for factor analysis was satisfied, with a final sample size of 218.

The next step was to explore the degree to which the common factor model predicts the correlation structure of the 56 items measure. An initial analysis was run to obtain eigenvalues for each factor in the data. Eight factors had eigenvalues over Kaiser’s criterion of 1 and combined explained 71.78% of the variance. The initial eigenvalues over one showed that the first factor explained 51.84% of the variance, the second factor 4.26% of the variance, the third factor 3.94% of the variance, the fourth factor 3.45%, the fifth factor 2.31%, the sixth factor 2.12%, the seventh factor 2.03%, and the eighth factor 1.80%. However, inspection of the scree plot inflection points clearly indicated that 4 factors should be retained, that is, the four factors with eigenvalues higher than 1.933. These factors were also eminently interpretable from a theoretical perspective (Fabrigar & Wegener, 2012).

A maximum likelihood exploratory factor analysis was conducted on the 56 items in which respondents indicated how much they agreed with statements concerning the nine domains of coparenting initially suggested based on the literature review. An oblique rotation was conducted on the initial factor solution, which is appropriate given that the factors were correlated. The four factors explained a cumulative variance of 63.503%.

As Table 1 shows, the rotated pattern matrix of the four components was interpreted to suggest retaining 28 items for the Coparenting Across Family Structures, divided into four subscales - factors: Factor 1, level of Respect between parents, explained 26.547% of the variance; Factor 2, the amount of Trust for the other parent, explained 19.120%; Factor 3, the level of Anger/Hostility between the parents, explained 8.264%; and Factor 4, the degree of Valuing the other parent in the lives of the children, explained 5.362%.

Table 1.

The Rotated Pattern Matrix of the Four Components

| Items | Factor | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| 17. The other parent respects what I bring to parenting our child | 0.932 | |||

| 11. can talk easily with the other parent about activities I would like to do with our child | 0.869 | |||

| 4. I feel comfortable in sharing my thoughts about parenting with the other | 0.836 | |||

| 10. I am careful about sharing my thoughts about parenting with the other parent in fear that my words will be used against me somehow | 0.814 | |||

| 15. Although we don’t always agree, we respect each other’s differences as parents | 0.808 | |||

| 36, I work well with the other parent when decisions need to be made about our child | 0.804 | |||

| 52. I try to be more involved, but the other parent won’t let me have an opinion | 0.793 | |||

| 12. When we meet face to face, the other parent and I are friendly or polite to each other | 0.786 | |||

| 35. The other parent asks my opinion on parenting issues | 0.771 | |||

| 46. I feel awkward when I am with the other parent | 0.770 | |||

| 45. It is better to be away from, or uninvolved with, the other parent to make sure we don’t argue | 0.754 | |||

| 41. We do not have a good way of dealing with our differences as parents | 0.746 | |||

| 9. The other parent pressures me to parent differently | 0.725 | |||

| 40. We don’t make decisions about our child because we are unable to talk through what we both agree on | 0.710 | |||

| 16. We share big decisions when it comes to parenting | 0.707 | |||

| 53. The other parent pretends to get along with me but I know that it is just an act | 0.689 | |||

| 20. I have given up trying to cooperate with the other parent | 0.662 | |||

| 44. The more I try to involve the other parent in decision making, the more we get into conflict | 0.646 | |||

| 6. The other parent undercuts my decisions | 0.627 | |||

| 7. The other parent gets in the way of my relationship with the child | 0.625 | |||

| 3. We can usually find solutions about parenting that we are both happy with | 0.605 | |||

| 54. We parent better when we make decisions together | 0.604 | |||

| 13. We have similar hopes and dreams for our child | 0.560 | |||

| 38. When there is a problem with our child, we work on finding answers together | 0.552 | |||

| 42. I could parent better if the other parent stayed out of my business | 0.546 | |||

| 34. I know I can count on the other parent if I need help in parenting | 0.506 | 0.436 | ||

| 8. We both view our child’s strengths and weaknesses in similar ways | 0.505 | |||

| 28. I value the other parent’s input about decisions that affect our child | 0.461 | |||

| 14. We generally agree on how to discipline our child | 0.445 | |||

| 51. I don’t think it is helpful to talk with the other parent about decisions that need to be made about our child | 0.440 | |||

| 1. I am satisfied with how we share the work of parenting | 0.440 | |||

| 2. I usually just give in to the other parent so we do not argue | ||||

| 18. I find ways to help our child have a good relationship with the other parent1 | ||||

| 49. My child would be better off seeing less of the other parent | ||||

| 39. When making decisions, we argue about who is right | ||||

| 30. I have trouble controlling my anger when around the other parent. | 0.732 | |||

| 31. I am hostile or bitter in my conversations with the other parent | 0.657 | |||

| 29. I feel out of control when speaking with the other parent | 0.422 | 0.438 | ||

| 5. I get annoyed easily about the mistakes that the other parent makes with our child | ||||

| 47. The other parent tries to be a good parent but does not know enough about parenting to be the kind of parent our child needs | 0.917 | |||

| 26. I worry about my child while in the other parent’s care | 0.700 | |||

| 37. I get little support from the other parent to help out with the work of parenting | 0.600 | |||

| 24. I trust the other parent with our child | 0.585 | |||

| 55. I need to ‘go behind’ the other parent to fix the mess left behind | 0.565 | |||

| 22. I value the other parent’s parenting skills | 0.527 | |||

| 33. I disagree with the choices that the other parent makes about our child | 0.498 | |||

| 21. I try to involve the other parent but my efforts often go nowhere | −0.485 | |||

| 19. I find it difficult to support the other parent’s relationship with our child | 0.441 | |||

| 50. I pretend to support the other parent’s decisions but in the end I do what I think is best for our child | 0.423 | |||

| 25. It’s important that the other parent is involved in our child’s life | 0.611 | |||

| 43. If the other parent needs to make a change in the parenting schedule, I go out of my way to make the change | 0.476 | |||

| 23. It is important that my child loves both parents | 0.446 | |||

| 48. It is part of my job as a parent to positively influence my child’s relationship with the other parent | 0.429 | |||

| 27. It’s important that our child does not hear us talking negatively about each other (in person, on the phone, or on video conference) | ||||

| 56. We try not to disagree in front of our child | ||||

| 32. I encourage my child to talk to the other parent directly if something is bothering him/her about their relationship | ||||

The list of the 28 items identified by the EFA was juxtaposed and compared with the list of the 29 highest scoring items (Table 2).

Table 2.

The 56 Items Loading on Each of the 9 Factors

| Subscale | Statements | P | Standardized regression weight | Squared multiple correlations (variation predicted) | Included in list of highest scoring items | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sharing | 1 | I am satisfied with how we share the work of parenting | <0.01 | 0.766 | 0.587 | |

| 2 | We share big decisions when it comes to parenting | <0.01 | 0.841 | 0.708 | yes | |

| 3 | I get little support from the other parent to help out with the work of parenting | <0.01 | 0.731 | 0.534 | ||

| 4 | When there is a problem with our child, we work on finding answers together | <0.01 | 0.904 | 0.823 | yes | |

| Communication | 1 | I usually just give in to the other parent so we do not argue | <0.01 | 0.308 | 0.095 | |

| 2 | We can usually find solutions about parenting that we are both happy with | <0.01 | 0.774 | 0.599 | ||

| 3 | I feel comfortable in sharing my thoughts about parenting with the other | <0.01 | 0.843 | 0.711 | yes | |

| 4 | I can talk easily with the other parent about activities I would like to do with our child | <0.01 | 0.824 | 0.678 | ||

| 5 | When we meet face to face, the other parent and I are friendly or polite to each other | <0.01 | 0.783 | 0.613 | ||

| 6 | The other parent asks my opinion on parenting issues | <0.01 | 0.854 | 0.729 | yes | |

| 7 | I work well with the other parent when decisions need to be made about our child | <0.01 | 0.905 | 0.819 | yes | |

| 8 | We don’t make decisions about our child because we are unable to talk through what we both agree on | <0.01 | 0.813 | 0.661 | ||

| 9 | We do not have a good way of dealing with our differences as parents | <0.01 | 0.86 | 0.739 | yes | |

| Anger | 1 | I get annoyed easily about the mistakes that the other parent makes with our child | <0.01 | 0.450 | 0.203 | |

| 2 | The other parent pretends to get along with me but I know that it is just an act | <0.01 | 0.772 | 0.596 | ||

| 3 | It is better to be away from, or uninvolved with, the other parent to make sure we don’t argue | <0.01 | 0.634 | 0.402 | ||

| 4 | I feel awkward when I am with the other parent | <0.01 | 0.616 | 0.380 | ||

| 5 | I feel out of control when speaking with the other parent | <0.01 | 0.896 | 0.803 | yes | |

| 6 | I have trouble controlling my anger when around the other parent. | <0.01 | 0.848 | 0.720 | yes | |

| 7 | I am hostile or bitter in my conversations with the other parent | <0.01 | 0.703 | 0.494 | ||

| Restrictive coparenting | 1 | The other parent gets in the way of my relationship with the child | <0.01 | 0.789 | 0.622 | yes |

| 2 | I find it difficult to support the other parent’s relationship with our child | <0.01 | 0.680 | 0.463 | ||

| 3 | I have given up trying to cooperate with the other parent | <0.01 | 0.810 | 0.657 | yes | |

| 4 | I could parent better if the other parent stayed out of my business | <0.01 | 0.832 | 0.692 | yes | |

| 5 | I try to be more involved, but the other parent won’t let me have an opinion | <0.01 | 0.796 | 0.634 | yes | |

| Trust | 1 | We both view our child’s strengths and weaknesses in similar ways | <0.01 | 0.697 | 0.486 | |

| 2 | I am careful about sharing my thoughts about parenting with the other parent in fear that my words will be used against me somehow | <0.01 | 0.718 | 0.516 | ||

| 3 | We have similar hopes and dreams for our child | <0.01 | 0.766 | 0.588 | ||

| 4 | We generally agree on how to discipline our child | <0.01 | 0.795 | 0.632 | yes | |

| 5 | I trust the other parent with our child | <0.01 | 0.827 | 0.683 | yes | |

| 6 | I worry about my child while in the other parent’s care | <0.01 | 0.823 | 0.677 | yes | |

| 7 | I know I can count on the other parent if I need help in parenting | <0.01 | 0.875 | 0.766 | yes | |

| 8 | I pretend to support the other parent’s decisions but in the end I do what I think is best for our child | <0.01 | 0.496 | 0.246 | ||

| 9 | I need to ‘go behind’ the other parent to fix the mess left behind | <0.01 | 0.676 | 0.457 | ||

| Respect | 1 | The other parent pressures me to parent differently | <0.01 | 0.610 | 0.372 | |

| 2 | Although we don’t always agree, we respect each other’s differences as parents | <0.01 | 0.884 | 0.782 | yes | |

| 3 | The other parent respects what I bring to parenting our child | <0.01 | 0.857 | 0.735 | yes | |

| 4 | I value the other parent’s parenting skills | <0.01 | 0.818 | 0.669 | yes | |

| 5 | I value the other parent’s input about decisions that affect our child | <0.01 | 0.812 | 0.659 | yes | |

| 6 | The other parent tries to be a good parent but does not know enough about parenting to be the kind of parent our child needs | <0.01 | 0.529 | 0.280 | ||

| Facilitating coparenting | 1 | I find ways to help our child have a good relationship with the other parent | <0.01 | 0.716 | 0.512 | yes |

| 2 | I try to involve the other parent but my efforts often go nowhere | <0.01 | 0.482 | 0.235 | ||

| 3 | I encourage my child to talk to the other parent directly if something is bothering him/her about their relationship | <0.01 | 0.361 | 0.131 | ||

| 4 | If the other parent needs to make a change in the parenting schedule, I go out of my way to make the change | <0.01 | 0.482 | 0.232 | ||

| 5 | It is part of my job as a parent to positively influence my child’s relationship with the other parent | <0.01 | 0.610 | 0.372 | yes | |

| Coparenting as value | 1 | It is important that my child loves both parents | <0.01 | 0.484 | 0.234 | |

| 2 | It’s important that the other parent is involved in our child’s life | <0.01 | 0.732 | 0.535 | yes | |

| 3 | It’s important that our child does not hear us talking negatively about each other (in person, on the phone, or on video conference) | 0.068 | 0.136 | 0.019 | ||

| 4 | My child would be better off seeing less of the other parent | <0.01 | 0.803 | 0.645 | yes | |

| 5 | I don’t think it is helpful to talk with the other parent about decisions that need to be made about our child | <0.01 | 0.804 | 0.647 | yes | |

| 6 | We parent better when we make decisions together | <0.01 | 0.747 | 0.558 | yes | |

| 7 | We try not to disagree in front of our child | <0.01 | 0.272 | 0.074 | ||

| Conflict | 1 | The other parent undercuts my decisions | <0.01 | 0.801 | 0.642 | yes |

| 2 | I disagree with the choices that the other parent makes about our child | <0.01 | 0.666 | 0.444 | ||

| 3 | When making decisions, we argue about who is right | <0.01 | 0.557 | 0.311 | ||

| 4 | The more I try to involve the other parent in decision making, the more we get into conflict | <0.01 | 0.791 | 0.626 | yes |

A final 27-item short form CoPAFS scale was created on the basis of reconciling the 2 independently generated lists of items (Table 2). Though the results of the EFA suggested 4 factors, and the list of the highest scoring items retained the original 9-factor structure, the authors after carefully reviewing the lists and considering the information provided by the quantitative indicators informing each of the lists in light of the authors’ practice experience and insight, determined that the items organized best a clustering around 5 factors: Communication; Respect; Trust; Hostility; and Valuing involvement of the coparent. Cronbach’s coefficient for the short-form 27-item CoPAFS scale was 0.968 for the first sample indicating excellent internal consistency. Table 3 depicts the scale and subscale intercorrelations for the total scale and each of the 5 factors on the basis of the first sample. All were significant and ranged between 0.763 (Trust and Respect) and 0.985 (the 27-item and the 56-item CoPAFS scales).

Table 3.

Correlational Matrix

| Communication | Respect | Trust | Hostility | Value | 27-item CoPAFS | 56-item CoPAFS | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Communication | Pearson Correlation | 1 | ||||||

| Sig. (2-tailed) | ||||||||

| Respect | Pearson Correlation | 0.914 | 1 | |||||

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.000 | |||||||

| Trust | Pearson Correlation | 0.722 | 0.763 | 1 | ||||

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||||||

| Hostility | Pearson Correlation | 0.792 | 0.826 | 0.804 | 1 | |||

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |||||

| Value | Pearson Correlation | 0.786 | 0.810 | 0.781 | 0.757 | 1 | ||

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||||

| 27-item CoPAFS | Pearson Correlation | 0.918 | 0.936 | 0.906 | 0.918 | 0.889 | 1 | |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |||

| 56-item CoPAFS | Pearson Correlation | 0.914 | 0.934 | 0.873 | 0.908 | 0.880 | 0.985 | 1 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||

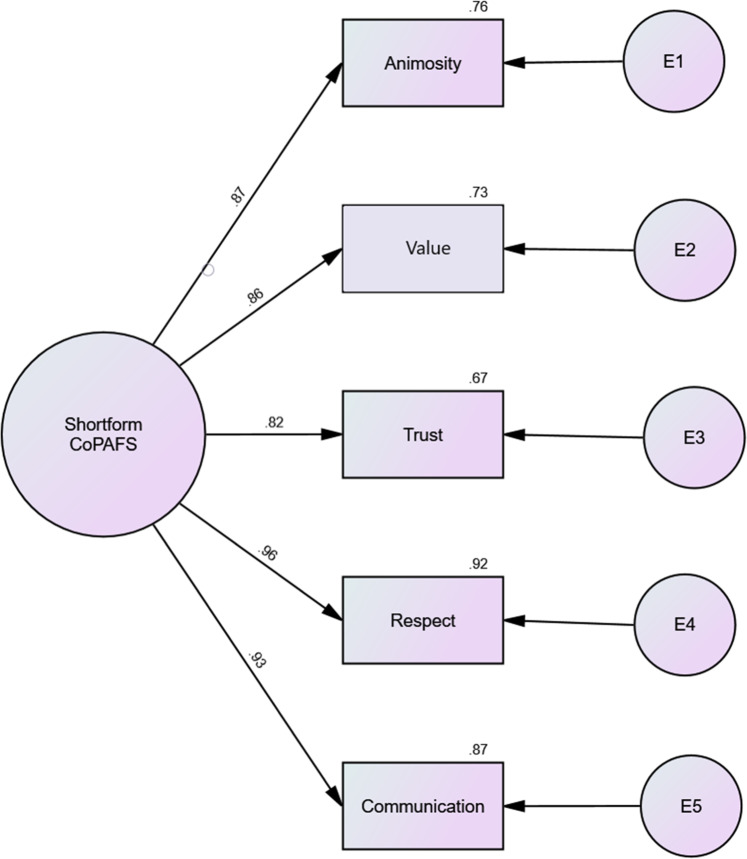

Figure 1 presents the results of the confirmatory factor analysis of the measurement model underlying the short form 27-item CoPAFS scale for sample 1. As evident in Table 4, the Chi-Square test indicating the difference between the observed and predicted covariance metrics was significant for both samples; for a good model fit, the P value should be above 0.05, representing non-significance and the test result itself as close to 0 as possible. This however is often due to a sample size > than 200 (Kline, 2010).

Fig. 1.

Five Factor Model of Coparenting

Table 4.

Model Fit Indices and Subscale Estimates for the Short-form 27-item CoPAFS Scale Measurement Model for Both Samples

| Chi-Square | DF | P | RMR | GFI | CFI | NFI | RMSEA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample 1 | 69.83 | 5 | <0.01 | 0.976 | 0.893 | 0.952 | 0.949 | 0.227 |

| Sample 2 | 43.97 | 5 | <0.01 | 0.885 | 0.942 | 0.958 | 0.953 | 0.164 |

For the first sample, excellent model fit was indicated by the Goodness of Fit Index (GFI), the Normal Fit Index (NFI) and the Comparative Fit Index (NFI), the first just shy of its cutoff points and the latter two above their respective cutoff points. At the same time, the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation Measure (RMSEA), which should be below 0.06 in order to indicate a good model fit, and the Root Mean Square Error Measure (RMR), which should be below 0.08 in order to indicate a good model fit, were both above the required cutoff point. Taken together, and given that all estimates for the 5 subscales were significant and ranged between 0.82 and 0.96, explaining between 67% and 92% of the variation on the short form 27-item CoPAFS scale, the measurement model underlying the short-form 27-item CoPAFS scale fitted the data of the first pilot study well enough to merit further testing on new samples. The second sample showed better results, with the CFI, NFI and GFI above their cut off points, the Chi square almost halved, the RMR and RMSEA lower (albeit still higher than recommended. As summarized in Table 5, all factors were significantly predicted by the underlying construct, regression coefficients ranging between 0.75 and 0.87, and accounting for between 56% and 75% of the variation on each of the factors.

Table 5.

Regression Coefficients and Proportion of Variation Accounted for All Factors in All Samples and Subgroups of Sample 2

| Hostility | Value | Respect | Trust | Communication | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample 1 | 0.87 (76%) | 0.85 (73%) | 0.96 (92%) | 0.81 (67%) | 0.93 (87%) |

| Sample 2 | 0.75 (56%) | 0.74 (55%) | 0.88 (77%) | 0.82 (67%) | 0.86 (73%) |

| Fathers | 0.78 (61%) | 0.70 (49%) | 0.94 (88%) | 0.77 (60%) | 0.85 (71%) |

| Divorced/Separated | 0.65 (43%) | 0.73 (53%) | 0.81 (66%) | 0.77 (60%) | 0.81 (66%) |

| Never married/together | 0.52 (27%) | 0.67 (45%) | 0.75 (56%) | 0.73 (54%) | 0.65 (42%) |

| Intact | 0.82 (67%) | 0.73 (53%) | 0.94 (88%) | 0.83 (70%) | 0.94 (88%) |

| Income > 60K | 0.83 (69%) | 0.80 (64%) | 0.91 (84%) | 0.89 (79%) | 0.88 (78%) |

| Income < 60K | 0.59 (34%) | 0.66 (43%) | 0.79 (63%) | 0.72 (52%) | 0.82 (67%) |

The second sample allowed for exploring and testing for model invariance across different groups: 1. mothers and fathers; 2. parents reporting yearly gross income higher than $60,000 and parents reporting a yearly gross income lower than $60,000; 3. Intact, separated/divorced; and those who have never been romantically involved with the coparent of their child(ren). As presented in Table 4, though model fit indices varied across family structures, between high income and low-income mothers and between mothers and fathers, the underlying measurement model displayed promising stability. Table 6, comparing the model fit indices for each of the factors between sample 1 and 2, shows that all factors displayed better model fit indices when tested for the second sample data, with only the underlying measurement model for the Hostility factor still falling below the cutoff points on all reported model fit indices.

Table 6.

Comparing the Model Fit Indices for Each of the Factors Between Samples 1 and 2

| Chi-Square | DF | P | RMR | GFI | CFI | NFI | RMSEA | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample 1 | Hostility | 203.175 | 9 | <0.01 | 0.92 | 0.821 | 0.782 | 0.775 | 0.293 |

| Value | 61.507 | 5 | <0.01 | 0.033 | 0.910 | 0.895 | 0.887 | 0.212 | |

| Respect | 5.133 | 2 | 0.077 | 0.020 | 0.989 | 0.995 | 0.992 | 0.079 | |

| Trust | 103.963 | 14 | <0.01 | 0.079 | 0.894 | 0.903 | 0.890 | 0.160 | |

| Communication | 5.243 | 5 | 0.387 | 0.016 | 0.992 | 1.00 | 0.994 | 0.014 | |

| Sample 2 | Hostility | 124.121 | 9 | <0.01 | 0.160 | 0.857 | 0.733 | 0.722 | 0.210 |

| Value | 7.0171 | 5 | 0.215 | 0.036 | 0.991 | 0.994 | 0.981 | 0.038 | |

| Respect | 37.595 | 2 | <0.01 | 0.112 | 0.935 | 0.922 | 0.918 | 0.248 | |

| Trust | 28.907 | 14 | <0.01 | 0.071 | 0.971 | 0.976 | 0.954 | 0.061 | |

| Communication | 3.691 | 5 | 0.595 | 0.027 | 0.995 | 1.000 | 0.993 | 0.000 | |

We ran 3 multigroup invariance tests of the model, each testing for configural, metric and scalar invariance. We tested the invariance of the model between mothers and fathers (see Table 7); the invariance of the model between those reporting gross incomes below 60K per year and those reporting gross incomes above 60K per year (see Table 8); and the invariance of the model between intact families, separated divorced families and families where the parents were never romantically involved (see Table 9). As indicated in Table 9, the metric and the scalar model invariances across family dynamics could not be confirmed on the basis of the data in sample 2, since the hypothesis that the measurement model fit significantly differs between intact, separated/divorced and never together families (the null hypothesis) could not be rejected.

Table 7.

Multigroup Invariance CFA for Fathers/Mothers

| Model | Comp model | Chi-Square (P value) |

DF | CFI | RMSEA | NFI | Δ chi-square | Δ df | Δ CFI | Δ RMSEA | Δ NFI | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1—Configural invariance | N/P |

48.43 (p < 0.01) |

10 | 0.95 | 0.10 | 0.94 | N/P | N/P | N/P | N/P | N/P | N/P |

| M2—Metric Invariance | M1 |

52.31 (P < 0.01) |

14 | 0.95 | 0.09 | 0.94 | 3.88 | 4 | 0 | 0.01 | 0 | Accept |

| M3—Scalar invariance | M2 |

67.17 (P < 0.01) |

18 | 0.94 | 0.09 | 0.92 | 14.86 | 4 | 0.01 | 0 | 0.02 | Accept |

N = 329, n group 1 (fathers) = 54 n group 2 (mothers) 270

Table 8.

Multigroup Invariance CFA for above 60k/below 60k

| Model | Comp model | Chi-Square (P value) |

DF | CFI | RMSEA | NFI | Δ chi-square | Δ df | Δ CFI | Δ RMSEA | Δ NFI | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1—Configural invariance | N/P |

51.60 (P < 0.01) |

10 | 0.95 | 0.13 | 0.94 | N/P | N/P | N/P | N/P | N/P | N/P |

| M2—Metric Invariance | M1 |

52.51 (P < 0.01) |

14 | 0.95 | 0.09 | 0.94 | 0.91 | 4 | 0 | 0.04 | 0 | Accept |

| M3—Scalar invariance | M2 |

63.78 (P < 0.01) |

19 | 0.95 | 0.08 | 0.93 | 11.27 | 5 | 0 | 0.01 | 0.01 | Accept |

N = 329, n group 1 (above 60K) 182, n group 2 (below 60K) 146

Table 9.

Multigroup Invariance CFA for Intact; Separated/Divorced; Never Together

| Model | Comp model | Chi-Square (P value) |

DF | CFI | RMSEA | NFI | Δ chi-square | Δ df | Δ CFI | Δ RMSEA | Δ NFI | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1—Configural invariance | N/P |

57.19 (P < 0.01) |

15 | 0.94 | 0.09 | 0.92 | N/P | N/P | N/P | N/P | N/P | N/P |

| M2—Metric Invariance | M1 |

95.74 (p < 0.01) |

23 | 0.89 | 0.09 | 0.86 | 38.55 | 8 | 0.05 | 0 | 0.06 | Reject |

| M3—Scalar invariance | M2 |

105.77 (P < 0.01) |

31 | 0.89 | 0.08 | 0.85 | 10.03 | 8 | 0 | 0.01 | 0.01 | Reject |

n = 329, n group 1 (intact) 48; n group 2 (separated divorce) 198; n group 3 (never together) 82

Discussion

Despite the importance of coparenting relationships for child development (Feinberg, 2003; McHale, 2007) reliable and valid methods for assessing coparenting relationships across all family structures are not yet available. To address this gap and develop a valid and brief instrument, this study reported the development of a short-form 27-item version of the 56-item Coparenting Across Family Structures (CoPAFS) (Saini et al., 2019) and the initial pilot testing of its validity and psychometric properties.

The results of this study provide initial promising evidence for the strong psychometric properties of the short-form 27-item CoPAFS scale. The short-form scale was very strongly correlated with the 56-item CoPAFS scale (Pearson correlation = 0.98), as were the intercorrelations between the 5 subconstructs—which were all significant and ranged between 0.763 and 0.914. The internal consistency of the short-form scale was excellent (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.96). The confirmatory factor analysis for the 27-item CoPAFS scale measurement model showed good model fit indices and all estimates for the 5 subconstructs were significant and ranged between 0.82 and 0.96, explaining between 67% and 92% of the variation on the short form 27-item scale.

While the 56-item CoPAFS was composed of 9 subconstructs, the findings of this study suggest that the short-form 27-item CoPAFS provides a strong composite model that includes 5 subconstructs: Communication; Hostility; Respect; Trust; and Valuing the involvement of the coparent (see Table 10). In the transition from a 9-subconstruct model to a 5-subconstruct model, Anger and Conflict were found to be better conceptualized from a practice perspective as a single factor—Hostility. At the same time, the factors “Facilitative Coparenting”; “Restrictive coparenting” and Sharing were found to be expressions and by-products of the 5 factors rather than primary subconstructs in their own right.

Table 10.

Co-Parenting Across Family Structures (CoPAFS-27)

| 1. It is important that my child loves both parents | V |

| 2. I value the other parent’s parenting skills | R |

| 3. I feel awkward when I am with the other parent | A* |

| 4. I work well with the other parent when decisions need to be made about our child | C |

| 5. I am hostile or bitter in my conversations with the other parent | A* |

| 6. I can talk easily with the other parent about activities I would like to do with our child | C |

| 7. I disagree with the choices that the other parent makes about our child | A* |

| 8. I don’t think it is helpful to talk with the other parent about decisions that need to be made about our child | V* |

| 9. I feel comfortable in sharing my thoughts about parenting with the other parent | C |

| 10. I feel out of control when speaking with the other parent | A* |

| 11. I find it difficult to support the other parent’s relationship with our child | T* |

| 12. The other parent asks my opinion on parenting issues | C |

| 13. My child would be better off seeing less of the other parent | V* |

| 14. Although we don’t always agree, we respect each other’s differences as parents | R |

| 15. I get little support from the other parent to help out with the work of parenting | T* |

| 16. We parent better when we make decisions together | V |

| 17. I have trouble controlling my anger when around the other parent | A* |

| 18. I need to ‘go behind’ the other parent to fix the mess left behind | T* |

| 19. When we meet face to face, the other parent and I are friendly or polite to each other | C |

| 20. I pretend to support the other parent’s decisions but in the end, I do what I think is best for our child | T* |

| 21. I trust the other parent with our child | T |

| 22. I try to be more involved, but the other parent won’t let me have an opinion | R* |

| 23. The other parent respects what I bring to parenting our child | R |

| 24. I worry about my child while in the other parent’s care | T* |

| 25. It is better to be away from, or uninvolved with, the other parent to make sure we don’t argue | A* |

| 26. It’s important that the other parent is involved in our child’s life | V |

| 27. The other parent tries to be a good parent but does not know enough about parenting to be the kind of parent our child needs | T* |

“*” Signifies reverse scoring, V Valuing the other parent, R Respect, A Acrimony, C Communication, T Trust

Consistent with family systems theory, the 5 dimensions of the short form CoPAFS foreground the conditions that foster autonomous, considerate, and coordinated parenting by each of the coparents. The pivotal roles of trust and respect are especially supported by family systems considerations, given that these two dimensions constitute the very conditions of possibility for accepting and supporting the separateness and autonomy of each coparent relationship with each child, its separateness from the relationship between the coparents, and the emergent nature of the overall family adaptive functioning and well-being (Bregman & White, 2010).

Implications for Practice

Empirical understanding of coparenting is pivotal for supporting interventions aimed at improving family functioning and child relationships and outcomes. In view of the unprecedented transformation in parenting and family structures in the past decades, assumptions about gender-specific parental roles and the intact heteronormative family structure as the sole model are no longer appropriate, particularly for supporting families who navigate challenges and restructuring due to separation/divorce. Reliably and efficiently assessing coparenting across all family structures is a highly important tool for mental-health and family-law practitioners, allowing them to assess the extent to which coparenting is operating as a positive aspect of their clients’ lives, as well as to identify the specific subconstructs in need of attention.

In view of the variation in the challenges families face due to differing coparenting dynamics, the short-form 27-item CoPAFS allows for increased attention to particular coparenting components, including identification of which aspects need bolstering or support in specific cases. Families who struggle with issues of trust may benefit from a different approach than families whose main challenge is with issues of communication. The shoring up of the former may be a necessary prerequisite to the latter. As such, a valid and efficient tool for identifying where the pertinent issues lie will allow mental health and family law practitioners to better tailor the most appropriate family-based or law-based intervention for their clients. The tool will also provide fast results needed for court-involved families at risk of conflict escalation, with minimum expense involved.

At the same time, the short-form 27-item CoPAFS will allow for research on coparenting dynamics across family structures, that in turn can inform the development of better interventions; provide an accessible assessment of the efficacy of existing interventions; and help identify unmet needs and underserved parents and families. With coparenting heralded as an important component of parenting and reduced stress (e.g., in response to COVID) (Pruett et al., 2019), developing better and more universal assessment tools is a priority in family research.

Better understanding the role of coparenting and the subconstructs composing it will also inform research into how existing laws and policies support or hinder coparenting across all family structures and family-life trajectories. The short-form 27-item CoPAFS offers a means of researching the effects of existing legal and policy regimes on coparenting among the various populations concerned. It will also provide valuable information to promote research-informed policies and legal approaches to family support.

Limitations

The central limitation to this pilot study is that despite efforts to obtain a representative sample, the initial iteration of this instrument utilized a convenience sample populated mostly by highly educated, white, heterosexual mothers, and so we were not able to consider diversity as proposed. The second sample was more diverse, allowing for some comparisons between subgroups, but the sample remained mostly white, with fathers underrepresented, and not enough sexually diverse respondents to allow for comparisons between same-sex and heterosexual parents. While the results are useful for demonstrating promising psychometric properties, our next research iteration will need to specifically address the issue of diversity before additional analyses are conducted on coparenting relationships across family structures in diverse families.

The convenience sampling method is limited because anonymous online surveys are not able to verify the identification of participants, nor the information shared within the survey. There is no way to to track how many individuals received the study invitations compared to the participants who completed the survey and therefore the response rate could not be calculated.

Another limitation is the strong correlations among factors that limit the ability to distinguish the factors as independent constructs. However, the short form can still be a useful instrument clinically, especially for screening and pinpointing areas requiring attention in a coparenting relationship.

Future Research

This paper reported the psychometric properties of the newly developed short-form 27-item CoPAFS scale on the basis of a convenience pilot sample that was populated largely by middle class professionals and more women than men. The next steps in our research program consist of more broadly recruiting respondents in order to test for the stability of the scale’s psychometric properties across gender and sexual identities, family structures and composition, and other axes of variation that may limit the validity of the instrument. In order to test for convergent and discriminant validity, we will also collect data on relationship satisfaction and parenting quality. The following step, after confirming the validity of the scale on the basis of self-reported data, will be to test the scale against coparenting that is externally observed. We intend the CoPAFS scale in its full (56-item) and short (27-item) forms to be useful to agencies as a tool for identifying where and how to intervene, and will hence collect data from agencies using the scale. It is our hope that by publishing these initial results, others will join us in validating and further refining the 27-item CoPAFS scale.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical Approval

The study was reviewed and approved by Smith College’s Institutional Review Board.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Adler, M., & Lentz, K. (2015). Father involvement in the early years: an international comparison of policy and practice. Policy Press.

- Amato PR, Afifi TD. Feeling caught between parents: adult children’s relations with parents and subjective well-being. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2006;68(1):222–235. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2006.00243.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bregman, O. C., & White, C. M. (Eds.). (2010). Bringing Systems Thinking to Life: Expanding the Horizons for Bowen Family Systems Theory (1st ed.). Routledge. 10.4324/9780203842348

- Cabrera NJ, Scott M, Fagan J, et al. Coparenting and children’s school readiness: a mediational model. Family Process. 2012;51(3):307–324. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2012.01408.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera, N. J., & Tamis-LeMonda, C. S. (2013). Handbook of father involvement: multidisciplinary perspectives, (2nd ed.) Routledge.

- Cooper, M. (2019). Family values: Between neoliberalism and the new social conservatism. Zone Books.

- Doucet, A. (2013). Gender roles and fathering. In Handbook of father involvement: Multidisciplinary perspectives, (2nd ed., pp. 297–319). Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

- Fabrigar, L. R., & Wegener, D. T. (2012). Exploratory factor analysis. Oxford University Press USA.

- Fass, P. S. (2017). The end of American childhood: a history of parenting from life on the frontier to the managed child. Princeton University Press.

- Feinberg ME. The internal structure and ecological context of coparenting: a framework for research and intervention. Parenting. 2003;3(2):95–131. doi: 10.1207/S15327922PAR0302_01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg ME, Brown LD, Kan ML. A multi-domain self-report measure of coparenting. Parenting. 2012;12(1):1–21. doi: 10.1080/15295192.2012.638870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg ME, Kan ML. Establishing family foundations: intervention effects on coparenting, parent/infant well-being, and parent–child relations. Journal of Family Psychology: JFP: Journal of the Division of Family Psychology of the American Psychological Association (Division 43) 2008;22(2):253–263. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.22.2.253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hock RM, Mooradian JK. Co-parenting quality among adoptive mothers: Contributions of socioeconomic status, child demands and adult relationship characteristics. Child & Family Social Work. 2012;17(1):85–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2206.2011.00775.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hock RM, Mooradian JK. Defining coparenting for social work practice: A critical interpretive synthesis. Journal of Family Social Work. 2013;16(4):314–331. doi: 10.1080/10522158.2013.795920. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Irace K. Coparenting in diverse family systems. In: McHale JP, editor. Coparenting: A conceptual and clinical examination of family systems. American Psychological Association; 2011. pp. 15–37. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson BD, Berdahl LD, Horne M, Richter EA, Walters M. A Parenting Competency Model. Parenting. 2014;14(2):92–120. doi: 10.1080/15295192.2014.914361. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser HF. The application of electronic computers to factor analysis. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 1960;20(1):141–151. doi: 10.1177/001316446002000116. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kerig, P. K. (2019). Parenting and family systems. In M. H. Bornstein (Ed.), Handbook of parenting: Being and becoming a parent (pp. 3–35). Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

- Kline, R. B. (2010). principles and practice of structural equation modeling, 3rd ed. Guilford Publications.

- Luxton, M. (2011). Changing families, new understandings. Vanier Institute of the Family. Retreived online at https://vanierinstitute.ca/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/CFT_2011-06-00_EN.pdf

- Margolin G, Gordis EB, John RS. Coparenting: a link between marital conflict and parenting in two-parent families. Journal of Family Psychology. 2001;15(1):3–21. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.15.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHale, J. (2007). Charting the bumpy road of coparenthood: understanding the challenges of family life. USF St. Petersburg Campus Faculty Publications.

- McHale J, Fivaz-Depeursinge E, Dickstein S, et al. New evidence for the social embeddedness of infants’ early triangular capacities. Family Process. 2008;47(4):445–463. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2008.00265.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHale JP. Overt and covert coparenting processes in the family. Family Process. 1997;36(2):183–201. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.1997.00183.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHale, J. P., & Lindahl, K. M. (2011). Coparenting: A conceptual and clinical examination of family systems (pp. xii, 314). American Psychological Association.

- McHale, J. P., & Sirotkin, Y. S. (2019). Coparenting in diverse family systems. In Handbook of parenting: Being and becoming a parent, Vol. 3, (3rd ed., pp. 137–166). Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

- Miller, T. (2010). making sense of fatherhood: gender, caring and work. Cambridge University Press.

- Minuchin, S. (1974). Families & family therapy. Boston Mass. Harvard U. Press.

- Mollà Cusí L, Günther-Bel C, Vilaregut Puigdesens A, et al. Instruments for the assessment of coparenting: a systematic review. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2020;29(9):2487–2506. doi: 10.1007/s10826-020-01769-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pattnaik, J. (2012). Father involvement in young children’s lives: a global analysis. Springer Science & Business Media.

- Pruett, K. D. & Pruett, M. K. (2009). Partnership parenting: How men and women parent differently—why it helps your kids and can strengthen your marriage. Da Capo Press.

- Pruett MK, Nakash O, Welton E, et al. Using an initial clinical interview to assess the coparenting relationship: preliminary examples from the supporting father involvement program. Smith College Studies in Social Work. 2019;89(1):38–65. doi: 10.1080/00377317.2019.1576466. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pruett MK, Pruett KD, Cowan CP, Cowan PA. enhancing paternal engagement in a coparenting paradigm. Child Development Perspectives. 2017;11(4):245–250. doi: 10.1111/cdep.12239. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Putnick DL, Bornstein MH. Measurement invariance conventions and reporting: the state of the art and future directions for psychological research. Developmental Review. 2016;41:71–90. doi: 10.1016/j.dr.2016.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saini M, Pruett MK, Alschech J, et al. A pilot study to assess Coparenting Across Family Structures (CoPAFS) Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2019;28(5):1392–1401. doi: 10.1007/s10826-019-01370-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith GT, McCarthy DM, Anderson KG. On the Sins of Short-Form Development. Psychological Assessment. 2000;12(1):102–111. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.12.1.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teubert D, Pinquart M. The association between coparenting and child adjustment: a meta-analysis. Parenting. 2010;10(4):286–307. doi: 10.1080/15295192.2010.492040. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Teubert D, Pinquart M. The Coparenting Inventory for Parents and Adolescents (CI-PA) European Journal of Psychological Assessment. 2011;27(3):206–215. doi: 10.1027/1015-5759/a000068. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Van Egeren LA, Hawkins DP. Coming to Terms With Coparenting: Implications of Definition and Measurement. Journal of Adult Development. 2004;11(3):165–178. doi: 10.1023/B:JADE.0000035625.74672.0b. [DOI] [Google Scholar]